Abstract

Strongyloides is a parasite that is common in tropical regions. Infection in the immunocompetent host is usually associated with mild gastrointestinal symptoms. However, in immunosuppressed individuals it has been known to cause a “hyperinfection syndrome” with fatal complications. Reactivation of latent infection and rarely transmission from donor organs in transplanted patients have been suggested as possible causes. Our case highlights the importance suspecting Strongyloides in transplant recipients with atypical presentations and demonstrates an incidence of donor derived infection. We also review the challenges associated with making this diagnosis.

1. Case

A 60-year-old Hispanic male originally from Puerto Rico with end-stage ischemic cardiomyopathy status postorthotopic heart transplantation (OHT) in July 2012 presented 2 months after transplant with fatigue and malaise. On arrival he appeared ill but afebrile. He had an episode of hemoptysis and was admitted for further evaluation.

His posttransplant course was complicated by recurrent episodes of cellular rejection requiring both oral and intravenous pulse dose steroids. His immunosuppression regimen at time of presentation included mycophenolate mofetil 1500 mg twice daily in addition to tacrolimus 2.5 mg and 20 mg prednisolone daily. His most recent endomyocardial biopsy (EMBx) revealed resolution of cellular rejection with normal hemodynamics. On hospital day 1, he underwent repeated EMBx which was negative for evidence of cellular and antibody-mediated rejection. Echocardiography and right heart catheterization revealed normal allograft function and hemodynamics. He subsequently developed a worsening respiratory distress requiring transfer to the cardiac intensive care unit and intubation. Thereafter, he became profoundly hypotensive requiring initiation of norepinephrine in addition to broad spectrum antimicrobial coverage.

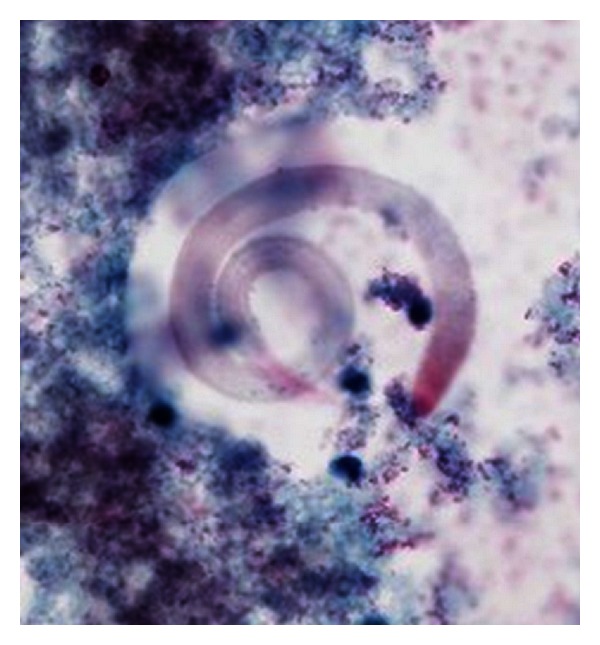

Over the next 72 hours, he became increasingly unstable requiring additional vasopressor support. Shortly after intubation, he underwent bronchoscopy and on day 4 of admission, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) revealed Strongyloides stercoralis as the parasite was visualized (Figure 1). Ivermectin and albendazole were initiated via nasogastric tube.

Figure 1.

BAL specimen showing adult worm.

With these interventions, the patient's hemodynamic and respiratory status improved. However, his neurological status did not improve despite withdrawal of sedation. Therefore a lumbar puncture was performed which revealed vancomycin resistant enterococcus and Strongyloides in the cerebrospinal fluid. Linezolid and daptomycin were therefore added to his regimen, but his neurological status never recovered and life-sustaining support was withdrawn on hospital day 26.

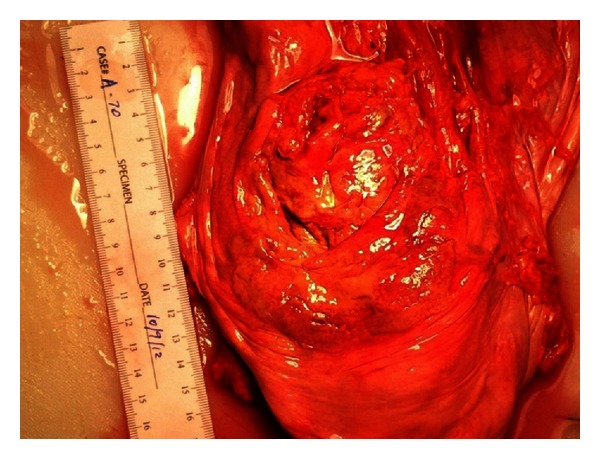

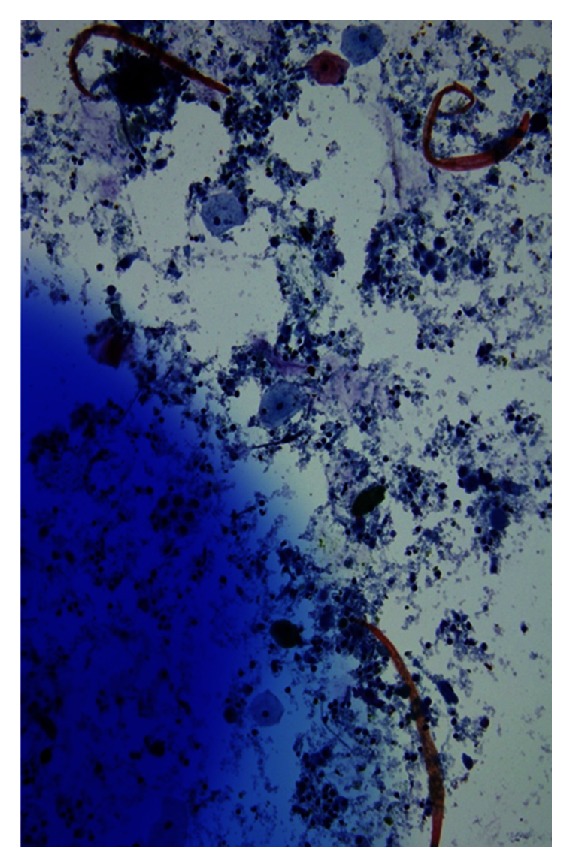

On autopsy, larval forms were identified in the lung, heart, lymph nodes, and liver. Additionally, a peritoneal exudate (Figure 2) was discovered on the serosal surface of the anterior rectum and bladder dome. Microscopic examination revealed this to be a peritoneal parasitoma with viable adult and larval forms (Figure 3 and see the video in Supplementary Material available online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/549038). Examination of the gastrointestinal tract revealed adult parasites within the jejunal bypass segment but not in the blind loop duodenum in this gentleman who had previously undergone a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, suggesting postgastric surgery infection.

Figure 2.

Anterior surface of the bladder dome revealing parisitoma at autopsy.

Figure 3.

Washings from parisitoma revealing larval forms.

Once Strongyloides was identified, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was contacted. Pretransplant donor serum was tested for Strongyloides antibody which was found to be positive while pretransplant recipient serum was compared and found to be negative (Table 1). The other institutions involved in organ transplantation from the same donor were informed of the developments by the CDC.

Table 1.

Allograft recipient posttransplant Strongyloides confirmation.

| Allograft | Pretransplant stronglyoides IgG enzyme immunoassay | Post-transplant confirmatory test | Presentation | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart | Negative | Bronchoscopy | Respiratory distress | Ivermectin and albendazole | Death |

| Liver | Negative | Not available | Sudden death | Not available | Death |

| Kidney | Negative | Endoscopy | Rash, fever | Ivermectin and albendazole | Recovered |

| Kidney/pancreas | Negative | Endoscopy | Abdominal abscess | Ivermectin and albendazole | Allograft failure |

2. Discussion

Strongyloides stercoralis is a helminthic intestinal parasite which is endemic in tropical and subtropical regions affecting 30 to 100 million people worldwide [1]. The southeast United States is considered endemic with most cases occurring in immigrants and veterans [2]. Strongyloides infection occurs by penetration of larvae through the skin on exposure to contaminated soil. Upon entry, the larvae travel through the bloodstream and reach the alveolar spaces of the lungs. The larvae are then expectorated and swallowed resulting in infection of the small intestine. The larvae mature into adult worms which then mate and release eggs. These eggs produce larvae which are either excreted through feces or mature into filariform larvae which can infect the intestinal tissue or penetrate perirectal mucosa to enter the circulatory system resulting in the so-called “auto infection” [3, 4]. It is in this fashion that disseminated infection can cause bacteremia with gut flora, as demonstrated in our case. Strongyloides infection is frequently asymptomatic or causes minimal gastrointestinal symptoms. However, hyperinfection with larval dissemination to systemic organs can occur. Those with compromised cell-mediated immunity are at increased risk for developing hyperinfection and its complications. This includes long-term chronic steroid use, transplant recipients including bone marrow and solid organs, and patients with HIV, HTLV infection [3, 5–7].

From 1991 to 2006 nearly 400 deaths due to Strongyloides have been reported. There were 16 reported cases of Strongyloides hyperinfection between 2006 and 2010, largely in immunocompromised individuals, with an estimated mortality rate of 69%. In the transplant population, strongyloidiasis has been reported in recipients of hematopoietic stem cells, kidneys, liver, heart, intestine, and pancreas [4, 7]. The sources of infection have been identified as chronic preexisting infection in the recipient or in rare cases from transmission of infection through the donor allograft organ [8].

3. Strongyloides in Orthotopic Heart Transplantation

To our knowledge there are 6 reported cases of Strongyloides in cardiac transplant patients to date (Table 2) [8–13]. The source of infection in these patients seems to be either preexisting chronic infections in the recipient or from the allograft itself as in the case presented by Brügemann et al. All patients presented with nonspecific or vague gastrointestinal complaints. Strongyloides hyperinfection in this population carries a high risk of mortality as only 1 of the previously reported 6 cases survived.

Table 2.

Strongyloidiasis in cardiac transplantation.

| Source | Allograft | Time from transplant | Risk factors | Presentation | Diagnostic test | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schaeffer et al. [9] | Heart | 2 months | Travel to southeastern US | Perforated colon | BAL examination | Thiabendazole × 15 days Ivermectin × 15 days |

Death |

|

| |||||||

| El Masry and O'Donnell [10] | Heart | 41 days | From Kentucky | Respiratory distress | Alveolar tissue on autopsy |

None | Death |

|

| |||||||

| Mizuno et al. [11] | Heart/ kidney |

28 days | From Florida | Respiratory distress | Autopsy findings | None | Death |

|

| |||||||

| Roxby et al. [8] | Heart | 2 months | Immigrant from Ethiopia |

Dyspnea Abdominal pain Nausea |

Sputum examination |

Oral ivermectin |

Death |

|

| |||||||

| Brügemann et al. [12] | Heart | 6 weeks | Abdominal pain Anorexia Nausea |

Skin biopsy | Oral ivermectin × 15 days Albendazole oral × 10 days |

Successful treatment |

|

|

| |||||||

| Grover et al. [13] | Heart | 4 weeks | From Southeastern US |

Nausea vomiting |

Duodenal biopsy |

Ivermectin | Death |

4. Donor Derived Strongyloides Infection in Transplant Recipients

Donor derived Strongyloides infection is a rare but a reported occurrence. To our knowledge there are 10 prior cases in the literature (Table 3) [12, 14–19]. Symptoms were observed within 6 weeks to 9 months after transplantation with a wide variety of presentations including rashes and nonspecific gastrointestinal complaints, as well as fulminant hyperinfection syndrome and respiratory distress. Oral albendazole and ivermectin were used for treatment in the majority of cases. In one case, ivermectin was continued intermittently as a form of secondary prophylaxis. In another case, specific FDA approval was obtained to administer veterinary ivermectin (Ivomec 1% injection) on a compassionate-use basis. Five of the reported cases experienced successful treatment, whereas 4 patients died due to the infection and its related complications. One patient was successfully treated but died later in the same hospitalization due to acinetobacter bacteremia. In only 3 of the reported cases was the donor confirmed to have Strongyloides. In the remaining cases, the donor allograft was suspected as a result of clinical reasoning, which took into account the donor's origin, evidence of Strongyloides infection in multiple recipients from the same donor, and pathologic findings.

Table 3.

| Source | Allograft | Time from transplant | Demographic risk factor | Presenting feature | Diagnostic test | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Said et al. [14] | Kidney | 48 days | Cadaveric donor from South Asia | SHS | BAL examination | Oral and rectal albendazole/ivermectin | Death |

| Kidney | 90 days | Cadaveric donor from South Asia | SHS | BAL examination | Oral and rectal albendazole/ivermectin | Death | |

| Kidney | 92 days | SHS | BAL examination | Oral and rectal albendazole/ivermectin | Death | ||

|

| |||||||

| Huston et al. [15] | Kidney | 90 days | Cadaveric donor from Puerto Rico | Fever and respiratory distress | BAL examination | Oral and rectal albendazole/ivermectin Trial of veterinary ivermectin (after case-specific FDA approval) × 3 doses |

Successful treatment |

|

| |||||||

| Hoy et al. [16] | Kidney Kidney |

33 days 64 days |

None | Diarrhea and fever Cough and fever |

Stool analysis Urine analysis |

Thiabendazole × 5 d Thiabendazole × 5 d |

Death Successful treatment |

|

| |||||||

| Patel et al. [17] | Intestine | 9 months | Donor from Honduras | Nausea/vomiting and abdominal discomfort Fevers |

Small bowel and colon endoscopic biopsy BAL examination |

Oral ivermectin/thiabendazole and rectal ivermectin × 10 d | Successful treatment initially but died later during the same hospitalization due to acinetobacter bacteremia |

|

| |||||||

| Ben-Youssef et al. [18] | Pancreas | 49 days | Donor was immigrant to the USA | Hematuria and epigastric pain | Duodenal biopsy | Oral thiabendazole/ivermectin × 7 d | Successful treatment |

|

| |||||||

| Brügemann et al. [12] | Heart | 6 weeks | Donor from Surinam | Abdominal pain and rash | Skin biopsy | Oral ivermectin × 15 d Oral albendazole × 10 d |

Successful treatment |

|

| |||||||

| Rodriguez- Hernandez et al. [19] |

Liver | 2.5 months | Donor from Ecuador | Anorexia and diarrhea | Sputum and stool sample examination | Oral albendazole/ivermectin × 2 weeks, then ivermectin only × 2 weeks, followed by intermittent ivermectin secondary prophylaxis | Successful treatment |

SHS: Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome.

BAL: bronchoalveolar lavage.

5. Diagnosis and Treatment

Various diagnostic tests are available, with a wide range of diagnostic accuracy (Table 4) [1, 20–24]. Stool culture is only useful in chronic strongyloidiasis if there is regular and constant larval output, thereby making it unreliable [2, 21, 23]. Treatment regimens include one or two doses of ivermectin and/or a 7-day course of oral albendazole. One and two doses of ivermectin at two-week intervals were more likely to attain higher parasitological cure rate compared to albendazole [25]. In Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome, ivermectin 200 mcg/kg/day has been used for up to two weeks until stool tests are negative. Although it is not FDA approved, anecdotal evidence suggests that use of subcutaneous or rectal ivermectin at the same dose may be useful in cases of malabsorption or poor oral intake [4].

Table 4.

Currently available strongyloides diagnostic studies.

| Diagnostic test | Sensitivity/specificity | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stool smear Baermann [20] | 75% | Easily obtained | Requires multiple specimens to improve sensitivity and specificity |

|

| |||

| ELISA IgG [21] | 97% sensitivity 95% specificity |

High sensitivity High specificity |

False negatives Other filarial reactions can cause false positivity Remains positive for extended periods even after treatment |

|

| |||

| Stool on Agar plate culture [1, 22] | 96% sensitivity | High sensitivity | Requires at least 2 days |

|

| |||

| PCR [23, 24] | >95% sensitivity >95% specificity |

High specificity Becomes negative after successful treatment |

Not all diagnostic centers are equipped to perform test |

|

| |||

| Luciferous immunoprecipitation System [21] |

97% sensitivity 100% specificity |

<2.5 hours High sensitivity and Specificity Seroconversion after treatment |

Not all labs have capability to perform test |

6. Summary

Strongyloides hyperinfection can happen anytime after transplant. However, there seems to be predilection to strike within the first 3 months during times of increased immunosuppression. ISHLT guidelines recommend the use of antiviral, fungal, and protozoal prophylaxis immediately after a cardiac transplant; however, this does not include prophylaxis against Strongyloides. While screening is recommended for those potential recipients with an appropriate travel history, there is no recommended screening program in potential donors [26, 27]. Although cost issues have to be taken into account before instituting a standard protocol for screening for such a rare occurrence, the frequency of Strongyloides infection may increase in the future given the changing demographics of donor and recipient pools. Screening could be narrowed only to high-risk populations such as those from endemic areas. Fitzpatrick et al. have made a case to screen transplant donors and recipients of Hispanic origin given their potential for increased exposure due to origin or travel from endemic areas [28]. Also atypical symptoms and/or signs in transplanted patients should prompt an early investigation with serological assays, BAL, or upper GI endoscopy whichever might apply to the situation. In the reported 6 heart transplant recipients who developed Strongyloides hyperinfection, attempted treatment was not successful in 5 patients. This highlights the importance of earlier screening in transplanted or potential transplant recipients. The arrival of luciferase precipitation systems assay and real time polymerase chain reaction testing may pave the way for a better screening tool. Our recommendation would also be to empirically treat with ivermectin or albendazole along with a reduction in immunosuppression in transplant recipients with atypical clinical presentations. We would also recommend testing of at-risk donors with treatment of the organ recipients once results become available.

Supplementary Material

Video of the parisitoma washings revealing viable larval forms in motion.

Conflict of Interests

The authors have no conflict of interests to disclose.

References

- 1.Siddiqui AA, Berk SL. Diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis infection. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2001;33(7):1040–1047. doi: 10.1086/322707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Montesa M, Sawhney C, Barrosa N. Strongyloides stercoralis: there but not seen. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 2010;23(5):500–504. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32833df718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong B. Parasitic diseases in immunocompromised hosts. The American Journal of Medicine. 1984;76(3):479–486. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(84)90667-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mejia R, Nutman TB. Screening, prevention, and treatment for hyperinfection syndrome and disseminated infections caused by Strongyloides stercoralis . Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 2012;25(4):458–463. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3283551dbd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Genta RM. Strongyloides stercoralis: immunobiological considerations on an unusual worm. Parasitology Today. 1986;2(9):241–246. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(86)90003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kassalik M, Mönkemüller M. Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection syndrome and disseminated disease. Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2011;7(11):766–768. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marcos LA, Terashima A, Canales M, Gotuzzo E. Update on strongyloidiasis in the immunocompromised host. Current Infectious Disease Reports. 2011;13(1):35–46. doi: 10.1007/s11908-010-0150-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roxby AC, Gottlieb GS, Limaye AP. Strongyloidiasis in transplant patients. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2009;49(9):1411–1423. doi: 10.1086/630201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schaeffer MW, Buell JF, Gupta M, Conway GD, Akhter SA, Wagoner LE. Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome after heart transplantation: case report and review of the literature. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2004;23(7):905–911. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2003.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El Masry HZ, O’Donnell J. Fatal stongyloides hyperinfection in heart transplantation. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2005;24(11):1980–1983. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mizuno S, Iida T, Zendejas I, et al. Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome following simultaneous heart and kidney transplantation. Transplant International. 2009;22(2):251–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2008.00767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brügemann J, Kampinga GA, Riezebos-Brilman A, et al. Two donor-related infections in a heart transplant recipient: one common, the other a tropical surprise. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2010;29(12):1433–1437. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grover IS, Davila R, Subramony C, Daram SR. Strongyloides infection in a cardiac transplant recipient: making a case for pretransplantation screening and treatment. Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2011;7(11):763–766. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Said T, Nampoory MRN, Nair MP, et al. Hyperinfection strongyloidiasis: an anticipated outbreak in kidney transplant recipients in Kuwait. Transplantation Proceedings. 2007;39(4):1014–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huston JM, Eachempati SR, Rodney JR, et al. Treatment of Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection-associated septic shock and acute respiratory distress syndrome with drotrecogin alfa (activated) in a renal transplant recipient. Transplant Infectious Disease. 2009;11(3):277–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2009.00386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoy WE, Roberts NJ, Jr., Bryson MF. Transmission of strongyloidiasis by kidney transplant? Disseminated strongyloidiasis in both recipients of kidney allografts from a single cadaver donor. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1981;246(17):1937–1939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel G, Arvelakis A, Sauter BV, Gondolesi GE, Caplivski D, Huprikar S. Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome after intestinal transplantation. Transplant Infectious Disease. 2008;10(2):137–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2007.00256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ben-Youssef R, Baron P, Edson F, Raghavan R, Okechukwu O. Stronglyoides stercoralis infection from pancreas allograft: case report. Transplantation. 2005;80(7):997–998. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000173825.12681.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodriguez-Hernandez MJ, Ruiz-Perez-Pipaon M, Cañas E, Bernal C, Gavilan F. Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection transmitted by liver allograft in a transplant recipient: case report. American Journal of Transplantation. 2009;9(11):2637–2640. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khieu V, Schär F, Marti H, et al. Diagnosis, treatment and risk factors of Strongyloides stercoralis in schoolchildren in Cambodia. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2013;7(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002035.e2035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramanathan R, Burbelo PD, Groot S, Iadarola MJ, Neva FA, Nutman TB. A luciferase immunoprecipitation systems assay enhances the sensitivity and specificity of diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis infection. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2008;198(3):444–451. doi: 10.1086/589718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inês Ede J, Souza JN, Santos RC, et al. Efficacy of parasitological methods for the diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis and hookworm in faecal specimens. Acta Tropica. 2011;120(3):206–210. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verweij JJ, Canales M, Polman K, et al. Molecular diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis in faecal samples using real-time PCR. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2009;103(4):342–346. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moghaddassani H, Mirhendi H, Hosseini M, Rokni MB, Mowlavi G, Kia E. Molecular diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis infection by PCR detection of specific DNA in human stool samples. Iranian Journal of Parasitology. 2011;6(2):23–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suputtamongkol Y, Premasathian N, Bhumimuang K, et al. Efficacy and safety of single and double doses of ivermectin versus 7-day high dose albendazole for chronic strongyloidiasis. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2011;5(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001044.e1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Costanzo MR, Dipchand A, Starling R, et al. The international society of heart and lung transplantation guidelines for the care of heart transplant recipients, Task Force 1: Peri-operative Care of the Heart Transplant Recipient, August 2010. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Mehra MR, Kobashigawa J, Starling R, et al. Listing criteria for heart transplantation: international society for heart and lung transplantation guidelines for the care of cardiac transplant candidates. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2006;25(9):1024–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fitzpatrick MA, Caicedo JC, Stosor V, Ison MG. Expanded infectious diseases screening program for Hispanic transplant candidates. Transplant Infectious Disease. 2010;12(4):336–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2010.00517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Video of the parisitoma washings revealing viable larval forms in motion.