Abstract

Insertions of orthopedic implants are traumatic procedures that trigger an inflammatory response. Macrophages have been shown to liberate gold ions from metallic gold. Gold ions are known to act in an antiinflammatory manner by inhibiting cellular NF-κB–DNA binding and suppressing I-κ B-kinase activation. The present study investigated whether gilding implant surfaces augmented early implant osseointegration and implant fixation by its modulatory effect on the local inflammatory response. Ion release was traced by autometallographic silver enhancement. Gold-coated cylindrical porous coated Ti6Al4V implants were inserted press-fit in the proximal part of tibiae in nine canines and control implants without gold inserted contralateral. Observation time was 4 weeks. Biomechanical push-out tests showed that implants with gold coating had ~50% decrease in mechanical strength and stiffness. Histomorphometrical analyses showed gold-coated implants had a decrease in overall total bone-to-implant contact of 35%. Autometallographic analysis revealed few cells loaded with gold close to the gilded implant surface. The findings demonstrate that gilding of implants negatively affects mechanical strength and osseointegration because of a significant effect of the released gold ions on the local inflammatory process around the implant. The possibility that a partial metallic gold coating could prolong the period of satisfactory mechanical strength, however, cannot be excluded.

Keywords: gold, in vivo, mechanical test, metal ion release, osseointegration

INTRODUCTION

Total joint replacement is a common end-stage treatment for degenerative joint diseases. Because of the success in reducing pain and improving quality of life, the trend is that more and more younger patients receive this treatment.1 As these patients have a longer life expectancy and are far more active, the factors increasing the risk of implant loosening increase proportionally.2 Noncemented porous-coated titanium (Ti) implants are the primary choice for such patients, but still today, up to 20% of all total hip replacements are revisions.3 Revision implants have an even shorter longevity and poorer functional outcome. Loose implants are thus still a major problem despite the fact that improved osseointegration, including increased bone-to-implant contact and increased new bone formation, has resulted in more stable early fixation that is followed by increased implant longevity.4,5 To continue to improve long-term stability of implants, different surface coatings are presently being investigated to improve biocompatibility.6

The insertions of orthopedic implants trigger an inflammatory response.7 The immunosuppressive effects of gold ions in systemic treatment such as parenteral aurothiomalate (Myocrisin®) have been used for treatment of autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis for more than 50 years.8In vivo studies and in vitro studies show that gold ions alter the behavior of macrophages by inhibiting lysosomal enzymes, reducing the number of macrophages, and diminishing production of cytokines.9 The reduced production of proinflammatory cytokines is caused by the ability of gold ions to suppress NF-κB DNA binding activity and I-κ B-kinase activation. NF-κB is a transcription factor, and its DNA binding is essential for a number of different cell activities including cytokine secretion in macrophages and proliferation in fibroblasts. Additionally, gold ions have been found to inhibit antigen processing.10,11 Despite being helpful in the clinic for many years, the use of gold compounds in medicine has been limited and replaced by non-steroid anti-inflammatory drug (NSAIDs) and newer biological agents, primarily because of gold’s adverse nephrotoxic effects.12

The findings that metallic gold placed in the living organism liberates gold ions that can be traced in adjacent cells such as macrophages, mast cells, and fibroblasts13 motivated the present study. The aim was to reveal whether gold ions released from gilded orthopedic implant surfaces would have a modulating action on the local inflammatory response, thereby resulting in improved biomechanical implant fixation and increased bone-to-implant contact and periimplant bone density.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design

NIH guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals have been observed and also an approval was obtained from our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee prior to perform the study. Eighteen implants were inserted in the proximal part of tibia (Fig. 1), bilaterally in nine skeletally mature mongrel dogs with a mean body weight of 24 kg (range 20 kg:26 kg). The study design was paired with gold-coated implants (Au) inserted on one side and control Ti implants without Au inserted in the contralateral side. The intervention side alternated with each animal.

Figure 1.

Implant inserted press-fit in medial side of proximal part of tibia in trabecular bone.

Animals and surgical procedure

The implants were inserted under general anesthesia and using sterile technique. In the proximal part of tibia, the implantation site was exposed through a medial approach. The periosteum was removed only at the area of drilling, 18 mm distal to the joint line. Initially, a guide wire was inserted, followed by a 5.6-mm cannulated drill. Drilling was performed at two rotations per second to prevent thermal trauma to the bone. The implant was inserted press-fit with repeated firm hammer blows. The overlying soft tissue was closed in layers. Prophylactic antibiotics were administered, consisting of rocephin 1 g IV preoperatively, and postoperatively (PO) rocephin 1 g IM per day for a minimum of 3-5 days or until afebrile. The dogs were allowed full weight-bearing, postoperatively.

The implants and the coating technique

Porous cylindrical (L = 10 mm, Ø = 6 mm) titanium (Ti6-Al-4V) implants were used (Biomet, Warsaw, IN). Additionally, half of the implants had their surfaces coated with gold, as follows. The implants were electrolytically cleaned by cathodic polarization of the implant for a heavy formation of hydrogen gas at the surface. The treatment14,15 was carried out in a strong alkaline solution containing NaOH. Each implant was afterward immersed in a weak acid solution (5% H2SO4), neutralizing the alkaline film at the surface. Initial electrolytic strike plating with gold (~0.5 μm) was carried out in an acid gold electrolyte based upon a gold tetrachloride complex AuCl4− to improve the adhesion of the following gold layer. After assuring that the initial strike plating was made properly upon the titanium surface, a 100% pure gold coating with low mechanical stress was applied by deposition of a 3- to 4-μm-thick gold layer from a weak acid gold bath based upon AuCN. Between each of the process steps, careful rinse in pure water was carried out to avoid contamination. The gold plating was carried out in The Technical University of Denmark.

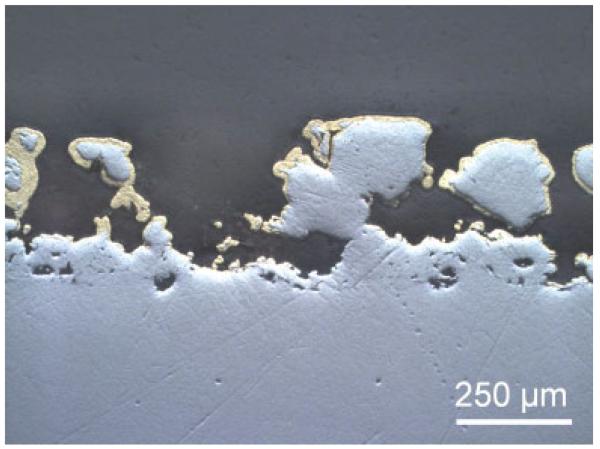

Figure 2 shows that this plating process guaranteed that the electrolytic gold layer was applied on the surface and also in the porous interlocks without disturbing the porosity of the implant. Holes in the gold plating were, however, quite common.

Figure 2.

Longitudinal section through a gold-coated implant shows the thickness and variation of the Au coating. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

Scanning electron microscopy and energy dispersive spectroscopy confirmed the base implant characterization stated by the supplier, and that the gold layer was correctly plated at the surface of half of the implants (data not shown).

Specimen preparation

After 4 weeks of observation, the animals were euthanized, and the proximal part of the tibia was excised and cleaned, and thereafter stored at −20°C. Two standardized 5.0-mm sections perpendicular to the long axis of the implant were cut on a water-cooled diamond band saw (Exakt-Cutting Grinding System, Exakt Apparatebau, Norderstedt, Germany). The first section closest to the bone surface was stored at −20°C and used for push-out testing. The section with the remaining 5.0 mm of the implant was fixed in 70% ethanol for histomorphometrical examination.

Mechanical testing

Implants were tested to failure by axial push-out test on a MTS Bionics Test Machine. The specimen was placed on a metal support jig with a 7.4-mm diameter central opening. The implant was centralized over the opening thereby assuring a 0.7 mm distance between the implant and the support jig, as recommended.16 The displacement rate was 5 mm/min with a 10 kN load cell. Load and deformation were registered by a personal computer. Each specimen’s length and diameter were measured with a micrometer and used to normalize push-out parameters. Ultimate shear strength (σu) was determined from the maximal force (F) and was calculated as σu = F/πDL, where D was the average diameter and L was the height of the implant. Apparent stiffness was obtained from the slope of the curve and calculated as E = (δF/πDL)/δT, where T was the displacement. Energy absorption was calculated from the area beneath the curve until failure.

Histological preparation

The tissue blocks with the implants were dehydrated gradually in ethanol (70–100%) containing basic fuchsine, and embedded in polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA).17 Before making the sections, each implant was randomly rotated around its long axis, ensuring uniformly randomized sections optimizing the stereological analysis. Vertical sections were cut parallel to the axis with a hard tissue microtome (KDG-95, MeProTech, Heerhugowaard, The Netherlands) around the center part of each implant as described.18 Four 30-lm thick sections were cut with a distance of 420 lm and counterstained with 2% light green (BDH Laboratory Supplies, Poole, England). This procedure stains bone (green) and nonmineralized tissue (red).

Histological evaluation

Blinded histomorphometrical analysis was done using a stereological software program (CAST-grid Olympus Denmark A/S, Ballerup, Denmark). Fields of vision from a light microscope were captured on a computer monitor, and a user-specified grid was superimposed on the microscopic fields. Four vertical sections representative of each implant were analyzed and cumulated. The specimen preparation procedure and the grid system made it possible to calculate unbiased estimates, even though anisotropy in cancellous bone exists.

Surface ongrowth was defined as implant surface in direct contact with tissue and was determined using sine-weighted lines. Approximately 930 intersections were counted per implant (range 625:1892). Volume density fractions were counted by point counting in zones of 0–500 μm (inner zone) and 500–1000 μm (outer zone) from the implant. Five hundred fifty-two points (range 419:825) were counted in the inner zone and 619 points (range 390:980) in the outer zone. We distinguished between woven bone, lamellar bone, bone marrow, and fibrous tissue. Woven bone and lamellar bone were diagnosed based on their morphological appearance.

Autometallographic development

An extrasimilar Au-coated implant from the same batch was used to verify gold ion release in bone with the use of autometallographic (AMG) silver enhancement tracing. The tissue block was embedded in PMMA as the histological preparation, although without basic fuchsin. Vertical sections of 30-μm thicknesses were cut and placed on Farmer-cleaned glass slides. The slides were placed in Farmer-cleaned jars and poured with the AMG developer and placed in a water bath at 26°C on an electric device that shooks the jars gently. A dark hood covered the entire set-up throughout the actual procedure. The AMG development was stopped after 60 min by replacing the developer with a 5% sodium thiosulfate solution for 10 min (AMG stop bath). The jars were then placed under gently running ion-exchange water for 5 min. The glass slides were dipped in a 2% Farmer solution for 10–30 s and rinsed in distilled water.19

The AMG developer (pH 3.8)

The AMG developer consists of a 60-mL gum arabic solution and 10 mL sodium citrate buffer (25.5 g of citric acid 1 H2O 23.5 g sodium citrate 2 H2O to 100 mL distilled water), 15 mL reductor (0.85 g of hydroquinone dissolved in 15 mL distilled water at 40°C), and a 15 mL solution containing silver ions (0.12 g silver lactate in 15 mL distilled water at 40°C) added immediately before use while thoroughly stirring the AMG solution.20

Statistics

Data were found to be normally distributed. Student’s paired t-test was used to test for differences between treatment groups. Two-tailed p-values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Animals

No PO complications were seen. Pain relief with 0.01 mg/kg/day buprenex (0.3 mg/mL; buprenophine hydrochloride) was given twice a day for the first and second PO day, and once for the third PO day or as needed, and all dogs were fully weight-bearing within 2 days after surgery. All animals completed the observation period of 4 weeks. No clinical signs of infection were observed at the time of termination, and the dogs behaved normally and remained healthy.

Mechanical results

The biomechanical results are shown in Table 1. The gold-coated implants resulted in a less-efficient mechanical fixation compared to the control group. Two of three parameters were statistically significantly decreased with a reduction of 40% (p = 0.045) in ultimate shear strength until failure and almost 49% (p = 0.017) decrease in maximum shear stiffness.

TABLE I. Biomechanical Results are Depicted With Absolute Mean Values for Each Surface Group.

| Ult. Shear Strength (MPa) | Max. Shear Stiffness (kPa/mm) | Total Energy Absorption (J/m2) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gold implants | 3.15 (1.49–4.35) | 16.2 (9.6–21.9) | 752 (239–1051) |

| Control implants | 4.75 (2.60–6.75) | 34.8 (15.3–51.0) | 651 (324–931) |

| Gold/control (%) | 60.8 | 51.8 | 91.4 |

| Significant (*) | p = 0.045* | p = 0.017* | p = 0.808 |

The relative median ratio is shown and the values in parentheses show 95% CI.

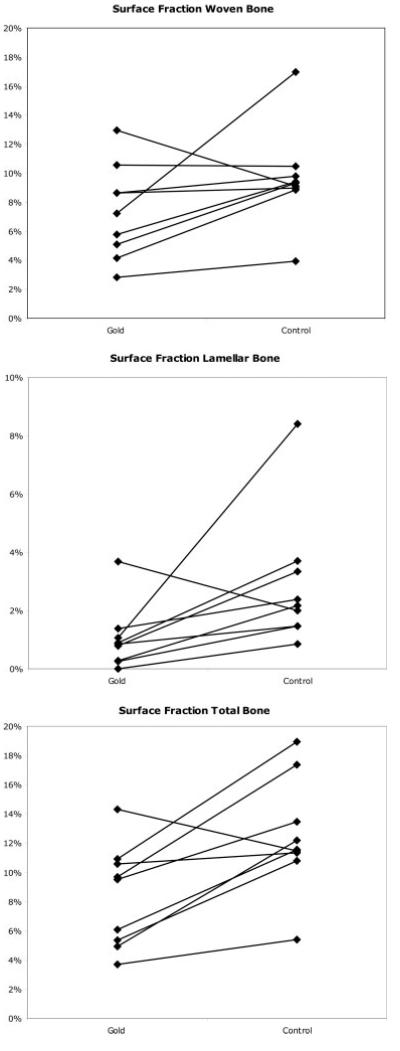

Histomorphometrical results

The paired results are depicted in Figure 3(a–c). We found a statistically significant difference between the two groups at the surface of the implants. The group with the gold implants showed 28% (p = 0.045) less woven bone in contact with implant compared to the standard Ti implants. We also found a 78% (p = 0.004) reduction of lamellar bone having contact with bone in the gold group. This resulted in a 35% (p = 0.005) reduction in overall total bone-to-implant contact using gold implants. No differences were seen in periimplant tissue.

Figure 3.

(a) The figure shows the fraction of woven bone-to-implant contact. Paired results (the two implants in the same animal) are connected with a line. (b) The figure shows the fraction of lamellar bone-to-implant contact. Paired results (the two implants in the same animal) are connected with a line. (c) The figure shows the fraction of total bone-to-implant contact. Paired results (the two implants in the same animal) are connected with a line.

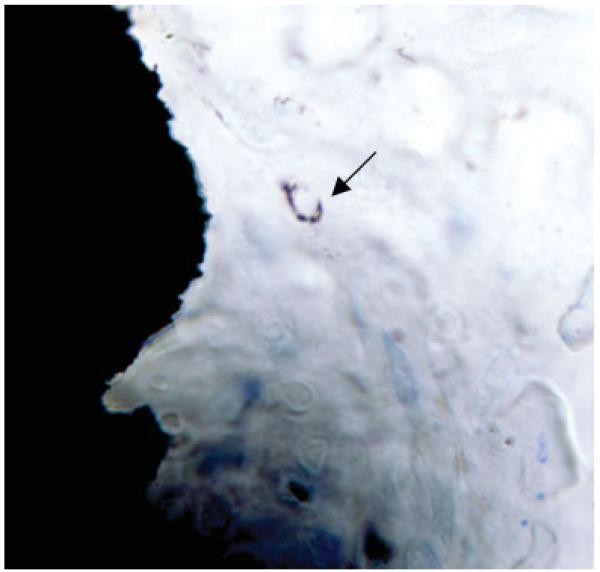

Autometallography

The thickness of the sections prevented satisfactory analysis of the cells adhering to the implant surface and the cells in the implant-bone zone. However, AMG revealed a release and uptake of gold ions in a small number of scattered cells most likely to be macrophages. AMG shows that some gold ions were released into the periimplant space, where they were taken up most likely by macrophages (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

A representative section of the implant surface and the periimplant tissue. The arrow marks the uptake of gold ions. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

DISCUSSION

We examined the effects of complete surface gold coating, that is gilding, of experimental Ti implants as compared to control Ti implants. Biomechanical implant fixation and stereological evaluation of bone-to-implant contact and periimplant bone density were used as parameters. The gold-coated implants showed poorer mechanical fixation and less direct bone-to-implant contact compared to control Ti implants. However, the AMG visualization of the ion release by the gilded implants hint that gold ions released from, for example, gold-dotted implants might have a beneficial effect as a long-term suppressor of inflammation in the periimplant zone, without compromising the primary implant fixation. The clinical ramifications of such possibilities make further research meaningful; however, it is recognized that strong and long-lasting mechanical fixation is a prime goal for improving implant longevity.

Canines were chosen as experimental animals because of the resemblance between human and canine bone in terms of trabecular density and orientation.21 The proximal part of tibia was chosen because of the large amount of trabecular bone in this region. As in a clinical setting, implants were inserted press fit in a slightly undersized drill hole. Initial anchorage of this type of press-fit implant is at first trabecular, but after initial bone remodeling, the implant’s strength and fixation is dependent on new bone formation and osseointegration.22 Osseointegration is related to the surface area of the implant and implant porosity. The gold coating is only a few microns thick. Therefore, the influence on the implant porosity is so small that we consider the surface texture of the gold-coated implants comparable to our control Ti implants. The paired study design allowed gold and control implants to be compared on the same animal, and the number of animals needed was thereby significantly reduced. The implants were unloaded and results are thereby limited, as the effects of weight-bearing conditions are not addressed.

Early primary fixation is essential in long-term survival in human prostheses.4,5 Four-week observation time was chosen because of previous authors’ experiences with this model and their ability to show differences in early fixation in this period.17

Biomechanical fixation is influenced by the architecture and structure of bone and the bone’s mineral composition.23 Failure in implant fixation during biomechanical push-out test can be related to various factors, including the amount of bone and its bony anchorage of the implant or bone density and mineral composition in periimplant tissue. The histological results suggest that the reduced amount of both woven and lamellar bone in contact with the gilded implants are the main reason for the reduced biomechanical results, since the architecture did not vary much within the same animal. Total bone-to-implant contact was reduced by 35% (p = 0.005) and replaced with bone marrow cells, emphasizing the relation between bony anchorage and mechanical stability.

A plausible scenario is that gold-coated implants reduced growth of the osteoblasts responsible for bone remodeling, resulting in a reduced total bone-to-implant contact. Cortizo et al. found no significant differences in proliferation or cell survival when subjecting osteoblast-like cells to a number of different metals including gold and titanium.24 However, the study showed a trend that Ti induced more osteo-blast-like cell proliferation than gold.

The slightly better compatibility of Ti surfaces compared to gold surfaces could in part explain our results. However, the main explanation could very well be an immune-modulating response caused by gold ions liberated from the implant. The antiinflammatory effects of gold ions have been supported by several studies.11,25,26 It has also been recently demonstrated that gold ions suppress hyaluronan accumulation by blocking interleukin (IL)-1β-induced hyaluronan synthase-1 transcription. The study also showed that in fibroblast-like synoviocytes, gold ions act as a specific COX-2 transcriptional repressor in that IL-1β-induced COX-2 transcription is blocked, whereas COX-1 transcription and translation are unaffected.27 These recent data together with the fact that gold ions block NF-κB-DNA interaction in addition to other transcription factors implicated in inflammatory events such as AP-1 and STAT3 make research in the use of metallic gold as a local anti-inflammatory mediator on implants, both theoretically and clinically, interesting.

The local immune modulatory action of gold ions is generated by the application of metallic gold on porous-coated Ti implants. Metallic gold releases gold ions both in vivo and in vitro by a process called “dissolucytosis.”28 It has been shown that the dissolucytes, here macrophages, both in vitro and in vivo attack the metallic surface.13 The dissolucytosis takes place by a nanosized film, the dissolution membrane, being established on the metallic surface. Thereafter, the macrophages, most likely by controlling the pH, oxygen tension, and level of cyanide ions, cause the liberation of gold ions into the dissolution membrane, that is the dissolution process takes place outside the cells. The gold ions can subsequently be reduced to metallic gold atoms that cluster in nanoparticles that can be traced by AMG. Our AMG tracing of gold ions confirms the local ion release at the surface of the implants and the uptake in adjacent cells.

The relationship between inflammation and bone healing, especially the benefits of PO inflammatory response have been debated by several authors. Gerstenfeld et al. showed reduced bone healing after fractures, using NSAID.29 Several other animal studies have also showed reduced bone formation by both NSAID and COX knockout mice.30-32 These were all systemic inhibitory effects on the inflammatory response, whilst our surface coating is considered a local treatment. This local action has also put in effect intracellular in inhibiting transcription of cellular genes instead of inhibition of the cyclooxygenase enzyme. However, it is still unclear whether it is only inflammatory cells that are affected by our coating or whether osteoblasts around the implant are also affected.

The literature already suggests that central inhibition of the posttraumatic inflammation process is not beneficial for bone healing. We instead wished to modulate the local inflammatory response in order to avoid influencing bone formation. In our study, we may have used too much gold by gilding the surface. A dosage–response study is needed in order to establish the exact amount of gold dotted on the implant surface that will have no influence on the fixation, but endow the implant with a permanent inflammatory suppressing quality. This would combine the biocompatible capabilities of Ti with gold’s antiinflammatory capacity and cause suppression of aseptic inflammation around the implant, that otherwise in the long run might result in implant loosening.

Aseptic loosening due to increased osteolysis is closely linked to activation of osteoclasts mainly because of macrophage cytokine secretion, particularly TNF-α, but also several ILs.33 It has been shown that activated macrophages and fibroblasts are related to loosening of prostheses34 and Yoshida et al. have shown that fibroblasts pretreated with the gold compound aurothioglucose secrete less IL-6 and IL-8. Reduction or completely inhibition of fibrous tissue around the implant is an important aspect in prevention of aseptic loosening. Since the press-fit inserted implants leave no room for fibrous tissue formation in only 4-week observation time and without the exacerbation of relative implant motion and loading, a follow-up study is underway using a gap model investigating metallic gold’s influence on this matter. This study will contribute to clarify the clinical possibilities of metallic gold in orthopedic context.

CONCLUSION

This study reveals that complete gold coating of implants is not favorable because of poor initial implant fixation. The clear impact of gilding also indicates that the immunosuppressive qualities of gold should be further studied in order to evaluate the possibility of using gold dotting of implants as a way of maintaining good adequate early implant fixation and increasing implant longevity by suppressing aseptic loosening.

We thank Anette Milton and Jane Pauli, Orthopaedic Research Laboratory, Aarhus University Hospital, and Dorete Jensen, Aarhus University, for their technical expertise, and Xinqian Chen, MD, Orthopaedic Biomechanics Laboratory, Minneapolis, for surgical assistance. Biomet Inc., USA kindly provided all base implants.

Acknowledgments

Contract grant sponsor: The Danish Rheumatism Association

Contract grant sponsor: Helga and Peter Kornings Foundation

Contract grant sponsor: The Orthopedic Research Foundation, Aarhus

Contract grant sponsor: Danish Orthopedic Society

References

- 1.Heisel C, Silva M, Schmalzried TP. Bearing surface options for total hip replacement in young patients. Instr Course Lect. 2004;53:49–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pedersen AB, Johnsen SP, Overgaard S, Soballe K, Sorensen HT, Lucht U. Total hip arthroplasty in Denmark: Incidence of primary operations and revisions during 1996-2002 and estimated future demands. Acta Orthop. 2005;76:182–189. doi: 10.1080/00016470510030553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eskelinen A, Remes V, Helenius I, Pulkkinen P, Nevalainen J, Paavolainen P. Uncemented total hip arthroplasty for primary osteoarthritis in young patients: A mid-to long-term follow-up study from the Finnish Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop. 2006;77:57–70. doi: 10.1080/17453670610045704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karrholm J, Herberts P, Hultmark P, Malchau H, Nivbrant B, Thanner J. Radiostereometry of hip prostheses. Review of methodology and clinical results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;344:94–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryd L, Albrektsson BE, Carlsson L, Dansgard F, Herberts P, Lindstrand A, Regner L, Toksvig-Larsen S. Roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis as a predictor of mechanical loosening of knee prostheses. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77:377–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elmengaard B, Bechtold JE, Soballe K. In vivo study of the effect of RGD treatment on bone ongrowth on press-fit titanium alloy implants. Biomaterials. 2005;26:3521–3526. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buvanendran A, Kroin JS, Berger RA, Hallab NJ, Saha C, Negrescu C, Moric M, Caicedo MS, Tuman KJ. Upregulation of prostaglandin E2 and interleukins in the central nervous system and peripheral tissue during and after surgery in humans. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:403–410. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200603000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klippel JH, Dieppe PA. Rheumatology. Mosby; London: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Persellin RH, Ziff M. The effect of gold salt on lysosomal enzymes of the peritoneal macrophage. Arthritis Rheum. 1966;9:57–65. doi: 10.1002/art.1780090107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang JP, Merin JP, Nakano T, Kato T, Kitade Y, Okamoto T. Inhibition of the DNA-binding activity of NF-κ B by gold compounds in vitro. FEBS Lett. 1995;361:89–96. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00157-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshida S, Kato T, Sakurada S, Kurono C, Yang JP, Matsui N, Soji T, Okamoto T. Inhibition of IL-6 and IL-8 induction from cultured rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts by treatment with aurothioglucose. Int Immunol. 1999;11:151–158. doi: 10.1093/intimm/11.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tozman EC, Gottlieb NL. Adverse reactions with oral and parenteral gold preparations. Med Toxicol. 1987;2:177–189. doi: 10.1007/BF03259863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Danscher G. In vivo liberation of gold ions from gold implants. Autometallographic tracing of gold in cells adjacent to metallic gold. Histochem Cell Biol. 2002;117:447–452. doi: 10.1007/s00418-002-0400-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schlesinger M, Paunovic M. Modern Electroplating. Wiley; New York, NY: [Google Scholar]

- 15.Møller P. Ingeniøren/Book: Ingeniøren/Book. 2003. Overfladeteknologi Kbh. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dhert WJ, Verheyen CC, Braak LH, de Wijn JR, Klein CP, de Groot K, Rozing PM. A finite element analysis of the push-out test: Influence of test conditions. J. Biomed Mater Res. 1992;26:119–130. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820260111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jakobsen T, Kold S, Bechtold JE, Elmengaard B, Soballe K. Effect of topical alendronate treatment on fixation of implants inserted with bone compaction. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;444:229–234. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000191273.34786.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Overgaard S, Soballe K, Jorgen H, Gundersen G. Efficiency of systematic sampling in histomorphometric bone research illustrated by hydroxyapatite-coated implants: Optimizing the stereological vertical-section design. J. Orthop Res. 2000;18:313–321. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100180221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Danscher G, Norgaard JO, Baatrup E. Autometallography: Tissue metals demonstrated by a silver enhancement kit. Histochemistry. 1987;86:465–469. doi: 10.1007/BF00500618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stoltenberg M, Danscher G. Histochemical differentiation of autometallographically traceable metals (Au, Ag, Hg, Bi, Zn): Protocols for chemical removal of separate autometallographic metal clusters in Epon sections. Histochem J. 2000;32:645–652. doi: 10.1023/a:1004115130843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aerssens J, Boonen S, Lowet G, Dequeker J. Interspecies differences in bone composition, density, and quality: Potential implications for in vivo bone research. Endocrinology. 1998;139:663–670. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.2.5751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dhert WJ, Thomsen P, Blomgren AK, Esposito M, Ericson LE, Verbout AJ. Integration of press-fit implants in cortical bone: A study on interface kinetics. J Biomed Mater Res. 1998;41:574–583. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(19980915)41:4<574::aid-jbm9>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kienapfel H, Sprey C, Wilke A, Griss P. Implant fixation by bone ingrowth. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14:355–368. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(99)90063-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cortizo MC, De Mele MF, Cortizo AM. Metallic dental material biocompatibility in osteoblastlike cells: Correlation with metal ion release. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2004;100:151–168. doi: 10.1385/bter:100:2:151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burmester GR. Molecular mechanisms of action of gold in treatment of rheumatoid arthritis—[An update] Z Rheumatol. 2001;60:167–173. doi: 10.1007/s003930170065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rau R. Have traditional DMARDs had their day? Effective-ness of parenteral gold compared to biologic agents. Clin Rheumatol. 2005;24:189–202. doi: 10.1007/s10067-004-0869-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stuhlmeier KM. The anti-rheumatic gold salt aurothiomalate suppresses interleukin-1β-induced hyaluronan accumulation by blocking HAS1 transcription and by acting as a COX-2 transcriptional repressor. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:2250–2258. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605011200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larsen A, Stoltenberg M, Danscher G. In vitro liberation of charged gold atoms: Autometallographic tracing of gold ions released by macrophages grown on metallic gold surfaces. Histochem Cell Biol. 2007;128:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s00418-007-0295-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerstenfeld LC, Thiede M, Seibert K, Mielke C, Phippard D, Svagr B, Cullinane D, Einhorn TA. Differential inhibition of fracture healing by non-selective and cyclooxygenase-2 selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Orthop Res. 2003;21:670–675. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(03)00003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aspenberg P. Drugs and fracture repair. Acta Orthop. 2005;76:741–748. doi: 10.1080/17453670510045318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aspenberg P. Postoperative Cox inhibitors and late prosthetic loosening—Suspicion increases! Acta Orthop. 2005;76:733–734. doi: 10.1080/17453670510045291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Persson PE, Nilsson OS, Berggren AM. Do non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs cause endoprosthetic loosening? A 10-year follow-up of a randomized trial on ibuprofen for prevention of heterotopic ossification after hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop. 2005;76:735–740. doi: 10.1080/17453670510045309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ingram JH, Stone M, Fisher J, Ingham E. The influence of molecular weight, crosslinking and counterface roughness on TNF-α production by macrophages in response to ultra high molecular weight polyethylene particles. Biomaterials. 2004;25:3511–3522. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Konttinen YT, Xu JW, Patiala H, Imai S, Waris V, Li TF, Goodman SB, Nordsletten L, Santavirta S. Cytokines in aseptic loosening of total hip replacement. Curr Orthopaed. 1997;11:40–47. [Google Scholar]