Abstract

Ocean acidification is considered a major threat to marine ecosystems and may particularly affect calcifying organisms such as corals, foraminifera and coccolithophores. Here we investigate the impact of elevated pCO2 and lowered pH on growth and calcification in the common calcareous dinoflagellate Thoracosphaera heimii. We observe a substantial reduction in growth rate, calcification and cyst stability of T. heimii under elevated pCO2. Furthermore, transcriptomic analyses reveal CO2 sensitive regulation of many genes, particularly those being associated to inorganic carbon acquisition and calcification. Stable carbon isotope fractionation for organic carbon production increased with increasing pCO2 whereas it decreased for calcification, which suggests interdependence between both processes. We also found a strong effect of pCO2 on the stable oxygen isotopic composition of calcite, in line with earlier observations concerning another T. heimii strain. The observed changes in stable oxygen and carbon isotope composition of T. heimii cysts may provide an ideal tool for reconstructing past seawater carbonate chemistry, and ultimately past pCO2. Although the function of calcification in T. heimii remains unresolved, this trait likely plays an important role in the ecological and evolutionary success of this species. Acting on calcification as well as growth, ocean acidification may therefore impose a great threat for T. heimii.

Introduction

The oceans have taken up about one third of all CO2 emitted by anthropogenic activities since the onset of the industrial revolution [1]–[3]. This directly impacts seawater carbonate chemistry by increasing concentrations of CO2 and bicarbonate (HCO3 −), decreasing concentrations of carbonate (CO3 2−) and a lowering of pH [4]. The acidification of ocean waters might impact marine life, notably calcifying organisms that use inorganic carbon to produce a calcium carbonate (CaCO3) shell. Calcifying organisms play an important ecological and biogeochemical role in marine ecosystems, evident from extensive coral reefs and vast calcite deposits found in geological records. Ocean acidification has been shown to reduce calcification of various key calcifying organisms such as corals [5], foraminifera [6], and coccolithophores [7], [8]. Little is yet known about the general responses of calcareous dinoflagellates [9], and no study so far investigated the impact of ocean acidification on their calcification.

Dinoflagellates feature a complex life-cycle that often includes formation of cysts. In some species, these cysts are made of calcite and can contribute substantially to the ocean carbonate flux in certain regions [10]–[12]. Thoracosphaera heimii, the most common calcareous dinoflagellate species in present-day ocean, is autotrophic and occurs typically in subtropical and tropical waters [13]–[15]. The main life-cycle stage of T. heimii comprises coccoid vegetative cells with a calcium carbonate shell, so-called vegetative cysts [16], [17]. Although the term cyst is most often used for long-term resting stages that are typically produced after sexual reproduction, in T. heimii this term is used for its coccoid vegetative stage. Cysts of T. heimii can be commonly found in the fossil record in sediments dating back to the Cretaceous [18]. Therefore, T. heimii cysts may serve as potential proxy for reconstructing the past climate. For instance, Sr/Ca ratios have been shown to correlate well with sea surface temperatures [19], but also the oxygen and carbon isotopes trapped in the cysts could provide useful proxies.

The oxygen isotopic composition (δ18O) of calcite was found to be strongly controlled by the temperature and the δ18O of the seawater in which the organism calcifies [20]–[22]. In abiotic precipitation experiments, the δ18O of calcite is mainly a function of the δ18O and speciation of dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC), where dissolved CO2 is heavier with respect to 18O than HCO3 − and CO3 2− [23], [24]. Similarly, the carbon isotopic composition (δ13C) of calcite is predominantly controlled by the δ13C and speciation of DIC, yet dissolved CO2 is depleted with respect to 13C relative to HCO3 − and CO3 2− [21], [25]. In unicellular calcifiers like coccolithophores and T. heimii, calcification occurs intracellularly in specialized vesicles [16], [26], [27]. Therefore, the inorganic carbon used for calcification by these organisms must be derived from the intracellular inorganic carbon (Ci) pool. Consequently, changes in δ18O and δ13C of calcite should resemble changes in the intracellular Ci pool and may provide insights in the physiological processes underlying calcification and organic carbon production.

Comparable to coccolithophores, ocean acidification likely reduces calcification in T. heimii as well. Furthermore, increasing concentrations of CO2 are expected to alter the stable carbon and oxygen isotopic composition of T. heimii cysts. To test these hypotheses, we grew T. heimii at a range of CO2 levels and followed its responses in growth and calcification. Besides the assessment of δ18O and δ13C in T. heimii as a proxy, we use its isotopic composition as a tool to understand processes involved in organic carbon production and calcification. Transcriptomic analyses were applied to reveal mechanisms underlying the observed responses.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Set-up

Cells of Thoracosphaera heimii RCC1512 (formerly AC214; Roscoff Culture Collection) were grown as dilute batch cultures in 2.4 L air-tight borosilicate bottles. Population densities were kept low at all times (<1,300 cells mL−1) in order to keep changes in carbonate chemistry minimal (i.e. <3.5% with respect to DIC; Table S1). Filtered natural seawater (0.2 µm) was enriched with metals and vitamins according to the recipe for f/2-medium, except for FeCl3 (1.9 µmol L−1), H2SeO3 (10 nmol L−1), and NiCl2 (6.3 nmol L−1). The added concentrations of NO3 − and PO4 3− were 100 µmol L−1 and 6.25 µmol L−1, respectively. Cultures were grown at a light:dark cycle of 16∶8 h and an incident light intensity of 250±25 µmol photons m−2 s−1 provided by daylight lamps (Lumilux HO 54W/965, Osram, München, Germany). Bottles were kept at 15°C and placed on a roller table to avoid sedimentation. Prior to inoculation, the culture medium was equilibrated with air containing 150 µatm CO2 (∼Last Glacial Maximum), 380 µatm CO2 (∼present-day), 750 and 1400 µatm CO2 (future scenarios assuming unabated emissions). Each treatment was performed in triplicate.

Sampling and Analyses

Prior to the experiments, cells were acclimated to the respective CO2 concentrations for at least 21 days, which corresponds to >7 cell divisions. Experiments were run for 8 days and included >3 cell divisions. Cell growth was monitored by means of triplicate cell counts daily or every other day with an inverted light microscope (Axiovert 40C, Zeiss, Germany), using 0.5–2 ml culture suspension fixed with Lugol’s solution (2% final concentration in mQ). Cell counts included determination of vegetative cysts, i.e. shells containing cell material, and empty shells. Because empty shells also contain inorganic carbon, the total number of cysts was used for estimating inorganic carbon quota, while only vegetative cysts were included in the growth rate estimations. From each biological replicate, growth rates were estimated by means of an exponential function fitted through the number of vegetative cysts over time, according to:

| (1) |

where Nt refers to the population density at time t (in days), N0 to the population density at the start of the experiment, and µ to the growth rate (Fig. S1).

For total alkalinity (TA) analyses, 25 mL of culture suspension was filtered over glass-fibre filters (GF/F, ∼0.6 µm pore size, Whatman, Maidstone, UK) and stored in gas-tight borosilicate bottles at 3°C. Duplicate samples were analysed by means of potentiometric titrations using an automated TitroLine burette system (SI Analytics, Mainz, Germany). pH was measured immediately after sampling with a pH electrode (Schott Instruments, Mainz, Germany), applying a two-point calibration on the NBS scale prior to each measurement. For DIC analyses, 4 mL culture suspension was filtered over 0.2 µm cellulose-acetate filters, and stored in headspace free gas-tight borosilicate bottles at 3°C. Duplicate samples of DIC were analysed colorimetrically with a QuAAtro autoanalyser (Seal Analytical, Mequon, USA). Carbonate chemistry (Table S1) was assessed by total alkalinity (TA) in combination with pHNBS, temperature and salinity, using the program CO2sys [28]. For the calculations, an average phosphate concentration of 6.4 µmol L−1 was assumed, the dissociation constant of carbonic acid was based on Mehrbach et al. [29], refit by Dickson and Millero [30]. The dissociation constant of sulfuric acid was based on Dickson [31].

To determine the isotopic composition of DIC (δ13CDIC) and the water (δ18Owater), 4 mL of culture suspension was sterile-filtered over 0.2 µm cellulose-acetate filters and stored at 3°C. Prior to analyses, 0.7 mL of sample was transferred to 8 mL vials. For determination of δ13CDIC, the headspace was filled with helium and the sample was acidified with three drops of a 102% H3PO4 solution. For determination of δ18Owater, the headspace was flushed with helium containing 2% CO2. CO2 and O2 isotopic composition in the headspace were measured after equilibration using a GasBench-II coupled to a Thermo Delta-V advantage isotope ratio mass spectrometer with a precision of <0.1‰ [32].

At the end of each experiment, cultures were harvested for analyses of particulate organic carbon (POC) and related isotopic composition (δ13CPOC), total particulate carbon (TPC), isotopic composition of the calcite (δ13Ccalcite and δ18Ocalcite), and for the Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM). For POC and TPC analyses, 250–500 mL cell suspension was filtered over precombusted GF/F filters (12 h, 500°C) and stored at −25°C in precombusted Petri dishes. Prior to POC measurements, 200 µL of 0.2 N analytical grade HCl was added to the filters to remove all particulate inorganic carbon (PIC), and filters were dried overnight. POC, δ13CPOC, and TPC were analysed in duplicate on an Automated Nitrogen Carbon Analyser mass spectrometer (ANCA-SL 20–20, SerCon Ltd., Crewe, UK). PIC was calculated as the difference in carbon content between TPC and POC. δ13Ccalcite and δ18Ocalcite were measured with a Thermo Scientific MAT253 coupled to a Kiel IV carbonate preparation device. Analytical stability and calibration was checked routinely by analyzing NBS19 and IAEA-CO1 carbonate standards. Reproducibility (Kiel IV and MAT253) was <0.05‰ and <0.03‰ for δ18O and δ13C, respectively.

For SEM analyses, 50 mL culture suspension was filtered over a 0.8 µm polycarbonate filter and dried overnight at 60°C. Filters were fixed on aluminium stubs, sputter-coated with gold-palladium using an Emscope SC500 Sputter Coater (Quorum Technologies, Ashford, UK), and viewed under a FEI Quanta FEG 200 scanning electron microscope (FEI, Eindhoven, the Netherlands). From each replicate, a total of >200 cysts were counted and assessed as complete or incomplete.

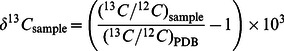

Isotopic Fractionation

Isotopic fractionation during organic carbon production and calcification was calculated based on the carbon isotopic composition of the cellular organic carbon, cellular inorganic carbon and DIC, and the oxygen isotopic composition of the calcite and seawater, respectively. The carbon isotopic composition is reported relative to the PeeDee belemnite standard (PDB):

|

(2) |

The isotopic composition of CO2 (δ13CCO2) was calculated from δ13CDIC using a mass balance relation according to Zeebe and Wolf-Gladrow [24], applying fractionation factors between CO2 and HCO3 − from Mook et al. [33] and between HCO3 − and CO3 2− from Zhang et al. [34]. The isotopic fractionation during POC formation (εp) was calculated relative to δ13CCO2 according to Freeman and Hayes [35]:

| (3) |

The carbon isotopic fractionation during calcite formation (εk) was calculated relative to δ13CDIC:

| (4) |

The oxygen isotopic composition in the calcite is also reported relative to the PDB standard:

| (5) |

The oxygen isotopic composition in DIC (δ18ODIC) was determined using the oxygen fractionation factor between DIC, calculated after Zeebe and Wolf-Gladrow [24], and water (α(DIC-H2O)), calculated after Zeebe [36], with temperature corrected fractionation factors from Beck et al. [37]. The isotopic composition of DIC (δ18ODIC) was calculated according to:

|

(6) |

Transcriptomic Analyses

For RNA extraction, 500 mL of culture suspension was concentrated to 50 mL with a 10 µm mesh-sized sieve, and subsequently centrifuged at 15°C for 15 min at 4000 g. Cell pellets were immediately mixed with 1 mL 60°C TriReagent (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany), frozen with liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Subsequently, cell suspensions were transferred to a 2 mL cryovial containing acid washed glass beads. Cells were lysed using a BIO101 FastPrep instrument (Thermo Savant, Illkirch, France) at maximum speed (6.5 m s−1) for 2×30 s, with an additional incubation of 5 min at 60°C in between. For RNA isolation, 200 µL chloroform was added to each vial, vortexed for 20 s and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. The samples were subsequently centrifuged for 15 min at 4°C with 12,000 g. The upper aqueous phase was transferred to a new vial and 2 µL 5 M linear acrylamide, 10% volume fraction of 3 M sodium acetate, and an equal volume of 100% isopropanol were added. Mixtures were vortexed and subsequently incubated overnight at −20°C in order to precipitate the RNA. The RNA pellet was collected by 20 min centrifugation at 4°C and 12,000 g. The pellet was washed twice, first with 70% ethanol and afterwards with 96% ethanol, air-dried and dissolved with 100 µl RNase free water (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The RNA sample was further cleaned with the RNeasy Kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s protocol for RNA clean-up including on-column DNA digestion. RNA quality check was performed using a NanoDrop ND-100 spectrometer (PeqLab, Erlangen, Germany) for purity, and the RNA Nano Chip Assay with a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Böblingen, Germany) was performed in order to examine the integrity of the extracted RNA. Only high quality RNAs (OD260/OD280>2 and OD260/OD230>1.8) as well as RNA with intact ribosomal peaks (obtained from the Bioanalyzer readings) were used for microarrays.

454-libraries were constructed by Vertis Biotechnologie AG (http://www.vertis-biotech.com/). From the total RNA samples poly(A)+ RNA was isolated, which was used for cDNA synthesis. First strand cDNA synthesis was primed with an N6 randomized primer. Then 454 adapters were ligated to the 5′ and 3′ ends of the cDNA, and the cDNA was amplified with 19 PCR cycles using a proof reading polymerase. cDNA with a size range of 500–800 bp was cut out and eluted from an agarose gel. The generated libraries were quantified with an RL-Standard using the QuantiFluor (Promega, Mannheim, Germany). The library qualities were assessed using the High Sensitivity DNA chip on the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Waldbronn, Germany). For all sequencing runs 20×107 molecules were used for the emulsion PCR that were carried out on a MasterCycler PCR cycler (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). The following enrichment was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing was performed with the GS Junior Titanium Sequencing Kit under standard conditions. The 454 Sequencing System Software version 2.7 was used with default parameters, i.e., Signal Intensity filter calculation, Primer filter, Valley filter, and Base-call Quality Score filter were all enabled.

Statistical Analysis

Normality was confirmed using the Shapiro-Wilk. Variables were log-transformed if this improved the homogeneity of variances, as tested by Levene’s test. Significance of relationships between variables and concentration of CO2 and CO3 2− were tested by means of linear regression. Significance treatments was tested using one-way ANOVA, followed by post hoc comparison of the means using Tukey’s HSD (α = 0.05) [38].

Results

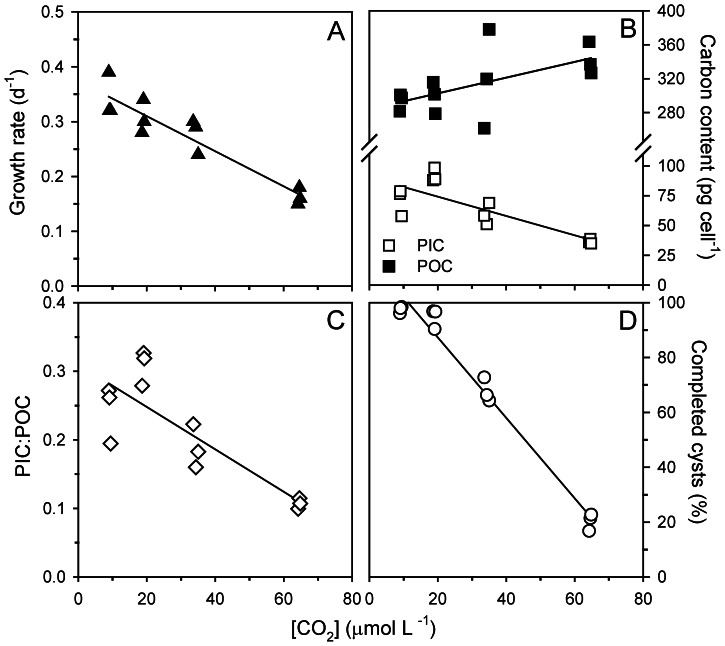

Increasing concentrations of CO2 cause a strong decline in growth (Fig. 1A), which decreases by up to 53% over the investigated CO2 range (Table S2). Although the total carbon quota (TPC) is not affected by CO2 (Table S2), the organic carbon quota (POC) gradually increases while the inorganic carbon quota (PIC) shows a substantial decrease (Fig. 1B). Consequently, the PIC:POC ratio strongly decreases with increasing concentrations of CO2 (Fig. 1C), showing a decrease of ∼54% from the lowest to the highest CO2 treatment (Table S2).

Figure 1. Effect of increasing CO2 concentrations on growth and calcification.

(A) Specific growth rate, (B) PIC and POC, (C) PIC:POC ratio, and (D) fraction of completed cysts. Solid lines indicate linear regressions (n = 12) with (A) R2 = 0.94, P<0.001, (B) POC: R2 = 0.35, P = 0.042, and PIC: R2 = 0.66, P = 0.001, (C) R2 = 0.70, P<0.001, and (D) R2 = 0.98, P<0.001.

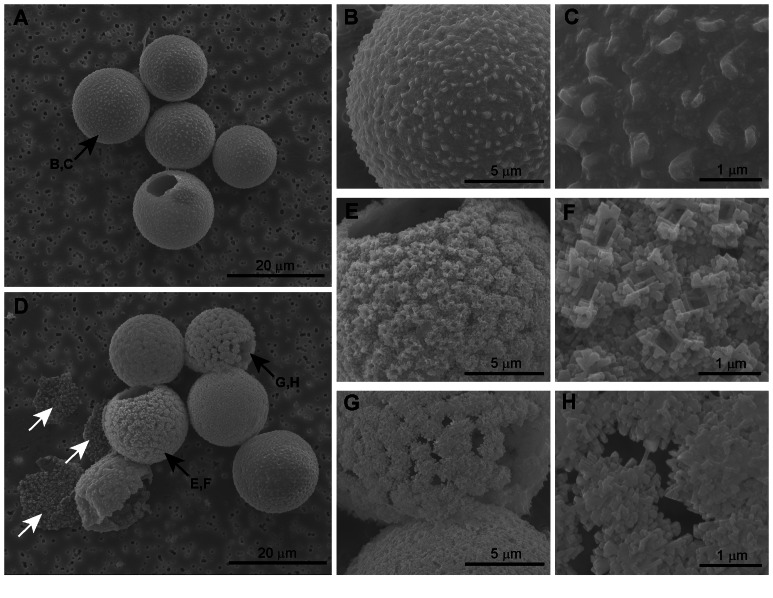

The reduced degree of calcification is also evident from the cyst morphology. In the lowest CO2 treatment, the majority of cysts shows a fully closed and completed calcite structure (Fig. 2A–C). At the highest CO2 concentration, however, calcification of most cysts is incomplete (Fig. 2D–H). Some cysts show initial stages of calcification, indicated by typical square pores (Fig. 2E,F) [16]. In other cysts, the numerous crystallization sites remain unconnected showing clear cavities in the calcite structure (Fig. 2G,H). These cavities likely cause the collapse of many cysts upon filtration (Fig. 2D, white arrows). With increasing concentrations of CO2, the number of completed cysts dramatically decreases from ∼98% at the lowest CO2 treatment towards ∼18% at the highest CO2 treatment (Fig. 1D).

Figure 2. Effect of elevated pCO2 on cyst morphology.

Cells grown under (A–C) 150 µatm CO2 and (D–H) 1400 µatm CO2. Black arrows indicate cysts that are shown in detailed images, white arrows show collapsed cysts.

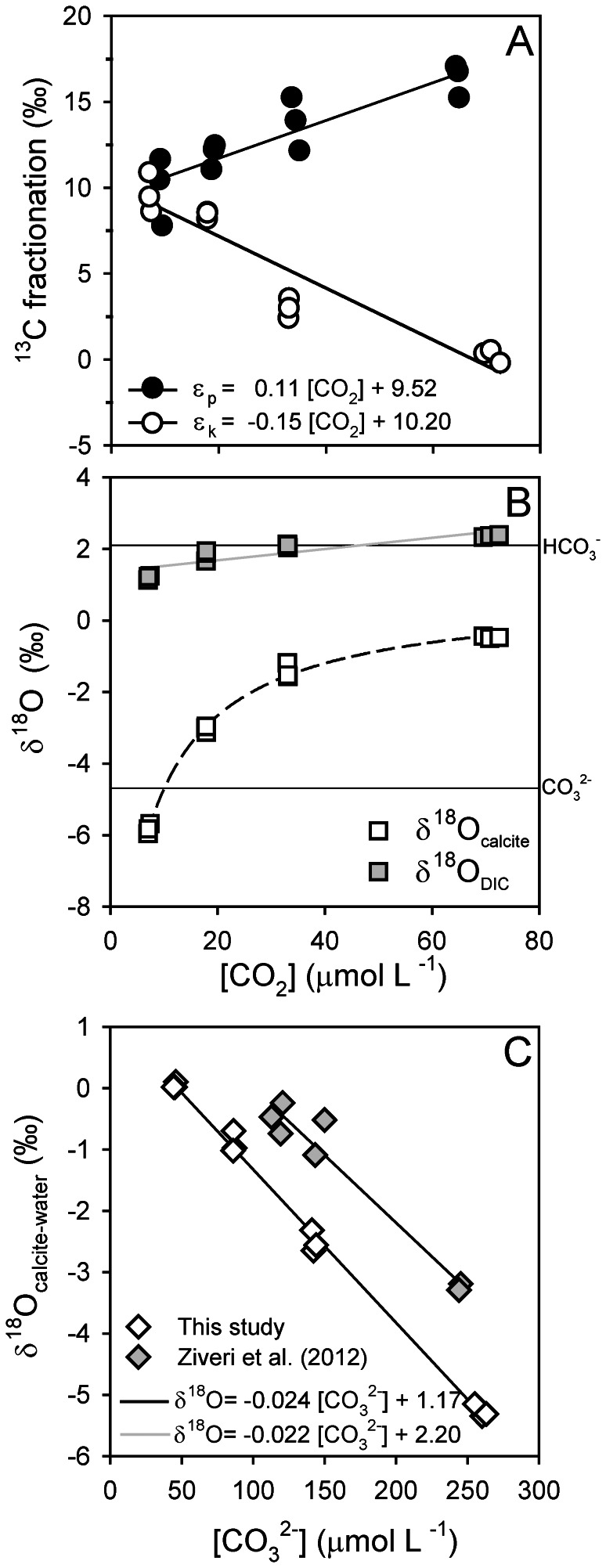

Carbon isotope fractionation responds strongly to the applied CO2 treatments, showing an increase in εp and a decrease in εk with increasing pCO2 (Fig. 3A). In other words, the organic carbon fraction of the cells becomes depleted in 13C while the inorganic carbon fraction (i.e. the calcite) increases its 13C content. Furthermore, the calcite also becomes 18O-enriched, indicated by the increase in δ18Ocalcite with increasing pCO2 (Fig. 3B). As dissolved CO2 is heavier than HCO3 − and CO3 2− [24], increasing CO2 levels cause δ18ODIC to increase (Fig. 3B). Yet, changes are relatively small and the δ18ODIC remains close to that of HCO3 −, which is the dominant inorganic carbon species. To permit comparison with previous findings, δ18Ocalcite values were corrected for the δ18O of water (−0.52±0.07 ‰) and plotted as a function of CO3 2− concentration (Fig. 3C). Calcite δ18O decreases strongly with increasing concentrations of CO3 2−, and the slope is similar to the one reported for another T. heimii strain (RCC1511) [9].

Figure 3. Effect of increasing CO2 concentrations on the stable isotope composition.

(A) 13C fractionation of organic carbon (εp) and calcite (εk), (B) 18O composition of calcite (δ18Ocalcite) and DIC (δ18ODIC), and (C) relationship between the oxygen isotopic composition of calcite (δ18Ocalcite-water) in Thoracosphaera from this study (open diamonds) and from Ziveri et al. [9] (grey diamonds). Horizontal lines in (B) indicate δ18O values for HCO3 − and CO3 2−, and dashed line indicates trend of curve. Solid lines indicate linear regressions (n = 12) with (A) εp: R2 = 0.75, P<0.001, and εk: R2 = 0.90, P<0.001, (B) δ18ODIC: R2 = 0.76, P<0.001, and (C) This study: R2 = 0.99, P<0.001, and Ziveri et al. (2012), (n = 7): R2 = 0.95, P<0.001.

The transcriptome indicates substantial gene regulation in response to changes in carbonate chemistry, with a total of 9701 genes being expressed (Fig. S2). The expression of the majority of genes was treatment specific, amounting to 3183, 2704, and 2176 genes in the low, present-day and high CO2 treatments, respectively (Fig. S2). Interestingly, the number of expressed genes to which a function could be assigned by comparison with public databases was highest in the low and present-day CO2 treatment (∼22%), and lowest in the high CO2 treatment (∼13%). The expressed genes from each treatment are differentially distributed over different ‘eukaryotic orthologous groups’ (KOGs; Fig. S3 and Table S3). Although the total number of expressed genes is largely comparable between treatments, different sets of genes within the KOGs are expressed. About 55% of the number of expressed and annotated genes in each treatment are associated to the KOGs ‘Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis’, ‘Signal transduction mechanisms’, ‘Posttranslational modification, protein turnover and chaperons’, and ‘Energy production and conversion’ (Fig. S3). Expression of genes associated to the latter two categories increased in response to increasing pCO2. In contrast, expression of genes involved in ‘Inorganic ion transport and metabolism’ decreased in the high CO2 treatment (Fig. S3).

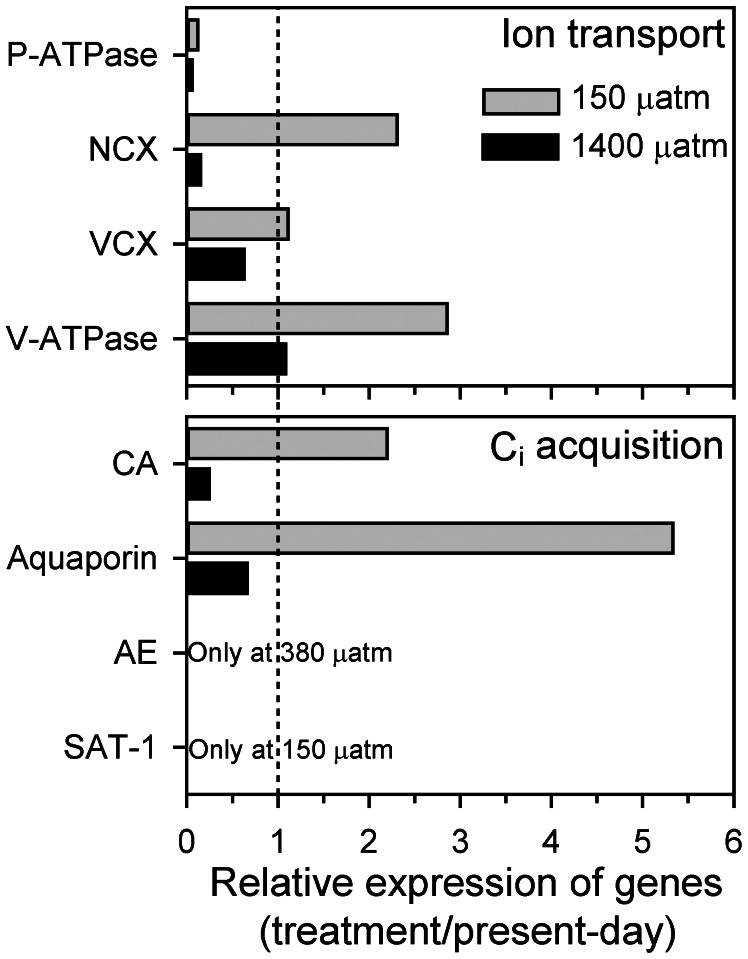

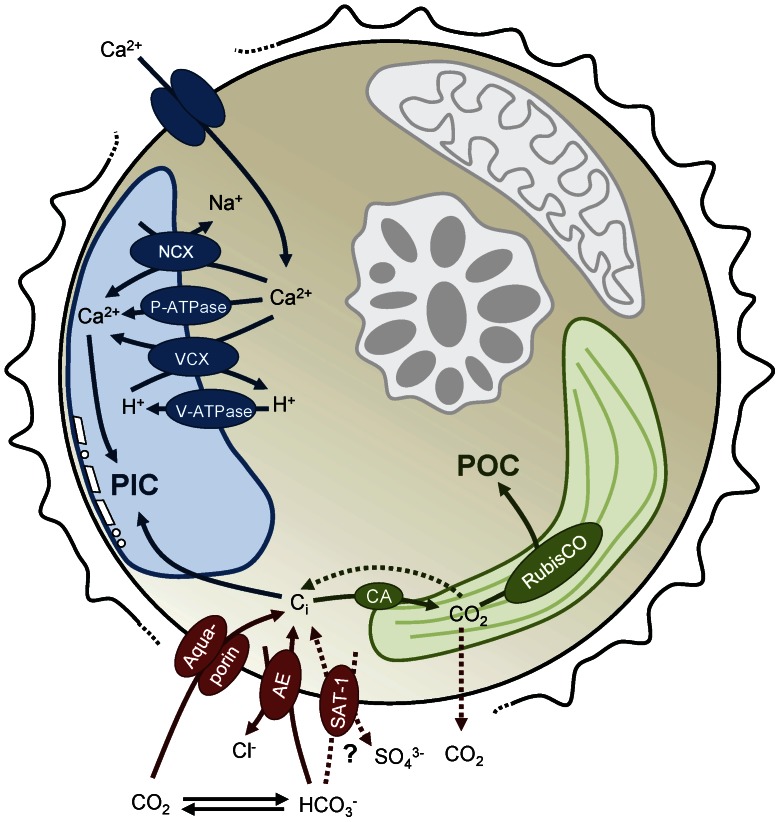

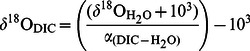

We therefore investigated the genes involved in ion transport and inorganic carbon acquisition in more detail (Fig. 4; Table S4). We observed a substantial regulation of genes associated to vacuolar Ca2+ and H+ transport, including P-type Ca2+ ATPases, Ca2+/Na+ exchangers (NCX1), Ca2+/H+ antiporters (VCX), and vacuolar H+ ATPases (V-ATPase). In particular, the relative expression of genes associated to NCX and V-ATPase decreases from the low to the high CO2 treatment (Fig. 4). Similarly, the relative expression of genes associated to carbonic anhydrases (CA) and aquaporins decreases with increasing pCO2. In the present-day CO2 treatment, we observed expression of a gene associated to an SLC4 family anion exchanger (AE), most likely responsible for the transport of HCO3 − into the cell (Fig. 4) [39]. This gene was expressed in neither the low nor the high CO2 treatment. An SLC26 family SO4 3−/HCO3 −/C2O4 2− anion exchanger (SAT-1) was yet another exclusive expression of a gene only found in the low CO2 treatment. The potential role of this anion exchanger in Ci acquisition by phytoplankton remains to be elucidated.

Figure 4. Effect of elevated pCO2 on gene regulation.

Number of readings found for genes associated to ion transport and Ci acquisition in the 150 µatm and 1400 µatm CO2 treatments relative to the present-day (380 µatm) CO2 treatment.

Discussion

Growth and Carbon Production

Our results show considerable impacts of elevated pCO2 on T. heimii, with strong decreases in its growth rate and degree of calcification (Fig. 1, 2). Despite the increase in organic carbon quota (POC), the overall biomass production decreases substantially with increasing pCO2 (Table S2). Higher availability of CO2 has been shown to promote phytoplankton growth and carbon production [40], [41]. Such CO2 responses are typically associated to the poor catalytic properties of RubisCO, which is characterized by low affinities for its substrate CO2. Increasing concentrations of CO2 are however accompanied by a reduction in pH, which may have consequences for calcification. For the most common coccolithophore Emiliania huxleyi, lowered pH in fact hampers calcification while elevated pCO2 stimulates biomass production, causing a reallocation of carbon and energy between these key processes [42], [43]. This flexibility may explain why growth in E. huxleyi is typically not affected by ocean acidification [44]. In T. heimii, however, we observed a strong decrease in calcification, in biomass production as well as in growth. Apparently, T. heimii lacks the ability to efficiently reallocate cellular carbon between pathways and maintain growth relatively unaffected. Our data furthermore suggests that calcification plays a fundamental role in its growth, life cycle and hence survival. Recent findings have shown that growth and calcification by E. huxleyi may, at least partly, recover from ocean acidification as result of evolutionary adaptation [45]. Whether or not T. heimii exhibits such capabilities of adaptive evolution can only be answered from long-term incubations over hundreds of generations [46].

Transcriptomic analyses reveal a substantial regulation of genes in response to elevated pCO2. Even though no major shift in the relative distribution of expressed genes to the functional categories (KOGs) is induced by the treatments, T. heimii uses different sets of genes within these categories. There is a slight increase in the expression of genes associated to signal transduction and posttranslational modifications upon elevated pCO2, and a decrease in the expression of genes involved in inorganic ion transport (Fig. S3), suggesting that T. heimii readjusts its transcriptome on several levels when grown under different pCO2. Many phytoplankton species have the ability to deal with changes in CO2 availability by regulating their so-called carbon concentrating mechanism (CCMs) [47]–[49]. T. heimii also appears to regulate its proteome towards changes by down-regulating genes involved in CA and aquaporins under elevated pCO2, and by up-regulating these genes under lowered pCO2 (Fig. 4). CA accelerates the equilibrium between CO2 and HCO3 −, and can be located both intra- and extracellularly. From our results it remains unclear whether T. heimii expresses intra- or extracellular CA. Yet, in both cases CA plays a key role in the CCM, as it replenishes the CO2 around RubisCO (intracellular) or the carbon source being depleted in the boundary layer due to active uptake (extracellular) [49], [50]. Aquaporins have been suggested to play a role in CO2 transport [47], [51], which is supported by the observed CO2-dependency in our expression patterns. Besides CO2 also HCO3 − is often transported into the cell, which will facilitate the high intra-cellular CO2 requirements imposed by RubisCO. Indeed, T. heimii expresses genes associated to putative HCO3 − transporters at both low and present-day pCO2, but not at high pCO2 (Fig. 4). Our results thus suggest a down-scaling of the CCM in T. heimii under elevated pCO2, which possibly makes energy available for other processes as it has been observed in other species [43], [52]. Yet it seems that neither the down-scaling of the CCM nor an extensive regulation of the transcriptome can compensate for the adverse effects of elevated pCO2 on growth and calcification in T. heimii.

Calcification and Isotope Fractionation

Calcification in T. heimii was strongly affected by elevated pCO2. Along with a reduction in the degree of calcification (Fig. 1B,C), also the morphology of T. heimii cysts was influenced (Fig. 2). With elevated pCO2 the number of completed cysts dramatically decreased and the number of collapsed cysts increased. The completed calcite structures predominant at low and present-day pCO2 resemble those of mature T. heimii cells, whereas the incomplete calcite structures, prevailing under high pCO2, resemble those of young cells [16], [26]. The incomplete cysts in our experiments, however, often contain an opening through which the cell has left for division, being indicative for mature cells. Thus, cells remained either in the cyst too short for completing the calcite structure, the calcite cyst was directly affected by the low pH of the water, and/or cells reduced their calcification rates. Since growth rates were strongly reduced upon elevated pCO2, it seems unlikely that cells remained in the cyst stage too short for completion of the cyst, as could be expected under enhanced growth rates. Although pH in our highest CO2 treatment was close to 7.6, the water still remained supersaturated with respect to calcite (i.e. an Ωcalcite >1.2; Table S2), and calcite dissolution seem unlikely to have caused the incompletion and cavities in the calcite structure (Fig. 2). Thus, the large number of affected T. heimii cysts at elevated pCO2 seems mainly to be a result of reduced calcification rates by the cells.

Calcification in T. heimii likely takes place intracellularly in vesicles [16], [26], comparable to coccolithophores [9], [27]. Hence, the inorganic carbon needed for calcification is obtained from the intracellular inorganic carbon pool (Ci), which may deviate strongly from external conditions in terms of speciation as well as isotopic composition. We observed an increase of carbon isotope fractionation for organic carbon production (εp), whereas it decreased for calcite formation (εk) in response to elevated pCO2 (Fig. 3A). With a higher availability of CO2, more of the intracellular Ci pool may be replenished by CO2, which is depleted in 13C compared to HCO3 −. Consequently, RubisCO can fractionate against an isotopically lighter Ci pool and thus better express its preference for lighter 12C, which could explain the increasing εp. As a consequence, the intracellular Ci pool becomes enriched with 13C by so-called Rayleigh distillation, which a priori could explain the decrease in εk. However, increased CO2 availability in combination with a reduced organic carbon production should lead to a lowered Rayleigh distillation, and in fact decrease the enrichment of 13C within the cell. Also, Rayleigh distillation should always feedback on CO2 fixation as well as CaCO3 precipitation, and thus cannot explain the opposing trends of fractionation in those processes.

The opposing CO2 effects on εp and εk can thus only be explained if both processes use Ci pools that are isotopically different. CO2 fixation uses the Ci pool within the chloroplast, which is affected by the relative CO2 and HCO3 − fluxes, the CO2 leakage as well as the intrinsic fractionation by RubisCO [53], [54]. The Ci pool for calcification will mainly be controlled by the condition in the cytosol, which in turn is largely affected by the processes in the chloroplast. Discrimination of 13C during fixation will lead to 13CO2 efflux from the chloroplast, causing the cytosolic Ci pool to be enriched with 13CO2. If this 13CO2 is prevented from fast conversion to HCO3 − due to a lack of cytosolic CA activity, it could enter the calcifying vesicle by diffusion and be ‘trapped’ by the high pH resulting from proton pumping (Fig. 5). In fact, we do observe a higher εp (i.e. more 13CO2 can accumulate) and lower overall CA activities under elevated pCO2 (i.e. 13CO2 is not rapidly converted to HCO3 −), which could have attributed to the opposing trends of 13C fractionation during organic and inorganic carbon production. To fully understand the intriguing interplay between these processes and their 13C fractionation, detailed measurements on the modes of Ci acquisition in T. heimii are needed.

Figure 5. Conceptual model of regulated proteins in a T. heimii cell.

The regulated proteins involved in ion transport and Ci acquisition are shown on their putative locations [39], [49], [57] . Proteins involved in vacuolar Ca2+ and H+ transport include P-type Ca2+ ATPases (P-ATPase), Ca2+/Na+ exchangers (NCX), Ca2+/H+ antiporters (VCX), and vacuolar H+ ATPases (V-ATPase). Active uptake of HCO3 − may occur via a SLC4 family anion exchanger (AE) or an SLC26 family SO4 3−/HCO3 −/C2O4 2− anion exchanger (SAT-1). Carbonic anhydrases (CA) are located intracellularly or extracellularly and enhance the interconversion between CO2 and HCO3 −.

The oxygen isotopic composition (δ18O) of calcite was also strongly affected in T. heimii, and increased by almost 6 ‰ over the investigated CO2 range (Fig. 3B). Even though biologically mediated, precipitation of calcite is an abiogenic process, which does not directly involve enzymatic reactions and thus mainly depends on the carbonate chemistry at the calcification site. Assuming negligible fractionation during the transport into the calcification vesicle, δ18Ocalcite should therefore predominantly reflect the δ18O of the Ci species used for calcification. Ci species differ strongly in their δ18O values, ranging from lower values for CO3 2− (−4.7 ‰) and HCO3 − (2.1 ‰) to much higher values for CO2 (11.2 ‰) [24]. A previous study proposed a conceptual model to explain the δ18O dependence of T. heimii calcite and other unicellular planktonic calcifiers on seawater CO3 2− concentration (Fig. 3C) [9]. The authors attribute the negative slope between δ18O and [CO3 2−] to an increased contribution of HCO3 − to the calcification vesicle. Also in our data, δ18Ocalcite increases with increasing pCO2, starting from values close to the δ18O of CO3 2− towards those of HCO3 − (Fig. 3B). As argued above, however, the Ci pool in the calcifying vesicle may also be increasingly influenced by CO2, which is in line with the observed trends in δ18Ocalcite. Such a shift in Ci speciation may be an indication for a lowered intracellular pH, which in fact could be the reason for the hampered calcification under elevated pCO2 [55], [56].

Multiple genes associated to calcification have been described for E. huxleyi and include genes associated to the regulation of inorganic ions [39], [55]–[59]. Here we show that the expression of genes in T. heimii being involved in inorganic ion transport, in particular Ca2+ transport, decreased upon elevated pCO2 (Fig. 4; Fig. S3). This decrease in ion transport is in line with the observed decrease in calcification, which is comparable to observations in E. huxleyi [39], [59]. We also observed a strong CO2 dependent regulation of the vacuolar H+-ATPases (V-ATPase). These pumps play a key role in generating H+ gradients and membrane voltage, which drive multiple transport processes [57], [60]. As indicated from our data, H+-ATPases seem to play an important role in calcification in T. heimii, which is in agreement to observations for E. huxleyi and Pleurochrysis carterae [39], [59], [61]. Here we propose a conceptual model of calcification in T. heimii, which comprises some of the main processes described in this study (Fig. 5). Although many processes remain to be elucidated, this is a first step towards understanding the process of calcification in dinoflagellates.

Paleo Proxies

The δ18O isotopic composition of T. heimii cysts has been used for the reconstruction of past temperatures [22], [62]. Indeed, δ18O changed linearly from about −1 to −4 ‰ with an increase in temperature from about 12 to 30°C. At the same time, however, pH decreased from about 8.4 to 7.9 in this study [22]. Hence, the observed changes in δ18O were most probably a result of both changes in temperature and seawater carbonate chemistry [see also 62]. Here we show remarkable changes in δ18O from about 0 to −5 ‰ with an increase in [CO3 2−] from 50 to 260 µmol L−1, which is largely in agreement to an earlier study including a different T. heimii strain (Fig. 3C) [9]. Interestingly, the observed slopes of δ18O/[CO3 2−] in both T. heimii strains are up to 10-fold steeper compared the coccolithophore Calcidiscus leptoporus and different foraminifera species [9], [25], [63]. Thus, the apparent 18O fractionation during calcification in T. heimii is much more sensitive to changes in [CO3 2−] as compared to other key planktonic marine calcifiers. The steep slope and negative correlation between δ18O and [CO3 2−] observed in both T. heimii strains suggests that the δ18O in T. heimii cysts may be a good candidate to serve as a proxy for past CO3 2− concentrations in ocean waters. This relationship may provide an ideal asset, especially when combined with different δ18O/[CO3 2−] slopes observed in for instance coccolithophores, which will exclude confounding effects of additional environmental parameters such as temperature. Ultimately, this proxy could be further developed for reconstructing past atmospheric pCO2.

Conclusion

We observed a strong reduction in growth rate and calcification of T. heimii under elevated pCO2. Although the function of calcification in T. heimii remains unresolved, it likely plays an important role in its ecological and evolutionary success. Acting on calcification as well as growth, ocean acidification may impose a great threat for T. heimii. Furthermore, the strong correlations between the stable isotope composition and carbonate chemistry suggest a great potential of T. heimii cysts to be used as paleo proxy for reconstructing seawater carbonate chemistry and ultimately past atmospheric pCO2.

Supporting Information

Population growth dynamics. Population densities in each replicate over time in the (A) 150 µatm, (B) 380 µatm, (C) 750 µatm, and (D) 1400 µatm CO2 treatments. Lines indicate an exponential function fitted through the population densities (n = 8) of replicate 1 (black), 2 (grey) and 3 (white), with (A) 1: R2 = 0.98, p<0.0001, 2: R2 = 0.97, p<0.0001, and 3: R2 = 0.97, p<0.0001, (B) 1: R2 = 0.97, p<0.0001, 2: R2 = 0.97, p<0.0001, and 3: R2 = 0.92, p<0.0001, (C) 1: R2 = 0.92, p = 0.0007, 2: R2 = 0.96, p<0.0001, and 3: R2 = 0.97, p<0.0001, and (D) 1: R2 = 0.96, p<0.0001, 2: R2 = 0.95, p<0.0001, and 3: R2 = 0.91, p = 0.0002.

(EPS)

Number of expressed genes. Venn diagram of the number of expressed genes in the 150 µatm, 380 µatm, and 1400 µatm CO2 treatments.

(EPS)

Distribution of expressed genes grouped according to KOG. Values represent the number of genes expressed per KOG, relative to the total number of genes expressed in the respective treatment.

(EPS)

Carbonate chemistry at the start and end of the experiment. Overview of pCO2, pHNBS, dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC), CO2 concentration in the water, total alkalinity (TA), and the seawater calcite saturation state Ωcalcite. Values indicate mean ± SD (n = 3).

(DOCX)

Growth, elemental composition and calcification at the end of the experiment. Overview of growth rate, POC production, carbon quota (TPC, POC, and PIC), PIC:POC ratio, and the number of completed cysts. Values indicate mean ± SD (n = 3).

(DOCX)

Overview of all expressed genes grouped according to KOG.

(XLSX)

Overview of the number of readings for genes associated to ion transport and Ci acquisition.

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

The authors like to thank Yvette Bublitz for assistance with the experiments and Friedel Hinz for assistance with the SEM pictures. The authors thank Ian Probert from Station Biologique de Roscoff for providing Thoracosphaera heimii RCC1512.

Funding Statement

The work was funded by BIOACID, financed by the German Ministry of Education and Research. Furthermore, this work was supported by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme/ERC grant agreements #205150 and #259627, and contributes to the EC FP7 projects EPOCA, grant agreement #211384, and MedSeA, grant agreement #265103. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Sabine CL, Feely RA, Gruber N, Key RM, Lee K, et al. (2004) The oceanic sink for anthropogenic CO2 . Science 305: 367–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Le Quere C, Raupach MR, Canadell JG, Marland G, Bopp L, et al. (2009) Trends in the sources and sinks of carbon dioxide. Nature Geoscience 2: 831–836. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Solomon S, Qin D, Manning M, Marquis M, Averyt K, et al.. (2007) Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- 4. Wolf-Gladrow DA, Riebesell U, Burkhardt S, Bijma J (1999) Direct effects of CO2 concentration on growth and isotopic composition of marine plankton. Tellus Series B-Chemical and Physical Meteorology 51: 461–476. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pandolfi JM, Connolly SR, Marshall DJ, Cohen AL (2011) Projecting coral reef futures under global warming and ocean acidification. Science 333: 418–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moy AD, Howard WR, Bray SG, Trull TW (2009) Reduced calcification in modern Southern Ocean planktonic foraminifera. Nature Geoscience 2: 276–280. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Riebesell U, Zondervan I, Rost B, Tortell PD, Zeebe RE, et al. (2000) Reduced calcification of marine plankton in response to increased atmospheric CO2 . Nature 407: 364–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Beaufort L, Probert I, de Garidel-Thoron T, Bendif EM, Ruiz-Pino D, et al. (2011) Sensitivity of coccolithophores to carbonate chemistry and ocean acidification. Nature 476: 80–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ziveri P, Thoms S, Probert I, Geisen M, Langer G (2012) A universal carbonate ion effect on stable oxygen isotope ratios in unicellular planktonic calcifying organisms. Biogeosciences 9: 1025–1032. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evitt WR (1985) Sporopollen in Dinoflagellate Cysts: Their Morphology and Interpretation. Dallas, Texas, U.S.A.: American Association of Stratigraphic Palynologists Foundation.

- 11.Dale B, Dale AL (1992) Dinoflagellate Contributions to the Deep Sea; Honjo S, editor. Woods Hole, Massachusetts, USA: Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

- 12. Ziveri P, Broerse ATC, van Hinte JE, Westbroek P, Honjo S (2000) The fate of coccoliths at 48 degrees N 21 degrees W, northeastern Atlantic. Deep-Sea Research Part II-Topical Studies in Oceanography 47: 1853–1875. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Karwath B, Janofske D, Willems H (2000) Spatial distribution of the calcareous dinoflagellate Thoracosphaera heimii in the upper water column of the tropical and equatorial Atlantic. International Journal of Earth Sciences 88: 668–679. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wendler I, Zonneveld KAF, Willems H (2002) Production of calcareous dinoflagellate cysts in response to monsoon forcing off Somalia: a sediment trap study. Marine Micropaleontology 46: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zonneveld K (2004) Potential use of stable oxygen isotope composition of Thoracosphaera heimii (Dinophyceae) for upper watercolumn (thermocline) temperature reconstruction. Marine Micropaleontology 50: 307–317. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Inouye I, Pienaar RN (1983) Observations of the life-cycle and microanatomy of Thoracosphaera heimii (Dinophyceae) with special reference to its systematic position. South African Journal of Botany 2: 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Meier KJS, Young JR, Kirsch M, Feist-Burkhardt S (2007) Evolution of different life-cycle strategies in oceanic calcareous dinoflagellates. European Journal of Phycology 42: 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hildebrand-Habel T, Willems H (2000) Distribution of calcareous dinoflagellates from the Maastrichtian to early Miocene of DSDP Site 357 (Rio Grande Rise, western South Atlantic Ocean). International Journal of Earth Sciences 88: 694–707. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gussone N, Zonneveld K, Kuhnert H (2010) Minor element and Ca isotope composition of calcareous dinoflagellate cysts of cultured Thoracosphaera heimii . Earth and Planetary Science Letters 289: 180–188. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bemis BE, Spero HJ, Bijma J, Lea DW (1998) Reevaluation of the oxygen isotopic composition of planktonic foraminifera: Experimental results and revised paleotemperature equations. Paleoceanography 13: 150–160. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ziveri P, Stoll H, Probert I, Klass C, Geisen M, et al. (2003) Stable isotope 'vital effects' in coccolith calcite. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 210: 137–149. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zonneveld KAF, Mackensen A, Baumann KH (2007) Stable oxygen isotopes of Thoracosphaera heimii (Dinophyceae) in relationship to temperature; a culture experiment. Marine Micropaleontology 64: 80–90. [Google Scholar]

- 23. McCrea JM (1950) On the isotopic chemistry of carbonates and a paleotemperature scale. Journal of Chemical Physics 18: 849–857. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zeebe R, Wolf-Gladrow DA (2001) CO2 in Seawater: Equilibrium, Kinetics, Isotopes. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science.

- 25. Spero HJ, Bijma J, Lea DW, Bemis BE (1997) Effect of seawater carbonate concentration on foraminiferal carbon and oxygen isotopes. Nature 390: 497–500. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tangen K, Brand LE, Blackwelder PL, Guillard RRL (1982) Thoracosphaera heimii (Lohmann) Kamptner is a Dinophyte: Observations on its morphology and life-cylce. Marine Micropaleontology 7: 193–212. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Paasche E (2001) A review of the coccolithophorid Emiliania huxleyi (Prymnesiophyceae), with particular reference to growth, coccolith formation, and calcification-photosynthesis interactions. Phycologia 40: 503–529. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pierrot DE, Lewis E, Wallace DWR (2006) MS Exel Program Developed for CO2 System Calculations. ORNL/CDIAC-105a. Oak Ridge, Tennessee, USA: Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Centre, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, US Department of Energy.

- 29. Mehrbach C, Culberson CH, Hawley JE, Pytkowicz RM (1973) Measurement of the apparent dissociation constants of carbonic acid in seawater at atmospheric pressure. Limnology & Oceanography 18: 897–907. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dickson AG, Millero FJ (1987) A comparison of the equilibrium constants for the dissociation of carbonic acid in seawater media. Deep-Sea Research Part I-Oceanographic Research Papers 34: 1733–1743. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dickson AG (1990) Standard potential of the reaction: AgCl(s) +1/2 H2(g) = Ag(s)+HCl(aq), and the standard acidity constant of the ion HSO4 − in synthetic seawater from 273.15 to 318.15 K. Journal of Chemical Thermodynamics 22: 113–127. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nelson ST (2000) A simple, practical methodology for routine VSMOW/SLAP normalization of water samples analyzed by continuous flow methods. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry 14: 1044–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mook WG, Bommerso JC, Staverma WH (1974) Carbon isotope fractionation between dissolved bicarbonate and gaseous carbon-dioxide. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 22: 169–176. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhang J, Quay PD, Wilbur DO (1995) Carbon isotope fractionation during gas-water exchange and dissolution of CO2 . Geochimica Et Cosmochimica Acta 59: 107–114. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Freeman HJ, Hayes JM (1992) Fractionation of carbon isotopes by phytoplankton and estimates of ancient CO2 levels. Global Biogeochem Cycles 6: 185–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zeebe RE (2007) An expression for the overall oxygen isotope fractionation between the sum of dissolved inorganic carbon and water. Geochemistry Geophysics Geosystems 8.

- 37. Beck WC, Grossman EL, Morse JW (2005) Experimental studies of oxygen isotope fractionation in the carbonic acid system at 15 degrees, 25 degrees, and 40 degrees C. Geochimica Et Cosmochimica Acta. 69: 3493–3503. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quinn GP, Keough MJ (2002) Experimental Design and Data Analysis for Biologists. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- 39. Mackinder L, Bach L, Schulz K, Wheeler G, Schroeder D, et al. (2011) The molecular basis of inorganic carbon uptake mechanisms in the coccolithophore Emiliania huxleyi . European Journal of Phycology 46: 142–143. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Riebesell U, Schulz KG, Bellerby RGJ, Botros M, Fritsche P, et al. (2007) Enhanced biological carbon consumption in a high CO2 ocean. Nature 450: 545–U510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tortell PD, Payne CD, Li YY, Trimborn S, Rost B, et al. (2008) CO2 sensitivity of Southern Ocean phytoplankton. Geophysical Research Letters 35.

- 42. Bach LT, Riebesell U, Schulz KG (2011) Distinguishing between the effects of ocean acidification and ocean carbonation in the coccolithophore Emiliania huxleyi . Limnology and Oceanography 56: 2040–2050. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rokitta SD, Rost B (2012) Effects of CO2 and their modulation by light in the life-cycle stages of the coccolithophore Emiliania huxleyi . Limnology and Oceanography 57: 607–618. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hoppe CJM, Langer G, Rost B (2011) Emiliania huxleyi shows identical responses to elevated pCO2 in TA and DIC manipulations. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 406: 54–62. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lohbeck KT, Riebesell U, Reusch TBH (2012) Adaptive evolution of a key phytoplankton species to ocean acidification. Nature Geoscience 5: 346–351. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Collins S, Bell G (2004) Phenotypic consequences of 1,000 generations of selection at elevated CO2 in a green alga. Nature 431: 566–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Giordano M, Beardall J, Raven JA (2005) CO2 concentrating mechanisms in algae: Mechanisms, environmental modulation, and evolution. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 99–131. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48. Rost B, Zondervan I, Wolf-Gladrow D (2008) Sensitivity of phytoplankton to future changes in ocean carbonate chemistry: Current knowledge, contradictions and research directions. Marine Ecology Progress Series 373: 227–237. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reinfelder JR (2011) Carbon Concentrating Mechanisms in Eukaryotic Marine Phytoplankton. In: Carlson CA, Giovannoni SJ, editors. Annual Review of Marine Science. 291–315. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50. Trimborn S, Lundholm N, Thoms S, Richter KU, Krock B, et al. (2008) Inorganic carbon acquisition in potentially toxic and non-toxic diatoms: the effect of pH-induced changes in seawater carbonate chemistry. Physiologia Plantarum 133: 92–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Uehlein N, Lovisolo C, Siefritz F, Kaldenhoff R (2003) The tobacco aquaporin NtAQP1 is a membrane CO2 pore with physiological functions. Nature 425: 734–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kranz SA, Levitan O, Richter KU, Prasil O, Berman-Frank I, et al. (2010) Combined effects of CO2 and light on the N2-fixing cyanobacterium Trichodesmium IMS101: Physiological responses. Plant Physiology 154: 334–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sharkey TD, Berry JA (1985) Carbon isotope fractionation of algae as influenced by an inducible CO2 concentrating mechanism. In: Lucas WJ, Berry JA, editors. Inorganic carbon uptake by aquatic photosynthetic organisms. Rockville, MS, USA: American Society of Plant Physiologists.

- 54. Rost B, Zondervan I, Riebesell U (2002) Light-dependent carbon isotope fractionation in the coccolithophorid Emiliania huxleyi . Limnology and Oceanography 47: 120–128. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Taylor AR, Chrachri A, Wheeler G, Goddard H, Brownlee C (2011) A voltage-gated H+ channel underlying pH homeostasis in calcifying coccolithophores. Plos Biology 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56. Mackinder L, Wheeler G, Schroeder D, Riebesell U, Brownlee C (2010) Molecular mechanisms underlying calcification in coccolithophores. Geomicrobiology Journal 27: 585–595. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Taylor AR, Brownlee C, Wheeler GL (2012) Proton channels in algae: reasons to be excited. Trends in Plant Science 17: 675–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.von Dassow P, Ogata H, Probert I, Wincker P, Da Silva C, et al. (2009) Transcriptome analysis of functional differentiation between haploid and diploid cells of Emiliania huxleyi, a globally significant photosynthetic calcifying cell. Genome Biology 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Rokitta SD, John U, Rost B (2012) Ocean acidification affects redox-balance and ion-homeostasis in the life-cycle stages of Emiliania huxleyi. Plos One 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60. Beyenbach KW, Wieczorek H (2006) The V-type H+ ATPase: molecular structure and function, physiological roles and regulation. Journal of Experimental Biology 209: 577–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Araki Y, Gonzalez EL (1998) V- and P-type Ca2+-stimulated ATPases in a calcifying strain of Pleurochrysis sp. (Haptophyceae). Journal of Phycology 34: 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kohn M, Steinke S, Baumann KH, Donner B, Meggers H, et al. (2011) Stable oxygen isotopes from the calcareous-walled dinoflagellate Thoracosphaera heimii as a proxy for changes in mixed layer temperatures off NW Africa during the last 45,000 yr. Palaeogeography Palaeoclimatology Palaeoecology 302: 311–322. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Zeebe RE (1999) An explanation of the effect of seawater carbonate concentration on foraminiferal oxygen isotopes. Geochimica Et Cosmochimica Acta 63: 2001–2007. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Population growth dynamics. Population densities in each replicate over time in the (A) 150 µatm, (B) 380 µatm, (C) 750 µatm, and (D) 1400 µatm CO2 treatments. Lines indicate an exponential function fitted through the population densities (n = 8) of replicate 1 (black), 2 (grey) and 3 (white), with (A) 1: R2 = 0.98, p<0.0001, 2: R2 = 0.97, p<0.0001, and 3: R2 = 0.97, p<0.0001, (B) 1: R2 = 0.97, p<0.0001, 2: R2 = 0.97, p<0.0001, and 3: R2 = 0.92, p<0.0001, (C) 1: R2 = 0.92, p = 0.0007, 2: R2 = 0.96, p<0.0001, and 3: R2 = 0.97, p<0.0001, and (D) 1: R2 = 0.96, p<0.0001, 2: R2 = 0.95, p<0.0001, and 3: R2 = 0.91, p = 0.0002.

(EPS)

Number of expressed genes. Venn diagram of the number of expressed genes in the 150 µatm, 380 µatm, and 1400 µatm CO2 treatments.

(EPS)

Distribution of expressed genes grouped according to KOG. Values represent the number of genes expressed per KOG, relative to the total number of genes expressed in the respective treatment.

(EPS)

Carbonate chemistry at the start and end of the experiment. Overview of pCO2, pHNBS, dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC), CO2 concentration in the water, total alkalinity (TA), and the seawater calcite saturation state Ωcalcite. Values indicate mean ± SD (n = 3).

(DOCX)

Growth, elemental composition and calcification at the end of the experiment. Overview of growth rate, POC production, carbon quota (TPC, POC, and PIC), PIC:POC ratio, and the number of completed cysts. Values indicate mean ± SD (n = 3).

(DOCX)

Overview of all expressed genes grouped according to KOG.

(XLSX)

Overview of the number of readings for genes associated to ion transport and Ci acquisition.

(XLSX)