Abstract

We report Barium (Ba) cathode layer for bulk-heterojunction solar cells which enhanced the fill factor (FF) of p-DTS(FBTTh2)2/PC71BM BHJ solar cell up to 75.1%, one of the highest value reported for an organic solar cell. The external quantum efficiency exceeds 80%. Analysis of recombination mechanisms using the current-voltage (J–V) characteristics at various light intensities in the BHJ solar cell layer reveals that Ba prevents trap assisted Shockley-Read-Hall (SRH) recombination at the interface and with different thicknesses of the Ba, the recombination shifts towards bimolecular from monomolecular. Moreover, Ba increases shunt resistance and decreases the series resistance significantly. This results in an increase in the charge collection probability leading to high FF. This work identifies a new cathode interlayer which outclasses the all the reported interlayers in increasing FF leading to high power conversion efficiency and have significant implications in improving the performance of BHJ solar cells.

Bulk-heterojunction (BHJ) organic solar cells are of significant interest for sun-light harvesting devices because of the potential for low cost of manufacturing of large areas through roll-to-roll coating technologies on flexible substrates1,2,3,4,5,6. The power conversion efficiency PCE of a solar cell is determined by three key parameters i.e. open circuit voltage (Voc), the short circuit current (Jsc) and the fill factor (FF). Voc is correlated with the energy difference between the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) of the donor (conjugated polymer or small molecule) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of the acceptor (typically a fullerene derivative) whereas Jsc is determined by the absorption spectrum and absorption depth of the organic donor and the transport of photogenerated carriers through the morphology of the film. In order to achieve high Jsc and Voc in BHJ solar cells, low band gap polymers and solution processable small molecules (for use in Tandem Cells) have been developed with PCE exceeding 7%7,8,9,10. It is, however, necessary to find ways to improve the FF for achieving higher PCE values11.

Interlayers play a significant role in improving the FF by minimizing the contact resistance and charge recombination and for enabling efficient extraction (or blocking) of holes and electrons. The use of interlayers circumvents the direct contact between the photoactive donor (polymer or small molecule) and electrodes where high densities of carrier traps and interface dipoles can hinder efficient charge collection. Consequently, a significant effort in interfacial engineering has developed using metal oxides (MoO3, CsCO3, TiOx, NiO, WO3, V2O5 and ZnO, Ca)12,13,14,15,16,17,18, LiF19,20, bathocuproine (BCP)21,22, and self-assembled monolayers (SAMs)23. Although several metal oxides have been studied as anode interlayer or hole transport layer (HTL), poly (3,4-ethylene dioxythiophene):(polystyrene sulfonic acid) (PEDOT:PSS) is most commonly used as the anode interlayer or hole transporting layer (HTL) due to its high work function and compatibility with ITO. However, the cathode interlayer remains an open area for research due to unavailability of low work function materials that can effectively block holes. Recently, conjugated polyelectrolytes (CPEs), which are conjugated polymers with pendent group bearing ionic functionalities24,25,26,27, have been shown to improve the PCE to values in excess of 8%6,28,

In this work, we demonstrate that pure Barium (Ba) metal (capped by Aluminum) as the cathode layer improves the FF to 75.1%. This high FF BHJ solar cell is based on the small molecule donor, 7,7′-(4,4-bis(2-ethylhexyl)-4H-silolo[3,2-b:4,5-b′]dithiophene-2,6-diyl)bis(6-fluoro-4-(5′-hexyl-[2,2′-bithiophen]-5-yl)benzo [c][1,2,5]thiadiazole), (p-DTS(FBTTh2)2)9. With the insertion of a 10–20 nm thick Ba layer capped by Aluminum (100 nm), the FF increases from 56% to 74.2~75.1% and the PCE increases from 5.86% to 7.78~8.57%. The results are compared with state-of-the-art Ca/Al devices for the same thicknesses.

Results

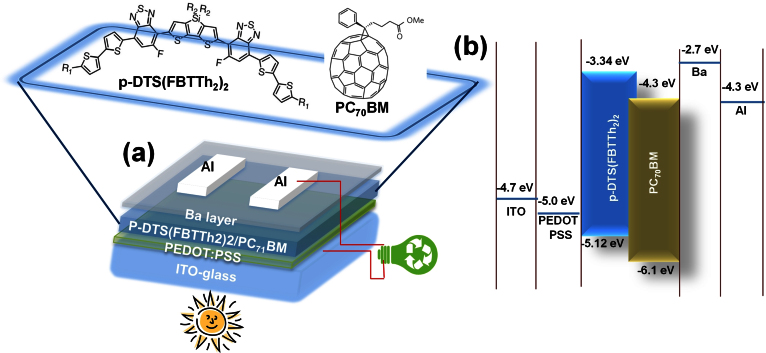

The molecular structure of p-DTS(FBTTh2)2 and PC71BM, the device structure and the energy levels of the components used in the devices are shown in Figure 1a, b, respectively. A blend of p-DTS(FBTTh2)2 and [6-6]-phenyl C71 butyric acid methyl ester (PC71BM) in 6:4 ratio is used as the active layer for device fabrication as detailed in method section. We used different thicknesses of Ba (10, 20, 30 nm) between p-DTS(FBTTh2)2: PC71BM photoactive blend and the Aluminum (100 nm) capping layer and studied the device performance.

Figure 1.

(a) The device structure of the inverted p-DTS(FBTTh2)2:PC71BM solar cell. Inset shows the molecular structures of p-DTS(FBTTh2)2 and PC71BM. (b) Energy level diagram of SM-BHJ solar cells with sequential layers of ITO/PEDOT:PSS/p-DTS(FBTTh2)2:PC71BM BHJ/Ba layer/Al cathode.

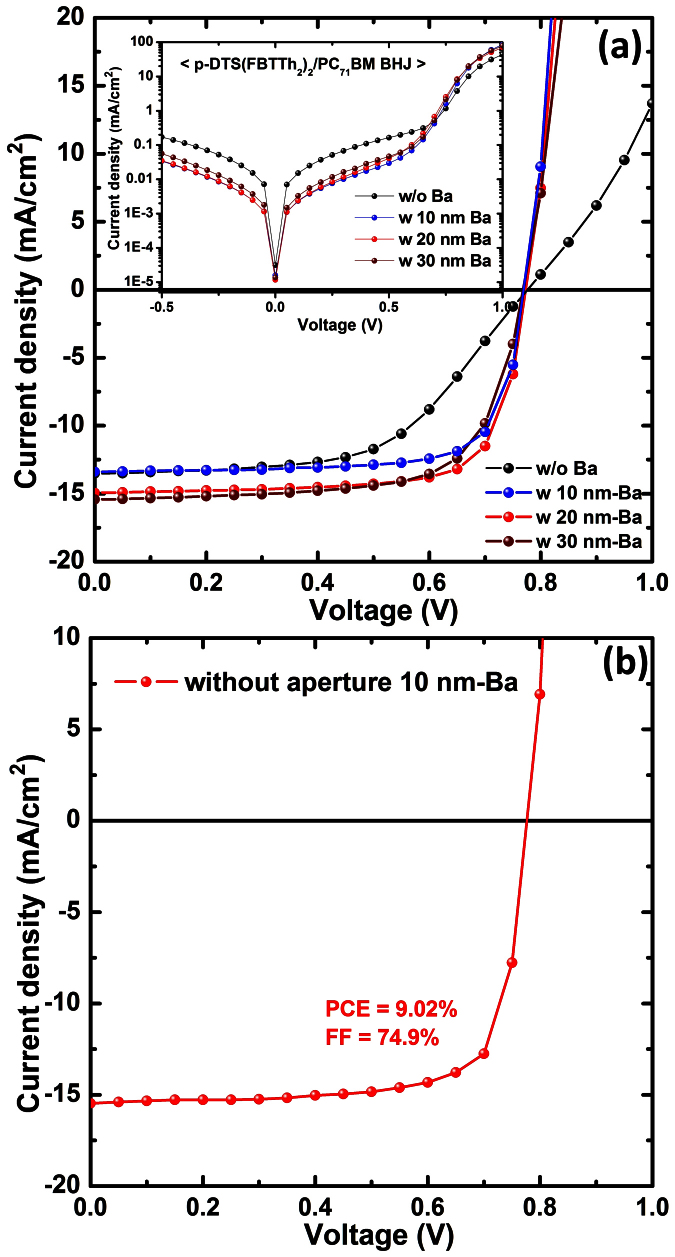

Figure 2a and Table 1 shows the current density versus voltage (J–V) characteristics of the SM BHJ solar cells under 100 mW/cm2 (AM 1.5 G) illumination and an aperture area of 4.5 mm2 with a device configuration ITO (20 Ω/sq)/PEDOT:PSS/p-DTS(FBTTh2)2:PC71 BM/(Ba)/Al with Ba interlayer thicknesses of 0 nm. 10 nm, 20 nm and 30 nm. The control device (without Ba interlayer) exhibited Jsc = 13.51 mA/cm2, Voc = 0.779 V, and a FF = 56%. These values correspond to a PCE = 5.86%. After inserting the Ba cathode layer (10 nm), the device performance improves to FF = 75.1%. and PCE = 7.78%. For similar thickness of Ca layer, the device exhibited Jsc = 13.90 mA/cm2, FF = 64.6% and a PCE = 7.01%. An increase in the thickness of Ba cathode interlayer to 20 nm improves the PCE to 8.57% with FF = 74.2%, whereas 20 nm Ca leads to a PCE = 7.58% with FF = 67.5%. Most of the increase in the performance of the 20 nm Ba device comes from the ≈10.7% and ≈32.5% enhancements in Jsc and FF values, respectively. A further increase in the Ba thickness to 30 nm, causes the FF to decrease to 68.8% with PCE = 8.13%, whereas 30 nm Ca gives PCE = 7.36% with FF = 62.7% (Table 1). Figure 2b and in () of the Table 1, the current density versus voltage (J–V) characteristics of p-DTS(FBTTh2)2/PC71BM BHJ (10 nm Ba) measured without aperture, is shown for comparison. The PCE jumped to 9.02% for 10 nm Ba, respectively. The Fill factor is not changed much. One needs to be cautious that in the absence of an aperture, the entire film is illuminated. Due to that, a significant number of charge carriers outside of the area of the electrode would also flow towards the electrode and contribute to the current and the actual area contributing to the photocurrent would be larger than the Al-electrode area. Therefore the PCE values can be exaggerated.

Figure 2.

J–V characteristics of the p-DTS(FBTTh2)2/PC71BM BHJ solar cells with various Ba thicknesses under AM 1.5 G irradiation at 100 mW/cm2 (a) with aperture and (inset) is the dark current. (b) without aperture.

Table 1. Device efficiency and electrical parameters of p-DTS(FBTTh2)2/PC71BM SM-BHJ solar cells without Ba and with different thicknesses of Ba layer.

| Thickness (nm) | Type of layer | VOC [V] | JSC [mA/cm2] | FF [%] | PCE [%] | Rs [Ωcm2] | Rsh [kΩcm2] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | - | 0.776 | 13.51 | 56.0 | 5.86 | 10.0 | 0.5 |

| (0.778) | (15.63) | (55.8) | (6.78) | (10.5) | (0.4) | ||

| 10 | Ba | 0.772 | 13.40 | 75.1 | 7.78 | 0.9 | 5.0 |

| (0.779) | (15.47) | (74.9) | (9.02) | (1.0) | (4.8) | ||

| Ca | 0.775 | 13.45 | 66.7 | 6.95 | 6.1 | 1.2 | |

| 20 | Ba | 0.773 | 14.96 | 74.2 | 8.57 | 1.2 | 10.6 |

| Ca | 0.778 | 14.21 | 67.1 | 7.41 | 2.4 | 1.8 | |

| 30 | Ba | 0.768 | 15.43 | 68.8 | 8.13 | 1.7 | 2.9 |

| Ca | 0.775 | 15.16 | 62.7 | 7.36 | 3.9 | 0.8 |

Values shown in the () are without aperture.

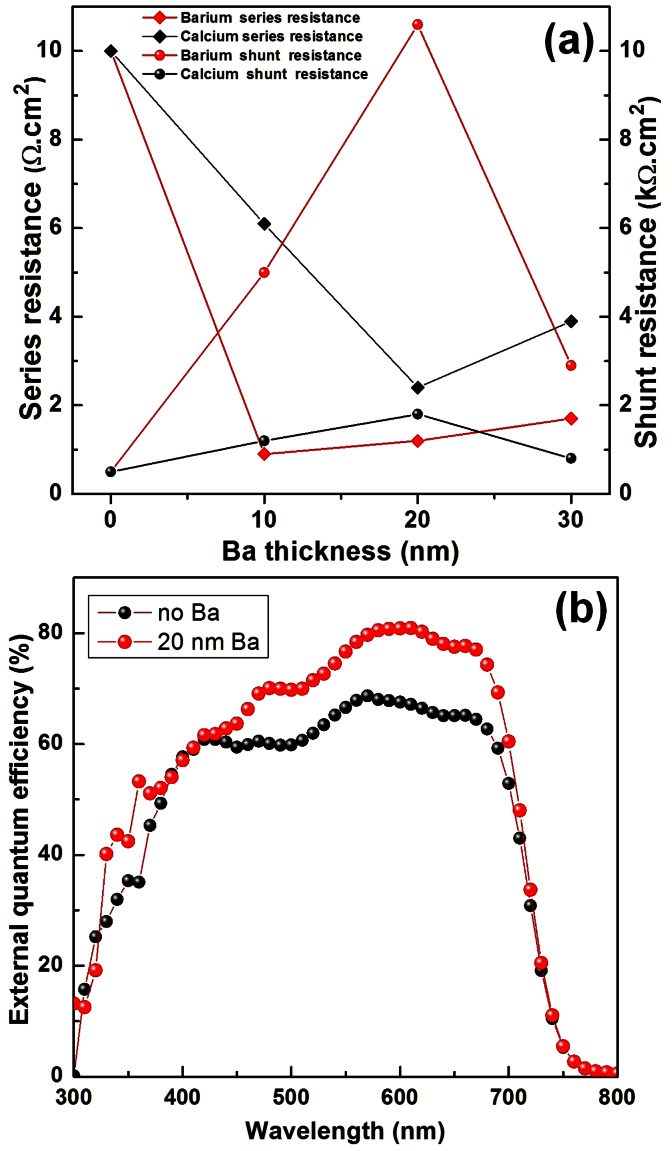

As shown in the Figure 2a (inset) and 3a, the insertion of the Ba layer (10 nm) reduces the series resistance from 10 Ωcm2 to 0.9 Ωcm2 and increases the shunt resistance from 0.5 kΩcm2 to 5 kΩcm2, which leads to 75.1% FF. for 20 nm Ba, the series resistance = 1.2 Ωcm2 and shunt resistance = 10.6 kΩcm2, are obtained, leading to PCE = 8.57%. A further increase in the thickness of Ba to 30 nm leads to a large increase in the series resistance to 1.2 Ωcm2 and decrease in the shunt resistance to 2.9 kΩcm2, leading to a drop in the PCE to 8.13%. Therefore, the resistance change due to the Ba layer plays pivotal role in increasing the FF and PCE. The dark J–V curves (inset of Figure 2a) also show excellent diode characteristics with very low leakage current and high rectification ratio (forward to reverse factor of approx. 100). The improvement in Jsc is also in agreement with the external quantum efficiency (EQE) measurements (Figure 3b). The EQE value exceeds 80% over the wavelength range 600 nm and 700 nm for devices with 20 nm Ba.

Figure 3.

(a) Electrical resistance parameters of the p-DTS(FBTTh2)2/PC71BM BHJ solar cells as a function of thickness. (b) External quantum efficiency (EQE) spectra of p-DTS(FBTTh2)2/PC71BM BHJ solar cells without Ba and with Ba 20 nm.

Discussion

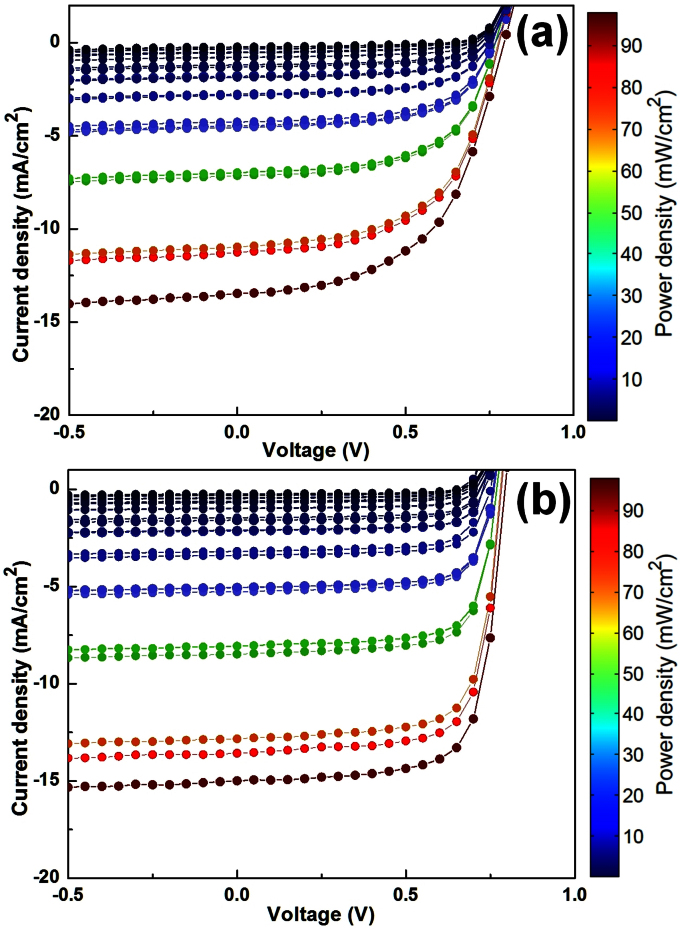

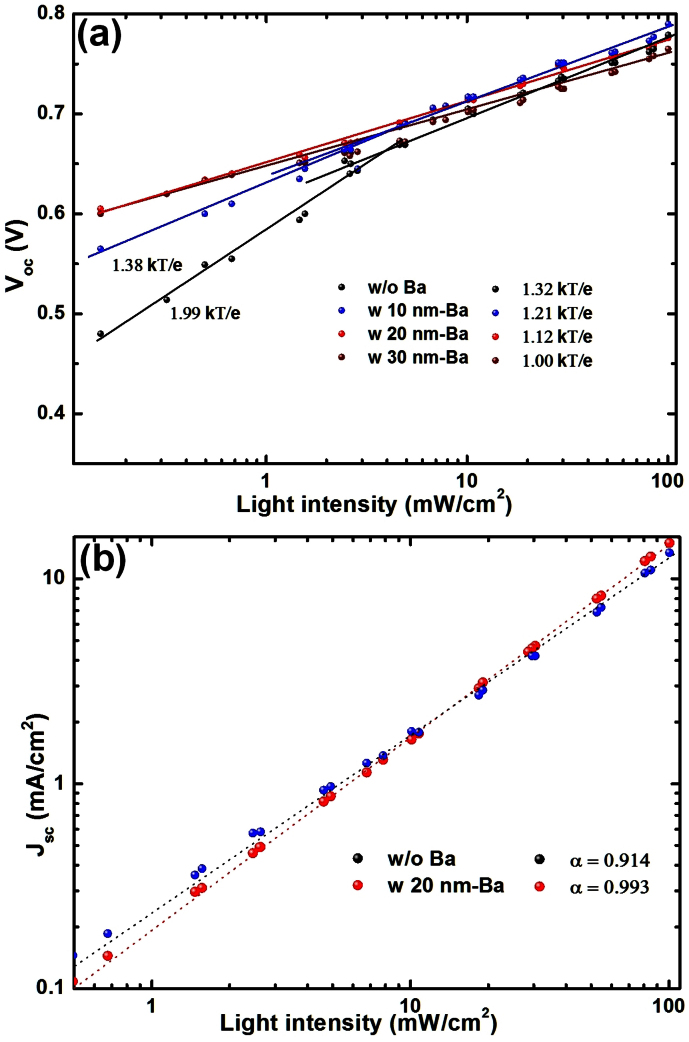

To understand the increased FF and Jsc, the recombination kinetics were probed by measurements of the light intensity dependence of the J–V characteristics29,30. Such studies are known to provide information on the relative importance of different recombination mechanisms such as Shockley-Read-Hall (SRH) monomolecular recombination and bimolecular recombination29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37. We measured the J–V characteristics in the SM BHJ solar cells at different illumination intensities (100 to 0.1 mW/cm2) without Ba and with different thicknesses of the Ba layer. Figures 4a, b show the J–V curve of the DTS(FBTTh2)2:PC71BM device without and with the 20 nm Ba layer, respectively. The Ba layer affects the shape of J–V curve which is strongly correlated with the recombination mechanism35. At open circuit (low external bias), bimolecular recombination is clearly dominant. Analysis of the recombination mechanism at short circuit is complicated by the simultaneous sweep-out during recombination. Because the sweep-out is approximately linear in intensity, recombination shows up only as a small deviation from linearity. With the Ba layer (Figure 4b), the photocurrent saturates quickly at low reversed biases: Nearly 100% of the photogenerated carriers are swept out prior to recombination. However, the current saturation rate is slower without the Ba layer (Figure 4a), and the photogenerated carries are not swept-out completely near Jsc. Thus, the Ba layer favors the sweep-out in competition with recombination, thus suppressing recombination and leading to higher FF.

Figure 4. J–V characteristics of p-DTS(FBTTh2)2:PC71BM solar cells with (a) 0 nm Ba & (b) 20 nm Ba, under various light intensities ranging from 100 mW/cm2 to 0.5 mW/cm2.

Insight into the recombination mechanism can be obtained by measuring Voc as a function of the light intensity29,37. At Voc, the photocurrent is zero, and all photogenerated carriers recombine within the cell. Thus, recombination studies at Voc can provide detailed information of various mechanisms. The Voc and light intensity (I) are correlated by the following expression

where nenh is proportional to the light intensity, e is the elementary charge, k is the Boltzman constant, T is temperature in Kelvin, ne and nh are the electron and hole densities in the fullerene and polymer domains at open circuit, and Nc is the effective density of states and Δ represents the relatively small band tailing to energy below the acceptor LUMO. Thus, for bimolecular recombination29

where I is the incident light intensity, This implies that the slope of Voc versus ln(I) is equal to kT/e for bimolecular recombination. In the case of monomolecular SRH recombination, a stronger dependence of Voc on the light intensity is observed and in that case ne and nh (at Voc) would each be proportional to the intensity and the slope of Voc versus ln(I) is equal to 2kT/e29.

Figure 5a shows the Voc versus light intensity relationship for devices with 0, 10 nm, 20 nm and 30 nm thick Ba layers. For SM BHJ without Ba, a strong dependence of Voc on light intensity is observed where the recombination at the open circuit is a combination of monomolecular (slope = 1.99 kT/e) and bimolecular processes (slope = 1.32 kT/e). The SRH recombination due to trap states can be clearly observed at low light intensities (≈1 mW/cm2), where the cell's efficiency becomes highly dependent on the bias and light intensity (slope = 1.99 kT/e). The use of 10 nm Ba layer significantly reduces the trap assisted recombination with reduced slopes of 1.21 kT/e and 1.38 kT/e at high and low light intensities, respectively. A further increase in the Ba thickness to 20 and 30 nm effectively blocked monomolecular recombination with the slope nearly equal to kT/e. This is consistent with the decreased series resistance after insertion of Ba layer (Table 1) which is a direct evidence of the role of Ba to improve the device performance. Now we look into the charge recombination kinetics at short circuit for SM BHJ and the 20 nm Ba SM BHJ. The Jsc can be correlated to illumination intensity (I) by,

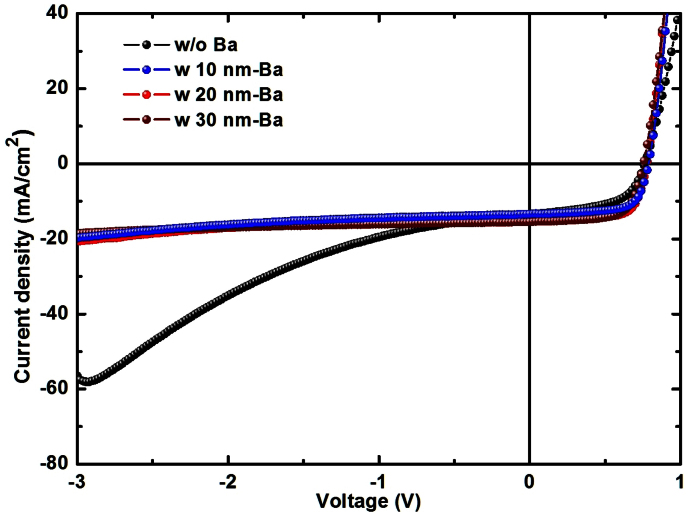

At short circuit, the bimolecular recombination should be minimum ( α ≈ 1) for maximum carrier sweep out. Any deviation from α ≈ 1 implies bimolecular recombination38,39,40. Figure 5b shows Jsc vs. I on log-log scale fitted using the power law described above. The fitting of the data yield α = 0.914 for SM BHJ, which can be attributed to bimolecular recombination. After 20 nm Ba deposition, α is 0.993, which imply that bimolecular recombination is close to minimum. This is correlated with observed increase in the shunt resistance (Table 1) and high collection probability at short circuit. Another factor that can also contribute to the faster sweep put is the internal voltage (Vint). In the dark (Inset of Figure 2a), the device with Ba layer shows a turn-on voltage of ≈0.65 V whereas it is only ≈0.45 V for control device, indicating a significant increase in the built-in potential (Vbi) due to the lower work function of the Ba (2.7 eV), compared to Al (4.3 eV). A larger Vbi means a larger Vint, which might also support the charge carriers escape shallow traps. The hole blocking efficiency for devices with 0, 10 nm, 20 nm and 30 nm thick Ba layer are shown in Figure 6. The devices without Ba layer nearly break down at 3 V reverse bias whereas devices with Ba show very stable photocurrent generation at reverse bias. All the encapsulated Ba devices are stable and show no sign of degradation over a period of two weeks.

Figure 5.

(a) The measured Voc of p-DTS(FBTTh2)2:PC71BM solar cells with Ba 0 nm, 10 nm, 20 nm and 30 nm as a function of illumination intensity (symbols), together with linear fits to the data (solid lines). (b) Measured Jsc of p-DTS(FBTTh2)2/PC71BM BHJ solar cells without Ba and with 20 nm Ba ploted against light intensity (symbol) on the logarithmic scale and fitted power law (line) yield α.

Figure 6. (a) J–V characteristics of the p-DTS(FBTTh2)2/PC71BM BHJ solar cells with Ba 0 nm, 10 nm, 20 nm and 30 nm under AM 1.5 G irradiation at 100 mW/cm2.

In conclusion, the Ba interlayer between the Aluminum and organic active layers significantly improve the FF and hence the PCE of the SM BHJ. The maximum increase in the FF was nearly 33% (FF = 75%) and the maximum increase in PCE was 46% (PCE = 8.6%), respectively. We attribute this improvement in the device performance to a decrease in the series resistance and an increase in the shunt resistance. Intensity dependence of current-voltage characteristics shows suppression of the trap assisted recombination at short circuit leads to increased charge collection. An increase in the built-in potential (Vbi) after insertion of the Ba layer due to the lower work function of Ba (2.7 eV), compared to Al (4.3 eV) further assists faster sweep-out. Ba shows excellent hole-blocking even at high baises and outperforms all the other reported cathode interlayers in improving the device fill factor.

Methods

Device fabrication

The SM-BHJ solar cells were prepared by several experimental steps. First the ITO substrate (20 Ω/sq) was cleaned by detergent, acetone and isopropyl alcohol with ultra-sonication. After exposing the cleaned ITO to the UV/ozone treatment for 15 min. to reform the surface, the hole transport material of PEDOT:PSS (Clevious PH) was spin-coated at 5000 rpm for 40 s to obtain the film thickness of ~30 nm. The p-DTS(FBTTh2)2:PC71BM (donor:acceptor) blend solution was prepared from the weight ratio of 60:40 and total 35 mg/ml in CB with 0.4 v% of DIO processing additive. After stirring overnight at 60°C, the blend was heated to 90°C for 15 min before spin casting. The BHJ film was obtained from spin casting the solution at 2000 rpm for 60 s. The coated BHJ films were baked to 80°C for 10 min to evaporate residual solvent. Before deposition, Ba was evaporated under vacuum condition of 4 × 10−6 torr without substrate for few minutes to remove any oxide impurity from its surface. After Ba deposition (10, 20, 30 nm), the Al cathode was deposited to ~100 nm at the same vacuum condition of 4 × 10−6 torr. The fabricated solar cells were encapsulated with epoxy and cover glass.

Device measurements

The J–V characteristics of the solar cells were measured by a Keithley 2400 sourcemeter unit. The light source was calibrated by using silicon reference cells with an AM 1.5 G solar simulator with an intensity of 100 mW/cm2. During the testing, an aperture with an area of 4.5 mm2 (total electrode size 5 mm2) was used to accurately measure the performance of solar cells. In order to test the solar cells under various light intensities, the intensity of the light was modulated with a series of two neutral density filters wheels of six filters apiece, allowing for up to 35 steps in intensity from 100 to 0.1 mW/cm2. The intensity of light transmitted through the filter was independently measured via a power meter. All solar cells were tested in ambient air.

Author Contributions

A.J.H. suggested the idea of the project. V.G. did device fabrication, measurement, data analysis and characterization with the support of A.K.K.K. and D.H.W. All authors actively participated in the discussion, and V.G. wrote the initial draft of the manuscript, A.J.H., G.C.B. and S.C. were involved in discussion, supervised the project and wrote the final draft of the manuscript. All the authors reviewed the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This research was carried out at UCSB with support from the Department of Energy under a grant titled “Charge Recombination, Transport Dynamics, and Interfacial Effects in Organic Solar Cells”; DOE #DE-FG02-08ER46535. V.G. thanks financial support from Indo-US Science and Technology Forum (IUSSTF), Award No. Indo-US Research Fellowship/2012-2013/26-2012. A.K.K.K. thanks Agency for Science Technology and Research (A*STAR) of Singapore for a postdoctoral fellowship.

References

- Yu G., Gao J., Hummelen J. C., Wudl F. & Heeger A. J. Polymer photovoltaic cells: Enhanced efficiencies via a network of internal donor-acceptor heterojunctions. Science 270, 1789–1791 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Li G. et al. High-efficiency solution processable polymer photovoltaic cells by self-organization of polymer blends. Nat Mater 4, 864–868 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Ma W., Yang C., Gong X., Lee K. & Heeger A. J. Thermally stable, efficient polymer solar cells with nanoscale control of the interpenetrating network morphology. Adv Funct Mater 15, 1617 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Li G., Zhu R. & Yang Y. Polymer solar cells. Nat Photon 6, 153–161 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao G., He Y. & Li Y. 6.5% Efficiency of polymer solar cells based on poly(3-hexylthiophene) and jndene-C60 bisadduct by device optimization. Adv Mater 22, 4355–4358 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z. et al. Simultaneous enhancement of open-circuit voltage, short-circuit current density, and fill factor in polymer solar cells. Adv Mater 23, 4636–4643 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y. et al. For the Bright Future–Bulk Heterojunction Polymer Solar Cells with Power Conversion Efficiency of 7.4%. Adv Mater 22, E135–E138 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y. et al. Solution-processed small-molecule solar cells with 6.7% efficiency. Nat Mater 11, 44–48 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Poll T. S., Love J. A., Nguyen T.-Q. & Bazan G. C. Non-basic high-performance molecules for solution-processed organic solar cells. Adv Mater 24, 3646–3649 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyaw A. K. K. et al. Efficient solution-processed small-molecule solar cells with inverted structure. Adv Mater 25, 2397–2402 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W. et al. Efficient small bandgap polymer solar cells with high fill factors for 300 nm thick films. Adv Mater 25, 2397–2402 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. H. et al. Bulk heterojunction solar cells with internal quantum efficiency approaching 100%. Nat Photon 3, 297–302 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H., Cho S., Roy A., Jung H.-T. & Heeger A. J. Enhanced diode characteristics of organic solar cells using titanium suboxide electron transport layer. Applied Physics Letters 96, 163303 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Li G., Chu C.-W., Shrotriya V., Huang J. & Yang Y. Efficient inverted polymer solar cells. Appl Phys Lett 88, 253503 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao D. W. et al. An inverted organic solar cell with an ultrathin Ca electron-transporting layer and MoO[sub 3] hole-transporting layer. Appl Phys Lett 95, 153304 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- White M. S., Olson D. C., Shaheen S. E., Kopidakis N. & Ginley D. S. Inverted bulk-heterojunction orgnaic photovoltaic device using a solution-derived ZnO underlayer. Appl Phys Lett 89, 143517 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Kyaw K. K. A. et al. Intensity dependence of curent-voltage characteristics and recombination in high-efficiency solution processeed small molecule solar cells. ACS Nano. 10.1021/nn401267s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D. H., Kyaw K. K. A., Gupta V., Bazan G. C. & Heeger A. J. enhanced efficiency parameters of solution processable small molecule solar cells depending on the ITO sheet resistance. Adv. Energy Mater. 10.1002/aenm.201300277. [Google Scholar]

- Brabec C. J., Shaheen S. E., Winder C., Sariciftci N. S. & Denk P. Effect of LiF/metal electrodes on the performance of plastic solar cells. Appl Phys Lett 80, 1288–1290 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Yang X. et al. Nanoscale morphology of high-performance polymer solar cells. Nano Lett 5, 579–583 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peumans P., Yakimov A. & Forrest S. R. Small molecular weight organic thin-film photodetectors and solar cells. J Appl Phys 93, 3693–3723 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Chang C.-C. et al. Effects of cathode buffer layers on the efficiency of bulk-heterojunction solar cells. Appl Phys Lett 96, 263506 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Yip H.-L., Hau S. K., Baek N. S., Ma H. & Jen A. K. Y. Polymer solar cells that use self-assembled-monolayer-modified ZnO/metals as cathodes. Adv Mater 20, 2376–2382 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Luo J. et al. Enhanced open-circuit voltage in polymer solar cells. Appl Phys Lett 95, 043301 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- He C. et al. Origin of the enhanced open-circuit voltage in polymer solar cells via interfacial modification using conjugated polyelectrolytes. J Mater Chem 20, 2617–2622 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Seo J. H. et al. Improved high-efficiency organic solar cells via incorporation of a conjugated polyelectrolyte interlayer. J Am Chem Soc 133, 8416–8419 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh S.-H. et al. Water-soluble polyfluorenes as an interfacial layer leading to cathode-independent high performance of organic solar cells. Adv Funct Mater 20, 1977–1983 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- He Z. et al. Enhanced power-conversion efficiency in polymer solar cells using an inverted device structure. Nat Photon 6, 591–595 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Cowan S. R., Roy A. & Heeger A. J. Recombination in polymer-fullerene bulk heterojunction solar cells. Phys Rev B 82, 245207 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Koster L. J. A., Kemerink M., Wienk M. M., Maturová K. & Janssen R. A. J. Quantifying bimolecular recombination losses in organic bulk heterojunction solar cells. Adv Mater 23, 1670–1674 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal S. K. et al. Geminate charge recombination in polymer/fullerene bulk heterojunction films and implications for solar cell function. J Am Chem Soc 132, 12440–12451 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shockley W. & Read W. T. Jr Statistics of the Recombinations of Holes and Electrons. Phys Rev 87, 835–842 (1952). [Google Scholar]

- Hall R. N. Electron-Hole recombination in germanium. Phys Rev 87, 387–387 (1952). [Google Scholar]

- Credgington D., Jamieson F. C., Walker B., Nguyen T.-Q. & Durrant J. R. Quantification of geminate and non-geminate recombination losses within a solution-processed small-molecule bulk heterojunction solar cell. Adv Mater 24, 2135–2141 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor C. M., Kim C., Neher D. & Nguyen T.-Q. Nongeminate recombination and charge transport limitations in diketopyrrolopyrrole-based solution-processed small molecule solar cells. Adv Funct Mater, 10.1002/adfm.201202643 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Mandoc M. M., Veurman W., Koster L. J. A., de Boer B. & Blom P. W. M. Origin of the reduced fill factor and photocurrent in MDMO-PPV:PCNEPV all-polymer solar cells. Adv Funct Mater 17, 2167–2173 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Koster L. J. A., Mihailetchi V. D., Ramaker R. & Blom P. W. M. Light intensity dependence of open-circuit voltage of polymer:fullerene solar cells. Appl Phys Lett 86, 123509 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Riedel I. et al. Effect of temperature and illumination on the electrical characteristics of polymer–fullerene bulk-heterojunction solar cells. Adv Funct Mater 14, 38–44 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Schilinsky P., Waldauf C. & Brabec C. J. Recombination and Loss Analysis in Polythiophene Based Bulk Heterojunction Photodetectors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 81 3885–3887 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Van Duren J. K. J. et al. Relating the Morphology of Poly(p-phenylene vinylene)/Methanofullerene Blends to Solar-Cell Performance. Advanced Functional Materials 14, 425–434 (2004). [Google Scholar]