Abstract

Propargylic esters and phosphates are easily accessible substrates, which exhibit rich and tunable reactivities in the presence of transition metal catalysts. π-acidic metals, mostly gold and platinum salts, activate these substrates for an initial 1,2- or 1,3-acyloxy and phosphatyloxy migration processes to form reactive intermediates. These intermediates are able to undergo further cascade reactions leading to a variety of diverse structures. This tutorial review systematically introduces the double migratory reactions of propargylic esters and phosphates as a novel synthetic method, in which further cascade reaction of the reactive intermediate is accompanied by a second migration of a different group, thus offering a rapid route to a wide range of functionalized products. The serendipitous observations, as well as designed approaches involving the double migratory cascade reactions, will be discussed with emphasis placed on the mechanistic aspects and the synthetic utilities of the obtained products.

1. Introduction

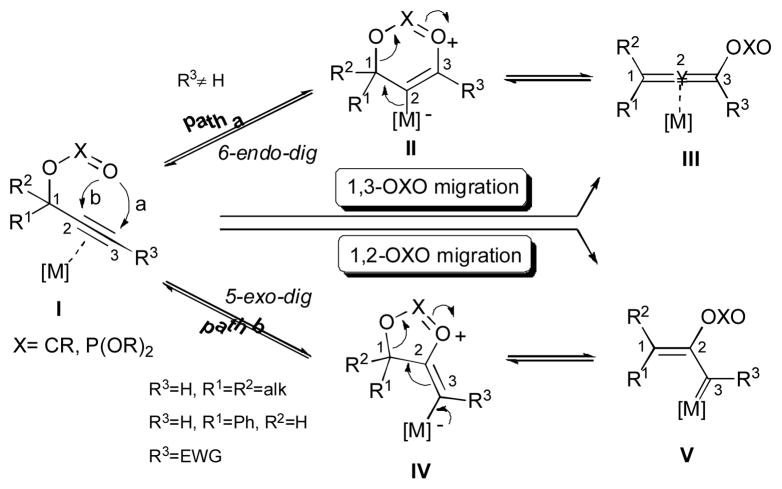

Cascade transformations offer enhancement of molecular complexity and diversity from simpler molecules, which are often accompanied by high degrees of chemo-, regio-, diastereo-, and enantioselectivity.1–3 Compared to the stepwise reactions, these step-economical processes represent environmentally and economically more favored approaches. One of the remarkable examples of such transformations is a transition metal-catalyzed molecular rearrangement of readily available propargylic esters and phosphates.4–6 Earlier cases include copper-,7 silver-,7 zinc-,8 and palladium-9 catalyzed reactions. However, extensive studies were triggered by discovery of ruthenium-,10 platinum-,11 and gold-12 catalyzed processes. It is generally accepted that metal catalysts, especially π-acidic gold salts, can activate the triple bond of I for further transformations (Scheme 1). Thus, it can undergo a 6-endo-dig cyclization to produce intermediate II, which further rearranges into allene III (path a, Scheme 1). Overall, this formal [3,3]-rearrangement represents a 1,3-OXO (X=CR, P(OR)2) migration process. Alternatively, an activated substrate I can undergo a 5-exo-dig cyclization to form intermediate IV, which upon ring opening forms the metal-stabilized carbene V (path b, Scheme 1). This process, which involves a 1,2-OXO migration, is often referred as a Rautenstrauch rearrangement.9

Scheme 1.

Competitive 1,2- or 1,3-migration of propargylic esters and phosphates

Generally, the regiochemistry of I for 1,3-OXO migration to form III (Scheme 1, path a) or 1,2-OXO migration to generate V (Scheme 1, path b) can be predicted. As a rule of thumb, if substrates I possess electronically unbiased internal alkynes (R3≠H), the 1,3-OXO migration takes place.13 Alternatively, for tertiary or benzyl alcohol derived substrate I, possessing terminal alkynes (R3=H)14 and electronically biased internal alkynes (R3=EWG),15,16 the 1,2-OXO migration is preferred. However, other factors, such as the choice of metal catalyst,17 substitution pattern at propargyl moiety,18 and temperature,19 in some cases have been reported to govern the regiochemical outcome of these reactions.

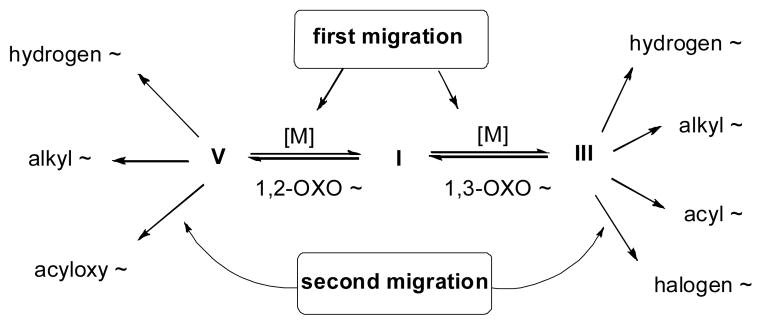

Interestingly, reactive compounds III and V, which posses additional functional groups, can undergo further cascade transformations, including intra-20 or intermolecular21 trapping, cycloaddtion,22 cross-coupling,23 and oxidation reactions.24 Alternatively, if these intermediates possess appropriately situated migrating groups, such as hydrogen, halogen, or alkyl-, acyl-, and acyloxy groups, then a second migration can occur, thus offering an easy route to diverse functionalized products (Scheme 2). The double migratory cascade approach allows for a rapid building of molecular complexity including synthetically useful cyclic, acyclic and polycyclic structures.

Scheme 2.

Double migratory cascade reactions of propargylic esters and phosphates.

This tutorial review focuses on gold-, copper-, and platinum-catalyzed cascade reactions of propargylic esters and phosphates, in which two migration processes of different groups take place. First, the double migratory transformations that are initiated with a 1,3-OXO migration are discussed (Scheme 2, right). The cascade reactions involving an initial 1,2-OXO migration (Scheme 2, left) are covered in the second part. Throughout the text, major concepts, synthetic applications and mechanisms of the given transformations are highlighted.

2. Double migratory transformations with an initial 1,3-OXO migration

2.1 Cascade 1,3-OXO/hydride migration

2.1.1 Double 1,3-OXO/1,2-H migration

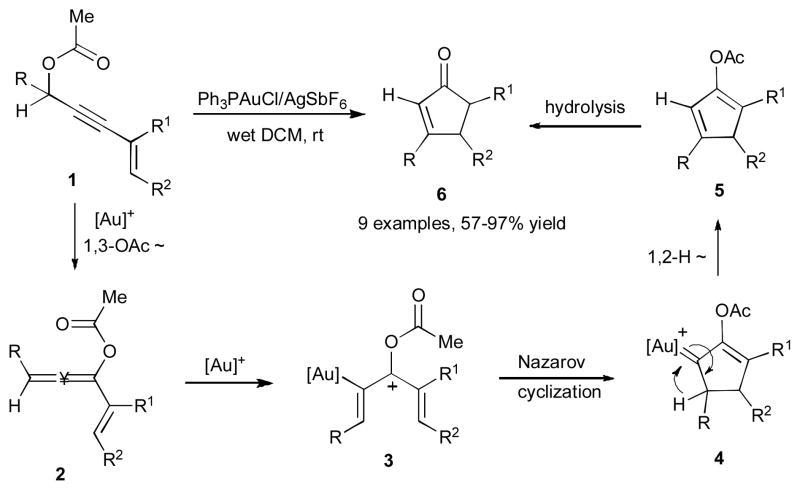

In 2006, Zhang and co-workers reported the Au(I)-catalyzed cascade reaction of propargylic esters 1 into the cyclopentenone 6 (Scheme 3).25 This reaction proceeds well with various cyclic and acyclic substrates providing cyclopentanone products in good to excellent yields. The proposed mechanism involves an initial 1,3-acyloxy migration to form allenylacetate 2 (vide supra), which in the presence of the gold catalyst transforms into the vinyl gold species 3. The Nazarov cyclization of the latter produces cyclic gold-stabilized carbene 4, which upon a subsequent 1,2-hydride shift affords dienyl acetate 5. Hydrolysis of 5 by wet dichloromethane furnishes the cyclopentenone 6.

Scheme 3.

Gold-catalyzed 1,3-OAC/1,2-H migration cascade towards cyclopentenone.25

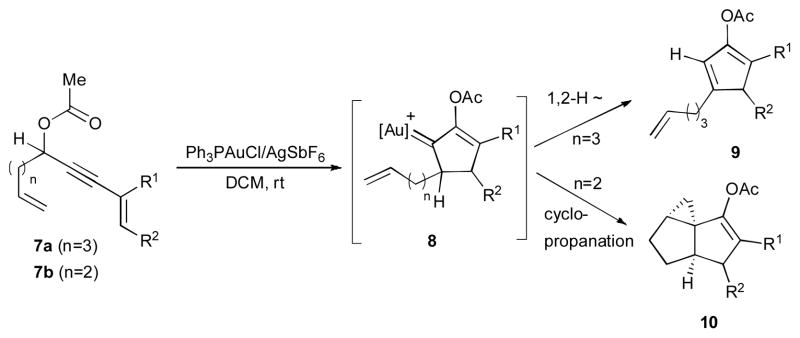

Festerbank and Malacria disclosed an analogous Au(I)-catalyzed reaction of analogous enynyl acetates 7 bearing a tethered olefin at the propargylic position (Scheme 4).26 It is believed that after the 1,3-OAc migration/Nazarov cyclization sequence, the compound 8 (an analogue of 4) is formed. Depending on the length of the tether, different reactivity of the gold-carbene 8 was observed. When n=3 (7a), the discussed above 1,2-hydride shift25 takes place to produce the cyclopentadienyl acetate 9. However, in the reaction of substrate with a shorter tether (7b, n=2), an exclusive formation of tricyclic compound 10 via an electrophilic cyclopropanation reaction was observed. DFT calculations supported the cyclopropanation reaction for compound 8b into 10, which is both kinetically and thermodynamically favored over the 1,2-hydride shift that leads to 9.

Scheme 4.

Competitive 1,2-H shift versus cyclopropanation.26

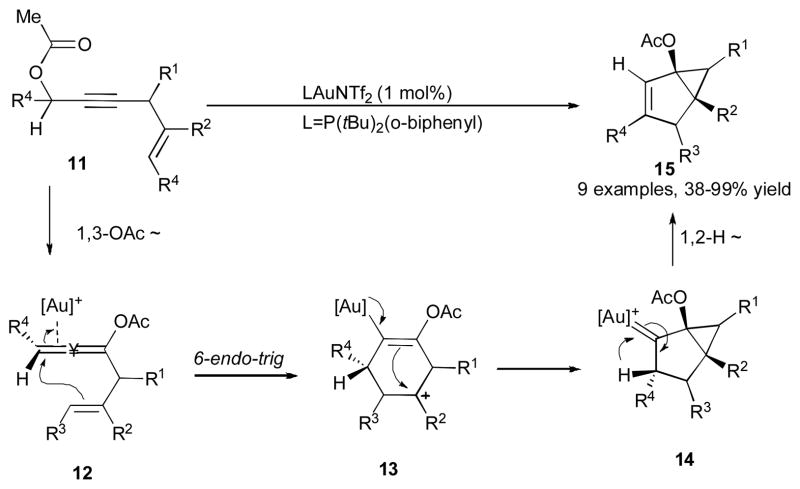

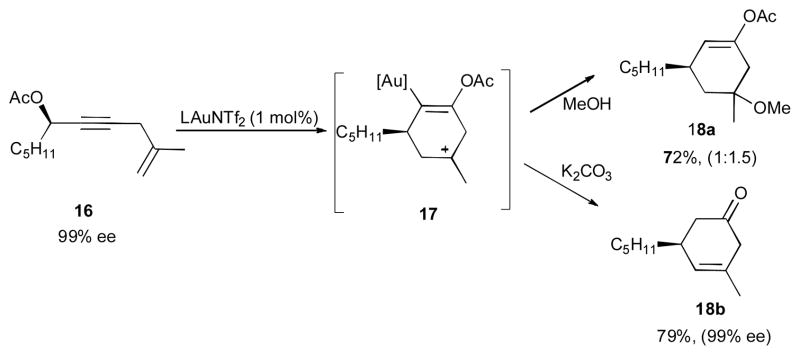

Gagosz and co-workers have demonstrated an efficient Au(I)-catalyzed synthesis of bicylic framework 15 from 5-yn-1-yl acetate 11 (Scheme 5).27 The products with a variety of different substituents at R1, R2, R3 and R4 positions were formed in high yields under mild reaction conditions. Treatment of propargylic acetate 11 with the gold catalyst initiates the 1,3-acyloxy migration to form the allene 12, which further undergoes a nucleophilic attack of the alkene moiety at the metal-activated allene via a 6-endo-trig cyclization to generate carbocation 13. A subsequent intramolecular attack of the vinyl gold moiety of the latter at the cationic center produces a cyclopropyl-containing gold-stabilized carbene 14, which upon the 1,2-hydride shift furnishes the final bicyclic product 15. Interestingly, the intermediacy of cation 17 was further confirmed in the reaction of enantioriched substrate 16 by trapping it with methanol to give the methoxylated product 18a as a 1:1.5 ratio of diastereomers (Scheme 6). Moreover, in the presence of a base and methanol, the produced cation 17 underwent a deprotonation/hydrolysis sequence to produce cyclohexenone 18b. In both cases, complete preservation of chirality was observed.

Scheme 5.

Gold-catalyzed 1,3-OAC/1,2-H migration cascade for the synthesis of bicyclo[3.1.0]hexenes.27

Scheme 6.

Further reactions of propargylic acetates.27

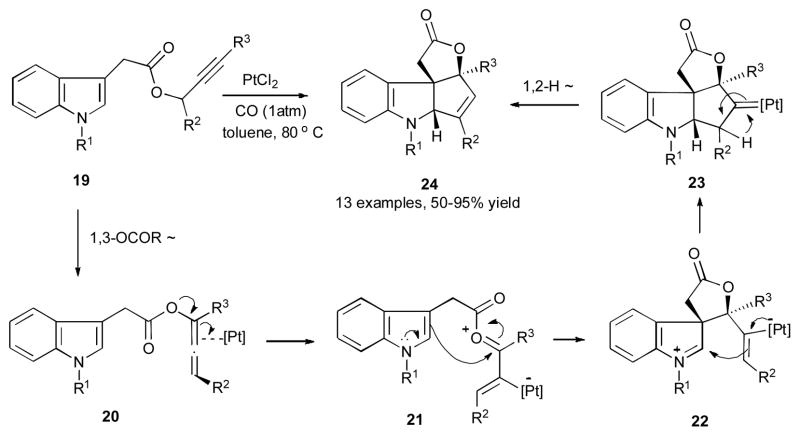

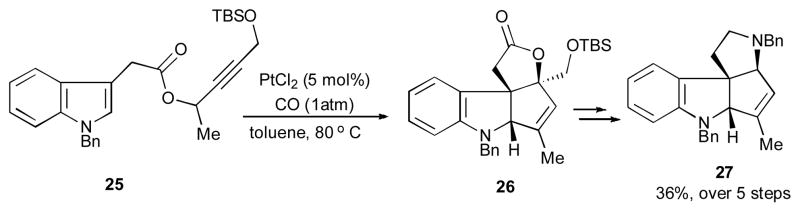

In 2007, Zhang’s group developed the Pt(II)-catalyzed synthesis of tetracyclic 2,3-indoline-fused cyclopentenes 24 from the propargylic 3-indoleacetates 19 (Scheme 7).28 This reaction exhibited a wide substrate scope, as various groups at propargylic position, nitrogen atom, and terminus alkyne of 19 were well-tolerated under the reaction conditions. According to the mechanistic hypothesis, the 1,3-migration of indoleacetate group produces allene 20, which then in the presence of platinum catalyst gives the oxocarbenium species 21. Following the C3 attack of the indole moiety at the electrophilic center of the latter, the vinyl platinum 22 is formed. A subsequent 5-exo-trig cyclization of 22 produces the platinum carbene-containing tetracyclic compound 23, which undergoes a 1,2-hydride shift to furnish the final tetracyclic product 24. Notably, a synthetic utility of this transformation was demonstrated by a short synthesis of compound 27, a tetracyclic core of vindolinine (Scheme 8). Thus, propargylic ester 25 under these reaction conditions produced compound 26, which upon sequential functional group interconversion was efficiently transformed into the indoline-containing alkaloid 27 in a reasonable overall yield.

Scheme 7.

Platinum-catalyzed 1,3-OCOR/1,2-H migration cascade towards tetracyclic 2,3-indoline-fused cyclopentenes.28

Scheme 8.

Toward the synthesis of the tetracyclic core of vindolinine.28

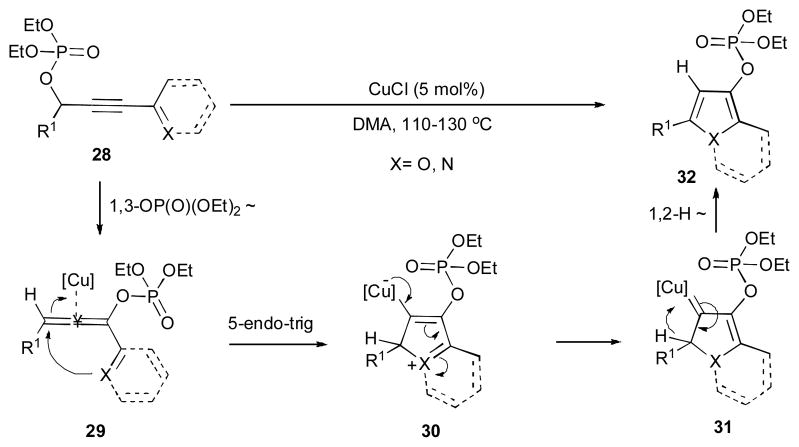

Gevorgyan’s group demonstrated the copper-catalyzed synthesis of various heterocycles 32 from propargylic phosphates 28 (Scheme 9).29 A variety of substituted furanes and indolizines could be efficiently accessed via this cascade transformation. The proposed mechanism involves the Cu-catalyzed 1,3-phosphatyloxy migration to produce allene 29, which upon a nucleophilic attack of the heteroatom at the metal-activated allene via a 5-endo-trig process generates 30. The latter then converts into the heterocyclic copper carbene 31, which further undergoes a subsequent 1,2-hydride shift to furnish heterocycle 32. Employment of analogous acyloxy-containing substrate in this reaction was less efficient.

Scheme 9.

Copper-catalyzed 1,3-OP(O)(OEt)2/1,2-H migration cascade towards heterocycles.29

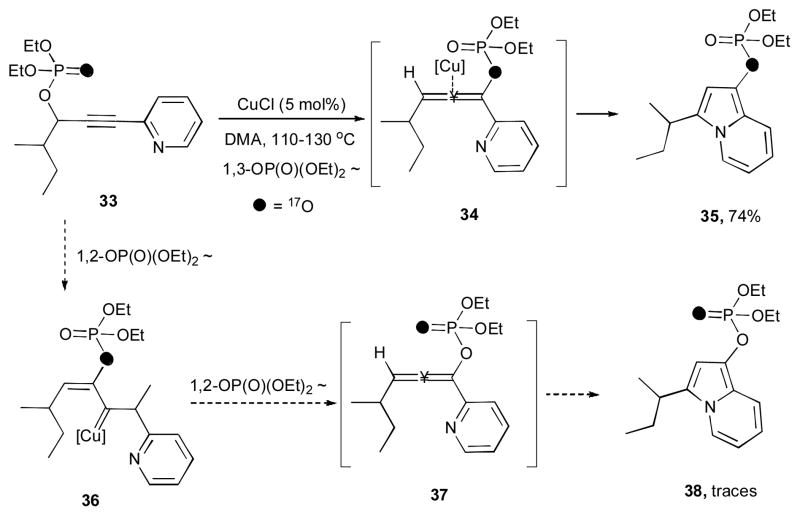

To better undrestand the mechanism of the reaction, the [17O]-enriched alkynyl pyridine 33 was treated under the reaction conditions (Scheme 10). Subsequently, the corresponding indolizine 35 with the labeled bridging phosphate oxygen was isolated as a major isotopomer with traces of 38 observed. Thus, this observation strongly supports that migratory cycloisomerization of substrate 33 involves the formation of allene 34 (the result of a 1,3-phosphatyloxy migration) rather than isotopomeric allene 37 (the product of two sequential 1,2-phosphathyloxy migrations).30

Scheme 10.

Cycloisomerization of a labeled phosphatyloxy alkynyl pyridine.29

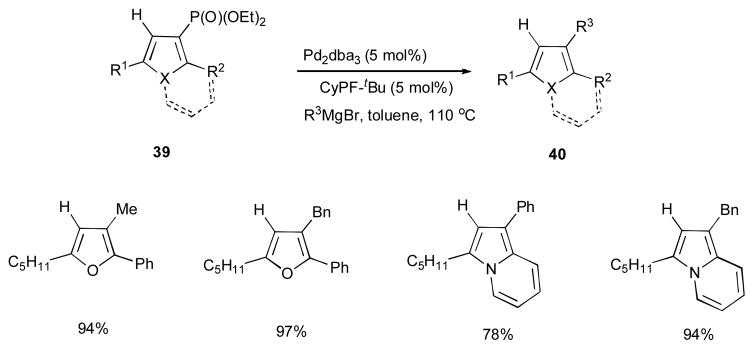

The synthetic utility of the obtained phosphatyloxy-containing heterocycles 39 in this cascade reaction was demonstrated by an efficient Kumada cross-coupling reaction to produce a variety of substituted furans and indolizines 40 (Scheme 11).

Scheme 11.

Kumada cross-coupling of obtained phosphatyloxy-containing hetrocycles.29

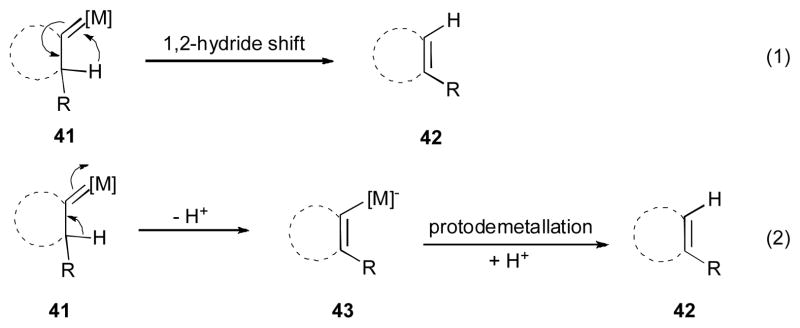

It is worth mentioning that the second migration process in the above-discussed methods (i.e. formation of 42 form metal carbene 41) has been proposed to occur via a 1,2-hydride shift, which is well-established for related processes (Equation 1, Scheme 12).31 However, in the discussed above double migratory cascade reactions this route has not been proven yet. Alternatively, the pathway including a deprotonation of 41 to form 43 followed by a protiodemetallation step may account for the formation of 42 (Equation 2, Scheme 12).25

Scheme 12.

Alternative pathways for 1,2 hydrogen shifts to metal carbenes.

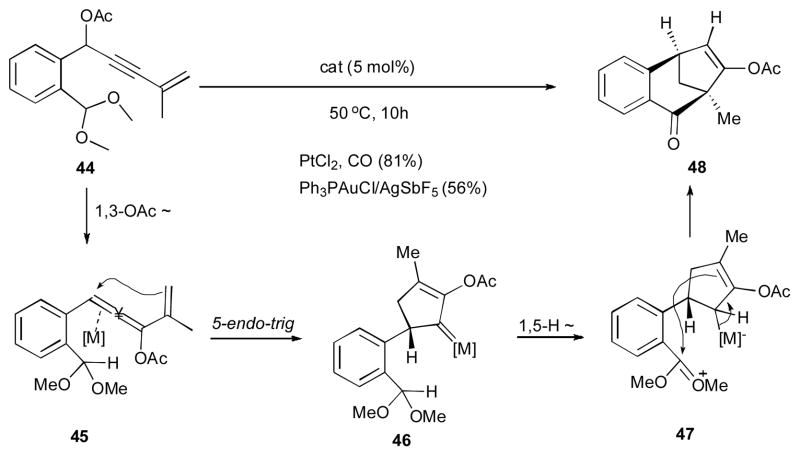

2.1.2 Double 1,3-OXO/1,5-H migration

It was shown by Liu’s group that propargylic acetate 44 could be converted into the tricyclic structure 48 in the presence of either gold(I) or platinum(II) catalysts (Scheme 13).32 The mechanism of this reaction involves the metal-triggered 1,3-OAc migration to produce allene 45, which upon a 5-endo-trig cyclization generates the bicycilc metal carbene 46. A followed 1,5-hydride shift from acetal moiety of the latter to the electrophilic metal carbene center produces 47, which then undergoes a nucleophilic attack of the allyl metal moiety at the electrophilic oxocarbenium center to furnish the final tricyclic product 48.

Scheme 13.

Metal-catalyzed 1,3-OAc/1,5-H migration cascade for the synthesis of polycyclic compounds.32

2.2 Cascade 1,3-OXO/alkyl migration

2.2.1 Double 1,3-OXO/1,2-alkyl migration

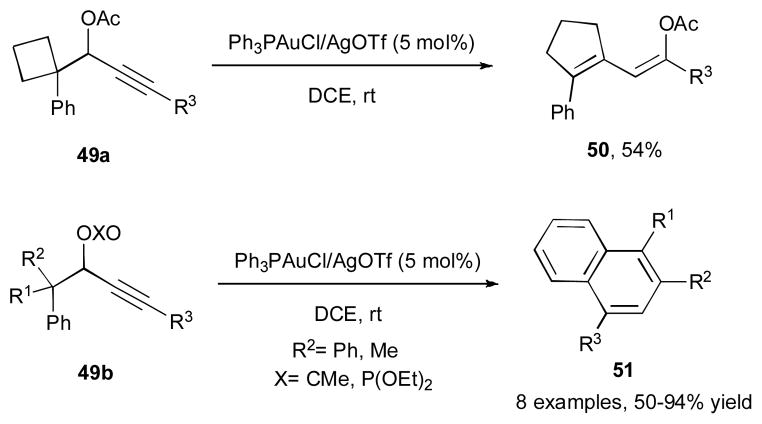

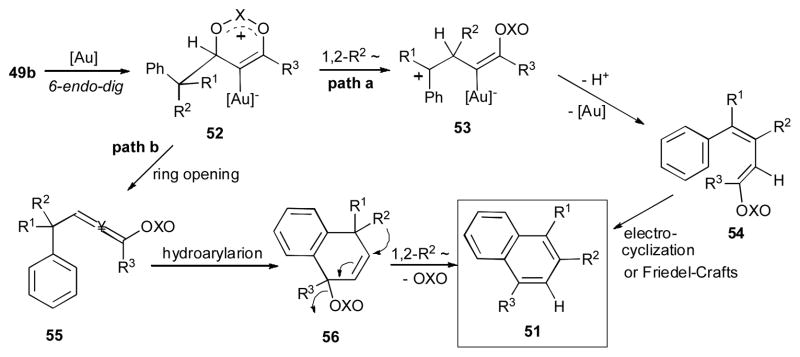

Gevorgyan and co-workers reported the gold-catalyzed cascade reaction of the propargylic esters and phosphates 49a and 49b (Scheme 14).33,34 The substrate 49a, which possesses a strained cyclobutyl ring at the α-position of the propargylic ester,35 underwent the gold- catalyzed 1,3-OAc migration/ring expansion sequence to produce 1,3-diene 50. Interestingly, incorporation in the structure of propargylic esters or phosphates 49b other migrating groups, such as phenyl and methyl, led to unsymmetrically substituted naphthalenes 51. It was proposed that substrate 49b initially undergoes the gold-catalyzed 6-endo-dig cyclization to produce the cyclic intermediate 52 (Scheme 15). According to the path a, a 1,2-R2 migration in the latter takes place to form the benzylic carbocation 53, which upon a proton loss/protiodeauration sequence gives the diene 54. A subsequent cyclization of 54 via either 6π-electrocyclization or Friedel-Crafts reactions furnishes the naphthalene product 51. Alternatively, ring opening of 52 gives the allene 55, which upon hydroarylation affords 1,4-dihydronaphthalene 56 (path b). The following 1,2-R2 migration in the latter produces the naphthalene product 51.

Scheme 14.

Gold-catalyzed 1,3-OXO/1,2-alkyl migration cascade towards dienes and naphthalenes.33,34

Scheme 15.

Proposed mechanism for the gold-catalyzed 1,3-OXO/1,2-alkyl migration cascade. 33,34

2.2.2 Double 1,3-OXO/1,3-alkyl migration

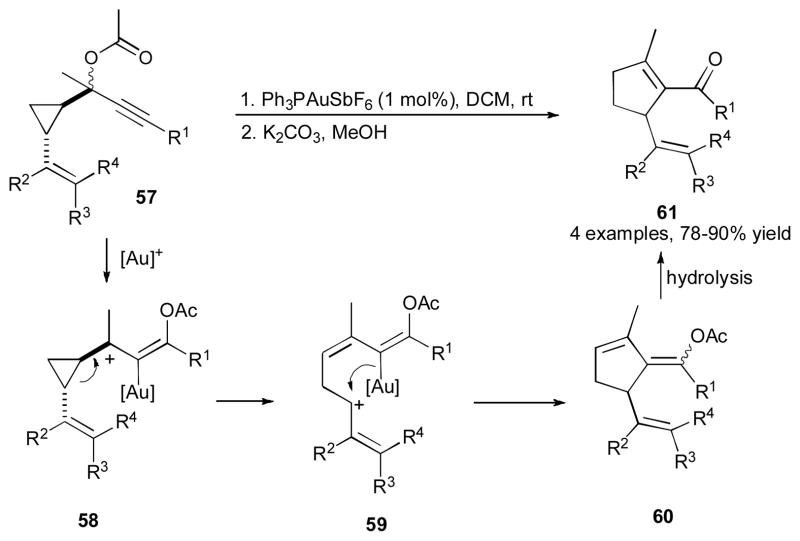

In 2008, Wang, Nevado, and Goeke reported the gold-catalyzed cascade reaction of propargylic ester 57 into cyclopentenylketone 61 (Scheme 16).36 Based on the proposed mechanism, the cyclopropyl-containg substrate 57 undergoes a 1,3-OAc migration to produce the carbenium ion 58, which upon ring opening of cyclopropane moiety generates the allylic cation 59. Nucleophilic attack of the vinyl gold moiety in the latter at the cationic center leads to exocylic vinyl acetate 60, which upon hydrolysis/double bond isomerization sequence affords the corresponding cyclopentenylketone 61.37

Scheme 16.

Gold-catalyzed 1,3-OAc migration/ring expansion cascade.36

In an independent study, Toste’s group provided more mechanistic details on the reversibility of the 1,3-pivaloxy migration process in an analogous reaction of stereochemically defined propargylic pivalate 62 (Scheme 17).38 In the presence of the gold(I)-catalyst, the substrate 62 undergoes a 6-endo-dig cyclization to produce cyclic intermediate 63. Following the ring opening of the latter, the metal-activated allene 64 is formed, which upon cis-trans isomerization produces the thermodynamically more stable trans-cyclopropane 65, although the detailed mechanism of this step remains unclear.38 The following concerted ring expansion of 64 or 65 affords the pentannulated product 66.

Scheme 17.

Further insight into the mechanism of gold-catalyzed 1,3-OAc migration/ring expansion cascade.38

In 2011, Toste and co-workers disclosed the gold-catalyzed enantioselective synthesis of chromenyl derivatives 71 from the propargylic pivalates 67 (Scheme 18).39 Among all chiral ligands tested the acyclic 3,3′-functionalized BINAM ligand A showed the best enantioselectivity. The mechanism of the reaction involves an initial 1,3-pivaloxy migration to yield the metal-activated axially chiral allene 68, which in the presence of the gold catalyst transforms into the achiral carbocation 69. The latter, which is stabilized by the oxygen atom of the migrated group, possesses a chiral ligand at the gold moiety. Therefore, the dynamic kinetic asymmetric 6-endo-trig cyclization leads to the enantioenriched oxonium compound 70. Further carbodemetallation of the vinyl gold moiety in latter via the 1,3-alkyl migration affords the C3-substituted chromenyl pivalate 71. Interestingly, it was shown that in the presence of LiAlH4, the vinyl pivalate moiety of 71 could be further converted to the corresponding ketone to give access to enantioenriched chromanones.

Scheme 18.

Gold-catalyzed enantioselective 1,3-OPiv/1,3-alkyl migration cascade.39

2.3. Cascade 1,3-OXO/acyl migration

2.3.1. Double 1,3-OXO/1,3-acyl migration

Zhang’s group reported the gold(III)-catalyzed cascade reaction of propargylic esters 72 into α-ylidene-β-diketones 76 and 77 (Scheme 19).40 Substrate 72, possesing different substituents at the terminal alkyne and the propargylic positions, reacted in a highly efficient manner. Notably, not only propargylic pivalates, but also acrylates, benzoates, and carbonate were employed in this double migratory process. According to the mechanistic hypothesis, the propargylic ester 72 undergoes a 1,3-OCOR migration to form the allenylcarboxylate 73, which in the presence of the gold catalyst transforms into a vinyl gold species 74. Intramolecular nucleophilic attack of the vinyl gold moiety at the acylium ion in the later produces a four-membered oxacycle 75, which upon rearrangement affords the (E)-α-ylidene-β-diketone 76. The Z diastereomer 77 is believed to form via isomerization of the E analogue in the presence of Au(III) catalyst.

Scheme 19.

Gold-catalyzed 1,3-OCOR/1,3-acyl migration cascade.40

2.3.2 Double 1,3-OXO/1,5-acyl migration

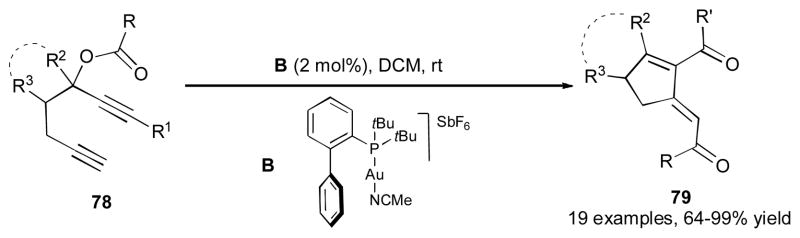

It was shown by Malacria, Gandon, and Fensterbank that δ-diketones 79 can be formed via the gold-catalyzed double migratory cascade reaction of hepta-1,6-diyn-3-yl esters 78 (Scheme 20).41 A number of cyclic and acyclic 1,6-diynes 78 possessing different substituents at R1, R2 and R3 positions reacted well under these mild reaction conditions.

Scheme 20.

Gold-catalyzed 1,3-OAc/1,5-acyl migration cascade.41

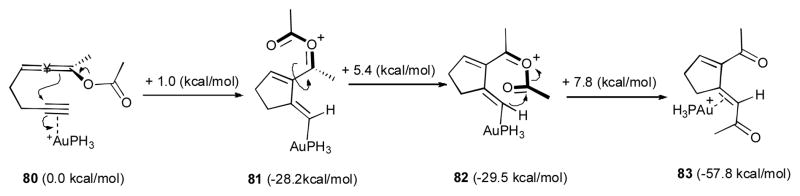

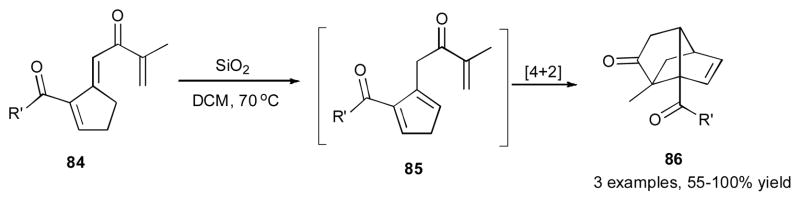

The proposed mechanism of this reaction was validated by DFT computations, where the simplified AuPH3 was used as the catalyst (Scheme 21). After an initial 1,3-OCOR migration in 78, the allene 80 is produced, which further undergoes a low-barrier 5-exo-dig cyclization to generate vinyl gold species 81. Rotation of the acyloxy group in the latter needs 5.4 kcal/mol to form the correct rotamer 82, which provides suitable orbital overlap for the further reaction. The following exothermic 1,5-acyl migration takes place via a nucleophilic attack of the vinyl gold of 82 at the acyl moiety to furnish the E product 83. The triene 84 obtained via this chemistry, in the presence of silica, underwent an interesting transformation into a complex tricyclic compound 86, presumably via initial double bond isomerization to 85, followed by its intramolecular [4+2] cycloaddition (Scheme 22).

Scheme 21.

Mechanism of gold-catalyzed 1,3-OAc/1,5-acyl migration cascade supported by DFT calculations.41

Scheme 22.

Intramolecular [4+2] cycloaddition of obtained dienes.41

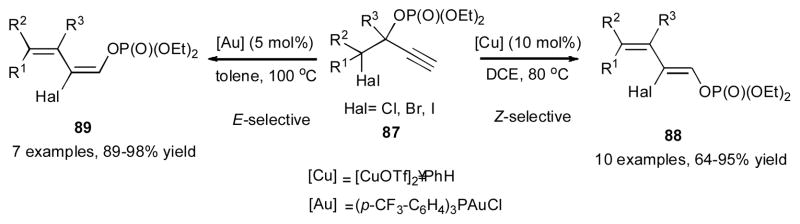

2.4 Cascade 1,3-OXO/1,3-halogen migration

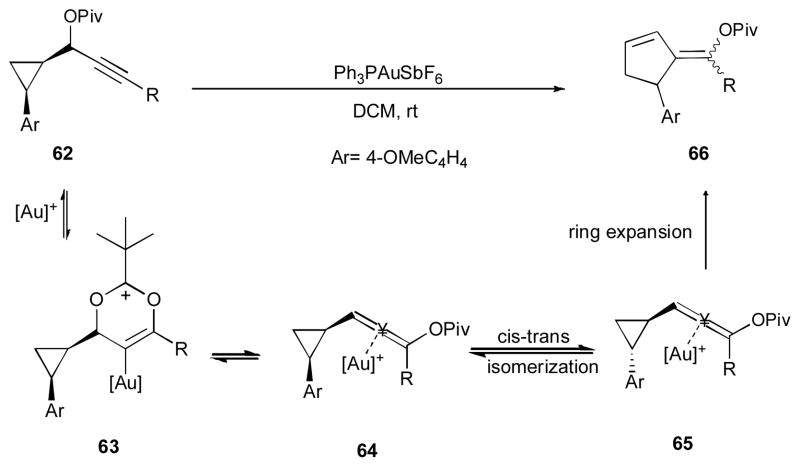

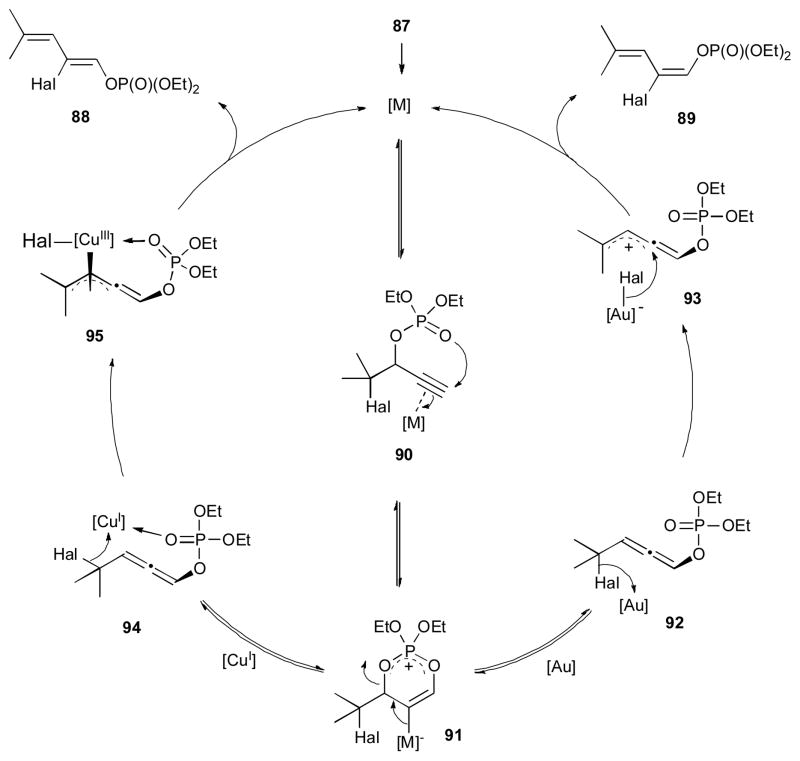

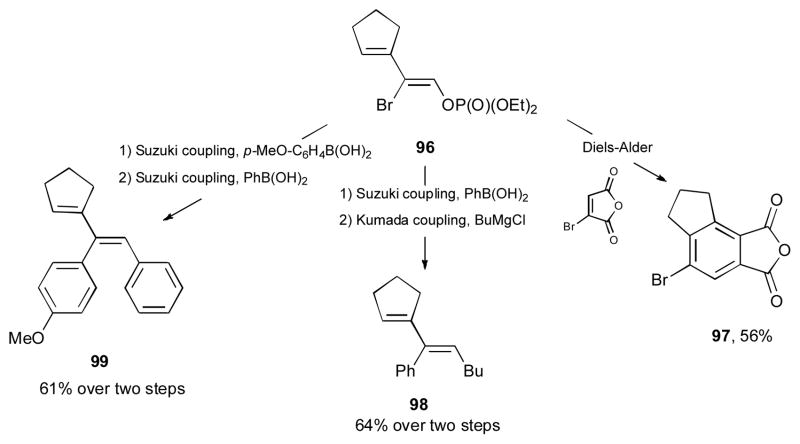

Recently, Gevorgyan and co-workers reported a stereodivergent synthesis of highly functionalized (Z)-1,3-dienes 88 and (E)-1,3-dienes 89 from α-halo propargylic phosphates 87 via a double migratory cascade reaction (Scheme 23).42 It was found that in the presence of catalytic amount of [CuOTf]2•PhH, the Z-diene 88 was formed; while employment of (p-CF3-C6H4)3PAuCl catalyst resulted in the formation of the corresponding E-dienes 89. A variety of cyclic-, acyclic- and heterocyclic-containing substrates 87 were efficiently converted into 1,3-dienes. Chlorine, bromine, and iodine atoms underwent the 1,3-migration in an efficient manner. The proposed mechanism of this cascade reaction involves the coordination of the metal to the π system of the alkyne 90, which triggers a 6-endo-dig cyclization to produce cyclic intermediate 91 (Scheme 24). In the case of the gold catalyst, ring opening of the latter takes place to generate α-halo allenyl phosphate 92, which upon halogen abstraction by gold produces the allyl cation 93. A subsequent delivery of the halide from the gold halide species to 93 takes place anti to the phosphate group to furnish the (E)-diene 89. Alternatively, in the presence of the copper catalyst, allene 94 is generated, in which an additional coordination of the phosphate group to the copper catalyst takes place. Halogen abstraction by the copper in latter produces the π-allyl complex 95, which upon a subsequent phosphate-directed delivery of the halide furnishes the (Z)-diene 88. The synthetic utility of the obtained (Z)-1,3-diene 96 was highlighted in an efficient Diels-Alder reaction with bromomaleic anhydride to afford the corresponding benzene derivative 97 (Scheme 25). The Miyaura-Suzuki cross-coupling reaction of the vinyl bromide moiety followed by the Kumada cross-coupling reaction on terminus phosphate group afforded the hydrocarbon 98. A sequential Miyaura-Suzuki cross-coupling reactions of the vinyl bromide and the phosphate moieties gave access to a multisubstituted diene 99.

Scheme 23.

Stereocontrolled gold- and copper-catalyzed 1,3- OP(O)(OEt)2/1,3-halogen migration towards dienes.42

Scheme 24.

Mechanism of the stereodivergent reaction.42

Scheme 25.

Selective transformations of an obtained product.42

3. Double migratory transformations with an initial 1,2-OXO migration

3.1 Cascade 1,2-OXO/1,2-hydride migration

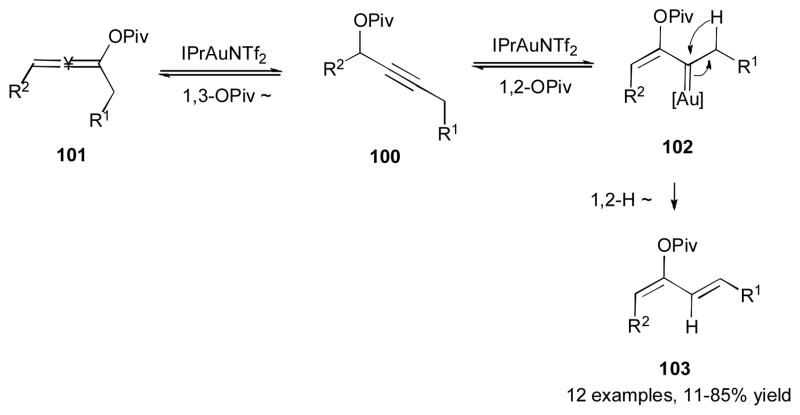

In 2008, Zhang’s group reported the gold-catalyzed stereoselective reaction of propargylic ester 100 toward (1Z, 3E)-diene 103 (Scheme 26).43 Control over regioselectivity in this reaction was achieved by taking advantage of the reversible nature of these transformations. Thus, the electronically unbiased propargyl ester 100 initially undergoes a 1,3-OPiv migration, which is usually preferred for internal alkynes, to produce allene 101 (vide supra). If the latter does not undergo further reactions,40 then the equilibrium shifts back to propargylic pivalate 100. The latter then undergoes a less facile for internal alkynes 1,2-pivaloxy migration to generate the gold carbene 102, which upon irreversible 1,2-hydride shift, produces the 1,3-diene 103.

Scheme 26.

Gold-catalyzed 1,2-OPiv/1,2-H migration cascade for synthesis of 1,3-dienes.43

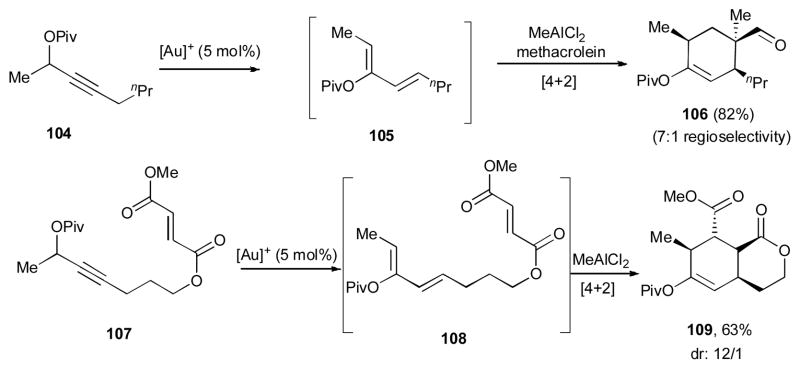

Notably, the obtained dienes in this chemistry were shown to be good partners in the Diels-Alder reaction (Scheme 27). Under the reaction conditions, the propargylic pivalates 104 and 107 initially underwent the double migratory cascade reaction to produce expected 1,3-dienes 105 and 108, which upon the following inter- and intramolecular Diels-Alder reactions furnished the cycloadducts 106 and 109, respectively, in good yields and selectivity.

Scheme 27.

One-pot Au-catalyzed diene formation/Diels-Alder reaction sequence of propargylic pivalates.43

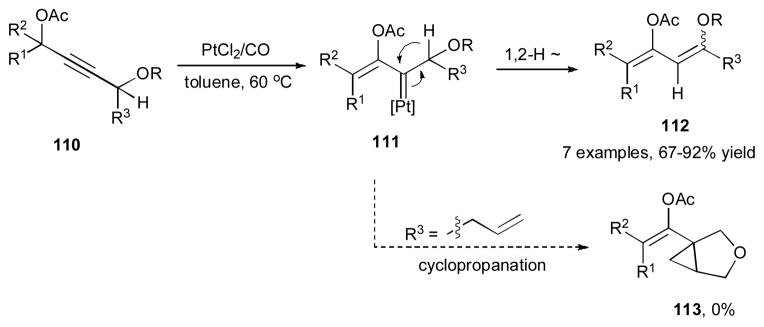

Lee and a co-worker disclosed the Pt-catalyzed synthesis of 1,3-dienes 112 from propargylic acetate 110 (Scheme 28).44 The 1,3-dienes 112 were formed in good yields, albeit with low level of stereoselectivity. Control of regioselectivity was achieved by incorporation of an electron-withdrawing oxygen substituent at the alkyne moiety of the substrate 110. Thus, the 1,2-acyloxy migration occurred over the competitive 1,3-migration to produce platinum carbene 111. The latter, underwent a 1,2-hydride shift45 to furnish the 1,3-diene 112. It is worth mentioning that even in the presence of a tethered alkene, the bicyclic compound 113, the product of potential intramolecular cyclopropanation reaction, was not detected.26

Scheme 28.

Pt-catalyzed 1,2-OAc/1,2-H migration cascade for synthesis of 1,3-dienes.44

3.2 Cascade 1,2-OXO/1,4-allyl migration

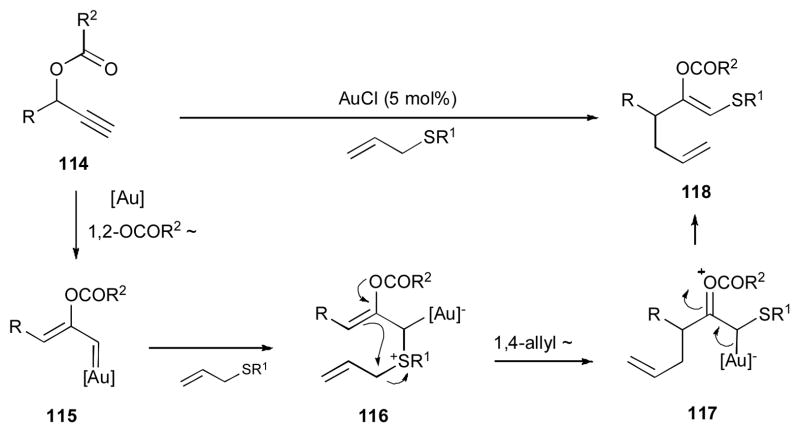

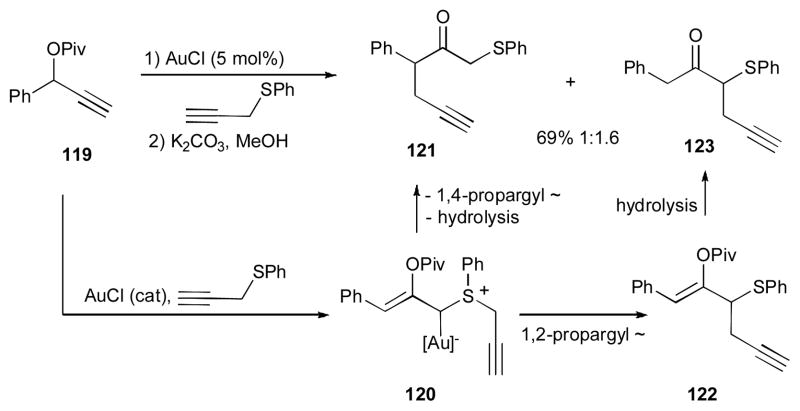

In 2008, Davies reported the gold-catalyzed cascade reaction of propargylic esters 114 in the presence of allyl sulfide and AuCl catalyst to produce 1,5-diene 118 (Scheme 29).46, 47 Various dienes 118, possessing different groups at R, R1, and R2, were obtained under mild reaction conditions. According to the proposed mechanism, the substrate 114, possessing a terminal alkyne moiety, undergoes a 1,2-OCOR2 migration to produce gold carbene 115, which is further attacked by the thioether intermolecularly to afford the thio ylide 116. A subsequent nucleophilic substitution of the enol acetate moiety of the latter at the allylsulfonium moiety results in a formal 1,4-allyl migration to produce compound 117, which upon elimination of the gold catalyst, furnishes the (E)-1,5-diene 118. It is worth mentioning that using propargylic thioether as a nucleophile in the reaction of 119 led to the expected products 121, together with the homopropargyl ketone 123 (Scheme 30). It is believed that after a 1,2-OPiv-migration/nucleophilic attack sequence, ylide 120 (analogue of 116) is formed, which upon 1,4-propargyl migration/hydrolysis affords the expected product 121. In contrast, a 1,2-propargyl migration in 120 gives 122, which is then hydrolyzed into 123.

Scheme 29.

Scheme 30.

Employment of propargylic thioester in gold-catalyzed double migration.46, 47

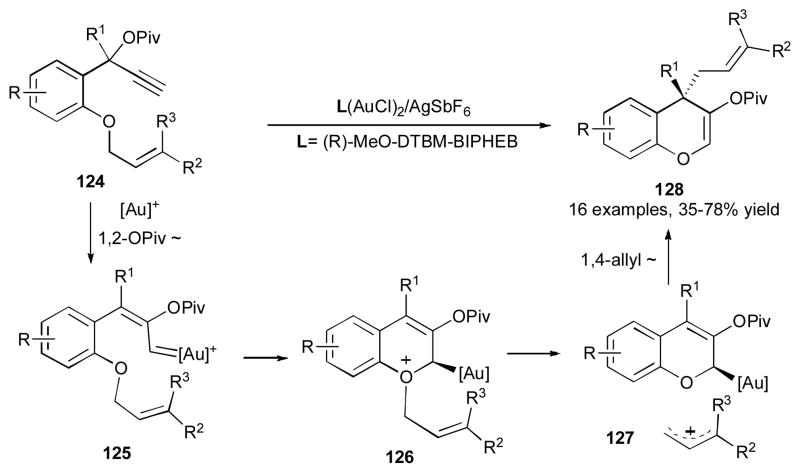

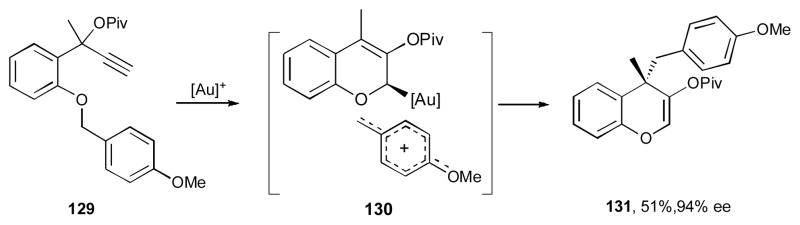

It was shown by Toste’s group that benzopyran 128 can be synthesized via a gold-catalyzed enantioselective cascade 1,2-OPiv/1,4-allyl migration of 124 (Scheme 31).48 Thus, propargyl pivalates 124, possessing a number of different groups at the aromatic ring, the propargylic, and the allylic positions, underwent an efficient and highly enantioselective transformations in the presence of the (R)-MeO-DTBM-BIPHEP- (AuCl)2/AgSbF6 catalyst system. According to the mechanistic hypothesis, substrate 124 possessing a terminal alkyne moiety undergoes a gold-promoted 1,2-pivaloxy migration to produce carbene 125, which upon nucleophilic attack of the ether oxygen atom at the electrophilic center generates the oxonium intermediate 126. Ionization of the allylic group of the latter produces compound 127. The following nucleophilic attack of the allyl gold moiety at the allylic cation furnishes benzopyran 128. Interestingly, when substrate 129, bearing an electron rich para-methoxybenzyl ether moiety, was subjected to the reaction conditions, the benzopyrane 131 was formed (Scheme 32). This observation provides strong support for the formation of intermediate 130 (an analogue of 127), thus suggesting the cationic nature of the second migrating group in this cascade transformation. 48

Scheme 31.

Enantioselective gold-catalyzed 1,2-OPiv/1,4-allyl migration cascade.48

Scheme 32.

Mechanistic studies of the second migration process.48

3.3 Cascade 1,2-OXO/1,2-acyloxy migration

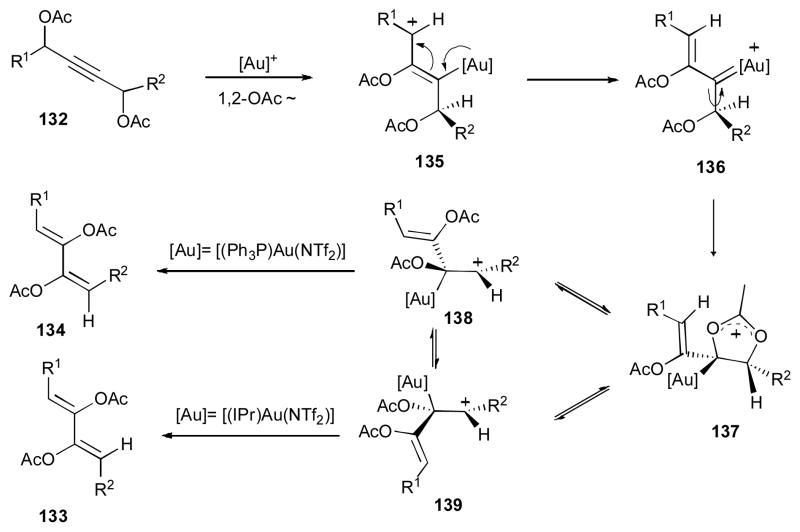

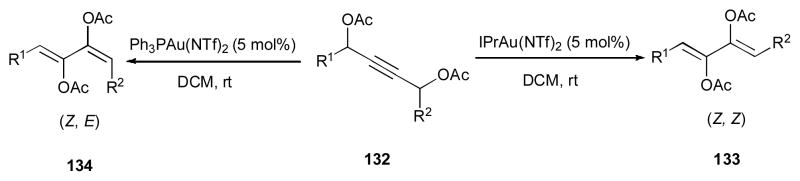

Nevado and co-workers disclosed a stereodivergent formation of 1,3-dienes 133 and 134 via the gold-catalyzed double 1,2-acyloxy migration cascade from the 1,3-bis-propargyl acetate 132 (Scheme 33).49,50 Thus, use of IPrAu(NTf)2 catalyst produces the (Z, Z)-1,3-dienes 133, while employment of Ph3PAuNTf2 catalyst gives the (Z, E)-1,3-diene 134. The proposed mechanism of this reaction involves the gold-promoted 1,2-acyloxy migration to produce compound 135, in which the Z-selectivity of the first migration is dictated by avoiding the 1,3-allylic strain between [Au] and R1 groups (Scheme 34)49. The produced gold carbene 136, upon rotation around the C–C bond and subsequent nucleophilic attack of the adjacent oxygen at the carbene center, gives cyclic intermediate 137. Ring opening of the latter produces cation 138, which in the case of Ph3PAuNTf2 catalyst used directly produces the (Z–E)-1,3-diene 134. On the other hand, 138, possessing bulky IPr ligand of [(IPr)Au(NTf)2] isomerizes to more stable cation 139, which upon elimination of gold produces the (Z–Z)-1,3-diene 133.

Scheme 33.

Stereocontrolled double 1,2-acyloxy migration cascades.49,50

Scheme 34.

Mechanism of double 1,2-acyloxy migration.49

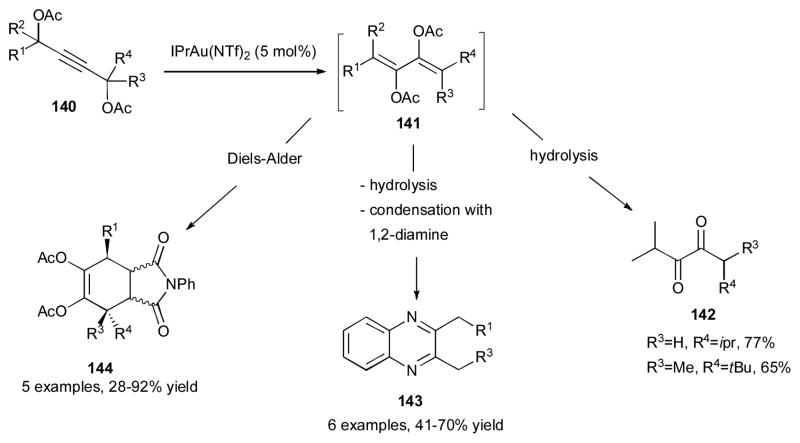

In the following report, the same group clarified more mechanistic details, such as substitution effects at the propargylic position of 132 on the stereochemical outcome of this cascade reaction.50 Additionally, the synthetic utility of obtained products via this chemistry was demonstrated (Scheme 35).50 Thus, after the double migratory cascade reaction of the 1,4-bis-propargylic acetates 140, the obtained dienes 141 could be hydrolyzed to produce the unsymmetrical 1,2-diketones 142. A one-pot cascade double migration/hydrolysis followed by condensation with aromatic 1,2-diamines produced quinoxalines 143 in good yields. The obtained dienes were also shown to be good partners in Diels-Alder reaction with N-phenylmaleimide to produce the cycloadducts 144 with moderate endo selectivity.

Scheme 35.

Synthetic utilities of obtained 2,3-bis-acetoxy-1,3-dienes.50

4. Conclusions

It was demonstrated that the metal-catalyzed 1,3- and 1,2-OXO migrations of propargylic esters and phosphates, which produce activated allenes and metal carbenes, can efficiently be followed by the second migration of different groups. It was shown that the 1,2-H migration in the second process lead to mono-,25,26 bi-,27 tri-,32 tetra,28 and hetrocyclic29 scaffolds, as well as to acyclic 1,3-dienes.43,44 Moreover, employment of alkyl as the second migrating group in these cascade reactions, gaving access to a variety of products including naphthalenes,33,34 dienes,33,36,38,46,47 and substituted chromens.39,48 In addition, double migratory processess involving halogen, acyl, and acyloxy migrating groups, affords β-40 and δ-diketones,41 as well as substituted 1,3-dienes.42,49,50 These cascade reactions are triggered by simple and available catalysts, are highly efficient, and usually take place under mild conditions. A wide range of functional groups such as halogen, allyl, phenoxide, cyclopropane, vinyl silane, olefine, alkyne, acetal, ester, protected alcohol, and protected amine, are tolerated in these transformations. Importantly, the products of the double migratory reactions could be further functionalized, thus offering a set of novel powerful tools for organic synthesis. We anticipate that this tutorial review which highlights this new emerging field, would help researchers to better undrestand the chemistry of migratory cascades, which, in turn, may lead to design of novel useful transformations toward synthetically challenging structures.

Acknowledgments

We greatly acknowledge the National Institute of Health (GM-64444) for financial support.

Notes and references

- 1.Nicolaou KC, Chen JS. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:2993. doi: 10.1039/b903290h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malacria M. Chem Rev. 1996;96:289. doi: 10.1021/cr9500186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tietze LF. Chem Rev. 1996;96:115. doi: 10.1021/cr950027e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marion M, Nolan SP. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:2750. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marco-Contelles J, Soriano E. Chem– Eur J. 2007;13:1350. doi: 10.1002/chem.200601522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang S, Zhang G, Zhang L. Synlett. 2010:6923. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saucy G, Marbet R, Lindlar H, Isler O. Helv Chim Acta. 1959;42:1945. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strickler H, Davis JB, Ohloff G. Helv Chim Acta. 1976;59:1328. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rautenstrauch V. J Org Chem. 1984;49:950. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miki K, Ohe K, Uemura S. J Org Chem. 2003;68:8505. doi: 10.1021/jo034841a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mainetti E, Mouries V, Fensterbank L, Malacria L, Marco-Contelles J. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2002;41:2132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.For early examples see: Sromek AW, Kel’in AV, Gevorgyan V. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2004;43:2280. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353535.Mamane V, Gress T, Krause H, Furstner A. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:8654. doi: 10.1021/ja048094q.Zhang L. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:16804. doi: 10.1021/ja056419c.Shi X, Gorin DJ, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:5802. doi: 10.1021/ja051689g.

- 13.Soriano E, Marco-Contelles J. Chem– Eur J. 2008;14:6771. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johansson MJ, Gorin DJ, Staben ST, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:18002. doi: 10.1021/ja0552500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y, Lu B, Zhang L. Chem Commun. 2010;46:9179. doi: 10.1039/c0cc03669b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parsad BAB, Yoshimoto FK, Sarpong R. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:12468. doi: 10.1021/ja053192c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moreau X, Goddard J, Bernard M, Lemiere G, Manuel Lopez-Romero J, Mainetti E, Marion N, Mouries V, Thorimbert S, Fensterbank L, Malacria M. Adv Synth Catal. 2008;350:43. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garayalde D, Gomez-Bengoa E, Huang X, Goeke A, Nevado C. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:4720. doi: 10.1021/ja909013j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho E. Chem-Eur J. 2012;18:4495. doi: 10.1002/chem.201103799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrak Y, Blaszykowski C, Bernard M, Cariou K, Mainetti E, Mourie’s V, Dhimane A, Fensterbank L, Malacria M. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:8656. doi: 10.1021/ja0474695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johansson MJ, Gorin DJ, Staben ST, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:18002. doi: 10.1021/ja0552500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shu X, Shu D, Schienebeck CM, Tang W. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:7698. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35235d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang G, Peng Y, Cui L, Zhang L. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2009;48:3112. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Witham CA, Mauleon P, Shapiro ND, Sherry BD, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:5838. doi: 10.1021/ja071231+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang L, Wang S. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:1442. doi: 10.1021/ja057327q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lemiere G, Gandon V, Cariou K, Fukuyama T, Dhimane A, Fensterbank L, Malacria M. Org Lett. 2007;9:2207. doi: 10.1021/ol070788r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buzas A, Gagosz F. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:12614. doi: 10.1021/ja064223m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang G, Catalano V, Zhang L. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:11358. doi: 10.1021/ja074536x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwier T, Sromek AW, Yap DML, Chernyak D, Gevorgyan V. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:9868. doi: 10.1021/ja072446m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.For labling studies of the analogous propargylic ester, see: ref. 38.

- 31.For examole, see: Dudnik AS, Sromek AW, Rubina M, Kim JT, Kelin AV, Gevorgyan V. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:1440. doi: 10.1021/ja0773507.

- 32.Bhunia S, Liu RS. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:16488. doi: 10.1021/ja807384a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dudnik AS, Schwier T, Gevorgyan V. Org Lett. 2008;10:1465. doi: 10.1021/ol800229h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dudnik AS, Schwier T, Gevorgyan V. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:1859. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dudnik AS, Schwier T, Gevorgyan V. J Organomet Chem. 2009;694:482. doi: 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2008.08.010. and references therein. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zou Y, Garayalde D, Wang Q, Nevado C, Goeke A. Angew Chem, Int, Ed. 2008;47:10110. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.For a related reaction with the cyclopropyl group at the terminal alkyne position, see: ref. 18. Also, see: Garayalde D, Kruger K, Nevado C. Angew Chem, Int, Ed. 2011;50:911. doi: 10.1002/anie.201006105.

- 38.Mauleon P, Krinsky JL, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:4513. doi: 10.1021/ja900456m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Y, Kuzniewski CN, Rauniyar V, Hoong C, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:12972. doi: 10.1021/ja205068j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang S, Zhang L. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:8414. doi: 10.1021/ja062777j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lebauf D, Simonneau A, Aubert C, Malacria M, Gandon V, Fensterbank L. Angew Chem, Int, Ed. 2011;50:6868. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kazem Shiroodi R, Dudnik AS, Gevorgyan V. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:6928. doi: 10.1021/ja301243t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li G, Zhang G, Zhang L. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:3740. doi: 10.1021/ja800001h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cho E, Lee D. Adv Synth Catal. 2008;350:2719. doi: 10.1002/adsc.200800544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.The generated Pt-carbene from the analogous 1,3-diyne preferentially undergoes cyclopropanation reaction, see: Huang G, Xie K, Lee D, Xia Y. Org Lett. 2012;15:3830. doi: 10.1021/ol301497v.

- 46.Davies PW, Albrecht SJ-C. Chem Commun. 2008:238. doi: 10.1039/b714813e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davies PW, Albrecht SJ-C. Synlett. 2012;23:70. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Uemura M, Watson IDG, Katsukawa M, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:3464. doi: 10.1021/ja900155x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang X, Haro T, Nevado C. Chem-Eur J. 2009;15:5904. doi: 10.1002/chem.200900391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haro T, Gomez-Bengoa E, Cribiu R, Huang X, Nevado C. Chem-Eur J. 2012;18:6811. doi: 10.1002/chem.201103472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]