Abstract

Notch signaling is an evolutionarily conserved cell-cell signaling system that controls the fate of cells during development. In this review, we will summarize the literature that Notch signaling during development controls nephron number and segmentation and therefore could influence kidney disease susceptibility. We will also review the evidence that Notch is reactivated in adult-onset diabetic kidney disease where it promotes the development of nephropathy including glomerulopathy, tubulointerstitial fibrosis and possibly arteriopathy and inflammation. Finally, we will review the evidence that blockade of pathogenic Notch signaling alters the natural history of diabetic nephropathy and thus could represent a novel therapeutic approach to the management of diabetic kidney disease.

Diabetic Kidney Disease

Diabetes mellitus is complicated by nephropathy in approximately 35 percent of patients making diabetic kidney disease (DKD) the leading cause of end stage renal disease in the United States and the developed world [1]. Poor glucose control and uncontrolled hypertension are important risk factors for the development of nephropathy; however, there also appears to be a genetic component to the disease as a family history of kidney disease is a strong predictor of renal functional decline [2, 3]. Current therapy is aimed at improving glucose control and lowering intra-glomerular pressure by controlling systemic blood pressure preferably with renin-angiotensin system inhibitors. However, despite intensified glucose control and the wide-spread use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, the prevalence of diabetic nephropathy continues to increase [1] and new therapeutic strategies are urgently needed.

Diabetes affects many different cell types in the kidney. Traditionally DKD is considered to be part of the microvascular complications of diabetes mellitus, indicating the key role of the dysfunctional endothelial cells. Renal histology in DKD is characterized by thickening of the basement membrane, mesangial expansion and podocyte loss, indicating that all layers of the glomerular filtration barrier is involved [4]. Advanced DKD is also characterized by tubulo-interstitial fibrosis, accumulation of activated myofibroblasts, collagen and inflammatory cells and loss and dedifferentiation of tubular epithelial cells [4]. In this review, we will focus on the role of the Notch signaling pathway as a regulator of glomerular, tubular, vascular and immune function during development and the pathogenesis of DKD.

Notch Signaling; the basics

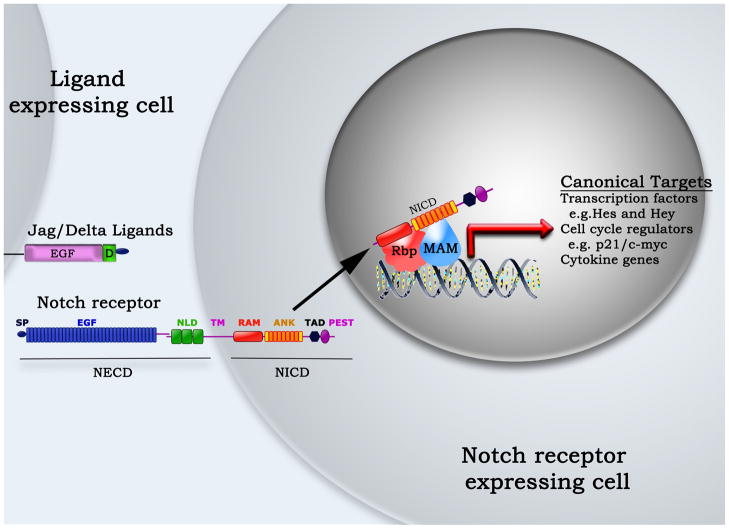

Mammalian Notch receptors (Notch1–4) are a family of ancient transmembrane proteins that are present in all metazoa and are key regulators of cellular development, differentiation, survival and function. Notch signaling is short distanced as it requires cell-cell contact when the extracellular domain of the Notch receptor engages a Notch ligand on an adjacent cell (Figure 1). The active receptor then travels to the nucleus without a signal amplification step. The effects of receptor engagement are cell-type and context dependent. This is usually achieved by interacting with other signaling pathways including, but not limited to hypoxia inducible factor (HIF1)[5, 6], transforming growth factor (TGF-β)/Smad [7], Wnt/β-catenin[8, 9], NFκB[10] or vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [11, 12].

Figure 1. Schematic representation of Notch signaling.

Notch signaling is initiated during cell-cell contact when a Notch receptor comes into contact which a Jagged (Jag) or Delta-like (Delta) ligand. Ligand engagement releases the Notch intracellular domain (NICD), which translocates to the nucleus to initiate canonical or non-canonical signaling.

ANK – ankyrin repeats, EGF – Epidermal growth factor repeats, MAM – Mastermind-like, Hes – Hairy-enhancer of split, Hey - Hairy/enhancer of split related with YRPW motif, NLD – Notch/Lin domain, PEST – Proline (P), glutamic acid (E), serine(S) and threonine(T) sequence, RAM – Rbp-jκ associating motif, Rbpj – Recombination signal binding protein for immunoglobulin kappa J, SP – signal peptide, TAD – Transactivating domain, TM – transmembrane region,

Notch receptors have a conserved domain structure (Figure 1) [13]. The N-terminal Notch extracellular domain (NECD) consisting of multiple epidermal growth factor (EGF) repeats and a highly coiled negative regulatory region containing the Notch/Lin domain (NLD) that is the hallmark of this receptor family. The single transmembrane region connects the NECD to the C-terminal Notch intracellular domain (NICD) that contains one or two nuclear localization signals and several protein-protein interaction domains. Notch ligands in mammals belong to two different families, namely Jagged-like (Jag1–2) and Delta-like (Dll1–4), based on homology to the ligands seen in the Drosophila. Ligand engagement triggers a series of proteolytic events that culminates in the release of the NICD from the membrane by the presenilin/γ-secretase complex [14]. Thereafter, the NICD moves into the nucleus where it becomes part of a transcription activating complex that also contains the recombination signal binding protein for immunoglobulin kappa J region (RBP-jκ or CBF-1) and mastermind-like (MAM) proteins [15, 16]. In a process called canonical Notch signaling (Figure 1), the complex of NICD, RBP-jκ, and MAM induces the expression of Notch target genes that all contain an RBP-jκ binding motif [15].

Notch signaling has long been studied as a critical regulator of cell fate during development [13]; however, convincing evidence is now emerging that Notch signaling is also a central regulator of cellular function in adults and that Notch may be activated in pathologic conditions.

Notch signaling during kidney development determines nephron segmentation and endowment

The functional unit of the kidney is the nephron. There are significant variations between people in regard to their nephron number and nephron endowment refers to the number of functional nephrons that an individual has at birth. In human beings nephrogenesis is complete by about 34-weeks of gestation at which time there are between 200,000 and 2 million nephrons [17]. Low nephron endowment caused by genetic on environmental factors is considered to be an important risk factor for the development of adult-onset kidney disease and hypertension [18, 19]. Notch signaling appears to be a critical determinant of nephron endowment [20–23]. Rare spontaneous mutations in JAG1 or NOTCH2, termed Alagille’s syndrome, are associated with renal hypoplasia indicating the key role of Notch in human kidney development [24–26].

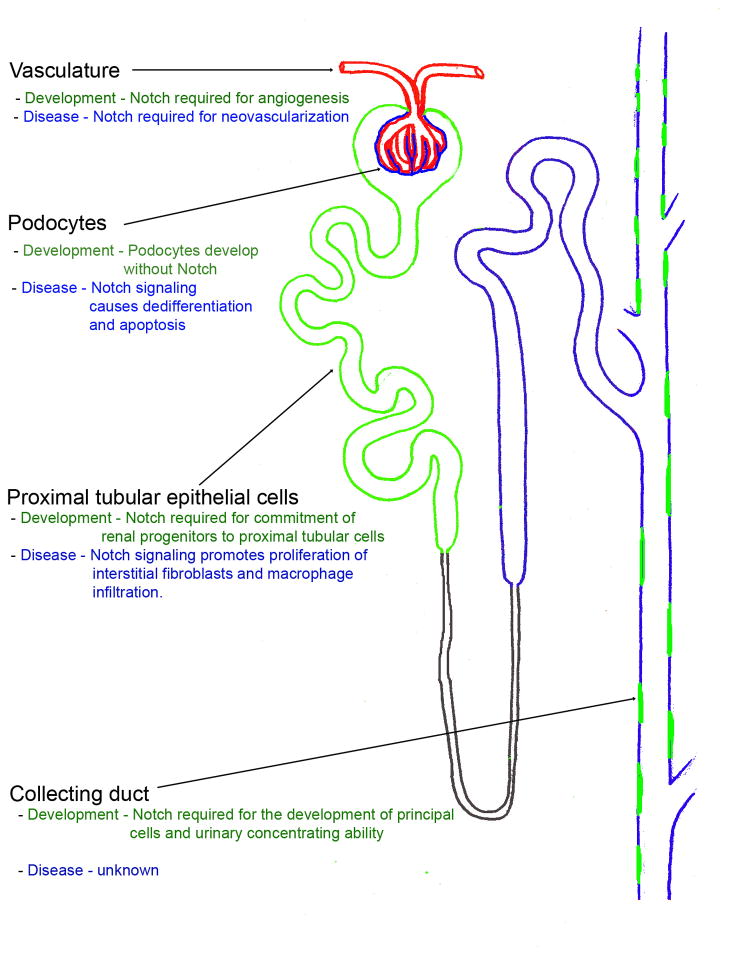

The detailed mechanistic effects of Notch signaling during mammalian kidney development have recently been defined using different genetically modified mouse models (Figure 2)[20–23]. The kidney develops from two different mesenchymal structures: the metanephric mesenchyme and the ureteric bud. Renal epithelial cell progenitors in the metanephric mesenchyme proliferate, undergo a mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition, and differentiate into cells of the different nephron segments including glomerular podocytes and parietal epithelial cells and the tubular cells of the proximal tubule, loop-of-Henle, and distal tubule. The ureteric bud gives rise to the collecting duct system. Even in the earliest epithelial cells that are seen in the renal vesicles, Notch and receptors and ligands are not randomly expressed [27–29]. Rather, cells committed to become distal tubular cells predominantly express Jag1 while the precursors of proximal tubular epithelial express Notch2 and Notch1[22]. The robust expression of Notch targets genes in the early proximal tubule epithelium indicates that canonical Notch signaling is highly active during nephrogenesis in these cells [20, 27–29].

Figure 2. Role of Notch signaling during kidney development and disease.

A diagram of the nephron showing the renal vasculature (red), the proximal tubules and collecting duct principal cells that require Notch signaling for normal development (green), and the podocytes, distal tubular cells and collecting duct intercalated cells (blue) that can develop independently of Notch signaling. The proposed role of Notch in each cell type during development and disease is listed.

Genetic deletion of the γ-secretase enzyme components (Presenilin 1, 2)[23] or pharmacological inhibition of the γ-secretase complex in the developing metanephric mesenchyme [22] induced nephron formation without proximal (podocyte and proximal tubule) epithelium. Proximal epithelial cell differentiation is instructed by the specific, non-redundant engagement of Notch2 by Jag1. Deletion of Notch2 or Jag1 had profound effects on kidney development and nephron segmentation [21, 30], while Notch1 deletion had no effect on kidney development [21]. Fate mapping studies indicate that the main effect of Notch is to induce and stabilize the proximal tubular epithelial cell fate [20]. In contrast to knockout studies in which proximal tubular epithelia are missing, expression of constitutively active NICD in epithelial progenitors caused premature induction of the proximal tubule fate and the depletion of progenitor cells [21]. Thus increased or decreased Notch signaling during kidney development alters epithelial progenitor cell fate and has profound effects on nephron endowment, which may subsequently influence kidney disease risk.

Interestingly, recent genetic studies have linked, polymorphisms of the Notch2 gene to the development of diabetes [31, 32] and although the mechanisms for this association are not well defined, the experimental evidence discussed above suggests that either gain- or loss-of-function mutations in Notch may profoundly effect pancreatic β cell [33] and nephron endowment.

Notch signaling promotes diabetic glomerulopathy

DKD is a primarily a glomerular disease, characterized by glomerular basement membrane thickening and mesangial expansion that is evident early in the course of kidney disease in patients with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes [4]. Podocytes, the epithelial cells that cover the capillary tuft of the glomerulus, are the major barrier that prevents the passage of serum proteins into the urinary filtrate [34] and podocyte simplification, dedifferentiation, and loss are now a recognized features of diabetic nephropathy that are predictive of the development of albuminuria and progression to end stage renal failure [35–38]. While Notch signaling is critical to nephron development, Notch is not required for podocyte development [20] and Notch receptors, ligands and target genes are not present in mature podocytes [27–29].

Notch signaling may be induced in mature podocytes under certain pathologic conditions for example following exposure to high glucose [39], TGF-β [40–42], VEGF, or ischemia [43–45]. These conditions are associated with increased expression of Jag1 as well as re-expression of low levels of Notch receptors (Notch1 or Notch2). It is presently not fully clear whether the ligand and the receptor are expressed on adjacent podocytes or the ligand is presented by another cell type (for example endothelial cells). The resulting Rbp-jκ dependent transcriptional activation of Notch target genes in podocytes profoundly influences cell function and survival [40, 46]. In mouse models, it seems clear that Notch signaling in the adult, injured glomerulus is pathogenic [39, 40]. Expression of constitutively active NICD in mature podocytes caused podocyte dedifferentiation, glomerulosclerosis, and apoptosis that led to albuminuria and progressive renal failure [40, 46]. In contrast, in rodents with diabetic or non-diabetic kidney disease blockade of Notch signaling using γ-secretase inhibitors decreased Notch target gene expression in the glomerulus, maintained the expression of nephrin and other podocyte differentiation markers, inhibited the pathologic expression of VEGF, and prevented diabetes-induced glomerulosclerosis and podocyte loss by apoptosis [39, 40]. Thus inhibiting the overactive Notch signaling in glomerular epithelial cells in the context of diabetic nephropathy appears to be a promising therapeutic approach.

Notch signaling promotes tubulointerstitial fibrosis

While diabetic glomerulopathy is present even at early stages of diabetic nephropathy, tubulointerstitial fibrosis is a typical feature of advanced disease and often heralds the onset of progression towards end stage renal disease [4, 47]. Notch signaling is required for tubular epithelial cell development but its activity is much reduced in the adult tubular epithelium [20, 27–29]. Reactivation of pathogenic Notch signaling in the tubular epithelial cells may occur in the diabetic or injury milieu in part due to TGF-β induced expression of Jag1 [48].

While Notch signaling may not be required for the repair of injured tubular cells, reactivation of canonical Notch signals in epithelial cells of the proximal tubule appears to promote the development of tubulointerstitial fibrosis [48]. The mechanism(s) of Notch induced fibrosis are incompletely defined and may well be indirect. Notch signaling mediates TGF-β induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in both human and rat tubular epithelial cells in culture; however, in vivo the situation appears to be more complex as overexpression of the constitutively active NICD does not induce epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition but does increased the expression of a classical Notch target gene HeyL. Notch signaling in tubular epithelial cells is associated with worsening of peritubular inflammatory cell infiltrates and increased proliferation of interstitial fibroblasts both of which correlate with the increased renal expression of matrix proteins. The authors concluded that sustained Notch activation induces a failed or incomplete differentiation of epithelial cells promoting proliferation and growth factor production that resulted in a vicious cycle that perpetuated inflammation and proliferation eventually leading to interstitial fibrosis. Regardless of the underlying etiology, tubular epithelial Notch signaling appears to be pathogenic and to promote the development of interstitial fibrosis that contributes to nephron loss and destruction of the normal tubulointerstitial architecture of the kidney. Notch blockade ameliorated interstitial fibrosis in two different models of non-diabetic tubulointerstitial disease without affecting tubular function [48].

Notch signaling in the diabetic blood vessels

Nephropathy is part of the microvascular complication group of diabetes [4]. In the kidney, large vessels as well as medium sized afferent and efferent arterioles of the glomerulus and interstitial arterioles may undergo hyalinosis. Notch signaling is well recognized to regulate the development of the vascular system in the embryo [49] and also plays an important role in orchestrating angiogenesis in malignant tumors and following tissue ischemia [50]. Effective new vessel formation requires a delicate balance between sprouting of new vessels and the maintenance of the developing vascular tube. Sprouting cells at the tip of the developing vessel express Dll4, which activates Notch1 and Notch4 receptors in the adjacent endothelial cells in the stem of the new vessel. Notch signaling in the stem negatively regulates VEGF-induced sprouting by inhibiting endothelial cell proliferation and migration in part due to reduced expression of the VEGF receptor 2 (VEGFR2), its co-receptor Neuropilin-I, and the chemokines receptor CXCR4 [49, 50]. This is critical to maintaining the balance of sprouting and tube development as blocking Notch signaling causes unregulated endothelial cell proliferation and promotes VEGF-dependent sprouting, neovascularization, and the formation of non-functional capillary networks.

Although no studies have directly assessed the role of Notch signaling on renal arteriolar function or neovascularization in diabetes or chronic kidney disease, Notch signaling does inhibit extra-renal angiogenesis in diabetes in part by altering the sensitivity of angioblasts to the VEGF [51]. Notch inhibition using the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT (N-[(3,5-Difluorophenyl)acetyl]-L-alanyl-2-phenyl]glycine-1,1-dimethyl-ethyl ester) has been demonstrated to improve neovascularization in diabetes and to enhance the development for functional vascular beds that improve perfusion to ischemic limbs. While these studies are encouraging, it is unclear to the authors whether neovascularization of the kidney would be desirable or pathogenic in diabetic nephropathy and so more definitive studies of the effects of Notch signaling in the endothelia or pericytes of the diabetic kidney are eagerly awaited.

Immune modulation by Notch another potential mechanism to influence diabetic nephropathy

Chronic low-grade inflammation and activation of the innate immune system are closely involved in the pathogenesis of diabetes and its microvascular complications. Inflammatory cytokines, mainly IL-1, IL-6, and IL-18, as well as Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), are implicated in the development and progression of diabetic nephropathy (reviewed by [52]). Notch is a key regulator of the immune system development [53]. Intra-thymic Notch1 signaling is essential for several distinct aspects of early T cell development and Notch signaling has also been implicated as a key regulator of peripheral T cell activation and effector cell differentiation, but its functions in these processes remain poorly understood [54]. Notch signaling is dispensable for B cell development in the bone marrow, but it is required to generate the innate-like marginal zone B cell subset in the spleen and may also regulate plasma cell functions [55]. In mice prone to develop systemic autoimmune disease, Notch inhibitors have been successfully applied to ameliorate lupus nephritis and other autoimmune end organ damage [56]. Long-term administration of γ-secretase inhibitors will likely interfere with both autoimmune and pathogen-induced immune response pathways, however, it remain to be shown how and whether immune modulation by Notch has much or any effect on DKD.

Summary and future of Notch modulation in diabetes

Based on animal model studies, Notch inhibitors clearly have the potential to ameliorate diabetic nephropathy, however, several important challenges remain. Firstly, γ-secretase inhibitors are non-specific and inhibit all presenilin mediated intra-membranous proteolysis. Although genetic studies have confirmed that the major effects of γ-secretase inhibitors on kidney development and disease is due to the disruption of Notch signaling, more targeted therapeutics would be advantageous and may decrease off-target effects especially during chronic exposure. Secondary, even specific Notch inhibitors could have the potential to produce dose limiting side-effects during long term use. In adult mammals, Notch signaling is critical for the differentiation and normal function of immune cells, enterocytes, and possibly neurons and blockade of Notch signaling may produce immunosuppression and chronic diarrhea. While careful dosing of γ-secretase inhibitors has overcome this problem in rodents, more targeted therapies that would allow for inhibition of specific Notch receptor ligand parings would go a long way to limiting the effects of extra-renal Notch inhibition. Finally effects of chronic Notch blockade on acid-base homeostasis and water remain to be determined (Figure 2) [57].

In summary (Figure 2), several studies in humans and mice have demonstrated that Notch signaling is essential for nephrogenesis and that defects in Notch pathway genes lead to a failure of normal nephron patterning and a reduced nephron number. Nephron number is a key determinant of renal disease susceptibility. Notch signaling is usually inactive in the adult kidney but there is now convincing evidence that signaling may be reactivated during the course of diabetic and non-diabetic nephropathy both in epithelial cells of the glomerulus or tubule and in the also endothelial or interstitial compartments of the kidney. Blockade of Notch signaling using γ-secretase inhibitors has proved effective in ameliorating diabetic glomerulopathy by preventing podocyte dedifferentiation and loss and tubulointerstitial fibrosis. Future studies will be needed to determine whether Notch inhibition is a clinically translatable strategy in the context of DKD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health (DK076077 to KS and DK30932 to David Salant), and by a grants from the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation to KS and the Evans Medical Foundation to RB.

Footnotes

There is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.de Boer IH, Rue TC, Hall YN, Heagerty PJ, Weiss NS, Himmelfarb J. Temporal trends in the prevalence of diabetic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA. 2011;305:2532–2539. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33) UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Lancet. 1998;352:837–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Boer IH, Rue TC, Cleary PA, Lachin JM, Molitch ME, Steffes MW, Sun W, Zinman B, Brunzell JD, White NH, Danis RP, Davis MD, Hainsworth D, Hubbard LD, Nathan DM. Long-term renal outcomes of patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus and microalbuminuria: an analysis of the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications cohort. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:412–420. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fioretto P, Caramori ML, Mauer M. The kidney in diabetes: dynamic pathways of injury and repair. The Camillo Golgi Lecture 2007. Diabetologia. 2008;51:1347–1355. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gustafsson MV, Zheng X, Pereira T, Gradin K, Jin S, Lundkvist J, Ruas JL, Poellinger L, Lendahl U, Bondesson M. Hypoxia requires notch signaling to maintain the undifferentiated cell state. Dev Cell. 2005;9:617–628. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zheng X, Linke S, Dias JM, Gradin K, Wallis TP, Hamilton BR, Gustafsson M, Ruas JL, Wilkins S, Bilton RL, Brismar K, Whitelaw ML, Pereira T, Gorman JJ, Ericson J, Peet DJ, Lendahl U, Poellinger L. Interaction with factor inhibiting HIF-1 defines an additional mode of cross-coupling between the Notch and hypoxia signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3368–3373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711591105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niranjan T, Murea M, Susztak K. The pathogenic role of notch activation in podocytes. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2009;111:e73–79. doi: 10.1159/000209207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fre S, Pallavi SK, Huyghe M, Lae M, Janssen KP, Robine S, Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Louvard D. Notch and Wnt signals cooperatively control cell proliferation and tumorigenesis in the intestine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900427106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blokzijl A, Dahlqvist C, Reissmann E, Falk A, Moliner A, Lendahl U, Ibanez CF. Cross-talk between the Notch and TGF-beta signaling pathways mediated by interaction of the Notch intracellular domain with Smad3. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:723–728. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200305112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song LL, Peng Y, Yun J, Rizzo P, Chaturvedi V, Weijzen S, Kast WM, Stone PJ, Santos L, Loredo A, Lendahl U, Sonenshein G, Osborne B, Qin JZ, Pannuti A, Nickoloff BJ, Miele L. Notch-1 associates with IKKalpha and regulates IKK activity in cervical cancer cells. Oncogene. 2008;27:5833–5844. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siekmann AF, Covassin L, Lawson ND. Modulation of VEGF signalling output by the Notch pathway. Bioessays. 2008;30:303–313. doi: 10.1002/bies.20736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thurston G, Kitajewski J. VEGF and Delta-Notch: interacting signalling pathways in tumour angiogenesis. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:1204–1209. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Rand MD, Lake RJ. Notch signaling: cell fate control and signal integration in development. Science. 1999;284:770–776. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Tetering G, Vooijs M. Proteolytic Cleavage of Notch: “HIT and RUN”. Curr Mol Med. 2011;11:255–269. doi: 10.2174/156652411795677972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borggrefe T, Oswald F. The Notch signaling pathway: Transcriptional regulation at Notch target genes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-8668-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kovall RA. Structures of CSL, Notch and Mastermind proteins: piecing together an active transcription complex. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2007;17:117–127. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah MM, Sampogna RV, Sakurai H, Bush KT, Nigam SK. Branching morphogenesis and kidney disease. Development. 2004;131:1449–1462. doi: 10.1242/dev.01089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brenner BM, Garcia DL, Anderson S. Glomeruli and blood pressure. Less of one, more the other? Am J Hypertens. 1988;1:335–347. doi: 10.1093/ajh/1.4.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Puelles VG, Hoy WE, Hughson MD, Diouf B, Douglas-Denton RN, Bertram JF. Glomerular number and size variability and risk for kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2011;20:7–15. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3283410a7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonegio RG, Beck LH, Kahlon RK, Lu W, Salant DJ. The fate of Notch-deficient nephrogenic progenitor cells during metanephric kidney development. Kidney Int. 2011;79:1099–1112. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng HT, Kim M, Valerius MT, Surendran K, Schuster-Gossler K, Gossler A, McMahon AP, Kopan R. Notch2, but not Notch1, is required for proximal fate acquisition in the mammalian nephron. Development. 2007;134:801–811. doi: 10.1242/dev.02773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng HT, Miner JH, Lin M, Tansey MG, Roth K, Kopan R. Gamma-secretase activity is dispensable for mesenchyme-to-epithelium transition but required for podocyte and proximal tubule formation in developing mouse kidney. Development. 2003;130:5031–5042. doi: 10.1242/dev.00697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang P, Pereira FA, Beasley D, Zheng H. Presenilins are required for the formation of comma- and S-shaped bodies during nephrogenesis. Development. 2003;130:5019–5029. doi: 10.1242/dev.00682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li L, Krantz ID, Deng Y, Genin A, Banta AB, Collins CC, Qi M, Trask BJ, Kuo WL, Cochran J, Costa T, Pierpont ME, Rand EB, Piccoli DA, Hood L, Spinner NB. Alagille syndrome is caused by mutations in human Jagged1, which encodes a ligand for Notch1. Nat Genet. 1997;16:243–251. doi: 10.1038/ng0797-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDaniell R, Warthen DM, Sanchez-Lara PA, Pai A, Krantz ID, Piccoli DA, Spinner NB. NOTCH2 mutations cause Alagille syndrome, a heterogeneous disorder of the notch signaling pathway. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:169–173. doi: 10.1086/505332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oda T, Elkahloun AG, Pike BL, Okajima K, Krantz ID, Genin A, Piccoli DA, Meltzer PS, Spinner NB, Collins FS, Chandrasekharappa SC. Mutations in the human Jagged1 gene are responsible for Alagille syndrome. Nat Genet. 1997;16:235–242. doi: 10.1038/ng0797-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen L, Al-Awqati Q. Segmental expression of Notch and Hairy genes in nephrogenesis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;288:F939–952. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00369.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leimeister C, Schumacher N, Gessler M. Expression of Notch pathway genes in the embryonic mouse metanephros suggests a role in proximal tubule development. Gene Expr Patterns. 2003;3:595–598. doi: 10.1016/s1567-133x(03)00114-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piscione TD, Wu MY, Quaggin SE. Expression of Hairy/Enhancer of Split genes, Hes1 and Hes5, during murine nephron morphogenesis. Gene Expr Patterns. 2004;4:707–711. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCright B, Lozier J, Gridley T. A mouse model of Alagille syndrome: Notch2 as a genetic modifier of Jag1 haploinsufficiency. Development. 2002;129:1075–1082. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.4.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCarthy MI, Zeggini E. Genome-wide association studies in type 2 diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2009;9:164–171. doi: 10.1007/s11892-009-0027-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zeggini E, Scott LJ, Saxena R, Voight BF, Marchini JL, Hu T, de Bakker PI, Abecasis GR, Almgren P, Andersen G, Ardlie K, Bostrom KB, Bergman RN, Bonnycastle LL, Borch-Johnsen K, Burtt NP, Chen H, Chines PS, Daly MJ, Deodhar P, Ding CJ, Doney AS, Duren WL, Elliott KS, Erdos MR, Frayling TM, Freathy RM, Gianniny L, Grallert H, Grarup N, Groves CJ, Guiducci C, Hansen T, Herder C, Hitman GA, Hughes TE, Isomaa B, Jackson AU, Jorgensen T, Kong A, Kubalanza K, Kuruvilla FG, Kuusisto J, Langenberg C, Lango H, Lauritzen T, Li Y, Lindgren CM, Lyssenko V, Marvelle AF, Meisinger C, Midthjell K, Mohlke KL, Morken MA, Morris AD, Narisu N, Nilsson P, Owen KR, Palmer CN, Payne F, Perry JR, Pettersen E, Platou C, Prokopenko I, Qi L, Qin L, Rayner NW, Rees M, Roix JJ, Sandbaek A, Shields B, Sjogren M, Steinthorsdottir V, Stringham HM, Swift AJ, Thorleifsson G, Thorsteinsdottir U, Timpson NJ, Tuomi T, Tuomilehto J, Walker M, Watanabe RM, Weedon MN, Willer CJ, Illig T, Hveem K, Hu FB, Laakso M, Stefansson K, Pedersen O, Wareham NJ, Barroso I, Hattersley AT, Collins FS, Groop L, McCarthy MI, Boehnke M, Altshuler D. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association data and large-scale replication identifies additional susceptibility loci for type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2008;40:638–645. doi: 10.1038/ng.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim W, Shin YK, Kim BJ, Egan JM. Notch signaling in pancreatic endocrine cell and diabetes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;392:247–251. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.12.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miner JH. A molecular look at the glomerular barrier. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2003;94:e119–122. doi: 10.1159/000072495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li JJ, Kwak SJ, Jung DS, Kim JJ, Yoo TH, Ryu DR, Han SH, Choi HY, Lee JE, Moon SJ, Kim DK, Han DS, Kang SW. Podocyte biology in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int Suppl. 2007:S36–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakamura T, Ushiyama C, Suzuki S, Hara M, Shimada N, Ebihara I, Koide H. Urinary excretion of podocytes in patients with diabetic nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000;15:1379–1383. doi: 10.1093/ndt/15.9.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pagtalunan ME, Miller PL, Jumping-Eagle S, Nelson RG, Myers BD, Rennke HG, Coplon NS, Sun L, Meyer TW. Podocyte loss and progressive glomerular injury in type II diabetes. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:342–348. doi: 10.1172/JCI119163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wiggins RC. The spectrum of podocytopathies: a unifying view of glomerular diseases. Kidney Int. 2007;71:1205–1214. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin CL, Wang FS, Hsu YC, Chen CN, Tseng MJ, Saleem MA, Chang PJ, Wang JY. Modulation of notch-1 signaling alleviates vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes. 2010;59:1915–1925. doi: 10.2337/db09-0663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Niranjan T, Bielesz B, Gruenwald A, Ponda MP, Kopp JB, Thomas DB, Susztak K. The Notch pathway in podocytes plays a role in the development of glomerular disease. Nat Med. 2008;14:290–298. doi: 10.1038/nm1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walsh DW, Roxburgh SA, McGettigan P, Berthier CC, Higgins DG, Kretzler M, Cohen CD, Mezzano S, Brazil DP, Martin F. Co-regulation of Gremlin and Notch signalling in diabetic nephropathy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1782:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morrissey J, Guo G, Moridaira K, Fitzgerald M, McCracken R, Tolley T, Klahr S. Transforming growth factor-beta induces renal epithelial jagged-1 expression in fibrotic disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1499–1508. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000017905.77985.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang R, Zhou Q, Veeraragoo P, Yu H, Xiao Z. Notch2/Hes-1 pathway plays an important role in renal ischemia and reperfusion injury-associated inflammation and apoptosis and the gamma-secretase inhibitor DAPT has a nephroprotective effect. Ren Fail. 2011;33:207–216. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2011.553979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gupta S, Li S, Abedin MJ, Wang L, Schneider E, Najafian B, Rosenberg M. Effect of Notch activation on the regenerative response to acute renal failure. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;298:F209–215. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00451.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kobayashi T, Terada Y, Kuwana H, Tanaka H, Okado T, Kuwahara M, Tohda S, Sakano S, Sasaki S. Expression and function of the Delta-1/Notch-2/Hes-1 pathway during experimental acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2008;73:1240–1250. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Waters AM, Wu MY, Onay T, Scutaru J, Liu J, Lobe CG, Quaggin SE, Piscione TD. Ectopic notch activation in developing podocytes causes glomerulosclerosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:1139–1157. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007050596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bohle A, Wehrmann M, Bogenschutz O, Batz C, Muller CA, Muller GA. The pathogenesis of chronic renal failure in diabetic nephropathy. Investigation of 488 cases of diabetic glomerulosclerosis. Pathol Res Pract. 1991;187:251–259. doi: 10.1016/s0344-0338(11)80780-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bielesz B, Sirin Y, Si H, Niranjan T, Gruenwald A, Ahn S, Kato H, Pullman J, Gessler M, Haase VH, Susztak K. Epithelial Notch signaling regulates interstitial fibrosis development in the kidneys of mice and humans. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:4040–4054. doi: 10.1172/JCI43025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krebs LT, Xue Y, Norton CR, Shutter JR, Maguire M, Sundberg JP, Gallahan D, Closson V, Kitajewski J, Callahan R, Smith GH, Stark KL, Gridley T. Notch signaling is essential for vascular morphogenesis in mice. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1343–1352. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Segarra M, Williams CK, de Sierra ML, Bernardo M, McCormick PJ, Maric D, Regino C, Choyke P, Tosato G. Dll4 activation of Notch signaling reduces tumor vascularity and inhibits tumor growth. Blood. 2008;112:1904–1911. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-126045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cao L, Arany PR, Kim J, Rivera-Feliciano J, Wang YS, He Z, Rask-Madsen C, King GL, Mooney DJ. Modulating Notch signaling to enhance neovascularization and reperfusion in diabetic mice. Biomaterials. 2010;31:9048–9056. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Navarro-Gonzalez JF, Mora-Fernandez C, de Fuentes MM, Garcia-Perez J. Inflammatory molecules and pathways in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2011;7:327–340. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2011.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McKenzie GJ, Khan M, Briend E, Stallwood Y, Champion BR. Notch: a unique therapeutic target for immunomodulation. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2005;9:395–410. doi: 10.1517/14728222.9.2.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Amsen D, Blander JM, Lee GR, Tanigaki K, Honjo T, Flavell RA. Instruction of distinct CD4 T helper cell fates by different notch ligands on antigen-presenting cells. Cell. 2004;117:515–526. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00451-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tanigaki K, Han H, Yamamoto N, Tashiro K, Ikegawa M, Kuroda K, Suzuki A, Nakano T, Honjo T. Notch-RBP-J signaling is involved in cell fate determination of marginal zone B cells. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:443–450. doi: 10.1038/ni793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Teachey DT, Seif AE, Brown VI, Bruno M, Bunte RM, Chang YJ, Choi JK, Fish JD, Hall J, Reid GS, Ryan T, Sheen C, Zweidler-McKay P, Grupp SA. Targeting Notch signaling in autoimmune and lymphoproliferative disease. Blood. 2008;111:705–714. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-087353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jeong HW, Jeon US, Koo BK, Kim WY, Im SK, Shin J, Cho Y, Kim J, Kong YY. Inactivation of Notch signaling in the renal collecting duct causes nephrogenic diabetes insipidus in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3290–3300. doi: 10.1172/JCI38416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]