Abstract

Objective

Parenting stress in pediatric IBD has been under-examined. Data validating use of The Pediatric Inventory for Parents (PIP), a measure of parenting stress associated with caring for a chronically-ill child, in chronic diseases with intermittent, unpredictable disease courses, such as Inflammatory Bowel Disease, are needed. This study presents validity data in support of the PIP in pediatric IBD and examines relations between parenting stress and important psychosocial and medical outcomes.

Method

Adolescents (N = 130) with IBD and their caregivers across three sites completed measures of parenting stress, family functioning, and emotional/behavioral functioning. Disease severity was also assessed for each participant.

Results

The PIP demonstrates excellent internal consistency. Parenting stress was significantly higher among those with unhealthy general family functioning and those with children with Borderline or Clinically-elevated internalizing symptoms. Caregiving stress was greater among parents of youth with more active Crohn's disease.

Conclusion

Results supported the reliability and validity of the PIP for assessing caregiving stress in pediatric IBD. Routine assessment of parenting stress is recommended, particularly among parents reporting unhealthy family functioning and parents of youth with Borderline or Clinically-elevated internalizing symptoms and more active disease.

Keywords: IBD, parenting stress, adolescent, assessment, internalizing

Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis, collectively known as Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), are chronic conditions characterized by unpredictable periods of disease activity and remission1. Occurring at an incidence of 71 per 100,000 in youth below age 172, individuals with IBD experience a host of unpleasant, and potentially embarrassing, symptoms including diarrhea, abdominal pain, rectal bleeding, poor weight gain, and delayed growth/puberty. Treatment of IBD involves a complex regimen of multiple daily oral medications (e.g., immunomodulators, corticosteroids, vitamins), dietary modifications, and in some cases, surgery3. Approximately 25% of all IBD cases are diagnosed in childhood or adolescence2, a time in which treatment demands and the unpredictable nature of IBD symptoms can have a significant impact on quality of life and overall functioning.

When a child is diagnosed with IBD, the entire family is affected. Incorporating multiple IBD medications, each with a different dosing schedule, into one's daily routine is challenging4. Caregivers must also alter their schedules to accommodate frequent medical appointments and unexpected hospitalizations/surgeries. The unpredictable nature of IBD symptom exacerbations may cause families to live in a constant state of uncertainty; never knowing when symptoms will flare and disrupt family functioning5. Such fluctuating, unpredictable symptoms may cause greater feelings of illness uncertainty, which have been linked to increased stress9. Many caregivers also worry about the impact of IBD on their child's future6, further increasing parenting stress.

Parenting stress in pediatric IBD has not been thoroughly examined. This is primarily due to a lack of measures designed to assess the unique stressors associated with caring for a child with IBD. Generic measures of parenting stress (e.g., Parenting Stress Index7) were designed for caregivers of healthy children and do not assess stressors unique to parenting a child with a chronic illness (e.g., managing medical procedures and appointments, seeing child in pain). The Pediatric Inventory for Parents8, although specifically designed to assess chronic illness-related parenting stress, was created in a pediatric cancer population and later validated in diabetes, two populations whose disease and treatment course significantly differ from IBD. Unlike cancer and diabetes, which have a fairly prescribed and predictable disease and treatment course, pediatric IBD is characterized by a highly unpredictable, waxing and waning disease course. This may lead to a qualitatively different experience for parents of youth with IBD compared to parents of youth with diabetes or cancer. This fundamental difference may significantly impact how each disease (i.e., cancer versus IBD) contributes to parenting stress and one cannot assume that a measure originally created and validated in cancer adequately assesses parenting stress in a considerably different population without examining its psychometric properties.

Although use of the PIP has been reported in sickle cell, bladder exstrophy, and obesity9-11, limited attention has been given to the psychometric properties of this measure in these populations, making the extent to which the PIP is truly capturing parenting stress in these populations unclear. In IBD, the PIP has been used to compare parenting stress levels with other populations12 and has been included as a predictor of quality of life13. To date, no study has examined: 1) the psychometric properties of the PIP in IBD or, 2) presented data on the broader relationship between parenting stress in IBD, child and family psychosocial functioning, and health outcomes. Examining these two areas may lead to improved assessment and understanding of parenting stress in this population. This may ultimately improve our ability to adequately assess parent needs and intervene when needed.

The purpose of this study is two-fold: 1) to examine the psychometric properties of the PIP in a large, multi-site IBD population, and 2) to provide a broader understanding of how parenting stress in IBD relates to child and family psychosocial functioning and medical outcomes. Validation of the PIP in IBD could extend the use of this measure to other illness populations characterized by intermittent, unpredictable disease courses (e.g., arthritis, asthma), thereby broadening the clinical utility of this measure. Examination of relationships between parenting stress and important psychosocial (i.e., child psychopathology, family functioning) and medical (i.e., disease severity) outcomes will improve our understanding of parenting stress in IBD and provide valuable information that may aid in the development of interventions to reduce parenting stress in this population. Higher parenting stress was expected to relate to greater child psychopathology, poorer family functioning, and greater disease severity.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

The current study is part of a larger IRB-approved multisite project examining psychosocial functioning and treatment adherence in adolescents (13 -17 years) with IBD. Participants were recruited at one of three hospital-based pediatric gastroenterology specialty clinics in the Midwest (N = 51), Northeast (N = 42), and Southern (N = 37) United States. Eligibility criteria for the study were: 1) patient age 13-17, 2) diagnosed with IBD (Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis), and 3) accompanied by a parent/legal guardian. Presence of another chronic illness (in patient) or a neurocognitive disorder (e.g., intellectual deficiency or autism) or limited English literacy (in either patient or parent) precluded study participation. In addition, due to higher risk of treatment-associated behavioral and psychiatric symptoms14,15, patients prescribed a corticosteroid at greater than 1 mg/kg/day were excluded.

Eligible patients were recruited in private patient waiting rooms by a member of the research team. Patients and caregivers who expressed interest in the study following a brief introduction were formally consented/assented. Adolescents and caregivers were then given pen-and-paper questionnaires to complete independently. Each dyad was compensated $10 for completion of study questionnaires. In total, 170 eligible dyads were approached for study participation. Of these, 31 declined participation due to lack of time/interest or not feeling well enough to participate. An additional 9 participants were excluded from the database due to incomplete behavioral data. The final sample included 130 adolescents (M = 15.64 years, SD = 1.36) and their caregivers. Participant demographics are summarized in Table 1. There were slightly more males than females in the study and, as similar to other studies in pediatric IBD, the majority of patients were white, non-Hispanic and had Crohn's disease.

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

| N | % or M ± SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Total sample | 130 | |

| Age, years | 15.64 ± 1.36 | |

| Gender, % female | 61 | 46.9 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 106 | 81.5 |

| African American | 9 | 6.9 |

| Hispanic | 4 | 3.1 |

| Other/Unknown | 11 | 8.4 |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Crohn's disease | 100 | 76.9 |

| Ulcerative colitis | 30 | 23.1 |

| Caregiver relationship to adolescent | ||

| Mother | 104 | 80 |

| Father | 16 | 12.3 |

| Other/Unknown | 10 | 7.7 |

| Caregiver marital status | ||

| Married | 104 | 80 |

| Separated/Divorced | 14 | 10.8 |

| Widowed | 2 | 1.5 |

| Single | 1 | 0.8 |

| Not reported/unknown | 9 | 6.9 |

| Annual family income, median | $75,001-100,000 |

Measures

Demographic questionnaire

Caregivers provided sociodemographic information (e.g., family income, child age, race, gender) using a questionnaire created for this study.

Parenting Stress

The Pediatric Inventory for Parents (PIP) assesses parenting stress associated with caring for an individual with a pediatric illness8. This measure contains 42 medically-related situations and thoughts that may contribute to parenting stress (e.g., bringing my child to the clinic or hospital, helping my child with medical procedures, feeling uncertain about the future). For each item, caregivers use a 5-point Likert scale to rate how often an event occurs as well as how difficult/stressful they find this event. Frequency and difficulty scores are individually summed to yield PIP Frequency (PIP-F) and PIP Difficulty (PIP-D) scores (range 42 – 210) with higher scores indicating greater parenting stress. This dual rating approach is guided by a transactional model of stress and coping16, which considers both the occurrence of the event (Frequency) as well as the cognitive appraisal/perception of the event (Difficulty) as contributors to stress. Thus, an event may be stressful because it either occurs frequently, the parent perceives it as difficult, or both. In addition to these global scales, the PIP has four rationally-derived subscales (i.e., communication, emotional functioning, medical care, and role functioning) to help clinicians identify the specific domain(s) in which parents are experiencing stress. The PIP demonstrates excellent internal consistency in pediatric cancer populations (PIP-F = .95, PIP-D = .96; subdomains α ≥ .80) and is significantly associated with parental anxiety (State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, r′s = .60 - .62, p′s < .05) and general measures of parenting stress (Parenting Stress Index r′s = .29 - .38, p′s < .05)8.

Family functioning

The McMaster Family Assessment Device (FAD) is a 60-item parent-completed measure that assesses family functioning across six sub-dimensions as well as the overall functioning of the family (General Functioning Scale)17. On the FAD, caregivers are asked to indicate their family's level of agreement/disagreement on various family behaviors using a 4-point Likert scale (e.g., making decisions is a problem in our family, we confide in each other, we don't get along well together). Positively worded items are reverse scored prior to score summation. Higher scores are suggestive of poorer family functioning. The General Functioning Scale was used in the current study. Internal consistency for the current sample was good (α = .86).

Child psychopathology

Parent and child report of emotional/behavioral functioning was measured using the well-validated Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and Youth Self-Report (YSR), respectively18. The CBCL and YSR each yield age and gender-normed scores across eight subscales and two broad measures of emotional/behavioral functioning: internalizing (e.g., anxiety, depression, somatization) and externalizing (e.g., delinquent behavior, aggression) symptoms. The Internalizing and Externalizing scales were used in the current study. Higher scores indicate greater levels of symptomatology.

Disease severity

Disease severity for Crohn's disease was measured using a short-form version of the Pediatric Crohn's Disease Activity Index (Short PCDAI)19,20 The Short PCDAI is a 6-item validated measure of disease severity that overcomes the barriers to implementing the full PCDAI in clinical practice (e.g., calculating height velocity, obtaining laboratory data, conducting a perirectal exam)21. The Short PCDAI is strongly correlated with the PCDAI (r = .66) and discriminates well between different levels of disease severity. Items on the Short PCDAI include patient 1-week recall of symptoms (i.e., abdominal pain, general functioning/well-being, stools per day) as well as data collected via physician-conducted physical examination (e.g., weight change, abdominal tenderness, extra-intestinal manifestations). Scores range from 0 to 90, with higher scores indicating more severe disease. Disease severity for patients with ulcerative colitis was measured using the 8-item Lichtiger Colitis Activity Index (LCAI)22. The LCAI measures disease activity at the time of the clinic visit across 8 symptoms: daily stool frequency, nocturnal diarrhea, blood in stool, fecal incontinence, abdominal pain/cramping, general well-being, abdominal tenderness, and need for anti-diarrheal medication. For each item, providers use a Likert scale to rate the patient's level of severity (for continuous items; e.g., number of stools per day) or the presence/absence of a symptom (e.g., nocturnal diarrhea). Scores for each item are then summed (range: 0-21) to provide an overall estimate of disease severity. Higher scores suggest worse disease, with an LCAI score of ≤2 indicating quiescent disease, 3-9 suggesting response to therapy, and a score of 10 or above suggesting active disease/no response to treatment23.

Data Analysis

All data analyses were conducted using SPSS 18.0 (Chicago, IL). Descriptive statistics were run to ensure data were normally distributed prior to data analyses. Cronbach's alphas were calculated to examine internal consistency for the PIP Difficulty and PIP Frequency scales and their corresponding subscales. Interscale correlations were examined using Pearson product-moment correlations. Correlations were conducted to characterize the relationships between parenting stress and important psychosocial (i.e., family functioning, child psychopathology, family functioning) and medical (i.e., disease severity) outcomes. For those measures which have clinical cut-off scores (i.e., CBCL, FAD), parenting stress levels were examined by clinical category using either a t-test or an analysis of variance. Finally, an exploratory analysis was conducted to further examine the relationship between parenting stress and child disease severity in a large subset of the population, those with Crohn's disease.

Results

Internal Consistency of the PIP

Internal consistency was calculated for the PIP Frequency (PIP-F) and PIP Difficulty (PIP-D) scores as well as the four PIP subscales (see Table 2). Internal consistencies for the two overall scales was high (both α′s = .96). Cronbach's alphas for the four subscales ranged from .77 to .93, indicating acceptable-to-excellent internal consistency.

Table 2. Means and internal consistency scores of the Pediatric Inventory for Parents (PIP).

| PIP Frequency | PIP Difficulty | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| Scale | (M ± SD) | α | (M ± SD) | α |

| Communication | 18.62 ± 6.10 | .83 | 14.89 ± 5.44 | .80 |

| Emotional functioning | 34.06 ± 12.11 | .92 | 35.11 ± 13.56 | .93 |

| Medical Care | 17.09 ± 7.18 | .85 | 13.26 ± 5.54 | .82 |

| Role functioning | 18.15 ± 6.23 | .78 | 17.34 ± 6.02 | .77 |

| Total | 87.92 ± 28.84 | .96 | 80.60 ± 27.71 | .96 |

Interscale Correlations

PIP Frequency and PIP Difficulty scores were highly correlated (r = .85, p <.001). As shown in Table 3, correlations between subscales were moderate-to-strong in the Difficulty domain (r′s = .68 - .82, p′s <.001) and the Frequency domain (r′s = .68 - .84, p′s <.001).

Table 3. Interscale correlations of Pediatric Inventory for Parents (PIP).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PIP Total Difficulty | - | |||||||||

| 2. PIP Total Frequency | .85 | - | ||||||||

| 3. Communication (D) | .90 | .77 | - | |||||||

| 4. Medical care (D) | .88 | .72 | .82 | - | ||||||

| 5. Emotional distress (D) | .95 | .79 | .78 | .76 | - | |||||

| 6. Role function (D) | .84 | .77 | .73 | .68 | .71 | - | ||||

| 7. Communication (F) | .78 | .93 | .80 | .67 | .70 | .69 | - | |||

| 8. Medical care (F) | .70 | .88 | .63 | .69 | .62 | .60 | .82 | - | ||

| 9. Emotional distress (F) | .86 | .95 | .75 | .68 | .87 | .69 | .84 | .75 | - | |

| 10. Role function (F) | .70 | .86 | .63 | .53 | .59 | .83 | .75 | .68 | .76 | - |

Note: D = Difficulty domain; F = Frequency domain; all correlations significant at the p <.001 level

Relationship Between Parenting Stress and Family Functioning

Families reporting poorer general family functioning also reported experiencing more frequent (PIP Frequency r = .30, p <.01) and more difficult (PIP Difficulty r = .31, p <.01) medically-related stressful situations and thoughts. To further understand this relationship, participants were divided into normal or clinically-elevated groups based on published norms24. Those whose General Functioning subscale score was equal to or above the mean reported for clinically-referred samples were labeled “clinically-elevated” while those whose scores fell below this cut point were labeled “normal.” Mean parenting stress levels were then compared between groups to determine if parenting stress differed from those families reporting healthy general family functioning from those reporting less healthy functioning. Compared to those reporting healthy family functioning, families with clinically-elevated general family functioning scores reported significantly more stress due to more frequent (PIP Frequency; 111.78 vs. 85.73; t(117) = −2.67, p <.001) and more difficult (PIP Difficulty; 108.11 vs. 78.19; t(117) = −3.22, p<.001) medically-related situations and thoughts.

Relationship Between Parenting Stress and Child Psychopathology

Parent report

More frequent and more difficult stressful situations were associated with greater parent report of internalizing symptoms (r = .58, p <. 001) and externalizing symptoms (r = .38, p <. 001). An analysis of variance test was used to investigate whether parenting stress differed by clinical markers of child psychopathology. Participants were divided into normal, borderline, and clinically-elevated categories according to well-established CBCL cut-offs18. For internalizing symptoms, parenting stress related to the frequency of medical events (PIP Frequency) differed significantly by group, F(2, 118) = 15.61, p <.001 (Table 4). A similar relationship was found for difficult stressful situations (PIP Difficulty), F(2, 118) = 25.34, p < .001. For both domains, Bonferroni post-hoc analyses revealed that parenting stress was significantly greater among those in the Borderline and Clinically-elevated groups than among those in the Normal range of internalizing symptoms. There was no significant difference in parenting stress between Borderline and Clinically-elevated internalizing groups. There were no significant differences in parenting stress among externalizing groups.

Table 4. Parenting stress by clinical categories.

| N | PIP Difficulty Mean (SD) | PIP Frequency Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family Functioning | |||

| Healthy | 111 | 78.19 (26.48) | 85.73 (27.78) |

| Unhealthy | 9 | 108.11 (29.95)A | 111.78 (233.62)A |

| CBCL Internalizing | |||

| Normal | 89 | 71.35 (22.51)B,C | 79.73 (25.93)B,C |

| Borderline | 19 | 108.11 (27.86)A | 111.00 (25.17)A |

| Clinically-elevated | 12 | 102.21 (20.82)A | 107.04 (23.07)A |

| YSR Internalizing | |||

| Normal | 84 | 74.99 (26.14)C | 82.06 (27.51)B |

| Borderline | 11 | 93.45 (29.96) | 106.45 (27.29)A |

| Clinically-elevated | 21 | 92.93 (29.19)A | 95.98 (29.16) |

| CBCL Externalizing | |||

| Normal | 116 | 79.75 (27.85) | 86.67 (28.44) |

| Borderline | 3 | 97.00 (19.08) | 114.00 (27.87) |

| Clinically-elevated | 1 | 97.00* | 101.00* |

| YSR Externalizing | |||

| Normal | 100 | 81.01 (28.20) | 87.73 (28.74) |

| Borderline | 11 | 80.18 (27.58) | 87.82 (30.88) |

| Clinically-elevated | 5 | 60.40 (22.94) | 69.20 (23.91) |

Note: CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist; YSR = Youth Self-report;

Significantly differs from Normal/Healthy;

Significantly differs from Borderline,

Significantly differs from Clinically-elevated;

Cell size too small to calculate standard deviation

Adolescent report

The Youth Self-report was used to replicate the relationships found between parenting stress and parent-reported child psychopathology. Adolescent report of internalizing, but not externalizing, symptoms was associated with parenting stress due to more difficulty (PIP Difficulty r = .35, p <.001) and more frequent (PIPFrequency r = .26, p <.01) medical situations and thoughts. Significant group differences also emerged when participants were grouped into normal, borderline, and clinically-elevated categories for both PIP Difficulty, F(2, 114) = 5.18, p <.01, and PIP Frequency, F(2, 114) = 5.10, p < .01, parenting stress. However, the pattern of significance differed slightly. Parenting stress due to more frequent medical events and situations differed significantly between Normal and Borderline groups (p < .05) but there were no differences with those who were Clinically-elevated. Parenting stress due to more difficult medical events and situations differed between Normal and Clinical groups (p < .05). Although mean score differences were greatest between Normal (M = 74.99) and Borderline (M = 93.45) groups, this did not reach significance; possibly due to smaller sample size within the Borderline group. Groups differences in parenting stress by externalizing group were not explored due to a non-significant correlation between these variables as well as small sample sizes within Borderline (N = 3) and Clinically-elevated (N = 1) groups.

Relationship Between Parenting Stress and Child Disease Severity

Of particular interest was the relationship between parenting stress and IBD disease severity. Parenting stress was expected to be positively associated with disease severity. As the disease severity measures for the PCDAI and LCAI have a different range of possible scores, the relationship between parenting stress and patient disease severity was examined separately for patients with Crohn's disease and those with ulcerative colitis. Among patients with Crohn's disease, disease severity was significantly associated with more frequent (PIP Frequency r = .30, p< .01) and more difficult (PIP Difficulty r = .32, p <.01) medically-related stressful situations. However, there was no significant relationship between disease severity and parenting stress among patients with ulcerative colitis. Given this, only those with Crohn's disease were included in subsequent exploratory analyses.

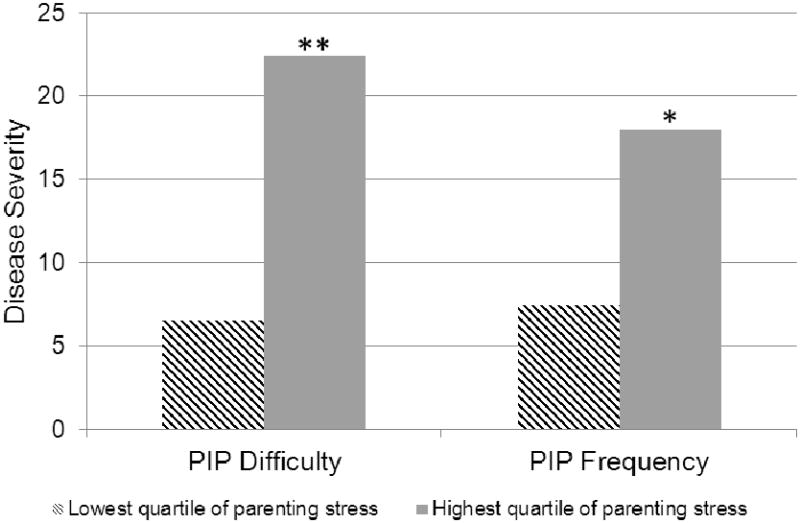

We compared levels of disease severity among those caregivers reporting PIP Difficulty and PIP Frequency scores in the highest quartile to those caregivers with scores in the lowest quartile. Child disease severity scores were significantly greater among those caregivers reporting the highest level of stress due to more difficult and more frequent medical events compared to caregivers reporting stress at or below the 25th percentile, t(40) = −4.83, p <.001; t(41) = −2.92, p <.01 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Crohn's disease severity by lowest and highest PIP quartile; * p <.01, ** p <.001.

Discussion

Caring for a child with a chronic illness can place significant strain on parents. The creation of the Pediatric Inventory for Parents was an important step toward improving our understanding of the unique stressors associated with caring for a child with a chronic illness. However, as the PIP was developed and validated in a population with a dramatically different disease and treatment course, determining whether the PIP was psychometrically sound in a condition with an intermittent, waxing and waning, unpredictable course was clinically important. Our findings support use of the Pediatric Inventory for Parents as measure of parenting stress in the pediatric IBD population and suggests that this measure may be useful for other conditions with similarly unpredictable disease and treatment courses.

An addition to the literature was the broader examination of parenting stress as it relates to important psychosocial and medical outcomes. In addition to examining overall associations, we also used empirically-derived cut-points to determine how parenting stress relates to clinically-relevant classifications. Our findings show that parenting stress is highest among those with unhealthy levels of family functioning, thereby identifying a population at greater risk for chronic illness-related parenting stress. In the broader pediatric IBD literature, poor family functioning is linked with poorer child health-related quality of life25, child behavior problems26, increased disease severity27, and more pain/fatigue28. These significant associations, combined with our findings, speak to the importance of identifying and addressing poor family functioning in IBD.

Relationships between parenting stress and child psychopathology, particularly internalizing symptoms, were also of interest. Our findings extend those of Herzer and colleagues13, which linked parenting stress with adolescent depressive symptoms in a smaller pediatric IBD sample. We used a well-validated measure to examine anxiety and depression more broadly and included both parent and youth-report to minimize shared method bias. Furthermore, by breaking down our population into empirically-derived categories (i.e., normal, borderline, clinically-elevated), we translated the parenting stress-child internalizing symptoms relationship into clinically-meaningful information to guide early identification and intervention.

Our finding that parenting stress is elevated and does not differ between Borderline and Clinically-elevated populations suggests that even emerging problems (i.e., those that are not yet at clinically-elevated levels) are in need of intervention. Although Clinically-elevated individuals may be more likely to be identified and receive treatment, our findings show that parents with youth in the Borderline range have similarly elevated, if not higher levels of parenting stress, and would also benefit from early identification and treatment. In our sample, 27.6% of adolescents fell into the Borderline or Clinically-elevated range as indicated by youth self-report. This represents a significant portion of the population that may be in need of intervention.

Caring for a child with a co-morbid emotional problem may have an additive impact on parenting stress. Caregivers must manage adolescent emotional symptoms in the context of an already demanding, stress-producing, medical condition. Emotional symptoms may also affect parenting stress indirectly by interfering with a caregiver's ability to ensure the child remains adherent to the IBD regimen29. This may lead to increased disease activity29-31 and need for more intensive treatment, ultimately contributing to additional parenting stress.

In addition to examining the link between parenting stress and psychosocial outcomes, this study examined the link between parenting stress and health. It was expected that parents of children with more severe disease would experience greater burden and would report greater stress. This hypothesis was partially supported. PIP scores were associated with disease severity for patients with Crohn's disease but not ulcerative colitis. This may have been due to the small number of patients with ulcerative colitis, resulting in underpowered analysis, or limitations of our measurement approach. Data collection for this study began prior to the publication of the Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis Index32, resulting in our inclusion of a commonly used yet less methodologically rigorous measure. Medical differences between Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis may also play a role. Although both disorders involve inflammation in the digestive tract, the location of this inflammation and chronicity of symptoms varies by condition. Crohn's disease has a more systemic impact on the body and inflammation can occur anywhere along the digestive tract. For ulcerative colitis, inflammation is generally limited to the large intestine and the chronicity of the disorder is less severe. As a result of these differences, patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis have different treatment options and may experience slightly different symptoms. Most research studies group patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis into one sample. Our findings suggest that there are subtle differences between these subgroups and separate examination of patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis is warranted.

Study findings must be viewed in light of study strengths and limitations. The multi-site nature of our study enabled us to recruit a large sample of participants. This is a significant strength as most psychosocial pediatric IBD studies are single-site and have small samples. The use of well-validated measures, empirically-derived cut points to translate data into clinically-meaningful recommendations, and a multi-informant approach are also strengths. With regard to limitations, patient, caregiver, and family characteristics were relatively homogeneous. Although our study participants were similar to samples previously reported in pediatric IBD research33, the homogeneity of our sample limits our ability to extend our findings to ethnic minorities, father caregivers, or those of lower socioeconomic status. These populations remain underrepresented in IBD research and should be a focus in future research. Additionally, although our multi-informant approach minimizes shared-method variance, it does not eliminate this possibility. Finally, due to the cross-sectional nature of our study, temporal relationships between parenting stress and child/family functioning were not explored. Prospective examination of these relationships is needed.

Given the negative impact of parenting stress and the greater risk for caregivers of youth with IBD to experience stress, it is important that providers assess for parent stress on a regular basis. The brief nature of the PIP makes it ideal for administration during the child's medical appointment. (Note: Individuals interested in using the PIP in clinical practice or research are encouraged to refer to the original PIP publication8 and contact the PIP's creator, Dr. Randi Streisand, at rstreis@childrensnational.org for additional information.) While other measures included in this study may not be feasible for use in routine practice due to length, brief measures of child emotional and behavioral functioning (e.g., Child Depression Inventory Short Form34, Pediatric Symptom Checklist35-37, Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory38,39) should be considered. Visual scan of these measures can provide a quick overview of the patient's/parent's functioning and can help initiate conversations with the family about their struggles. Furthermore, acknowledging that it is common for caregivers of youth with IBD to experience stress and reviewing PIP results in session may improve communication with caregivers who would otherwise be reluctant to initiate such conversations on their own. When warranted, providers may consider referring parents to a local support group or mental health specialist.

Although establishing the validity of the PIP in pediatric IBD is an important first step in improving our understanding of parenting stress in the IBD population, additional work in this area is need. Future research should examine the role of parent psychopathology and parenting stress as some research suggests parents of youth with IBD may be at greater risk for depression40,41. Parent psychopathology may impact parents' perception of parenting stress as well as their ability to manage IBD treatment. Research should also examine the relationship between parenting stress and clinically salient outcomes (e.g., treatment adherence) as well as work toward identifying those factors which increase or decrease parenting stress. Improved understanding of these factors may aid in the development of effective interventions that will ultimately improve parent functioning and child health outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded a grant from the University of Florida Center for Pediatric Psychology and Family Studies (awarded to the first author) and a career development award (K23 DK079037) and grants from the National Center for Research Resources (UL1 RR026314) and Procter & Gamble Pharmaceuticals and Prometheus Laboratories (awarded to the fifth author).

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dubinsky M. Special issues in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2008 Jan 21;14(3):413–420. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auvin S, Molinie F, Gower-Rousseau C, et al. Incidence, clinical presentation and location at diagnosis of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective population-based study in northern France (1988-1999) J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005 Jul;41(1):49–55. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000162479.74277.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman K, et al. The prevalence and geographic distribution of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;5(12):1424–1429. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hommel KA, Odell S, Sander E, Baldassano RN, Barg FK. Treatment adherence in paediatric inflammatory bowel disease: Perceptions from adolescent patients and their families. Health Soc Care Community. 2011 Jan;19(1):80–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2010.00951.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicholas D, Otley A, Smith C, Avolio J, Munk M, Griffiths A. Challenges and strategies of children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: a qualitative examination. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5(1):28. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akobeng A, Miller V, Firth D, Suresh-Babu MV, Mir P, Thomas AG. Quality of life of parents and siblings of children with inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of Pediatric Gastroeneterology and Nutrition. 1999;28(4):S40–42. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199904001-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abidin RR. Parenting Stress Index: Professional Manual. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Streisand R, Braniecki S, Tercyak KP, Kazak AE. Childhood illness-related parenting stress: the pediatric inventory for parents. J Pediatr Psychol. 2001 Apr-May;26(3):155–162. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/26.3.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Logan DE, Radcliffe J, Smith-Whitley K. Parent factors and adolescent sickle cell disease: Associations with patterns of health service use. J Pediatr Psychol. 2002 Jul-Aug;27(5):475–484. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.5.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohleyer V, Freddo M, Bagner DM, et al. Disease-related stress in parents of children who are overweight: Relations with parental anxiety and childhood psychosocial functioning. J Child Health Care. 2007 Jun;11(2):132–142. doi: 10.1177/1367493507076065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mednick L, Gargollo P, Oliva M, Grant R, Borer J. Stress and coping of parents of young children diagnosed with bladder exstrophy. J Urol. 2009 Mar;181(3):1312–1317. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guilfoyle SM, Denson LA, Baldassano RN, Hommel KA. Paediatric parenting stress in inflammatory bowel disease: Application of the Pediatric Inventory for Parents. Child Care Health Dev. 2012 Feb 7;38(2):273–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01200.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herzer M, Denson LA, Baldassano RN, Hommel KA. Patient and parent psychosocial factors associated with health-related quality of life in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011 Mar;52(3):295–299. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181f5714e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kayani S, Shannon DC. Adverse behavioral effects of treatment for acute exacerbation of asthma in children: A comparison of two doses of oral steroids. Chest. 2002 Aug;122(2):624–628. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.2.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soliday E, Grey S, Lande MB. Behavioral effects of corticosteroids in steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome. Pediatrics. 1999;104(4):e51. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.4.e51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller IW, Epstein NB, Bishop DS, Keitner GI. The McMaster Family Assessment Device: Reliability and validity. J Marital Fam Ther. 1985;11(4):345–356. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist. Burlington, VT: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hyams JS, Ferry GD, Mandel FS, et al. Development and validation of a pediatric Crohn's Disease Activity Index. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1991;12(4):439–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hyams JS, Markowitz J, Otley A, et al. Evaluation of the Pediatric Crohn Disease Activity Index: A prospective multicenter experience. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;41(4):416–421. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000183350.46795.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kappelman MD, Crandall WV, Colletti RB, et al. Short Pediatric Crohn's Disease Activity Index for quality improvement and observational research. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;17(1):112–117. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lichtiger S, Present DH, Kornbluth A, et al. Cyclosporine in severe ulcerative colitis refractory to steroid therapy. N Engl J Med. 1994 Jun 30;330(26):1841–1845. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406303302601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fanjiang G, Russell GH, Katz AJ. Short- and long-term response to and weaning from Infliximab therapy in pediatric ulcerative colitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44(3):312–317. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31802e98d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Epstein NB, Baldwin LM, Bishop DS. The McMaster Family Assessment Device. J Marital Fam Ther. 1983;9(2):171–180. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herzer M, Denson LA, Baldassano RN, Hommel KA. Family functioning and health-related quality of life in adolescents with pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011 Jan;23(1):95–100. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283417abb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'dell S, Sander E, Denson LA, Baldassano RN, Hommel KA. The contributions of child behavioral functioning and parent distress to family functioning in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2011 Mar;18(1):39–45. doi: 10.1007/s10880-011-9228-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wood B, Watkins JB, Boyle JT, Nogueria J, Zimand E, Carroll L. The “psychosomatic family” model: An empirical and theoretical analysis. Fam Process. 1989;28(4):399–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1989.00399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tojek TM, Lumley MA, Corlis M, Ondersma S, Tolia V. Maternal correlates of health status in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52(3):173–179. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00291-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gray WN, Denson LA, Baldassano RN, Hommel KA. Treatment adherence in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: The collective impact of barriers to adherence and anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Pediatric Pscyhology. 2012;37(3):282–291. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsr092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reed-Knight B, Lewis JD, Blount RL. Association of disease, adolescent, and family factors with medication adherence in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;36(3):308–317. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greenley RN, Kunz JH, Biank V, et al. Identifying youth nonadherence in clinical settings: Data-based recommendations for children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2011 doi: 10.1002/ibd.21859. n/a-n/a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turner D, Otley AR, Mack D, et al. Development, validation, and evaluation of a pediatric ulcerative colitis activity index: a prospective multicenter study. Gastroenterology. 2007 Aug;133(2):423–432. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mackner LM, Crandall WV. Psychological factors affecting pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2007;19(5):548–552. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3282ef4426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kovacs M. Children's Depression Inventory. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jellinek MS, Murphy J, Little M, Pagano ME, Comer DM, Kelleher KJ. Use of the pediatric symptom checklist to screen for psychosocial problems in pediatric primary care: A national feasibility study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(3):254–260. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.3.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Little M, Murphy JM, Jellinek MS, Bishop SJ, et al. Screening 4- and 5-year-old children for psychosocial dysfunction: A preliminary study with the Pediatric Symptom Checklist. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1994;15(3):191–197. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jellinek MS, Murphy JM, Burns BJ. Brief psychosocial screening in outpatient pediatric practice. J Pediatr. 1986;109(2):371–378. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(86)80408-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Seid M, Skarr D. The PedsQL 4.0 as a pediatric population health measure: Feasibility, reliability, and validity. Ambul Pediatr. 2003 Nov-Dec;3(6):329–341. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2003)003<0329:tpaapp>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Varni JW, Seid M, Kurtin PS. PedsQL 4.0: Reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory version 4.0 generic core scales in healthy and patient populations. Med Care. 2001 Aug;39(8):800–812. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200108000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burke P, Kocoshis S, Neigut D, Sauer J, Chandra R, Orenstein D. Maternal psychiatric disorders in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease and cystic fibrosis. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 1994;25(1):45–52. doi: 10.1007/BF02251099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Szajnberg N, Krall V, Davis P, Treem J, Hyams J. Psychopathology and relationship measures in children with inflammatory bowel disease and their parents. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 1993;23(3):215–232. doi: 10.1007/BF00707151. 1993/03/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]