Abstract

Patients with limited cardiac reserve are less likely to survive and develop more complications following major surgery. By augmenting oxygen delivery index (DO2I) with a combination of intravenous fluids and inotropes (goal directed therapy (GDT)), postoperative mortality and morbidity of high-risk patients may be reduced. However, although most studies suggest that GDT may improve outcome in high-risk surgical patients, it is still not widely practiced. We set out to test the hypothesis that GDT results in greatest benefit in terms of mortality and morbidity in patients with the highest risk of mortality and have undertaken a systematic review of the current literature to see if this is correct. We performed a systematic search of Medline, Embase and CENTRAL databases for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and reviews of GDT in surgical patients. To minimize heterogeneity we excluded studies involving cardiac, trauma, and paediatric surgery. Extremely high risk, high risk and intermediate risks of mortality were defined as >20%, 5 to 20% and <5% mortality rates in the control arms of the trials, respectively. Meta analyses were performed and Forest plots drawn using RevMan software. Data are presented as odd ratios (OR; 95% confidence intervals (CI), and P-values). A total of 32 RCTs including 2,808 patients were reviewed. All studies reported mortality. Five studies (including 300 patients) were excluded from assessment of complication rates as the number of patients with complications was not reported. The mortality benefit of GDT was confined to the extremely high-risk group (OR = 0.20, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.41; P < 0.0001). Complication rates were reduced in all subgroups (OR = 0.45, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.60; P < 0.00001). The morbidity benefit was greatest amongst patients in the extremely high-risk subgroup (OR = 0.27, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.51; P < 0.0001), followed by the intermediate risk subgroup (OR = 0.43, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.67; P = 0.0002), and the high-risk subgroup (OR 0.56, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.89; P = 0.01). Despite heterogeneity in trial quality and design, we found GDT to be beneficial in all high-risk patients undergoing major surgery. The mortality benefit of GDT was confined to the subgroup of patients at extremely high risk of death. The reduction of complication rates was seen across all subgroups of GDT patients.

Introduction

A significant number of patients who undergo major surgery suffer postoperative complications, many of which may be avoidable [1,2]. The associated health and financial loss is significant, especially considering patients who suffer from postoperative complications suffer long-term morbidity [3]. A significant proportion of patients undergoing surgery suffer from postoperative complications, and identification of this cohort of patients may enable appropriate preventative measures to be taken [4]. Perioperative goal-directed therapy (GDT) aims to match the increased oxygen demand incurred during major surgery, by flow-based haemodynamic monitoring and therapeutic interventions to achieve a predetermined haemodynamic endpoint. When carried out early, in the right patient cohort, and with a clearly defined protocol, GDT has been shown to reduce postoperative mortality and morbidity [5].

Despite this, postoperative GDT is not carried out widely, perhaps due to the lack of evidence for its benefit from large multicenter randomized clinical trials. Scepticism about GDT may exist for a number of reasons: many of the studies performed may be considered outdated; the high mortality rates in some of the studies performed are not representative of current clinical practice; and pulmonary artery catheters (PACs) are used in many of the clinical trials but have been largely superseded by less invasive haemodynamic monitors. A recent meta-analysis has demonstrated that although studies prior to 2000 demonstrate a benefit in mortality, studies con ducted after 2000 demonstrate a significant reduction in complication rates [5]. Furthermore, the reduction in complication rates is significant regardless of the type of haemodynamic monitor used.

We hypothesized that the benefits of GDT are greater in patients who are at higher risk of mortality. We defined risk by the mortality rate of the study population undergoing major surgery. We conducted this meta-analysis to determine if GDT in high-risk surgical patients undergoing major non-cardiac surgery improves postoperative mortality and morbidity, and if this was affected by the mortality risk among the population studied.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

We reported only randomized controlled trials, that reported morbidity (complications) and mortality as primary or secondary outcomes. GDT was defined as the term encompassing the use of haemodynamic monitoring and therapies aimed at manipulating haemodynamics during the perioperative period to achieve a predetermined haemodynamic endpoint(s). Studies with GDT started pre-emptively in the perioperative period (24 hours before, intraoperative or immediately after surgery) were included. The GDT must have an explicit protocol, defined as detailed step-by-step instructions for the clinician based on patient-specific haemodynamic data obtained from a haemodynamic monitor or surrogates (for example, lactate, oxygen extraction ratio), and predefined interventions carried out by the clinician in an attempt to achieve the goal(s). Interventions included fluid administration alone or fluids and inotropes together. As the use of inotropic agents was aimed at a specific haemodynamic goal(s) and titrated accordingly, fixed dose studies of inotropes were excluded. Only studies involving adult general surgical populations were included, and studies involving cardiac, trauma and paediatric surgery were excluded.

Information sources

A systematic literature search of MEDLINE (via Ovid), EMBASE (via Ovid) and the Cochrane Controlled Clinical trials register (CENTRAL, issue 4 of 2012) was conducted to identify suitable studies. Only articles written in English were considered. Date restrictions were not applied to the CENTRAL and MEDLINE searches. EMBASE was restricted to the years 2009 to2012 [6]. The last search update was in April 2012.

Search strategy

We included the following search terms: goal-directed therapy, optimization, haemodynamic, goal oriented, goal targeted, cardiac output, cardiac index, oxygen delivery, oxygen consumption, cardiac volume, stroke volume, fluid therapy, fluid loading, fluid administration, optimization, supranormal, lactate and extraction ratio. Search terms were entered into the electronic databases using search strategy methods validated by the Cochrane collaboration (see Box 1 for search strategies used) [7]. In addition to searching electronic databases, previous review articles on the subject were hand-searched for further references.

Methodological quality of included studies

Methodological quality of included studies was assessed using criteria described by Jadad and colleagues [8]. The Jadad scale analyzes methods used for random assignment, blinding and flow of patients in clinical trials. The range of possible scores is 0 (lowest quality) to 5 (highest quality).Studies were not excluded based on Jadad scores.

Analysis of outcomes

Three investigators independently screened both the titles and abstracts to exclude non-pertinent studies. Relevant full text articles were then retrieved and analysed for eligibility against the pre-defined inclusion criteria. Information from selected studies was extracted using a standardized data collection form. Data were collected independently by three different investigators (GA, NA and CC) and discrepancies resolved by a fourth author (MC).

Hospital mortality was reported in all the included articles and was the primary outcome of our study. Morbidity, expressed as number of patients with complications, was the secondary outcome. Mortality risk groups were based on the definition of the high-risk surgical patient by Boyd and Jackson, such that patients whose risk of mortality was 5 to 19% and ≥20% were classified as high-risk and extremely high-risk, respectively [9]. We therefore performed subgroup analyses based on the control group mortality in each study. We created three subgroups based on the mortality rate of the control group. Mortality rates of 0 to 4.9%, 5 to 19.9%, and ≥20% were considered intermediate, high risk, and extremely high risk, respectively. Mortality and complications were analyzed according to the above subgroups. Studies were also analyzed according to the type of monitor used, type of interventions, the therapeutic goals, and the use of 'supranormal' physiological goals.

Statistical analysis

Dichotomous data outcomes were analysed using the Mantel-Haenszel random effects model and results presented as an odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The meta-analysis was carried out using review manager ('Revman') for MAC (version 5.1, Cochrane collaboration, Oxford, UK). Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 methodology. When an I2 value of >50% was present heterogeneity and inconsistency were considered significant, and when it was >75% these were considered highly significant [10]. All P-values were two-tailed and considered statistically significant if <0.05.

Results

Included trials

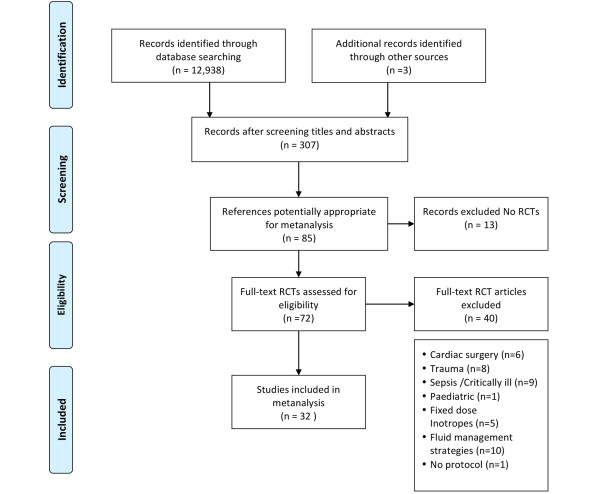

The search strategy used in this study produced 12,938 potential titles (Figure 1). After screening of titles and abstracts, 307 references were identified as relevant to perioperative GDT. After further screening of titles and abstracts against our inclusion criteria, 85 references were retrieved for full text analysis. Detailed full text evaluation excluded 13 studies, as they were not randomized controlled trials [11-23]. Analysis of the remaining 72 randomized controlled trials produced the following exclusions: studies focusing on fluid management strategies (that is, liberal versus restrictive) [24-33], use of 'fixed dose' inotropic agents not titrated to a predetermined goal [34-38], cardiac surgery [39-44], trauma [45-52], paediatric surgery [53] and critically ill medical populations [54-62]. A study not using protocols to direct application of GDT was also excluded [63]. The quality of the trials was analysed using the Jadad score. The median Jadad score was 3.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram illustrating search strategy. RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Description of studies

A total of 32 studies were included in the meta-analysis (Table 1) [64-95]. These 32 studies included a total of 2,808 patients, 1,438 in the GDT arm and 1,370 in the control treatment arm. Five studies included patients who were considered extremely high risk, 12 included patients who were high risk, and 15 included patients who were intermediate risk. The intermediate-risk, high-risk, and extremely high-risk mortality subgroups included 1,569, 924, and 315 patients, respectively. There were similar numbers of patients in the GDT and control arms. Twenty studies initiated GDT at start of surgery, whilst the other studies initiated GDT before or immediately after surgery.

Table 1.

Summary of included studies

| Study | Year | Jadad score | Type of surgery | Number of patients GDT group | Number of patients control group | Type of monitor in GDT group | Intervention type | Goals in GDT group | Goals in control group | Mortality GDT (%) | Mortality control (%) | Complications GDT (%) | Complications control (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bender et al. [64] | 1997 | 1 | Elective vascular/aortic | 51 | 53 | PAC | Fluid and inotropes | CI ≥ 2.8 PAWP 8-14 SVR <1100 |

Standard care | 1.96 | 1.9 | 13.73 | 13.21 |

| Benes et al. [65] | 2010 | 3 | Elective abdominal | 60 | 60 | Flotrac | Fluid and inotropes | SVV <10% CI ≥2.5 |

MAP > 65 HR < 100 CVP 8-12 |

1.67 | 3.3 | 30 | 58.33 |

| Berlauk et al. [66] | 1991 | 2 | Peripheral vascular surgery | 68 | 21 | PAC | Fluid and inotropes | CI ≥2.8 PAWP 8-14 SVR <1100 |

Standard care | 1.47 | 9.5 | 16.7 | 42.8 |

| Bonazzi et al. [67] |

2002 | 2 | Elective vascular | 50 | 50 | PAC | Fluid and inotropes | CI >3.0 PAWP 10-18 SVR <1,450 DO2I >600 |

Standard care | 0 | 0 | 4 | 8 |

| Boyd et al. [68] | 1993 | 1 | Abdominal/vascular | 53 | 54 | PAC | Fluid and notropes | MAP 80-110 PAWP 12-14 SpO2 >94% Hb >12 DO2I >600 |

MAP 80-110 PAWP 12-14 SpO2 >94% Hb >12 UO >0.5 ml/ kg/h |

5.66 | 22.2 | NS | NS |

| Buettner et al. [69] | 2008 | 2 | Major abdominal or gynaecological | 40 | 40 | PiCCO | Fluids | SPV <10% HCt >23% Normal clotting |

Standard care | 0 | 2.5 | NS | NS |

| Cecconi et al. [70] | 2011 | 4 | Total hip replacement | 20 | 20 | Flotrac | Fluid and inotropes | SV change DO2I >600 |

Standard care | 0 | 0 | 80 | 100 |

| Challand et al. [71] | 2012 | 5 | Major open/laparoscopic colorectal | 89 | 90 | OD | Fluids | SV change | Standard care | 5.62 | 4.4 | 33.71 | 28.89 |

| Conway et al. [72] | 2002 | 2 | Major bowel resection | 29 | 28 | OD | Fluids | FTc >0.35 SV change |

Standard care | 0 | 3.6 | 17.24 | 32.14 |

| Donati et al. [73] | 2007 | 3 | Elective major abdominal/aortic | 68 | 67 | CVC | Fluids | O2ER <27% MAP >80 UO >0.5 CVP 8-12 Hb >10 |

MAP >80 UO >0.5 CVP 8-12 Hb >10 |

2.94 | 3 | 13.24 | 40.3 |

| Forget et al. [74] | 2010 | 2 | Major intrabdominal | 41 | 41 | Masimo pulsoximeter | Fluids | PVI <13% | Standard care | 4.88 | 0 | 78.05 | 100 |

| Gan et al. [75] | 2002 | 5 | Elective general, urological, gynaecologic | 50 | 50 | OD | Fluids | FTc >0.35 SV change |

Increase HR >20% baseline sBP <90 or CVP <20% baseline |

0 | 0 | 42 | 76 |

| Harten et al. [76] | 2008 | 3 | Emergency abdominal | 14 | 15 | Lidco | Fluids | PPV | Standard care | 7.14 | 13.3 | 50 | 26.67 |

| Jhanji et al. [77] | 2010 | 3 | Major surgery | 45 | 45 | LiDCO | Fluids | SV | CVP standard care |

11.11 | 13.3 | 57.58 | 66.67 |

| Lobo et al. [78] | 2000 | 3 | Major surgery | 19 | 18 | PAC | Fluid and inotropes | DO2I >600 | Standard care | 15.79 | 50 | 31.58 | 66.67 |

| Lobo et al. [79] | 2006 | 3 | Major surgery | 25 | 25 | PAC | Fluid and inotropes | PWP 12-16 MAP 70-110 HCt >30%, SAO2 >94% UO >0.5 DO2I >600 |

PAWP 12-16 MAP 70-110 HCt >30% SaO2 >94% UO >0.5 |

8 | 28 | 16 | 52 |

| Lopes et al. [80] | 2007 | 2 | Major surgery | 17 | 16 | IBPplus; Dixtal | Fluids | ΔPP <10% | Standard care | 11.76 | 31.3 | 41.18 | 75 |

| Mayer et al. [81] | 2010 | 2 | Major gastrointestinal surgery | 30 | 30 | Flotrac | Fluid and inotropes | CI >2.5 SVV <12% |

CVP 8-12 MAP >65 UO >0.5 |

6.67 | 6.7 | 20 | 50 |

| Noblett et al. [82] | 2006 | 5 | Colorectal | 51 | 52 | OD | Fluids | FTc >0.35 SV change |

Standard care | 0 | 1.9 | 1.96 | 15.38 |

| Pearse et al. [83] | 2005 | 3 | Major surgery | 62 | 60 | LiDCO | Fluid and inotropes | DO2I >600 | SaO2 ≥94% Hb >8 Temp >37°C HR <100 or <20 above baseline MAP 60-100 CI ≥2.5 |

11.29 | 15 | 43.35 | 68.33 |

| Senagore et al. [84] | 2009 | 3 | Elective lap colorectal | 42 | 22 | OD | Fluids | SV response | Standard care | 2.38 | 4.7 | NS | NS |

| Shoemaker et al. [85] | 1988 | 2 | Major surgery | 28 | 60 | PAC | Fluid and inotropes | CI >4.5 VO2 >170 DO2I >600 |

Standard care | 3.57 | 30 | 28.5 | 50 |

| Sinclair et al. [86] | 1997 | 2 | Neck of femur repair | 20 | 20 | OD | Fluids | FTc >0.35 SV change |

Standard care | 5 | 10 | NS | NS |

| Szakmany et al. [87] | 2005 | 3 | Major abdominal | 20 | 20 | PiCCO | Fluids | ITBV 850-950 ml/m2 | CVP Standard care |

9.09 | 5 | NS | NS |

| Ueno et al. [88] | 1998 | 2 | Hepatic resection | 16 | 18 | PAC | Fluid and inotropes | CI >4.5 VO2 >170 DO2I >600 |

SpO2 >95% Mean PAOP 11-15 mmHg Hb >10 |

0 | 11.1 | 0 | 27.78 |

| Valentine et al. [89] | 1998 | 3 | Aortic | 60 | 60 | PAC | Fluid and inotropes | CI >2.8 PAWP 8-15 SVR <1100 |

Standard care | 5 | 1.7 | 25 | 16.67 |

| Van Der linden et al. [90] | 2010 | 4 | Vascular | 40 | 17 | LiDCO + CVC | Fluid and inotropes | CI >2.5 | Standard care | 7.5 | 0 | 10 | 0 |

| Venn et al. [91] | 2002 | 3 | Neck of femur repair | 30 | 60 | OD | Fluids | FTc >0.35 SV change |

Standard care | 10 | 6.9 | 34.4 | 72.4 |

| Wakeling et al. [92] | 2005 | 3 | Colorectal | 67 | 67 | OD | Fluids | SV change | Standard care | 0 | 1.5 | 35.82 | 56.72 |

| Wenkui et al. [93] | 2010 | 3 | Elective GI Cancer | 109 | 105 | Lactate | Fluids | Lactate <1.6 | Standard care | 0.92 | 3.8 | 22.94 | 33.3 |

| Wilson et al. [94] | 1999 | 4 | Major surgery | 92 | 46 | PAC | Fluid and inotropes | DO2I >600 | Standard care | 3.26 | 17.4 | 41.3 | 60.87 |

| Ziegler et al. [95] | 1997 | 2 | Vascular | 32 | 40 | PAC | Fluid and inotropes | PAOP >12 | Standard care | 9.38 | 5 | 25 | 27.5 |

CI, cardiac index (ml/minute/m2); CVP, central venous pressure (cmH2O); CVC, central venous catheter; DO2I, oxygen delivery index (ml/minute/m2); FTc, corrected flow time; GDT, goal-directed therapy; Hb, haemoglobin (g/dl); Hct, haematocrit (%); HR, heart rate (beats/minute); ITBV, intrathoracic blood volume; VO2, oxygen consumption (ml/minute); MAP, mean arterial pressure (mmHg); NS, not stated; O2ER, oxygen extraction ratio (%); OD, oesophageal Doppler; PAC, pulmonary artery catheter; PAOP, pulmonary artery occlusion pressure (mmHg); PAWP, pulmonary artery wedge pressure (mmHg); PP, pulse pressure; PPV, pulse pressure variation; PVI, plethysmographic variability index; SAO2, aterial oxygen saturation; sBP, systolic blood pressure (mmHg); SpO2, oxygen saturation (%); SV, stroke volume (ml); SVR, systemic vascular resistance (dynes-s/cm5); SVV, stroke volume variation (%); UO, urine output (ml/kg/h); VO2, oxygen consumption (ml/minute).

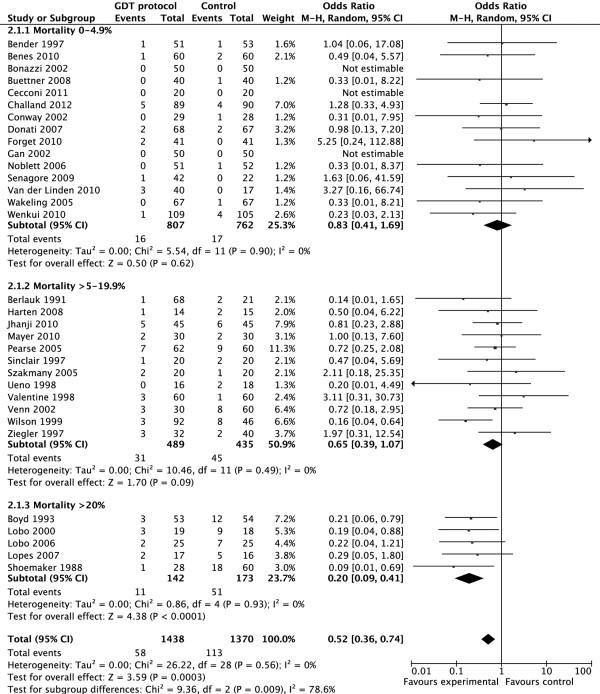

Mortality

Three studies did not report any deaths in the control or intervention group. All 32 studies included mortality rates (Figure 2). Although there was an overall benefit on mortality (OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.74; P = 0.003), subgroup analyses revealed that mortality benefit was seen only in studies that included extremely high risk patients (OR 0.20, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.41; P < 0.0001) but not for the intermediate-risk patients (OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.41 to 1.69; P = 0.62). There was a trend towards a reduction in mortality in the high risk group (OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.07; P = 0.09; Figure 2). Further subgroup analyses of mortality as an endpoint revealed that mortality was reduced in the studies using a pulmonary artery catheter (OR 0.3, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.60; P = 0.0007), fluids and inotropes as opposed to fluids alone (OR 0.41, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.73; P = 0.002), cardiac index or oxygen delivery index as a goal (OR 0.36, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.36; P = 0.0003), and a supranormal resuscitation target (OR 0.27, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.47; P < 0.00001) (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of goal-directed therapy (GDT) in protocol group versus control group on mortality rate, grouped by control group mortality rates. CI, confidence interval; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel.

Table 2.

Mortality by subgroup analysis

| Number of studies | Number of patients in GDT group | Mortality in GDT group (%) | Number of patients in control group | Mortality in control group (%) | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk group | ||||||||

| Intermediate risk | 15 | 807 | 16 (2.0) | 762 | 17(2.2) | 0.83 | 0.41-1.69 | 0.62 |

| High risk | 12 | 489 | 31 (6.3) | 435 | 45 (10.3) | 0.65 | 0.39-1.07 | 0.09 |

| Extremely high risk | 5 | 142 | 11 (7.7) | 173 | 51 (29.5) | 0.2 | 0.09-0.41 | <0.0001 |

| Fluid/inotropes | ||||||||

| Fluid | 16 | 732 | 25 (3.4) | 738 | 38 (5.1) | 0.72 | 0.42-1.23 | 0.23 |

| Fluid + inotrope | 16 | 706 | 33 (4.7) | 632 | 75 (11.9) | 0.41 | 0.23-0.73 | 0.002 |

| Goal | ||||||||

| Supranormal | 9 | 365 | 19 (5.2) | 351 | 65 (18.5) | 0.27 | 0.15-0.47 | <0.00001 |

| Normal | 23 | 1073 | 39 (3.6) | 1,019 | 48 (4.7) | 0.80 | 0.51-1.27 | 0.35 |

| Target | ||||||||

| CI/DO2I | 15 | 674 | 30 (4.5) | 592 | 73 (12.3) | 0.36 | 0.21-0.36 | 0.0003 |

| FTc/SV | 9 | 423 | 15 (3.5) | 434 | 23 (5.3) | 0.78 | 0.40-1.52 | 0.46 |

| Other | 8 | 341 | 13 (3.8) | 344 | 17 (4.9) | 0.78 | 0..35-1.72 | 0.54 |

| Type of monitor | ||||||||

| PAC | 11 | 494 | 20 (4.0) | 445 | 62 (13.9) | 0.3 | 0.15-0.6 | 0.0007 |

| ODM | 8 | 378 | 10 (2.6) | 389 | 17 (4.4) | 0.77 | 0.35-1.69 | 0.51 |

| Other | 13 | 566 | 28 (4.9 | 536 | 34 (6.3) | 0.74 | 0.43-1.28 | 0.28 |

CI, cardiac index (ml/minute/m2); DO2I, oxygen delivery index (ml/minute/m2); FTc, corrected flow time; ODM, oesophageal doppler monitor; PAC, pulmonary artery catheter; SV, stroke volume (ml).

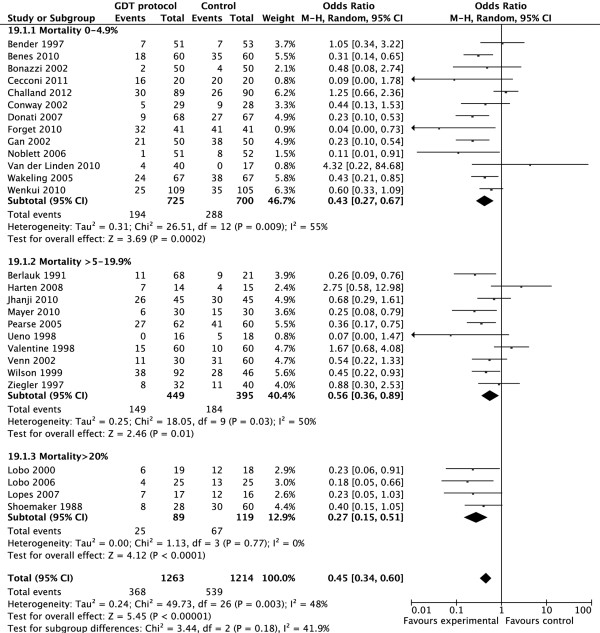

Morbidity

Twenty-seven studies (including 2,477 patients) reported the number of patients with postoperative complications. Meta-analysis of these studies revealed an overall significant reduction in complication rates (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.60; P < 0.00001; Figure 3). Consistent with the mortality benefits, the reduction in morbidity was greatest in the extremely high-risk group (OR 0.27, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.51; P < 0.0001). However, there was also a significant morbidity benefit in the intermediate risk group (OR 0.43, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.67; P = 0.0002) and the high-risk groups (OR 0.56, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.89; P = 0.01) (Figure 3). The reduction in the number of patients suffering postoperative complications was seen across all subgroups, apart from studies that did not use the oxygen delivery index (DO2I; ml/minute/m2), the cardiac index (CI; ml/minute/m2), stroke volume (SV; ml), or corrected flow time (FTc) as a goal (OR 0.48, 95% CI 0.22 to 1.04; P = 0.06), although this approached statistical significance (Table 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of goal-directed therapy (GDT) in protocol group versus control group on the number of patients with complications, grouped by control group mortality rates. CI, confidence interval; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel.

Table 3.

Complications by subgroup analysis

| Number of studies | Number of patients in GDT group | Patients with complications in GDT group (%) | Number of patients in control group | Patients with complications in control group (%) | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk group | ||||||||

| Intermediate risk | 13 | 727 | 194(26.7) | 698 | 288 (41.3) | 0.43 | 0.27-0.67 | 0.0002 |

| High risk | 10 | 449 | 149 (33.2) | 395 | 184 (46.6) | 0.56 | 0.36-0.89 | 0.01 |

| Extremely high risk | 4 | 89 | 25 (28.1) | 119 | 67 (56.3) | 0.27 | 0.15-0.51 | <0.0001 |

| Fluid/inotropes | ||||||||

| Fluid | 12 | 610 | 198 (32.5) | 636 | 299 (47.0) | 0.47 | 0.30-0.73 | 0.0007 |

| Fluid + inotrope | 15 | 653 | 170 (26.0) | 578 | 240 (41.5) | 0.44 | 0.30-0.64 | <0.0001 |

| Goal | ||||||||

| Supranormal | 8 | 312 | 101 (32.4) | 297 | 153 (51.5) | 0.34 | 0.23-0.51 | <0.00001 |

| Normal | 19 | 951 | 267 (28.1) | 917 | 386 (42.1) | 0.51 | 0.36-0.73 | 0.0002 |

| Target | ||||||||

| CI/DO2I | 14 | 621 | 162 (26.1) | 538 | 229 (42.6) | 0.41 | 0.28-0.61 | <0.0001 |

| FTc/SV | 7 | 361 | 118 (32.7) | 392 | 180 (45.9) | 0.50 | 0.30-0.84 | 0.009 |

| Other | 6 | 281 | 88 (31.3) | 284 | 130 (45.8) | 0.48 | 0.22-1.04 | 0.06 |

| Type of monitor | ||||||||

| PAC | 10 | 441 | 99 (22.4) | 391 | 129 (33.0) | 0.49 | 0.30-0.80 | 0.005 |

| ODM | 6 | 316 | 92 (29.1) | 347 | 150 (43.2) | 0.46 | 0.25-0.86 | 0.01 |

| Other | 1! | 506 | 177 (35.0) | 476 | 260 (54.6) | 0.41 | 0.26-0.64 | 0.0001 |

CI, cardiac index (ml/minute/m2); DO2I, oxygen delivery index (ml/minute/m2); FTc, corrected flow time; ODM, oesophageal doppler monitor; PAC, pulmonary artery catheter; SV, stroke volume (ml)

Discussion

We believe that GDT in high-risk surgical patients is likely to have the greatest benefit if carried out early, in the right patient cohort and with a clearly defined protocol. We performed this meta-analysis to test the hypothesis that patients with the highest perioperative risk gain the greatest benefits from GDT. Studies without clearly defined GDT protocols and studies that initiated GDT late in the postoperative course were therefore excluded from our meta-analysis. Studies were stratified into different risk groups based on the mortality rate of the control group in the study. Heterogeneity in the year of study, patient demographics, type and urgency of surgery, and health care facilities among the different studies are likely to account for the difference in mortality rates.

A reduction in mortality associated with GDT was seen only in the extremely high-risk group of patients (baseline mortality rate of >20%). A baseline mortality rate of >20% is unusual in current practice [4,96]; in this sense it is interesting to note that two of five studies with a baseline mortality rate of >20% were carried out within the past decade. Neither of these studies demonstrated a survival benefit with GDT [80,97]. One of these studies demonstrated a reduction in complication rates [97], whilst the other demonstrated a trend towards a reduction in complication rates [80].

Supranormal physiological targets, targeting DO2I or CI, the use of inotropes in addition to fluids, and the use of a PAC were also associated with an improvement in survival. As first demonstrated by Shoemaker and colleagues [19], a supra normal physiological target of global oxygen delivery to ameliorate the oxygen deficit incurred during major surgery is associated with a survival benefit. This is likely to explain the other associations with an improvement in morbidity across all risk groups. The combination of fluids and inotropes is more likely to achieve a supranormal physiological target, as opposed to fluids alone. All eight studies using the oesophageal doppler used fluids alone, reflected by the lack of mortality benefit with the use of FTc or SV as a target. The survival benefit associated with the use of PACs is unlikely to be due to the use of the PACs per se. The survival benefit associated with PAC use may be explained by a number of factors. These include the ability to measure and therefore achieve supranormal DO2I, and the use of inotropes in addition to fluids in all studies using a PAC.

The reduction in the number of patients suffering postoperative complications was seen across all sub groups, apart from studies that did not use DO2I, CI, SV, or FTc as a goal. However, there was a trend towards fewer complications among the GDT cohort in these studies. Goals used by these studies included lactate, pulse pressure variation, plethysmographic variability index, pulmonary artery occlusion pressure, oxygen extraction ratio, and intrathoracic blood volume [73,74,76,80,87,93,95]. Consistent with the trends seen with mortality, the reduction in complication rates was most profound in the extremely high-risk group of patients, protocols with supranormal physiological targets, targeting DO2I or CI, and the use of inotropes in addition to fluids. In contrast to the benefits seen in mortality, however, the subgroup using the 'other cardiac output monitors' had a greater reduction in complication rate than the subgroup using the PAC. This may relate to the complexity and invasive nature of the PAC in comparison to less invasive cardiac output monitors [98-100].

There remains significant heterogeneity in complication rates among postoperative patients in different centres [4,96]. Although differences in patient demographics are not modifiable, optimal management of the high-risk surgical patient during the perioperative phase may improve overall outcomes. Despite a requirement for an increase in healthcare resources to offer early GDT to high-risk surgical patients, reductions in immediate postoperative complications translate to overall benefits in healthcare costs. Any perceived increase in resource allocation results in a lower patient mortality and morbidity, and therefore a financial saving [101]. Furthermore, reduction in immediate postoperative complications has far-reaching effects, with a potential beneficial effect on long-term survival [102].

This meta-analysis includes trials from 1988 to 2011.As surgical techniques, perioperative care, and patient selection have been refined over these years, the overall mortality of patients has reduced. As such, the applicability of historical trials to current day practice may not be valid. This has recently been evaluated in a meta-analysis of 29 perioperative GDT trials carried out between 1995 and 2008 [5]. There was an approximate halving of mortality rates in the control group every decade (29.5%, 13.5%, 7%). Despite a reduction in mortality rate, the morbidity rate remained constant, with approximately a third of patients experiencing postoperative complications. Perioperative GDT should therefore offer a reduction in complication rates in current practice.

We acknowledge that there is an element of subjectivity in our decision to include trials in this meta-analysis. Many studies were conducted in single centres with limited patient numbers, and not all studies conducted were of a high quality design. This is reflected by the median Jadad score of 3. The effect of study quality on outcomes of GDT trials has been analysed in a recent meta-analysis [5]. Most perioperative GDT trials were singe-centre studies, and only a few were conducted in a double-blind manner. In contrast to the lower quality studies, the higher quality studies (defined as a Jadad score of at least 3) did not demonstrate any benefit in mortality reduction. However, the beneficial effect of reduction in perioperative complication rates was evident irrespective of trial quality.

One of the main limitations of this study is the lack of data on the volume and type of fluids given, and the dose of inotropes used due to variation and inconsistencies in reporting. However, it must be emphasised that the absolute volume of fluids used per se is not as important as the way in which fluid is given. Fluid therapy must be titrated against a patient's response to a fluid challenge, with the use of haemodynamic monitoring [103]. Such 'goal-directed' fluid therapy must also be given at the right time, as GDT is not beneficial after complications have already developed [104,105].

One of the other limitations is missing data on the number of patients with complications, due to variations in reporting of complications in the literature, with some studies reporting the number of complications as opposed to the number of patients with complications. Furthermore, we acknowledge that the definitions and coding of complications are likely to vary between studies. We have analysed data extracted from studies, rather than data of individual patients. As some of the studies included were carried out several years ago, obtaining data on individual patients would not have been possible. Despite these limitations, the results remain consistent across many subgroups of patients, and are consistent with other recent meta-analyses, supporting our hypothesis [5,106] and the recent EUSOS study which showed a mortality of 4% [107]. The benefit in terms of reduction of complications of GDT in the intermediate risk group may have implications for the majority of the European surgical population.

Conclusion

Despite heterogeneity in trial quality and design, early GDT among high-risk surgical patients has a significant benefit in reducing rates of complications. There is also an associated reduction in mortality among patients at extremely high risk of perioperative death. GDT is of greatest benefit in patients with the highest risk of mortality.

Note

This is part of a series on Perioperative monitoring, edited by Dr Andrew Rhodes

Abbreviations

CI: cardiac index (ml/minute/m2); DO2I: oxygen delivery index (ml/minute/m2); FTc: corrected flow time; GDT: goal-directed therapy; PAC: pulmonary artery catheter; SV: stroke volume (ml).

Competing interests

MC: Edwards Lifesciences, LiDCO, Deltex, Applied Physiology, Masimo, Bmeye, Cheetah, Imacor (travel expenses, honoraria, advisory board, unrestricted educational grant, research material). MH: lecture fees from Edwards, Deltex, hutchinson technology and LidCO. AR: honoraria and advisory board for LiDCO. Honoraria for Covidien, Edwards Lifesciences and Cheetah. NA: travel expenses from LiDCO.

Box 1.

Search strategies

|

1. MEDLINE database (OVID interface): the Cochrane highlysensitive search strategy was used: #1. randomized Controlled Trials as Topic/ #2. randomized controlled trial/ #3. random Allocation/ #4. double Blind Method/ #5. single Blind Method/ #6. clinical trial/ #7. controlled clinical trial.pt. #8. randomized controlled trial.pt. #9.multicenter study.pt. #10.clinical trial.pt. #11. expClinical Trials as topic/ #12. or/1-11 #13. (clinical adj trial$).tw. #14. ((singl$ or doubl$ or treb$ ortripl$) adj (blind$3 or mask$3)).tw. #15. randomly allocated.tw. #16. (allocated adj2random$).tw. #17. or/13-16 #18. 12 or 17 #19. casereport.tw. #20. letter/ #21.historical article/ #22. or/19-21 #23. 18 not 22 #24. exp surgery/ #25. surgery.tw. #26.surgery.mp. #27. 24 or 25 or 26 #28. exp goal directed/or goaldirected.tw. or goal directed.mp. #29. exp goal oriented/or goaloriented.tw. or goal oriented.mp. #30 exp goal target/or goal target.tw. or goaltarget.mp. #31. exp cardiac output/or cardiac output.tw. or cardiac output.mp. #32. exp cardiac index/or cardiac index.tw. or cardiac index.mp. #33. exp oxygen delivery/or oxygen delivery.tw. or oxygen delivery.mp. #34. exp oxygen consumption/or oxygen consumption.tw. or oxygen consumption.mp #35. exp cardiac volume/or cardiac volume.tw. or cardiac volume.mp. #36. exp stroke volume/or stroke volume.tw. or strokevolume.mp. #37. exp fluid therapy/or fluid therapy.tw. or fluidtherapy.mp. #38. exp fluid loading/or fluid loading.tw. or fluidloading.mp. #39. exp fluid administration/or fluid administration.tw. orfluid administration.mp. #40. exp optimization/or optimization.tw. or optimization.mp. #41. exp optimisation/or optimisation.tw. oroptimisation.mp. #42. expsupranormal/or supranormal.tw. orsupranormal.mp. #43. exp lactate/orlactate.tw. or lactate.mp. #44. expextraction ratio/or extraction ratio.tw. orextraction ratio.mp. #45. #28 or #29or #30 or #31 or #32 or #33 or #34 or #35or #36 or #37 or #38 or #39 or #0or#41or #42 or #43 or #44 #46. #23and #27 and #45 2. Embase (OVIDinterface): search restricted to the years2009 to 2012: #1. Clinicaltrial/ #2. Randomizedcontrolled trial/ #3.Randomization/ #4.Single blind procedure/ #5. Double blindprocedure/ #6. Crossoverprocedure/ #7. Placebo/ #8. Randomi?ed controlledtrial$.tw. #9. Rct.tw. #10. Random allocation.tw. #11.Random allocated.tw |

#12. Allocated randomly.tw. #13.(allocated adj2 random).tw. #14. Single blind$.tw. #15.Double blind$.tw. #16.Placebo$.tw #17.Prospectie study/ #18. Or/1-17 #19. Casestudy/ #20. Case report.tw. #21. Abstract report/or letter/ #22. Or/19-21 #23. 18 not22 #24. surgery #25. expsurgery/or surgery #26.surg$ #27. 24 or 25or 26 #28. exp heart/or heart.mp.)and output.mp. #29. expheart output/or heart output.mp. #30. goal directed #31. goaloriented #32. goal target #33. exp heart index/or heartindex.mp. #34. exp heart strokevolume/or heart stroke volume.mp. #35. expoxygenconsumption/or oxygen consumption.mp. #36. oxygendelivery.mp. #37. exp fluidtherapy/ #38. fluidadministration.mp #39. fluidloading.mp. #40. hemodynamic.mp #41. supranormal.mp. #42.optimisation.mp. #43. optimization.mp. #44. exp lactate/ #45. extraction ratio.mp #46. #28 or #29 or #30 or #31 or #32 or #33 or #34 or #35 or #36 or #37 or #38 or #39 or #40 or #41 or #42 or #43 or #44 or #45 #47. #23 and #27 and #46 3. Cochrane clinical trials database (CENTRAL): #1. surgery in Trials #2. surgical* in Trials #3. surgery* in Trials #4. #1 OR #2 OR #3 #5. cardiac near output* in trials #6. cardiac near volume* in Trials #7. cardiac near index* in Trials #8. oxygen near delivery* in Trials #9. oxygen near consumption* in Trials #10. supranormal* in Trials #11. stroke near volume* in Trials #12. fluid near therapy* in Trials #13. fluid near administration* in Trials #14. fluid near loading* in Trials #15. extraction near ratio* in Trials #16. lactate* in Trials #17. goal near directed* in Trials * #18. goal near oriented* in Trials #19. goal near target* in Trials #20. Hemodynamic near optimization* in trials #21. Haemodynamic near optimization * in trials #22. Optimization* in trials #23. Optimisation* in trials #24. #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21 OR #22 OR #23 #25. #4 AND#24 |

Contributor Information

Maurizio Cecconi, Email: m.cecconi@nhs.net.

Carlos Corredor, Email: carloscorredor@doctors.org.uk.

Nishkantha Arulkumaran, Email: nish_arul@yahoo.com.

Gihan Abuella, Email: g.abuella@gmail.com.

Jonathan Ball, Email: jball@sgul.ac.uk.

R Michael Grounds, Email: michael.grounds@stgeorges.nhs.uk.

Mark Hamilton, Email: markhamilton@nhs.net.

Andrew Rhodes, Email: andrewrhodes@nhs.net.

References

- Cullinane M, Gray A, Hargraves C, Lansdown M, Martin I, Schubert M. Who Operates When? II. The 2003 Report of the National Confidential Enquiry into Peri-operative Deaths. http://www.ncepod.org.uk/2003wow.htm

- Jhanji S, Thomas B, Ely A, Watson D, Hinds CJ, Pearse RM. Mortality and utilisation of critical care resources amongst high-risk surgical patients in a large NHS trust. Anaesthesia. 2008;63:695–700. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2008.05560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khuri SF, Henderson WG, DePalma RG, Mosca C, Healey NA, Kumbhani DJ. Determinants of long-term survival after major surgery and the adverse effect of postoperative complications. Ann Surg. 2005;242:326–341. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000179621.33268.83. discussion 341-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearse RM, Harrison DA, James P, Watson D, Hinds C, Rhodes A, Grounds RM, Bennett ED. Identification and characterisation of the high-risk surgical population in the United Kingdom. Crit Care. 2006;10:R81. doi: 10.1186/cc4928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton MA, Cecconi M, Rhodes A. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the use of preemptive hemodynamic intervention to improve postoperative outcomes in moderate and high-risk surgical patients. Anesth Analg. 2011;112:1392–1402. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181eeaae5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebre C ME, Glanville J. In: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of interventions Version 501 (updated September 2008) Higgins JPT, Green S. The Cochrane Collaboration, editor. 2008. Searching for studies. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011] 2011. http://www.cochrane-handbook.org The Cochrane collaboration.

- Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd O, Jackson N. How is risk defined in high-risk surgical patient management? Crit Care. 2005;9:390–396. doi: 10.1186/cc3057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bundgaard-Nielsen M, Ruhnau B, Secher NH, Kehlet H. Flow-related techniques for preoperative goal-directed fluid optimization. Br J Anaesth. 2007;98:38–44. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donati A, Cornacchini O, Loggi S, Caporelli S, Conti G, Falcetta S, Alò F, Pagliariccio G, Bruni E, Preiser JC, Pelaia P. A comparison among portal lactate, intramucosal sigmoid Ph, and deltaCO2 (PaCO2-regional Pco2) as indices of complications in patients undergoing abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:1024–1031. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000132543.65095.2C. table of contents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dueck MH, Klimek M, Appenrodt S, Weigand C, Boerner U. Trends but not individual values of central venous oxygen saturation agree with mixed venous oxygen saturation during varying hemodynamic conditions. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:249–257. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200508000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futier E, Robin E, Jabaudon M, Guerin R, Petit A, Bazin JE, Constantin JM, Vallet B. Central venous O2 saturation and venous-to-arterial CO2 difference as complementary tools for goal-directed therapy during high-risk surgery. Crit Care. 2010;14:R193. doi: 10.1186/cc9310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen CC, Bundgaard-Nielsen M, Skovgaard LT, Secher NH, Kehlet H. Stroke volume averaging for individualized goal-directed fluid therapy with oesophageal Doppler. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009;53:34–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2008.01785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natalini G, Rosano A, Taranto M, Faggian B, Vittorielli E, Bernardini A. Arterial versus plethysmographic dynamic indices to test responsiveness for testing fluid administration in hypotensive patients: a clinical trial. Anesth Analg. 2006;103:1478–1484. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000246811.88524.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz RJ, Whitfield GF, LaMura JJ, Raciti A, Krishnamurthy S. The role of physiologic monitoring in patients with fractures of the hip. J Trauma. 1985;25:309–316. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198504000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebat F, Johnson D, Musthafa AA, Watnik M, Moore S, Henry K, Saari M. A multidisciplinary community hospital program for early and rapid resuscitation of shock in nontrauma patients. Chest. 2005;127:1729–1743. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.5.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker WC, Appel PL, Kram HB. Hemodynamic and oxygen transport responses in survivors and nonsurvivors of high-risk surgery. Crit Care Med. 1993;21:977–990. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199307000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez JM, Blasco JA, Roig JV, Maeso-Martinez S, Casal JE, Esteban F, Lic DC. Enhanced recovery in colorectal surgery: a multicentre study. BMC Surg. 2011;11:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-11-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell JB, Renlund DG, Robinson JA, Fowler MB, Oyer PE, Pifarre R, Grady KL, Mullin AV, Menlove RL, Gay WA jr. et al. Effect of preoperative hemodynamic support on survival after cardiac transplantation. Circulation. 1988;78:III78–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley BA, Sucher JF, Todd SR, Gonzalez EA, Kozar RA, Sailors RM, Moore FA. Central venous pressure versus pulmonary artery catheter-directed shock resuscitation. Shock. 2009;32:463–470. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181a20ba9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenwick E, Wilson J, Sculpher M, Claxton K. Pre-operative optimisation employing dopexamine or adrenaline for patients undergoing major elective surgery: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28:599–608. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1257-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandstrup B, Tønnesen H, Beier-Holgersen R, Hjortsø E, Ørding H, Lindorff-Larsen K, Rasmussen MS, Lanng C, Wallin L, Iversen LH, Gramkow CS, Okholm M, Blemmer T, Svendsen PE, Rottensten HH, Thage B, Riis J, Jeppesen IS, Teilum D, Christensen AM, Graungaard B, Pott F. Danish Study Group on Perioperative Fluid Therapy. Effects of intravenous fluid restriction on postoperative complications: comparison of two perioperative fluid regimens: a randomized assessor-blinded multicenter trial. Ann Surg. 2003;238:641–648. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000094387.50865.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futier E, Constantin JM, Petit A, Chanques G, Kwiatkowski F, Flamein R, Slim K, Sapin V, Jaber S, Bazin JE. Conservative vs restrictive individualized goal-directed fluid replacement strategy in major abdominal surgery: A prospective randomized trial. Arch Surg. 2010;145:1193–1200. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser CJ, Shoemaker WC, Turpin I, Goldberg SJ. Oxygen transport responses to colloids and crystalloids in critically ill surgical patients. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1980;150:811–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiltebrand LB, Kimberger O, Amberger M, Brandt S, Kurz A, Sigurdsson GH. Crystalloids versus colloids for goal-directed fluid therapy in major surgery. Crit Care. 2009;13:R40. doi: 10.1186/cc7761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holte K, Foss NB, Andersen J, Valentiner L, Lund C, Bie P, Kehlet H. Liberal or restrictive fluid administration in fast-track colonic surgery: a randomized, double-blind study. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99:500–508. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holte K, Hahn RG, Ravn L, Bertelsen KG, Hansen S, Kehlet H. Influence of "liberal" versus "restrictive" intraoperative fluid administration on elimination of a postoperative fluid load. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:75–79. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200701000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holte K, Klarskov B, Christensen DS, Lund C, Nielsen KG, Bie P, Kehlet H. Liberal versus restrictive fluid administration to improve recovery after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a randomized, double-blind study. Ann Surg. 2004;240:892–899. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000143269.96649.3b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holte K, Kristensen BB, Valentiner L, Foss NB, Husted H, Kehlet H. Liberal versus restrictive fluid management in knee arthroplasty: a randomized, double-blind study. Anesth Analg. 2007;105:465–474. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000263268.08222.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo SM, Ronchi LS, Oliveira NE, Brandao PG, Froes A, Cunrath GS, Nishiyama KG, Netinho JG, Lobo FR. Restrictive strategy of intraoperative fluid maintenance during optimization of oxygen delivery decreases major complications after high-risk surgery. Crit Care. 2011;15:R226. doi: 10.1186/cc10466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisanevich V, Felsenstein I, Almogy G, Weissman C, Einav S, Matot I. Effect of intraoperative fluid management on outcome after intraabdominal surgery. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:25–32. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200507000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldt J, Papsdorf M, Piper S, Padberg W, Hempelmann G. Influence of dopexamine hydrochloride on haemodynamics and regulators of circulation in patients undergoing major abdominal surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1998;42:941–947. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1998.tb05354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies SJ, Yates D, Wilson RJ. Dopexamine has no additional benefit in high-risk patients receiving goal-directed fluid therapy undergoing major abdominal surgery. Anesth Analg. 2011;112:130–138. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181fcea71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinley J, Lynch L, Hubbard K, McCoy D, Cunningham AJ. Dopexamine hydrochloride does not modify hemodynamic response or tissue oxygenation or gut permeability during abdominal aortic surgery. Can J Anaesth. 2001;48:238–244. doi: 10.1007/BF03019752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone MD, Wilson RJT, Cross J, Williams BT. Effect of adding dopexamine to intraoperative volume expansion in patients undergoing major elective abdominal surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2003;91:619–624. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeg245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takala J, Meier-Hellmann A, Eddleston J, Hulstaert P, Sramek V. Effect of dopexamine on outcome after major abdominal surgery: A prospective, randomized, controlled multicenter study. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:3417–3423. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200010000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor PM, Kakani M, Chowdhury U, Choudhury M, Lakshmy, Kiran U. Early goal-directed therapy in moderate to high-risk cardiac surgery patients. Ann Cardiac Anaesth. 2008;11:27–34. doi: 10.4103/0971-9784.38446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magder S, Potter BJ, Varennes BD, Doucette S, Fergusson D. Fluids after cardiac surgery: A pilot study of the use of colloids versus crystalloids. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:2117–2124. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181f3e08c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKendry M, McGloin H, Saberi D, Caudwell L, Brady AR, Singer M. Randomised controlled trial assessing the impact of a nurse delivered, flow monitored protocol for optimisation of circulatory status after cardiac surgery. BMJ. 2004;329:258. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38156.767118.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mythen MG, Webb AR. Perioperative plasma volume expansion reduces the incidence of gut mucosal hypoperfusion during cardiac surgery. Arch Surg. 1995;130:423–429. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1995.01430040085019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polonen P, Ruokonen E, Hippelainen M, Poyhonen M, Takala J. A prospective, randomized study of goal-oriented hemodynamic therapy in cardiac surgical patients. Anesth Analg. 2000;90:1052–1059. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200005000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetkin AA, Kirov MY, Kuzkov VV, Lenkin AI, Eremeev AV, Slastilin VY, Borodin VV, Bjertnaes LJ. Single transpulmonary thermodilution and continuous monitoring of central venous oxygen saturation during off-pump coronary surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009;53:505–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2008.01855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechir M, Puhan MA, Neff SB, Guggenheim M, Wedler V, Stover JF, Stocker R, Neff TA. Early fluid resuscitation with hyperoncotic hydroxyethyl starch 200/0.5 (10%) in severe burn injury. Crit Care. 2010;14:R123. doi: 10.1186/cc9086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chytra I, Pradl R, Bosman R, Pelnar P, Kasal E, Zidkova A. Esophageal Doppler-guided fluid management decreases blood lactate levels in multiple-trauma patients: a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care. 2007;11:R24. doi: 10.1186/cc5703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming A, Bishop M, Shoemaker W, Appel P, Sufficool W, Kuvhenguwha A, Kennedy F, Wo CJ. Prospective trial of supranormal values as goals of resuscitation in severe trauma. Arch Surg. 1992;127:1175–1179. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1992.01420100033006. discussion 1179-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm C, Mayr M, Tegeler J, Horbrand F, Henckel Von Donnersmarck G, Muhlbauer W, Pfeiffer UJ. A clinical randomized study on the effects of invasive monitoring on burn shock resuscitation. Burns. 2004;30:798–807. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivatury RR, Simon RJ, Islam S, Fueg A, Rohman M, Stahl WM. A prospective randomized study of end points of resuscitation after major trauma: global oxygen transport indices versus organ-specific gastric mucosal pH. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;183:145–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller PR, Meredith JW, Chang MC. Randomized, prospective comparison of increased preload versus inotropes in the resuscitation of trauma patients: effects on cardiopulmonary function and visceral perfusion. J Trauma. 1998;44:107–113. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199801000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velmahos GC, Demetriades D, Shoemaker WC, Chan LS, Tatevossian R, Wo CC, Vassiliu P, Cornwell EE 3rd, Murray JA, Roth B, Belzberg H, Asensio JA, Berne TV. Endpoints of resuscitation of critically injured patients: normal or supranormal? A prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2000;232:409–418. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200009000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop MH, Shoemaker WC, Appel PL, Meade P, Ordog GJ, Wasserberger J, Wo CJ, Rimle DA, Kram HB, Umali R. et al. Prospective, randomized trial of survivor values of cardiac index, oxygen delivery, and oxygen consumption as resuscitation endpoints in severe trauma. J Trauma. 1995;38:780–787. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199505000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul M, Dueck M, Herrmann HJ, Holzki J. A randomized, controlled study of fluid management in infants and toddlers during surgery: Hydroxyethyl starch 6% (HES 70/0.5) vs lactated Ringer's solution. Paediatr Anaesth. 2003;13:603–608. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2003.01113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey S, Stevens K, Harrison D, Young D, Brampton W, McCabe C, Singer M, Rowan K. An evaluation of the clinical and cost-effectiveness of pulmonary artery catheters in patient management in intensive care: a systematic review and a randomised controlled trial. Health Technol Assess. 2006;10:iii–iv. doi: 10.3310/hta10290. ix-xi, 1-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichai C, Passeron C, Carles M, Bouregba M, Grimaud D. Prolonged low-dose dopamine infusion induces a transient improvement in renal function in hemodynamically stable, critically ill patients: A single-blind, prospective, controlled study. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:1329–1335. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200005000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen TC, Van Bommel J, Schoonderbeek FJ, Sleeswijk Visser SJ, Van Der Klooster JM, Lima AP, Willemsen SP, Bakker J. Early lactate-guided therapy in intensive care unit patients: A multicenter, open-label, randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:752–761. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200912-1918OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AE, Shapiro NI, Trzeciak S, Arnold RC, Claremont HA, Kline JA. Lactate clearance vs central venous oxygen saturation as goals of early sepsis therapy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2010;303:739–746. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes A, Cusack RJ, Newman PJ, Grounds RM, Bennett ED. A randomised, controlled trial of the pulmonary artery catheter in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28:256–264. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1206-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, Ressler J, Muzzin A, Knoblich B, Peterson E, Tomlanovich M. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1368–1377. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivers EP, Kruse JA, Jacobsen G, Shah K, Loomba M, Otero R, Childs EW. The influence of early hemodynamic optimization on biomarker patterns of severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:2016–2024. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000281637.08984.6E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takala J, Ruokonen E, Tenhunen JJ, Parviainen I, Jakob SM. Early non-invasive cardiac output monitoring in hemodynamically unstable intensive care patients: A multi-center randomized controlled trial. Crit Care. 2011;15:R148. doi: 10.1186/cc10273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattinoni L, Brazzi L, Pelosi P, Latini R, Tognoni G, Pesenti A, Fumagalli R. A trial of goal-oriented hemodynamic therapy in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1025–1032. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199510193331601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandham JD, Hull RD, Brant RF, Knox L, Pineo GF, Doig CJ, Laporta DP, Viner S, Passerini L, Devitt H, Kirby A, Jacka M. Canadian Critical Care Clinical Trials Group. A randomized, controlled trial of the use of pulmonary-artery catheters in high-risk surgical patients. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:5–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender JS, Smith-Meek MA, Jones CE. Routine pulmonary artery catheterization does not reduce morbidity and mortality of elective vascular surgery: results of a prospective, randomized trial. Ann Surg. 1997;226:229–236. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199709000-00002. discussion 236-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benes J, Chytra I, Altmann P, Hluchy M, Kasal E, Svitak R, Pradl R, Stepan M. Intraoperative fluid optimization using stroke volume variation in high risk surgical patients: Results of prospective randomized study. Crit Care. 2010;14:R118. doi: 10.1186/cc9070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlauk JF, Abrams JH, Gilmour IJ, O'Connor SR, Knighton DR, Cerra FB. Preoperative optimization of cardiovascular hemodynamics improves outcome in peripheral vascular surgery. A prospective, randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 1991;214:289–297. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199109000-00011. discussion 298-289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonazzi M, Gentile F, Biasi GM, Migliavacca S, Esposti D, Cipolla M, Marsicano M, Prampolini F, Ornaghi M, Sternjakob S, Tshomba Y. Impact of perioperative haemodynamic monitoring on cardiac morbidity after major vascular surgery in low risk patients. A randomised pilot trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2002;23:445–451. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.2002.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd O, Grounds RM, Bennett ED. A randomized clinical trial of the effect of deliberate perioperative increase of oxygen delivery on mortality in high-risk surgical patients. JAMA. 1993;270:2699–2707. doi: 10.1001/jama.1993.03510220055034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buettner M, Schummer W, Huettemann E, Schenke S, Van Hout N, Sakka SG. Influence of systolic-pressure-variation-guided intraoperative fluid management on organ function and oxygen transport. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101:194–199. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecconi M, Fasano N, Langiano N, Divella M, Costa MG, Rhodes A, Della Rocca G. Goal-directed haemodynamic therapy during elective total hip arthroplasty under regional anaesthesia. Crit Care. 2011;15:R132. doi: 10.1186/cc10246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challand C, Struthers R, Sneyd JR, Erasmus PD, Mellor N, Hosie KB, Minto G. Randomized controlled trial of intraoperative goal-directed fluid therapy in aerobically fit and unfit patients having major colorectal surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2012;108:53–62. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway DH, Mayall R, Abdul-Latif MS, Gilligan S, Tackaberry C. Randomised controlled trial investigating the influence of intravenous fluid titration using oesophageal Doppler monitoring during bowel surgery. Anaesthesia. 2002;57:845–849. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2002.02708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donati A, Loggi S, Preiser JC, Orsetti G, Munch C, Gabbanelli V, Pelaia P, Pietropaoli P. Goal-directed intraoperative therapy reduces morbidity and length of hospital stay in high-risk surgical patients. Chest. 2007;132:1817–1824. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forget P, Lois F, de Kock M. Goal-directed fluid management based on the pulse oximeter-derived pleth variability index reduces lactate levels and improves fluid management. Anesth Analg. 2010;111:910–914. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181eb624f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan TJ, Soppitt A, Maroof M, El-Moalem H, Robertson KM, Moretti E, Dwane P, Glass PSA. Goal-directed intraoperative fluid administration reduces length of hospital stay after major surgery. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:820–826. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200210000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harten J, Crozier JE, McCreath B, Hay A, McMillan DC, McArdle CS, Kinsella J. Effect of intraoperative fluid optimisation on renal function in patients undergoing emergency abdominal surgery: a randomised controlled pilot study (ISRCTN 11799696) Int J Surg. 2008;6:197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhanji S, Vivian-Smith A, Lucena-Amaro S, Watson D, Hinds CJ, Pearse RM. Haemodynamic optimisation improves tissue microvascular flow and oxygenation after major surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Crit Care. 2010;14:R151. doi: 10.1186/cc9220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo SM, Lobo FR, Polachini CA, Patini DS, Yamamoto AE, de Oliveira NE, Serrano P, Sanches HS, Spegiorin MA, Queiroz MM, Christiano AC Jr, Savieiro EF, Alvarez PA, Teixeira SP, Cunrath GS. Prospective, randomized trial comparing fluids and dobutamine optimization of oxygen delivery in high-risk surgical patients [ISRCTN42445141] Crit Care. 2006;10:R72. doi: 10.1186/cc4913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo SM, Salgado PF, Castillo VG, Borim AA, Polachini CA, Palchetti JC, Brienzi SL, de Oliveira GG. Effects of maximizing oxygen delivery on morbidity and mortality in high-risk surgical patients. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:3396–3404. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200010000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes MR, Oliveira MA, Pereira VO, Lemos IP, Auler JO Jr, Michard F. Goal-directed fluid management based on pulse pressure variation monitoring during high-risk surgery: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Crit Care. 2007;11:R100. doi: 10.1186/cc6117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer J, Boldt J, Mengistu AM, Rohm KD, Suttner S. Goal-directed intraoperative therapy based on autocalibrated arterial pressure waveform analysis reduces hospital stay in high-risk surgical patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Crit Care. 2010;14:R18. doi: 10.1186/cc8875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noblett SE, Snowden CP, Shenton BK, Horgan AF. Randomized clinical trial assessing the effect of Doppler-optimized fluid management on outcome after elective colorectal resection. Br J Surg. 2006;93:1069–1076. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearse R, Dawson D, Fawcett J, Rhodes A, Grounds RM, Bennett ED. Early goal-directed therapy after major surgery reduces complications and duration of hospital stay. A randomised, controlled trial [ISRCTN38797445] Crit Care. 2005;9:R687–693. doi: 10.1186/cc3887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senagore AJ, Emery T, Luchtefeld M, Kim D, Dujovny N, Hoedema R. Fluid management for laparoscopic colectomy: a prospective, randomized assessment of goal-directed administration of balanced salt solution or hetastarch coupled with an enhanced recovery program. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1935–1940. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181b4c35e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker WC, Appel PL, Kram HB, Waxman K, Lee TS. Prospective trial of supranormal values of survivors as therapeutic goals in high-risk surgical patients. Chest. 1988;94:1176–1186. doi: 10.1378/chest.94.6.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair S, James S, Singer M. Intraoperative intravascular volume optimisation and length of hospital stay after repair of proximal femoral fracture: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1997;315:909–912. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7113.909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szakmany T, Toth I, Kovacs Z, Leiner T, Mikor A, Koszegi T, Molnar Z. Effects of volumetric vs. pressure-guided fluid therapy on postoperative inflammatory response: a prospective, randomized clinical trial. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:656–663. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2606-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno S, Tanabe G, Yamada H, Kusano C, Yoshidome S, Nuruki K, Yamamoto S, Aikou T. Response of patients with cirrhosis who have undergone partial hepatectomy to treatment aimed at achieving supranormal oxygen delivery and consumption. Surgery. 1998;123:278–286. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6060(98)70180-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine RJ, Duke ML, Inman MH, Grayburn PA, Hagino RT, Kakish HB, Clagett GP. Effectiveness of pulmonary artery catheters in aortic surgery: a randomized trial. J Vasc Surg. 1998;27:203–211. doi: 10.1016/S0741-5214(98)70351-9. discussion 211-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Linden PJ, Dierick A, Wilmin S, Bellens B, De Hert SG. A randomized controlled trial comparing an intraoperative goal-directed strategy with routine clinical practice in patients undergoing peripheral arterial surgery. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2010;27:788–793. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e32833cb2dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venn R, Steele A, Richardson P, Poloniecki J, Grounds M, Newman P. Randomized controlled trial to investigate influence of the fluid challenge on duration of hospital stay and perioperative morbidity in patients with hip fractures. Br J Anaesth. 2002;88:65–71. doi: 10.1093/bja/88.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakeling HG, McFall MR, Jenkins CS, Woods WG, Miles WF, Barclay GR, Fleming SC. Intraoperative oesophageal Doppler guided fluid management shortens postoperative hospital stay after major bowel surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95:634–642. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenkui Y, Ning L, Jianfeng G, Weiqin L, Shaoqiu T, Zhihui T, Tao G, Juanjuan Z, Fengchan X, Hui S, Weiming Z, Jie-Shou L. Restricted peri-operative fluid administration adjusted by serum lactate level improved outcome after major elective surgery for gastrointestinal malignancy. Surgery. 2010;147:542–552. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson J, Woods I, Fawcett J, Whall R, Dibb W, Morris C, McManus E. Reducing the risk of major elective surgery: randomised controlled trial of preoperative optimisation of oxygen delivery. BMJ. 1999;318:1099–1103. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7191.1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler DW, Wright JG, Choban PS, Flancbaum L. A prospective randomized trial of preoperative "optimization" of cardiac function in patients undergoing elective peripheral vascular surgery. Surgery. 1997;122:584–592. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6060(97)90132-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaferi AA, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Variation in hospital mortality associated with inpatient surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1368–1375. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0903048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo SM, Lobo FR, Polachini CA, Patini DS, Yamamoto AE, de Oliveira NE, Serrano P, Sanches HS, Spegiorin MA, Queiroz MM, Christiano AC Jr, Savieiro EF, Alvarez PA, Teixeira SP, Cunrath GS. Prospective, randomized trial comparing fluids and dobutamine optimization of oxygen delivery in high-risk surgical patients [ISRCTN42445141] Crit Care. 2006;10:R72. doi: 10.1186/cc4913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer CK, Cecconi M, Marx G, della Rocca G. Minimally invasive haemodynamic monitoring. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2009;26:996–1002. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e3283300d55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors AF Jr, Speroff T, Dawson NV, Thomas C, Harrell FE Jr, Wagner D, Desbiens N, Goldman L, Wu AW, Califf RM, Fulkerson WJ Jr, Vidaillet H, Broste S, Bellamy P, Lynn J, Knaus WA. The effectiveness of right heart catheterization in the initial care of critically ill patients. SUPPORT Investigators. JAMA. 1996;276:889–897. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03540110043030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finfer S, Delaney A. Pulmonary artery catheters. BMJ. 2006;333:930–931. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39017.459907.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest JF, Boyd O, Hart WM, Grounds RM, Bennett ED. A cost analysis of a treatment policy of a deliberate perioperative increase in oxygen delivery in high risk surgical patients. Intensive Care Med. 1997;23:85–90. doi: 10.1007/s001340050295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes A, Cecconi M, Hamilton M, Poloniecki J, Woods J, Boyd O, Bennett D, Grounds RM. Goal-directed therapy in high-risk surgical patients: a 15-year follow-up study. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:1327–1332. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-1869-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecconi M, Parsons AK, Rhodes A. What is a fluid challenge? Curr Opin Crit Care. 2011;17:290–295. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32834699cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattinoni L, Brazzi L, Pelosi P, Latini R, Tognoni G, Pesenti A, Fumagalli R. A trial of goal-oriented hemodynamic therapy in critically ill patients. SvO2 Collaborative Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1025–1032. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199510193331601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes MA, Timmins AC, Yau EH, Palazzo M, Hinds CJ, Watson D. Elevation of systemic oxygen delivery in the treatment of critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1717–1722. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406163302404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurgel ST, do Nascimento P Jr. Maintaining tissue perfusion in high-risk surgical patients: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Anesth Analg. 2011;112:1384–1391. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182055384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearse R, Moreno RP, Bauer P, Pelosi P, Metniz P, Spies C, Vallet B, Vincent JL, Hoeft A, Rhodes A. Mortality after surgery in Europe: a 7 day cohort study. Lancet. 2012;380:1059–1065. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61148-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]