Abstract

IL-1β is a proinflammatory cytokine that contributes to psychological stress responses and has been implicated in various psychiatric disorders most notably depression. Preclinical studies also demonstrate that IL-1β modulates anxiety- and fear-related behaviors, although these findings are difficult to assess because IL-1β infusions influence locomotor activity and nociception. Here we demonstrate that IL-1RI null mice exhibit a behavioral phenotype consistent with a decrease in anxiety-related behaviors. This includes significant effects in the elevated plus maze, light–dark, and novelty-induced hypophagia tests compared to wild-type mice, with no differences in locomotor activity. With regard to fear conditioning, IL-1RI null mice showed more freezing in auditory and contextual fear conditioning tests, and there was no effect on pain sensitivity. Taken together, the results indicate that the IL-1β/IL-1RI signaling pathway induces anxiety-related behaviors and impairs fear memory.

Keywords: IL-1β, Anxiety, Fear, IL-1RI KO mice

Proinflammatory cytokines orchestrate inflammatory and host-defense responses to infection and injury both in the periphery and the CNS [44]. These cytokines can also induce a specific behavioral complex, often referred to as sickness behavior, characterized by reduced locomotor activity, sleep disorders, and diminished social interactions, etc. [17,34]. Even though these behaviors can be of “adaptive” significance, allowing the organism to heal during infection or trauma [34], pathological consequences such as depression and anxiety can develop if these cytokines remain dysregulated [2,3,7].

In particular, interleukin (IL)-1β has been implicated in emotional disorders such as depression and anxiety [3,14]. Administration of IL-1β induces neurophysiological changes similar to those induced by physical or psychogenic stress in rats and mice, including activation of HPA axis and central noradrenergic systems [3,15], which have long been suggested to mediate anxiety [9,14]. A number of studies demonstrate that acute or chronic stress exposures induce anxiety-like behaviors in the elevated plus maze (EPM) and light/dark (LD) tests [1,11,37]. Moreover, central administration of IL-1β is reported to increase anxiety-related behaviors in the EPM [16,47]. Furthermore, contextual fear conditioning is also impaired by social isolation stress as well as exogenous administration of IL-1β, which is blocked by pretreatment with a selective IL-1β antagonist, IL-1Ra [5,42].

In the present study, we investigate the role of the IL-1β signaling pathway in anxiety-like and fearful behaviors via pharmacological administration of IL-1β in rats or genetic deletion of IL-1RI in mice. In particular, we assessed a wide spectrum of behaviors using mice with a null mutation for the IL-1 type I receptor (IL-1RI KO), the primary receptor for IL-1β in the brain, to exclude the problematic effects of IL-1β infusions on overall locomotor activity [16,47] and alterations in pain sensitivity [51].

Adult male Sprague–Dawley rats (Charles River Labs, Wilmington, MA) with initial weights of 230–250 g and adult male IL-1RI KO mice on a C57BL/6 background (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) with initial weights of 23–30 g were used for experiments. The IL-1RI KO mice exhibit no overt phenotype, breed well, and have normal litter size [28]. For the KO mice, age and weight-matched C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Laboratory) were used as wild-type (WT) controls. Animals were housed, three per cage, under standard illumination parameters (12 h light/dark cycle) and with ad libitum access to food and water. All procedures were in accordance with Yale Animal Care and Use Committee and National Institutes of Health guidelines for animal research.

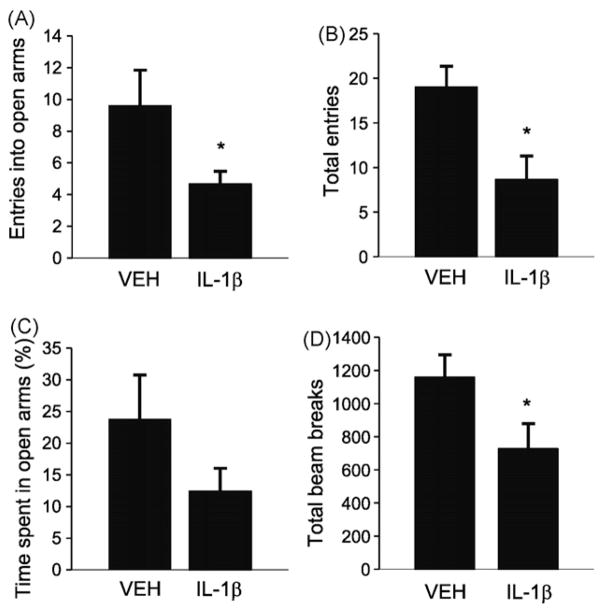

The influence of IL-1β on behavior in rats was determined by infusions of IL-1β (R&D Systems; 20 ng/μl/rat) or vehicle (0.1% BSA/PBS) into the lateral ventricle (from bregma: AP, −0.9; ML, ±1.5; DV, −3.0 mm) as previously described [33]. Thirty minutes after infusions, locomotor activity, defined as consecutive beam breaks, was measured in the automated activity chambers (25 cm × 45 cm × 20 cm; Digiscan animal activity monitor; Omnitech Electronics, Columbus, OH) for 1 h. During the first and the second 10 min blocks, IL-1β infused rats showed a tendency (t6 = 1.959, n = 4, P < 0.1) and significant decrease (t6 = 3.471, P < 0.05), respectively, in locomotor activity, as well as a significant difference in general locomotor activity over the 60 min time period (t6 = 2.537, P < 0.05) (Fig. 1D). Over the last 40 min there was no difference (t6 = 0.508, P = n.s.).

Fig. 1.

Influence of IL-1β or vehicle (VEH) on elevated plus maze and locomotor activity. (A) IL-1β infused rats showed a reduction in number of entries to open arms (t9 = 2.563, P < 0.05; n = 5–6 per group) and (B) to total arms (t9 = 2.892, P < 0.05). (C) There was a tendency for a decrease in total time spent in open arms (t9 = 1.523, P < 0.1). (D) IL-1β infusion decreased general locomotor activity over 60 min time period. *P < 0.05 compared to VEH rats in the t-test, mean ± S.E.M.

Two hours after infusions, the EPM test was performed as previously described in rats [16,50]. We chose a delay of 120 min based on previous behavioral data from social exploration and sweetened milk drinking in mice [6,48], and a significant increase in the IL-1β concentration in the rat dentate gyrus ~80 min after IL-1β central administration [38]. IL-1β infused rats exhibited a significant reduction in number of open arm entries (Fig. 1A) as well as number of total arm entries (Fig. 1B). There was a tendency for a reduction in the time spent in open arms (Fig. 1C).

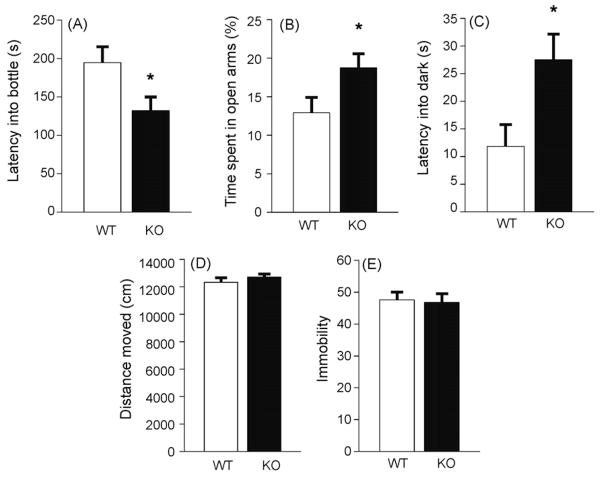

Because of the possible non-specific effects of IL-1β to decrease overall activity in rats, we next tested IL-1RI deletion mutant mice in three different anxiety tests, novelty-induced hypophagia (NIH), EPM, and LD. For NIH, mice were singly housed for several days before the start of training. For habituation, on three consecutive days mice were presented with diluted (1:3 = milk:water) sweetened condensed milk (Carnation) for 30 min. Homecage testing was done on day 4 under dim lighting (~50 lx) by replacing the water bottle with the milk bottle for 30 min and the latency to drink was recorded. Novel cage testing occurred on day 5, when mice were placed into new clean cages of the same dimensions (without bedding) under bright lighting (approx. 1000 lx) and with white paper placed under cages to enhance aversiveness. Overnight water consumption was also determined (16 h). Experimental data were analyzed statistically using unpaired t-test. In the novel cage, IL-1RI KO mice exhibited significantly reduced latency to drink relative to WT mice (Fig. 2A). In contrast, there was no difference between WT and IL-1RI KO mice in latency to drink milk in the homecage (t28 = 1.306, P = n.s.).

Fig. 2.

Anxiety-like behaviors in IL-1RI KO mice. (A) IL-1RI KO mice showed a reduced latency to drink in the novelty-induced hypophagia test (t28 = 2.252, P < 0.05; n = 14–16 per group), (B) spent less time in open arms in the elevated plus maze (t14 = 2.172, P < 0.05; n = 8 per group), and (C) took less time to first enter into dark chamber in the light/dark box test (t14 = 2.567, P < 0.05; n = 8 per group) than WT mice. (D and E) However, there is no difference in the homecage locomotor activity (D) (t13 = 0.341, P = n.s.; n = 7–8 per group) or immobility in the forced swim test (E) (t11 = 0.226, P = n.s.; n = 6–7 per group) between IL-1RI KO and WT mice. *P < 0.05 compared to WT mice in the t-test, mean ± S.E.M.

The EPM test was conducted in IL-1RI KO mice for 10 min according to published procedures using the EthoVision Video Tracking System [35,45]. There was no difference in the number of open arm entries (t14 = 1.644, P = n.s.). However, IL-1RI KO mice exhibited a significant increase in the percent time spent in the open arms compared with WT mice (Fig. 2B). There was no difference in total distance moved in the EPM (t14 = 0.391, P = n.s.). Mice were also tested individually for general locomotor activity in cages with homecage bedding under dim lighting conditions (Noldus Information Technology, Leesburg, Virginia). There was no difference in total distance moved over a 10-min period between WT and IL-1RI KO mice (Fig. 2D).

The LD test is performed in bright light (approx. 1000 lx) and is considered a measure of anxiety-like behaviors under stressful conditions [45]. The latency to first enter into the dark compartment and the time spent in the light compartment were measured [26]. Although no significant genotype effects were noted in time spent in the light compartment (t14 = 0.406, P = n.s.), there is a significant difference in the latency to first enter the dark compartment (Fig. 2C).

The IL-1RI deletion mutants were also assessed in the Porsolt forced swim test (FST), a measure of despair-like behaviors that is reversed by antidepressant treatment [41]. The FST was performed according to published procedures [41,45] with minor modifications. We used a 2-day forced-swim procedure, with a 10-min swim session on day 1 followed by a 6-min swim session 24 h later. The 6 min test was videotaped, and the time spent immobile during the last 5 min was recorded. Immobility was defined as a lack of movement or minimal amount necessary to keep the head above water. There was no change in immobility between WT and IL-1RI KO mice (Fig. 2E).

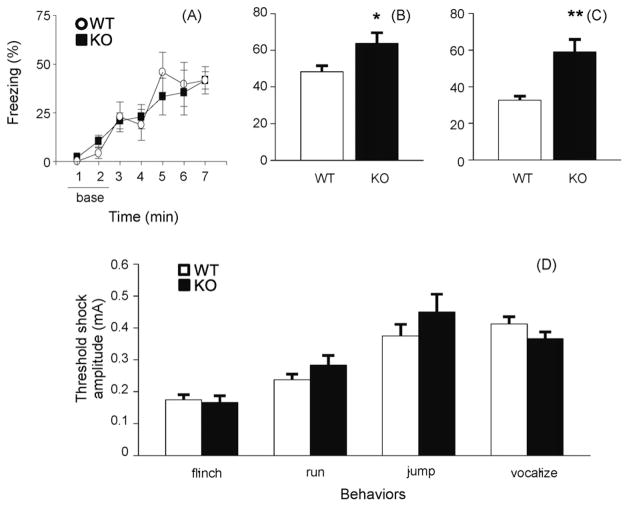

Fear conditioning was carried out according to published methods [8,45] to determine the involvement of IL-1RI in fear memory. Mice received three pairings of a 30-s tone with a foot shock (0.4 mA) (separated by 2 min), delivered during the last 2 s of the tone. Mice were tested for contextual conditioning 24 h later in the same conditioning chamber (5 min). Two to three hours later, mice were tested for cued conditioning in a clear plastic cage. Movements were videotaped before (altered context test, 3 min) and during presentation of the tone (cued conditioning test, 3 min). Freezing [24] was scored every 10 s. During the training phase, the freezing behavior of IL-1RI KO mice was not different from that of WT control mice (Fig. 3A). In the contextual test, the freezing response (%) was significantly increased in IL-1RI KO mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 3B). In the tone cued test, increased freezing was also observed in IL-1RI KO mice at the onset of the tone as compared with WT mice (Fig. 3C). There was no difference in freezing prior to the tone between WT and IL-1RI KO mice (baseline, t14 = 0.357, P = n.s.).

Fig. 3.

Fear conditioning in IL-1RI KO mice. (A) There was no difference in mean percentage of freezing during the intervening three tone-shock pairings of the 2 min ITI (F1,14 = 0.137, P = n.s.; n = 8 per group). (B and C) IL-1RI KO mice showed more freezing during 5 min contextual testing (B, t14 = 2.298, P < 0.05) and during 3 min tone-cued testing (C, t14 = 3.691, P < 0.01) than WT mice. (D) There was no difference in shock sensitivity for each response of flinch, jump, run, and sonic vocalization between WT and IL-1RI KO mice (flinch, t12 = 0.318; jump, t12 = 1.355; run, t12 = 1.167; and vocalization t12 = 1.433, all Ps = n.s.). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared to WT mice in the t-test, mean ± S.E.M.

Shock sensitivity was assessed by placing each mouse in the conditioning chamber and giving a series of footshocks for 2 s at 10 s intervals. Shock intensity began at 0.25 mA and was increased by 0.25 mA increments until the mouse exhibited an unconditioned reaction (e.g., flinch, run, jump, and vocalization) [8]. There was no difference in shock sensitivity between WT and IL-1RI KO mice in each behavior (Fig. 3D).

IL-1β in rats decreases ambulatory activity during the immediate time period after infusions, but not at later points. This decrease could reflect an anxiogenic action of IL-1β in a novel chamber environment, but could also be related to more general effects on locomotor activity. The use of IL-1RI KO mice was critical to exclude the latter possibility of non-specific effects of IL-1β on overall activity, which is not seen in the null mutant mice.

The NIH test has validity as a model of anxiety that is responsive to chronic, but not acute antidepressant treatment [20]. In the present study, genetic deletion of IL-1RI decreased the latency to drink sweetened milk in the novel cage but not in the homecage, which indicates an anxiolytic effect in IL-1RI deletion mutants and is consistent with the hypothesis that IL-1β increases anxiety. Consistent with the NIH data, IL-1RI KO mice also displayed reduced anxiety-like behaviors in the EPM and LD. Both are models of anxiety based on the conflict between spontaneous exploratory behavior and the aversion to potential dangers [29,30]. Previous studies report that central administration of IL-1β or LPS decreases open arm entries and the time spent in the open arms in the EPM. However, entries to all arms were also reduced, indicating a decrease in general activity. Similar effects were observed in the current study, and indicate that behavioral responses to IL-1β and LPS reflect a reduction in overall locomotor activity [16,47]. The reduced anxiety-like behaviors exhibited by the IL-1RI KO mice in the EPM and LD tests, without altered locomotor activity, provide further evidence that IL-1β/IL-1RI activation contributes significantly to stress-induced anxiety-like behaviors.

We also examined the involvement of IL-1RI in despair-like behaviors by assessing the IL-1RI KO mice in the FST. Antidepressants decrease immobility in the FST after even a single dose, despite the fact that the clinical effects of antidepressants require administration for several weeks or months [21,39]. Previous studies report that IL-1β infusion or LPS administration increase immobility [19,22]. However, the impairment of locomotor activity resulting from IL-1β could be responsible for the increase in immobility in the FST [22]. Based on the IL-1β-reduction in locomotor activity and our data demonstrating that IL-1RI KO mice show no change in immobility in the FST or in locomotor activity, the results indicate that IL-1β/IL-1RI activation is not involved in responses in the FST.

The role of IL-1RI signaling in a Pavlovian fear-conditioning paradigm in which foot shocks are paired with a tone cue in a specific context was also examined [31,40]. Fear conditioning has long been considered a central pathogenic mechanism in anxiety disorders [18]. During the training stage, there was no difference in freezing between IL-1RI KO and WT mice, suggesting that IL-1RI is not involved in acquisition of fear. In both auditory and contextual testing, IL-1RI KO mice displayed more freezing than WT mice, indicating that IL-1RI signaling may directly enhance fear memory. IL-1β (i.c.v. infusion) is reported to impair contextual but not auditory fear conditioning in rats [42], suggesting a more specific role and one that is mediated by the hippocampus, which is required for contextual conditioning [31,40]. This is consistent with the fact that IL-1β has long been implicated as a negative regulator of hippocampal dependent learning and memory [27,38] with some exceptions [4,52]. The discrepancy in fear conditioning may be explained by differences in strain, availability of IL-1β in specific brain regions (e.g., hippocampus, but not amygdala), and/or experimental protocols. Increased auditory fear conditioning in the IL-1RI KO mice suggests that amygdala is also involved since this region is necessary for both auditory cued and contextual fear conditioning [25] and is one of brain areas expressing IL-1RI [23].

The mechanisms underlying the behavioral actions of IL-1β/IL-1RI, remain unclear but could involve regulation of other factors. For example, brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is regulated by IL-1β and has been implicated in anxiety and fear conditioning. Infusions of IL-1β, like stress, decrease BDNF expression in the hippocampus [5]. Mutant mice with a polymorphism of the BDNF gene (Val66Met), which reduces the processing and release of BDNF, show increased anxiety-related behaviors in EPM, NIH, and open field tests [10]. In contrast, intrahippocampal administration of BDNF in rats reduces anxious behaviors in the EPM, suggesting that hippocampal BDNF may be critical for anxiety [13]. In particular, there are some reports showing that lesions of ventral hippocampus, but not dorsal hippocampus or amygdala, impair the induction of anxious behaviors [32,49]. With regard to fear conditioning, IL-1β or stress decreases the expression of BDNF in the amygdala [12,46], which is required for fear conditioning [36,43]. The possibility that altered BDNF expression contributes to the actions of IL-1β/IL-1RI on these behaviors will require further testing, including pharmacological and/or genetic inactivation of IL-1RI or BDNF in specific brain regions (e.g., ventral hippocampus or amygdala subregions).

Previously, we reported that chronic unpredictable stress decreases sucrose consumption in WT mice, which is blocked in IL-1RI KO mice [33]. Taken together with our previous work, the current data suggest that the IL-1β/IL-1RI pathway plays a critical role in anxiety and fear memory. Moreover, the results suggest that the IL-1β signaling system is involved in a broad range of depressive symptoms, albeit not all behaviors (i.e., FST) and provide further evidence that pharmacological inhibition of this system may represent an alternative strategy for the clinical management of anxiety as well as depression.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. J. Taylor for her kind comments and for the use of locomotor activity boxes. This work is supported by USPHS grants MH45481 and 2 PO1 MH25642, a Veterans Administration National Center Grant for PTSD, and by the Connecticut Mental Health Center.

References

- 1.Andreatini R, Bacellar LF. The relationship between anxiety and depression in animal models: a study using the forced swimming test and elevated plus-maze. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1999;32:1121–1126. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x1999000900011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anisman H, Hayley S, Turrin N, Merali Z. Cytokines as a stressor: implications for depressive illness. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002;5:357–373. doi: 10.1017/S1461145702003097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anisman H, Merali Z. Anhedonic and anxiogenic effects of cytokine exposure. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;461:199–233. doi: 10.1007/978-0-585-37970-8_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avital A, Goshen I, Kamsler A, Segal M, Iverfeldt K, Richter-Levin G, Yirmiya R. Impaired interleukin-1 signaling is associated with deficits in hippocampal memory processes and neural plasticity. Hippocampus. 2003;13:826–834. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barrientos RM, Sprunger DB, Campeau S, Higgins EA, Watkins LR, Rudy JW, Maier SF. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA downregulation produced by social isolation is blocked by intrahippocampal interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. Neuroscience. 2003;121:847–853. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00564-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bluthé RM, Pawlowski M, Suarez S, Parnet P, Pittman Q, Kelley KW, Dantzer R. Synergy between tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-1 in the induction of sickness behavior in mice. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1994;19:197–207. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(94)90009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonaccorso S, Maier SF, Meltzer HY, Maes M. Behavioral changes in rats after acute, chronic and repeated administration of interleukin-1beta: relevance for affective disorders. J Affect Disord. 2003;77:143–148. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00118-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caldarone BJ, Duman CH, Picciotto MR. Fear conditioning and latent inhibition in mice lacking the high affinity subclass of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the brain. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:2779–2784. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00137-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charney DS, Grillon C, Bremner JD. The neurobiological basis of anxiety and fear: circuits, mechanisms, and neurochemical interactions (part I) Neuroscientist. 1998;4:35–44. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen ZY, Jing D, Bath KG, Ieraci A, Khan T, Siao CJ, Herrera DG, Toth M, Yang C, McEwen BS, Hempstead BL, Lee FS. Genetic variant BDNF (Val66Met) polymorphism alters anxiety-related behavior. Science. 2006;314:140–143. doi: 10.1126/science.1129663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chotiwat C, Harris RB. Increased anxiety-like behavior during the post-stress period in mice exposed to repeated restraint stress. Horm Behav. 2006;50:489–495. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Churchill L, Taishi P, Wang M, Brandt J, Cearley C, Rehman A, Krueger JM. Brain distribution of cytokine mRNA induced by systemic administration of interleukin-1beta or tumor necrosis factor alpha. Brain Res. 2006;1120:64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.08.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cirulli F, Berry A, Chiarotti F, Alleva E. Intrahippocampal administration of BDNF in adult rats affects short-term behavioral plasticity in the Morris water maze and performance in the elevated plus-maze. Hippocampus. 2004;14:802–807. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clement Y, Chapouthier G. Biological bases of anxiety. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1998;22:623–633. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(97)00058-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Connor TJ, Song C, Leonard BE, Merali Z, Anisman H. An assessment of the effects of central interleukin-1β, -2, -6, and tumor necrosis factor-α administration on some behavioural, neurochemical, endocrine and immune parameters in the rat. Neuroscience. 1998;84:923–933. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00533-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cragnolini AB, Schiöth HB, Scimonelli TN. Anxiety-like behavior induced by IL-1β is modulated by α-MSH through central melanocortin-4 receptors. Peptides. 2006;27:1451–1456. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dantzer R. Cytokine-induced sickness behavior: mechanisms and implications. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;933:222–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis M. Animal models of anxiety based on classical conditioning: the conditioned emotional response (CER) and the fear-potentiated startle effect. Pharmacol Ther. 1990;47:147–165. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(90)90084-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.del Cerro S, Borrell J. Interleukin-1 affects the behavioural despair response in rats by an indirect mechanism which requires endogenous CRF. Brain Res. 1990;528:162–164. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90212-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dulawa SC, Hen R. Recent advances in animal models of chronic antidepressant effects: the novelty-induced hypophagia test. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29:771–783. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duman RS. Depression: a case of neuronal life and death? Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:140–145. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunn AJ, Swiergiel AH. Effects of interleukin-1 and endotoxin in the forced swim and tail suspension tests in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;81:688–693. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ericsson A, Liu C, Hart RP, Sawchenko PE. Type 1 interleukin-1 receptor in the rat brain: distribution, regulation, and relationship to sites of IL-1-induced cellular activation. J Comp Neurol. 1995;361:681–698. doi: 10.1002/cne.903610410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fanselow MS. Conditioned and unconditional components of post-shock freezing. Pavlov J Biol Sci. 1980;15:177–182. doi: 10.1007/BF03001163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fanselow MS, LeDoux JE. Why we think plasticity underlying Pavlovian fear conditioning occurs in the basolateral amygdala. Neuron. 1999;23:229–232. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80775-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fukui M, Rodriguiz RM, Zhou J, Jiang SX, Phillips LE, Caron MG, Wetsel WC. Vmat2 heterozygous mutant mice display a depressive-like phenotype. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10520–10529. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4388-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gibertini M, Newton C, Klein TW, Friedman H. Legionella pneumophila-induced visual learning impairment reversed by anti-interleukin-1β. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1995;210:7–11. doi: 10.3181/00379727-210-43917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glaccum MB, Stocking KL, Charrier K, Smith JL, Willis CR, Maliszewski C, Livingston DJ, Peschon JJ, Morrissey PJ. Phenotypic and functional characterization of mice that lack the type I receptor for IL-1. J Immunol. 1997;159:3364–3371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hascoet M, Bourin M, Dhonnchadha BAN. The mouse light–dark paradigm: a review. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2001;25:141–166. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(00)00151-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hogg S. A review of the validity and variability of the elevated plus-maze as an animal model of anxiety. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1996;54:21–30. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)02126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim JJ, Fanselow MS. Modality specific retrograde amnesia of fear. Science. 1992;256:675–677. doi: 10.1126/science.1585183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kjelstrup KG, Tuvnes FA, Steffenach HA, Murison R, Moser EI, Moser MB. Reduced fear expression after lesions of the ventral hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:10825–10830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152112399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koo J, Duman RS. IL-1β is an essential mediator of the antineurogenic and anhedonic effects of stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:751–756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708092105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kronfol Z, Remick DG. Cytokines and the brain: implications for clinical psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:683–694. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lister RG. The use of a plus-maze to measure anxiety in the mouse. Psychophar-macology (Berl) 1987;92:180–185. doi: 10.1007/BF00177912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu IY, Lyons WE, Mamounas LA, Thompson RF. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor plays a critical role in contextual fear conditioning. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7958–7963. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1948-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.MacNeil G, Sela Y, McIntosh J, Zacharko RM. Anxiogenic behavior in the light–dark paradigm following intraventricular administration of cholecystokinin-8S, restraint stress, or uncontrollable footshock in the CD-1 mouse. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1997;58:737–746. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(97)00037-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murray CA, Lynch MA. Evidence that increased hippocampal expression of the cytokine interleukin-1β is a common trigger for age- and stress-induced impairments in long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2974–2981. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-08-02974.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nestler EJ, Gould E, Manji H, Buncan M, Duman RS, Greshenfeld HK, Hen R, Koester S, Lederhendler I, Meaney M, Robbins T, Winsky L, Zalcman S. Preclinical models: status of basic research in depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:503–528. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01405-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Phillips RG, LeDoux JE. Differential contribution of amygdala and hippocampus to cued and contextual fear conditioning. Behav Neurosci. 1992;106:274–285. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.106.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Porsolt RD, Anton G, Blavet N, Jalfre M. Behavioural despair in rats: a new model sensitive to antidepressant treatments. Eur J Pharmacol. 1978;47:379–391. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(78)90118-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pugh CR, Nguyen KT, Gonyea JL, Fleshner M, Wakins LR, Maier SF, Rudy JW. Role of interleukin-1β in impairment of contextual fear conditioning caused by social isolation. Behav Brain Res. 1999;106:109–118. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(99)00098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rattiner LM, Davis M, French CT, Ressler KJ. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and tyrosine kinase receptor B involvement in amygdala-dependent fear conditioning. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4796–4806. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5654-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rothwell NJ, Luheshi GN. Interleukin 1 in the brain: biology, pathology and therapeutic target. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:618–625. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01661-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Simen BB, Duman CH, Simen AA, Duman RS. TNFalpha signaling in depression and anxiety: behavioral consequences of individual receptor targeting. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:775–785. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith MA, Makino S, Kim SY, Kvetnansky R. Stress increases brain-derived neurotropic factor messenger ribonucleic acid in the hypothalamus and pituitary. Endocrinology. 1995;136:3743–3750. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.9.7649080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Swiergiel AH, Dunn AJ. Effects of interleukin-1β and lipopolysaccharide on behavior of mice in the elevated plus-maze and open field tests. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;86:651–659. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Swiergiel AH, Smagin GN, Dunn AJ. Influenza virus infection of mice induces anorexia: comparison with endotoxin and interleukin-1 and the effects of indomethacin. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1997;57:389–396. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(96)00335-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Trivedi MA, Coover GD. Lesions of the ventral hippocampus, but not the dorsal hippocampus, impair conditioned fear expression and inhibitory avoidance on the elevated T-maze. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2004;81:172–184. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wallace TL, Stellitano KE, Neve RL, Duman RS. Effects of cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element binding protein overexpression in the basolateral amygdala on behavioral models of depression and anxiety. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:151–160. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Watkins LR, Wiertelak EP, Goehler LE, Smith KP, Martin D, Maier SF. Characterization of cytokine-induced hyperalgesia. Brain Res. 1994;654:15–26. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91566-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yirmiya R, Winocur G, Goshen I. Brain interleukin-1 (IL-1) is involved in spatial memory and passive avoidance conditioning. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2002;78:379–389. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2002.4072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]