Abstract

Acquired resistance to anticancer treatments is a substantial barrier to reducing the morbidity and mortality that is attributable to malignant tumors. Components of tissue microenvironments are recognized to profoundly influence cellular phenotypes, including susceptibilities to toxic insults. Using a genome-wide analysis of transcriptional responses to genotoxic stress induced by cancer therapeutics, we identified a spectrum of secreted proteins derived from the tumor microenvironment that includes the Wnt family member wingless-type MMTV integration site family member 16B (WNT16B). We determined that WNT16B expression is regulated by nuclear factor of κ light polypeptide gene enhancer in B cells 1 (NF-κB) after DNA damage and subsequently signals in a paracrine manner to activate the canonical Wnt program in tumor cells. The expression of WNT16B in the prostate tumor microenvironment attenuated the effects of cytotoxic chemotherapy in vivo, promoting tumor cell survival and disease progression. These results delineate a mechanism by which genotoxic therapies given in a cyclical manner can enhance subsequent treatment resistance through cell nonautonomous effects that are contributed by the tumor microenvironment.

A major impediment to more effective cancer treatment is the ability of tumors to acquire resistance to cytotoxic and cytostatic therapeutics, a development that contributes to treatment failures exceeding 90% in patients with metastatic carcinomas1. Efforts focused on circumventing cellular survival mechanisms after chemotherapy have defined systems that modulate the import, export or metabolism of drugs by tumor cells2–6. Enhanced damage repair and modifications to apoptotic and senescence programs also contribute to de novo or acquired tolerance to anti-neoplastic treatments3,7,8. In addition, the finding that ex vivo assays of sensitivity to chemotherapy do not accurately predict responses in vivo indicate that tumor microenvironments also contribute substantially to cellular viability after toxic insults9–11. For example, cell adhesion to matrix molecules can affect life and death decisions in tumor cells responding to damage12–14. Further, the spatial organization of tumors relative to the vasculature establishes gradients of drug concentration, oxygenation, acidity and states of cell proliferation, each of which may substantially influence cell survival and the subsequent tumor repopulation kinetics15,16.

Most cytotoxic agents selectively target cancers by exploiting differential tumor cell characteristics, such as high proliferation rates, hypoxia and genome instability, resulting in a favorable therapeutic index. However, cancer therapies also affect benign cells and can disrupt the normal function and physiology of tissues and organs. To avoid host lethality, most anticancer regimens do not rely on single overwhelming treatment doses: both radiation and chemotherapy are administered at intervals to allow the recovery of vital normal cell types. However, gaps between treatment cycles also allow tumor cells to recover, activate and exploit survival mechanisms and resist subsequent therapeutic insults.

Here we tested the hypothesis that treatment-associated DNA damage responses in benign cells comprising the tumor microenvironment promote therapy resistance and subsequent tumor progression. We provide in vivo evidence of treatment-induced alterations in tumor stroma that include the expression of a diverse spectrum of secreted cytokines and growth factors. Among these, we show that WNT16B is activated in fibroblasts through NF-κB and promotes an epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) in neoplastic prostate epithelium through paracrine signaling. Further, WNT16B, acting in a cell nonautonomous manner, promotes the survival of cancer cells after cytotoxic therapy. We conclude that approaches targeting constituents of the tumor microenvironment in conjunction with conventional cancer therapeutics may enhance treatment responses.

RESULTS

Therapy induces damage responses in tumor microenvironments

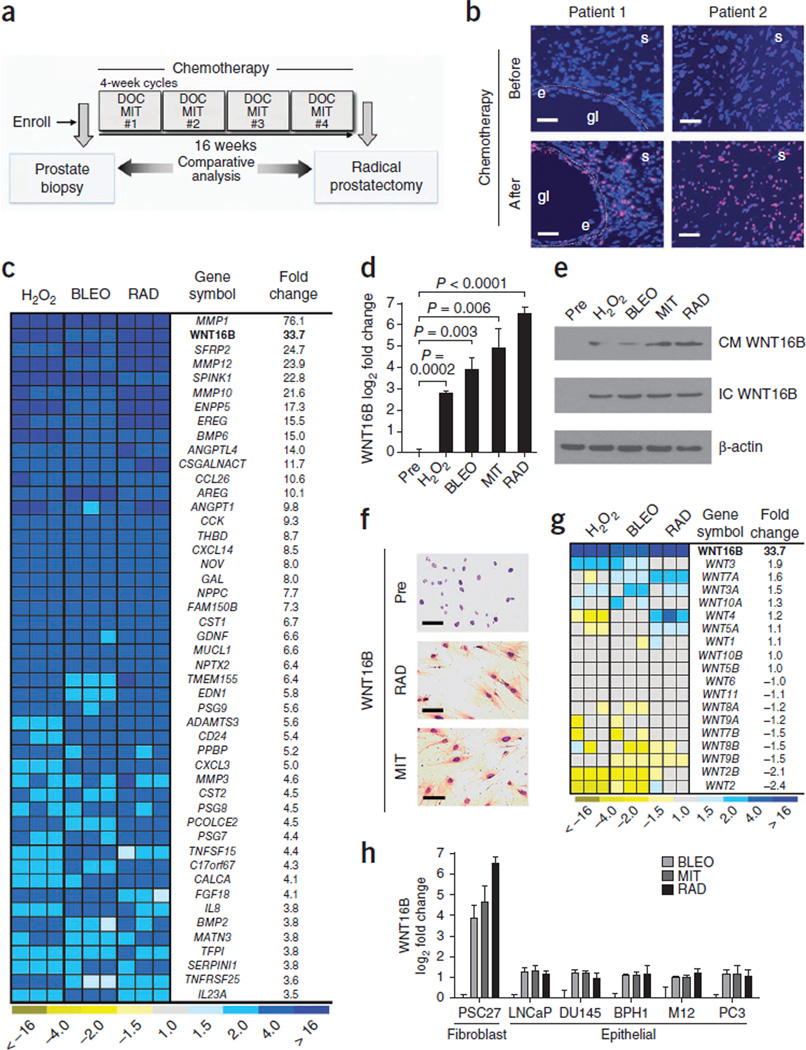

To assess for treatment-induced damage responses in benign cells comprising the tumor microenvironment, we examined tissues collected before and after chemotherapy exposure in men with prostate cancer enrolled in a neoadjuvant clinical trial combining the genotoxic drug mitoxantrone (MIT) and the microtubule poison docetaxel (DOC) (Fig. 1a)17,18. After chemotherapy, we found evidence of DNA damage in fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells comprising the prostate stroma, as determined by the phosphorylation of histone H2AX on Ser139 (γ-H2AX) (Fig. 1b). To ascertain the molecular consequences of DNA damage in benign cells, we treated primary prostate fibroblasts (PSC27 cells) with MIT, bleomycin (BLEO), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) or gamma radiation (RAD), each of which substantially increased the number of γ-H2AX foci (Supplementary Fig. 1a,b). We used whole-genome microarrays to quantify transcripts in PSC27 cells and determined that the levels of 727 and 329 mRNAs were commonly increased and decreased, respectively (false discovery rate of 0.1%), as a result of these genotoxic exposures (Supplementary Fig. 1c). To focus our studies on those factors with the clear potential for paracrine effects on tumor cells, we evaluated genes with at least 3.5-fold elevated expression after genotoxic treatments that encode extracellular proteins, here collectively termed the DNA damage secretory program (DDSP) (Fig. 1c). Consistent with previous studies, transcripts encoding matrix metalloproteinases such as MMP1, chemokines such as CXCL3 and peptide growth factors such as amphiregulin were substantially elevated in PSC27 fibroblasts after genotoxic damage19,20. Notably, the expression of WNT16B increased between eightfold and 64-fold as a result of these treatments (P < 0.005) (Fig. 1c,d).

Figure 1.

Genotoxic damage to primary prostate fibroblasts induces expression of a spectrum of secreted proteins that includes WNT16B. (a) Schematic of the prostate cancer treatment regimen comprising a pretreatment prostate biopsy and four cycles of neoadjuvant DOC and MIT chemotherapy followed by radical prostatectomy. (b) DNA damage foci in human prostate tissues collected before and after chemotherapy. Tissue sections were probed with antibodies recognizing γ-H2AX (red and pink signals), and nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). Gl, gland lumen; e, epithelium; s, stroma. Scale bars, 50 µm. (c) Analysis of gene expression changes in prostate fibroblasts by transcript microarray quantification. The heatmap depicts the relative mRNA levels after exposure to H2O2, BLEO or RAD compared to vehicle-treated cells. Columns are replicate experiments. WNT16B is highlighted in bold for emphasis. (d) Measurements of WNT16B expression by qRT-PCR in prostate fibroblasts. Shown are the log2 transcript measurements before (Pre) or after exposure to the indicated factors relative to vehicle-treated control cells. Data are mean ± s.e.m. of triplicates. The P value was calculated by analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by t test. (e) WNT16B protein expression in prostate PSC27 fibroblast extracellular conditioned medium (CM) or in cell lysates (IC) after genotoxic exposures. β-actin is a loading control. (f) Immunohistochemical analysis of WNT16B expression in prostate fibroblasts before (Pre) and after exposure to MIT or RAD. Brown chromogen indicates WNT16B expression. Scale bars, 50 µm. (g) Expression of Wnt family members in prostate fibroblasts after exposure to DNA-damaging agents. Transcript quantification was determined by microarray hybridization. Columns represent independent replicate experiments. WNT16B is listed in bold for emphasis. (h) WNT16B expression by qRT-PCR in PSC27 fibroblasts and prostate cancer cell lines after the indicated genotoxic exposure relative to pretreatment transcript amounts. Data are mean ± s.e.m.

Wnt family members participate in well-described mesenchymal and epithelial signaling events that span developmental biology, stem cell functions and neoplasia21. Though little information links Wnt signaling to DNA damage responses, a previous study reported WNT16B overexpression in the context of stress- and oncogene-induced senescence22. We confirmed that DNA damage increased WNT16B protein expression and found elevated amounts of extracellular WNT16B in conditioned medium from prostate fibroblasts after chemotherapy or radiation (Fig. 1e,f). Transcripts encoding other Wnt family members were not substantially altered in the prostate fibroblasts we studied here (Fig. 1g). In contrast to the WNT16B responses in fibroblasts, we observed little induction of WNT16B expression in epithelial cells (Fig. 1h).

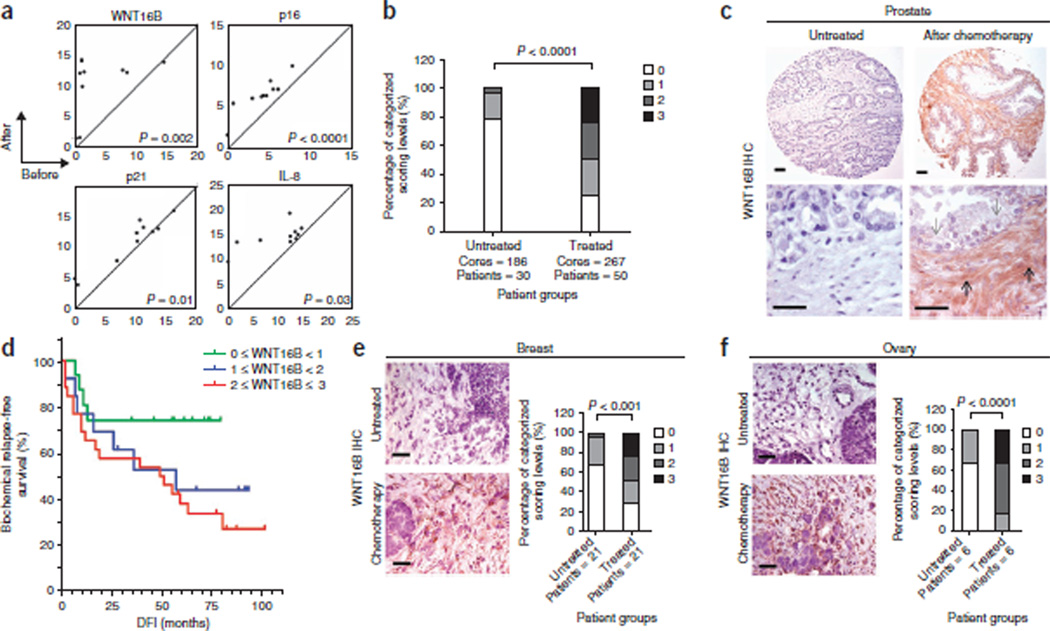

We next sought to confirm that expression of WNT16B is induced by genotoxic therapy in vivo. We used laser-capture microdissection to separately isolate stroma and epithelium and determined by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) that the number of WNT16B transcripts increased by approximately sixfold in prostate stroma after chemotherapy (P < 0.01) (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 1d). The expression of other genes known to respond to DNA damage, including CDKN2A (also known as p16), CDKN1A (also known as p21) and IL8, also increased in response to chemotherapy in prostate stroma (Fig. 2a)20,23. We next confirmed induction of WNT16B protein expression by immunohistochemistry. Compared to untreated prostate tissue, WNT16B protein was substantially and significantly increased after chemotherapy in the periglandular stroma, which included fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells (P < 0.01) (Fig. 2b,c). In contrast, we observed very limited WNT16B expression in benign or neoplastic epithelium, and mRNAs encoding other Wnt family proteins were not substantially altered in prostate stroma (Supplementary Fig. 1d,e).

Figure 2.

Cytotoxic chemotherapy induces WNT16B expression in the tumor microenvironment. (a) Chemotherapy-induced gene expression changes in human prostate-cancer–associated stroma measured by qRT-PCR of microdissected cells. The amounts of transcript before treatment (x axis) are plotted against the amounts of transcript after chemotherapy (y axis) from the same individual. Each data point represents the measurements from an individual patient. The results are shown as PCR cycle number relative to ribosomal protein L13 (RPL13), which served as the reference control. The P values were calculated by Student’s t test. (b) IHC assessment of prostate stromal WNT16B expression in prostatectomy tissue samples from men with prostate cancer who were either untreated (n = 30) or treated with chemotherapy (n = 50). Patients were assigned to four categories based on their stromal WNT16B staining: 0, no expression; 1, faint or equivocal expression; 2, moderate expression; 3, intense reactivity. P < 0.0001 by ANOVA. (c) Representative example of intense WNT16B expression in prostate stroma after in vivo exposure to MIT and DOC. The black arrows denote areas of the stroma with fibroblasts and smooth muscle. Note the minimal WNT16B reactivity in the epithelium (gray arrows). Scale bars, 50 µm. (d) Kaplan-Meier plot of biochemical (prostate-specific antigen) relapse-free survival based on the expression of WNT16B in prostate stroma after exposure to MIT and DOC chemotherapy (P = 0.04 by log-rank test comparing WNT16B < 1 with WNT16B ≥ 2 survival distributions). DFI, disease-free interval from surgery. (e,f) WNT16B staining of breast (e) and ovarian (f) carcinoma from patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy or no treatment before surgical resection. Staining is recorded on a 4-point scale: 0, no expression; 1, faint or equivocal expression; 2, moderate expression; 3, intense reactivity. Scale bars, 50 µm. The P values were calculated by ANOVA.

We confirmed these findings in breast and ovarian carcinomas, two other malignancies commonly treated with cytotoxic chemotherapy. Genotoxic treatments induced the expression of WNT16B protein in primary human fibroblasts isolated directly from breast and ovarian tissues and in the prostates, breasts and ovaries of mice treated with MIT (Supplementary Fig. 2a–d). WNT16B protein expression was significantly elevated in the stroma of human breast and ovarian cancers treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy compared with tumors from patients that did not receive treatment (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2). Notably, in each of the tumor types evaluated, a range of absent to robust WNT16B expression was evident. Because responses to chemotherapy also varied, we evaluated whether WNT16B expression was associated with clinical outcome. In patients with prostate cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, higher WNT16B immunoreactivity in prostate stroma after treatment was associated with a significantly greater likelihood of cancer recurrence (P = 0.04) (Fig. 2d). We next sought to determine the mechanism(s) by which WNT16B could contribute to treatment failure.

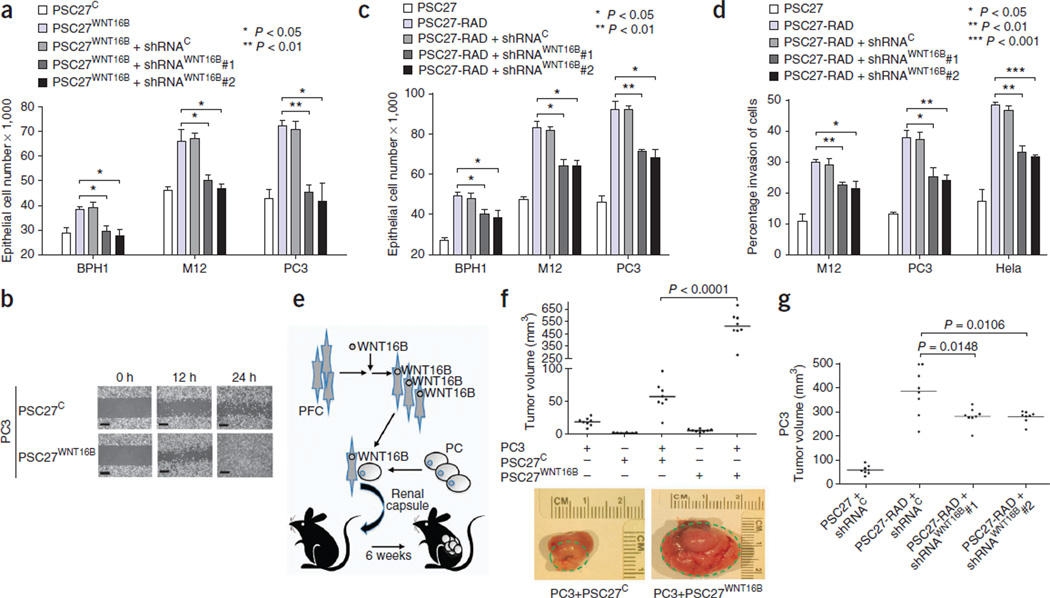

WNT16B promotes cancer cell proliferation and invasion

Members of the Wnt family influence cellular phenotypes through β-catenin–dependent and –independent pathways21. We generated a prostate fibroblast cell strain with stable expression of WNT16B (PSC27WNT16B) and fibroblast strains that expressed shRNAs specific to WNT16B (shRNAWNT16B), which blocked the induction of WNT16B expression by RAD and MIT (Supplementary Fig. 3a,b). PSC27WNT16B-conditioned medium significantly enhanced prostate cancer cell growth (P < 0.01) (Fig. 3a) and increased cellular migration and invasion (P < 0.05) compared to conditioned medium from PSC27 vector controls (PSC27C) (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 3c,d), confirming that WNT16B can promote phenotypic changes in tumor cells through paracrine mechanisms.

Figure 3.

WNT16B is a major effector of the full DDSP and promotes the growth and invasion of prostate carcinoma. (a) Conditioned medium from WNT16B-expressing prostate fibroblasts (PSC27WNT16B) promotes the proliferation of neoplastic prostate epithelial cells. shRNAC, control shRNA; shRNAWNT16B#1 and shRNAWNT16B#2, WNT16B-specific shRNAs. (b) Scratch assay showing the enhanced motility of PC3 cells exposed to conditioned medium from prostate fibroblasts expressing a control vector (PSC27C) or fibroblasts expressing WNT16B (PSC27WNT16B). Scale bars, 100 µm. (c) The full fibroblast DDSP induced by radiation (PSC27-RAD) promotes the proliferation of tumorigenic prostate epithelial cells. The proliferative effect is significantly attenuated by the suppression of damage-induced expression of WNT16B (PSC27-RAD+shRNAWNT16B). (d) The full paracrine-acting fibroblast DDSP induced by radiation (PSC27-RAD) promotes the invasion of neoplastic epithelial cells. Invasion is significantly attenuated by the suppression of damage-induced expression of WNT16B (PSC27-RAD+shRNAWNT16B). Data in a, c and d are mean ± s.e.m. of triplicates, with P values calculated by ANOVA followed by t test. (e) Schematic of the xenograft cell recombination experiment to assess the ability of fibroblasts expressing WNT16B to influence prostate tumorigenesis in vivo. PFC, prostate fibroblast cells; PC, prostate cancer cells. (f) Prostate fibroblasts engineered to express WNT16B promote the growth of prostate carcinoma in vivo. Subrenal capsule grafts comprised of PC3 prostate epithelial cells alone, PC3 cells in combination with PSC27C control fibroblasts or PC3 cells in combination with PSC27WNT16B fibroblasts are shown. The green dashed lines denote the size of the tumor outgrowth from the kidney capsule. (g) Irradiated prostate fibroblasts (PSC27-RAD) promote the growth of prostate carcinoma cells in vivo, and this effect is significantly attenuated by the suppression of fibroblast WNT16B using WNT16B-specific shRNAs (PSC27-RAD+shRNAWNT16B) (P < 0.05). Shown are tumor volumes 8 weeks after renal capsule implantation of PC3 and PSC27 cell grafts. In f and g, horizontal lines denote the mean of each group of eight tumors, and P values were determined by ANOVA followed by t test.

The DDSP comprises a diverse spectrum of secreted proteins with the potential to alter the phenotypes of neighboring cells (Fig. 1c). We next sought to determine to what extent WNT16B is responsible for such effects in the context of the amalgam of factors induced by DNA damage. Conditioned medium from irradiated PSC27 fibroblasts (PSC27-RAD), representing the full DDSP, increased the proliferation (between 1.5-fold and twofold, P < 0.05) and invasiveness (between threefold and fourfold, P < 0.05) of neoplastic epithelial cells compared to conditioned medium from untreated PSC27 fibroblasts (Fig. 3c,d). Compared to irradiated PSC27 cells expressing control shRNAs, conditioned medium from PSC27-RAD + shRNAWNT16B fibroblasts reduced these responses to the full DDSP by between 15% and 35%, depending on the cell line (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3c,d).

To investigate the in vivo consequences of WNT16B expression in the tumor microenvironment, we combined nontumorigenic BPH1 or tumorigenic PC3 cells with PSC27WNT16B (BPH1+PSC27WNT16B and PC3+PSC27WNT16B, respectively) or control PSC27 (BPH1+PSC27C and PC3+PSC27C, respectively) fibroblasts and implanted the recombinants under the renal capsule of recipient mice (Fig. 3e). At 8 weeks after implantation, BPH1+PSC27WNT16B grafts were larger than BPH1+PSC27C grafts (~200 mm3 compared to ~10 mm3, respectively; P < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 3e). PC3+PSC27WNT16B recombinants generated very large poorly differentiated and invasive tumors with an average size of 500 mm3, which was substantially larger than any of the control tumors (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3f and Supplementary Fig. 3f).

In vivo, PC3 cells combined with PSC27-RAD cells expressing the full fibroblast DDSP resulted in substantially larger tumors than PC3 cells combined with untreated PSC27 control fibroblasts (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3g). Reducing the fibroblast contribution of WNT16B attenuated the PSC27-RAD effects: grafts of PC3+PSC27-RAD averaged 380 mm3, whereas PC3 cells combined with PSC27-RAD+shRNAWNT16B averaged 280 mm3, a ~25% reduction in tumor size when fibroblast WNT16B was suppressed (P < 0.02) (Fig. 3g). Taken together, these findings show that paracrine WNT16B activity can promote tumor growth in vivo and accounts for a substantial component of the full DDSP effect on neoplastic epithelium.

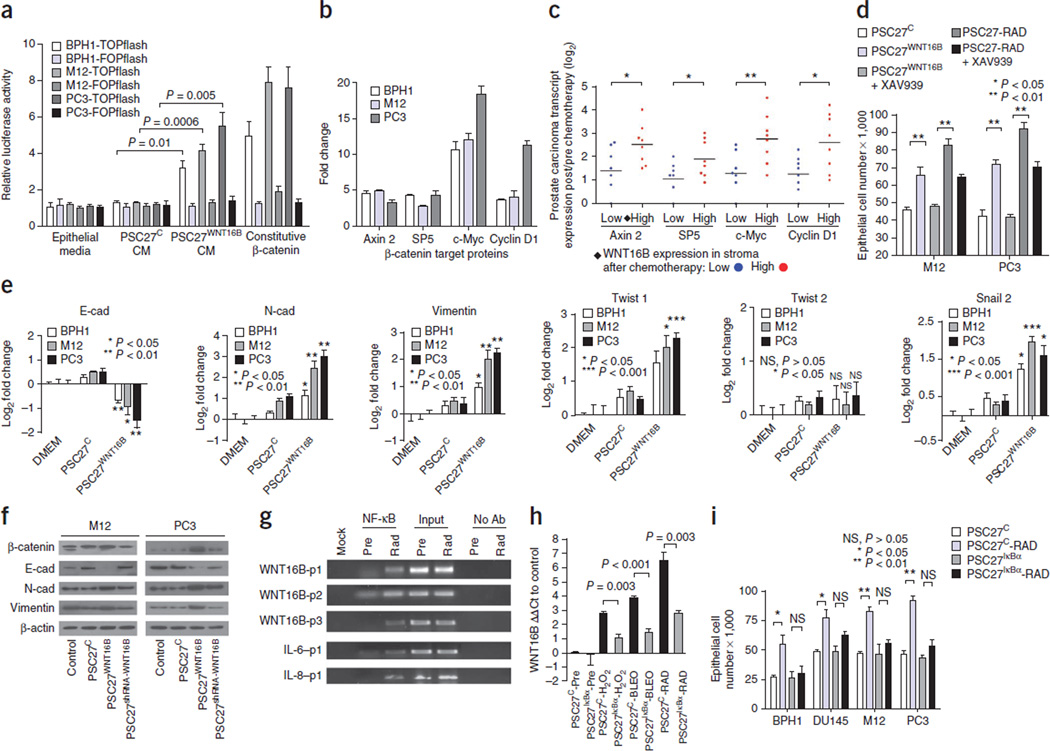

WNT16B signals through β-catenin and induces an EMT

Having established that WNT16B can promote tumor growth through paracrine signaling, we next sought to determine the mechanism(s) by which it does so. PSC27WNT16B-conditioned medium activated canonical Wnt signaling in BPH1, PC3 and M12 prostate cancer cells, as measured by assays of β-catenin–mediated transcription through T cell factor/lymphoid enhancer binding factor (TCF/LEF) binding sites (Fig. 4a). Known β-catenin target genes, including AXIN2 and MYC, were upregulated (approximately fivefold and over tenfold, respectively) after exposure to WNT16B-enriched conditioned medium (Fig. 4b). In human prostate cancers treated with chemotherapy, β-catenin localized in the nucleus of tumor cells (Supplementary Fig. 4a). We also found that β-catenin target genes were expressed more highly in tumors with elevated stromal WNT16B expression relative to those with low WNT16B expression (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4c). To confirm that β-catenin signaling contributed to the epithelial phenotypes resulting from exposure to PSC27-RAD–conditioned medium, we treated prostate cancer cells with the tankyrase inhibitor XAV939, which stabilizes axin and inhibits β-catenin–mediated transcription24. XAV939 completely suppressed the proliferative and invasive responses induced by WNT16B and markedly attenuated the effects of the PSC27-RAD DDSP (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 4b).

Figure 4.

Genotoxic stress upregulates WNT16B through NF-κB and signals through the canonical Wnt–β-catenin pathway to promote tumor cell proliferation and the acquisition of mesenchymal characteristics. (a) Assay of canonical Wnt pathway signaling through activation of a TCF/LEF luciferase reporter construct (TOPflash) or a control reporter (FOPflash). Epithelial cells were exposed to conditioned medium (CM) from PSC27 prostate fibroblasts expressing WNT16B (PSC27WNT16B) or control vector (PSC27C). Data are mean ± s.e.m. of triplicates, and P values were determined by ANOVA followed by t test. (b) qRT-PCR assessment of the expression of β-catenin target genes in prostate cancer cell lines (BPH1, M12 and PC3) before and 72 h after exposure to PSC27WNT16B-conditioned medium. Data represent the mean ± s.e.m. fold change after as compared to before exposure for three replicates. (c) Expression of β-catenin target genes in human prostate cancers in vivo after neoadjuvant treatment with MIT and DOC. Log2 transcript amounts in carcinoma cells after and before chemotherapy are shown in relation to low (blue) or high (red) WNT16B expression in the prostate stroma. Each data point represents an individual patient; n = 8 patients. Horizontal bars are group means. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 by ANOVA followed by t test. (d) The β-catenin pathway inhibitor XAV939 suppresses the proliferation of prostate cancer cells in response to PSC27WNT16B CM and attenuates the response to the full DDSP in PSC27-RAD–conditioned medium. Cell numbers were determined 72 h after treatment. (e) Quantification of transcripts in neoplastic prostate epithelial cells encoding proteins associated with a phenotype of EMT. Measurements are from epithelial cells exposed to control media (DMEM), media conditioned by PSC27 fibroblasts (PSC27C) or PSC27 fibroblasts expressing WNT16B (PSC27WNT16B). E-cad, E-cadherin; N-cad, N-cadherin. (f) Analysis of EMT-associated protein expression by western blot. M12 or PC3 cells were exposed to control media, media conditioned by PSC27 fibroblasts (PSC27C), PSC27 fibroblasts expressing WNT16B (PSC27WNT16B) or PSC27 fibroblasts expressing WNT16B and shRNA targeting WNT16B (PSC27shRNA-WNT16B). (g) Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays identified NF-κB binding sites within the proximal promoter of the WNT16 gene. PCR reaction products from Mock (no DNA loading), NF-κB immunoprecipitation, input control DNA and no antibody (Ab) control before treatment (Pre) and after irradiation (Rad). p1, p2 and p3 indicate primer pairs corresponding to putative NF-κB binding regions in WNT16, IL-6 and IL-8, respectively (see the Supplementary Methods for the primer sequences). (h) Analysis of WNT16B transcript expression by qRT-PCR in PSC27 prostate fibroblasts with (PSC27IκBα) or without (PSC27C) inhibition of NF-κB signaling before and after DNA-damaging exposures. (i) Inhibition of NF-κB signaling in fibroblasts responding to DNA damage attenuates the effect of the DDSP on tumor cell proliferation. Cell numbers were determined 72 h after RAD exposure to conditioned medium from fibroblasts with (PSC27IκBα) or without (PSC27C) inhibition of NF-κB signaling. Data in d, e, h and i are mean ± s.e.m. of triplicates, and P values were determined by ANOVA followed by t test.

Wnt signaling is known to promote the acquisition of mesenchymal cell characteristics that can influence the migratory and invasive behavior of epithelial cells through an EMT25–27. Loss of CDH1 (also known as E-cadherin), the prototypic epithelial adhesion molecule in adherens junctions, and gain of CDH2 (also known as N-cadherin) expression are among the main hallmarks of an EMT28,29. After exposure of PC3 cells to PSC27WNT16B-conditioned medium, the number of E-cadherin transcripts decreased 64%, whereas the number of N-cadherin transcripts increased fourfold (P < 0.05). Similar alterations occurred in M12 and BPH1 cells (Fig. 4e,f). Inhibiting β-catenin pathway signaling with XAV939 in epithelial cells blocked the WNT16B-induced EMT-associated gene expression (Supplementary Fig. 4c). Exposure to PSC27WNT16B-conditioned medium also promoted mesenchymal characteristics in MDA-MD-231 breast cancer and SKOV3 ovarian cancer cells (Supplementary Fig. 4d).

Genotoxic stress induces WNT16B expression through NF-κB

A key pathway linking DNA damage with apoptosis, senescence and DNA repair mechanisms involves activating the NF-κB complex30,31. NF-κB is also pivotal in mediating the stress-associated induction of inflammatory networks, including the upregulation and secretion of interkeukin-6 (IL-6) and IL-8 (refs. 23,32). We therefore sought to determine whether DNA-damage–induced WNT16B expression is mediated by NF-κB. We identified NF-κB binding motifs in the WNT16B promoter region and confirmed their function using WNT16B promoter constructs. Compared to untreated cells, both RAD and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), which are known NF-κB activators, induced WNT16B reporter activity (P < 0.01) (Fig. 4g and Supplementary Fig. 5a–d). We next generated PSC27 prostate fibroblasts with stable expression of a mutant nuclear factor of κ light polypeptide gene enhancer in B cells inhibitor, α (IκBα) (PSC27IκBα), which prevents IκB kinase (IKK)-dependent degradation of IκBα and thus attenuates NF-κB signaling. After irradiation of PSC27 cells, NF-κB translocated to the nucleus and induced NF-κB reporter activity >100-fold (Supplementary Fig. 5d,e). In comparison, the amount of nuclear NF-κB in PSC27IκBα-RAD cells was markedly lower. The PSC27IκBα cells with impaired NF-κB activation had a significant attenuation of induction of WNT16B expression after treatment with H2O2, BLEO or RAD (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4h).

We next determined whether suppressing fibroblast NF-κB signaling in response to DNA damage would attenuate the pro-proliferative effects of the PSC27-RAD DDSP. Whereas PSC27-RAD–conditioned medium promoted prostate epithelial cell proliferation, conditioned medium from PSC27IκBα-RAD cells failed to do so (Fig. 4i). These experiments identify WNT16B as a new member of the cellular genomic program that is regulated by NF-κB signaling in response to DNA damage.

Paracrine WNT16B attenuates the effect of cytotoxic therapy

The preceding experiments suggested that in addition to tumor-promoting effects, paracrine-acting WNT16B may influence the responses of tumors to genotoxic cancer therapeutics. To evaluate this possibility, we studied MIT, a type 2 topoisomerase inhibitor that produces DNA strand breaks, leading to growth arrest, senescence or apoptosis, which is in clinical use for the treatment of advanced prostate cancer. Prostate cancer cells exposed to PSC27WNT16B-conditioned medium compared to control medium consistently showed significant attenuation of chemotherapy-induced cytotoxicity across a range of MIT concentrations after 3 d (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 6a). Short-term cell viability assays confirmed that, compared to controls, PSC27WNT16B-conditioned medium improved cancer cell survival after acute 12-h exposures to MIT (P < 0.01) (Supplementary Fig. 6b). Apoptotic responses measured after 24 h of MIT exposure were substantially attenuated by PSC27WNT16B-conditioned medium (P < 0.01), an effect that was blocked by treatment with XAV939 (Fig. 5b,c). To determine whether these observations were of relevance to tumor therapy in vivo, we treated mice with tumor grafts comprised of PC3 cells plus PSC27WNT16B or PSC27C fibroblasts with three cycles of MIT given every other week. MIT treatment significantly reduced the tumor volumes (P < 0.001). However, grafts of tumor cells with PSC27WNT16B fibroblasts attenuated the tumor inhibitory effects of MIT compared to tumor cells grafted with control PSC27 fibroblasts: PC3+PSC27C and PC3+PSC27WNT16B tumors averaged 13 mm3 and 78 mm3, respectively (P < 0.001) (Fig. 5d). Experiments using MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells plus breast fibroblasts produced similar results (Supplementary Fig. 6c). To evaluate the influence of WNT16B on the acute effects of chemotherapy, we examined cohorts of PC3+PSC27C and PC3+PSC27WNT16B xenografts 24 h after MIT treatment to quantify DNA damage using γ-H2AX immunofluorescence and apoptosis using cleaved caspase 3 immunohistochemistry (IHC). Compared to PC3+PSC27C grafts, there was no difference in the number of DNA damage foci in PC3+PSC27WNT16B tumors, but significantly fewer apoptotic cells were present (34% compared to 14%, respectively; P < 0.05) (Fig. 5e).

Figure 5.

Paracrine-acting WNT16B promotes the resistance of prostate carcinoma to cytotoxic chemotherapy. (a) Viability of prostate cancer cells 3 d after treatment with a half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of MIT and medium conditioned by fibroblasts with (PSC27WNT16B) or without (PSC27C) WNT16B. (b) Bright field microscopic view of PC3 cells cultured with control or PSC27WNT16B-conditioned medium photographed 24 h after exposure to vehicle or the IC50 of MIT. Arrowheads denote apoptotic cell bodies. Scale bars, 50 µm. (c) Acute tumor cell responses to chemotherapy in vitro. Quantification of apoptosis by assays reflecting combined caspase 3 and 7 activity measured 24 h after the exposure of PC3 cells to vehicle or the IC50 of MIT. Data in a and c are mean ± s.e.m. of triplicate experiments, and P values were determined by ANOVA followed by t test. RLU, relative luciferase unit. (d) In vivo responses of PC3 tumors to MIT chemotherapy. Grafts were comprised of PC3 cells alone or PC3 cells combined with either PSC27 prostate fibroblasts expressing a control vector (PC3+PSC27C) or PSC27 prostate fibroblasts expressing WNT16B (PC3+PSC27WNT16B). MIT was administered every 2 weeks for three cycles, and grafts were harvested and tumor volumes determined 1 week after the final MIT treatment. Each data point represents an individual xenograft. Horizontal lines are group means of ten tumors, with P values determined by ANOVA followed by t test. (e) Acute tumor cell responses to chemotherapy in vivo. Quantification of apoptosis by cleaved caspase 3 (C-caspase 3) IHC and of DNA damage by γ-H2AX immunofluorescence in PC3 and fibroblast xenografts measured 24 h after in vivo treatment with vehicle (C) or MIT. Values represent a minimum of 100 cells counted from each of 3–5 tumors per group. Data are mean ± s.e.m., and P values were determined by ANOVA followed by t test.

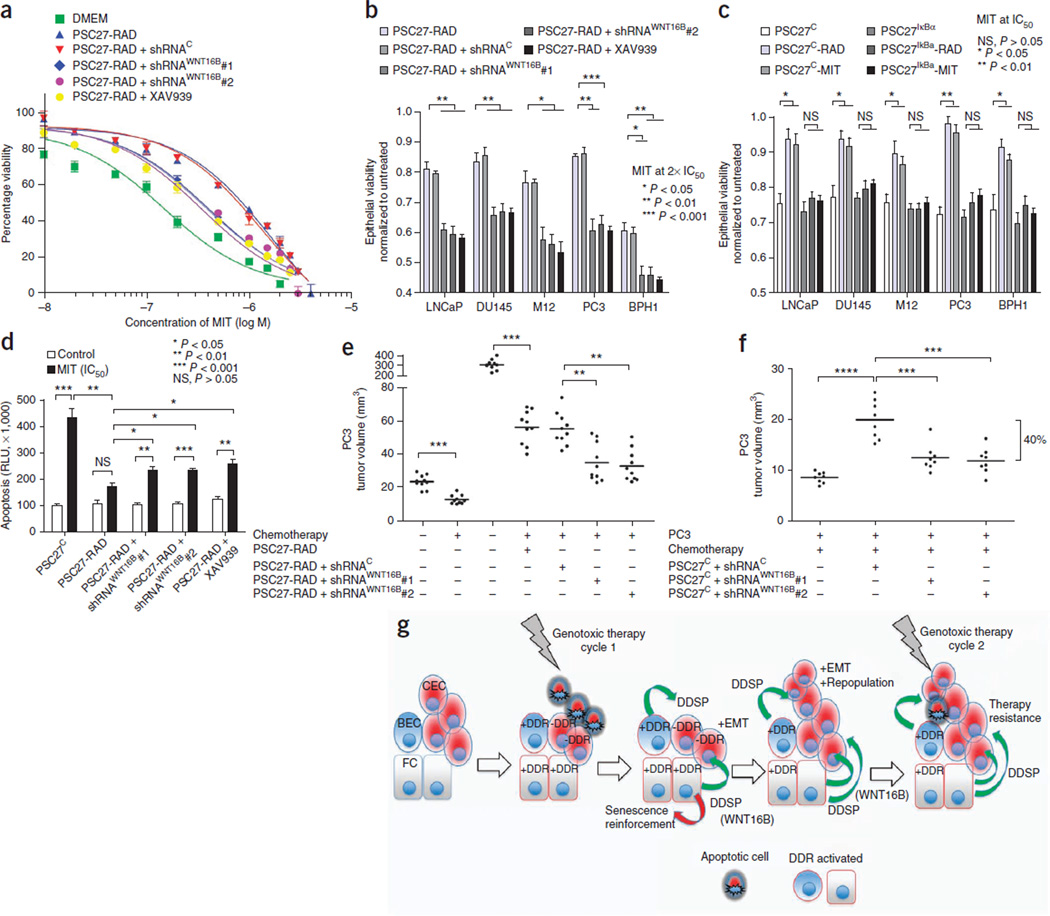

The conditioned medium from PSC27-RAD cells, representing the full fibroblast DDSP, significantly increased the viability of PC3 cancer cells exposed to MIT concentrations ranging between 0.1–1 µM in vitro (P < 0.01) (Fig. 6a). In comparison to PSC27-RAD–conditioned medium, PSC27-RAD+shRNAWNT16B or PSC27IκBαRAD fibroblasts, engineered to suppress WNT16B expression or NF-κB activation, respectively, substantially augmented the effects of MIT, further increasing apoptosis and reducing tumor cell viability by 30–40%. Blocking β-catenin signaling in carcinoma cells with XAV939 also attenuated the effects of PSC27-RAD–conditioned medium on promoting tumor cell survival (Fig. 6b–d and Supplementary Fig. 7a,b). This effect of WNT16B was also evident in vivo. PC3+PSC27-RAD tumor grafts averaged 300 mm3 in size compared to 25 mm3 for grafts of PC3 cells alone (P < 0.001). MIT chemotherapy suppressed the growth of the PC3+PSC27-RAD grafts, though residual tumors were still readily detectable and averaged 55 mm3 in size (Fig. 6e). However, after MIT treatment, residual tumors of PC3 cells with PSC27-RAD + shRNAWNT16B fibroblasts, with attenuated WNT16B induction, were on average ~33% smaller than PC3+PSC27-RAD tumors (P < 0.001) (Fig. 6e). Experiments with MDA-MD-231 cells and breast fibroblasts produced similar results (Supplementary Fig. 7c). To more accurately mimic the clinical situation of cancer therapy, we also grafted tumor cells with unirradiated PSC27 fibroblasts (PSC27C) and followed the same treatment schema of three MIT cycles. Tumors from mice treated with MIT were substantially smaller than tumors from untreated mice (P < 0.001). Attenuating the induction of WNT16B further enhanced the effects of chemotherapy: after MIT treatment, grafts of PC3 cells and PSC27C + shRNAWNT16B were on average 40% smaller than grafts of PC3 cells combined with PSC27C cells without shRNAWNT16B (P < 0.001) (Fig. 6f and Supplementary Fig. 7d).

Figure 6.

Chemotherapy resistance promoted by damaged fibroblasts is attenuated by blocking WNT16B, β-catenin or NF-κB signaling. (a) Viability of prostate cancer cells across a range of MIT concentrations with (PSC27-RAD+shRNAWNT16B) or without (PSC27-RAD+shRNAC) the suppression of WNT16B in irradiated-fibroblast–conditioned medium or with the addition of the β-catenin pathway inhibitor XAV939. Data are mean ± s.e.m. of triplicates. (b) Viability of prostate cancer cells 3 d after treatment with two times the IC50 of MIT in the context of conditioned medium from irradiated prostate fibroblasts (PSC27-RAD) expressing shRNAs targeting and suppressing WNT16B (shRNAWNT16B), a vector control (shRNAC) or combined with the β-catenin pathway inhibitor XAV939. (c) Viability of prostate cancer cells 3 d after treatment with the IC50 of MIT in the context of conditioned medium from prostate fibroblasts pretreated with radiation (PSC27-RAD) or MIT (PSC27-MIT) and with (PSC27IκBα) or without (PSC27C) the suppression of NF-κB signaling. (d) Acute tumor cell responses to chemotherapy in vitro. Quantification of apoptosis by caspase 3 and 7 activity measured 24 h after the exposure of PC3 cells to vehicle or the IC50 of MIT. Data for b, c and d are mean ± s.e.m. of triplicates, and P values were determined by ANOVA followed by t test. (e,f) In vivo effects of MIT chemotherapy in the context of suppressing the induction of the expression of fibroblast WNT16B. Tumors comprised PC3 cells in combination with irradiated (PSC27-RAD) fibroblasts (e) or unirradiated (PSC27C) (f) prostate fibroblasts expressing shRNAs targeting WNT16B (shRNAWNT16B) or a vector control (shRNAC). MIT was administered every 2 weeks for three cycles, and grafts were harvested and tumor volumes determined 1 week after the final treatment. Each data point represents an individual xenograft. Tumor volumes of PSC27C+shRNAC grafts in f averaged 20 mm3, and tumor volumes of PSC27C+shRNAWNT16B grafts averaged 12 mm3 (P < 0.001). Horizontal lines are group means, with n = 10 in e and n = 8 in f. P values were determined by ANOVA followed by t test. The bracket boundaries in f are the group means for PSC27C+shRNAC grafts compared to PSC27C+shRNAWNT16B grafts showing a 40% difference in size. Asterisks, as for the previous panel. (g) Model for cell nonautonomous therapy-resistance effects originating in the tumor microenvironment in response to genotoxic cancer therapeutics. The initial round of therapy engages an apoptotic or senescence response in subsets of tumor cells and activates a DNA damage response (DDR) in DDR-competent benign cells (+DDR) comprising the tumor microenvironment. The DDR includes a spectrum of autocrine- and paracrine-acting proteins that are capable of reinforcing a senescent phenotype in benign cells and promoting tumor repopulation through progrowth signaling pathways in neoplastic cells. Paracrine-acting secretory components such as WNT16B also promote resistance to subsequent cycles of cytotoxic therapy. CEC, cancer epithelial cell; BEC, benign epithelial cell; FC, fibroblast cell; –DDR, DDR-incompetent benign cells.

DISCUSSION

Optimizing radiotherapy and chemotherapy for the treatment of malignant neoplasms has relied on the iterative development and testing of models involving tumor growth dynamics, mutation rates and cell-kill kinetics. However, the most theoretically effective tumoricidal strategies must usually be tempered because of detrimental effects to the host. This reality has led to the development of regimens in which therapies are administered at intervals or cycles to avoid irreparable damage to vital host functions. However, the recovery and repopulation of tumor cells between treatment cycles is a major cause of treatment failure15,16. Interestingly, rates of tumor cell repopulation have been shown to accelerate in the intervals between successive courses of treatment, and solid tumors commonly show initial responses followed by rapid regrowth and subsequent resistance to further chemotherapy. Our results indicate that damage responses in benign cells comprising the tumor microenvironment may directly contribute to enhanced tumor growth kinetics (Fig. 6g).

The autocrine- and paracrine-acting influences of genotoxic stress responses can exert complex and potentially conflicting cell non-autonomous effects33,34. Overall, our findings are in agreement with studies of DNA damage in which the execution of a signaling program culminating in a senescence phenotype is accompanied by elevated concentrations of specific extracellular proteins termed a ‘senescence messaging secretome’ or a ‘senescence-associated secretory phenotype’33,34. DNA damage responses and senescence programs can clearly operate in a cell autonomous ‘intrinsic’ manner to arrest cell growth and inhibit tumor progression, as has been observed in premalignant nevi35. Secreted factors such as insulin-like growth factor binding protein 7 (IGFBP7) and the chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 2 (CXCR2) ligands IL-6 and IL-8 participate in a positive feedback loop to fortify the senescence growth arrest induced by oncogenic stress and also promote immune responses that clear senescent cells and enhance tumor regression23,32,36,37. However, in addition to proinflammatory cytokines, the damage response program comprises proteases and mitogenic growth factors, such as MMPs, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) ligands that have clear roles in promoting tumor growth, inhibiting cellular differentiation, enhancing angiogenesis and influencing treatment resistance19,20,38. This concept is supported by reports of tissue-specific chemoresistant survival niches involving hematopoietic neoplasms, such as lymphomas39. The situation also has parallels with studies of radiation and chemotherapy paradoxically promoting tumor dissemination40.

Collectively, these studies support several conclusions: first, the outcomes of genotoxic exposures to any specific benign or neoplastic cell depend on the integration of innate damage response capabilities and the context that is dictated by the composition of the tumor microenvironment; second, although intrinsic drug resistance is clearly operative in some cancers, acquired resistance can also occur without alterations in intrinsic cellular chemosensitivity41, and our results provide strong support for previous studies that implicate constituents of the tumor microenvironment as important contributors to this resistance42–44; and third, specific microenvironment DDSP proteins that promote therapy resistance such as WNT16B are attractive targets for augmenting responses to more general genotoxic therapeutics. However, the complexity of the damage response program also supports strategies that are focused on inhibiting upstream master regulators, such as NF-κB45, that may be more efficient and effective adjuncts to cytotoxic therapies, provided their side effects are tolerable.

ONLINE METHODS

Cell cultures and treatments

We obtained epithelial cell lines from the American Type Culture Collection and cultured them according to the recommended protocols. Fibroblasts were grown until they were 80% confluent and were then treated with 0.6 mM hydrogen peroxide (PSC27-H2O2), 10 µg ml−1 bleomycin (PSC27-BLEO), 1 µM mitoxantrone (PSC27-MIT) or ionizing radiation by a 137Cesium source at 743 rad min−1 (PSC27-RAD). Additional details of the cell culture methods are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

Gene expression analysis

We extracted total RNA from PSC27 cells using the RNeasy kit (QIAGEN), converted mRNAs to complementary DNAs (cDNAs) and amplified the cDNAs for one round using the MessageAmp aRNA Kit (Ambion), followed by aminoallyl-UTP incorporation into a second-round of amplification of the RNA. Samples were labeled with fluorescence dyes and hybridized to 44K Whole Human Genome Expression Microarray slides in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions (Agilent Technologies). Additional assays of transcript abundance were performed by qRT-PCR (Supplementary Methods).

Immunohistochemistry

We used a mouse monoclonal antibody to WNT16B (product number 552595, clone F4-1582, BD Pharmingen) at a dilution of 1:16,000 to immunolocalize WNT16B protein using an indirect three-step avidin-biotin-peroxidase method according to the manufacturer’s instructions (VECTASTAIN Elite ABC Kit, Vector Labs). The expression of WNT16B by epithelium or fibromuscular stromal cells in each tissue section was recorded on a 4-point scale as follows: 3 for intensely expressed, 2 for moderately expressed, 1 for faintly or equivocally expressed and 0 for no expression of WNT16B by any stromal cells. Additional details are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

Characterization of cell phenotypes

We assessed cell proliferation using the CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (MTS), with signals being captured using a 96-well plate reader. Serum-starved cells for transwell migration and invasion assays were added to the top chambers of Cultrex 24-well Cell Migration Assay plates (8 µm pore size) coated with or without basement membrane extract prepared as 0.5× of stock solution. After 12 h or 24 h, migrating or invading cells in the bottom chambers were stained, and the plate absorbance was recorded. Chemoresistance assays were performed using epithelial cells cultured with either DMEM and low serum (0.5% FCS) (denoted here as ‘DMEM’) or conditioned medium generated from PSC27 cells expressing vector controls, WNT16B or shRNAs. Cells received mitoxantrone treatment for 12 h, 24 h or 72 h at concentrations near the IC50 of each individual cell line. The percentage of viable cells was calculated by comparing the results of each experiment to the results from vehicle-treated cells. Each assay was repeated a minimum of three times, with results reported as means ± s.e.m.

In vivo studies

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center reviewed and approved the animal protocols and procedures, with surgeries carried out per the US National Institutes of Health Guide for laboratory animals. To prepare tissue recombinants, 250,000 fibroblasts (PSC27 series) and epithelial cells were mixed at a 1:1 ratio in collagen gels. ICR–severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) male mice, obtained from Taconic, Inc, were anesthetized with isoflurane, and an oblique incision (<1 cm) was made on the kidney capsule surface parallel and adjacent to the long axis of each kidney. Cells were injected under the capsule with a blunt 25-gauge needle and a glass Hamilton syringe. The kidney was returned to the retroperitoneal space, and the skin was closed with surgical staples. The growth of the xenografts was assessed at weekly intervals, and the mice were killed at 8 weeks after transplantation. Each xenograft arm comprised 5–8 mice per xenograft type, either of individual cells or combinations of fibroblasts and epithelial cells. Additional details are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

For the chemotherapy studies, mice received cell grafts as described above and were followed for 2 weeks to allow tumor take. Starting from the third week after grafting, mice received mitoxantrone at a dose of 0.2 mg per kg intraperitoneally on day 1 of week 3, week 5 and week 7 (ref. 46). In total, three 2-week cycles were given, after which the mice were killed and their kidneys were removed for tumor measurements and histological analysis. Each experimental arm comprised 5–8 mice per treatment cohort. Additional details are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

Statistical analyses

All in vitro experiments were repeated at least three times, and data are reported as means ± s.e.m. Differences among groups and treatments were determined by ANOVA followed by t tests. P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Additional methods

Detailed methodology is described in the Supplementary Methods.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. Dean and D. Bianchi-Frias for helpful comments, A. Moreno for administrative assistance and N. Clegg for bioinformatics support. S. Hayward, Vanderbilt University, and J. Ware, Medical College of Virginia, provided BPH1 and M12 cells, respectively. Primary human prostate (PSC27), ovarian (OVF28901) and breast (HBF1203) fibroblasts were provided by B. Knudsen, Cedars Sinai Medical Center, E. Swisher, University of Washington, and P. Porter through the Seattle Breast SPORE (P50 CA138293), Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, respectively. B. Torok-Strorb, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, provided HS5 and HS27A HPV E6/E7 immortalized human bone marrow stromal cells. We thank the clinicians who participated in the trials of neoadjuvant chemotherapy: M. Garzotto, T. Takayama, P. Lange, W. Ellis, S. Lieberman and B.A. Lowe. We are also grateful for the participation of the patients and their families in these studies. Breast cancer specimens were obtained from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/University of Washington Medical Center Breast Specimen Repository. We thank N. Urban, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, for providing ovarian cancer biospecimens funded through the POCRC SPORE grant P50CA83636. This work was supported by a fellowship from the Department of Defense (PC073217), R01CA119125, the National Cancer Institute Tumor Microenvironment Network U54126540, the Pacific Northwest Prostate Cancer SPORE P50CA097186 and the Prostate Cancer Foundation.

Footnotes

Accession codes. Microarray data are deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database with accession code GSE26143.

Note: Supplementary information is available in the online version of the paper.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Y.S. designed and conducted experiments, and wrote the manuscript. J.C. provided reagents and technical advice. C.H., T.M.B. and P.P. provided clinical materials for the assessments of treatment responses. I.C. analyzed data. L.T. analyzed tissue histology and immunohistochemical assays. P.S.N. designed experiments, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Longley DB, Johnston PG. Molecular mechanisms of drug resistance. J. Pathol. 2005;205:275–292. doi: 10.1002/path.1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang TL, et al. Digital karyotyping identifies thymidylate synthase amplification as a mechanism of resistance to 5-fluorouracil in metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:3089–3094. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308716101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmitt CA, Rosenthal CT, Lowe SW. Genetic analysis of chemoresistance in primary murine lymphomas. Nat. Med. 2000;6:1029–1035. doi: 10.1038/79542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Helmrich A, et al. Recurrent chromosomal aberrations in INK4a/ARF defective primary lymphomas predict drug responses in vivo. Oncogene. 2005;24:4174–4182. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Redmond KM, Wilson TR, Johnston PG, Longley DB. Resistance mechanisms to cancer chemotherapy. Front. Biosci. 2008;13:5138–5154. doi: 10.2741/3070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson TR, Longley DB, Johnston PG. Chemoresistance in solid tumours. Ann. Oncol. 2006;17(suppl. 10):x315–x324. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee S, Schmitt CA. Chemotherapy response and resistance. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2003;13:90–96. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakai W, et al. Secondary mutations as a mechanism of cisplatin resistance in BRCA2-mutated cancers. Nature. 2008;451:1116–1120. doi: 10.1038/nature06633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kobayashi H, et al. Acquired multicellular-mediated resistance to alkylating agents in cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:3294–3298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waldman T, et al. Cell-cycle arrest versus cell death in cancer therapy. Nat. Med. 1997;3:1034–1036. doi: 10.1038/nm0997-1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samson DJ, Seidenfeld J, Ziegler K, Aronson N. Chemotherapy sensitivity and resistance assays: a systematic review. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004;22:3618–3630. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Croix BS, et al. Reversal by hyaluronidase of adhesion-dependent multicellular drug resistance in mammary carcinoma cells. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1996;88:1285–1296. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.18.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kerbel RS. Molecular and physiologic mechanisms of drug resistance in cancer: an overview. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2001;20:1–2. doi: 10.1023/a:1013129128673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang F, et al. Phenotypic reversion or death of cancer cells by altering signaling pathways in three-dimensional contexts. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1494–1503. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.19.1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim JJ, Tannock IF. Repopulation of cancer cells during therapy: an important cause of treatment failure. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2005;5:516–525. doi: 10.1038/nrc1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trédan O, Galmarini CM, Patel K, Tannock IF. Drug resistance and the solid tumor microenvironment. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1441–1454. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garzotto M, Myrthue A, Higano CS, Beer TM. Neoadjuvant mitoxantrone and docetaxel for high-risk localized prostate cancer. Urol. Oncol. 2006;24:254–259. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2005.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beer TM, et al. Phase I study of weekly mitoxantrone and docetaxel before prostatectomy in patients with high-risk localized prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004;10:1306–1311. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-1021-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bavik C, et al. The gene expression program of prostate fibroblast senescence modulates neoplastic epithelial cell proliferation through paracrine mechanisms. Cancer Res. 2006;66:794–802. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coppé JP, et al. Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and the p53 tumor suppressor. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:2853–2868. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clevers H. Wnt/β-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell. 2006;127:469–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Binet R, et al. WNT16B is a new marker of cellular senescence that regulates p53 activity and the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT pathway. Cancer Res. 2009;69:9183–9191. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Acosta JC, et al. Chemokine signaling via the CXCR2 receptor reinforces senescence. Cell. 2008;133:1006–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang SM, et al. Tankyrase inhibition stabilizes axin and antagonizes Wnt signalling. Nature. 2009;461:614–620. doi: 10.1038/nature08356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY, Nieto MA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009;139:871–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yook JI, et al. A Wnt-Axin2–GSK3β cascade regulates Snail1 activity in breast cancer cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8:1398–1406. doi: 10.1038/ncb1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vincan E, Barker N. The upstream components of the Wnt signalling pathway in the dynamic EMT and MET associated with colorectal cancer progression. Clin. Exp. Metastasis. 2008;25:657–663. doi: 10.1007/s10585-008-9156-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu K, Bonavida B. The activated NF-κB–Snail–RKIP circuitry in cancer regulates both the metastatic cascade and resistance to apoptosis by cytotoxic drugs. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 2009;29:241–254. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v29.i3.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peinado H, Olmeda D, Cano A. Snail, Zeb and bHLH factors in tumour progression: an alliance against the epithelial phenotype? Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2007;7:415–428. doi: 10.1038/nrc2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bernard D, et al. Involvement of Rel/nuclear factor-κB transcription factors in keratinocyte senescence. Cancer Res. 2004;64:472–481. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berchtold CM, Wu ZH, Huang TT, Miyamoto S. Calcium-dependent regulation of NEMO nuclear export in response to genotoxic stimuli. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:497–509. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01772-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuilman T, et al. Oncogene-induced senescence relayed by an interleukin-dependent inflammatory network. Cell. 2008;133:1019–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuilman T, Peeper DS. Senescence-messaging secretome: SMS-ing cellular stress. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2009;9:81–94. doi: 10.1038/nrc2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fumagalli M, d’Adda di Fagagna F. SASPense and DDRama in cancer and ageing. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009;11:921–923. doi: 10.1038/ncb0809-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Michaloglou C, et al. BRAFE600-associated senescence-like cell cycle arrest of human naevi. Nature. 2005;436:720–724. doi: 10.1038/nature03890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xue W, et al. Senescence and tumour clearance is triggered by p53 restoration in murine liver carcinomas. Nature. 2007;445:656–660. doi: 10.1038/nature05529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wajapeyee N, Serra RW, Zhu X, Mahalingam M, Green MR. Oncogenic BRAF induces senescence and apoptosis through pathways mediated by the secreted protein IGFBP7. Cell. 2008;132:363–374. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coppé JP, Kauser K, Campisi J, Beausejour CM. Secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor by primary human fibroblasts at senescence. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:29568–29574. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603307200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gilbert LA, Hemann MT. DNA damage–mediated induction of a chemoresistant niche. Cell. 2010;143:355–366. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Biswas S, et al. Inhibition of TGF-β with neutralizing antibodies prevents radiation-induced acceleration of metastatic cancer progression. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:1305–1313. doi: 10.1172/JCI30740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davis AJ, Tannock JF. Repopulation of tumour cells between cycles of chemotherapy: a neglected factor. Lancet Oncol. 2000;1:86–93. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(00)00019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meads MB, Hazlehurst LA, Dalton WS. The bone marrow microenvironment as a tumor sanctuary and contributor to drug resistance. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008;14:2519–2526. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shree T, et al. Macrophages and cathepsin proteases blunt chemotherapeutic response in breast cancer. Genes Dev. 2011;25:2465–2479. doi: 10.1101/gad.180331.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DeNardo DG, et al. Leukocyte complexity predicts breast cancer survival and functionally regulates response to chemotherapy. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:54–67. doi: 10.1158/2159-8274.CD-10-0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chien Y, et al. Control of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype by NF-κB promotes senescence and enhances chemosensitivity. Genes Dev. 2011;25:2125–2136. doi: 10.1101/gad.17276711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alderton PM, Gross J, Green MD. Comparative study of doxorubicin, mitoxantrone, and epirubicin in combination with ICRF-187 (ADR-529) in a chronic cardiotoxicity animal model. Cancer Res. 1992;52:194–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.