Abstract

Background:

Parkinsonism is known to be associated with clinically significant impairments on an array of cognitive deficits. The degree of impairment is dependent not only on the course of the disease, but also on other bio-social factors. The objective of the present study was to examine the cognitive dysfunction in non-demented idiopathic Parkinson's disease (IPD) in relation to age, stage of disease, and educational level in a sample in Kolkata, India.

Materials and Methods:

The sample consisted of 51 (42 males, 9 females) right-handed patients suffering from non-demented IPD, of age between 40 and 82 years. Data were collected during on-phase medication by using the Kolkata Cognitive Screening Battery. Data were analyzed using means, standard deviations, and multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVA).

Results and Conclusion:

The patients with IPD were impaired in comparison to the available normative data in almost all aspects of cognitive functioning and higher order mental processes. With increasing age, the patients showed greater impairment in delayed memory and recognition task. Patients of more severe stage showed greater impairment in MMSE, delayed recall, and information. Those with lower education had more impaired visuoconstructional ability, information, comprehension, similarities, and arithmetic.

Keywords: Cognitive functions, Idiopathic Parkinson's disease, Kolkata cognitive screening battery

Idiopathic Parkinson's disease (IPD) is a distinctive progressive disorder characterized clinically by tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia, and abnormal postural reflexes, and pathologically by nerve cell loss in the substantia nigra and presence of intra-neuronal inclusion bodies called Lewy Bodies (LB). Parkinson's disease has been found to be associated with clinically significant impairments on an array of mental functions ranging from subtle deficits in specific cognitive domains to overt and frank dementia.[1–3] Cronin-Golomb et al. found that the patients with IPD show impairments in deductive reasoning, problem solving, and other conceptual abilities, though social awareness and knowledge components remain intact.[4] Zakharov and Iakhno also found pronounced memory impairment and speech disorders in IPD.[5] The cognitive dysfunction in IPD has been attributed to impairment in fronto-basal ganglia circuitry.[6,7]

Factors influencing cognitive impairment in IPD have been studied. Some studies indicated that the cognitive dysfunctions are dependent on age of the patient and stage of the disease. Aarsland and Larsen observed that 1–2 years after the onset of disease, overall deterioration occurs; depression, anxiety, and apathy become evident, along with reduced cognitive performance and quality of life.[8] Green et al., using multiple neuropsychological measures that related to overall motor abnormality, found poorer performance and increased bradykinesia with older age and longer disease duration, presumably due to the changes in dorsolateral prefrontal regions participating in basal ganglia thalamocortical circuits.[9] In India, Ray et al. found that everyday abilities deteriorate with severity of parkinsonism but not with advanced age.[10] They also found that family and community relations were not significantly affected with advancement of the disorder, perhaps due to close family and social tie-up among Indians, thus implying a cultural component in deterioration.

The effects of education on deterioration of cognitive functioning have also been studied. Longer years of education are generally associated with lesser probability of dementia and less impairment in general cognitive functions, and specifically, higher order activities.[11,12] However, Parashos et al. observed that those with higher education required more early symptomatic treatment for parkinsonism, probably because they were often appointed in jobs requiring greater demand on cognitive functioning.[13]

While a few reports on the neurological substratum related to general cognitive deterioration in non-demented parkinsonism in India are available,[10,14–16] the detailed understanding of cognitive impairment in Indian patients with IPD is still inadequate. Bhatia and Gupta highlighted the need for psychological rehabilitation of Indian patients with parkinsonism.[17] Sowmini and De-Vries discussed the ethical issues and general negligence of patients with parkinsonism in Kerala.[18]

The objective of the present study is to scrutinize the nature of deterioration in cognitive functioning with increasing age, advancing stage of disease, and as a function of education to provide guidelines for geriatric care of the IPD patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample

The sample consisted of 51 right-handed non-demented patients between 40 and 80 years, diagnosed with IPD. They were presenting at least three cardinal signs of the disorder (bradykinesia, rest tremor and rigidity). There were 42 males and 9 females with mean (SD) age of 53 years (±9.58). Their educational level ranged from being literate to post graduation. Among them, 33 were employed and 18 were retired. All of them were under the levodopa medication for at least 12 months. The sample was taken from the Movement Disorder Clinic, Department of Neurology, at Bangur Institute of Neuroscience and Psychiatry, Kolkata, India.

Those with evidence of parkinsonism plus syndrome (PPS), or secondary or drug-induced Parkinson's disease were excluded. Other exclusion criteria were IPD of less than 1 year duration, lack of response to levodopa, vertical gaze abnormality, early dementia, ataxia and autonomic neuropathy as evident from postural dizziness, erectile impotency and sweating disturbances, clinical depression and severe impairment of daily activities as evaluated from the information battery.

Tools

Cognitive Information Battery by Das et al. for obtaining demographic and behavioral information relevant to cognitive impairment.[19]

Kolkata Cognitive Screening Battery (KCSB) initially used by Ganguly et al. and validated among urban population in Bengali and Hindi speaking population.[19,20] Field-testing of KCSB was done to evaluate intra- and inter-rater reliability and the values for different sub-tests ranged from 0.77 to 0.99. The final battery consisted of 10 sub-tests among which the following 8 sub-tests have been used in this study: verbal fluency tests for categories, naming tests, Bengali validated mental status examination, calculation, word list memory task, delayed word list memory task, delayed recognition word task, and visuoconstructional ability. The subscales of depression and activities of daily life were not used in the present study as the subjects with notable depression and severe impairment of everyday functioning were excluded.

Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS): Four verbal sub-tests from WAIS were used to assess higher mental functioning. These sub-tests were information, comprehension, similarities, and arithmetic.

-

Hoehn and Yahr Staging of Disease: This scale was developed by Hoehn and Yahr in 1967. The patients are evaluated on a 7-point scale by the clinicians.[21]

0 = No sign of disease

1 = Unilateral disease

1.5 = Unilateral plus axial involvement

2 = Bilateral disease, without impairment or balance

2.5 = Mild bilateral disease, with recovery on pull test

3 = Mild to moderate bilateral disease, some postural instability, physically independent

4 = Severe disability; still able to work or stand unassisted

Procedure

Data were collected from a specific hospital in Kolkata. Informed consent was taken from all the patients and their family members. The patients were diagnosed with IPD without dementia and identified as non-depressed by the attending neurologists according to DSM IV criteria. Patients were examined during on-phase medication (on Levodopa and Carbidopa combination. Initially, the Cognitive Information Battery was administered. Then, with the help of the attending neurologist, the Hoehn and Yahr Staging of Disease, KCSB, and the four verbal sub-tests from WAIS were applied. Approximately 90 min were required for each patient to complete the whole protocol.

Analyses

To determine the effects of age, stage, and education, the sample was divided into subgroups. Three age groups were identified, namely below 50 years, 50–59 years, and 60 years and above. Three groups in terms of Hoehn and Yahr (HY) staging were identified, namely early (rated as 1 or 1.5 on HY scale), middle (rated as 2 or 2.5 on HY scale), and advanced (rated as 3 or 4 on HY scale). The sample was further divided into three groups in terms of educational level. These were lower (below class V), middle (class V to class X), and upper (above class X).

Statistical analyses were done using descriptive statistics, “Z” tests, and multivariate analyses of variance. Since the number of participants was small, the interaction of age, stage, and education was not calculated, but separate analysis of the effects of each of these variables on the cognitive functioning was done.

RESULTS

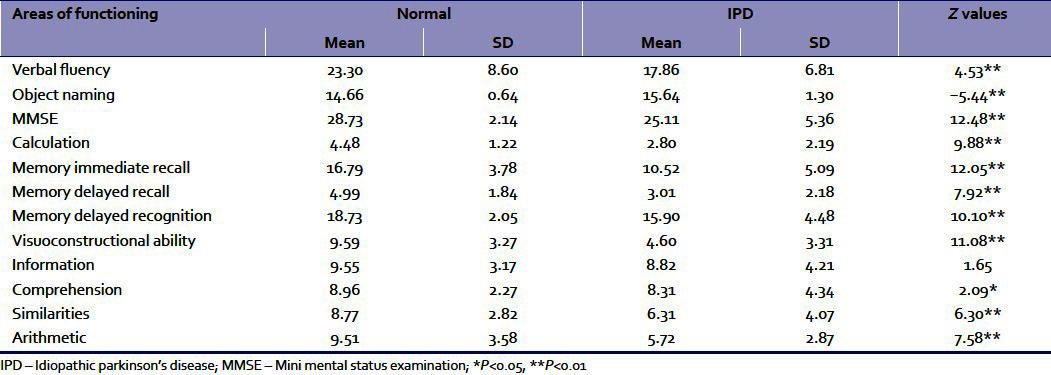

The means and standard deviations of the eight sub-tests of KCSB were calculated. These were compared with the normative values obtained in the original article by Das et al. (2006) on 745 elderly persons.[19] The “Z” tests were done to determine whether the obtained mean values for the functions differed significantly from the mean values of the population [Table 1].

Table 1.

Z values for testing the significance of difference between the normal and IPD groups in different areas of functioning

Effects of age

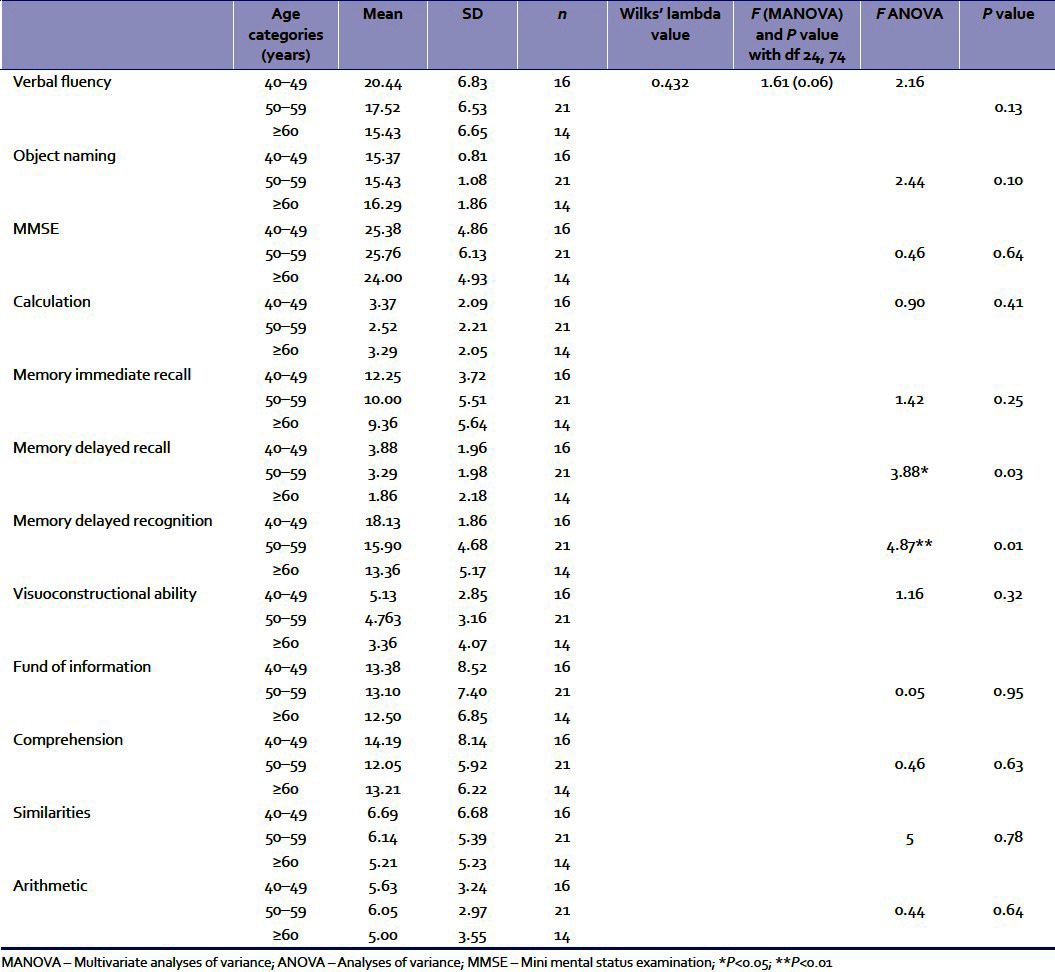

Subsequently, the effects of age were considered. The means and standard deviations of the three age groups (40–49 years, 50–59 years, and 60 years and above) were calculated. Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted with age as an independent variable and the cognitive functions as a dependent variable.

Table 2 indicates that there is no significant effect of age categories on the dependent variables taken in combination. This implies that at least for the age range taken in this study, age may not be a highly significant factor for cognitive decline in general. However, there remains a possibility that some of the specific variables may be affected by age. Therefore, univariate ANOVAs were conducted separately for each cognitive variable. Results imply that age turned out to be a significant variable only for delayed recall and delayed recognition [Table 2].

Table 2.

The means and SDs of the three age groups (40–49 years, 50–59 years, and ≥60 years) for the cognitive functions and results of MANOVA and ANOVAs

Subsequently, multiple comparisons between each age group in terms of these two dependent variables were done with Tukey's post hoc tests. The results revealed that for both delayed recall and recognition memory, the mean differences between the <50 years age group and 50–59 years age group were not statistically significant. However, a significant difference between the 50–59 years age group and the >60 years age group was obtained. For delayed memory, the difference of 2.02 was significant at 0.024 level. For the delayed recognition memory test, the difference of 4.77 was significant at 0.008 level.

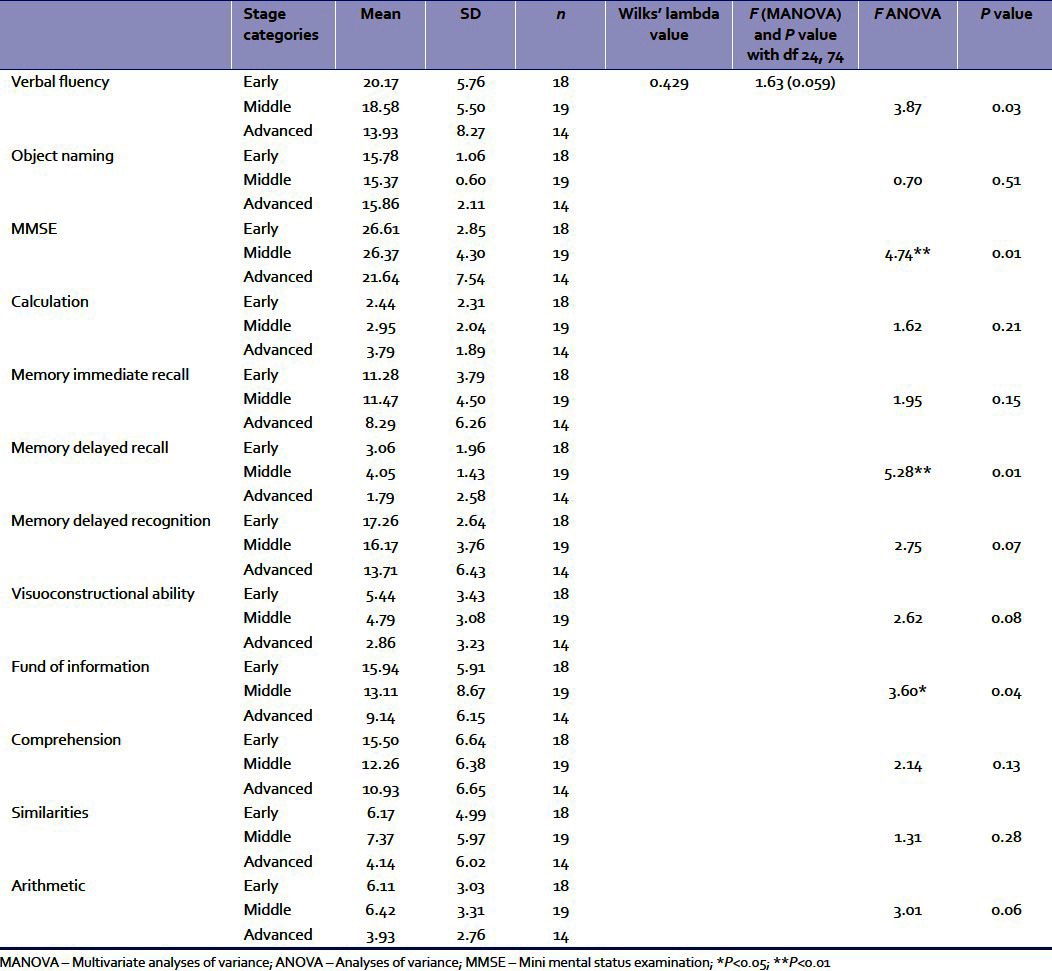

Effects of stage

Effects of stage of disease were subsequently scrutinized. The means and standard deviations of the three groups with differing stages of disease (early, middle, and advanced) are presented in Table 3. Subsequently, MANOVA was conducted with stage of disease as an independent variable and the cognitive functions as dependent variables.

Table 3.

The means and SDs of the three stage groups (early, middle, and advanced) for the cognitive functions and results of MANOVA and ANOVAs

Table 3 indicates that there is no significant effect of stage categories on the dependent variables taken together. Subsequently, univariate ANOVAs were conducted separately for each cognitive variable [Table 3].

Results imply that stage of disease turned out to be a significant variable for verbal fluency, findings from Mini Mental Status Examination (MMSE), delayed recall memory, and fund of information. Subsequently, multiple comparisons between each stage group in terms of the dependent variable were done with Tukey's post hoc tests. The results revealed that for verbal fluency, MMSE, delayed recognition, and fund of information, the mean differences between the early and middle stages or middle and advanced stages were not statistically significant. However, significant differences between early and advanced stages were obtained. For verbal fluency, the difference of 6.24 between the early and advanced stages was significant at 0.025 level. For MMSE, the difference of 4.97 between the early and advanced stages was significant at 0.021 level. For delayed recall, the difference between early and advanced stages of 2.02 was significant at 0.024 level. For fund of information, the difference of 6.80 between the early and advanced stages was significant at 0.027 level.

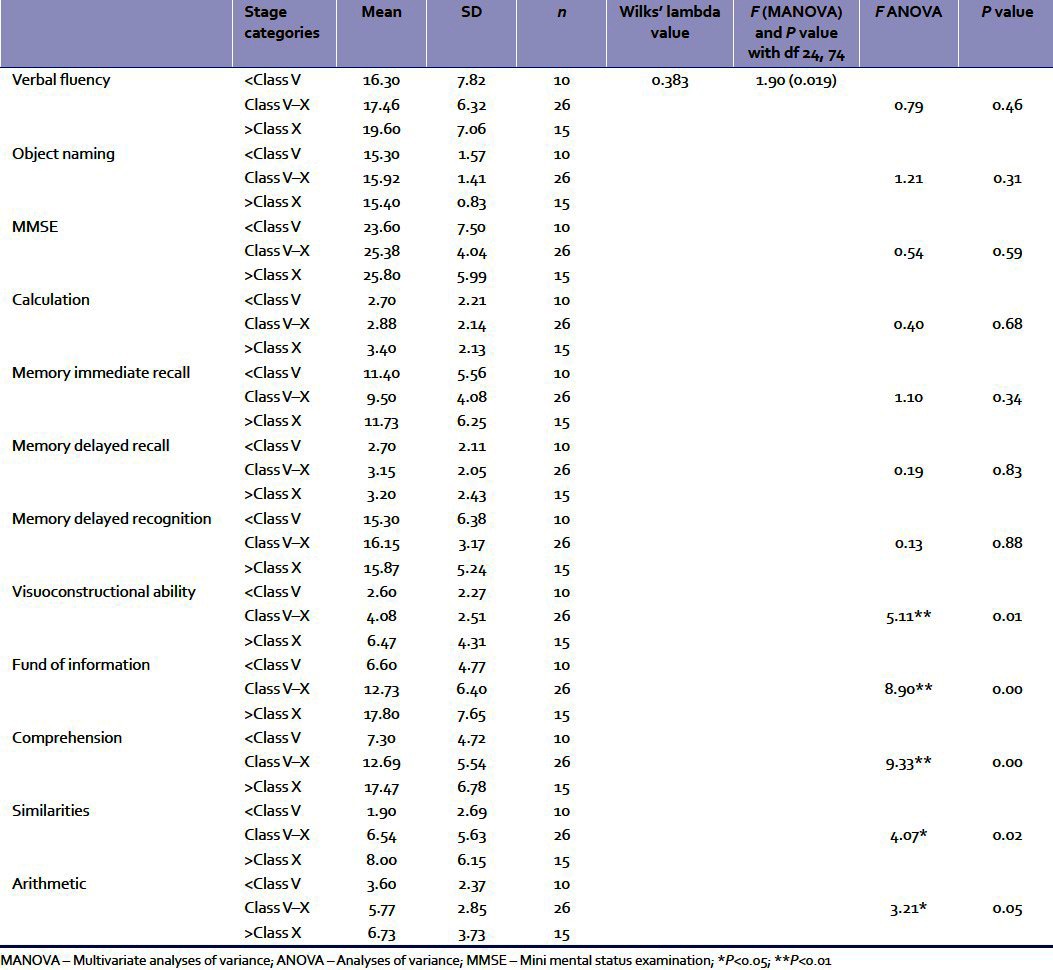

Effects of education

The effects of education were analyzed in the last section. The means and standard deviations of the three groups with differing educational levels (below class V, classes V–X, and above class X) are presented in Table 4. Subsequently, MANOVA was conducted with educational level as an independent variable and the cognitive functions as dependent variables.

Table 4.

The means and SDs of the three educational level groups (<class V, classes V–X, and >class X) for the cognitive functions and results of MANOVA and ANOVAs

Table 4 indicates that there is significant effect of educational levels on the dependent variables taken together. This implies that educational level is a highly significant factor for cognitive decline when all the variables are taken in combination. Subsequently, univariate ANOVAs were conducted separately for each cognitive variable [Table 4]. Results imply that educational level was a significant variable for visuoconstructional ability, fund of information, comprehension, similarities, and arithmetic. Subsequently, multiple comparisons between each educational level group in terms of these dependent variables were done with Tukey's post hoc tests. The results revealed that for visuoconstructional ability, the mean difference of 3.867 between the highest and the lowest educational levels was significant at 0.01 level. The mean difference of 6.13 between the middle and the lowest levels in case of fund of information was significant at 0.039 level. Mean difference of 11.20 between the highest and the lowest levels in case of fund of information was significant at 0.000 level. For comprehension, the mean difference of 5.39 between the middle and the lowest levels was significant at 0.041 level. Mean difference of 10.17 between the highest and the lowest level in case of comprehension was significant at 0.000 level. The mean difference of 4.77 between the highest and middle levels of comprehension was significant at 0.037 level. For similarities, the mean difference of 6.10 between the highest and the lowest educational levels was significant at 0.021 level. For arithmetic, the obtained mean difference of 3.13 between the highest and the lowest educational levels was significant at 0.04 level.

DISCUSSION

The results suggested that most of the functions with the exception of “information” were significantly poorer among the IPD group in comparison to the normative non-demented scores, indicating substantial impairment in cognitive functions in IPD. This finding is corroborated by a number of earlier studies.[1,2]

Table 2 reveals that age came out to be a significant factor only for delayed memory. In the interpretation of age-related changes in this study, it needs to be remembered that the number of subjects was small and majority of the subjects were below 70 years. Also, those with definite signs of dementia and depression had been eliminated. Therefore, age-related decline was limited to specific areas of memory only. Similar findings have been obtained earlier.[5] In a recent study, Kim et al. observed that among IPD patients, age was associated with mild cognitive impairment around the age of 64 years.[22] It is possible that cognitive impairment becomes more pronounced for a higher age group than was taken in this study.

In Table 3, the effects of stage of disease were scrutinized. It was found that stage was significant only between the early and the advanced stages and in case of selected cognitive functions, namely, verbal fluency, MMSE, delayed recall memory, and fund of information. The impairment of various cognitive areas in advanced IPD patients supports the models describing parkinsonism-related changes in dorsolateral prefrontal regions participating in “cognitive” basal ganglia and thalamocortical circuits.[9] Impairment in verbal learning was observed, possibly reflecting deficient use of encoding strategies. Impairment was also more frequent in conditions of delayed recall than in conditions of delayed recognition, where cues guide retrieval.

Results from Table 4 suggest that the level of education was more significant for overall impairment of the cognitive faculties taken together in comparison to age and stage of disease. Lower educational level was associated with greater impairment. Specifically, it affected visuoconstructional ability and the higher cognitive functions. Some earlier studies also offered similar conclusions.[12]

CONCLUSIONS

The present findings reveal that as expected, cognitive functions are impaired in patients with IPD in comparison to normative data. The study also suggests that cognitive functions deteriorate along with increasing age, advanced stage of disease, and educational level. Among these three factors, education appeared to be the most powerful. This has important implication in management, as cognitive practice seems to deter the impairment rate. The non-demented IPD remains a relatively ignored area where management strategies and rehabilitation efforts are concerned. While the present study has significant implications in understanding the nature of cognitive impairment associated with IPD, it is limited by its small sample size and the lack of any internal control group, which would have enhanced its value as evidence. It may be extended along these lines in future research and a charter of cognitive training and practice may be prepared for ready use of the caregiver.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Aarsland D, Zaccai J, Brayne C. A systematic review of prevalence studies of dementia in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2005;20:1255–63. doi: 10.1002/mds.20527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bassett SS. Cognitive Impairment in Parkinson's Disease. Prim psychiatry. 2005;12:50–5. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verbaan D, Marinus J, Visser M, van Rooden SM, Stiggelbout AM, Middelkoop HA, et al. Cognitive impairment in Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:1182–7. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.112367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cronin-Golomb A, Corkin S, Growdon JH. Impaired problem solving task in Parkinson's disease: Impact of a set-shifting deficit. Neuropsychologia. 1994;32:579–93. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(94)90146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zakharov VV, Iakhno NN. Cognitive dysfunction in patients with Parkinson's disease. Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova. 2005;105:13–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Owen AM. Cognitive dysfunction in Parkinson's disease: The role of frontostriatal circuitry. Neuroscientist. 2004;10:525–37. doi: 10.1177/1073858404266776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vingerhoets G, Verleden S, Santens P, Miatton M, De Reuck J. Predictors of cognitive impairment in advanced Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:793–6. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.6.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aarsland D, Larsen JP. Emotional and cognitive disorders in Parkinson's disease. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 1998;118:3959–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green J, McDonald WM, Vitek JL, Evatt M, Freeman A, Haber M, et al. Cognitive impairment in advanced PD without dementia. Neurology. 2002;59:1320–4. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000031426.21683.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ray J, Das SK, Gangopadhya PK, Roy T. Quality of life in Parkinson's disease-Indian scenario. J Assoc Physicians India. 2006;54:17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen OS, Vakil E, Tanne D, Nitsan Z, Schwartz R, Hassin-Baer S. Educational level as a modulator of cognitive performance and neuropsychiatric features in Parkinson's disease. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2007;20:68–72. doi: 10.1097/WNN.0b013e3180335f8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pai MC, Chan SH. Education and cognitive decline in Parkinson's disease: A study of 102 patients. Acta Neurol Scand. 2001;103:243–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parashos SA, Swearingen CJ, Biglan KM, Bodis-Wollner I, Liang GS, Ross GW, et al. Determinants of the timing of symptomatic treatment in early Parkinson disease: The National Institutes of Health Exploratory Trials in Parkinson Disease (NET-PD) Experience. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:1099–1104. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dixit SN, Behari M, Ahuja GK. Effect of selegiline on cognitive functions in Parkinson's disease. J Assoc Physicians India. 1999;47:784–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krishnan S, Mathuranath PS, Sarma S, Kishore A. (Neuropsychological functions in progressive supranuclear palsy, multiple system atrophy and Parkinson's disease. Neurol India. 2006;54:268–72. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.27150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prabhakar S, Syal P, Srivastava T. P300 in newly diagnosed non-dementing Parkinson's disease: Effect of dopaminergic drugs. Neurol India. 2000;48:239–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhatia S, Gupta A. Impairments in activities of daily living in Parkinson's disease: Implications for management. NeuroRehabilitation. 2003;18:209–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sowmini CV, De Vries R. A cross cultural review of the ethical issues in dementia care. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24:329–34. doi: 10.1002/gps.2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Das SK, Banerjee TK, Mukherjee CS, Bose P, Biswas A, Hazra A, et al. An urban community-based study of cognitive function among non-demented elderly population in India. Neurol Asia. 2006;11:37–48. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ganguli M, Ratcliff G, Chandra V, Pandav R, Sharma S, Gilby J, et al. A Hindi version of MMSE: The development of a cognitive screening instrument for a largely illiterate rural elderly population in India. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1995;10:367–77. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoehn MM, Yahr MD. Parkinsonism: Onset, progression and mortality. Neurology. 1967;17:427–42. doi: 10.1212/wnl.17.5.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim JW, Cheon SM, Park MJ, Kim SY, Jo HY. Cognitive Impairment in Parkinson's Disease without Dementia: Subtypes and Influences of Age. J Clin Neurol. 2009;5:133–8. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2009.5.3.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]