Abstract

Background

Patient health information materials (PHIMs), such as leaflets and posters are widely used by family physicians to reinforce or illustrate information, and to remind people of information received previously. This facilitates improved health-related knowledge and self-management by patients.

Objective

This study assesses the use of PHIMs by patient. It also addresses their perception of the quality and the impact of PHIMs on the interaction with their physician, along with changes in health-related knowledge and self-management.

Methods

Questionnaire survey among patients of family practices of one town in Belgium, assessing: (1) the extent to which patients read PHIMs in waiting rooms (leaflets and posters) and take them home, (2) the patients’ perception of the impact of PHIMs on interaction with their physician, their change in health-related knowledge and self-management, and (3) the patients judgment of the quality of PHIMs.

Results

We included 903 questionnaires taken from ten practices. Ninety-four percent of respondents stated they read PHIMs (leaflets), 45% took the leaflets home, and 78% indicated they understood the content of the leaflets. Nineteen percent of respondents reportedly discussed the content of the leaflets with their physician and 26% indicated that leaflets allowed them to ask fewer questions of their physician. Thirty-four percent indicated that leaflets had previously helped them to improve their health-related knowledge and self-management. Forty-two percent reportedly discussed the content of the leaflets with others. Patient characteristics are of significant influence on the perceived impact of PHIMS in physician interaction, health-related knowledge, and self-management.

Conclusion

This study suggests that patients value health information materials in the waiting rooms of family physicians and that they perceive such materials as being helpful in improving patient–physician interaction, health-related knowledge, and self-management.

Keywords: Patient health information materials, interaction, patients, physician, Belgium

Introduction

Patient health information materials (PHIMs), such as leaflets and posters are widely used by diverse health organizations and professionals as part of patient education or health promotion efforts1–3 and in support of preventive, treatment, and compliance objectives.4,5 PHIMs can be used to reinforce or illustrate information given in a one-on-one setting, or can serve as references to remind people of information they received earlier. Some PHIMs are comprehensive in content and are designed for use during patient encounters, addressing detailed disease management topics. Other PHIMs summarize essential information for medication or diseases. Tailored and nontailored printed materials are widely available for helping individuals change health-related behaviors in reference to smoking, diet, physical activity, and screenings for cancer and cholesterol. Since the information provided in PHIMs needs to be scientifically sound, quality frameworks for the evaluation of PHIMs have recently been developed.6

PHIMs are not considered to be efficient substitutes for verbal communication between patient and family physician. However, there is evidence that patients do not retain the majority of information provided by their physicians due to lack of time during consultation.7 Patients can be overwhelmed by the amount of information they receive during that short time.8 Therefore, leaflets and other health information materials may enhance adherence and promote lifestyle modifications by complementing and reinforcing the verbal message.9 Observational studies of consultations have shown that patients do not always express all their concerns.10 PHIMs can be a low threshold means of information to patients that are too embarrassed to discuss concerns with their physician. They give patients the chance to read and digest information at their own speed, away from the stressful environment of the doctor’s office.3

Despite the wide availability of PHIMs on topics of medication and disease, their impact on patient-physician interaction, health-related knowledge and self-management has rarely been assessed. Little is known regarding patients’ perception of PHIMs made available in waiting rooms of family physicians.

In this study, we examined patients’ perceptions of what they read from the PHIMs in the waiting rooms of family physicians, their assessment of the quality and how they were helpful in improving patient–physician interaction, health knowledge, and managing their own health.

Methods

Selection of patients and practices

We invited all family practices (n = 82) in Halle, a town south of Brussels, Belgium to participate. During meetings of the peer group of local physicians, we explained the study protocol. We included all willing patients from all practices that provided PHIMs (leaflets and posters) in the waiting room. Physicians from the participating practices completed a short questionnaire recording the mean number patient encounters per month, the type of practice (group or solo), presence of administrative support staff in the practice, the type of patient contacts (appointments or not), as well as number of leaflets and posters in the waiting room and kind of display for leaflets.

Inclusion criteria for patients were: age 16 years or older and the ability to speak, read, and understand Dutch. Patients not fluent in Dutch were excluded because all practices were located in the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium and only Dutch PHIMs were available.

The recruitment of the family practices has some characteristics of a convenience sample, due to their willingness or availability to participate. However, the patients, who were the primary participants in this study were selected randomly by distributing the questionnaire to 100 consecutive patients.

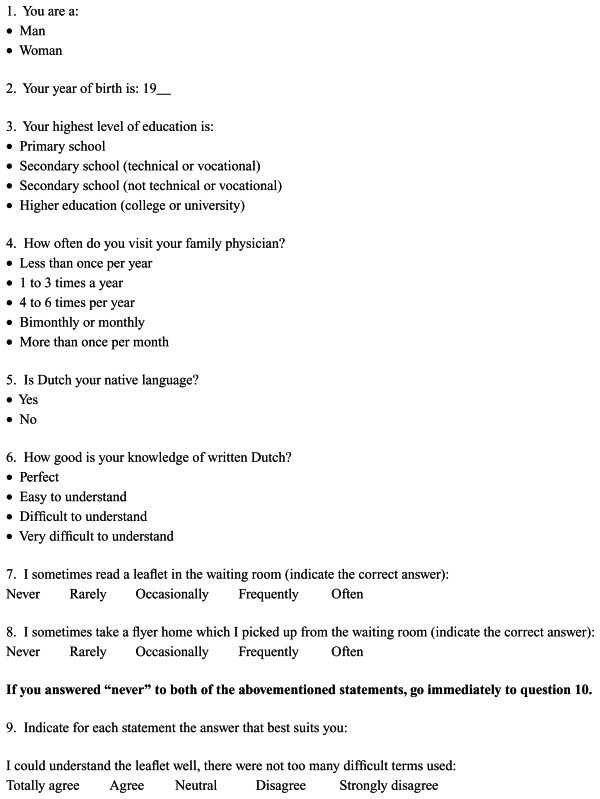

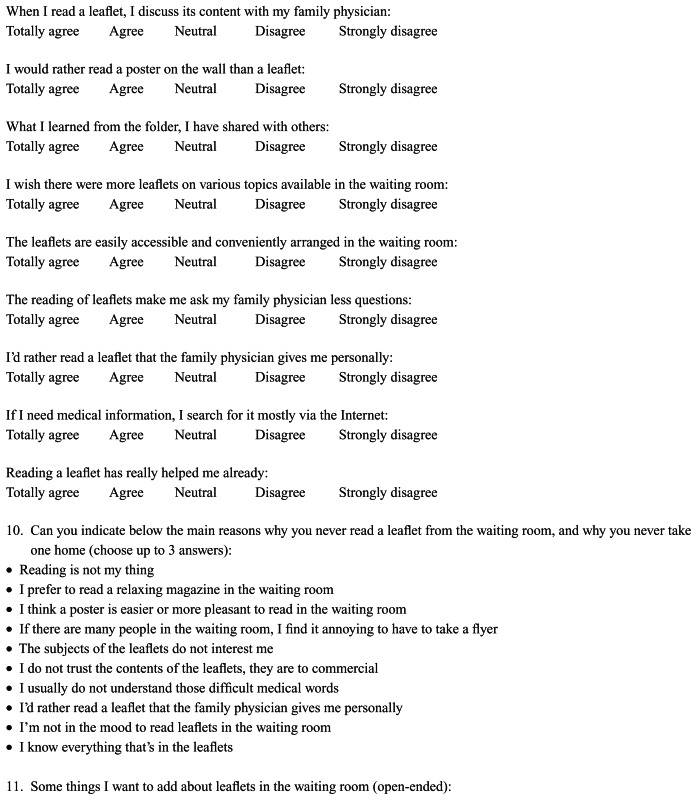

Questionnaire

We developed a questionnaire for the purpose of this study. It consisted of three parts. The first part assessed the use of PHIMs, with “Use of PHIMs” implemented as: “reading and taking the leaflets home”. The second part assessed patient’s perceptions of the material’s quality, with “ Quality of PHIMs” implemented as “perceived intelligibility of the leaflets and convenience of display and access to materials”. The third part assessed how patients perceived the impact of the PHIMs, with “Impact of PHIMs” implemented as “perceived effectiveness of materials in terms of reported physician interaction, discussing content with others and improving one’s health-related knowledge and self-management”. The assessment was based on statements answered on a Five-point Likert scale (totally agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree).

The questionnaire was pre-tested by four family physicians and ten patients allowing for further refinement.

Each practice received 100 questionnaires. To prevent selection bias the questionnaire was handed to consecutive patients during regular consultations by the physician. Patients were asked to fill out the anonymous questionnaire before the start or at the end of the consultation and to drop the questionnaire in a sealed box. Patients completed the questionnaire in the waiting room, with the opportunity to look at the available PHIMs. Patients who indicated not reading or taking a leaflet home were asked to indicate the reasons for their disinterest.

Processing of statistics

Analysis and statistical processing of the results was performed using Statistics Package for the Social Sciences version 19.0 (SPSS®; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). We used backward logistic regression to analyze respondent and practice characteristics. The following patients’ variables were included in the equation: gender, age, highest level of education (primary school, vocational secondary school, high school, or university), frequency of contact with family physician per year (<1, 1–3, 4–6, 7–12, >12), native language, along with assessing whether they read leaflets, took leaflets home, and/or asked physician for information. The included practices’ variables were: number of available leaflets in the waiting room and display of leaflets.

Results

Participants

Ten practices (three groups and seven solo) of the 82 invited practices participated in the study with a mean of 350 patient contacts per physician per month (Table 1). In total, 903 questionnaires were completed representing a response rate of 90%. The mean age of females was 47.5 years and for males it was 51.0 years (P < 0.005) with 62% female participation. A total of 16% of the respondents held a diploma from primary school, 54% from secondary school, and 28% with some college or university. Younger patients held higher degrees compared to older patients (P < 0.005); 31% of the respondents indicated searching the internet for medical information while 24% responded “neutral” to this item and 34% never looked for medical information on the internet. Eleven percent did not respond to this question.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participating practices

| Practice | Type of practice | Type of consultations | Patient-encounters/physician/month | Administrative support | Number of leaflets in waiting room | Number of posters in waiting room | Display of leaflets in waiting room |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Solo | Never on appointment | 600 | Spouse | 3 | 6 | Leaflet holder |

| 2 | Group | Mixed but mainly on appointment | 300 | Secretary | 16 | 27 | Reserved furniture or rack for leaflets |

| 3 | Group | Mixed with and without appointment | 250 | None | 29 | 22 | Reserved furniture or rack for leaflets |

| 4 | Solo | Mixed but mainly not on appointment | 450 | Spouse | 13 | 20 | Other |

| 5 | Solo | Only on appointment | 700 | Tele secretary | 4 | 0 | Leaflet holder |

| 6 | Solo | Mixed but mainly not on appointment | 250 | None | 12 | 6 | Reserved furniture or rack for leaflets |

| 7 | Solo | Mixed but mainly not on appointment | 450 | Student employee | 12 | 12 | Leaflet holder |

| 8 | Solo | Mixed but mainly not on appointment | 350 | None | 2 | 5 | Other |

| 9 | Association | Mixed but mainly on appointment | 600 | None | 19 | 0 | Reserved furniture or rack for leaflets |

| 10 | Group | Mixed but mainly on appointment | 350 | None | 12 | 12 | Reserved furniture or rack for leaflets |

Five percent of the respondents visited their physician several times a month, 24% on a monthly or bi-monthly basis, 30% one to three times per year, and 36% four to six times per year. Four percent of the respondents indicated visiting their physician less than once a year. Older patients reported a higher number of physician contacts compared to younger patients (P < 0.005).

Type and number of PHIMs

A mean of 12 leaflets (standard deviation: 2–29) were available to patients in the waiting rooms. Group practices provided a significantly higher number of leaflets than solo practices (19 versus 8; P = 0.05).

Use of PHIMs

A total of 852 respondents (94%) indicated reading the PHIMs (leaflets), with 82% doing so regularly, 12% rarely, and 6% never. One percentage of respondents did not complete the question regarding reading PHIMs. Reasons for never reading leaflets were: a preference for reading other materials (magazines), a preference for leaflets or posters provided by the physician him/herself and lastly having no interest in reading while in the waiting room.

Of respondents who indicated reading the leaflets, 45% also take them home regularly, 20% did so rarely, and 33% never. Two percent of respondents did not complete the question on frequency of taking leaflets home.

Thirteen percent of the respondents said they would prefer a higher number of leaflets in the waiting room, while 39% considered the number of leaflets provided sufficient, and 35% were neutral to this item. The number of nonresponders in this question was 13%. Females are more interested in reading and taking leaflets home than males (P = 0.003 and P = 0.001, respectively; Table 2). Patients who consult their physician on a regular basis are more likely to take leaflets home compared to patients who visit their physician on an irregular basis (P = 0.021). Patients of physicians who organize their practice with scheduled appointments indicated reading more leaflets than patients of physicians who work without appointments (P = 0.002). A higher number of leaflets were taken home by patients of physicians with a greater number of contacts per month, compared to patients of physicians with fewer patient contacts (P = 0.003; Table 3).

Table 2.

Logistic regression on the use of PHIMs with patients-related co-variates

| P-value | OR | 95% CI For OR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Reading leaflets | ||||

| Gender (male compared to female) | 0.003 | 1.702 | 1.193 | 2.427 |

| Taking leaflets home | ||||

| Gender (male compared to female) | <0.001 | 1.727 | 1.295 | 2.302 |

| Frequency of contact with family physician | 0.021 | 1.436 | 1.057 | 1.949 |

Notes: Logistic regression including the following covariates: gender (male/female), age groups (per 10 years), educational level (primary school, technical secondary school, general secondary school, high-school, or university), frequency of contact with family physician per year (<1, 1–3, 4–6, 7–12, >12), native language Dutch, taking leaflets home, number of available leaflets, reading leaflets, display of leaflets, asking for information.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; PHIM, patient health information materials.

Table 3.

Logistic regression on the use of PHIMs with practice-related co-variates

| P-value | OR | 95% CI for OR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Reading leaflets | ||||

| Type of contacts (appointments versus others) | 0.002 | 0.388 | 0.212 | 0.709 |

| Taking leaflets home | ||||

| Mean number of patient contacts a month | 0.003 | 1.774 | 1.209 | 2.604 |

| Display of leaflets | 0.004 | 1.791 | 1.210 | 2.650 |

Notes: Logistic regression including the following practice-related covariates: the mean number contacts per month, the type of practice (group or solo), administrative support in the practice, the type of patient contacts (appointments or not), the number of leaflets and posters in the waiting room and the kind of display for leaflets.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; PHIM, patient health information materials.

Patients’ perceptions of quality of PHIMs

Seventy nine percent of respondents stated in general they understood the content of the leaflets (answered “agree” to the statement); while 2% stated they did not understand the content (“do not agree”). Nine percent answered “neutral”. The number of patients who think the leaflets were conveniently displayed in the waiting room was 73% (“agree”), while 5% considered the display to be inconvenient (“do not agree”), and 12% answered “neutral” on this statement.

Individual patient characteristics of significant importance for his/her perception of quality of PHIMS are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Influence of patient and practice characteristics on patients’ perceptions with quality and impact of PHIMs

| P-value | OR | 95% CI for OR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Lower | Upper | |||

| I understand the content of the leaflets | ||||

| Taking leaflets home | 0.063 | 4.391 | 0.923 | 20.889 |

| The leaflets are conveniently displayed in the waiting room | ||||

| Educational level | <0.001 | 0.248 | 0.115 | 0.534 |

| Reading leaflet | 0.012 | 3.070 | 1.277 | 7.380 |

| Frequency of contact with family physician | 0.050 | 3.715 | 0.999 | 13.821 |

| Asking for information | 0.062 | 3.550 | 0.936 | 13.464 |

| Display for leaflets | 0.119 | 2.512 | 0.789 | 8.004 |

| I discuss the content of the leaflets with my physician | ||||

| Age-groups | <0.001 | 3.390 | 2.348 | 4.895 |

| Gender (male compared to female) | 0.046 | 1.978 | 1.013 | 3.861 |

| Educational level | <0.001 | 0.239 | 0.121 | 0.474 |

| Frequency of contact with family physician | 0.063 | 1.879 | 0.968 | 3.649 |

| Reading leaflets | 0.053 | 3.110 | 0.984 | 9.834 |

| Taking leaflets home | <0.001 | 3.711 | 1.925 | 7.154 |

| What I learned from the leaflet, I discuss with/tell to others | ||||

| Gender (male compared to female) | 0.034 | 1.782 | 1.044 | 3.043 |

| Reading leaflets | <0.001 | 4.329 | 2.135 | 8.775 |

| Taking a leaflet home | 0.001 | 2.589 | 1.474 | 4.547 |

| Number of leaflets in waiting room | 0.004 | 0.427 | 0.239 | 0.763 |

| Frequency of contact with family physician | 0.050 | 0.587 | 0.344 | 1.001 |

| I would rather read a poster on the wall than a leaflet | ||||

| Reading leaflets | 0.012 | 0.212 | 0.063 | 0.715 |

| Taking leaflets | 0.084 | 0.639 | 0.384 | 1.062 |

| Number of leaflets in waiting room | 0.026 | 1.812 | 1.072 | 3.062 |

| Frequency of contact with family physician | 0.006 | 2.065 | 1.229 | 3.469 |

| Leaflets make me ask less questions of my family physician | ||||

| Educational level | <0.001 | 0.405 | 0.244 | 0.672 |

| Reading leaflet | 0.020 | 2.426 | 1.150 | 5.118 |

| Frequency of contact with family physician | 0.001 | 2.125 | 1.369 | 3.298 |

| Leaflets have previously helped me to improve my health-related knowledge and self-management | ||||

| Age-groups | 0.075 | 0.732 | 0.519 | 1.032 |

| Educational level | 0.030 | 0.507 | 0.274 | 0.937 |

| Reading leaflets | <0.001 | 8.280 | 3.199 | 21.436 |

| Taking leaflets home | 0.070 | 1.740 | 0.957 | 3.167 |

| Display of leaflets | 0.004 | 2.424 | 1.329 | 4.419 |

Notes: Logistic regression including the following covariates: gender (male/female), age-groups (per 10 years), educational level (primary school, technical secondary school, general secondary school, high-school or university), frequency of contact with family physician per year (<1, 1–3, 4–6, 7–12, >12), native language Dutch, taking leaflets home, number of available leaflets, reading leaflets, display of leaflets, asking for information.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; PHIM, patient health information materials.

Patients’ perceptions of impact of PHIMs

Nineteen percent of respondents stated that in general they discuss the content of the leaflets with their physician (“agree”), while 27% did not agree, and 41% answered “neutral” (Table 5).

Table 5.

Patients’ perceptions with quality and impact of PHIMs

| Agree (%) | Neutral (%) | Not agree (%) | Not completed (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients’ perceptions with quality of PHIMs (n = 852) | ||||

| I understand the content of the leaflets | 78.8 | 9.0 | 1.9 | 10.3 |

| The leaflets are conveniently displayed in the waiting room | 73.2 | 11.6 | 4.9 | 10.2 |

| Patients’ perceptions with impact of PHIMs (n = 852) | ||||

| I discuss the content of the leaflets with my family physician | 19.0 | 40.8 | 26.8 | 13.4 |

| Leaflets make me ask less questions of my family physician | 26.2 | 30.5 | 32.4 | 10.9 |

| What I learned from the leaflet, I discuss with/tell to others | 42.4 | 30.8 | 14.9 | 12.0 |

| Leaflets have previously helped me to improve my health-related knowledge and self-management | 34.2 | 40.7 | 12.7 | 12.3 |

Abbreviation: PHIM, patient health information materials.

The percentage of patients that agreed with the statement “leaflets make them ask fewer questions of their physician” was 26%, while 32% did not agree, and 31% answered “neutral” on this item (Table 5).

Patient characteristics that are of significant importance to the perception of the impact of PHIMS on patient-physician interaction are presented in Table 4. The characteristics of patients “discussing content of leaflets with physician” are: gender (female, P = 0.046), age (elderly patients, P = 0.001), educational level (patients with a lower educational degree, P < 0.001), and took leaflets home (P < 0.001). The characteristics that lead to “asking fewer questions to my physician” are: educational degree (lower educational degree, P < 0.001) and reading the leaflets (P = 0.020).

Thirty-four percent of respondents stated that leaflets had previously helped them to improve their health-related knowledge and self-management (“agree”), while 13% who did not agree and 41% had no opinion (“neutral”). Patient characteristics that are of significant importance for the perception of the impact of PHIMS on health-related knowledge and self-management are: age (elderly patients, P = 0.075), educational degree (P = 0.030) and reading the leaflets (P < 0.001). The content of the “leaflets discussed with others” by 42% of the respondents, while 15% do not discuss leaflets with others. Thirty-one percent have a “neutral” stance towards this item (Table 5). Patient characteristics improving “discussing the content of the leaflets with others” are: gender (female, P = 0.034), reading the leaflets (P < 0.001) and taking the leaflets home (P = 0.001; Table 4).

Discussion

This study has demonstrated that patients value health information materials available in the waiting rooms of family physicians. A substantial number of patients consider reading leaflets as being helpful in improving interaction with their physician and in enhancing their health-related knowledge and self-management. This finding is in line with other, albeit few, existing studies that have evaluated patients’ perceptions of health information materials.11 However, only very few papers report on the impact of PHIMs on patient–physician interaction, change in health-related knowledge, and self-management. Therefore, it was impossible to extensively discuss the differences between this study and previous similar studies in an adequate manner.

Knowing patients’ perceptions of PHIMs could be of significant importance because they are an important part of patient empowerment. Positive patient perceptions are considered to be an outcome of patient empowerment.12 Patient empowerment refers to a range of interventions (eg, improved doctor–patient communication), but is also used to refer to specific antecedents (eg, health literacy) and outcomes (eg, self-efficacy).13 From this point of view, the results from our study suggest PHIMs to have had a positive impact on patient empowerment, with female patients more responsive to empowerment strategies compared to males. This is in line with other results that studied health behaviors in males and females.14,15

Another interesting finding from this study is that group practices provide significantly more variety of health information materials to patients than solo practices. A greater focus on preventive aspects of care in group practices might explain this result. Data from this study show that the intensity of patient contacts influences the interest that patients have in PHIMs. Patients who consult their physician on a regular basis reported to take the leaflets home more often. In addition, a higher number of leaflets were taken home by patients from physicians who have a high number of patient contacts per month.

There is a known relationship between the age of patients, the number of patient-encounters, and the number of chronic conditions. This could explain why, in our study, older patients discuss the content of leaflets more frequently with their physician and why older patients find leaflets more helpful for improving their health-related knowledge and self-management. Available evidence supports the role of the family physician as a key player in any chronic illness management strategy,16–18 as he/she has an essential role in chronic disease prevention, identification, and management.19 The patient’s behavior in the patient–physician relationship is influenced by prior life experiences, current life situation, resources, and explanatory models of illness.20–24 Family physicians are crucial in influencing and changing patient behavior.

For an important proportion of the statements, the “neutral” answer was given. We assume that this “neutral” answer was given when participants neither agreed nor disagreed. However, it is likely that this answer was chosen by participants unable to formulate an opinion, and to them the “neutral” answer was the only appropriate option. For that reason, in future research, our questionnaire needs adapting, for example by adding an option “don’t know” at the end of the Likert scales.

Limitations of the study

Limitations of this study are fourfold. First, data on the number of patients who refused to participate and their reasons for refusal were not recorded in order to minimize time efforts for physicians from the participating practices.

Second, the study population may not be representative of the Belgian population as a whole. Respondents were almost all Caucasians living in favorable socioeconomic environments and a significant number had higher education degrees. With only a small proportion of respondents (2%) indicating problems in understanding the content of the leaflets and no less than 31% indicating they search the internet for medical information, our findings are in contrast with other studies that consider health illiteracy a hidden epidemic25 and a marked problem among older adults.8 The Institute of Medicine defines health literacy as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make an appropriate health decision”.26 Health literacy has an effect on a person’s ability to make sound health decisions about his or her health care, and it has a significant impact on the effectiveness of health education efforts, including the use of PHIMs. Patients with limited health literacy are less likely to use preventive health services such as vaccinations and mammograms, and more likely to improperly read medication dosing instructions and referral paperwork.27,28 For the health and safety of patients, the gap between the literacy of clinicians and that of their patients must be bridged to achieve effective communication and understanding.29

A third limitation is that the study was based on broad, self-reported patient perceptions of the usefulness, quality, and impact of PHIMs. We defined these issues rather broadly. For example, the “use of PHIMs” was evaluated as having read the materials and taking them home. We did not analyze to what extent patients’ perceptions on the impact of PHIMs corresponded with other measures and improvements in patient–physician interaction, health-related knowledge, and self-management of their illness(es). Evidence of the effectiveness of PHIMs has shown that these materials are effective only when used as part of an overall patient education strategy. Simply handing the patient a leaflet is not enough to improve comprehension or induce lifestyle adaptations. Educational materials should be used when a physician is focusing on a specific point of care that needs further reinforcement. The relative high number of visits in patients might in part explain the positive perceptions of patients. Regular contact and support from their family physician might have been perceived in patients as a complement to the information provided in the PHIMs.

Finally, although we tried to avoid selection bias within the participating practices by asking them to include consecutive patients, occasionally forgetting to hand out the questionnaire, or making an unconscious decision that a patient can’t read or would be unwilling to participate, may have led to minor additional bias.

Future research

Future research into the use of PHIMs is needed to evaluate ease of readability, comprehension, relevance, usefulness in coping with or managing their diseases/conditions. These studies should also focus on the PHIMs personal relevance to the patient, since this could be a major predictor of use, along with perceived susceptibility and severity of the disease.

Conclusion

This study suggests that patients’ value health information materials in waiting rooms of family physicians and that they perceive such materials as being helpful in improving physician interaction, health-related knowledge, and self-management. More studies with a more powerful methodology and firmer endpoints are needed to confirm these findings.

Supplementary material (translated from Dutch)

Questionnaire

With this questionnaire we would like to know your opinion about the leaflets in the waiting room. The answers to questionnaire are anonymous. As a patient, there are absolutely no consequences to completing or answering any of the questions herein. Please deposit the completed questionnaire in the appropriate box. Do not forget to fill in the reverse side of the questionnaire!

Thank you very much!

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully thank all participating patients and family physicians.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Boyde M, Turner C, Thompson DR, Stewart S. Educational interventions for patients with heart failure: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2011;26(4):E27–E35. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e3181ee5fb2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown JP, Clark AM, Dalal H, Welch K, Taylor RS. Effect of patient education in the management of coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Eur J Prev Cardiol. doi: 10.1177/2047487312449308. Epub May 22, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taggart J, Williams A, Dennis S, et al. A systematic review of interventions in primary care to improve health literacy for chronic disease behavioral risk factors. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-13-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gal I, Prigat A. Why organizations continue to create patient information leaflets with readability and usability problems: an exploratory study. Health Educ Res. 2005;20(4):485–493. doi: 10.1093/her/cyh009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedman AJ, Cosby R, Boyko S, Hatton-Bauer J, Turnbull G. Effective teaching strategies and methods of delivery for patient education: a systematic review and practice guideline recommendations. J Cancer Educ. 2011;26(1):12–21. doi: 10.1007/s13187-010-0183-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garner M, Ning Z, Francis J. A framework for the evaluation of patient information leaflets. Health Expect. 2012;15(3):283–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2011.00665.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coulter A. Evidence based patient information is important, so there needs to be a national strategy to ensure it. BMJ. 1998;317(7153):225–226. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7153.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tarn DM, Heritage J, Paterniti DA, Hays RD, Kravitz RL, Wenger NS. Physician communication when prescribing new medications. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1855–1862. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clerehan R, Buchbinder R, Moodie J. A linguistic framework for assessing the quality of written patient information: its use in assessing methotrexate information for rheumatoid arthritis. Health Educ Res. 2005;20(3):334–344. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barry CA, Bradley CP, Britten N, Stevenson FA, Barber N. Patients’ unvoiced agendas in general practice consultations: qualitative study. BMJ. 2000;320(7244):1246–1250. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tarn DM, Mattimore TJ, Bell DS, Kravitz RL, Wenger NS. Provider views about responsibility for medication adherence and content of physician-older patient discussions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(6):1019–1026. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03969.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson RM, Funnell MM. Patient empowerment: reflections on the challenge of fostering the adoption of a new paradigm. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;57(2):153–157. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loukanova S, Molnar R, Bridges JF. Promoting patient empowerment in the healthcare system: highlighting the need for patient-centered drug policy. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2007;7(3):281–289. doi: 10.1586/14737167.7.3.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khaw KT, Wareham N, Bingham S, Welch A, Luben R, Day N. Combined impact of health behaviours and mortality in men and women: the EPIC-Norfolk prospective population study. PLoS Med. 2008;5(1):e12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rom Korin M, Chaplin WF, Shaffer JA, Butler MJ, Ojie MJ, Davidson KW. Men’s and women’s health beliefs differentially predict coronary heart disease incidence in a population-based sample. Health Educ Behav. 2013;40(2):231–239. doi: 10.1177/1090198112449461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engström S, Foldevi M, Borgquist L. Is general practice effective? A systematic literature review. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2001;19(2):131–144. doi: 10.1080/028134301750235394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris MF, Zwar NA. Care of patients with chronic disease: the challenge for general practice. Med J Aust. 2007;187(2):104–107. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin CM. Chronic disease and illness care: adding principles of family medicine to address ongoing health system redesign. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53(12):2086–2091. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McIsaac WJ, Fuller-Thomson E, Talbot Y. Does having regular care by a family physician improve preventive care? Can Fam Physician. 2001;47:70–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ban N. Continuing care of chronic illness: Evidence-based medicine and narrative-based medicine as competencies for patient-centered care. Asia Pac Fam Med. 2003;2(2):74–76. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dubois CA, Singh D, Jiwani I. The human resource challenge in chronic care. In: Nolte E, McKee M, editors. Caring for People with Conditions: A Health System Perspective. Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2008. pp. 134–171. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saultz JW, Lochner J. Interpersonal continuity of care and care outcomes: a critical review. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(2):159–166. doi: 10.1370/afm.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gunn JM, Palmer VJ, Naccarella L, et al. The promise and pitfalls of generalism in achieving the Alma-Ata vision of health for all. Med J Aust. 2008;189(2):110–112. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scott JG, Cohen D, Dicicco-Bloom B, Miller WL, Stange KC, Crabtree BF. Understanding healing relationships in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(4):315–322. doi: 10.1370/afm.860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gazmararian JA, Beditz K, Pisano S, Carreón R. The development of a health literacy assessment tool for health plans. J Health Commun. 2010;15( Suppl 2):93–101. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.499986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nielsen-Bohlman L, Pantzer AM, Kindig DA. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gazmararian J, Jacobson KL, Pan Y, Schmotzer B, Kripalani S. Effect of a pharmacy-based health literacy intervention and patient characteristics on medication refill adherence in an urban health system. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44(1):80–87. doi: 10.1345/aph.1M328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mbaezue N, Mayberry R, Gazmararian J, Quarshie A, Ivonye C, Heisler M. The impact of health literacy on self-monitoring of blood glucose in patients with diabetes receiving care in an inner-city hospital. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102(1):5–9. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30469-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davis TC, Wolf MS. Health literacy: implications for family medicine. Fam Med. 2004;36(8):595–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]