Abstract.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) modulates processing in the human brain and is therefore of interest as a treatment modality for neurologic conditions. During TMS administration, an electric current passing through a coil on the scalp creates a rapidly varying magnetic field that induces currents in the cerebral cortex. The effects of low-frequency (1 Hz), repetitive TMS () on motor cortex cerebral blood flow (CBF) and tissue oxygenation in seven healthy adults, during/after 20 min stimulation, is reported. Noninvasive optical methods are employed: diffuse correlation spectroscopy (DCS) for blood flow and diffuse optical spectroscopy (DOS) for hemoglobin concentrations. A significant increase in median CBF (33%) on the side ipsilateral to stimulation was observed during and persisted after discontinuation. The measured hemodynamic parameter variations enabled computation of relative changes in cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen consumption during , which increased significantly (28%) in the stimulated hemisphere. By contrast, hemodynamic changes from baseline were not observed contralateral to administration (all parameters, ). In total, these findings provide new information about hemodynamic/metabolic responses to low-frequency and, importantly, demonstrate the feasibility of DCS/DOS for noninvasive monitoring of TMS-induced physiologic effects.

Keywords: transcranial magnetic stimulation, diffuse optical spectroscopy, diffuse correlation spectroscopy, brain function

1. Introduction

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is a versatile, noninvasive, and potentially therapeutic technique that enables investigators to modulate processing in the human brain.1 During TMS administration, the rapid discharge of an electric current through a coil of wire placed near the head surface generates a magnetic flux that, in turn, induces a weak current in the cortex. This weak current is sufficient to depolarize neuronal membranes and generate action potentials, and these effects can be localized based on coil configuration and placement. TMS has become an important investigative tool in cognitive neuroscience.2 It can be used to transiently create so-called “virtual lesions” that temporarily and focally disrupt neural processing,3 and it can be used in a repetitive manner to induce more sustained effects on neural activity. The latter approach has been explored as a possible treatment modality for a wide range of neurologic and psychiatric conditions.4,5 While a variety of TMS intensities and frequencies can be employed to transiently disrupt cortical processing, arguably, the most common approach with patients in both experimental and therapeutic settings has been to administer low-frequency (1 Hz) repetitive TMS () for relatively long durations (i.e., 10 to 20 min); this treatment scheme has been associated with inhibitory effects on cortical physiology and on behaviors that persist after discontinuation of stimulation.6,7

Although TMS has long been employed as an investigational and therapeutic technique, the fundamental principles underlying its cortical physiology effects are not fully understood. To date, hemodynamic and metabolic changes induced by TMS over the motor cortex have been studied using neuroimaging techniques such as positron emission computed tomography (PET), single-photon emission computed tomography, and functional magnetic resonance imaging. The results of these investigations, however, are varied and not fully understood. For example, regional cerebral blood flow (CBF) and metabolic activity in the motor cortex during and after TMS have been reported to increase,8–12 to decrease,13 and to show no change.14 These different responses might be caused by a variation in the intensity, frequency, number of pulses, and/or direction of induced current in the brain. Interestingly, some of these studies also suggest that stimulation of the primary motor cortex can produce changes in activation in homotopic regions of the contralateral hemisphere.9,15,16

Diffuse optical methods provide a potentially valuable and relatively untapped technique for investigation of cerebral hemodynamic responses during . Diffuse optical methods employ near-infrared photons (650 to 900 nm) that diffuse through tissue and can be detected millimeters to centimeters away from the source.17–19 These optical techniques offer several advantages as tools for probing cortical physiology, including portability, excellent temporal resolution, and the ability to probe deep tissues noninvasively (e.g., through intact skull).

Diffuse optical spectroscopy (DOS), also termed near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), is widely used in neuroscience. In DOS, the interaction of light with the main chromophores in the tissue, oxy-hemoglobin () and deoxy-hemoglobin (Hb), provides information about and Hb concentrations, total hemoglobin concentration (HbT), tissue blood oxygen saturation (), and changes thereof. DOS has previously been applied during using various stimulation protocols, but except for one recent study,13 all DOS experiments have focused on hemodynamic changes during short periods of administration, or after single pulses. Kozel et al., for example, reported a decrease in in both ipsilateral and contralateral sides of the motor cortices when stimulating at 1 Hz for a short period of time (10 s).20 Using a similar protocol, a recent study by Tian et al. demonstrated that such decreases have high reliability at the group level.21 Conversely, single-pulse stimulation over the motor cortex has been reported to cause to increase at TMS intensities of 90 and 110% of the active motor threshold (AMT) intensity,22 though no changes were observed at 140% of the AMT.23 Increases in during were also reported when stimulating the frontal cortex of healthy subjects.24 Finally, a recent report suggested that the DOS signal may also include components that arise from local effects on the vasculature and/or global circulatory effects that are induced by TMS.25 Presently, the wide variety of cortical regions analyzed under different stimulation protocols makes collective interpretation of all of the DOS results difficult.

Our study differs from previous optical work in that an emerging diffuse optical technique sensitive to CBF, called diffuse correlation spectroscopy (DCS), is also employed. DCS quantifies the temporal fluctuations of light that has traveled through tissue.18,26–28 The fluctuation signal provides access to blood flow changes via a measured parameter called the blood flow index (BFI). Variation in the BFI readily provides information about changes in microvascular perfusion within the brain, for example, due to functional perturbations.29,30 The technique has been successfully validated in animals and in humans through comparison with other techniques such as arterial spin-labeled magnetic resonance imaging (ASL-MRI),31,32 Xenon-CT,33 transcranial Doppler ultrasound,34,35 and a time-resolved near-infrared technique using indocyanine green as a flow tracer.36

The current study combines DCS and DOS methods into a single instrument to characterize the effects of low-frequency on cerebral hemodynamics over the primary motor cortex of healthy adults. The study explores clinically relevant, long (20 min) time periods of simultaneous administration for the first time. Relative changes in perfusion and oxygenation were measured during and after administration, in both ipsilateral and contralateral sites with respect to stimulation. Further, the resultant combination of concentration and flow data enabled us to make inferences about the relative change in cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen consumption (). Across all subjects, we found consistent and robust increases in CBF and oxygen metabolism in the ipsilateral hemisphere during 1 Hz , while no statistically significant increases were observed in the contralateral side, when compared to the baseline. The stimulation elicited a sustained hemodynamic increase in the ipsilateral motor cortex that did not return to baseline even 10 min after discontinuation of stimulation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

Eight healthy right-handed subjects (seven male; mean (standard deviation) age of 39 (11) years; age to 71 years) were initially recruited in the study. One of the subjects had a substantial amount of data missing (e.g., contralateral data) due to technical difficulties and was excluded from data analysis. Therefore, we present results obtained from seven subjects. None of the subjects had a prior history of neurologic conditions or were taking medications known to lower seizure thresholds. All subjects provided written and formal consent, and all protocols and procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Pennsylvania, where the experiments were carried out.

2.2. Experiment Procedures

Each subject participated in a single stimulation session. Subjects were instructed to sit in a chair and to rest their head on a chin-rest. A Brainsight neuronavigational system (Rogue Research, Montreal) was employed to coregister data and TMS instrumentation with a previously obtained high-resolution MRI of each subject’s brain and to aid in precise placement of the optical probes. Optical probes were placed bilaterally and symmetrically on M1 and were held in place with a plastic strap. For both motor threshold determination and subsequent , magnetic stimulation was delivered by placing the TMS coil over the optical probes. The coil was manually held in place just above the optical probe throughout each session. The Brainsight system was employed to ensure that the TMS coil location was held at an approximately constant position throughout data collection. The coil position over the optical probe was continuously monitored, and the coil position was readjusted when the coil was found to move more than 5 mm from the target.

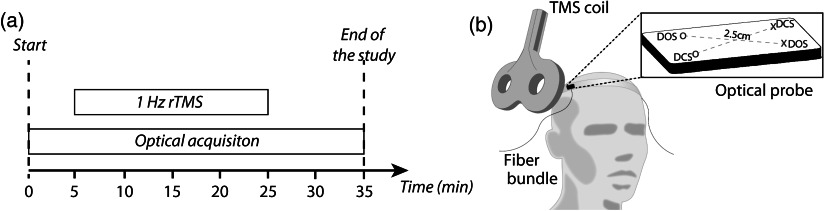

The session protocol was explained to every subject prior to data acquisition. The session began with a 5-min baseline measurement period during which the TMS coil was placed, but no TMS was administered. Next, was administered for 20 min followed by a target 10-min recovery period during which the TMS coil was again kept in position but no stimulation was administered. Optical data were collected throughout the whole session. Session events are summarized in Fig. 1(a).

Fig. 1.

(a) Experiment protocol timeline summarizing the session events. (b) Drawing representing the optical measurement during the session, with the optical probe used in each hemisphere depicted schematically (the cross and circle symbols represent sources and detectors, respectively, and the dashed lines represent the source–detector pair combinations). The probe thus contains one source–detector channel for DOS and one source–detector channel for DCS (i.e., one DOS and one DCS channel per hemisphere). The probe thickness was approximately 1.9 mm, and the source–detector separation was 2.5 cm for both DCS and DOS channels.

2.3. Methods

Stimulation was administered with a Magstim Rapid transcranial magnetic stimulator connected to a 70-mm diameter figure-of-eight coil (Magstim, Whitland, UK). As described above, the Brainsight neuronavigational system was employed to guide placement of the TMS coil precisely over the hand region of the motor cortex (M1) in the left hemisphere. Motor responses were assessed by visualizing movements of the right hand associated with single pulses of TMS.37 Any perceptible movement of the thumb, wrist, or finger was counted as a motor response. In line with prior studies using visualized motor responses, the resting motor threshold (RMT) was considered to be the lowest intensity at which movement could be detected at least three times in five trials.38 This RMT value was determined for each subject by starting at suprathreshold stimulation intensity and then decreasing the percentage of total machine output by steps of 1 to 2%.

Following determination of RMT, 1200 pulses of repetitive stimulation were administered over the hand representation of the primary motor cortex on the left hemisphere with an intensity of 95% of RMT and at a frequency of 1 Hz. The stimulation intensity of 95% RMT was chosen so that would not induce hand twitching but would still be very close to the subject’s RMT. At this intensity, no movement was observed in the intrinsic hand muscles of any of the subjects. Across the eight subjects, 95% RMT corresponded to a median (interquartile) intensity of 66 (54, 72) % of machine output.

2.4. Diffuse Optical Methods

Optical measurements were performed with a hybrid device of our own design, which contained both DCS and DOS modules. The DCS module consisted of two continuous-wave, long coherence length (), 785-nm lasers (CrystaLaser Inc., Reno, NV) and two arrays of four avalanche photodiodes (PerkinElmer, Canada). The detection system fed an eight-channel autocorrelator (Correlator.com, Bridgewater, New Jersey) that computed the temporal autocorrelation function of the detected light intensity over an integration time of 2.5 s.

The DOS module employed three laser diodes at differing wavelengths (685, 785, and 830 nm; Thorlabs, Newton, New Jersey) that were amplitude-modulated at 70 MHz by low-noise RF signal oscillators (13 dB; Moorpark, California). The laser outputs were connected to a fast optical switch (switch time ; Dicon Fiberoptics, Richmond, California) in order to illuminate tissue at different scalp positions. Optical fibers delivered and collected light to and from the tissue. Light collected from the scalp was delivered to two photomultiplier tubes (PMTs; Hamamatsu Corp., Japan). The signal from each PMT was amplified and alternately switched into the in-phase/quadrature (I/Q) demodulators using electronic switches (Mini-circuits, Brooklyn, New York) to decode the three modulated source signals. A pair of low-pass filters with a cutoff frequency of 80 Hz was connected to the output of each I/Q demodulator in order to filter out high-frequency signals. Finally, signals were digitized by a 16-channel 16-bit data acquisition board (National Instruments, Austin, Texas). The sampling rate of the DOS module was set at 400 ms.

The DCS and DOS modules operate in toggle-switch mode, i.e., they operate independent of one another. The DCS module is off when the DOS module is on, and vice versa. Although no significant cross-talk between the modules has been observed, it is possible that large changes in the blood volume (proportional to the sum of and Hb concentrations) can change the fraction of photon scattering events and therefore change the blood flow signal. However, this effect should be small, because the blood volume changes measured throughout the experiment are small. (Note that DOS measurements were used to correct for scattering fraction in the DCS measurements, as explained in the next section.) A laptop computer controlled operation of the DCS and DOS modules and recorded data. The total cycle (DCS and DOS) of data acquisition was in duration.

Two thin, custom-made optical probes (FiberOptic Systems Inc., Simi Valley, California) were employed in this study (one for each hemisphere). Each probe held four optical fibers that were polished at 45 deg on the subject end, so that they work like the 90 deg bend fibers usually employed in DOS/DCS experiments. This approach permitted design of a thin probe that could be readily placed adjacent to the forehead [Fig. 1(b)]. With this configuration, the distance from the TMS coil to the scalp was approximately 5 to 7 mm. In order to account for the possible effects of this additional thickness, all motor thresholds were measured in situ with the probe in place. Two multimode fibers (200 μm diameter) were used for both DOS and DCS sources. A 400-μm diameter multimode fiber was used for DOS detection. The DCS detection fiber system was composed of a bundle of four single-mode fibers, each with 5 μm core diameter, in order to increase DCS signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). The numerical aperture (NA) of the multimode fibers was 0.37, and the NA of the single-mode fibers was 0.10. The fibers were approximately 10 m long, and the probe pad thickness was smaller than 2 mm. The fiber length was chosen for convenience, since their length did not affect measurement of temporal resolution. (Note that physiological changes are slow compared to light transit time through the fibers, and the group velocity dispersion in the fiber is of negligible importance for our nearly monochromatic light beams.) The source–detector separation was fixed at 2.5 cm, and the source–detector map was mounted at a fixed configuration such that each pair, for both DCS and DOS, probed approximately the same spatial region.

2.5. Optical Analysis

The phase noise of the detected light in the DOS module was relatively large due to instrumental characteristics, and we were not sufficiently confident to use it for absolute measurements of hemoglobin concentrations or differential path length factor (DPF) estimation. Therefore, we opted to analyze the amplitude of the light intensity within the continuous-wave analytical approach; in this case, changes in hemoglobin concentration are derived from the data. The light amplitude for each source–detector pair at each wavelength was thus converted into relative optical density changes, and these optical density variations were converted into chromophore concentration changes. The modified Beer–Lambert law, with a DPF that varied between 5.8 and 7.4 for all the wavelengths, was employed to derive concentration changes ( and ).18,19 DPF variation was based on the slowly varying age dependence of DPF,39 extrapolated for the age range of our subjects. The hemoglobin extinction coefficients were extracted from tabulated values available on the web (http://omlc.ogi.edu/spectra/hemoglobin/summary.html). The change in total hemoglobin concentration () was determined as the sum of and . Optical data that contained apparent artifacts due to relative motion between the probe and the scalp, and which were corroborated by independent visual inspection of the subject during the experiment run, were discarded. These artifacts were never more than 10% of the total data acquired per subject.

Relative changes in CBF () were estimated from DCS data by extracting a BFI at each time point [, where denotes the baseline period]. Changes in CBF () were measured from zero [i.e., ]. The BFI was estimated by fitting the measured intensity autocorrelation function to the solution of the photon correlation diffusion equation in the semi-infinite geometry with extrapolated zero boundary conditions.18 In this work, a diffusive motion model27 was used to approximate the mean-square particle displacement of the moving red blood cells in tissue and thus derive the BFI. The changes in the absorption coefficient at 785 nm measured by DOS were used as input in the correlation diffusion equation. The goodness of fit was evaluated for each fiber at each time point, and the decay curves that failed to fit the model (i.e., curves whose fitting residuals were higher than 75% of the mean residual over the entire time-series) were discarded from the analysis. At each time point, the obtained for each fiber was averaged over all the four single-mode fibers.

2.6. Estimation of

From measurements of and oxygen extraction fraction (OEF), the relative changes of can be computed and thus accessed (indirectly).40–43 OEF is defined as the fractional conversion of oxygen concentration from arterioles to venules, i.e., , where represents the oxygen saturation in the vessel (here, can be , , or for arterioles, capillaries, and venules, respectively). OEF can thus be estimated from information about tissue hemoglobin concentration measured with DOS, by assuming a steady-state balance between oxygen concentration and hemoglobin concentration. In this case, one can think of the optical signal as a mixture of arterial, capillary, and venous blood, so that the measured tissue hemoglobin saturation can be expressed as a weighted sum of the three different compartment saturations, which leads to the following expression:41

| (1) |

where is a free parameter that indicates the percentage (fraction) of blood volume contained in the venous compartment of the vascular system. For measurements of relative changes of OEF, ; the factor in Eq. (1) divides out if we assume it is constant. (Physiologically, this implies that the fraction of blood volume in the venous compartment does not change during the perturbation.) Because we did not monitor in our experiment, we also assumed that was fixed at 100% over time for all subjects.42 Then, by using Eq. (1), can be expressed as41–43

| (2) |

where the prefix refers to relative changes (e.g., variation relative to a baseline time period). In this work, we assumed the baseline concentrations of Hb and to be approximately 40 and 60 μmol, respectively, following previous reported findings of tissue oxygen saturation and total hemoglobin concentration.44,45

2.7. Statistical Analysis

For every subject, time courses of and the changes in , Hb, and HbT concentration throughout the whole session were calculated relative to a baseline period. In order to minimize fluctuations caused by initial adjustments in the beginning of the experiment, the baseline was taken as the median of the time points obtained 3 min before beginning stimulation. The time-series were first “de-trended” by removing linear trends with a fast Fourier transformation (“detrend” function in Matlab). This scheme removes potential slow drifts that might be present in the signals. Note, however, that the coefficients from the de-trending operation on our data were very close to zero in all subjects. Then, the resulting time-series were fit to a cubic polynomial, whose coefficients were used to reconstruct the global trends of each of the hemodynamic parameters of each subject during the TMS protocol. Examples of the data and the global trends are shown in Fig. 2.

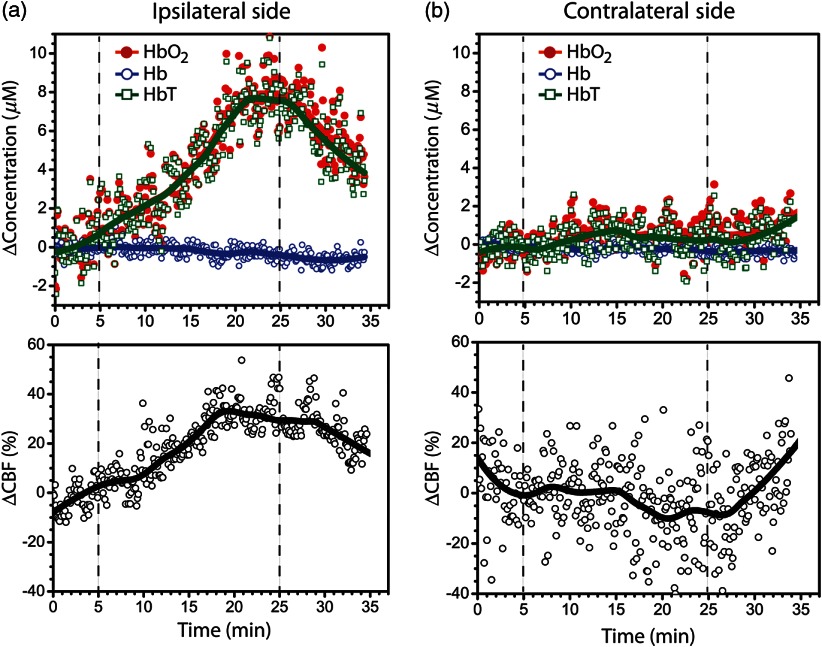

Fig. 2.

Hemoglobin concentration (top row) and blood flow (bottom row) changes in (a) ipsilateral and (b) contralateral sides of stimulation for a single subject during the whole session. The vertical dashed lines indicate the beginning and the end of administration. The thick solid lines are the global trends. CBF, cerebral blood flow; , oxy-hemoglobin concentration; Hb, deoxy-hemoglobin concentration; HbT, total hemoglobin concentration.

Changes during were calculated from the highest value during the stimulation period. Error bars for each of the estimated values were quantified by taking the standard deviation of the fluctuations of the de-trended time-series (i.e., the residuals after removing the global trends). From the temporal trends, we also averaged 1-min epochs every 4 min to build blocks at specific time periods. While the 1-min epoch was chosen arbitrarily, the interval of 4 min was chosen in order to maximize the number of epoch data points, since not all the subjects completed the target poststimulation period (i.e., 10 min poststimulation). This approach enabled us to examine common patterns in the hemodynamic response, independent of short-term temporal variations between the subjects, and to further characterize the hemodynamic response at specific time periods.

In all the procedures, data for the whole group were summarized using the median and the inter-quartile range (IQR). Nonparametric Wilcoxon signed rank tests were used to assess statistically significant differences from the baseline. All data analysis and statistics were performed with Matlab (MathWorks Inc., Natick, Massachusetts).

3. Results

All the subjects successfully completed the protocol. Clear motion artifacts, however, were detectable between 5 and 10 min after the cessation of the stimulation in five of the eight participants. These artifacts were most likely due to the difficulty subjects experienced maintaining a static head position for a prolonged period of time. Therefore, we opted to discard the last 5 min of data collection and analyzed data from all subjects until 4 min post stimulation.

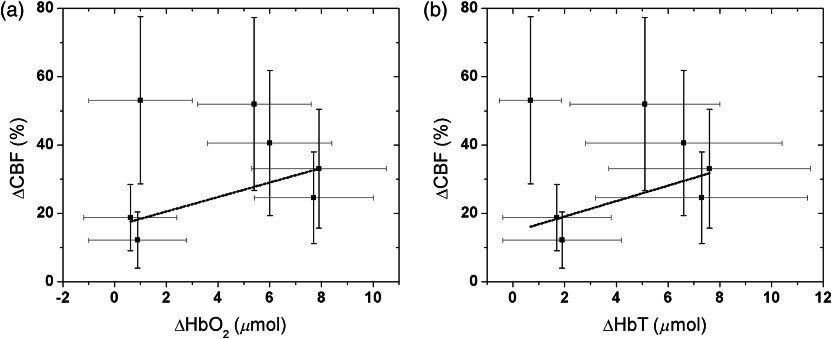

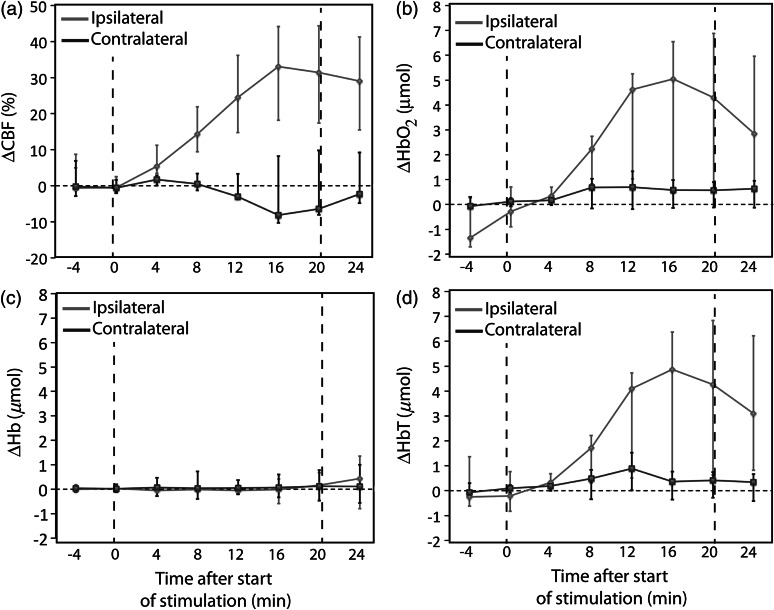

Figure 2 shows an example of a time-series of measured hemodynamic data from a single illustrative subject. Summary results from all individuals for , , and , and are shown in Table 1. During administration of , we found a significant CBF increase on the side ipsilateral to stimulation (). CBF saturated after reaching the maximum change; this plateau typically occurred between 10 and 20 min after the peak for all subjects. Across all subjects, the increase from baseline in the ipsilateral side was 33 (22, 46) % [median (IQR)]. Further, concentration in the ipsilateral side showed median increases of 5.4 (0.95, 6.9) μmol, but concentration in the ipsilateral side did not show a significant change, i.e., (, 0.85) μmol. The combination resulted in a median in the ipsilateral side of 5.1 (1.8, 7.0) μmol. Overall, we found that was moderately correlated with in the ipsilateral side of stimulation, i.e., considering the error bars for each individual subject (Fig. 3). The correlation analysis between and () yields (0.53).

Table 1.

Maximum changes during for each subject, as measured by DOS and DCS, for both ipsilateral (IL) and contralateral (CL) sides of stimulation. The numbers in parenthesis represent the error, which was estimated by the standard deviation of the fluctuations during the period.

| Subject ID | (%) | (μmol) | (μmol) | (μmol) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL | CL | IL | CL | IL | CL | IL | CL | |

| 01 | 33.1 (17.4) | (13.4) | 7.9 (2.6) | 0.88 (1.9) | (0.78) | (0.54) | 7.6 (3.9) | 0.72 (1.9) |

| 02 | 18.8 (9.7) | (10.5) | 0.61 (1.8) | 1.7 (2.8) | 1.2 (2.1) | (0.89) | 1.7 (2.1) | 1.41 (2.8) |

| 03 | 40.6 (21.2) | 13.9 (13.2) | 6.0 (2.4) | (2.7) | 0.71 (1.7) | 0.99 (1.5) | 6.6 (3.8) | (3.1) |

| 04 | 24.6 (13.4) | (8.3) | 7.7 (2.3) | 0.89 (1.4) | (1.4) | 1.06 (1.6) | 7.3 (4.1) | 1.7 (2.1) |

| 05 | 53.1 (24.5) | (13.5) | 1.0 (2.1) | 0.35 (0.59) | (1.1) | 0.38 (0.63) | 0.68 (1.2) | 0.62 (0.9) |

| 06 | 12.2 (8.2) | 9.6 (8.1) | 0.89 (1.9) | (1.4) | 0.98 (2.3) | (0.27) | 1.9 (2.3) | (1.4) |

| 07 | 52.0 (25.3) | 12.6 (10.9) | 5.4 (2.2) | 1.05 (1.8) | (0.4) | 0.58 (1.1) | 5.1 (2.9) | 1.39 (1.8) |

Note: CBF, cerebral blood flow; , oxy-hemoglobin concentration; Hb, deoxy-hemoglobin concentration; HbT, total hemoglobin concentration.

Fig. 3.

Correlation between changes in cerebral blood flow () and changes in (a) oxy-hemoglobin () and (b) total hemoglobin () concentration during on the ipsilateral side of stimulation. The lines correspond to the best linear fit considering the error bars and yielded values of 0.53 () and 0.47 ().

Though the average and for the group were nonzero, a significant increase in during on the ipsilateral side of stimulation was observed in only four of the seven subjects. For these subjects, showed an increase of 6.9 (5.9, 7.8) μmol, while changes were still not significant, i.e., median (IQR) of (, 0.1) μmol (). The remaining three subjects did not show a significant increase in on the ipsilateral side of stimulation (). We explored the possibility that the separation between these two subgroups of subjects (i.e., “responders” and “nonresponders”) was correlated with either RMT or age, but correlations were not found, i.e., and , respectively. The small number of subjects limits our ability to conclusively answer questions about such correlations, which deserve further investigation.

In contrast to the hemodynamic changes observed on the side of the brain ipsilateral to stimulation, the maximum change from baseline during TMS was not statistically significant on the contralateral hemisphere. Across all subjects, the median (IQR) from the baseline in the contralateral side was (, 12) % over the period of administration. On the contralateral side, and Hb median concentration changes were 0.9 (, 1.0) μmol and 0.4 (, 0.9) μmol, respectively, which summed to give a median HbT change of 0.7 (, 1.4) μmol. None of the changes observed in the contralateral side were significantly different from the baseline ().

After cessation of stimulation, changes in the measured parameters decreased in the ipsilateral hemisphere but did not return to baseline. Four minutes poststimulation, hemodynamic changes had decreased approximately 10% from their values immediately after stimulation to a median in the ipsilateral side of 28 (18, 42) % relative to the beginning of stimulation. (Note that 4 min poststimulation was lower than the maximum .) Four minutes after the cessation of , remained higher than the baseline for every subject. Similarly, for the subjects who showed a significant increase in , and decreased over time in the poststimulation period, reaching a median of 5.8 (3.5, 6.8) and (, 0.1) μmol, respectively. poststimulation changes were less than the maximum change observed during , but poststimulation was significantly higher than the baseline measured before administration (). No significant changes were observed in the contralateral hemisphere for any of the measurements during the poststimulation period ( in all cases). Figure 4 shows temporal 1-min averages at regular 4-min intervals during and after administration, in order to illustrate hemodynamic patterns independent of short-period intersubject temporal variability.

Fig. 4.

Temporal trends at every 4-min interval for measured changes in (a) cerebral blood flow (CBF), (b) oxy-hemoglobin concentration (), (c) deoxy-hemoglobin concentration (Hb), and (d) total hemoglobin concentration (HbT) before, during, and after administration. Each data point represents the median measurement across the whole population at each specific interval averaged 1-min epochs. Error bars are the interquartile range.

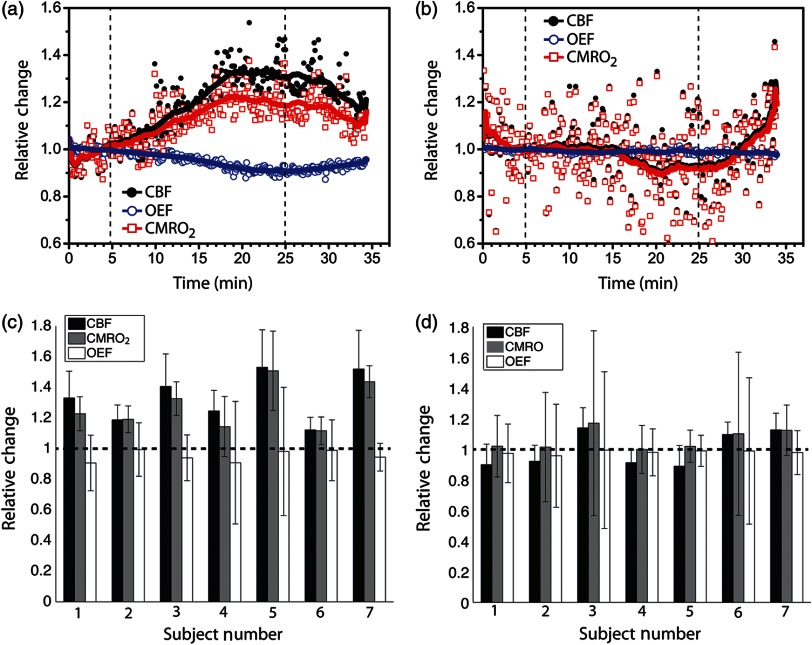

Based on changes in oxygenation and , we also estimated the changes in oxygen consumption due to for each subject. Figure 5 shows an example time-series of for a single illustrative subject for both ipsilateral [Fig. 5(a)] and contralateral [Fig. 5(b)] sites. The magnitude of changes in followed the magnitude of changes in closely for all subjects [Fig. 5(c) and 5(d)], since changes in the OEF were not significant during the whole session. Across the population, the maximum change during administration was significantly different from the baseline in the stimulated hemisphere (), with a median change of 1.3 (1.2, 1.5). On the other hand, the contralateral side of stimulation did not significantly change from the baseline (), with a median change across the population of 1.0 (0.9, 1.1).

Fig. 5.

Relative cerebral blood flow (), oxygen extraction fraction (), and cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen consumption () in (a) ipsilateral and (b) contralateral hemispheres of administration for a single subject during the whole session. The vertical dashed lines indicate the beginning and the end of administration. The thick solid lines are the global trends. At the bottom row, we show the bar plots summarizing the maximum , , and changes for every subject in the (c) ipsilateral and (d) contralateral sides of stimulation.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrated the feasibility and capability of diffuse optical technologies for noninvasive measurement of cerebral hemodynamic changes during administration in healthy subjects. Previously, DOS alone was used to assess hemodynamic changes associated with ,20,21,24,46 and DCS has been demonstrated to measure relative changes in CBF during cortical activation.29 The present work is the first report of the use of DCS for blood perfusion measurements during TMS and the first report of all-optical measurements combining perfusion and tissue oxygenation to understand hemodynamic and metabolic physiological changes during administration. Particularly, although not entirely new, the use of DCS for noninvasive measurement of CBF changes in the human motor cortex is an accomplishment due to the challenges of the small detection area required by the technique. In addition, TMS requirements constrain the measurement geometry, since the magnetic coil must be close to the scalp and the probe. Besides feasibility, the pilot results indicate that the hybrid DCS/DOS instrumentation can glean more insight about brain function during than DOS/NIRS, by providing extra CBF information. As a result, the combined DCS/DOS technique permits experimenters to infer information about relative changes in oxygen consumption and brain metabolism.

In this pilot investigation, a clinically relevant longer term low-frequency administration was employed, consisting of 20 min of stimulation at 1 Hz on the primary motor cortex. Low-frequency has been used as a means of transiently causing focal inhibition of regions of the cerebral cortex, in order to create experimentally useful “virtual lesions.”47,48 Following the observation that low-frequency has focal inhibitory effects on neural activity,49 the long-term approach has been adopted in several investigations that sought to make enduring changes in cortical function in patients suffering from a variety of neurologic conditions, including poststroke motor, language, and visuospatial deficits;50,51 epilepsy;52 and psychiatric disorders.53

Here we report significant increases in tissue hemodynamics at the site of stimulation. By contrast, we did not observe statistically significant changes in hemodynamic properties during or after stimulation in the motor cortex contralateral to the site of stimulation. This kind of pattern is typically associated with cortical activity due to functional activation. We found that 20 min of stimulation at a frequency of 1 Hz produced significant increases in and on the side ipsilateral to stimulation; further, these induced changes persisted after discontinuation of stimulation. Significant changes in ipsilateral and during were seen for only a subgroup of these subjects (four of the seven subjects). This lack of statistically significant oxygenation response in three subjects is less consistent than the observations about blood flow, and its origin is unclear, though it should be noted that these data were quite noisy and a correlation between and across the patient group was evident. Further, the “ responder” subgroup was not clearly separated by age or RMT; ultimately, the small number of subjects limits conclusive response to questions about correlations.

Increases in were previously reported by DOS-only measurements during single-pulse stimulation at low intensities,22 and the increases were attributed to transient activation of the motor cortex above the active baseline by TMS. Blood flow dynamics measured in the present work showed consistent CBF increases on the side of stimulation, which is in overall agreement with previous studies using other medical modalities such as PET.9 A recent MRI study employing continuous arterial spin labeling also reported robust increases in motor and premotor areas due to 24 s of continuous 2 Hz at 100% of the RMT.54 However, a recent study by Thomson et al. found that 10 min of 1 Hz delivered to the motor cortex resulted in a significant decrease in during stimulation.13 While this last result superficially appears to be in conflict with our DOS findings, these investigators also reported a clear difference in the TMS effect based on intensity, with no persistent decrease in observed at 80% RMT. This finding is potentially consistent with evidence suggesting that TMS at different intensities preferentially stimulates different neuronal populations, with lower intensity stimulation selectively stimulating inhibitory interneurons and higher intensities stimulating both inhibitory and excitatory neuronal populations.55 Thus one possible explanation for the discrepancy between our findings and those of Thomson et al. may be that different intensities of elicit very different patterns of hemodynamic response, even at the same stimulation frequency.

The observed increase in ipsilateral CBF and metabolism after “inhibitory” may reflect increased activity of inhibitory interneurons. During motor action, the activity of excitatory neurons in the motor cortex presumably exceeds that of inhibitory interneurons. Therefore, the effect of increasing the activity of inhibitory interneurons with may decrease the overall metabolic consumption of the motor cortex by diminishing the high rate of metabolic consumption of excitatory neurons during action. By this account, increased oxygen consumption and blood flow would be expected after inhibitory at rest, as observed here, but decreased metabolic activity would be expected after inhibitory during a motor task.

Our finding that stimulation was not associated with significant cerebral oxygenation changes in the contralateral motor cortex was somewhat unexpected, since prior neurophysiologic studies have shown that 1 Hz of the motor cortex results in contralateral changes in excitability and function.56–59 It has been proposed that administration of inhibitory to the motor cortex in one hemisphere releases the contralateral motor cortex from interhemispheric inhibition.60 One possibility is that contralateral changes may have been below the detection level of our optical instrument ( in and in oxygenation). Alternatively, while release from interhemispheric inhibition may increase motor cortex excitability, increased cortical activity and resultant increased metabolic activity may only be elicited during TMS-induced motor evoked potentials or voluntary motor actions.59 Thus, release of hemispheric inhibition alone might not affect the basal level of neural activity of the contralateral motor cortex at rest.

The persistent effects of have been described as being similar to the neuroplastic processes of long-term potentiation or long-term depression, and converging evidence suggests that at least some of the long-term effects of are mediated by changes in synaptic efficacy.61–63 Our findings suggest that the mechanisms that underlie persistent effects also involve persistent modifications in the hemodynamic properties of the cortex. The relationship between these hemodynamic perturbations, mechanisms of neuroplasticity, and persistent physiologic or behavioral changes after remains to be examined. Thus the use of diffuse optical measures may provide new insights into the mechanisms of modulation, especially for investigations in which direct measures of motor physiology cannot be employed.50,51,64

Although the -induced neural processes highlighted above provide a plausible explanation for our findings, one must be careful when analyzing intrinsic optical signals from the brain. If possible, noncortical contributions should be accounted for when interpreting the optical signal. As noted earlier, it has been demonstrated that -evoked optical signals can include components that are not a direct result of cerebral activity, i.e., components that arise from systemic physiology stimulated by .25 Since such systemic physiology was not monitored in our subject cohort, it is possible that non-neuronal signal sources might have influenced some of the changes reported in Table 1, and we have no sure method to separate these two classes of effects, which are ultimately due to . Nonetheless, previous studies with DOS and DCS were able to successfully investigate cortical hemodynamics at the same source–detector separations used in this study (i.e., 2.5 cm). Some of these investigations quantitatively examined the penetration of DCS signals into the brain,29,65–67 and other studies validated DCS measurements against direct measurements of CBF by other techniques.31–34 On balance, previous findings suggest that our detected signals predominantly reflect neural response activated by ; however, more research is warranted in order to fully discern neural from systemic responses. The present work represents a step along these lines.

Regarding potentially relevant differences in methodology, our protocol determined the RMTs by visual inspection rather than by using electromyographic activity (EMG).68 Although evidence has shown that visually determined RMTs closely approximate those determined using neurophysiologic measures,37,38 it is possible that visual inspection may be less sensitive for determining RMTs; in this case, the administered may have been at a higher intensity than would have been administered if RMTs had been determined using EMG. While it is possible that higher intensity stimulation could have elicited movement or proprioceptive stimulation that might have affected hemodynamic responses in the motor cortex, careful monitoring of subjects for movement throughout the experimental sessions suggests that this was unlikely. In addition, the TMS coil location was manually held constant throughout data collection. We monitored the coil in real time and readjusted its position over the motor cortex when necessary; nevertheless, it is possible that slight deviations from the optimal position over the motor cortex might have contributed to some of the fluctuations in our data. Most likely, however, these translational fluctuation effects should be smaller than SNR. Another difference in methodology to consider is that some prior studies22–24 employed monophasic pulses of TMS, while the current study was conducted using biphasic stimulation. It remains unknown, for example, whether and how differences in pulse waveform affect cerebral hemodynamic responses. Future studies with DOS and DCS that employ a range of intensities and compare different kinds of pulses will be required to clarify these issues.

Finally, we comment on technical limitations of the measurement scheme. First, because of the small detection area, i.e., due to the use of single-mode fiber detection for DCS, the SNR was relatively low. Generally, the presence of hair and the need for source–detector distances of or more on the surface of the head are factors that limit SNR and that can be improved in the future. For a single detection fiber, a typical SNR for a head measurement on M1 varies from to (corresponding to photon counting rates of 4 to 50 kHz). In this study, we improved measurement SNR by averaging over four single-mode fibers at each detection site; this scheme elevated SNR by a factor of two in most cases. In the future, more fibers could be employed to elevate SNR even more. The high standard deviation in Table 1 is at least in part due to our relatively low SNR.

To summarize, our findings demonstrate the feasibility and utility of using DCS and DOS for noninvasive monitoring during -induced effects in human cortex. This approach was applied to low-frequency long-duration , which is used clinically to produce focal cortical inhibition. Although preliminary, our findings suggest that low-frequency produces a gradual increase in CBF and that persists after stimulation ceases, providing a potential biomarker for the effects of on cortical function.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dalton Hance and Steven S. Schenkel for help with data acquisition. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health through P30 NS045839, K01-NS060995 (R.H.H), R01-NS060653 (A.G.Y), K24-NS058386 (J.A.D), R24-HD050836 (J.A.D), and P41-EB015893 (A.G.Y and J.A.D). Funding was also available from Fundació Cellex Barcelona (TD), São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP 2012/02500-8; R.C.M), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation/Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Program, Neuro-Cognitive Rehabilitation Research Network, the Institute for Translational Medicine and Therapeutics, Clinical & Translational Science Awards, and the Translational Biomedical Imaging Core at the University of Pennsylvania.

References

- 1.Barker A., Jalinous R., Freeston I. L., “Non-invasive magnetic stimulation of human motor cortex,” Lancet 325(8437), 1106–1107 (1985). 10.1016/S0140-6736(85)92413-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsh V., Cowey A., “Transcranial magnetic stimulation and cognitive neuroscience,” Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 1(1), 73–79 (2000). 10.1038/35036239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pascual-Leone A., Walsh V., Rothwell J. C., “Transcranial magnetic stimulation in cognitive neuroscience—virtual lesion, chronometry, and functional connectivity,” Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 10(2), 232–237 (2000). 10.1016/S0959-4388(00)00081-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kobayashi M., Pascual-Leone A., “Transcranial magnetic stimulation in neurology,” Lancet Neurol. 2(3), 145–156 (2003). 10.1016/S1474-4422(03)00321-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aarre T. F., et al. , “Efficacy of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in depression: a review of the evidence,” Nord. J. Psychiatry 57(3), 227–232 (2003). 10.1080/08039480310001409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen R., et al. , “Depression of motor cortex excitability by low-frequency transcranial magnetic stimulation,” Neurology 48(5), 1398–1403 (1997). 10.1212/WNL.48.5.1398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rossi S., et al. , “Effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on movement-related cortical activity in humans,” Cereb. Cortex 10(8), 802–808 (2000). 10.1093/cercor/10.8.802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brandt S. A., et al. , “Functional magnetic resonance imaging shows localized brain activation during serial transcranial stimulation in man,” Neuroreport 7(3), 734–736 (1996). 10.1097/00001756-199602290-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fox P., et al. , “Imaging human intra-cerebral connectivity by PET during TMS,” Neuroreport 8(12), 2787–2791 (1997). 10.1097/00001756-199708180-00027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paus T., et al. , “Dose-dependent reduction of cerebral blood flow during rapid-rate transcranial magnetic stimulation of the human sensorimotor cortex,” J. Neurophysiol. 79(2), 1102–1107 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siebner H. R., et al. , “Lasting cortical activation after repetitive TMS of the motor cortex: a glucose metabolic study,” Neurology 54(4), 956–963 (2000). 10.1212/WNL.54.4.956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siebner H. R., et al. , “Continuous transcranial magnetic stimulation during position emission tomography: a suitable tool for imaging regional excitability of the human cortex,” Neuroimage 14(4), 883–890 (2001). 10.1006/nimg.2001.0889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomson R. H., et al. , “Intensity dependent repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation modulation of blood oxygenation,” J. Affect. Disord. 136(3), 1243–1246 (2012). 10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okabe S., Ugawa Y., Kanazawa I., Effectiveness of on Parkinson’s disease study group, “0.2-Hz repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation has no add-on effects as compared to a realistic sham stimulation in Parkinson’s disease,” Mov. Disord. 18(4), 382–388 (2003). 10.1002/mds.10370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bestmann S., et al. , “Subthreshold high-frequency TMS of human primary motor cortex modulates interconnected frontal motor areas as detected by interleaved fMRI-TMS,” Neuroimage 20(3), 1685–1696 (2003). 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.07.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nahas Z., et al. , “Unilateral left prefrontal transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) produces intensity-dependent bilateral effects as measured by interleaved BOLD fMRI,” Biol. Psychiatry. 50(9), 712–720 (2001). 10.1016/S0006-3223(01)01199-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jobsis F. F., “Noninvasive, infrared monitoring of cerebral and myocardial oxygen sufficiency and circulatory parameters,” Science 198(4323), 1264–1267 (1977). 10.1126/science.929199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Durduran T., et al. , “Diffuse optics for tissue monitoring and tomography,” Rep. Prog. Phys. 73(7), 076701 (2010). 10.1088/0034-4885/73/7/076701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mesquita R. C., Yodh A. G., “Diffuse optics: fundamentals and tissue applications,” in Proc. Int. School of Physics “Enrico Fermi” Course CLXXIII Nano Optics and Atomics: Transport of Light and Matter Waves, Kaiser R., Weirsma D. S., Fallini L., Eds., pp. 51–74, IOS Press, Amsterdam: (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kozel F. A., et al. , “Using simultaneous repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation/functional near infrared spectroscopy () to measure brain activation and connectivity,” Neuroimage 47(4), 1177–1184 (2009). 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tian F., et al. , “Test-retest assessment of cortical activation induced by repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation with brain atlas-guided optical topography,” J. Biomed. Opt. 17(11), 116020 (2012). 10.1117/1.JBO.17.11.116020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noguchi Y., Watanabe E., Sakai K. L., “An event-related optical topography study of cortical activation induced by single-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation,” Neuroimage 19(1), 156–162 (2003). 10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00054-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mochizuki H., et al. , “Cortical hemoglobin-concentration changes under the coil induced by single-pulse TMS in humans: a simultaneous recording with near-infrared spectroscopy,” Exp. Brain Res. 169(3), 302–310 (2006). 10.1007/s00221-005-0149-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oliviero A., et al. , “Cerebral blood flow and metabolic changes produced by repetitive magnetic brain stimulation,” J. Neurol. 246(12), 1164–1168 (1999). 10.1007/s004150050536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Näsi T., et al. , “Magnetic-stimulation-related physiological artifacts in hemodynamic near-infrared spectroscopy signals,” PLoS ONE 6(8), e24002 (2011). 10.1371/journal.pone.0024002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boas D. A., Campbell L. E., Yodh A. G., “Scattering and imaging with diffusing temporal field correlations,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 75(9), 1855–1858 (1995). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.75.1855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mesquita R. C., et al. , “Direct measurement of tissue blood flow and metabolism with diffuse optics,” Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 369(1955), 4358–4379 (2011). 10.1098/rsta.2011.0232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu G., et al. , “Near-infrared diffuse correlation spectroscopy for assessment of tissue blood flow,” in Handbook of Biomedical Optics, Boas D. A., Pitris C., Ramanujam N., Eds., pp. 195–216, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL: (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Durduran T., et al. , “Diffuse optical measurement of blood flow, blood oxygenation and metabolism in human brain during sensorimotor cortex activation,” Opt. Lett. 29(15), 1766–1768 (2004). 10.1364/OL.29.001766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jaillon F., et al. , “Activity of the human visual cortex measured non-invasively by diffusing-wave spectroscopy,” Opt. Express 15(11), 6643–6650 (2007). 10.1364/OE.15.006643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu G., et al. , “Validation of diffuse correlation spectroscopy for muscle blood flow with concurrent arterial spin labeled perfusion MRI,” Opt. Express 15(3), 1064–1075 (2007). 10.1364/OE.15.001064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carp S. A., et al. , “Validation of diffuse correlation spectroscopy measurements of rodent cerebral blood flow with simultaneous arterial spin labeling MRI; towards MRI-optical continuous cerebral metabolic monitoring,” Biomed. Opt. Express 1(2), 553–565 (2010). 10.1364/BOE.1.000553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim M. N., et al. , “Noninvasive measurement of cerebral blood flow and blood oxygenation using near-infrared and diffuse correlation spectroscopies in critically brain-injured adults,” Neurocrit. Care 12(2), 173–180 (2010). 10.1007/s12028-009-9305-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buckley E. M., et al. , “Cerebral hemodynamics in preterm infants during positional intervention measured with diffuse correlation spectroscopy and transcranial Doppler ultrasound,” Opt. Express 17(15), 12571–12581 (2009). 10.1364/OE.17.012571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roche-Labarbe N., et al. , “Noninvasive optical measures of CBV, , CBF index and in human premature neonates’ brains in the first six weeks of life,” Hum. Brain Mapp. 31(3), 341–352 (2010). 10.1002/hbm.v31:3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Diop M., et al. , “Calibration of diffuse correlation spectroscopy with a time-resolved near-infrared technique to yield absolute cerebral blood flow measurements,” Biomed. Opt. Express 2(7), 2068–2081 (2011). 10.1364/BOE.2.002068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pridmore S., et al. , “Motor threshold in transcranial magnetic stimulation: a comparison of a neurophysiological method and a visualization of movement method,” J. ECT 14(1), 25–27 (1998). 10.1097/00124509-199803000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Balslev D., et al. , “Inter-individual variability in optimal current direction for transcranial magnetic stimulation of the motor cortex,” J. Neurosci. Methods 162(1–2), 309–313 (2007). 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duncan A., et al. , “Measurement of cranial optical path length as a function of age using phase resolved near infrared spectroscopy,” Pediatr. Res. 39(5), 889–894 (1996). 10.1203/00006450-199605000-00025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mayhew J., et al. , “Increased oxygen consumption following activation of brain: theoretical footnotes using spectroscopic data from barrel cortex,” Neuroimage 13(6), 975–987 (2001). 10.1006/nimg.2001.0807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Culver J. P., et al. , “Diffuse optical tomography of cerebral blood flow, oxygenation and metabolism in rat during focal ischemia,” J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 23(8), 911–924 (2003). 10.1097/01.WCB.0000076703.71231.BB [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boas D. A., et al. , “Can the cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen be estimated with near-infrared spectroscopy?,” Phys. Med. Biol. 48(15), 2405–2418 (2003). 10.1088/0031-9155/48/15/311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cheung C., et al. , “In vivo cerebrovascular measurement combining diffuse near-infrared absorption and correlation spectroscopies,” Phys. Med. Biol. 46(8), 2053–2065 (2001). 10.1088/0031-9155/46/8/302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hallacoglu B., et al. , “Absolute measurement of cerebral optical coefficients, hemoglobin concentration and oxygen saturation in old and young adults with near-infrared spectroscopy,” J. Biomed. Opt. 17(8), 081406 (2012). 10.1117/1.JBO.17.8.081406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Torricelli A., et al. , “In vivo optical characterization of human tissues from 610 to 1010 nm by time-resolved reflectance spectroscopy,” Phys. Med. Biol. 46(8), 2227–2237 (2001). 10.1088/0031-9155/46/8/313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hanaoka N., et al. , “Deactivation and activation of left frontal lobe during and after low-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation over right prefrontal cortex: a near-infrared spectroscopy study,” Neurosci. Lett. 414(2), 99–104 (2007). 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sandrini M., Umiltà C., Rusconi E., “The use of transcranial magnetic stimulation in cognitive neuroscience: a new synthesis of methodological issues,” Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 35(3), 516–536 (2011). 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Walsh V., Pascual-Leone A., Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation: a Neurochronometrics of Mind, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA: (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maeda F., Pascual-Leone A., “Transcranial magnetic stimulation: studying motor neurophysiology of psychiatric disorders,” Psychopharmac. 168(4), 359–376 (2003). 10.1007/s00213-002-1216-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hamilton R. H., et al. , “Stimulating conversation: enhancement of elicited propositional speech in a patient with chronic non-fluent aphasia following transcranial magnetic stimulation,” Brain Lang. 113(1), 45–50 (2010). 10.1016/j.bandl.2010.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Naeser M. A., et al. , “Improved picture naming in chronic aphasia after TMS to part of right Broca’s area: an open-protocol study,” Brain Lang. 93(1), 95–105 (2005). 10.1016/j.bandl.2004.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fregni F., et al. , “A randomized clinical trial of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in patients with refractory epilepsy,” Ann. Neurol. 60(4), 447–455 (2006). 10.1002/ana.20950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tillman G. D., et al. , “Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and threat memory: selective reduction of combat threat memory P300 response after right frontal-lobe stimulation,” J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 23(1), 40–47 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moisa M., et al. , “Interleaved TMS/CASL: comparison of different protocols,” Neuroimage 49(1), 612–620 (2010). 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pashut T., et al. , “Mechanisms of magnetic stimulation of central nervous system neurons,” PLoS Comput. Biol. 7(3), e1002022 (2011). 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cracco R. Q., et al. , “Comparison of human transcallosal responses evoked by magnetic coil and electrical stimulation,” Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 74(6), 417–424 (1989). 10.1016/0168-5597(89)90030-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ferbert A., et al. , “Interhemispheric inhibition of the human motor cortex,” J. Physiol. 453, 525–546 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kobayashi M., et al. , “Repetitive TMS of the motor cortex improves ipsilateral sequential simple finger movements,” Neurology 62(1), 91–98 (2004). 10.1212/WNL.62.1.91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kobayashi M., “Effect of slow repetitive TMS of the motor cortex on ipsilateral sequential simple finger movements and motor skill learning,” Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 28(4), 437–448 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Perez M. A., Cohen L. G., “Interhemispheric inhibition between primary motor cortices: what have we learned?,” J. Physiol. 587(4), 725–726 (2009). 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.166926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Funke K., Benali A., “Cortical cellular actions of transcranial magnetic stimulation,” Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 28(4), 399–417 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hoogendam J. M., Ramakers G. M., Di Lazzaro V., “Physiology of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the human brain,” Brain Stimul. 3(2), 95–118 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thickbroom G. W., “Transcranial magnetic stimulation and synaptic plasticity: experimental framework and human models,” Exp. Brain Res. 180(4), 583–593 (2007). 10.1007/s00221-007-0991-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kito S., Fujita K., Koga Y., “Regional cerebral blood flow changes after low-frequency transcranial magnetic stimulation of the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in treatment-resistant depression,” Neuropsychobiol. 58(1), 29–36 (2008). 10.1159/000154477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gagnon L., et al. , “Investigation of diffuse correlation spectroscopy in multi-layered media including the human head,” Opt. Express 16(20), 15514–15530 (2008). 10.1364/OE.16.015514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li J., et al. , “Noninvasive detection of functional brain activity with near-infrared diffusing-wave spectroscopy,” J. Biomed. Opt. 10(4), 044002 (2005). 10.1117/1.2007987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lee C. K., et al. , “Study of photon migration with various source-detector separations in near-infrared spectroscopic brain imaging based on three-dimensional Monte Carlo modeling,” Opt. Express 13(21), 8339–8348 (2005). 10.1364/OPEX.13.008339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rossini P. M., et al. , “Non-invasive electrical and magnetic stimulation of the brain, spinal cord and roots: basic principles and procedures for routine clinical application,” Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 91(2), 79–92 (1994). 10.1016/0013-4694(94)90029-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]