Abstract

The purpose of this randomized pilot study is to conduct an intervention with 68 rural women living with AIDS to compare the effectiveness of two different programs on depressive symptoms. The trial was designed to assess the impact of the Asha-Life intervention, engaging an HIV-trained village woman, Asha (Accredited Social Health Activist), to participate in the care of WLA, along with other health care providers compared to a Usual Care group. Two high prevalence HIV/AIDS villages in rural Andhra Pradesh, which were demographically alike and served by distinct Public Health Centers, were selected randomly from a total of 16 villages. The findings of this study demonstrated that the Asha-Life participants significantly reduced their depressive symptom scores compared to the Usual Care participants. Moreover, women living with AIDS who demonstrated higher depressive symptom scores at baseline had greater reduction in their depressive symptoms than women with lower scores.

Keywords: AIDS, depressive symptoms, rural India, women

India remains severely impacted by the HIV/AIDS pandemic (National AIDS Control Organization [NACO], 2008; Pandey et al., 2009; Ramchandani et al., 2007). The epidemic there is shifting from urban cities to rural villages; in particular, rural Andhra Pradesh (AP), a primarily rice-producing district, is one of four states with the highest burden of cases (Pandey et al., 2009). The prevalence of HIV in AP is 1.05 which is markedly higher than that of the nation of India as a whole (0.36%) (Pandey et al., 2009). As of 2006, there were approximately 525,560 people living with HIV in AP (Pandey et al., 2009).

Women in urban South India were found to have higher rates of depression when compared to men (16% vs. 14%, p< .001) (Poongothai, Pradeepa, Ganesan, & Mohan, 2009). There were several factors which influenced depression, singularly, having low socioeconomic status, being a woman, being divorced or widowed (p<.001) (Poongothai et al., 2009). In rural Punjab, the data suggests that approximately 66% of women had depression compared to 25% of men and this phenomena increased with age (Mumford, Saeed, Ahmad, Latif, & Mubbashar, 1997).

People living with HIV/AIDS are at an increased risk for depression, as well as substance abuse (Carey, Ravi, Chandra, Desai, & Neal, 2007; Chandra, Desai, & Ranjan, 2005). Research focused on strategies to reduce depression among HIV/AIDS patients is critical because the data suggest that depression independently predicts lower adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) (Chandra, Ravi, Desai, & Subbakrishna, 1998; Gordillo, del Amo, Soriana, & Gonzalez-Lahor, 1999; Kumarasamy et al., 2005) and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality (Farinpour et al., 2003; Ickovics, Cameron, Zackin, Bassett, & Chesney, 2000).

To date, the majority of studies in India focus on describing the HIV/AIDS epidemic in urban settings. However, in comparable rural regions like Hunan, China, interventions such as nurse home visits and telephone calls have improved depressive symptoms of HIV-infected heroin users (Wang et al., 2010). Specifically, when compared to the control group, participants in the experimental group were more likely to adhere to medications (p < 0.001) and the data suggests that there were improvements in quality of life. Similarly, among HIV-infected persons in the rural United States, improvements in depression were found among those exposed to a telephone-delivered therapy (Ransom et al., 2008).

The purpose of this paper is to assess the impact of an ART adherence study on the reduction of depressive symptoms among rural women living with AIDS (WLA) in AP.

Methods

Design

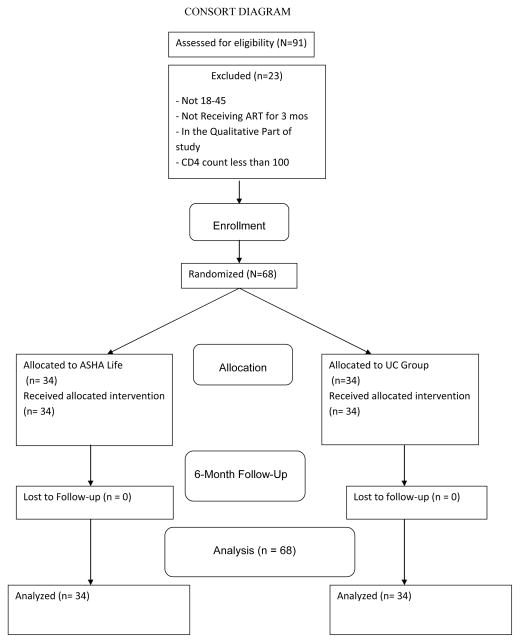

A total of 68 rural WLA participated in a prospective, randomized clinical trial designed to determine the impact of having a HIV-trained village woman, Asha (Accredited Social Health Activist), participate in their care, along with other health care providers, compared to a usual care (UC) group (See Figure 1). Human Subjects Protection Committee clearances were obtained both in the US and in India.

Figure 1.

Sample and Setting

Inclusion criteria for the study were: (1) WLA between the ages of 18–45; (2) screened as receiving ART for a minimum of three months; and (3) not a participant of an earlier qualitative study. An exclusionary factor was CD4 cell count less than 100. Two high prevalence HIV/AIDS villages in rural AP that were demographically alike and served by distinct Public Health Centers (PHCs) were selected randomly from a total of 16 villages. Between these two, one was randomly selected to engage the intervention group, while the second engaged the UC group.

Comprehensive Health Seeking and Coping Model

The comprehensive health seeking and coping paradigm (CHSCP; Nyamathi, 1989) served as the theoretical framework for the intervention study. This framework originated from the Lazarus and Folkman (1984) stress and coping model and the Schlotfeldt (1981) Health Seeking Paradigm, and has been applied to investigations focusing on understanding HIV, Hepatitis and TB risk and protective behaviors and health outcomes (Nyamathi et al., 2002; Nyamathi, Berg, Jones, & Leake, 2005; Nyamathi, Christiani, Nahid, Gregerson, & Leake, 2006) among homeless, and impoverished women and men. Identifying correlates of decrease in depressive symptoms will provide valuable information to those engaged in disease prevention and intervention efforts.

The CHSCP is composed of a number of antecedent, mediating, and dependent variables. The antecedent variables include socio-demographic factors and health history, which includes health care access and utilization. Specifically, for WLA, these antecedent variables were focused on education, religion, and being widowed, all of which may impact depressive symptoms as well as intervention-based improvement. Mediating components include social, cognitive, behavioral and treatment factors, including ART side effects and satisfaction with the Asha. Change in depressive symptoms is the primary dependent variable to be measured at the six-month follow-up period for the present paper.

Preparing Asha and Finalizing the Intervention

The research team was composed of two US investigators and two Indian investigators; the latter of which included a medical doctor and social scientist. Formative research was conducted to lay the groundwork for the intervention study and assess the needs and strategies of the intervention implementation from the perspective of the WLA, HIV rural physicians, nurses and reproductive health-focused Asha (Nyamathi et al., 2010; 2011). Based upon these findings, the research protocol and an operational manual were finalized and training of nurses, physicians and Ashas was undertaken by the study investigators and project director (PD)/research officer (RO).

Nurses and physicians in both PHCs received updated information about HIV and AIDS and the progression of HIV/AIDS, as well as updates on ART medication protocol, dosage and side effects of ART. Moreover, information about the study and the role of the health care providers in delivering symptomatic care for the participants when they were ill was presented. This training lasted one day. In addition, our research physician, who was located in a nearby non-study site, examined the WLA monthly to capture health assessments, such as weight, and blood pressure, and assessed for ART side effects. Referrals to medical and psychiatric healthcare providers were provided as necessary.

Lay village women who were trained as Asha in the intervention group were selected by the PD/RO among women who responded to the advertisement for this position. Training an Asha for village communities has become an important health strategy taken on by the Government of India under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW, 2005). Accreditation is bestowed based on detailed guidelines on selection and training of Asha. In our study, these women were selected if they were educated beyond high school, were interested in caring for WLA, and lived in the same village as the respective women who participated. Once selected, these intervention Ashas (n = 4) were trained by the PD/RO, physician and social scientist investigators, and the local research physician over a three-day period.

The content provided included: (1) review of the study and manual forms; (2) understanding of needs of WLA discovered in formative research; (3) basics of HIV/AIDS and progression; (4) importance of adherence to ART; (5) coping strategies for dealing with distress brought on by HIV/AIDS; (6) importance of nutrition in improving the lives of WLA and their families; (7) life skills options and how to integrate them into the lives of WLA; and (8) understanding the role of the Asha in implementing the intervention study. In addition to the didactic sessions, Asha were observed within trainer-conducted mock intervention sessions. Clinical supervision was ongoing. The primary role of the intervention Ashas was to visit 4–5 WLA weekly, monitor barriers to ART adherence, and provide assistance that was responsive to removing any barriers the WLA faced in accessing health care or the prescribed treatment (obtaining monthly ART from the District Hospital), etc. In addition, the Asha were trained to observe for side effects, provide basic education and counseling, promote healthy life style choices, and link WLA with community resources to match health needs.

A similar selection process for selection was undertaken for two control Asha. Their separate training content included: (1) Review of the study and manual forms; (2) understanding of needs of WLA discovered in formative research; (3) basics of HIV/AIDS and progression; (4) importance of adherence to ART; and (5) understanding the role of the Asha in implementing the standard study. These Asha were also observed within trainer-conducted mock intervention sessions. Clinical supervision was ongoing. The role of UC Asha was to visit 8–9 WLA monthly, monitor and record ART adherence, and keep monthly records on ART adherence, and the nature and outcome of the WLAs’ hospital and clinic visits.

Enrolling Participants

The study was announced in each PHC by means of flyers posted in the large waiting area where patients collected. WLA who frequented the PHC and were interested in receiving further information about the study contacted the PD by use of the phone number on the flyer or they were able to meet her in person, as she was based at the PHC in a private area. After a description was provided, and all questions were answered, interested WLA signed the first of three informed consents, all of which were translated into Telegu the local language. The PD then administered a brief two-minute structured questionnaire that inquired about age, education and other socio-demographic characteristics, including HIV and ART status; all of these questions determined eligibility for the study and provided basic sociodemographic information on those who refused.

If eligibility was met, the PD discussed the need for CD4 testing and a second informed consent was signed, followed by a venipuncture in the PHC. Within four days, the WLA met with the PD to discuss the test results, and if the CD4 level was not less than 100, the final informed consent was signed and the baseline survey was administered. WLA were then ready for the intervention to begin. All respondents were paid $5 for completing the screening procedures; $10 for returning for test results and completing the baseline questionnaire (same day), $5 for each of six program-specific sessions and $20 upon completion of the six-month questionnaire.

Asha-Life (AL) Intervention

In addition to the Asha intervention, AL participants received six program-specific sessions in sequence, after an initial need assessment was conducted by the PD. The sessions included the following topics: (1) HIV/AIDS and dealing with the illness; (2) learning about ART and ways to overcome barriers; (3) parenting and maintaining a healthy home environment; (4) how to improve coping, including religion, reduce stigma and care for family members; (5) basics of good nutrition and easy cooking tips; and (6) engagement in life skills classes, such as working with computers, marketing, and embroidery. In addition, the WLA received monthly supplies of protein supplementation in the form of 1 kg of Urad dal [Black Gram] and 1 kg of Toor dal).

Usual Care Program

The Usual Care (UC) WLA received sessions matched in terms of number and length of time to the Asha-Life program. The UC sessions generally included the following topics: (1) HIV/AIDS and dealing with the illness; (2) learning about ART and ways to overcome barriers; and (3) positive parenting. In addition, the WLA received monthly supplies of yellow split chick peas (chana dahl).

Instruments

Several of the instruments have been previously tested with WLA in the U.S. (Rotheram-Borus, 2000, Rotheram-Borus, Stein, & Lin, 2001; Whitbeck, Hoyt, & Bao, 2000) and in India (Ekstrand, Chandy, Gandhi, Stewart, & Singh, 2006).

Socio-Demographic information

A structured questionnaire was used to collect information about age, gender, birthday, education, employment status, relationship status and number of children.

Health History

We collected self-reported information on HIV-related physical symptoms, treatment history, adherence history including treatment interruption, and barriers and facilitators to adherence. We also assessed treatment and health care access and utilization.

CD4 Count

CD4 counts were assessed during screening. Blood samples were sent to the designated lab for CD4 determination by flow cytometry. The absolute numbers of CD4 cells were obtained by multiplying % CD4 from flow cytometry by total white blood cell count (determined by Act Diff Coulter).

Knowledge about HIV

This was measured by a modified 21-item Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Knowledge questionnaire for HIV/AIDS (National Center for Health Statistics [NCHS], 1989). Modifications to the CDC instrument have been detailed elsewhere (Leake, Nyamathi, & Gelberg, 1997). The internal consistency of the overall scale in a sample of Indian homeopathy physicians was .81 (Nyamathi et al., 2011). In the present study, the internal consistency was .91.

MD Communication and Clinical Appointments

An 11-item scale in which the first 7 items assessed the degree to which WLA were comfortable in communicating with their HIV physician, the extent to which they perceived him/her to be knowledgeable, and the extent to which the physician provided assistance. The responses were measured on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (every time). Example items included “Do you ask questions about your medical condition”, “Do you feel your doctor is knowledgeable about your medical condition?, and ‘Do you get help from your doctor in solving any problems in taking your HIV medication?”. In addition, four additional items inquired about potential barriers to attending the clinic or seeing the doctor by asking how often they were able to “get transportation to the clinic”, “find someone to watch your children while you’re gone”, “get time off from work or duties” and “have to wait for a long time in the clinic waiting area”, using the same 4-point scale. Cronbach’s alpha for the scale in this sample was .90. The average score of these 11-items was used in the analysis.

Stigma

Stigma scales developed by Ekstrand et al. (2011) and Steward et al. (2008) provided an Experienced or Enacted Stigma scale with a reliability of .90.

Avoidant Coping Strategies

The scale items were based on previous research (Berg & Arnsten, 2001; Chesney, 2006; Simoni et al., 2006) and were subsequently modified based on our qualitative interviews. A sample item from this scale is: “How often have you described your illness as tuberculosis instead of HIV?”

Depressive Symptomatology

The center for epidemiologic studies (CES-D) is a 20-item scale that measures frequency of depressive symptoms on a 4-point continuum. The CES-D has well-established reliability and validity. Scores on the CES-D range from 0–60, with higher scores representing greater depressive symptomatology. Internal consistency for this scale in our Indian population was .91.

Data Analysis

Initial analyses examined whether the two programs were comparable on important baseline variables; these analyses included chi-square tests for categorical variables and two-sample t or Wilcoxon tests for continuous variables, depending on the underlying distributions. Change in depressive symptoms between baseline and six months was then examined for the programs and for variables that differed between the two programs using t-tests and correlations. Linear regression modeling assessed whether there was an important program effect on change in depressive symptoms after controlling for potential confounders that differed between programs at baseline at the p < .10 level and were also related to change in depressive symptoms. Because a substantial reduction in depressive symptoms was observed only in the AL group, we also looked at correlates of change in symptoms in this group to assist in understanding the effect of the intervention and whether there were differential impacts on members of particular subgroups. In addition to the variables in Table 1, we also examined whether patients had seen a psychiatrist, received anti-depressant medication and undergone cognitive behavior therapy; these aspects of treatment applied exclusively or primarily to participants of the AL program.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics by Program and Overall

| Baseline Variable | AL | UC | Total % | p valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |||

| Any children | 32 | 94.1 | 27 | 79.4 | 86.8 | .074 |

| Married | 15 | 44.1 | 20 | 58.8 | 51.5 | .225 |

| Live with spouse | 13 | 38.2 | 17 | 50.0 | 44.1 | .329 |

| At least 4 years of school | 11 | 32.4 | 4 | 11.8 | 22.1 | .041 |

| Hindu religion | 15 | 45.5 | 29 | 85.3 | 65.7 | .001 |

| More than 47 Months since HIV Diagnosis | 22 | 66.7 | 11 | 32.4 | 65.7 | .005 |

| More than 18 Months on Medication | 18 | 52.9 | 15 | 45.5 | 49.3 | .540 |

| Baseline CD4b count > 363.5 | 17 | 50.0 | 17 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 1.00 |

| Any Medication-taking Strategy | 19 | 55.9 | 15 | 44.1 | 50.0 | .332 |

| Any Help Getting Medication | 16 | 47.1 | 9 | 26.5 | 36.8 | .078 |

| Any Perceived ART Benefit | 20 | 58.8 | 27 | 79.4 | 69.1 | .066 |

| Depressed Mood | 24 | 70.6 | 13 | 38.2 | 54.4 | .007 |

| Any Barrier to Medication Adherence | 13 | 38.2 | 19 | 55.9 | 47.1 | .145 |

| Any Adherence Support | 19 | 55.9 | 18 | 52.9 | 54.4 | .808 |

| M | SD | M | SD | M | p valuea | |

| Age (20–45) | 32.3 | 5.3 | 30.1 | 5.2 | 31.2 | .102 |

| Stigma Experienced (0–10) | 6.4 | 3.6 | 7.9 | 2.5 | 7.1 | .056 |

| Compliance with ART (29–100) | 43.3 | 10.5 | 59.4 | 18.0 | 46.3 | .001 |

| Number of HIV Symptoms (2–18) | 10.4 | 3.2 | 11.1 | 3.9 | 10.8 | .457 |

| Visits Past 3 Months (2–15) | 7.7 | 3.5 | 7.4 | 3.6 | 7.5 | .732 |

| MD Communication & Clinic Appointments (0.4 – 3.0) | 1.7 | 0.6 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 1.7 | .846 |

| Avoidance Coping (1–4) | 3.2 | 0.7 | 3.3 | 0.8 | 3.2 | .526 |

Chi-square or t test for program differences;

Range of baseline CD4 count was 127 to 1071

Results

Sociodemographic and Health Characteristics at Baseline

A total of 68 rural WLA were enrolled, 34 in the AL intervention and 34 in the UC group. All 68 women completed the six-month follow-up. Participants were 20 to 45 years of age (mean = 31.2 years, SD = 5.3), primarily Hindu (66%), married (52%) or widowed (41%) (data not tabled) and for the most part lived with children (77%). About one in five (22%) had received at least four years of education (Table 1).

In terms of health demographics, nearly two-thirds of the women had been diagnosed with HIV for approximately four or more years and almost half had been taking ART for a little over 1.5 years. The mean number of visits to a healthcare provider in the past three months was 7.5 (SD 3.6). A mean of 10.8 HIV symptoms was reported. The mean compliance with ART at baseline was 46.3 (SD 14.3). Over two-thirds of the sample (69%) reported benefits to taking ART, but half (47%) experienced at least one barrier to ART adherence. Support for adherence by family and friends was reported by slightly over half (54%), and about one-third (37%) reported receiving help from family and friends in getting medication. In addition, over half (54%) of the women reported depressed mood (CES-D ≥ 16) and half reported using whatever strategy they could to adhere to the ART regimen.

Associations with Program

In bivariate analysis, education, being Hindu, duration of HIV, depression and compliance with ART differed between programs (Table 1). In particular, the AL intervention group was more likely to have at least four years of education, to have lived more than about four years with HIV, and to be depressed. In contrast, AL participants were less likely to be Hindu and their compliance with ART at baseline was lower than that of the UC group. Age, marital status and living with spouse or children were not found to be significantly associated with program.

There were trends for the AL intervention group to receive more help from family and friends in getting medication and to be more likely to have children compared to the UC group. There was also a trend for the UC group to be more likely to see some benefit from ART at baseline. CD4 count at baseline, duration of ART, having barriers to ART adherence, number of health care visits, number of HIV symptoms, MD communication and clinical appointment keeping, and having utilized any strategy to take ART were not associated with program.

Table 2 shows the change in depressive symptoms for each program and for each level of variables that differed between programs at the p < .10 level at baseline. For the AL program, depressive symptoms decreased almost 17 points (from 20.0 at baseline to 3.2 at six months) while depressive symptoms increased for the UC group (from 15.4 at baseline to 26 at six months). Similar, but less marked, differences were found for having received a HIV diagnosis more than 47 months ago, receiving help getting medication and depression. Better educated and non-Hindu participants also had substantial reductions in depressive symptoms, while those who were Hindu and less educated had less than a one-point change in depressive symptoms.

Table 2.

Associations of Selected Variables with Changea in Depressive Symptoms

| Baseline Variable | Depressive Symptom Change | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | |

| Program | ||

| AL | 16.85 | 9.6*** |

| UC | −10.56 | 12.7 |

| Children | ||

| Yes | 3.38 | 18.1 |

| No | 0.12 | 16.0 |

| ≥ 4 years of School | ||

| Yes | 12.05 | 15.1* |

| No | 0.31 | 17.7 |

| Hindu Religion | ||

| Yes | −0.80 | 19.6** |

| No | 9.68 | 10.8 |

| More than 47 Months Since HIV Diagnosis | ||

| Yes | 8.96 | 17.4** |

| No | −3.57 | 16.1 |

| Help Getting Medication | ||

| Yes | 10.28 | 16.0** |

| No | −1.43 | 17.5 |

| Any Perceived ART Benefit | ||

| Yes | 2.32 | 17.4 |

| No | 4.40 | 19.0 |

| Depressedb | ||

| Yes | 8.76 | 19.6** |

| No | −3.81 | 12.6 |

| Barrier to Medication Adherence | ||

| Yes | 0.84 | 19.9 |

| No | 4.75 | 15.8 |

| Experienced Stigma ≥ 8.5c | ||

| Yes | 2.62 | 16.8 |

| No | 3.27 | 19.0 |

Change from baseline to six months;

CES-D ≥ 16;

Range 0 to 10

p < .05, t test for difference in change score

p < .01, t test for difference in change score

p < .001, t test for difference in change score

Multivariate Results

Adjusting for potentially confounding characteristics, the AL participants had much greater reduction in depressive symptom scores than those in the UC group (Table 3). Those with higher depressive symptom scores at baseline also showed greater reduction in symptoms than those with lower baseline depressive symptom scores. Education, having help with medication from friends and family, Hindu religion and having received an HIV diagnosis more than 47 months previously were not related to change in depressive symptoms.

Table 3.

Linear Regression Results for Change* in Depressive Symptoms (N=66)

| Variables | β | s.e. | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asha Life Intervention (vs Control) | 22.89 | 3.2 | .001 |

| Baseline Depressive Symptoms | 0.54 | 0.2 | .001 |

| ≥ 4 years of School | 1.94 | 3.2 | .549 |

| Help Getting Medication | 3.64 | 2.8 | .869 |

| Hindu Religion | 0.16 | 3.0 | .958 |

| More than 47 Months Since HIV Diagnosis | 2.12 | 2.8 | .456 |

Baseline score minus month six score

Correlates of Change in the AL Group

For the AL participants, Pearson and Spearman correlations between change in depressive symptom scores and the variables in Table 1, along with having seen a psychiatrist and having received anti-depressants and cognitive behavioral therapy, indicated that depressive symptoms at baseline were the primary correlate of change (Pearson r = .93). Being Hindu, number of HIV symptoms at baseline and HIV/AIDS knowledge were also correlated with change in depressive symptoms. However, when a series of linear regressions were performed on change in symptoms using each of these variables as a predictor, along with baseline depressive symptoms, only number of HIV symptoms was related to depressive symptom change.

Discussion

The findings of our study highlight a poorly understood topic in India, namely, depressive symptoms among rural WLA. This prospective, randomized study demonstrated that participants in the AL intervention were able to reduce depressive symptom scores to a substantial degree while depressive symptom scores in the UC group increased during the study period. Moreover, women with higher depressive symptom scores at baseline in both groups experienced a greater reduction in depressive symptoms than did those with lower scores. The findings of our study are unique in that no other clinical trials have tested the impact of a comprehensive Asha-delivered intervention compared with a UC approach.

Since our AL intervention was delivered as a comprehensive package, the major impact that the Asha intervention had on reducing depressive symptoms must be considered in relation to all the components of the program. These components included the supportive role of the Ashas in both assisting and accompanying WLA to pick up their ART medications and helping them to access health care when they were physically ill and/or having mental health issues. In addition, the AL group of WLA received a substantial amount of didactic content delivered in group sessions. These sessions focused on understanding HIV and AIDS, the importance of taking ART regularly, ways to improve coping, including looking to spirituality for support, reducing stigma, dealing with sadness, keeping a clean home, understanding the basics of good nutrition, and engagement in Life Skills classes. The multidimensional nature of the AL program may explain why it succeeded in reducing depressive symptoms to a substantial degree among a variety of WLA, including younger and older women, those with more and less education, and those living with and without spouses.

We believe the most important aspect of our AL intervention was that the Asha physically and emotionally supported the WLA and enabled them to maintain ART in a systematic manner. While there are no other clinical trials of Asha intervention, other studies have found a strong association between adherence to ART and depression (Sarna et al., 2008). In fact, depression is one of the major barriers related to non-compliance to ART (Sarna et al., 2008; Safren et al., 2005). Among HIV- positive persons in urban Pune and New Delhi, India, severe depression was associated with lower adherence rates to ART (Sarna et al., 2008). Further, Nyamathi and colleagues (2011) found that barriers to ART adherence for persons with AIDS included physical illness, poor psychological health, stigma, and social barriers. Other studies have shown that measures of poor psychological health, including depression, act as barriers to seeking and adhering to treatment for people living with HIV/AIDS (PLHA) (Nyamathi, Thomas, Greengold, & Swaminthan, 2009; Thomas, Nyamathi, & Swaminathan, 2009).

Provision of social support may also have played an important role. Other researchers have found that familial and social support impact depression and ART adherence (Majumdar, 2004; Nyamathi et al., 2011). Many women in the UC program may have experienced social and physical isolation due to their AIDS status and, without a supportive Asha, this isolation may have led to loneliness and worsening mental and emotional health (Majumdar, 2004). In India, another group, which may be both socially and economically disadvantaged, are widows. Marriage is perceived as a major accomplishment for women. Widowed WLA may be stigmatized due to the illness. This can lead to loneliness, social isolation, and discrimination (Pradhan, Sundar, & Singh, 2006). The fact that women may be perceived as vectors of transmission of the HIV virus by their families, despite knowledge that their husbands frequented female sex workers, further catalyze these issues (Jain, 2006). These factors subsequently impact psychosocial health (Kermode et al., 2008) and may lead to a poorer quality of life.

We believe the integration of spirituality in our AL intervention was another important factor in its success. While no related studies have been conducted in India, Kudel et al. (2011) found that spirituality and religiosity influenced social support which in turn had a positive effect on depressed mood (Kudel et al., 2011). Furthermore, there are no studies which document the role of Hinduism on barriers or facilitators of ART adherence, stigma, discrimination, or communicating with health care providers.

The support of the Asha staff in bringing the AL women to the study psychologist may also have been important. While we were unable to isolate the effects of which component was the most critical, our findings are unique because no other studies inform us about the impact of having a psychologist in India. However, Ransom and colleagues (2008) conducted a pilot trial of a telephone-delivered, interpersonal psychotherapy intervention with 79 HIV-positive rural participants with depression in the United States. Compared to the UC group (n = 38) who received access to support groups and individual therapy, the teletherapy group (n=41) received six 50 minute sessions on topics such as conflicts with partners, role transition, grief and interpersonal sensitivity (Ransom et al., 2008). The findings revealed that the teletherapy group had significant improvements in depressive and psychiatric symptoms (Ransom et al., 2008). A study of mobile phone access to HIV positive patients (n=322) in southern India, were one third of the patients lived in rural areas, revealed perceived benefits to maintaining adherence (Shet & de Costa, 2011). These authors contend that utilization of mobile-based technology is promising in terms of connecting patients with providers, obtaining patient data, and training rural health care professionals. While, ten percent of participants indicated that they were concerned about privacy, indicating future research is needed to deal with privacy issues and perfect its far-reaching benefits.

Another aspect of the Asha’s care was to address any factors that might have impacted psychological distress. One content area discussed in group classes, and for which Ashas were specifically prepared, was ways that stigma could be curtailed. Kumarasamy and colleagues (2005) found that persons living with HIV and AIDS experienced difficulty in disclosing HIV-positive status to family and social networks due to fear of stigmatization. This, in fact, serves as a significant barrier to seeking care, taking pills in public and accessing potential social support (Kumarasamy et al., 2005). Since the UC group did not have the benefit of Ashas who were trained to help them deal with stigma from the community and from healthcare personnel when they needed treatment and medication from their deteriorating clinical condition, it is not surprising that their depressive symptom scores increased.

Limitations

Limitations to this paper include a small sample size from two rural villages in south India. Yet, the results of this study may still be applicable to a large number of rural WLA who live in villages since AP is a large rural state in India with a significant population of HIV-infected women. Thus, a significant proportion of WLA in India reside in this area.

Conclusion

The overall findings of our study are significant with respect to depressive symptoms, provide a basis for addressing the challenges that confront rural WLA and support the AL intervention, which focuses on education of WLA, support, and nutrition. However, additional research needs to tease out the components of the intervention to determine the impact of specific components. Nevertheless, as a package, the AL intervention did markedly decrease depressive symptom scores in WLA in rural India.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute on Mental Health, Grant #MH082662

Contributor Information

Adeline Nyamathi, University of California, Los Angeles, School of Nursing.

Benissa E. Salem, University of California, Los Angeles, School of Nursing.

Visha Meyer, Cornell University.

Kalyan K Ganguly, Indian Council for Medical Research.

Sanjeev Sinha, All India Institute for Medical Sciences.

Padma Ramakrishnan, People’s Health Society, Nellore, India.

References

- Berg KM, Arnsten JH. Practical and conceptual challenges in measuring antiretroviral adherence. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2006;43(Suppl 1):S79–87. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000248337.97814.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, Ravi V, Chandra PS, Desai A, Neal DJ. Prevalence of HIV, Hepatitis B, syphilis, and chlamydia among adults seeking treatment for a mental disorder in southern India. AIDS & Behavior. 2007;11(2):289–297. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9134-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra PS, Ravi V, Desai A, Subbakrishna DK. Anxiety and depression among HIV-infected heterosexuals--a report from India. Journal of Psychosomatic Ressearch. 1998;45(5):401–409. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(98)00028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra PS, Desai G, Ranjan S. HIV & psychiatric disorders. Indian Journal of Medical Research. 2005;121(4):451–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney MA. The Elusive gold standard: Future perspectives for HIV adherence assessment and intervention. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2006;43(Suppl 1):S149–55. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000243112.91293.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrand ML, Bharat S, Ramakrishna J, Heylen E. Blame, symbolic stigma and HIV misconceptions are associated with support for coercive measures in Urban India. AIDS & Behavior. 2011;16(3):700–710. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9888-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrand ML, Chandy S, Gandhi M, Stewart W, Singh G. “Sometimes just run out”: Delays in prescription refills as a risk for the development of HIV drug resistance in India. Presented at the XVI International Conference on AIDS; Toronto, Canada.. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Farinpour R, Miller EN, Satz P, Selnes OA, Cohen BA, Becker JT, Skolasky RL, Jr, Visscher BR. Psychosocial risk factors of HIV morbidity and mortality: findings from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS) Journal of Clinical & Experimental Neuropsychology. 2003;25(5):654–670. doi: 10.1076/jcen.25.5.654.14577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordillo V, del Amo J, Soriano V, González-Lahoz J. Sociodemographic and psychological variables influencing adherence to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 1999;13(13):1763–1769. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199909100-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ickovics JA, Cameron R, Zackin R, Bassett M, Chesney M. Adherence within ACTG 370: Rates, Clinical Outcomes and Predictors. AACTG Annual Meeting; Alexandria, VA.. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jain D. Women, property rights and HIV in India. 2006 Retrieved January 1, 2012 from http://www.landcoalition.org/global_initiatives/womens_land_rights/jain_women_property_rights_and_hiv_india.

- Kermode M, Devine A, Chandra P, Dzuvichu B, Gilbert T, Herman H. Some peace of mind: Assessing a pilot intervention to promote mental health among widows of injecting drug users in north-east India. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:294. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudel I, Cotton S, Szaflarski M, Holmes WC, Tsevat J. Spirituality and religiosity in patients with HIV: A test and expansion of a model. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2011;41(1):92–103. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9229-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumarasamy N, Safren SA, Raminani SR, Pickard R, James R, Krishnan AK, Mayer KH. Barriers and facilitators to antiretroviral medication adherence among patients with HIV in Chennai, India: A qualitative study. AIDS Patient Care & STDS. 2005;19(8):526–537. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal and Coping. New York: Springer; 1984. pp. 117–180. [Google Scholar]

- Leake B, Nyamathi A, Gelberg L. Reliability, validity and composition of a Subset of the CDC AIDS knowledge questionnaire in a sample of homeless and impoverished adults. Medical Care. 1997;35:747–755. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199708000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar B. An exploration of socioeconomic, spiritual, and family support among HIV-positive women in India. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2004;15(3):37–46. doi: 10.1177/1055329003261967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) ASHA. Government of India; 2005. Retrieved July 20, 2008. http://mohfw.nic.in/NRHM/asha.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford DB, Saeed K, Ahmad I, Latif S, Mubbashar MH. Stress and psychiatric disorder in rural Punjab. A community survey. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;170:473–478. doi: 10.1192/bjp.170.5.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National AIDS Control Organization, (NACO) UNGASS Country Progress Report 2008 India. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government of India; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) AIDS knowledge and attitudes of black Americans. Vol. 30. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. CDC; Hyattsville, MD: 1989. Mar, p. 165. [Google Scholar]

- Nyamathi A. Comprehensive health seeking and coping paradigm. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1989;14:281–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1989.tb03415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyamathi A, Berg J, Jones T, Leake B. Predictors of perceived health status of tuberculosis infected homeless. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2005;27:896–910. doi: 10.1177/0193945905278385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyamathi A, Christiani A, Nahid P, Gregerson P, Leake B. A randomized controlled trial of two treatment programs for homeless adults with latent tuberculosis infection. International Journal of Tuberculosis & Lung Disease. 2006;10(7):775–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyamathi A, Dixon E, Robbins W, Wiley D, Leake B, Gelberg L. Risk factors for hepatitis C virus infection among homeless adults. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2002;17:143–143. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10415.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyamathi AM, Sinha S, Ganguly KK, William RR, Heravian A, Ramakrishnan P, Rao PV. Challenges experienced by rural women in India living with AIDS and implications for the delivery of HIV/AIDS care. Health Care for Women International. 2011;32(4):300–313. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2010.536282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyamathi A, Thomas B, Greengold B, Swaminathan S. Perceptions and health care needs of HIV positive mothers in India. Progress in Community Health Partnerships. 2009;3.2:99–108. doi: 10.1353/cpr.0.0067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyamathi A, William RR, Ganguly KK, Sinha S, Heravian A, Albarran C, Thomas A, Ramakrishnan P, Greengold B, Ekstrand E, Rama Rao P. Perceptions of women living with AIDS in rural India related to the engagement of HIV-Trained ASHAs for care and support. Journal of HIV/AIDS & Social Services. 2010;9:385–404. doi: 10.1080/15381501.2010.525474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey A, Reddy DC, Ghys PD, Thomas M, Sahu D, Bhattacharya M, Garg R. Improved estimates of India’s HIV burden in 2006. Indian Journal of Medical Research. 2009;129(1):50–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poongothai S, Pradeepa R, Ganesan A, Mohan V. Prevalence of depression in a large urban South Indian population--the Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study (CURES-70) PLoS One. 2009;284(9):e7185. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan BK, Sundar R, Singh K. Socioeconomic impact of HIV and AIDS in India. 2006 Retrieved December 31, 2011, from http://www.undp.org/content/dam/india/docs/socio_economic_impact_of_hiv_and_aids_in_andhra_pradesh.pdf.

- Ramchandani SR, Mehta SH, Saple DG, Vaidya SB, Pandey VP, Vadrevu R, Gupta A. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected adults attending private and public clinics in India. AIDS Patient Care & STDS. 2007;21(2):129–142. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransom D, Heckman TG, Anderson T, Garske J, Holroyd K, Basta T. Telephone-delivered, interpersonal psychotherapy for HIV-infected rural persons with depression: A pilot trial. Psychiatric Services. 2008;59(8):871–877. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.8.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ. Expanding the range of interventions to reduce HIV among adolescents. AIDS. 2000;14(Suppl 1):S33–40. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Stein JA, Lin YY. Impact of parent death and an intervention on the adjustment of adolescents whose parents have HIV/AIDS. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2001;69(5):763–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren S, Kumarsamy N, James R, Raminani S, Solomon S, Mayer KH. ART adherence, demographic variables and CD4 outcome among HIV-positive patients on antiretroviral therapy in Chennai, India. AIDS Care. 2005;17:853–862. doi: 10.1080/09540120500038439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarna A, Pujari S, Sengar AK, Garg R, Gupta I, Dam J. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy and its determinants amongst HIV patients in India. Indian Journal of Medical Research. 2008;127(1):28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlotfeldt R. Nursing in the future. Nursing Outlook. 1981;29:295–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shet A, de Costa A. India calling: Harnessing the promise of mobile phones for HIV healthcare. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2011;16(2):214–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni JM, Kurth AE, Pearson CR, Pantalone DW, Merrill JO, Frick PA. Self-report measures of antiretroviral therapy adherence: A review with recommendations for HIV research and clinical management. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;10(3):227–245. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9078-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steward WT, Steward WT, Herek GM, Ramakrishna J, Bharat S, Chandy S, Wrubel J, Ekstrand ML. HIV-related stigma: Adapting a theoretical framework for use in India. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67(8):1225–1235. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas B, Nyamathi A, Swaminathan S. Impact of HIV/AIDS on mothers in southern India: A qualitative study. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13:989–996. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9478-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Zhou J, Huang L, Li X, Fennie KP, Williams AB. Effects of nurse-delivered home visits combined with telephone calls on medication adherence and quality of life in HIV-infected heroin users in Hunan of China. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2010;19(3–4):380–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR, Bao WN. Depressive symptoms and co-occurring depressive symptoms, substance abuse, and conduct problems among runaway and homeless adolescents. Child Development. 2000;71(3):721–732. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]