Abstract

Background

To compare the benefit of Beta Blockers (BB) in heart failure (HF) with preserved vs. reduced ejection fraction (EF).

Methods and Results

Retrospective study of insured patients who were hospitalized for HF between January 2000 and June 2008. Pharmacy claims were used to estimate BB exposure over six-month rolling windows. The association between BB exposure and all-cause hospitalization or death was tested using time-updated proportional hazards regression, with adjustment for baseline covariates and other HF medication exposure. The groups were compared by stratification (EF <50% vs. ≥50%) and using an EF-group*BB exposure interaction term. 1835 patients met inclusion criteria; 741 (40%) with a preserved EF. Median follow up was 2.1 years. In a fully-adjusted multivariable model, BB exposure was associated with a decreased risk of death or hospitalization in both groups (EF<50% hazard ratio [HR] 0.53, p<0.0001; EF≥50% HR 0.68, p=0.009). There was no significant difference in this protective association between groups (interaction p=0.32).

Conclusion

BB exposure was associated with a similar protective effect in terms of time to death or hospitalization in HF patients regardless of whether EF was preserved or reduced. An adequately powered randomized trial of BB in HF with preserved EF is warranted.

Keywords: beta adrenergic receptor blocker, hospitalization, diastolic dysfunction, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

INTRODUCTION

Approximately fifty percent of the one million annual hospitalizations for heart failure (HF) that occur in the United States are in patients with preserved ejection fraction (EF).1 Morbidity and mortality in this population continue to be unacceptably high, inspiring renewed focus on optimizing management to improve outcomes. Unfortunately, while effective medical management for HF patients with reduced EF has a clear evidence-based approach,2 there remains limited data to guide the management of HF patients with normal EF. The few large-scale trials that have been performed have not yielded positive results, and the only data showing mortality benefit come from small less-conclusive studies.3–7 Accordingly, consensus guidelines are appropriately silent on the specific therapies that should be used when managing HF with preserved EF, and additional treatments that can improve outcomes in this challenging disease are needed.

Beta blockers (BB) have been shown to decrease death and re-hospitalization of patients with HF and reduced EF,6,8,9 and have been endorsed in both guidelines and performance measures.2 Consequently, this class of medications is an appealing, but unproven, choice for treating HF patients with preserved EF. The currently available randomized data is suggestive of benefit, but have a number of limitations making them inconclusive.7,10 Moreover, the existing observational studies have not been able to clarify this further, yielding somewhat conflicting results.5,8 Pharmacy claims data can provide a more granular estimate of medication exposure compared to typical observational cohort studies by accounting for dose, adherence, and changes over time, thus offering a new possibility to illuminate this important question. Pharmacy claims-based medication exposure estimates have demonstrated validity in a number of disease states and correlation to clinical outcomes.11–14 Specific to BB, our group has shown that claims-based medication exposure was superior to hospital discharge medication status in terms of association with heart rate as well as subsequent clinical outcomes.14 Thus, in order to attempt to clarify the possible benefit of BB in patients with HF and preserved EF, we undertook a retrospective observational study of the impact of BB exposure, quantified utilizing pharmacy claims, on outcomes in HF patients with a wide range of EFs. We compared the protective association of BB exposure, in terms of the risk of death or re-hospitalization, in HF patients with preserved EF (≥50%) to those with reduced EF (<50%), for whom BB are established therapy.

METHODS

Patient Population

Subjects were identified from patients receiving care through Henry Ford Health System and enrolled in the system health maintenance organization (HMO). We identified patients that were ≥18 years of age and were discharged from the hospital with a primary diagnosis of HF between January 1, 2000 and June 30, 2008, and who had an EF documented in the medical record. A primary hospital discharge diagnosis of HF was chosen as inclusion criteria because it has been shown by our group and others to be a highly specific (specificity 95–100%) claim signature for HF meeting the Framingham criteria.15,16 The system maintains a central repository of administrative data which was queried for this study. For patients enrolled in the HMO this data includes insurance claims information as well as enrollment and disenrollment dates. We additionally required that subjects be members of the HMO for at least one year prior to the index hospitalization, and received their care through system physicians. Therefore the study team had electronic information available for all health care visits and prescription fills within and outside of the health system. Patients were included in the analysis until one of the following events: death, re-hospitalization, disenrollment from the HMO, or end of follow up (December 31, 2008). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Data Sources

Multiple sources were used to obtain data including health system electronic administrative claims, Michigan Department of Community Health vital statistics, and the Death Master File (DMF) from the Social Security Administration (SSA). The DMF from the National Technical Information Service and the Michigan State Division of Vital Records and Health Statistics were queried using patients’ social security numbers. Claims (i.e., coded diagnoses, procedures, and prescriptions filled) for services provided both within and outside the health system were available through administrative data. The health system data warehouse also contained demographic data and laboratory tests results. Clinical test results, such as echocardiography, nuclear stress tests, and radionuclide blood pool imaging, were available through the electronic medical record and were used to ascertain whether left ventricular (LV) function showed an EF < 50% or ≥ 50%.

Pharmacy Claims and Beta Blocker Exposure Estimation

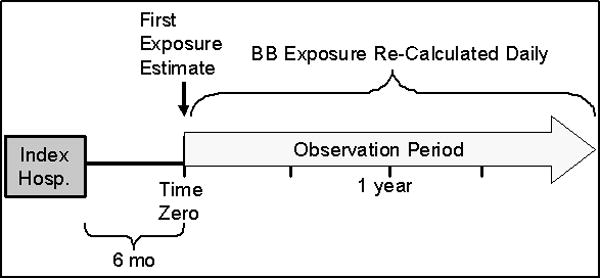

Equivalent doses of BB were defined as either the target dose for the treatment of HF or the maximum daily dose if the agent was not specifically approved for the treatment of heart failure. Specifically, the following doses were considered equivalent: bisoprolol 10mg, carvedilol 50mg, 200mg for both formulations of metoprolol, labetalol 600mg, and atenolol 100mg. BB exposure was calculated as the quantity of medication dispensed in a six-month time block multiplied by the drug-equivalent strength and divided by 180 days. Thus for each day of follow-up, every patient had an estimate of their BB exposure over preceding six months, and this exposure metric could range anywhere from 0 (no exposure) to 1 (full dose every day of period). For example, if a particular subject’s pharmacy claims indicated 12.5 mg twice daily of carvedilol and a sufficient amount of medication received for everyday of the 180 day window, the corresponding exposure estimate would be 0.5. If on the other hand this same subject only received medication sufficient for half of the days of the window, the exposure estimate would be 0.25. In this fashion the exposure estimate accounts for variability in both dose and adherence. Follow-up began at six months after the index hospital discharge date, so that all subjects would have a valid initial BB exposure estimate before outcomes would be considered. Figure 1 shows the study timeline. Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor and angiotensin-II receptor blocker (ARB) exposure was similarly calculated using estimated dose equivalency and pharmacy claims as described above.

Figure 1.

Study Schematic Timeline

Covariates

Age, gender, race, baseline atrial fibrillation, diabetes, hypertension, vascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], stroke, preexisting heart failure, serum sodium, renal dysfunction, and coronary disease were included as covariates in the multivariate models. ACE inhibitor/ARB exposure was also included to account for this treatment as a potential confounder as well as medication adherence behaviors.17 A race*BB exposure interaction term was also included as our group has recently shown that BB effectiveness may vary by race13 and since the racial distribution differed among the EF groups (i.e., <50% and ≥50%).

Patients were considered to have hypertension and/or diabetes if they had two encounters from any clinical setting with these international classification of diseases (ICD)-9 diagnostic codes OR one hospitalization with these codes as a primary discharge diagnosis in the baseline year. Individuals were also considered to have diabetes if they had at least one prescription filled for a diabetic medication in the baseline year. Baseline sodium was the first serum sodium level drawn during the index hospitalization. All other baseline co-morbidities (e.g., coronary artery disease, stroke/transient ischemic attack, end stage renal disease, and peripheral vascular disease) were defined as a primary or secondary ICD-9 diagnosis or procedure code in any setting in the year prior to the index date.

Endpoint Assessment

Time to death or hospitalization for any cause was the primary endpoint. Deaths were identified through health system administrative data, vital records from the State of Michigan, and the U.S. SSA’s DMF. The follow-up period started six months after the index hospitalization, because the medication exposure variable required 6 months of observation (Figure 1). Therefore, patients who died within six months of the index date were excluded from the analysis, and hospitalizations during this period were not considered.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were compared using chi-squared tests for categorical variables and two-sample Student’s t-tests for continuous, normally distributed variables. The nonparametric, two-sample Mann-Whitney test was used for statistical comparison of continuous variables that were not normally distributed. The association between BB exposure and the composite outcome of death or re-hospitalization was analyzed using proportional hazards regression models. Models were stratified by LV EF (i.e., EF<50 and EF≥50). The following variables were also included in the models: age, sex, race, co-existing comorbidities (i.e., diabetes, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, previous heart failure, chronic kidney disease, stroke, COPD, pulmonary vascular disease, coronary heart disease), serum sodium level, ACE inhibitor exposure, ARB exposure, a BB exposure*race interaction, BB exposure*atrial fibrillation interaction, and a BB exposure*EF interaction. Additional sub-analyses were also performed to examine 1) the effect of BB exposure on HF hospitalizations, and 2) the effect of BB agents approved for the treatment of systolic HF (i.e., carvedilol, metoprolol succinate, and bisoprolol) on the primary endpoint. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. For interactions, p values <0.1 were considered significant.18 All analyses were performed in SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

A total of 2,215 subjects were evaluated 208 and 172 were excluded from the reduced EF and preserved EF groups, respectively. These subjects were either lost to follow up or had an event in the first six month period. Therefore, 1,835 patients met inclusion criteria and made up the study cohort. Of these patients, 1,094 (59.6%) had a reduced EF (i.e., <50%) and 741 (40.4%) had a preserved EF (i.e., ≥50%). The median follow up time was 2.1 years. Patients with preserved ejection fraction were older, more likely to be women (60.6%), and less likely to be African American when compared to HF patients with reduced EF (Table 1). Overall 77% of subjects with preserved EF received BB at some point, while 85% of patients with reduced EF had at least some BB exposure, and the distribution of specific agents differed (Table 2). There were also differences between the preserved and reduced EF groups in terms of past diagnoses of diabetes, hypertension, previous HF, COPD, chronic kidney disease, and coronary artery disease. Notably, the prevalence of atrial fibrillation was similar between groups.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Variables | EF ≥50% (N=741) | EF <50% (N=1094) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ejection Fraction, % | 57.2 ±5.4 | 28.6 ±11.3 | |

| Age, years | 71.3 ±12.3 | 67.5 ±13.6 | 0.001 |

| Female | 449 (60.6%) | 451 (41.2%) | 0.001 |

| African American | 357 (48.2%) | 618 (56.5%) | 0.001 |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 221 (29.8%) | 281 (25.7%) | 0.051 |

| Diabetes | 344 (46.4%) | 443 (40.5%) | 0.012 |

| Hypertension | 544 (73.4%) | 669 (61.2%) | 0.001 |

| COPD | 289 (39.0%) | 3.14 (28.7%) | 0.001 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 105 (14.2%) | 140 (12.8%) | 0.396 |

| Cerebrovascular Accident | 112 (15.1%) | 149 (13.6%) | 0.368 |

| Previous Heart Failure | 322 (43.5%) | 545 (49.8%) | 0.007 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 94 (12.7%) | 106 (9.7%) | 0.043 |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 189 (25.5%) | 348 (31.8%) | 0.004 |

| Baseline Sodium, meq/dl | 139.6 ±4.1 | 139.6±4.1 | 0.372 |

| ACE Inhibitor/ARB Exposure | 0.26 ±0.30 | 0.26 ±0.27 | 0.049 |

| Beta Blocker Exposure | 0.24 ±0.28 | 0.24 ±0.27 | 0.198 |

TABLE 2.

Specific Beta Blocker agents used in each group.

| Beta Blocker Exposure | EF ≥50% (N=741) | EF <50% (N=1094) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| None | 23.1% (171) | 15.3% (167) |

| Indicated for HF w/Reduced EF: | ||

| Metoprolol Succinate | 2.6% (19) | 5.7% (62) |

| Carvedilol | 2.6% (19) | 20.7% (227) |

| Bisoprolol | 0.1% (1) | 0.1% (1) |

|

| ||

| Subtotal | 5.3% (39) | 26.5% (290) |

|

| ||

| Not Indicated for HF w/Reduced EF: | ||

| Metoprolol Tartrate | 42.9% (318) | 41.7% (456) |

| Atenolol | 21.1% (156) | 11.9% (130) |

| Labetalol | 5.4% (40) | 2.7% (30) |

| Propranolol | 1.8% (13) | 0.8% (9) |

| Sotalol | 0.5% (4) | 1.1% (12) |

|

| ||

| Subtotal | 71.7% (531) | 58.2% (637) |

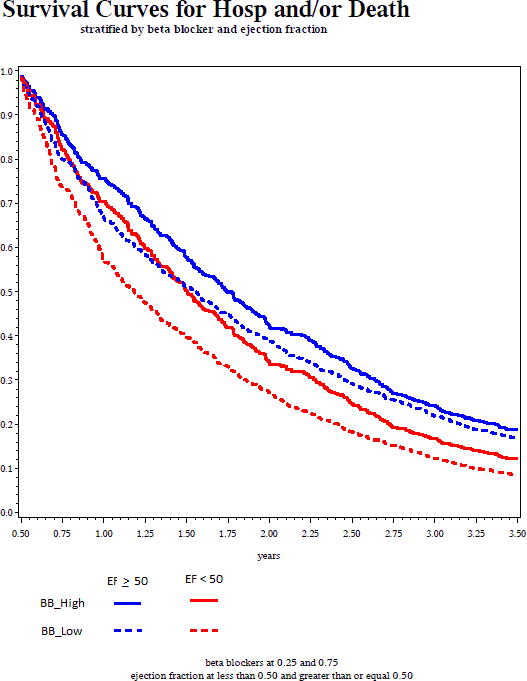

BB exposure was associated with a significantly reduced risk of death or hospitalization among those with reduced EF with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.53 (p<0.0001). Among HF patients with preserved EF, BB exposure also appeared to be protective (HR 0.68, p=0.009). Table 3 includes the fully adjusted Multivariable Cox Model. Figure 2 depicts outcome curves for each EF group (estimated from proportional hazards model) using 75th (0.48) and 25th (0.00) percentile of BB exposure. As can be seen the apparent protective association is grossly similar for both HF groups irrespective of EF. We then formally tested for an interaction between BB exposure and EF on the primary outcome, and this was not significant (β-coefficient=0.15, p=0.40 for the interaction). We also assessed the outcomes of death and hospitalization separately. Similar to above, greater BB exposure was associated with reduced risk of each of these outcomes in both groups, with HR being numerically lower in the reduced EF group though this again was not statistically dissimilar between the two EF groups (Table 4).

Table 3.

Effect of Beta Blocker Exposure on Hospital Readmission or Death Complete Multivariable Cox Model

| EF < 50% | EF ≥ 50% | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value |

| Beta Blocker | 0.53 (0.41–0.68) | 0.001 | 0.68 (0.51–0.91) | 0.009 |

| ACE/ARB | 0.47 (0.37–0.61) | 0.001 | 0.45 (0.34–0.60) | 0.001 |

| Black | 0.99 (0.86–1.14) | 0.887 | 0.92 (0.77–1.10) | 0.374 |

| Female | 0.89 (0.78–1.02) | 0.089 | 1.00 (0.85–1.18) | 0.992 |

| Age | 1.19 (1.12–1.25) | 0.001 | 1.18 (1.09–1.27) | 0.001 |

| A-Fib | 1.09 (0.93–1.28) | 0.277 | 1.11 (0.92–1.34) | 0.264 |

| Diabetes | 1.12 (0.97–1.28) | 0.115 | 1.14 (0.96–1.36) | 0.131 |

| Hypertension | 1.06 (0.91–1.24) | 0.425 | 1.00 (0.82–1.22) | 0.984 |

| PVD | 1.25 (1.02–1.52) | 0.031 | 1.37 (1.09–1.72) | 0.007 |

| CVA | 1.05 (0.87–1.26) | 0.641 | 1.15 (0.92–1.43) | 0.220 |

| Heart Failure | 1.06 (0.91–1.23) | 0.449 | 1.29 (1.07–1.55) | 0.007 |

| CKD | 1.14 (0.92–1.41) | 0.238 | 1.12 (0.88–1.42) | 0.365 |

| CHD | 1.01 (0.87–1.18) | 0.883 | 0.88 (0.72–1.07) | 0.203 |

| Sodium | 0.99 (0.97–1.00) | 0.067 | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | 0.371 |

| COPD | 1.05 (0.91–1.22) | 0.505 | 1.53 (1.29–1.83) | 0.001 |

Cerebrovascular Accident (CVA), Peripheral Vascular Disease (PVD), Chronic Kidney Disease(CKD), Coronary Heart Disease (CHD), Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

Figure 2.

Time to Death or Hospitalization (from proportional hazards regression model) showing high and low BB exposure stratified by ejection fraction group

Table 4.

Effect of Beta Blocker Exposure on Primary and Secondary Outcomes Based on Multivariable Cox Model

| Group | Outcome | EF < 50 | EF ≥ 50 | BB*EF interaction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95%CI) | P | HR (95%CI) | P | β-coeff | P | ||

| Total Cohort N=1835 |

Death or Hospitalization | 0.53 (0.41 – 0.68) | 0.001 | 0.68 (0.51 – 0.91) | 0.009 | 0.15 | 0.395 |

| Hospitalization | 0.52 (0.41 – 0.69) | 0.001 | 0.70 (0.52 – 0.94) | 0.016 | 0.19 | 0.290 | |

| Death | 0.26 (0.17 – 0.40) | 0.001 | 0.43 (0.27 – 0.68) | 0.001 | 0.25 | 0.403 | |

| HF Hospitalization | 0.53 (0.39 – 0.70) | 0.001 | 0.84 (0.60 – 1.17) | 0.306 | 0.45 | 0.030 | |

| Approved BB only* N=788 |

Death or Hospitalization | 0.51 (0.35 – 0.76) | 0.001 | 0.31 (0.12 – 0.79) | 0.014 | −0.25 | 0.591 |

Statistically significant findings in Bold typeface (p<0.05 for main effect, p<0.1 for interactions)

Age, gender, race, baseline atrial fibrillation, diabetes, hypertension, vascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], stroke, preexisting heart failure, serum sodium, renal dysfunction, coronary disease, and ACE inhibitor/ARB exposure were included as covariates in the multivariate models

We performed several secondary analyses to assess consistency and better understand our findings. First we examined the effect of BB exposure on HF-specific re-hospitalizations only. BB exposure was associated with reduced HF re-hospitalizations in the low EF group (HR 0.53, p=0.001), but not in the preserved EF group (0.84, 95%CI 0.60 1.17, p= 0.306). This difference in effect between groups did show statistical significance (p interaction=0.03). Second, since only specific BB agents have been shown in clinical trials to benefit patients with HF and low EF, we sought to determine whether our findings may have been affected by the type of BB agent used. We therefore, repeated our primary analysis excluding patients who predominantly used atenolol, metoprolol tartrate, or labetalol (i.e. agents not specifically recommended for use in HF patients with low EF). In this restricted analysis BB exposure again showed a significant benefit in both with reduced EF (HR 0.51, p=0.001) and preserved EF (HR 0.231, p=0.014) patients, with broadly similar magnitude in each group (p interaction= 0.59). An exploratory subgroup analysis by atrial fibrillation category with interaction testing was also performed and the BB effect does not appear to differ (Atrial fibrillation-BB interaction p-value 0.124 and 0.644 in the reduced EF and preserved EF groups, respectively) (see Appendix)

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective cohort, BB exposure was independently associated with improved outcomes in HF patients regardless of EF. Importantly, the beneficial association was not dissimilar in magnitude among patients with preserved EF compared to those with low EF. Although there are some conflicting results in the literature regarding benefits of BB in HF with preserved EF, our data when taken in the larger context, strongly suggest that outcomes in HF with preserved EF can be improved with BB administration.

This real-world, effectiveness study extends the findings of two randomized trials assessing the beneficial impact of BB on HF with preserved EF. The SWEDIC trial (n=113 HF with preserved EF) examined echocardiographic variables in HF with preserved EF patients randomized to BB or placebo, and found significantly more improvement in the E/A ratio in patients receiving Carvedilol.10 Improvement in this physiologic surrogate marker is consistent with BB benefit in HF with preserved EF, but the study was underpowered to assess clinical outcomes. Another randomized study, the SENIORS trial (n=2111; n=752 HF preserved EF), examined the effect of nebivolol in HF patients with preserved EF and low EF patients. There are several issues when interpreting this trial including the unique pharmacology of nebivolol, and the fact that preserved EF was defined using a relatively low cutpoint (EF>35%). None the less, there was no apparent difference between the effects of nebivolol in HF patients with preserved EF and in those with a decreased EF.7 Our data is also in agreement with previous observational studies such as the COHERE registry (n=4280; n=700 HF with preserved EF) which showed improved symptoms and decreased re-hospitalization rates in preserved EF patients after initiating carvedilol,8 and Nezverov et al (n=345 HF with preserved EF) which demonstrated a protective association in terms of death.19 Thus the preponderance of existing data, both randomized and observational, are congruous with a our findings which demonstrate a beneficial association of BB exposure on outcomes in HF patients regardless of EF.

In contrast, one previous study results conflict with the above, the OPIMIZE-HF registry (n=7154; n=4153 with preserved EF) which showed no significant decrease in mortality or re-hospitalization rates associated with BB use in HF patients with preserved EF.5 The reason(s) for this discrepancy is unclear, but could be due to misclassification of BB status or insufficient detail in terms of BB exposure. For example, OPTIMIZE assigned BB status depending on hospital discharge medication plans only, which our group has recently shown to have poor correlation with BB exposure metrics over the subsequent 6 months, as well as weak or no correlation to heart rate or outcomes.16 Furthermore, OPTIMIZE did not assess dosing or adherence, or the changes in these factors over time. Thus it would not be surprising if our approach provided a finer and more accurate assessment of drug exposure, increasing its power to detect a BB effect, which otherwise could have been missed. Indeed, the beneficial effect of BB treatment in low EF patients was much stronger in our study (HR 0.53), and more similar to BB effect in randomized trials, in contrast to that seen in OPTIMIZE (HR 0.87). Moreover, our study may differ from some previous works by requiring a hospitalization as an entry criterion, making our cohort comparatively higher risk than one made up predominantly of initially stable ambulatory patients. Inclusion of low risk subjects in such previous studies may have made any beneficial effect more difficult to detect.

It is interesting that the protective association of BB was seen in terms of death and all-cause hospitalization but not in HF-specific rehospitalization. The lack of effect on HF hospitalizations is not entirely surprising since preserved EF patients have been shown to have more frequent all-cause hospitalization and less frequent HF-specific hospital stays.20 While we are likely underpowered for this endpoint (few events and wide confidence interval), there is certainly a difference in this protective association compared to HF with reduced EF. However this does not necessarily mean that BB are without merit in this group of patients since overall outcomes appear improved. This may be an intrinsic part of this disease state; a recent meta-analysis of ACE inhibitor use in HFPEF showed improvement in mortality but no effect on HF hospitalizations.21 More broadly, these data do not allow us to speculate as to the mechanism of possible BB benefit in this population. While it did not seem to depend on preexisting atrial fibrillation, the true mechanism remains to be established. Whether this possible BB benefit is related to genetics, heart rate, arrhythmias, or hemodynamics, is unanswered and continues to be an active area of research.22–24

There are several limitations that should be considered when interpreting these data. First, as this was a retrospective, observational study, we cannot exclude all sources of confounding or selection biases (in the decision to use BB), and in fact the comparison groups differed in many ways. However, we have adjusted for many of these important factors, and as mentioned above our effect estimates in the reduced EF group appear broadly similar to those seen for BB clinical trials. Second, since the study was based primarily on administrative data there could be concerns for diagnostic misclassification. However, diagnostic misclassification in terms of HF is unlikely because we required a primary hospital discharge diagnosis of HF which has been shown to have 95%–100% specificity for patients meeting Framingham criteria for HF.15 Another concern is that we combined a variety of BB agents into one exposure metric in order to maximize power and reflect ‘real world’ treatment. Although our dose-conversions for BB agents may have been imperfect, and misclassification could bias our results to the null, this would be expected to affect the groups similarly. While the lack of heart rate data in our study is an important limitation, beta blockers have been shown to be beneficial irrespective of heart rate.24, 25 Finally, our cohort is from a single center, potentially limiting external validity, but our health system population has been shown to be representative of the larger metropolitan population.26

Conclusions

These data suggest that BB usage is associated with decreased risk of death or all-cause re-hospitalization in HF patients with preserved EF, not dissimilar to the protective association seen in those with reduced EF, for whom BB are well established and a measure of quality care. Along with past studies suggestive of benefit, this supports the need for an adequately powered, randomized clinical trial to assess the efficacy of BB in improving outcomes for HF patients with preserved EF.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

FUNDING SOURCES: This research was supported in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Lanfear K23HL085124, R01HL103871; Williams R01HL079055), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (Williams R01AI079139, R01AI061774) and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (Williams R01DK064695).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no disclosures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Yancy CW, Lopatin M, Stevenson LW, De Marco T, Fonarow GC. Clinical presentation, management, and in-hospital outcomes of patients admitted with acute decompensated heart failure with preserved systolic function: a report from the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE) Database. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al. 2009 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines Developed in Collaboration With the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:e1–e90. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farasat SM, Bolger DT, Shetty V, et al. Effect of Beta-blocker therapy on rehospitalization rates in women versus men with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:229–34. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flather MD, Shibata MC, Coats AJ, et al. Randomized trial to determine the effect of nebivolol on mortality and cardiovascular hospital admission in elderly patients with heart failure (SENIORS) Eur Heart J. 2005;26:215–25. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hernandez AF, Hammill BG, O’Connor CM, Schulman KA, Curtis LH, Fonarow GC. Clinical effectiveness of beta-blockers in heart failure: findings from the OPTIMIZE-HF (Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure) Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:184–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tamaki S, Sakata Y, Mano T, et al. Long-term beta-blocker therapy improves diastolic function even without the therapeutic effect on systolic function in patients with reduced ejection fraction. J Cardiol. 2010;56:176–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Veldhuisen DJ, Cohen-Solal A, Bohm M, et al. Beta-blockade with nebivolol in elderly heart failure patients with impaired and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: Data From SENIORS (Study of Effects of Nebivolol Intervention on Outcomes and Rehospitalization in Seniors With Heart Failure) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:2150–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Massie BM, Nelson JJ, Lukas MA, et al. Comparison of outcomes and usefulness of carvedilol across a spectrum of left ventricular ejection fractions in patients with heart failure in clinical practice. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:1263–68. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith DT, Farzaneh-Far R, Ali S, Na B, Whooley MA, Schiller NB. Relation of beta-blocker use with frequency of hospitalization for heart failure in patients with left ventricular diastolic dysfunction (from the Heart and Soul Study) Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:223–28. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.08.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergstrom A, Andersson B, Edner M, Nylander E, Persson H, Dahlstrom U. Effect of carvedilol on diastolic function in patients with diastolic heart failure and preserved systolic function. Results of the Swedish Doppler-echocardiographic study (SWEDIC) Eur J Heart Fail. 2004;6:453–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams LK, Peterson EL, Wells K, et al. Quantifying the proportion of severe asthma exacerbations attributable to inhaled corticosteroid nonadherence. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:1185–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Habib ZA, Havstad SL, Wells K, Divine G, Pladevall M, Williams LK. Thiazolidinedione use and the longitudinal risk of fractures in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:592–600. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lanfear DE, Hrobowski T, Peterson EL, et al. Association of beta blocker exposure with outcomes in heart failure differs between African American and White patients. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5:202–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.965780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lanfear DE, Peterson E, Wells K, Williams LK. Discharge medication status compares poorly with claims-based outpatient medication exposure estimates. AHA Quality of Care and Outcomes Research; Washington D.C: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alqaisi F, Williams LK, Peterson EL, Lanfear DE. Comparing methods for identifying patients with heart failure using electronic data sources. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:237. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lanfear DE, Peterson E, Wells K, Williams LK. Discharge Medication Status Compares Poorly with Claims-Based Outpatient Medication Exposure Estimates. AHA Quality of Care and Outcomes Research; Washington D. C: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Granger BB, Swedberg K, Ekman I, et al. Adherence to candesartan and placebo and outcomes in chronic heart failure in the CHARM programme: double-blind, randomised, controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2005;366:2005–11. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67760-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fleiss JL, Levin BA, Paik MC. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. 3. Hoboken, N.J: J. Wiley; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nevzorov R, Porath A, Henkin Y, Kobal SL, Jotkowitz A, Novack V. Effect of beta blocker therapy on survival of patients with heart failure and preserved systolic function following hospitalization with acute decompensated heart failure. Eur J Intern Med. 2012;23:374–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ather S, Chan W, Bozkurt B, et al. Impact of noncardiac comorbidities on morbidity and mortality in a predominantly male population with heart failure and preserved versus reduced ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:998–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.11.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fu M, Zhou J, Sun A, et al. Efficacy of ACE inhibitors in chronic heart failure with preserved ejection fraction--a meta analysis of 7 prospective clinical studies. Int J Cardiol. 2012;155:33–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.01.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pereira SB, Velloso MW, Chermont S, et al. beta-adrenergic receptor polymorphisms in susceptibility, response to treatment and prognosis in heart failure: Implication of ethnicity. Mol Med Report. 2012 doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirsh BJ, Mignatti A, Garan AR, et al. Effect of beta-Blocker Cessation on Chronotropic Incompetence and Exercise Tolerance in Patients With Advanced Heart Failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5:560–5. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.967695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cullington D, Goode KM, Clark AL, Cleland JG. Heart rate achieved or beta-blocker dose in patients with chronic heart failure: which is the better target? Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14:737–47. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fiuzat M, Wojdyla D, Kitzman D, et al. Relationship of beta-blocker dose with outcomes in ambulatory heart failure patients with systolic dysfunction: results from the HF-ACTION (Heart Failure: A Controlled Trial Investigating Outcomes of Exercise Training) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:208–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schulz A, Israel B, Williams D, Parker E, Becker A, James S. Social inequalities, stressors and self reported health status among African American and white women in the Detroit metropolitan area. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:1639–53. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00084-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.