Abstract

The objective of this study was to measure the correlation between compulsive sexual behavior (CSB) and internalized homonegativity (IH) and determine their association with unprotected anal intercourse in Latino men who have sex with men. Nine hundred sixty-three Latino men completed an Internet survey (MINTS study) in 2002 and provided data on two scale exposures. Logistic regression was used to test interactions and generate effect estimates. Higher IH and association with gay organizations modified the effect of CSB on high-risk sex. Drug and alcohol use also contributed to risk behavior for this subgroup. Overall, CSB had a strong association with high-risk sex. IH and gay organization membership may moderate this relationship, which illuminates an additional factor to consider in studying sexual risk-taking. Further work is needed to validate a path from IH and high-risk sex that incorporates drug or alcohol use.

Keywords: sexual compulsivity, homonegativity, Latino, men who have sex with men, condom use

Introduction

Transmission rates of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections as well as rates of unprotected intercourse are increasing among men who have sex with men (del Romero et al., 2001; Hogg et al., 2001; Wolitski, Valdiserri, Denning, & Levine, 2001). According to CDC estimates from the 2004 HIV surveillance period, Hispanic men are contracting HIV at three times the rate of non-Hispanic White men (CDCP, 2005). For Hispanic men, other than Puerto Ricans, sex with other men is the most prevalent risk factor identified.

Among Hispanic or Latino men who have sex with men, perceptions of stigma based on ethnicity and sexual orientation contribute to risk behavior, which includes substance use and unprotected intercourse (Diaz, Ayala & Bein, 2004). Stigma of this nature is implicated in the development of shame about one's identity (Diaz et al., 2004). Among men who have sex with men, one manifestation of shame is internalized homonegativity (IH) (Ross & Rosser, 1996), and shame may lead to the development of a maladaptive form of coping, such as compulsive sexual behavior (CSB) (Coleman, 1987; Kalichman & Cain, 2004). Furthering the understanding of how these constructs are related to one another and to high-risk behavior among Latino men who have sex with men can help advance health promotion activities.

As defined by Kalichman and Cain (2004), CSB can be described as “a propensity to experience sexual disinhibition and undercontrolled sexual impulses and behaviors as self-identified by individuals” (p. 235). Finlayson, Sealy, and Martin (2001) operationalized CSB by specifying the need for obtrusive sexual thoughts, uncontrolled sexual behaviors, and the continuing of sexual behaviors in spite of negative consequences. Although not clearly endorsed by all researchers in the field (Gold & Heffner, 1998; Goodman, 2001), CSB has been linked empirically to elevated numbers of acts of unprotected anal intercourse and higher numbers of sexual partners among men who have sex with men (Benotsch, Kalichman, & Pinkerton, 2001; Kalichman, Greenberg, & Abel, 1997; Kalichman & Rompa, 1995).

Ross and Rosser (1996) defined IH as the incorporation of the negative societal views of homosexuality into the person. Similar to CSB, IH has been linked to higher rates of unprotected intercourse (Ratti, Bakeman, & Peterson, 2000) or a heightened desire for “anonymous” partners (Ross & Rosser, 1996). IH, not degree of homosexuality, appears related to a cluster of negative mental and sexual health outcomes, potentially explaining health disparities between men who have sex with men and the general population (Rosser et al., 2008a, in press).

To date, no studies have examined the relationship between CSB and IH. The first objective of this study was the examination of the correlation between two scales: the Compulsive Sexual Behavior Inventory (Coleman, Miner, Ohlerking, & Raymond, 2001) and Reactions Toward Homosexuality (Ross & Rosser, 1996) nested within an Internet-based survey of Latino men who have sex with men. The second objective was to estimate the association between each behavioral construct and high-risk sex, defined as two or more unprotected sexual partners in the three months prior to the survey.

Methods

The sample

Self-identified Latino men who have sex with men were recruited to participate in an online survey, The Men's Internet Study (MINTS), between November and December, 2002. A detailed summary of data collection methods is published elsewhere (Rosser et al., 2008b, in press). In brief, participants were invited to the study through banner advertisements placed on the Gay.com website (Gay.com). Inclusion criteria included an age of at least 18 years, identification as a biological male and Latino, and a report of at least one sexual encounter with another male. The survey could be completed in either English or Spanish. During data collection, 1563 men qualified to participate in the survey, and 1026 completed the questionnaire. Of these, 963 responded to each question for both scale measurements and were included in this analysis. The primary data collection was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Minnesota. This analysis was approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Statistical methods

Age, ethnic identity, race, years of education, annual income, drug or alcohol use during the last sexual encounter, acculturation and formal membership in a gay organization comprised the demographic variables for the study. All variables were analyzed directly as asked in the questionnaire with the exception of acculturation and race. Acculturation was measured as a continuous, composite variable of the responses to four questions in the survey relating to language use (English or Spanish) with friends and in the home, and language in which the respondent thought. The scale range was from 4 to 20, with a higher score indicating more use of the English language. For race, respondents were asked to categorize themselves as American Indian, Asian American, Black, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, White, or Other. Considering the small numbers reported for the first four categories (28, 6, 15 and 3, respectively), and the number reporting multiple identities, the variable was dichotomized to reflect identification as White or Non-White.

The first aim of the investigation was to determine the correlation between two behavior scales. For the sexual compulsivity scale, 28 questions measured as 5-point Likert responses (1=very frequently, 5=never) were combined to create a single measure. Using the same technique, a composite score was created for the 26, 7-point Likert items that comprised the IH scale (1=strongly disagree, 7=strongly agree) after reverse scoring of particular questions. The Cronbach's α coefficient measured reliability for both scales, and the Pearson correlation coefficient served as the statistical test for their association. The significance level was set at p<0.05.

The second aim of the study was to estimate the association between the behavioral constructs and high-risk sex. Participants were asked to report the number of men with whom they had had sex with without a condom in the three months before the survey. Respondents were to include a committed partner in the total number. The definition of high-risk sex as two or more unprotected sexual partners was used to exclude those taking a negotiated risk with a committed partner. We used logistic regression to adjust for confounding variables and assess for effect measure modification (Hosmer & Lemeshow, 2000). Both of the scale measures were dichotomized at their medians since there are currently not cut points available to facilitate the interpretation of a lower and higher exposure level.

Model building

All variables that reached a preliminary significance of p<0.25 in univariable analysis were included in the multivariable regression. Those variables that reached the more traditional significance of p<0.05 were retained in the final analysis. In addition, variables that modified the association between the main exposures and high-risk sex more than 10% were included, irrespective of statistical significance. All analyses were conducted in STATA Version 9 (StataCorp, 2005).

Results

The demographic characteristics of the sample (Table 1) show that the participants included in the analysis were highly educated and indicate a preference for communication in English. Comparison between included participants and those excluded for not completing the survey or not providing exposure information demonstrated that participants in the analysis are older (Mean=28.2 years, SD=7.8 versus 25.8 years, SD=5.25, p<0.001) and more likely to have used drugs or alcohol at their last sexual encounter (27.5% versus 16.9%, p<0.001). The Latino ethnic background reflected the Latino population distribution of the USA (Rosser et al., 2008b, in press).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of 963 included participants.

| Variable | Distribution |

|---|---|

| Age (years) (N=953) | |

| Mean, SDa | 28.2, 7.8 |

| Acculturation, scale total (N=960) | |

| Mean, SDa | 15.7, 3.7 |

| Education, years (%) | |

| ≤8 | 5.6 |

| 9–12 | 14.5 |

| ≥13 | 77.7 |

| Missing | 2.2 |

| Annual income (%) | |

| ≤$21,000 | 27.0 |

| $21,001–$38,000 | 26.8 |

| >$38,000 | 26.2 |

| Missing | 20.0 |

| Race (%) | |

| White | 25.4 |

| Non-White | 52.4 |

| Missing | 22.2 |

| Ethnicity (%) | |

| Mexican | 52.4 |

| Puerto Rican | 19.1 |

| Cuban | 1.6 |

| Other | 25.4 |

| Missing | 1.6 |

| Gay organization membership (%) | |

| No | 61.1 |

| Yes | 38.7 |

| Missing | 0.2 |

| Compulsive Sexual Behavior Inventory | |

| Median, IQRb | 53, 20 |

| Reactions to homosexuality | |

| Median, IQRb | 96, 33 |

Standard deviation.

Inter-quartile range.

The correlation analysis between the composite measures of compulsive sexual behavior and IH demonstrated a statistically significant, positive correlation between the two constructs (Pearson's r=0.286, p<0.001). Reliability for the Compulsive Sexual Behavior Inventory was high in this sample (Cronbach's α=0.91). The Reactions to Homosexuality scale reliability estimate was not as strong, but still representative of appropriate construct measurement (Cronbach's α=0.83).

From the univariable analyses, CSB, IH, age, acculturation, drug or alcohol use at the last sexual encounter, annual income, and gay organization membership all reached preliminary significance (p<0.25) for inclusion in a multivariable logistic regression analysis (Table 2). CSB was associated with an increased likelihood of high-risk sex, while IH had a modest protective effect.

Table 2.

Results from single and multivariable logistic regression analyses on the outcome of high-risk sex.

| Univariable PORa (95% CI) | Multivariable PORa,b (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.02 (1.00, 1.04) | 1.03 (1.01, 1.05) |

| Acculturation | 1.07 (1.03, 1.11) | 1.07 (1.02, 1.12) |

| Education | ||

| ≤8 | 1 (Referent) | |

| 9–12 | 1.11 (0.56, 2.24) | |

| ≥13 | 0.99 (0.53, 1.83) | |

| Annual income | ||

| ≤$21,000 | 1 (Referent) | |

| $21,001–$38,000 | 1.41 (0.96, 2.08) | |

| >$38,000 | 1.60 (1.08, 2.35) | |

| Race | ||

| White | 1 (Referent) | |

| Non-White | 1.20 (0.87, 1.65) | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Mexican | 1 (Referent) | |

| Cuban | 1.11 (0.74, 1.69) | |

| Puerto Rican | 0.87 (0.44, 1.72) | |

| Other | 0.85 (0.59, 1.20) | |

| Drug or alcohol use at last sexual encounter | ||

| No | 1 (Referent) | 1 (Referent) |

| Yes | 1.93 (1.42, 2.61) | 1.80 (1.31, 2.49) |

| Gay organization membership | ||

| No | 1 (Referent) | 1 (Referent) |

| Yes | 1.54 (1.15, 2.04) | 1.34 (0.98, 1.84) |

| Compulsive Sexual Behavior Inventoryc | ||

| Lower half | 1 (Referent) | 1 (Referent) |

| Upper half | 2.58 (1.92, 3.47) | 2.81 (2.03, 3.87) |

| Reactions to homosexualityc | ||

| Lower half | 1 (Referent) | 1 (Referent) |

| Upper half | 0.82 (0.62, 1.09) | 0.72 (0.52, 1.01) |

POR = prevalence odds ratio.

Adjusted for all variables listed in the regression.

Both scales were dichotomized at their medians, with the lower half representing the unexposed group.

Age, acculturation, drug or alcohol use and gay organization membership were retained in the multivariable analysis. Income was marginally significant (p=0.05), but this variable also caused a reduction in sample size of greater than 20% because of missing data and was not included in the analysis.

Of the two primary exposures under investigation, higher CSB had the stronger association with high-risk sex (Table 2). While the interaction between CSB and IH was not statistically significant (p=0.10) at the more traditional 0.05 level, it is possible that an interaction would be less than the multiplicative one assumed by the model (Rothman & Greenland, 1998). The inclusion of gay organization membership to the regression analysis altered the statistical significance of the term for IH, and resulted in an observed main effect with marginal statistical significance (p=0.054). The results of the likelihood ratio test revealed a probable interaction between IH and gay organization membership, although it was still not significant under the multiplicative assumption (p=0.07). In order to explore these possible interactions, we stratified the sample by IH and gay organization membership.

Table 3 shows the results of the final logistic regression analysis of CSB and high-risk sex, adjusted for age, acculturation, and drug or alcohol use during the last sexual encounter, stratified by both the level of IH (above/below the median) and membership in a gay organization (yes/no). The included sample size in the final regressions reflected a loss of 14 respondents because of missing data on one or more covariates. The results of the stratified analyses are exploratory, and must be interpreted with caution given the overlap of the 95% confidence intervals. The pattern of the point estimates suggests that the association between CSB and high-risk sex is comparable among men with lower IH, regardless of gay organization membership. Among men with higher IH, the avoidance of gay organizations attenuates the association between CSB and high-risk sex. Affiliation with a gay organization, in contrast, facilitates a strong relationship between CSB and high-risk sex.

Table 3.

Prevalence odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals of high-risk sex, stratified by membership in a gay organization and level of internalized homonegativity.

| Internalized homonegativity |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Below median | Above median | |||

|

|

|

|||

| N | PORa (95% CI) | N | PORa (95% CI) | |

| Gay organization membership | ||||

| No | 222 | 3.82 (2.02, 7.22) | 356 | 1.57 (0.90, 2.72) |

| Yes | 251 | 3.51 (1.99, 6.20) | 120 | 4.30 (1.42, 13.1) |

Prevalence odds ratios, adjusted for age, acculturation, and drug or alcohol use at the last sexual encounter.

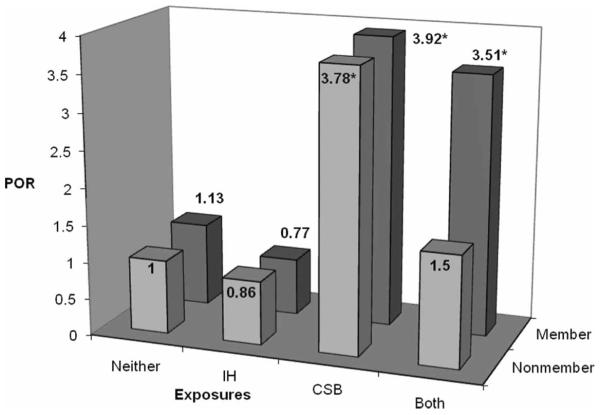

Figure 1 shows a graphic representation of a joint effects analysis of the exposures to CSB, IH and gay organization membership. The individual associations of CSB and IH with high-risk sex did not vary by gay organization membership. The joint relationship between the two constructs and high-risk sex was antagonistic in the absence of gay organization membership. The antagonistic relationship between the constructs diminished among men affiliated with a gay organization.

Figure 1.

Prevalence odds ratios for the joint effects of internalized homonegativity (IH), compulsive sexual behavior (CSB) and gay organization membership on high-risk sex.

*Statistical significance (p<0.05) in reference to unexposed, non-members. The likelihood of high-risk sex is strong among those with higher compulsive sexual behavior. Exposure to both internalized homonegativity and compulsive sexual behavior is antagonistic among men who are not members of a gay organization. The likelihood of high-risk sex is comparable between men with higher compulsive sexual behavior, regardless of organization membership, and among men who are organization members and who scored higher for both internalized homonegativity and compulsive sexual behavior.

As a final consideration, drug or alcohol use during the last sexual encounter, adjusted for all other variables in the analysis, was associated with a fourfold increase in the risk of high-risk sex among those with higher IH and membership in a gay organization (POR=5.37, 95% CI=2.16, 13.3). This variable was also significant in the adjusted model for those with lower IH and no gay organization membership, but the magnitude of effect was much lower (POR=2.11, 95% CI=1.08, 4.13).

Discussion

There exists a moderate correlation between CSB and IH in this sample. While the two constructs are associated, data on the temporal sequence are required to test for causality. It is theoretically plausible that IH could lead to CSB, that the two constructs develop simultaneously, or that patterns of CSB elicit IH. More research will be needed to investigate the nature of this relationship. At present, IH accounted for only 8% of the variance in CSB.

After building an explanatory model, CSB demonstrated a strong relationship with high-risk sex in the total sample, which is corroborated by existing studies (Benotsch, Kalichman, & Cage, 2002; Coleman et al., 2001). Upon stratification, it appears that CSB was not associated with high-risk sex among men with high IH who are not members of a gay organization. In contrast, the strongest association between CSB and high-risk sex was seen among men with high IH who were members of gay organizations. This finding runs counter to other studies that endorsed the protective effect of membership in a gay organization, chiefly through increased social support and access to safe sex messages (Kelly et al., 1995; Lemp, Hirozawa, Givertz, & Nieri, 1994; Meyer, 1995; Seibt et al., 1995). The high degree of overlap in the confidence intervals limits the strength of the interpretation of these findings. In future studies assessing these constructs, a larger sample size will be needed to improve power in order to replicate these findings.

Among populations of Latino men who have sex with men, discrimination, anxiety, depression, and younger age are all covariates associated with higher sexual risk-taking (Diaz, Ayala, Bein, Henne, & Marin, 2001; Diaz, Stall, Hoff, Daigle, & Coates, 1996; Diaz, et al., 2004; Magana & Carrier, 1991; Williams, Wyatt, Resell, Peterson, & Asuan-O' Brien, 2004). This investigation found conflicting results with the current literature in regards to age as it was associated with a modest increase in the odds of high-risk sex. The exclusion of younger participants without complete information on exposure may contribute to the interpretation of increasing age as a risk factor. In terms of acculturation, Marks, Cantero, and Simoni (1998) indicate that both high and low acculturation is associated with sexual risk-taking among Latino men. Our results found an increased risk associated with acculturation. One explanation for this could be the high acculturation of the sample in general, and the notion that questions targeted at outcomes other than language alone may be needed to assess acculturation (Diaz, 2000).

The assessment of the joint effects implicated gay organization membership as an effect measure modifier on the simultaneous effect of CSB and IH. The two constructs may lead to conflicting feelings on whether or not to have social contacts in the gay community. For those men with stronger CSB, the act of joining a gay organization increases their sexual network. For those men with stronger IH, avoidance of organizations restricts the number of potential partners. Future investigations of this modification of risk behavior should consider the type of organization membership and whether or not membership in an online group is considered organization membership.

In addition to increased risk as a product of behavioral maladaptations, this study demonstrated that drug use is associated with high-risk sex. The strongest association was found among those with higher IH and membership in gay organizations. This relationship lends support the hypothesis of drug or alcohol use as an intervening variable between IH and high-risk sex proposed by Ross et al. (2001).

The dichotomy in sexual risk-taking seen among men with both CSB and IH reflects the work of Kelus (1973). He proposed that maladaptations in a heterosexual population led to either avoidance of sexual behavior or, on the opposite extreme, high numbers of sexual partners. Still unknown from his work and in the present study are the intermediate steps or mechanisms in determining avoidance or increased activity; an understanding of which will enhance intervention capabilities.

Limitations

Several limitations accompany the results and interpretations presented in this study. These limitations include possible self-selection bias, exclusion of non-responders to components of the questionnaire, and reliability of measurement instruments. Additionally, these data were gathered in a cross-sectional interview, making the temporal sequence of CSB and IH impossible to discern.

In terms of self-selection bias, this study utilized an online format that advertised to Latino men using Internet portals, presumably to interact with other men who have sex with men. Men who agreed to participate in the survey may have lower levels of IH (Meyer, 1995) or CSB. As such, those men with higher levels that chose not to participate may report more or fewer sexual partners than expected given the results from the analytic sample. Additionally, Ross, Rosser, and Stanton (2004) demonstrated the representativeness of this Internet sample, but the exclusion of participants without exposure information likely diminished the generalizability to the larger population of Latino men who have sex with men.

Information bias in the form of misclassification is possible in terms of classifying individuals as having high or low CSB and IH. This is a result of using the median split in categorizing respondents. Since any bias would be non-differential, this would serve to underestimate the measures of association reported here (Rothman & Greenland, 1998).

Since denominators are difficult to ascertain for the true demographics of this population, Internet surveys seem appropriate, but are missing certain subsets. Evidence of this is the lack of data in this sample on men of lower education levels and lower acculturation. Less acculturated Latino men who have sex with men may be fundamentally different in terms of their perceived levels of CSB and IH. The association between these constructs and high-risk sex may also differ in comparison to the current study group. Diaz (1998) critiques many studies of this population as being biased to more acculturated, more educated Latino men. Since several studies lack data on less educated, less acculturated men, different sampling techniques are needed. Approaching this demographic will likely require non-traditional survey methods beyond Internet surveys.

Given the exploratory nature of these findings, validation in other datasets using statistical techniques such as structural equation modeling will help strengthen our understanding of the relationship of these variables. In addition, the use of data that include multiple ethnic groups will help determine whether the associations reported here are particular to Latino men or have implications in other racial/ethnic groups.

Conclusions

The Sexual Health Model (Robinson, Bockting, Rosser, Miner, & Coleman, 2002) includes mental health as a necessary facet of sexuality education and interventions. For men with larger gay social networks, health promotion programs should consider assessing and raising awareness about both CSB and IH. For men with smaller social networks, assessment of CSB may also be beneficial in reducing high-risk behavior. Since the latter group may be missed in more traditional recruiting methods, the use of the Internet or other vehicles that do not rely on social networks may facilitate future intervention efforts.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the assistance of Willo Pequegnat, PhD, project officer at NIMH, and the members of the original MINTS study team: Eli Coleman, Walter Bockting, Laura Gurak, Joseph Konstan, Michael Miner, Alex Carballo-Dieguez, Weston Edwards, Rafael Mazin, and Jeffrey Stanton. The Men's Internet Study (MINTS) was funded by the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH) Center for Mental Health Research on AIDS, grant number AG63688-01. All research was carried out with the approval of the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board, human subjects committee, study number 0102S83821.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

References

- Benotsch EG, Kalichman S, Cage M. Men who have met sex partners via the internet: Prevalence, predictors, and implications for HIV prevention. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2002;31(2):177–183. doi: 10.1023/a:1014739203657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benotsch EG, Kalichman SC, Pinkerton SD. Sexual compulsivity in HIV-positive men and women: Prevalence, predictors, and consequences of high-risk behaviors. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity. 2001;8(2):83–99. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Cases of HIV and AIDS in the United States and dependent areas, 2005. 2005 Retrieved July 5, 2007, from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/2005report/default.htm.

- Coleman E. Sexual compulsivity: Definition, etiology, and treatment considerations. Journal of Chemical Dependency Treatment. 1987;1(1):189–204. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman E, Miner M, Ohlerking F, Raymond N. Compulsive sexual behavior inventory: A preliminary study of reliability and validity. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 2001;27(4):325–332. doi: 10.1080/009262301317081070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Romero J, Castilla J, Garcia S, Clavo P, Ballesteros J, Rodriguez C. Time trend in incidence of HIV seroconversion among homosexual men repeatedly tested in Madrid, 1988–2000. AIDS. 2001;15(10):1319–1321. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200107060-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RM. Latino gay men and HIV: Culture, sexuality, and risk behavior. Routledge; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RM. Cultural regulation, self-regulation, and sexuality: A psycho-cultural model of HIV risk in Latino gay men. In: Parker R, Barbosa RM, Aggleton P, editors. Framing the sexual subject: The politics of gender, sexuality and power. University of California Press; Berkeley, CA: 2000. pp. 191–215. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RM, Ayala G, Bein E. Sexual risk as an outcome of social oppression: Data from a probability sample of Latino gay men in three U.S. cities. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2004;10(3):255–267. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.10.3.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RM, Ayala G, Bein E, Henne J, Marin BV. The impact of homophobia, poverty, and racism on the mental health of gay and bisexual Latino men: Findings from 3 US cities. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(6):927–932. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RM, Stall RD, Hoff C, Daigle D, Coates TJ. HIV risk among Latino gay men in the southwestern United States. AIDS Education & Prevention. 1996;8(5):415–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlayson AJR, Sealy J, Martin PR. The differential diagnosis of problematic hypersexuality. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity. 2001;8(3/4):241–251. [Google Scholar]

- Gay.com website. Gay.com Accessed June 12, 2007, from http://www.gay.com.

- Gold SN, Heffner CL. Sexual addiction: Many conceptions, minimal data. Clinical Psychology Review. 1998;18(3):367–381. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(97)00051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman A. What's in a name? Terminology for designating a syndrome of driven sexual behavior. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity. 2001;8(3/4):191–213. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg RS, Weber AE, Chan K, Martindale S, Cook D, Miller ML, et al. Increasing incidence of HIV infections among young gay and bisexual men in Vancouver. AIDS. 2001;15(10):1321–1322. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200107060-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer D, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. 2nd ed. Wiley; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Cain D. The relationship between indicators of sexual compulsivity and high risk sexual practices among men and women receiving services from a sexually transmitted infection clinic. Journal of Sex Research. 2004;41(3):235–241. doi: 10.1080/00224490409552231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Greenberg J, Abel GG. HIV-seropositive men who engage in high-risk sexual behaviour: Psychological characteristics and implications for prevention. AIDS Care. 1997;9(4):441–450. doi: 10.1080/09540129750124984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Rompa D. Sexual sensation seeking and sexual compulsivity scales: Reliability, validity, and predicting HIV risk behavior. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1995;65(3):586–601. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6503_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JA, Sikkema KJ, Winett RA, Solomon LJ, Roffman RA, Heckman TG, et al. Factors predicting continued high-risk behavior among gay men in small cities: Psychological, behavioral, and demographic characteristics related to unsafe sex. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1995;63(1):101–107. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelus J. Social and behavioural aspects of venereal disease. British Journal of Venereal Diseases. 1973;49(2):167–170. doi: 10.1136/sti.49.2.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemp GF, Hirozawa AM, Givertz D, Nieri GN. Seroprevalence of HIV and risk behaviors among young homosexual and bisexual men: The San Francisco/Berkeley young men's survey. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 1994;272(6):449–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magana JR, Carrier JM. Mexican and Mexican American male sexual behavior & spread of AIDS in California. Journal of Sex Research. 1991;28(3):425–441. [Google Scholar]

- Marks G, Cantero PJ, Simoni JM. Is acculturation associated with sexual risk behaviours? An investigation of HIV-positive Latino men and women. AIDS Care. 1998;10(3):283–295. doi: 10.1080/713612418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36(1):38–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratti R, Bakeman R, Peterson JL. Correlates of high-risk sexual behaviour among Canadian men of South Asian and European origin who have sex with men. AIDS Care. 2000;12(2):193–202. doi: 10.1080/09540120050001878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson BE, Bockting WO, Rosser BRS, Miner M, Coleman E. The sexual health model: Application of a sexological approach to HIV prevention. Health Education Research. 2002;17(1):43–57. doi: 10.1093/her/17.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross MW, Rosser BR, Stanton J. Beliefs about cybersex and internet-mediated sex of Latino men who have internet sex with men: Relationships with sexual practices in cybersex and in real life. AIDS Care. 2004;16(8):1002–1011. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331292444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross MW, Rosser BRS. Measurement and correlates of internalized homophobia: A factor analytic study. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1996;52(1):15–21. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(199601)52:1<15::AID-JCLP2>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross MW, Rosser BRS, Bauer GR, Bockting WO, Robinson BE, Rugg DL, et al. Drug use, unsafe sexual behavior, and internalized homonegativity in men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 2001;5(1):97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Rosser BRS, Bockting WO, Ross MW, Miner MH, Coleman E. The relationship between homosexuality, internalized homonegativity, and mental health in men who have sex with men. Journal of Homosexuality. 2008a doi: 10.1080/00918360802129394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosser BRS, Miner MH, Bocktin WO, Ross MW, Konstan J, Gurak L, et al. HIV risk and the internet: Results of the men's INTernet study (MINTS) AIDS and Behavior. 2008b doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9399-8. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman KJ, Greenland S. Modern epidemiology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Seibt AC, Ross MW, Freeman A, Krepcho M, Henrich A, McAlister A, et al. Relationship between safe sex and acculturation into the gay subculture. AIDS Care. 1995;7(Suppl. 1):S85–S88. doi: 10.1080/09540129550126876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp . Statistical software. Author; College Station, TX: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Williams JK, Wyatt GE, Resell J, Peterson J, Asuan-O' Brien A. Psychosocial issues among gay- and non-gay-identifying HIV-seropositive African American and Latino MSM. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2004;10(3):268–286. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.10.3.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolitski RJ, Valdiserri RO, Denning PH, Levine WC. Are we headed for a resurgence of the HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men? American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(6):883–888. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]