Abstract

The neocortex plays a key role in higher-order brain functions, such as perception, language and decision-making. Since the groundbreaking work of Ramón y Cajal over a century ago, defining the neural circuits underlying brain functions has been a field of intense study. Here, we review recent findings on the formation of neocortical circuits, which have taken advantage of improvements to mouse genetics and circuit-mapping tools. These findings are beginning to reveal how individual components of circuits are generated and assembled during development, and how early developmental processes, such as neurogenesis and neuronal migration, guide precise circuit assembly.

Keywords: Lineage, Neuronal circuits, Neocortex

Introduction

The mammalian cerebral cortex is composed of the archicortex (hippocampal region), the paleocortex (olfactory cortex) and the neocortex, with the last being the evolutionarily youngest region. The neocortex is composed of two major classes of neurons: glutamatergic projection neurons (see Glossary, Box 1), which elicit excitation in postsynaptic neurons and generate circuit output; and GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid)-ergic interneurons (see Glossary, Box 1), which typically trigger inhibition in postsynaptic neurons and are essential for shaping circuit output. It is generally accepted that two defining structural and functional features of the neocortex are lamination and radial columns (Douglas and Martin, 2004). Together, these features provide the basic framework on which neocortical circuits are built. Interestingly, both of these features are tightly linked to early developmental events, including neurogenesis and neuronal migration. In this Review, we discuss recent findings on the generation, migration and organization of excitatory and inhibitory neurons in the neocortex, with a focus on how the lineage history of neurons influences the assembly of functional circuits.

Box 1. Glossary

Cortical plate. A progressively thickening layer in the dorsal telencephalon that harbors newly born post-mitotic neurons and eventually develops into the future cortex.

Hebbian learning rule. ‘Cells that fire together, wire together’: a theory introduced by Donald O. Hebb (Hebb, 1949) for the mechanism of synaptic plasticity whereby repeated and persistent stimulation of the postsynaptic cell by a presynaptic cell increases synaptic efficacy.

Interneurons. Inhibitory neurons with short axons in the cortex that typically participate in only local circuits.

Marginal zone. A superficial layer that develops as the preplate is split during early corticogenesis; it eventually becomes layer 1 of the mature cortex.

Pia (or pia mater). Innermost layer of the meninges that surrounds the brain and spinal cord.

Preplate. Located between the pia and the ventricular zone, it contains the earliest born neurons and represents the beginning of corticogenesis prior to the emergence of the cortical plate.

Projection neurons. Excitatory neurons in the cortex that send long-range projections to different brain regions.

Radial glial cells. A major population of neural stem cells transiently existing in the developing brain that are crucial for generating neurons and glia.

Striatum. A subcortical structure derived from ventral regions of the developing telecephalon that receives input from the cortex.

Subplate. A transient zone comprising of some of the earliest generated neurons in the cortex; it is crucial for both structural and functional development of the cortex.

Subventricular zone. A region situated above the ventricular zone that harbors intermediate progenitor cells and migrating neurons.

Telencephalon. The anteriormost region of the developing CNS that gives rise to the mature cerebrum.

Lamination: a hallmark of the neocortex

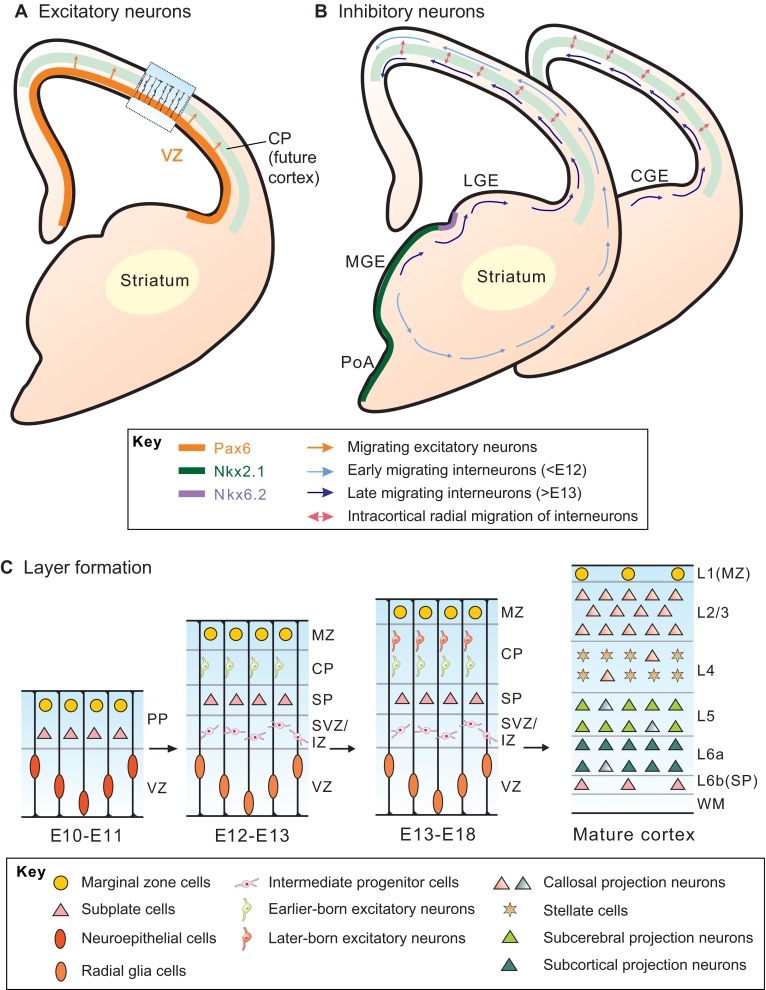

The neocortex is a continuous six-layered structure. All components of neocortical circuits, including afferents, excitatory cells, inhibitory cells and efferents, are organized with respect to the laminae (Douglas and Martin, 2004). Cortical lamination is generated as a result of radial migration of newborn excitatory neurons during development (Hatten, 1999; Rakic, 1971; Rakic, 1972). Glutamatergic excitatory neurons are produced from progenitor cells (Fig. 1A) that reside in the proliferative zone of the dorsal telencephalon (see Glossary, Box 1). In the earliest stages, the neural tube is composed of a single layer of neuroepithelial (NE) cells that proliferate rapidly (Breunig et al., 2011). A small fraction of NE cells undergoes asymmetric division to generate the first wave of postmitotic neurons, which migrate out radially and form a transient structure called the preplate (see Glossary, Box 1) (Del Río et al., 2000; Marin-Padilla, 1970; Marin-Padilla, 1971; Marin-Padilla, 1978). As development proceeds, NE cells transform into a more fate-restricted progenitor type: radial glial cells (RGCs, see Glossary, Box 1), a major population of neuronal progenitors in the dorsal telencephalon (Anthony et al., 2004; Fishell and Kriegstein, 2003; Malatesta et al., 2000; Malatesta et al., 2003; Miyata et al., 2001; Noctor et al., 2001; Noctor et al., 2004). Residing in the ventricular zone (VZ), RGCs display a characteristic bipolar morphology with a short apical process (the ventricular endfoot) that reaches the luminal surface of the VZ and an elongated process (the radial glial fiber) that extends basally to the surface of the pia (see Glossary, Box 1). It is generally believed that RGCs undergo symmetric division to expand the progenitor pool, and then switch to asymmetric division where they self-renew and simultaneously generate daughter cells that are either postmitotic neurons or intermediate progenitor cells (IPCs). IPCs then undergo additional rounds of symmetric division in the subventricular zone (SVZ, see Glossary, Box 1)to produce neurons (Kowalczyk et al., 2009; Noctor et al., 2004). Newborn neurons undertake radial glial fiber-guided radial migration, splitting the existing preplate into a superficial marginal zone (MZ, see Glossary, Box 1) and a deeper subplate (SP, see Glossary, Box 1), and reside in the middle region, leading to the formation of the cortical plate (CP, see Glossary, Box 1) - the future cortex. Successive waves of newly generated neurons migrate past the existing early-born neurons and occupy more superficial layers in the CP, creating cortical layers (L) 2-6. Thus, cortical lamination occurs in an ‘inside-out’ fashion (Angevine and Sidman, 1961) (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Generation and migration of neocortical excitatory and inhibitory neurons. (A,B) Excitatory and inhibitory neurons originate from different germinal zones of the embryonic telencephalon. (A) Cortical excitatory neurons are generated from progenitor cells (Pax6+, orange) residing in the ventricular zone (VZ) of the dorsal telencephalon. Newborn excitatory neurons undergo radial glial fiber-guided radial migration (orange arrows) and settle into the developing cortical plate (CP, light green). (B) Cortical inhibitory interneurons are predominantly generated from progenitor cells located in the proliferative zone of the ventral telencephalon, mainly within the medial ganglionic eminence (MGE; contains Nkx2.1+ cells, dark green) and the caudal ganglionic eminence (CGE). A small population of cortical inhibitory interneurons is produced from the preoptic area (PoA). Newborn inhibitory interneurons follow two tangentially oriented migratory streams to enter the cortex: a superficially migrating early cohort (pale-blue arrows) migrates through the marginal zone, and a deeply migrating second and more prominent cohort (dark-blue arrows) migrates through the lower intermediate zone and subventricular zone. Upon reaching the cortex, they switch to radial migration (pink double-headed arrows) and settle into their final laminar position in the CP. (C) Inside-out fashion of cortical layer (L) formation. In early developmental stages (E10-E11), the neural tube is composed of a single layer of neuroepithelial cells. A small fraction of these undergo asymmetric division to generate the first wave of postmitotic neurons that migrate out radially and form the preplate (PP). As development proceeds (E12-E13), newborn excitatory neurons split the PP into a superficial marginal zone (MZ) and a deeper subplate (SP). Successive waves of newly generated excitatory neurons migrate past the existing neurons to occupy a more superficial region in the CP (E13-E18), creating the mature six-layered cortex. Excitatory neurons in the mature cortex are heterogeneous. IZ/SVZ, intermediate zone/subventricular zone; WM, white matter.

It is becoming increasingly clear that the progenitor cells for excitatory neurons are not homogeneous, but rather diverse. In addition to RGCs and IPCs, two new types of neuronal progenitor cells were recently discovered in the developing neocortex: short neural precursors (SNPs) and outer subventricular zone (OSVZ) radial glial progenitors. SNPs maintain their ventricular end-feet but their basal processes are of variable length (Gal et al., 2006) and, unlike RGCs, they generate neurons directly instead of going through an IPC stage (Stancik et al., 2010). OSVZ progenitors, by contrast, maintain the basal processes but lack the apical processes, and are capable of undergoing asymmetric division in the OSVZ. They were initially discovered in humans and later found in primates, ferrets, mice and other species (Fietz et al., 2010; Hansen et al., 2010; Kelava et al., 2012; Shitamukai et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2011). Notably, the abundance of the OSVZ progenitor population and their increased proliferative potential has been suggested to underlie the evolutionary expansion of the cortex from mouse to human (Lui et al., 2011). To add to the progenitor heterogeneity, a recent study indicated that a subset of RGCs expressing the homeobox protein cut-like 2 (Cux2) is pre-specified to give rise to upper-layer neurons (L2-4). The Cux2-expressing RGCs proliferate early in development when lower-layer neurons (L5-6) are generated, and only start to produce neurons at later stages (Franco et al., 2012). This is at odds with the prevailing model of neocortical neurogenesis through progressive fate restriction (Desai and McConnell, 2000; Frantz and McConnell, 1996; Luskin et al., 1988; McConnell and Kaznowski, 1991; Price and Thurlow, 1988; Shen et al., 2006; Tan et al., 1998; Walsh and Cepko, 1988); additional studies, such as systematic and precise clonal/lineage analysis of individual progenitor cells (e.g. Cux2 expressing versus non-Cux2 expressing), are required to resolve this discrepancy and to better understand the progenitor heterogeneity with regards to the generation of diverse neuron types in the neocortex.

In the mature neocortex, L1 mainly contains distal tufts of pyramidal cell apical dendrites, axon terminations, Cajal-Retzius cells and some GABAergic cells, but lacks excitatory neurons. L2/3 predominantly consists of callosal projection neurons, which project their axon collaterals across the corpus callosum and mediate the communication between the two cerebral hemispheres, in addition to participating in local circuits. In primary sensory areas, L4 contains spiny stellate cells, which form an important population for thalamic innervation. L5/6 contains largely corticofugal projection neurons that provide major cortical output to the thalamus, midbrain, spinal cord and other brain regions, as well as a small population of callosal projection neurons (Molyneaux et al., 2007; Fame et al., 2011). Importantly, the corticofugal projection neurons in L5 are morphologically and physiologically heterogeneous, depending on their long-range projection targets (Hattox and Nelson, 2007). In fact, the projection identity of L5 neurons is regulated by a network of transcription factors (Srinivasan et al., 2012). L6 neurons are also diverse, with at least two broad categories based on their morphology and physiological properties (Thomson and Lamy, 2007) (Fig. 1C, right). Interneurons are present in all layers and mainly contribute to local circuitry (Markram et al., 2004).

In 1989, in trying to understand the rules that govern the synaptic connections between different neuronal types in different layers of the neocortex, Douglas and Martin developed the model of a ‘canonical cortical microcircuit’ based on electrophysiological and modeling studies in the cat visual cortex. Their model contains three groups of neurons: superficial pyramidal cells, deep pyramidal cells and a common pool of inhibitory cells. All three groups are interconnected, while thalamic input mainly targets superficial pyramidal cells and inhibitory cells. These connections allow the circuit to amplify transient thalamic input while maintaining the balance of excitation and inhibition (Douglas and Martin, 1991; Douglas et al., 1989). Subsequent studies demonstrated that the most frequently connected cells were located in the same layer, whereas interlaminar connections are dominated by feedforward connections from L4 to L3 and from L3 to L5 (Thomson et al., 2002; reviewed by Bastos et al., 2012). Based on substantial studies, we now know that in the canonical microcircuit of the neocortex, thalamic relay cells provide input into the cortex and mainly target L4, although they also form synapses with neurons in other layers. This input is relatively weak, and is amplified by recurrent excitation of L4 excitatory neurons. Recurrent excitation can be potentially detrimental in leading to hyper-excitation of the circuit; inhibition is therefore required to modulate this excitation. Within all layers, excitatory and inhibitory neurons form recurrent connections. Between cortical layers, information flow has a strong directional tendency: from L4 up to L2/3 and then down to L5/6. There is also a weaker projection from L4 directly down to L5/6. The principles of the canonical microcircuit can be applied to other cortical areas, such as the motor cortex, suggesting that they may reflect the underlying organization of the entire neocortex (Douglas and Martin, 2007). This model has greatly advanced our understanding of the wiring principle for cortical circuits. Nonetheless, recent studies also suggest that there may be some variations in circuit organization in certain cortical areas, e.g. the rodent somatosenstory cortex (Bruno and Sakmann, 2006; Meyer et al., 2010; Oberlaender et al., 2012; Wimmer et al., 2010). In summary, substantial work has demonstrated a precise orchestration of neuronal production and migration leads to the formation of distinct cortical lamina, each of which contains unique populations of neurons poised for the assembly of highly organized circuits.

The neocortical column

The second fundamental feature of the neocortex is the functional column. The concept of the ‘neocortical functional column’ was first introduced by Mountcastle in 1957 and has proven invaluable in understanding the functional organization of the neocortex. When recording the somatosensory cortex of cats and monkeys, Mountcastle and colleagues discovered that neurons sharing common functional properties, including corresponding peripheral receptors, receptive fields and firing latencies, were located in a radial column extending from pial surface to white matter (Mountcastle, 1957; Powell and Mountcastle, 1959). The diameter of columns is of approximately same size in both cats and monkeys. The functional properties of neurons are similar within a column, but significantly differ between adjacent columns (Mountcastle, 1997).

Seminal work by Hubel and Wiesel in the 1960s and 1970s then triggered tremendous interest in studying the neocortical column. Echoing Mountcastle’s observation in the somatosensory cortex, they found that, in the visual cortex of cats, neurons with a similar orientation selectivity were located in a single radial penetration from pial surface to white matter (termed ‘orientation columns’) (Hubel and Wiesel, 1962; Hubel and Wiesel, 1963). Later, they found that the two eyes differentially activated cortical neurons: neurons with similar eye preference were also grouped into columns (termed ‘ocular dominance columns’), and left and right eye-dominated columns alternated across the cortex (Wiesel and Hubel, 1963). The relationship between orientation columns and ocular dominance columns was summarized in their classic ice-cube diagram, in which thin orientation slabs cut the coarser ocular dominance columns at right angles (Hubel and Wiesel, 1977).

Similar functional columns were also discovered in the cat primary auditory cortex (Abeles and Goldstein, 1970) and in many other cortical areas (Mountcastle, 1997). These observations prompted a deep thought that ‘the cells behave as though they shared certain connections among themselves, but not with cells of neighboring columns, and in this sense a single group of cells is looked upon as a more or less autonomous functional unit’ (Hubel and Wiesel, 1974). Importantly, however, columns are not isolated; in fact, extensive studies have demonstrated horizontal connections between columns, especially between those with similar functional properties (Bosking et al., 1997; Gilbert and Wiesel, 1983; Gilbert and Wiesel, 1989; Katz et al., 1989; McGuire et al., 1991; Ts’o et al., 1986).

Despite the long history of successful identification of neocortical columns with electrophysiological recordings, especially in mammals such as cats and monkeys, the anatomical basis of these columns has remained elusive. Minicolumns have been proposed to be the basic unit of the neocortex, which are composed of chains of neurons (typically ∼80-120 in primates) spanning cortical layers whose cell bodies are vertically aligned within a diameter of ∼40-50 μm; about ∼50-80 minicolumns link together to form the structural basis of functional columns (Mountcastle, 2003). Another candidate is a related structure referred to as ‘bundles’, which mainly comprise closely associated apical dendrites of pyramidal cells whose cell bodies are located in different layers (Peters and Kara, 1987; Peters and Sethares, 1996; Peters and Walsh, 1972; Peters et al., 1997). However, both views have met ample criticism (Rockland and Ichinohe, 2004; da Costa and Martin, 2010). Whether there is a structural correlate of the functional columns remains controversial. One obvious challenge is that functional columns are defined based on the functional properties of neurons, which may not be simply reflected anatomically. A more effective search for the structural correlate of functional columns requires a precise characterization of the functional properties of individual neurons. Recent advances in the field of in vivo Ca2+ imaging provide a powerful route to reveal the functional properties of large ensembles of neurons (Ohki et al., 2005; Bock et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2011; Ko et al., 2011), effectively bridging of the gap between structure and function (Li et al., 2012).

Lineage-dependent circuit assembly of neocortical excitatory neurons

In the rodent visual cortex, the equivalent of the functional columns observed in higher mammals has proven difficult to find. This may be largely attributed to the fact that, in the horizontal dimension (i.e. within the same cortical layers), neurons with different orientation preferences are intermingled spatially in a ‘salt-and-pepper’ fashion (Ohki and Reid, 2007; Ohki et al., 2005). Similar fine-scale heterogeneity in the functional properties of neurons has been observed in the somatosensory and auditory cortices (Rothschild et al., 2010; Sato et al., 2007). These findings imply that if functional columns exist in rodents, they may be built at a single-cell resolution. Interestingly, by combining in vivo two-photon Ca2+ imaging and ex vivo patch-clamp recording techniques, Ko et al. recently demonstrated that, in L2/3 of mouse visual cortex, neurons that share orientation preference response properties are more likely to be synaptically connected, highlighting the presence of fine-scale subnetworks dedicated to processing related sensory information (Ko et al., 2011). A remaining mystery is how these highly connected subnetworks are constructed. One possibility is that neurons with similar functional properties fire at the same stimuli repeatedly and therefore gradually develop strong specific connections, as suggested by the Hebbian learning rule (see Glossary, Box 1). Alternatively, it is possible that there are other rules that govern their connectivity even before their functional properties fully emerge.

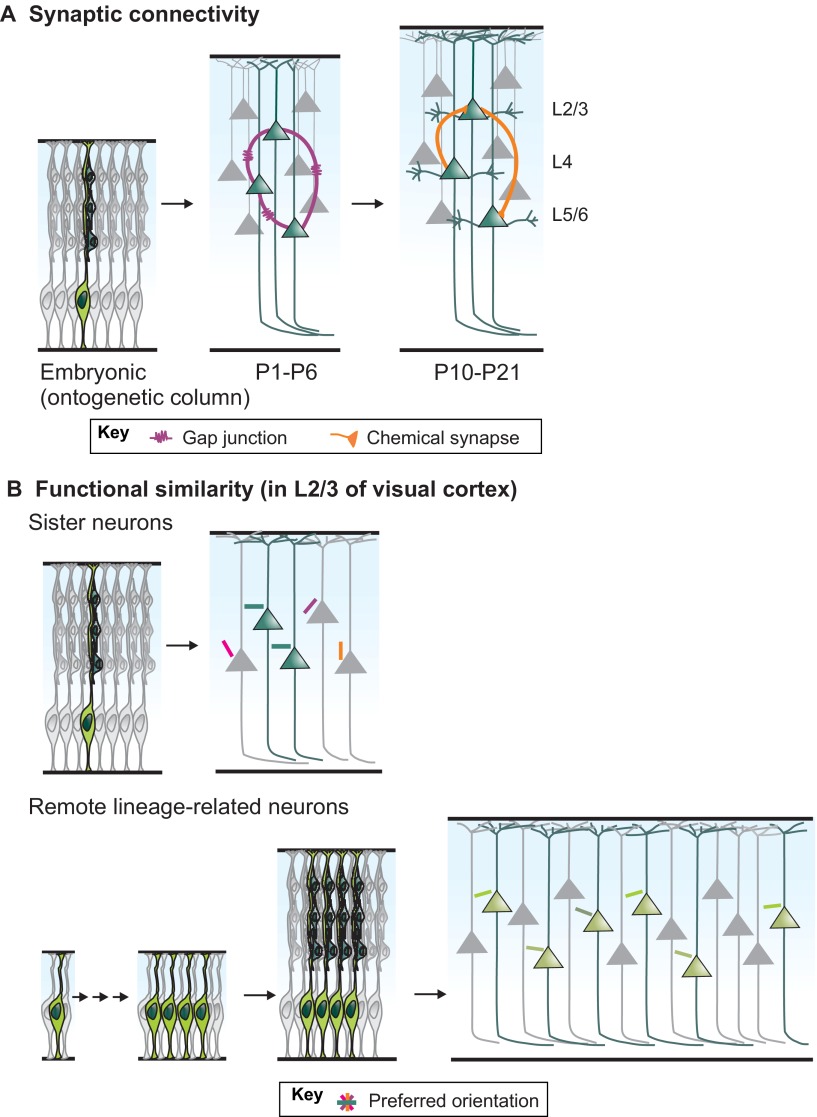

How do functional columns emerge in the developing neocortex? In 1988, Rakic proposed the ‘radial unit hypothesis’ (Rakic, 1988). According to this hypothesis, neurons derived from the same proliferative unit in the VZ migrate along the radial glial fiber(s) and form ‘ontogenetic/embryonic’ columns, which are the building blocks for the cerebral cortex. Based on the similarity of a vertical organization of neurons, it was postulated that ontogenetic columns might relate to functional columns. However, this hypothesis has only recently been tested experimentally. Yu et al. injected EGFP-expressing retroviruses intraventricularly into developing mouse embryos at embryonic days E12-E13 to label individual asymmetrically dividing RGCs, which give rise to ontogenetic columns composed of four to six vertically aligned sister excitatory neurons spanning different cortical layers. Multiple-electrode whole-cell patch clamp recordings at postnatal stages (P10-P21) revealed that sister neurons are preferentially connected by chemical synapses when compared with nearby non-sister neurons. Interestingly, the direction of interlaminar connectivity among sister neurons in an ontogenetic column resembles that observed in the mature cortex, suggesting that these ontogenetic columns could lead to the formation of functional columns in the cortex (Yu et al., 2009). Tracing this back to even earlier in development, sister neurons preferentially form transient electrical synapses with each other (peaking at ∼P1-P2, largely disappearing after P6), which allow for selective electrical communication and promote action potential generation/synchronous firing between sister neurons (Yu et al., 2012). Although these gap junctions largely disappear before functional chemical synapses can be detected, they are necessary for the formation of specific chemical synapses between sister neurons. Blockade of electrical communication impaired the subsequent assembly of lineage-related sister excitatory neurons into specific microcircuits (Yu et al., 2012). This line of studies not only demonstrates a new principle of circuit assembly that depends on the lineage relationship of neurons (i.e. on their specific developmental history), but also suggests that ontogenetic columns may contribute to the emergence of the functional columns in the neocortex (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Lineage-dependent circuit assembly of neocortical excitatory neurons. (A) Sister neurons (dark green) derived from the same RGCs during embryonic development migrate along the radial glial fiber (light green) and form ontogenetic columns. Sister neurons are preferentially coupled through electrical synapses (gap junctions, purple) in the first postnatal week. In the second postnatal week, sister neurons develop preferential chemical synapses (orange) with each other, and the direction of connectivity resembles that in the mature circuits. (B) In layer (L)2/3 of the mouse visual cortex, lineage-related neurons have similar orientation tuning response properties (colored bars). Vertically aligned sister neurons (top) labeled by retrovirus at E15-E17 have similar orientation tuning response properties, unlike those of their non-sisters. Remote lineage-related clones of neurons (bottom), labeled by a sporadically expressing Cre driver line, still have slightly more similar orientation tuning response properties compared with those of non-related neurons.

To test this directly, Li et al. used the same retrovirus-labeling technique to label sister excitatory neurons derived from the same RGCs at E15-E17 in the mouse visual cortex, and performed in vivo two-photon Ca2+ imaging to assess their orientation tuning response properties at P12-P17 (Li et al., 2012). They found that sister neurons have similar orientation preferences compared with those of nearby non-sister neurons (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, in line with the findings of Yu et al., blockade of electrical coupling between sister neurons abolished the functional similarity between sister neurons, highlighting the significance of early gap junction-mediated electrical communication in establishing specific connections between sister neurons and their shared functional properties (Li et al., 2012).

How far does the lineage relationship go in shaping neocortical circuitry? In another recent study, Ohtsuki et al. used a different approach to label lineage-related neurons (Ohtsuki et al., 2012). They used a transgenic mouse line in which Cre recombinase is expressed sparsely in progenitor cells early in forebrain development, generating individual clones containing 600-800 fluorescently labeled neurons derived from the same progenitors. They then used in vivo two-photon Ca2+ imaging to examine the orientation tuning response properties of clonally related neurons and nearby non-clonally related neurons. Interestingly, even in such a large population of neurons, the lineage relationship of which is much further away compared with that of the sister neurons labeled by Li et al., orientation preferences among clonally related neurons were still more similar than those among unrelated neurons (Fig. 2B). However, there was considerable diversity within the large clones, such that nearly one half of all neuronal pairs had preferred orientations with a difference greater than 30°, and one quarter of them exhibited a difference greater than 60° (Ohtsuki et al., 2012). One plausible explanation is that remote lineage relationship, although still influential, is not as strong as close lineage relationship (i.e. neurons derived from asymmetrically dividing RGCs) in predicting shared functional similarities among neurons. However, there might be other factors that contribute to the observed diversity. Ohtsuki et al. performed the experiments in relatively mature (P49-P62) mice whose visual system was well developed, whereas Li et al. conducted the experiments in young mice (P12-P17), close to the time of eye opening. As it is well established that neuronal activity as well as visual experience exert tremendous influence on circuit development (Cang et al., 2005; Caporale and Dan, 2008; Hubel and Wiesel, 1965; Katz and Crowley, 2002; Katz and Shatz, 1996), it is possible that lineage relationship instructs the formation of the initial neocortical circuit, which is then further modified by experience. In this regard, it will be interesting to test whether remote lineage-related neurons behave more similarly when tested in younger animals or, vice versa, whether the shared functional similarities between closely related ‘sister neurons’ persist into adulthood.

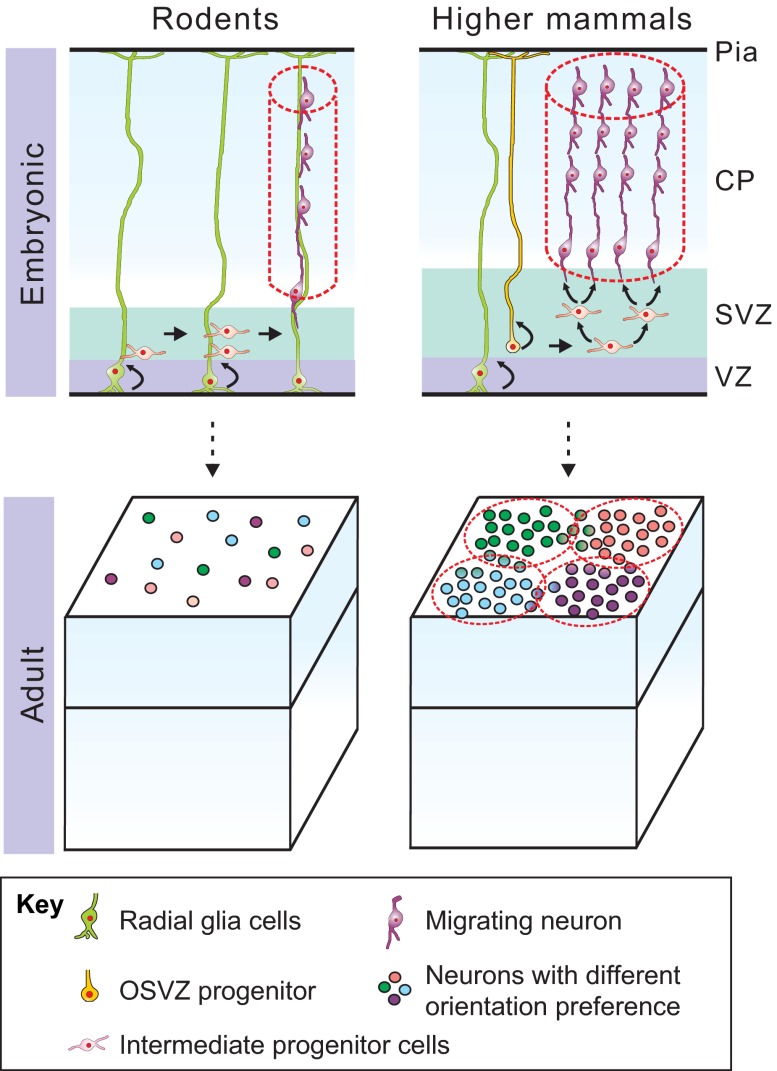

Together, these studies strongly suggest that, in the mouse, lineage plays a crucial role in organizing neocortical excitatory neuron circuits. Ontogenetic columns formed by clonally related neurons could be the basic structural and functional unit that constitutes the neocortex. One important issue is whether these lineage-related specific circuits also exist in other mammalian species, especially higher mammals such as cats and monkeys. The tremendous interspecies difference in the organization of orientation preference maps from rodents to higher mammals could be due to the differences in patterns of neurogenesis and the layout of ontogenetic columns (Fig. 3). It has been proposed that the extensive proliferation capacity of progenitor cells in the SVZ underlies cortical expansion from rodents to higher mammals, including ferrets, cats and primates (Kriegstein et al., 2006), which presumably would give rise to ontogenetic columns that are much larger in size and with many more horizontal features. Recent discoveries of OSVZ progenitors with increased amplification capability support this hypothesis (Lui et al., 2011). Interestingly, computational modeling based on the ‘wire length minimization principle’ predicts that a strong horizontal connection pattern would lead to smooth varying maps, such as those discovered in cats and monkeys. By comparison, the proliferation potential of IPCs in the SVZ of rodents is much more limited, and lack of specific horizontal connections is predicted to produce an apparent salt-and-pepper organization of maps (Koulakov and Chklovskii, 2001). It will be interesting to test whether ontogenetic columns are the long-awaited structural basis of functional columns in higher mammals. In addition, two recent studies demonstrated that neurons with certain molecular identities are arranged in a periodic manner in L5 of mouse and human neocortex (Kwan et al., 2012; Maruoka et al., 2011). It will be interesting to understand the cellular events responsible for the formation of these ‘molecular minicolumns’ and how they relate to functional columns. It is also important to note that the cellular organization of the thalamus that relays information to the neocortex appears different between rodents and higher mammals; for example, the lateral geniculate complex is distinctly laminated in cats, monkeys and humans, but not in mice and rats, and this difference may also fundamentally influence the functional organization of the cortex.

Fig. 3.

Patterns of neocortical neurogenesis may influence the organization of functional maps. In the visual cortex of rodents (left), functional columns are thought to exist at single-cell resolution, and individual embryonic/ontogenetic columns (dotted red lines) composed of a few sister excitatory neurons may lead to this organization in adults. In higher mammals (right), by contrast, functional columns with clusters of neurons sharing similar properties are observed; the expansion of the subventricular zone (SVZ) through its greater proliferative potential may significantly increase the number of neurons in individual embryonic/ontogenetic columns and contribute to the development of these functional columns in adults. CP, cortical plate; VZ, ventricular zone.

Lineage-related production and organization of inhibitory neurons

Neocortical inhibitory neurons exhibit an incredibly rich diversity of subtypes and are distributed throughout the neocortex in a stereotypical manner. Extensive studies have suggested that, as for excitatory neurons, lineage and/or the developmental history (i.e. place and time of birth) of cortical interneurons underlies their subtype specification and distribution in the mature neocortex, thereby contributing to their proper circuit assembly and function. It is important to note that, unlike excitatory neurons, very little is known about the lineage of interneurons at the single progenitor level, and most previous work has focused on interneuron lineage at the level of populations of progenitors. Nonetheless, the advent of optogenetic tools, in combination with mouse genetics, allows researchers to dissect the functional output of different classes of interneurons within cortical circuits in vivo (Cardin et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2012; Sohal et al., 2009; Wilson et al., 2012), and offers an unprecedented opportunity to understand how early developmental events and distinct lineages of interneurons contribute to the assembly of precise circuits.

Cortical inhibitory neuron development

Unlike dorsally derived excitatory neurons, GABAergic inhibitory neurons are born in transient ventral telencephalic regions known as the ganglionic eminences (GEs) (Anderson et al., 1997; Anderson et al., 2002; Butt et al., 2005; Gelman and Marín, 2010; Valcanis and Tan, 2003; Wichterle et al., 1999; Wichterle et al., 2001; Xu et al., 2004; Xu et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2008) (Fig. 1B). The GE is further subdivided into three distinct domains, namely the lateral, medial and caudal GEs (LGE, MGE and CGE, respectively). Numerous fate-mapping studies have demonstrated that the MGE and the CGE are the predominant sources of cortical interneurons (Fogarty et al., 2007; Nery et al., 2002; Xu et al., 2008). More specifically, MGE progenitor cells produce ∼70% of neocortical interneurons (Fogarty et al., 2007; Lavdas et al., 1999; Xu et al., 2008) and CGE progenitor cells give rise to the remaining 30% (Butt et al., 2005; Miyoshi et al., 2010; Nery et al., 2002). In addition, a small subpopulation (fewer than 3%) of cortical interneurons is derived from the embryonic preoptic area, which is situated in the telencephalic stalk (Gelman et al., 2009). MGE progenitors also give rise to interneurons of the striatum (see Glossary, Box 1) and are characterized by the expression of a transcription factor, the homeobox protein Nkx-2.1 (Marin et al., 2000; Sussel et al., 1999). Notably, it has been suggested that, in humans as well as non-human primates, besides the GE of the ventral telencephalon, the VZ and/or SVZ of the dorsal telencephalon also produce a substantial population of cortical GABAergic neurons (Fertuzinhos et al., 2009; Jakovcevski et al., 2011; Letinic et al., 2002; Petanjek et al., 2009). However, additional studies are needed to explore this further (Hansen et al., 2010).

In rodents, interneurons destined for the cortex must undergo a long and tortuous journey from their subpallial origins to reach the cortex. In order to avoid the developing striatum, interneurons migrate superficially or deep relative to the striatal mantle (Marín et al., 2001). Two main migratory streams of interneurons follow tangentially oriented paths to enter the cortex: a superficially migrating early cohort migrates through the MZ of the cortex (Lavdas et al., 1999); a deeply migrating second and more prominent cohort migrates predominantly through the lower intermediate zone and SVZ (Wichterle et al., 2001). Upon reaching the cortex, interneurons adopt a radial trajectory to settle into their final laminar position within the CP (Ang et al., 2003; Hevner et al., 2004; Polleux et al., 2002; Tanaka et al., 2003) (Fig. 1B).

Lineage and subtype specification

One of the most striking features of interneurons in the adult neocortex is the incredibly rich diversity they display in their morphology, biochemical marker expression, electrophysiological properties and synaptic connectivity patterns. Axons of inhibitory neurons are highly selective in the postsynaptic neuronal compartment (i.e. soma, dendritic tree or axon initial segment) that they target. The distinct subcellular targeting and firing patterns of each subtype allows populations of interneurons to exert their inhibitory influence on surrounding neurons in numerous ways, thereby shaping circuit output dynamically and allowing for a wide range of neuronal computations. For example, perisomatic inhibition controls the output of the postsynaptic neuron, and is primarily mediated by parvalbumin (PV)-containing basket cells. Dendritic inhibition, by contrast, sculpts the local input of the postsynaptic neuron, and is mainly mediated by somatostatin (SST)-expressing interneurons, which are mostly Martinotti cells (McGarry et al., 2010). PV-positive chandelier (also referred to as axo-axonic) cells exclusively target the axon initial segment of pyramidal cells and play an enigmatic role in the cortical circuit as they can be inhibitory or excitatory, depending on the membrane potential of the postsynaptic neuron and the overall activity state of the network (Pouille et al., 2009; Szabadics et al., 2006; Taniguchi et al., 2013).

Two important determinants of subtype specification of neocortical interneurons are the place of birth and the time of birth. The first level of spatial segregation of progenitors is seen when comparing the MGE and CGE, as they give rise to largely non-overlapping subtypes of cortical interneurons. The MGE generates the majority of cortical interneurons that mostly comprise PV-positive, fast-spiking basket and chandelier cells, as well as SST-positive, burst-spiking cells that include Martinotti cells. The CGE, by contrast, gives rise to a more heterogeneous population of cortical interneurons, which includes reelin-positive multipolar cells, vasointestinal peptide (VIP)-positive/calretinin (CR)-positive, bitufted, irregular spiking cells, as well as VIP-positive/CR-negative biopolar cells that display a fast-adapting firing pattern (Lee et al., 2010; Miyoshi et al., 2010; Nery et al., 2002). Within the MGE, there seems to be additional spatial bias in the specification of SST-positive and PV-positive interneurons (Flames et al., 2007; Fogarty et al., 2007; Wonders et al., 2008). A comprehensive analysis of expression patterns of several transcription factors in the VZ of the developing mouse GE by Flames et al. revealed that expression of Nkx-6.2 in the dorsal MGE underlies specification of SST-positive interneurons, whereas PV-positive interneurons are derived from Nkx-2.1-expressing progenitors located more ventrally within the MGE, suggesting that anatomically defined subpallial regions can be further divided into subdomains that give rise to functionally distinct interneuron subtypes (Flames et al., 2007) and that lineage plays an important role in generating diverse interneuron populations that are characteristic of the mature neocortex.

In addition to the presence of spatially distinct progenitor domains, a temporal bias in neurogenesis is thought to contribute to interneuron subtype specification. Fate mapping of MGE-derived interneurons showed that these progenitors undergo temporal changes in fate such that they progress from generating mainly SST-expressing neurons to making mainly PV-positive interneurons (Miyoshi et al., 2007). Recent transplantation and lineage-tracing experiments elegantly demonstrated that chandelier cells in the mouse neocortex are selectively born in the MGE at late stages of embryonic development (Inan et al., 2012; Taniguchi et al., 2013).

Although the spatiotemporal dynamics of neurogenesis evidently contribute to diversification of neocortical interneurons, it remains unclear whether interneuron subtype specification occurs at the population or single progenitor level. Using mouse genetics in combination with in utero retroviral labeling, Brown et al. were the first to conduct a clonal analysis of the MGE at the single progenitor level to show that individual RGCs within the MGE are able to generate clones of cortical interneurons that share the same neurochemical markers, as well as clones that contain interneurons expressing different neurochemical markers (Brown et al., 2011). More extensive characterization of interneuron subtypes within clonal clusters using morphological and physiological analysis will help elucidate how many subtypes a single progenitor can generate and in what combinations, as well as the early developmental principles that generate interneuron diversity.

Lineage and spatial distribution

Similar to excitatory neurons, interneurons are distributed throughout the cortex in a laminar fashion. Classic birthdating studies and transplantation experiments have demonstrated that interneurons born at different times in the MGE populate specific layers of the neocortex in an inside-out order (Nery et al., 2002; Valcanis and Tan, 2003). This is also apparent in the case of CGE-derived interneurons that are born relatively late during embryonic neurogenesis and tend to occupy more superficial layers of the cortex in comparison with most MGE-derived interneurons (Miyoshi et al., 2010). Interestingly, cortical interneurons and projection neurons born at roughly the same time tend to occupy the same cortical layer (Valcanis and Tan, 2003). In attempting to understand mechanisms that direct interneurons to position themselves precisely within specific cortical layers, Lodato et al. replaced subcerebral projection neurons with collosal projection neurons and found that this led to abnormal lamination of interneurons. In addition, artificial introduction of corticofugal or callosal projection neurons below the cortex was sufficient to recruit cortical interneurons to these ectopic locations. This study demonstrated that different populations of projection neurons can influence the laminar fate of interneurons (Lodato et al., 2011). Therefore, although the temporal dynamics of neurogenesis correlate with the laminar fate of both projection neurons and interneurons, there may be additional rules that govern their positioning within the neocortex.

Interestingly, Brown et al. showed that neocortical interneurons are produced as spatially organized clonal units in the MGE; in the adult neocortex, these clonally related interneurons are organized into spatially isolated clusters (Brown et al., 2011). Lineage, or clonal relationship, therefore, plays a pivotal role in the production and spatial organization of neocortical interneurons. So how far do lineage/clonal relationships go in establishing functional interneuron microcircuitry? Although some interneurons form and receive non-specific synaptic connections (Fino and Yuste, 2011; Hofer et al., 2011; Packer and Yuste, 2011), several studies have shown that inhibitory interneurons in the neocortex exhibit highly specific synaptic connections within functional circuits (Jiang et al., 2013; Otsuka and Kawaguchi, 2009; Thomson and Lamy, 2007; Yoshimura and Callaway, 2005). Moreover, the synaptic connectivity between local interneurons and excitatory neurons also shows a stereotypic spatial pattern across different regions of the neocortex (Kätzel et al., 2011), suggesting a high degree of specificity in the functional organization of neocortical interneurons. Given the ventral origin and long tangential migration of neocortical interneurons, how stereotypic inhibitory circuits form in the neocortex is an unresolved issue. The spatial organization of clonally related sister inhibitory interneurons raises an intriguing possibility of a lineage-dependent functional organization (electrical- and/or chemical synapse-based) of interneurons that may contribute to specific inhibitory circuits in the mammalian neocortex.

Conclusions

Here, we have reviewed recent findings on how early developmental processes, such as neurogenesis and neuronal migration, instruct circuit assembly for both excitatory and inhibitory neurons in the neocortex. One emerging theme is that, lineage, or the developmental history of a neuron, strongly influences its connectivity. For excitatory neurons, sister neurons derived from the same progenitors preferentially form synaptic connections with each other and process related sensory information. In the case of inhibitory interneurons, lineage appears to play a crucial role in their production and organization. With the recent surge of tools that enable labeling and manipulation of circuit components, we are optimistic that many new insights will be revealed along this line in the near future. For example, does lineage-related circuit assembly only apply to the neocortex, or does it also play a role in circuit formation in other brain regions? How is lineage-related circuitry regulated by experience? How does this basic structural and functional unit evolve from mouse to human? Is it affected in neurological diseases? Answers to these questions would greatly advance our knowledge about the fundamental principles that nature uses to construct functional brain circuits.

Acknowledgments

We apologize to the authors whose work we could not cite owing to space limitations. We thank Ryan Insolera for critical reading of the manuscript and anonymous reviewers for insightful comments that significantly improved the paper.

Footnotes

Funding

Our research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the McKnight Foundation and the March of Dimes Foundation (to S.-H.S). Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Abeles M., Goldstein M. H., Jr (1970). Functional architecture in cat primary auditory cortex: columnar organization and organization according to depth. J. Neurophysiol. 33, 172–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson S. A., Eisenstat D. D., Shi L., Rubenstein J. L. (1997). Interneuron migration from basal forebrain to neocortex: dependence on Dlx genes. Science 278, 474–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson S. A., Kaznowski C. E., Horn C., Rubenstein J. L. R., McConnell S. K. (2002). Distinct origins of neocortical projection neurons and interneurons in vivo. Cereb. Cortex 12, 702–709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang E. S. B. C., Jr, Haydar T. F., Gluncic V., Rakic P. (2003). Four-dimensional migratory coordinates of GABAergic interneurons in the developing mouse cortex. J. Neurosci. 23, 5805–5815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angevine J. B., Jr, Sidman R. L. (1961). Autoradiographic study of cell migration during histogenesis of cerebral cortex in the mouse. Nature 192, 766–768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony T. E., Klein C., Fishell G., Heintz N. (2004). Radial glia serve as neuronal progenitors in all regions of the central nervous system. Neuron 41, 881–890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastos A. M., Usrey W. M., Adams R. A., Mangun G. R., Fries P., Friston K. J. (2012). Canonical microcircuits for predictive coding. Neuron 76, 695–711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock D. D., Lee W. C. A., Kerlin A. M., Andermann M. L., Hood G., Wetzel A. W., Yurgenson S., Soucy E. R., Kim H. S., Reid R. C. (2011). Network anatomy and in vivo physiology of visual cortical neurons. Nature 471, 177–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosking W. H., Zhang Y., Schofield B., Fitzpatrick D. (1997). Orientation selectivity and the arrangement of horizontal connections in tree shrew striate cortex. J. Neurosci. 17, 2112–2127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breunig J. J., Haydar T. F., Rakic P. (2011). Neural stem cells: historical perspective and future prospects. Neuron 70, 614–625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown K. N., Chen S., Han Z., Lu C. H., Tan X., Zhang X. J., Ding L., Lopez-Cruz A., Saur D., Anderson S. A., et al. (2011). Clonal production and organization of inhibitory interneurons in the neocortex. Science 334, 480–486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno R. M., Sakmann B. (2006). Cortex is driven by weak but synchronously active thalamocortical synapses. Science 312, 1622–1627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt S. J. B., Fuccillo M., Nery S., Noctor S., Kriegstein A., Corbin J. G., Fishell G. (2005). The temporal and spatial origins of cortical interneurons predict their physiological subtype. Neuron 48, 591–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cang J., Rentería R. C., Kaneko M., Liu X., Copenhagen D. R., Stryker M. P. (2005). Development of precise maps in visual cortex requires patterned spontaneous activity in the retina. Neuron 48, 797–809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporale N., Dan Y. (2008). Spike timing-dependent plasticity: a Hebbian learning rule. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 31, 25–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardin J. A., Carlén M., Meletis K., Knoblich U., Zhang F., Deisseroth K., Tsai L. H., Moore C. I. (2009). Driving fast-spiking cells induces gamma rhythm and controls sensory responses. Nature 459, 663–667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Leischner U., Rochefort N. L., Nelken I., Konnerth A. (2011). Functional mapping of single spines in cortical neurons in vivo. Nature 475, 501–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Costa N. M., Martin K. A. (2010). Whose cortical column would that be? Front. Neuroanatomy 4, 16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Río J. A., Martínez A., Auladell C., Soriano E. (2000). Developmental history of the subplate and developing white matter in the murine neocortex. Neuronal organization and relationship with the main afferent systems at embryonic and perinatal stages. Cereb. Cortex 10, 784–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai A. R., McConnell S. K. (2000). Progressive restriction in fate potential by neural progenitors during cerebral cortical development. Development 127, 2863–2872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas R. J., Martin K. A. (1991). A functional microcircuit for cat visual cortex. J. Physiol. 440, 735–769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas R. J., Martin K. A. (2004). Neuronal circuits of the neocortex. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 27, 419–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas R. J., Martin K. A. (2007). Mapping the matrix: the ways of neocortex. Neuron 56, 226–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas R. J., Martin K. A., Whitteridge D. (1989). A canonical microcircuit for neocortex. Neural Comput. 1, 480–488 [Google Scholar]

- Fame R. M., MacDonald J. L., Macklis J. D. (2011). Development, specification, and diversity of callosal projection neurons. Trends Neurosci. 34, 41–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fertuzinhos S., Krsnik Z., Kawasawa Y. I., Rasin M. R., Kwan K. Y., Chen J. G., Judas M., Hayashi M., Sestan N. (2009). Selective depletion of molecularly defined cortical interneurons in human holoprosencephaly with severe striatal hypoplasia. Cereb. Cortex 19, 2196–2207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fietz S. A., Kelava I., Vogt J., Wilsch-Bräuninger M., Stenzel D., Fish J. L., Corbeil D., Riehn A., Distler W., Nitsch R., et al. (2010). OSVZ progenitors of human and ferret neocortex are epithelial-like and expand by integrin signaling. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 690–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fino E., Yuste R. (2011). Dense inhibitory connectivity in neocortex. Neuron 69, 1188–1203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishell G., Kriegstein A. R. (2003). Neurons from radial glia: the consequences of asymmetric inheritance. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 13, 34–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flames N., Pla R., Gelman D. M., Rubenstein J. L. R., Puelles L., Marín O. (2007). Delineation of multiple subpallial progenitor domains by the combinatorial expression of transcriptional codes. J. Neurosci. 27, 9682–9695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogarty M., Grist M., Gelman D., Marín O., Pachnis V., Kessaris N. (2007). Spatial genetic patterning of the embryonic neuroepithelium generates GABAergic interneuron diversity in the adult cortex. J. Neurosci. 27, 10935–10946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco S. J., Gil-Sanz C., Martinez-Garay I., Espinosa A., Harkins-Perry S. R., Ramos C., Müller U. (2012). Fate-restricted neural progenitors in the mammalian cerebral cortex. Science 337, 746–749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frantz G. D., McConnell S. K. (1996). Restriction of late cerebral cortical progenitors to an upper-layer fate. Neuron 17, 55–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gal J. S., Morozov Y. M., Ayoub A. E., Chatterjee M., Rakic P., Haydar T. F. (2006). Molecular and morphological heterogeneity of neural precursors in the mouse neocortical proliferative zones. J. Neurosci. 26, 1045–1056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman D. M., Marín O. (2010). Generation of interneuron diversity in the mouse cerebral cortex. Eur. J. Neurosci. 31, 2136–2141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman D. M., Martini F. J., Nóbrega-Pereira S., Pierani A., Kessaris N., Marín O. (2009). The embryonic preoptic area is a novel source of cortical GABAergic interneurons. J. Neurosci. 29, 9380–9389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert C. D., Wiesel T. N. (1983). Clustered intrinsic connections in cat visual cortex. J. Neurosci. 3, 1116–1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert C. D., Wiesel T. N. (1989). Columnar specificity of intrinsic horizontal and corticocortical connections in cat visual cortex. J. Neurosci. 9, 2432–2442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen D. V., Lui J. H., Parker P. R. L., Kriegstein A. R. (2010). Neurogenic radial glia in the outer subventricular zone of human neocortex. Nature 464, 554–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatten M. E. (1999). Central nervous system neuronal migration. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 22, 511–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattox A. M., Nelson S. B. (2007). Layer V neurons in mouse cortex projecting to different targets have distinct physiological properties. J. Neurophysiol. 98, 3330–3340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebb D. O. (1949). The Organization of Behavior. New York: Wiley & Sons; [Google Scholar]

- Hevner R. F., Daza R. A., Englund C., Kohtz J., Fink A. (2004). Postnatal shifts of interneuron position in the neocortex of normal and reeler mice: evidence for inward radial migration. Neuroscience 124, 605–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer S. B., Ko H., Pichler B., Vogelstein J., Ros H., Zeng H., Lein E., Lesica N. A., Mrsic-Flogel T. D. (2011). Differential connectivity and response dynamics of excitatory and inhibitory neurons in visual cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 14, 1045–1052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubel D. H., Wiesel T. N. (1962). Receptive fields, binocular interaction and functional architecture in the cat’s visual cortex. J. Physiol. 160, 106–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubel D. H., Wiesel T. N. (1963). Shape and arrangement of columns in cat’s striate cortex. J. Physiol. 165, 559–568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubel D. H., Wiesel T. N. (1965). Binocular interaction in striate cortex of kittens reared with artificial squint. J. Neurophysiol. 28, 1041–1059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubel D. H., Wiesel T. N. (1974). Uniformity of monkey striate cortex: a parallel relationship between field size, scatter, and magnification factor. J. Comp. Neurol. 158, 295–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubel D. H., Wiesel T. N. (1977). Ferrier lecture. Functional architecture of macaque monkey visual cortex. Proc R. Soc. B 198, 1–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inan M., Welagen J., Anderson S. A. (2012). Spatial and temporal bias in the mitotic origins of somatostatin- and parvalbumin-expressing interneuron subgroups and the chandelier subtype in the medial ganglionic eminence. Cereb. Cortex 22, 820–827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakovcevski I., Mayer N., Zecevic N. (2011). Multiple origins of human neocortical interneurons are supported by distinct expression of transcription factors. Cereb. Cortex 21, 1771–1782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X., Wang G., Lee A. J., Stornetta R. L., Zhu J. J. (2013). The organization of two new cortical interneuronal circuits. Nat. Neurosci. 16, 210–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz L. C., Crowley J. C. (2002). Development of cortical circuits: lessons from ocular dominance columns. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 34–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz L. C., Shatz C. J. (1996). Synaptic activity and the construction of cortical circuits. Science 274, 1133–1138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz L. C., Gilbert C. D., Wiesel T. N. (1989). Local circuits and ocular dominance columns in monkey striate cortex. J. Neurosci. 9, 1389–1399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kätzel D., Zemelman B. V., Buetfering C., Wölfel M., Miesenböck G. (2011). The columnar and laminar organization of inhibitory connections to neocortical excitatory cells. Nat. Neurosci. 14, 100–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelava I., Reillo I., Murayama A. Y., Kalinka A. T., Stenzel D., Tomancak P., Matsuzaki F., Lebrand C., Sasaki E., Schwamborn J. C., et al. (2012). Abundant occurrence of basal radial glia in the subventricular zone of embryonic neocortex of a lissencephalic primate, the common marmoset Callithrix jacchus. Cereb. Cortex 22, 469–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko H., Hofer S. B., Pichler B., Buchanan K. A., Sjöström P. J., Mrsic-Flogel T. D. (2011). Functional specificity of local synaptic connections in neocortical networks. Nature 473, 87–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koulakov A. A., Chklovskii D. B. (2001). Orientation preference patterns in mammalian visual cortex: a wire length minimization approach. Neuron 29, 519–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk T., Pontious A., Englund C., Daza R. A. M., Bedogni F., Hodge R., Attardo A., Bell C., Huttner W. B., Hevner R. F. (2009). Intermediate neuronal progenitors (basal progenitors) produce pyramidal-projection neurons for all layers of cerebral cortex. Cereb. Cortex 19, 2439–2450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriegstein A., Noctor S., Martínez-Cerdeño V. (2006). Patterns of neural stem and progenitor cell division may underlie evolutionary cortical expansion. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7, 883–890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan K. Y., Lam M. M. S., Johnson M. B., Dube U., Shim S., Rasin M. R., Sousa A. M. M., Fertuzinhos S., Chen J. G., Arellano J. I., et al. (2012). Species-dependent posttranscriptional regulation of NOS1 by FMRP in the developing cerebral cortex. Cell 149, 899–911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavdas A. A., Grigoriou M., Pachnis V., Parnavelas J. G. (1999). The medial ganglionic eminence gives rise to a population of early neurons in the developing cerebral cortex. J. Neurosci. 19, 7881–7888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Hjerling-Leffler J., Zagha E., Fishell G., Ruby B. (2010). The largest group of superficial neocortical GABAergic interneurons expresses ionotropic serotonin receptors. J. Neurosci. 30, 16796–16808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. H., Kwan A. C., Zhang S., Phoumthipphavong V., Flannery J. G., Masmanidis S. C., Taniguchi H., Huang Z. J., Zhang F., Boyden E. S., et al. (2012). Activation of specific interneurons improves V1 feature selectivity and visual perception. Nature 488, 379–383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letinic K., Zoncu R., Rakic P. (2002). Origin of GABAergic neurons in the human neocortex. Nature 417, 645–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Lu H., Cheng P. L., Ge S., Xu H., Shi S. H., Dan Y. (2012). Clonally related visual cortical neurons show similar stimulus feature selectivity. Nature 486, 118–121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodato S., Rouaux C., Quast K. B., Jantrachotechatchawan C., Studer M., Hensch T. K., Arlotta P. (2011). Excitatory projection neuron subtypes control the distribution of local inhibitory interneurons in the cerebral cortex. Neuron 69, 763–779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lui J. H., Hansen D. V., Kriegstein A. R. (2011). Development and evolution of the human neocortex. Cell 146, 18–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luskin M. B., Pearlman A. L., Sanes J. R. (1988). Cell lineage in the cerebral cortex of the mouse studied in vivo and in vitro with a recombinant retrovirus. Neuron 1, 635–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malatesta P., Hartfuss E., Götz M. (2000). Isolation of radial glial cells by fluorescent-activated cell sorting reveals a neuronal lineage. Development 127, 5253–5263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malatesta P., Hack M. A., Hartfuss E., Kettenmann H., Klinkert W., Kirchhoff F., Götz M. (2003). Neuronal or glial progeny: regional differences in radial glia fate. Neuron 37, 751–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin O., Anderson S. A., Rubenstein J. L. (2000). Origin and molecular specification of striatal interneurons. J. Neurosci. 20, 6063–6076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín O., Yaron A., Bagri A., Tessier-Lavigne M., Rubenstein J. L. (2001). Sorting of striatal and cortical interneurons regulated by semaphorin-neuropilin interactions. Science 293, 872–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin-Padilla M. (1970). Prenatal and early postnatal ontogenesis of the human motor cortex: a golgi study. I. The sequential development of the cortical layers. Brain Res. 23, 167–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin-Padilla M. (1971). Early prenatal ontogenesis of the cerebral cortex (neocortex) of the cat (Felis domestica). A Golgi study. I. The primordial neocortical organization. Z. Anat. Entwicklungsgesch. 134, 117–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin-Padilla M. (1978). Dual origin of the mammalian neocortex and evolution of the cortical plate. Anat. Embryol. (Berl.) 152, 109–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markram H., Toledo-Rodriguez M., Wang Y., Gupta A., Silberberg G., Wu C. (2004). Interneurons of the neocortical inhibitory system. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 5, 793–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruoka H., Kubota K., Kurokawa R., Tsuruno S., Hosoya T. (2011). Periodic organization of a major subtype of pyramidal neurons in neocortical layer V. Neuroscience 31, 18522–18542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell S. K., Kaznowski C. E. (1991). Cell cycle dependence of laminar determination in developing neocortex. Science 254, 282–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarry L. M., Packer A. M., Fino E., Nikolenko V., Sippy T., Yuste R. (2010). Quantitative classification of somatostatin-positive neocortical interneurons identifies three interneuron subtypes. Front. Neural Circuits 4, 12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire B. A., Gilbert C. D., Rivlin P. K., Wiesel T. N. (1991). Targets of horizontal connections in macaque primary visual cortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 305, 370–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer H. S., Wimmer V. C., Hemberger M., Bruno R. M., de Kock C. P. J., Frick A., Sakmann B., Helmstaedter M. (2010). Cell type-specific thalamic innervation in a column of rat vibrissal cortex. Cereb. Cortex 20, 2287–2303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata T., Kawaguchi A., Okano H., Ogawa M. (2001). Asymmetric inheritance of radial glial fibers by cortical neurons. Neuron 31, 727–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi G., Butt S. J. B., Takebayashi H., Fishell G. (2007). Physiologically distinct temporal cohorts of cortical interneurons arise from telencephalic Olig2-expressing precursors. J. Neurosci. 27, 7786–7798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi G., Hjerling-Leffler J., Karayannis T., Sousa V. H., Butt S. J. B., Battiste J., Johnson J. E., Machold R. P., Fishell G. (2010). Genetic fate mapping reveals that the caudal ganglionic eminence produces a large and diverse population of superficial cortical interneurons. J. Neurosci. 30, 1582–1594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molyneaux B. J., Arlotta P., Menezes J. R. L., Macklis J. D. (2007). Neuronal subtype specification in the cerebral cortex. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8, 427–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mountcastle V. B. (1957). Modality and topographic properties of single neurons of cat’s somatic sensory cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 20, 408–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mountcastle V. B. (1997). The columnar organization of the neocortex. Brain 120, 701–722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mountcastle V. B. (2003). Introduction. Computation in cortical columns. Cereb. Cortex 13, 2–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nery S., Fishell G., Corbin J. G. (2002). The caudal ganglionic eminence is a source of distinct cortical and subcortical cell populations. Nat. Neurosci. 5, 1279–1287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noctor S. C., Flint A. C., Weissman T. A., Dammerman R. S., Kriegstein A. R. (2001). Neurons derived from radial glial cells establish radial units in neocortex. Nature 409, 714–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noctor S. C., Martínez-Cerdeño V., Ivic L., Kriegstein A. R. (2004). Cortical neurons arise in symmetric and asymmetric division zones and migrate through specific phases. Nat. Neurosci. 7, 136–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberlaender M., de Kock C. P. J., Bruno R. M., Ramirez A., Meyer H. S., Dercksen V. J., Helmstaedter M., Sakmann B. (2012). Cell type-specific three-dimensional structure of thalamocortical circuits in a column of rat vibrissal cortex. Cereb. Cortex 22, 2375–2391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohki K., Reid R. C. (2007). Specificity and randomness in the visual cortex. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 17, 401–407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohki K., Chung S., Ch’ng Y. H., Kara P., Reid R. C. (2005). Functional imaging with cellular resolution reveals precise micro-architecture in visual cortex. Nature 433, 597–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsuki G., Nishiyama M., Yoshida T., Murakami T., Histed M., Lois C., Ohki K. (2012). Similarity of visual selectivity among clonally related neurons in visual cortex. Neuron 75, 65–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka T., Kawaguchi Y. (2009). Cortical inhibitory cell types differentially form intralaminar and interlaminar subnetworks with excitatory neurons. J. Neurosci. 29, 10533–10540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packer A. M., Yuste R. (2011). Dense, unspecific connectivity of neocortical parvalbumin-positive interneurons: a canonical microcircuit for inhibition? J. Neurosci. 31, 13260–13271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petanjek Z., Berger B., Esclapez M. (2009). Origins of cortical GABAergic neurons in the cynomolgus monkey. Cereb. Cortex 19, 249–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A., Kara D. A. (1987). The neuronal composition of area 17 of rat visual cortex. IV. The organization of pyramidal cells. J. Comp. Neurol. 260, 573–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A., Sethares C. (1996). Myelinated axons and the pyramidal cell modules in monkey primary visual cortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 365, 232–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A., Walsh T. M. (1972). A study of the organization of apical dendrites in the somatic sensory cortex of the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 144, 253–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A., Cifuentes J. M., Sethares C. (1997). The organization of pyramidal cells in area 18 of the rhesus monkey. Cereb. Cortex 7, 405–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polleux F., Whitford K. L., Dijkhuizen P. A., Vitalis T., Ghosh A. (2002). Control of cortical interneuron migration by neurotrophins and PI3-kinase signaling. Development 129, 3147–3160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouille F., Marin-Burgin A., Adesnik H., Atallah B. V., Scanziani M. (2009). Input normalization by global feedforward inhibition expands cortical dynamic range. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 1577–1585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell T. P., Mountcastle V. B. (1959). Some aspects of the functional organization of the cortex of the postcentral gyrus of the monkey: a correlation of findings obtained in a single unit analysis with cytoarchitecture. Bull. Johns Hopkins Hosp. 105, 133–162 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price J., Thurlow L. (1988). Cell lineage in the rat cerebral cortex: a study using retroviral-mediated gene transfer. Development 104, 473–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P. (1971). Guidance of neurons migrating to the fetal monkey neocortex. Brain Res. 33, 471–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P. (1972). Mode of cell migration to the superficial layers of fetal monkey neocortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 145, 61–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P. (1988). Specification of cerebral cortical areas. Science 241, 170–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockland K. S., Ichinohe N. (2004). Some thoughts on cortical minicolumns. Exp. Brain Res. 158, 265–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothschild G., Nelken I., Mizrahi A. (2010). Functional organization and population dynamics in the mouse primary auditory cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 353–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T. R., Gray N. W., Mainen Z. F., Svoboda K. (2007). The functional microarchitecture of the mouse barrel cortex. PLoS Biol. 5, e189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Q., Wang Y., Dimos J. T., Fasano C. A., Phoenix T. N., Lemischka I. R., Ivanova N. B., Stifani S., Morrisey E. E., Temple S. (2006). The timing of cortical neurogenesis is encoded within lineages of individual progenitor cells. Nat. Neurosci. 9, 743–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shitamukai A., Konno D., Matsuzaki F. (2011). Oblique radial glial divisions in the developing mouse neocortex induce self-renewing progenitors outside the germinal zone that resemble primate outer subventricular zone progenitors. J. Neurosci. 31, 3683–3695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohal V. S., Zhang F., Yizhar O., Deisseroth K. (2009). Parvalbumin neurons and gamma rhythms enhance cortical circuit performance. Nature 459, 698–702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan K., Leone D. P., Bateson R. K., Dobreva G., Kohwi Y., Kohwi-Shigematsu T., Grosschedl R., McConnell S. K. (2012). A network of genetic repression and derepression specifies projection fates in the developing neocortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 19071–19078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stancik E. K., Navarro-Quiroga I., Sellke R., Haydar T. F. (2010). Heterogeneity in ventricular zone neural precursors contributes to neuronal fate diversity in the postnatal neocortex. J. Neurosci. 30, 7028–7036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussel L., Marin O., Kimura S., Rubenstein J. L. (1999). Loss of Nkx2.1 homeobox gene function results in a ventral to dorsal molecular respecification within the basal telencephalon: evidence for a transformation of the pallidum into the striatum. Development 126, 3359–3370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabadics J., Varga C., Molnár G., Oláh S., Barzó P., Tamás G. (2006). Excitatory effect of GABAergic axo-axonic cells in cortical microcircuits. Science 311, 233–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan S. S., Kalloniatis M., Sturm K., Tam P. P., Reese B. E., Faulkner-Jones B. (1998). Separate progenitors for radial and tangential cell dispersion during development of the cerebral neocortex. Neuron 21, 295–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka D., Nakaya Y., Yanagawa Y., Obata K., Murakami F. (2003). Multimodal tangential migration of neocortical GABAergic neurons independent of GPI-anchored proteins. Development 130, 5803–5813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi H., Lu J., Huang Z. J. (2013). The spatial and temporal origin of chandelier cells in mouse neocortex. Science 339, 70–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson A. M., Lamy C. (2007). Functional maps of neocortical local circuitry. Front. Neurosci. 1, 19–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson A. M., West D. C., Wang Y., Bannister A. P. (2002). Synaptic connections and small circuits involving excitatory and inhibitory neurons in layers 2-5 of adult rat and cat neocortex: triple intracellular recordings and biocytin labelling in vitro. Cereb. Cortex 12, 936–953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ts’o D. Y., Gilbert C. D., Wiesel T. N. (1986). Relationships between horizontal interactions and functional architecture in cat striate cortex as revealed by cross-correlation analysis. J. Neurosci. 6, 1160–1170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valcanis H., Tan S. S. (2003). Layer specification of transplanted interneurons in developing mouse neocortex. J. Neurosci. 23, 5113–5122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh C., Cepko C. L. (1988). Clonally related cortical cells show several migration patterns. Science 241, 1342–1345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Tsai J. W., LaMonica B., Kriegstein A. R. (2011). A new subtype of progenitor cell in the mouse embryonic neocortex. Nat. Neurosci. 14, 555–561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichterle H., Garcia-Verdugo J. M., Herrera D. G., Alvarez-Buylla A. (1999). Young neurons from medial ganglionic eminence disperse in adult and embryonic brain. Nat. Neurosci. 2, 461–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichterle H., Turnbull D. H., Nery S., Fishell G., Alvarez-Buylla A. (2001). In utero fate mapping reveals distinct migratory pathways and fates of neurons born in the mammalian basal forebrain. Development 128, 3759–3771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesel T. N., Hubel D. H. (1963). Single-cell responses in striate cortex of kittens deprived of vision in one eye. J. Neurophysiol. 26, 1003–1017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson N. R., Runyan C. A., Wang F. L., Sur M. (2012). Division and subtraction by distinct cortical inhibitory networks in vivo. Nature 488, 343–348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimmer V. C., Bruno R. M., de Kock C. P. J., Kuner T., Sakmann B. (2010). Dimensions of a projection column and architecture of VPM and POm axons in rat vibrissal cortex. Cereb. Cortex 20, 2265–2276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonders C. P., Taylor L., Welagen J., Mbata I. C., Xiang J. Z., Anderson S. A. (2008). A spatial bias for the origins of interneuron subgroups within the medial ganglionic eminence. Dev. Biol. 314, 127–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q., Cobos I., De La Cruz E., Rubenstein J. L., Anderson S. A. (2004). Origins of cortical interneuron subtypes. J. Neurosci. 24, 2612–2622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Roby K. D., Callaway E. M. (2006). Mouse cortical inhibitory neuron type that coexpresses somatostatin and calretinin. J. Comp. Neurol. 499, 144–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q., Tam M., Anderson S. A. (2008). Fate mapping Nkx2.1-lineage cells in the mouse telencephalon. J. Comp. Neurol. 506, 16–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura Y., Callaway E. M. (2005). Fine-scale specificity of cortical networks depends on inhibitory cell type and connectivity. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 1552–1559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y. C., Bultje R. S., Wang X., Shi S. H. (2009). Specific synapses develop preferentially among sister excitatory neurons in the neocortex. Nature 458, 501–504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y. C., He S., Chen S., Fu Y., Brown K. N., Yao X. H., Ma J., Gao K. P., Sosinsky G. E., Huang K., et al. (2012). Preferential electrical coupling regulates neocortical lineage-dependent microcircuit assembly. Nature 486, 113–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]