Abstract

The autophagy response induced by HSV-1 infection is antagonized by the Beclin-binding domain (BBD). The purpose of this study was to determine if lack of the BBD affects viral spread and immune response in the eyes and brain. Our results showed that lack of the BBD increases autophagy response and activation of NLRP3 imflammasome, which in turn induces a more rapid innate immune response mediated by macrophage/microglia and NK cells in the injected eye, limiting virus replication and retinal damage. We conclude that autophagy plays a role in controlling HSV-1 infection by more rapid induction of the innate immune response.

Keywords: HSV-1, retinitis, autophagy, interferon, Beclin-binding domain

1. Introduction

Autophagy is a highly conserved mechanism for recycling cellular contents by delivering cytoplasmic material to the lysosome for degradation (Xie and Klionsky,2007; Yorimitsu et al., 2005). During autophagy, double-membrane vesicles form to sequester part of the cytoplasm. These double-membrane vesicles, also known as autophagosomes, subsequently fuse with lysosomes to form autolysosomes for the degradation of their contents for recycling. The major biological roles of autophagy relate to its ability to recycle nutrients and energy and to its ability to degrade unwanted cytoplasmic constituents (Xie and Klionsky,2007; Yorimitsu et al., 2005).

Autophagy also targets RNA and DNA viruses for sequestration and elimination (Talloczy et al., 2006; Levine at al., 2007). Autophagy may represent an important non-cytolytic mechanism for clearing viruses from neurons and thus promoting the survival of infected neurons. In addition, increasing evidence suggests that autophagy functions in innate and adaptive immunity (Paludan et al., 2005; Schmid et al., 2007). It has been demonstrated that autophagy may deliver both cytosolic and exogenous antigens to MHC class II molecules. For example, EBNA1 is processed intracellularly for MHC class II presentation to CD4+ T cells via autophagy in EBV transformed B cells and in EBNA1-transfected EBV-negative Hodgkin's lymphoma cells (Schmid et al., 2007). Lee et al. reported that recognition of certain single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) viruses by TLR7 requires transport of cytosolic viral replication intermediates into the lysosome by the process of autophagy (Lee et al., 2007). These investigators also found that autophagy was required for the production of interferon-alpha by plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) (Lee et al., 2007). Although autophagy was reported to be required for the production of IFN, other reports showed that both type I and II IFNs modulate autophagy (Orvedahl et al., 2008; Gutierrez et al., 2004; Singh et al., 2006). Restriction of HSV-1 infection by autophagy in vitro and in vivo was found to be dependent on the type I IFN-inducible double-stranded-RNA dependent protein kinase R (PKR) (Orvedahl et al., 2008). Type II IFN has been reported to enhance Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Ricksettia conorii degradation by macroautophagy in infected cells (Gutierrez et al., 2004; Singh et al., 2006).

HSV-1 inhibits autophagy through interaction with the essential autophagy-promoting protein Beclin 1 (Orvedahl et al., 2008; Kyei et al., 2009). Beclin 1 is the mammalian homolog of yeast Atg6 and is required for the formation of the autophagosome membrane through its interaction with VPS34, a class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (Kihara, et al., 2001; Liang et al., 1999). The N-terminal domain of ICP34.5, Beclin-binding domain (BBD), binds to Beclin 1 (ATG6) and inhibits its autophagic function (Orvedahl et al., 2008; Leib et al., 2009). BBD-deficient HSV-1 virus (lacking amino acids 68–87) behaves similarly to wild-type HSV-1 with respect to replication in cultured cell lines, antagonism of eIF2a phosphorylation and blockade of host cell shutoff. However, unlike the wild-type virus, this mutant virus fails to inhibit virus-induced autophagy in primary neurons, and mice infected with this mutant virus exhibit decreased CNS viral replication, fewer numbers of dead neurons and increased survival compared with mice infected with wild type virus (Orvedahl et al., 2008). Further experiments showed that BBD-deficient HSV-1 (Δ68H) stimulated a significantly stronger CD4+ T-cell-mediated delayed-type hypersensitivity response and resulted in significantly more production of gamma interferon and interleukin-2 from HSV-specific CD4+ T cells than its marker-rescued counterpart (Δ68HR) (Leib et al., 2009). Studies by English et al. showed that autophagy enhances the presentation of endogenous viral antigens on MHC class I molecules during in vitro HSV-1 infection and trigger a CD8+ T cell response (English et al., 2009).

Acute retinal necrosis (ARN) induced by herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) is a potentially blinding disease characterized by necrotizing retinitis, optic neuropathy, retinal arteritis, vitritis, and retinal vasculitis (Urayama et al., 1971; Duker et al., 1991). ARN can be unilateral or bilateral with involvement of the second eye occurring within a few months to as long as 34 years after onset of ARN in one eye (Falcone et al., 1993; Ezra et al., 1995; Schlingemann et al., 1996). A mouse model of ARN has previously been described and studied (Whittum et al., 1984; Vann et al., 1991; Bosem et al., 1990; Atherton et al., 2001). After inoculation of HSV-1 (KOS) into the anterior chamber (AC) of one eye, the virus spreads from the anterior segment of the injected eye via synaptically connected neurons and enters the optic nerve and retina of the uninjected contralateral eye by spreading from the ipsilateral SCN. Although the anterior segment of the inoculated eye is infected, the retina of this eye is spared. In contrast to KOS, inoculation of H129, a neurovirulent strain of HSV-1, is injected into the AC of BALB/c mice, the mice develop bilateral retinitis (Vann et al., 1991; Archin et al., 2002a; Archin et al., 2002b). After AC inoculation, H129 follows a pathway similar to KOS in the CNS, but H129 spreads more rapidly than KOS within the CNS, which in turn, allows virus to infect retino-recipient nuclei proximal to the contralateral and ipsilateral optic nerve early during infection (Archin et al., 2002a; Archin et al., 2002b). The purpose of this study was to determine if lack of the BBD affects viral ocular infection and spread of HSV-1 from the eyes to the brains after anterior chamber (AC) inoculation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Virus and Virus Titration

The original stocks of the ICP34.5 Beclin 1-binding mutant (Δ68H) and its marker rescued virus (Δ68HR) were a generous gift of Dr. David A. Leib (Leib et al., 2009). Stock virus was prepared by low multiplicity of infection (0.1 PFU/cell) passage in Vero cells grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone, Logan, UT) and antibiotics. The titer of the virus stock was determined by plaque assay on Vero cells (around 1 × 108 PFU/ml for both Δ68H and Δ68HR). Aliquots of stock virus were stored at −70°C, and a fresh aliquot was thawed and diluted for each experiment.

2.2. Mice

Adult (6–8 week old) female BALB/c mice (Taconic, Germantown, NY), were used in in vivo and in vitro experiments respectively. Mice were housed in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines. The treatment of animals in this study conformed to the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Medical College of Georgia, Georgia Health Sciences University. Mice were maintained on a 12 hour light cycle alternating with a 12 hour dark cycle and were given unrestricted access to food and water. They were anesthetized with 0.5 to 0.7 ml/kg of a mixture of 42.9 mg/ml ketamine, 8.57 mg/ml xylazine, and 1.43 mg/ml acepromazine before all experimental manipulations. Each group in each experiment had a minimum of four mice, and each experiment was repeated at least once.

2.3. Experimental Plan

Mice were anesthetized and the right eyes were inoculated with 1 × 104 PFU of BBD-deficient HSV-1 (Δ68H) or its marker rescued virus (Δ68HR) in a volume of 2 μL via the AC route as previously described (Archin et al., 2002a). Mock-injected mice were inoculated with 2 μL of uninfected Vero cell extract via the AC route. At various times after virus injection or mock injection, the mice were deeply anesthetized,the injected eyes, brains and uninjected eyes (four mice in each group at each time point) were removed, homogenized in serum-free tissue culture medium using a handheld tissue homogenizer (Biospec Products, Inc., Racine, WI) and plated on Vero cells for detection of replicating virus. Eyes and brains of additional mice were removed and prepared for flow cytometry, immunohistochemistry, PCR, or Western blot as described below.

2.4. Separation of ipsilateral Edinger–Westphal nucleus

The brain was placed in a rodent brain matrix (ASI Instruments, Warren, MI). Coronal sections containing both the ipsilateral and contralateral EW nucleus was cut from interaural -1.5 to 2 (Franklin KBJ and Paxinos G, 1997) using alcohol-sterilized disposable microtome blades (Accu-Edge blades, Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA). Each section was then sectioned in the midline and the right half (ipsilateral side) of each brain slice was harvested for flow cytometry or real time PCR as described below (pool of four brains in each group at each time point in each experiment).

2.5. Isolation of cells from the injected eyes for FACS

The injected eyes in 68H, 68HR infected mice or PBS injected control mice (four mice in each group at each time point) were harvested from day 1 to day 5 p.i. Single cell suspensions were prepared by grinding the tissues between frosted slides in 5 ml of cold Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) and teasing the ground tissue through a 60-mm nylon mesh. RBC were lysed by treatment with ammonium chloride lysis buffer (ACK); cells were washed three times in HBSS and resuspended in FACS buffer (PBS with 3% FBS) for flow cytometry as described below. The total recovered cells from each group (4 eyes) were counted under microscope.

2.6. Isolation of mononuclear cells from the brain

Brain sections containing the ipsilateral EW nucleus (EWN) were produced as described above and placed in 20 ml Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Single cell suspensions were made by grinding the tissues between frosted slides and repeated gentle pipetting of the ground material using fire-polished Pasteur pipettes. Cells were then washed, resuspended in 10 ml of a 70% gradient buffer, and mononuclear cells were separated on a Percoll gradient as described previously (Bulloch et al., 2008). Mononuclear cells from the 37/70 interphase were washed and resuspended in FACS buffer for flow cytometry as described below. The total recovered cells from each group were also counted under microscope.

2.7. Flow cytometry

Samples were incubated with FITC-anti-L3T4 (CD4) (BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA), FITC-anti-Ly-3.2 (CD8) (BD PharMingen), FITC-anti-mouse pan-NK (DX-5) (BD PharMingen), FITC-anti-Mac-1(BD PharMingen) or FITC-rat IgG2b,κ isotype control (BD PharMingen). After 30 minutes, cells were washed 3 times in FACS buffer and resuspended in FACS buffer for analysis. Large granular cells (predominately lymphocytes and macrophages) were included in the gate, and cell debris and small cells were excluded. In preliminary experiments, CD4, CD8, Mac-1 and DX5 staining was compared between anti-CD32/CD16 (Fc receptor block) treated samples and untreated samples. The samples were incubated with anti-CD32/CD16 (Fc receptor block, 1:40) (BD PharMingen) or FACS buffer as control for 15 min. Cells were then resuspended in FITC-anti-CD4, FITC anti-CD8, FITC anti Mac-1 or FITC-anti-DX-5 for 30 min (PharMingen). No difference was observed between Fc receptor blocked group and the unblocked control group.

Percent positive cells from the brain = % positive stained cells minus % positive cells from the same control sample. Because 3 to 4 times as many cells were recovered from HSV-1 injected eyes at day 4 and 5 pi than from control eyes or HSV-1 injected eyes at day 1 or day 2 p.i., the number of positive cells (instead of percent positive cells) was used to represent flow cytometry results in the eyes as follows: number of positive cells = Percent positive cells (% positive stained cells - % positive cells from the same control sample) × average recovered cells per eye (total recovered cells from 4 eyes/4).

2.8. Immunohistochemistry staining

The eyes and brains were embedded in OCT compound (Tissue-Tek; VWR Scientific, Houston, TX), snap frozen, and sectioned on a cryostat. Frozen sections were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes, washed with PBS and blocked with PBS containing 10% normal donkey serum, 2% BSA, and 0.5% Triton X-100, and incubated overnight at 4°C in goat anti-HSV-1 at a dilution of 1:2000 (Accurate Chemical and Scientific Corporation, Westbury, NY). The sections were washed and reacted with FITC-anti-goat (Jackson ImmunoResearch) at room temperature for 1 hour. The slides were washed, mounted with anti fade medium containing DAPI (Vectashield, Vector Laboratories) and examined microscopically.

2.9. Western Blot Analysis

Antibodies for Light Chain 3 (LC3) and caspase 1 were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA) and Millipore (Temecula, CA) respectively. Western blot analysis was performed as previously described (Zhang et al., 2008). Briefly, proteins were extracted from HSV-1-infected eyes, brains or control eyes and brains (four mice in each group at each time point). Equal amounts of protein were loaded for SDS-PAGE, followed by electroblotting onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). After being blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk for 1 hour at room temperature, the membrane was incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibody, and binding of HRP-conjugated secondary antibody was performed for 1 hour at room temperature. The immune complex was detected by a chemiluminescence detection system (ECL; GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) and exposure to x-ray film. To verify equal loading among lanes, the membrane was stained with the intrinsic protein β-actin after staining for primary antibody and with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. Each experiment was performed at least twice, and most were performed three times to ensure reproducibility.

2.10. Real time PCR

RNA was extracted from HSV-1-infected eyes, the ipsilateral EWN sections or control eyes and brain sections (four mice in each group at each time point) using PureLink™ RNA Mini Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Eighty four genes representing mouse anti-viral immune response were detected by real time PCR (ABI 7900 HT, Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, California) with RT2 Profiler™gene microarray kits from SABiosciences (Frederick, MD) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

3. Results

3.1. Retinal infection in BBD-deficient HSV-1 (Δ68H) and marker rescued HSV-1 (Δ68HR) infected mice

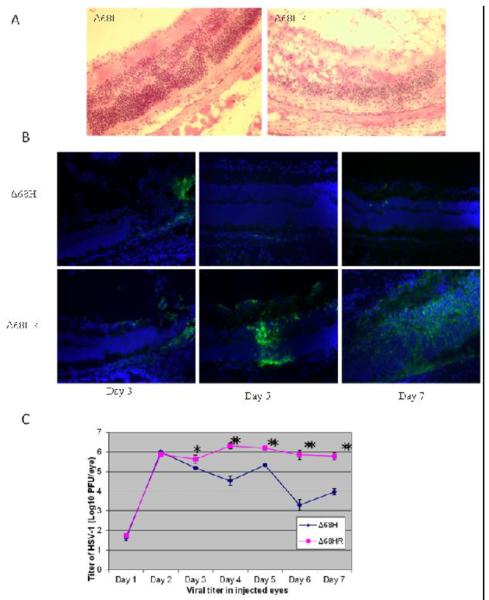

Bilateral retinitis was observed following uniocular AC inoculation of marker rescued virus (Δ68HR) (Figure 1A,1B). Spread of Δ68HR from the injected eye to the brain and both retinas was similar to that described previously in mice infected with H129, a highly neuroinvasive strains of HSV-1 (Archin et al., 2002a; Archin et al., 2002b). Virus was detected in the ipsilateral EW nucleus as early as day 3 p.i., and in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) at day 4 p.i. Both SCN were HSV-1 positive at day 5 in all mice (Figure 3A). In the uninjected contralateral eyes, a few HSV-1 positive cells were observed in the ganglion cell layer at day 5 p.i., and by day 6 p.i, many HSV-1 positive cells were observed in all layers of the retina. In the injected eyes, a few HSV-1 positive cells were observed in the ganglion cell layer at day 3 and day 4 p.i. (Figure 1B). By day 5 p.i., HSV-1 positive cells continued to be observed in the ganglion layer and some virus positive cells were also observed in the inner nuclear and outer nuclear layer and optic nerve (Figure 1B). Although the choroid and some RPE cells were also HSV-1 positive, the pattern of virus spread appeared to be similar to that seen in the uninjected eye (i.e., initial site of infection in the ganglion cell layer followed by spread to the inner and outer nuclear layers). At day 6 p.i., both the ipsilateral and contralateral retinas of 6 of 8 mice were HSV-1 positive, while in 2 of 8 mice, there appeared to be more virus in the retina of the injected eye than in the retina of the contralateral uninjected eye.

Figure 1.

Viral spread and replication in Δ68H and Δ68HR injected eyes.

(A) Photomicrographs of hematoxylin and eosin stained sections showing severe retinitis and retinal destruction at day 6 p.i. in Δ68HR injected eyes. Magnification: 316×. (B) Photomicrographs of merged staining for HSV-1 (green) and DAPI (blue) in the Δ68H injected eyes at day 3, 5, 7 p.i., Photomicrographs of merged HSV-1 and DAPI staining of Δ68HR injected eyes on day 3, 5, 7 p.i. are presented for comparison. The ganglion cell layer is toward the top in all photomicrographs. Widespread HSV-1 retinal infections was only observed in Δ68HR-injected eyes. Magnification: 316×. (C) Titer of HSV-1 (Log10 ± SEM PFU/mL) in the injected eyes of Δ68H infected mice and Δ68HR infected mice 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 days after inoculation of virus. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 (Student's t test).

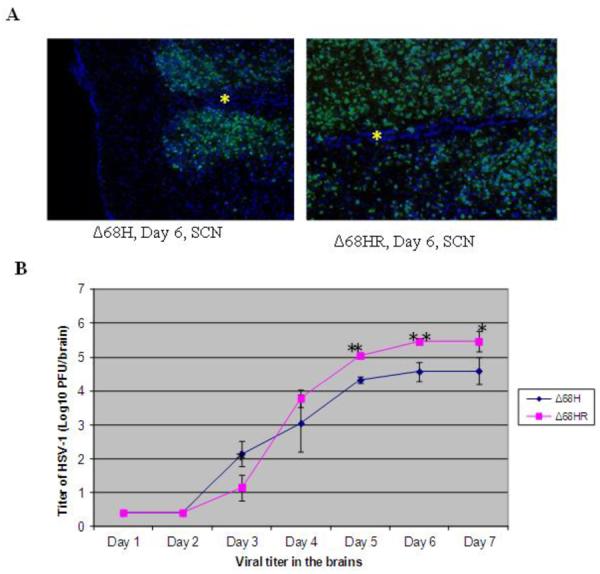

Figure 3.

Viral spread and replication in the brains of Δ68H and Δ68HR infected mice. (A) Photomicrographs of merged staining for HSV-1 (green) and DAPI (blue) in the SCN of a Δ68H infected mouse and a Δ68HR infected mouse. More HSV-1 positive cells were noted in Δ68HR infected mouse than in Δ68H infected mouse. The inferior aspect of the SCN is to the left in each photomicrograph and an asterisk indicates the midline of the brain. Magnification: 316×. (B)Titer of HSV-1 (Log10 ± SEM PFU/mL) in the brains of Δ68H infected mice and Δ68HR infected mice 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 days after inoculation of virus. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 (Student's t test)

In injected eyes, BBD deficient HSV-1 Δ68H replicated equivalently to marker rescued virus Δ68HR at day 1 and 2 p.i. However, by day 3 p.i. and continuing, significantly less replicating virus was recovered from Δ68H injected eyes than from Δ68HR injected eyes (Figure 1C) and widespread HSV-1 infection were not observed in Δ68H-injected eyes (Figure 1A, 1B). HSV-1 positive cells were only occasionally observed in the retina of Δ68H-injected eyes (Figure 1B). The extent of retinal damage, amount of inflammatory cell infiltrate, and disruption of the retinal architecture/retinal necrosis was greater in the Δ68HR-injected eyes than in the Δ68H injected eyes (Figure 1A).

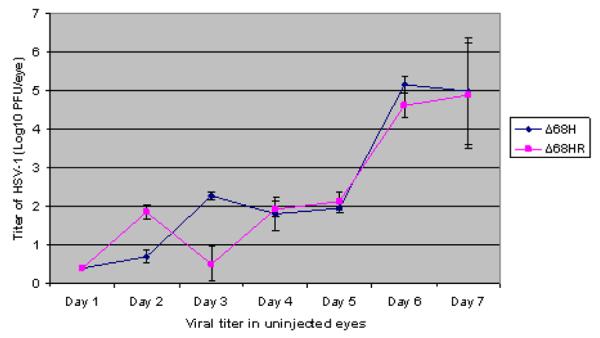

In the brain, the spread of HSV-1 Δ68H to EW and SCN was similar to HSV-1 Δ68HR. However, CNS infection and encephalitis were more severe in Δ68HR infected mice, and 17 of 20 mice infected with Δ68HR developed clinical signs of encephalitis, such as hunched posture, ataxia and weight loss beginning at day 6 p.i. and 5 of 14 mice died by day 7 p.i. In contrast, only 3 of 10 Δ68H infected mice had clinical signs of encephalitis, and all mice were alive at day 7 p.i. Significantly more replicating virus was also recovered from the brains of Δ68HR infected mice than from the brains of Δ68H infected mice beginning at day 5 p.i.(Figure 3B). More HSV-1 infected cells were observed in the SCN of 68HR infected mice than in the SCN of Δ 68H infected mice (Figure 3A). Similar to Δ68HR in the uninoculated eyes, many HSV-1 positive cells and retinitis were detected in the uninoculated contralateral eye of Δ68H infected mice beginning on day 6 p.i. (Figure 3B) and virus titers in the uninoculated eye were similar for both Δ68HR and Δ68H infected mice (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Titer of HSV-1 (Log10 ± SEM PFU/mL) in the contralateral eyes of Δ68H infected mice and Δ68HR infected mice 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 days after inoculation of virus.

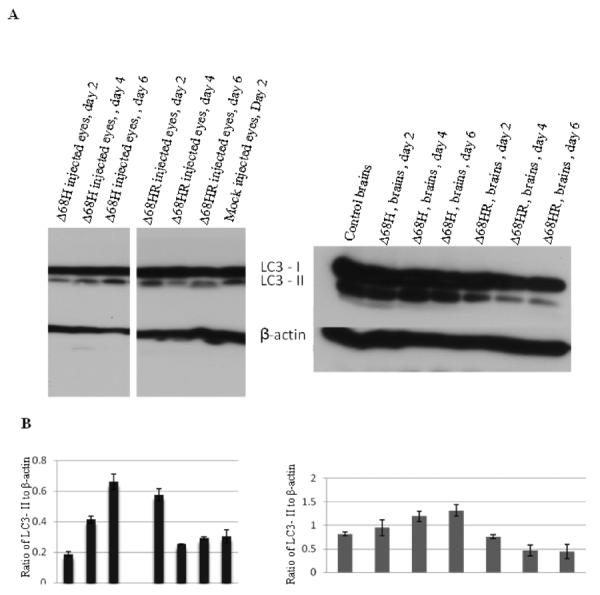

3.2. Lack of the BBD increases autophagy

Conversion of LC3-I to LC3 II is a sign of formation of autophagosome (Tasdemir et al., 2008) and western blot for LC3 protein is used to detect autophagy. To determine if autophagy response is affected by BBD deficiency, western blot was used to detect LC3 in the injected eyes and brains. As shown in Figure 4, at day 4 and day 6 p.i., the level of LC3- II was approximately 2 fold higher in Δ68H injected eyes than in Δ68HR injected eyes and mock injected control eyes. The level of LC3- II was approximately 3 fold higher in the brains of Δ68H infected mice than in Δ68HR infected mice at day 4 and day 6 p.i. The results confirm that lack of BBD increases autophagy response is the infected eyes and brains.

Figure 4.

(A) Western blot of LC3 in the injected eyes (left) and in the brains (right) of Δ68H infected mice and Δ68HR infected mice on days 2, 4 and 6 p.i. Proteins from the injected eyes and brains of mock infected mice were respectively used as the control. (B) Ratio of LC3- II to β-actin.

3.3. Viral immune response genes in the injected eyes and brain

Autophagy has been shown to promote antiviral immune responses such as interferon production and antigen presentation (Paludan et al., 2005; Schmid et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2007). To determine whether immune response genes were affected by lack of BBD, RNA was extracted from HSV-1-injected eyes and control eyes, and viral immune response genes were detected by real time PCR. There was no significant difference (less than 3 fold) in 41 genes between viral injected and medium injected eyes, whereas 43 genes were upregulated 3 fold or more in viral injected eyes at one or more time points (Table 1). Although many of these 43 genes were upregulated in both Δ68HR and Δ68H injected eyes, several were more upregulated in Δ68H injected eyes than in Δ68HR injected eyes. The imflammasome gene NLRP3 was more strongly expressed in Δ68H injected eyes compared to Δ68HR injected eyes from day 2 to day 4 p.i. In particular, at day 3 p.i., Δ68H injected eyes showed a 258 fold increase in NLRP3 expression compared to a 93 fold increase in Δ68HR injected eyes. IL6, which plays a pivotal role during the transition from innate to acquired immunity including attracting monocytes, skewing monocyte differentiation towards macrophages by upregulating M-CSF receptor expression and recruiting T cells (Scheller J et al., 2011), was 3.7 fold higher in Δ68H injected eyes than in Δ68HR injected eyes at day 3 p.i. In addition, CCL3, CCL4, CCL5 chemokines, which are produced predominantly by macrophages/microglia and which are responsible for recruitment of cells into sites of inflammation (Adler et al., 2005; Glass et al., 2003), were more upregulated in Δ68H injected eyes at several time points. At day 2 p.i., mRNA level of chemokines CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL11, potent chemoattractants for activated T-cells, NK cells, and monocytes which are produced by astrocytes and microglia in the central nervous system (Adler et al., 2005; Carter et al., 2007), were 3 or more fold higher in Δ68H injected eyes than in Δ68HR injected eyes. However, at day 3 and day 4 p.i. the levels of CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL11were similar in both virus infected groups (Table 1). Interleukin 12, which is produced by a variety of antigen presenting cells and enhances proliferation and cytolytic activities of NK cells and T cells (Becheret al., 2000; Lodoen et al., 2006), was higher in Δ68H injected eyes than in Δ68HR injected eyes. CD40, which is related to antigen-presentation and to activation of CD4+ T cells (O'Sullivan et al., 2003) and TRIM25 which mediates type I interferon induction (Gack et al., 2011) were also more upregulated in Δ68H injected eyes than in Δ68HR injected eyes at day 2 and day 3 p.i. Autophagy has been reported to be required for the production of IFN, our results showed that IFN-β was higher at day 2 p.i. in Δ68H injected eyes than in Δ68HR injected eyes. However, IFN-α2 mRNA was lower at day 3 p.i., in Δ68H injected eyes than in Δ68HR injected eyes.

Table 1.

43 upregulated immune response genes in Δ6SH (h) and Δ68HR(hr) injected eyes at day 2, day 3, day 4 p.i.

| Symbol | Δ68h-day2 | Δ68hr-day2 | Δ68h-day3 | Δ68hr-day3 | Δ68h-day4 | Δ68hr-day4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aim2 | 1.3663 | 0.8252 | 1.3416 | 2.1042 | 3.2125 | 4.5391 |

| Card9 | 1.2621 | 1.2885 | 2.7887 | 1.6977 | 3.3189 | 2.4464 |

| Casp1 | 3.4417 | 2.1317 | 21.4397 | 12.8702 | 21.7406 | 18.1852 |

| Ccl3 | 11.4722 | 5.2526 | 334.9357 | 218.0623 | 360.2878 | 177.6295 |

| Ccl4 | 17.9159 | 12.3712 | 506.0088 | 226.4567 | 399.7529 | 180.3084 |

| Ccl5 | 69.207 | 27.0244 | 221.6288 | 194.5871 | 159.9408 | 128.6201 |

| Cd40 | 7.6998 | 3.2685 | 23.0119 | 10.7793 | 23.6532 | 23.6189 |

| Cd80 | 2.6306 | 2.3196 | 22.2701 | 14.9703 | 15.5294 | 14.8633 |

| Cd86 | 1.8918 | 1.3991 | 10.5104 | 9.5155 | 6.4727 | 9.4161 |

| CtSS | 1.2645 | 1.2605 | 6.5972 | 3.4916 | 8.8366 | 8.2756 |

| Cxc110 | 945.7779 | 325.6381 | 802.7353 | 1081.13 | 611.9215 | 598.8441 |

| Cxc111 | 742.8173 | 266.0893 | 1124.098 | 1262.04 | 834.1591 | 771.3755 |

| Cxc19 | 111.6608 | 37.1237 | 320.3128 | 309.7842 | 390.055 | 331.7638 |

| Ddx58 | 12.2139 | 7.057 | 15.8538 | 15.0988 | 14.276 | 14.0642 |

| Dhx58 | 10.5862 | 5.8703 | 14.6459 | 13.5991 | 11.4352 | 11.3529 |

| Ifih1 | 33.3646 | 13.4684 | 53.1812 | 47.2613 | 39.6817 | 49.6435 |

| Ifna2 | 46.9176 | 35.4407 | 48.8969 | 110.1361 | 46.3032 | 33.201 |

| Ifnb1 | 191.9296 | 77.4388 | 116.8007 | 204.3891 | 123.7216 | 176.2547 |

| I112a | 1.0569 | 0.7728 | 11.4167 | 5.5028 | 6.3545 | 4.2954 |

| I112b | 2.9905 | 1.5648 | 3.7868 | 4.3687 | 3.911 | 5.9576 |

| I115 | 3.8081 | 2.7899 | 11.8018 | 9.9397 | 8.4968 | 9.872 |

| I11b | 14.8197 | 9.2556 | 315.9389 | 139.252 | 212.1148 | 180.1732 |

| I16 | 42.1981 | 35.15 | 143.6836 | 38.8073 | 83.2055 | 93.4019 |

| Irf5 | 3.0067 | 1.8281 | 9.9257 | 7.9499 | 10.4111 | 7.4309 |

| Irf7 | 16.3868 | 9.8957 | 41.8474 | 36.1075 | 39.9145 | 32.6089 |

| Isg15 | 24.8175 | 19.0318 | 60.4863 | 53.5228 | 40.4988 | 47.3415 |

| Mefv | 18.4764 | 11.8051 | 479.3221 | 190.1918 | 375.9599 | 263.4663 |

| Mx1 | 100.8446 | 56.1156 | 90.4917 | 109.031 | 76.7076 | 108.7471 |

| Myd88 | 4.0087 | 2.4033 | 9.1601 | 6.4648 | 8.838 | 8.1037 |

| Nfkb1 | 2.5555 | 2.0008 | 4.2605 | 3.4649 | 3.5274 | 3.1886 |

| Nfkbia | 2.981 | 2.5919 | 15.5327 | 7.4212 | 12.8719 | 8.4526 |

| Nlrp3 | 8.3916 | 5.6752 | 257.972 | 92.9132 | 179.3776 | 88.0425 |

| Nod2 | 5.966 | 4.2489 | 43.4247 | 23.3113 | 25.7234 | 24.6172 |

| Oas2 | 21.786 | 14.3233 | 44.5996 | 26.7845 | 40.3557 | 35.8233 |

| Pstpip1 | 3.5375 | 3.2009 | 16.9808 | 6.9599 | 17.596 | 18.9852 |

| Spp1 | 0.9761 | 0.6561 | 2.497 | 1.3062 | 4.1477 | 2.0808 |

| Stat1 | 6.2749 | 3.231 | 8.178 | 7.6409 | 7.4526 | 8.8518 |

| Tlr3 | 8. 2113 | 4.5661 | 7.6397 | 10.5807 | 6.0433 | 8.0489 |

| Tlr7 | 0.7961 | 0.9648 | 5.2014 | 3.46 | 5.7532 | 8.2322 |

| Tlr8 | 2.8986 | 3.7394 | 23.0149 | 19.1729 | 34.9616 | 30.8464 |

| Tlr9 | 4.8543 | 3.2732 | 16.5676 | 14.3756 | 22.1639 | 28.8562 |

| Tnf | 9.7969 | 4.606 | 114.9693 | 68.2913 | 104.7328 | 51.8391 |

| Trim25 | 8.5892 | 2.9636 | 15.8971 | 5.7185 | 16.0737 | 9.8266 |

Data are representative of two independent experiments.

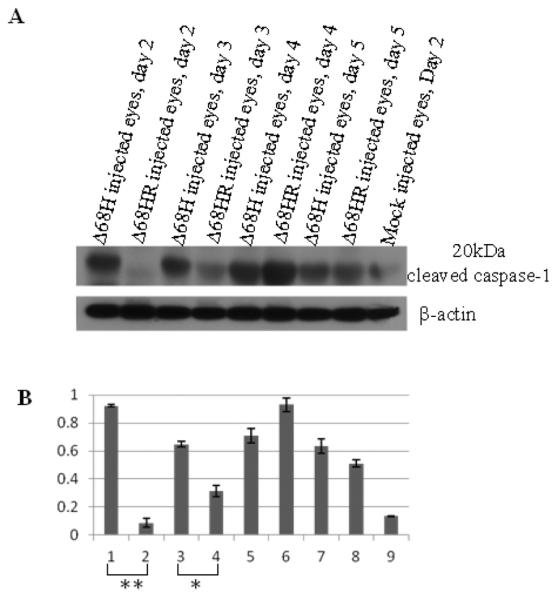

To confirm that the NLRP3 inflammasome was reduced in Δ68HR injected eyes compared to Δ68H injected eyes, levels of cleaved caspase 1 were measured by western blot. The results showed that levels of cleaved caspase 1 were significantly lower in Δ68HR injected eyes than in Δ68H injected eyes at day 2 and day 3 p.i. (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

(A) Western blot of cleaved caspase 1 in Δ68H and Δ68HR injected eyes 2, 3, 4, 5, days after inoculation of virus. Protein from medium injected eyes was used as the control. (B) Ratio of cleaved caspase 1 to β-actin. Significant more cleaved caspase 1 was detected in Δ68H injected eyes than in Δ68HR injected eyes at day 2 p.i. (**P < 0.01, Student's t test) and day 3 p.i. (*P < 0.05; Student's t test).

The same 84 early immune response genes were studied in the ipsilateral EW nucleus, the first target of HSV-1 spread from injected eye to brain. Interestingly, immune response gene regulation in the brain was slightly different from what we observed in the injected eyes. As shown in Table 2, among 84 genes detected in ipsilateral EW nucleus, 57 genes showed no significant difference (less than 3 fold difference) between virus injected groups and the medium injected group, and 27 genes were 3 or more fold upregulated after either Δ68HR or Δ68H infection at one or more time points. Unlike injected eyes, there was no difference in imflammasome gene NLRP3 between Δ68H and Δ68HR in the EW nucleus. In the brain, the levels of CCL3, CCL4, CCL5 were less than that in the injected eyes and essentially the same between Δ68HR and Δ68H infected brain. Similar to what was observed in injected eyes, chemokines CXCL9, CXCL10 were also upregulated in the brain during virus infection and these chemokines were more upregulated in Δ68H infected brain than in Δ68HR infected brains. At day 4 p.i, CXCL9 and CXCL10 were 17 and 5 fold respectively more upregulated in the ipsilateral EW nucleus of Δ68H infected mice than in the ipsilateral EW nucleus of Δ68HR infected mice. Similar to injected eyes, the levels of IL12 (IL12b) and CD40 in the ipsilateral EW nucleus of Δ68H infected mice were also higher than in the ipsilateral EW nucleus of Δ68HR infected mice.

Table 2.

27 upregulated immune response genes in the brains of Δ68H (h) infected mice and Δ68HR(hr) infected mice at day 2, day 3, day 4, day 5, day 6 p.i.

| Symbol | H-Day2 | HR-Day2 | H-Day3 | HR-Day3 | H-Day4 | HR-Day4 | H-Day5 | HR-Day5 | H-Day6 | HR-Day6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ccl3 | 0.4503 | 0.6275 | 0.113 | 5.5398 | 0.5636 | 0.8328 | 3.3842 | 3.1688 | 5.7636 | 9.3751 |

| Ccl4 | 0.4021 | 0.8664 | 0.5189 | 1.3356 | 1.3102 | 2.0621 | 16.0269 | 22.7699 | 29.1537 | 38.5506 |

| Ccl5 | 0.6799 | 0.9075 | 1.0549 | 0.832 | 1.1544 | 1.1498 | 31.9718 | 19.5599 | 48.6142 | 47.5839 |

| Cd40 | 1.1153 | 0.0298 | 0.7333 | 0.3484 | 1.5072 | 0.371 | 6.5026 | 2.8824 | 0.283 | 0.0567 |

| Cd86 | 1.49 | 1.7479 | 0.1471 | 0.7688 | 1.5529 | 1.4953 | 2.9308 | 1.7679 | 5.5552 | 5.5717 |

| Cxxll0 | 2.2076 | 2.363 | 4.941 | 0.7831 | 428.5652 | 24.5665 | 4688.538 | 3921.32 | 652.0239 | 1370.218 |

| Cxcll | 0.8203 | 0.5455 | 0.4303 | 0.7243 | 3.7589 | 2.4049 | 41.6323 | 28.8505 | 33.7472 | 34.2325 |

| Cxcl9 | 6.3795 | 2.8105 | 5.6651 | 4.1488 | 153.4289 | 30.8168 | 2004.459 | 1209.201 | 1512.927 | 1082.398 |

| Ddx58 | 0.5291 | 0.6133 | 0.5267 | 0.8383 | 1.2103 | 1.0356 | 9.2293 | 6.024 | 10.8762 | 8.6093 |

| Ifihl | 0.3497 | 0.4208 | 0.0551 | 20.2281 | 0.5675 | 0.6948 | 5.6281 | 4.7434 | 4.0842 | 5.095 |

| Ifna2 | 3.2931 | 0.484 | 10.0277 | 0.5581 | 0.6377 | 8.9779 | 1.8777 | 3.8632 | 5.0868 | 1.2267 |

| Ifnarl | 378.938 | 431.2332 | 359.6606 | 261.3389 | 343.0538 | 318.3124 | 367.972 | 254.0787 | 69.556 | 78.4675 |

| Ifnbl | 0.3362 | 0.7514 | 0.8937 | 1.0378 | 1.3238 | 7.1088 | 11.116 | 26.4879 | 20.9814 | 25.9211 |

| IIl2b | 0.336 | 1.0857 | 0.7261 | 0.7612 | 3.2716 | 0.9768 | 49.7242 | 15.8027 | 26.6653 | 13.9442 |

| IIlb | 0.8154 | 1.3562 | 0.6915 | 0.7762 | 1.5127 | 2.002 | 6.7291 | 5.9165 | 6.4415 | 2.0469 |

| II6 | 0.516 | 0.4147 | 0.1375 | 0.3689 | 0.5424 | 0.3914 | 3.7143 | 3.6118 | 3.7687 | 2.3302 |

| Irf7 | 0.8816 | 1.1597 | 2.0761 | 1.7684 | 5. 1425 | 4.9749 | 75.0808 | 37.282 | 108.104 | 71.7936 |

| Isgl5 | 0.7739 | 0.8588 | 0.0033 | 1.7685 | 3.662 | 3.4759 | 9.7681 | 32.4246 | 67.5174 | 70.7328 |

| Mavs | 1.0573 | 1.8008 | 1.0127 | 3.5116 | 0.9704 | 9.0234 | 0.651 | 1.4114 | 2.6069 | 5.1266 |

| Mefv | 0.2014 | 0.1056 | 0.7093 | 0.4318 | 0.1227 | 0.4566 | 22.226 | 19. 7787 | 9.012 | 9.5221 |

| Mxl | 0.5811 | 0.5959 | 0.551 | 0.7229 | 5.0761 | 1.7551 | 69.7877 | 69.9805 | 66.192 | 48.4146 |

| Myd88 | 1.063 | 0.9265 | 0.2296 | 0.5807 | 2.67 | O.6584 | 7.7775 | 3.186 | 1.2 | 1.3579 |

| Oas2 | 0.3579 | 2.8787 | 0.4008 | 1.9324 | 0.7982 | 1.0025 | 13.4081 | 12.3836 | 6.9448 | 7.9477 |

| Statl | 0.7964 | 0.8297 | 0.9962 | 0.9938 | 0.9569 | 1.4167 | 10.8049 | 6.3333 | 13.66 | 13.8859 |

| Tlr9 | 0.7685 | 0.7596 | 1.4513 | 0.7825 | 0.9386 | 1.0095 | 7.6707 | 5.0592 | 6.7271 | 6.2737 |

| Inf | 1.1595 | 2.1312 | 0.6655 | 4.4935 | 1.0628 | 1.4475 | 12.0033 | 5.7665 | 6.2199 | 5.3197 |

| Trim25 | 0.8195 | 1.377 | 1.2048 | 0.9098 | 1.3777 | 2.8178 | 4.5313 | 4.4403 | 5.2053 | 4.4561 |

Data are representative of two independent experiments.

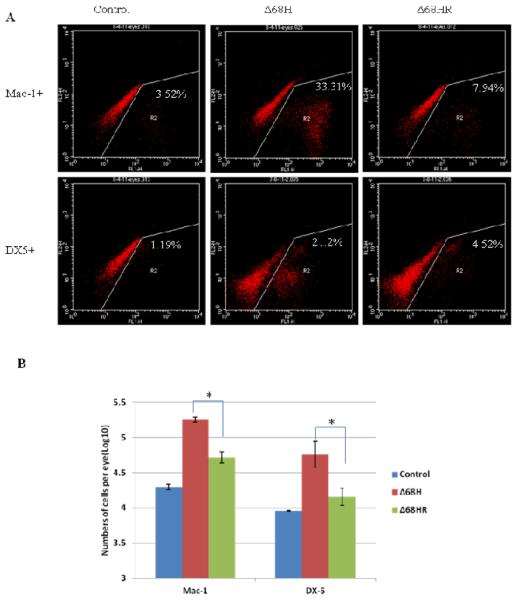

3.4. Immune cell responses in the injected eye and brain

Since message levels for chemokines CCL3, CCL4, CCL5, which are produced mainly by macrophages/microglia were more upregulated in Δ68H injected eyes than in Δ68HR injected eyes, we hypothesized that lack of the BBD would correlate with increased recruitment and activation of macrophages/microglia. To test our hypothesis, single ocular cell suspensions were made from Δ68H, Δ68HR or medium injected eyes at day 2, 3, 4, 5 p.i., and Mac-1+ cells as well as other kinds of immune cells including DX5+ NK cells, CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells were counted by flow cytometry. As shown in table 3, more Mac-1+ cells and DX5+ NK cells were observed in the injected eyes of Δ68H infected mice than in the injected eyes of Δ68HR infected mice from day 2 p.i. to day 4 p.i. Especially at day 3 p.i., significantly more Mac-1+ cells and DX-5+ cells were recovered from Δ68H injected eyes than from Δ68HR injected eyes (Figure 6). However, by day 5 p.i., more Mac-1+ cells were observed in Δ68HR injected eyes than in Δ68H injected eyes. The number of CD4+ or CD8+ cells was not significantly different between Δ68HR injected eyes and Δ68H injected eyes.

Table 3.

The number of immune cells detected in the injected eyes of medium injected control mice(ctr), Δ68H infected mice (68H) and Δ68HR infected mice (68HR) at day 2, day3, day 4 and day 5 p.i.

| Mac-1+ | DX5+ | CD4+ | CD8+ | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ctr | 68H | 68HR | ctr | 68H | 68HR | ctr | 68H | 68HR | ctr | 68H | 68HR | |

| Day 2 | 6.0×103 | 4.4×104 | 4.0×104 | 5.6×103 | 2.7×104 | 2.5×104 | 1.4×103 | 7.1×103 | 9.0×103 | 1.4×103 | 7.1×103 | 9.0×103 |

| Day 3 | 2.1×104 | 1.7×105 | 4.6×104 | 9.1×103 | 9.2×104 | 1.9×104 | 1.0×104 | 1.6×104 | 2.5×104 | 3.4×103 | 2.5×103 | 1.1×104 |

| Day 4 | 1.2×104 | 7.2×105 | 5.0×105 | 8.9×103 | 5.1×104 | 3.2×104 | 1.1×104 | 4.1×104 | 7.7×104 | 3.0×103 | 1.7×104 | 1.9×104 |

| Day 5 | 2.2×104 | 3.1×105 | 6.7×105 | 7.6×103 | 4.1×104 | 4.3×104 | 1.3×104 | 1.9×104 | 1.7×104 | 4.4×104 | 9.6×103 | 5.3×103 |

Data are representative of two or more independent experiments.

Figure 6.

Mac-1+ and DX5+ cells in Δ68H and Δ68HR injected eyes at day3 p.i. (A) Flow cytometry histograms of cells from medium injected control eyes, Δ68H injected eyes and Δ68HR injected eyes at day 3 p.i. Cells were stained with DX-5-FITC or Mac-1-FITC. (B) The number of Mac-1+ and DX5+ cells per medium injected control eye, Δ68H injected eye and Δ68HR injected eye at day 3 p.i. (Mean ± SD). Significant more Mac-1+ and DX5+ cells were detected in Δ68H injected eyes than in Δ68HR injected eyes (*P < 0.05, Student's t test).

To determine if lack of BBD affected immune cell response in the brain, mononuclear cells were isolated from ipsilateral EW nucleus. Mac-1+ cells as well as DX5+ NK cells, CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells were determined by flow cytometry. Not surprisely, the majority of isolated mononuclear cells from uninfected brains and virus infected brains were Mac-1 positive macrophages/microglia (more than 78% in all the samples at all times). Compared to non-virus infected control mice, the number of DX5+ NK cells in the ipsilateral EW nucleus was increased in both Δ68HR and Δ68H infected mice beginning at day 4 p.i. However, there was no difference in DX5+ NK cells in the ipsilateral EW nucleus between Δ68HR and Δ68H infected mice. Only a few CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (less than 1%) were detected in the brain tissue of virus infected mice at day 3 and 4 p.i. as well as control mice. However, the number of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in virus infected brain tissue was increased beginning at day 5 p.i. and at day 6 p.i. respectively. At day 6 p.i., the number of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was higher in Δ68H infected brains than in Δ68HR infected brains (CD4+: 7.06% vs 4.27%; CD8+: 3.02% vs 1.87%).

4. Discussion

In these studies, spread of marker rescued virus Δ68HR was similar to HSV-1 H129, a highly neuroinvasive strains of HSV-1. Virus was detected in the ipsilateral EW nucleus as early as day 3 p.i., and then spread to both SCN by day 4 p.i. and retinitis was observed in both contralateral eye and ipsilaterial eye. Although Δ68HR most likely spread to ipsilateral retina via retino-recipient nuclei of the contralateral SCN, direct spread of viruses from anterior segment to posterior segment might also contribute to ipsilateral retinal infection since a few HSV-1 positive cells were observed in ganglion cell layer of retina of injected eyes at day 3 p.i. before virus had spread to the contralateral SCN.

Although Δ68H replicated equivalently to Δ68HR in the injected eyes at day 1 or 2 p.i, significantly less replicating HSV-1 as well as less severe ipsilateral retinal infection was observed in Δ68H infected mice by day 3 p.i. and an earlier Mac-1 positive cells and NK cells response was detected in the eyes injected with Δ68H than in the eyes injected with Δ68HR. Mac-1 is highly expressed in macrophage/microglia and widely used as markers of macrophage/microglia. Other types of immune cells, such as subsets of neutrophils and B cells, also express Mac-1 (Kantor et al., 1992; Lagasse et al., 1996; Zheng et al., 2008) and these cell types may be present in the eye. These results suggest that during HSV-1 infection of the eye, BBD inhibits autophagy and the early innate immune response mediated by NK cells, macrophage/microglia and neutrophils in the injected eye which, in turn, allows increased virus replication and retinal damage.

The mechanism by which the autophagy response activates the innate immune response during viral infection remains poorly understood. The innate immune system relies on a limited set of germline-encoded pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) which are specific for conserved moieties associated with cellular damage (DAMPs; danger associated molecular patterns) or invading organisms (PAMPs; pathogen associated molecular patterns) (Kumar et al., 2009). PRRs are expressed on a variety of host cells, among them epithelial cells in tissues with mucosal surfaces and immune cells of the myeloid lineage. PRRs comprise, but are not limited to, members of the trans-membrane Toll-like receptors (TLRs), C-type lectin receptors (CLRs), the nucleotide binding domain leucine-rich repeat containing receptor (NLR), retinoic acid inducible gene-I (RIG-I)-like helicases and HIN200 proteins (Kawai, et al., 2006; Takeuchi et al., 2010; Kanneganti et al., 2007). Results of a study by Lee et al, suggest that PAMP of single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) virus is recognized by TLR7 following transport into lysosome by the process of autophagy (Lee et al., 2007). In our studies, a much stronger NLRP3 inflammasome response was noted in the eyes injected with BBD deficient HSV-1 than in the eyes injected with the rescued strain, which suggests that increased autophagy activates the innate immune response in the eye through the activation of NLRP3.

NLRP3 is one of the best-studied members of the NLR family. Activation of NLR leads to formation of inflammasomes, which are multiprotein complexes that can activate caspase-1 and ultimately lead to the processing and secretion of IL-1β, IL-18 and IL-33, and drive the innate immune response such as activation and recruitment of macrophage/microglia (Kanneganti et al., 2010; Broz et al., 2011; Skeldon et al., 2011). NLR Inflammasome is emerging as a key regulator of the host response against microbial pathogens (Kanneganti et al., 2010; Broz et al., 2011; Skeldon et al., 2011). NLRP3 is activated by a number of divergent activators and plays an important part in antiviral host defense (Kanneganti et al., 2010; Broz et al., 2011; Skeldon et al., 2011). Although a role for NLRP3 in sensing viruses has been proposed, the precise mechanism remains poorly understood. Several lines of evidence indicate that the NLRP3 inflammasome might detect the presence of viral RNA and DNA in intracellular compartments. For example, transfection of human and mouse cell lines with ssRNA or dsRNA analogues, such as polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid [poly(I:C)], is sufficient to activate NLRP3 (Allen et al., 2009). Similarly, purified dsRNA from rotavirus or brome mosaic virus and ssRNA of influenza A virus also activate NLRP3 (Allen et al., 2009; Ichinohe et al., 2009; Kanneganti et al., 2006). NLRP3 has also been implicated in the detection of adenoviral DNA in cell culture (Muruve et al., 2008). A pathway involving lysosomal destabilization has been proposed for crystal induced activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome (Hornung et al., 2008), and it has been reported that that adenovirus, a DNA virus, activates the NLRP3 inflammasome via lysosomal destabilization (Barlan et al., 2011). Disruption of lysosomal membranes and the release of chemicals such as cathepsin B or uric acid into the cytoplasm were shown to be required for adenovirus -induced NLRP3 activation. In our studies, there are several reasons why increased autophagy activation in BBD deficient HSV-1 enhanced activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. There are several possibilities. Viral PAMPs (which are composed mainly of unique nucleic acids, such as dsRNA, ssRNA and cytosolic DNA, but also include several viral fusion glycoproteins) are produced in the autophagosome by degradation of HSV-1. HSV-1 PAMPs might be released to cytoplasm to activate NLRP3 inflammasome or alternatively, the autolysosome might deliver HSV-1 PAMPs to intracellular NLRP3 inflammasome compartment. It is also possible that activated autolysosomes might release non-viral activators of the NLRP3 inflammasome such as DAMPs, cathepsin B or uric acid.

Similar to previous resports (Leib et al., 2009), less severe CNS infection and encephalitis were noted in BBD deficient Δ68H infected mice. Innate and adaptive immune response against HSV-1 in the brain was slightly different from the injected eyes. For example, stronger microglia and NK cell response or NLRP3 inflammasome were not observed in Δ68H infected brains than in Δ68HR infected brains. Chemokines CXCL9, CXCL10 were significantly upregulated in the brain tissue after virus infection beginning at day 4 p.i. and their mRNA level was much higher in Δ68H infected brains than in Δ68HR infected. Chemokines CXCL9 and CXCL10, which are produced predominantly by activated astrocytes and microglia in the central nervous system, are potent chemoattractants for activated T-cells, NK cells, and monocytes (Glass et al., 2003; Becher et al., 2000). Since CCL3, CCL4, CCL5, which are produced predominantly by microglia/macrophages (Glass et al., 2003; Carter et al., 2007), were only slightly upregulated in the brain tissue after either Δ68H or Δ68HR infection, the higher level of chemokines CXCL9, CXCL10 observed in Δ68H infected brain suggests that lack of BBD enhances activation of astrocytes in the brain. Stronger adaptive immune response was also noted in Δ68H infected brain than in Δ68HR infected since day 5 p.i. However, CD4+ or CD8+ T cells were not significantly different between Δ68HR injected eyes and Δ68H injected eyes. The result is not surprising since virus infection in Δ68H injected eyes was more effectively controlled by innate immunity than in Δ68HR injected eyes, the adaptive response in Δ68H mice did not need to be as robust in Δ68HR infected eyes. The results of these studies support the idea that a critical component of the pathogenesis of HSV-1 infection of the eye is the ability of wild type virus (with an intact BBD) to prevent early activation of the innate immune response. Studies are in progress to better define the role of autophagy in the pathogenesis of HSV-1.

Highlights

HSV-1 infection is antagonized by the Beclin-binding domain (BBD).

Lack of the BBD limits virus replication and retinal damage.

Lack of the BBD increases autophagy response and activation of NLRP3 imflammasome.

Increasing autophagy response induces a more rapid innate immune response.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant EY006012.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Adler MW, Rogers TJ. Are chemokines the third major system in the brain? J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:1204–9. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0405222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen IC, Scull MA, Moore CB, et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome mediates in vivo innate immunity to influenza A virus through recognition of viral RNA. Immunity. 2009;30:556–565. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archin NM, Atherton SS. Rapid spread of a neurovirulent strain of HSV-1 through the CNS of BALB/c mice following anterior chamber inoculation. J. Neurovirol. 2002a;8:122–135. doi: 10.1080/13550280290049570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archin NM, Atherton SS. Infiltration of T-lymphocytes in the brain after anterior chamber inoculation of a neurovirulent and neuroinvasive strain of HSV-1. J Neuroimmunol. 2002b;130:117–27. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00213-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atherton S. Acute retinal necrosis: Insights into pathogenesis from the mouse model. Herpes. 2001;8:69–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlan AU, Griffin TM, McGuire KA, Wiethoff CM. Adenovirus membrane penetration activates the NLRP3 inflammasome. J. Virol. 2011;85:146–155. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01265-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becher B, Prat A, Antel JP. Brain-immune connection: immuno-regulatory properties of CNS-resident cells. Glia. 2000;29:293–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosem ME, Harris R, Atherton SS. Optic nerve involvement in viral spread in herpes simplex virus type 1 retinitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990;31:1683–1689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broz P, Monack DM. Molecular mechanisms of inflammasome activation during microbial infections. Immunol Rev. 2011;243(1):174–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01041.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulloch K, Miller MM, Gal-Toth J, et al. CD11c/EYFP transgene illuminates a discrete network of dendritic cells within the embryonic, neonatal, adult, and injured mouse brain. J Comp Neurol. 2008;508:687–710. doi: 10.1002/cne.21668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter SL, Müller M, Manders PM, Campbell IL. Induction of the genes for Cxcl9 and Cxcl10 is dependent on IFN-gamma but shows differential cellular expression in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and by astrocytes and microglia in vitro. Glia. 2007;55:1728–39. doi: 10.1002/glia.20587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duker JS, Blumenkranz MS. Diagnosis and management of the acute retinal necrosis (ARN) syndrome. Surv Ophthalmol. 1991;35:327–343. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(91)90183-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English L, Chemali M, Duron J, Rondeau C, Laplante A, et al. Autophagy enhances the presentation of endogenous viral antigens on MHC class I molecules during HSV-1 infection. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(5):480–487. doi: 10.1038/ni.1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezra E, Pearson RV, Etchells DE, Gregor ZJ. Delayed fellow eye involvement in acute retinal necrosis syndrome. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1995;120:115–116. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)73770-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcone PM, Brockhurst RJ. Delayed onset of bilateral acute retinal necrosis syndrome; a 34-year interval. Ann. Ophthalmol. 1993;25:373–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin KBJ, Paxinos G. The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gack MU. TRIMming Flavivirus infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10:175–7. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass WG, Rosenberg HF, Murphy PM. Chemokine regulation of inflammation during acute viral infection. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;3:467–73. doi: 10.1097/00130832-200312000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez MG, Master SS, Singh SB, et al. Autophagy is a defense mechanism inhibiting BCG and Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival in infected macrophages. Cell. 2004;119:753–766. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornung V, Bauernfeind F, Halle A, et al. Silica crystals and aluminum salts activate the NALP3 inflammasome through phagosomal destabilization. Nat. Immunol. 2008;9:847–856. doi: 10.1038/ni.1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichinohe T, Lee HK, Ogura Y, Flavell R, Iwasaki A. Inflammasome recognition of influenza virus is essential for adaptive immune responses. J. Exp. Med. 2009;206:79–87. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanneganti TD, Body-Malapel M, Amer A, et al. Critical role for cryopyrin/ Nalp3 in activation of caspase-1 in response to viral infection and double-stranded RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:36560–36568. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607594200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanneganti TD, Lamkanfi M, Núñez G. Intracellular NOD-like receptors in host defense and disease. Immunity. 2007;27:549–559. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanneganti TD. Central roles of NLRs and inflammasomes in viral infection. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:688–98. doi: 10.1038/nri2851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantor AB, Stall AM, Adams S, Herzenberg LA, Herzenberg LA. Differential development of progenitor activity for three B-cell lineages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:3320–3324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T, Akira S. TLR signaling. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:816–825. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyei GB, Dinkins C, Davis AS, et al. Autophagy pathway intersects with HIV-1 biosynthesis and regulates viral yields in macrophages. J. Cell Biol. 2009;186:255–268. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200903070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kihara A, Kabeya Y, Ohsumi Y, Yoshimori T. Beclin-phophatidylinositol 3-kinase complex functions at the trans-Golgi network. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:330–335. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar H, Kawai T, Akira S. Pathogen recognition in the innate immune response. Biochem. J. 2009;420:1–16. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagasse E, Weissman IL. Flow cytometric identification of murine neutrophils and monocytes. J Immunol Methods. 1996;197:139–150. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(96)00138-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HK, Lund JM, Ramanathan B, Mizushima N, Iwasaki A. Autophagy-dependent viral recognition by plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Science. 2007;315:1398–1401. doi: 10.1126/science.1136880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leib DA, Alexander DE, Cox D, Yin J, Ferguson TA. Interaction of ICP34.5 with Beclin 1 modulates herpes simplex virus type 1 pathogenesis through control of CD4+ T-cell responses. J Virol. 2009;83(23):12164–71. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01676-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine B, Deretic V. Unveiling the roles of autophagy in innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:767–777. doi: 10.1038/nri2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang XH, Jackson S, Seaman M, et al. Induction of autophagy and inhibition of tumorigenesis by beclin 1. Nature. 1999;402:672–676. doi: 10.1038/45257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodoen MB, Lanier LL. Natural killer cells as an initial defense against pathogens. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:391–8. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muruve DA, Pétrilli V, Zaiss AK, et al. The inflammasome recognizes cytosolic microbial and host DNA and triggers an innate immune response. Nature. 2008;452:103–107. doi: 10.1038/nature06664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan B, Thomas R. CD40 and dendritic cell function. Crit Rev Immunol. 2003;23:83–107. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v23.i12.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orvedahl A, Alexander D, Talloczy Z, et al. HSV-1 ICP34.5 confers neurovirulence by targeting the Beclin 1 autophagy protein. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;1:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paludan C, Schmid D, Landthaler M, et al. Endogenous MHC class II processing of a viral nuclear antigen after autophagy. Science. 2005;307:593–596. doi: 10.1126/science.1104904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheller J, Chalaris A, Schmidt-Arras D, Rose-John S. The pro- and anti-inflammatory properties of the cytokine interleukin-6. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:878–88. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlingemann RO, Bruinenberg M, Wertheim-van Dillen P, Feron E. Twenty years' delay of fellow eye involvement in herpes simplex virus type 2-associated bilateral acute retinal necrosis syndrome. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1996;122:891–892. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70390-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid D, Münz C. Innate and adaptive immunity through autophagy. Immunity. 2007;27:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SB, Davis AS, Taylor GA, Deretic V. Human IRGM induces autophagy to eliminate intracellular mycobacteria. Science. 2006;313:1438–1441. doi: 10.1126/science.1129577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skeldon A, Saleh M. The inflammasomes: molecular effectors of host resistance against bacterial, viral, parasitic, and fungal infections. Front Microbiol. 2011;2:15. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talloczy Z, Virgin HWT, Levine B. PKR dependent autophagic degradation of herpes simplex virus type 1. Autophagy. 2006;2:24–29. doi: 10.4161/auto.2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi O, Akira S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell. 2010;140:805–820. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasdemir E, Galluzzi L, Maiuri MC, et al. Methods for assessing autophagy and autophagic cell death. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;445:29–76. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-157-4_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urayama A, Yamada N, Sasaki T, Mishiyama Y, Watanabe H, Wakusawa S. Unilateral. Acute Uveitis with Retinal Periarteritis and Detachment. Jpn J Clin Ophthalmol. 1971;25:607–619. [Google Scholar]

- Vann VR, Atherton SS. Neural spread of herpes simplex virus after anterior chamber inoculation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991;32:2462–2472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittum J, McCulley J, Niederkorn JY, Streilein J. Ocular disease induced in mice by anterior chamber inoculation of herpes simplex virus. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1984;25:1065–1073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z, Klionsky DJ. Autophagosome formation: core machinery and adaptations. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1102–1109. doi: 10.1038/ncb1007-1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yorimitsu T, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy: molecular machinery for self-eating. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12(Suppl. 2):1542–1552. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Marshall B, Atherton SS. Murine cytomegalovirus infection and apoptosis in organotypic retinal cultures. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:295–303. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng M, Fields MA, Liu Y, Cathcart H, Richter E, Atherton SS. Neutrophils protect the retina from infection after anterior chamber inoculation of HSV-1 in BALB/c mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;9:4018–4025. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]