Abstract

The role of Shigella-specific B memory (BM) in protection has not been evaluated in human challenge studies. We utilized cryopreserved pre- and post-challenge peripheral blood mononuclear cells and sera from wild-type Shigella flexneri 2a (wt-2457T) challenges. Challenged volunteers were either naïve or subjects who had previously ingested wt-2457T or been immunized with hybrid Escherichia coli-Shigella live oral candidate vaccine (EcSf2a-2). BM and antibody titers were measured against lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and recombinant invasion plasmid antigen B (IpaB); results were correlated with disease severity following challenge. Pre-challenge IgA IpaB-BM and post-challenge IgA LPS-BM in the previously exposed subjects negatively correlated with disease severity upon challenge. Similar results were observed with pre-challenge IgG anti-LPS and anti-IpaB titers in vaccinated volunteers. Inverse correlations between magnitude of pre-challenge IgG antibodies to LPS and IpaB, as well as IgA IpaB-BM and post-challenge IgA LPS-BM with disease severity suggest a role for antigen-specific BM in protection.

Keywords: Shigella, protection, human challenge, B memory, LPS, IpaB

1. Introduction

Shigella is an important cause of morbidity and mortality from diarrheal diseases among children living in developing countries [1, 2]. The control of shigellosis is impeded by the emergence of antibiotic resistance [3] and lack of a commercially available vaccine. Obstacles in Shigella vaccine development include the lack of adequate animal challenge models that faithfully reproduce human shigellosis and the complexity of performing human challenge studies or prospective clinical studies in the field [4]. Challenge studies offer a means of studying protective immunity in humans. Three challenge studies were performed at the University of Maryland School of Medicine Center for Vaccine Development (CVD) in the early 1990’s to evaluate the efficacy of a live oral hybrid Escherichia coli-Shigella flexneri 2a vaccine candidate (EcSf2a-2) developed at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research [5] and to refine the wild-type challenge model. Efficacy was assessed by measuring the ability of either the vaccine or wild-type infection to prevent illness following experimental challenge with wild-type S. flexneri 2a strain 2457T (wt-2457T) [6, 7]. In two studies, volunteers were administered multiple spaced doses of EcSf2a-2 and challenged one month later (along with a group of unvaccinated controls) with wt-2457T. The vaccine induced a modest immune response and conferred 27–36% efficacy against challenge [7]. A subset of these volunteers who developed gastrointestinal symptoms of shigellosis (diarrhea or dysentery) after challenge with virulent S. flexneri 2a in bicarbonate buffer agreed to participate in a second challenge study with wt-2457T along with a group of subjects who had not been previously immunized or challenged; the protective efficacy of prior exposure to wt-2457T reached 70% [6]. Based on these studies, IgA anti-LPS antibody secreting cell (ASC) responses have been proposed as a possible correlate of protection [7]. Heretofore, very limited additional putative immune markers, notably IgG serum antibody titers against lipopolysaccharide (LPS) have been found in most, but not all, studies to be statistically correlated with protection against Shigella infection [4, 8–11]. Other immune mechanisms that have been proposed to correlate with protection against shigellosis include serum antibody responses against invasion plasmid antigens (Ipa) [4, 6, 11–13] and cell mediated immunity (CMI) [4, 14–16]. However, there is no definitive evidence that these responses by themselves can be considered mechanistic mediators of protection [4]. Therefore, it is important to search for additional correlates of protection that alone or in combination can be used to predict the efficacy of candidate Shigella vaccines.

The appearance of ASC ~7 days after immunization suggests immune priming that may also be accompanied by the generation of B memory (BM) cells. BM cells are responsible for mounting a rapid anamnestic antibody response (recall response) upon re-exposure to microbial antigens and thus are considered an indicator of long-term protection induced by vaccine- or natural infection [17, 18]. Methodological advances and the availability of purified antigens (including recombinant IpaB) now enable the measurement of BM cells in cryopreserved peripheral mononuclear cell (PBMC) specimens elicited by orally administered attenuated enteric vaccines or other vaccine candidates. Using this approach we have recently demonstrated the presence of BM cells in subjects immunized with attenuated strains of Shigella, S. Typhi, S. Paratyphi A, S. Paratyphi B and Norovirus [19–23]. Cryopreserved specimens from Shigella challenge studies performed in the 1990s offered a unique opportunity to identify potential immune correlates that could not be identified at that time because the technology was not available. Thus, we utilized the limited specimens remaining from those studies to measure BM cells as well as serum antibodies in specimens collected before and after challenge, and correlated these responses with disease outcome. Our goal was to investigate correlations among pre- and post-challenge LPS- and IpaB-specific BM and serum antibodies, as well as antibody secreting cells (ASC) with disease outcome to better define the role of specific immune responses in protection.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design

We analyzed available PBMC specimens cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen and serum cryopreserved at −70°C from the three clinical trials involving subjects challenged with wt-2457T described in the introduction. All available PBMC specimens from 20 volunteers challenged with wt-2457T were used for BM cell assays; 13 had prior exposure to S. flexneri 2a (pre-exposed group) through vaccination or experimental challenge and the remaining 7 were newly recruited healthy controls (naïve group) who had no history of prior exposure to S. flexneri 2a. Following thawing, an average 76% of the originally cryopreserved PBMC/vial were recovered with an average cell viability of 82% as determined by trypan blue exclusion.

PBMC were available from a pre-exposed group, comprised of three volunteers who had been previously challenged with wt-2457T (no immunizations, referred to as “veterans” in previous publications; [6, 7]), and ten subjects who had been previously immunized with 4 doses of EcSf2a-2 (7x108 CFU). Serum samples were available from fifteen vaccinated volunteers previously immunized with 4 doses of EcSf2a-2 (7x108 CFU). Samples from naïve controls (PBMC: n=7 and serum: n=14) were also available from the same study [7]. These control subjects were healthy volunteers with no history of previous exposure to WT-2457T or EcSf2a-2. All volunteers (including the naïve subjects) were challenged with wt-2457T and samples (PBMC and sera) used in the current study were collected before (day 0) and after (day 28 days) following challenge. Informed, written consent was obtained from participants prior to enrollment in the clinical trials according to the guidelines of the Institutional Review Board of the University of Maryland.

2.2. Disease Index

The design of the inpatient challenge studies is described elsewhere [6, 7]. A categorical outcome-based disease index was created prior to analysis based on body temperature, daily number of bloody stools, daily number of loose stools, and total daily volume of the loose stools. The disease index assigned to each subject is the average grade of all components shown in Table 1. A dichotomous clinical outcome categorization (ill or well) was the one originally described for these clinical challenge studies (objective illness was defined on the basis of fever, diarrhea or dysentery) [6, 7]. The disease index was created for this study to explore the possibility that a categorical variable will define more precisely the severity of the clinical outcome than a dichotomous one, offering a better opportunity to correlate clinical and immunological measurements. When we compared the two methods, of those subjects who were protected or “well” (n=7) according to the previous criteria, all but one (who was graded as grade 1) were graded as 0, in our new disease index (n=6). Those who were previously categorized as “ill” (n=13), were further subdivided into grades (grade 1–3) based on disease severity.

Table 1.

Disease index definitions

| Stool |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease index |

llness | Body Temp (°C) |

Bloody (times/day) |

Loose (times/day) |

Vol. (mL) (total/day) |

| 0 | None | 37.0–37.9 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| 1 | Mild | 38.0–38.9 | 1–2 | 1–2 | <500 |

| 2 | Moderate | 39.0–40.0 | 3–10 | 3–10 | 500–2000 |

| 3 | Severe | >40 | >10 | >10 | >2000 |

2.3. Antigens

The LPS from S. flexneri 2a LPS was purified by the hot aqueous phenol extraction method of Westphal [24] and the Shigella IpaB and Yersinia pestis LcrV (the negative control protein) antigens were purified as recombinant proteins expressed in E. coli as previously described in detail [20].

2.4. BM assay

BM responses were measured using an optimized dual color ELISpot assay for the simultaneous measurement of IgG and IgA spot forming cells (SFC). Briefly, PBMC were thawed, expanded and seeded in duplicate wells of plates coated with Shigella antigens or total IgG or IgA as previously described [20, 25]. Plates were then incubated with antihuman IgG-alkaline phosphatase and IgA-horseradish peroxidase (Jackson ImmunResearch, PA). IgA SFC were visualized with nitro-blue tetrazolium chloride (NBT) substrate (Vector laboratories, CA) as blue spots and, after washing, plates were incubated with 3-Amino-9-ethylcarbazole (AEC) substrate (Calbiochem, MA) to visualize IgG SFC as red spots. SFC were enumerated using an automated ELISPOT reader (Immunospot 3B, Cellular Technologies Ltd,OH) with aid of the Immunospot software version 5.0 (Cellular Technologies Ltd). Total and antigen-specific BM SFC were calculated as SFC/106 cells. Isotype-specific frequencies of BM against specific antigens are expressed as the percentages of specific BM per total IgA or IgG (specific BM SFC per 106/total Ig SFC per 106×100).

2.5. Antibody measurements

ELISA was used to measure serum antibody against Shigella antigens as previously described [20]. End-point titers were reported as the inverse of the serum dilution that produced an OD of >0.2 above the blank.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Microsoft® Office Excel 2007 and GraphPad Prism 5.0 were used for statistical analysis. Hypotheses were evaluated using non-parametric two-sided tests. Correlations between immune response and disease indices were assessed using Spearman rho. The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to assess continuous pre- to post-challenge antigen-specific immune responses.

3. Results

3.1. Correlations between LPS and IpaB-specific BM with disease severity

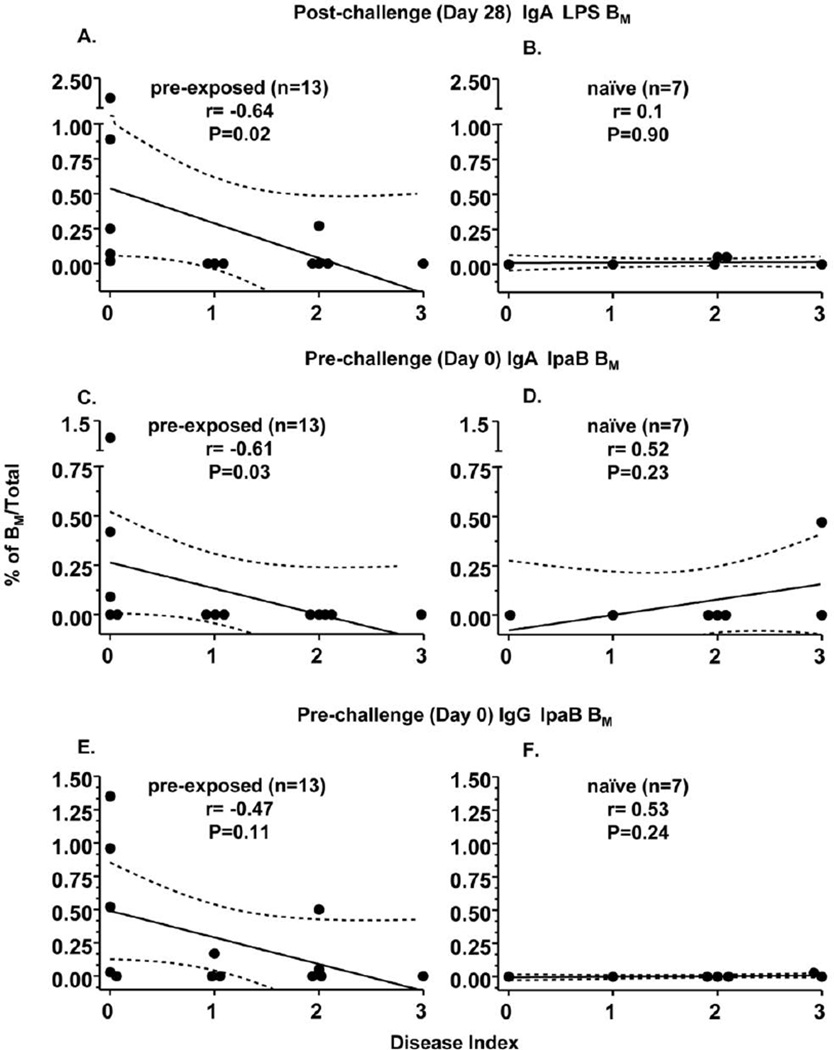

BM assays were performed using cryopreserved PBMC from volunteers before (pre) and after (post) challenge with wt-2457T as described in study design. BM responses to S. flexneri 2a LPS were correlated with disease index. As shown in Fig. 1A and 1B as well as Table 2, post-challenge IgA LPS-BM cell responses were found to correlate negatively (rho=−0.64, p=0.02) with disease index in the pre-exposed, but not in the naïve group. Of note, post-challenge IgA LPS-BM also showed a significant negative correlation (r=−0.48, p=0.03) with disease severity when all subjects were analyzed together (n=20) (data not shown). In contrast, neither pre-challenge IgA and IgG nor post-challenge IgG BM specific to LPS showed significant correlations with disease index (Table 2).

Figure 1. Correlation of specific BM and disease indices in subjects following challenge with wild-type S. flexneri 2a.

Antigen specific BM cells were measured before (Day 0) and after (Day 28) challenge with wild-type Shigella flexneri 2a. Percentages of antigen specific BM among those subjects who were pre-exposed to either vaccine or wild-type S. flexneri 2a prior to challenge (details in Materials and Methods) are shown in panels A, C, E and among naive volunteers are shown in panels B, D, F. The broken lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

Table 2.

Correlation of disease indices with BM

| pre-exposed (n=13) p(r) |

naïve (n=7) P(r) |

pre-exposed (n=13) p(r) |

naïve (n=7) p(r) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgA % BM/Total |

LPS |

IpaB |

||

| pre-challenge | 0.92 (−0.02) | 0.41 (−0.36) | 0.03**(−0.61) | 0.23 (0.52) |

| post-challenge | 0.02**(−0.64) | 0.90 (0.1) | 0.80 (−0.05) | 0.15 (−0.61) |

| IgG % BM/Total |

LPS |

IpaB |

||

| pre-challenge | 0.60 (−0.16) | 0.24 (−0.51) | 0.11#(−0.47) | 0.24 (0.53) |

| post-challenge | 0.75 (−0.13) | 0.24 (0.53) | 0.11#(−0.46) | 0.90 (−0.01) |

p=p value; r=Spearman's rho; LPS=lipopolysaccharide; IpaB=invasion plasmid antigen-B pre-exposed: exposed to wild-type Shigella (n=3/13) or EcSf2a-2 vaccine (n=10/13) prior to challenge naïve: healthy volunteers without prior exposure to Shigella

pre-challenge: prior to challenge with wild-type Shigella (day 0)

post-challenge: day 28 following challenge with wild-type Shigella

significant (p<0.05, two tail) with negative correlation

trend (p>0.05, ≤0.13, two tail) with negative correlation

As mentioned in Methods (section 2.2.), in the original studies performed in the 1990’s, the disease outcome following challenge was categorized dichotomously as “well” or “ill” [6]. As observed with disease indices, a negative correlation (rho=−0.52, p=0.02) was also observed between post-challenge IgA LPS-BM and the dichotomous outcome categorization (data not shown). Moreover, the magnitude (mean±SE) of post-challenge IgA LPS-BM was significantly higher among the “well” (n=7) compared to those who became “ill” (n=13) following challenge (0.46±0.28 vs 0.03±0.02, p=0.03) (data not shown).

IpaB is an immunogenic Shigella antigen which is largely conserved among the various Shigella serotypes [11, 20, 21, 26, 27]. Therefore, we measured IpaB-BM in pre-and post-challenge PBMC to investigate their correlation with disease outcome. Only pre-challenge IgA IpaB-BM cells were observed to be negatively correlated (rho=−0.61, p=0.03) with disease index (Table 2, Figs 1C, D) among pre-exposed volunteers. In contrast to LPS-BM, no statistically significant correlations were observed between post-challenge IgA IpaB-BM and disease index (Table 2). However, both pre- (Figure 1 E, F) and post-challenge IgG IpaB-BM (Table 2), showed a trend to be negatively correlated with disease index (rho=−0.47 and rho=−0.46, p=0.11, respectively). A trend towards a negative correlation of pre- and post-challenge IgG IpaB-BM with disease severity was also observed when all subjects were analyzed together (n=20; p=0.12 and p=0.09 respectively, data not shown).

The IpaB-BM measurements were also compared with dichotomous (i.e., well/ill) disease outcomes. Results showed similar trends to the correlations observed with disease index. However, as observed with LPS-BM measurements, correlations with disease index generally exhibited higher significance than when the categorical well/ill definition was used (data not shown). The magnitude of pre-challenge IgA IpaB-BM showed a trend to be higher in those who were “well” (n=7) comparing to those who were categorized as “ill” following challenge (n=13, 0.23±0.04 vs 0.04±0.04, p=0.09). Similar results were also observed with pre-challenge IgG IpaB BM (0.41±0.20 vs 0.06±0.04, p=0.15) but not with post-challenge IgA and IgG IpaB-BM. Throughout these studies, BM responses were not observed to the LcrV antigen used as an experimental negative control (data not shown).

3.2. Correlations between LPS and Ipa-specific ASC with disease severity

In contrast to BM assays which can be performed using cryopreserved specimens, ASC assays are typically performed on fresh cells. Therefore, LPS and Ipa- specific IgA and IgG ASC data from these 20 volunteers were retrieved from archived records of the original studies. Of note, at that time, Ipa-specific ASC assays were performed with a water-extract preparation [7] while in the present study, BM assays and serological determinations experiments were performed with a recombinant IpaB protein used as antigen. In the pre-exposed group (n=13, see methods), among the pre-challenge ASC assays performed 7 days post vaccination or experimental challenge (i.e., IgA and IgG ASC specific for both LPS and Ipa), only IgA LPS-ASC showed a trend to be negatively correlated with disease index (n=13, rho=−0.45, p=0.12) (data not shown). However, post-challenge ASC measured 7 days following challenge in the same group showed significant positive correlations between IgA LPS (rho=0.8, p<0.01), IgG LPS (rho=0.57, p<0.04) and IgA Ipa (rho=0.67, p=0.01) ASC with disease severity (data not shown).

3.3. Correlations between LPS- and IpaB-specific antibody responses with disease severity

Serum antibody assays were performed with cryopreserved pre-and post-challenge specimens from 29 subjects. Fifteen out the 29 volunteers received 4 doses of EcSf2a-2 vaccine (vaccinated) prior to challenge and 14 were naïve controls as described in Methods. All subjects were challenged with the wt-2457T strain.

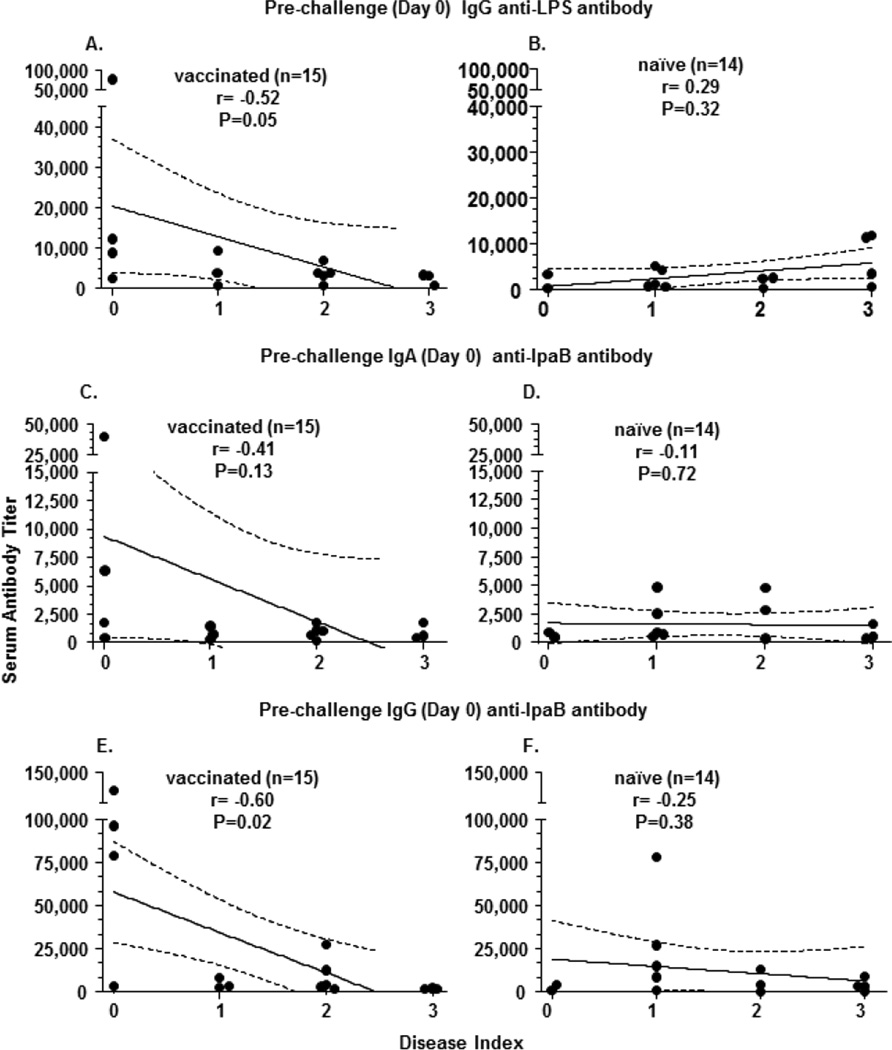

The vaccinated group showed a statistically significant negative correlation (rho=−0.52, p=0.05) between pre-challenge IgG LPS-antibody with disease index (Table 3, Figure 2A). No significant negative correlations were observed between pre- and post-challenge IgG or IgA LPS-antibody titers with disease index in the naive group (Table 3, Figure 2B).

Table 3.

Correlation of disease indices with serum antibody titers

| IgA antibody titer | IgG antibody titer | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| vaccinated (n=15) | naïve (n=14) | vaccinated (n=15) | naïve (n=14) | |

| p (r) | p (r) | p (r) | p (r) | |

| LPS | LPS | |||

| pre-challenge | 0.42 (−0.23) | 0.02##(0.61) | 0.05**(−0.52) | 0.32 (0.29) |

| post-challenge | 0.40 (0.24) | 0.22 (0.35) | 0.79 (−0.08) | 0.19 (0.38) |

| IpaB | IpaB | |||

| pre-challenge | 0.13#(−0.41) | 0.72 (−0.11) | 0.02**(− 0.60) | 0.38 (−0.25) |

| post-challenge | 0.07#(−0.48) | 0.80 (−0.08) | 0.06 #(−0.50) | 0.55 (−0.17) |

p=p value; r=Spea rm an's rho; LPS=lipopo lysaccharide; Ipa B =invasion plasmid ant igen-B vaccinated: immunized with 4 doses of EcSf2a-2 prior to challenge naïve: healthy volunteers without prior exposure to Shigella

pre-challenge: prior to challenge with wild-type Shigella (day 0)

post-challenge: day 28 following challenge with wild-type Shigella

significant (p<0.05, two tail) with negative correlation

trend (p>0.05,≤0.13, two tail) with negative correlation

significant (p<0.05, two tail) with positive correlation

Figure 2. Correlation of specific serum antibody titers and disease indices in subjects following challenge with wild-type S. flexneri 2a.

Antigen specific serum antibody titers were measured before (Day 0) and after (Day 28) challenge with wild-type Shigella flexneri 2a. The antibody titers among those who were immunized with EcSf2a-2 (vaccinated) prior to challenge are shown in panels A, C, E and among naïve volunteers are shown in panels B, D, F. The broken lines represent 95% confidence intervals

Antibody titers against recombinant IpaB in these subjects were also measured and correlated with disease index. In contrast to the results observed with LPS, both pre-and post-challenge IgA IpaB-antibody titers in the vaccinated group, but not in the naïve group, showed a trend to be negatively correlated (p=0.13 and p=0.07, respectively) with disease index (Table 3, Figure 2C, D). On the other hand, pre-challenge IgG IpaB-antibody titers in vaccinated, but not naïve volunteers, showed a significant negative correlation (rho=−0,6, p=0.02) with disease index (Table 3, Figure 2 E, F). Post-challenge IgG IpaB-antibody titers showed similar results with a trend toward a negative correlation with disease index in vaccinees (rho=−0.5, p=0.06) (Table 3). Similar results showing negative correlations of pre- and post-challenge IgG IpaB with disease severity was also observed when all subjects were analyzed together (n=29; p=0.03 and p=0.06 respectively; data not shown).

4. Discussion

The identification of immune correlates of protection can greatly accelerate vaccine development [28, 29]. Immunological responses elicited by vaccines or natural infection that statistically “correlate with protection” may be causally responsible (mechanistic correlate) or may be non-mechanistic, which nevertheless predicts vaccine efficacy through its correlation with other immune response(s) that mechanistically protect [29]. The induction of BM responses following vaccination or natural infection with enteric pathogens that we [19–23] and others [30, 31] have reported led to the speculation that BM likely play an important role in protection. Recently, in a case-control study, the presence of V. cholerae O1 LPS-specific IgG-BM cells in PBMC was associated with a decreased risk of infection among household contacts suggesting a role of IgG LPS-BM in protection [32]. However, the possibility that BM responses to enteric bacteria can be used as correlates of protection has not been directly addressed in a volunteer challenge model. In the present study we took advantage of a unique collection of cryopreserved specimens collected during clinical studies conducted in the early 1990’s at the CVD and measured BM and antibody responses against two key Shigella antigens (S. flexneri 2a LPS and the conserved protein antigen IpaB) to investigate the presence of statistical correlations between these immune responses and protection against disease following challenge with wt-2457T.

These correlations were performed using a new disease categorization that graded the disease severity to explore whether this approach will add power to detect differences. The observation that a higher frequency of IgA LPS-BM measured 28 days after challenge negatively correlated with disease severity in subjects who were pre-exposed to Shigella but not among naïve volunteers, suggests a possible role of IgA LPS-BM responses in protection. This correlation was observed whether the disease index or well/ill dichotomous categorizations were used in the analysis, although significance levels were somewhat higher when disease index was used in the calculations. Of note, this correlation was absent with IgA LPS-BM levels measured prior to challenge. It is possible that a considerable proportion of the LPS-BM induced by exposure to Shigella antigens 28 days prior to challenge had already homed to their target sites (e.g., lymph nodes, bone marrow, gut) [33–35]. Upon the subsequent challenge with wt-2457T, a robust recall response involving a new wave of proliferation and differentiation ensued, resulting in the higher levels of LPS-BM cells present in circulation 28 days later. This suggests that different time points might need to be evaluated to detect these responses. Moreover, the kinetics of BM in circulation might be different for LPS (a T-cell independent antigen) than for IpaB (a protein antigen).”

The observation that the categorical outcome variable used in these studies as disease index instead of dichotomous determination of clinical outcome resulted in increased power to define immunological correlates of protection, suggests that this approach can be of value in upcoming vaccine and challenge studies.

The clinical studies conducted during the 1990’s suggested IgA-LPS ASC (plasmablasts/plasma cells) may be considered one of the key indicators of protection against wild type Shigella infection [7]. Similar to those observations, our post-hoc analysis showed a trend towards a negative correlation between pre-challenge LPS specific IgA-ASC and disease severity. Likewise, post-challenge IgA LPS BM measurements showed a statistically significant negative correlation with disease severity, while post-challenge IgA LPS-ASC (along with IgG LPS or IgA Ipa-ASC) demonstrated a statistically significant positive correlation. These data suggest that the presence of higher ASC levels following challenge is indicative of a strong primary response to wild-type challenge rather than of a protective secondary response that were observed with IgA LPS-BM.

Taken together, negative correlations of post-challenge IgA LPS-BM, and pre-challenge IgA LPS-ASC (but not IgG), with disease severity support the previously advanced notion that mucosal immune responses against LPS may have a dominant role in protection against Shigella [7, 20, 21]. The current findings provide, to our knowledge, the first direct evidence that the frequency of IgA LPS-BM correlates with protection from shigellosis following challenge with wild-type organisms.

The available evidence strongly suggests that serogroup and serotype specific-protection is elicited by natural Shigella infection or challenge [4, 6–8, 10, 36–38]; however whether the protection is mediated predominantly by mucosal (sIgA), systemic (IgG) anti-O antigen antibodies, and/or additional effector immune responses remains controversial [4]. The results in the present study showing that IgG but not IgA anti-LPS serum antibody titers negatively correlate with disease severity reinforces the notion that mucosal IgA and serum IgG anti-LPS antibodies play a role in protection. Of note, although our results suggest the lack of a significant role of serum IgA-anti LPS in protection, we observed a positive correlation between pre-vaccination IgA anti-LPS and disease index in the naïve group. It is unclear at present what could be the mechanism(s) that explain this counterintuitive association in naïve subjects. Future studies will be required to confirm these findings and address this issue in detail.

IpaB, one of the conserved components of the Shigella type III secreting system [27, 39], has been shown to be highly immunogenic among infected individuals, as well as in candidate vaccine trials [11, 12, 20, 21, 26]. Moreover, we had previously shown the induction of IgG and IgA BM against IpaB following immunization with Shigella candidate vaccines [20, 21]. In the present study, using a highly purified recombinant IpaB preparation, we further expanded these observations by demonstrating for the first time an association of pre-existing anti-IpaB BM and serum antibody levels with protection in a human challenge model. These results suggest that IpaB could also have a role in protection, providing additional support for the inclusion of this conserved protein as a component of broad based vaccines against Shigella.

As per protocol, all volunteers received antibiotics if severely ill or on day 5 post vaccination and challenge. Although at present it is not definitively known what effect, if any, this antibiotic treatment has on the immune response, it is probable that this effect is minimal since in symptomatic individuals as the bacteria has replicated sufficiently to induce disease and in asymptomatic individuals most shedding has disappeared by day 5, likely due to the host’s immune response killing of Shigella.

A limitation of this study was the relatively low sample size. Future vaccination/challenge studies with larger numbers of volunteers will be required to confirm and expand the results described in these studies. Moreover, due to the limited number of cells available, measurement of immunity against a wide range of Shigella antigens (e.g., IpaC, IpaD VirG) was not possible. However, our results support the contention that protection against Shigella is likely mediated by multiple antigen-specific immune responses, including IgA BM cells. This might constitute an advantage of live oral vaccines over subunit vaccines since they are likely to elicit stronger, more persistent and more diverse immune responses that results in enhanced protective immunity.

5. Conclusions

In this manuscript we provide, for the first time, initial evidence of a statistical association between the induction of LPS and IpaB antigen specific B memory cells and protection in a human S. flexneri 2a challenge model, suggesting that these responses may be important in protecting the host from shigella infection. We also report significant negative correlations of pre-challenge IgG anti-LPS and anti-IpaB titers in vaccinated volunteers and disease severity upon challenge. These observations suggest that the presence of BM cells should be considered an important component of the effector immunity to be evaluated in future clinical studies with relevant Shigella vaccines.

Highlights.

Studied immunity to LPS and IpaB antigens in a human Shigella challenge model

Specific B memory cells inversely correlated with disease severity upon challenge

LPS and IpaB antibodies also showed negative correlations with disease severity

Shigella-specific B memory and antibodies might play a protective role in humans

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the volunteers who participated in the studies and the CVD nurses who assisted in the care of volunteers. We thank Dr. Haiyen Chen and Mr. Shah J Zafar, for outstanding technical support and Dr. William Blackwelder for his statistical expertise and input. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [Cooperative Center for Translational Research in Human Immunology and Biodefense U19 AI082655 to M.B.S and Career Development Award K23 AI065759 to J.K.S]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases or the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- ASC

antibody secreting cell

- BM

memory B cells

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- ELISpot

enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot assay

- Ig

immunoglobulin

- Ipa

Invasion plasmid antigen

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- SFC

spot forming cells

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.von Seidlein L, Kim DR, Ali M, Lee H, Wang X, Thiem VD, Canh dG, Chaicumpa W, Agtini MD, Hossain A, Bhutta ZA, Mason C, Sethabutr O, Talukder K, Nair GB, Deen JL, Kotloff K, Clemens J. A multicentre study of Shigella diarrhoea in six Asian countries: disease burden, clinical manifestations, and microbiology. PLoS. Med. 2006;3:e353. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kotloff KL, Winickoff JP, Ivanoff B, Clemens JD, Swerdlow DL, Sansonetti PJ, Adak GK, Levine MM. Global burden of Shigella infections: implications for vaccine development and implementation of control strategies. Bull. World Health Organ. 1999;77:651–666. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pickering LK. Antimicrobial resistance among enteric pathogens. Semin. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. 2004;15:71–77. doi: 10.1053/j.spid.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levine MM, Kotloff KL, Barry EM, Pasetti MF, Sztein MB. Clinical trials of Shigella vaccines: two steps forward and one step back on a long, hard road. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007;5:540–553. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newland JW, Hale TL, Formal SB. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of an aroD deletion-attenuated Escherichia coli K12-Shigella flexneri hybrid vaccine expressing S. flexneri 2a somatic antigen. Vaccine. 1992;10:766–776. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(92)90512-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kotloff KL, Nataro JP, Losonsky GA, Wasserman SS, Hale TL, Taylor DN, Sadoff JC, Levine MM. A modified Shigella volunteer challenge model in which the inoculum is administered with bicarbonate buffer: clinical experience and implications for Shigella infectivity. Vaccine. 1995;13:1488–1494. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kotloff KL, Losonsky GA, Nataro JP, Wasserman SS, Hale TL, Taylor DN, Newland JW, Sadoff JC, Formal SB, Levine MM. Evaluation of the safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy in healthy adults of four doses of live oral hybrid Escherichia coli-Shigella flexneri 2a vaccine strain EcSf2a-2. Vaccine. 1995;13:495–502. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)00011-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen D, Green MS, Block C, Slepon R, Ofek I. Prospective study of the association between serum antibodies to lipopolysaccharide O antigen and the attack rate of shigellosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1991;29:386–389. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.2.386-389.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DuPont HL, Hornick RB, Snyder MJ, Libonati JP, Formal SB, Gangarosa EJ. Immunity in shigellosis. II. Protection induced by oral live vaccine or primary infection. J. Infect. Dis. 1972;125:12–16. doi: 10.1093/infdis/125.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferreccio C, Prado V, Ojeda A, Cayyazo M, Abrego P, Guers L, Levine MM. Epidemiologic patterns of acute diarrhea and endemic Shigella infections in children in a poor periurban setting in Santiago, Chile. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1991;134:614–627. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaminski RW, Oaks EV. Inactivated and subunit vaccines to prevent shigellosis. Expert. Rev. Vaccines. 2009;8:1693–1704. doi: 10.1586/erv.09.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oaks EV, Hale TL, Formal SB. Serum immune response to Shigella protein antigens in rhesus monkeys and humans infected with Shigella spp. Infect. Immun. 1986;53:57–63. doi: 10.1128/iai.53.1.57-63.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oberhelman RA, Kopecko DJ, Salazar-Lindo E, Gotuzzo E, Buysse JM, Venkatesan MM, Yi A, Fernandez-Prada C, Guzman M, Leon-Barua R. Prospective study of systemic and mucosal immune responses in dysenteric patients to specific Shigella invasion plasmid antigens and lipopolysaccharides. Infect. Immun. 1991;59:2341–2350. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.7.2341-2350.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Islam D, Christensson B. Disease-dependent changes in T-cell populations in patients with shigellosis. APMIS. 2000;108:251–260. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0463.2000.d01-52.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raqib R, Ljungdahl A, Lindberg AA, Andersson U, Andersson J. Local entrapment of interferon gamma in the recovery from Shigella dysenteriae type 1 infection. Gut. 1996;38:328–336. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.3.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Samandari T, Kotloff KL, Losonsky GA, Picking WD, Sansonetti PJ, Levine MM, Sztein MB. Production of IFN-gamma and IL-10 to Shigella invasins by mononuclear cells from volunteers orally inoculated with a Shiga toxin-deleted Shigella dysenteriae type 1 strain. J. Immunol. 2000;164:2221–2232. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crotty S, Ahmed R. Immunological memory in humans. Semin. Immunol. 2004;16:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2004.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lanzavecchia A, Bernasconi N, Traggiai E, Ruprecht CR, Corti D, Sallusto F. Understanding and making use of human memory B cells. Immunol. Rev. 2006;211:303–309. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00403.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramirez K, Wahid R, Richardson C, Bargatze RF, El-Kamary SS, Sztein MB, Pasetti MF. Intranasal vaccination with an adjuvanted Norwalk virus-like particle vaccine elicits antigen-specific B memory responses in human adult volunteers. Clin. Immunol. 2012;144:98–108. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simon JK, Wahid R, Maciel M, Jr, Picking WL, Kotloff KL, Levine MM, Sztein MB. Antigen-specific B memory cell responses to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and invasion plasmid antigen (Ipa) B elicited in volunteers vaccinated with liveattenuated Shigella flexneri 2a vaccine candidates. Vaccine. 2009;27:565–572. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.10.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simon JK, Maciel M, Jr, Weld ED, Wahid R, Pasetti MF, Picking WL, Kotloff KL, Levine MM, Sztein MB. Antigen-specific IgA B memory cell responses to Shigella antigens elicited in volunteers immunized with live attenuated Shigella flexneri 2a oral vaccine candidates. Clin. Immunol. 2011;139:185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wahid R, Pasetti MF, Maciel M, Jr, Simon JK, Tacket CO, Levine MM, Sztein MB. Oral priming with Salmonella Typhi vaccine strain CVD 909 followed by parenteral boost with the S. Typhi Vi capsular polysaccharide vaccine induces CD27+S. Typhi-specific IgA and IgG B memory cells in humans. Clin. Immunol. 2011;138:187–200. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wahid R, Simon R, Zafar SJ, Levine MM, Sztein MB. Live oral typhoid vaccine Ty21a induces cross reactive humoral immune responses against S. Paratyphi A and S. Paratyphi B in humans. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2012 doi: 10.1128/CVI.00058-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Westphal O, Jann K, Himmelspach K. Chemistry and immunochemistry of bacterial lipopolysaccharides as cell wall antigens and endotoxins. Prog. Allergy. 1983;33:9–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crotty S, Aubert RD, Glidewell J, Ahmed R. Tracking human antigen-specific memory B cells: a sensitive and generalized ELISPOT system. J. Immunol. Methods. 2004;286:111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2003.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oaks EV, Turbyfill KR. Development and evaluation of a Shigella flexneri 2a and S. sonnei bivalent invasin complex (Invaplex) vaccine. Vaccine. 2006;24:2290–2301. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sani M, Allaoui A, Fusetti F, Oostergetel GT, Keegstra W, Boekema EJ. Structural organization of the needle complex of the type III secretion apparatus of Shigella flexneri. Micron. 2007;38:291–301. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edwards KM. Development, acceptance, and use of immunologic correlates of protection in monitoring the effectiveness of combination vaccines. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001;33(Suppl 4):S274–S277. doi: 10.1086/322562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Plotkin SA, Gilbert PB. Nomenclature for immune correlates of protection after vaccination. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;54:1615–1617. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harris AM, Bhuiyan MS, Chowdhury F, Khan AI, Hossain A, Kendall EA, Rahman A, LaRocque RC, Wrammert J, Ryan ET, Qadri F, Calderwood SB, Harris JB. Antigen-specific memory B-cell responses to Vibrio cholerae O1 infection in Bangladesh. Infect. Immun. 2009;77:3850–3856. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00369-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jayasekera CR, Harris JB, Bhuiyan S, Chowdhury F, Khan AI, Faruque AS, LaRocque RC, Ryan ET, Ahmed R, Qadri F, Calderwood SB. Cholera toxinspecific memory B cell responses are induced in patients with dehydrating diarrhea caused by Vibrio cholerae O1. J. Infect. Dis. 2008;198:1055–1061. doi: 10.1086/591500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patel SM, Rahman MA, Mohasin M, Riyadh MA, Leung DT, Alam MM, Chowdhury F, Khan AI, Weil AA, Aktar A, Nazim M, LaRocque RC, Ryan ET, Calderwood SB, Qadri F, Harris JB. Memory B cell responses to Vibrio cholerae O1 lipopolysaccharide are associated with protection against infection from household contacts of patients with cholera in Bangladesh. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2012;19:842–848. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00037-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.El-Kamary SS, Pasetti MF, Mendelman PM, Frey SE, Bernstein DI, Treanor JJ, Ferreira J, Chen WH, Sublett R, Richardson C, Bargatze RF, Sztein MB, Tacket CO. Adjuvanted intranasal Norwalk virus-like particle vaccine elicits antibodies and antibody-secreting cells that express homing receptors for mucosal and peripheral lymphoid tissues. J. Infect. Dis. 2010;202:1649–1658. doi: 10.1086/657087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A, Araki K, Ahmed R. From vaccines to memory and back. Immunity. 2010;33:451–463. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sundstrom P, Lundin SB, Nilsson LA, Quiding-Jarbrink M. Human IgAsecreting cells induced by intestinal, but not systemic, immunization respond to CCL25 (TECK) and CCL28 (MEC) Eur. J. Immunol. 2008;38:3327–3338. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cam PD, Pal T, Lindberg AA. Immune response against lipopolysaccharide and invasion plasmid-coded antigens of shigellae in Vietnamese and Swedish dysenteric patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1993;31:454–457. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.454-457.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen D, Green MS, Block C, Rouach T, Ofek I. Serum antibodies to lipopolysaccharide and natural immunity to shigellosis in an Israeli military population. J. Infect. Dis. 1988;157:1068–1071. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.5.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cohen D, Green MS, Block C, Slepon R, Lerman Y. Natural immunity to shigellosis in two groups with different previous risks of exposure to Shigella is only partly expressed by serum antibodies to lipopolysaccharide. J. Infect. Dis. 1992;165:785–787. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.4.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hale TL, Sansonetti PJ, Schad PA, Austin S, Formal SB. Characterization of virulence plasmids and plasmid-associated outer membrane proteins in Shigella flexneri, Shigella sonnei, and Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 1983;40:340–350. doi: 10.1128/iai.40.1.340-350.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]