Abstract

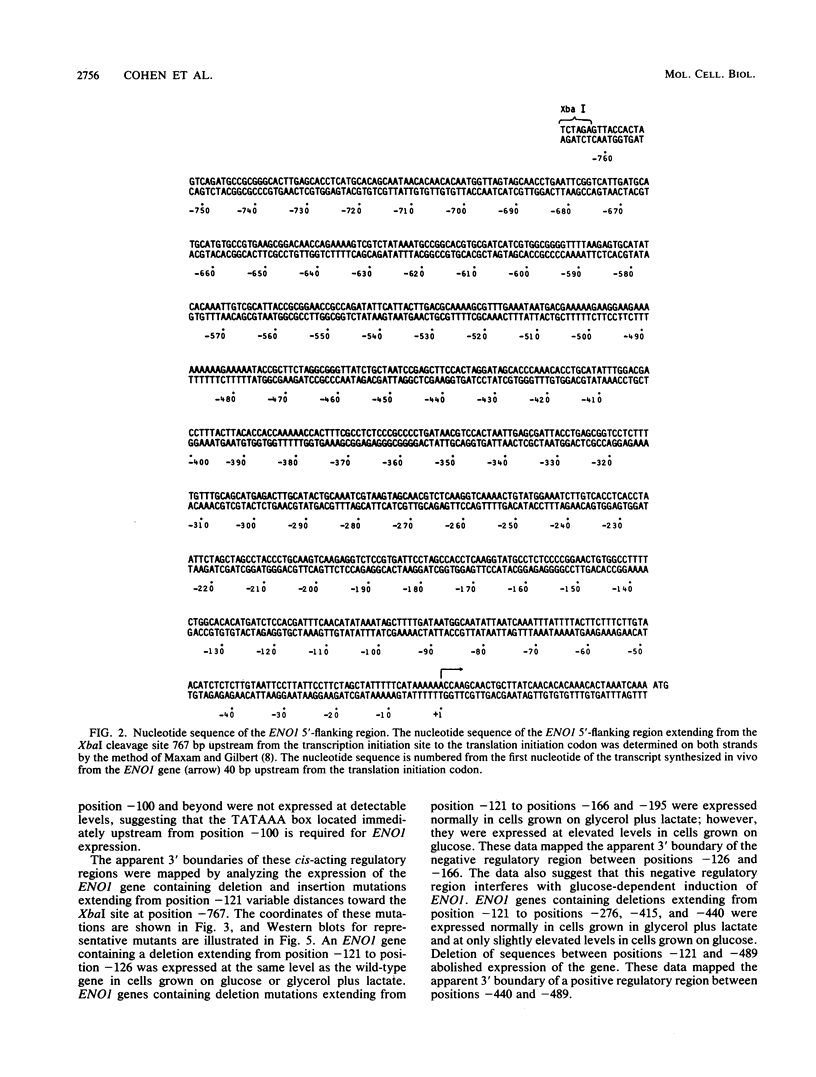

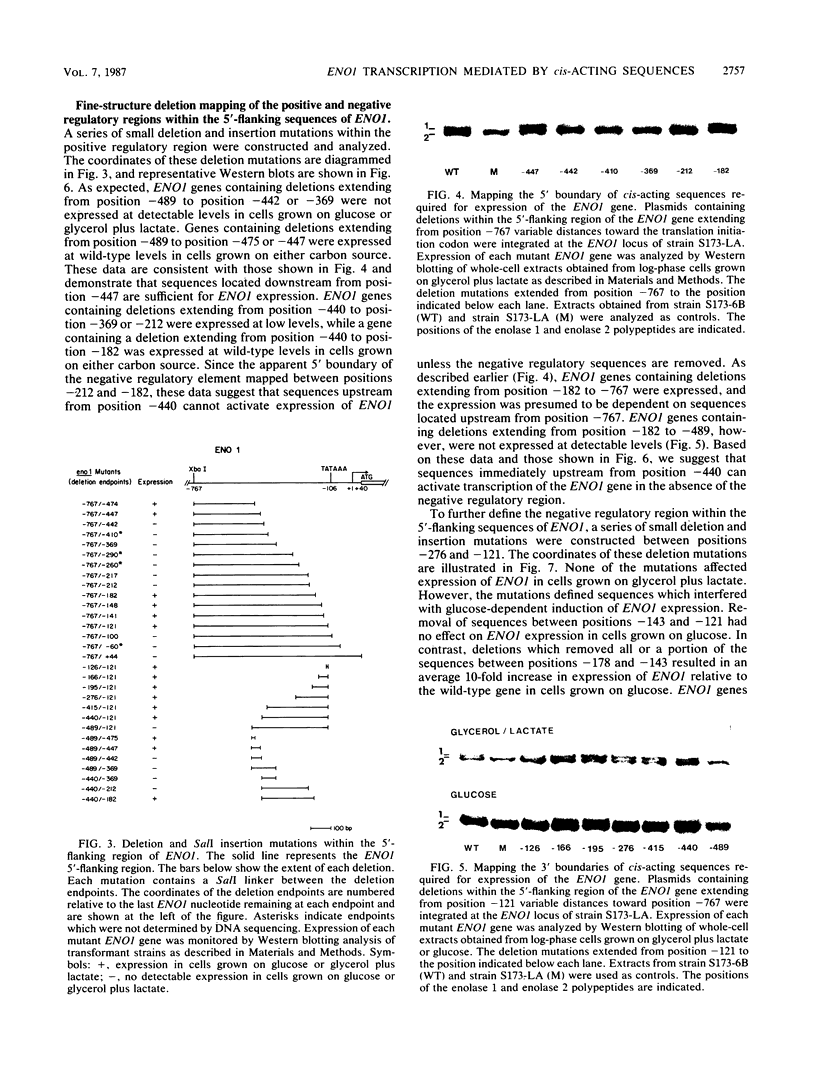

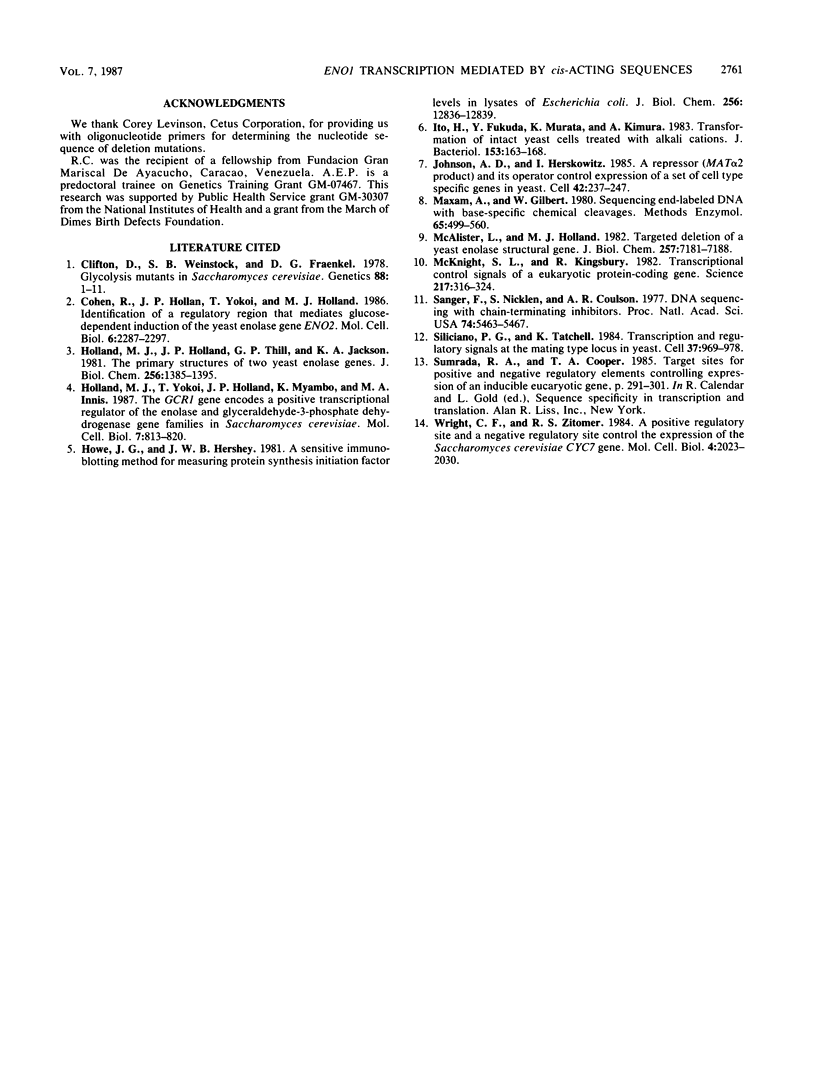

There are two enolase genes, ENO1 and ENO2, per haploid yeast genome. Expression of the ENO1 gene is quantitatively similar in cells grown on glucose or gluconeogenic carbon sources. In contrast, ENO2 expression is induced more than 20-fold in cells grown on glucose as the carbon source. cis-Acting regulatory sequences were mapped within the 5'-flanking region of the constitutively expressed yeast enolase gene ENO1. A complex positive regulatory region was located 445 base pairs (bp) upstream from the transcriptional initiation site which was required for ENO1 expression in cells grown on glycolytic or gluconeogenic carbon sources. A negative regulatory region was located 160 bp upstream from the transcriptional initiation site. Sequences required for the function of this negative regulatory element were mapped to a 38-bp region. Deletion of all or a portion of these latter sequences permitted glucose-dependent induction of ENO1 expression that was quantitatively similar to that of the glucose-inducible ENO2 gene. The negative regulatory element therefore prevents glucose-dependent induction of the ENO1 gene. Hybrid 5'-flanking regions were constructed which contained the upstream regulatory sequences of one enolase gene fused at a site upstream from the TATAAA box in the other enolase gene. Analysis of the expression of enolase genes containing these hybrid 5'-flanking region showed that the positive regulatory regions of ENO1 and ENO2 were functionally similar, as were the regions extending from the TATAAA boxes to the initiation codons. Based on these studies, we conclude that the negative regulatory element plays the critical role in maintaining the constitutive expression of the ENO1 structural gene in cells grown on glucose or gluconeogenic carbon sources.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Clifton D., Weinstock S. B., Fraenkel D. G. Glycolysis mutants in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1978 Jan;88(1):1–11. doi: 10.1093/genetics/88.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen R., Holland J. P., Yokoi T., Holland M. J. Identification of a regulatory region that mediates glucose-dependent induction of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae enolase gene ENO2. Mol Cell Biol. 1986 Jul;6(7):2287–2297. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.7.2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland M. J., Holland J. P., Thill G. P., Jackson K. A. The primary structures of two yeast enolase genes. Homology between the 5' noncoding flanking regions of yeast enolase and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase genes. J Biol Chem. 1981 Feb 10;256(3):1385–1395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland M. J., Yokoi T., Holland J. P., Myambo K., Innis M. A. The GCR1 gene encodes a positive transcriptional regulator of the enolase and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene families in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1987 Feb;7(2):813–820. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.2.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe J. G., Hershey J. W. A sensitive immunoblotting method for measuring protein synthesis initiation factor levels in lysates of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1981 Dec 25;256(24):12836–12839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito H., Fukuda Y., Murata K., Kimura A. Transformation of intact yeast cells treated with alkali cations. J Bacteriol. 1983 Jan;153(1):163–168. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.1.163-168.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A. D., Herskowitz I. A repressor (MAT alpha 2 Product) and its operator control expression of a set of cell type specific genes in yeast. Cell. 1985 Aug;42(1):237–247. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80119-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxam A. M., Gilbert W. Sequencing end-labeled DNA with base-specific chemical cleavages. Methods Enzymol. 1980;65(1):499–560. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(80)65059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAlister L., Holland M. J. Targeted deletion of a yeast enolase structural gene. Identification and isolation of yeast enolase isozymes. J Biol Chem. 1982 Jun 25;257(12):7181–7188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight S. L., Kingsbury R. Transcriptional control signals of a eukaryotic protein-coding gene. Science. 1982 Jul 23;217(4557):316–324. doi: 10.1126/science.6283634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger F., Nicklen S., Coulson A. R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977 Dec;74(12):5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siliciano P. G., Tatchell K. Transcription and regulatory signals at the mating type locus in yeast. Cell. 1984 Jul;37(3):969–978. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90431-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright C. F., Zitomer R. S. A positive regulatory site and a negative regulatory site control the expression of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae CYC7 gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1984 Oct;4(10):2023–2030. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.10.2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]