Abstract

Recent advances have improved our understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The development of high-throughput technologies able to simultaneously investigate thousands of genes (SNP-array, gene expression microarray, etc.) has opened a new era in translational research. However, obtaining a molecular classification of HCC remains a striking challenge. Different investigators attempted to classify patients according to their liver cancer molecular background, a feature that will path the way for trial enrichment and personalized medicine. Currently, HCC can be classified in molecular classes according to Wnt-βcatenin pathway activation, proliferation signature activation (associated with chromosomal instability), and other subgroups. In parallel, the first-time ever positive results of a phase III trial in advanced HCC with the multikinase inhibitor sorafenib have encouraged this approach. The current review summarizes the molecular classifications of HCC reported, analyzes the status of targeted therapies tested in clinical trials, and evaluates feasibility of personalized medicine approaches in HCC.

Keywords: Liver cancer, genomics, signaling pathway, molecular classification, personalized medicine, molecular targeted therapies, sorafenib

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF HEPATOCELLULAR CARCINOMA

(Supongo que queries hablar de molecular epidemiology of HCC, pero no hay nada)

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the leading cause of death among cirrhotic patients, and it has become a global health problem1. Based on recent estimations, close to 625,000 new cases of HCC will be diagnosed worldwide every year. HCC mortality ranks third among all cancers, only behind lung and colon cancer2,3. Incidence rates of HCC have been closely related to viral hepatitis. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is the main risk factor for HCC in Eastern Asia and Africa4,5. Accordingly, population-based studies of massive hepatitis B vaccination have shown robust decreases in HCC incidence6. Several studies have shown that aflatoxin B exposure has a synergistic effect with HBV infection for the development of HCC. In Western countries and Japan, hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is still the main risk factor7.

Prognosis of HCC is dreadful. Less than 40% of patients are eligible for potential curative treatments, and systemic therapies such as standard chemotherapeutic agents are not efficacious in HCC based on randomized trials8–10. Hence, new therapeutic approaches are urgently needed. Also, with the advent of surveillance programs, the scientific community has experienced a switch in the type of tumors detected, and the medical interventions potentially effective for them. It is hoped that in clarifying the genomics and signaling pathways implicated in hepatocarcinogenesis, new therapeutic targets will be developed.

HCC is a very complex tumor from a molecular perspective11. Unlike most human malignancies, HCC usually develops in the context of inflammation and organ injury. This fact, added to the number of different etiologies responsible for liver damage (e.g. viral hepatitis, alcohol, etc.), warrants high molecular variability and precludes any simplistic approach. For this reason, it is relevant to figure out which are the predominant molecular mechanisms for a given HCC so that its selective and effective blockade will result in the control of the disease (personalized medicine)12. This concept comprises the study of patients as biologic individuals, allowing customization of medical interventions according to their unique genomic background.

The complexity of the human genome is far beyond what was expected after its complete decoding in the early 2000´s. New confounding factors such as alternative splicing, mRNA stability, epigenetic gene silencing, etc, have increased the output diversity after DNA transcription. Unexpectedly, since the accomplishment of the Human Genome Project, there have not been major research breakthroughs with substantial clinical implications. Also, less than 10% of published associations between DNA alterations and disease have been validated by independent researchers13. Association studies require notable numbers of patients so that small changes in DNA with implications in cancer development can be detected. These drawbacks have diminished the early enthusiastic predictions about the clinical achievements after implementation of personalized medicine. Nevertheless, certain landmark studies leave plenty of room for optimism (i.e. prophylactic surgery in women with BRCA1/2 mutations14, selective response to tyrosine kinase inhibitors in patients with lung cancer and EGFR amplifications15, etc.).

Herein, we review the current status and feasibility of personalized approaches for the treatment of HCC. For that purpose, we will first summarize the molecular classifications proposed for HCC; and second, we will evaluate present and future of molecular target therapies for this neoplasm.

(que tiene que ver este titulo con el texto?)

In most human malignancies, clinical classifications are essential for prognosis assessment and treatment planning. Also, they are useful to unify criteria and allow unbiased comparisons between groups of patients within research protocols. In the last decade, and parallel to advances in molecular oncology, genomic parameters have been progressively included in cancer classifications16. Unlike traditional clinical information (i.e. tumor size, presence of vascular or lymph node invasion, etc.), molecular data accounts for the biological background of the neoplasm. This is two-fold relevant; first, the type and quantity of molecular aberrations in a tumor might be surrogates of clinical aggressiveness. Some examples are summarized in Table 1. Secondly, molecular aberrations may represent new targets for drug development. For example, HER2/Neu amplifications in breast cancer and EGFR overexpression/mutations in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) identify a subgroup of patients with better response to trastuzumab and in some instances erlotinib, respectively17,18. As a result, tailored therapeutic regimes based on molecular data are progressively being introduced in clinical routine (Table 2).

Table 1.

Diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in human malignancies.

| Author | Molecular Alteration | Method | Type of Marker | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ithier G64 | BRCA1 mutation | DNA sequencing | Diagnostic | High risk for development breast cancer |

| Powell SM65,66 | APC mutation | DNA sequencing | Diagnostic | High risk for development of colon cancer |

| Lips CJ67 | RET mutation | DNA sequencing | Diagnostic | High risk for development of medullary thyroid cancer |

| Berwick M68 | CDKN2A mutation | DNA sequencing | Diagnostic | High risk for development of melanoma |

| Llovet JM69 | 3-gene signature (Glypican-3, LYVE1, Survivin) | Real-Time PCR (RT-PCR) | Diagnostic | Molecular diagnosis of early HCC (accuracy rates: 85–95%) |

| Robinson HM70, Radich J71 | Translocation t(9;22) | Fluorescence In Situ Hybridisation (FISH). RT-PCR for Bcr-Abl fusion transcript. Sequencing | Diagnostic and Prognostic | Marker of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and prognostic of high risk for relapse after bone marrow transplantation |

| Hurd DD72 | Translocation t(15;17) | FISH. RT-PCR for PML-RARA fusion transcript. Sequencing | Prognostic | Favorable outcome of patients affected of promyelocytic leukemia |

| Kenny FS73 | Cyclin D1 overexpression | Northern Blotting. IHC | Prognostic | Earlier relapse and shorter overall survival of ER+ breast cancer patients |

| Huncharek M74, Slebos RJ75 | K-Ras mutation | Sequencing | Prognostic | Shortened survival in NSCLC and in lung adenocarcinoma |

| Jen J76 | Loss of chromosome 18q | Microsatellite markers | Prognostic | Poor outcome in patients with stage II colorectal cancer |

| Offit K77 | Rearrangement of the bcl-6 gene | Southern Blot hybridization | Prognostic | Favorable clinical outcome in diffuse large-cell lymphoma |

| Van de Vijver MJ78 | 70-gene signature | Microarray analysis | Prognostic | Outcome predictor in young patients with breast cancer |

| Paik S79 | 21-gene signature (recurrence score) | Reverse-transcriptase-polymerase-chain-reaction | Prognostic | Distant recurrence in tamoxifen-treated patients with node-negative, estrogen-receptor–positive breast cancer |

Table 2.

Potential biomarkers of response to molecular therapies in human cancer.

| Author | n | Tumor type | Molecular predictor of response | Drug | Response to treatment | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Breast Cancer Trialists Collaborative Group80 | 37000 (methanalysis of 55 clinical trials) | Breast | Estrogen receptor expression | Tamoxifen | Improvements in 10-year survival after 5-years treatment with Tamoxifen | First line of therapy for the treatment of ER+ breast cancer |

| Piccart-Gebhart MJ81 | 1694 (Phase III) | Breast | Amplification of HER2/Neu | Transtuzumab | Improvement of disease-free survival | Approved for treatment of metastatic HER2+ breast cancer |

| Hirsch FR82,83 | 1692 (Phase III) | NSCLC | FISH for EGFR (high copy number level) | Gefitinib | Objective response rate and TTF (time to treatment failure) | Approved for the treatment of advanced lung cancer as third-line therapy for non–small-cell lung cancer |

| Tsao M15 | 427 (Phase III) | NSCLC | IHC for EGFR | Erlotinib | Improved responsiveness assessed according to the Response Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) | Approved for the treatment of advanced NSCLC |

| Sawyers CL84 | 260 (Phase II) | CML | FISH for chromosomal translocation t(9;22) | Imatinib mesylate | Hematologic responses in 52% of patients and cytogenetic responses in 16% of patients | Approved by FDA for the first-line treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia |

| Van Oosterom AT85 | 40 (Phase I) | GIST | IHC for c-Kit | Imatinib mesylate | Inhibition of tumor growth in 35 patients, 19 confirmed partial responses | Systemic therapy with Gleevec is currently approved for the treatment of c-kit-positive unresectable and metastatic GIST |

| Gordon MS86 | 123 (Phase II) | Ovarian | Enzyme-linked immunossorbent assay (ELISA) for p-HER2 | Pertuzumab | Better response rate in patients positive for p-HER2 | Phase II and III clinical trials in breast and ovarian cancers ongoing |

| Abou-Alfa GK55 | 137 (Phase II) | HCC | IHC for p-ERK | Sorafenib | Longer time to progression in p-ERK positive patients | Approved for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after phase III trial (SHARP). Molecular markers studies under development |

Golub et al. pioneered molecular cancer classification using gene expression monitoring by DNA microarrays in acute myeloid leukaemia19. In this milestone study, gene expression data were able to accurately predict cancer classes, independent of previous biological knowledge of the samples. Thereafter, several studies following the same methodology confirmed the prognostic value of gene signatures in different malignancies, including HCC20–22. Supervised and unsupervised learning methods are widely used to create gene signature profiles23. However, the application of molecular signatures as predictors of survival has been seriously criticize. Michiels24 found a worrisome rate of misclassification in 7 studies analyzed, as well as high instability in the signatures described. Five out of the seven largest published studies at that time addressing cancer prognosis using gene expression microarrays were unable to classify patients better than chance. The reasons reported for such unstable prediction were related to design issues. In a training-validation approach, the training set identifies the molecular signature and the validation set is used to estimate the degree of misclassification. In principle, Michiels recommended large sample sizes for the training sets and the use of validation by repeated random sampling. Clearly, the methodology used for data management in traditional biomedical research cannot be simply translated into this type of studies where thousands of variables are analyzed simultaneously. Thus, , initial concerns related to data processing jeopardized the valuable information provided by genome-wide expression studies.

There is no molecular classification of HCC. Several clinical staging systems have been proposed to predict HCC prognosis but only the BCLC staging system has gain wide recognition among scientific societies25–27. Still it does not incorporate biological information of the tumor. The accumulation of genetic aberrations driving cirrhotic liver to cancer appears to be a multi-step process. This transformation includes histopathological lesions that range from liver cirrhosis to dysplastic nodules (low- and high-grade), but the underground molecular mechanisms involved in this process are not fully understood. During the preneoplastic stage, there is an upregulation of mitogenic pathways leading to the selection of certain clones of dysplastic cells. These clones, organized as dysplastic nodules surrounded by fibrotic connective tissue, will acquire a malignant phenotype when exposed to different genomic alterations, including structural aberrations in chromosomes, microsatellite instability, etc11,28. It is thought that this mitogenic phenotype leads to the activation of pathways involved in pro-apoptosis and cell cycle arrest, which provide with survival benefit to dysplastic. The final step in this malignant transformation includes pathways related to angiogenesis and the capacity for migration and invasion29.

MOLECULAR CLASSIFICATION OF HCC

Considerable efforts have been made to obtain a molecular classification of HCC (Table 3). However, the overwhelming genomic complexity of HCC has rendered this goal as a major challenge. Whole-genome based analysis of DNA aberrations30,31 or gene expression32,33 have been frequently used to define molecular subgroups. These high-throughput technologies have afforded researchers a unique opportunity to integrate large amount of molecular information with clinical parameters. Unfortunately only two studies have comprehensively integrated data from different platforms31,34. These multidimensional approaches complement integrative functional genomics, a term that refers to the integrated analysis of gene expression data sets from different species (human HCC, mouse models and HCC cell lines35). Within this general framework, Lee et al. were able to identify a new subtype of HCC patients who shared a gene expression pattern with fetal hepatoblasts33,36.

Table 3.

Relevant proposals of molecular classifications of HCC

| Author | Technology applied | n | Molecular classes | Genomic alteration | Clinical correlation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laurent-Puig, 200131 | Mutation analysis and LOH | 137 | Chromosome instability | High FAL*. Mutations in Axin1 and p53. LOH in 1p, 4q, 16p, 16q, 13q, 9p, 6q | HBV infection, poor differentiation and prognosis | |

| Chromosome stability | High FAL. Mutations in β-catenin. LOH in 8p | Non-HBV infection. Larger tumors. | ||||

| Boyault, 200734 | Mutation analysis, LOH, promoter methylation, gene expression microarray, RT-PCR, western blot and IHC | 120 | G1 | Chromosome instability | Mutations in Axin1. LOH in 16q and 16p Mutations in PI3KCA and p53. Akt activation Mutations in p53. LOH 5q, 21q and 22q Non-specific alterations Mutations in β-catenin, hipermethylation of E-cadherin | HBV infection, young women and high AFP HBV infection. Hemochromatosis Satellites |

| G2 | ||||||

| G3 | ||||||

| G4 | Chromosome stability | |||||

| G5 | ||||||

| G6 | ||||||

| Chiang, 2007 (unpublished data)51 | SNP-array, gene expression microarray, mutation analysis and IHC | 103 | β-catenin | Mutations and nuclear translocation of β-catenin Activation of TKR-dependent pathways (IGF and mTOR). Chromosomal instability Overexpression of genes induced by IFN (STAT, IFI6, etc) Gains in chromosome 7. Overexpression of c-Met, COBL, SMO, etc. Non-specific alterations | Vascular invasion and high levels of AFP Lower recurrence rate Higher rates of early recurrence (<2 years) | |

| Proliferation | ||||||

| IFN-response | ||||||

| Poly 7 | ||||||

| Unannotated | ||||||

| Ye, 200340 | Gene expression microarray | 67 | Non-metastatic | Osteopontin overexpression | Worse survival | |

| Metastatic | ||||||

| Kurokawa, 200443 | Adaptor-tagged competitive PCR | 100 | Good signature | Known genes included in the signature: CDH1, IGF2R, RB1, NRG2 | Significant worse survival and higher rates of early recurrence | |

| Poor signature | ||||||

| Lee, 200432 | Gene expression microarray | 91 | Cluster A | Overexpression of cell proliferation markers and genes related to ubiquitination and sumoylation | Worse survival | |

| Cluster B | ||||||

| Cluster B | ||||||

| Lee, 200633 | Gene expression microarray | 139$ | Cluster A | HC subtype | Overexpression of AP-1 transcription factors (FOS, JUN) and markers of hepatic oval cells (KRT7, KRT19 and VIM) | Worse survival Worst survival |

| HB subtype | ||||||

| Budhu, 200687 | Gene expression microarray | 200& | Inflamation/immune respose cluster A | A 17 gene signature discriminates samples with or without metastasis. Genes included in the signature were mostly related to the immune/inflammatory response | Signature that predicted metastatic group had a significant shorter survival and time to recurrence | |

| Inflamation/immune respose cluster B | ||||||

| Katoh, 200730 | Array-based CGH | 87 | Cluster A | Subcluster A1 | Amplifications in 1q, 6p and/or 8q, gains 7 p/q and losses on 8p and 13q. Amplifications in 8q, losses on 8p and 13q, gains on 1q. Candidate oncogene: c-myc Gains on 6p, 7 p/q, 8q, 17q, and losses on 8p and 13q | Worse survival |

| Subcluster A2 | ||||||

| Subcluster A3 | ||||||

| Cluster B | Subcluster B1 | Non-specific alterations Amplifications in 17q and losses on 10q Gains in 9 p/q | Suggested activation of mTOR pathway. | |||

| Subcluster B2 | ||||||

| Subcluster B3 | ||||||

Fraction of evaluable autosomal arms demonstrating allelic deletion

Besides these 139 human HCC samples, 39 mouse HCC, rat fetal hepatoblasts and adult hepatocytes were also profiled

Gene expression studies were performed on adjacent non-tumoral tissue. Signatures were generated from tumoral microenvironment

Integrar algun mensaje de las Tablas 1 y 2 en el texo.

Preliminary attempts to classify HCC patients according to tumor molecular background were unidimensional, and based on genome-wide gene expression data37. Initial studies compared gene expression between HCC and non-tumoral tissue, and were later improved by gene expression analysis of the whole hepatocarcinogenic process (including cirrhotic tissue and preneoplastic lesions)38,39. Ye et al. studied 67 primary and metastatic HCC by an unsupervised hierarchical clustering algorithm interrogating 9,180 genes40. Interestingly, they failed to obtain significant differences in gene expression between primary and metastatic lesions. This feature is seminal to understand and characterize clonality in multinodular HCC, and it has been addressed elsewhere41. However, Ye et al. found that primary metastasis-free HCC had a gene expression profile markedly different from that of primary HCC with metastatic lesions, also with differences in patient survival. The 153-gene model provided a robust signature that correctly classified 100% of the training samples during cross-validation. All these data implied that genes favoring metastasis progression are initiated in the primary tumors, and authors argued that primary HCC with metastatic potential may be evolutionary distinct from metastasis-free primary HCC. Furthermore, stringent analysis of expression data unleashed osteopontin as a relevant mediator in metastatic HCC.

Similarly, another study using high-density oligonucleotide microarray reported a 12-gene signature able to predict early intrahepatic HCC recurrence with an accuracy of 93%42. Subsequently, and using a different technology (adaptor-tagged competitive PCR) in a training-validation approach, Kurokawa et al. studied gene expression in 60 HCC patients43. Authors selected a 20-gene signature out of 92 candidate genes able to predict early recurrence (< 2 years). The recurrence signature (“poor signature”) was validated in an independent cohort of 40 patients with a predictive accuracy close to 73%. The “poor signature” was an independent predictor of recurrence (HR 3.82, 95% IC 1.44–10.10, p=0.007). As noted, accuracy rates were lower than in previous studies, and unfortunately there were no common genes among these reports. Prognosis modeling using gene expression analysis was conducted in the Laboratory of Experimental Carcinogenesis (NCI, Bethesda, USA). In 2004, Lee et al. analyzed global gene expression patterns in 91 HCC to define the molecular characteristics of HCC, and to test the prognostic value of expression profiles32. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering revealed 2 classes of HCC patients characterized by significant differences in survival (30 vs 84 months in class A and B, respectively). After supervised analysis, authors found 406 genes whose expression was significantly informative of length of survival. Expression of typical cell proliferation markers was greater in class A. Both classes shared significant similarities when compared with non-tumoral tissue. This suggested that tumors in class A accumulated additional oncogenic alterations on top of a common HCC gene expression signature. However, data reported in this study did not exclude the possibility that different mechanisms were primarily responsible of two molecularly different types of tumors, referred as “etiological footprint” by the authors. This hypothesis was further explored in a second study where they tested if global gene expression analysis of human HCC would identify subtypes of HCC derived from different cells (hepatocytes and hepatic progenitor cells33). For that purpose, Lee et al. integrated data from gene expression of 139 human HCC, 39 rodent HCC (from 5 five different tumor mouse models), and rat fetal hepatoblasts and adult hepatocytes. They uncovered a new subclass of HCC (n=22 patients, “hepatoblast signature, HB”) that co-clustered with rat fetal hepatoblasts (Table 3). This signature was independently associated with both recurrence and worse survival, and it was enriched of JUN and FOS activity. The HB signature also displayed markers of hepatic progenitor cells (KRT7, KRT19 and VIM). Whether this signature is consequence of malignant transformation of mature hepatocytes with dedifferentiation remains unclear.

Chromosomal alterations in HCC have been surveyed by comparative genomic hybridization (CGH)44, array-based CGH and high-density single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) arrays45. Despite several technical improvements, recent array-based studies predominantly reported single copy gains and losses of entire chromosome arms, rather than recurrent high-level amplifications or homozygous deletions smaller than 5 Mb. This result suggests that multiple genes residing on the same chromosome arm may be under simultaneous selection, due to the synergistic proliferative advantages conferred by copy number alterations to these genes11. Recently, Katoh et al. proposed a molecular classification of HCC based on chromosomal alteration profiles detected with array-based CGH30. They identify 2 distinct patterns (clusters A and B) after analyzing 87 HCCs. Chromosomal alterations were observed more frequently in cluster A (1q, 6p, 8q gains, and 8p losses were almost exclusive to this cluster), and patients in this cluster had worse survival. Both clusters were further subdivided in 3 subclasses each. Subclusters B2 and A3 harbored amplification in 17q11.2–25.3, locus of the RPS6KB1 gene, a downstream molecule of the mTOR signaling pathway. Based on this finding, authors hypothesize that patients within these subclusters could be ideal candidates for mTOR inhibitors. Likewise, patients in subcluster A1 were distinctively characterized by amplifications in 1q and/or 6p. Among several potential oncogenes in these regions, VEGF seems to be an ideal candidate for selective target since several studies support the role of VEGF in HCC46–49. Also, positive results of a phase III clinical trial with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor against VEGFR –sorafenib-in advanced HCC reinforce the potential role of anti-VEGFR therapy in HCC50.

The study of HCC with a systems biology approach assumes that cancer deregulates a complex network of gene and proteins. Therefore, multi-parametric measurements assessing changes in this equilibrium will facilitate accurate prognostic and therapeutic modeling in a personalize medicine scenario. A pioneer study following a multidimensional approach analyzed 137 HCC patients that were characterized for mutations in p53, Axin1 and β-catenin in conjunction with evaluation of allelic loss using 335 microsatellite markers31. Based on these data, authors were able to classify HCC patients in two groups: First, a chromosomal instability class, defined by high FAL index (Fraction of evaluable autosomal arms demonstrating allelic deletion), and frequent mutations in p53 and Axin1. This group was significantly enriched with HBV infection, poor differentiated tumors, and patients had worse prognosis, similarly to cluster A in Katoh´s classification30. The second group, chromosomal stability, had low FAL index and mutations in β-catenin. Patients in this class tended to have larger tumors and to be non-HBV infected. The same researchers recently reported an update of this classification expanding the parameters evaluated34. Based on mutations in PI3KCA, EGFR, KRAS, NRAS and HRAS, promoter methylation, gene expression evaluated with microarray, qRT-PCR and protein analysis using western blot and immunohistochemistry (IHC), they identify 6 groups (G1-G6). G1-G3, included previously in the chromosomal instability group, were characterized by frequent allelic loss, mutations in Axin1 and p53, activation of Akt signaling and overexpression of IGF2. Young females with HBV infection and high serum AFP were the most relevant clinical features of G1-G2. Group 3 was enriched in genes associated with cell cycle. On the other hand, groups G5-G6 had lower rates of allelic loss (chromosomal stable), frequent β-catenin mutations and nuclear localization of β-catenin, what suggested activation of Wnt signaling. A gene signature formed by 16 genes was able to accurately allocate patients in each class. However, unlike their previous report, authors were unable to detect differences in survival within these six groups.

Recently, the Mount Sinai Liver Cancer Program performed an integrative genomic analysis on 103 HCV-related HCC using annotated data from SNP-array, gene expression profiling, mutation analysis and IHC (unpublished data)51. Five molecular subclasses were identified after unsupervised analysis of HCC transcriptome. Three of them further refine classes previously reported (activation of β-catenin34 and proliferation36 classes, interferon-related class). Also, this study detected a new class characterized by gains in chromosome 7.

Cellular ability to metastasize is a hallmark of cancer52. As mentioned before, gene expression studies have tried to classify HCC patients according to their predisposition to present intrahepatic metastasis40,42. Few investigations addressed the contribution of host genetic background (i.e. microenvironment) in this process. Budhu et al. compared the gene expression profiles of 115 non-tumoral adjacent liver tissues from HCC patients with and without venous or distant metastasis. Strikingly, a signature of 454 genes generated from adjacent non-tumoral tissue significantly distinguished patients with and without metastasis. Authors narrowed down to 17 the number of genes required to accurately classify patients according to metastasis potential, and they named it “refined liver microenvironment venous metastasis signature”. Genes in this signature were mostly related to the immune/inflammatory response. In addition, this signature showed that the predicted metastatic group had a significant shorter survival and time to recurrence.

Remarkably, there is certain degree of class aggregation across the different molecular classifications of HCC proposed so far. As an example, in three independent studies there is high concordance in a subclass of HCC patients characterized by dysregulation of genes related to cell proliferation (G1-G3 classes in Boyault’s34study, Proliferation class in Chiang’s study51 and HA class in Lee’s study33). Also, it is consistent throughout different reports the existence of a group of patients with recurrent chromosomal aberrations, suggesting chromosomal instability. However, there is still contradictory data among studies, and a significant group of patients remain repeatedly unclassified.

TARGETED THERAPIES IN HCC: INSIGHTS FROM A PERSONALIZED MEDICINE APPROACH

Assuming a personalized medicine perspective, when clinically applicable tools are available to accurately classify HCC patients according to their tumor molecular background, it would be feasible to customize therapies. Unfortunately, in some studies the use of molecular therapies has by-passed this mandatory understanding of the molecular portrait of cancer. The first evidence of molecular prediction of response was reported with the fusion kinase bcr-abl and response to imatinib in chronic myeloid leukemia. Following this landmark discovery, the response to trastuzumab in patients with breast cancer harboring amplifications of HER2/nu represent the most characteristic example of molecular prediction of response to targeted therapies in solid tumors. Other less compelling examples are the prediction of response to erlotinib in patients with NSCLC with EGFR amplifications/mutations. HCC is a particular case in oncology. Unlike most of the solid tumors, deaths in HCC can be related to the tumor or to liver dysfunction. Hence, it is essential to correctly design clinical trials in HCC. In order to capture antineoplastic effect in an investigational drug, HCC, and not liver dysfunction, has to dictate response to treatment. Recently, a panel of experts has published some guidelines for the design of clinical trials in HCC53. The introduction of biological agents as therapeutic options in oncology has changed the traditional paradigm to measure the antitumoral effect of new agents in the clinical trial scenario. The most important issues are regarding which should be the primary and secondary endpoints in controlled clinical trials. Obviously, objective response is a weak surrogate of activity in phase II trials, since in most cases, the predominant effect of these compounds is basically cytostatic. In fact, bevacizumab has shown a survival benefit in patients with liver metastases, as has erlotinib in advanced lung cancer and sorafenib in renal cancer, even when objective responses were less than 10%. Therefore, it is mandatory to select primary endpoints able to capture the effects associated with stabilization of the disease for clinically relevant periods. These endpoints need to have a time-to-event format. Progression-free survival is the best endpoint in most human malignancies, but it is not appropriate in HCC since it combines two types of events: progression and death due to any etiology. Therefore, it is recommended the inclusion of time-to-progression (period between the inclusion in the study and the radiological progression of the disease) as the primary endpoint in phase II trials, and survival as the endpoint in phase III trials53.

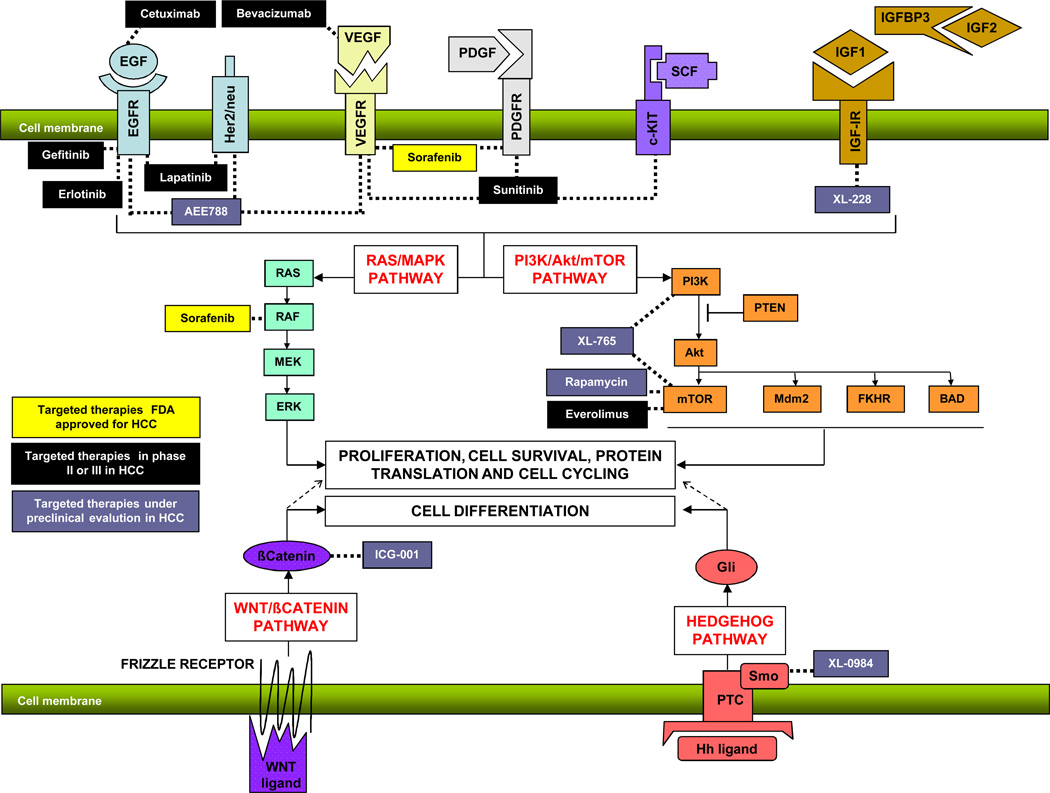

Several studies have tried to establish the activation status of different signaling pathways in HCC. Data suggest activation of numerous oncogenic signaling routes in HCC (i.e. EGF, IGF and HGF signaling, RAS/MAPK, Akt/mTOR pathway, NF-Kappaβ, TGF-β signalin, Wnt-βCatenin, etc11,54). Consequently, several drugs have been developed to block these pathways at different levels (Fig 1). However, since pathway activation is not uniform in all HCC patients, it would be desirable to know a priori which pathway is activated in every patient. This concept is tightly linked to the molecular classification of HCC since some molecular classes are led by the activation of certain pathways (e.g. β-catenin in class G5–6 of Boyault34).

Figure 1.

Signaling pathways and targeted therapies in HCC. This figure summarizes some of the most relevant signaling pathways analyzed in human HCC (RAS/MAPK, Akt/mTOR, Wnt-βcatenin and Hedgehog). Also, it shows different drugs in clinical and preclinical development for the specific blockade of these pathways.

Different phase II and III trials have evaluated molecular therapies in HCC50,55–61. Most of them used drugs that block EGF signaling (erlotinib) and angiogenesis (bevacizumab), and there is only one study that analyzed association regimes with traditional chemotherapy60. Eckel et al. reported a phase II trial testing imatinib in 17 HCC patients56. Authors reported a median survival of 12 weeks and 33% of patients with stable disease. Interestingly, only one of the patients in this trial was positive for PDGFR and none was positive for c-Kit. It is difficult to know if imatinib could play a role in HCC if almost none of the patients in this trial had activation of two of the most relevant targets of this drug. Two phase II trials have been conducted with erlotinib in HCC58,59. The fact that the rate of stable disease in both studies is quite different suggests that the population selected for both trials was not uniform. Both studies analyzed EGFR receptor status with IHC, and both agreed in the absence of predictive power of this marker for response to erlotinib. However, significant differences in time to progression in patients treated to sorafenib according to the phosphorylation status of ERK, a known downstream molecule of B-RAF were reported55. Again, it is unclear if the selection of IHC for total EGFR as biomarker of response to erlotinib is accurate enough in HCC. In other malignancies, the presence of amplifications or phosphorylation of EGFR (hallmark of activation of the receptor) and other downstream molecules predicted response to tyrosine kinase inhibitors62.

A major breakthrough occurred in 2007 in the targeted therapy field in HCC. An oral multikinase inhibitor (sorafenib) with activity against several tyrosine kinase (VEGFR2, PDGFR, c-Kit receptors), and serine/threonine kinases (B-RAF, p38) was able to significantly increase survival in patients with advanced HCC50,63. This was the first phase III trial to show positive results with a target therapy in HCC, and it was also the first systemic therapy to increase survival in advanced HCC. Previously, a phase II clinical trial involving 137 patients with advanced HCC exposed that sorafenib induced stable disease for 4 months in 35% of the patients with an overall median survival of 9.7 months55. Partial response rate was less than 10%.

The randomized phase III double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial conducted in patients with advanced HCC treated with sorafenib has shown improvement in survival of 3 months in patients with advanced HCC, which was not only statistically significant, but also clinically meaningful50. The study was stopped at the second planned interim analysis because of survival advantages favoring the treatment arm. The median overall survival was 10.7 months with sorafenib and 7.9 months with placebo (hazard ratio for death, 0.69; 95% confidence interval, 0.55 to 0.87; P<0.001). The magnitude of the difference-reflected by the HR of 0.69-compares well with the differences obtained with other targeted therapies in colorectal cancer (cetuximab, bevacizumab), renal cancer (temsirolimus), breast cancer (trastuzumab) and lung cancer (erlotinib). Median time to progression was 5.5 months with sorafenib versus 2.8 months with placebo (hazard ratio 0.58; 95% confidence interval 0.45 to 0.74; P<0.001). Seven patients (2.3%) in the sorafenib group and two patients (0.7%) in the placebo group achieved a partial response. Recently, the drug has been approved both by FDA and EMEA for the treatment of HCC.

Sorafenib targets two of the main pathways involved in hepatocarcinogenesis by blocking angiogenesis (VEFGR2 and PDGFR) and cell proliferation through Ras/MAPK signaling (b-RAF). An exhaustive analysis of the trial data suggests that the majority of patients receiving sorafenib achieve some clinical benefit. It is biologically plausible that a drug able to block different molecules will benefit a wide range of patients since many signaling pathways will be target simultaneously. Thus, sorafenib is de facto acting as a multitarget therapy in HCC. Additional challenges will be to combine this drug with other targeted therapies blocking signaling networks untouched by sorafenib, particularly in those patients with chromosomal instability that could have several signaling pathways aberrantly activated. Potential combination therapies are summarized in Figure 1.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

The development of a molecular classification of HCC is crucial. Until the molecular pathogenesis of HCC is completely understood, it would be complicated to achieve high rates of curation with targeted therapies. Many progresses have been made in this regard, and preliminary reports using genome-wide approaches confirm the high genetic heterogeneity of HCC. It seems that a subgroup of patients have activation of pathways related to cell proliferation (IGF signaling, ras/MAPKK and mTOR signaling) and differentiation (Wnt-βcatenin). Etiology of the underlying liver disease also seems to confer specific chromosomal aberrations. It is also clear that tumor microenvironment plays a major role in HCC intrahepatic metastasis. Probably, gene expression studies will soon allow predicting risk for HCC development based on the gene signature in cirrhotic tissue. Fortunately, sorafenib has opened the trail for target therapies in HCC. Certainly, the conjunction of precise knowledge of the molecular classes of HCC, well-designed clinical trials, and effective blockade of specific pathways with new therapies will definitely implement personalized medicine for the clinical management of HCC.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: Josep M. Llovet is Professor of Research-Institut Català de Recerca Avançada (ICREA, IDIBAPS, Hospital Clínic Barcelona) and is supported by grants from the U.S. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (1R01DK076986-01), the Spanish National Health Institute (SAF-2007-61898) and the Samuel Waxman Cancer Research Foundation. Augusto Villanueva is supported by a grant from Fundación Caixa Galicia and is the recipient of a National Cancer Center Fellowship. Sara Toffanin is supported by a fellowship from Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC).

Abbreviations

- CGH

Comparative genomic hybridization

- FISH

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HBV

Hepatitis B virus

- HCV

Hepatitis C virus

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- LOH

Loss of heterozygosity

- NSCLC

non-small cell lung cancer

- RT-PCR

real-time polymerase chain reaction

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- TKR

Tyrosine Kinase Receptor

REFERENCES

- 1.Bosch FX, Ribes J, Diaz M, Cleries R. Primary liver cancer: worldwide incidence and trends. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:S5–S16. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fattovich G, Stroffolini T, Zagni I, Donato F. Hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: incidence and risk factors. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:S35–S50. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sherman M. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology, risk factors, and screening. Semin Liver Dis. 2005;25:143–154. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-871194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brechot C, Thiers V, Kremsdorf D, Nalpas B, Pol S, Paterlini-Brechot P. Persistent hepatitis B virus infection in subjects without hepatitis B surface antigen: clinically significant or purely “occult”? Hepatology. 2001;34:194–203. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.25172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okuda K. Hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2000;32:225–237. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80428-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang MH, Chen CJ, Lai MS, Hsu HM, Wu TC, Kong MS, Liang DC, Shau WY, Chen DS. Universal hepatitis B vaccination in Taiwan, the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in children Taiwan Childhood Hepatoma Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1855–1859. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199706263362602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Serag HB, Mason AC. Rising incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:745–750. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903113401001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Llovet JM, Bruix J. Systematic review of randomized trials for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: Chemoembolization improves survival. Hepatology. 2003;37:429–442. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Llovet JM, Burroughs A, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2003;362:1907–1917. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14964-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopez PM, Villanueva A, Llovet JM. Systematic review: evidence-based management of hepatocellular carcinoma--an updated analysis of randomized controlled trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:1535–1547. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Villanueva A, Newell P, Chiang DY, Friedman SL, Llovet JM. Genomics and signaling pathways in hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2007;27:55–76. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burke W, Psaty BM. Personalized medicine in the era of genomics. Jama. 2007;298:1682–1684. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.14.1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmidt C. Newly revealed genome complexity may mean personalized medicine is farther away. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1568–1570. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson K, Jacobson JS, Heitjan DF, Zivin JG, Hershman D, Neugut AI, Grann VR. Cost-effectiveness of preventive strategies for women with a BRCA1 or a BRCA2 mutation. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:397–406. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-6-200603210-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsao MS, Sakurada A, Cutz JC, Zhu CQ, Kamel-Reid S, Squire J, Lorimer I, Zhang T, Liu N, Daneshmand M, Marrano P, da Cunha Santos G, Lagarde A, Richardson F, Seymour L, Whitehead M, Ding K, Pater J, Shepherd FA. Erlotinib in lung cancer - molecular and clinical predictors of outcome. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:133–144. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyerson M, Carbone D. Genomic and proteomic profiling of lung cancers: lung cancer classification in the age of targeted therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3219–3226. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.15.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hortobagyi GN. Trastuzumab in the treatment of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1734–1736. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe058196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paez JG, Janne PA, Lee JC, Tracy S, Greulich H, Gabriel S, Herman P, Kaye FJ, Lindeman N, Boggon TJ, Naoki K, Sasaki H, Fujii Y, Eck MJ, Sellers WR, Johnson BE, Meyerson M. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004;304:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.1099314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Golub TR, Slonim DK, Tamayo P, Huard C, Gaasenbeek M, Mesirov JP, Coller H, Loh ML, Downing JR, Caligiuri MA, Bloomfield CD, Lander ES. Molecular classification of cancer: class discovery and class prediction by gene expression monitoring. Science. 1999;286:531–537. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quackenbush J. Microarray analysis and tumor classification. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2463–2472. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra042342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ntzani EE, Ioannidis JP. Predictive ability of DNA microarrays for cancer outcomes and correlates: an empirical assessment. Lancet. 2003;362:1439–1444. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14686-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee JS, Thorgeirsson SS. Genome-scale profiling of gene expression in hepatocellular carcinoma: classification, survival prediction, and identification of therapeutic targets. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:S51–S55. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO, Botstein D. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:14863–14868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Michiels S, Koscielny S, Hill C. Prediction of cancer outcome with microarrays: a multiple random validation strategy. Lancet. 2005;365:488–492. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17866-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Llovet JM, Bru C, Bruix J. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: the BCLC staging classification. Semin Liver Dis. 1999;19:329–338. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marrero JA. Staging systems for hepatocellular carcinoma: should we all use the BCLC system? J Hepatol. 2006;44:630–632. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marrero JA, Fontana RJ, Barrat A, Askari F, Conjeevaram HS, Su GL, Lok AS. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison of 7 staging systems in an American cohort. Hepatology. 2005;41:707–716. doi: 10.1002/hep.20636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buendia MA. Genetics of hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Cancer Biol. 2000;10:185–200. doi: 10.1006/scbi.2000.0319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thorgeirsson SS, Grisham JW. Molecular pathogenesis of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2002;31:339–346. doi: 10.1038/ng0802-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katoh H, Ojima H, Kokubu A, Saito S, Kondo T, Kosuge T, Hosoda F, Imoto I, Inazawa J, Hirohashi S, Shibata T. Genetically distinct and clinically relevant classification of hepatocellular carcinoma: putative therapeutic targets. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1475–1486. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laurent-Puig P, Legoix P, Bluteau O, Belghiti J, Franco D, Binot F, Monges G, Thomas G, Bioulac-Sage P, Zucman-Rossi J. Genetic alterations associated with hepatocellular carcinomas define distinct pathways of hepatocarcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1763–1773. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.24798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee JS, Chu IS, Heo J, Calvisi DF, Sun Z, Roskams T, Durnez A, Demetris AJ, Thorgeirsson SS. Classification and prediction of survival in hepatocellular carcinoma by gene expression profiling. Hepatology. 2004;40:667–676. doi: 10.1002/hep.20375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee JS, Heo J, Libbrecht L, Chu IS, Kaposi-Novak P, Calvisi DF, Mikaelyan A, Roberts LR, Demetris AJ, Sun Z, Nevens F, Roskams T, Thorgeirsson SS. A novel prognostic subtype of human hepatocellular carcinoma derived from hepatic progenitor cells. Nat Med. 2006;12:410–416. doi: 10.1038/nm1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boyault S, Rickman DS, de Reynies A, Balabaud C, Rebouissou S, Jeannot E, Herault A, Saric J, Belghiti J, Franco D, Bioulac-Sage P, Laurent-Puig P, Zucman-Rossi J. Transcriptome classification of HCC is related to gene alterations and to new therapeutic targets. Hepatology. 2007;45:42–52. doi: 10.1002/hep.21467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thorgeirsson SS, Lee JS, Grisham JW. Functional genomics of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2006;43:S145–S150. doi: 10.1002/hep.21063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen X, Cheung ST, So S, Fan ST, Barry C, Higgins J, Lai KM, Ji J, Dudoit S, Ng IO, Van De Rijn M, Botstein D, Brown PO. Gene expression patterns in human liver cancers. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:1929–1939. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-02-0023.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thorgeirsson SS, Lee JS, Grisham JW. Molecular prognostication of liver cancer: end of the beginning. J Hepatol. 2006;44:798–805. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wurmbach E, Chen YB, Khitrov G, Zhang W, Roayaie S, Schwartz M, Fiel I, Thung S, Mazzaferro V, Bruix J, Bottinger E, Friedman S, Waxman S, Llovet JM. Genome-wide molecular profiles of HCV-induced dysplasia and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2007;45:938–947. doi: 10.1002/hep.21622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nam SW, Park JY, Ramasamy A, Shevade S, Islam A, Long PM, Park CK, Park SE, Kim SY, Lee SH, Park WS, Yoo NJ, Liu ET, Miller LD, Lee JY. Molecular changes from dysplastic nodule to hepatocellular carcinoma through gene expression profiling. Hepatology. 2005;42:809–818. doi: 10.1002/hep.20878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ye QH, Qin LX, Forgues M, He P, Kim JW, Peng AC, Simon R, Li Y, Robles AI, Chen Y, Ma ZC, Wu ZQ, Ye SL, Liu YK, Tang ZY, Wang XW. Predicting hepatitis B virus-positive metastatic hepatocellular carcinomas using gene expression profiling and supervised machine learning. Nat Med. 2003;9:416–423. doi: 10.1038/nm843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheung ST, Chen X, Guan XY, Wong SY, Tai LS, Ng IO, So S, Fan ST. Identify metastasis-associated genes in hepatocellular carcinoma through clonality delineation for multinodular tumor. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4711–4721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iizuka N, Oka M, Yamada-Okabe H, Nishida M, Maeda Y, Mori N, Takao T, Tamesa T, Tangoku A, Tabuchi H, Hamada K, Nakayama H, Ishitsuka H, Miyamoto T, Hirabayashi A, Uchimura S, Hamamoto Y. Oligonucleotide microarray for prediction of early intrahepatic recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection. Lancet. 2003;361:923–929. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12775-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kurokawa Y, Matoba R, Takemasa I, Nagano H, Dono K, Nakamori S, Umeshita K, Sakon M, Ueno N, Oba S, Ishii S, Kato K, Monden M. Molecular-based prediction of early recurrence in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2004;41:284–291. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moinzadeh P, Breuhahn K, Stutzer H, Schirmacher P. Chromosome alterations in human hepatocellular carcinomas correlate with aetiology and histological grade--results of an explorative CGH meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:935–941. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Speicher MR, Carter NP. The new cytogenetics: blurring the boundaries with molecular biology. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:782–792. doi: 10.1038/nrg1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chao Y, Li CP, Chau GY, Chen CP, King KL, Lui WY, Yen SH, Chang FY, Chan WK, Lee SD. Prognostic significance of vascular endothelial growth factor, basic fibroblast growth factor, and angiogenin in patients with resectable hepatocellular carcinoma after surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:355–362. doi: 10.1245/aso.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Petit AM, Rak J, Hung MC, Rockwell P, Goldstein N, Fendly B, Kerbel RS. Neutralizing antibodies against epidermal growth factor and ErbB-2/neu receptor tyrosine kinases down-regulate vascular endothelial growth factor production by tumor cells in vitro and in vivo: angiogenic implications for signal transduction therapy of solid tumors. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:1523–1530. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Raskopf E, Dzienisowicz C, Hilbert T, Rabe C, Leifeld L, Wernert N, Sauerbruch T, Prieto J, Qian C, Caselmann WH, Schmitz V. Effective angiostatic treatment in a murine metastatic and orthotopic hepatoma model. Hepatology. 2005;41:1233–1240. doi: 10.1002/hep.20724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou J, Tang ZY, Fan J, Wu ZQ, Li XM, Liu YK, Liu F, Sun HC, Ye SL. Expression of platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor in hepatocellular carcinoma and portal vein tumor thrombus. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2000;126:57–61. doi: 10.1007/s004320050009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Llovet J, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Raoul J, Zeuzem S, Poulin-Costello M, Moscovici M, Voliotis D, Bruix J. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. ASCO Proceedings. 2007 LBA1. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chiang D, Villanueva A, Hoshiya Y, Peix J, Newell P, Minguez B, Cozza A, Donovan D, Thung S, Sole M, Tovar V, Alsinet C, Ramos AH, Barretina J, Roayaie S, Schwartz M, Waxman S, Bruix J, Mazzaferro V, Ligon A, Najfeld V, Friedman S, Sellers WR, Meyerson M, Llovet J. Focal VEGFA gains and molecular classification of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Research. 2008 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0742. (submitted) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Llovet J, Di Bisceglie A, J Bruix J, Kramer B, Lencioni R, Zhu A, Sherman M, Schwartz M, Lotze M, Talwalkar J, Gores GJ. Design and end-points of clinical trials in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008 doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn134. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roberts LR, Gores GJ. Hepatocellular carcinoma: molecular pathways and new therapeutic targets. Semin Liver Dis. 2005;25:212–215. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-871200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Abou-Alfa GK, Schwartz L, Ricci S, Amadori D, Santoro A, Figer A, De Greve J, Douillard JY, Lathia C, Schwartz B, Taylor I, Moscovici M, Saltz LB. Phase II study of sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4293–4300. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.3441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Eckel F, von Delius S, Mayr M, Dobritz M, Fend F, Hosius C, Schleyer E, Schulte-Frohlinde E, Schmid RM, Lersch C. Pharmacokinetic and clinical phase II trial of imatinib in patients with impaired liver function and advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology. 2005;69:363–371. doi: 10.1159/000089990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gish RG, Porta C, Lazar L, Ruff P, Feld R, Croitoru A, Feun L, Jeziorski K, Leighton J, Gallo J, Kennealey GT. Phase III randomized controlled trial comparing the survival of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma treated with nolatrexed or doxorubicin. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3069–3075. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.4046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Philip PA, Mahoney MR, Allmer C, Thomas J, Pitot HC, Kim G, Donehower RC, Fitch T, Picus J, Erlichman C. Phase II study of Erlotinib (OSI-774) in patients with advanced hepatocellular cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6657–6663. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.14.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thomas MB, Chadha R, Glover K, Wang X, Morris J, Brown T, Rashid A, Dancey J, Abbruzzese JL. Phase 2 study of erlotinib in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2007;110:1059–1067. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhu AX, Blaszkowsky LS, Ryan DP, Clark JW, Muzikansky A, Horgan K, Sheehan S, Hale KE, Enzinger PC, Bhargava P, Stuart K. Phase II study of gemcitabine and oxaliplatin in combination with bevacizumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1898–1903. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.9130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhu AX, Stuart K, Blaszkowsky LS, Muzikansky A, Reitberg DP, Clark JW, Enzinger PC, Bhargava P, Meyerhardt JA, Horgan K, Fuchs CS, Ryan DP. Phase 2 study of cetuximab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2007;110:581–589. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cappuzzo F, Hirsch FR, Rossi E, Bartolini S, Ceresoli GL, Bemis L, Haney J, Witta S, Danenberg K, Domenichini I, Ludovini V, Magrini E, Gregorc V, Doglioni C, Sidoni A, Tonato M, Franklin WA, Crino L, Bunn PA, Jr., Varella-Garcia M. Epidermal growth factor receptor gene and protein and gefitinib sensitivity in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:643–655. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wilhelm SM, Carter C, Tang L, Wilkie D, McNabola A, Rong H, Chen C, Zhang X, Vincent P, McHugh M, Cao Y, Shujath J, Gawlak S, Eveleigh D, Rowley B, Liu L, Adnane L, Lynch M, Auclair D, Taylor I, Gedrich R, Voznesensky A, Riedl B, Post LE, Bollag G, Trail PA. BAY 43-9006 exhibits broad spectrum oral antitumor activity and targets the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway and receptor tyrosine kinases involved in tumor progression and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7099–7109. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ithier G, Girard M, Stoppa-Lyonnet D. Breast cancer and BRCA1 mutations. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1198–1199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Powell SM, Papadopoulos N, Kinzler KW, Smolinski KN, Meltzer SJ. APC gene mutations in the mutation cluster region are rare in esophageal cancers. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1759–1763. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90818-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Powell SM, Zilz N, Beazer-Barclay Y, Bryan TM, Hamilton SR, Thibodeau SN, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. APC mutations occur early during colorectal tumorigenesis. Nature. 1992;359:235–237. doi: 10.1038/359235a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lips CJ, Hoppener JW, Thijssen JH. Medullary thyroid carcinoma: role of genetic testing and calcitonin measurement. Ann Clin Biochem. 2001;38:168–179. doi: 10.1258/0004563011900614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Berwick M, Orlow I, Hummer AJ, Armstrong BK, Kricker A, Marrett LD, Millikan RC, Gruber SB, Anton-Culver H, Zanetti R, Gallagher RP, Dwyer T, Rebbeck TR, Kanetsky PA, Busam K, From L, Mujumdar U, Wilcox H, Begg CB. The prevalence of CDKN2A germ-line mutations and relative risk for cutaneous malignant melanoma: an international population-based study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1520–1525. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Llovet JM, Chen Y, Wurmbach E, Roayaie S, Fiel MI, Schwartz M, Thung SN, Khitrov G, Zhang W, Villanueva A, Battiston C, Mazzaferro V, Bruix J, Waxman S, Friedman SL. A molecular signature to discriminate dysplastic nodules from early hepatocellular carcinoma in HCV cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1758–1767. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Robinson HM, Martineau M, Harris RL, Barber KE, Jalali GR, Moorman AV, Strefford JC, Broadfield ZJ, Cheung KL, Harrison CJ. Derivative chromosome 9 deletions are a significant feature of childhood Philadelphia chromosome positive acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Leukemia. 2005;19:564–571. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Radich J, Gehly G, Lee A, Avery R, Bryant E, Edmands S, Gooley T, Kessler P, Kirk J, Ladne P, Thomas ED, Appelbaum FR. Detection of bcr-abl transcripts in Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia after marrow transplantation. Blood. 1997;89:2602–2609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hurd DD, Vukelich M, Arthur DC, Lindquist LL, McKenna RW, Peterson BA, Bloomfield CD. 15;17 Translocation in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1982;6:331–337. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(82)90089-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kenny FS, Hui R, Musgrove EA, Gee JM, Blamey RW, Nicholson RI, Sutherland RL, Robertson JF. Overexpression of cyclin D1 messenger RNA predicts for poor prognosis in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:2069–2076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Huncharek M, Muscat J, Geschwind JF. K-ras oncogene mutation as a prognostic marker in non-small cell lung cancer: a combined analysis of 881 cases. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:1507–1510. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.8.1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Slebos RJ, Kibbelaar RE, Dalesio O, Kooistra A, Stam J, Meijer CJ, Wagenaar SS, Vanderschueren RG, van Zandwijk N, Mooi WJ, et al. K-ras oncogene activation as a prognostic marker in adenocarcinoma of the lung. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:561–565. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199008303230902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jen J, Kim H, Piantadosi S, Liu ZF, Levitt RC, Sistonen P, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Hamilton SR. Allelic loss of chromosome 18q and prognosis in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:213–221. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199407283310401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Offit K, Lo Coco F, Louie DC, Parsa NZ, Leung D, Portlock C, Ye BH, Lista F, Filippa DA, Rosenbaum A, et al. Rearrangement of the bcl-6 gene as a prognostic marker in diffuse large-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:74–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199407143310202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.van de Vijver MJ, He YD, van't Veer LJ, Dai H, Hart AA, Voskuil DW, Schreiber GJ, Peterse JL, Roberts C, Marton MJ, Parrish M, Atsma D, Witteveen A, Glas A, Delahaye L, van der Velde T, Bartelink H, Rodenhuis S, Rutgers ET, Friend SH, Bernards R. A gene-expression signature as a predictor of survival in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1999–2009. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Paik S, Shak S, Tang G, Kim C, Baker J, Cronin M, Baehner FL, Walker MG, Watson D, Park T, Hiller W, Fisher ER, Wickerham DL, Bryant J, Wolmark N. A multigene assay to predict recurrence of tamoxifen-treated, node-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2817–2826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tamoxifen for early breast cancer: an overview of the randomised trials. Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group. Lancet. 1998;351:1451–1467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Piccart-Gebhart MJ, Procter M, Leyland-Jones B, Goldhirsch A, Untch M, Smith I, Gianni L, Baselga J, Bell R, Jackisch C, Cameron D, Dowsett M, Barrios CH, Steger G, Huang CS, Andersson M, Inbar M, Lichinitser M, Lang I, Nitz U, Iwata H, Thomssen C, Lohrisch C, Suter TM, Ruschoff J, Suto T, Greatorex V, Ward C, Straehle C, McFadden E, Dolci MS, Gelber RD. Trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1659–1672. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hirsch FR, Varella-Garcia M, Bunn PA, Jr., Franklin WA, Dziadziuszko R, Thatcher N, Chang A, Parikh P, Pereira JR, Ciuleanu T, von Pawel J, Watkins C, Flannery A, Ellison G, Donald E, Knight L, Parums D, Botwood N, Holloway B. Molecular predictors of outcome with gefitinib in a phase III placebo-controlled study in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5034–5042. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.3958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hirsch FR, Varella-Garcia M, McCoy J, West H, Xavier AC, Gumerlock P, Bunn PA, Jr., Franklin WA, Crowley J, Gandara DR. Increased epidermal growth factor receptor gene copy number detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization associates with increased sensitivity to gefitinib in patients with bronchioloalveolar carcinoma subtypes: a Southwest Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6838–6845. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sawyers CL, Hochhaus A, Feldman E, Goldman JM, Miller CB, Ottmann OG, Schiffer CA, Talpaz M, Guilhot F, Deininger MW, Fischer T, O'Brien SG, Stone RM, Gambacorti-Passerini CB, Russell NH, Reiffers JJ, Shea TC, Chapuis B, Coutre S, Tura S, Morra E, Larson RA, Saven A, Peschel C, Gratwohl A, Mandelli F, Ben-Am M, Gathmann I, Capdeville R, Paquette RL, Druker BJ. Imatinib induces hematologic and cytogenetic responses in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia in myeloid blast crisis: results of a phase II study. Blood. 2002;99:3530–3539. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.10.3530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.van Oosterom AT, Judson I, Verweij J, Stroobants S, Donato di Paola E, Dimitrijevic S, Martens M, Webb A, Sciot R, Van Glabbeke M, Silberman S, Nielsen OS. Safety and efficacy of imatinib (STI571) in metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumours: a phase I study. Lancet. 2001;358:1421–1423. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)06535-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gordon MS, Matei D, Aghajanian C, Matulonis UA, Brewer M, Fleming GF, Hainsworth JD, Garcia AA, Pegram MD, Schilder RJ, Cohn DE, Roman L, Derynck MK, Ng K, Lyons B, Allison DE, Eberhard DA, Pham TQ, Dere RC, Karlan BY. Clinical activity of pertuzumab (rhuMAb 2C4), a HER dimerization inhibitor, in advanced ovarian cancer: potential predictive relationship with tumor HER2 activation status. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4324–4332. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.4221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Budhu A, Forgues M, Ye QH, Jia HL, He P, Zanetti KA, Kammula US, Chen Y, Qin LX, Tang ZY, Wang XW. Prediction of venous metastases, recurrence, and prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma based on a unique immune response signature of the liver microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:99–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]