Abstract

Objective

This study retrospectively examined the daily-level associations between youth alcohol use and dating abuse (DA) victimization and perpetration for a six month period.

Method

Timeline Followback (TLFB) interview data were collected from 397 urban emergency department patients, ages 17–21 years old. Patients were eligible if they reported past month alcohol use and past year dating. Generalized estimating equation (GEE) analyses estimated the likelihood of DA on a given day as a function of alcohol use or heavy use (≥4 drinks per day for females, ≥5 drinks per day for males), as compared to non-use.

Results

Approximately 52% of male and 61% of female participants reported experiencing DA victimization ≥1 times during the past six months, and 45% of males and 55% of females reported perpetrating DA ≥1 times. For both males and females, DA perpetration was more likely on a drinking day as opposed to a non-drinking day (ORs 1.70 and 1.69, respectively). DA victimization was also more likely on a drinking day as opposed to a non-drinking day for both males and females (ORs 1.23 and 1.34, respectively). DA perpetration and DA victimization were both more likely on heavy drinking days as opposed to non-drinking days (2.04 and 2.03 for males’ and females’ perpetration, respectively; and 1.41 and 1.43 for males’ and females’ victimization, respectively).

Conclusions

This study found that alcohol use was associated with increased risk for same day DA perpetration and victimization, for both male and female youth. We conclude that for youth who use alcohol, alcohol use is a potential risk factor for DA victimization and perpetration.

INTRODUCTION

Dating abuse (DA) is a significant public health problem. Every year, approximately ten percent of US high school students experience physical assault by a partner (US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008), and by young adulthood, 40% report at least one instance of physical or sexual victimization (Halpern, Spriggs, Martin, & Kupper, 2009). Consequences of DA can be severe, and may include physical injury, mental health disorders, and death (Amar & Gennaro, 2005; Capaldi & Owen, 2001; Evans, 2008; Foshee, 1996; Johnson, Yanda, & de Vise, 2010; O'Leary, Slep, Avery-Leaf, & Cascardi, 2008; Thomas, Sorenson, & Joshi, 2010). Nationally-representative data suggest that being female, Hispanic, Black, experiencing childhood abuse, having an increased number of dating partners, an early sexual debut, and a family structure other than two parents, each elevate risk for DA victimization (Halpern, et al., 2009; Wolitzky-Taylor et al., 2008). However, typically these effects are not amenable to intervention once DA has occurred. Information about modifiable factors that influence risk for DA is urgently needed in order to improve prevention efforts.

One suspected proximal risk factor for DA is alcohol use. The data on adult alcohol use and intimate partner violence (IPV) are robust; there appears to be little question that heavy drinking is a significant contributing cause of adult IPV perpetration, and that alcohol treatment can reduce adult IPV perpetration behavior (Leonard, 2002; Leonard & Senchak, 1993; Lipsey, Wilson, Cohen, & Derzon, 1997; Ruff, McComb, Coker, & Sprenkle, 2010; Stuart, O'Farrell, & Temple, 2009). One of the most compelling series of studies supporting a probable causal relationship between adult alcohol use and IPV perpetration were event-based analyses of drinking and partner violence conducted between 1999–2005 (Fals-Stewart, 2003; Fals-Stewart, Leonard, & Birchler, 2005; Leonard & Quigley, 1999).1 In an attempt to improve upon the existing evidence at that time, which was purely correlational in nature and did not establish the temporal order between alcohol consumption and partner violence events, the researchers used two methods to assess alcohol use and partner violence at the daily level. First, Fals-Stewart and colleagues trained married couples in which there had been spousal violence to record their alcohol and drug use, and relationship conflict, in daily diaries that were maintained for a five month period. Second, Leonard and Quigley used interview techniques, and Fals-Stewart adapted the widely-used calendar-based Timeline Followback (TLFB) interview technique, to collect retrospective data on alcohol use and partner violence. In their study of drinking and partner violence episodes over the course of one year in a sample of 366 married couples, Leonard and Quigley (1999) found that 38% of severe physically violent episodes were preceded by husbands’ drinking, and that according to both husbands’ and wives’ reports, husbands’ drinking was significantly related to the use of physical violence in marital conflict episodes (ORs 3.1 and 10.7, for wives’ and husbands’ reports, respectively) (Leonard & Quigley, 1999). Next, in their study of 272 couples where the male was known to have perpetrated IPV, Fals-Stewart and colleagues found that on 74% of days when there was physical violence, and on 81% of the days when there was severe physical violence, the male partner had consumed alcohol before the episode (Fals-Stewart, 2003). Males’ drinking increased the odds of a partner violence episode on that day 11 times, and heavy drinking increased the odds approximately 17 times (Fals-Stewart, 2003). In a subsequent study of 149 married or cohabiting couples, Fals-Stewart and colleagues similarly found that on 60% of days when there was physical violence, and on 72% of the days when there was severe physical violence, the male drank alcohol or used drugs prior to the episode, and that the odds of physical violence and severe physical violence subsequent to drinking were 3.4 and 4.0, respectively (Fals-Stewart, et al., 2005). Overall, the evidence for a strong and direct relationship between adult males’ alcohol consumption and subsequent partner violence perpetration was made convincingly by these daily-level analyses. There have been several explanations put forth for why alcohol may influence partner violence perpetration, described in detail elsewhere (see for example (Lipsey, et al., 1997; Rothman, Naughton Reyes, & Johnson, 2011). In brief, these may be summarized as follows: (1) alcohol can impair cognition, leading to misperceptions; (2) chronic alcohol use may impair neuropsychological functioning; (3) alcohol use may reflect situational factors such as relationship dissatisfaction; and (4) alcohol use may be a marker for distress, contexts where there are permissive norms regarding aggression, or other factors that may elevate risk for violence perpetration (Rothman, Naughton Reyes, et al., 2011).

In addition to the three studies which assessed drinking and partner violence, specifically, Parks and colleagues have conducted two studies of the daily relationships between alcohol consumption and sexual and physical violence victimization among college women by any type of perpetrator, using TLFB and interactive voice response methods (Parks & Fals-Stewart, 2004; Parks, Hsieh, Bradizza, & Romosz, 2008). Both of these prior studies found women’s heavy drinking predicted violence victimization; using TLFB methods with a sample of 94 college women over 6 weeks, they found that sexual violence victimization was 3 times higher on days of any alcohol use as compared to non-use, and 9 times higher on heavy drinking days as compared to non-use days (Parks & Fals-Stewart, 2004). Using a telephone interactive voice response daily call system, Parks and colleagues found that college women had 19 times the odds of sexual violence victimization on heavy drinking days as opposed to non-use days, and 12 times the odds of physical violence victimization (by any type of perpetrator) (Parks, et al., 2008). It has been proposed that women’s alcohol consumption may increase risk of sexual violence victimization because it reduces their capacity to physically resist aggressive advances (Mohler-Kuo, Dowdall, Koss, & Wechsler, 2004), their beliefs about the effects of alcohol, cognitive processing deficits, and peer group norms that encourage both drinking and forced sex (Abbey et al., 2002).

The evidence suggestive of a causal relationship between alcohol use and partner violence perpetration in adults is now prompting researchers to consider whether alcohol use may be a causal factor in adolescent DA perpetration, as well (Rothman, Naughton Reyes, et al., 2011). Although at least 29 studies have assessed youth alcohol use and DA perpetration, findings are inconsistent, and the design of these studies do not permit causal inferences to be made (Rothman, Naughton Reyes, et al., 2011). The bulk of the existing studies on youth alcohol consumption and DA perpetration find that the two are globally correlated, meaning that numerous studies have found that self-reported alcohol use and DA over a year or lesser period are statistically associated (see for example: Barnes, Greenwood, & Sommer, 1991; Champion, Foley, Sigmon-Smith, Sutfin, & DuRant, 2008; Hove, Parkhill, Neighbors, McConchie, & Fossos, 2010; Lundeberg, Stith, Penn, & Ward, 2004; Rothman, Johnson, Azrael, Hall, & Weinberg, 2010). However, none of these have examined same day alcohol use and DA perpetration. In addition, a handful of studies have found that alcohol use is associated with DA victimization, but none of these have examined same day alcohol use and DA victimization (Erickson, Gittelman, & Dowd, 2010; Foshee, Benefield, Ennett, Bauman, & Suchindran, 2004; Temple & Freeman, 2011). The lack of data on same day alcohol use and DA among youth is a gap in the field; daily-level analyses of youth alcohol use and DA events are needed to advance our understanding of whether these behaviors are related. Thus, the present study of alcohol use and DA among a sample of pediatric emergency department patients was designed to test the following two primary hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1. Participants will be more likely to report having experienced DA victimization on a day when they drank alcohol as opposed to a day when they drank no alcohol.

Hypothesis 2. Participants will be more likely to report having perpetrated DA on a day when they drank alcohol as opposed to a day when they drank no alcohol.

Related secondary hypotheses to be tested were: (1) that DA victimization and perpetration would be more commonly reported on heavy drinking days than non-drinking days, and (2) that the associations between day of alcohol use and DA would be present across subtypes of abuse (e.g., physical, sexual, emotional) as well as for the aggregate “all types of abuse” category. Because there are gender-based differences in the nature and consequences of DA, and because gender has been found to moderate the associations between other potential risk factors and DA, a stratified analysis was conducted to investigate possible differences by gender (Foshee, 1996; Miller, Gorman-Smith, Sullivan, Orpinas, & Simon, 2009; Walton et al., 2009).

METHOD

Participants

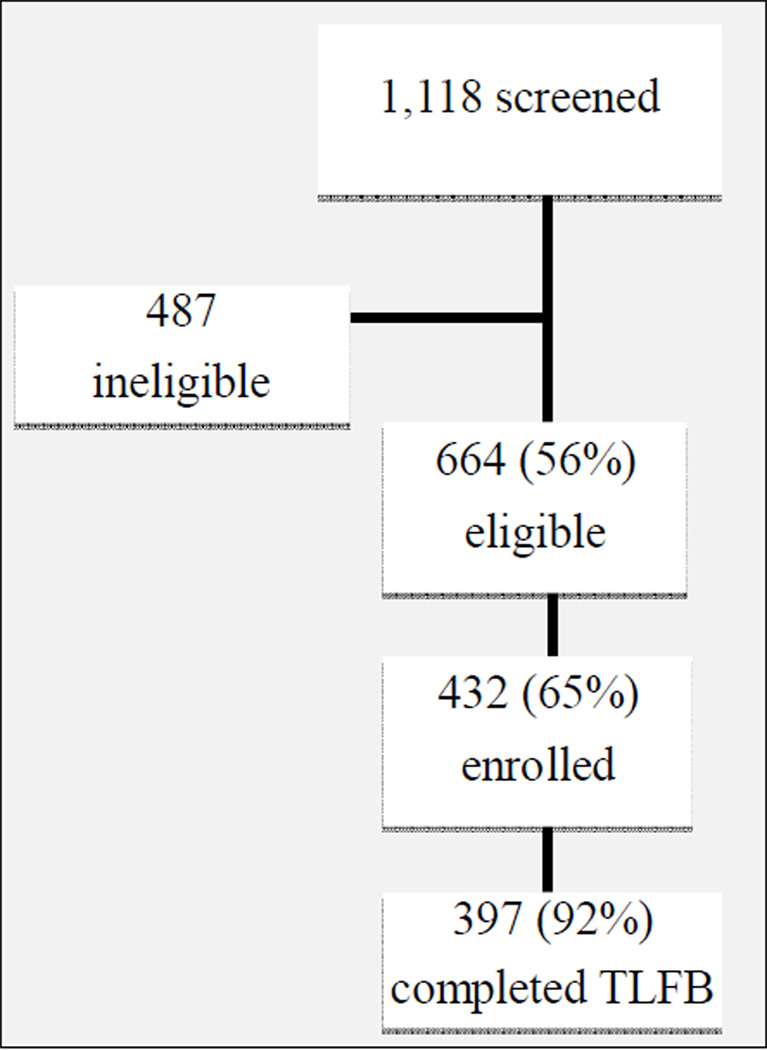

Participants were a convenience sample of 397 pediatric emergency department patients at the Boston University Medical Center (BUMC) hospital between July 2009 and June 2010. BUMC is the largest safety net hospital in New England; approximately 50% of patients are uninsured or on Medicaid. We screened 1,118 patients, of whom 56% were eligible based on age, dating, and alcohol use history; those who had not had a dating partner in the past year (n=125), or a drink of alcohol in the past month (n=316), were not comfortable reading English (n=9), and not between the ages of 17 and 21 years old (n=37) were ineligible. Of those eligible, 65% enrolled and 92% of enrollees completed the TLFB portion of the data collection, resulting in an analytic sample of 397 individuals (Figure 1). Our sample participants were between 17 and 21 years old (mean age: 19.5 years) (Table 1). Approximately 53% were Black, 16% Hispanic, 17% White, and 11% multiracial (Table 1). All study protocols were reviewed and approved by the Boston University Medical Center Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of participant recruitment

Table 1.

Summary of sample characteristics (n=397)

| Characteristic | Mean (standard deviation) |

|---|---|

| Age | 19.5 (1.31) |

| AUDIT score | 7.6 (6.5) |

| Past 6 months | |

| Drinking days | 19.5 (25.9) |

| Heavy drinking days | 9.36 (19.2) |

| Perpetration days | 9.15 (29.5) |

| Victimization days | 14.7 (37.2) |

| Characteristic | Percentage |

| Sex | |

| Male | 44% |

| Female | 56% |

| Race | |

| Black | 53% |

| Hispanic | 16% |

| White | 17% |

| Multiracial | 11% |

| Asian | 2% |

| Other | 1% |

| Parent status | |

| Has children | 19% |

| No children | 81% |

| Dropped out of school | |

| Yes | 16% |

| No | 84% |

Measures

Adolescent dating violence

DA victimization and perpetration were each assessed using a modified version of the Safe Dates Dating Violence Acts Scale items (SDDVAS) (Foshee et al., 1998; Foshee et al., 2009), which has been found to have excellent reliability with adolescent samples (α=0.92) (Foshee et al., 2008). All 18 of the original SDDVAS items were used, including for example “slapped,” “bit” “forced to have sex,” and “beat up.” In addition, the authors added seven original items to assess important forms of dating abuse such as stalking, invasion of privacy, and threats. These included, for example, “broke into email or cell phone,” “stalking,” and “threatened suicide or to hurt self if broke up.” The full list of 25 items is presented in Table 2, grouped into five subtypes of abuse (i.e., physical, severe physical, sexual, psychological or invasion of privacy/harassment). For each subtype of abuse, a binary variable was created that reflected any aggression vs. no aggression. During the TLFB interview, participants were given a card that listed each act next to a number, so that the participants who were uncomfortable speaking the acts aloud could refer to them by number instead. Because sexual and psychological dating abuse can occur via text message, telephone call, or via the internet, we did not restrict dating abuse to days when the participants had in-person contact with a dating partner.

Table 2.

Proportion of sample endorsing each type of dating abuse (N=397)

| Type of dating abuse | Conflict acts included | % of sample reporting ≥1 incident in past 180 days |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perpetration | Victimization | ||||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | ||

| Any | Aggregate (≥1 form listed below) | 45% | 55% | 52% | 61% |

| Physical | Scratched Slapped Physically twisted arm Slammed or held against wall Kicked Bent fingers Bit Pushed grabbed or shoved Tried to choke Caused an injury/caused hurt that required medical attention Threw something that hit partner Burned Hit with a fist Hit with something hard besides a fist Beat up Assaulted with a knife or gun |

22% | 41% | 37% | 38% |

| Severe physical | Tried to choke Caused an injury or medical attention Burned Hit with a fist Hit with something hard besides a fist Beat up Assaulted with a knife or gun |

15% | 29% | 23% | 29% |

| Sexual | Forced to have sex Forced to do other sexual things that did not want to do |

3% | 10% | 8% | 7% |

| Psychological | Made them feel afraid Destroyed or tried to destroy property Threatened to kill Threatened suicide or to hurt self if broke up |

2% | 12% | 18% | 25% |

| Invasion of privacy or harassment | Spread nasty rumors Broke into email or cell phone Stalking |

19% | 22% | 22% | 32% |

Alcohol use

The number of drinks that participants consumed on a given day was assessed by asking them to indicate how many drinks, and what kind of alcohol, they had consumed. Participants were given a prepared card to consult that specified that “a drink” was the equivalent of 12 ounces of beer, 5 ounces of wine, 3 ounces of fortified wine, and 1.5 ounces of hard liquor. The card also specified that “a fifth” is the equivalent of 17 standard drinks and that ¼ of a 40 ounce malt liquor bottle was the equivalent of one standard drink. Consistent with prior research, days when females drank ≥4 drinks on a given day, or males drank ≥5 drinks on a given day, were classified as heavy alcohol consumption days (Fals-Stewart, et al., 2005).

Procedures

Participants completed a survey and the TLFB interview while they were waiting to receive medical care in their treatment room. Most participants completed the survey and TLFB in one hour. The survey and interview were designed to be easily stopped and re-started so that data collection would not interfere with medical care. Participation was voluntary and anonymous. Participants who were unaccompanied by an adult guardian and younger than age 18 were able to provide their own assent, otherwise, consent was sought from minors’ parents/guardians. All parents, friends, intimate partners and other non-patient visitors accompanying the participants were required to wait outside the room while the participant completed the survey and interview. Participants received $20 compensation.

TLFB interview procedures

A standard domestic violence TLFB interview procedure was used (Sobell & Sobell, 1996; Vendetti, Stappenbeck, & Fals-Stewart, 2004). Participants were shown a calendar that included one page for each month starting with the present month and going backwards, chronologically, six months. Holidays were marked, as were important local dates, such as public school holiday weeks. Participants were interviewed about their alcohol use, illegal drug use, DA victimization, and DA perpetration, in that order. For each topic, the research assistant (RA) would start by handing the participant a prepared card with definitions or listed acts (see measures section for details about the alcohol and dating violence cards). Next, the RA would circle the present day on the calendar and say, for example, “Here is today on the calendar. Have you had any alcoholic drinks today?” After the participant responded, the RA would mark the response on the calendar and move to the prior day and ask, “Did you have anything to drink yesterday?” After the response, the RA would mark the response and continue to work backwards, asking “What about the other days this week, or over the weekend?” With some participants, the RA was able to establish a drinking pattern, such as every Saturday night. In these cases, the RA would use the holidays and vacation week dates to probe the participant and ask, “I have marked you drank every Saturday night. Let’s look back to see if there were any times that you drank on a day that wasn’t a Saturday.” She would then prompt the participant to consider holidays, birthdays of family members, and any other significant dates on the calendar to try to recall drinking days. Once the calendar was complete for a particular topic, the RA and participant would return to the present date in order to consider the next topic. To capture DA events, the RA would hand the participant a card listing abusive acts and ask if any occurred on the present day, the day before, and so on. She would probe by asking the participant to recall when he or she started dating their current or most recent partners, when they broke up, anniversaries they celebrated, and other special events that marked the course of their relationship as a way of prompting them to recall when conflicts took place. Using these techniques, drinking and DA behavior were captured for six month period. Although no data about the reliability and validity of using the TLFB to collect DA data from adolescents for a six month period is available, the validity of the TLFB interview for collecting sensitive data from adults (e.g., alcohol and drug use, partner violence) is excellent (Fals-Stewart, Birchler, & Kelley, 2003; Lam, Fals-Stewart, & Kelley, 2009; Sobell & Sobell, 1996), and the psychometric properties for use with adolescents are also excellent (Collins, Kashdan, Koutsky, Morsheimer, & Vetter, 2008; Dennis, Funk, Godley, Godley, & Waldron, 2004; Waldron, Slesnick, Brody, Turner, & Peterson, 2001).

Overview of analytic strategy

Data were analyzed using SAS/STAT software, Version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, 2008). Generalized estimating equation (GEE) analyses with a logit link function were used to account for the potential correlations within each participant's responses to the TLFB interview. The dependent measures were the occurrence of DA perpetration or victimization on a given day, and the participant's alcohol consumption on the same day was the independent measure. Alcohol consumption was categorized as none or any (i.e., one or more standard drinks), and heavy alcohol consumption vs. none. The target interval for each interview was the 6-month period preceding the interview. For all analyses, odds ratios (ORs) were used to measure the strength of the associations and 95% confidence intervals were used to assess their statistical stability. For the GEE analyses, an exchangeable covariance structure was used.

RESULTS

Approximately 52% of male and 61% of female participants reported experiencing DA victimization ≥1 times during the past six months, and 45% of males and 55% of females reported perpetrating DA ≥1 times (Table 2). On average, participants had 8 victimization days and 9 perpetration days in the past six months (Table 1). By gender, approximately 52.0% of males and 61.3% of females reported that ≥1 incident of DA victimization had occurred during the six month assessment period, and 44.6% of males and 55.0% of females reported that ≥1 incident of DA perpetration had occurred during that time (not shown). Approximately 72.0% of males and 66.7% of females reported ≥1 incident of heavy drinking during the six month assessment period (not shown).

Hypothesis 1, that DA victimization would be more likely on a drinking day as opposed to a non-drinking day, was supported for both females and males. Females had 1.34 times the odds of experiencing DA victimization (victimization of any type) on a day when they consumed any alcohol as opposed to a day when they consumed no alcohol (OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.09–1.66), and males had 1.23 times the odds (OR 1.23, 95% CI 0.97–1.56, p<.10). When DA victimization was analyzed by subtype, only the relationship between psychological abuse victimization and drinking was significant for females, who had 1.26 times the odds of experiencing psychological DA victimization on a drinking day as opposed to a non-drinking day (OR 1.26, 95% CI 1.00–1.59, p<.05); and only the relationship between physical abuse victimization and drinking was significant for males, who had 1.71 times the odds of experiencing physical dating abuse victimization on a drinking day as opposed to a non-drinking day (OR 1.71, 95% CI 0.98–2.97, p<.10) (Table 3). Hypothesis 2, that DA perpetration would be more likely on a drinking day as opposed to a non-drinking day, was supported for both males and females; males had 1.70 times the odds of DA perpetration on a drinking day as a non-drinking day, and females had 1.69 times the odds of DA perpetration on a drinking day as opposed to a non-drinking day (OR 1.70, 95% CI 1.09–2.66; OR 1.69, 95% CI 1.25–2.30, respectively) (Table 3). In terms of the subtypes of DA, for both males and females, physical dating violence perpetration and invasion of privacy/harassment perpetration were both more likely to occur on drinking days as opposed to non-drinking days (Table 3).

Table 3.

Parameter estimates for logistic regression model assessing the daily relationship between alcohol consumption and dating violence victimization and perpetration, by gender (N=397)

| Fixed effects | Males (N=175) | Females (N=222) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | n | Odds ratio (95% CI) | n | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

| Any alcohol consumption (vs. none) | ||||

| Any dating aggression | ||||

| Victimization | 330 | 1.23 (0.97, 1.56)* | 645 | 1.34 (1.09, 1.66)*** |

| Perpetration | 200 | 1.70 (1.09, 2.66)** | 537 | 1.69 (1.25, 2.30)**** |

| Physical dating violence | ||||

| Victimization | 60 | 1.71 (0.98, 2.97)* | 198 | 1.06 (0.67, 1.69) |

| Perpetration | 24 | 2.16 (1.20, 3.90)** | 256 | 2.02 (1.03, 3.96)** |

| Severe physical violence | ||||

| Victimization | 44 | 1.65 (0.83, 3.29) | 147 | 0.97 (0.56, 1.67) |

| Perpetration | 21 | 2.17 (1.10, 4.29)** | 188 | 2.49 (0.73, 8.56) |

| Sexual dating violence | ||||

| Victimization | 4 | 2.00 (0.68, 5.89) | 13 | 0.77 (0.22, 2.75) |

| Perpetration | 3 | 4.08 (0.45, 37.03) | 89 | 1.26 (0.60, 2.66) |

| Psychological dating violence | ||||

| Victimization | 100 | 1.31 (0.81, 2.11) | 253 | 1.26 (1.00, 1.59)** |

| Perpetration | 20 | 5.72 (0.65, 50.59) | 78 | 1.91 (0.78, 4.63) |

| Invasion of privacy/harassment | ||||

| Victimization | 84 | 1.45 (0.91, 2.29) | 269 | 1.30 (0.94, 1.79) |

| Perpetration | 25 | 2.55 (1.05, 6.21)** | 151 | 2.04 (0.88, 4.71)* |

| Heavy alcohol consumption (vs. none) | ||||

| Any dating aggression | ||||

| Victimization | 253 | 1.41 (0.98, 2.04)* | 392 | 1.43 (1.03, 1.99)** |

| Perpetration | 155 | 2.04 (0.98, 4.28)* | 276 | 2.03 (1.30, 3.17)*** |

| Physical dating violence | ||||

| Victimization | 40 | 2.51 (1.47, 4.31)**** | 140 | 1.14 (0.68, 1.92) |

| Perpetration | 19 | 3.18 (1.61, 6.26)**** | 161 | 2.21 (0.74, 6.61) |

| Severe physical violence | ||||

| Victimization | 29 | 2.11 (0.99, 4.48)* | 96 | 0.97 (0.58, 1.65) |

| Perpetration | 18 | 3.34 (1.54, 7.24)*** | 134 | 2.53 (0.28, 23.24) |

| Sexual dating violence | ||||

| Victimization | 2 | 1.83 (0.54, 6.16) | 13 | 1.35 (0.30, 6.18) |

| Perpetration | 3 | 8.43 (0.92, 77.10)* | 78 | 5.55 (0.29, 105.6) |

| Psychological dating violence | ||||

| Victimization | 79 | 1.74 (0.92, 3.29)* | 197 | 1.21 (0.81, 1.81) |

| Perpetration | 19 | 12.38 (1.60, 95.54)** | 66 | 4.24 (0.40, 44.69) |

| Invasion of privacy/harassment | ||||

| Victimization | 66 | 1.88 (0.94, 3.74)* | 201 | 1.34 (0.78, 2.32) |

| Perpetration | 17 | 3.06 (0.87, 10.75)* | 71 | 2.36 (0.82, 6.82) |

=p<.10,

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

Our other secondary hypotheses were that DA victimization and perpetration would be more commonly reported on heavy drinking days than on non-drinking days. For both males and females, this hypothesis was supported. On heavy drinking as opposed to a non-drinking days, males had 1.41 times the odds of DA victimization, and females had 1.43 times the odds of DA victimization. Both males and females had twice the odds (2.04 and 2.03, respectively) of DA perpetration on heavy drinking days as opposed to non-drinking days (Table 3). In addition, examining the relationship between heavy drinking and subtypes of abuse, males were significantly more likely to experience physical, severe physical, and psychological DA victimization, and invasion of privacy/harassment, on a heavy drinking day as opposed to a non-drinking day (Table 3). Males were also significantly more likely to perpetrate each of the five forms of DA assessed on a heavy drinking day as opposed to a non-drinking day. For females, the relationships between heavy drinking and DA was only significant for the aggregated “any type” DA victimization and perpetration variables, and not for any of the subtypes of abuse variables.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first investigation of the relationship between youth alcohol use and DA at the daily level. Consistent with prior daily-level research on adult alcohol use and IPV, we found that DA events were substantially more likely to occur on drinking days than non-drinking days (Fals-Stewart, 2003; Fals-Stewart, et al., 2005; Leonard & Quigley, 1999). Specifically, we found that youth in the sample had a 23–34% greater odds of being victimized on days that they drank alcohol as compared to non-drinking days, and a 70% greater odds of perpetrating DA on days when they drank. The relationship between heavy drinking and DA was, as anticipated, even stronger; both males and females had 41–43% greater odds of victimization on days that they drank, and both males and females were almost twice as likely to perpetrate DA on drinking days as compared to non-drinking days. The associations between drinking and DA were apparent for the broad measure of “any dating violence,” and for some specific sub-types of DA as well.

The idea that alcohol may play a causal role in dating violence victimization and/or perpetration is controversial for some battered women’s advocates (see for example Zubretsky and Digirolamo’s “The false connection between adult domestic violence and alcohol”, 1996), primarily because of a concern that the perpetrators will not be held accountable if alcohol is perceived to be a valid excuse for the crime. Thus, our finding that youth alcohol consumption was related, on the daily level, to DA perpetration and victimization, may surprise some practitioners. It is important to note that while our findings support the contention that youth alcohol use may elevate risk for DA perpetration and/or victimization, these results do not suggest that the perpetrators are not culpable for their behavior. Rather, our findings contribute to accumulating evidence that for at least a subset of youth, DA is but one of several interrelated problem behaviors (including peer violence, sibling violence, drug use, tobacco use, pornography use, gang involvement and delinquency) that are also associated with alcohol use. Two prevention strategies are indicated. First, we should investigate whether reducing alcohol availability, teaching young people to drink responsibly, altering alcohol expectancies, or changing norms related to accepting drunkenness as an excuse for antisocial behavior may also reduce DA perpetration. Second, we should test strategies that target individuals early in their life-course, and address “upstream” causes of both alcohol use and DA (Rothman et al., 2011; Rothman, et al., 2010). Developing prevention strategies that impart healthy interpersonal relationship skills, coping and problem solving skills, and offer meaningful academic and employment opportunities, may simultaneously address risk for multiple interconnected adolescent problem behaviors more successfully than piecemeal strategies for each separate behavior.

Our finding that heavy alcohol consumption was associated with each subtype of males’ DA victimization and perpetration behavior is consistent with prior studies that have found that in general, adolescents’ violent behavior is influenced by alcohol consumption (Maldonado-Molina, Jennings, & Komro, 2010; Maldonado-Molina, Reingle, & Jennings, 2011; White, Loeber, Stouthamer-Loeber, & Farrington, 1999). A richer understanding of why and how alcohol consumption may influence DA is needed. There are several possible reasons for the association, including: (1) youth participants may have had strong alcohol-aggression expectancies, (2) participants may have been more likely to report DA as co-occuring with drinking because they felt it reduced the stigma of having been involved in a DA incident; and (3) participants may have been more likely to engage in DA when drinking because they believed that they would face less severe consequences (i.e., a type of deviance disavowal). Each of these possible reasons for an alcohol-violence link have been explored by other researchers relative to other forms of violence, such as sexual assault (Davis, 2010; Wild, Graham, & Rehm, 1998), adult partner violence (Leonard, 2002), and general violence (Wild, et al., 1998). Additional research that explores the reasons for a possible alcohol-DA link, specifically, is needed.

In this study, no efforts were made to establish the temporal order of drinking and DA when they occurred on the same day. An important next step for the field would be an event-based study that pinpoints the time of day when youth consume alcohol and when youth engage in DA, in order to assess the temporal order of these events. Until the temporal order is empirically established, it remains possible that the daily-level correlation that we found in this study reflects a tendency for some youth to engage in violence and drink subsequently.

Limitations

This study was subject to at least four limitations. First, while the TLFB interview procedure is the most widely used calendar-based retrospective data collection method in the field, and it has excellent reliability and validity for adults (Fals-Stewart, et al., 2003; Lam, et al., 2009; Sobell & Sobell, 1996), and for adolescents over a three month period (Dennis, et al., 2004; Waldron, et al., 2001), the psychometrics have not been assessed for adolescents relative to dating violence nor for a six month period. Our rationale for extending the data collection timeframe to six months was that data violence events were relatively rare among our sample, and a 90 day timeframe would not have offered sufficient events for this analysis; 48% of the perpetration events we captured occurred in the fourth, fifth and sixth months assessed. The greatest risk to the integrity of these data is that adolescents were not recalling all of the dating violence events that they experienced, or were systematically more likely to recall events that coincided with alcohol use. If this systematic recall bias occurred, our results would be biased away from the null. Another consideration is whether the order of the TLFB questions (that is, alcohol use recall questions first, dating abuse recall questions second) could have influenced the results—it is possible that asking dating abuse first and alcohol second could have produced different results. Additional research that establishes the psychometrics of the TLFB interview for DA with youth is needed, as well as research that tests whether the TLFB can be used to gather data reliably up to six months in the past. Second, the sample was drawn from an urban pediatric emergency department setting. Thus, results may not be generalizable to adolescents in general. Moreover, adolescents who had not had a drink of alcohol in the past month were excluded from the study because our purpose was to be able to analyze the co-occurrence of drinking and dating abuse events; including non-drinking adolescents would have generated data about dating abuse events alone. Therefore, our results are only generalizable to youth who use alcohol at least once per month. Replication of our findings with additional samples from other settings would benefit the field. Third, some subtypes of abuse were rarely reported (e.g., sexual abuse perpetration). As a result, confidence intervals for the relationship between alcohol use and these types of abuse perpetration were very wide. Additional studies with larger samples may have better precision. Finally, we did not collect data about the reason for the patients’ admission to the emergency department. If patients who were admitted for reasons related to dating abuse or alcohol use were systematically less likely (or more likely) to be screened for or enrolled in this study, and these patients had a different daily pattern of alcohol use and dating abuse than patients who presented to the emergency department for other reasons, our estimates could be biased. Future studies of this nature should record the reason for patient emergency department admission.

Conclusions

This study of DA perpetration and victimization among an urban, emergency department sample of racially and ethnically diverse youth found that heavy alcohol use was associated with increased risk for same day DA victimization and perpetration, for both males and females. In addition, we found that any alcohol consumption (vs. none) was associated with DA victimization among females, and DA perpetration among both males and females. On the basis of these findings, we conclude that for youth who use alcohol, alcohol use is a potential risk factor for DA victimization and perpetration.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported in part by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grants K01AA017630 awarded to Emily F. Rothman and K24AA019707 and Gregory Stuart. The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the research assistants: Cassandra Abueg, Kelley Adams, Brandy Carlson, Lindsay Cloutier, Abigail Isaacson, Sheila Kelly, Joanna Khalil, Andrea Lenco, Alexis Marbach, and Lucy Stelzner; and the care providers in the pediatric emergency department.

Footnotes

There have been questions about the integrity of some of Fals-Stewart’s data (State of New York v. Fals-Stewart, 2010).

REFERENCES

- Abbey A, Zawacki T, Buck PO, Testa M, Parks K, Norris J, Martell J. How does alcohol contribute to sexual assault? Explanations from laboratory and survey data. Alcoholism. 2002;26(4):575–581. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amar AF, Gennaro S. Dating violence in college women: Associated physical injury, healthcare usage, and mental health symptoms. Nurs. Res. 2005;54(4):235–242. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200507000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes GE, Greenwood L, Sommer R. Courtship violence in a Canadian sample of male college students. Family Relations. 1991;40(1):37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Owen LD. Physical aggression in a community sample of at-risk young couples: Gender comparisons for high frequency, injury, and fear. J. Fam. Psychol. 2001;15(3):425–440. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.3.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champion H, Foley KL, Sigmon-Smith K, Sutfin EL, DuRant RH. Contextual factors and health risk behaviors associated with date fighting among high school students. Women Health. 2008;47(3):1–22. doi: 10.1080/03630240802132286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LR, Kashdan TB, Koutsky JR, Morsheimer ET, Vetter CJ. A self-administered Timeline Followback to measure variations in underage drinkers' alcohol intake and binge drinking. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33(1):196–200. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KC. The influence of alcohol expectancies and intoxication on men's aggressive unprotected sexual intentions. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2010;18(5):418–428. doi: 10.1037/a0020510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Funk R, Godley SH, Godley M, Waldron H. Cross-validation of the alcohol and cannabis use measures in the Global Appraisal of Individual Needs (GAIN) and Timeline Followback (TLFB; Form 90) among adolescents in substance abuse treatment. Addiction. 2004;99(Suppl2):120–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson MJE, Gittelman MA, Dowd D. Risk factors for dating violence among adolescent females presenting to the pediatric emergency department. J. Trauma-Injury Infect. Crit. Care. 2010;69(4):S227–S232. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181f1ec5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans T. Joshua Bean gets 68 years for murder of Heather Norris. The Indianapolis Star. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W. The occurrence of partner physical aggression on days of alcohol consumption: A longitudinal diary study. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2003;71(1):41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, Birchler GR, Kelley ML. The Timeline Followback spousal violence interview to assess physical aggression between intimate partners: Reliability and validity. J. Fam. Violence. 2003;18(3):131–142. [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, Leonard KE, Birchler GR. The occurrence of male-to-female intimate partner violence on days of men's drinking: The moderating effects of antisocial personality disorder. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2005;73(2):239–248. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee V. Gender differences in adolescent dating abuse prevalence, types and injuries. Health Education Research. 1996;11(3):275–286. [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA. Gender differences in adolescent dating abuse prevalence, types and injuries. Health Education Research. 1996;11(3):275–286. [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Bauman KE, Arriaga XB, Helms RW, Koch GG, Linder GF. An evaluation of Safe Dates, an adolescent dating violence prevention program. AmJPublic Health. 1998;88(1):45–50. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Benefield T, Suchindran C, Ennett ST, Bauman KE, Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Mathias J. The development of four types of adolescent dating abuse and selected demographic correlates. J. Res. Adolesc. 2009;19(3):380–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00593.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Benefield TS, Ennett ST, Bauman KE, Suchindran C. Longitudinal predictors of serious physical and sexual dating violence victimization during adolescence. Prev. Med. 2004;39(5):1007–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Karriker-Jaffe KJ, McNaughton Reyes HL, Ennett ST, Suchindran C, Bauman KE, Benefield TS. What accounts for demographic differences in trajectories of adolescent dating violence? An examination of intrapersonal and contextual mediators. J. Adolesc. Health. 2008;42(6):596–604. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern C, Spriggs A, Martin S, Kupper L. Patterns of intimate partner violence victimization from adolescence to young adulthood in a nationally representative sample. J. Adolesc. Health. 2009;45(5):508–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hove MC, Parkhill MR, Neighbors C, McConchie JM, Fossos N. Alcohol consumption and intimate partner violence perpetration among college students: The role of self-determination. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71(1):78–85. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J, Yanda S, de Vise D. Yeardley Love funeral: Thousands of mourners gather to remember U-Va. student. The Washington Post. 2010 May 9; 2010, Retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/05/08/AR2010050802136.html.

- Lam WKK, Fals-Stewart W, Kelley M. The Timeline Followback interview to assess children's exposure to partner violence: Reliability and validity. J. Fam. Violence. 2009;24(2):133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE. Alcohol's role in domestic violence: a contributing cause or an excuse? Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2002;106:9–14. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.106.s412.3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Quigley BM. Drinking and marital aggression in newlyweds: An event-based analysis of drinking and the occurrence of husband marital aggression. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60(4):537–545. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Senchak M. Alcohol and premarital aggression among newlywed couples. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1993;(SUPPL 11):96–108. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1993.s11.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey MW, Wilson DB, Cohen MA, Derzon JH. Recent Developments in Alcoholism. Vol. 13. New York: Plenum Press; 1997. Is there a causal relationship between alcohol use and violence? A synthesis of evidence. In M Galanter (Ed.), pp. 245–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundeberg K, Stith SM, Penn CE, Ward DB. A comparison of nonviolent, psychologically violent, and physically violent male college daters. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004;19(10):1191–1200. doi: 10.1177/0886260504269096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado-Molina MM, Jennings WG, Komro KA. Effects of alcohol on trajectories of physical aggression among urban youth: An application of latent trajectory modeling. J. Youth Adolesc. 2010;39(9):1012–1026. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9484-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado-Molina MM, Reingle JM, Jennings WG. Does alcohol use predict violent behaviors? The relationship between alcohol use and violence in a nationally representative longitudinal sample. Youth Violence Juv. Justice. 2011;9(2):99–111. doi: 10.1177/1541204010384492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S, Gorman-Smith D, Sullivan T, Orpinas P, Simon TR. Parent and peer predictors of physical dating violence perpetration in early adolescence: Tests of moderation and gender Differences. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2009;38(4):538–550. doi: 10.1080/15374410902976270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler-Kuo M, Dowdall GW, Koss MP, Wechsler H. Correlates of rape while intoxicated in a national sample of college women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65(1):37–45. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary KD, Slep AMS, Avery-Leaf S, Cascardi M. Gender differences in dating aggression among multiethnic high school students. J. Adolesc. Health. 2008;42(5):473–479. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks K, Fals-Stewart W. The temporal relationship between college women's alcohol consumption and victimization experiences. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:625–629. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000122105.56109.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks K, Hsieh Y, Bradizza C, Romosz A. Factors influencing the temporal relationship between alcohol consumption and experiences with aggression among college women. Psychol Addict Behav. 2008;22(2):210–218. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman EF, Decker MR, Miller E, Reed E, Raj A, Silverman JG. Multi-person sex among a sample of adolescent female urban health clinic patients. Journal of Urban Health. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9630-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman EF, Johnson RM, Azrael D, Hall DM, Weinberg J. Perpetration of physical assault against dating partners, peers, and siblings among a locally representative sample of high school students in Boston, Massachusetts. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2010;164(12):1118–1124. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman EF, Naughton Reyes HL, Johnson RM. Does the alcohol make them do it?: A systematic review of the literature on dating violence perpetration and drinking among youth. Epidemiological Reviews. 2011 doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxr027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruff S, McComb JL, Coker CJ, Sprenkle DH. Behavioral Couples Therapy for the treatment of substance abuse: A substantive and methodological review of O'Farrell, Fals-Stewart, and colleagues' program of research. Fam. Process. 2010;49(4):439–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2010.01333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS® 9.2. Cary, NC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. A calendar method for assessing alcohol and drug use. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Addiction Research Foundation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart GL, O'Farrell TJ, Temple JR. Review of the association between treatment for substance misuse and reductions in intimate partner violence. Subst. Use Misuse. 2009;44(9–10):1298–1317. doi: 10.1080/10826080902961385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple JR, Freeman DH. Dating Violence and substance use among ethnically diverse adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26(4):701–718. doi: 10.1177/0886260510365858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas KA, Sorenson SB, Joshi M. Police-documented incidents of intimate partner violence among young women. J. Womens Health. 2010;19(6):1079–1087. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance--United States, 2007 (Surveillance Summaries, June 6, 2008) MMWR, 57(No. SS-4) 2008:1–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vendetti K, Stappenbeck C, Fals-Stewart W. The timeline followback spousal violence interview: A user's guide. Buffalo, NY: Addiction and Family Research Group; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Waldron HB, Slesnick N, Brody JL, Turner CW, Peterson TR. Treatment outcomes for adolescent substance abuse at 4-and 7-month assessments. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2001;69(5):802–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton MA, Cunningham RM, Goldstein AL, Chermack ST, Zimmerman MA, Bingham CR, Blow FC. Rates and correlates of violent behaviors among adolescents treated in an urban emergency department. J. Adolesc. Health. 2009;45(1):77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Farrington DP. Developmental associations between substance use and violence. Dev. Psychopathol. 1999;11(4):785–803. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild TC, Graham K, Rehm J. Blame and punishment for intoxicated aggression: when is the perpetrator culpable? Addiction. 1998;93(5):677–687. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.9356774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolitzky-Taylor KB, Ruggiero M, Danielson CK, Resnick HS, Hanson RF, Smith DW, Kilpatrick DG. Prevalence and correlates of dating violence in a national sample of adolescents. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. 2008;47(7):755–762. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318172ef5f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]