Abstract

Whether for pathological examination or for fundamental biology studies, different classes of biomaterials and biomolecules are each measured from a different region of a typically heterogeneous tissue sample, thus introducing unavoidable sources of noise that are hard to quantitate. We describe the method of DNA-encoded antibody libraries (DEAL) for spatially multiplexed detection of ssDNAs and proteins as well as for cell sorting, all on the same diagnostic platform. DEAL is based upon the coupling of ssDNA oligomers onto antibodies which are then combined with the biological sample of interest. Spotted DNA arrays, which are found to inhibit biofouling, are utilized to spatially stratify the biomolecules or cells of interest. We demonstrate the DEAL technique for: (1) the rapid detection of multiple proteins within a single microfluidic channel, and, with the additional step of electroless amplification of gold-nanoparticle labeled secondary antibodies, we establish a detection limit of 10 femtoMolar for the protein IL-2, 150 times more sensitive than the analog ELISA; (2) the multiplexed, on-chip sorting of both immortalized cell lines and primary immune cells with an efficiency that exceeds surface confined panning approaches; and (3) the co-detection of ssDNAs, proteins and cell populations on the same platform.

INTRODUCTION

Global genomic and proteomic analyses of tissues are impacting our molecular-level understanding of many human cancers. Particularly informative are studies that integrate both gene expression and proteomic data. Such multiparameter data sets are beginning to reveal the perturbed regulatory networks which define the onset and progression of cancers.1–5 This new picture of cancer, and the emergence of promising new cancer drugs,6, 7 are placing new demands on clinical pathology.8 For example, traditional pathology practices (i.e. microscopic analysis of tissues) does not distinguish potential responders from non-responders for the new cancer molecular therapeutics.9 Recent examples exist in which pauciparameter molecular measurements are being employed to identify potential responders to at least two therapauetics.10–13 However, it is unlikely that single-parameter measurements will be the norm. Instead, the coupling of molecular diagnostics with molecular therapeutics will eventually require measurements of a multiparameter (e.g. cells, mRNAs and proteins) biomarker panel that can be used to direct patients to appropriate therapies or combination therapies.

Currently, the measurement of a multiparameter panel of biomarkers from diseased tissues requires combinations of microscopic analysis, microarray data,14 immunohistochemical staining, Western Blots,8 and other methods. The collected data is integrated together within some model for the disease, such as a cancer pathway model,15 to generate a diagnosis. Currently, performing these various measurements requires a surgically resected tissue sample. The heterogeneity of such biopsies can lead to significant sampling errors since various measurements of cells, mRNAs, and proteins are each executed from different regions of the tissue.

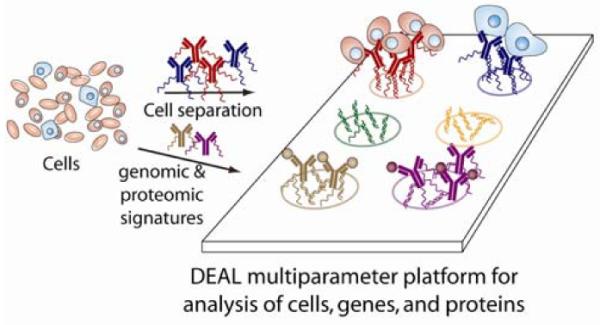

In this paper we describe the DNA-encoded antibody library, or DEAL, approach (Scheme 1), as an important step towards executing a true multiparameter analysis (cells, mRNAs and proteins) from the same microscopic region of tissue. We report on several key demonstrations for achieving this goal, including the rapid detection of proteins and protein panels over a broad dynamic range and with a detection limit of <10 femtoM; the sorting of immortal and primary lymphocyte populations; the co-detection of cells, cDNAs, and proteins on the same platform, and the integration of our multiparameter platform with microfluidic techniques.

Scheme 1.

Illustration of the DEAL method for cell sorting and co-detection of proteins and cDNAs (mRNAs). Antibodies against proteins (for cell sorting) or other proteins (including cell surface markers) are labeled with distinct DNA oligomers. These conjugates may then be combined with the biological sample (cells, tissue, etc.) where they bind to their cognate antigens. When introduced onto a DNA microarray, parallel self assembly, according to Watson-Crick base pairing, localizes the bound species to a specific spatial location allowing for multiplexed, multiparameter analysis.

A key issue involved with a microfluidics-based multiparameter assay is that the measurement of different classes of biomolecules (or cells) typically require different surface chemistries, and not all of them are compatible with each other or the fabrication steps associated with building the microfluidics circuitry. Conventional antibody arrays for protein detection or for panning cells16 require immobilization of the antibody on to aldehyde, epoxy, maleimide, or hydrophobic solid supports.17–20 It is often difficult to preserve folded (active) antibody conformations due to surface induced denaturation which depends on many variables including pH, ionic strength, temperature and concentration.21–23 This has spurred the development of alternative approaches to preserve the native conformation of proteins including 3-dimensional matrixes like hydrogels, and polyacrylamide,24, 25 cutinase-directed antibody immobilization onto SAMs,26 and the coupling of biotinylated antibodies onto streptavidin coated surfaces.27 In addition, the arrays need to remain hydrated throughout the entire manufacturing process in order to prevent protein denaturation.18 DNA microarrays, on the other hand, are typically electrostatically absorbed (via spotting) unto amine surfaces. One option for detecting both DNA and proteins on the same slide would be to pattern both functional groups used to immobilize DNA and protein onto the same substrate, although this would significantly increase the complexity and engineering of the system. Alternatively, a compatible surface may be an activated ester glass slide to which amine-DNA and proteins can both covalently attach. However, we have found that the loading capacity of these slides for DNA is diminished, resulting in poor signal intensity when compared with DNA printed on conventionally prepared amine slides. In addition, unreacted esters are hydrolyzed back to carboxylic acids, which are negatively charged at normal hybridization buffers (pH 7), electrostatically reducing the DNA interaction. Moreover, to interrogate cells and proteins, the best surface to reduce non specific binding of cells while maintaining full antibody functionality is acrylamide,28, 29 which is incompatible with DNA.

By using DNA as a common assembly strategy for cells, cDNAs, and proteins, we are able to optimize the substrate conditions for high DNA loading onto the spotted substrates, and for complementary DNA loading on the antibodies. This leads to highly sensitive sandwich assays for protein detection, as well as high efficiency cell sorting (compared with traditional panning). We also find that non-selective binding (biofouling) of proteins to DNA-coated surfaces is reduced. Importantly, DNA coated surfaces can be dried out, stored or heated (overnight at 80° C), thus making them compatible with robust microfluidics fabrication.

DNA-labeled antibodies have been previously used to detect proteins,30–32 largely with the pendant oligomers serving as immuno-PCR tags.33, 34 DNA-tags have been used to direct the localization of proteins allowing assays to take advantage of spatial encoding, via several different read-out strategies.35–37 Conventional multi-well ELISA assays are capable of quantitating multiple proteins, but typically require separate sample volumes for each parameter. Optical multiplexing can expand this, but is limited by the number of non-spectrally overlapping chromophores. Spatial multiplexing, such as is used with DEAL, allows for the execution of many measurements on a small sample, since the number of different measurements is limited only by the patterning method utilized to prepare the cDNA array. Spotted antibody arrays,18 while potentially useful for protein detection and/or cell sorting, are not easily adaptable towards microfluidics-based assays, since the microfabrication process for preparing robust microfluidics devices often involves physical conditions that will damage the antibodies. Complementary DNA arrays are robust to such fabrication conditions.

EXPERIMENTAL

Reagents

AlexaFluor 488, 594, and 647-labeled polyclonal Goat anti-Human IgGs were purchased from Invitrogen. Monoclonal Rabbit anti-Human Interleukin-4 (clone: 8D4-8), non-fluorescent and APC-labeled Rabbit anti-Human Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (clones: MAb1 and MAb11, respectively), and non-fluorescent and PE-labeled Rabbit anti-Human Interferon-γ (clones: NIB42 and 4S.B3, respectively) were all purchased from eBioscience. Non-fluorescent and biotin-labeled mouse anti-Human Interleukin-2 (clones: 5344.111 and B33-2, respectively) were purchased from BD Biosciences. All DNA strands were purchased with a 5'-amino modification from the Midland Certified Reagent company. Sequences for all six 26-mers and their respective designations are given below:

A1: 5'-NH2-AAAAAAAAAACGTGACATCATGCATG-3' 3'-GCACTGTAGTACGTACAAAAAAAAAA-NH2-5':A1'

B1: 5'-NH2-AAAAAAAAAAGGATTCGCATACCAGT-3' 3'-CCTAAGCGTATGGTCAAAAAAAAAAA-NH2-5':B1'

C1: 5'-NH2-AAAAAAAAAATGGACGCATTGCACAT-3' 3'-ACCTGCGTAACGTGTAAAAAAAAAAA-NH2-5':C1'

In silico DNA orthogonalization

DNA sequences were designed with the objective of minimizing any intra- or intermolecular interactions between the sequences and the complementary targets, at 37°C. The computational design was performed using the paradigm outlined by Dirks et al.38 Up to the time of publication, six orthogonal sequences have been designed and can be found on Supplemental Figure 2 online.

DNA antibody conjugation

Prior to use, all antibodies were desalted, buffer exchanged to pH 7.4 PBS and concentrated to ~ 1mg/ml using 3000 MWCO spin filters (Millipore). Succinimidyl 4-hydrazinonicotinate acetone hydrazone in DMF (SANH, Solulink) was added to the antibodies at variable molar excess of (1000:1 to 5:1) of SANH to antibody. In this way the number of hydrazide groups introduced to the antibodies was varied. Separately, succinimidyl 4-formylbenzoate in DMF (SFB, Solulink) was added at a 20-fold molar excess to 5'aminated 26mer oligomers in PBS. This ratio of SFB to DNA ensured complete reaction of the 5' amine groups to yield 5' aldehydes. No further improvement in yield was observed for both the antibody and oligonucleotide coupling reactions after 4 hours at room temperature. Excess SANH and SFB were removed and samples buffered exchanged to pH 6.0 citrate buffer using protein desalting spin columns (Pierce). A 20-fold excess of derivatized DNA was then combined with the antibody and allowed to react overnight at room temperature. Non-coupled DNA was removed with size exclusion spin columns (Bio-Gel P-30, Bio-Rad) or purified using a Pharmacia Superdex 200 gel filtration column at 0.5 ml/min isocratic flow of PBS. The synthesis of DNA-antibody conjugates was verified by non-reducing 7.5% Tris-HCl SDS-PAGE at relaxed denaturing conditions of 60°C for 5 minutes, and visualized with a Molecular Imager FX gel scanner (Bio-Rad). Conjugation reactions involving fluorescent antibodies or fluorescently-labeled oligonucleotides were imaged similarly using appropriate excitation and emission filters.

Microarray Fabrication

DNA microarrays were printed via standard methods by the microarray facility at the Institute for Systems Biology (ISB--Seattle, WA) onto amine-coated glass slides. Typical spot size and spacing were 150 and 500 μm, respectively. Poly-lysine slides were made in house. Blank glass slides were cleaned with IPA and water in a sonication bath for 10 minutes each. They were then treated with oxygen plasma at 150 W for 60 sec., and then quickly dipped into DI water to produce a silanol terminated, highly hydrophilic surface. After drying them with a nitrogen gun, poly-L-lysine solution (Sigma P8920, 0.1% w/v, without dilution) was applied to the plasma treated surfaces for 15 minutes, and then rinsed off with DI water for several seconds. Finally, these treated slides were baked at 60°C for 1hr. These slides were then sent to ISB and printed as described above.

Fabrication of Microfluidic Devices

Microfluidic channels were fabricated from polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) using conventional soft lithographic techniques. The goal was to fabricate robust microfluidics channels that could be disassembled after the surface assays were complete for optical analysis. Master molds were made photolithographically from a high resolution transparency mask (CadArt) so that the resulting fluidic network consisted of 20 parallel channels each having a cross-sectional profile of 10 × 600 μm and were 2 cm long. This corresponds to channel volumes of 120 nl. A silicone elastomer (Dow Corning Sylgard 184) was mixed and poured on top of the mold. After curing, the PDMS was removed from the mold and sample inlet and outlet ports punched with a 20 gauge steel pin (Technical Innovations). The microfluidic channels were then aligned on top of the microarray and bonded to the substrate in an 80°C oven overnight.

1° Antibody Microarray Generation and DEAL-Based Immunoassays

Antibody microarrays were generated by first blocking the DNA slide with 0.1% BSA in 3× SSC for 30 minutes at 37°C. The slides were washed with dH2O and blown dry. A 30 μl solution containing DNA-antibody conjugates (3× SSC, 0.1% SDS, 0.1% BSA, 15 ng/μl of each conjugate) was sandwiched to the array with a microscope slide, and incubated at 37°C for 4 hours. Arrays were then washed first in 1× SSC, 0.05% SDS at 37°C with gentle agitation, then at 0.2× SSC, then finally at 0.05× SSC. The slides were blown dry and scanned with a Gene Pix 4200 A two-color array scanner (Axon Instruments). For immunoassays, the DNA-encoded 1° antibody (15 ng/μl), antigen (3 ng/μl) and fluorescently-labeled 2° antibody (0.5 ng/μl) were combined in a single tube. After 2 hour incubation at 37°C, the formed antibody-antigen-antibody complexes were introduced to the microarrays as described above. Subsequent wash steps and visualization were identical.

Microfluidics-based assay procedures

Microfluidic devices were interfaced with 23 gauge steel pins and Tygon tubing to allow pneumatically controlled flow rates of ~0.5 μl/min. The assays were performed in Tris Buffered Saline (TBS), which was found to be better than 1× SSC and PBS. Each channel was blocked with 1.0% BSA in TBS prior to exposure to DNA-antibody conjugates or immunoassay pairs for 10 minutes under flowing conditions. After a 10 minute exposure to conjugates or antigens under flowing conditions, channels were washed with buffer for 2 minutes and the microfluidics disassembled from the glass slide in order to be scanned. Immediately prior to imaging, the entire slide was briefly rinsed in TBS, blown dry and imaged on an array scanner as described above. For the human IL-2 concentration series, primary DNA-antibody conjugates were laid down first on the surface, before exposure to antigen and secondary antibody. This was necessary because at lower concentrations of antigen, the signals decrease, due to the high ratio of antigen-unbound primary antibody competing with antigen-bound primary for hybridization to the DNA array. By first exposing the array to the primary DNA-antibody conjugate, excesses were washed away before subsequent exposure to antigen and secondary antibody, increasing signal.

Microfluidic Au amplification methods

Microfluidics-based Au amplification experiments were performed in a similar manner, with the notable exception that a biotin-secondary antibody was used instead of a fluorescently labeled antibody. Subsequently, Au-streptavidin (Nanoprobes) was introduced into each channel (3ng/μl) for 10 minutes, after which the channels were thoroughly rinsed with buffer. After removal of the PDMS, the entire slide was then amplified with gold enhancer kit (Nanoprobes) according to manufacturer's protocol.

Analysis of DNA-encoded antibodies by flow cytometry

VL3 and A-20 cells were incubated for 20 min. on ice with 0.5 μg of FITC-conjugated Rat Anti-Mouse CD90.2 (Thy1.2, BD Pharmingen, clone 30-H12, catalog # 553012) in 100 μL PBS-3% FCS. Cells were also incubated with equimolar amounts of α-CD90.2/FITC-DNA conjugates characterized by various FITC-DNA loadings. Cells were washed once with PBS-3% FCS and then were analyzed by flow cytometry on a BD FACSCanto™ instrument running the BD FACSDiva™ software.

Cell capture, separation, and sorting methods

Two murine cell lines, VL-3 T cells (thymic lymphoma line,39) and A20 B cells (mouse B cell lymphoma,40 purchased from ATCC) were engineered to express mRFP and EGFP, respectively, using standard retroviral transduction protocols. Antibodies against surface markers for each of these cell lines, α-CD90.2 for VL-3 and α-B220 for A20 (eBioscience), were encoded as described above with DNA strands A1' and B1', respectively.

For sorting experiments, cells were passaged to fresh culture media [RPMI 1640 (ATCC) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum, 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids and 0.05 mM β-mercaptoethanol] at a concentration of 106 cells/100 μl media and incubated with DNA-antibody conjugate (0.5 μg/100 μl) for 30 minutes on ice. Excess conjugate was removed from the supernatant after centrifugation, after which cells were resuspended in fresh media. Prior to cell incubation the microarray slide was passivated, to reduce non-specific cell adhesion, by reaction of the residual amine groups with methyl-PEO12-NHS ester (Pierce) 10 mM in pH = 7.4 PBS for 4 hours at room temperature. Cells were spread evenly across the microarray surface and allowed to localize for one hour on ice. After this period, non-adherent cells were removed with gentle washing with room temperature Tris-buffered saline solution including 1 mM MgCl2. Cell enrichment experiments were performed identically except that all incubation steps were performed in the presence of a 1:1 mixture of both T- and B-cells (each at 106/100 μl).

Primary CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were purified from EGFP and dsRed transgenic mice (obtained from Jackson Laboratories), respectively, using standard magnetic bead negative selection protocols and the BD IMagTM cell separation system. Prior to DEAL-based fractionation, the purity of these populations was analyzed by FACS and found to be greater than 80%.

Simultaneous cell, gene and protein experiments were performed similarly to those as previously described on a PEGylated microarray substrate. Briefly, GFP-expressing B cells (106/100 μl) were located on B1 spots after labeling with α-B220-B1' (0.5 μg/100μl). Following removal of non-adherent cells, a TNF-α ELISA pair with C1'-encoded 1° and APC-labeled 2° antibodies were introduced along with 0.5 ng/μl FITC-labeled A1' and allowed to hybridize for a period of 30 minutes at room temperature. The slide was then rinsed with TBS+MgCl2 and visualized via brightfield and fluorescence microscopy.

Homogeneous and panning cell experiments were performed in parallel. For the homogenous cell capture process, 5×106 Jurkats (ATCC) suspended in 1 ml of RPMI media along with 5 μg of α-CD3/C3' conjugates and incubated on ice for 1 hour. Excess conjugates were removed by centrifugation and the Jurkats were resuspended into 200 μl of fresh media before exposure to the DNA microarray. After 1 hour incubation on ice, the slides were rinsed gently with TBS. The cell panning experiments were performed in parallel; 5 ug of a-CD3/C3' conjugate in 1 ml RPMI media was incubated on a microarray for 1 hour on ice before rinsing in 0.5× PBS, then deionized water. The slide was not blown dry, but gently tapped on the side to remove the majority of the excess solution, keeping the array hydrated. Jurkats (5×106/200 μL) were immediately placed on the array for one hour on ice. Subsequent wash and visualization steps are identical.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Generation of DNA-Antibody conjugates

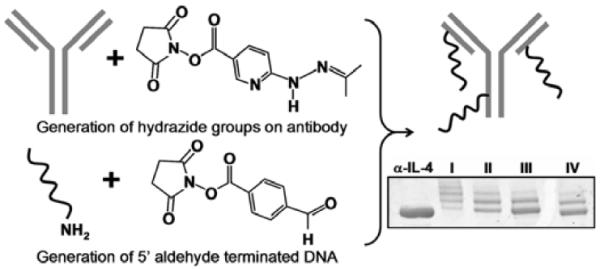

Chemically modified antibodies to aid in protein immobilization and/or detection are nearly universal for use in immunoassays. Such labeling introduces the risk of detrimentally affecting antibody function; however, that risk can be reduced by minimizing the size, and thus the steric hindrance, of the pendant moieties. With this in mind, we employed a covalent conjugation strategy in which 5'-aminated single-stranded oligonucleotides were coupled to antibodies via a hydrazone linkage,31 as shown in Scheme 2. Using commercially-available reagents, an aldehyde functionality was introduced to the 5'-aminated oligonucleotide via succinimide chemistry. Similarly, a hydrazide moiety was introduced via reaction with the lysine side chains of the respective antibody. DNA-antibody conjugate formation was then facilitated via stoichiometric hydrazone bond formation between the aldehyde and hydrazide functionalities. Conjugate formation and control over DNA-loading41 was verified by PAGE electrophoresis, as shown in Scheme 2.

Scheme 2.

Illustration of the two step coupling strategy utilized to prepare DEAL antibodies. In parallel, hydrazide groups are introduced onto a monoclonal antibody and 5' aldehyde modified single-stranded DNA is prepared from 5' aminated oligomers. When combined, hydrazone bonds are formed, linking the ssDNA to the antibody. At bottom right is a gel mobility shift assay showing varied oligomer (strand A1') loading unto α-human IL-4. By varying the stoichiometric ratios of SANH to antibody (lanes I–IV corresponds to 300:1, 100:1, 50:1, 25:1 respectively), the average number of attached oligonucleotides can be controlled.

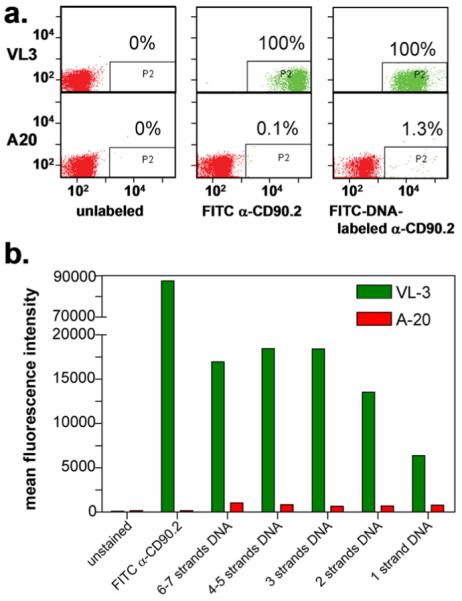

Clearly the adverse steric effects of tagging antibodies with oligonucleotides are of concern when performing various assays, such as the immunoassays and cell sorting/capture experiments described herein. For this reason, we investigated the ability of DNA-encoded antibodies to retain recognition of cell surface markers, as visualized by fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS). By using a fluorophore covalently-tagged onto the DNA, but not the antibody, FACS was used to optimize DNA-loading for the DEAL conjugates. For the analysis, 5' aminated, 3' FITC-labeled DNA was tagged unto α-CD90.2 antibodies at various stoichiometric ratios of SANH to antibody (5:1, 25:1, 50:1, 100:1, 300:1). This produced, on average, conjugates with 1, 2, 3, 4–5 and 6–7 strands of FITC-DNA respectively, as measured by gel mobility shift assays (Scheme 1). These conjugates were tested for their ability to bind to the T cell line VL3 (CD90.2 expressing), by monitoring the FITC fluorescence with the flow cytometer. The B cell line A20 (CD90.2 negative) was used as a negative control. The performance of the conjugates was also compared with commercially available FITC α-CD90.2. The results are shown in Figure 1. The histogram of the mean fluorescent intensities for various FITC-DNA loadings shows that fluorescence increases are roughly linear when the number of DNA strands is increased from 1 to 2 to 3, corresponding to 1, 2 and 3 chromophores (1 per strand). At higher loadings, the increase in fluorescence first plateaus (4–5 oligomers) and then decreases up to the highest loading (6–7 oligomers). Thus, excess DNA labels (4–7 oligomers) did sterically reduce the ability of antibodies to recognize cell surface markers. Optimal loading for cell surface marker recognition was achieved with antibodies synthesized with the 50:1 SANH:antibody ratio – corresponding to approximately three DNA strands per antibody. Subsequent cell sorting experiments were performed in consideration of this observation. When compared with the FITC α-CD90.2 control, the DNA antibody conjugates had reduced fluorescence by a factor of 10 and slightly higher nonspecific binding to A20 cells. This could be due to a couple of reasons. A likely factor is that the stoichiometric ratio of fluorophore to antibody for the DEAL conjugates versus the commercial antibody is different. For the DEAL conjugates, each strand of DNA is attached to one fluorophore only (i.e. conjugates with one DNA strand has a fluorophore to antibody ratio of 1:1) whereas the commercial antibodies generally have more than one fluorophore per antibody (i.e. fluorescent antibodies have a fluorophore to antibody ratio >1). Thus the factor of 10 less fluorescence should not be strictly interpreted as a 10× reduction in the binding affinity of the DEAL conjugates, although it is possible that the oligomer steric effects discussed earlier do account for some reduction in relative fluorescence intensity. Direct measurement of the affinity of the DEAL conjugate compared with the corresponding unmodified antibody using methods like Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) will be more conclusive.

Figure 1.

Optimization of DNA loading of DEAL antibodies for cell surface marker recognition. (a). FACS plot comparing α-CD90.2/FITC-DNA conjugates with the commercially-available FITC α-CD90.2 antibody (no DNA). The conjugates bind to VL3 cells (100%) with minimal non-specific interactions with A20 (1.3%). When compared with FITC α-CD90.2, the overall fluorescent intensities are lower by a factor of 10, with slightly higher non-specific binding to A20. (b). Histogram of the mean fluorescent intensities for various FITC-DNA loadings. Fluorescence increases are roughly linear when the number of DNA strands is increased from 1 to 2 to 3, corresponding to the 1, 2 and 3 chromophores (1 per strand). For higher loadings, the fluorescence plateaus and then decreases.

Multiplexed protein detection by DEAL

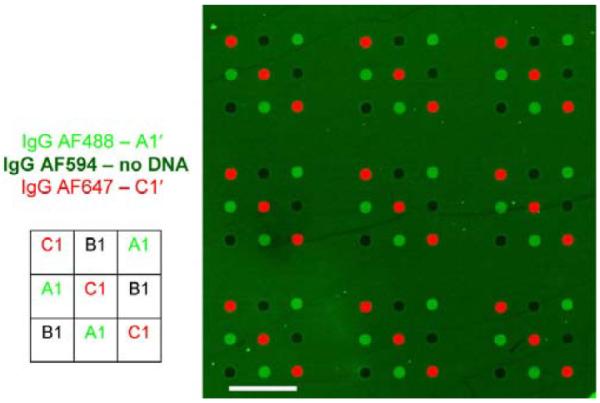

We demonstrated the DEAL concept for spatially localizing antibodies using three identical goat anti-human IgGs, each bearing a different molecular fluorophore and each encoded with a unique DNA strand. A solution containing all three antibodies was then introduced onto a microarray spotted with complementary oligonucleotides. After a two hour hybridization period and substrate rinse, the antibodies self-assembled according to Watson-Crick base-pairing, converting the >900 spot complementary DNA chip into a multi-element antibody microarray (Supplementary Figure 1 online). This observation implied that quite large antibody arrays can be assembled in similar fashion.

The ultimate size of any protein array, however, will likely be limited by interference from non-specific binding of proteins. In an effort to visualize the contributions of non-specific binding, three antibodies were similarly introduced onto a microarray: two antibodies having complementary DNA-labeling spotted oligonucleotides and a third unmodified antibody (Fig. 2). For demonstration purposes, the slide was not thoroughly rinsed following hybridization and accordingly a high background signal due to non-specific adsorption of non-encoded fluorescently-labeled antibody was observed. The spotted nucleotide regions, to which no antibody was chemically encoded, displayed much less non-specifically attached protein, implying that DNA greatly diminishes active area biofouling. Such retardation of biofouling is reminiscent of substrates that are functionalized with polyethyleneglycol (PEG).41–43 By analogy with postulated mechanisms associated with PEG,44–46 we hypothesize that the hydrophilic nature of the spotted oligonucleotides minimizes interactions with hydrophobic portions of proteins often exposed during non-specific adsorption. Conjugate hybridization experiments were also carried out within 5 degrees of the calculated duplex melting temperatures, taking advantage of Watson-Crick stringencies and thus diminishing non-complementary DNA interactions. In any case, this reduced biofouling means that the DEAL method can likely be harnessed to detect reasonably large panels of proteins within a single environment.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the resistance of the DEAL approach towards non-specific protein absorption. A microarray was simultaneously exposed to goat α-human IgG-Alexa488/A1', goat α-human IgGAlexa647/C1' DEAL conjugates and goat α-human IgG-Alexa594 with no pendant DNA. When the arrays were not fully blocked and/or rinsed, non-specific binding was observed on the surface of the glass slide, but not on the non-complementary spots of printed DNA, i.e., spot B1 did not have fluorescence from non-complementary IgG conjugates nor did it exhibit fluorescence from proteins not encoded with DNA (goat α-human IgGAlexa594). Scale bar corresponds to 1mm.

Another important empirical observation is the level of cross talk between non-complementary DNA strands. The DNA sequences A1, B1, C1 along with their complements were generated randomly. The inclusion of a 5' A10 segment for flexibility and a recognition length of 16 bases were the only constraints. In running the experiments, it was discovered that there is a low but appreciable amount of noise generated from mismatched sequences due to nonlinear secondary interactions. Stringency washes alone were not able to clean the noise appreciably. In any realistic multiparameter platform, this noise can grow in proportion to the number of parameters in investigation. Thus, the model platform should utilize DNA sequences which are orthogonal to each other and also orthogonal to all the exposed complementary strands printed on the DNA array. We have performed in silico orthogonalization of DNA oligomers, and have generated a list of sequences that have been empirically verified (Supplemental Figure 2 online). These efforts are ongoing and the list of orthogonal DNA sequences is expected to grow. These observations were made at the time of submission and thus will be further elaborated in full detail in a future manuscript.

Detection of multiple proteins within a single microfluidic channel

Microfluidic-based assays offer advantages such as reduced sample and reagent volumes, and shortened assay times.47 For example, under certain operational conditions, the surface binding assay kinetics are primarily determined by the analyte (protein) concentration and the analyte/antigen binding affinity, rather than by diffusion.48 We evaluated a microfluidics-based DEAL approach by bonding a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)-based microfluidic channel on top of a DNA microarray. We initially performed a multiplexed antibody localization experiment, similar to that described above. The antibody conjugates self-assembled at precise spatial locations encoded by the pendant oligonucleotide in <10 minutes (Supplementary Figure 3 online), consistent with the time scales reported on DNA hybridization in microfluidics.49–51

To validate the DEAL strategy for protein detection, we utilized encoded antibodies to detect cognate antigens in a variant of standard immunoassays. In a standard immunoassay,52 a primary antibody is adsorbed onto a solid support, followed by the sequential introduction and incubation of the antigen-containing sample and secondary labeled “read-out” antibody, with rinsing steps in between. In order to simplify this conventional five step immunoassay, we reasoned that the encoding power of the DEAL antibodies could serve to position the entire sandwich complex to the appropriate location for multiplexed readout, reducing the assay to a single step. To test this concept, in the same solution, a non-fluorescent, DNA-encoded 1° antibody was combined with antigen and a fluorescently-labeled (no DNA) 2° antibody. Under these conditions, a fluorescent signal will be spatially encoded only if an antibody-antigen-antibody sandwich is successfully formed in homogeneous solution and localized onto the microarray. Upon introduction of DNA-encoded antibodies against two cytokines, human IFN-γ and TNF-α, cognate antigens and fluorescently-labeled 2° antibodies, the DEAL sandwich assays self-assembled to their specific spatial locations where they were detected, as shown in Figure 3a. This multi-protein immunoassay also took 10 minutes to complete.

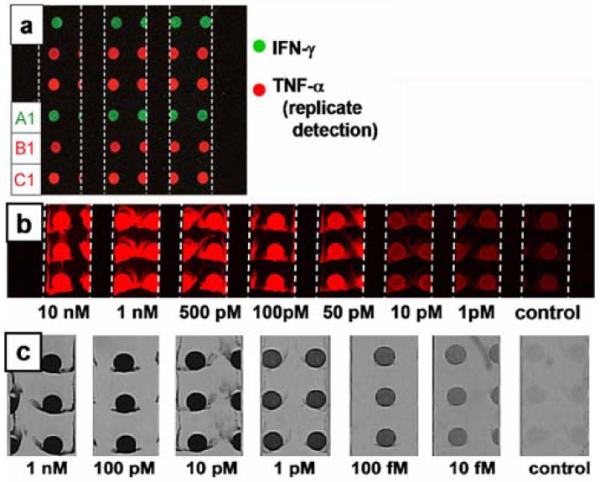

Figure 3.

Fluorescence and brightfield images of DNA-templated protein immunoassays executed within microfluidic channels. The 600 μm micrometer wide channels are delineated with white dashed lines. (a). Two parameter DEAL immunoassay showing the detection of IFN-γ at spot A1 with a PE labeled 2° antibody (green channel) and replicate detection of TNF-α at spots B1 and C1 with an APC labeled 2° antibody (red channel). (b). Human IL-2 concentration series visualized using a fluorescent 2° antibody for detection. (c). Human IL-2 concentration series developed using Au electroless deposition as a visualization and amplification strategy.

We explored the sensitivity limits of a microfluidics, DEAL-based sandwich immunoassay, using a third interleukin, IL-2. Using a fluorescent readout strategy, the assay peaked with a sensitivity limit of around 1 nM on slides printed at saturating concentrations of 5 μM of complementary DNA (data not shown). Several strategies were employed to increase the sensitivity. First, we reasoned that increasing the loading capacity of the glass slide for DNA will increase the density of DEAL conjugates localized and therefore, increase the number of capture events possible. Conventional DNA microarrays are printed on primary amine surfaces generated by reacting amine-silane with glass.53 DNA strands are immobilized through electrostatic interactions between the negative charges on the phosphate backbone of DNA and the positive charges from the protonated amines at neutral pH conditions. To increase the loading capacity of the slide, we generated poly-lysine surfaces, increasing both the charge density as well as the surface area of interaction with DNA. By adopting these changes, it became possible to print complementary DNA at saturating concentrations of 100 μM on the glass slides. Correspondingly, the sensitivity of the fluorescent based assays increased to 10 pM (Fig. 3b). In addition, we chose to employ Au nanoparticle-labeled 2° antibodies, followed by electroless metal deposition,54 to further amplify the signal and transform a florescence based read out to an optical one. This is possible since spatial, rather than colorimetric multiplexing, is utilized. Adopting these improvements, the presence of IL-2 interleukin can be readily detected at a concentration limit less than 10 fM (Fig. 3c), representing at least a 1000-fold sensitivity increase over the fluorescence based microfluidics immunoassay. In comparison, this method is 100–1000 fold more sensitive than conventional ELISA,55 and 150 times more sensitive than the corresponding human IL-2 ELISA data from the manufacturer.56

In performing these experiments, the idea of a 1 step immunoassay was revised. The sensitivity of the assays was reduced when performing a 1 step immunoassay, especially at lower concentrations of antigen. This is most likely due to competitive binding between DEAL conjugates with and without cargo for hybridization unto the underlying DNA microarray. By sequentially exposing the array to DEAL conjugate, antigen, and then secondary antibody, the sensitivities were increased. This is a clear trade off between convenience and sensitivity. It should still be stressed however, that maximum signal is still reached under microfluidic flowing conditions within 10 minutes for each step. Thus in a fully automated device, a complete microfluidic immunoassay with sensitivities down to 10 fM can be obtained in 1 hour (including a 30 minute step for Au amplification).

In addition to the sample size and time-scale benefits that accompany this type of microfluidics immunoassay, there are other advantages. For example, since the entire assay is performed in solution prior to read-out, protein denaturation (a concern for spotted antibody microarrays) does not reduce binding efficiency. In addition, any assay that involves substrate-supported antibodies, would not have survived microfluidic chip assembly (which involved an extended bake at 80°C). That procedure was designed to yield robust PDMS microfluidics channels that could then be disassembled for the optical readout step. Another benefit of performing solution phase assays is that the orientational freedom enjoyed by both the antigens and antibodies ensures that the solid support will not limit the access of analytes to the binding pocket of the capture agent. We explore this issue in further detail below in the section of cell sorting. Other improvements, such as reducing the DNA spot size,57 and removing spot redundancy are currently being investigated to further lower detection limits.

Multiplexed sorting of immortalized and primary immune cells

We extended the DEAL technique for multiplexed cell sorting. The most common method for cell sorting is FACS, which is well-suited for many applications. Unfortunately, cells separated by conventional FACS are not immediately available for post-sorting analysis of gene and/or protein expression. In addition, FACS is also limited by the number of spectrally distinct fluorophores that can be utilized to label the cell surface markers used for the sorting. FACS, however, is robust in sorting cells according to multiple cell surface markers. Amongst other alternative cell sorting strategies, the traditional panning method, in which cells interact with surface marker-specific antibodies printed onto an underlying substrate,58 is particularly relevant. Panning is capable of separating multiple cell populations, but has the same limitations as conventional spotted protein microarrays, namely that antibodies are not always oriented appropriately on a surface, and they can also dry out and lose functionality. DEAL overcomes this limitation, by keeping all reagents in solution.

We compared DEAL-based cell sorting with panning by evaluating homogeneous cell capture (solution phase cell capture) and heterogeneous capture of cells (surface confined cell capture). The homogeneous DEAL method exhibited a higher cell capture efficiency as shown in Figure 4a. The increase in capture efficiency can be attributed to several factors. In homogeneous cell capture, the DEAL conjugates are allowed to properly orient and bind to the cell surface markers in solution. Cell capture is not driven by antibody to cell surface marker interactions, but rather by the increased avidity of the multivalent DEAL conjugates for the complementary DNA strands on the microarray through cooperative binding, greatly increasing capture efficiency. Similar trends have been reported for nanoparticle, DNA hybridization schemes.59 With this process, it is typical to see a DNA spot entirely occupied by a confluent layer of cells. With panning methods, which are analogous to our (heterogeneous) DEAL defined arrays, the capture agents are restricted to adopt a random orientation on the surface. The activity of the antibodies is reduced, simply because of improper orientation for interaction with the cell surface markers, decreasing maximum avidity and cooperation with neighboring antibodies.

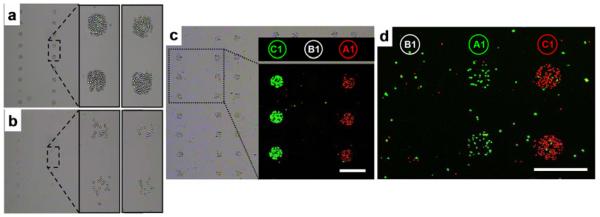

Figure 4.

The optimization and use of DEAL for multiplexed cell sorting. (a & b). Brightfield images showing the efficiency of the homogeneous DEAL cell capture process. (a). A homogeneous assay in which DEAL labeled antibodies are combined with the cells, and then the mixture is introduced onto the spotted DNA array microchip. (b). DEAL labeled antibodies are first assembled onto a spotted DNA array, followed by introduction of the cells. This heterogeneous process is similar to the traditional panning method of using surface bound antibodies to trap specific cells. The homogeneous process is clearly much more efficient. (c). Brightfield and fluorescence microscopy images of multiplexed cell sorting experiments where a 1:1 mixture of mRFP-expressing T cells (red channel) and EGFP-expressing B cells (green channel) is spatially stratified onto spots A1 and C1, corresponding to the encoding of α-CD90.2 and α-B220 antibodies with A1' and C1', respectively. (d). Fluorescence micrograph of multiplexed sorting of primary cells harvested from mice. A 1:1 mixture of CD4+ cells from EGFP transgenic mice and CD8+ cells from dsRed transgenic mice are separated to spots A1 and C1 by utilizing DEAL conjugates α-CD4-A1' and α-CD8-C1', respectively.

We also investigated the use of DEAL for multiplexed cell sorting. Two unique DNA strands were conjugated to antibodies raised against the T cell marker CD90.2 (Thy1.2) and the B cell marker CD45R (B220), respectively. Multiplexed DEAL-based cell sorting was demonstrated by spatially separating a 1:1 mixture of monomeric Red fluorescent protein60 (mRFP)-expressing T cells (VL-3, murine thymic lymphoma) and EGFP-expressing B cells (mouse B cell lymphoma). This mixture was incubated with uniquely-encoded DNA-antibody conjugates against both T and B cell markers and introduced to an appropriately spotted microarray. Figure 4a shows both brightfield and false color fluorescence micrographs demonstrating that the mRFP-expressing T cells are enriched at spots A1 and EGFP-expressing B-cells located at B1, consistent with the DNA-encoding of the respective antibodies.

Primary cells are usually more fragile than established cell lines. This is due to the fact that they have to be extracted (usually by enzymatic digestions) from the surrounding tissues, a process that can lead to decreased viability. Moreover, the culture process often selects for clones characterized by greatly increased viability as well as proliferation potential. A generalized cell sorting technology must therefore also work on primary cells with minimal sample manipulation. To demonstrate the utility of DEAL for primary cell sorting, a synthetic mixture of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was isolated via magnetic negative depletion from EGFP- and dsRED- transgenic mice, respectively. The mixture was stratified using α-CD4 and α-CD8 DNA-antibody conjugates. As shown in Figure 4b, the two cell types were separated to different spatial locations according to the pendant DNA encoding.

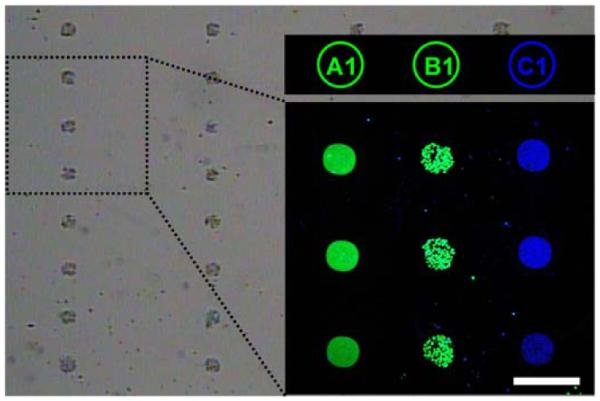

Single environment detection of specific cDNAs, proteins and cells

To highlight the universal diversity of this platform, GFP-expressing B cells were tagged with B1' DNA-encoded antibody conjugates and spatially located onto spots (B1) encoded with the complementary oligonucleotide. Post cell localization, FITC-labeled A1' DNA and a C1'-encoded TNF-α immunosandwich, were combined and introduced to the same microarray platform. The resulting brightfield and fluorescence microscopy images, shown in Figure 5, demonstrate the validity of the DEAL platform for simultaneously extending across different levels of biological complexity.

Figure 5.

Microscopy images demonstrating simultaneous cell capture at spot B1 and multiparameter detection of genes and proteins, at spots A1 and C1, respectively. The brightfield image shows EGFP-expressing B cells (green channel) located to spots B1, FITC-labeled (green) cDNA at A1, and an APC-labeled TNF-α sandwich immunoassay (blue) encoded to C1. The scale bar corresponds to 300 μm.

CONCLUSIONS

By utilizing DNA as a universal linkage we have demonstrated a platform capable of simultaneous cell sorting, ssDNA and protein detection. DEAL represents a promising approach for the large scale, multiparameter analysis of biological samples. We are currently applying DEAL towards the separation of highly complex primary cell mixtures such as whole mouse spleen and whole mouse thymus extracts. In addition, microfluidics-based DEAL immunoassays arrays are currently being harnessed for the analysis of protein biomarker panels from mouse whole-blood. We are particularly interested in integrating DEAL with advanced, on chip tissue handling tasks followed by simultaneous quantitation of mRNAs and proteins, because this is where DEAL can potentially assist in pathological analysis of cancerous tissues. From a more fundamental cancer biology perspective, a near-term targeted application is the capture and functional evaluation of tumor-specific cytotoxic lymphocytes.28, 61 Such an application requires both rare cell capture, cell activation, and the subsequent detection of secreted proteins. For such problems, DEAL has the potential to eliminate any adverse effects of sample dilution and can thus greatly simplifying the analysis of the biological system.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Leroy Hood, Paul Mischel and Toni Ribas for helpful discussions. We also thank Bruz Marzolf at the Institute for Systems Biology (Seattle, WA) for printing DNA microarrays and Mireille Riedinger at UCLA for outstanding technical assistance with primary cell purifications. The VL-3 T cells were a kind gift from Dr. Stephen Smale at UCLA. We thank Harry Choi and Suvir Venkataraman in the Pierce group at Caltech for their help in generating the orthogonal DNA sequences. This work was funded by the National Cancer Institute #5U54 CA119347 (JRH, PI) and by the DOE-funded Institute for Molecular Medicine Laboratory. Owen Witte is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lin B, White JT, Lu W, Xie T, Utleg AG, Yan X, Yi EC, Shannon P, Khretbukova I, Lange PH, Goodlett DR, Zhou D, Vasicek TJ, Hood L. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3081–3091. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kwong KY, Bloom GC, Yang I, Boulware D, Coppola D, Haseman J, Chen E, McGrath A, Makusky AJ, Taylor J, Steiner S, Zhou J, Yeatman TJ, Quackenbush J. Genomics. 2005;86:142–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huber M, Bahr I, Kratzchmar JR, Becker A, Muller E-C, Donner P, Pohlenz H-D, Schneider MR, Sommer A. Molec. Cell. Proteomics. 2004;3:43–55. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M300047-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tian Q, Stepaniants SB, Mao M, Weng L, Feetham MC, Doyle MJ, Yi EC, Dai H, Thorsson V, Eng J, Goodlett D, Berger JP, Gunter B, Linseley PS, Stoughton RB, Aebersold R, Collins SJ, Hanlon WA, Hood LE. Molec. Cell. Proteomics. 2004;3:960–969. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400055-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen G, Gharib TG, Huang C-C, Taylor JMG, Misek DE, Kardia SLR, Giordano TJ, Iannettoni MD, Orringer MB, Hanash SM, Beer DG. Molec. Cell. Proteomics. 2002;1:304–313. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m200008-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prados M, Chang S, Burton E, Kapadia A, Rabbitt J, Page M, Federoff A, Kelly S, Fyfe G. Proc. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncology. 2003;22:99. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rich JN, Reardon DA, Peery T, Dowell JM, Quinn JA, Penne KL, Wikstrand CJ, van Duyn LB, Dancey JE, McLendon RE, Kao JC, Stenzel TT, Rasheed BKA, Tourt-Uhlig SE, Herndon JE, Vredenburgh JJ, Sampson JH, Friedman AH, Bigner DD, Friedman HS. J. Clin. Oncology. 2004;22:133–142. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mellinghoff IK, Wang MY, Vivanco I, Haas-Kogan DA, Zhu S, Dia EQ, Lu KV, Yoshimoto K, Huang JHY, Chute DJ, Riggs BL, Horvath S, Liau LM, Cavenee WK, Rao PN, Beroukhim R, Peck TC, Lee JC, Sellers WR, Stokoe D, Prados M, Cloughesy TF, Sawyers CL, Mischel PS. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;353:2012–2024. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Betensky RA, Louis DN, Cairncross JG. J. Clin. Oncology. 2002;20:2495–2499. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.06.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hughes T, Branford S. Semin Hematol. 2003;2(Suppl 2):62–68. doi: 10.1053/shem.2003.50044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamb J, Crawford ED, Peck D, Modell JW, Blat IC, Wrobel MJ, Lerner J, Brunet JP, Subramanian A, Ross KN, Reich M, Hieronymus H, Wei G, Armstrong SA, Haggarty SJ, Clemons PA, Wei R, Carr SA, Lander ES, Golub TR. Science. 2006;313(5795):1929–1935. doi: 10.1126/science.1132939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin M. Clin. Transl Oncol. 8(1):7–14. doi: 10.1007/s12094-006-0089-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Radich JP, Dai H, Mao M, Oehler V, Schelter J, Druker B, Sawyers CL, Shah N, Stock W, Willman CL, Friend S, Linsley PS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006;103(8):2794–2799. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510423103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mischel PS, Cloughesy TF, Nelson SF. Nature Rev. Neuroscience. 2004;5:782–94. doi: 10.1038/nrn1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weinberg RA. Cancer Biology. Garland Science; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wysocki LJ, Sato VL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1978;75(6):2844–2848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.6.2844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu X, Wang H, Herron J, Prestwich G. Bioconjugate Chem. 2000;11(755–761) doi: 10.1021/bc000006d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Macbeath G, Schreiber SL. Science. 2000;289:1760–1763. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5485.1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pal M, Moffa A, Sreekumar A, Ethier S, Barder T, Chinnaiyan A, Lubman D. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:702–710. doi: 10.1021/ac0511243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thirumalapura NR, Morton RJ, Ramachandran A, Malayer JR. Journal of Immunological Methods. 2005;298:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seigel RR, Harder P, Dahint R, Grunze M, Josse F, Mrksich M, Whitesides GM. Anal. Chem. 1997;69:3321–3328. doi: 10.1021/ac970047b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramsden JJ. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1995;24:73–78. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fainerman VB, Lucassen-Reynders E, Miller R. Colloids Surf. A. 1998;143:141. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arenkov P, Kukhtin A, Gemmel A, Voloshchuk S, Chupeeva V, Mirzabekov A. Anal. Biochem. 2000;278:123–131. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiyonaka S, Sada K, Yoshimura I, Shinkai S, Kato N, Hamachi I. Nature Materials. 2004;3:58–64. doi: 10.1038/nmat1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kwon Y, Han Z, Karatan E, Mrksich M, Kay BK. Anal. Chem. 2004;76:5713–5720. doi: 10.1021/ac049731y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peluso P, Wilson D, Do D, Tran H, Venkatasubbaiah M, Quincy D, Heidecker B, Poindexter K, Tolani N, Phelan M, Witte K, Jung L, Wagner P, Nock S. Anal. Biochem. 2003;312:113–124. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(02)00442-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen DS, Soen Y, Stuge TB, Lee PP, Weber JS, Brown PO, Davis MM. PLoS Medicine. 2005;2:1018–1030. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soen Y, Chen DS, Kraft DL, Davis MM, Brown PO. PLoS Biology. 2003;1(3):429–438. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boozer C, Ladd J, Chen S, Yu Q, Homola J, Jiang S. Anal. Chem. 2004;76:6967–6972. doi: 10.1021/ac048908l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kozlov IA, Melnyk PC, Stromsborg KE, Chee MS, Barker DL, Zhao C. Biopolymers. 2004;73:621–630. doi: 10.1002/bip.20009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adler M, Wacker R, Booltink E, Manz B, Niemeyer CM. Nature Methods. 2005:147–149. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sano T, Smith CL, Cantor CR. Science. 1992;258:120–122. doi: 10.1126/science.1439758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niemeyer CM, Adler M, Wacker R. TRENDS Biotech. 2005;23:208–216. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wacker R, Niemeyer CM. ChemBioChem. 2004;5:453–459. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Becker CFW, Wacker R, Bouschen W, Seidel R, Kolaric B, Lang P, Schroeder H, Muller O, Niemeyer CM, Spengler B, Goody RS, Engelhard M. Angew. Chem. 2005;44:7635–7639. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boozer C, Ladd J, Chen S, Jiang S. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:1515–1519. doi: 10.1021/ac051923l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dirks RM, Lin M, Winfree E, Pierce NA. Nucleic Acids Research. 2004;32(4):1392–1403. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Groves T, Katis P, Madden Z, Manickam K, Ramsden D, Wu G, Guidos CJ. J. Immunol. 1995;154:5011–5022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim KJ, Langevin CK, Merwin RM, Sachs DH, Asfsky R. J. Immunol. 1979;122:549–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.This approach to conjugate synthesis is expected to result in a distribution of DNA loadings for each antibody, however, we feel as this effect is exaggerated in preparation for PAGE analysis. We observed that normal conditions for the heat-induced denaturation proceeding gel electrophoresis (100° for 5 minutes) reduced the number of DNA-strands visualized, presumably by breaking the hydrazone linkage between the DNA and the protein. By relaxing the denaturing conditions, a sample heated at 60° for 5 minutes (minimum required for good gel) showed up to 7 discrete bands, whereas the same sample heated at 100° for 5 minutes showed no pendant oligonucleotides.

- 42.Prime KL, Whitesides GM. Science. 1991;252:1164–1167. doi: 10.1126/science.252.5009.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prime KL, Whitesides GM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115(23):10714–10721. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jeon SI, Lee JH, Andrade JD, De Gennes PG. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 1991;142(1):149–158. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jeon SI, Andrade JD. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 1991;142(1):159–166. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andrade JD, Hlady V. Advances in Polymer Science. 1986;79(1–63) [Google Scholar]

- 47.Breslauer DN, Lee PJ, Lee LP. Mol. BioSyst. 2006;2:97–112. doi: 10.1039/b515632g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zimmermann M, Delamarche E, Wolf M, Hunziker P. Biomedical Microdevices. 2005;7(2):99–110. doi: 10.1007/s10544-005-1587-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Erickson D, Li D, Krull U. Anal. Biochem. 2003;317:186–200. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(03)00090-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bunimovich Y, Shin Y, Yeo W, Amori M, Kwong G, Heath J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006 doi: 10.1021/ja065923u. (web release 12 1 2006) DOI: 10.1021/ja065923u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wei C, Cheng J, Huang C, Yen M, Young T. Nucleic Acids Research. 2005;33(8):1–11. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Engvall E, Perlmann PO. J. Immunol. 1972;109:129–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pirrung M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:1276–1289. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020415)41:8<1276::aid-anie1276>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hainfeld JF, Powell RD. Silver- and Gold-Based Autometallography of Nanogold. In: Hacker GW, Gu J, editors. Gold and Silver Staining: Techniques in Molecular Morphology. CRC Press; Washington, DC: 2002. pp. 29–46. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Crowther JR. Methods in Molecular Biology. Humana Press Inc.; Totowa, New Jersey: 1995. ELISA; Theory and Practice. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. http://www.bdbiosciences.com/ptProduct.jsp?prodId=6725.

- 57.Thibault C, Le Berre V, Casimirius S, Tervisiol E, Francois J, Vieu C. Journal of Nanobiotechnology. 2005;3(7):1–12. doi: 10.1186/1477-3155-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cardoso AA, Watt SM, Batard P, Li ML, Hatzfeld A, Genevier H, Hatzfeld J. Exp. Hematol. 1995;23:407–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Taton TA, Mirkin CA, Letsinger RL. Science. 2000;289:1757–1760. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5485.1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Campbell RE, Tour O, Palmer AE, Steinbach PA, Baird GS, Zacharias DA, Tsien RY. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2002;99:7877–7882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082243699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Soen Y, Chen DS, Kraft DL, Davis MM, Brown PO. PLos Biology. 2003;1:429–438. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.