Abstract

Multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) decrease the expression of transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1) in astrocytes and subsequently decrease astrocytic plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1) level in an autocrine manner. Since activated microglia/macrophages are also a source of TGFβ1 after stroke, we therefore tested whether MSCs regulate TGFβ1 expression in microglia/macrophages and subsequently alters PAI-1 expression after ischemia. TGFβ1 and its downstream effector phosphorylated SMAD 2/3 (p-SMAD 2/3) were measured in mice subjected to middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAo). MSC treatment significantly decreased TGFβ1 protein expression in both astrocytes and microglia/macrophages in the ischemic boundary zone (IBZ) at day 14 after stroke. However, the p-SMAD 2/3 was only detected in astrocytes and decreased after MSC treatment. In vitro, RT-PCR results showed that the TGFβ1 mRNA level was increased in both astrocytes and microglia/macrophages in an astrocyte-microglia/macrophage co-culture system after oxygen-glucose deprived (OGD) treatment. MSCs treatment significantly decreased the above TGFβ1 mRNA level under OGD conditions, respectively. OGD increased the PAI-1 mRNA in astrocytes in the astrocyte-microglia/macrophage co-culture system, and MSC administration significantly decreased this level. PAI-1 mRNA was very low in microglia/macrophages compared with that in astrocytes under different conditions. Western blot results also verified that MSC administration significantly decreased p-SMAD 2/3 and PAI-1 level in astrocytes in astrocyte-microglia/macrophage co-culture system under OGD conditions. Our in vivo and in vitro data, in concert, suggest that MSCs decrease TGFβ1 expression in microglia/macrophages in the IBZ which contribute to the down-regulation of PAI-1 level in astrocytes.

Keywords: Multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells, Microglia/macrophages, Astrocytes: transforming growth factor β1, Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1, Stroke

1. Introduction

The adult human brain is made up of approximately 100 billion neurons and trillions of glia [11]. The most numerous glial cells, astrocytes, fulfill a vital task of neuronal repair after central nervous system (CNS) injury [22]. Endogenous tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and its inhibitor, plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1) are associated with neurite remodeling after stroke [21,26]. Astrocyte-derived PAI-1 plays a major role in regulating tPA/PAI-1 activity [2]. Our previous data demonstrated that administration of mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) decreased transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1) expression which subsequently decreased the PAI-1 level in an autocrine manner in astrocytes [25]. This decrease in PAI-1 induces neurite outgrowth by increasing tPA activity after stroke [26].

Microglia constitute approximately 20% of the total glial cell population within the brain [14]. They can promote regrowth of neural tissue [9]. Without microglia, regrowth and remapping would be considerably slower in the resident areas of the CNS [9]. Microglia and astrocytes are distributed in large non-overlapping regions throughout the brain and spinal cord [3,13]. Ischemia induces expression of TGFβ1 in reactive astrocytes and microglia/macrophages [6], and the activated microglia/macrophages are a primary source of TGFβ1 after stroke [16]. In the present study, we hypothesize that MSCs affect TGFβ1 expression in microglia/macrophages which further contribute to the regulation of PAI-1 expression in astrocytes in the ischemic boundary zone (IBZ) after stroke.

2. Materials and methods

All experimental procedures were carried out in accordance with the standards and procedures of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Henry Ford Hospital.

2.1. Animal middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAo) model and cell transplantation

Mice were subjected to permanent MCAo following the protocol used in our lab [5]. At 24 h post-ischemia, randomly selected mice received MSC (derived from C57BL/6J mice, 1 × 106 in 0.5 mL phosphate-buffered saline, PBS) or PBS (n = 9/group) administration via the tail vein. All mice were euthanized at 14 days after MCAo, among which, 6 frozen brains were used for protein extraction (n = 3/group), and the remaining 12 brains (n = 6/group) were embedded in paraffin and processed for immunohistostaining analyses.

2.2. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) analysis of TGFβ1 level

For the protein extraction and ELISA sample preparation, mouse brains were transcardially perfused with saline and snap frozen brains were cryosectioned at 40 μm and stored at –80 °C. As indicated in Fig. 1A, we extracted the protein from the ischemic core, IBZ and homologous contralateral tissues with Radio-Immune Precipitation Assay buffer containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (P8340, Sigma–Aldrich Co. LLC., St. Louis, MO). The total protein concentrations were determined with the Bicinchoninic Acid Protein Assay Kit (23227, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL). The TGFβ1 level in 40 μg total protein mouse brain tissue extracts and cultured media from astrocytes and microglia/macrophages were measured with a mouse/human TGFβ1 ELISA Ready-SET-Go! Kit (88-7344, eBioscience, Inc., San Diego, CA), following the manufacturer's assay procedures.

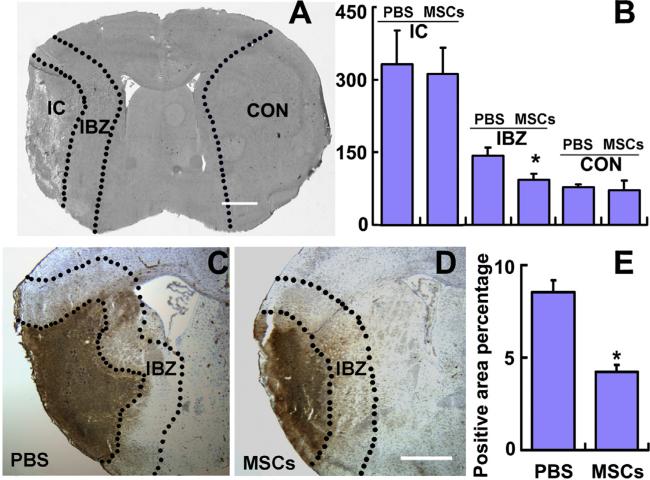

Fig. 1.

TGFβ1 protein expression decreased in the IBZ after MSC treatment. ELISA analysis showing the TGFβ1 protein levels in the ischemic core, IBZ and contralateral brain tissues (A and B). MSC treatment significantly down-regulated the TGFβ1 level in the IBZ, compared to PBS treatment. Immunostaining indicating the TGFβ1 expression (C and D). Analysis data show that MSC treatment significantly down-regulated the TGFβ1 expression along the IBZ, compared to PBS treatment. CON: normal contralateral brain tissue, IBZ: ischemic boundary zone, IC: ischemic core. Scale bars: 1000 μm. *P < 0.05 vs PBS.

2.3. Histological and immunohistochemical assessment

Deparaffinized brain sections were incubated with the antibody against TGFβ1 (1:250, sc-146, Santa Cruz, CA), and then incubated with avidin–biotin–horseradish peroxidase complex and developed in 3′3′ diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB) as a chromogen for light microscopy. Double immunostaining was employed to identify the cellular co-localization of TGFβ1 (1:50) or p-SMAD 2/3 (1:50, sc-11769, Santa Cruz) with glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, a marker of astrocyte, 1:10000, Z0334, Dako, Carpinteria, CA) or isolectin-B4 (IB4, a marker of microglia/macrophages, dilution 1:50, L5391, Sigma, Saint Louis, MO). The CY3 conjugated antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Groove, PA) or fluorescein isothiocyanate conjugated antibody (FITC, Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA) were employed for double immunoreactivity identification.

Immunoreactive signals were analyzed with the National Institutes of Health Image software (Image J) based on evaluation of an average of 3 histology slides. For measurements of TGFβ1 density, 9 fields of view along the ischemic boundary zone (IBZ, 4 in the cortex, 1 in the corpus callosum, and 4 in the striatum) were digitized under a ×40 objective (Carl Zeiss Axiostar Plus Microscope) via the MicroComputer Imaging Device analysis system. Data were presented as percentage of TGFβ1 immunoreactive area. To examine the TGFβ1 and p-SMAD 2/3 levels alteration in astrocytes or microglia/macrophages, the number of double stained positive cells along the IBZ were calculated based on an average of 3 histology slides per mouse.

2.4. In vitro co-culture system and oxygen-glucose deprived (OGD) treatment

Astrocytes (C8-D1A, CRL-2541™, ATCC, Arlington, VA) and microglia/macrophages (Walker EOC-20, CRL-2469™, ATCC) were conventionality cultured. In order to mimic the in vivo transient ischemic situations in the IBZ, we employed in vitro OGD and a transwell cell culture sytem (Becton Dickinson Labware, FALCON®). Using this transwell cell culture system, astrocytes and microglia/macrophages were separately seeded into upper or lower chambers (6-well plate, 1 × 105/well) and co-cultured in the same medium, in order to collect individual cell population. After cells grew to 70% confluence, the medium was replaced with non-glucose culture media and cultured in an anaerobic chamber (model 1025, Forma Scientific, OH) for 2 h in the OGD condition. The cells were then returned to conventional culture with or without MSC treatment. Primary MSCs from the hind legs of C57/Bl6 mice (2–3 m) were prepared, as previously described [19]. MSCs (3–4 passages) were added in to the upper chamber of the transwell insert dish with a ratio 1:100 of co-cultured MSCs to astrocytes or microglia/macrophages. The astrocytes or microglia/macrophages in the wells with or without MSC co-culture were detached and RNA and protein extracted after 24 h of MSC co-culture.

2.5. Quantitative real-time PCR and Western blot

Following the manufacturer's instructions, quantitative RT-PCR was performed in the ABI Prism 7000 sequence detection system. The following primers were employed: mouse TGFβ1 (F: GGACTCTCCACCTGCAAGAC, R: GACTGGCGAGCCTTAGTTTG) and mouse PAI-1 (F: GTCTTTCCGACCAAGAGCAG, R: ATCACTTGGCCCATGAAGAG). Mouse glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (F: GTCTACTGGTGTCTTCACCACCAT, R: GTTGTCATATTTCTCGTGGTTCAC) as the internal control.

The total protein was used for Western blot assay followed by the standard Western blotting protocol (Molecular Clone, Edition II). The concentrations of the primary antibodies employed were: p-SMAD 2/3 (sc-11769, 1:1000, Santa Cruz, CA), PAI-1 (1:2000, Santa Cruz, sc-8979), and beta actin (1:5000, Santa Cruz, sc-1616). The integrated density mean gray value of the bands was analyzed under the ImageJ software, and the corresponding relative expression ratio was calculated as protein of interest/beta actin.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SE. The differences between mean values were evaluated with the two tailed Student's t-test (for 2 groups) and the analysis of variance (ANOVA, for >2 groups) were performed by the computer programs Microsoft Excel 2000 or SPSS 11.5. P < 0.05 was considered significant for all analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Down-regulation of TGFβ1 expression in the IBZ after MSC treatment

Using TGFβ1 ELISA, we analyzed TGFβ1 levels in the ischemic core, IBZ and homologous contralateral tissues of the mouse brain (Fig. 1A). The TGFβ1 protein was detected in all the samples from the ischemic core (PBS: 332.7 ± 69.7 pg/mL, MSC: 310.2 ± 62.4 pg/mL), IBZ (PBS: 143.5 ± 16.3 pg/mL, MSC: 108.1 ± 13.8 pg/mL) and the contralateral tissues (PBS: 81.4 ± 3.6 pg/mL, MSC: 76.6 ± 17.6 pg/mL). As shown in Fig. 1B, MSC treatment significantly down-regulated the TGFβ1 level only in the IBZ. Immunostaining shows TGFβ1 (Fig. 1C and D) positive signaling in the ischemic core and IBZ. Our data suggest that MSC treatment significantly down-regulated the TGFβ1 expression in the IBZ (Fig. 1E).

3.2. MSC treatment decreased TGFβ1 in astrocytes and microglia/macrophages, as well as TGFβ1 downstream effector p-SMAD 2/3 in astrocytes in the IBZ

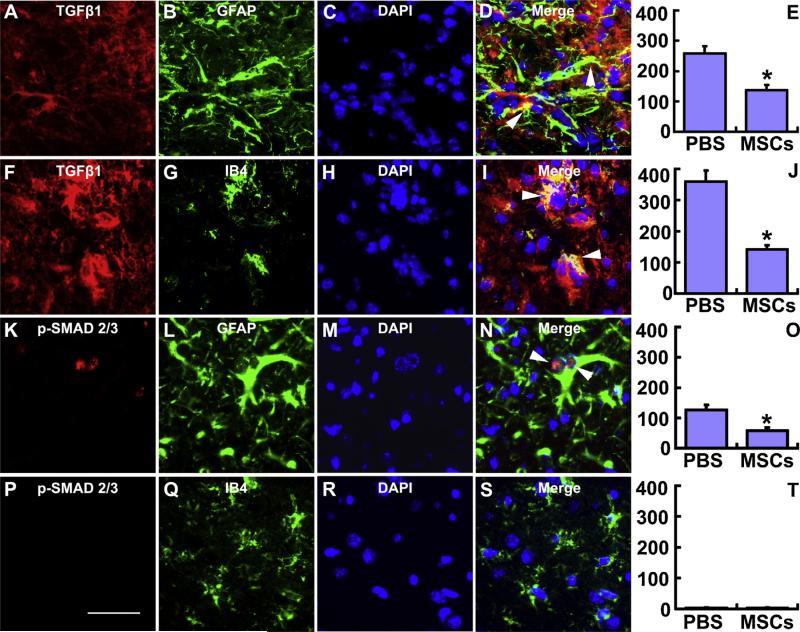

To measure the TGFβ1 level in astrocytes and/or microglia/macrophages in the IBZ modified by MSCs, we employed the double staining immunofluorescence method and calculated the number of double stained positive cells (arrow heads indicated), respectively. Fig. 2A–D and F–I show TGFβ1 co-located with both GFAP and IB4 positive staining cells, indicating that both astrocytes and microglia/macrophages express TGFβ1 in the IBZ. Statistical data show that MSC treatment significantly down-regulated the TGFβ1 expression in astrocytes and microglia/macrophages (Fig. 2E and J), respectively. Since PAI-1 expression is regulated by TGFβ1 through the TGFβ/SMAD pathway [7], we also measured the p-SMAD 2/3, and performed double immunofluorescent staining. As shown in Fig. 2K–N and Fig. 2P–S, the p-SMAD 2/3 colocalized with GFAP but not with IB4, indicating that the TGFβ1-SMAD 2/3-PAI-1reaction primarily affected astrocytes in the IBZ. Statistical data show that MSC treatment significantly down-regulated the p-SMAD 2/3 in astrocytes (Fig. 2O), but not in microglia/macrophages (Fig. 2T). These data support the hypothesis that MSC treatment decreases the TGFβ1 expression in astrocytes and microglia/macrophages, and then selectively down-regulates the activation of the astrocytic TGFβ1-SMAD 2/3 pathway.

Fig. 2.

Double immunofluorescent staining of brain sections identifies the cell types that express TGFβ1 and p-SMAD 2/3 in the IBZ. TGFβ1 was co-localized with both the astrocytic marker GFAP (A–D) and microglia/macrophage marker IB4 (F–I); however, p-SMAD 2/3 was only colocalized with GFAP in astrocytes (K–N). MSC treatment significantly decreased the TGFβ1 expression in astrocytes (E) and microglia/macrophages (J), and significantly down-regulated the phosphorylation of SMAD 2/3 in astrocytes (O) along the IBZ. Scale bars: 50 μm. *P < 0.05 vs PBS.

3.3. PAI-1 expression in astrocytes is affected by microglia/macrophage TGFβ1

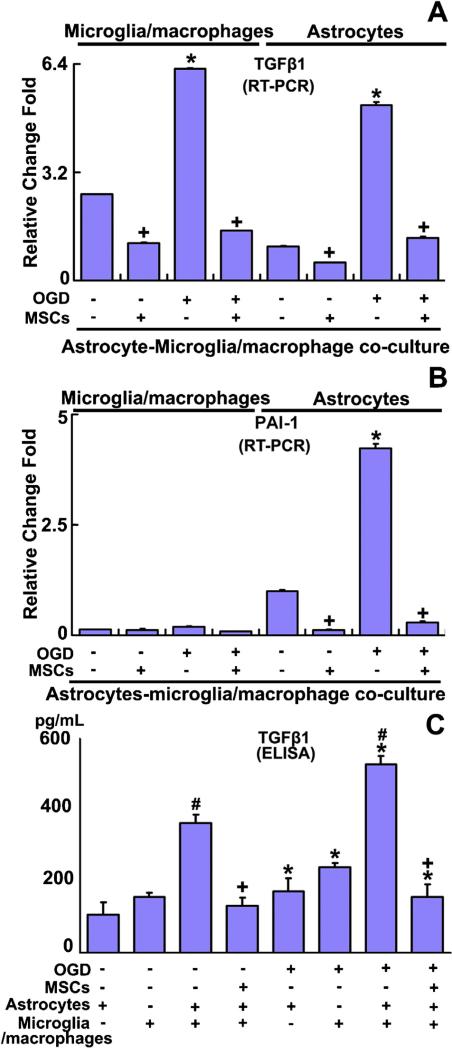

To test whether MSC treatment downregulates TGFβ1 in microglia/macrophages and subsequently affects the PAI-1 expression in astrocytes, we employed the in vitro OGD and co-culture model (Fig. 3) to mimic the in vivo conditions. RT-PCR detection data showed that the TGFβ1 mRNA level was significantly increased in both astrocytes and microglia/macrophages in the astrocyte-microglia/macrophage co-culture system after OGD treatment. MSC treatment significantly decreased the TGFβ1 level in astrocytes and microglia/macrophages in the astrocyte-microglia/macrophage co-culture system both under non-OGD and OGD conditions, respectively (Fig. 3A). PAI-1 mRNA in microglia/macrophages was very low and did not obviously respond to OGD or MSC treatment (Fig. 3B). Similar to the TGFβ1 mRNA level, OGD increased the PAI-1 mRNA in astrocytes in the astrocyte-microglia/macrophage co-culture system, and MSC treatment significantly decreased the PAI-1 mRNA in astrocytes in the astrocyte-microglia/macrophage co-culture system under non-OGD or OGD conditions, respectively (Fig. 3B). The cell culture media were then collected for ELISA to detect the TGFβ1 protein level. As shown in Fig. 3C, the TGFβ1 protein level was significantly increased in the media collected from co-cultured astrocyte-microglia/macrophage, compared with the media of individually cultured astrocytes or microglia/macrophages. OGD treatment significantly increased the TGFβ1 protein level in the above described groups, respectively, compared with their corresponding non-OGD treatment groups. MSC administration significantly down-regulated the TGFβ1 protein level in the media from the astrocyte-microglia/macrophage co-culture system under non-OGD or OGD conditions, respectively. These mRNA and protein level data indicate that in addition to the effect of MSCs on TGFβ1 expression in astrocytes, MSCs also affected the TGFβ1 expression in microglia/macrophages which impacts the TGFβ1 level in the astrocytic-microglia/macrophage system.

Fig. 3.

RT-PCR detection shows the TGFβ1 (A) and PAI-1 (B) mRNA level in astrocytes and microglia/macrophages in the astrocyte-microglia/macrophage co-culture system. ELISA results show TGFβ1 (C) protein concentration in cell culture media. TGFβ1 mRNA level was significantly increased in both astrocytes and microglia/macrophages in the astrocyte-microglia/macrophage co-culture system after OGD, compared with non-OGD treatment. MSC administration significantly reduced the TGFβ1 mRNA level in astrocytes and microglia/macrophages under non-OGD or OGD conditions (A). PAI-1 mRNA in microglia/macrophages was very low and did not obviously respond to OGD or MSC treatment (B). PAI-1 mRNA in astrocytes in the co-culture system was increased after OGD and MSC treatment significantly decreased it under non-OGD or OGD conditions, respectively (B). The TGFβ1 protein level was significantly increased in the astrocyte-microglia/macrophage co-culture system medium, compared with individual astrocytes or microglia/macrophages culture media. OGD treatment significantly increased the TGFβ1 protein level in media of cultured astrocytes and microglia/macrophages and in media of co-cultured astrocytes-microglia/macrophages, compared with their corresponding non-OGD treatment groups. MSC administration significantly down-regulated the TGFβ1 protein level under non-OGD or OGD conditions, respectively (C). *P < 0.05 OGD vs corresponding non-OGD culture; +P < 0.05 vs corresponding non-MSC treatment; #P < 0.05 astrocyte-microglia/macrophage co-culture vs individual culture of astrocytes or microglia/macrophages.

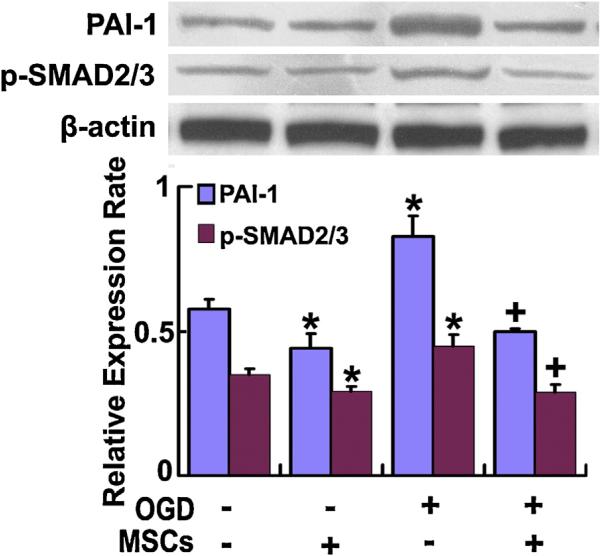

To further verify the downstream effectors of TGFβ1, we extracted the proteins of cultured astrocytes in the astrocyte-microglia/macrophage co-culture system for Western blot detection. Our data show that the p-SMAD 2/3 and PAI-1 protein levels in cultured astrocytes in the astrocyte-microglia/macrophage co-culture system were significantly increased under OGD conditions, and MSC administration significantly decreased these levels under non-OGD or OGD conditions, respectively (Fig. 4). Combined with the above TGFβ1 release data, our studies indicate that MSCs decreased the TGFβ1 level in both microglia/macrophages and astrocytes in the co-culture system; however, MSCs decreased PAI-1 expression only in astrocytes through the TGFβ1-SMAD 2/3 pathway.

Fig. 4.

Western blot used to detect the levels of astrocytic p-SMAD 2/3 and PAI-1 protein. Analysis data show the p-SMAD 2/3 and PAI-1 protein levels in astrocytes in the astrocyte-microglia/macrophage co-culture system were significantly increased under OGD condition, and MSC administration significantly decreased these levels under non-OGD or OGD conditions, respectively. *P < 0.05 vs normal cultured; #P < 0.05 vs non-MSC treatment.

4. Discussion

The benefits of MSCs on stroke recovery have been widely demonstrated [4]. MSCs promote axonal remodeling in the ischemic boundary zone and improve functional recovery post stroke via increase of tPA activity [21,26]. We have demonstrated that MSC treatment down-regulates TGFβ1 expression in astrocytes, which in an autocrine manner decreases the PAI-1 expression in astrocytes [25]. In the present study, we found that MSC treatment also down-regulated the TGFβ1 expression in microglia/macrophages within the IBZ and microglia/macrophages may decrease astrocytic PAI-1 expression. Thus, MSCs improvement of functional recovery after stroke may be mediated by the glial cells, i.e., astrocytes, and other cells, microglia/macrophages. Our studies confirm the concept that MSCs stimulate and produce important proteins in endogenous brain cells that enhance functional recovery after stroke.

Astrocytes and microglia are distributed ubiquitously throughout the brain and spinal cord, and one of their main functions is to monitor and sustain neuronal health [24]. They serve specific functions in the defense of the CNS against microorganisms, the removal of tissue debris in neurodegenerative diseases or during normal development, and in autoimmune inflammatory disorders of the brain [27]. Axon injury rapidly activates microglia/macrophages and astrocytes close to the axotomized neurons [2]. During activation, microglia/macrophages display conspicuous changes in cell morphology, cell number, cell surface receptor expression, and production of growth factors and cytokines [23]. Pathological activation of microglia/macrophages has been reported in a wide range of conditions such as cerebral ischemia, Alzheimer's disease, multiple sclerosis and others [18]. It is still under debate whether activated microglia/macrophages promote neuronal survival, or whether they exacerbate the original extent of neuronal damage [10]. Here, we discuss a potential role of activated microglia/macrophages in the modulation of bioactive factors which have previously demonstrated benefit for brain regeneration and synaptic plasticity. By decreasing the expression of TGFβ1 in activated microglia/macrophages, MSC treatment via a paracrine route regulates the PAI-1 expression in astrocytes which promotes neurite outgrowth [26] by increasing the tPA activity and subsequently enhances the functional recovery after stroke [21,26].

TGFβ plays a key role in the regulation of neuron survival and death [15]. The detrimental effects of TGFβ may be mediated by alterations in extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling [8]. Ischemia induces expression of TGFβ1 in reactive astrocytes and microglia/macrophages [6]. The presence of TGFβ1 greatly increased the production of several chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs), such as brevican, a proteoglycan of the lectican family, these CSPGs inhibit neurite outgrowth and may also stabilize synapses [17]. By degrading the ECM, neurotrophic factors can be released and regulate neuron development including neurite growth, survival and maturation of neuronal phenotypes in the central and peripheral nervous system [20]. MSC treatment decreases the TGFβ1 expression in microglia/macrophages, and then down-regulates the astrocytic PAI-1 expression, and thereby increases tPA activity. tPA activates matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) [1], a family of endopeptidases that primarily catalyze the turnover and degradation of the ECM, and consequently reduce astrogliosis, which may be important permissive elements for neuronal migration and neurite outgrowth [12]. The down-regulation of TGFβ1 level in microglia/macrophages directly decreases the production of CSPGs or indirectly releases the neurotrophic factors, ultimately increasing neurite outgrowth and improving functional recovery after stroke. Our data demonstrate that TGFβ1 expression is increased in both astrocytes and microglia/macrophages after ischemia. However subsequently, MSCs decrease PAI-1 level in astrocytes only, that may regulate tPA activity and promote neurite remodeling, supporting the hypothesis that predominantly reactive astrocytes foster neurite outgrowth and neurorestoration.

5. Conclusions

MSCs down-regulate TGFβ1 expression in microglia/macrophages located within the IBZ, which may contribute to the down-regulation of PAI-1 level in astrocytes via decrease of the phosphorylation of SMAD 2/3.

highlights.

MSCs reduced TGFβ1 level in astrocytes and microglia/macrophages after ischemia.

TGFβ1 down-regulation in microglia/macrophages reduced astrocytic PAI-1.

TGFβ1-SMAD 2/3 signal pathway regulated PAI-1 level in astrocytes.

PAI-1 mRNA was very low in microglia/macrophages compared with that in astrocytes.

Astrocytes modulated PAI-1/tPA activity that promoted neurite outgrowth post stroke.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NINDS grants R01 NS66041 (YL) and R01 AG037506 (MC). We thank Cindi Roberts and Qinge Lu for their technical assistance.

References

- 1.Adibhatla RM, Hatcher JF. Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and matrix metalloproteinases in the pathogenesis of stroke: therapeutic strategies. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets. 2008;7:243–253. doi: 10.2174/187152708784936608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aldskogius H, Kozlova EN. Central neuron-glial and glial–glial interactions following axon injury. Prog. Neurobiol. 1998;55:1–26. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(97)00093-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bushong EA, Martone ME, Jones YZ, Ellisman MH. Protoplasmic astrocytes in CA1 stratum radiatum occupy separate anatomical domains. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:183–192. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-01-00183.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen J, Li Y, Wang L, Zhang Z, Lu D, Lu M, Chopp M. Therapeutic benefit of intravenous administration of bone marrow stromal cells after cerebral ischemia in rats. Stroke. 2001;32:1005–1011. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.4.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen J, Zhang C, Jiang H, Li Y, Zhang L, Robin A, Katakowski M, Lu M, Chopp M. Atorvastatin induction of VEGF and BDNF promotes brain plasticity after stroke in mice. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:281–290. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhandapani KM, Brann DW. Transforming growth factor-beta: a neuroprotective factor in cerebral ischemia. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2003;39:13–22. doi: 10.1385/CBB:39:1:13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Docagne F, Nicole O, Gabriel C, Fernandez-Monreal M, Lesne S, Ali C, Plawinski L, Carmeliet P, MacKenzie ET, Buisson A, Vivien D. Smad3-dependent induction of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in astrocytes mediates neuroprotective activity of transforming growth factor-beta1 against NMDA-induced necrosis. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2002;21:634–644. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2002.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frantz S, Hu K, Adamek A, Wolf J, Sallam A, Maier SK, Lonning S, Ling H, Ertl G, Bauersachs J. Transforming growth factor beta inhibition increases mortality and left ventricular dilatation after myocardial infarction. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2008;103:485–492. doi: 10.1007/s00395-008-0739-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gehrmann J, Matsumoto Y, Kreutzberg GW. Microglia: intrinsic immuneffector cell of the brain. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 1995;20:269–287. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(94)00015-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hailer NP. Immunosuppression after traumatic or ischemic CNS damage: it is neuroprotective and illuminates the role of microglial cells. Prog. Neurobiol. 2008;84:211–233. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herculano-Houzel S. The human brain in numbers: a linearly scaled-up primate brain. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2009;3:31. doi: 10.3389/neuro.09.031.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hosomi N, Lucero J, Heo JH, Koziol JA, Copeland BR, del Zoppo GJ. Rapid differential endogenous plasminogen activator expression after acute middle cerebral artery occlusion. Stroke. 2001;32:1341–1348. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.6.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kloss CU, Bohatschek M, Kreutzberg GW, Raivich G. Effect of lipopolysaccharide on the morphology and integrin immunoreactivity of ramified microglia in the mouse brain and in cell culture. Exp. Neurol. 2001;168:32–46. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kreutzberg GW. Microglia, the first line of defence in brain pathologies. Arzneimittelforschung. 1995;45:357–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krieglstein K, Strelau J, Schober A, Sullivan A, Unsicker K. TGF-beta and the regulation of neuron survival and death. J. Physiol. Paris. 2002;96:25–30. doi: 10.1016/s0928-4257(01)00077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lehrmann E, Kiefer R, Christensen T, Toyka KV, Zimmer J, Diemer NH, Hartung HP, Finsen B. Microglia and macrophages are major sources of locally produced transforming growth factor-beta1 after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. Glia. 1998;24:437–448. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(199812)24:4<437::aid-glia9>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin CH, Cheng FC, Lu YZ, Chu LF, Wang CH, Hsueh CM. Protection of ischemic brain cells is dependent on astrocyte-derived growth factors and their receptors. Exp. Neurol. 2006;201:225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakamura Y. Regulating factors for microglial activation. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2002;25:945–953. doi: 10.1248/bpb.25.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phinney DG, Kopen G, Isaacson RL, Prockop DJ. Plastic adherent stromal cells from the bone marrow of commonly used strains of inbred mice: variations in yield, growth, and differentiation. J. Cell. Biochem. 1999;72:570–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rahhal B, Heermann S, Ferdinand A, Rosenbusch J, Rickmann M, Krieglstein K. In vivo requirement of TGF-beta/GDNF cooperativity in mouse development: focus on the neurotrophic hypothesis. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2009;27:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shen LH, Xin H, Li Y, Zhang RL, Cui Y, Zhang L, Lu M, Zhang ZG, Chopp M. Endogenous tissue plasminogen activator mediates bone marrow stromal cell-induced neurite remodeling after stroke in mice. Stroke. 2011;42:459–464. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.593863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh S, Swarnkar S, Goswami P, Nath C. Astrocytes and microglia: responses to neuropathological conditions. Int. J. Neurosci. 2011;121:589–597. doi: 10.3109/00207454.2011.598981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Streit WJ. Microglial response to brain injury: a brief synopsis. Toxicol. Pathol. 2000;28:28–30. doi: 10.1177/019262330002800104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wirenfeldt M, Babcock AA, Vinters HV. Microglia – insights into immune system structure, function, and reactivity in the central nervous system. Histol. Histopathol. 2011;26:519–530. doi: 10.14670/HH-26.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xin H, Li Y, Shen LH, Liu X, Hozeska-Solgot A, Zhang RL, Zhang ZG, Chopp M. Multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells increase tPA expression and concomitantly decrease PAI-1 expression in astrocytes through the sonic hedgehog signaling pathway after stroke (in vitro study) J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31:2181–2188. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xin H, Li Y, Shen LH, Liu X, Wang X, Zhang J, Pourabdollah-Nejad DS, Zhang C, Zhang L, Jiang H, Zhang ZG, Chopp M. Increasing tPA activity in astrocytes induced by multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells facilitate neurite outgrowth after stroke in the mouse. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e9027. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zielasek J, Hartung HP. Molecular mechanisms of microglial activation. Adv. Neuroimmunol. 1996;6:122–191. doi: 10.1016/0960-5428(96)00017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]