Abstract

The Drosophila light activated TRP and TRPL channels have been a model for TRPC channel gating. Several gating mechanisms have been proposed following experiments conducted on photoreceptor and tissue cultured cells. However, conclusive evidence for any mechanism is still lacking. Here, we show that the Drosophila TRPL channel expressed in tissue cultured cells is constitutively active in S2 cells but is silent in HEK cells. Modulations of TRPL channel activity in different expression system by pharmacology or specific enzymes, which change the lipid content of the plasma membrane, resulted in conflicting effects. These findings demonstrate the difficulty in elucidating TRPC gating, as channel behavior is expression system dependent. However, clues on the gating mechanism may arise from understanding how different expression systems affect TRPC channel activation.

Keywords: TRP channels, constitutive activity, gating mechanism, membrane lipids

Introduction

The Drosophila light activated transient receptor potential like (TRPL) is one of the two founding members of the TRP channel superfamily, predominantly expressed in the photoreceptor cells. This channel was discovered independently from the Drosophila TRP channel in a screen for calmodulin-binding proteins.1 The TRPL channel is a nonselective cation channel, a member of the TRPC (canonical) subfamily of TRP channels. Many studies, both in vivo and in expression systems have been conducted on the TRPL channel, making it a model for the TRPC subfamily. The TRPL channel shows different activation states in different expression systems: TRPL channels expressed in Sf9,2,3 S2,4,5 and COS6 cells results in constitutively active channels. However, expression in HEK cells results in a silent channel7 that can be activated via a PLC-mediated G-Protein Coupled Receptor (GPCR) cascade,8 much like light activation in photoreceptor cells.9

Drosophila visual transduction is a phosphoinositide signaling cascade mediated by Gq and phospholipase C (PLC).10 Activation of PLC by a Gq protein promotes the opening of the light activated channels, TRP and TRPL, which depolarize the cell.9,11 Activation of PLC is crucial for the opening of the TRP and TRPL channels under physiological conditions.10,12 However, the mechanism by which PLC activity promotes TRP and TRPL channel openings is still unknown, despite the many efforts. Two types of gating mechanisms have been demonstrated for TRP channels: (1) Direct activation by various stimulations (e.g., temperature, chemical and mechanical stimulations.13 (2) Indirect activation via GPCR and enzymatic cascade.14 Drosophila photoreceptor cells are the prototypic example for indirect activation, where activation of the TRP and TRPL channels is mediated by Gq-protein and PLC.15 However, even the Drosophila channels can be directly activated in vivo by diverse stimuli such as anoxia16 or application of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA).4

Several hypotheses explaining how PLC activity gates the TRPL channel have been proposed: (1) (Ins(1,4,5)P3) receptor activation or Ins(1,4,5)P3-mediated mobilization of Ca2+ from internal stores gates the TRPL channels.17 (2) Dephosphorylation and Ca2+ mobilization promote TRPL channel activation while phosphorylation via a kinase activity promotes their closing18; (3) DAG or its metabolites, such as PUFA, act as second messengers and gate the channels. In this model, a binding site for DAG or PUFA on the channel is assumed19; (4) (PtdIns(4,5)P2) acts as an inhibitor of channel opening. In this disinhibition model, PLC activity results in a reduction of membranous PtdIns(4,5)P2 levels, alleviating its inhibitory effect on the channels and promoting channel openings.2,20 An extended version of this model suggests that PtdIns(4,5)P2 reduction must be accompanied by second messenger production (i.e. DAG) or by cellular acidification, which are also the consequence of PLC activation, in promoting channel opening.21-23 (5) The conversion of PtdIns(4,5)P2, with a large hydrophilic head group into DAG or its metabolites, with a small hydrophilic head group, change the lipid packing at the plasma membrane, promoting TRPL channel opening. This model differs from the latter model as it does not assume a specific binding site on the channels, while the channel interaction with its lipid environment is the crucial factor which determines its activity state.20

In a series of studies, Hardie and colleagues have demonstrated the importance of the DAG branch of the inositol-lipid signaling in TRP and TRPL channel excitation. In a breakthrough study, they showed that poly unsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) promote the opening of the channels, both in photoreceptor cells in the dark and in S2 cells expressing TRPL channels.4 In this study, it was suggested that PUFA, which are DAG derivatives, act as second messengers and gate the channel. In a later work they demonstrated that the light independent retinal degeneration phenotype observed in the rdgA mutant fly (in which DAG kinase is missing) is a consequence of constitutive TRP and TRPL activation.19 In this study, it was suggested that DAG or PUFA accumulation, due to the rdgA mutation, is responsible for the observed constitutive activity. Several studies conducted in both photoreceptor cells and in expression systems have supported the notion that DAG has an excitatory effect on TRPL channels, by showing that DAG analogs increase TRPL channel activity.2,20,24 However, neither a relevant DAG-lipase protein converting DAG into PUFA in the fly signaling compartment, nor sites on the channels surface, which bind these lipids were found.25 It is, therefore, still unclear what the exact role that these lipids have on the gating mechanism of the TRPL channel.

The possible gating mechanisms that involve PtdIns(4,5)P2 have been extensively investigated both in the native photoreceptors and heterologous expression systems. An early study performed in Drosophila photoreceptors has shown that PtdIns(4,5)P2 serves as a substrate for the activation process.26 Two studies have suggested that PtdIns(4,5)P2 functions as an inhibitor of the TRPL channel in heterologous expression systems. These studies showed that PtdIns(4,5)P2 sequestration by exogenous polylysine or PtdIns(4,5)P2 addition enhanced or suppressed the activity of constitutively active TRPL channels, respectively.2,20 These results are not consistent with recent data showing that PtdIns(4,5)P2 addition to excised patches of S2 cells expressing TRPL facilitated channel activity. This same study further showed that PtdIns(4,5)P2 reduction together with intracellular acidification led to robust opening of the channels in the native system. However, in the S2 expression system, facilitated opening of the same channel could be achieved merely by intracellular acidification.22 Collectively, these results indicate a crucial role for PtdIns(4,5)P2 in TRPL gating, although the underlying mechanism is not clear.

In the present study, we show that the Drosophila TRPL channel expressed in tissue cultured cells is constitutively active in S2 cells but is silent in HEK cells, where it becomes active upon stimulation. PLC activation and PUFA application enhanced channel opening in all expression systems. However, application of DAG-lipase inhibitor (RHC-80267), cellular acidification and PtdIns(4,5)P2 manipulations, using specific enzymes, resulted in conflicting effects, depending on the expression system used. These conflicting results lead to very different interpretations of DAG and PtdIns(4,5)P2 role in TRPL gating.

Results

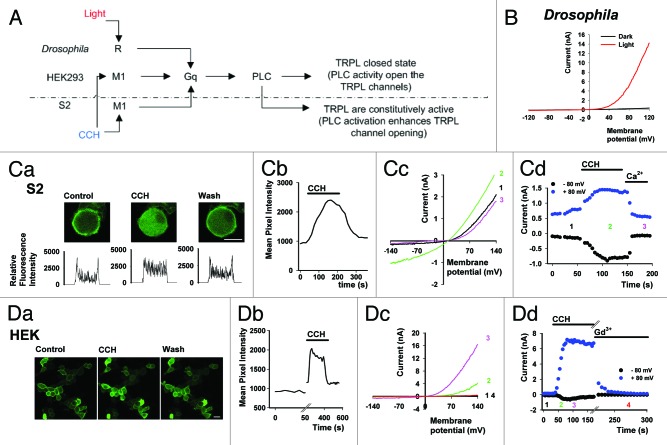

In an attempt to decipher the gating mechanism of TRP channels, TRPL channels were heterologously expressed in tissue cultured S2 cells20 and HEK cells.27 When expressed in the Drosophila S2 cells, TRPL shows a basal constitutive activity that could be further enhanced by activation of the muscarinic (M1) receptor with carbachol (CCH, Fig. 1A and C). Interestingly, when expressed in mammalian HEK cells, the TRPL channels did not show basal activity, but could be activated via the M1 receptor (Fig. 1A and D). The latter result is similar to that observed in photoreceptor cells in vivo, whereby the TRPL channels are closed in the dark while, light stimulation activates the channels via a PLC-mediated GPCR cascade (Fig. 1A and B).

Figure 1. GPCR mediated PLC activation of TRPL in Drosophila photoreceptor, S2 and HEK cells. (A) Scheme of GPCR dependent PLC activation and facilitation of TRPL channels in Drosophila photoreceptors, HEK and S2 cells. (B)Whole cell patch clamp recordings from Drosophila photoreceptors of the trpP343 mutant (expressing only the TRPL channels). I-V curves obtained using voltage ramps at total darkness (black), and during intense light (red). (C, part a) A representative series of confocal images of S2 cells co-expressing eGFP-tagged PH domain, TRPL channels, and M1 receptor. Application of carbachol (CCH, 100 µM) to the bathing solution resulted in the movement of the eGFP-tagged PH domain to the cell body, indicating the activation of PLC and hydrolysis of PI(4,5)P2. Note that washout of CCH from the bathing solution results in reversible marking of the plasma membrane with eGFP-tagged PH domain (scale 10 μm). Bottom: Cross section, line profiles of the fluorescence intensity are given below. (C, part b) A time course of the fluorescence change measured in the cytosol following CCH application (n = 10). (C, part c) Selected I-V curves before CCH (black), after CCH (green) and after addition of extracellular solution with 1.5 mM Ca2+ (magenta) which blocks the TRPL channels by an open channels block mechanism.5 (C, part d) Corresponding currents at +80 and -80 mV. Numbers depict the selected I-V curves (n = 5). (D, part a) A representative series of confocal images from HEK cells co-expressing eGFP-tagged PH domain, TRPL channels, and M1 receptor. Application of CCH (100 µM) to the bathing solution induced movement of the eGFP-tagged PH domain to the cell body in a calcium dependent manner, indicating the activation of PLC and hydrolysis of PI(4,5)P2. Subsequent wash of CCH from the bathing solution resulted in reversible marking of the plasma membrane with eGFP-tagged PH domain (scale 20 μm). (D, part b) A time course of the fluorescence change measured in the cytosol following CCH application from a single cell in the field of view (n = 5). (D, part c) Selected I-V curves before CCH application (black), after CCH (green, magenta) and after addition of extracellular solution with 1mM Gd3+ (red) which blocks the TRPL channels.8 (D, part d) Corresponding currents at +80 and -80 mV. Numbers depict the selected I-V curves (n = 9). No effect was observed when CCH was applied to S2 and HEK cells expressing TRPL channels without the M1 receptor.

Do PUFAs act as second messengers?

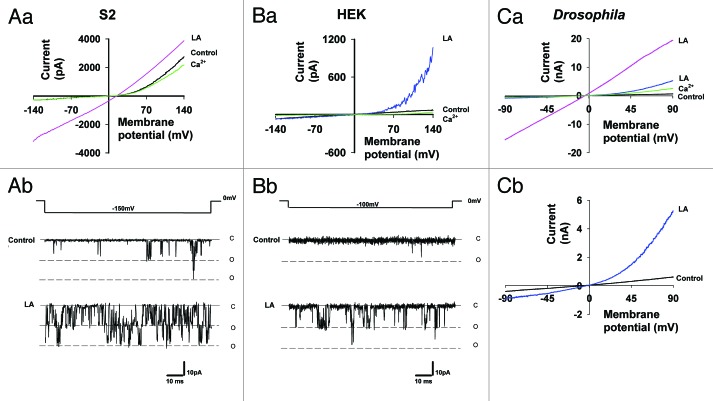

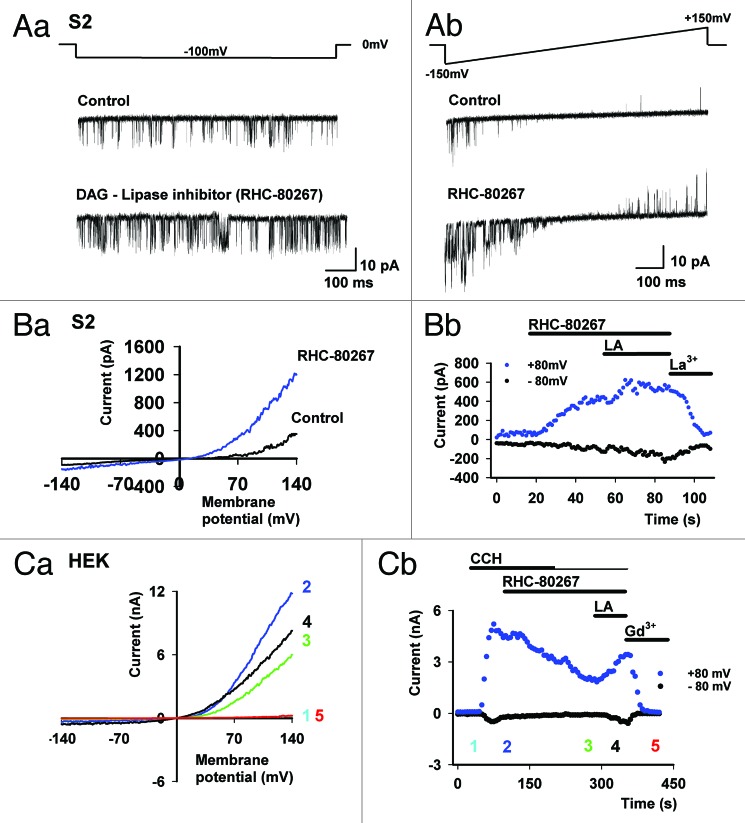

PUFAs (e.g., linoleic acid) are potent activators of the TRPL channels in all expression systems tested, including S2 cells (see Fig. 2A),20 HEK cells (see Fig. 2B)27 and photoreceptor cells (see Fig. 2C).4 These observations have led to the proposal that DAG production by PLC, followed by PUFA formation via DAG lipase promotes channel activation. According to this mechanism, PUFAs act as second messengers and gate the TRP channels.28 The results of Figure 3 show that the above scenario is too simple to account for all experimental observations. Accordingly, TRPL expressed in HEK cells revealed that activation of the channel, followed by application of the DAG lipase inhibitor (RHC-80267) led to TRPL current suppression, as expected from a reduction in the production of a putative PUFA second messenger (Fig. 3C). This conclusion was supported by exogenous application of a PUFA (linoleic acid, LA Fig. 3C) which, facilitated channel activity. In contrast, application of the DAG lipase inhibitor to TRPL expressed in S2 cells led to the opposite result, as manifested in both single channel recordings (Fig. 3A) and whole cell recordings (Fig. 3B). Figure 3 shows that TRPL channel activity was enhanced by RHC-80267 and LA had an additional small but detectible effect, which further facilitated TRPL channel activity (Fig. 3A and B). A possible explanation of these results is that RHC-80267 application followed by DAG accumulation leads to TRPL channel activation. However, direct application of DAG analogs in HEK cells did not activate the TRPL channels.27 Moreover, both DAG accumulation and LA were shown to facilitate TRPL channel activity in the Drosophila S2 expression system.

Figure 2. Linoleic Acid (LA) activation and facilitation of TRPL in S2, HEK and Drosophila photoreceptor cells. (A, part a) Representative I-V curves of TRPL activity in whole-cell recordings mode, when expressed in S2 cells. Note that the basal TRPL activity can be further enhanced by application of LA (60 µM) up to linearization. Addition of extracellular solution with 1.5 mM Ca2+ (green) blocks the TRPL channels by an open channels block mechanism5 (n = 10). (A, part b) Single channel activity in cell attached mode before (control) and after application of LA. (B, part a) Representative I-V curves of TRPL activity in whole cell recordings mode, when expressed in HEK cells. Note the absence of channel activity before LA application. Addition of extracellular solution with 1.5 mM Ca2+ (green) after channel activation by LA blocks the TRPL channels (n = 10). (B, part b) Single channel activity in cell attached mode before (control) and after application of LA. (C, part a) Representative I-V curves of trpP343 mutant fly of Drosophila photoreceptors in whole-cell recording mode. Note that in total darkness no basal TRPL activity is observed, while application of LA enhances TRPL activity up to linearity. Addition of extracellular solution with 10mM Ca2+ (green) blocks the TRPL channels by an open channels block mechanism5 (n = 5). (C, part b) A magnification of the I-V curves of (C, part a). No effect was observed when LA was applied to S2 and HEK cells without expression of TRPL.

Figure 3. Application of a DAG-Lipase inhibitor (RHC-80267) facilitates TRPL channel activity in S2 but inhibits TRPL activity in HEK cells. (A, part a) Single channel measurements in cell-attached mode of TRPL channel expressed in S2 cells. Constitutive activity of TRPL channel is observed, while addition of DAG-Lipase inhibitor RHC-80267 (100 µM) facilitates the single channel activity (Bottom). (A, part b) Similar experiment as in (A, part a) except that single channel activity was measured during voltage ramp of +/− 150 mV. Note the facilitation of channel activity also at negative membrane potentials after application of RHC-80267 (n = 7). (B, part a) Representative I-V curves recorded in S2 cells, showing facilitation of the constitutive TRPL activity after application of DAG-Lipase inhibitor. (B, part b) Corresponding currents at +80 and -80 mV as a function of time. Addition of extracellular solution with 1 mM La3+ blocks the TRPL channels5 (n = 3). (C, part a) Representative I-V curves in HEK cells, showing the inhibition of the CCH dependent TRPL activity after application of the DAG-Lipase inhibitor. (C, part b) Corresponding currents at +80 and -80 mV as a function of time. Addition of extracellular solution with 1mM Gd3+ blocks the TRPL channels8 (n = 4, maximal current reduction following RHC-80267 application: 67.3 ± 10%, Mean ± S.E.M). No effect was observed when RHC-80267 was applied to HEK cells without expression of M1 receptor.

Does PtdIns(4,5)P2 function as an inhibitor of the channels?

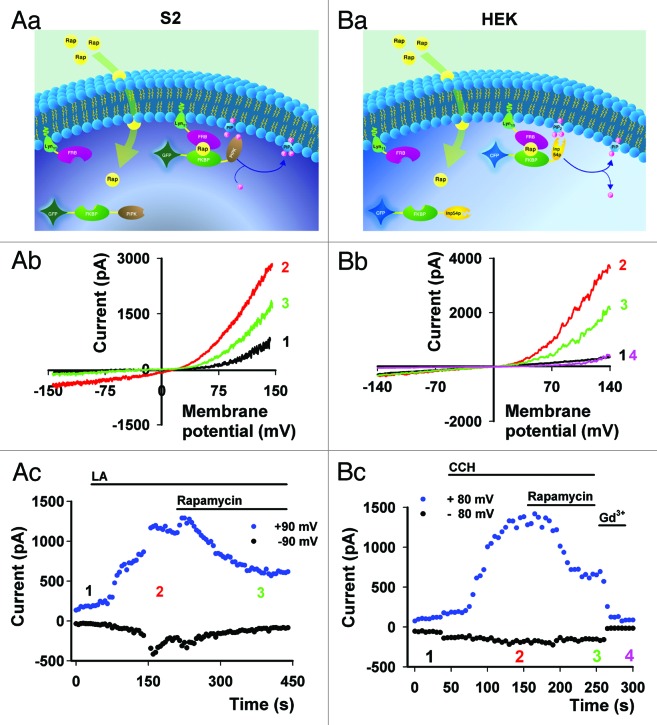

To test this model directly, the modulation of PtdIns(4,5)P2 was attempted by using the Inp54p phosphatase system in HEK cells (Fig. 4B). The great advantage of this system is that hydrolysis of PtdIns(4,5)P2 is not accompanied by accumulation of the PLC products Ins(1,4,5)P3 and DAG. These PLC products are known to affect many downstream signals.

Figure 4. Modulation of TRPL channel activity by PI(4,5)P2 in S2 and HEK cells. Reduction or elevation of PI(4,5)P2 levels by the Rapamycin system.29 PI(4,5)P2 hydrolysis or production is obtained by translocation of yeast Inp54p (a PI(4,5)P2 specific phosphatase) or PIPK (a PI(4)P specific kinase) to the plasma membrane, respectively. Accordingly, Rapamycin (a heterodimerization agent) dimerizes the FKBP part of FK506, conjugated to the Inp54p phosphatase or PIPK, to a membrane anchor possessing the FRB part of mTOR. The dimerization induces translocation of the enzymes to the plasma membrane where the substrates are located. (A, part a) Scheme describing Rapamycin inducible system, which activates PIPK at the plasma membrane and subsequently increases PI(4,5)P2 levels in S2 expression system. (A, part b)Selected I-V curves of TRPL activity in S2 cells at basal level (black), after application of 60 µM LA (red) and after 500 nM Rapamycin inducing kinase activity (green). (A, part c) The currents values at +90 and -90 mV are shown as a function of time (n = 3). (B, part a) Scheme describing Rapamycin inducible system, which activates PI phosphatase at the plasma membrane and subsequently decreases PI(4,5)P2 levels in the HEK expression system. (B, part b) Selected I-V curves of TRPL activity in HEK cells before (black) and after CCH application (red) and after 500 nM Rapamycin inducing phosphatase activity (green). Further addition of 1 mM Gd3+ blocks channel activity (magenta)8 (B, part c) The current values at +80 and -80 mV are shown as a function of time (n = 5, Maximal current reduction following Rapamycin application: 56 ± 8.3%, Mean ± S.E.M). No effect of Rapamycin application to S2 or HEK cells was observed when only TRPL channels were expressed or when one component of the mTOR Rapamycin system was missing.

The Inp54p phosphatase (Fig. 4B) or PI(4)P kinase (Fig. 4A) rapamycin system29 were used to show that modulation of PtdIns(4,5)P2 leads to conflicting results. Accordingly, PtdIns(4,5)P2 hydrolysis induced by application of Rapamycin to HEK cells, (expressing the Inp54p phosphatase system and TRPL, Figure 4B) caused suppression of CCH-activated TRPL channel (Fig. 4B). In contrast, PtdIns(4,5)P2 synthesis induced by application of Rapamycin to S2 cells, (co-expressing the PI(4)P kinase and TRPL, Figure 4A) caused suppression of LA activated TRPL channel activity (Fig. 4A), consistent with previous experiments attributing an inhibitory role to PtdIns(4,5)P2.2,20 The data thus show that PtdIns(4,5)P2 hydrolysis in HEK cells and PtdIns(4,5)P2 synthesis in S2 cells both suppressed TRPL channel activity, a result which demonstrates that the interpretation of PtdIns(4,5)P2 role in TRPL activation is expression system dependent (see also studies on mammalian TRPC channels30).

A revised version of the PtdIns(4,5)P2 depletion hypothesis was suggested. According to this hypothesis, PtdIns(4,5)P2 depletion together with intracellular acidification are required for TRP and TRPL channel gating in the photoreceptor cells.22 However, this hypothesis, which was based on experiments conducted in Drosophila photoreceptors and S2 cells, was not supported by experiments conducted in HEK cells.27 Furthermore, in the S2 expression system, intracellular acidification alone without PtdIns(4,5)P2 depletion was sufficient to facilitate TRPL channel opening. This particular result could not be demonstrated in the HEK expression system as intracellular acidification did not open the channels.27 These results exemplify the complexity of formulating a coherent model of TRPL channel gating.

The third model, in which conversion of PtdIns(4,5)P2 into DAG modifies membrane lipid packing and affects channel-plasma membrane lipids interactions, fits with the results obtained from TRPL expressed in S2 cells.5 This is because many membrane modulations (DAG, PUFA, PtdIns(4,5)P2 depletion, changes of osmolarity) affected the activation state of TRPL channels in this system.20 However, several of these results could not be reproduced for TRPL channels expressed in HEK cells, and therefore, the results obtained in this system fit a different model. Moreover, data on lipid channel interaction and effects of changes in lipid packing on channel activity are still missing.

Discussion

Channels expressed in tissue culture cells are useful as native systems usually express more than one channel and channel accessibility can be challenging. Pharmacology has played a major role in isolating the current of a specific channel in native systems. Nevertheless, pharmacology has a disadvantage of targeting and specificity. The advances in molecular biology and tissue cultured cells have been instrumental in overcoming some of these difficulties. Currently, cloned channels expressed in tissue culture cells enable electrophysiological characterization of specific channels in isolation. The drawback of this methodology is that sometimes the normal channel activity requires essential components of the native system. This in turn results in abnormal channel properties. In some cases, overexpression of a channel, or absence of necessary channel subunits cause abnormal physiological behavior of the channel. In other cases, the cellular environment of the expression systems modifies the normal channel activity.

In the S2 expression system, the characteristics of the TRPL channel are best explained by assuming plasma membrane-channel interactions.5 This is because many membrane modulations [by DAG, PUFA, PtdIns(4,5)P2 depletion, changes of osmolarity] affected the activation state of TRPL channels expressed in S2. On the other hand, in the HEK expression system, the characteristics of the TRPL channel fit better a PUFA-based second messenger model.27 This is mainly because PtdIns(4,5)P2 solely acts as a PLC substrate necessary for TRPL activation, while PUFA activates the channel directly.

In the present study we demonstrated the difficulties in elucidating the gating mechanism of the TRPL channel. We showed that pharmacological or membrane lipid modulations by specific enzymes resulted in conflicting results, depending on the expression system used. These observations raise the questions as to the validity of using such expression systems as models of native systems. We suggest that elucidating the factors, which affect TRPL state of activation in different expression systems, are likely to shed light on the gating mechanism of these channels.

Material and Methods

Fly stock

Drosophila White-eyed trpP343 mutant fly was used. Flies were raised at 24°C in a 12 h light/dark cycle on standard medium.

Light stimulation

A xenon high-pressure lamp (PTI, LPS 220, operating at 50 W) was used and the light stimuli were delivered to the ommatidia by means of epi-illumination via an objective lens (in situ). The intensity of the orange light (Schott OG 590 edge filter) at the specimen, with no intervening neutral density filters, was 13 mW/ cm2 and it was attenuated by neutral density filters in log scale.

Expression Constructs

For S2 cells: The Drosophila TRPL channel was expressed using pRmHa3-TRPL plasmid. The Drosophila Muscarinic receptor was expressed using pRmHa3-DM1 plasmid. The GFP-FKBP-PIPK, Lyn11-FRB and GFP-PLCdelta-PH were subcloned into pMT expression vector. For HEK cells: The mouse Muscarinic receptor M1-CFP was expressed using pCD-PS mammalian expression vector. The Drosophila TRPL ORF was subcloned into pEGFP-C1 expression vector between the NheI and EcoRI restriction sites. The Lyn11-FRB, CFP-FKBP-Inp54p and GFP-PLCdelta-PH used are as previously described.29

Cell Culture

Schneider S2 cells were grown in 25 cm2 flasks, at 25°C in Schneider medium (Beit Haemek Biological Industries) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% pen-strep. Transfections were performed using Escort IV (Sigma) with equal amounts of cDNA, according to the manufacturer’s instructions and protocol. A S2 line stably expressing TRPL was used for many experiments in which CuSO4 at a final concentration of 500 µM was added 24 h before experiment to induce expression.

HEK cells were grown at 37°C with 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% pen-strep (Biological Industries). Transfections were performed with the TransIt (Mirus) transfection reagent, with equal amounts of cDNA, according to the manufacturer’s instructions and protocol.

Electrophysiology

HEK cells were seeded on polylysine coated coverslips at a confluence of 25%. 24–48 h before the experiment, cells were transfected to induce expression of the appropriate proteins. S2 cells were seeded on polylysine coated plates at a confluence of 25%, 48–72 h before the experiment. 24–48 h before the experiment, cells were transfected and 500 µM CuSO4 (final concentration) was added to the medium to induce expression of the channels. Single channel and whole-cell currents were recorded at room temperature using borosilicate patch pipettes of 3–5 MΩ for HEK and 7–10 MΩ for S2 cell and an Axopatch 200B voltage-clamp amplifier. Voltage-clamp pulses were generated, and data were captured using a Digidata 1440A interfaced to a computer running the pClamp 10 software (Molecular Devices). Currents were filtered using 8-pole low pass Bessel filter at 5 kHz and sampled at 50 kHz. Series resistance compensation was performed 80% for currents above 1000 pA for HEK. For Drosophila ommatidia, Axopatch 1D voltage-clamp amplifier, Digidata 1200 and pClamp 8.0 software (Molecular Devices) were used. Currents were filtered at 5 kHz using the 8-pole low pass Bessel filter and sampled at 20 kHz. To measure current–voltage (I–V) curves with minimal distortions, only cells with low (~10 MΩ) series resistance were used and the series resistance was compensated by 80%.

Solutions

For Drosophila ommatidia, the extracellular solution contained the following (in mM): 120 NaCl, 5 KCl, 4 MgSO4, 10 TES, 25 proline, 5 alanine. To this nominal Ca2+ based solution either 0.5 mM EGTA or 10 mM CaCl2 were added. The intracellular solution, contained (in mM): 120 CsCl, 10 TES, 2 MgSO4, 4 Mg-ATP, 0.4 Na-GTP, 1 β-NAD and 15 TEA. All solutions were titrated to pH 7.15. For HEK cells, the extracellular solution contained (in mM):145 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 15 HEPES, 10 glucose and titrated to pH 7.4. To this nominal Ca2+ based solution either 0.5 mM EGTA or 1.5 mM CaCl2 were added. In order to block the TRPL channel 1mM of GdCl3 was added to the extracellular solution. The intracellular pipette solution contained (in mM):130 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 2 Na2ATP, 4.1 CaCl2 and titrated to pH 7.2. For S2 cells, the extracellular solution contained (in mM): 150 NaCl, 5 KCl, 4 MgCl2, 10 TES, 25 proline, 5 alanine, and 0.5 EGTA. In order to block the TRPL channel 1mM of LaCl3 was used to the extracellular solution. The intracellular pipette solution contained (in mM): 130 K-gluconate, 10 TES, 2 MgCl2, 4 Mg-ATP and 0.4 Na-GTP, 0.5 BAPTA. All solutions were titrated to pH 7.15.

All cells were perfused via BPS-4 valve control system (Scientific Instruments) at a rate of ~30 chamber volumes/min. Rapamycin (500 nM), LA (60 µM) and carbachol (CCH 100 µM) were purchased from Calbiochem.

Confocal Imaging

Images of HEK and S2 cells expressing fluorescent proteins were acquired in a confocal microscope (Olympus Fluoview 300 IX70) using an Olympus UplanF1 60X /0.9 water objective. The cells were excited with an argon/krypton laser at 488 nm.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed and plotted using pClamp 10 (Molecular Devices) and Sigma Plot 8.02 (Systat software) software. Confocal images were imported as tiff single images into Photoshop (Adobe Systems Inc.), where they were subsequently cropped and resized.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Neil S. Millar for providing the TRPL and Dm1 constructs, Dr. Neil M. Nathanson for providing muscarinic receptor fused to cyan fluorescent protein at its C terminus, Dr. Armin Huber for providing the S2 stable line expressing TRPL-eGFP, Dr. Sharona E. Gordon for providing the GFP-PLCdelta-PH and Dr. Tobias Meyer for providing all vectors used in the rapamycin system (Lyn11-FRB, CFP-FKBP-Inp54p and PIPK). We also thank Maximilian Peters for useful suggestions and critical reading of the manuscript. This research was supported by grants from the National Eye Institute (NEI, R01 EY 03529), the US-Israel Bi-National Science Foundation (BSF) the Israel Science Foundation (ISF) and the German Israeli Foundation (GIF).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally to this work

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/channels/article/19946

References

- 1.Phillips AM, Bull A, Kelly LE. Identification of a Drosophila gene encoding a calmodulin-binding protein with homology to the trp phototransduction gene. Neuron. 1992;8:631–42. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90085-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Estacion M, Sinkins WG, Schilling WP. Regulation of Drosophila transient receptor potential-like (TrpL) channels by phospholipase C-dependent mechanisms. J Physiol. 2001;530:1–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0001m.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harteneck C, Obukhov AG, Zobel A, Kalkbrenner F, Schultz G. The Drosophila cation channel trpl expressed in insect Sf9 cells is stimulated by agonists of G-protein-coupled receptors. FEBS Lett. 1995;358:297–300. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01455-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chyb S, Raghu P, Hardie RC. Polyunsaturated fatty acids activate the Drosophila light-sensitive channels TRP and TRPL. Nature. 1999;397:255–9. doi: 10.1038/16703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parnas M, Katz B, Minke B. Open channel block by Ca2+ underlies the voltage dependence of drosophila TRPL channel. J Gen Physiol. 2007;129:17–28. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hambrecht J, Zimmer S, Flockerzi V, Cavalié A. Single-channel currents through transient-receptor-potential-like (TRPL) channels. Pflugers Arch. 2000;440:418–26. doi: 10.1007/s004240000301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu XZS, Li HS, Guggino WB, Montell C. Coassembly of TRP and TRPL produces a distinct store-operated conductance. Cell. 1997;89:1155–64. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80302-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lev S, Katz B, Tzarfaty V, Minke B. Signal-dependent hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate without activation of phospholipase C: implications on gating of Drosophila TRPL (transient receptor potential-like) channel. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:1436–47. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.266585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hardie RC, Minke B. The trp gene is essential for a light-activated Ca2+ channel in Drosophila photoreceptors. Neuron. 1992;8:643–51. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90086-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devary O, Heichal O, Blumenfeld A, Cassel D, Suss E, Barash S, et al. Coupling of photoexcited rhodopsin to inositol phospholipid hydrolysis in fly photoreceptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:6939–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.19.6939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niemeyer BA, Suzuki E, Scott K, Jalink K, Zuker CS. The Drosophila light-activated conductance is composed of the two channels TRP and TRPL. Cell. 1996;85:651–9. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bloomquist BT, Shortridge RD, Schneuwly S, Perdew M, Montell C, Steller H, et al. Isolation of a putative phospholipase C gene of Drosophila, norpA, and its role in phototransduction. Cell. 1988;54:723–33. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(88)80017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Damann N, Voets T, Nilius B. TRPs in our senses. Curr Biol. 2008;18:R880–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Julius D, Nathans J. Signaling by sensory receptors. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4:a005991. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katz B, Minke B. Drosophila photoreceptors and signaling mechanisms. Front Cell Neurosci. 2009;3:2. doi: 10.3389/neuro.03.002.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agam K, von Campenhausen M, Levy S, Ben-Ami HC, Cook B, Kirschfeld K, et al. Metabolic stress reversibly activates the Drosophila light-sensitive channels TRP and TRPL in vivo. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5748–55. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-15-05748.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Minke B, Selinger Z. Inositol lipid pathway in fly photoreceptors: excitation, calcium mobilization and retinal degeneration. In: Osborne NA, Chader GJ, eds. Progress in retinal research: Pergamon Press Oxford, 1991:99-124. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agam K, Frechter S, Minke B. Activation of the Drosophila TRP and TRPL channels requires both Ca2+ and protein dephosphorylation. Cell Calcium. 2004;35:87–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raghu P, Usher K, Jonas S, Chyb S, Polyanovsky A, Hardie RC. Constitutive activity of the light-sensitive channels TRP and TRPL in the Drosophila diacylglycerol kinase mutant, rdgA. Neuron. 2000;26:169–79. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81147-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parnas M, Katz B, Lev S, Tzarfaty V, Dadon D, Gordon-Shaag A, et al. Membrane lipid modulations remove divalent open channel block from TRP-like and NMDA channels. J Neurosci. 2009;29:2371–83. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4280-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hardie RC, Postma M. Phototransduction in Microvillar Photoreceptors of Drosophila and Other Invertebrates. In: Allan IB, Akimichi K, Gordon MS, Gerald W, Thomas DA, Richard HM, et al., eds. The Senses: A Comprehensive Reference. New York: Academic Press, 2008:77-130. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang J, Liu CH, Hughes SA, Postma M, Schwiening CJ, Hardie RC. Activation of TRP channels by protons and phosphoinositide depletion in Drosophila photoreceptors. Curr Biol. 2010;20:189–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang T, Montell C. A phosphoinositide synthase required for a sustained light response. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12816–25. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3673-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Delgado R, Bacigalupo J. Unitary recordings of TRP and TRPL channels from isolated Drosophila retinal photoreceptor rhabdomeres: activation by light and lipids. J Neurophysiol. 2009;101:2372–9. doi: 10.1152/jn.90578.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leung HT, Tseng-Crank J, Kim E, Mahapatra C, Shino S, Zhou Y, et al. DAG lipase activity is necessary for TRP channel regulation in Drosophila photoreceptors. Neuron. 2008;58:884–96. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu L, Niemeyer B, Colley N, Socolich M, Zuker CS. Regulation of PLC-mediated signalling in vivo by CDP-diacylglycerol synthase. Nature. 1995;373:216–22. doi: 10.1038/373216a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lev S, Katz B, Tzarfaty V, Minke B. Signal-dependent hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate without activation of phospholipase C: implications on gating of Drosophila TRPL (transient receptor potential-like) channel. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:1436–47. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.266585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hardie RC. Regulation of TRP channels via lipid second messengers. Annu Rev Physiol. 2003;65:735–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suh BC, Inoue T, Meyer T, Hille B. Rapid chemically induced changes of PtdIns(4,5)P2 gate KCNQ ion channels. Science. 2006;314:1454–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1131163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trebak M, Lemonnier L, DeHaven WI, Wedel BJ, Bird GS, Putney JW., Jr. Complex functions of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate in regulation of TRPC5 cation channels. Pflugers Arch. 2009;457:757–69. doi: 10.1007/s00424-008-0550-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]