Abstract

We describe the framework of a data-fuelled, interdisciplinary team-led learning system. The idea is to build models using patients from one’s own institution whose features are similar to an index patient as regards an outcome of interest, in order to predict the utility of diagnostic tests and interventions, as well as inform prognosis. The Laboratory of Computational Physiology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology developed and maintains MIMIC-II, a public deidentified high- resolution database of patients admitted to Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. It hosts of teams of clinicians (nurses, doctors, pharmacists) and scientists (database engineers, modelers, epidemiologists) who translate the day-to-day questions during rounds that have no clear answers in the current medical literature into study designs, perform the modeling and the analysis and publish their findings. The studies fall into the following broad categories: identification and interrogation of practice variation, predictive modeling of clinical outcomes within patient subsets and comparative effectiveness research on diagnostic tests and therapeutic interventions. Clinical databases such as MIMIC-II, where recorded health care transactions - clinical decisions linked with patient outcomes - are constantly uploaded, become the centerpiece of a learning system.

Keywords: Collective experience, Intensive care, Electronic medical database, Clinical decision support

I. INTRODUCTION

Clinical databases provide a unique opportunity to evaluate practice variation and the impact of diagnostic and treatment decisions on patient outcomes. When used for research purposes, they have potential advantages compared to randomized clinical trials, including lower marginal costs, readily-accessible large and diverse patient study populations, and shorter study execution time periods. Critically ill patients are an ideal population for clinical database investigations because the clinical value of many treatments and interventions they receive is uncertain, and high-quality data supporting or discouraging specific practices is relatively sparse.

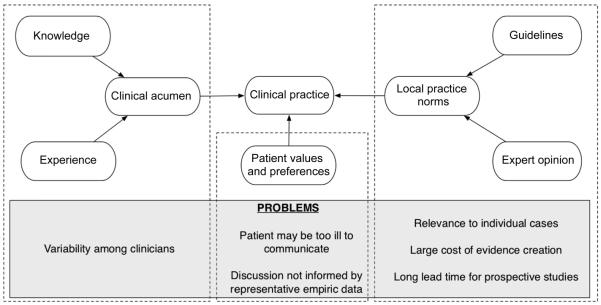

In practice, each clinician initiates a particular diagnostic test or treatment, informed by their training and experience, and local practice norms (see Fig. 1). In a sense each intervention is an “experiment”.

Fig. 1.

Clinical decision-making and its current problems.

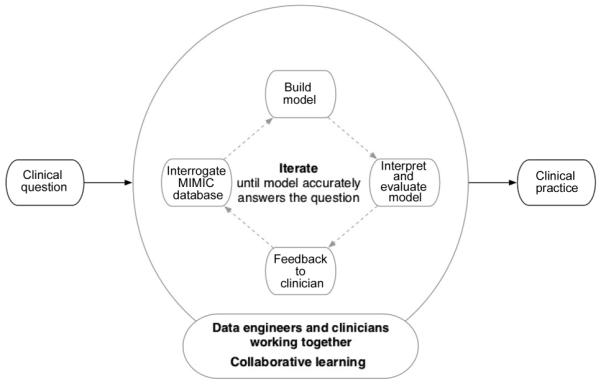

In light of the uncertainty regarding the clinical value of treatments and interventions in the intensive care unit, and the implications that this evidence gap has on clinical outcomes, we have developed a collaborative approach (see Fig. 2) to data-fuelled practice using a high-resolution intensive care unit (ICU) database called MIMIC-II [1]. With support from the National Institutes of Health (NIBIB grant 2R01-001659), the Laboratory of Computational Physiology (LCP) at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) developed and maintains MIMIC-II, a public de-identified database of ~40,000 ICU admissions (version 2.6) to Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC). Our approach hinges on the creation of a learning system that enables the aggregation and analysis of the wealth of individual treatment experiments undertaken by clinicians in the ICU, thereby facilitating data-driven practice rather than one that is driven predominantly by individual clinician preference and the existing ICU culture. The laboratory hosts teams of clinicians (nurses, doctors, pharmacists) and scientists (database engineers, modelers, epidemiologists) who translate day-to-day questions typically asked during medical rounds that often have no clear answers in the current medical literature into study designs and then perform the modeling and the analysis and publish their findings. The studies fall into the following broad categories: identification and interrogation of practice variation, predictive modeling of clinical outcomes within patient subsets and comparative effectiveness research on diagnostic tests and therapeutic interventions. The vision is a data-fuelled, inter-disciplinary team-led learning system that aggregates and analyses day-to-day experimentations as captured in clinical databases, where new knowledge is constantly extracted and propagated for quality improvement, and where practice is driven by outcomes, and less so by individual clinician knowledge base and experience and the local medical culture.

Fig. 2.

Collective experience: a data-fuelled, inter-disciplinary team-led learning system.

II. METHODS

A. Data Collection

The ICU data in MIMIC-II were collected at BIDMC in Boston, MA, USA during the period from 2001 to 2008. Adult data were acquired from four ICUs at BIDMC: medical (MICU), surgical (SICU), coronary care unit (CCU), and cardiac surgery recovery unit (CSRU). MIMIC-II also contains data from the neonatal ICU (NICU) of BIDMC, but this paper focuses only on the adult data, which make up the majority of MIMIC-II. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of BIDMC and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Two types of data were obtained: clinical data and physiological waveforms. The clinical data were acquired from the CareVue Clinical Information System (models M2331A and M1215A; Philips Healthcare, Andover, MA) and the hospital’s electronic archives. The data included patient demographics, nursing notes, discharge summaries, continuous intravenous drip medications, laboratory test results, nurse-verified hourly vital signs, etc. Table 1 describes different clinical data types in MIMIC-II by giving examples of each type. The physiological waveforms were collected from bedside monitors (Component Monitoring System Intellivue MP-70; Philips Healthcare) and included high-resolution (125 Hz) waveforms (e.g., electrocardiograms), derived time series such as heart rate, blood pressures, and oxygen saturation (either once-perminute or once-per-second), and monitor-generated alarms. Fig. 3 shows an example of high-resolution waveforms.

Table 1.

Clinical data types in MIMIC-II

| Clinical data type | Examples |

|---|---|

| Demographics | Age, gender, date of death (date-shifted, in-hospital or after discharge), ethnicity, religion |

| Hospital admission | Admission and discharge dates (date-shifted), room tracking, code status, ICD-9 codes, DRG |

| Intervention | Ventilator settings, IV medications, provider order entry data, CPT codes |

| Laboratory tests | Blood chemistries, hematology, urinalysis, microbiologies |

| Fluid balance | Solutions, blood transfusion, urine output, estimated blood loss |

| Free-text | Reports of imaging studies (no actual images) and 12-lead ECGs, nursing notes, hospital discharge summaries |

| Severity scores | SAPS I, SOFA, elixhauser comorbidities |

ICD-9: International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision, DRG: Diagnosis Related Group, IV: intravenous, ECGs: electrocardiograms, CPT: Current Procedural Terminology, SAPS: Simplified Acute Physiology Score, SOFA: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Fig. 3.

An example of high-resolution waveforms. RESP: respiration, PLETH: plethysmogram, ABP: arterial blood pressure, ECG: electrocardiogram.

B. Database Organization

After data collection, the clinical data were processed and imported into a relational database that can be queried using Structured Query Language [2]. Although some of the clinical data are in standardized formats (e.g., International Classification of Diseases, Diagnosis Related Group, Current Procedural Terminology, etc.), the clinical database does not follow a standardized structure since such a standard did not exist, to the best of our knowledge, at the time of MIMIC-II creation. The database was organized according to individual patients at the highest level. A given patient might have had multiple hospital admissions and each hospital admission in turn could have included multiple ICU stays; within the same hospital admission, ICU stays separated by a gap greater than 24 hours were counted separately. Unique subject, hospital admission, and ICU stay IDs were linked to one another to indicate relationships among patients, hospital admissions, and ICU stays.

The physiological waveforms were converted from the proprietary Philips format to an open source format (WFDB) [3] (one of the widely used physiological waveform formats) to be stored separately from the clinical data. Because the clinical and physiological data originated from different sources, they had to be matched to each other by confirming a common patient source [4]. Although unique identifiers such as medical record number and patient name were utilized for this matching task, a significant portion of the physiological waveforms lacked such an identifier, resulting in limited matching success. Moreover, waveform data collection spanned a shorter period of time than clinical data collection due to technical issues, and waveform data were not collected in the first place for many ICU stays.

C. Deidentification

In order to comply with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, MIMIC-II was deidentified by removing protected health information (PHI). Also, the entire time course of each patient (all hospital admissions and ICU stays) was time-shifted to a hypothetical period in the future. This deidentification was a straight-forward task for structured data fields but was a challenging task for free-text data such as nursing notes and discharge summaries. Thus, an automated deidentification algorithm was developed and was shown to perform better than human clinicians in detecting PHI in free-text documents. For more details about this open-source algorithm, please see [5, 6].

D. Public Access

In order to gain free access to MIMIC-II, any interested researcher simply needs to complete a data use agreement and human subjects training. The actual access occurs over the Internet. The clinical data can be accessed either by downloading a flat-file text version or via a live connection through password-protected web service. The physiological waveforms are best accessed using the WFDB software package. For detailed information regarding obtaining access to MIMIC-II, please see the MIMIC-II website: http://physionet.org/mimic2.

E. Using MIMIC-II in Clinical Practice

A program between the engineers at LCP and clinicians at BIDMC was launched in September 2010 to facilitate the use of MIMIC-II in day-to-day clinical practice. The scientists join the clinicians on rounds to gain a better understanding of clinical medicine and help identify information gaps that may be addressed by data modeling using MIMIC-II. A question that arises during rounds such as “What is the effect of being on a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (anti-depressant) has on clinical outcomes of a patient who has sepsis?” triggers an iterative process participated in by both clinicians and engineers that leads to the study design, the outcomes of interest, a list of candidate predictors, eventual data modeling and analysis to answer the question.

III. RESULTS

Table 2 tabulates adult patient statistics in MIMIC-II, stratified with respect to the four critical care units. In total, 26,870 adult hospital admissions and 31,782 adult ICU stays were included in MIMIC-II. MICU patients formed the largest proportion among the 4 care units, while CCU patients made up the smallest cohort. Only 15.7% of all ICU stays were successfully matched with waveforms. In terms of neonates, 7,547 hospital admissions and 8,087 NICU stays were added to MIMIC-II.

Table 2.

Adult patient statistics in MIMIC-II (version 2.6), stratified with respect to the critical care unit

| MICU | SICU | CSRU | CCU | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital admissions a) | 10,313 (38.4) | 6,925 (25.8) | 5,691 (21.2) | 3,941 (14.7) | 26,870 (100) |

| Distinct ICU stays b) | 12,648 (39.8) | 8,141 (25.6) | 6,367 (20.0) | 4,626 (14.6) | 31,782 (100) |

| Matched waveforms c) | 2,313 (18.3) | 673 (8.3) | 1,195 (18.8) | 798 (17.3) | 4,979 (15.7) |

| Age (yr)d) | 64.5 (50.1, 78.2) | 61.1 (46.7, 75.9) | 67.1 (57.0, 76.2) | 71.4 (58.9, 80.7) | 65.5 (51.9, 77.7) |

| Gender (male) c) | 6,301 (49.8) | 4,701 (57.7) | 4,147 (65.1) | 2,708 (58.5) | 17,857 (56.2) |

| ICU length of stay (day) d) | 2.1 (1.1, 4.3) | 2.4 (1.2, 5.4) | 2.1 (1.1, 4.1) | 1.9 (1.0, 3.5) | 2.1 (1.1, 4.3) |

| Hospital length of stay (day) d) | 7 (4, 13) | 8 (5, 16) | 8 (5, 12) | 5 (3, 9) | 7 (4, 13) |

| First day SAPS I d) | 13 (10, 17) | 14 (10, 17) | 17 (14, 20) | 12 (9, 15) | 14 (10, 18) |

| Mechanical ventilation c) | 4,202 (33.2) | 4,131 (50.7) | 5,152 (80.9) | 1,076 (23.3) | 14,561 (45.8) |

| Swan-Ganz hemodynamic monitoring c) | 366 (2.9) | 1,066 (13.1) | 4,137 (65.0) | 1,086 (23.5) | 6,655 (20.9) |

| Invasive arterial blood pressure monitoringc) | 3,944 (31.2) | 5,343 (65.6) | 5,545 (87.1) | 2,054 (44.4) | 16,886 (53.1) |

| Use of vasoactive medications c) | 2,859 (22.6) | 1,982 (24.4) | 4,397 (69.1) | 1,334 (28.8) | 10,572 (33.3) |

| Hospital mortality c) | 1,645 (16) | 842 (12.2) | 213 (3.7) | 392 (10.0) | 3,092 (11.5) |

This table is an updated version of Table 2 in Saeed et al. [1], which is based on version 2.4.

MICU: medical intensive care unit, SICU: surgical intensive care unit, CSRU: cardiac surgery recovery unit, CCU: coronary care unit, SAPS: Simplified Acute Physiological Score.

no (% of total admissions).

b) no (% of total ICU stays).

c) no (% of unit stays).

median (first quartile, third quartile).

Among the adults, the overall median ICU and hospital lengths of stay were 2.1 and 7 days, respectively. CSRU patients were characterized by high utilization of mechanical ventilation, Swan-Ganz, invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring, and vasoactive medications. Overall, 45.8% and 53.1% of all adult ICU stays utilized mechanical ventilation and invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring, respectively. In-hospital mortality rate was highest in the MICU (16%) and lowest in the CSRU (3.7%). The overall in-hospital mortality was 11.5%.

The ensuing sections describe a few representative projects in progress.

A. Outcome of Critically Ill Patients with Acute Kidney Injury Using the AKIN Criteria

Acute kidney injury (AKI) affects 5-7% of all hospitalized patients with a much higher incidence in the critically ill. Although AKI carries considerable morbidity and mortality it has historically been vaguely dened, with more than 35 denitions of AKI having been used in the literature. This situation is a cause of confusion as well as an ill dened association between acute renal dysfunction and morbidity and mortality. Hence, in 2002 the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) dened universal criteria for AKI which was revised in 2005 by the Acute Kidney Injury Network (AKIN). The American Thoracic Society in a recent statement aimed to reduce the occurrence of AKI emphasized the role of urine output (UO) measurements in the early detection of AKI. As of now only a small number of large population studies have been performed and none of them used valid hourly UO measurements in order to detect AKI. We therefore preformed a retrospective cohort study assessing the inuence of AKI, including UO, on hospital mortality in critically ill patients.

This study [7] utilized adult patients admitted to BIDMC ICUs between 2001 and 2007 in MIMIC-II. We included all adult patients who had at least 2 creatinine (CR) measurements and who had at least one 6 hours period with 3 bi-hourly UO measurements. Patients who had end stage renal disease were excluded from the cohort. We applied the AKIN criteria by using CR measurements and hourly UO from nursing reports and classified the patients by their worst combined (UO or CR) AKI stage.

19,677 adult patient records were assessed. After exclusion of patients who did not meet the inclusion criteria, the cohort included 17,294 patients. 52.5% of the patients developed AKI during their ICU stay. AKI 1 was the most frequent stage of AKI (36%) followed by AKI 2 (12.5%) and AKI 3 (4%). Hospital mortality rates were higher in all patients that were found to have AKI (15.5% vs. 3% in patients with no AKI; p<0.0001). In-hospital mortality rates by stage of AKI were 7.6%, 9.7% and 24.7% for AKI 1, 2 and 3, respectively, compared to only 3% in patients without AKI (p<0.0001). After adjusting for multiple covariates (age, gender, comorbidities, admission non-renal SOFA score) using multivariate logistic regression, AKI was associated with increased hospital mortality (OR 1.3 for AKI 1 and AKI 2 and 2.6 for AKI 3; p<0.0001, AUC=0.79).

Using the same multivariate logistic regression, we found that in patients who developed AKI, UO alone was a better mortality predictor then CR alone or the combination of both: (AKI 1 - AUC(UO)=0.741 vs. AUC(CR)= 0.714 or AUC(BOTH)=0.713; p=0.005. AKI 2 - AUC(UO) =0.722 vs. AUC(CR)=0.655 or AUC(BOTH)=0.694; p=0.001. AKI 3 - AUC (UO)=0.763 vs. AUC(CR)=0.66 or AUC(BOTH)=0.661; p=0.001).

B. Long Term Outcome of Minor Troponin Elevations in the ICU

Serum troponin assay is an integral part in the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. The term troponin leak refers to a slight elevation and without a clinical diagnosis of an infarction. There are very few studies looking at its significance in the critical care setting as regards long-term outcome. Using the MIMIC-II database, patients with a troponin level >0.01 but <0.5 and without a diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome will be identified. All these patients were admitted in the ICU (MICU, SICU, CCU, and CSRU) from 2001 to 2008 at BIDMC. The purpose of this study is to determine whether the troponin level is associated with 1-year survival among these patients. ICU and hospital length-of-stay will also be assessed as secondary outcomes. Cox and logistic regression models will be adjusted for age, Simplified Acute Physiologic Score (SAPS), Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) and Elixhauser scores. This analysis will give additional information with regard to clinical application of this indeterminate range of troponin level.

C. Quantifying the Risk of Broad-spectrum Antibiotics

Current evidence-supported best practice for the management of bacterial sepsis includes the prompt administration of parenteral antimicrobials targeted toward the suspected source of infection. When a diagnosis of a noninfectious etiology of hypoperfusion is made, empiric antimicrobials are no longer indicated. The objective of this study is to quantify the impact of antimicrobial exposure on clinical outcomes including mortality, length of stay, adverse effects of antimicrobials, and acquisition of antimicrobial-resistant organisms. The study population will include patients admitted to the intensive care unit from the emergency department at BIDMC with a diagnosis of sepsis and/or shock, who are started on broad-spectrum antimicrobials on admission, and who have blood cultures obtained on admission that are subsequently negative. A case-control study will be performed comparing clinical outcomes among patients receiving parenteral antimicrobials for >48 hours after admission (cases) and those receiving parenteral antimicrobials <48 hours after admission (controls).

IV. DISCUSSION

We introduce an approach to decision support using one’s own clinical database as an alternative to built-in expert systems derived from published large, usually multicenter, interventional and observational studies. Clinical trials tend to enroll heterogeneous groups of patients in order to maximize external validity of their findings. As a result, recommendations that arise from these studies tend to be general and applicable to the average patient. Similarly, predictive models developed using this approach perform poorly when applied to specific subsets of patients or patients from a different geographic location as the initial cohort [8].

Using a clinical database, we demonstrated accurate prediction of fluid requirement of ICU patients who are receiving vasopressor agents using the physiologic variables during the previous 24 hours in the ICU [9]. Subsequently, we demonstrated improved mortality prediction among ICU patients who developed acute kidney injury by building models on this subset of patients [10].

Clinical databases may also address evidence gaps not otherwise filled by prospective randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The breadth of clinical questions that can be answered with these studies is limited by their high resource demands, and the quality of data they produce also has challenges. In one study [11], Ioannidis demonstrated that researchers’ findings may frequently be incorrect. Challenges with many clinical studies are extensive, including the questions researchers pose, how studies are designed, which patients are recruited, what measurements are taken, how data are analyzed, how results are presented, and which studies are published. They typically enroll a heterogeneous group of patients in order to maximize external validity of their findings. However, their findings represent a range of individual outcomes which may not be applicable to an individual patient. In another study by Ioannidis [12], he examined 49 highlycited clinical research studies and found that 45 articles reported a statistically significant treatment effect, but 14 of 34 articles (41%) which were retested concluded that the original results were incorrect or significantly exaggerated. Systematic reviews also face challenges. While frequently cited as evidence to guide clinical guidelines and healthcare policy, they rarely provide unequivocal conclusions. A 2007 analysis of 1,016 systematic reviews from all 50 Cochrane Collaboration Review Groups found that 49% of studies concluded that current evidence “did not support either benefit or harm” [13]. In 96% of the reviews, further research was recommended.

In MIMIC-II, we have successfully created a publicly available database for the intensive care research community. MIMIC-II is a valuable resource, especially for those researchers who do not have easy access to the clinical intensive care environment. Furthermore, research studies based on MIMIC-II can be compared with one another in an objective manner, which would reduce redundancy in research and foster more streamlined advancement in the research community as a whole.

The diversity of data types in MIMIC-II opens doors for a variety of research studies. One important type of research that can stem from MIMIC-II is the development and evaluation of automated detection, prediction, and estimation algorithms. The high temporal resolution and multi-parameter nature of MIMIC-II data are suitable for developing clinically useful and robust algorithms. Also, it is easy to simulate a real-life ICU in offline mode, which enables inexpensive evaluation of developed algorithms without the risk of disturbing clinical staff. Previous MIMIC-II studies in this research category include hypotensive episode prediction [14] and robust heart rate and blood pressure estimation [15]. Additional signal processing studies based on MIMIC-II include false arrhythmia alarm suppression [16] and signal quality estimation for the electrocardiogram [17].

Another type of research that MIMIC-II can support is retrospective clinical studies. While prospective clinical studies are expensive to design and perform, retrospective studies are inexpensive, demand substantially less time-commitment, and allow flexibility in study design. MIMIC-II offers severity scores such as the Simplified Acute Physiological Score I [18] and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment [19] that can be employed in multivariate regression models to adjust for differences in patient conditions. For example, Jia and colleagues [20] investigated risk factors for acute respiratory distress syndrome in mechanically ventilated patients, and Lehman and colleagues [21] studied hypotension as a risk factor for acute kidney injury.

MIMIC-II users should note that real-life human errors and noise are preserved in MIMIC-II since no artificial cleaning or filtering was applied. Although this presents a challenge, it also is an opportunity for researchers to work with real data and address pragmatic issues.

Because MIMIC-II is a single-center database originating from a tertiary teaching hospital, research results stemming from MIMIC-II may be subject to institutional or regional bias. However, many research questions can be answered independent of local culture or geographic location (e.g., the focus of the study is physiology).

A successful MIMIC-II study requires a variety of expertise. While clinically-relevant research questions would best come from clinicians, reasonable database and computer skills are necessary to extract data from MIMIC-II. Hence, a multi-disciplinary team of computer scientists, biomedical engineers, biostatisticians, and intensive care clinicians is strongly encouraged in designing and conducting a research study using MIMIC-II.

There is a long road ahead before our vision of probabilistic modeling at the point-of-care to assist clinicians with contextual questions regarding individual patients becomes a reality. Non-trivial pre-processing and processing issues when mining large high-resolution clinical databases abound. Mechanisms to close the information loop should be in place to feed the new information back to clinicians. There should be dedicated personnel consisting of data engineers and clinical informaticians to operationalize this learning system. More importantly, impact studies are necessary to evaluate whether this approach will influence clinician behavior and improve patient outcomes.

V. CONCLUSION

We described the framework of a learning system that facilitates the routine use of empiric data as captured by electronic information systems to address areas of uncertainty during day-to-day clinical practice. While evidence-based medicine has overshadowed empirical therapies, we argue that each patient interaction, particularly when recorded with granularity in an easily accessible and computationally convenient electronic form, has the potential to aggregate and analyze daily mini-experiments that occur in areas where standards of care do not exist. Clinical databases such as MIMIC-II can complement knowledge gained from traditional evidence-based medicine and can provide important insights from routine patient care devoid of the influence of artificiality introduced by research methodologies. As a meta-research tool, clinical databases where recorded health care transactions - clinical decisions linked with patient outcomes - are constantly uploaded, become the centerpiece of a learning system that accelerates both the accrual and dissemination of knowledge.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by grant R01 EB001659 from the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and Philips Healthcare. The authors of this article would like to acknowledge the following people for their contributions to the development of MIMIC-II: Mauricio Villarroel, Gari D. Clifford, Mohammed Saeed, Tin H. Kyaw, Benjamin E. Moody, George B. Moody, Ishna Neamatullah, Margaret Douglass, William H. Long, Li-Wei H. Lehman, Xiaoming Jia, Michael Craig, Larry Nielsen, Greg Raber, and Brian Gross.

Biography

Leo Anthony Celi

Dr. Leo Anthony Celi is an internist, an intensive care unit (ICU) doctor, and an infectious disease specialist, who has practiced medicine in 3 continents, giving him broad perspectives in healthcare delivery. In addition, he pursued a master’s degree in biomedical informatics at MIT and a master’s degree in public health at Harvard University. His research projects are in the field of clinical data mining, health information systems and quality improvement. He is now on staff at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center ICU and the Laboratory of Computational Physiology at MIT. He also directs Sana (sana.mit.edu) at the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory at MIT.

Joon Lee

Dr. Joon Lee is a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Laboratory for Computational Physiology at the Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology. He received a B.A.Sc. degree in electrical engineering from the University of Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, and a Ph.D. degree from the Biomedical Group of the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at the University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada. His research interests lie in the domains of medical informatics, biomedical signal processing, machine learning, pattern recognition, and data mining, with a motivation to make the current healthcare system more efficient and cost-effective. Currently, his primary research focus is on the NIH-funded research program, “Integrating Data, Models, and Reasoning in Critical Care”. His research activities range from retrospective clinical studies to development of automated clinical decision support algorithms. He currently holds a Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC).

Daniel J. Scott

Dr. Scott is a Research Engineer in the Laboratory for Computational Physiology at the Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology. His work is concentrated on the R01 NIH-funded research program, “Integrating Data, Models, and Reasoning in Critical Care”. One of the project’s aims is to develop the MIMIC-II database, a large repository of clinical data obtained from the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Initially a physicist, and then a chemist, his PhD thesis explored the application of artificial intelligence and machine learning for the development of novel ceramic oxides. Dr. Scott’s current research involves the application of the same techniques to the medical data found within the MIMIC-II database. In addition Dr. Scott is particularly interested in the development of Open Source tools for the analysis and modeling of data.

Trishan Panch

Trishan is the inaugural recipient of the Harvard School of Public Health’s Public Health Innovator award. He is a Lecturer in Health Sciences and technology at MIT. He leads the team at Sana Mobile, an MIT-based research group working to develop mobile health technology for developing countries, that won the 2010 Vodafone and mHealth Alliance Wireless Innovation Award. He won the 2011 Harvard Business School Business Plan competition as part of the Sana Care team.

He has a Medical Degree and BSc in Health Management from Imperial College London, a Masters in Public Health from the Harvard School of Public Health and holds membership of the UK Royal College of General Practitioners with Merit. For more information: www.hybridvigour.net

Roger G. Mark

Roger G. Mark earned SB and PhD degrees in electrical engineering from Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the MD degree from Harvard Medical School. He trained in internal medicine with the Harvard Medical Unit at Boston City Hospital, and then spent two years in the Medical Corps of the United States Air Force studying the biological effects of laser radiation. He subsequently joined the faculties of the EE Department at MIT and the Harvard Medical School. His early research interests were in the areas of medical instrumentation, ECG arrhythmia analysis, and geographically distributed health care systems (telemedicine). At present Dr. Mark is Distinguished Professor of Health Sciences and Technology, and Professor of Electrical Engineering at MIT. He remains active in the part-time practice of internal medicine with a focus on geriatrics, is Senior Physician at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and Assistant Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School. His current research activities include “Integrating Data, Models, and Reasoning in Critical Care” (http://mimic.mit.edu) and “PhysioNet” (http://www.physionet.org), both of which involve physiological signal processing, cardiovascular modeling, and the development and open distribution of large physiological and clinical databases.

REFERENCES

- 1.Saeed M, Villarroel M, Reisner AT, Clifford G, Lehman L, Moody G, Heldt T, Kyaw TH, Moody B, Mark RG. Multiparameter Intelligent Monitoring in Intensive Care II (MIMIC-II): a public-access intensive care unit database. Critical Care Medicine. 2011;39(5):952–960. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31820a92c6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Price J. Oracle Database 11g SQL. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.PhysioNet The WFDB software package. http://www.physionet.org/physiotools/wfdb.shtml.

- 4.Craig MB, Moody BE, Jia S, Villarroel MC, Mark RG. Matching data fragments with imperfect identifiers from disparate sources. Computing in Cardiology. 2010;37:793–796. [Google Scholar]

- 5.PhysioNet De-identification: software and test data. http://www.physionet.org/physiotools/deid/

- 6.Neamatullah I, Douglass MM, Lehman LH, Reisner A, Villarroel M, Long WJ, Szolovits P, Moody GB, Mark RG, Clifford GD. Automated de-identification of free-text medical records. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making. 2008;8:32. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-8-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mandelbaum T, Scott DJ, Lee J, Mark RG, Malhotra A, Waikar SS, Howell MD, Talmor D. Outcome of critically ill patients with acute kidney Injury using the Acute Kidney Injury Network criteria. Critical Care Medicine. 2011;39(12):2659–2664. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182281f1b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strand K, Flaatten H. Severity scoring in the ICU: a review. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 2008;52(4):467–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2008.01586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Celi LA, Hinske LC, Alterovitz G, Szolovits P. Artificial intelligence to predict fluid requirement in the ICU: a proof-of-concept study. Critical Care. 2008;12(6):R151. doi: 10.1186/cc7140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Celi LA, Tang RJ, Villarroel MC, Davidzon GA, Lester WT, Chueh HC. A clinical database-driven approach to decision support: predicting mortality among patients with acute kidney injury. Journal of Healthcare Engineering. 2011;2(1):97–110. doi: 10.1260/2040-2295.2.1.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ioannidis JP. Why most published research findings are false. Public Library of Science Medicine. 2005;2(8):e124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ioannidis JP. Contradicted and initially stronger effects in highly cited clinical research. JAMA. 2005;294(2):218–228. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El Dib RP, Atallah AN, Andriolo RB. Mapping the Cochrane evidence for decision making in health care. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2007;13(4):689–692. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2007.00886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee J, Mark RG. An investigation of patterns in hemodynamic data indicative of impending hypotension in intensive care. BioMedical Engineering OnLine. 2010;9:62. doi: 10.1186/1475-925X-9-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Q, Mark RG, Clifford GD. Artificial arterial blood pressure artifact models and an evaluation of a robust blood pressure and heart rate estimator. BioMedical Engineering Online. 2009;8:13. doi: 10.1186/1475-925X-8-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aboukhalil A, Nielsen L, Saeed M, Mark RG, Clifford GD. Reducing false alarm rates for critical arrhythmias using the arterial blood pressure waveform. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2008;41(3):442–451. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Q, Mark RG, Clifford GD. Robust heart rate estimation from multiple asynchronous noisy sources using signal quality indices and a Kalman filter. Physiological Measurement. 2008;29(1):15–32. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/29/1/002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Le Gall JR, Loirat P, Alperovitch A. Simplified acute physiological score for intensive care patients. Lancet. 1983;322(8352):741. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)92278-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vincent JR, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, Mendonça A, Bruining H, Reinhart CK, Suter PM, Thijs LG. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. Intensive Care Medicine. 1996;22(7):707–710. doi: 10.1007/BF01709751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jia X, Malhotra A, Saeed M, Mark RG, Talmor D. Risk factors for ARDS in patients receiving mechanical ventilation for > 48 h. Chest. 2008;133(4):853–861. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lehman L, Saeed M, Moody G, Mark R. Hypotension as a risk factor for acute kidney injury in ICU patients. Computing in Cardiology. 2010;37:1095–1098. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]