Abstract

Non-equilibrium processes which convert chemical energy into mechanical motion enable the motility of organisms. Bundles of inextensible filaments driven by energy transduction of molecular motors form essential components of micron-scale motility engines like cilia and flagella. The mimicry of cilia-like motion in recent experiments on synthetic active filaments supports the idea that generic physical mechanisms may be sufficient to generate such motion. Here we show, theoretically, that the competition between the destabilising effect of hydrodynamic interactions induced by force-free and torque-free chemomechanically active flows, and the stabilising effect of nonlinear elasticity, provides a generic route to spontaneous oscillations in active filaments. These oscillations, reminiscent of prokaryotic and eukaryotic flagellar motion, are obtained without having to invoke structural complexity or biochemical regulation. This minimality implies that biomimetic oscillations, previously observed only in complex bundles of active filaments, can be replicated in simple chains of generic chemomechanically active beads.

Prokaryotic bacteria1 as well as eukaryotic sperm cells2,3 employ rhythmic flagellar beating for locomotion in viscous fluids. Bacterial flagella rotate rigidly in corkscrew fashion4,5, while spermatic flagella behave more like flexible oars6 with their beating mostly confined to a plane7,8,9. Oscillatory motility in clamped flagella can arise spontaneously and, with an unlimited supply of energy, can persist indefinitely without any external or internal regulatory pacemaker mechanism3,10. Autonomous motility as well as spontaneous beating due to hydrodynamic instabilities has been recently reproduced in vitro11,12, where a biomimetic active motor-microtubule assemblage has been shown to exhibit remarkable cilialike beating motion with hydrodynamic interactions (HI) playing a crucial role in synchronised oscillations11. Previous models13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24 analysing the mechanism behind flagellar beating have, in general, ignored the role of HI.

Here we study a minimal active filament model25 which, once clamped at one end, exhibits a variety of spontaneous beating phenomena in a three dimensional fluid. Our model filament consists of chemomechanically active beads (CABs) which convert chemical energy to mechanical work in viscous fluids. These CABs are connected through potentials that restricts extensibility and enforces semiflexibility and self-avoidance of the filament. The conversion of chemical energy to mechanical work within the fluid produces flows which do not add net linear or angular momentum to it and, thus, must be represented at low Reynolds numbers by force-free and torque-free singularities8,26,27,28,29,30. We model the activity of the beads by a stresslet singularity which produce a flow decaying as 1/r2. This stresslet contribution arises from chemomechanical activity, for instance the metachronal waves of ciliated organisms11, or from phoretic flows in synthetic catalytic nanorods31,32,33,34. For self-propelled particles, additional dipolar contributions generating flows decaying as 1/r3 are present, but are neglected here as they are subdominant to stresslet contributions. The equation of motion for the active filament25 incorporating the effects of nonlinear elastic deformations, active processes and HI is

where rn is the location of the n-th bead, fn is the total elastic force on the n-th bead, and  is stresslet tensor directed along the the local unit tangent tn. Here σ0 > 0 sets the scale of (extensile) activity. The monopolar Oseen tensor O and the dipolar stresslet tensor D respectively propagate the elastic and active contributions to the flow (details of model in Supplementary Text). Noise, of both chemomechanical and thermal origin, can be added to these equations, but are not considered here. We impose clamped boundary conditions at one end and solve the equation of motion through direct summation of the hydrodynamic Green's functions. For a filament of length L and bending modulus κ the dynamics is characterised by the dimensionless activity number

is stresslet tensor directed along the the local unit tangent tn. Here σ0 > 0 sets the scale of (extensile) activity. The monopolar Oseen tensor O and the dipolar stresslet tensor D respectively propagate the elastic and active contributions to the flow (details of model in Supplementary Text). Noise, of both chemomechanical and thermal origin, can be added to these equations, but are not considered here. We impose clamped boundary conditions at one end and solve the equation of motion through direct summation of the hydrodynamic Green's functions. For a filament of length L and bending modulus κ the dynamics is characterised by the dimensionless activity number  25.

25.

Results

Spontaneous oscillations

We briefly recall the mechanism behind hydrodynamic instabilities in active filaments25. Extensile activity in a straight filament produces flows with dipolar symmetry that point tangentially outward at the filament ends and normally inward at the filament midpoint. A spontaneous transverse perturbation breaks flow symmetry about the filament midpoint resulting in a net flow in the direction of the perturbation. The destabilising effect of the hydrodynamic flow is countered by the stabilising effect of linear elasticity for activity numbers  but leads to a linear instability for

but leads to a linear instability for  . This instability produces filament deformations which are ultimately contained by the non-linear elasticity producing autonomously motile conformations25. Here, the additional constraint imposed by the clamp transforms the autonomously motile states into ones with spontaneous oscillations. We perform numerical simulations of the active filament model to show that the interplay of hydrodynamic instabilities, non-linear elasticity, and the constraint imposed by the clamp leads to spontaneously oscillating states.

. This instability produces filament deformations which are ultimately contained by the non-linear elasticity producing autonomously motile conformations25. Here, the additional constraint imposed by the clamp transforms the autonomously motile states into ones with spontaneous oscillations. We perform numerical simulations of the active filament model to show that the interplay of hydrodynamic instabilities, non-linear elasticity, and the constraint imposed by the clamp leads to spontaneously oscillating states.

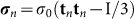

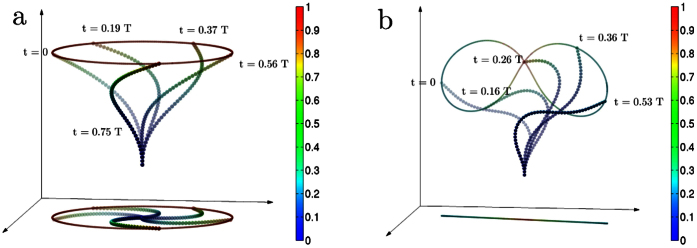

Numerical simulations of Eq. (1) reveal two distinct oscillatory states (Figs. 1a, 1b, Supplementary Fig. S3a, Supplementary Videos 1 and 2). The first of these, seen in the range  , is a state in which the filament rotates rigidly in a corkscrew-like motion about the axis of the clamp. This rotational corkscrew motion is reminiscent of prokaryotic flagellar beating4,5. We show this motion in Fig. 1a over one time period of oscillation together with the projection of the filament on the plane perpendicular to the clamp axis. A section of the three-dimensional flow in a plane containing the clamp axis is shown in Figs. 2a and 2b. The net flow points in the direction opposite to the filament curvature and the entire flow pattern co-rotates with the filament. In the second state, seen for

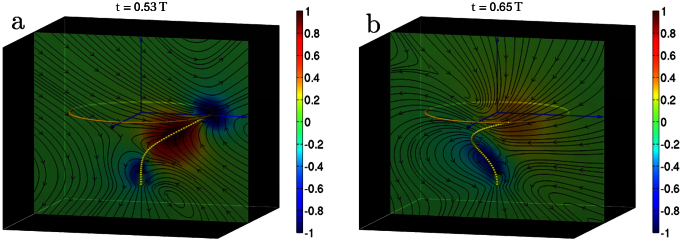

, is a state in which the filament rotates rigidly in a corkscrew-like motion about the axis of the clamp. This rotational corkscrew motion is reminiscent of prokaryotic flagellar beating4,5. We show this motion in Fig. 1a over one time period of oscillation together with the projection of the filament on the plane perpendicular to the clamp axis. A section of the three-dimensional flow in a plane containing the clamp axis is shown in Figs. 2a and 2b. The net flow points in the direction opposite to the filament curvature and the entire flow pattern co-rotates with the filament. In the second state, seen for  , the filament beats periodically in a two-dimensional plane containing the axis of the clamp, with waves propagating from the clamp to the tip. This flexible beating is reminiscent of eukaryotic flagellar motion2,3,7,9,10. We show this motion in Fig. 1b over one time period of oscillation together with the projection of the filament on the plane perpendicular to the clamp axis. The projection is now a line, showing that motion is confined to a plane. A section of the three-dimensional flow in the plane of beating is shown in Figs. 3a and 3b. Two distinct types of filament conformations of opposite symmetry are now observed, corresponding to different parity of the conformation with respect to the perpendicular bisector of the line joining the two end points. In the even conformation (Fig. 3a), the flow points in the direction opposite to the curvature as in the corkscrew state. However, in the odd conformation (Fig. 3b), the flow has a centre of vorticity at the point of inflection of the filament. This centre of vorticity moves up the filament and is shed at the tip at the end of every half cycle. The critical activities scale as

, the filament beats periodically in a two-dimensional plane containing the axis of the clamp, with waves propagating from the clamp to the tip. This flexible beating is reminiscent of eukaryotic flagellar motion2,3,7,9,10. We show this motion in Fig. 1b over one time period of oscillation together with the projection of the filament on the plane perpendicular to the clamp axis. The projection is now a line, showing that motion is confined to a plane. A section of the three-dimensional flow in the plane of beating is shown in Figs. 3a and 3b. Two distinct types of filament conformations of opposite symmetry are now observed, corresponding to different parity of the conformation with respect to the perpendicular bisector of the line joining the two end points. In the even conformation (Fig. 3a), the flow points in the direction opposite to the curvature as in the corkscrew state. However, in the odd conformation (Fig. 3b), the flow has a centre of vorticity at the point of inflection of the filament. This centre of vorticity moves up the filament and is shed at the tip at the end of every half cycle. The critical activities scale as  and

and  , obtained from a Bayesian parameter estimation of data shown in Fig. S3b. The critical values depend only on the ratio σ0/κ, and not on σ0 and κ individually, as is clearly seen in Fig. 4a.

, obtained from a Bayesian parameter estimation of data shown in Fig. S3b. The critical values depend only on the ratio σ0/κ, and not on σ0 and κ individually, as is clearly seen in Fig. 4a.

Figure 1. Biomimetic oscillations of the clamped filament plotted at different times over an oscillation period T.

In (a) we see rigid aplanar corkscrew rotation for  while in (b) we see flexible planar beating for

while in (b) we see flexible planar beating for  . The colour of the beads as well as the trace of the tip correspond to individual instantaneous monomer speeds. The colourbars are normalised by the maximum speed.

. The colour of the beads as well as the trace of the tip correspond to individual instantaneous monomer speeds. The colourbars are normalised by the maximum speed.

Figure 2. Flow fields of rigid aplanar corkscrew rotation at two different instants of the oscillation cycle.

The colour indicates the signed magnitude of the velocity field perpendicular to the plane normalised by its maximum.

Figure 3. Flow fields of flexible planar beating at two instants of the oscillation cycle.

The colour indicates the magnitude of the velocity in the plane normalised by its maximum.

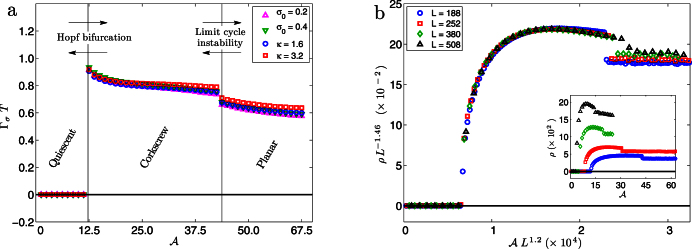

Time period and amplitude scaling

The physical parameters determining the time period T of the oscillatory states are the active stresslet σ0, the bending modulus κ, the fluid viscosity η and the filament length L. Remarkably, variations of T in this four-dimensional parameter space collapse, when scaled by the active relaxation rate Γσ = σ0/ηL3, to a one-dimensional scaling curve of the form  . We show the data collapse at fixed L and varying relative activity σ0/κ in Fig. 4a while the scaling with system size is shown in Supplementary Fig. S2a. Our best estimates for the exponents, obtained from Bayesian regression, are α = 1.3 and β = −1.2 (Supplementary Fig. S2a). Qualitatively, at fixed relative activity the oscillation frequency decreases with increasing L, while at a constant L the oscillation frequency increases with increasing relative activity. This is in agreement with a simple dimensional estimate of the time period T ~ ηL3/σ0. For active beads with a stresslet of σ0 ~ 6 × 10–18 Nm in a filament of length L ~100 μm, our estimate of the time period gives a value of 170 s, which agrees in order of magnitude with experiment11. The amplitude of oscillation ρ obeys a similar scaling relation with α = –1.46, β = –1.2 (Fig. 4b, main panel). At fixed relative activity, ρ increases with increasing L, while at fixed L, it increases and then saturates at large relative activity. The amplitude in the planar beating state is marginally smaller than in the corkscrew rotating state (Fig. 4b, inset).

. We show the data collapse at fixed L and varying relative activity σ0/κ in Fig. 4a while the scaling with system size is shown in Supplementary Fig. S2a. Our best estimates for the exponents, obtained from Bayesian regression, are α = 1.3 and β = −1.2 (Supplementary Fig. S2a). Qualitatively, at fixed relative activity the oscillation frequency decreases with increasing L, while at a constant L the oscillation frequency increases with increasing relative activity. This is in agreement with a simple dimensional estimate of the time period T ~ ηL3/σ0. For active beads with a stresslet of σ0 ~ 6 × 10–18 Nm in a filament of length L ~100 μm, our estimate of the time period gives a value of 170 s, which agrees in order of magnitude with experiment11. The amplitude of oscillation ρ obeys a similar scaling relation with α = –1.46, β = –1.2 (Fig. 4b, main panel). At fixed relative activity, ρ increases with increasing L, while at fixed L, it increases and then saturates at large relative activity. The amplitude in the planar beating state is marginally smaller than in the corkscrew rotating state (Fig. 4b, inset).

Figure 4. Variation of the scaled timeperiod ΓσT of filament beating with  plotted for various values of κ and σ0 with L = 188, and (b, main panel) variation of the scaled amplitude L–1.46ρ with

plotted for various values of κ and σ0 with L = 188, and (b, main panel) variation of the scaled amplitude L–1.46ρ with  plotted for various lengths L with κ = 1.6.

plotted for various lengths L with κ = 1.6.

In (a) we show the appearance of spontaneous oscillations in the filament at  corresponding to rigid corkscrew rotation, followed by a transition at

corresponding to rigid corkscrew rotation, followed by a transition at  to flexible planar beating. In (b, inset) we show the increase in the unscaled amplitude with length.

to flexible planar beating. In (b, inset) we show the increase in the unscaled amplitude with length.

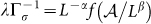

Linear Stability and Hopf Bifurcation

To better understand the nature of the hydrodynamic instability and the transition to spontaneous oscillation we performed a linear stability analysis35 of the straight filament. In absence of activity,  , all eigenvalues of the Jacobian are real and negative and the filament has an overdamped relaxation to equilibrium. With increasing

, all eigenvalues of the Jacobian are real and negative and the filament has an overdamped relaxation to equilibrium. With increasing  , the two largest real eigenvalue pairs approach, converge, and become complex conjugate pairs. This corresponds to a transition from a stable node to a stable focus where the response changes from being overdamped to underdamped. The analysis reveals that the balance between hydrodynamic flow and linear elasticity has a non-monotonic variation. While the general trend is towards slower relaxations with increasing

, the two largest real eigenvalue pairs approach, converge, and become complex conjugate pairs. This corresponds to a transition from a stable node to a stable focus where the response changes from being overdamped to underdamped. The analysis reveals that the balance between hydrodynamic flow and linear elasticity has a non-monotonic variation. While the general trend is towards slower relaxations with increasing  corresponding to the greater relative strength of the hydrodynamic flow, this is reversed in a small window of activity where the increasing activity produces faster relaxations. This can be clearly seen in Fig. 5a and Fig. S1a, where the rate of relaxation is given by the magnitude of the real part of the largest eigenvalue. With further increase of

corresponding to the greater relative strength of the hydrodynamic flow, this is reversed in a small window of activity where the increasing activity produces faster relaxations. This can be clearly seen in Fig. 5a and Fig. S1a, where the rate of relaxation is given by the magnitude of the real part of the largest eigenvalue. With further increase of  the complex eigenvalues approach the imaginary axis monotonically, crossing them at a critical value

the complex eigenvalues approach the imaginary axis monotonically, crossing them at a critical value  (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Figs. S1a and S1b, and Supplementary Video 3). Through this supercritical Hopf bifurcation, the stable focus flows into the limit cycle corresponding to the corkscrew rotation. The value of

(Fig. 5a, Supplementary Figs. S1a and S1b, and Supplementary Video 3). Through this supercritical Hopf bifurcation, the stable focus flows into the limit cycle corresponding to the corkscrew rotation. The value of  obtained from the linear stability analysis is in perfect agreement with that obtained from numerical simulation. As with the time-period and amplitude, the eigenvalues λ of the Jacobian obey scaling relations

obtained from the linear stability analysis is in perfect agreement with that obtained from numerical simulation. As with the time-period and amplitude, the eigenvalues λ of the Jacobian obey scaling relations  with α = 1.2 and β = –1.2.

with α = 1.2 and β = –1.2.

Figure 5. Variation of the largest scaled eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix (a) including HI and (b) excluding HI.

In (a) we see the transition from a stable node to a stable focus followed by a supercritical Hopf bifurcation from quiescence to a limit cycle. In (b) we see only a stable quiescent state. In the absence of HI the eigenvalue scaling is completely determined by  . Comparing (a) and (b) it is clear that hydrodynamic instabilities due to HI are the main mechanism for spontaneous oscillations. (a) also shows that the rate of relaxation, given by the magnitude of the real part of the largest eigenvalue, decreases as we approach the bifurcation from below.

. Comparing (a) and (b) it is clear that hydrodynamic instabilities due to HI are the main mechanism for spontaneous oscillations. (a) also shows that the rate of relaxation, given by the magnitude of the real part of the largest eigenvalue, decreases as we approach the bifurcation from below.

Importance of HI

To ascertain the importance of HI, we repeat the stability analysis on a local limit of our model. Here, the long-ranged contributions to the hydrodynamic flow from both elasticity and activity are neglected and only their short-ranged effects are retained (see Supplementary Text). We find that all eigenvalues remain real and negative for activity numbers corresponding to an order of magnitude greater than  , reflecting the stability of the quiescent state in the absence of HI (Fig. 5b).

, reflecting the stability of the quiescent state in the absence of HI (Fig. 5b).

Discussions

Our work shows that simple chains of CABs, for instance of synthetic catalytic nanorods31,32,33,34, can show the spontaneous beating obtained previously in more complex systems like self-assembled motor-microtubule mixtures11 or externally actuated artificial cilia36,37,38,39. We emphasise that an experimental realisation of our system requires neither external actuation nor self-propulsion. The only chemomechanical requirement is that the CABs produce force-free and torque-free dipolar flows in the fluid. This makes them an attractive candidate for biomedical applications like targetted drug delivery. Our detailed prediction for the spatiotemporal dynamics of the hydrodynamic flows can be experimentally verified using particle imaging velocimetry40.

In summary, we have shown that a minimal filament model which includes elasticity, chemomechanical activity and HI, exhibits spontaneous emergent biomimetic behaviour reminiscent of the rhythmic oscillations of various prokaryotic and eukaryotic flagella1,2,3,4,5,6,7,9. Our results lead us to conclude that hydrodynamic instabilities due to internal active stresses are sufficient to induce spontaneous biomimetic beating in a clamped chemomechanically active filament.

Methods

We calculate the RHS of Eq. (1) by a direct summation of the hydrodynamic Green's functions. Clamped boundary conditions are implemented at one end by fixing the position of the first particle and allowing the second particle to move only along the tangential direction. The equation of motion is integrated using a variable step method as implemented in ODE15s in Matlab. The hydrodynamic flows fields are obtained on a regularly spaced Eulerian grid by summing the individual contributions from each of the N particles. The linear stability analysis is performed by first numerically integrating the equations of motion to obtain the fixed point, then numerically evaluating the 3 N × 3 N Jacobian matrix at the fixed point, and finally computing the eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix numerically. Simulations are carried out for different filament lengths L with bead numbers upto N = 128. The equilibrium bond length is taken to be b0 = 4. We choose κ in the range 0.0 to 1.0 and σ0 in the range 0.0 to 0.5. The initial condition is a random transverse perturbation applied to every particle. Random perturbations in the longitudinal direction relaxes at a much faster time-scale due to the stretching potential. The total integration time is typically 10Γσ–1, where Γσ = σ0/ηL3 is the active relaxation rate, and η is the viscosity, taken to be 1/6.

Author Contributions

R.A. and P.B.S.K. designed research. A.L., R.S., S.G. and G.J. performed research. S.G., R.A., R.S. and P.B.S.K. wrote the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Hydrodynamic instabilities provide a generic route to spontaneous biomimetic oscillations in chemomechanically active filaments : Supplementary Information

Aplanar corkscrew-like rigid rotation of clamped active filament with flowfield

Planar flexible periodic beating of clamped active filament with flowfield

Hopf bifurcation in clamped active filament

Acknowledgments

Financial support from PRISM II, Department of Atomic Energy, Government of India and computing resources through HPCE, IIT Madras and Annapurna, IMSc are gratefully acknowledged. We thank M. E. Cates, Z. Dogic, D. Frenkel, G. Baskaran, I. Pagonabarraga, and R. Simon for helpful discussions, and P. V. Sriluckshmy for help with Bayesian analysis.

References

- Jahn T. L. & Bovee E. C. Movement and locomotion of microorganisms. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 19, 21–58 (1965). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray J. The movement of sea-urchin spermatozoa. J. Exp. Biol. 32, 775–801 (1955). [Google Scholar]

- Lindemann C. B. & Rikmenspoel R. Sperm Flagella: Autonomous Oscillations of the Contractile System. Science 175, 337–338 (1972). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg H. C. & Anderson R. A. Bacteria Swim by Rotating their Flagellar Filaments. Nature 245, 380–382 (1973). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg H. C. The rotary motor of bacterial flagella. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 72, 19 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell E. M. Life at low Reynolds number. Am. J. Phys. 45, 3–11 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- Brokaw C. J. Non-sinusoidal bending waves of sperm flagella. J. Exp. Biol. 43, 155–169 (1965). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennen C. & Winet H. Fluid mechanics of propulsion by cilia and flagella. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech 9, 339–938 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- Brokaw C. J. Microtubule sliding in swimming sperm flagella: direct and indirect measurements on sea urchin and tunicate spermatozoa. J. Cell. Biol. 114, 1201–1215 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimura M. & Okuno M. Requirement of the fixed end for spontaneous beating in flagella. J. Exp. Biol. 209, 1336–1343 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez T., Welch D., Nicastro D. & Dogic Z. Cilia-Like Beating of Active Microtubule Bundles. Science 333, 456 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez T., Chen D. T. N., DeCamp S. J., Heymann M. & Dogic Z. Spontaneous motion in hierarchically assembled active matter. Nature 491, 431–434 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machin K. E. Wave propagation along flagella. J. Exp. Biol. 35, 796–806 (1958). [Google Scholar]

- Brokaw C. J. Bend propagation by a sliding filament model for flagella. J. Exp. Biol. 55, 289–304 (1971). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lighthill J. Flagellar hydrodynamics : the John von Neumann lecture. SIAM Rev. 18, 161–230 (1976). [Google Scholar]

- Hines M. & Blum J. J. Bend propagation in flagella. I. Derivation of equations of motion and their simulation. Biophys. J. 23, 41–57 (1978). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueron S. & Liron N. Ciliary motion modeling, and dynamic multicilia interactions. Biophys. J. 63, 1045–1058 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindemann C. B. A “Geometric Clutch” Hypothesis to Explain Oscillations of the Axoneme of Cilia and Flagella. J. Theor. Biol. 168, 175–189 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- Camalet S., Jülicher F. & Prost J. Self-organized beating and swimming of internally driven filaments. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 1590–1593 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Camalet S. & Jülicher F. Generic aspects of axonemal beating. New J. Phys. 2, 24 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Dillon R. & Fauci L. An integrative model of internal axoneme mechanics and external fluid dynamics in ciliary beating. J. Theor. Biol. 207, 415–430 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedel-Kruse I. H., Hilfinger A., Howard J. & Jülicher F. How molecular motors shape the flagellar beat. HFSP journal 1, 192–208 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi N. et al. Buckling, stiffening, and negative dissipation in the dynamics of a biopolymer in an active medium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106, 19776–19779 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spagnolie S. E. & Lauga E. The optimal elastic flagellum. Phys. Fluids 22, 031901 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Jayaraman G. et al. Autonomous Motility of Active Filaments due to Spontaneous Flow-Symmetry Breaking. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 158302 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake J. R. A spherical envelope approach to ciliary propulsion. J. Fluid Mech. 46, 199–208 (1971). [Google Scholar]

- Lauga E. & Powers T. R. The hydrodynamics of swimming microorganism. Rep. Prog. Phys. 72, 096601 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswamy S. The Mechanics and Statistics of Active Matter. Annu. Rev. Condens. Mat. Phys. 1, 323–345 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Cates M. E. & MacKintosh F. C. Active soft matter. Soft Matter 7, 3050–3051 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti M. C. et al. Soft Active Matter. arXiv:1207.2929 (2012).

- Paxton W. F. et al. Catalytic nanomotors: Autonomous movement of striped nanorods. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 13424–13431 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicario J. et al. Catalytic molecular motors: fuelling autonomous movement by a surface bound synthetic manganese catalase. Chem. Commun. 31, 3936–3938 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozin G. A., Manners I., Fournier-Bidoz S. & Arsenault A. Dream nanomachines. Adv. Mater. 17, 3011–3018 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Catchmark J. M., Subramanian S. & Sen A. Directed rotational motion of microscale objects using interfacial tension gradients continually generated via catalytic reactions. Small 1, 202–206 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strogatz S. H. Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos (Addison-Wesley, Reading, 1994). [Google Scholar]

- Dreyfus R. et al. Microscopic artificial swimmers. Nature 437, 862–865 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans B. et al. Magnetically actuated nanorod arrays as biomimetic cilia. Nano Lett. 7, 1428–1434 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilfan M. et al. Self-assembled artificial cilia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107, 1844–1847 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coq N. et al. Collective beating of artificial microcilia. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 14501 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drescher K., Goldstein R. E., Michel N., Polin M. & Tuval I. Direct measurement of the flow field around swimming microorganisms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 168101 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Hydrodynamic instabilities provide a generic route to spontaneous biomimetic oscillations in chemomechanically active filaments : Supplementary Information

Aplanar corkscrew-like rigid rotation of clamped active filament with flowfield

Planar flexible periodic beating of clamped active filament with flowfield

Hopf bifurcation in clamped active filament