Abstract

CaV1.2 sparklets are local elevations in intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) resulting from the opening of a single or small cluster of voltage-gated, dihydropyridine-sensitive CaV1.2 channels. Activation of CaV1.2 sparklets is an early event in the signaling cascade that couples membrane depolarization to contraction (i.e., excitation-contraction coupling) in cardiac and arterial smooth muscle. Here, we review recent work on the molecular and biophysical mechanisms that regulate CaV1.2 sparklet activity in these cells. CaV1.2 sparklet activity is tightly regulated by a cohort of protein kinases and phosphatases that are targeted to specific regions of the sarcolemma by the anchoring protein AKAP150. We discuss a model for the local control of Ca2+ influx via CaV1.2 channels in which a signaling complex formed by AKAP79/150, protein kinase C, protein kinase A, and calcineurin regulates the activity of individual CaV1.2 channels and also facilitates the coordinated activation of small clusters of these channels. This results in amplification of Ca2+ influx, which strengthens excitation-contraction coupling in cardiac and vascular smooth muscle.

Introduction

On average, a heart will beat about 3 billion times during the lifetime of a human. With each beat, the heart pumps blood to the pulmonary and systemic circulation. To achieve this feat, the heart must contract in a highly coordinated fashion that allows for the sequential activation of its atria and ventricles. Ca2+ influx via CaV1.2 channels during the action potential (AP) serves as the signal that triggers contraction in atrial and ventricular myocytes. The chain of events that links membrane depolarization to the increase in intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) that triggers contraction is known as excitation-contraction (EC) coupling [1]. The fidelity of EC coupling in the heart is remarkable, with every AP triggering a [Ca2+]i transient and contraction [2].

The work of the heart would be futile if it were not for arteries, which deliver the blood pumped by the left ventricle to each organ in the body. Blood flow through the vasculature depends on the pressure generated by the contraction of the ventricles and the systemic resistance, which is determined by blood vessel diameter. Ultimately, the contractile state of the smooth muscle lining the walls of arteries controls arterial caliber and hence blood flow [3]. Like cardiac myocytes, arterial myocyte contraction is controlled by changes in membrane potential and Ca2+ influx via CaV1.2 channels.

Although CaV1.2 channels play a critical role in cardiac and smooth muscle EC coupling [4, 5], the mechanisms by which their activation increases global [Ca2+]i and initiates contraction are fundamentally different. In cardiac cells, activation of CaV1.2 channels during the AP allows a small amount of Ca2+ to enter the cytosol [4]. These Ca2+ influx events, which we are calling a “CaV1.2 sparklet” to distinguish them from sparklets produced by other Ca2+-permeable channels (e.g. TRPV4, AChRs, and CaV2.2 and CaV1.3 Ca2+ channels), activate closely apposed ryanodine receptors (RyRs) located in the junctional sarcoplasmic reticulum (jSR) via the mechanism of Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR) [4, 6]. Accordingly, CICR amplifies the initial Ca2+ entry event, causing a global elevation in [Ca2+]i that triggers contraction.

Unlike cardiac myocytes, an AP is not required for the activation of CaV1.2 channelsin vascular smooth muscle. Rather, increases in intravascular pressure cause a graded depolarization of the sarcolemma of vascular smooth muscle that activate CaV1.2 sparklets [7, 8]. In these cells, CaV1.2 sparklets are directly responsible for cell-wide increases in global [Ca2+]i that activates the contractile machinery during EC coupling [8].

Optical recording of CaV1.2 sparklets have revealed interesting features about the channels underlying these events in cardiac and vascular smooth muscle cells [4, 9, 10]. First, the activity of CaV1.2 channels varies throughout the sarcolemma of cardiac and vascular smooth muscle. Second, the CaV1.2 channels form clusters and can gate coordinately along the sarcolemmal of these cells [10–13]. In this review, we discuss the mechanisms underlying heterogeneous CaV1.2 channel activity, their cooperative activation, and the functional implications of these observations on EC coupling strength and stability under physiological and pathological conditions in cardiac and vascular smooth muscle.

Molecular composition and spatial organization of CaV1.2 channels in cardiac and vascular smooth muscle

CaV1.2 channels are heteromeric proteins composed of a transmembrane, pore-forming α1C (CaV1.2) and accessory β, α2δ-1 and, in many cells, γ subunits [14]. The expression of the auxiliary β(1–3) subunit has been associated with enhanced channel trafficking and expression. This subunit also regulates the voltage dependencies of CaV1.2 channels [15]. β2 and β3 subunits are the predominant β subunits expressed in ventricular and vascular smooth muscle cells, respectively. Recently, the transmembrane α2δ(1) was identified as being critical for functional trafficking of CaV1.2 α1 subunits to the plasma membrane in vascular smooth muscle [16].

The α1C subunit contains four highly conserved repeat regions with variable length N terminus and a relatively long intracellular C terminus. Three α1C isoforms have been identified: cardiac, CaV1.2a; smooth muscle, CaV1.2b; and neuronal, CaV1.2c. Although CaV1.2a-c display significant sequence differences in their N and C termini, they all physically interact with the anchoring protein AKAP150/79 via their C-termini and are regulated by intracellular kinases and phosphatases to control Ca2+ entry and excitability [14].

Electrophysiological studies indicate that approximately 10,000–16,000 functional CaV1.2 channels are expressed in a typical ventricular myocyte. Similar approaches suggest that vascular smooth muscle cells express fewer CaV1.2 channels than ventricular myocytes (5,000–10,000) [5]. However, due to differences in cell size, the average density of CaV1.2 channels cardiac and smooth muscle cells is similar (i.e., 5–15 channels/μm2) [5, 17, 18].

Immunofluorescence and confocal imaging approaches have been used to determine the spatial organization of CaV1.2 channels in cardiac and vascular smooth muscle. These data suggest that CaV1.2 channels are differentially distributed throughout the sarcolemma of these cells. In cardiac myocytes, however, CaV1.2 channels are preferentially expressed in the transverse tubules (T-tubules) [19]. In vascular smooth muscle, CaV1.2 channels seem to be broadly distributed along the sarcolemma of these cells [10, 20, 21].

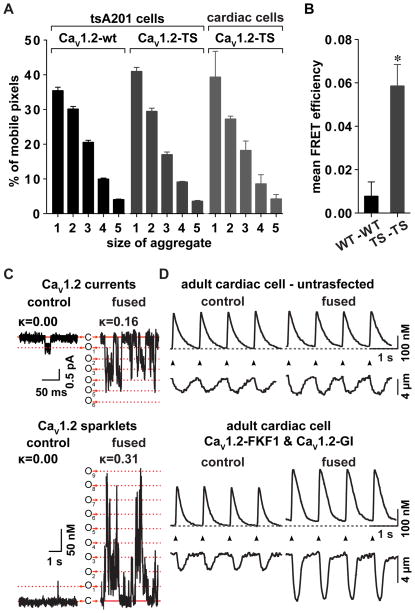

Using stimulated emission depletion (STED) ultra-resolution microscopy, Enrico Stefani’s group was able to image small clusters of variable size of CaV1.2 channels in the T-tubules of ventricular myocytes [22]. This is consistent with a recent study in which raster imaging correlation spectroscopy (RICS) and number & brightness (N&B) analyses were employed to determine the rate of diffusion and cluster size of fluorescently tagged CaV1.2 channels in heterologous cells and cardiac myocytes [11]. Using RICS, the diffusion co-efficient of wild type and CaV1.2 channels carrying a mutation linked to long QT syndrome 8 (LQT8 or Timothy syndrome) was estimated to be about 2.5 μm2/s in these cells. N&B analysis — a moment analysis that can be used to determine the fluorescence of diffusing monomeric fluorescent molecules and to estimate the number of molecules and brightness within a volume — suggested that while most CaV1.2 (WT and LQT8) channels diffuse in solitude, clusters of 2 to 5 channels can diffuse throughout the surface membrane of tsA-201 cells expressing CaV1.2 channels fused to the tag red fluorescence protein (CaV1.2-tRFP channels) and in ventricular myocytes expressing CaV1.2-LQT8-tRFP channels (Figure 4A). Although similar studies have not been performed in vascular smooth muscle, the observation of CaV1.2 clusters in tsA-201 and ventricular myocytes suggest this may be a general feature of these channels in excitable cells. Future studies should examine this issue in detail and also investigate the molecular mechanisms determining the size of CaV1.2 clusters in cardiac and vascular smooth muscle.

Figure 4. Ca2+ signaling amplification by oligomerization of CaV1.2 channels.

A) Bar plot of the number & brightness analysis showing the relative percentage of mobile pixels in tsA201 cells or cardiac cells expressing wild type (wt) or Timothy syndrome (TS) CaV1.2 channels tagged with tRFP. B) Bar plot of the mean FRET efficiency between wt CaV1.2 channels or TS CaV1.2 channels. C) Representative recordings of CaV1.2 currents (upper panel) and sparklets (lower panel) obtained from tsA201 cells transfected with CaV1.2 channels tagged with a light-activated fusion system [58] before and after induction of channels fusion. D) Evoked Ca2+ transients and simultaneous cell length changes in un-transfected cardiac cells (upper panel) and cells expressing CaV1.2 channels tagged with the light-activated fusion system (lower panel) before and after channels fusion. Adapted from Dixon et al [11].

CaV1.2 sparklets in cardiac and vascular smooth muscle

Heping Cheng’s team coined the term Ca2+ sparklet to name the small, local Ca2+ signals produced by the opening of L-type CaV1.2 channels in ventricular myocytes[4]. As mentioned above, we propose the use of the word sparklet preceded by the name of the gene encoding the Ca2+-permeable channel producing the local Ca2+ signal to link the local Ca2+ to the channel that produced it. For example, we would call CaV1.2, CaV1.3, CaV2.2, AChRs and TRPV4 sparklets local Ca2+ signals produced by CaV1.2, CaV1.3, CaV2.2, AChRs and TRPV4 channels, respectively [10, 23–26].

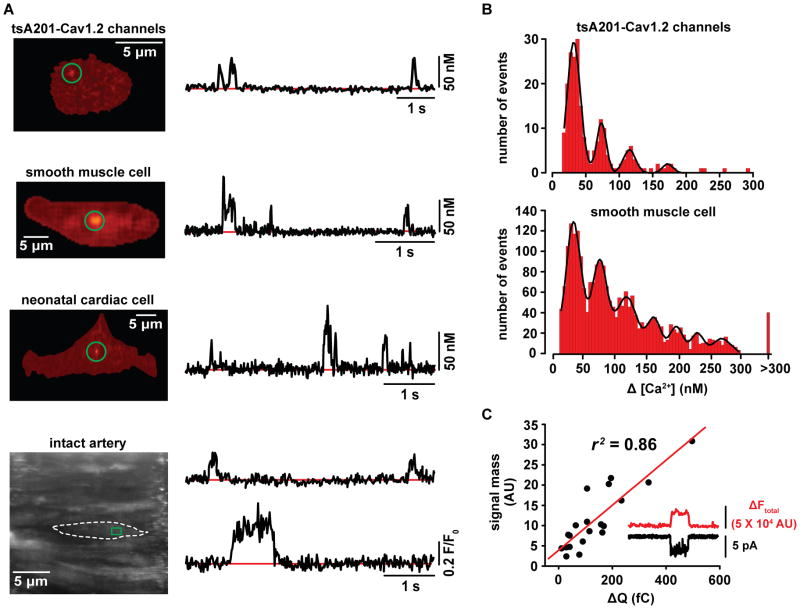

Since Cheng’s original report, we and others, have implemented ultra fast 2-dimensional confocal and total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) imaging to monitor with high temporal and spatial resolution the activity of CaV1.2 sparklets in tsA201 expressing these channels, in isolated cardiac and vascular smooth muscle and in intact arteries (Figure 1A) [9, 10]. Readers interested in learning more about the strategies for the recording, detection, and analysis of sparklets will find detailed descriptions in the following publications: [12, 26–30].

Figure 1. CaV1.2 sparklets.

A) Total internal reflection fluorescence and swept-field confocal images of CaV1.2 sparklets recorded from representative tsA201 cells expressing CaV1.2 channels, isolated vascular smooth muscle, neonatal cardiac cells or smooth muscle cells in an intact artery. The traces to the right of each image show the time-course of [Ca2+]i in the sites highlighted by the green circle (square) in the images. B) Amplitude histograms of CaV1.2 sparklets recorded from tsA201 cells expressing CaV1.2 channels or vascular smooth muscle cells. The solid black lines in the histograms are the best fit to the data following a multicomponent Gaussian function with a quantal unit of Ca2+ influx of 38 nM Ca2+. C) Plot of the relationship between signal mass as a function of Ca2+ flux in vascular smooth muscle. Parts of this figure have been adapted from Navedo et al [10, 27], and Amberg et al [8].

Implementation of these approaches revealed multiple interesting features of CaV1.2 channels in cardiac and vascular smooth muscle [4, 8, 10]. For example, the amplitude of CaV1.2 sparklets is quantal. In 20 mM external Ca2+, the quantal unit of Ca2+ influx via these channels is about 40 nM (Figure 1B). In physiological 2 mM external Ca2+, the amplitude of most CaV1.2 sparklets were <20 nM or undetectable, even at very negative potentials (−70 mV), where the driving force for Ca2+ influx is high.

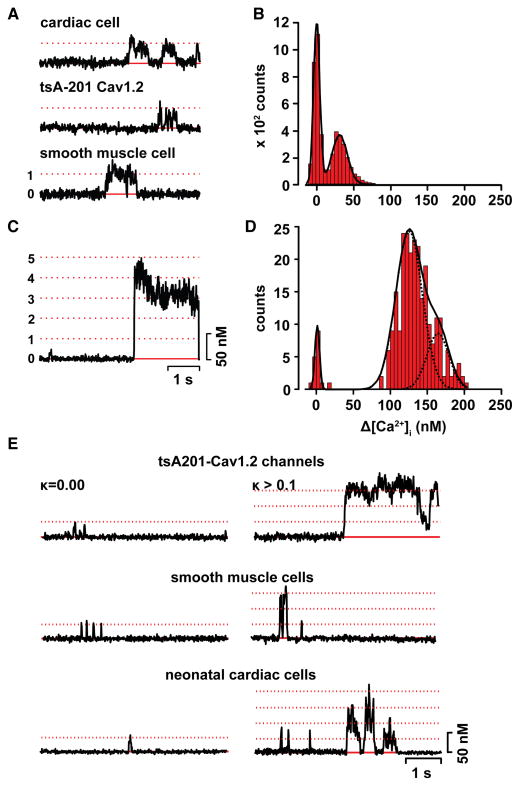

Interestingly, CaV1.2 sparklet activity is bimodal, with most of the sarcolemma being optically silent, while other regions display either low or high CaV1.2 sparklet activity [8]. CaV1.2 channel agonists increase Ca2+ influx by increasing CaV1.2 sparklet activity in previously silent sites and low activity sites. A CaV1.2 sparklet is always associated with an inward Ca2+ current (Figure 1C). Accordingly, the signal mass of the fluorescence signal follows a linear relationship when compared to the Ca2+ flux through CaV1.2 channels in vascular smooth muscle. An intriguing observation made in these studies is that while the majority of CaV1.2 sparklets seem to be produced by the stochastic opening of CaV1.2 channels, a subpopulation of CaV1.2 sparklets seems to be produced by the coordinated opening of small clusters of CaV1.2 channels (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Coupled gating of CaV1.2 channels.

A) Representative optical recordings of single CaV1.2 channels in neonatal cardiac cells (top), tsA201 cells (middle), and vascular smooth muscle cells (bottom). B) All-points histogram of CaV1.2 sparklet traces in A. C) Fluorescence time-course of a CaV1.2 sparklet site with coupled channels. D) All-points histogram of CaV1.2 sparklet traces in D. E) Representative fluorescence traces of stochastic (left panel) and coupled CaV1.2 sparklets in tsA201 cells, vascular smooth muscle and cardiac cells. Parts of this figure have been adapted from Navedo et al [12].

Mark Nelson’s group recently recorded sparklets resulting from Ca2+ influx via TRPV4 channels in endothelial cells [24]. Although TRPV4 sparklets are not the focus of this review, we discuss some of the conclusions of this study here for three important reasons. (1) In conjunction with the CaV1.2 sparklet work discussed above, this study suggests that optical approaches can be used to image elementary TRPV4 and CaV1.2 sparklets events. This work is particular impressive because TRPV4 sparklets were recorded from endothelial cells in resistance arteries exposed to physiological extracellular Ca2+. Indeed, it was found that the amplitude of quantal TRPV4 sparklets is larger than that of CaV1.2 sparklets, suggesting that Ca2+ flux is larger via TRPV4 than CaV1.2 channels. (2) An important observation by Sonkusare et al [24] is that, like CaV1.2 sparklets, TRPV4 sparklet activity varies throughout the surface membrane of endothelial cells, suggesting that a relatively small number of TRPV4 channels can have important functional consequences in these cells. (3) Finally, it was also discovered that, like CaV1.2 channels, small clusters of TRPV4 channels could gate coordinately to produce large TRPV4 sparklets in endothelial cells. Collectively, these findings suggest that heterogeneous and cooperative channel gating could be a common feature of TRPV4 and CaV1.2 channels.

Mechanisms underlying regional variations in CaV1.2 sparklet activity in cardiac and vascular smooth muscle

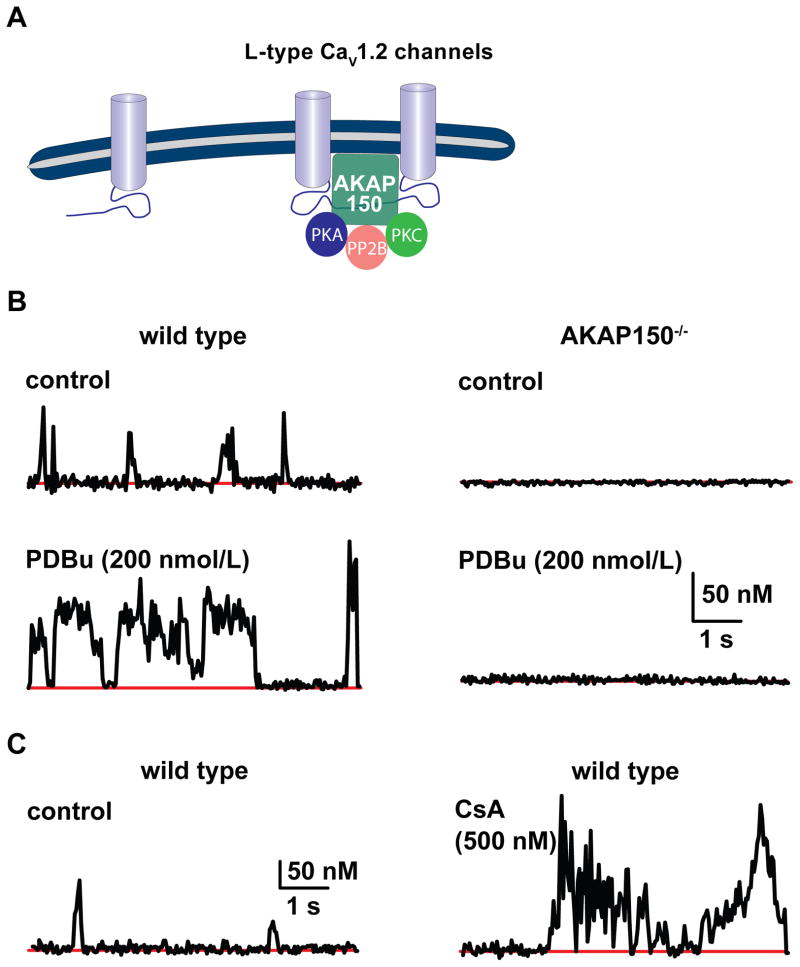

The mechanisms underlying heterogeneous CaV1.2 sparklet activity have been the subject of intense investigation during the last several years. Based on this work, a model has been proposed in which the anchoring protein A-kinase anchoring protein 150 (AKAP150) plays a central role in the formation of a macromolecular signaling complex that regulates CaV1.2 channels and hence CaV1.2 sparklet activityin cardiac and vascular smooth muscle (Figure 2A). AKAP150 is responsible for targeting protein kinase A (PKA), protein kinase C (PKC), and the protein phosphatase calcineurin, to specific regions of the sarcolemma where they can differentially regulate CaV1.2 channel activity (Figure 2). CaV1.2 channels that are associated with this macromolecular complex are capable of operating in a high activity mode. An important implication of this model is that the level of sparklet activity depends on the relative activities of AKAP150-associated kinases (e.g., PKA or PKC) and the phosphatase (e.g., calcineurin) on CaV1.2 channels (Figure 2B and 2C).

Figure 2. Mechanisms of heterogeneous CaV1.2 sparklet activity.

A) Schematic diagram of the interaction of AKAP150 with a subpopulation of CaV1.2 channels. B) Representative time-course of [Ca2+]i traces illustrating that activation of PKC with PDBu increases CaV1.2 sparklet activity in vascular smooth muscle. Right panel shows fluorescence traces indicating that AKAP150 is required for increased CaV1.2 sparklet activity. C) Time-course of [Ca2+]i demonstrating that inhibition of calcineurin with cyclosporine A increases CaV1.2 sparklet activity. Parts of this figure have been adapted from Navedo et al [20, 27].

Evidence in support of this model is compelling. First, AKAP150 binds PKA, PKC, calcineurin and CaV1.2 channels in the sarcolemma of neurons, and cardiac and vascular smooth muscle [19, 20, 31]. Accordingly, AKAP150, PKA and PKC co-localize to specific regions within the sarcolemma of cardiac and vascular smooth muscle [19, 20, 31]. Second, ablation of AKAP150 prevents the induction of high-activity CaV1.2 sparklet events (Figure 2B) [19, 27]. Third, the actions of PKA and PKC on CaV1.2 channel activity are opposed by calcineurin (Figure 2C) [27, 32, 33]. Fourth, only a subpopulation of CaV1.2 channels is associated with AKAP150 [20].

Several aspects of this AKAP-CaV1.2 sparklet model compel further investigation, however. For example, future studies should determine whether AKAP150 is involved in PKA- and ROS-dependent regulation of CaV1.2 sparklets, as suggested by recent studies [32, 34, 35]. It is also necessary to determine whether AKAP150 tethered PKA in vascular smooth muscle as suggested by a recent report [32, 34, 35], or whether AKAP150 and PKC are co-localized to similar subcellular regions in cardiac cells. Furthermore, it will be interesting to investigate whether these or similar regulatory mechanisms underlie heterogeneous activity in other cell types (e.g., neurons) or other ion channels (e.g., TRPV4 channels).

Coupled gating of CaV1.2 sparklets in cardiac and vascular smooth muscle

One of the most intriguing observations in sparklet studies is that subsets of CaV1.2 channels (and also TRPV4 channels) expressed in tsA-201 cells, as well as cardiac and vascular smooth muscle can open synchronously, generating large sparklets (Figure 3) [12]. However, coupling between CaV1.2 channels seems to occur with a higher probability in regions of the myocyte where these channels co-exist with AKAP150. This imposes technical challenges for the recording and analysis of the molecular mechanisms underlying coupled activation of CaV1.2 channels. For example, since only a subpopulation of CaV1.2 channels could undergo coupled gating, the use of patch-clamp approaches to record currents from relatively small areas of the membrane is likely to yield limited results in terms of the number of couple gating events per trial. Accordingly, optical recordings of CaV1.2 channels from relatively large portions of the surface membrane may represent a more efficient approach to study coupled gating between these channels. This approach has also proved to be fruitful for the recording of TRPV4 sparklets resulting from the cooperative gating among 4 of these channels [24].

Identification and analysis of CaV1.2 sparklets and currents resulting from the coordinated opening of CaV1.2 channels requires a multi-pronged approach [12, 36]. For CaV1.2 channels, this analysis has included an assessment of whether the frequency of observed multi-channel events exceeds the probability of simultaneous openings and closing of the number of channels involved (Figure 3A–D). For example, the open probability (Po) of a single CaV1.2 channel is only ≈0.3 at +50 mV [5]. Thus, the probability of independently gating channels opening simultaneously at this potential should be very low: ≈0.09, 0.03, and 0.01 for the random, coincidental opening of 2, 3, or 4 channels. Accordingly, if L-type Ca2+ channels open randomly, the probability of observing CaV1.2 sparklets resulting from simultaneous openings of these channels should be progressively lower as the number of participating channels increases, which should result in a histogram with peaks of decreasing amplitudes as multichannel events become less apparent (Figure 3).

A complementary approach used by our group is the implementation of a coupled Markov chain model [37] to determine the coupling coefficient or strength (κ) among CaV1.2 channels from optical and electrical recordings [9, 12]. This model consists of a simplified Markov chain model with only 3 free parameters that takes the form of a set of binary chains that are interdependent according to a lumped coupling coefficient parameter (κ). The other two parameters (ρ and ς) describe the intrinsic characteristics of the binary chains. The κ value could range from 0 for independently gating channels to 1 for “tightly” coupled channels that open and close simultaneously at all times. Analysis of CaV1.2 sparklets and currents using this model suggested a median κ value of 0.21, suggesting that the channels in these clusters seem to gate independently most of the time. This is consistent with a model in which functional coupling between CaV1.2 channels is sporadic [12].

Although the mechanisms underlying coupled gating of CaV1.2 channels in cardiac and vascular smooth muscle are not completely understood, multiple lines of evidence suggest that CaV1.2 channels coordinate their openings via protein-to-protein interactions (Figure 4) [11, 12]. This would require that CaV1.2 channels cluster, that the distance between adjacent channels is small enough to allow physical interactions, that neighboring channels can form stable physical interactions, and finally, that physical linkage between CaV1.2 channels is sufficient to increase channel activity and coupling strength.

Consistent with this, the N&B analysis [38] suggest that CaV1.2 channels are sufficiently close to form small clusters of variable sizes that diffuse throughout the sarcolemma of ventricular myocytes (Figure 4A) [11]. CaV1.2 channels lacking most of their carboxy terminal do not undergo coupled gating [12], suggesting this segment of the channel is necessary for coupled gating. FRET analysis suggested that the carboxy terminal of adjacent CaV1.2 channels comes into close proximity under conditions that increase the probability of coupled gating (Figure 4B) [12]. Furthermore, light-induced fusion of the carboxy terminal of CaV1.2 channels increased activity and coupling strength between adjoined channels (Figure 4C) [11]. In native cells, physical interactions between CaV1.2 channels that translates into an increase in channel activity and coupling seem to be facilitated, and likely stabilized, by AKAP150, as coupled gating is eliminated by ablation of this anchoring protein. Collectively, these results strongly suggest that coupled gating of CaV1.2 sparklets involves transient interactions between the carboxy terminals of a subpopulation of CaV1.2 channels associated with AKAP150 in cardiac and vascular smooth muscle.

CaV1.2 sparklets in cardiac EC coupling

Having discussed the biophysical properties of CaV1.2 sparklets, we now turn our attention to their role in cardiac and smooth muscle. We focus first on cardiac EC coupling (Figure 5). In heart, every AP triggers a contraction. Indeed, under basal physiological conditions, the coefficient of variation (COV = standard deviation/mean) of the [Ca2+]i transient that activates contraction is about 0.1, indicating a low level of trial-to-trial variation during EC [39]. The [Ca2+]i transient is presumably initiated by the opening of multiple, independently gating CaV1.2 channels during an AP. The stochastic lifetimes of these channels are exponentially distributed so that the standard deviation of their lifetimes is equal to the mean, which should result in a COV = 1. This suggests that the level of variability in the open times of CaV1.2 channel could be as much as 10-fold higher than that of the [Ca2+]i transient.

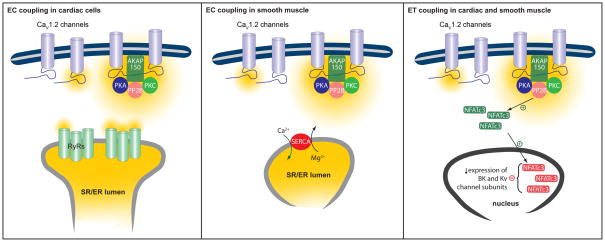

Figure 5. Proposed model for the role of CaV1.2 sparklet activity and coupled gating events on EC and ET coupling in cardiac and vascular smooth muscle.

See main text for details.

An important factor determining EC coupling is the amplitude of elementary CaV1.2 channel currents. At +50 mV, a membrane potential similar to the plateau of the AP, and in the presence of 20 mM Ca2+ with the dihydropyridine agonist FPL64176, CaV1.2 channels have a unitary conductance of about 0.5 pA. Under these experimental conditions, a CaV1.2 sparklet produced by the opening of a single CaV1.2 channel can activate a Ca2+ spark [4]. However, in 2 mM external Ca2+, the current produced by the opening of a single CaV1.2 channel is estimated to be about 0.01 pA [40]. With this low unitary current, > 10 CaV1.2 channels must open simultaneously to reliably activate a Ca2+ spark and account for a Pspark ≈ 1 during the plateau of the cardiac AP [40]. If the maximum open probability of CaV1.2 channels gating independently is 0.3, how can Pspark ≈ 1 during the plateau of the AP when the probability of coincident activation of 10 CaV1.2 channels could be as low as 0.310? Furthermore, how does the AP-evoked [Ca2+]i transient achieves a high level of reproducibility given these constrains?

During the ventricular AP, membrane depolarization activates CaV1.2 sparklets. These Ca2+ signals activate small clusters of ryanodine receptors (RyRs) located in nearby jSR, initiating Ca2+ release from this organelle [41]. The functional unit composed of CaV1.2 channels and associated RyRs is called a “couplon” [42]. The coupling strength between these two channels is proportional to the amount of Ca2+ flux via CaV1.2 channels and local [Ca2+]i [6]. Synchronous activation of multiple couplons generates cell-wide increases in cytosolic [Ca2+]i that triggers contraction in cardiac muscle [4].

A potential answer to question of how a Pspark ≈ 1 is achieved at positive potentials, is that coupling of CaV1.2 channels increases the probability of synchronous openings of these channels and thus the probability of Ca2+ spark activation during EC coupling [43]. Although this hypothesis has not been tested yet, recent findings from our group are consistent with it. For example, loss of AKAP150, which decreases the probability of coupled gating between CaV1.2 channels, diminished the amplitude of the AP-evoked [Ca2+]i transient [9]. Furthermore, light-induced fusion of wild type (WT) CaV1.2 channels increased Ca2+ influx by increasing the activity and coupling strength of adjacent CaV1.2 channels [11]. This culminated in an increase in whole-cell CaV1.2 currents, diastolic and systolic [Ca2+]i levels, and contractility of cardiac cells (Figure 4D) [11].

Coupling between CaV1.2 channels, even if transient could have profound pathological implications in cardiac cells. Indeed, a recently discovered point mutation (G406R) in the CaV1.2 channels has been linked to Timothy Syndrome (TS) and arrhythmias [44]. LQT8 channels inactivate at a slower rate than WT channels [44–46]. Although phosphorylation of the channel by the Ca2+/CaM-dependent kinase II (CAMKII) has been suggested as a potential culprit for abnormal TS channel function [47], the mechanisms underlying larger Ca2+ currents by these channels are incompletely understood.

Recent data from our team shed some light on this issue, however. Using optogenetic approaches, it was found that light-induced fusion between WT and TS channels induced the WT channel to take on the biophysical properties of the “dominant” TS channel. Fusion of these channels conferred TS properties to the linked WT channel, thereby increasing Ca2+ currents, [Ca2+]i transient, contractility and arrhythmogenic Ca2+ fluctuations in cardiac cells [11]. Data suggested that the channel with the higher activity (e.g. TS channels) is likely to determine the level of activity of the linked channel. This observation has profound functional implications, especially in the context of the TS disease, where only about 23% of CaV1.2 channels in the heart carry the mutation [44]. Thus, the expression of a small number of TS channels could amplify Ca2+ influx in cardiac cells by interacting and modulating the activity of neighboring WT channels.

An important observation is that AKAP150 plays a critical role in the chain of events shaping abnormal TS channel function in cardiac cells that is independent of CAMKII activity or its ability to target PKA [9]. In the presence of the TS mutation, AKAP150 functions like a subunit of TS channels. AKAP150 most likely interacts with TS channels via leuzine zipper domains located in the carboxy terminal of both proteins [31]. The formation of this aberrant channel-anchoring protein complex serves to stabilize the open conformation and increase the frequency of coupled events in TS channels, thus leading to cardiac hypertrophy and arrhythmias. Data in support of this model is compelling. First, using a transgenic mouse that expresses the TS mutation solely in the heart, it was found that ablation of AKAP150 protects against cardiac hypertrophy during TS. Second, loss of AKAP150 was sufficient to restore inactivation rates of whole-cell Ca2+ currents, single-channel activity, frequency of coupled events, EC coupling, action potential waveform, and cardiac rhythm to WT levels in cardiac cells expressing the TS mutation. Thus, it is proposed that AKAP150 interacts with TS channels via the carboxy terminal of both proteins to function as an allosteric modulator of the channel with detrimental physiological consequences. Future studies should determine the molecular mechanisms governing the interaction and regulation of AKAP150 in WT and TS channels.

CaV1.2 sparklets in vascular smooth muscle EC coupling

Unlike ventricular myocytes, CaV1.2 channels and RyRs are not functionally coupled in vascular smooth muscle [48–50]. Rather, activation of CaV1.2 sparklets contributes to a global cytosolic Ca2+ pool from which the SR can draw to accelerate store refilling and/or directly activates the contractile machinery in vascular smooth muscle (Figure 5) [48]. Ca2+ entering via persistent Ca2+ sparklets with coupled events accounted for ~50% of the total dihydropyridine-sensitive Ca2+ influx that regulates steady-state global [Ca2+]i [8]. Thus, an increase in the frequency of persistent Ca2+ sparklets with coupled events could have profound effects on vascular smooth muscle excitability.

CaV1.2 sparklet activity and frequency of coupled events are significantly elevated in vascular smooth muscle during hypertension and in type II diabetes [32, 51], thus increasing arterial tone during these pathological conditions. The mechanisms underlying this increased in sparklet activity and frequency of coupled events depend on the pathological condition, however. Although AKAP is required for the generation of high-activity CaV1.2 sparklets and induction of coupled events in both cases, increases in sparklet activity and coupled gating in type II diabetes results from local activation of an AKAP-targeted PKA [32]. On the other hand, increased activity and coupled gating of CaV1.2 sparklets during hypertension is the result of an increase in CaV1.2 α1 subunit expression [52], AKAP150-targeted PKCα activity [51], and possibly PKCα-dependent reactive oxygen species (ROS) signaling [34, 35]. Regardless of the mechanism, data indicate that an increase in CaV1.2 sparklet activity and frequency of coupled events could translate into enhanced Ca2+ influx, global [Ca2+]i, and thus contraction, that may contribute to the development of vascular dysfunction during type II diabetes and hypertension.

CaV1.2 sparklets in ET coupling

CaV1.2 sparklets could also also regulate gene expression in cardiac and vascular smooth muscle. Ca2+ influx through CaV1.2 channels is required for activation of the transcription factor NFATc3 via calcineurin after myocardial infarction and during angiotensin II-induced hypertension [51, 53–56]. Activation of this pathway results in the down-regulation of a number of K+ channels that contribute to excitability of cardiac and vascular smooth muscle (Figure 5) [53–55].

During physiological conditions, calcineurin and NFATc3 activity are relatively low because of low levels of persistent CaV1.2 sparklets and frequency of coupled events [12, 20], and high nuclear NFATc3 export rates [57]. However, an increase in the activity of AKAP-targeted PKA and/or AKAP-targeted PKC during myocardial infarction and type II diabetes, or hypertension, respectively, induces high-activity CaV1.2 sparklets and coupled gating behavior. This will produce an increase in local Ca2+ influx that can be sense by the AKAP-targeted Ca2+/CaM phosphatase calcineurin. Once activated, calcineurin can dephosphorylate NFATc3, thus inducing its translocation into the nucleus where it can modify the expression of Kv and BK channel subunits in cardiac and vascular smooth muscle. Downregulation of K+ channel subunits decreases Ca2+-sensitive and voltage-dependent K+ currents, thus contributing to vascular smooth muscle depolarization during hypertension and possibly type II diabetes. In the heart, downregulation of K+ channel subunits decreases K+ currents leading to action potential prolongation. In both cases, the end result is an increase in global [Ca2+]i that ultimately perpetuates the pathological condition in cardiac and vascular smooth muscle. Consistent with this model, ablation of AKAP150, which prevents the induction of persistent CaV1.2 sparklets and coupled events, protects against the development of angiotensin II-induced hypertension [12, 20]. Future studies should determine whether loss of AKAP150, or disruption of the interaction between AKAP150 and any of its binding partners (PKA, PKC or calcineurin) prevents the activation of NFATc3, and thus the remodeling of K+ channels function during hypertension, vascular dysfunction during type II diabetes or myocardial infarction.

Conclusions

The application of novel imaging techniques and stringent analytical approaches over the last decade has allowed the study of the functional organization of CaV1.2 channels with high spatial and temporal resolution. These optical recordings and analytical approaches are applicable to the study of any Ca2+ permeable ion channel in excitable and non-excitable cells. Using these approaches, four major fundamental features about CaV1.2 channels in cardiac and vascular smooth muscle have been revealed. First, the activity and spatial organization of functional channels is variable throughout the sarcolemma. Second, a subpopulation of these channels can become functionally coupled to promote Ca2+ signal amplification. Third, the scaffolding protein AKAP150 can function as an auxiliary subunit of CaV1.2 channels to promote coupled gating between adjacent channels. Consistent with this, heterogeneous CaV1.2 sparklet activity and coupled gating seems to be dependent on a signaling module formed by a subpopulation of CaV1.2 channels in association with AKAP150, PKA, PKC, and calcineurin in specific foci of the sarcolemma. Fourth, in a cluster with coupled CaV1.2 channels, the channel with the higher open probability (i.e. PO) is likely to determine the level of activity of the linked channel, thus effectively amplifying calcium influx. Evidently, the formation of this signaling module has profound implications for EC and ET coupling during physiological and pathological conditions in cardiac and vascular smooth muscle.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thanks Dr. Matthew A. Nystoriak for critically reading early versions of this manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the American Heart Association – Scientist Development Grant 0735251N and National Institutes of Health 1R01HL098200 (to MFN), and National Institutes of Health 2RO1HL085686 and 2RO1HL085870 (to LFS). Luis F. Santana is an Established Investigator of the American Heart Association.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Guatimosim S, Dilly K, Santana LF, Saleet Jafri M, Sobie E, Lederer W. Local Ca2+ Signaling and EC Coupling in Heart: Ca2+ Sparks and the Regulation of the [Ca2+]i Transient. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2002;34:941. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.2032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vega AL, Yuan C, Votaw VS, Santana LF. Dynamic changes in sarcoplasmic reticulum structure in ventricular myocytes. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:382586. doi: 10.1155/2011/382586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gollasch M, Lohn M, Furstenau M, Nelson MT, Luft FC, Haller H. Ca2+ channels, ‘quantized’ Ca2+ release, and differentiation of myocytes in the cardiovascular system. J Hypertens. 2000;18:989–98. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200018080-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang SQ, Song LS, Lakatta EG, Cheng H. Ca2+ signalling between single L-type Ca2+ channels and ryanodine receptors in heart cells. Nature. 2001;410:592–6. doi: 10.1038/35069083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rubart M, Patlak JB, Nelson MT. Ca2+ currents in cerebral artery smooth muscle cells of rat at physiological Ca2+ concentrations. J Gen Physiol. 1996;107:459–72. doi: 10.1085/jgp.107.4.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santana LF, Cheng H, Gomez AM, Cannell MB, Lederer WJ. Relation between the sarcolemmal Ca2+ current and Ca2+ sparks and local control theories for cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Circulation research. 1996;78:166–71. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.1.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knot HJ, Nelson MT. Regulation of arterial diameter and wall [Ca2+] in cerebral arteries of rat by membrane potential and intravascular pressure. The Journal of physiology. 1998;508:199–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.199br.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amberg GC, Navedo MF, Nieves-Cintrón M, Molkentin JD, Santana LF. Calcium Sparklets Regulate Local and Global Calcium in Murine Arterial Smooth Muscle. The Journal of physiology. 2007;579:187–201. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.124420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng EP, Yuan C, Navedo MF, Dixon RE, Nieves-Cintron M, Scott JD, et al. Restoration of normal L-type Ca2+ channel function during Timothy syndrome by ablation of an anchoring protein. Circulation research. 2011;109:255–61. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.248252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Navedo MF, Amberg G, Votaw SV, Santana LF. Constitutively active L-type Ca2+ channels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:11112–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500360102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dixon RE, Yuan C, Cheng EP, Navedo M, Santana LF. Calcium signaling amplification by oligomerization of L-type Cav1.2 channels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116731109. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Navedo MF, Cheng EP, Yuan C, Votaw S, Molkentin JD, Scott JD, et al. Increased coupled gating of L-type Ca2+ channels during hypertension and Timothy syndrome. Circulation research. 2010;106:748–56. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.213363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hymel L, Striessnig J, Glossmann H, Schindler H. Purified skeletal muscle 1,4-dihydropyridine receptor forms phosphorylation-dependent oligomeric calcium channels in planar bilayers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1988;85:4290–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.12.4290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Catterall WA. Structure and regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2000;16:521–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takahashi SX, Miriyala J, Tay LH, Yue DT, Colecraft HM. A CaVbeta SH3/guanylate kinase domain interaction regulates multiple properties of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. The Journal of general physiology. 2005;126:365–77. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bannister JP, Adebiyi A, Zhao G, Narayanan D, Thomas CM, Feng JY, et al. Smooth muscle cell alpha2delta-1 subunits are essential for vasoregulation by CaV1.2 channels. Circulation research. 2009;105:948–55. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.203620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lew WY, Hryshko LV, Bers DM. Dihydropyridine receptors are primarily functional L-type calcium channels in rabbit ventricular myocytes. Circulation research. 1991;69:1139–45. doi: 10.1161/01.res.69.4.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horiba M, Muto T, Ueda N, Opthof T, Miwa K, Hojo M, et al. T-type Ca2+ channel blockers prevent cardiac cell hypertrophy through an inhibition of calcineurin-NFAT3 activation as well as L-type Ca2+ channel blockers. Life sciences. 2008;82:554–60. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nichols CB, Rossow CF, Navedo MF, Westenbroek RE, Catterall WA, Santana LF, et al. Sympathetic stimulation of adult cardiomyocytes requires association of AKAP5 with a subpopulation of L-type calcium channels. Circulation research. 2010;107:747–56. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.216127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Navedo MF, Nieves-Cintron M, Amberg GC, Yuan C, Votaw VS, Lederer WJ, et al. AKAP150 is required for stuttering persistent Ca2+ sparklets and angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Circulation research. 2008;102:e1–e11. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.167809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore ED, Voigt T, Kobayashi YM, Isenberg G, Fay FS, Gallitelli MF, et al. Organization of Ca2+ release units in excitable smooth muscle of the guinea-pig urinary bladder. Biophysical journal. 2004;87:1836–47. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.044123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodriguez PFG, Wu Y, Zhao H, Singh H, Lu R, Li M, et al. A Custom-Built Fast Scanning STED Microscope with a Large Field of View. Biophys J. 2012;102:141a. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Navedo MF, Amberg GC, Westenbroek RE, Sinnegger-Brauns MJ, Catterall WA, Striessnig J, et al. Cav1.3 channels produce persistent calcium sparklets, but Cav1.2 channels are responsible for sparklets in mouse arterial smooth muscle. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 2007;293:H1359–70. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00450.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sonkusare SK, Bonev AD, Ledoux J, Liedtke W, Kotlikoff MI, Heppner TJ, et al. Elementary Ca2+ signals through endothelial TRPV4 channels regulate vascular function. Science. 2012;336:597–601. doi: 10.1126/science.1216283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Demuro A, Parker I. Imaging the activity and localization of single voltage-gated Ca2+ channels by total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy. Biophysical journal. 2004;86:3250–9. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74373-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Demuro A, Parker I. “Optical patch-clamping”: single-channel recording by imaging Ca2+ flux through individual muscle acetylcholine receptor channels. J Gen Physiol. 2005;126:179–92. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Navedo MF, Amberg GC, Nieves M, Molkentin JD, Santana LF. Mechanisms Underlying Heterogeneous Ca2+ Sparklet Activity in Arterial Smooth Muscle. Journal of General Physiology. 2006;127:611–22. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santana LF, Navedo MF. Molecular and biophysical mechanisms of Ca2+ sparklets in smooth muscle. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2009;47:436–44. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Demuro A, Parker I. Optical single-channel recording: imaging Ca2+ flux through individual ion channels with high temporal and spatial resolution. J Biomed Opt. 2005;10:11002. doi: 10.1117/1.1846074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shuai J, Parker I. Optical single-channel recording by imaging Ca2+ flux through individual ion channels: theoretical considerations and limits to resolution. Cell calcium. 2005;37:283–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oliveria SF, Dell’Acqua ML, Sather WA. AKAP79/150 anchoring of calcineurin controls neuronal L-type Ca2+ channel activity and nuclear signaling. Neuron. 2007;55:261–75. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Navedo MF, Takeda Y, Nieves-Cintron M, Molkentin JD, Santana LF. Elevated Ca2+ sparklet activity during acute hyperglycemia and diabetes in cerebral arterial smooth muscle cells. American journal of physiology Cell physiology. 2010;298:C211–20. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00267.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Santana LF, Chase EG, Votaw VS, Nelson MT, Greven R. Functional coupling of calcineurin and protein kinase A in mouse ventricular myocytes. The Journal of physiology. 2002;544:57–69. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.020552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amberg GC, Earley S, Glapa SA. Local regulation of arterial L-type calcium channels by reactive oxygen species. Circulation research. 2010;107:1002–10. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.217018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chaplin NL, Amberg GC. Hydrogen peroxide mediates oxidant-dependent stimulation of arterial smooth muscle L-type calcium channels. American journal of physiology Cell physiology. 2012 doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00222.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Santana LF, Navedo MF. Natural inequalities: why some L-type Ca2+ channels work harder than others. The Journal of general physiology. 2010;136:143–7. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200910391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chung SH, Kennedy RA. Coupled Markov chain model: characterization of membrane channel currents with multiple conductance sublevels as partially coupled elementary pores. Mathematical biosciences. 1996;133:111–37. doi: 10.1016/0025-5564(95)00084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Digman MA, Brown CM, Sengupta P, Wiseman PW, Horwitz AR, Gratton E. Measuring fast dynamics in solutions and cells with a laser scanning microscope. Biophysical journal. 2005;89:1317–27. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.062836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vega AL, Yuan C, Votaw VS, Santana LF. Dynamic changes in sarcoplasmic reticulum structure in ventricular myocytes. Journal of biomedicine & biotechnology. 2011;2011:382586. doi: 10.1155/2011/382586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Inoue M, Bridge JH. Variability in couplon size in rabbit ventricular myocytes. Biophysical journal. 2005;89:3102–10. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.065862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheng H, Lederer WJ, Cannell MB. Calcium sparks: elementary events underlying excitation-contraction coupling in heart muscle. Science. 1993;262:740–4. doi: 10.1126/science.8235594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Franzini-Armstrong C, Protasi F, Ramesh V. Shape, size, and distribution of Ca(2+) release units and couplons in skeletal and cardiac muscles. Biophysical journal. 1999;77:1528–39. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77000-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Inoue M, Bridge JH. Ca2+ sparks in rabbit ventricular myocytes evoked by action potentials: involvement of clusters of L-type Ca2+ channels. Circulation research. 2003;92:532–8. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000064175.70693.EC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Splawski I, Timothy KW, Sharpe LM, Decher N, Kumar P, Bloise R, et al. Ca(V)1.2 calcium channel dysfunction causes a multisystem disorder including arrhythmia and autism. Cell. 2004;119:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barrett CF, Tsien RW. The Timothy syndrome mutation differentially affects voltage- and calcium-dependent inactivation of CaV1.2 L-type calcium channels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:2157–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710501105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thiel WH, Chen B, Hund TJ, Koval OM, Purohit A, Song LS, et al. Proarrhythmic defects in Timothy syndrome require calmodulin kinase II. Circulation. 2008;118:2225–34. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.788067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Erxleben C, Liao Y, Gentile S, Chin D, Gomez-Alegria C, Mori Y, et al. Cyclosporin and Timothy syndrome increase mode 2 gating of CaV1.2 calcium channels through aberrant phosphorylation of S6 helices. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:3932–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511322103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takeda Y, Nystoriak MA, Nieves-Cintron M, Santana LF, Navedo MF. Relationship between Ca2+ sparklets and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ load and release in rat cerebral arterial smooth muscle. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 2011;301:H2285–94. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00488.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kotlikoff MI. Calcium-induced calcium release in smooth muscle: the case for loose coupling. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2003;83:171–91. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(03)00056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Essin K, Welling A, Hofmann F, Luft FC, Gollasch M, Moosmang S. Indirect coupling between Cav1.2 channels and RyR to generate Ca2+ sparks in murine arterial smooth muscle cells. The Journal of physiology. 2007 doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.138982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nieves-Cintron M, Amberg GC, Navedo MF, Molkentin JD, Santana LF. The control of Ca2+ influx and NFATc3 signaling in arterial smooth muscle during hypertension. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:15623–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808759105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pratt PF, Bonnet S, Ludwig LM, Bonnet P, Rusch NJ. Upregulation of L-type Ca2+ channels in mesenteric and skeletal arteries of SHR. Hypertension. 2002;40:214–9. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000025877.23309.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Amberg GC, Rossow CF, Navedo MF, Santana LF. NFATc3 Regulates Kv2.1 Expression in Arterial Smooth Muscle. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:47326–34. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408789200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nieves-Cintrón M, Amberg GC, Nichols CB, Molkentin JD, Santana LF. Activation of NFATc3 Down-regulates the β1 Subunit of Large Conductance, Calcium-activated K+ Channels in Arterial Smooth Muscle and Contributes to Hypertension. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:3231–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608822200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rossow CF, Minami E, Chase EG, Murry CE, Santana LF. NFATc3-Induced Reductions in Voltage-Gated K+ Currents After Myocardial Infarction. Circulation research. 2004;94:1340–50. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000128406.08418.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wilkins BJ, De Windt LJ, Bueno OF, Braz JC, Glascock BJ, Kimball TF, et al. Targeted disruption of NFATc3, but not NFATc4, reveals an intrinsic defect in calcineurin-mediated cardiac hypertrophic growth. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7603–13. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.21.7603-7613.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gomez MF, Bosc LV, Stevenson AS, Wilkerson MK, Hill-Eubanks DC, Nelson MT. Constitutively elevated nuclear export activity opposes Ca2+-dependent NFATc3 nuclear accumulation in vascular smooth muscle: role of JNK2 and Crm-1. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:46847–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304765200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yazawa M, Sadaghiani AM, Hsueh B, Dolmetsch RE. Induction of protein-protein interactions in live cells using light. Nature biotechnology. 2009;27:941–5. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]