Abstract

Although extensive homology exists between their extracellular domains, natural killer cell inhibitory receptors KIR2DL2*001 and KIR2DL3*001 have previously been shown to differ substantially in their HLA-C binding avidity. To explore the largely uncharacterized impact of allelic diversity, the most common KIR2DL2/3 allelic products in European American and African American populations were evaluated for surface expression and binding affinity to their HLA-C group 1 and 2 ligands. Although no significant differences in the degree of cell membrane localization were detected in a transfected human NKL cell line by flow cytometry, surface plasmon resonance and KIR binding to a panel of HLA allotypes demonstrated that KIR2DL3*005 differed significantly from other KIR2DL3 allelic products in its ability to bind HLA-C. The increased affinity and avidity of KIR2DL3*005 for its ligand was also demonstrated to have a larger impact on the inhibition of IFN-γ production by the human KHYG-1 NK cell line compared to KIR2DL3*001, a low affinity allelic product. Site-directed mutagenesis established that the combination of arginine at residue 11 and glutamic acid at residue 35 in KIR2DL3*005 were critical to the observed phenotype. Although these residues are distal to the KIR/HLA-C interface, molecular modeling suggests that alteration in the interdomain hinge angle of KIR2DL3*005 towards that found in KIR2DL2*001, another strong receptor of the KIR2DL2/3 family, may be the cause of this increased affinity. The regain of inhibitory capacity by KIR2DL3*005 suggests that the rapidly evolving KIR locus may be responding to relatively recent selective pressures placed upon certain human populations.

Introduction

Expressed on the surface of some natural killer cells and T lymphocytes, the killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIR)4 (1) are generally either inhibitory or activating receptors, the former defined by a long cytoplasmic region bearing two immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs (ITIMs) (2, 3) and the latter by a truncated intracellular tail and association with an intracellular adaptor protein bearing an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activating motif (4). While 14 KIR receptors have been described in humans, only a subset of the genes encoding these receptors are usually found in an individual (5). Furthermore, the expression of each KIR gene varies stochastically so that a single NK cell may express only one to a few receptors encoded by the KIR repertoire present in that individual (6, 7).

KIR are an integral part of a complex repertoire of cell surface signaling molecules used to modulate the NK activation response to virally infected or malignant cells (8). Ensuring tolerance to self, inhibitory KIR bind HLA ligands and their signals generally override any stimulatory signals generated by activating KIR or other NK receptors (9, 10). Down-regulation of HLA ligands during infection or transformation removes the inhibitory signal (11). Then, if an NK cell has been “licensed”, through the interaction of expressed inhibitory KIR and HLA ligand during its development, the cell may respond robustly to activating ligands leading to cytotoxicity and /or cytokine production aimed at destroying abnormal cells (9, 12, 13).

It is clear that the multiple KIR and the unique KIR haplotypes found in individuals are the result of gene duplication and deletion throughout evolution (14, 15) Of the three inhibitory KIR receptors that bind HLA-C, KIR2DL2 appears to be encoded by a fusion gene formed by unequal crossing over between KIR2DL3 (contributing the extracellular domains) and KIR2DL1 (contributing the intracellular tail) (16). Segregation analysis and gene positioning within the KIR haplotypes suggests that KIR2DL2 and KIR2DL3 behave as alleles at a single locus (KIR2DL2/3) (17). As expected based on the homology in their ligand-binding domains, KIR2DL2 and KIR2DL3 bind a similar set of HLA-C ligands although KIR2DL2*001 binds HLA-C with a higher affinity than KIR2DL3*001. Specifically, the lower affinity of KIR2DL3 has been attributed to arginine 16 of the N-terminal D1 extracellular domain and cysteine 148 of the D2 domain, which decrease its avidity for HLA-C through a more acute inter-domain hinge angle between D1 and D2 (18).

Unlike other inhibitory KIR that exhibit a more restricted HLA ligand repertoire (e.g., KIR3DL1 binds only HLA-Bw4), KIR2L2, in particular, binds many HLA-C allelic products although at differing affinities. KIR2DL2 has a much greater affinity for HLA-C group 1 molecules, defined by residues S77 and N80 of the HLA α-chain, while many HLA-C group 2 molecules, defined by residues N77 and K80, are bound at a lower but demonstrable binding affinity (18, 19). KIR2DL3 binds predominantly to group 1 HLA-C molecules. Variation in binding is also noted among the HLA-C group 1 or group 2 molecules, although the reason for this variation has not yet been elucidated (18).

KIR genes are polymorphic (20) and this allelic diversity appears to be co-evolving with their HLA ligands (21, 22). This variation may influence the function of KIR receptors by impacting the affinity for ligand and/or cellular localization. For example, inhibitory KIR3DL1*002, due to a change at residue 238 in one of the extracellular domains, yields stronger levels of inhibition as compared to KIR3DL1*007 when triggered by its HLA-Bw4 ligand (23). Moreover, polymorphic residues affecting the affinity between KIR and its HLA ligands are likely to result in variable degrees of NK licensing and, therefore, effector capability, a phenomenon which has been studied for Ly49A, the murine functional analog of KIR (24, 25). Finally, variation in the KIR extracellular domains has also been demonstrated to affect the levels of surface localization of certain allelic products and, in the case of KIR2DL2*004, the retention of an immature, and likely nonfunctional, isoform within the cytoplasm (26). Therefore, in order to appreciate the phenotypes of specific KIR allelic products, it is necessary to evaluate the impact of specific polymorphic residues upon surface expression as well as ligand specificity and affinity.

As we hypothesize that the structural changes induced by genetic polymorphism may impact KIR2DL2/3 function via modification for its affinity towards HLA-C, the current study seeks to investigate the significance of variation within the extracellular domains of the six most common KIR2DL2/3 allelic products. While it has been established that KIR2DL2*001 binds HLA-C with a higher affinity than KIR2DL3*001 (18, 27), comparatively little is known about the functional capacity of other allelic products of this locus. Considering that strong clinical correlations have been established between either the presence or absence of these KIR in the setting of acute hepatitis C infection (28), acute myelogenous leukemia (29), and recurrent spontaneous abortion (30), investigation of the affinity between common KIR2DL2/3 for their cognate ligands at an allelic product-level resolution is paramount to predicting the NK response in the clinical setting.

Materials and methods

Population study

To assess allelic diversity, KIR2DL2/3 alleles carried by 100 unrelated individuals with African American ancestry from the human variation panel from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) Human Genetics Resource Center DNA and Cell Line Repository (http://ccr.coriell.org/nigms/) were identified by DNA sequencing. Briefly, testing for the presence or absence of specific KIR loci used polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification with visualization by agarose gel electrophoresis. To obtain a DNA sequence covering most of the coding regions of KIR2DL2/3 (31), several PCR primer pairs were used to generate three-four overlapping amplicons that were characterized by Sanger sequencing (31). Allele frequencies were calculated by gene counting. KIR2DL3/2 alleles carried by 76 unrelated individuals with European ancestry from the National Marrow Donor Program® (NMDP) Research Sample Repository (http://www.nmdpresearch.org/SAMPLES/samples_idx.html) were described previously (32).

In order to identify possible deviances from Hardy-Weinberg proportions (HWP), PyPop (Python for Population genetics, version 0.7.0 http://www.pypop.org) was utilized to analyze the KIR2DL2/3 allelic frequency data using the exact test of Guo and Thompson (33). This algorithm measures the degree to which the observed allelic frequencies deviate from those that are expected if the population is in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, which assumes that the measured frequencies are the result of random mating and that no substantial migration, mutation, or other form of selection has occurred. The Monte Carlo simulation was used to determine exact p values in order to evaluate potential deviations from HWP.

DNA constructs

KIR2DL2*001 cDNA, provided by Dr. Francisco Borrego (Laboratory of Molecular and Developmental Immunology, Division of Monoclonal Antibodies, OBP, CDER, FDA, Bethesda, MD, USA), was amplified via PCR and inserted into the pCR8/GW/TOPO (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) entry vector. Gateway Technology (Invitrogen) was utilized used to create the KIR2DL2*001 expression vector using the pEF-DEST51 (Invitrogen) destination vector, which encodes a C-terminal V5 tag. Site directed mutagenesis was performed via QuickChange II (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) in order to generate the remaining KIR2DL2/3 alleles for the present study. Finally, a sequence coding for YPYDVPDYA was inserted between the regions encoding the leader peptide and the KIR first Ig domain in order to generate N-terminal HA-tagged constructs.

For functional analysis of selected sKIR, DNAs coding for the extracellular regions of KIR2DL2*001, KIR2DL3*001, and KIR2DL3*005 were fused by PCR to DNA coding for the intracellular region of KIR2DL2*001. Specifically, exons 1 though 6 (encoding the extracellular domains and stem of KIR) were fused in-frame with exons 7 through 9 of KIR2DL2*001 (encoding the transmembrane through cytoplasmic regions) via PCR and inserted into pEF-DEST51. BP clonase (Invitrogen) was used to shuttle these KIR fusion constructs into the pDONR™221 donor vector (Invitrogen). Subsequently, these constructs were then transferred to the pLenti4/V5-DEST destination vector (Invitrogen) using LR clonase (Invitrogen).

The HLA-C*03:04 and HLA-C*06:02-encoding vectors were obtained from the International Histocompatibility Working Group (http://www.ihwg.org). The leader sequence of each vector was modified using site directed mutagenesis to mutate the leader sequence peptide in order to abrogate HLA-E expression when transfected into 721.221 cells as described by Moesta and colleagues (18).

Cell lines, culture, and gene expression

The KIR-negative NKL and HLA-A,B,C-negative 721.221 cell lines were the kind gift of Dr. Francisco Borrego. The protocols for cell culture and transfection of the NKL and 721.221 cell lines have been previously described (26, 34). Following transient transfection, NKL cells were cultured for 18h and then assayed for KIR expression. Sorted by flow cytometry to establish stable cell lines, the 721.221 cells expressing HLA-C*03:04 and C*06:02 were maintained in 1 mg/ml G-418 (Invitrogen).

The KHYG-1 cell line was obtained from the Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources cell bank (Osaka, Japan) and was cultured under the same conditions as the NKL cell line (34). Per manufacturer's guidelines, the ViraPower™ Lentiviral Gateway® Expression Kit (Invitrogen) was used to produce viral particles encoding KIR. The KHYG-1 cell line was transiently transduced with lentiviral vectors carrying KIR2DL2*001, KIR2DL3*001, or KIR2DL3*005 cDNA encoding the extracellular region fused to the KIR2DL2*001 exons encoding the intracellular region. The levels of KIR surface expression were analyzed 18 hours post-transfection by flow cytometry with a FITC conjugated antibody specific for CD158b (KIR2DL2/3) (clone CH-L, BD Biosciences, San Jose, California, USA) to ensure that all transductants possessed similar levels of surface-localized receptor.

Flow cytometry

FITC conjugated antibody specific for CD158b (clone CH-L) and, where appropriate, FITC conjugated antibody specific for the HA tag (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were used to stain for extracellular expression of KIR2DL2/3. Total expression of KIR was quantified via PE conjugated antibody specific for the V5 tag (Invitrogen). The staining protocol was performed as previously described (34). Briefly, the ratio of extracellular stain mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) (anti-CD158b or anti-HA) to total KIR MFI (anti-V5) was normalized to that of either KIR2DL2*001 or KIR2DL3*001.

Surface biotinylation

The quantification of surface-biotinylated KIR was assessed as previously described (34), with modifications. Briefly, NKL cells were transiently transfected with the appropriate KIR construct and, 18 hours later, biotinylated with NHS-LC-Biotin (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Following cell lysis, biotinylated surface proteins were immunoprecipitated with streptavidin-coated sepharose beads (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, New Jersey, USA). After denaturing and reduction of the protein samples and electrophoresis on 4-15% polyacrylamide Tris-HCL Ready Gels® (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), KIR was detected by a 1/500 dilution of anti-V5 antibody (Invitrogen) and a 1/20,000 dilution of an anti-mouse streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase-conjugated IgG heavy and light chain antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA, USA). The enhanced chemiluminescent detection kit (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA) was used to visualize protein bands.

Generation of recombinant proteins

Recombinant soluble KIR (sKIR) were manufactured by Genescript Inc. (Piscataway, NJ, USA). Briefly, cDNAs encoding the extracellular domains of human IgG1 Fc-tagged KIR2DL2*001, *003, *006, KIR2DL3*001, *002, or *005 were subcloned into an insect expression vector, from which a recombinant baculovirus was generated. The secreted sKIR from infected SF9 cells was then column purified using the C-terminal Fc tag. HLA-C tetramers were produced by the NIH Tetramer Core Facility (Atlanta, GA, USA). HLA-C*03:04 tetramers were refolded with the peptide GAVDPLLAL while HLA-C*06:02 tetramers were refolded with the peptide YQFTGIKKY, two peptides previously demonstrated to be bound by these allelic products (35, 36). The peptides were synthesized by Anaspec (Fremont, CA, USA). The recombinant proteins were tested for proper folding by measuring the binding to conformationally specific antibodies (αCD158b for the sKIR recombinant proteins and W6/32 (anti-HLA class I) for the HLA-C tetramers) immobilized to a CM5 sensor chip with a Biacore T100 instrument. As described by Graef et al. (37), the integrity of the sKIR fusion proteins was also evaluated by capturing 100 μg/ml sKIR with 20μl paramagnetic beads coated with anti-human Fc antibody (Bangs Laboratories, Fishers, IN, USA), followed by incubation with either an anti-CD158b PE-conjugated antibody (clone CH-L) (BD Biosciences) or anti-CD158a PE-conjugated antibody (clone EB6B; anti-KIR2DL1, 2DS1, and 2DL3*005) (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). Antibody binding was interpreted using flow cytometry.

Surface plasmon resonance

Binding of sKIR to immobilized HLA-C tetramers was monitored with a Biacore T100 instrument (Biacore, Piscataway, NJ, USA). Biacore running buffer HBS (25 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 3.4 mM EDTA, and 0.005% surfactant p20) was used in all binding assays. The HLA-C tetramers were immobilized by coupling to a CM5 sensor chip using the Amine Coupling Kit (Biacore), with a target density of ~6000 resonance units (RU) of each tetramer bound to an individual flow cell. The sKIR analytes were diluted in HBS, with concentrations ranging from 3.75 to 240 nM, and injected into the flow cell chamber with a contact time of 60 seconds and a dissociation time of 900 seconds. Due to predicted instabilities of HLA-C tetramers (38), acidic regeneration of the chip was not performed.

KIR/single-antigen HLA bead binding assay

The sKIR recombinant proteins were evaluated for binding to a panel of HLA Class I single-antigen beads (One Lambda, Canoga Park, CA, USA). A range of sKIR concentrations (4-400 μg/ml) in 20 μl PBS were incubated with 5 μl beads for 30 minutes, oscillating at 300 RPM, at room temperature. The beads were washed three times in 1x wash buffer (One Lambda) at 3000 relative centrifugal force for 5 minutes, followed by labeling with PE conjugated antibody specific for human Fc (One Lambda) for 30 minutes, oscillating at 300 RPM, at room temperature. After washing two times in 1x wash buffer, a Luminex 100 reader (Luminex, Austin, TX, USA) was utilized to measure the MFI of at least 200 events per single-antigen bead. The resulting MFI values generated by the Luminex instrument for each KIR-HLA interaction were then background subtracted from the MFI value of the negative control beads. Further, MFI values for each allotype were adjusted for HLA content via their interaction with the W6/32 antibody and were normalized to HLA-C*01:02. Specifically, HLA-normalized sKIR binding was calculated using the formula: normalized sKIR MFI = [(MFI of sKIR binding to HLA-C [allotype X]) – (MFI of sKIR binding to negative control bead)] / [(MFI of W6/32 antibody binding to HLA-C [allotype X]) / (MFI of W6/32 antibody binding to HLA-C*01:02)]. The titration binding curves are derived from the one site binding (hyperbola) equation using a nonlinear regression curve fit by Prism 5.0f (39). The “heatmap.2” tool, a component of the gplots package of R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (40), was used to generate heat maps of sKIR avidity for all tested HLA-C allotypes. Utilizing McQuitty's method (41), the clustering algorithm generated dendrograms grouping either KIR or HLA-C molecules based upon avidity.

IFN-γ functional assay

The quantification of IFN-γ production was assessed as previously described (42), with modifications. Briefly, the KHYG-1 cell line was transiently transduced with lentiviral vectors encoding KIR and, after 18 hours, incubated with HLA-negative 721.221 cells or 721.221 cells stably transfected with HLA-C*03:04 or HLA-C*06:02 for 6 hours at a ratio of 1:1. Conducted at 37°C in a 5% CO2 environment, each assay condition consisted of 1 × 105 effectors and 1 × 105 targets in 200 μl culture media. Following the incubation period, the cell culture supernatant was harvested and assayed for IFN-γ production via the Procarta Immunoassay kit (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). The percentage of NK inhibition was calculated by the formula: percentage inhibition = 100% – ((amount of IFN-γ produced after exposure to 721.221-HLA-positive targets / amount of IFN-γ produced after exposure to 721.221-HLA-negative targets) X 100). The NK cells used in this assay were checked via flow cytometry using anti-CD158b antibody to ensure that similar levels of each KIR allelic product were expressed at the cell surface.

Molecular modeling

A structural model of KIR2DL3*005 was based on the x-ray structure of KIR2DL3*001 (Brookhaven Protein Data Bank (PDB): 1B6U)(35). KIR2DL3*005 was energy minimized using the consistent valence force field (CFF91) AMBER 10.0 simulation package (43). The cutoff for nonbonded interaction energies was set to ∞ (no cutoff); other parameters were set to default. To avoid unrealistic movements of the protein caused by computational artifacts, the structures were relaxed gradually. The dielectric constant was set at ε = 4 to account for the dielectric shielding found in proteins. The minimization was conducted in two steps: first using steepest descent minimization for 500 cycles and then using conjugate gradient minimization until the average gradient fell below 0.01 kcal/mol.

Molecular dynamics (MD)

Using the energy-minimized structure of KIR2DL3*005 as the initial model, 3 ns MD simulations with a distant-dependent dielectric constant were conducted by using the SANDER module of the AMBER 10.0 simulation package (43) with the PARM98 force-field parameter. MD simulations were performed using 0.001 picosecond time steps with temperature set at 300°K. The SHAKE algorithm (44) was utilized to keep all bonds involving hydrogen atoms rigid. Temperature and pressure coupling algorithms (45) were used to maintain constant temperature and pressure. Electrostatic interactions were calculated with the Ewald particle mesh method (46), and a dielectric constant at 1Rij and a nonbonded cutoff of 12 Å was used to the approximate electrostatic interactions and van der Waals interactions. Structural analyses were done using the SYBYL X (Tripos International, St. Louis, MO, USA) molecular modeling program.

Hinge angle calculation

The axes of the KIR D1 and D2 domains were bounded by residues 4 through 103 and 107 through 200, respectively as described by Boyington et al. (47). Using helical correction, Chimera 1.7 (48) anchored each axis at the centroid of these atomic coordinates. The axes were defined by the backbone atoms N, α-C, and carbonyl C. The calculated hinge angles between the D1 and D2 domains represent the crossing angle between vectors representing the two axes for each respective KIR allelic product.

Results

KIR2DL3*005 is present within the European American and African American populations

Of 76 random European Americans, 37 (48.7%) were positive for KIR2DL2 and 69 (90.8%) for KIR2DL3 by locus specific amplification. These frequencies are similar to previous observations made in a population of European ancestry (47% and 90%, respectively)(49). Of 100 random African Americans, 55 (55%) were positive for KIR2DL2 and 87 (87%) for KIR2DL3. In European Americans, four alleles, KIR2DL3*00101 (38.2%), KIR2DL3*002 (26.3%), KIR2DL2*00301 (15.1%), and KIR2DL2*00101 (14.5%), account for over 94% of the allele frequency. By contrast, African Americans are more diverse with the four most frequent alleles, KIR2DL3*00101 (41.5%), KIR2DL2*00101 (19%), KIR2DL3*005 (7.5%), and KIR2DL2*00602 (7.5%), accounting for only 76% of the allele frequency (Supplemental Table 1). Finally, there were no significant deviations from Hardy-Weinberg proportions for the KIR2DL2/3 locus in European and African American populations (p-values=0.4069 and 0.9879, respectively).

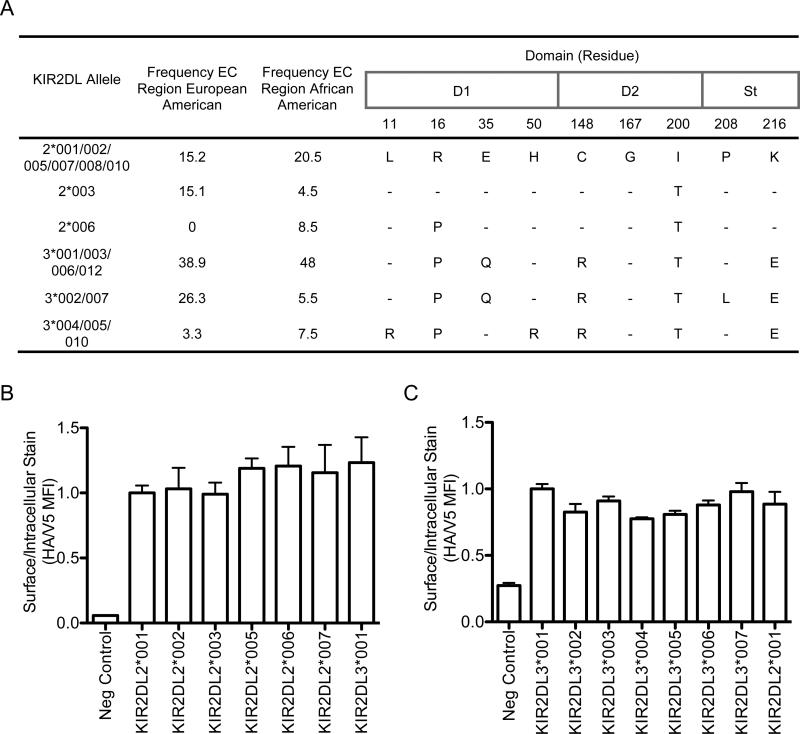

In spite of allelic variation, many KIR2DL2/3 receptors share the amino acid sequences of their extracellular regions and likely share their specificity and affinity for their ligand, HLA-C. For example, KIR2LD2*002, *005, and *007, share their extracellular sequences with KIR2DL2*001. When this is evaluated, only five (European American) or six (African American) polypeptide sequences predominate—accounting for 99% or 95%, respectively, of alleles in this locus (Fig. 1A).

FIGURE 1.

Allelic variants of KIR2DL2/3 are expressed at similar levels on the cell surface. A, Amino acid polymorphism of the extracellular region of the most common KIR2DL2/3 allelic products. The region is divided into: D1 = Ig-like domain 1, D2 = Ig-like domain 2, and St = stem (35, 47). Several allelic products share the same amino acid sequence of the extracellular domain. The frequencies of each extracellular amino acid sequence were derived from random populations of African Americans (n = 100) and European Americans (n = 76) (Supplemental Table 1). B and C, 18 hours post-transfection, NKL cells expressing KIR2DL2/3 allelic products containing N-terminal HA and C-terminal V5 tags were analyzed by flow cytometry. Cells were surface stained using anti-HA antibody and intracellularly stained using anti-V5 antibody. Relative fluorescence ratios indicating surface/intracellular MFI were normalized to HA-KIR2DL2*001 (B) and HA-KIR2DL3*001 (C). KIR2DL2*002 (B) and KIR2DL3*001 (C) without HA tags served as the negative controls. ANOVA analysis (one way, Kruskal-Wallis test) indicated that there were no significant differences in surface expression among these KIR allelic products. The assay was performed in triplicate, with error bars representing standard deviation of the mean. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Frequent KIR2DL2/2DL3 allelic products are expressed on the NK cell surface

The surface expression of 13 full length KIR2DL2/3 allelic products tagged with N-terminal HA and C-terminal V5, including the most frequent alleles in the population study, was determined by transient transfection of the KIR-negative NKL cell line. Eighteen hours post-transfection, cells were stained with an antibody specific for HA, and, following cell permeabilization, intracellularly stained for the KIR C-terminal V5 tag. Subsequent flow cytometry analysis of three independent experiments performed in triplicate demonstrated that all allelic products, when driven by the EF-1α promoter in the DEST51 vector, were expressed at similar levels on the NK cell surface (Fig. 1B and 1C). Two additional assays—flow cytometry analysis of V5 tagged KIR lacking an HA tag and detected with a moab specific for KIR2DL2/3 (anti-CD158b) as well as cell surface biotinylation followed by gel electrophoresis of KIR proteins—confirmed these findings (data not shown). Thus, with the exception of KIR2DL2*004 which is not expressed at the cell surface (26), the most frequent KIR2DL2/3 allelic products all appear to share the same general level of cell surface expression when driven by the same promoter. However, the protein expression levels of these KIR alleles in vivo, and hence concentration at the cell surface, may vary due to polymorphism within the proximal and distal promoter regions (50).

Surface plasmon resonance reveals that sKIR2DL3*005 binds HLA-C*03:04 tetramers with high affinity and similar kinetics as sKIR2DL2 allelic products

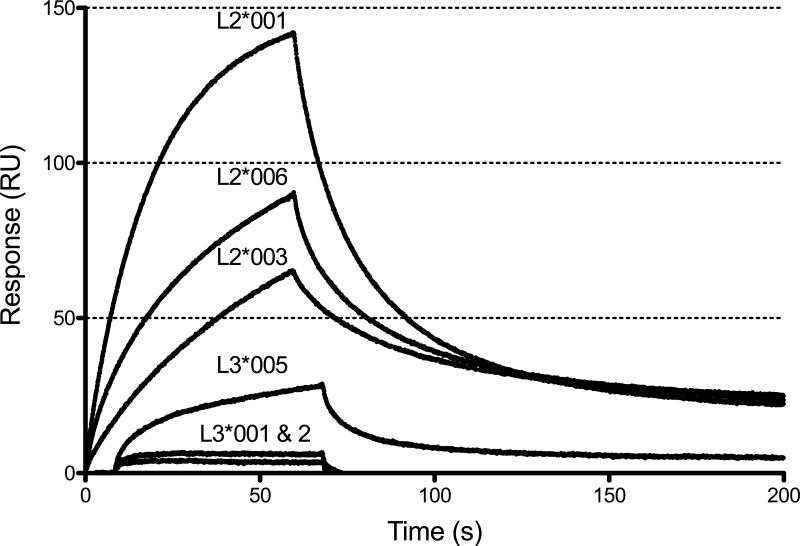

To assess the role of the KIR extracellular regions in ligand binding, the interaction of soluble KIR2DL2/3 Fc fusion proteins with an HLA-C ligand was assessed using Biacore technology. As expected (27), sKIR2DL2*001 demonstrated high avidity binding (142 peak resonance units (RU)) when injected over the immobilized HLA-C*03:04 (group 1) ligand (Fig. 2). The remaining KIR2DL2 allelic products, L2*003 (65 RU) and *006 (91 RU), also exhibited high avidity. Both sKIR2DL3*001 and *002 yielded substantially lower avidity, with peak RU of 7 and 4, respectively; the former in agreement with published data (18). Of note, sKIR2DL3*005 demonstrated a peak RU value of 29, with dissociation and association rates similar to that of the sKIR2DL2 allelic products, suggesting that this allelic product may behave more like KIR2DL2 than KIR2DL3. The interactions between sKIR fusion proteins and HLA-C*03:04 tetramers were consistent over a range of analyte concentrations (Supplemental Fig. 1).

FIGURE 2.

sKIR2DL3*005 binds immobilized HLA-C*03:04 tetramers with higher affinity than sKIR2DL3*001 and *002. Shown are surface plasmon resonance binding response curves of six sKIR analytes at 240 nM and immobilized HLA-C*03:04 tetramers (bound to a Biacore CM5 chip at ~2000RU). The sKIR fusion proteins were injected over the chip for 60 sec at 20 μl/min and dissociation kinetics were measured for > 200 sec. Each sKIR allelic product was analyzed in triplicate and the data are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Additionally, a low binding HLA-C group 2 ligand, HLA-C*06:02 (51), was tested in order to evaluate any differences in binding kinetics between the six sKIR and a low affinity ligand. All sKIR variants bound HLA-C*06:02 tetramers with very low avidity with an average peak of approximately 6 RU (data not shown). Due to a poor fit between the raw sensorgram data and the two state reaction model, binding kinetics calculations were unreliable for this HLA-C ligand and are therefore not reported.

Further analysis of the Biacore association (ka) and dissociation rates (kd), as well as the dissociation constant (KD), for each sKIR reveals a pattern of binding that defines two distinct groups of KIR in terms of kinetics (ka and kd) and affinity (KD). sKIR2DL2*001, *003, *006 and sKIR2DL3*005 can be categorized as high affinity KIR in terms of their binding to HLA-C*03:04, demonstrating KD values ranging from 1.5×10-8 M to 3.6×10-8 M (Table 1). By contrast, sKIR2DL3*001 and *002 bind HLA-C*03:04 with 10 to 100 fold lower affinity.

TABLE I.

Comparison of affinity and avidity values for sKIR binding to HLA-C determined by Biacore and Luminex

| KIR | Biacore KDa | Luminex Kdb | Luminex Bmaxc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand: HLA-C*03:04 | |||

| 2DL2*001 | 1.7 × 10-8 M | 2.0 × 10-7 M | 15741 |

| 2DL2*003 | 1.5 × 10-8 M | 7.0 × 10-7 M | 21034 |

| 2DL2*006 | 3.6 × 10-8 M | 9.1 × 10-8 M | 15041 |

| 2DL3*001 | 2.9 × 10-7 M | 1.0 × 10-6 M | 10827 |

| 2DL3*002 | 5.6 × 10-6 M | 1.2 × 10-6 M | 9141 |

| 2DL3*005 | 3.0 × 10-8 M | 1.0 × 10-7 M | 15042 |

| Ligand: HLA-C*06:02 | |||

| 2DL2*001 | NDd | 4.8 × 10-6 M | AMBe |

| 2DL2*003 | ND | 2.4 × 10-5 M | AMB |

| 2DL2*006 | ND | 4.3 × 10-6 M | AMB |

| 2DL3*001 | ND | AMB | AMB |

| 2DL3*002 | ND | AMB | AMB |

| 2DL3*005 | ND | 7.0 × 10-6 M | AMB |

KD, equilibrium constant (Kd / Ka, or off-rate / on-rate) calculated by 1:1 binding mathematical model. As the Biacore data uses a different form of the HLA-C ligand and is a function of analyte binding over time, these data cannot be directly compared to the Luminex Kd values.

Kd, dissociation constant denoting the concentration of sKIR required to reach half-maximal MFI

Bmax, maximum MFI calculated by nonlinear regression

ND, binding not detected

AMB, ambiguous data (as determined by Prism software)

sKIR2DL3*005 binds a panel of HLA-C group 1 allotypes with high avidity and group 2 allotypes with an intermediate avidity

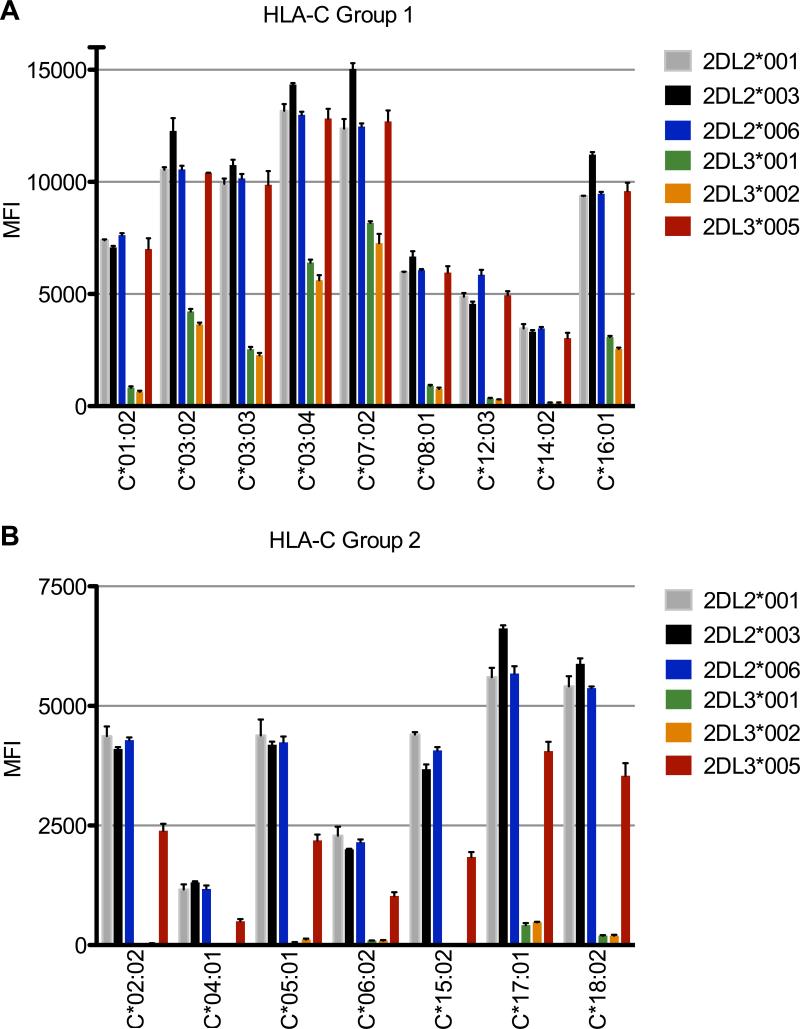

Binding of sKIR2DL2/3 Fc fusion proteins to a panel of 100 HLA class I allelic products in a solid phase assay was assessed to determine binding avidity and specificity. In all cases, sKIR bound to HLA-C group 1 ligands in a Luminex system with similar avidities as to the HLA-C*03:04 tetramers in the Biacore assay system. Specifically, all sKIR2DL2 (*001, 003, *006) and sKIR2DL3*005 bound with high avidity (measured by MFI values), in contrast to sKIR2DL3*001 and *002, which bound with intermediate to low avidity, respectively (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, although many HLA-C group 1 molecules (e.g., HLA-C*03:04, *07:02) demonstrated strong binding with the sKIR2DL2 and L3*005 allelic products, some group 1 molecules revealed lower binding avidity to these sKIR (e.g., HLA-C*12:03, *14:02). The pattern of binding among the sKIR allelic products did not substantially vary from HLA allotype to allotype although the levels of avidity between individual HLA allotypes was variable. This pattern was conserved from assay to assay and among different lots of HLA-bearing beads.

FIGURE 3.

KIR2DL3*005 binds HLA-C group 1 allelic products with high avidity and group 2 allelic products with an intermediate avidity. A, Binding of 100 μg/ml sKIR to a panel of nine HLA-C group 1 allotypes. B, Binding of 100 μg/ml sKIR to a panel of seven HLA-C group 2 allotypes. The MFI values for each sKIR-HLA interaction were adjusted for the beads’ HLA content and normalized to the HLA content of the HLA-C*01:02 beads using the pan-HLA class I antibody W6/32. The assay was analyzed in triplicate, with error bars representing standard deviation of the mean. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments.

As with HLA-C group 1, binding of the sKIR variants to group 2 HLA-C yielded a similar binding pattern, as sKIR2DL2 variants bound with high avidity and sKIR2DL3 variants bound with low. Notably, sKIR2DL3*005 bound with an intermediate avidity (yielding ~50% lower MFI values than the sKIR2DL2 fusion proteins across all group 2 molecules) (Fig. 3B). Due to poor sKIR binding to the HLA-C*06:02 tetramer in the surface plasmon resonance assay system, a direct comparison between the Luminex and Biacore data was not possible. Further, as with group 1, binding of sKIR to specific group 2 molecules demonstrated notable variation, with HLA-C*17:01 demonstrating the highest avidity and C*04:01 exhibiting the lowest. As with group 1, the pattern of binding among the sKIR products did not vary from HLA allotype to allotype although the levels of avidity between HLA allotypes was variable (Fig. 3B).

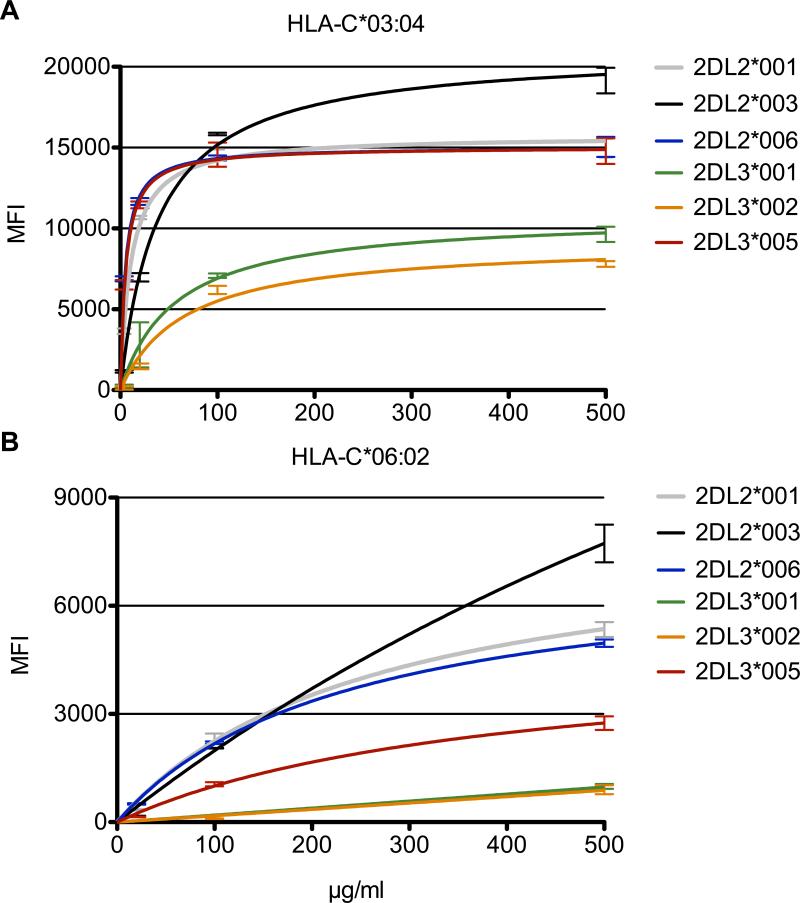

In order to demonstrate that sKIR retains specific binding across a range of concentrations, each recombinant protein was titrated from 4, 20, 100, and finally to 500 μg/ml. As the sKIR concentration was increased, interaction with HLA-C group 1 predictably yielded higher levels of binding (Fig. 4A). The resulting saturation binding curves demonstrate specific and scalable binding of all sKIR variants to their group 1 ligands. The calculated equilibrium dissociation constants (Kd), denoting the concentration at which 50% of the HLA binding sites are saturated, ranged from 5.03 μg/ml (9.1 × 10-8 M) for KIR2DL2*006 to 65.99 μg/ml (1.2 × 10-6 M) for KIR2DL3*002 (Table I). As expected, KIR2DL3*005 demonstrated a Kd value of 5.50 μg/ml (1.0 × 10-7 M), similar to the high avidity KIR2DL2 allelic products. Moreover, the calculated maximum plateau MFI value, or Bmax, ranged from 21034 for KIR2DL2*003 to 9141 for KIR2DL3*002 (Table I). KIR2DL3*005 predictably exhibited a Bmax that was comparable to the high avidity KIR2DL2 allelic products. Close inspection of the MFI values for KIR2DL2*003 at the 4 and 20 μg/ml concentrations demonstrated an avidity that lagged behind that of the other high binding KIR, therefore explaining the higher calculated Kd value (38.68 μg/ml or 7.0 × 10-7 M) for this particular sKIR (Supplemental Fig. 2A). The remaining group 1 HLA molecules demonstrated similar saturation binding curves, indicating that all tested allelic products from this group yield specific binding to sKIR (data not shown).

FIGURE 4.

Saturation binding curves indicate that KIR2DL3*005 and KIR2DL2 allelic products bind HLA-C group 1 with similar mass-action kinetics in a Luminex assay. A and B, Titration from 4 to 500 μg/ml sKIR yields equilibrium state binding of these allelic products to HLA-C*03:04 (group 1) and C*06:02 (group 2), respectively. Each assay was performed in triplicate, with error bars representing standard deviation of the mean. Data are representative of nine HLA-C group 1 (A) and seven HLA-C group 2 (B) allotypes and of at least three independent experiments.

Similar to the group 1 HLA data, group 2 molecules demonstrated scalable binding as the concentration of sKIR was titrated from 4, 20, 100, and finally to 500 μg/ml (Fig. 4B). Notably, all sKIR failed to approach binding saturation at the 500 μg/ml concentration. The calculated saturation binding curves for each sKIR yielded Kd values ranging from 236.1 μg/ml (4.3 × 10-6 M) to 1320 μg/ml (2.4 × 10-5 M), with KIR2DL3*005 demonstrating an avidity of 386.7 μg/ml (7.0 × 10-6 M) (Table I). Note that the Kd values for KIR2DL3*001 and KIR2DL3*002 are not reported as the calculated values were ambiguous due to the low levels of binding that these particular sKIR demonstrated. In fact, no binding was observed for any sKIR at the 4 μg/ml concentration (after background subtraction of the negative control bead MFI value) and very low binding (≤500 MFI) at the 20 μg/ml concentration for KIR2DL2*001, 2DL2*003, 2DL2*006, and 2DL3*005 (Supplemental Fig. 2B). Furthermore, Bmax values are not reported as the tested sKIR concentrations failed to approach a saturation point with respect to HLA-C group 2 binding. The remaining group 2 HLA molecules demonstrated similar saturation binding curves, again indicating that all tested allelic products from this group yield specific binding to sKIR (data not shown).

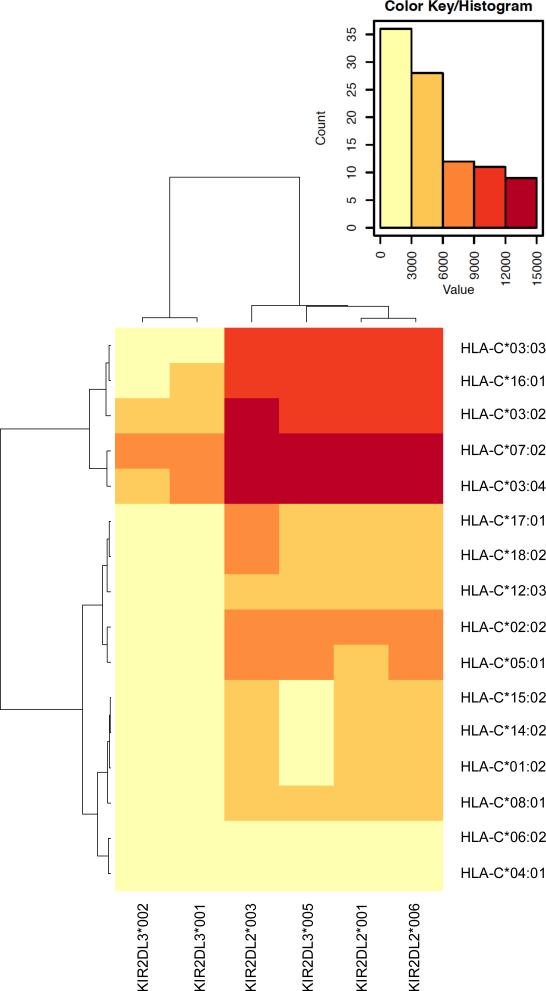

Using the Luminex sKIR binding data, a KIR and HLA-clustered heat map was generated depicting the avidity of each sKIR at 100 μg/ml with their group 1 and 2 ligands (Fig. 5). Here, the clustering algorithm groups sKIR2DL3*005 with the 2DL2 molecules, aligning this allelic product most closely with KIR2DL2*001 and *006. Furthermore, clustering the heat map with respect to HLA-C avidity yields two distinct groups that are not strictly defined by the classical group 1 and 2 designations based on amino acid residues at positions 77 and 80 of the HLA-C molecule. Notably, group 1 ligands HLA-C*01:02, *08:01, *12:03, and *14:02 cluster with group 2 molecules. As these group 1 molecules demonstrate an intermediate (KIR2DL2*001, *003, *006 and 2DL3*005) to low (KIR2DL3*001 and *002) avidity for sKIR, the clustering algorithm sorted these ligands with the group 2 molecules.

FIGURE 5.

Two-dimensional hierarchical clustering of KIR and HLA-C binding avidity redefines traditional groupings based solely on amino acid sequence. The color gradient represents the range of MFI values obtained by the Luminex assay, with dark red symbolizing the highest avidity (12,000-15,000 MFI) and pale yellow the lowest avidity (0-3000 MFI). sKIR at 100 μg/ml and HLA-C allelic products were clustered according to their binding avidity. Clustering analysis is representative of at least three independent runs, each with 100 bootstrap iterations.

IFNγ production indicates that KIR2DL3*005 behaves similarly to KIR2DL2*001

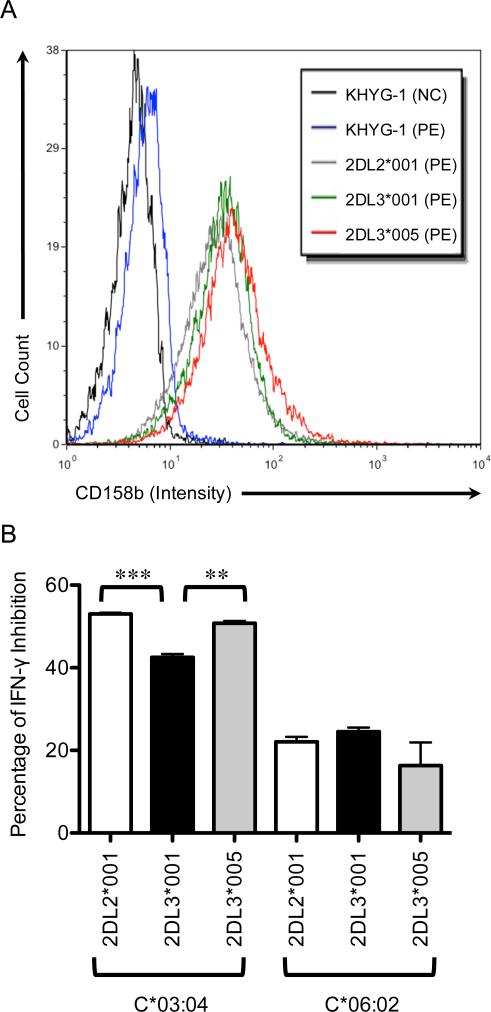

In order to determine the functional relevance of KIR2DL3*005's increased affinity and avidity for HLA-C, IFNγ production was assayed. Following transient transduction of KHYG-1 cells with lentiviral vectors to express the KIR2DL2*001, 2DL3*001, or 2DL3*005 extracellular regions fused to the KIR2DL2*001 intracellular region, these NK cells were co-incubated with parental 721.221 cells as well as cells expressing HLA-C*03:04 or HLA-C*06:02. The measured levels of IFNγ in the cell culture supernatant reflected a pattern of cytokine production that correlates with the observed affinity and avidity differences demonstrated by the sKIR fusion proteins (Fig. 6). Specifically, the IFNγ production by the high affinity/avidity KIR (2DL2*001 and 2DL3*005) demonstrates a 53% and 51%, respectively, decrease in this cytokine's production when engaged by 721.221 targets expressing HLA-C*03:04 (group 1) compared to the levels secreted when these NK cells were exposed to HLA-negative 721.221 cells. In contrast, KHYG-1 cells transduced with the low affinity/avidity KIR2DL3*001 yielded a smaller (42%) decrease in IFNγ synthesis relative to the HLA-negative control. The levels of IFNγ inhibition generated by KIR2DL2*001 and 2DL3*005 were significantly lower than the levels generated by 2DL3*001 cells upon exposure to 721.221-HLA-C*03:04 targets (Fig. 6B; 53% ± 0.30 vs 42% ± 0.82; p = 0.0003; by two-tailed t test; and 51% ± 0.57 vs 42% ± 0.82; p = 0.0012; by two-tailed t test). The lower affinity ligand HLA-C*06:02 triggered a less robust inhibitory response, yielding IFNγ decreases of 22%, 25%, and 16% for KHYG-1 cells expressing KIR2DL2*001, 2DL3*001, and 2DL3*005, respectively, verses their HLA-negative controls. Using the Student's t test, these values were not significantly different from one another. These patterns of inhibition were observed in 3 assays performed in triplicate.

FIGURE 6.

Analysis of IFN-γ levels in the culture supernatant indicates similar levels of HLA-C group 1-mediated inhibition in KHYG-1 cells expressing KIR2DL3*005 or KIR2DL2*001. A, Representative KIR surface expression levels of transiently transduced KHYG-1 cells with the indicated lentiviral vectors 18 hours after infection (NC = negative control, PE = stained with anti-CD158b-PE). B, The level of inhibition is expressed as the percent decrease of secreted IFN-γ by KHYG-1 cells transduced with either KIR2DL2*001, KIR2DL3*001, or KIR2DL3*005 after a 6 hour incubation with 721.221 HLA-negative targets (normalized to 100% IFN-γ secretion) compared to 721.221-HLA-C*03:04 (group 1) or C*06:02 (group 2) targets (by two-tailed t-test: **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). The assay was performed in triplicate, with error bars representing standard deviation of the mean. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Amino acid positions 11 and 35 act in concert to produce the KIR2DL3*005 phenotype

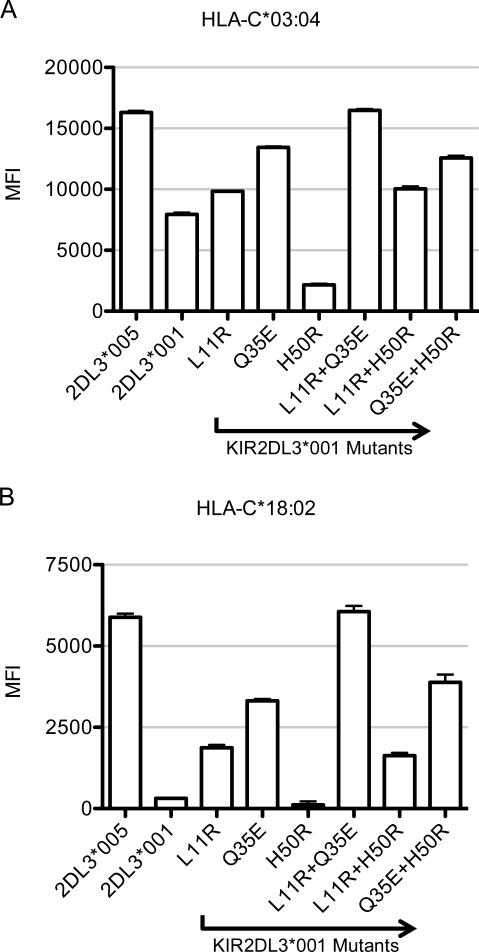

In order to determine the amino acid residues responsible for the observed KIR2DL3*005 phenotype, six additional sKIR were generated. Mutating the low binding KIR2DL3*001 towards residues found in the high binding KIR2DL3*005, each sKIR contained either a single or double amino acid change at residues 11, 35, and/or 50, the only three residues that differ between these allelic products (Fig. 1). The three single and three double sKIR mutants represent all possible intermediary polypeptide sequences between these two allelic products. Luminex analysis of KIR-HLA avidity revealed that single residue changes towards KIR2DL3*005 at positions 11 and 35 independently increased sKIR avidity for HLA-C allelic products. Specifically, L11R and Q35E result in 22.5% and 67.3% increases in avidity for HLA, respectively (representative group 1 and 2 HLA-C allelic products are shown (Fig. 7)). These results are in contrast to the H50R mutant, which demonstrated an unexpected 73.2% decrease in avidity compared to KIR2DL3*001. In fact, L11R or Q35E in combination with H50R appears to nullify the negative impact of the mutation at position 50, resulting in an avidity that is comparable to that of the single mutants at positions 11 and 35. Finally, investigation of the three possible combinations of double mutations revealed that the combination of residue changes at positions 11 and 35 yielded a complete rescue of the KIR2DL3*005 phenotype.

Figure 7.

Residues 11R and 35E synergize to yield the KIR2DL3*005 phenotype. A, Binding of 50 μg/ml sKIR to HLA-C*03:04 (HLA-C group 1) in a Luminex assay. B, Binding of 50 μg/ml sKIR to HLA-C*18:02 (HLA-C group 2). HLA-C*06:02 (group 2) is not shown because it exhibited extremely low MFI values; HLA-C*18:02 (group 2) more clearly demonstrates the impact of mutation on sKIR binding avidity. The MFI values for each sKIR-HLA interaction were adjusted for the beads’ HLA content and normalized to the HLA content of the HLA-C*01:02 beads using the pan-HLA class I antibody W6/32. The assay was performed in triplicate, with error bars representing standard deviation of the mean. Data are representative of nine HLA-C group 1 (A) and seven HLA-C group 2 (B) allotypes and of at least three independent experiments.

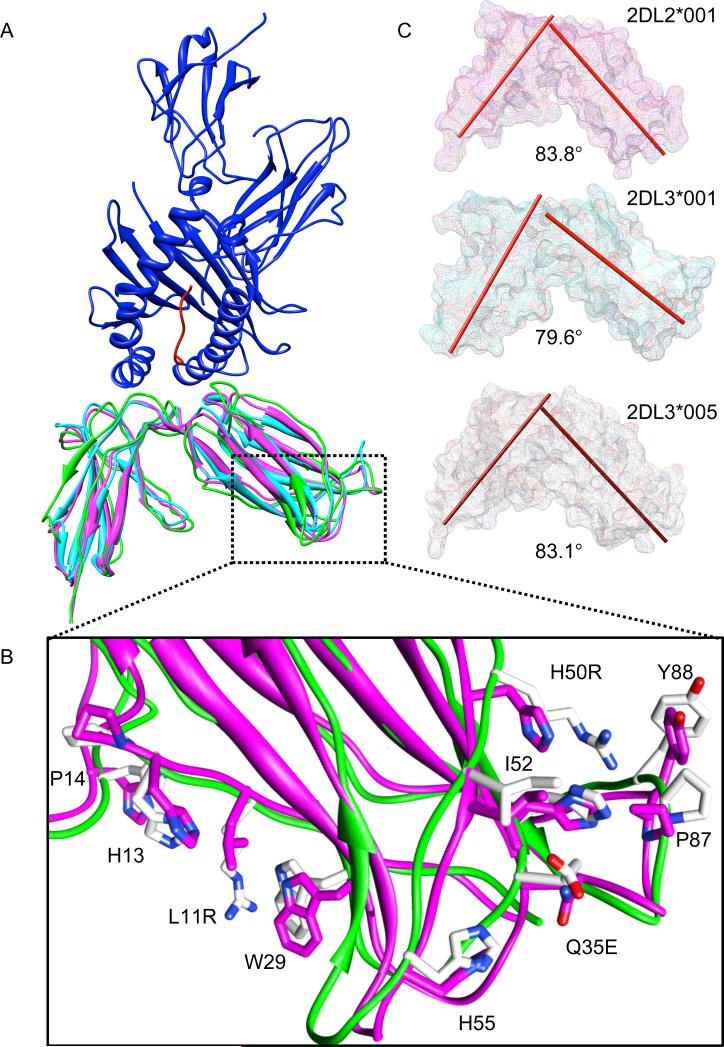

Molecular modeling predicts that polymorphism at positions 11, 35, and 50 in D1 alter the hinge angle between the two extracellular domains of KIR2DL3*005

Evidence that KIR2DL3*005 exhibits an unexpected reactivity with the KIR2DL1/S1-specific EB6B antibody (52) suggests that this allelic product has acquired an altered structure compared to other KIR2DL2/3 molecules. After confirmation of EB6B reactivity with sKIR2DL3*005 (data not shown), molecular modeling was employed in order to simulate structural alterations of the KIR2DL2/3 extracellular region induced by residue changes at positions 11, 35, and 50 (Fig. 8A and 8B). Comparison to the crystal structure of KIR2DL2*001 in complex with its HLA-C ligand (47) indicates that the substitutions present within the first extracellular domain of 2DL3*005 are distal to the KIR-HLA interface. Specifically, the three polymorphic positions are located on (residues 11, 50) or adjacent to (residue 35) β sheets and distant from the three loops shown to interact with the HLA-C ligand. Close inspection of the modeled KIR2DL3*005 molecule reveals a displacement of the HLA-binding loops (47, 53)) upon 3 ns of simulation when compared to the crystal structure of KIR2DL3*001 (35) (Fig 8A).

FIGURE 8.

Molecular modeling predicts that the interdomain hinge angle of KIR2DL3*005 is similar to that of KIR2DL2*001. A, Model of KIR2DL3*005 (green) generated from the crystal structure of KIR2DL3*001 (magenta, PDB ID: 1B6U), overlaid with KIR2DL2*001 co-crystalized with HLA-C*03:04 and the importin alpha-2 peptide (light blue, dark blue, and red, respectively, PDB ID: 1EFX). The simulated KIR2DL3*005 molecule reveals a shift of the HLA-binding loops when compared to KIR2DL3*001 (A'B (Loop 1, residues 20-23), CC’ (Loop 2, residues 43-46), and EF (Loop 3, residues 67-74). B, Molecular dynamics simulation after 3 ns indicates significant movement (>3Å RMSD) of polymorphic and adjacent residues in the D1 domain of KIR2DL3*005 (green) compared to KIR2DL3*001 (magenta). The two KIR differ only at residues 11, 35 and 50. C, The axes of the KIR D1 and D2 domains are defined by residues 4 through 103 and 107 through 200, respectively. The calculated hinge angles represent the crossing angle between the two axes for each respective KIR allelic product.

In fact, the structural fluctuations induced by these three polymorphic residues appear to resonate throughout the D1 domain of the simulated KIR2DL3*005 molecule, ultimately shifting the alignment of the two domains in relationship to one another. Since previous studies have suggested that the hinge angle of the two extracellular domains may impact their ability to bind to HLA-C (18), the simulated hinge angle between D1 and D2 of KIR2DL3*005 was evaluated. It measured 83.1°, in comparison to the hinge angles of 83.8° and 79.6° for the HLA-unligated crystal structures of KIR2DL2*001 and KIR2DL3*001, respectively (Fig. 8C). The calculated angles for the latter two KIR are consistent with those previously determined (18, 47, 54), with the larger angle found in the simulated KIR2DL3*005 similar to the high affinity KIR2DL2*001 molecule.

Discussion

Understanding the functional impact of allelic diversity at the KIR2DL2/3 locus will further elucidate the role that KIR2DL2/3 plays in human health and reproductive fitness and should aid in the design of strategies to apply that knowledge in the clinic. Here, we show that KIR2DL3*005 demonstrates unexpectedly high binding affinity and avidity with its HLA-C ligand. These data, along with functional analysis in the form of inhibition of IFN-γ production when cell surface ligand is detected, suggest that this KIR2DL3 allelic product behaves similarly to KIR2DL2 allelic products. As our population study indicates that one out of seven African Americans and one out of 15 European Americans carries this allele, its prevalence, especially in the former population, merits further investigation of its specific phenotype.

In the present study, two strategies were used to measure the binding affinity and avidity of KIR2DL2/3 allelic products to their HLA-C ligand. Surface plasmon resonance measured sKIR binding to two tetrameric bacterial expression system-produced HLA-C allotypes, each refolded with a single peptide. These data indicate that KIR2DL3*005 shares a kinetic profile similar to that of the high affinity KIR2DL2 allelic products (Table I). In terms of avidity, this assay revealed that the RUmax of KIR2DL3*005 was approximately 20-45% (compared to KIR2DL2*001 and KIR2DL2*003, respectively) of that achieved by the KIR2DL2 allelic products. By contrast, the low avidity KIR2DL3*001 and KIR2DL3*002 yielded RUmax values that were 5-11% and 3-6%, respectively, of that achieved by the KIR2DL2 allelic products. Under these conditions, our data yields KD values ranging from nanomolar to micromolar values for the high and low affinity KIR, respectively. While our findings cannot be directly compared to previously published KIR-HLA Biacore analyses due to differences in the assay components (bacterial expression system derived KIR and monomeric HLA-C were used in the earlier studies) (47, 51), the relationship between KIR2DL2*001 and KIR2DL3*001 is consistent with prior work (i.e., high versus low affinity) (18, 27).

To obtain a more biologically relevant and a more generalized interpretation of binding avidity of these KIR allelic products, a second strategy, the Luminex assay, was used to measure binding avidity and specificity. Here, the assay used polystyrene beads coated with single HLA allotypes produced in a human cell line. As these HLA molecules will carry a range of peptides, the data provide an average avidity level of specific KIR-HLA combinations. One can therefore infer that the avidity and affinity data presented here are applicable to the typical receptor-ligand interaction between these KIR and HLA-C at the cellular level. These data demonstrate that KIR2DL3*005 resembles other KIR2DL2 allelic products in terms of avidity for their HLA-C ligand. Lending further validity to our data, the relative avidity differences between KIR2DL2*001 and KIR2DL3*001 generated by our Luminex assay is comparable to previously published data (18, 37). Lastly, direct comparison of avidity among the high-binding KIR reveals subtle differences in the strength of binding for some allelic products (e.g., KIR2DL2*003 bound some group 1 allotypes with an avidity that was ~15% higher than other high avidity sKIR). Whether these small variations translate to functional differences remains to be evaluated.

Next, to augment the biological relevance of our affinity and avidity data, a cellular assay measuring NK inhibition in the presence of KIR2DL2/3 and their HLA-C ligands was used to measure the potential functional impact of KIR2DL3*005 ligand binding. Under ideal circumstances, the biological activity of a specific KIR allelic product is evaluated in peripheral blood NK cells. However, considering the complexities of the NK KIR repertoire, in both gene copy number and expression patterns, the difficulty in identifying a homozygous KIR2DL3*005 blood donor, and the impact of other inhibitory and stimulatory receptors on NK activity, we evaluated the functional activity of this KIR in a cell line-based assay system. While the limitations of the biological system used in the current study (i.e., a KIR-negative NK leukemia cell line and a transformed HLA class I-negative B cell line, both expressing high levels of transfected KIR and HLA-C, respectively) should be considered, the data generated by our study is likely reflective of the in vivo activity of these KIR in the context of their influence upon the immune response. Furthermore, by removing the potentially confounding variables of additional inhibitory signaling in our analysis (i.e., the lack of other inhibitory KIR in the effector cell line and the abrogation of HLA-E surface expression in the target cell line), our assay system allows for an examination of KIR2DL3*005's inhibitory capacity in isolation from other inhibitory molecules.

Although Falco et al. described a similar specificity of KIR2DL3*001 and *005 for HLA-C*03:03 (group 1) in a cellular assay (52), the avidity, specificity for other HLA-C allotypes, and a direct comparison of functional activity between these two allelic products was not reported. By our own analysis, KIR2DL2*001 and KIR2DL3*005 produced a similar down regulation of IFN-γ secretion in response to targets bearing HLA-C*03:04 (group 1). Additionally, these two high affinity KIR allotypes yielded significantly greater levels of IFN-γ inhibition compared to KIR2DL3*001. As expected based on the results of the binding affinity assays, target cells expressing HLA-C*06:02 (group 2) produced a less robust KIR inhibitory signal, down regulating the IFN-γ response by approximately 20%. The three KIR allelic products were not significantly different from one another when responding to a group 2 ligand, yielding a very subtle decrease in NK activity not strong enough to result in meaningful differences among the tested KIR allotypes if differences do indeed exist.

While the impact of polymorphism within the intracellular tails of these KIR was not evaluated, it has been demonstrated that residue changes between the cytoplasmic regions of KIR2DL2*001 and KIR2DL3*001 do not yield a significant difference in inhibitory signaling (18). Inspection of polymorphic residues within the cytoplasmic tails of KIR2DL3*002 and *005 reveal that these KIR possess only one alteration from KIR2DL3*001: the substitution of His for Arg at position 296. Not located within either of the two ITIMs of KIR2DL2/3, both amino acids are positively charged at physiological pH and possess similar hydropathy indexes. In the absence of experimental evidence, it is therefore reasonable to hypothesize that the presence of His at this position will have minimal, if any, effect upon the transduction of inhibitory signals. Considering this, the significant increase in affinity/avidity observed in the binding assays as well as the levels of inhibition of the IFN-γ response demonstrate that KIR2DL3*005, when triggered by HLA-C group 1 allotypes, should impact the immune response in a similar fashion as KIR2DL2.

Moesta and colleagues have demonstrated that the reduced binding avidity of KIR2DL3*001 compared to KIR2DL2*001 is the result of polymorphisms at residues 16 and 148. Surprisingly, these residues are distal to the HLA binding site yet likely impact the hinge angle and level of flexibility between the D1 and D2 domains (18). Likewise, KIR2DL3*005 differs from KIR2DL3*001 at residues (D1 domain positions 11, 35, and 50) that are located away from the KIR-HLA-C binding interface. In order to detect the relative contributions of polymorphic residues to the observed KIR2DL3*005 phenotype, we performed site directed mutagenesis altering the low avidity KIR2DL3*001 towards the high avidity 2DL3*005. This analysis revealed that the residues at positions 11 (L→R) and 35 (Q→E), in combination, provide a rescue effect in terms of avidity for KIR2DL3's cognate ligand. Molecular dynamics simulations suggest that these amino acid substitutions, acting in concert, induce structural changes that propagate throughout the KIR D1 domain, ultimately altering the orientation of the two external KIR domains in relation to one another. In agreement with Moesta and colleagues speculation that KIR2DL2*001's higher avidity for HLA-C is due to a more acute inter-domain hinge angle between D1 and D2 as compared to KIR2DL3*001 (18), the hinge angle of KIR2DL3*005 is similar to that of KIR2DL2*001. This structural modification could reposition KIR binding loops such that they form a more stable interaction with HLA-C—ultimately increasing the affinity and avidity of this receptor-ligand interaction.

Polymorphism may also influence KIR's ability to aggregate upon ligand binding. While it is predicted that KIR and HLA molecules bind with 1:1 stoichiometry, crystallographic studies of KIR2DL2/3 provide evidence of KIR oligomerization involving an interaction between the amino-terminal region of the D1 domain of one KIR with the carboxyl-terminal region of D2 of a second KIR (35, 47, 54). The crystals indicate that KIR dimerization appears to be mediated by hydrophobic interactions between domains, possibly involving the conserved residues Tyr80 and Tyr88 of D1. As Tyr88 is predicted to undergo a significant change in orientation in KIR2DL3*005 after 3ns of simulation (Fig. 8B), this may impact the ability of this allotype to successfully oligomerize and therefore alter binding to HLA-C. While the Luminex assay system was not designed to detect soluble KIR oligomerization, the increased (or decreased) ability of any of the tested allelic products and/or their mutants to aggregate across the HLA-coated bead surface through intermolecular domain linkage could result in measurable differences in avidity. As binding to anti-CD158a and anti-CD158b antibodies confirmed proper tertiary structure of the fusion protein, the near abrogation of binding demonstrated by the single mutant of KIR2DL3*001 at position 50 (H→R) could be the result of a disruption of the adjacent hydrophobic regions of D1 that are responsible for receptor aggregation. It is plausible that, without the supplemental effects of L11R and/or Q35E, the substitution at position 50 yields an effectively inactive receptor due to disrupted KIR oligomerization.

In addition to the impact of polymorphism upon an individual KIR allelic product's avidity for HLA-C, our analysis, as well as those of others (22, 55), reveals that each HLA-C allotype demonstrates a unique level of avidity for KIR2DL2/3. In fact, these findings indicate that HLA-C does not strictly follow the classical KIR avidity paradigm: not all group 1 allelic products are high avidity and, likewise, not all group 2 allelic products are extremely low avidity (Fig. 5B). Here, we demonstrate that HLA-C*01:02 and *08:01 (group 1) bind KIR2DL2/3 with an intermediate avidity; whereas, HLA-C*12:03 and *14:02 (group 1) bind with even lower avidities. The latter two group 1 allotypes yield avidities similar to group 2 ligands (only HLA-C*04:01 and *06:02 (group 2) demonstrate avidities that are substantially lower). While the observed differences in avidities could be the result of structural changes in regions of HLA-C that interact with the KIR2DL2/3 binding loops (47), it is also likely that variation in HLA-bound peptides plays a role. As KIR binding is sensitive to variation in positions 8 and, to a lesser extent, 7 of the peptide (47, 56) and since HLA-C allelic products demonstrate variation in their peptide content (57), the specific repertoire of HLA-C-bound peptides may influence the observed differences in avidities among these allotypes. Ultimately, when predicting the effect of particular KIR2DL2/3 and HLA-C allotypes upon the immune response, one must be mindful of the fact that certain HLA-C molecules do not fit within the classical relationship between HLA-C groups 1/2 and their affinity for KIR.

Considering the functional impact of variation in affinity and avidity between KIR2DL2/3 and HLA-C, it is likely that selective pressures in the form of endemic disease (58) and pregnancy disorders (59) influenced the relative frequencies of specific KIR polymorphisms. Furthermore, migration of early human populations almost certainly led to bottlenecking events (22), dramatically impacting the frequencies of specific KIR allelic products within these ancient populations. In order to establish the evolutionary significance of KIR2DL2/3 genetic diversity, this study defines the impact of allelic variation upon affinity and avidity for the HLA-C ligand of the most common allotypes present within modern African and European American populations. Such knowledge should provide critical insight into the KIR2DL2/3-controlled modulation of the immune response to infectious disease, malignancy, and pregnancy. Ultimately, these data may guide the course of clinical decision making, for example, as physicians tailor donor selection based on KIR/HLA combinations in the setting of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and NK cell adoptive transfer therapy (60).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted using the Tissue Culture and Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting Shared Resources of Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center. We thank Karen Creswell, Philip Posch, and Aykut Üren for excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

This research is supported by funding from the Office of Naval Research N00014-11-1-0590 and preceding ONR awards and from P30CA051008 from the National Cancer Institute.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, the National Institutes of Health or the U.S. government.

Abbreviations used in this paper: KIR, killer Ig-like receptor; D1, extracellular domain 1; D2, extracellular domain 2; 2DL, two extracellular domains with long cytoplasmic tail; MD, molecular dynamics.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Moretta L, Moretta A. Killer immunoglobulin-like receptors. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2004;16:626–633. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burshtyn DN, Scharenberg AM, Wagtmann N, Rajagopalan S, Berrada K, Yi T, Kinet JP, Long EO. Recruitment of tyrosine phosphatase HCP by the killer cell inhibitor receptor. Immunity. 1996;4:77–85. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80300-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell KS, Dessing M, Lopez-Botet M, Cella M, Colonna M. Tyrosine phosphorylation of a human killer inhibitory receptor recruits protein tyrosine phosphatase 1C. J. Exp. Med. 1996;184:93–100. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.1.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lanier LL, Corliss BC, Wu J, Leong C, Phillips JH. Immunoreceptor DAP12 bearing a tyrosine-based activation motif is involved in activating NK cells. Nature. 1998;391:703–707. doi: 10.1038/35642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uhrberg M, Valiante NM, Shum BP, Shilling HG, Lienert-Weidenbach K, Corliss B, Tyan D, Lanier LL, Parham P. Human diversity in killer cell inhibitory receptor genes. Immunity. 1997;7:753–763. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80394-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersson S, Fauriat C, Malmberg JA, Ljunggren HG, Malmberg KJ. KIR acquisition probabilities are independent of self-HLA class I ligands and increase with cellular KIR expression. Blood. 2009;114:95–104. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-184549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cichocki F, Miller JS, Anderson SK. Killer immunoglobulin-like receptor transcriptional regulation: a fascinating dance of multiple promoters. J. Innate. Immun. 2011;3:242–248. doi: 10.1159/000323929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lanier LL. NK cell recognition. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2005;23:225–274. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu J, Heller G, Chewning J, Kim S, Yokoyama WM, Hsu KC. Hierarchy of the human natural killer cell response is determined by class and quantity of inhibitory receptors for self-HLA-B and HLA-C ligands. J. Immunol. 2007;179:5977–5989. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.9.5977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lanier LL. Up on the tightrope: natural killer cell activation and inhibition. Nat. Immunol. 2008;9:495–502. doi: 10.1038/ni1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seliger B, Ritz U, Ferrone S. Molecular mechanisms of HLA class I antigen abnormalities following viral infection and transformation. Int. J. Cancer. 2006;118:129–138. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim S, Poursine-Laurent J, Truscott SM, Lybarger L, Song YJ, Yang L, French AR, Sunwoo JB, Lemieux S, Hansen TH, Yokoyama WM. Licensing of natural killer cells by host major histocompatibility complex class I molecules. Nature. 2005;436:709–713. doi: 10.1038/nature03847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim S, Sunwoo JB, Yang L, Choi T, Song YJ, French AR, Vlahiotis A, Piccirillo JF, Cella M, Colonna M, Mohanakumar T, Hsu KC, Dupont B, Yokoyama WM. HLA alleles determine differences in human natural killer cell responsiveness and potency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:3053–3058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712229105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Traherne JA, Martin M, Ward R, Ohashi M, Pellett F, Gladman D, Middleton D, Carrington M, Trowsdale J. Mechanisms of copy number variation and hybrid gene formation in the KIR immune gene complex. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010;19:737–751. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pyo CW, Guethlein LA, Vu Q, Wang R, Abi-Rached L, Norman PJ, Marsh SG, Miller JS, Parham P, Geraghty DE. Different patterns of evolution in the centromeric and telomeric regions of group A and B haplotypes of the human killer cell Ig-like receptor locus. PloS one. 2010;5:e15115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson MJ, Torkar M, Haude A, Milne S, Jones T, Sheer D, Beck S, Trowsdale J. Plasticity in the organization and sequences of human KIR/ILT gene families. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:4778–4783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.080588597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsu KC, Chida S, Geraghty DE, Dupont B. The killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) genomic region: gene-order, haplotypes and allelic polymorphism. Immunol. Rev. 2002;190:40–52. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2002.19004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moesta AK, Norman PJ, Yawata M, Yawata N, Gleimer M, Parham P. Synergistic polymorphism at two positions distal to the ligand-binding site makes KIR2DL2 a stronger receptor for HLA-C than KIR2DL3. J. Exp. Med. 2008;180:3969–3979. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.3969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mandelboim O, Reyburn HT, Vales-Gomez M, Pazmany L, Colonna M, Borsellino G, Strominger JL. Protection from lysis by natural killer cells of group 1 and 2 specificity is mediated by residue 80 in human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen C alleles and also occurs with empty major histocompatibility complex molecules. J. Exp. Med. 1996;184:913–922. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson J, Halliwell JA, McWilliam H, Lopez R, Marsh SG. IPD--the Immuno Polymorphism Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D1234–1240. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Single RM, Martin MP, Gao X, Meyer D, Yeager M, Kidd JR, Kidd KK, Carrington M. Global diversity and evidence for coevolution of KIR and HLA. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:1114–1119. doi: 10.1038/ng2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gendzekhadze K, Norman PJ, Abi-Rached L, Graef T, Moesta AK, Layrisse Z, Parham P. Co-evolution of KIR2DL3 with HLA-C in a human population retaining minimal essential diversity of KIR and HLA class I ligands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:18692–18697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906051106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carr WH, Pando MJ, Parham P. KIR3DL1 polymorphisms that affect NK cell inhibition by HLA-Bw4 ligand. J. Immunol. 2005;175:5222–5229. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.8.5222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lavender KJ, Chau HH, Kane KP. Distinctive interactions at multiple site 2 subsites by allele-specific rat and mouse ly49 determine functional binding and class I MHC specificity. J. Immunol. 2007;179:6856–6866. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.10.6856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jonsson AH, Yang L, Kim S, Taffner SM, Yokoyama WM. Effects of MHC class I alleles on licensing of Ly49A+ NK cells. J. Immunol. 184:3424–3432. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.VandenBussche CJ, Dakshanamurthy S, Posch PE, Hurley CK. A single polymorphism disrupts the killer Ig-like receptor 2DL2/2DL3 D1 domain. J. Immunol. 2006;177:5347–5357. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.5347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Winter CC, Gumperz JE, Parham P, Long EO, Wagtmann N. Direct binding and functional transfer of NK cell inhibitory receptors reveal novel patterns of HLA-C allotype recognition. J. Immunol. 1998;161:571–577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khakoo SI, Thio CL, Martin MP, Brooks CR, Gao X, Astemborski J, Cheng J, Goedert JJ, Vlahov D, Hilgartner M, Cox S, Little AM, Alexander GJ, Cramp ME, O'Brien SJ, Rosenberg WM, Thomas DL, Carrington M. HLA and NK cell inhibitory receptor genes in resolving hepatitis C virus infection. Science. 2004;305:872–874. doi: 10.1126/science.1097670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cooley S, Weisdorf DJ, Guethlein LA, Klein JP, Wang T, Le CT, Marsh SG, Geraghty D, Spellman S, Haagenson MD, Ladner M, Trachtenberg E, Parham P, Miller JS. Donor selection for natural killer cell receptor genes leads to superior survival after unrelated transplantation for acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2010;116:2411–2419. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-283051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chazara O, Xiong S, Moffett A. Maternal KIR and fetal HLA-C: a fine balance. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2011;90:703–716. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0511227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hou L, Chen M, Steiner N, Kariyawasam K, Ng J, Hurley CK. Killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIR) typing by DNA sequencing. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012;882:431–468. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-842-9_25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hou L, Chen M, Ng J, Hurley CK. Conserved KIR allele-level haplotypes are altered by microvariation in individuals with European ancestry. Genes Immun. 2012;13:47–58. doi: 10.1038/gene.2011.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guo SW, Thompson EA. Performing the exact test of Hardy-Weinberg proportion for multiple alleles. Biometrics. 1992;48:361–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.VandenBussche CJ, Mulrooney TJ, Frazier WR, Dakshanamurthy S, Hurley CK. Dramatically reduced surface expression of NK cell receptor KIR2DS3 is attributed to multiple residues throughout the molecule. Genes Immun. 2009;10:162–173. doi: 10.1038/gene.2008.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maenaka K, Juji T, Stuart DI, Jones EY. Crystal structure of the human p58 killer cell inhibitory receptor (KIR2DL3) specific for HLA-Cw3-related MHC class I. Structure. 1999;7:391–398. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sidney J, del Guercio MF, Southwood S, Engelhard VH, Appella E, Rammensee HG, Falk K, Rotzschke O, Takiguchi M, Kubo RT, et al. Several HLA alleles share overlapping peptide specificities. J. Immunol. 1995;154:247–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Graef T, Moesta AK, Norman PJ, Abi-Rached L, Vago L, Older Aguilar AM, Gleimer M, Hammond JA, Guethlein LA, Bushnell DA, Robinson PJ, Parham P. KIR2DS4 is a product of gene conversion with KIR3DL2 that introduced specificity for HLA-A*11 while diminishing avidity for HLA-C. J. Exp. Med. 2009;206:2557–2572. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neisig A, Melief CJ, Neefjes J. Reduced cell surface expression of HLA-C molecules correlates with restricted peptide binding and stable TAP interaction. J. Immunol. 1998;160:171–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.GraphPad Prism version 5.0f for Macintosh. GraphPad Software; La Jolla, California USA: [Google Scholar]

- 40.Team RC. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2.15.2 ed. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: [Google Scholar]

- 41.McQuitty LL. Similarity Analysis by Reciprocal Pairs for Discrete and Continuous Data. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1966;26:825–831. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fauriat C, Long EO, Ljunggren HG, Bryceson YT. Regulation of human NK-cell cytokine and chemokine production by target cell recognition. Blood. 2010;115:2167–2176. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-238469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Case DA,DTA, Cheatham TE, Simmerling CL, Wang J, Duke RE, Luo R, Merz KM, Pearlman DA, Crowley M, Walker RC, Zhang W, Wang B, Hayik S, Roitberg A, Seabra G, Wong KF, Paesani F, Wu X, Brozell S, Tsui V, Gohlke H, Yang L, Tan C, Mongan J, Hornak V, Cui G, Beroza P, Mathews DH, Schafmeister C, Ross WS, Kollman PA. AMBER 10. University of California; San Francisco: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sivanesan D, Rajnarayanan RV, Doherty J, Pattabiraman N. Insilico screening using flexible ligand binding pockets: a molecular dynamics-based approach. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2005;19:213–228. doi: 10.1007/s10822-005-4788-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Berendsen HJC, Postma JPM, van Gunsteren WF, DiNola A, Haak JR. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 1984;81:3684. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Darden T, York D, Pedersen L. Particle mesh Ewald: An N⊕log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:10089. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boyington JC, Motyka SA, Schuck P, Brooks AG, Sun PD. Crystal structure of an NK cell immunoglobulin-like receptor in complex with its class I MHC ligand. Nature. 2000;405:537–543. doi: 10.1038/35014520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Middleton D, Meenagh A, Gourraud PA. KIR haplotype content at the allele level in 77 Northern Irish families. Immunogenetics. 2007;59:145–158. doi: 10.1007/s00251-006-0181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cichocki F, Miller JS, Anderson SK. Killer immunoglobulin-like receptor transcriptional regulation: a fascinating dance of multiple promoters. Journal of innate immunity. 2011;3:242–248. doi: 10.1159/000323929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maenaka K, Juji T, Nakayama T, Wyer JR, Gao GF, Maenaka T, Zaccai NR, Kikuchi A, Yabe T, Tokunaga K, Tadokoro K, Stuart DI, Jones EY, van der Merwe PA. Killer cell immunoglobulin receptors and T cell receptors bind peptide-major histocompatibility complex class I with distinct thermodynamic and kinetic properties. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:28329–28334. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Falco M, Romeo E, Marcenaro S, Martini S, Vitale M, Bottino C, Mingari MC, Moretta L, Moretta A, Pende D. Combined Genotypic and Phenotypic Killer Cell Ig-Like Receptor Analyses Reveal KIR2DL3 Alleles Displaying Unexpected Monoclonal Antibody Reactivity: Identification of the Amino Acid Residues Critical for Staining. J. Immunol. 2010;185:433–441. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fan QR, Mosyak L, Winter CC, Wagtmann N, Long EO, Wiley DC. Structure of the inhibitory receptor for human natural killer cells resembles haematopoietic receptors. Nature. 1997;389:96–100. doi: 10.1038/38028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Snyder GA, Brooks AG, Sun PD. Crystal structure of the HLA-Cw3 allotype-specific killer cell inhibitory receptor KIR2DL2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:3864–3869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moesta AK, Graef T, Abi-Rached L, Older Aguilar AM, Guethlein LA, Parham P. Humans differ from other hominids in lacking an activating NK cell receptor that recognizes the C1 epitope of MHC class I. J. Immunol. 2010;185:4233–4237. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rajagopalan S, Long EO. The direct binding of a p58 killer cell inhibitory receptor to human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen (HLA)-Cw4 exhibits peptide selectivity. J. Exp. Med. 1997;185:1523–1528. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.8.1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Falk K, Rotzschke O, Grahovac B, Schendel D, Stevanovic S, Gnau V, Jung G, Strominger JL, Rammensee HG. Allele-specific peptide ligand motifs of HLA-C molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1993;90:12005–12009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.12005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carrington M, Martin MP. The impact of variation at the KIR gene cluster on human disease. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2006;298:225–257. doi: 10.1007/3-540-27743-9_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Trowsdale J, Moffett A. NK receptor interactions with MHC class I molecules in pregnancy. Semin. Immunol. 2008;20:317–320. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Murphy WJ, Parham P, Miller JS. NK cells--from bench to clinic. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18:S2–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.