Abstract

Objective

Psychological stress can upregulate inflammatory processes and increase disease risk. In the context of stress, differences in how individuals cope might have implications for health. The goal of this study was to evaluate associations among stress, coping, and inflammation in a sample of African-American and white adolescents.

Methods

Adolescents (n = 245) completed self-report measures of stressful life events and coping, provided daily diary reports of interpersonal conflict over seven days, and provided fasting blood samples for assessment of C-reactive protein (CRP).

Results

In regression analyses adjusted for age, sex, race, body mass index, smoking, and socioeconomic status, there were no significant associations between stress and CRP, but significant interactions between stress and coping emerged. For adolescents reporting more unpleasant stressful life events in the past 12 months, positive engagement coping was inversely associated with CRP (β = −.19, p < .05), whereas coping was not significantly associated with CRP for adolescents reporting fewer stressful life events. Positive engagement coping was significantly and inversely associated with CRP in the context of interpersonal stress, whether measured as stressful life events reflecting interpersonal conflict (e.g., arguments with parents or siblings, conflict between adults in the home, friendship ended) or frequency of arguments with others reported in daily diaries. Disengagement coping was unrelated to CRP.

Conclusion

Findings suggest that positive engagement coping is associated with lower levels of inflammation, but only when adolescents are challenged by significant stress.

Keywords: adolescents, coping, inflammation, psychological stress, psychoneuroimmunology

In adults, psychological stress is associated with upregulated inflammatory activity, including elevations in inflammatory markers in response to acute laboratory stress (1) and to chronic naturalistic stressors (e.g., caregiving, 2). Given the contribution of inflammation to cardiovascular disease and other chronic illnesses, repeated exposure to stress-induced increases in inflammatory markers may cumulatively affect health, especially if the association between stress and inflammation begins early in life.

A recent review identified ten papers investigating the association between interpersonal stress and inflammatory biomarkers in children and adolescents, concluding that the evidence supporting a relationship between stress and inflammation in youth is mixed (3). For example, a study assessing interpersonal stress via daily diaries found significant associations with elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) in a sample of white and Latin-American adolescents (4). However, a study of adolescent females of white and Asian-American backgrounds found no significant association between chronic interpersonal stress (assessed via interview) and circulating CRP or other biomarkers (although there were positive associations with proinflammatory signaling molecules and stimulated proinflammatory cytokine production in vitro; 5). Although there are many methodological differences among the 10 studies that may account for these discrepant findings, one likely contributing factor is that stress interacts with other variables to influence CRP.

Variability in how individuals cope with or manage stress cognitively and behaviorally may interact with stress to influence inflammatory biomarkers. Coping is a clinically important individual difference variable to examine, as coping can be potentially modified by intervention (6). The influence of coping on health may be most evident when there exists significant stress with which to cope. Under conditions of stress, when the sympathetic nervous system and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis are activated, a more salutary coping style may confer resilience and reduce physiological and inflammatory activation. In contrast, maladaptive coping may prolong or exacerbate both the psychological and physiological effects of stress. Coping through strategies aimed at engaging in positive thoughts and behaviors are generally linked to positive psychological and physical health, whereas coping strategies involving disengagement or avoidance of stress-related thoughts and feelings are usually associated with greater distress and worse health outcomes (7). Whether these patterns of associations with coping strategies hold true with respect to circulating inflammation, particularly in adolescents, has not yet been examined.

The goal of this study was to evaluate associations among stress, coping, and inflammation in a sample of African-American and white adolescents. In this sample, we assessed usual ways of coping with stress, including strategies reflecting positive engagement (e.g. positively reappraising the stressful situation or engaging in other positive behaviors, such as trying to improve oneself or develop self-sufficiency) and strategies reflecting disengagement (e.g. distracting oneself, using alcohol or tobacco, venting). We hypothesized that adolescents reporting greater stress would exhibit higher CRP levels and that among individuals under high stress, positive engagement coping would be associated with lower CRP, whereas disengagement coping would be associated with greater CRP.

METHODS

Participants and Research Design

Participants were 250 adolescents between the ages of 14 and 19 from a public high school near Pittsburgh, PA. Participants were recruited from health classes between 2008 and 2011 for an adolescent health project designed to measure sleep and risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Exclusionary criteria for study participation included parental report of children’s cardiovascular or kidney disease, use of medication for emotional problems, diabetes or high blood pressure, and use of medication known to affect the cardiovascular system or sleep. Of the 250 adolescents who enrolled in the study, two adolescents had body mass index (BMI) values that fell over 4 standard deviations from the sample mean (54.6 and 58.2) and were excluded from analyses. One adolescent reported symptoms of acute infection at the time of the blood draw and two others did not provide blood samples. Thus, five participants were excluded from the current analyses. The final sample consisted of 245 adolescents, although sample sizes differed slightly across analyses due to missing self-report or covariate data for some participants.

After obtaining signed informed consent from the parent/guardian and student, parents/guardians were interviewed regarding household socioeconomic status and family medical history. Students were then scheduled to complete a 7-day study protocol, which included completion of a battery of psychosocial questionnaires via protected web access, daily diaries completed on handheld computers in conjunction with ambulatory blood pressure and actigraphy, and a fasting blood draw. The staff reminded participants of their appointments one or two days prior, verified that they were well, and the trained phlebotomist also verified that the participant was healthy and not on medications for infectious disease on the day of draw. Participants who reported being ill, usually a cold or flu, were rescheduled. Upon completion of the study protocol, participants were compensated $100 for successful participation in the research project. This study protocol was approved by the University of Pittsburgh IRB.

Measures

CRP

CRP was selected as a summary marker of systemic inflammation, as it has a long-half life and is detectable at low levels. Fasting blood samples were obtained and serum was separated by refrigerated centrifuge. Serum was then aliquoted and stored at −80 C until assay in the Heinz Lipid Laboratory at the Graduate School of Public Health at the University of Pittsburgh. In this laboratory duplicate samples, standards and control sera are included in each run. CRP was measured turbidimetrically by measuring increased absorbance when the CRP in the sample reacts with anti-CRP antibodies. The intra-assay coefficient of variation was 5.5% and inter-assay coefficient of variation was 3.0%.

Stressful life events

The Life Events Questionnaire – Adolescent was developed to understand the relation between stressful life experiences and adolescent adjustment (8). The scale was revised to include age-appropriate items and to improve its psychometric properties. Students were asked to indicate whether a particular life event occurred in the past 12 months. If it did occur they were asked to rate the event on a 4-point scale (ranging from very unpleasant to very pleasant). Two summary measures were extracted from this scale: the number of events rated as “very unpleasant” and the number of interpersonal conflict events endorsed (many arguments between adults living in the house / many arguments with brothers and/or sisters / many arguments with parents / close friendship ended / stopped dating).

Daily interpersonal conflict

On seven consecutive nights, participants completed a diary at bedtime that asked whether any of the following events had happened that day: arguments/tension with family, arguments/tension with friends, and arguments/tension with others (teacher, principal, boss, etc.). Responses were aggregated across the seven days and coded on a 4-point scale, which was analyzed as a continuous variable: no arguments reported during the sampling period (18% of participants), arguments reported on up to one-third of diaries completed (26% of participants), arguments reported on one-third to two-third of diaries completed (33% of participants), and arguments reported on two-third to 100% of diaries completed (24% of participants).

Coping

Approximately half the items of the original adolescent coping style and behaviors questionnaire developed by Patterson & McCubbin (9) were used to assess usual coping strategies. On a 5-point scale ranging from “never” to “most of the time,” participants were asked how often they employed different means of coping “when you face difficulties or feel stressed.” Factor analysis of the items summed within the original subscales (9) followed by varimax rotation yielded three factors above eigenvalue of 1, accounting for 53% of the variance. The positive engagement coping scale contained the items “try to improve yourself,” “try to think of the good things in your life,” “joke and keep a sense of humor,” “try to be funny and make light of it all,” “try, on your own, to figure out how to deal with your problems or tension,” “try to see the good in a difficult situation,” and “do strenuous physical activity” (alpha = .73, all factor loadings > .70). The disengagement coping scale contained the following items: “listen to music,” “eat food,” “get angry and yell at people,” “let off steam by complaining to family members or friends,” “blame others for what’s going on,” “daydream about how you would like things to be,” “smoke,” “watch tv or dvd,” “drink beer, wine, liquor,” “sleep” and “play video games or surf the web” (alpha = .69, all factor loadings > .53). The third scale contained the items “try to reason with parents and talk things out, compromise,” “talk to your mother or father about what bothers you,” “talk to a brother or sister about how you feel,” “pray,” and “talk to a friend about how you feel” (alpha = .61, all factor loadings > .46). Because we did not have specific hypotheses about this amalgamation of social support seeking and spiritual coping, we did not conduct analyses with this scale.

Potential confounds

Age, gender, and smoking (any vs. no cigarettes in the past 30 days) were determined by adolescent self–report. BMI was derived from weight and height measured on a calibrated scale to the nearest 0.1 kg and 0.1 cm, respectively. Parents/guardians reported gross annual family income, which was adjusted for household size (i.e., the number of adults and children) and log transformed to reduce skewness. Additionally, because the parents of 15 participants declined to provide information about their family income, we imputed income data by identifying families with similar structure (i.e. number of adults and children in the same household) and using the midpoint of the average income category for the comparable family constellations.

Statistical Analysis

A series of hierarchical linear regressions were conducted to examine whether stress (i.e., number of very unpleasant stressful life events, number of interpersonal conflict life events, daily interpersonal conflict), coping (i.e., positive engagement and disengagement), and the interaction between stress and coping are associated with CRP. Total scores on stress and coping scales were centered prior to analyses. CRP was not normally distributed and was log transformed for regression analyses. All models adjusted for age, race, gender, BMI, smoking, and family income. Significant interactions were analyzed via the method of Aiken and West (10) for continuous variables. Statistical significance was set at p <.05 (two-tailed). Analyses were conducted with SPSS, Version 19 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Sample characteristics are presented in Table 1. Approximately half of participants were female and white, most were nonsmokers, and on average, they were overweight and of lower socioeconomic status. Average levels of CRP were in the intermediate risk category, as would be expected given the relatively young but overweight sample; there were 9 adolescents with CRP values greater than 10, but the pattern of results did not differ when these participants were excluded. CRP was significantly and positively correlated with BMI (r= .47, p < .001) and inversely associated with family income (r = −.14, p = .030) and was higher among white participants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample (n = 245)

| Variable | Mean ± SD (range) or Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | 15.71 ± 1.30 (14 – 19) |

| Female | 129 (52.7%) |

| White | 107 (43.7%) |

| Body Mass Index | 26.09 ± 5.85 (16.44 – 46.89) |

| Smoked a cigarette in the past 30 days | 62 (25.7%) |

| Household Income > 25K | 113 (46%) |

| Stress | |

| Number of very unpleasant life events in past year | 3.63 ±3.42 (0 – 21) |

| Number of interpersonal conflict life events in past year | 2.24 ± 1.49 (0 – 5) |

| Frequent daily conflict (> 67% of days) | 57 (23.7%) |

| Coping | |

| Positive engagement coping | 3.27 ±.71 (1 – 5) |

| Disengagement coping | 2.79 ±.59 (1 – 5) |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 1.71 ± 3.15 (.03 – 23.10) |

| > 3 mg/L | 33 (13.5%) |

| > 10 mg/L | 9 (3.7%) |

With regard to stress, number of unpleasant life events in the past year was not significantly associated with any of the covariates. Females reported more interpersonal conflict life events (t(241) = −3.05, p = .003) and daily conflict/tension (t(241) = −4.15, p < .001), as did white participants (t(241) = 3.22, p < .001 for interpersonal life events and t(241) = 3.08, p = .002 for daily conflict/tension). Females also endorsed more frequent disengagement coping (t(241) = −3.34), p < .001), as did white participants (t(241) = 2.12, p = .035). Finally, males endorsed more positive engagement coping (t(241) = 2.98, p = .003).

Table 2 shows bivariate correlations among the study variables, including significant associations among the three measures of stress and among the coping scales. In addition more frequent disengagement coping was associated with more frequent daily conflict. No stress or coping measure showed a significant bivariate association with CRP.

Table 2.

Bivariate correlations between stress, coping, and inflammation.

| Unpleasant life events |

Conflict life events |

Daily conflict |

Positive engagement coping |

Disengagement coping |

CRP (log transformed) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conflict life events |

.57*** | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Daily conflict | .20** | .26*** | 1 | - | - | - |

| Positive engagement coping |

−.03 | .00 | −.01 | 1 | - | - |

| Disengagement coping |

.08 | .11 | .22** | .23*** | 1 | - |

| CRP (log transformed) |

.01 | −.03 | .06 | −.03 | .04 | 1 |

p < .01

p < .001

In regression analyses adjusted for age, sex, race, body mass index, smoking, and socioeconomic status, the number of very unpleasant stressful life events in the past 12 months was not significantly associated with CRP (β = −.05, p = .37). However, a significant interaction emerged between unpleasant life events and positive engagement coping (β = −.14, p = .013), such that positive engagement coping was inversely associated with CRP only among adolescents reporting higher levels of stress (β = −.19, p = .025). Coping was not significantly related to CRP among adolescents facing lower levels of stress (β = .11, p = .18). There were no significant interactions between unpleasant life events and disengagement coping.

In regression analyses focused on interpersonal conflict life events, there was no significant association between stress and CRP (β = −.10, p = .10). Again, a significant interaction emerged between positive engagement coping and stress (β = −.12, p = .039), with higher positive engagement coping marginally associated with lower CRP only for adolescents facing high interpersonal stress (β = −.15, p = .067; β = .09, p = .27 among those reporting low stress). There were no significant interactions between interpersonal conflict life events and disengagement coping.

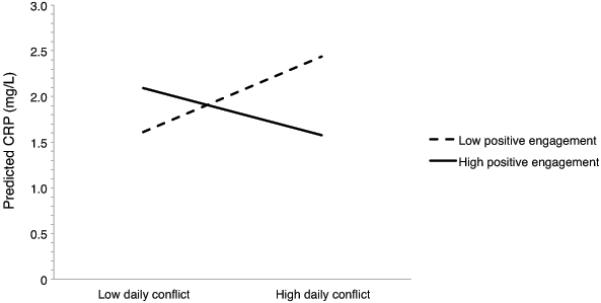

Similarly, although there was no significant association between daily interpersonal conflict/tension and CRP (β = .02, p = .69), there was a significant interaction between daily conflict and positive engagement coping (β = −.13, p = .027) such that coping and CRP were inversely related only among adolescents reporting frequent daily conflict/tension (β = −.16, p = .048; β = .10, p = .23 among those reporting low stress; see Figure). No significant interactions between daily conflict/tension and disengagement coping emerged.

Figure 1.

Effect of high (M + SD) vs. low (M − SD) daily interpersonal conflict and positive engagement coping on C-reactive protein.

DISCUSSION

The current study examined associations between stress and systemic inflammation as indexed by circulating levels of CRP in a sample of African-American and white adolescents. Also examined was the role of coping style in predicting elevated systemic inflammation. Contrary to our hypotheses and some previous research (4), none of our three indicators of psychological stress was positively associated with CRP. We are aware of one other study in adolescents which reported no association between chronic interpersonal stress and circulating inflammatory markers (5).

Our results highlight the importance of considering coping processes when investigating stress and inflammation. As hypothesized, a -coping style characterized by engagement in positive thoughts and behaviors was associated with lower CRP among those adolescents reporting high levels of stress. This was true whether stress was measured as life events rated as very unpleasant, life events reflecting interpersonal conflict (e.g., arguments with parents or siblings), or frequency of arguments with others reported in daily diaries. There was no significant relationship between positive engagement coping and CRP for adolescents reporting lower levels of stress, or between disengagement coping and CRP. These findings are consistent with the literature on the beneficial effects of engagement-oriented coping for adolescent mental health (11). Although interactions between stress and coping on immune function have received surprisingly little attention, the pattern of our results is similar to an earlier cross-sectional study of older adults, which reported that active coping (similar to our positive engagement coping subscale) predicted greater proliferation to mitogens at high stress levels but was unrelated to proliferative responses at lower levels of perceived stress (12). To our knowledge, this is the first examination of stress and coping interactions in relation to systemic inflammation among adolescents. In the context of chronic stress, positive engagement coping may confer resilience to the effects of stress on sympathetic nervous system and HPA activity, mitigating upregulation of inflammatory activity by these systems. In contrast, coping may be unrelated to inflammation in the absence of psychological challenge and the accompanying physiological activation.

This study was limited by its cross-sectional design, which hinders our ability to infer causality. As emphasized by the recent review of the literature on childhood adversity and inflammation, future work should examine trajectories of stress and coping during early life and whether they relate to changes in inflammatory biomarkers over time (3). The inclusion of a single, summary marker of circulating inflammation is another significant limitation, as prior research has demonstrated a relationship between stress and proinflammatory gene expression that was not reflected in elevated serum CRP (5). Finally, the coping scale used in this study asked adolescents to report on how they generally cope when stressed and did not assess coping with interpersonal stressors or conflict specifically. Strengths of the study include the relatively large, diverse sample of adolescents from a lower socioeconomic background, daily assessment of ongoing stress throughout the week, and the consideration of multiple indices of interpersonal stress.

The development and effective deployment of positive engagement coping skills to manage stress early in life may prepare adolescents to cope successfully with future stressors, setting them on a trajectory to cardiovascular resilience rather than risk (13). Most items loading on the positive engagement coping scale in this study (i.e., thinking positively about stressors, trying to improve oneself and develop self-sufficiency) map onto Chen and colleagues’ shift- and-persist model (13). This model suggests that a coping style characterized by both adjusting oneself to stressors (i.e., cognitive reappraisal) and maintaining a broad perspective and focus on the future are especially adaptive for children growing up in low socioeconomic status environments. Our preliminary results suggest that clinical interventions aimed at enhancing engagement in positive reappraisal in combination with goal-oriented behaviors might be beneficial for adolescents facing significant life stress, particularly those who, like our participants, are of low socioeconomic status. Such interventions may not only benefit mental health but could also provide youth with coping skills to minimize stress-induced increases in inflammation throughout adolescence and adulthood, with significant implications for cardiovascular health.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health grants (HL007560, HL25767).

Glossary

- BMI

body mass index

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- HPA

Hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal

Footnotes

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Steptoe A, Hamer M, Chida Y. The effects of acute psychological stress on circulating inflammatory factors in humans: a review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:901–912. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Preacher KJ, MacCallum RC, Atkinson C, Malarkey WB, Glaser R. Chronic stress and age-related increases in the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2003;100:9090–9095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1531903100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slopen N, Koenen KC, Kubzansky LD. Childhood adversity and immune and inflammatory biomarkers associated with cardiovascular risk in youth: a systematic review. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26:239–250. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuligni AJ, Telzer EH, Bower J, Cole SW, Kiang L, Irwin MR. A preliminary study of daily interpersonal stress and C-reactive protein levels among adolescents from Latin American and European backgrounds. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:329–333. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181921b1f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller GE, Rohleder N, Cole SW. Chronic interpersonal stress predicts activation of pro- and anti-inflammatory signaling pathways 6 months later. Psychosom Med. 2009;71 doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318190d7de. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chesney MA, Chambers DB, Taylor JM, Johnson LM, Folkman S. Coping effectiveness training for men living with HIV: results from a randomized clinical trial testing a group-based intervention. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:1038–1046. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000097344.78697.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor SE, Stanton AL. Coping resources, coping processes, and mental health. Annual Rev Clin Psychol. 2007;3:377–401. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masten A, Neeman J, Andenas S. Life events and adjustment in adolescents: The significance of event independence, desirability, and chronicity. J Res Adolesc. 1994;4:71–97. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patterson JM, McCubbin HI. Adolescent coping style and behaviors: conceptualization and measurement. J Adolesc. 1987;10:163–186. doi: 10.1016/s0140-1971(87)80086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aiken SG, West LS. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herman-Stahl MA, Stemmler M, Petersen AC. Approach and avoidant coping: Implications for adolescent mental health. J Youth Adolesc. 1995;24:649–665. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stowell JR, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R. Perceived stress and cellular immunity: when coping counts. J Behav Med. 2001;24:323–339. doi: 10.1023/a:1010630801589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen E, Miller GE. “Shift-and-Persist” Strategies: Why Low Socioeconomic Status Isn’t Always Bad for Health. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2012;7:135–158. doi: 10.1177/1745691612436694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]