Abstract

Whole genome comparisons identified introgression from archaic to modern humans. Our analysis of highly polymorphic HLA class I, vital immune system components subject to strong balancing selection, shows how modern humans acquired the HLA-B*73 allele in west Asia through admixture with archaic humans called Denisovans, a likely sister group to the Neandertals. Virtual genotyping of Denisovan and Neandertal genomes identified archaic HLA haplotypes carrying functionally distinctive alleles that have introgressed into modern Eurasian and Oceanian populations. These alleles, of which several encode unique or strong ligands for natural killer cell receptors, now represent more than half the HLA alleles of modern Eurasians and also appear to have been later introduced into Africans. Thus, adaptive introgression of archaic alleles has significantly shaped modern human immune systems.

Whether or not interbreeding occurred between archaic and modern humans has long been debated (1, 2). Recent estimates suggest that Neandertals contributed 1–4% to modern Eurasian genomes (3) and Denisovans, a likely sister group to the Neandertals, contributed 4–6% to modern Melanesian genomes (4). These studies, based upon statistical genome-wide comparisons, did not address if there was selected introgression of functionally advantageous genes (5). We explored if the highly polymorphic HLA class I genes (HLA-A, -B and -C) (fig. S1) of the human Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) are sensitive probes for such admixture. Because of their vital functions in immune defense and reproduction, as ligands for T cell and natural killer (NK) cell receptors, maintaining a variety of HLA-A, B and C proteins is critical for long-term human survival (6). Thus, HLA-A, -B and -C are subject to strong multi-allelic balancing selection, which with recombination imbues human populations with diverse HLA alleles and haplotypes of distinctive structures and frequencies (7).

An exceptionally divergent HLA-B allele is HLA-B*73:01 (8, 9). Comparison with the other >2,000 (10) HLA-B alleles and chimpanzee and gorilla alleles from the same locus (MHC-B) shows that HLA-B*73:01 is most closely related to subsets of chimpanzee and gorilla MHC-B alleles (11) (figs. S2–S4). This relationship extends throughout a ~9kb region of the B*73:01 haplotype (Fig. 1A), defining a deeply divergent allelic lineage (MHC-BII), distinct from the MHC-BI lineage to which other human HLA-B alleles belong. These two lineages diverged ~16 million years ago (Fig. 1B), well before the split between humans and gorillas, but while MHC-BI comprises numerous types and subtypes, MHC-BII is only represented in modern humans by B*73:01 (fig. S5). HLAB*73:01 combines ancient sequence divergence with modern sequence homogeneity, properties compatible with modern humans having recently acquired HLA-B*73:01 through introgression.

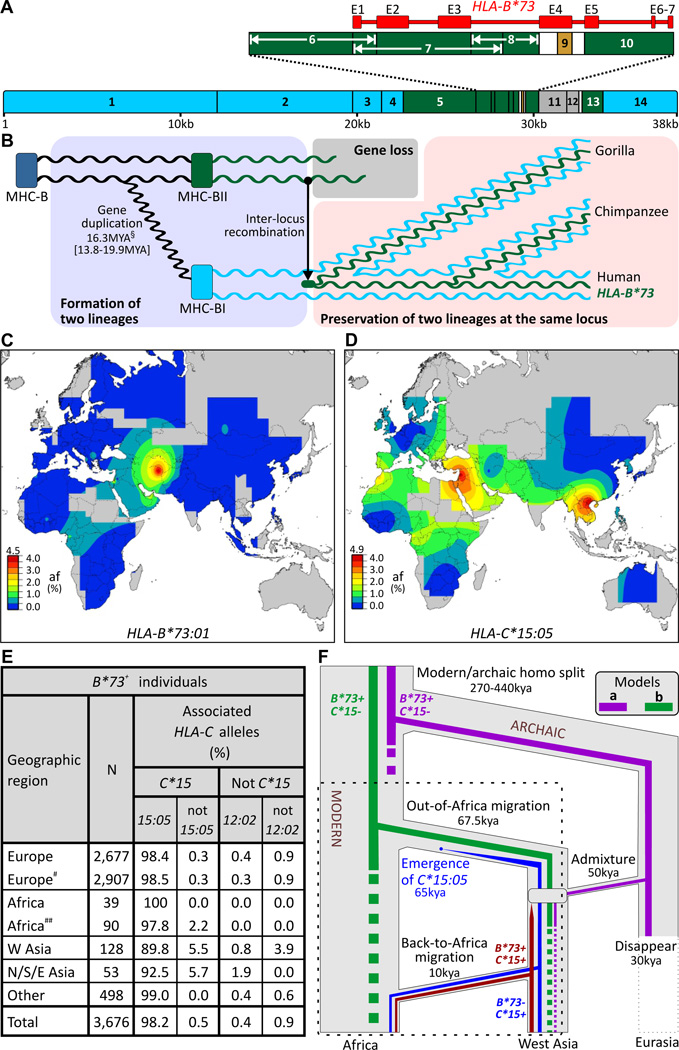

Fig.1.

Modern humans acquired HLA-B*73 from archaic humans. (A) The B*73 haplotype contains segments most closely related to chimpanzee and gorilla MHC-B alleles (green) and flanking segments highly related to other HLA-B (blue) (brown segment is related to HLA-C) (fig. S4). (B) B*73 ’s divergent core has its roots in a gene duplication that occurred >16 million years ago (MYA). (left to right) MHC-B duplicated and diverged to form the MHC-BI and BII loci. One allele of BII recombined to the BI locus giving rise to the ancestor of B*73 and its gorilla and chimpanzee equivalents. B*73 is thus the only remnant in modern humans of a deeply divergent allelic lineage. §, mean and 95% credibility interval. (C–E) B*73:01 is predominantly found outside Africa (C) as is C*15:05 (D), which is strongly associated with B*73 in 3,676 individuals worldwide (E). Individuals with the B*73 haplotype were categorized on the basis of their geographic origin, and status of the most-commonly linked (C*15) and second-most commonly linked (C*12:02) HLA-C alleles (fig. S24). # includes Hispanic-Americans, ## includes African-Americans. (C–D) Scale bars give allele frequency (af) categories (top number, highest tick mark). (F) Archaic admixture (model ‘a’) or African origin (model ‘b’) could explain the distribution and association of B*73 with C*15:05; simulations favor the former (α=0.01–0.001) (figs. S9–11) (11). The dotted box indicates the part of the models examined by simulation.

In modern humans, HLA-B*73 is concentrated in west Asia, and is rare or absent in other regions (12) (Figs. 1C, S6). This distribution is consistent with introgression of HLAB*73 in west Asia, a site of admixture between modern and archaic humans (3). Also consistent with introgression is the linkage disequilibrium (LD) between B*73:01 and HLA-C*15:05 (13), an allele having wider distribution than B*73, but concentrated in west and south-east Asia (Fig. 1D).

Worldwide, ~98% of people carrying B*73 also carry C*15:05 (Figs. 1E, S7). In Africans the LD reaches 100%, but in west Asians it is weaker (~90%). These data are all consistent with introgression in west Asia of an archaic B*73:01-C*15:05 haplotype which expanded in frequency there, before spreading to Africa and elsewhere. HLA-B*73 is absent from Khoisan-speaking and pygmy populations who likely diverged from other Africans before the Out-of-Africa migration (14); (fig. S8). That Khoisan and pygmies uniquely retain ancient mitochondrial and Y-chromosome lineages (14, 15), as well as MHC-BI diversity (fig. S8), suggest B*73 was probably not present in any African population at the time of the migration. These data argue for models in which modern humans acquired B*73 by archaic admixture in west Asia, and against models in which B*73 arose in Africa and was carried to other continents in the Out-of-Africa migration (Fig. 1F), as do the results of coalescence simulations that implement rejection-based approximate Bayesian inference (16) (α=0.01–0.001) (figs. S9–11).

By reanalyzing genomic sequence data (3, 4, 11), we characterized archaic HLA class I from a Denisovan and three Neandertals. The Denisovan’s two HLA-A and two HLA-C allotypes are identical to common modern allotypes, whereas one HLA-B allotype corresponds to a rare modern recombinant allotype and the other has never been seen in modern humans (Figs. 2B, S12). The Denisovan’s HLA type is thus consistent with an archaic origin and the known propensity for HLA-B to evolve faster than HLA-A and HLA-C (17, 18).

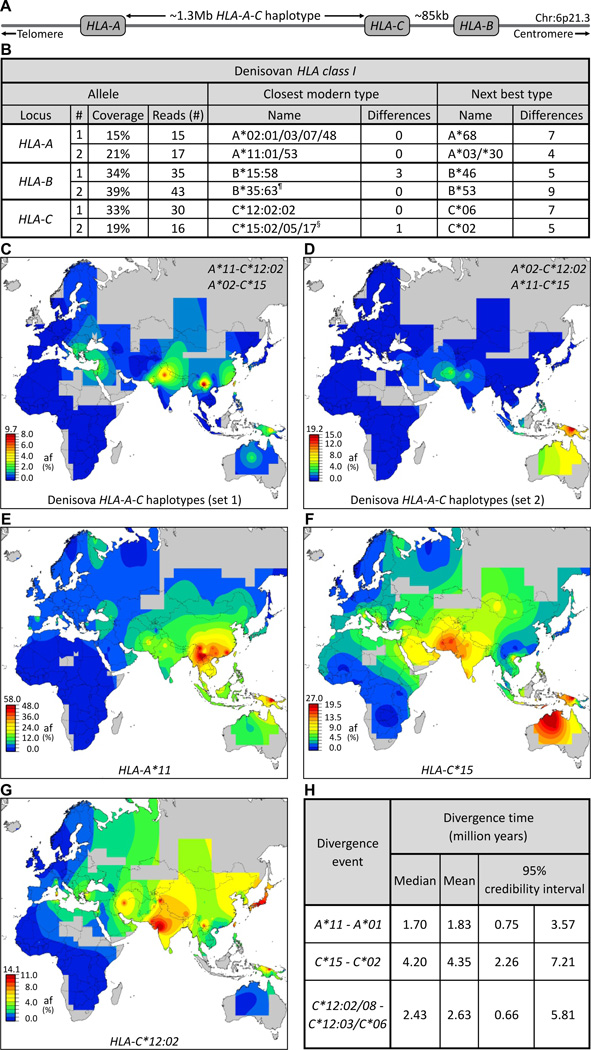

Fig.2.

Effect of adaptive introgression of Denisovan HLA class I alleles on modern Asian and Oceanian populations. (A) Simplified map of the HLA class I region showing the positions of the HLA-A, -B and -C genes. (B) Five of the six Denisovan HLA-A, -B and -C alleles are identical to modern counterparts. Shown at the left for each allele is the number of sequence reads (4) specific to that allele and their coverage of the ~3.5kb HLA class I gene. Center columns give the modern-human allele (HLA type) that has the lowest number of SNP mismatches to the Denisovan allele. The next most similar modern allele and the number of SNP differences are shown in the columns on the right. ¶, a recombinant allele with 5’ segments originating from B*40. §, the coding sequence is identical to C*15:05:02. (C–D) Show the worldwide distributions of the two possible Denisovan HLA-A-C haplotype combinations. Both are present in modern Asians and Oceanians but absent from Sub-Saharan Africans. (E–G) The distribution of three Denisovan alleles: HLA-A*11 (E), C*15 (F), and C*12:02 (G), in modern human populations shows they are common in Asians but absent or rare in Sub-Saharan Africans. (H) Estimation of divergence times shows that A*11, C*15 and C*12:02 were formed before the Out-of-Africa migration. Shown on the left are the alleles they diverged from, on the right are the divergence time estimates: median, mean, and range.

Not knowing the haplotype phase, we examined all possible combinations of Denisovan HLA-A and HLA-C for their current distribution worldwide. All four combinations are present in Asia and Oceania, but absent from Sub-Saharan Africa, and uncommon in Europe (Figs. 2C–D, S13). Genome-wide comparisons showed that modern and archaic non-African genomes share only ten long, deeply divergent haplotypes (3), which are all considerably shorter (100–160kb) than the ~1.3Mb HLA-A-C haplotype (Fig. 2A). Because modern HLA haplotypes diversify rapidly by recombination (17–19) it is improbable that the HLA-A-C haplotypes shared by modern humans and Denisovans were preserved on both lines since modern and Denisovan ancestors separated >250kya (~10,000 generations (4)). More likely is that modern humans acquired these haplotypes by recent introgression from Denisovans (note II.6 (11)). Both alternative haplotype pairs are common in Melanesians, reaching 20% frequency in Papua New Guinea (PNG), consistent with genome-wide assessment of Denisovan admixture in Melanesians (4). The current distribution of the Denisovan haplotypes (Figs. 2C–D, S13) shows, however, that Denisovan admixture widely influenced the HLA system of Asians and Amerindians.

Of the two Denisovan HLA-A alleles (Fig. 2B), A*02 is widespread in modern humans, whereas A*11 is characteristically found in Asians (Fig. 2E), reaching 50–60% frequency in PNG and China, less common in Europe, and absent from Africa (fig. S14). This distribution coupled with the sharing of long HLA-A-C haplotypes between Denisovans and modern Asians, particularly Papuans (fig. S13), indicates that Denisovan admixture minimally contributed the A*11:01-C*12 or A*11:01-C*15 haplotype to modern Asians. A*11:01, which is carried by both these archaic haplotypes, is by far the most common A*11 allele (12). Because HLA alleles evolve subtype diversity rapidly (17, 18) it is highly improbable that A*11:01 was preserved independently in Denisovan and modern humans throughout >250k years (4), as would be required if the Out-of-Africa migration contributed any significant amount of A*11. The more parsimonious interpretation is that all modern A*11 is derived from Denisovan A*11, and that following introgression it increased in frequency to ~20%, becoming almost as common in Asia as A*02 at ~24% (11).

Denisovan HLA-C*15 and HLA-C*12:02 are also characteristic alleles of modern Asian populations (Figs. 2F–G, S14). At high frequency in PNG, their distribution in continental Asia extends further west than A*11 does, and in Africa their frequencies are low. C*12:02 and C*15 were formed before the Out-of-Africa migration (Figs. 2H, S15) and exhibit much higher haplotype diversity in Asia than in Africa (fig. S16), contrasting with the usually higher African genetic diversity (20). These properties fit with C*12:02 and C*15 having been introduced to modern humans through admixture with Denisovans in west Asia, with later spreading to Africa (21, 22) (Figs. 1F, S11 for C*15). Given our minimal sampling of the Denisovan population it is remarkable that C*15:05 and C*12:02 are the two modern HLA-C alleles in strongest LD with B*73 (Fig. 1E). Although B*73 was not carried by the Denisovan individual studied, the presence of these two associated HLA-C alleles provide strong circumstantial evidence that B*73 was passed from Denisovans to modern humans.

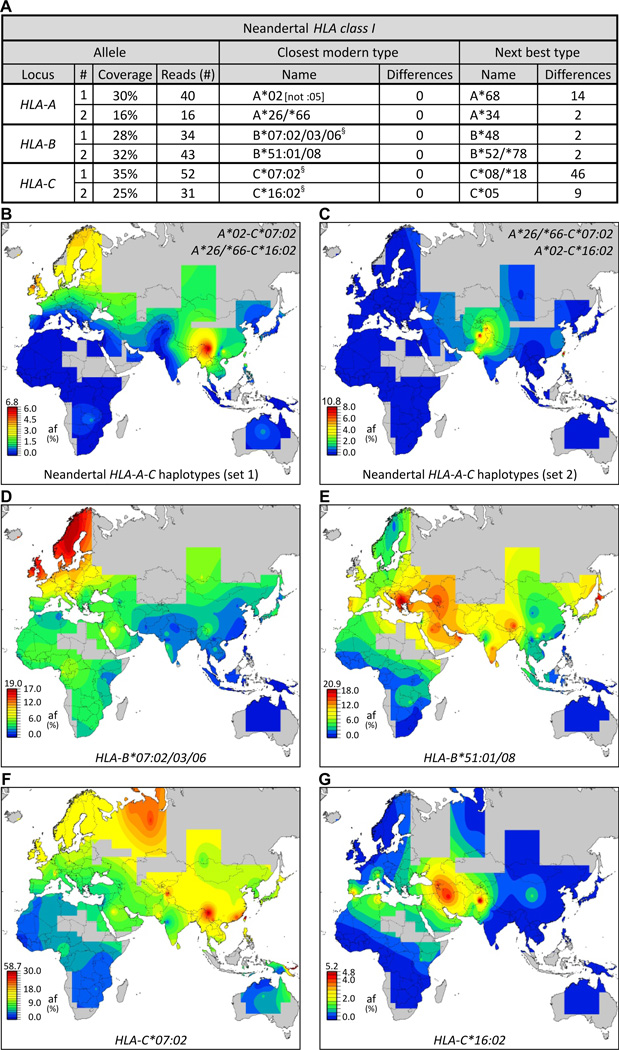

Genome-wide analysis showing three Vindija Neandertals exhibited limited genetic diversity (3) is reflected in our HLA analysis: each individual has the same HLA class I alleles (fig. S17). Because these HLA identities could not be the consequence of modern human DNA contamination of Neandertal samples, which is <1% (3), they indicate these individuals likely belonged to a small and isolated population (fig. S18). Clearly identified in each individual were HLA-A*02, C*07:02, and C*16; pooling the three sequence data sets allowed identification of HLA-B*07, -B*51 and either HLA-A*26 or its close relative A*66 as the other alleles (Fig. 3A). As done for the Denisovan, we examined all combinations of Neandertal HLA-A and HLA-C for their current distribution worldwide. All four combinations have highest frequencies in Eurasia and are absent in Africa (Figs. 3B–C, S19). Such conservation and distribution strongly support introgression of these haplotypes into modern humans by admixture with Neandertals in Eurasia. The Neandertal HLA-B and -C alleles were sufficiently resolved for us to study their distribution in modern human populations (fig. S20); their frequencies are high in Eurasia and low in Africa (Figs. 3D–G, S21). Our simulations of HLA introgression predicted the increased frequency and haplotype diversity in Eurasia that we observed (Figs. 1, S11) and was particularly strong for B*51 and C*07:02 (fig. S22), and presence of such alleles in Africa was due to back-migrations. Thus, Neandertal admixture contributed B*07, B*51, C*07:02, and C*16:02-bearing haplotypes to modern humans, and was likely the sole source of these allele groups. Unlike the distributions of Denisovan alleles, which center in Asia (Fig. 2E–G), Neandertal alleles display broader distributions peaking in different regions of Eurasia (Fig. 3D–G).

Fig.3.

Effect of adaptive introgression of Neandertal HLA class I alleles on modern human populations. (A) All six Neandertal HLA-A, -B and -C alleles are identical to modern HLA class I alleles. Shown at the left for each allele is the number of allele-specific sequence reads (3) and their coverage of the ~3.5kb HLA gene. Center columns give the modern-human allele (HLA type) having the lowest number of SNP differences from the Neandertal allele. The next most similar modern allele and the number of SNP differences are shown in the columns on the right. §, includes additional rare alleles. (B–C) Show the worldwide distributions of the two possible Neandertal HLA-A-C haplotype combinations. Both are present in modern Eurasians, but absent from Sub-Saharan Africans. (D–G) Distribution of four Neandertal alleles: HLA-B*07:02/03/06 (D), B*51:01/08 (E), C*07:02 (F), and C*16:02 (G), in modern human populations.

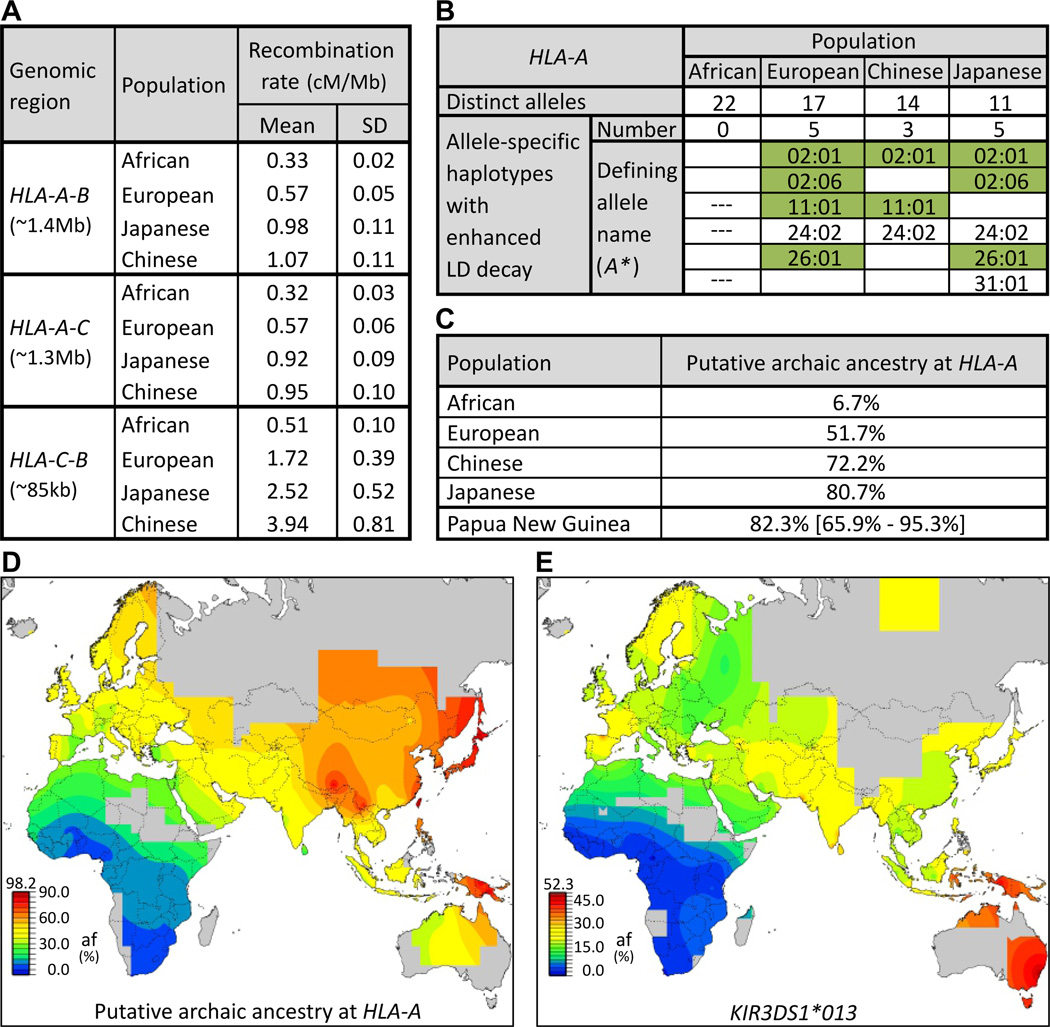

Modern populations with substantial levels of archaic ancestry are predicted to have decreased LD (23). From analysis of HapMap populations (20), we find that HLA class I recombination rates are greater in Europeans (1.7–2.5 fold) and Asians (2.9–7.7 fold) than in Africans, consistent with their higher frequencies of archaic HLA class I alleles (Fig. 4A). Enhanced LD decay correlates with presence of archaic alleles (Figs. 4B, S23), and the strongest correlation was with HLA-A, for which the six haplotypes exhibiting enhanced LD decay are restricted to non-Africans. These haplotypes include A*24:02 and A*31:01 along with the four archaic allele groups we characterized (A*11, A*26 and two A*02 groups). A*24:02 and A*31:01 are common in non-Africans and thus likely also introgressed from archaic to modern humans. From the combined frequencies of these six alleles, we estimate the putative archaic HLA-A ancestry to be >50% in Europe, >70% in Asia, and >95% in parts of PNG (Fig. 4C–D). These estimates for HLA class I are much higher than the genome-wide estimates of introgression (1–6%), showing how limited interbreeding with archaic humans has, in combination with natural selection, significantly shaped the HLA system in modern human populations outside of Africa. Our results demonstrate how highly polymorphic HLA genes can be sensitive probes of introgression, and we predict the same will apply to other polymorphic immune-system genes, for example the killer-cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIR) of NK cells. Present in the Denisovan genome (11), a candidate KIR for introgression is KIR3DS1*013 (Fig. 4E), rare in sub-Saharan Africans, but the most common KIR3DL1/S1 allele outside Africa (24).

Fig.4.

Linkage disequilibrium (LD) decay patterns of modern HLA haplotypes identify putative archaic HLA alleles. (A) HLA class I recombination rates in Eurasia exceed those observed in Africa. We focused on the three intergenic regions between HLA-A, -B, and -C (leftmost column) in the four HapMap populations (center column) (20). Recombination rates were corrected for effective population size (11). (B) Enhanced HLA class I LD decay significantly correlates with archaic ancestry (α=0.0042; (11)). Shown for each HapMap population are (top row) the number of distinct HLA-A alleles present and (second row) the number exhibiting enhanced LD decay (all allele-defining SNPs (r2>0.2) are within 500kb of HLA-A (31)). The allele names are listed (rows 3–8) and colored green when observed in archaic humans (Figs 2–3) or associated with archaic-origin haplotypes (fig. S25). HLA-B and -C are shown in fig. S23. --- absent in the population. (C) Predicted archaic ancestry at HLA-A (on the basis of the six alleles of panel (B)) for the four HapMap populations and six populations from PNG; for the latter mean and extreme values are given. (E–F) Worldwide distribution in modern human populations of putative archaic HLA-A alleles (E) and KIR3DS1*013, a putative archaic NK cell receptor (F).

On migrating Out-of-Africa modern humans encountered archaic humans, residents of Eurasia for more than 200ky and having immune systems better adapted to local pathogens (25). Such adaptations almost certainly involved changes in HLA class I, as exemplified by the modern human populations who first colonized the Americas (17, 18). For small migrating populations, admixture with archaic humans could restore HLA diversity following population bottleneck, and also provide a rapid way to acquire new, advantageous HLA variants already adapted to local pathogens. For example, HLA-A*11, an abundant archaic allotype in modern Asian populations, provides T cell-mediated protection against some strains of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) (26) and in combination with a peptide derived from EBV is one of only two HLA ligands for the KIR3DL2 NK cell receptor (27). HLA*A11 is also the strongest ligand for KIR2DS4 (28). Other prominent introgressed HLA class I are good KIR ligands. HLA-B*73 is one of only two HLA-B allotypes carrying the C1 epitope, the ligand for KIR2DL3 (29). Prominent in Amerindians, C*07:02 is a strong C1 ligand for KIR2DL2/3 and both B*51 and A*24 are strong Bw4 ligands for KIR3DL1 (30). Such properties suggest that adaptive introgression of these HLA alleles was driven by their role in controlling NK cells, lymphocytes essential for immune defense and reproduction (6). Conversely, adaptive introgression of HLA-A*26, -A*31, and -B*07, which are not KIR ligands, was likely driven by their role in T cell immunity. Adaptive introgression provides a mechanism for rapid evolution, a signature property of the extraordinarily plastic interactions between MHC class I ligands and lymphocyte receptors (6).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank individual investigators and the Bone Marrow Donors Worldwide (BMDW) organization for kindly providing HLA class I typing data, as well as bone marrow registries from Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Cyprus, Czech Republic, France, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Lithuania, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Singapore, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, UK and USA for contributing typing data through BMDW. We thank E. Watkin for technical support. We are indebted to the large genome sequencing centers for early access to the gorilla genome data. We used sequence reads generated at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute as part of the gorilla reference genome sequencing project. These data can be obtained from the NCBI Trace Archive (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/). We also used reads generated by Washington University School of Medicine; these data were produced by the Genome Institute at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and can be obtained from the NCBI Trace Archive (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/). Funded by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant AI031168, Yerkes Center base grant RR000165, National Science Foundation awards (CNS-0619926, TG-DBS100006), by federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, NIH (contract HHSN261200800001E), and by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Sequence data have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers JF974053-70.

References and Notes

- 1.Gibbons A. Science. 2011;331:392. doi: 10.1126/science.331.6016.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yotova V, et al. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:1957. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green RE, et al. Science. 2010;328:710. doi: 10.1126/science.1188021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reich D, et al. Nature. 2010;468:1053. doi: 10.1038/nature09710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castric V, Bechsgaard J, Schierup MH, Vekemans X. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000168. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parham P. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005;5:201. doi: 10.1038/nri1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao K, et al. Hum Immunol. 2001;62:1009. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(01)00298-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parham P, et al. Tissue Antigens. 1994;43:302. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1994.tb02344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vilches C, de Pablo R, Herrero MJ, Moreno ME, Kreisler M. Immunogenetics. 1994;40:166. doi: 10.1007/BF00188185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robinson J, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D1171. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Materials and methods are available as Supporting Online Material.

- 12.Gonzalez-Galarza FF, Christmas S, Middleton D, Jones AR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D913. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vilches C, de Pablo R, Herrero MJ, Moreno ME, Kreisler M. Immunogenetics. 1994;40:313. doi: 10.1007/BF00189983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Behar DM, et al. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:1130. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Semino O, Santachiara-Benerecetti AS, Falaschi F, Cavalli-Sforza LL, Underhill PA. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:265. doi: 10.1086/338306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jobin MJ, Mountain JL. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2936. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Belich MP, et al. Nature. 1992;357:326. doi: 10.1038/357326a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watkins DI, et al. Nature. 1992;357:329. doi: 10.1038/357329a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petzl-Erler ML, Luz R, Sotomaior VS. Tissue Antigens. 1993;41:227. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1993.tb02011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nature; The International HapMap Consortium; 2005. p. 1299. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cruciani F, et al. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:1197. doi: 10.1086/340257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moodley Y, et al. Science. 2009;323:527. doi: 10.1126/science.1166083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeGiorgio M, Jakobsson M, Rosenberg NA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16057. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903341106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norman PJ, et al. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1092. doi: 10.1038/ng2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferrer-Admetlla A, et al. J Immunol. 2008;181:1315. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.2.1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Campos-Lima PO, et al. Science. 1993;260:98. doi: 10.1126/science.7682013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hansasuta P, et al. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:1673. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graef T, et al. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2557. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moesta AK, et al. J Immunol. 2008;180:3969. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.3969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yawata M, et al. Blood. 2008;112:2369. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-143727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Bakker PI, et al. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1166. doi: 10.1038/ng1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.