Abstract

Chronic Otitis Media (COM) e.g. ‘glue’ ear is characterized by middle ear effusion and conductive hearing loss. Although mucous glycoproteins (mucins), which contribute to increased effusion viscosity, have been analyzed in ear tissue specimens, no studies have been reported that characterize the molecular identity of secreted mucin proteins present in actual middle ear fluid. For this study, effusions from children with COM undergoing myringotomy at Children’s National Medical Center, Washington DC, were collected. These were solubilized, gel-fractionated, and the protein content identified using a liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) proteomics approach. Western blot analyses with mucin specific antibodies, and densitometry were performed to validate the MS findings. LC-MS/MS results identified mucin MUC5B by more than 26 unique peptides in six out of six middle ear effusion samples, while mucin MUC5AC was only identified in one out of six middle ear effusions. These findings were validated by Western blot performed on the same 6 and on an additional 11 separate samples where densitometry revealed on average a 6.4-fold increased signal in MUC5B compared to MUC5AC (p=0.0009). In summary, although both MUC5AC and MUC5B mucins are detected in middle ear effusions, MUC5B appears to be predominant mucin present in COM secretions.

INTRODUCTION

Otitis media (OM) is a ubiquitous condition of early childhood accounting for an enormous amount of public health costs (1–3). COM is characterized by the persistence of middle ear effusion which is most often highly visocus (4). This thick, viscous middle ear effusion has been classically described as ‘glue ear’ (5) and is associated with conductive hearing loss, effusion non-clearance, and increased likelihood of requiring surgical tympanostomy tube placement (6–10). In turn, tympanostomy tube placement is the most common pediatric surgical procedure requiring anesthesia in the US (11).

Mucins are heavily glycosylated proteins which are considered primarily responsible for the gel-like characteristics of mucoid middle ear fluids (12, 13). They are comprised by a heavy carbohydrate content on a core protein backbone consisting of numerous tandem repeats, whose primary amino acid sequence is unique to each mucin (14, 15). These tandem repeat regions contain proline and are high in serine and/or threonine residues, the sites of O-glycosylation (16). Mucins are broadly classified as either cell membrane-bound or secreted (14, 16, 17). To date, 18 human mucin genes coding for mucin glycoproteins have been identified. Of these, MUC2, MUC5AC, MUC5B, MUC6, MUC7, MUC8, MUC9, and MUC19 are secreted. From studies of human airway secretions, it is clear that MUC5AC and MUC5B, and to a much lesser extent, MUC2, are key determinants of airway mucus gel properties (16, 18).

Past studies have examined mRNA and protein expression levels of mucin gene products in human middle ear tissues by various approaches (Table 1). However, probably due to a lack of readily available mucin specific antibodies, no study has successfully identified the specific mucin protein composition of pathological middle ear effusion samples.

Table 1.

Summary of published studies attempting to characterize middle ear mucins

Previous studies of MUC5AC and MUC5B characterization in the human middle ear

| Reference | MUC5AC mRNA | MUC5AC protein | MUC5B mRNA | MUC5B protein |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kawano(43) | Tissue (+) ISH, Northern blot | Tissue (+) IHC | Tissue (+) ISH, Northern blot | Tissue (+) IHC |

| Chung(4) | NE | Tissue (−) IHC | NE | Tissue (+) IHC |

| Lin(27, 28) | Tissue (−) ISH, Northern blot | Tissue (−) IHC | Tissue (+) ISH, Northern blot | Tissue (+) IHC |

| Takeuchi (31) | Tissue (+) RT-PCR | NE | NE | NE |

| Elsheikh(35) | 16% Effusion samples (+)RT-PCR | NE | 96 % Effusion samples (+)RT-PCR | NE |

| Kerschner, (12) | Cell explants (+)RT-PCR | NE | Cell explants (+)RT-PCR | NE |

Abbreviations: ISH-in situ hybridization, IHC-immunohistochemistry

Emerging techniques in proteomics have significantly improved the ability to globally analyze the proteins within biological samples (19). Currently, the use of mass spectrometry (MS) and database searching is becoming a routine method to identify thousands of proteins in a single sample. One approach relies on one dimensional gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) separation of proteins followed by in gel digestion of specific bands and LC-MS/MS analysis of the resulting peptides. Previous studies have successfully used proteomics approaches to characterize the nature of gel-forming mucins in biospecimens such as pancreatic cyst fluid and saliva. (20–24).

We hypothesized that by employing an unbiased global protein detection proteomics MS approach, the secreted mucin glycoproteins present in human middle ear effusions could be definitively identified.

METHODS

Sample Collection and Preparation

Effusions from children with COM undergoing myringotomy with tube placement at Children’s National Medical Center irrespective of race/ethnicity/gender were collected under IRB approval and parental consent. Patients included subjects presenting to the operating room in a longitudinal fashion between January and June of 2008. Exclusion criteria included: purulent effusion more consistent with acute OM, cleft palate or other craniofacial dysmorphic syndromes, immunosuppressive state or condition, or prior history of skull base radiation therapy or skull base malignancy. Bilateral effusions were combined_into one sample per patient. Collected middle ear effusions were frozen at −80 C and freeze dried by lyophilization for 24 h. Six effusion samples were collected longitudinally for proteomics and western blot analysis. Eleven other separate effusions were collected for further subsequent confirmatory western blot analysis.

Due to the fact that some of the effusion samples had blood contamination, serum from a child with OM was collected as a control. This was done in order to demonstrate as expected that blood does not contain mucin proteins and that the contamination does not account for the potential source of the identified mucins in the middle ear effusions.

SDS-PAGE Electrophoresis

Effusion samples containing 150 μg of proteins were dissolved in Laemili buffer containing 0.1 mM DTT and subjected to one-dimensional SDS gel electrophoresis fractionation at 200V for 50 minutes. The gel was fixed with methanol and stained with Coomassie for protein visualization. Each gel lane was sliced into 32 segments and each slice was digested with trypsin as follows. Briefly, the gel cuts were placed in 100 μL of water and then subjected to two washes with a 1:1 by volume solution of water and acetonitrile. The gel pieces were then dehydrated with acetonitrile and rehydrated using 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate, followed by a 1:1 by volume wash of 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate and acetonitrile. The gels were then dehydrated with acetonitrile, resuspended in digestion buffer containing 12.5 ng/μl of MS grade Trypsin Gold (Promega Corp, Madison, WI), and incubated overnight at 37°C. Extraction of peptides from the gel was then conducted via two washes with 25 mM of ammonium bicarbonate, followed by two washes with a 1:1 by volume solution of 5%-formic acid and acetonitrile. The extracted peptides were then completely dried in a SpeedVac (ThermoScientific, Waltham, MA). A control sample of serum from a healthy patient was subjected to the same protocol as the pathological effusion samples.

MS and Mucin Protein Identification

Dried peptides were resuspended in 10 μL of 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). Each sample (6 μL) was injected via an autosampler and loaded onto a C18 trap column (5μm, 300μm i.d. x 5 mm, LC Packings) for 10 min at a flow rate of 10 μL/min, 100% A. The sample was subsequently separated by a C18 reverse-phase column (3.5 μm, 75 μm x 15 cm, LC Packings) at a flow rate of 250 nL/min using an Eksigent nano-hplc system (Dublin, CA). The mobile phases consisted of water with 0.1% formic acid (A) and 90% acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid (B). A 65 minute linear gradient from 5 to 60% B was employed. Eluted peptides were introduced into the mass spectrometer via a 10 μm silica tip (New Objective Inc., Ringoes, NJ) adapted to a nano-electrospray source (ThermoFisher Scientific). The spray voltage was set at 1.2 kV and the heated capillary at 200 °C. The linear trap quadrupole (LTQ) mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific) was operated in data-dependent mode with dynamic exclusion in which one cycle of experiments consisted of a full-MS (300–2000 m/z) survey scan and five subsequent MS/MS scans of the most intense peaks.

Each survey scan file was searched for protein identification using the Sequest algorithm in the Bioworks Browser software (ThermoFisher Scientific) against the Uniprot database (downloaded June 2009) indexed for Human, fully tryptic peptides, 2 missed cleavages and no modifications. Data generation parameters were Peptide Tolerance of 2 Da and Fragment Ion Tolerance of 1 Da. Results were filtered based on the following criteria: DeltaCn (ΔCn) > 0.1, a variable threshold of Xcorr vs charge state (Xcorr = 1.9 for z = 1, Xcorr = 2.2 for z = 2, and Xcorr = 2.5 for z = 3), peptide probability based score with a p value < 0.005.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis on middle ear secretions was performed using protocols adapted from Berger et al as previously described (25). Briefly samples containing 40 μg total proteins were electrophoresed in 1.0% agarose gels. After electrophoresis, samples were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The MUC5B and MUC5AC positive biologic controls were human saliva to which protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was added at a 1:60 dilution on collection, and Calu-3 lung carcinoma cell lysates, respectively. Affinity purified specific anti-MUC5:TR3A polyclonal antibodies generated in our lab (25) were used. MG2 anti-MUC5B antibodies were procured from Dr. Robert Troxler (26). Primary antibodies were diluted 1:2,000. Secondary antibody used was horse-peroxidase goat anti-rabbit antibody in 25 ml of 5% milk at a dilution of 1:5,000. Blots were developed using the horseradish flouro-illuminescence detection protocol using SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL) for 5 min. The developed blots were exposed and visualized with a charge-coupled device camera equipped Gel Doc 2000 chemiluminescent imaging documentation station (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Exposure time was 1 sec and equal for all blots. The respective intensities of each MUC5AC or MUC5B positive band relative to the positive control in the resulting images were densitometrically semi-quantified with Quantity One 4.3.1 image processing software (BioRad, Hercules, CA) using equal sized box-shaped markers.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

For initial proteomics studies, samples were collected from six COM patients undergoing myringotomy at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, DC. Mean age of patients was 25.3 months (range 16–48 months). Ethnicities included 3 African-American, 2 Hispanic, and 1 Caucasian children. All subjects had presented with effusions lasting greater than 3 months and had conductive hearing loss of 20–40 dB at 500 Hz.

SDS-PAGE and Mucin Protein identification

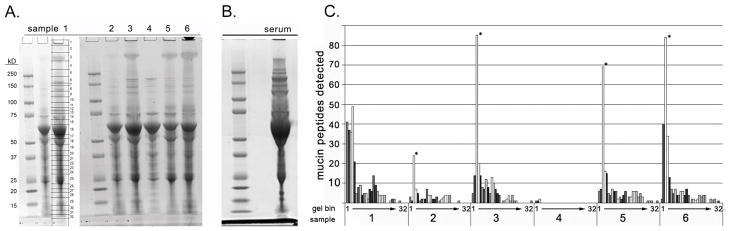

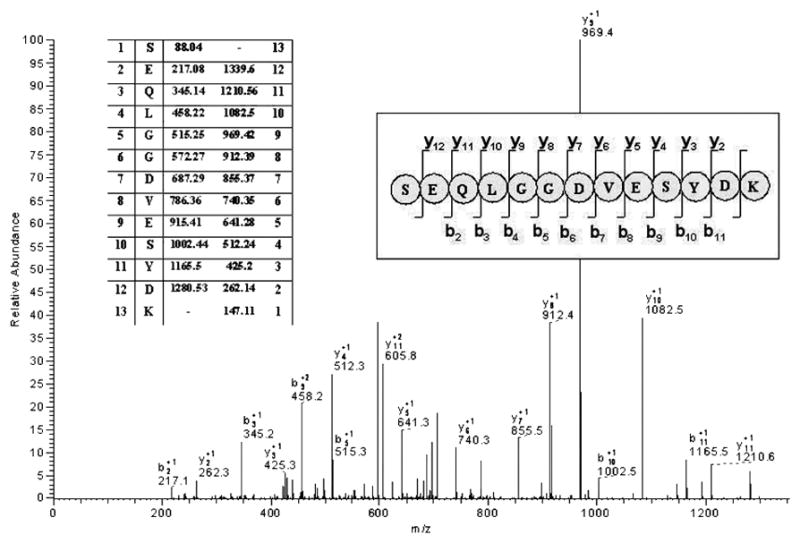

Proteins in effusion samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized using Bio-Safe Coomassie stain (Figure 1A). Due to the contamination of some effusion samples with blood, SDS-PAGE was also performed on a serum sample as a control (Figure 1B). For proteomics analysis, the lanes from each sample were identically cut into 32 gel segment ‘bins’ and processed as described in the Methods (Figure 1A). High molecular weight mucins typically do not stain well with Coomassie but due to their high molecular weight (around 500kD) are expected to travel slowly across the gel, placing corresponding bands at a final position relatively close to the top of the gel. Indeed MS analysis revealed that a majority of mucin corresponding peptides were detected at the top of the lane (Figure 1C). Results indicated that each sample contained MUC5B. Only one sample (#3) was conclusively determined to have MUC5AC in addition to MUC5B (Table 2). These tryptic peptides are unique to each mucin and can be reliably used to distinguish MUC5B from MUC5AC. Figure S1, http://links.lww.com/PDR/XXX shows the localization of each unique peptide along the amino acid sequence of MUC5B and MUC5AC. A representative fragmentation spectrum (MS/MS) generated for a prevalent unique peptide from MUC5B, SEQLGGDVESYDK, is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1. SDS-PAGE and Mucin Protein identification.

A. SDS-PAGE of samples 1–6 stained with Coomassie. Each individual sample gel lane was cut into 32 gel segment bins where protein bands were noted with the staining. The gel cuts performed are shown for sample 1. The same cuts were performed for each sample prior to in gel digestion and LC-MS/MS analysis for peptide identification as described in the Methods section. B. SDS-PAGE of serum sample stained with Coomassie. Serum was run as a control because of the blood contamination of the effusion samples. It was important to ensure that identified mucins from the effusion samples would not be identified in serum as well. C. Localization of mucin peptides detected in each effusion sample by location of gel lane segment bin cut. The y-axis represents the number of mucin specific peptides identified by LC-MS/MS. The x-axis represented by the grayscale bars depicts the individual Coomassie blue stained gel band segment ‘bins’ (from 1 to 32 as shown in Figure 1A) that were cut out from the SDS page gels for protein identification from the middle ear effusion samples. Results highlight that the majority of peptides identied to correspond to mucins were found in the gel segment ‘bins’ located to the top of the gel lane (as expected for large molecular weight proteins such as mucins).

Table 2.

MS/MS findings

| Sample | Number of Unique Mucin Peptides Identified | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | MUC5B | 19 |

| 2 | MUC5B | 13 |

| 3 | MUC5AC MUC5B |

6 18 |

| 4 | MUC5B | 2 |

| 5 | MUC5B | 18 |

| 6 | MUC5B | 18 |

Figure 2. Representative MS/MS fragmentation spectrum of a MUC5B tryptic peptide.

Parent tryptic peptides identified by MS are further fragmented along the amide backbone by collision induced dissociation in the mass spectrometer (MS/MS). These fragments, which differ in mass by the loss of amino acids, are displayed in the MS/MS spectrum and enable protein identification based on the amino acid sequence combined with the peptide mass. The figure shows LTQ-MS/MS spectrum of the parent MS tryptic peptide m/z 607.66 corresponding to a doubly charged ion. The series of y and b ion fragments are identified by their mass and resolved to the indicated peptide sequence. This peptide was unambiguously identified as MUC5B corresponding tryptic peptide [SEQLGGDVESYDK].

Overall, 26 unique different identifying peptides were generated for MUC5B and six were generated for MUC5AC throughout in the effusion samples. Tables 3 & 4 show the frequency of times and the gel bin location for which each unique mucin peptide was identified in samples in aggregate (all of the peptides corresponding to MUC5AC were identified in Sample 3). The majority of the peptides were identified in towards the top of the gel, in bin segment #3. However, unique mucin peptides were seen across the entire top-to-bottom of the gel lane bins. The fragments identified towards the bottom of the gel lanes likely correspond to partial mucin protein fragmentation occurring either in the middle ear or during sample processing.

Table 3.

Unique MUC5B peptides identified.

| Peptide | Amino-Acid | Frequency | Bin (1–32) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AAGGAVCEQPLGLECR | 2874–2890 | 2 | 1 |

| AAYEDFNVQLR | 108–119 | 15 | 3,9,10,11,14,18,20,21,22 |

| AFGQFFSPGEVIYNK | 4162–4177 | 2 | 3 |

| ALSIHYK | 5076–5082 | 9 | 1,3,4,5,7,14 |

| AQAQPGVPLR | 2362–2371 | 198 | 1,2,3,4,5,6,7 |

| AVTLSLDGGDTAIR | 489–503 | 36 | 1,3,4,8,11,12,13,15,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,29 |

| DGNYYDVGAR | 1225–1234 | 40 | 2,3,4,5,6,8,9,10,11,12,13,15 |

| EEGLILFDQIPVSSGFSK | 5159–5176 | 19 | 1,3,5,6,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,19 |

| GATGGLCDLTCPPTK | 5290–5304 | 2 | 1 |

| GPGGDPPYK | 976–985 | 29 | 1,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,15,20,21,22 |

| IVTENIPCGTTGTTCSK | 938–954 | 1 | 3 |

| LCLGTCVAYGDGHFITFDGDR | 898–918 | 2 | 23,24 |

| LFVESYELILQEGTFK | 958–973 | 1 | 16 |

| LTDPNSAFSR | 626–635 | 118 | 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,20,21,22,23,27,28,29 |

| LTPLQFGNLQK | 225–236 | 62 | 1,3,4,5,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,17,18,19,20,21,24,25 |

| NGVLVSVLGTTTMR | 5114–5127 | 7 | 3 |

| NWEQEGVFK | 1576–1585 | 18 | 2,3,4,5,7,8,9,10,11 |

| PGFVTVTRPR | 5403–5412 | 3 | 7,8,12 |

| SEQLGGDVESYDK | 1521–1532 | 69 | 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11, |

| SMDIVLTVTMVHGK | 5082–5095 | 6 | 3,3,8 |

| SVVGDALEFGNSWK | 1043–1056 | 27 | 1,3,4,5,8,10,11,12,13,14,15,20,21,23,24,29,31 |

| TGLLVEQSGDYIK | 162–174 | 62 | 3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,19,20,21,24,26,27,29 |

| VCGLCGNFDDNAINDFATR | 1047–1062 | 20 | 3,4,5,11,12,15,19,20,21,23,24,28 |

| VYKPCGPIQPATCNSR | 5302–5317 | 1 | 3 |

| YAYVVDACQPTCR | 699–714 | 2 | 8,9 |

The table summarizes the location of each unique peptide along the amino-acid sequence of MUC5B. The number of times each peptide was seen in aggregate for all samples is listed. Also, the position of where the peptide was identified along the gel lane (bin number) is shown. For each bin, some unique peptides were identified numerous times.

Table 4.

Unique MUC5AC peptides identified.

| Peptide | Amino-Acid | Frequency | Bin (1–32) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AEDAPGVPLR | 1431–1440 | 1 | 3 |

| GTDSGDFDTLENLR | 1399–1413 | 2 | 3,5 |

| HQDGLVVVTTK | 4860–4870 | 2 | 8,9 |

| NQDQQGPFK | 2723–2732 | 1 | 3 |

| RPEEITR | 4045–4051 | 8 | 3,4 |

| SYRPGAVVPSDK | 1243–1254 | 1 | 3 |

The table summarizes the location of each unique peptide along the amino-acid sequence of MUC5AC. For MAUC5AC, all of these unique peptides were only seen in sample 3. Also, the position of where the peptide was identified along the gel lane (bin number) is shown. For each bin, some unique peptides were identified numerous times.

Proteins identified in the prominent bands corresponding to gel bins #16 and #25 primarily consisted of serum associated proteins and are likely representative of serum contamination. As such, these 2 bands (#16 and #25) figured prominently in the serum control sample. Table S1, http://links.lww.com/PDR/XXX contains a list of all of the proteins identified definitively by our analysis.

Western Blot analysis

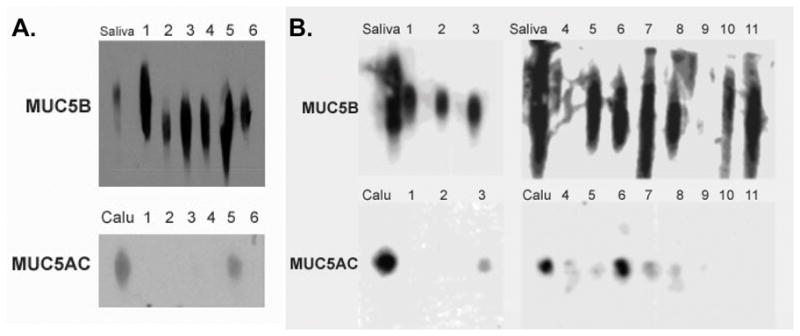

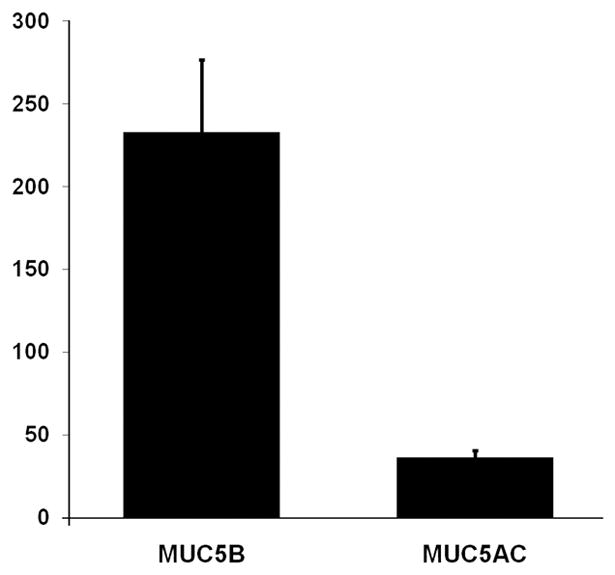

The proteomics data was further validated by Western blot analysis of COM secretions on 1% agarose gels. Since the only 2 mucins identified by proteomics were MUC5B and MUC5AC, western blots were performed for those 2 mucins. Results revealed strong signal for MUC5B and faint signal for MUC5AC in all samples as expected (Figure 3A). To further characterize and confirm our findings, age matched effusion samples were then collected from 11 separate children with COM for Western blot studies. In these additional children, mean age of patients was 24 months (range 13–48 months). Ethnicities included 4 African-American, 4 Hispanic, and 3 Caucasian children. All subjects had also presented with effusions lasting greater than 3 months and had conductive hearing loss of 20–40 dB at 500 Hz. Western blot results revealed strong MUC5B signal intensity in 9/11 effusion samples (Figure 3B). Strong signal intensity for MUC5AC was seen in only 1/11 samples (Figure 3B, lane 6 bottom panel). Faint MUC5AC signal was noted in another 4 samples (Figure 3B, lanes 3,5,7,9 bottom panel). Semi-quantitative densitometry results for each sample revealed that overall there was an average of 6.4-fold increased signal in MUC5B compared to MUC5AC (p=0.0009) (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Western blots.

A. Western blot results for 6 samples tested with proteomics. Strong signal compared to positive biological control (saliva) was noted in all samples blotted for MUC5B. Faint signal compared to positive biological control (Calu-3 cell extracts) was noted in samples blotted for MUC5AC. All wells were loaded with 40μg of protein. Lane numbers corresponds to sample numbers used in proteomics analysis. B. Western blot results revealed strong MUC5B (upper panel) signal intensity in 9/11 separate, additional effusion samples (not in lanes 4 and 9). MUC5AC (lower panel) demonstrated strong signal intensity in only 1/11 samples (lane 6). Faint MUC5AC signal was noted in another 4 samples (lanes 3,5,7,9). All wells were loaded with 40 μg of protein. Lane numbers correspond to 11 separate COM samples used as validation. Positive biologic control for MUC5B (upper panel) was saliva. Positive biologic control for MUC5AC (lower panel) was whole Calu-3 cell extracts.

Figure 4. Average western blot densitometry signal.

A. Average densitometric signal intensity of all sample signal/positive biologic control signal combined. Y-axis represents dots per inch of average density signal of each sample normalized to the biological positive control signal on the same gel/blot. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (p=0.0009, two-tailed Student’s t-test).

DISCUSSION

Mucins are complex glycoproteins characterized by an extensive number of tandem repeat regions in their protein backbones onto which a large number of O-glycosydes are attached. Prior studies have identified both secretory and transmembrane mucin mRNA and proteins in the middle ear tissue (12, 27–30) and one study established the presence of multiple mucin mRNA molecules in the effusions of COM patients (31). Large-scale studies of gene expression on the RNA, protein, and/or metabolite level have demonstrated that the correlation of protein to corresponding mRNA levels within tissue samples is most often surprisingly low (32). Thus, studies looking solely at mRNA levels in middle ear tissue specimens cannot conclusively extrapolate presence or absence of proteins, especially within secretions. Due to a lack of molecular tools and techniques, no study has comprehensively examined the expression of mucin proteins in middle ear effusions.

MS has evolved as a high throughput, sensitive and specific technique to identify the protein composition of biospecimens in general (33). Mucin proteins in biofluids can also be specifically identified by MS (20–24). Our MS analysis detected 26 distinct peptides for MUC5B (an average of 14.6 unique peptides per sample), well over the threshold limit of two peptides considered necessary to identify a protein, strongly indicating the definitive presence of MUC5B in middle ear effusions of COM patients. MUC5AC was only conclusively identified in one sample, and only with six unique peptides. Based on the robustness of peptides generated from MUC5B, the data indicate that MUC5B is the predominant mucin isolated in these COM effusions, with MUC5AC exhibiting a relatively minor presence. Western blot data confirmed these MS findings. Because the MS data was searched against the entire Uniprot database for human trypsin-digested proteins, this experiment also validly demonstrated the lack of other secreted mucins (MUC2, MUC19, MUC7) present in these effusions. It is possible that these other secreted mucins are present in such low amounts that they fall below the detection sensitivity of the gel fractionation and LC-MS/MS proteomics approach or that they were degraded either by blood contaminants or during sample processing. As expected, no mucin proteins were identified in serum; ruling out blood contamination as the source of the mucins found in the middle ear effusions.

Our finding that MUC5B comprises the predominant mucin glycoprotein in middle ear effusions is in line with other reports that show that middle ear epithelial biopsies and tissues specimens express primarily MUC5B mRNA and protein over that of other mucins (4, 27, 28, 34, 35). The middle ear has a unique profile in expression of mucins under normal physiological conditions. Studies have shown that whereas MUC5AC RNA and protein is primarily expressed in respiratory tract epithelium under normal conditions with MUC5B only faintly identified (16, 36, 37), middle ear epithelium expresses MUC5B RNA and protein primarily under normal conditions (27, 28). With inflammatory stimulation, such as that associated with acute otitis, mucin gene expression and protein secretion increases. This has been demonstrated in cell models of OM (12, 38) and in tissue biopsies (27, 28). Interestingly, of the known mucins, MUC5B has the largest central tandem repeat region (39). It also possesses a very large heavily glycosylated protein backbone, two separate glycoforms (a low and high weight) capable of crosslinking, and particularly stringent polymerization pattern resistant to DTT reduction (40). Based upon this, it is likely that MUC5B is an extremely viscous human mucin protein, if not plausibly the most viscous. The predominance of MUC5B may represent the physicochemical reason that COM fluid is so often impressively viscous and why ‘glue’ ear effusions at times do not readily clear through the Eustachian tube. Along these lines, MUC5B has also been identified as the predominant mucin glycoprotein in the gel phase of thick fatally obstructing secretions from patients that die from status asthmaticus (41, 42). Interestingly, this demonstrated MUC5B predominance in the middle ear may also explain why primary lung diseases of mucin dysregulation, such as cystic fibrosis, where MUC5AC is predominant, may spare the middle ear. Recognition of MUC5B as the primary mucin in COM effusions should lead to research into specific therapeutic approaches targeting MUC5B biochemically. To date no effective medical options exist to effectively treat and resolve COM.

CONCLUSIONS

Based on our findings, it appears that although both MUC5AC and MUC5B can be identified in mucoid middle ear effusions, MUC5B appears to be predominant middle ear secretory mucin protein present while MUC5AC is either absent in a majority of effusions or very faintly perceptible by proteomics or standard immunobloting techniques. Developing biochemical approaches to target MUC5B may prove a successful strategy for drug development in COM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Statement of Financial Support: This work was supported by funding from an NIH National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, K12 Genomics of Lung Grant, HL090020-01 [E.H.], Intellectual and Developmental Disability Research Centers Core Grants 1P30HD40677 and 5R24HD050846 to the Center for Genetic Medicine at Children’s National Medical Center, and an Avery Scholar Award from Children’s National Medical Center [D.P.].

ABBREVIATIONS

- COM

Chronic Otitis Media

- OM

Otitis Media

- LC-MS/MS

Liquid tandem mass spectrometry

- MS

Mass spectrometry

- MS/MS

Tandem mass spectrometry

- MUC

Mucin

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Pediatric Research Articles Ahead of Print contains articles in unedited manuscript form that have been peer-reviewed and accepted for publication. As a service to our readers, we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final definitive form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered, which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.pedresearch.org).

REFERNCES

- 1.Cherry DK, Woodwell DA. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2000 summary. Adv Data. 2002;328:1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenfeld RM, Casselbrant ML, Hannley MT. Implications of the AHRQ evidence report on acute otitis media. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125:440–448. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2001.119326. discussion 439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McIntosh ED, Conway P, Willingham J, Lloyd A. The cost-burden of paediatric pneumococcal disease in the UK and the potential cost-effectiveness of prevention using 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Vaccine. 2003;21:2564–2572. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung MH, Choi JY, Lee WS, Kim HN, Yoon JH. Compositional difference in middle ear effusion: mucous versus serous. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:152–155. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200201000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glue ear. BMJ. 1969;4:578. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klein JO. The burden of otitis media. Vaccine. 2000;19:S2–S8. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00271-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teele DW, Klein JO, Rosner BA. Otitis media with effusion during the first three years of life and development of speech and language. Pediatrics. 1984;74:282–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown DT, Litt M, Potsic WP. A study of mucus glycoproteins in secretory otitis media. Arch Otolaryngol. 1985;111:688–695. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1985.00800120082011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carrie S, Hutton DA, Birchall JP, Green GG, Pearson JP. Otitis media with effusion: components which contribute to the viscous properties. Acta Otolaryngol. 1992;112:504–511. doi: 10.3109/00016489209137432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lous J, Burton MJ, Felding JU, Ovesen T, Rovers MM, Williamson I. Grommets (ventilation tubes) for hearing loss associated with otitis media with effusion in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005:CD001801. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001801.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bluestone CD, Stool SE, Kenna MA. Pediatric otolaryngology. Saunders; Philadelphia: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kerschner JE. Mucin gene expression in human middle ear epithelium. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:1666–1676. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31806db531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giebink GS, Le CT, Paparella MM. Epidemiology of otitis media with effusion in children. Arch Otolaryngol. 1982;108:563–566. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1982.00790570029007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rose MC. Mucins: structure, function, and role in pulmonary diseases. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:L413–L429. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1992.263.4.L413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ali MS, Pearson JP. Upper airway mucin gene expression: a review. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:932–938. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e3180383651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rose MC, Voynow JA. Respiratory tract mucin genes and mucin glycoproteins in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:245–278. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00010.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gendler SJ, Spicer AP. Epithelial mucin genes. Annu Rev Physiol. 1995;57:607–634. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.003135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hovenberg HW, Davies JR, Herrmann A, Linden CJ, Carlstedt I. MUC5AC, but not MUC2, is a prominent mucin in respiratory secretions. Glycoconj J. 1996;13:839–847. doi: 10.1007/BF00702348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hathout Y. Approaches to the study of the cell secretome. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2007;4:239–248. doi: 10.1586/14789450.4.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ke E, Patel BB, Liu T, Li XM, Haluszka O, Hoffman JP, Ehya H, Young NA, Watson JC, Weinberg DS, Nguyen MT, Cohen SJ, Meropol NJ, Litwin S, Tokar JL, Yeung AT. Proteomic analyses of pancreatic cyst fluids. Pancreas. 2009;38:e33–e42. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318193a08f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rousseau K, Kirkham S, Johnson L, Fitzpatrick B, Howard M, Adams EJ, Rogers DF, Knight D, Clegg P, Thornton DJ. Proteomic analysis of polymeric salivary mucins: no evidence for MUC19 in human saliva. Biochem J. 2008;413:545–552. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rousseau K, Kirkham S, McKane S, Newton R, Clegg P, Thornton DJ. Muc5b and Muc5ac are the major oligomeric mucins in equine airway mucus. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L1396–L1404. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00444.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andersch-Björkman Y, Thomsson KA, Holmén Larsson JM, Ekerhovd E, Hansson GC. Large scale identification of proteins, mucins, and their O-glycosylation in the endocervical mucus during the menstrual cycle. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:708–716. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600439-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walz A, Stuhler K, Wattenberg A, Hawranke E, Meyer HE, Schmalz G, Bluggel M, Ruhl S. Proteome analysis of glandular parotid and submandibular-sublingual saliva in comparison to whole human saliva by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Proteomics. 2006;6:1631–1639. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berger JT, Voynow JA, Peters KW, Rose MC. Respiratory carcinoma cell lines. MUC genes and glycoconjugates. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;20:500–510. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.3.3383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Troxler RF, Offner GD, Zhang F, Iontcheva I, Oppenheim FG. Molecular cloning of a novel high molecular weight mucin (MG1) from human sublingual gland. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;217:1112–1119. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin J, Tsuprun V, Kawano H, Paparella MM, Zhang Z, Anway R, Ho SB. Characterization of mucins in human middle ear and Eustachian tube. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;280:L1157–L1167. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.6.L1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin J, Tsuboi Y, Rimell F, Liu G, Toyama K, Kawano H, Paparella MM, Ho SB. Expression of mucins in mucoid otitis media. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2003;4:384–393. doi: 10.1007/s10162-002-3023-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi JY, Kim CH, Lee WS, Kim HN, Song KS, Yoon JH. Ciliary and secretory differentiation of normal human middle ear epithelial cells. Acta Otolaryngol. 2002;122:270–275. doi: 10.1080/000164802753648141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ubell ML, Kerschner JE, Wackym PA, Burrows A. MUC2 expression in human middle ear epithelium of patients with otitis media. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;134:39–44. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2007.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takeuchi K, Yagawa M, Ishinaga H, Kishioka C, Harada T, Majima Y. Mucin gene expression in the effusions of otitis media with effusion. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2003;67:53–58. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(02)00361-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jansen RC, Nap JP, Mlynarova L. Errors in genomics and proteomics. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:19. doi: 10.1038/nbt0102-19b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kussmann M, Raymond F, Affolter M. OMICS-driven biomarker discovery in nutrition and health. J Biotechnol. 2006;124:758–787. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schousboe LP, Rasmussen LM, Ovesen T. Induction of mucin and adhesion molecules in middle ear mucosa. Acta Otolaryngol. 2001;121:596–601. doi: 10.1080/000164801316878881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elsheikh MN, Mahfouz ME. Up-Regulation of MUC5AC and MUC5B Mucin Genes in Nasopharyngeal Respiratory Mucosa and Selective Up-Regulation of MUC5B in Middle Ear in Pediatric Otitis Media with Effusion. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:365–369. doi: 10.1097/01.MLG.0000195290.71090.A1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reid CJ, Gould S, Harris A. Developmental expression of mucin genes in the human respiratory tract. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1997;17:592–598. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.17.5.2798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Audie JP, Janin A, Porchet N, Copin MC, Gosselin B, Aubert JP. Expression of human mucin genes in respiratory, digestive, and reproductive tracts ascertained by in situ hybridization. J Histochem Cytochem. 1993;41:1479–1485. doi: 10.1177/41.10.8245407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Preciado D, Lin J, Wuertz B, Rose M. Cigarette smoke activates NF kappa B and induces Muc5b expression in mouse middle ear cells. Laryngoscope. 2008;118:464–471. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e3185aedc7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Desseyn JL, Guyonnet-Duperat V, Porchet N, Aubert JP, Laine A. Human mucin gene MUC5B, the 10.7-kb large central exon encodes various alternate subdomains resulting in a super-repeat. Structural evidence for a 11p15.5 gene family. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3168–3178. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keates AC, Nunes DP, Afdhal NH, Troxler RF, Offner GD. Molecular cloning of a major human gall bladder mucin: complete C-terminal sequence and genomic organization of MUC5B. Biochem J. 1997;324:295–303. doi: 10.1042/bj3240295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sheehan JK, Howard M, Richardson PS, Longwill T, Thornton DJ. Physical characterization of a low-charge glycoform of the MUC5B mucin comprising the gel-phase of an asthmatic respiratory mucous plug. Biochem J. 1999;338:507–513. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Groneberg DA, Eynott PR, Lim S, Oates T, Wu R, Carlstedt I, Roberts P, McCann B, Nicholson AG, Harrison BD, Chung KF. Expression of respiratory mucins in fatal status asthmaticus and mild asthma. Histopathology. 2002;40:367–373. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.01378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kawano H, Paparella MM, Ho SB, Schachern PA, Morizono N, Le CT, Lin J. Identification of MUC5B mucin gene in human middle ear with chronic otitis media. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:668–673. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200004000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.