Abstract

Using a high-risk community sample, multiple regression analyses were conducted separately for mothers (N=416) and fathers (N= 346) to test the unique, prospective influence of parental negative affect on adolescent maladjustment (internalizing symptoms, externalizing symptoms, and negative emotionality) two years later over and above parental alcohol and affective disorders, major disruption in the family environment, and parenting. Adolescent sex was tested as a moderator. Results indicated that maternal (but not paternal) negative affect had a unique, prospective effect on adolescent internalizing symptoms in girls and negative emotionality in both sexes, but did not predict adolescent externalizing symptoms. Findings demonstrate that mothers’ negative affect may have unique effects on adolescent adjustment, separate from the effects of clinically significant parental psychopathology, parenting, and disruption in the family environment.

Keywords: negative affect, intergenerational transmission, adolescent development, emotional processes, family risk factors

Both parental psychopathology and parental negative affect have been linked to a variety of emotional and behavioral problems in offspring (e.g., Connell & Goodman, 2002; Cummings, Keller, & Davies, 2005). It has been suggested that parental negative affect may have direct effects on child maladjustment, separate from the effects of parental symptoms of psychopathology (e.g., Lovejoy, Graczyk, O’Hare, & Neuman, 2000) and parenting behavior (Cummings et al., 2005). However, few studies have differentiated among the effects of these important constructs in predicting adolescent adjustment. The current study tested whether parental negative affect had a unique effect on future adolescent maladjustment, over and above parents’ diagnoses of alcoholism and/or affective disorders, major disruption in the family environment, and parenting. We also examined whether adolescent sex moderated this effect.

Parental Negative Affect

Many studies have shown that emotional experience tends to be dominated by two separate and broad dimensions—positive and negative affect (Watson & Clark, 1984). In the current study, we define negative affect as a broad measure of emotional distress that includes multiple aversive feelings and moods (Russell & Carroll, 1999; Watson & Clark, 1984), including sadness, anxiety, and anger. This definition emphasizes that these various negative emotions share a general component of emotional distress, that is, negative affect. Individuals vary in the degree to which they experience negative affect, and vary in the degree (frequency, intensity) to which they express/communicate their negative affect to others. Hence, self-report measures of negative affect, like the one in the present study, may also reflect how much negative affect is expressed in a manner that others can perceive.

Although negative affectivity is one of the defining features of an affective disorder, high levels of negative affect alone are insufficient for an affective disorder diagnosis. Affective disorders involve the experience of emotion that is abnormal in its frequency, intensity, duration, and/or context (Davidson, Jackson, & Kalin, 2000; Zeman, Klimes-Dougan, Cassano, & Adrian, 2007). Moreover, affective disorders are characterized by features other than simply excessive negative affect, such as diminished capacity to feel positive affect (Watson et al., 1995), in addition to symptoms like changes in appetite, insomnia, and poor concentration. Therefore, negative affect and affective disorders should be considered to be two separate but correlated constructs. Although parental negative affect that is high in frequency and/or intensity may have detrimental effects on adolescent functioning that extend beyond the influence of parental affective disorders, studies examining how parental affective disorders influence adolescents typically do not examine whether negative affect has unique effects.

There are several reasons why parental negative affect may be an important predictor of adolescent maladjustment. From a social learning perspective (Bandura, 1977), children learn to regulate emotions via observation and parent-child emotional interactions. Children may thus develop negative emotionality simply by imitating the negative emotions or affective expression of their parents (Morris, Silk, Steinberg, & Robinson, 2007). Similarly, an emotion contagion mechanism, in which negative emotions in children are induced via facial, vocal, and other gestures, may operate to predict increased offspring negative emotionality and internalizing symptomology. Furthermore, it appears that that negative affect in family members reciprocally influence one another, resulting in increasingly high levels of negative affect in both parents and adolescents (Cook, Kenny, & Goldstein, 1991).

Adolescent internalizing symptoms, externalizing symptoms, and negative emotionality have all been associated with parental negative affect (Cummings et al., 2005; Morris et al., 2007; Stocker, Richmond, Rhoades, and Kiang, 2007). Stocker and colleagues (2007) theorize that “adolescents who are exposed to high levels of parental negative affect may develop internalizing symptoms because they may feel rejected, scared, or even intimidated by their parents,” whereas they may develop externalizing symptoms simply by emulating the negative emotional expressiveness (e.g., irritability, anger) of their parents (Stocker et al., 2007, p. 312). Family process models suggest that children may perceive parental negative affect as a threat to family stability. This perceived threat may cause an increase in internalizing symptoms and/or may lead to maladaptive coping strategies that result in behavioral problems (Cummings et al., 2005). However, because most studies on emotions in families focus on either infancy or childhood, it is unknown whether parental negative affect directly affects adolescent maladjustment, over and above other risk variables. Examining the unique influence of parental negative affect on offspring outcomes during adolescence is important because this is a period during which internalizing/externalizing problems and negative emotionality are likely to increase in severity (Kessler, Avenenoli, & Merikangas, 2001).

In addition, it is not currently clear how the influences of parental negative affect during adolescence may differ for mothers versus fathers, and how these influences may be moderated by adolescent sex. According to Halberstadt and Eaton (2002), parental negative emotional expressiveness may be a mechanism of family emotion socialization because it influences children’s understanding of emotions and emotion regulation. Although mothers and fathers do not appear to differ in average levels of negative emotion (Stocker et al., 2007), they do differ in how they socialize adolescent offspring about emotion (Klimes-Dougan et al., 2007; Stocker et al., 2007). For instance, Klimes-Dougan and colleagues (2007) found that mothers tend to reward and magnify their adolescents’ displays of negative emotions, whereas fathers tend to overlook or ignore them. Given these differences, the current study examined the influence of parental negative affect separately for mothers and fathers, and also examined adolescent sex as a moderator. Because sex differences in the prevalence of depression first emerge during adolescence (Crick & Zahn-Waxler, 2003), it is important to examine whether the effect of parental negative affect on adolescent internalizing symptoms and negative emotionality is different for boys and girls. Indeed, past research has found girls to be more vulnerable to the effects of parental psychopathology and distress compared to boys (Davies & Windle, 1997; Su, Hoffmann, Gerstein, & Johnson, 1997), suggesting that adolescent girls may also be particularly vulnerable to the effects of parental negative affect.

Parental Negative Affect and Parental Alcohol/Affective Disorders

Although parental negative affect may itself be an important predictor of adolescent maladjustment, it is not currently clear whether parental negative affect uniquely affects adolescent adjustment, or if the effect of parental negative affect is simply due to its covariation with parental psychopathology. Negative affect is one component that is common to multiple forms of psychopathologies, including both alcohol and affective disorders, which may pose additional risks to child adjustment that extend beyond the influence of parental symptoms of these disorders. For instance, depressed mothers tend to display more worry, criticism, and irritability during interactions with their children compared to non-depressed mothers (Lovejoy et al., 2000), which may interfere with normal development of emotional expression and regulation in children (Izard et al., 2002). Parental alcoholism is also associated with high levels of negative affect expression, even though there are no alcohol abuse or dependence symptoms that directly relate to mood (e.g., Eiden, Edwards, & Leonard, 2004; Keller, Cummings, Davies, & Mitchell, 2008). In addition, research has shown that drinking problems in one parent appear to be associated with higher levels of negative affect expression in both parents (Eiden et al., 2004), and that the negative affect expressed by alcoholics may result in increased internalizing and externalizing symptoms in adolescent offspring (e.g., Brook, Brook, Gordon, & Whiteman, 1990). Finally, it should also be noted that both parental depression and alcoholism have also been linked to adolescent negative emotionality and emotion dysregulation, which place adolescents at risk for a wide range of maladaptive outcomes (Morris et al., 2007).

Parenting Behavior and Parental Negative Affect

A large research literature has documented that positive parenting has protective influences on adolescent adjustment (see Steinberg, 2001). Although many studies have already shown that positive parenting promotes better offspring outcomes, the current study included measures of parenting behaviors in order to be able to differentiate between parenting, parental psychopathology, and parental negative affect, given that all three of these constructs are related. The current study examined two key dimensions of parenting—parental support (e.g., warmth, acceptance), and consistency of discipline—as numerous studies have found these two dimensions to be especially influential and indicative of the quality of parenting behavior (e.g., Maccoby, 1992; Steinberg, 2001).

Although studies consistently link low levels of parental support and consistency of discipline to both internalizing and externalizing symptoms in children and adolescents (e.g., Hoeve et al., 2009; Berg-Nielsen, Vikan, & Dahl, 2002), meta-analytic studies have found that parenting accounts for a relatively small proportion of the variance in child and adolescent psychological problems—less than 6% of the variance in externalizing problems (Rothbaum & Weisz, 1994), 4% of the variance in anxiety (McLeod, Wood, & Weisz, 2007), and 8% of the variance in depression (McLeod, Weisz, & Wood, 2007). Therefore, it is likely that parents may transmit risk for offspring maladjustment through variables other than parenting, such as parental psychopathology or negative affect. Given that these variables are all correlated, it is unclear if and how each may uniquely influence offspring maladjustment. The primary purpose of the present study was to simultaneously examine all three of these risk variables—parental psychopathology (alcohol or affective disorders), parental behavior (provision of support or consistency of discipline), and parental negative affect—as predictors of adolescent adjustment.

Moreover, the protective influence of parenting on offspring outcomes may depend on the sex of both the parent and the adolescent. Few studies have examined how both parent and child sex may moderate the influence of parenting on adolescent outcomes, usually because studies tend to examine either maternal or paternal influences rather than both. Although some studies have found the effects of parenting on adolescent internalizing and externalizing symptoms to be the same across sex (Scarmella, Conger, & Simon, 1999), others have found that that poor parenting behavior is more strongly linked to maladjustment in same-sex parent-child pairs (e.g., Deater-Deckard & Dodge, 1997; Hoeve et al., 2009). That is, the poor parenting of fathers toward sons and the poor parenting of mothers toward daughters may have the strongest effects. Given that it is not currently clear how the effects of parenting on adolescent outcomes may differ across sex, the current study examined adolescent sex may as a moderator of both parenting (provision of support and consistency of discipline) and parental negative affect.

The Present Study

A large body of research has shown that children of alcoholic and/or depressed parents are more likely to be exposed to parental negative affect, deficient parenting behavior, and stressful home environments (e.g., Berg-Nielsen et al., 2002; Connell & Goodman, 2002). Because children may be exposed to multiple family risk factors, we sought to differentiate between these effects. In addition to the effects of parental psychopathology, parenting, and negative affect, we also included major disruption in the family environment as a predictor. Previous research has shown that families with depressed or alcoholic parents also experience elevated stressful life events compared to families without parental psychopathology, which is related to increased risk for both adolescent internalizing and externalizing symptoms (e.g., Su et al., 1997). Because the effects of adverse life events on adolescent functioning have already been extensively studied in previous research (see Grant et al., 2006, for review), our study sought only to control for major disruption in the family environment when testing hypotheses; excluding this variable from analyses could potentially overestimate the influence of parental negative affect and other variables of interest.

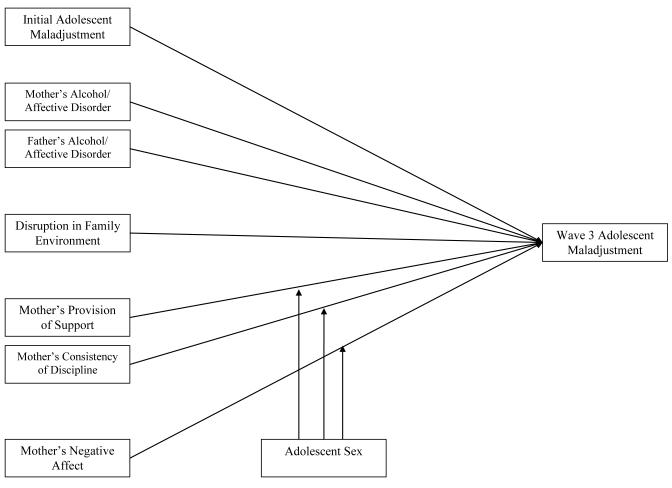

This is the first study to longitudinally examine the unique influence of parental negative affect on adolescent outcomes, separate from both parenting and parental psychopathology. The effects of these risk factors in both mothers and fathers were examined in separate models. Please see Figure 1 for a depiction of the hypothesized model for maternal effects. The primary hypothesis of the present study was that parental negative affect would uniquely and prospectively predict adolescent maladjustment (internalizing symptoms, externalizing symptoms, and negative emotionality), over and above the influences of parental diagnoses of alcohol and affective disorders, major disruption in the family environment, and parenting (provision of support and consistency of discipline). In addition, we hypothesized that parental negative affect would more strongly predict adolescent internalizing symptoms and negative emotionality in girls compared to boys. Finally, we also hypothesized that poor parental provision of support and consistency of discipline would be more strongly linked to maladjustment in same-sex parent-child pairs.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized model for the mother subsample (N=416). All predictors were assessed at Wave 1. Three adolescent maladjustment outcome variables were tested separately: internalizing symptoms, externalizing symptoms, and negative emotionality. For the father subsample analyses (N=346), fathers’ rather than mothers’ provision of support, consistency of discipline, and negative affect were entered into the model.

Method

Participants

Participants were drawn from a larger ongoing longitudinal study of familial alcoholism (e.g., Chassin, Barrera, Bech, and Kossak Fuller, 1992). At Wave 1 (1988), the total sample consisted of 454 “target” adolescents and their parents; 246 of these adolescents had at least one biological alcoholic parent who was also a custodial parent (COAs), and the remaining 208 adolescents were demographically matched controls without an alcoholic parent. All families were interviewed annually for three consecutive years. At Wave 2 (1989), 449 (99%) of the original families participated. At Wave 3 (1990), 444 (98%) of the original families participated.

Participants in the current analyses were families who participated at both Wave 1 and Wave 3, and who had complete data on all relevant measures.1 One adolescent from each family, who was between the ages of 11 to 15 years-old and closest to age 13, was assessed. Separate subsamples were used to test mother (N=416) and father (N=346) effects in order to retain single parent families. Therefore, adolescents from two-parent families in which both parents were interviewed were included in both subsamples. The mean age of adolescents was approximately 13.2 at Wave 1 and 15.2 at Wave 3. The mean age of mothers was 39.0 at Wave 1 and 41.0 at Wave 3, and the mean age of fathers was 41.3 at Wave 1 and 43.0 at Wave 3. Approximately half of adolescents (46-47%, depending on the subsample) were female and had at least one alcoholic parent (52-54%). Most adolescents (72-73%) were non-Hispanic Caucasian, and the rest were almost all Hispanic. The majority of parents were also non-Hispanic Caucasian (76-80% of mothers, 70-77% of fathers). Most adolescents (67% and 78% in the mother and father subsamples, respectively) had parents with some post-high school education.

Recruitment

Alcoholic families were recruited using court records, HMO questionnaires, and community telephone surveys. To qualify, parents had to live in Arizona, be of non-Hispanic Caucasian or Hispanic ethnicity, and be born between 1926 and 1960. DSM-III diagnoses of lifetime parental alcoholism (abuse or dependence) were made during an in-person structured diagnostic interview using the DIS-III (Robins et al., 1981). Parents who refused to participate were diagnosed based on spousal report using the Family History-Research Diagnostic Criteria (FH-RDC, Endicott et al., 1975). 219 biological fathers and 59 biological mothers met DSM-III criteria for alcoholism. Matched non-alcoholic families (matched on child age, family structure, ethnicity, and SES) residing in the same neighborhoods as the COA families were recruited.

Recruitment biases

The two primary sources of potential recruitment biases for the longitudinal study were selective contact with COA participants, and refusal to participate in the study. Potential participants who were contacted did not differ from those who were not contacted on alcoholism indicators, but those who were not contacted were more likely to be younger, from court sources, Hispanic, unmarried, and were more likely to have a lower SES rating associated with their residence. People who refused to participate were more likely than were participants to be Hispanic and married, but did not differ from participants on age, sex, SES, or alcoholism. See Chassin et al. (1992) for a complete description of sample recruitment.

Procedure

After parents provided informed consent and adolescents provided assent, interviews were conducted in-person using computer-assisted interviews, or via telephone for out of state families. To encourage self-disclosure, family members were interviewed in separate rooms and a Department of Health and Human Services Certificate of Confidentiality was provided.

Measures

See Tables 1 and 2 for descriptive statistics and correlations among variables.

Table 1.

Mother Subsample: Correlations among Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Mother alcohol/affective disordera | — | .155** | .379** | −.062 | −.124* | .096 | .078 | .127** | .200** | .110* | .117* | .187** | .179** |

| 2. Father alcohol/affective disordera | — | .172** | .027 | −.140** | .162** | .005 | .107* | .140** | .129** | .131** | .073 | .142** | |

| 3. Mother’s negative affect | — | −.141** | −.176** | .093 | .084 | .209** | .256** | .254** | .207** | .199** | .262** | ||

| 4. Mother’s provision of support | — | .435** | −.056 | .109* | −.282** | −.198** | −.395** | −.263** | −.207** | −.151** | |||

| 5. Mother’s consistency of discipline | — | −.086 | .011 | −.316** | −.297** | −.433** | −.276** | −.237** | −.242** | ||||

| 6. Major disruption in family environmentb | — | −.010 | .096 | .032 | .119* | .078 | .053 | .066 | |||||

| 7. Adolescent sexc | — | .138** | .231** | −.064 | −.118* | .101* | .193** | ||||||

| 8. Adolescent W1 internalizing | — | .542** | .629** | .360** | .524** | .380** | |||||||

| 9. Adolescent W3 internalizing | — | .398** | .483** | .346** | .486** | ||||||||

| 10. Adolescent W1 externalizing | — | .595** | .457** | .364** | |||||||||

| 11. Adolescent W3 externalizing | — | .258** | .460** | ||||||||||

| 12. Adolescent W1 negative emotionality | — | .505** | |||||||||||

| 13. Adolescent W3 negative emotionality | — | ||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Mean | 77 (19%) meet dx. |

208 (50%) meet dx. |

2.35 | 3.69 | 3.99 | 114 (27%) yes |

193 (46%) female |

2.13 | 2.06 | 1.64 | 1.68 | 2.79 | 2.81 |

| SD | .73 | .78 | .62 | .72 | .71 | .50 | .51 | .69 | .66 | ||||

| Range | 1.0-5.3 | 1.0-5.0 | 2.2-5.0 | 1.0-4.3 | 1.0-4.5 | 1.0-4.0 | 1.0-4.0 | 1.3-4.9 | 1.0-4.7 | ||||

Note. N=416,

p<.01,

p<.05.

All continuous variables are coded such that high scores indicate high levels of the variable.

−.5= No lifetime alcohol or affective disorder diagnosis, .5= Meets lifetime alcohol and/or affective disorder diagnosis.

−.5= No major disruption in the family environment, .5= Major disruption occurred within past 3 months.

−.5=Males, .5=Females.

Table 2.

Father Subsample: Correlations among Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Father alcohol/affective disordera | — | .089 | .152** | −.019 | −.114* | .070 | −.004 | .064 | .106* | .156** | .154** | .056 | .106* |

| 2. Mother alcohol/affective disordera | — | .100 | .008 | −.022 | .104 | .042 | .109* | .109* | .074 | .035 | .183** | .077 | |

| 3. Father’s negative affect | — | −.099 | −.168** | .148** | −.062 | .159** | .103 | .249** | .164** | .188** | .122* | ||

| 4. Father’s provision of support | — | .376** | −.055 | −.118* | −.260** | −.190** | −.355** | −.228** | −.149** | −.142** | |||

| 5. Father’s consistency of discipline | — | −.086 | −.099 | −.337** | −.267** | −.378** | −.248** | −.242** | −.231** | ||||

| 6. Major disruption in family environmentb | — | −.004 | .098 | −.011 | .079 | .042 | .065 | .015 | |||||

| 7. Adolescent sexc | — | .148** | .178** | −.040 | −.116* | .082 | .194** | ||||||

| 8. Adolescent W1 internalizing | — | .560** | .640** | .340** | .558** | .385** | |||||||

| 9. Adolescent W3 internalizing | — | .424** | .495** | .358** | .476** | ||||||||

| 10. Adolescent W1 externalizing | — | .552** | .510** | .325** | |||||||||

| 11. Adolescent W3 externalizing | — | .250** | .438** | ||||||||||

| 12. Adolescent W1 negative emotionality | — | .479** | |||||||||||

| 13. Adolescent W3 negative emotionality | — | ||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Mean | 62 (18%) meet dx. |

179 (52%) meet dx. |

2.20 | 3.45 | 4.09 | 94 (27%) yes |

163 (47%) female |

2.14 | 2.06 | 1.65 | 1.69 | 2.79 | 2.79 |

| SD | .70 | .87 | .66 | .73 | .68 | .48 | .51 | .71 | .64 | ||||

| Range | 1.2-4.7 | 1.0-5.0 | 2.1-5.0 | 1.0-4.3 | 1.0-4.5 | 1.0-3.5 | 1.0-4.0 | 1.3-4.9 | 1.0-4.7 | ||||

Note. N=346,

p<.01,

p<.05.

All continuous variables are coded such that high scores indicate high levels of the variable.

−.5=No lifetime alcohol or affective disorder diagnosis, .5= Meets lifetime alcohol and/or affective disorder diagnosis.

−.5= No major disruption in the family environment, .5= Major disruption occurred within past 3 months.

−.5=Males, .5=Females.

Adolescent sex

In the main analyses, sex was contrast coded such that “−.5” indicated male and“+.5” indicated female so that the first-order effect of the parent variable (negative affect, provision of support, or consistency of discipline) pertained to both sexes. In subsequent post-hoc probing of interactions, dummy codes were used for sex so that the first-order effect of the parent variable pertained only to the group coded 0 when the sex by parental negative affect interaction was included in the regression equation. Dummy codes were then reversed to examine the effect for the other sex (see Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003).

Mothers’ and fathers’ alcoholism and affective disorder diagnoses

DSM-III2 criteria were used to determine lifetime diagnoses of alcohol disorder (either abuse or dependence) and affective disorder (either major depression or dysthymia) at Wave 1 for mothers and fathers, separately, based on self-report responses to a computerized version of the DIS, Version 3 (Robins et al., 1981).3 Because we wished to test the influence of maternal/paternal negative affect over and above these disorders in both parents, the present study included measures of both parents’ psychopathology, even when one was not interviewed. To determine whether a non-interviewed parent may have met criteria for lifetime alcohol disorder, diagnoses were obtained using the Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria (FH-RDC) (Endicott et al., 1975), which have shown excellent specificity (92%) and sensitivity (90%) for wives reporting on their husbands’ substance disorders (Kosten, Anton, & Rounsaville, 1992). There were 3 mothers in the father subsample and 41 fathers in the mother subsample diagnosed with alcoholism via the FH-RDC. To determine lifetime affective disorder diagnoses for missing parents, we used responses to the question “has the child’s other parent had mental or emotional problems requiring treatment.” If the interviewed parent answered “yes,” the missing parent was considered to meet criteria for a lifetime diagnosis of affective disorder. We used this method to diagnose 8 mothers in the father subsample and 8 fathers in the mother subsample with affective disorders. Although this procedure provides the most conservative test of our study hypothesis (i.e., the unique effect of parental negative affect), we also conducted analyses using only self-report for diagnoses of affective disorders with results identical to those presented below.

Separate contrast-coded variables were created for mothers and fathers, such that “.5” indicates the mother (father) met lifetime criteria for an alcohol or affective disorder and “−.5” indicates that she (he) never met lifetime criteria for either of these diagnoses. Separate analyses entered alcoholism and affective diagnoses separately, rather than as aggregate variables for each parent. Results were consistent. For purposes of parsimony and because large numbers of predictors lowers the power of statistical tests for individual predictors, we report results with affective disorder and alcohol disorder aggregated into a single variable.

There were 77 (18.5%) mothers and 208 fathers (50.0%) with an alcohol or affective disorder in the mother subsample. There were 62 (17.9%) mothers and 179 fathers (51.7%) with an alcohol or affective disorder in the father subsample. In the mother subsample, there were 53 (13%) alcoholic mothers, 196 (47%) alcoholic fathers, 39 (9%) depressed mothers, and 39 (9%) depressed fathers. In the father subsample, there were 31 (9%) alcoholic mothers, 175 (51%) alcoholic fathers, 40 (11.6%) depressed mothers, and 22 (6%) depressed fathers. There was low prevalence of comorbidity between alcohol and affective disorders. The mother subsample had 15 (4%) mothers and 22 fathers (7%) with comorbidity, and the father subsample had 9 (3%) mothers and 18 (5%) fathers with comorbidity.

Mother/Father negative affect

Parental self-report of negative affect at Wave 1 was measured with a composite of 30 items, which was designed to assess multiple components of negative affect—dysphoria, anxiety, and irritability/anger. 10 items assessed each of these three aspects of negative emotions. There were 22 items from the negative affect scale from Veit and Ware’s (1983) Mental Health Inventory (e.g., “how much of the time have you been moody or brooded about things”). However, because these items largely captured symptoms of dysphoria and anxiety, we chose to also include 8 items from the negative emotionality subscale from Buss and Plomin’s (1984) EASI temperament survey (e.g., “there are many things that annoy me”) in order to also adequately assess irritability/anger.4 The 30 items in the final composite were coded such that higher scores indicated higher negative affect. Cronbach’s alpha was .95 in the mother subsample and .93 in the father subsample, indicating good internal consistency. The correlations between the negative affect composite and self-report affective disorder diagnosis (.31 for mothers and .26 for fathers) were small to moderate in magnitude (Cohen, 1988), suggesting that negative affect and affective disorders are indeed separate constructs. That is, negative affect is a component of an affective disorder but is insufficient for a diagnosis.

To ensure that the parental negative affect measure was constructed appropriately, principal component analyses (PCA) were conducted separately for mothers and fathers. In order to determine the number of factors that should be retained, the Kaiser criterion (extract eigenvalues > 1), Cattell’s (1966) scree test, and Velicer’s revised minimum average partial (MAP) test were conducted using syntax provided by O’Connor (2000). The MAP test has been shown to be considerably more accurate than using the Kaiser criterion or scree plots (Velicer, Eaton, & Fava, 2000). Although the maternal negative affect PCA yielded 4 eigenvalues greater than 1 (13.45, 1.66, 1.28, 1.09) and the paternal negative affect PCA yielded 6 eigenvalues greater than 1 (11.89, 1.64, 1.35, 1.25, 1.19, 1.04), both the scree test and the MAP test both supported a one factor solution. Accordingly, a single negative affect factor was extracted from the data. The maternal negative affect factor explained 45% of the variance in the items, whereas the paternal negative affect factor explained 40% of the variance in the items.

Major disruption in the family environment

A contrast-coded variable indicating major disruption in family environment within the past 3 months at Wave 1 was created using 3 items assessing whether a parent was arrested, a parent lost his/her job, or a close family member died. The variable was coded “.5” if one of these events occurred and “−.5” if none occurred.

Mother/Father provision of support to adolescent

Adolescents reported separately on their parents’ provision of social support in the past three months at Wave 1 using 6 items (range 1-5) from Furman and Buhrmester’s (1985) Network of Relationships Inventory (e.g., “how much can you count on Mom [Dad] to be there when you need her [him] no matter what). High scores indicated high levels of support. Cronbach’s alpha was .80 for mothers and .83 for fathers.

Mother/Father consistency of discipline

Adolescents reported separately on each parent’s consistency of discipline in the past 3 months at Wave 1 using 10 items (range 1-5) from Schaefer’s (1965) Children’s Report of Parental Behavior Inventory (e.g., “Mom [Dad] frequently changed the rules I was supposed to follow”). High scores indicated high consistency of discipline. Cronbach’s alpha was .79 for report about mothers and .83 for report about fathers.

Adolescent internalizing and externalizing symptomology

Adolescents self-reported on their internalizing (11 items) and externalizing (22 items) symptoms during the past 3 months at both Waves 1 and 3 using items adapted from Achenbach and Edelbrock’s (1979; 1981) Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL). Note that data were collected in 1988, and thus the CBCL items and response scale used in this study differ from the current version of the CBCL. Our measure has fewer items than the current CBCL and Youth Self-Report (YSR). Items were selected to optimize reliability estimates, and were previously determined to load equally for boys and girls on internalizing and externalizing factors. In addition, the response scale in our measure was expanded to range from 1 to 5 instead of 1 to 3 in order to increase variance, and was recoded so that high scores indicated high levels of symptomology.5 Cronbach’s alphas for internalizing symptomology (e.g., “I felt I had to be perfect”) ranged from .86 to .88 across waves and subsamples. Cronbach’s alphas for externalizing symptomology (e.g., “I argued a lot”) ranged from .88 to .90 across waves and subsamples. In order to evaluate the predictive validity of adolescent internalizing and externalizing symptoms, we examined correlations between Wave 3 internalizing/externalizing and DSM-III-R diagnoses of psychopathology at Wave 4 (5 year follow-up). Higher levels of internalizing and externalizing symptoms were significantly correlated with diagnoses of major depression, anxiety disorders, alcohol disorders, and drug disorders at Wave 4 (all p’s < .05). Higher levels of externalizing symptoms were also significantly associated with diagnoses of antisocial personality disorder.

Adolescent negative emotionality

Adolescents’ negative emotionality was assessed at Waves 1 and 3 with 9 items from Buss and Plomin’s (1984) EASI temperament survey (e.g., “I frequently get distressed”). High scores (range 1-5) indicated high levels of negative emotionality. Cronbach’s alphas ranged from .70 to .73 across waves and subsamples. In support of the validity of this measure, correlations with follow-up diagnoses of psychopathology indicated that higher levels of Wave 3 adolescent negative emotionality was significantly associated with diagnoses of major depression, anxiety disorders, and drug disorders at Wave 4.

Results

Tables 1 and 2 show zero-order correlations among variables for the mother and father subsamples, respectively. Higher levels of both maternal and paternal negative affect at Wave 1 were correlated with higher levels of all three adolescent maladjustment outcomes (all p’s < .05), except for the non-significant correlation between paternal negative affect and internalizing symptoms. As expected, parental diagnoses of alcohol/affective disorders were associated with higher levels of negative affect (rmothers = .38; rfathers = .15, p’s < .01). Higher levels of maternal negative affect were associated with lower levels of both maternal provision of support and consistency of discipline (see Table 1), whereas higher levels of paternal negative affect were associated with lower levels of paternal consistency of discipline only (see Table 2).

Multiple Regression Analyses

A series of ordinary least squares regressions predicting three measures of adolescent maladjustment (internalizing symptoms, externalizing symptoms, and negative emotionality) were conducted with separate models for mothers and fathers. For all regression analyses, the outcome variable was measured at Wave 3, and the Wave 1 measure of the outcome was entered onto the first step of the model in order to establish temporal precedence. Although analyses were conducted separately for mothers and fathers, we controlled for diagnoses of alcohol and affective disorders in both parents. For the mother subsample analyses, we examined the unique effect of maternal negative affect over and above the following Wave 1 measures: the initial measure of the outcome variable (step 1), adolescent sex (step 2), mothers’ and fathers’ alcohol/affective disorders (step 3), major disruption in the family environment (step 4), maternal provision of support and consistency of discipline (step 5), maternal negative affect (step 6), and the adolescent sex by maternal negative affect interaction term (step 7). For the father subsample analyses, the measures of paternal rather than maternal provision of support, consistency of discipline, and negative affect were entered, as well as the adolescent sex by paternal negative affect interaction term. All variables were centered (deviated from their means) before computing interactions in order to reduce nonessential multicollinearity (Cohen et al., 2003).

Preliminary analyses tested for interactions between adolescent sex and predictors for each outcome variable in each subsample. There was a significant interaction between adolescent sex and maternal provision of support in the mother subsample analysis predicting externalizing symptoms, and significant interactions between adolescent sex and paternal provision of support in the father subsample analyses predicting both internalizing and externalizing symptoms. These interactions were entered into the main analyses for the outcome variable on the seventh step (with the sex by parental negative affect interaction). Because we hypothesized a significant interaction between adolescent sex and parental negative affect, this interaction was always retained in the main analyses regardless of significance in preliminary testing. However, non-significant interactions between adolescent sex and the parenting variables were trimmed from the final analyses because these interactions were of secondary interest and large numbers of predictors lowers the power of tests for individual predictors. Note that there were no significant interactions between adolescent sex and maternal or paternal alcohol/affective disorder.

Three additional demographic variables—adolescent age, ethnicity, and parent education—were considered as potential covariates. However, none of these potential covariates were correlated with the outcome variables when controlling for the Wave 1 measures of maladjustment. However, interactions between predictors and these demographic variables were tested in preliminary analyses, which were all non-significant. Thus, all demographic variables other than adolescent sex were trimmed from the final analyses. Regression diagnostics revealed no influential data points for any regression models in the present study, and the Variance Inflation Factors indicated no problems with multicollinearity. All betas below are standardized.

Mother subsample analyses

We first tested whether maternal negative affect uniquely predicted adolescent internalizing symptoms at Wave 3 over and above Wave 1 internalizing symptoms, adolescent sex, parental diagnoses of alcoholism/affective disorder, major disruption in the family environment, maternal provision of support, and maternal consistency of discipline. At the final step of the regression model (R2 = .37, p < .01), the partial regression coefficients indicated that high Wave 1 internalizing symptoms, female sex, low maternal consistency of discipline, and high maternal negative affect all predicted significantly higher Wave 3 adolescent internalizing symptoms (see Table 3; all p’s < .05). All other predictors were non-significant.6 Results thus confirmed that higher levels of maternal negative affect uniquely predicted increases in internalizing symptoms (β= .10, sr2= .01, p < .05). Although the sex by maternal negative affect interaction term exceeded the conventional .05 significance level (β= .06, p=.11), power analyses conducted using G*Power 3 (Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, 2007) indicated that power was inadequate to detect small moderated effects. Because effect sizes for interaction terms in psychology tend to be small (Champoux & Peters, 1987) and the current study was underpowered to detect small moderated effects we conducted post-hoc probing of this interaction, which indicated that the prospective effect of maternal negative affect on internalizing symptoms was significant for females only (females: β= .16, sr2= .01, p < .01).

Table 3.

Mother Subsample: Results of Regression Models Predicting Adolescent Maladjustment Variables at Wave 3

| Outcome variable: Wave 3 measure of adolescent maladjustment |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internalizing symptoms |

Externalizing symptoms |

Negative emotionality |

||||

| Wave 1 variable | B(SE) | β | B(SE) | β | B(SE) | β |

| (Constant) | 1.79(.25) | .75(.19) | 2.16(.25) | |||

| Wave 1 measure of maladjustment | .43(.04) | .44** | .57(.05) | .56** | .41(.04) | .43** |

| Adolescent sex | .22(.06) | .16** | −.09(.04) | −.09* | .19(.06) | .14** |

| Mother alcohol/affective disorder | .14(.08) | .08+ | .05(.06) | .04 | .02(.08) | .01 |

| Father alcohol/affective disorder | .08(.06) | .06 | .04(.04) | .04 | .09(.06) | .07+ |

| Major disruption in family environment | −.08(.06) | −.05 | .00(.05) | .00 | .02(.06) | .01 |

| Mother’s provision of support | −.02(.04) | −.02 | −.01(.03) | −.02 | −.01(.04) | −.01 |

| Mother’s consistency of discipline | −.13(.05) | −.12* | .00(.04) | .00 | −.11(.05) | −.10* |

| Mother’s negative affect | .09(.04) | .10* | .03(.03) | .04 | .11(.04) | .13** |

| Sex by mother’s negative affecta | .12(.08) | .06+ | −.05(.06) | −.04 | n/a | n/a |

| Sex by provision of supportb | n/a | n/a | −.12(.05) | −.09* | n/a | n/a |

|

| ||||||

| Δ R2 for mother’s negative affect | .01* | .00 | .01** | |||

| Total R2 for model | .37** | .38** | .32** | |||

Note. N=416,

p<.01,

p<.05,

p <.11.

Values are based on results at the final step of the regression model. Sex is coded −.5= males, +.5= females.

The non-significant sex by negative affect interaction was trimmed from the model predicting negative emotionality.

Preliminary analyses indicated a significant interaction between sex and mother’s provision of support for the model predicting externalizing symptoms.

We next tested the unique effect of maternal negative affect on adolescent externalizing symptoms. At the final step of the regression model (R2 = .38, p < .01), the partial regression coefficients indicated that high Wave 1 externalizing symptoms, male sex, and the sex by maternal provision of support interaction all predicted significantly higher Wave 3 externalizing symptoms (see Table 3; all p’s < .05). All other predictors were non-significant. Post-hoc probing of the significant sex by maternal provision of support interaction (β = −.09, sr2= .01, p < .05) indicated non-significant effects of maternal provision of support for both males and females. Contrary to hypotheses, both the main effect of maternal negative affect (β = .04) and the sex-moderated effect of negative affect (β= −.04) were non-significant.

Finally, we tested the unique effect of maternal negative affect on adolescent negative emotionality. At the final step of the model (R2 = .32, p < .01), the partial coefficients indicated that high Wave 1 negative emotionality, female sex, low maternal consistency of discipline, and high maternal negative affect all predicted significantly higher Wave 3 negative emotionality (see Table 3; all p’s < .05). All other predictors were non-significant.7 Thus, higher levels of maternal negative affect uniquely predicted increases in negative emotionality for both sexes (β= .13, sr2= .01, p < .01). Sex did not moderate the effect of maternal negative affect.

Father subsample analyses

We first tested the unique effect of paternal negative affect on adolescent internalizing symptoms at Wave 3. At the final step of the regression model (R2 = .36, p < .01), the partial regression coefficients indicated that high Wave 1 internalizing symptoms, female sex, and the sex by paternal provision of support interaction all predicted significantly higher Wave 3 internalizing symptoms (see Table 4; all p’s < .05). All other predictors were non-significant. Post-hoc probing of the significant sex by paternal provision of support interaction (β= −.13, sr2= .01, p < .01) indicated that low paternal provision of support predicted increases in internalizing symptoms for females only (females: β= −.15, sr2= .01, p < .05). Contrary to hypotheses, both the main effect of paternal negative affect (β= .02) and the sex-moderated effect of negative affect (β= .06) were non-significant.

Table 4.

Father Subsample: Results of Regression Models Predicting Adolescent Maladjustment Variables at Wave 3

| Outcome Variable: Wave 3 measure of adolescent maladjustment |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internalizing symptoms |

Externalizing symptoms |

Negative emotionality |

||||

| Wave 1 variable | B(SE) | β | B(SE) | β | B(SE) | β |

| (Constant) | 1.33(.25) | .89(.20) | 2.11(.26) | |||

| Wave 1 measure of maladjustment | .47(.05) | .51** | .54(.05) | .51** | .39(.04) | .44** |

| Adolescent sex | .13(.06) | .09* | −.10(.05) | −.10** | .19(.06) | .15** |

| Father alcohol/affective disorder | .08(.06) | .06 | .07(.05) | .07 | .09(.06) | .07 |

| Mother alcohol/affective disorder | .07(.08) | .04 | −.02(.06) | −.02 | −.03(.08) | −.02 |

| Major disruption in family environment | −.12(.07) | −.08 | −.01(.05) | −.01 | −.04(.07) | −.03 |

| Father’s provision of support | −.02(.04) | −.02 | −.03(.03) | −.05 | −.02(.04) | −.02 |

| Father’s consistency of discipline | −.07(.05) | −.07 | −.03(.04) | −.03 | −.09(.05) | −.09 |

| Father’s negative affect | .03(.05) | .02 | .03(.04) | .03 | .03(.05) | .03 |

| Sex by father’s negative affecta | .11(.09) | .06 | .13(.07) | .09+ | n/a | n/a |

| Sex by provision of supportb | −.20(.07) | −.13** | −.11(.05) | −.09* | n/a | n/a |

|

| ||||||

| Δ R2 for father’s negative affect | .00 | .00 | .00 | |||

| Total R2 for model | .36** | .34** | .27** | |||

Note. N=346,

p<.01,

p<.05,

p < .08.

Values are based on results at the final step of the regression model. Gender is coded −.5= males, +.5= females.

The non-significant gender by negative affect interaction was trimmed from the model predicting negative emotionality.

Preliminary analyses indicated significant interactions between gender and father’s provision of support for the models predicting internalizing and externalizing symptoms.

Next, we tested the unique effect of paternal negative affect on adolescent externalizing symptoms at Wave 3. At the final step of the regression model (R2 = .34, p < .01), the partial regression coefficients indicated that high Wave 1 externalizing symptoms, male sex, and the sex by paternal provision of support interaction all predicted significantly higher Wave 3 externalizing symptoms (see Table 4; all p’s < .05). All other predictors were non-significant. Post-hoc probing of the sex by paternal provision of support interaction (β= −.09, sr2= .01, p < .05) indicated that low paternal provision of support predicted increases in externalizing symptoms for girls only (females: β= −.14, sr2= .01, p < .05). Although there was a marginally significant sex by paternal negative affect interaction (β= −.13, sr2= .01, p = .07), post-hoc probing indicated that the simple slopes were non-significant for both male and females. The unique main effect of paternal negative affect (β=.03) was also non-significant.

Finally, we tested the unique effect of paternal negative affect on adolescent negative emotionality at Wave 3 (R2 = .27, p < .01). There were significant effects of Wave 1 negative emotionality and female sex (see Table 4; all p’s < .05). All other predictors were non-significant. Neither the main effect of paternal negative affect (β= .03) nor the sex moderated effect of paternal negative affect (β= .00) predicted increases in negative emotionality.

Discussion

The current study hypothesized that parental negative affect would prospectively influence adolescent maladjustment, separate from parental alcohol/affective disorders, major disruption in the family environment, and parenting. We also hypothesized that parental negative affect would more strongly predict internalizing symptoms and negative emotionality in girls compared to boys. There was support for these hypotheses for the effects of maternal negative affect. Specifically, maternal negative affect uniquely predicted increases in adolescent girls’ internalizing symptoms and all children’s negative emotionality. Paternal negative affect had no significant unique main effects. Thus, one contribution of the present study is its identification of the unique effect of maternal negative affect over and above parenting and parental alcohol and affective disorders. This finding should not be taken to mean that parental psychopathology and parenting do not affect offspring adjustment. Rather, results showed that the impact of maternal negative affect on adolescent outcomes may not be fully captured by a mother’s parenting and the symptoms used to diagnose an affective or alcohol disorder.

The unique effect of maternal negative affect on adolescent internalizing symptoms is consistent with research showing that high levels of parental negative affect increases risk for offspring internalizing symptoms (e.g., Cummings et al., 2005). As described earlier, there are several explanations for this effect, including emotion contagion, perceived threat to family stability, decreased quality of the parent-child relationship, emotional dysregulation, and lack of coping skills (Cummings et al., 2005; Morris et al., 2007). Moreover, our findings that maternal negative affect predicted increased internalizing symptoms for girls only provides tentative support for the hypotheses that adolescent girls would be more vulnerable to parental negative affect compared to boys. Increased vulnerability to parental negative affect may partially contribute to the sex gap in the prevalence of depression (e.g., Crick & Zahn-Waxler, 2003).

The significant effect of maternal negative affect on adolescent negative emotionality, which did not differ for boys and girls, is particularly noteworthy given that negative emotionality is a risk factor for a variety of emotional and behavioral problems (e.g., Hankin & Abramson, 2001). Previous research has suggested that negative emotions in parents can cause children and adolescents to become highly emotionally reactive, which may increase risk for both internalizing and externalizing symptoms as well as other maladaptive outcomes (see Morris et al., 2007). Frequent exposure to parents’ negative affect during adolescence may be especially influential, given that emotion regulation skill are needed to manage increases in emotional and behavioral problems that tend to occur during adolescence (Kessler et al., 2001). Indeed, it has been suggested that internalizing and externalizing symptoms during adolescence reflect problems with emotion regulation and negative affect, whereas these problems during childhood are more likely to reflect struggles for independence (see Connell & Goodman, 2002).

Although parental negative affect did not significantly predict adolescent externalizing symptoms, findings nonetheless contribute to the literature on the association between parental negative affect and offspring externalizing symptoms. Although some research has suggested a direct effect of parental negative affect on offspring externalizing symptoms (e.g., Cummings et al., 2005), we do not know of any studies that have differentiated between parental negative affect and affective disorders when predicting offspring externalizing symptoms. Our study theorized that parental negative affect might be an important predictor of adolescent externalizing symptoms, over and above its association with other risk factors. However, our results did not find that this to be the case. Perhaps there are components of parental negative affect, such as anger, that may more strongly influence externalizing symptoms compared to the general negative affect factor in this study. Future studies should examine how specific types of parental negative affect may differentially affect adolescent adjustment for girls and boys.

There are several possible explanations for the significant effects of maternal but not paternal negative affect. First, because mothers are most often the primary caretaker and spend more time with children (Pleck, 1997), children may be more affected by maternal negative affect simply due to greater exposure. Second, psychological distress in women has been found to be more closely related to familial sources of stress and family discord (Connell & Goodman, 2002). Therefore, when there is family discord, maternal negative affect would be expected to be higher compared to paternal negative affect, and may thus exert influences on child maladjustment that extend beyond the influences of family discord. In addition, research has shown that mothers generally provide more emotion coaching than do fathers, and are typically more understanding of negative emotion in adolescents than are fathers (see Stocker et al, 2007). Yet, mothers who are high in negative affect have been found to dismiss, minimize, or react with hostility to negative emotion in their children, thus exacerbating the negative emotion (Morris et al., 2007). Therefore, adolescents with mothers who are high in negative affect may be missing out on critically important emotional guidance and acceptance, as this is typically provided by mothers rather than fathers. Mothers may also be less likely or able to conceal their negative affect compared to fathers (see Connell & Goodman, 2002). Finally, the smaller size of the father subsample compared to the mother subsample (and the associated lower statistical power) may explain why the effect of parental negative affect was significant for mothers but not for fathers.

Although not a focus of the current study, this study also examined the unique influence of parental provision of support and consistency of discipline on adolescent maladjustment, and whether these measures of parenting were more strongly linked to maladjustment in same-sex parent-child pairs. Although paternal provision of support uniquely predicted outcomes for girls, maternal provision of support had no effects on any of the outcomes for either sex. However, maternal consistency of discipline predicted lower internalizing symptoms and negative emotionality for both males and females, whereas paternal consistency of discipline had no unique effects. These findings are inconsistent with studies suggesting that the protective influence of parenting may be stronger for same-sex parent-child pairs (e.g., Deater-Deckard & Dodge, 1997; Hoeve et al., 2009). Yet, our findings that offspring sex moderated the influence of parenting may help to explain why studies have found that parenting has consistent but relatively small effects (e.g., McCleod et al., 2007; Rothbaum & Weisz, 1994). Future studies are needed to clarify how the protective influence of parenting may vary by both parent and child sex.

These findings contribute to the currently growing literature that examines the influence of fathers on offspring in addition to the influence of mothers. Past research has typically overlooked fathers when examining constructs such as parental support and emotion. In addition, our findings contributes to the large literature that examines how parents influence the adjustment of their children by delineating the effects of important parental risk factors that commonly co-occur with one another but are typically not examined within the same study. Thus, our study helps to clarify the unique influence of parental alcohol/affective disorders, parenting, and parental negative affect on adolescent maladjustment over and above their covariation with one another (while also controlling for disruption in the family environment). The fact that the effects of parental alcoholism/affective disorders were non-significant at the final step of the model for all outcome variables may indicate that the effects of parental psychopathology may be largely mediated through parenting, disruption in the family environment, and parental negative affect. It is somewhat surprising that so few parental risk factors were significant predictors of adolescent maladjustment. Perhaps more variance in outcomes would have been accounted for if we had examined how these parental risk factors may interact with risk factors that were outside of the scope of this study, such as the peer group.

Several limitations to the present study should be noted. First, the magnitude of the unique effect of negative affect on outcomes was quite small. However, given that the effects were significant above and beyond the effects of parental psychopathology, family disruption, and parenting, this was a conservative test and would not be expected to produce large effects. Second, negative affect was measured by a brief item set, and more comprehensive standardized or observational measures might produce stronger findings. Adolescents’ perceptions of parental negative affect might also produce larger effects. Third, this study was underpowered to detect interactions between adolescent sex and parental negative affect. Fourth, this study did not examine genes or gene-environment interactions. Genetic factors may interact with family risk and protective factors to influence adolescent outcomes. It is also possible that the relations between parental risk factors (e.g., negative affect, parenting) and adolescent outcomes may be accounted for by genetic similarity between parents and adolescents. Finally, this study did not attempt to test mediational relations among parental psychopathology, negative affect, parenting, or disruption in the family environment; this is an important direction for future research.

Despite these limitations, the current study suggests that mothers’ negative affect may uniquely influence adolescent maladjustment, whereas prior research has largely considered parental negative affect only as a correlate of parental psychopathology and/or parenting. The longitudinal design of the current study rules out the possibility of a reverse direction of effect—that is, the possibility that adolescent maladjustment causes elevations in parents’ negative affect. Past studies that have attempted to differentiate parental affect from parenting have often been cross-sectional and unable to prospectively predict outcomes. In addition, this study contributes to our understanding of the influence of parental emotion on adolescent children, given that past studies on parental affect have largely focused on younger children and infants, or have included adolescents in the same sample as younger children despite important developmental differences.

Our findings suggest that parental negative affect may be useful for explaining how parents without readily apparent parenting deficits may detrimentally influence their children. Interventions for parents with depression or alcoholism may benefit from targeting the emotional components that are associated with their problems in order to prevent intergenerational transmission of psychopathology, rather than focusing mostly on other symptoms and parenting. Although addressing emotion is inherently a part of interventions for affective disorders, this study indicates that it may be an important focus for interventions with alcoholic parents (specifically, mothers) as well. Prevention efforts for adolescents may benefit from explicitly addressing ways that adolescents can cope with their own and their parents’ negative affect.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse (NIAAA AA016213).

Footnotes

Compared to included adolescents, adolescents who were excluded from the mother subsample (N= 38) did not differ on sex but were significantly more likely to be Hispanic (χ2(1) = 11.69, p <.01), children of alcoholics (χ2(1) =10.24, p <.01), and children of less educated parents (t(452) = −1.99, p <.05). Compared to included adolescents, adolescents who were excluded from the father subsample (N= 108) did not differ on sex, ethnicity, or parental alcoholism, but were more likely to have less educated parents (t(452) = −5.15, p <.001).

Because DSM-III criteria tend to diagnose alcohol disorders less frequently than DSM-IV criteria (e.g., Langenbucher, Morgenstern, Labouvie, & Nathan, 1994), diagnoses of parental alcohol disorders in our study may be somewhat lower than if they had been made using DSM-IV criteria. DSM-III and DSM-IV criteria for depressive disorders are very similar—more similar, in fact, than DSM-III-R and DSM-IV diagnoses (Lafer, Nierenberg, Rosenbaum, & Fava, 1996)—and it is unlikely that our results would change if we had used DSM-IV diagnoses for affective disorders rather than DSM-III diagnoses.

Separate analyses added the effects of Wave 4 parental lifetime anxiety disorders (DSM-III-R criteria), which were not assessed at Wave 1. Results were consistent with the main analyses suggesting that the unique variance that was accounted for by parental negative affect in analyses could not be attributed to parental anxiety disorders.

Analyses were also conducted using a composite of only the 22 items from the negative affect scale from Veit and Ware’s (1983) Mental Health Inventory. Results were consistent.

In order to better understand our sample, we examined how many adolescents exhibited symptoms in the clinical range by using the 90th percentile of the (within-gender) control group scores as the cut-off (see Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1981). In the mother subsample, there were 62 (15%) adolescents at Wave 1 and 54 (13%) adolescents at Wave 3 with internalizing symptoms in the clinical range, and there were 53 (13%) adolescents at Wave 1 and 55 (13%) adolescents at Wave 3 with externalizing symptoms in the clinical range. In the father subsample, there were 54 (16%) adolescents at Wave 1 and 43 (12%) adolescents at Wave 3 with internalizing symptoms in the clinical range, and there were 41 (12%) adolescents at Wave 1 and 47 (14%) adolescents at Wave 3 with externalizing symptoms in the clinical range.

Parental alcohol/affective disorders were significant when initially entered into the model (ΔR2=.019, p < .01) and indicated a significant effect of maternal but not paternal alcohol/affective disorder, but neither coefficient was significant at the final step.

Parental alcohol/affective disorders was significant when initially entered into the model (ΔR2=.015, p < .05) and indicated a significant effect of paternal but not maternal alcohol/affective disorder, but neither coefficient was significant at the final step.

Contributor Information

Moira Haller, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University, moira.haller@asu.edu.

Laurie Chassin, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University, laurie.chassin@asu.edu.

References

- Achenbach T, Edelbrock C. The child behavior profile II: Boys aged 12-16 and girls aged 6-11 and 12-16. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1979;47(2):223–233. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach T, Edelbrock C. Behavioral problems and competencies reported by parents of normal and disturbed children aged 4-16. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1981;46 (1, Serial No. 188) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage Publications, Inc.; Thousand Oaks, CA, US: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social learning theory. Prentice-Hall; Oxford, England: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Berg-Nielsen TS, Vikan A, Dahl AA. Parenting related to child and parental psychopathology: A descriptive review of the literature. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;7(4):529–552. [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Brook DW, Gordon AS, Whiteman M. The psychosocial etiology of adolescent drug use: A family interactional approach. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs. 1990;116(2):111–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH, Plomin R. Temperament: Early Developing Personality Traits. Lawrence Erlbaum Association; Hillsdale, NJ: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Cattell RB. The scree test for the number of factors. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1966;1:245–276. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr0102_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champoux JE, Peters WS. Form, effect size and power in moderated regression analysis. Journal of Occupational Psychology. 1987;60(3):243–255. [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Barrera M, Bech K, Kossak-Fuller J. Recruiting a community sample of adolescent children of alcoholics: A comparison of three subject sources. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1992;53(4):316–319. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1992.53.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3rd ed Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; Mahwah, NJ, US: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Connell AM, Goodman SH. The association between psychopathology in fathers versus mothers and children’s internalizing and externalizing behavior problems: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128(5):746–773. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.5.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook W, Kenny D, Goldstein M. Parental affective style and the family system: A social relations model analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100(4):492–501. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Zahn-Waxler C. The development of psychopathology in females and males: Current progress and future challenges. Development and Psychopathology: Special Issue: Conceptual, Methodological, and Statistical Issues in Developmental Psychopathology. 2003;15(3):719–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Keller PS, Davies PT. Towards a family process model of maternal and paternal depressive symptoms: Exploring multiple relations with child and family functioning. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46(5):479–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson R, Jackson D, Kalin N. Emotion, plasticity, context, and regulation: Perspectives from affective neuroscience. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126(6):890–909. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.6.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies P, Windle M. Gender-specific pathways between maternal depressive symptoms, family discord, and adolescent adjustment. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:657–668. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.4.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge K. Externalizing behavior problems and discipline revisited: Nonlinear effects and variation by culture, context, and gender. Psychological Inquiry. 1997;8(3):161–175. [Google Scholar]

- Eiden R, Edwards E, Leonard K. Predictors of effortful control among children of alcoholic and nonalcoholic fathers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65(3):309–319. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J, Anderson N, Spitzer RL. Family History Diagnostic Criteria. New York Biometrics Research, New York Psychiatric Institute; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A, Buchner A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39(2):175–191. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Children’s perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology. 1985;21(6):1016–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Grant KE, Compas B, Thurm A, McMahon S, Gipson P, Campbell A, Krochock K, Westerholm R. Stressors and child and adolescent psychopathology: Evidence of moderating and mediating effects. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26(3):257–283. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halberstadt AG, Eaton K. A meta-analysis of family expressiveness and children’s emotion expressiveness and understanding. Marriage and Family Review. 2002;34:35–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hankin B, Abramson L. Development of gender differences in depression: An elaborated cognitive vulnerability-transactional stress theory. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127(6):773–796. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.6.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeve M, Dubas J. Semon, Eichelsheim V, van der Laan P, Smeenk W, Gerris J. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37:749–775. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9310-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izard CE, Fine S, Mostow A, Trentacosta C, Campbell J. Emotion processes in normal and abnormal development and preventive intervention. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14(4):761–787. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402004066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller PS, Cummings EM, Davies PT, Mitchell PM. Longitudinal relations between parental drinking problems, family functioning, and child adjustment. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20(1):195–212. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Merikangas KR. Mood disorders in children and adolescents: An epidemiologic perspective. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;49(12):1002–1014. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimes-Dougan B, Brand A, Zahn-Waxler X, Usher B, Hastings P, Kendziora K, et al. Parental emotion socialization in adolescence: Differences in sex, age, and problem status. Social Development. 2007;16(2):326–342. [Google Scholar]

- Kosten T, Anton S, Rounsaville B. Ascertaining psychiatric diagnoses with the family history method in a substance abuse population. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1992;26:135–147. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(92)90005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafer B, Nierenberg A, Rosenbaum J, Fava M. Outpatients with DSM-III-R versus DSM-IV melancholic depression. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1995;37(1):37–39. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(96)90048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenbucher J, Morgenstern J, Labouvie E, Nathan P. Diagnostic concordance of substance use disorders in DSM-III, DSM-IV, and ICD-10. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1994;36:193–203. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)90145-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy MC, Graczyk PA, O’Hare E, Neuman G. Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20(5):561–592. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE. The role of parents in the socialization of children: A historical review. Developmental Psychology. 1992;28:1006–1017. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod BD, Weisz JR, Wood JJ. Examining the association between parenting and childhood depression: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27:986–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod BD, Wood JJ, Weisz JR. Examining the association between parenting and childhood anxiety: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27:155–172. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris A, Silk J, Steinberg L, Myers S, Robinson L. The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Social Development. 2007;16(2):361–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00389.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor BP. SPSS and SAS programs for determining the number of components using parallel analysis and Velicer’s MAP test. Behavior Research Methods, Instrumentation, and Computers. 2000;32:396–402. doi: 10.3758/bf03200807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. Mothers: The unacknowledged victims. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1980;5:64. (serial no. 186) [Google Scholar]

- Pleck J. Paternal involvement: Levels, sources, and consequences. John Wiley & Sons Inc.; Hoboken, NJ, US: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan JL, Ratcliff KS. National institute of mental health diagnostic interview schedule: Its history, characteristics, and validity. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1981;38(4):381–389. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780290015001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum F, Weisz JR. Parental caregiving and child externalizing behavior in nonclinical samples: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:55–74. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell JA, Carroll JM. On the bipolarity of positive and negative affect. Psychological Bulletin. 1999;125:3–30. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarmella LV, Conger RD, Simons R. Parental protective influences and gender-specific increases in adolescent internalizing and externalizing problems. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1999;9(2):111–141. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer ES. Children’s reports of parental behavior: An inventory. Child Development. 1965;36(2):413–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. We know some things: Parent–adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11(1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Stocker CM, Richmond MK, Rhoades GK. Family emotional processes and adolescents’ adjustment. Social Development. 2007;2:310–325. [Google Scholar]

- Su S, Hoffmann J, Gerstein D, Johnson RA. The effect of home environment on adolescent substance use and depressive symptoms. Journal of Drug Issues. 1997;27(4):851–877. [Google Scholar]

- Veit CT, Ware JE. The structure of psychological distress and well-being in general populations. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1983;51(5):730–742. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.5.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velicer WF, Eaton CA, Fava JL. Construct explication through factor or component analysis: A review and evaluation of alternative procedures for determining the number of factors or components. In: Goffin RD, Helmes E, editors. Problems and Solutions in Human Assessment. Kluwer; Boston: 2000. pp. 41–71. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA. Negative affectivity: The disposition to experience aversive emotional states. Psychological Bulletin. 1984;96:465–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Weber K, Assenheimer JS, Clark LA, Strauss ME, McCormick RA. Testing a tripartite model: I. Evaluating the convergent and discriminant validity of anxiety and depression symptom scales. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104:3–14. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeman J, Klimes-Dougan B, Cassano M, Adrian M. Measurement issues in emotion research with children and adolescents. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2007;14:377–401. [Google Scholar]