Abstract

Changes in vascular function, such as endothelial dysfunction are linked to the progression of heart failure (HF) and poorer outcomes, such as increased hospitalisations. Exercise training may positively influence endothelial function in HF patients with reduced ejection fraction. The aim of this manuscript is to summarise HF studies evaluating the influence of exercise training on endothelial function as measured by flow mediated vasodilation as a primary outcome and to provide recommendations for future research studies designed to improve peripheral vascular function in HF. Databases were searched for studies published between 1995 and December 2011. Two reviewers determined eligibility and extracted information on study characteristics and quality, exercise interventions, and endothelial function. Eleven articles (N = 318 HF participants with an ejection fraction <40%) were eligible for full review. Aerobic, resistance, or combined exercise training improved endothelium-dependent vasodilation as measured by ultrasound or plethysmography. There is less evidence supporting improvement in endothelium-independent function with exercise training. Sample sizes were small and predominantly male. Future research is needed to address the best mode and optimal dose of exercise for all patients with HF including women and subgroups with specific co-morbidities.

Keywords: Heart failure, Exercise, Endothelium, Flow-mediated dilation

Introduction

Abnormalities in peripheral vasodilation, in particular endothelial dysfunction, contribute to the development and progression of heart failure (HF). Endothelial dysfunction may also be one of the mechanisms underlying exercise intolerance in HF. Endothelial dysfunction may result in impaired afterload reduction, alterations in vascular tone and abnormal responses to circulating stimuli, all of which can impact exercise capacity and tolerance. In addition, endothelial dysfunction is also associated with an increased risk for mortality in HF patients with reduced ejection fraction (HRrEF) <40% [1–3]. A growing body of evidence suggests exercise training improves exercise intolerance and endothelial dysfunction for patients with HFrEF [4–10]. Flow-mediated dilation (FMD) is a well-established measure of assessing endothelial function [11,12]. High-resolution ultrasound and plethysmography are commonly used to measure FMD in peripheral blood vessels (e.g., brachial artery) in response to exercise training. The aim of this manuscript is to summarise the prospective human HF studies evaluating the influence of exercise training on endothelial function as measured by FMD as a primary outcome and to provide recommendations for future research studies designed to improve peripheral vascular function in HF.

Methods

Search Strategy

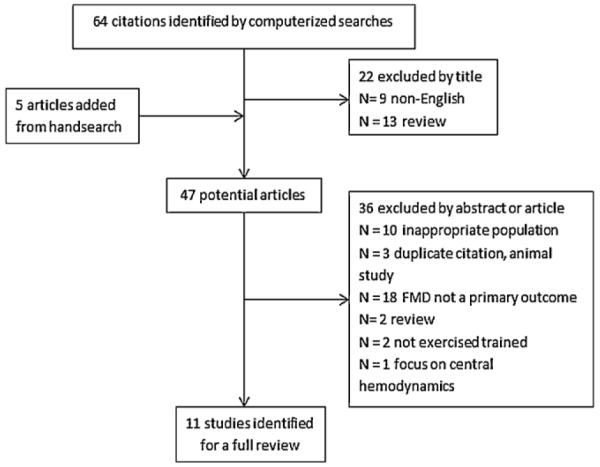

We searched PubMed, CINAHL, and Cochrane databases (1995–December 2011) using a combination of the search terms “heart failure, congestive heart failure, exercise training, exercise, physical training, endothelium, and endothelial function.” Search criteria were set to include only human studies. The search yielded 64 citations. We excluded non-English articles and reviews. Forty-two articles were selected as potentially relevant and independently reviewed by two authors (K.V. and S.P.). Five articles were added after handsearching reference lists. Of these, 11 were met the following inclusion criteria: (1) sample population was patients with chronic HFrEF with ejection fraction (EF) <40%; (2) high-resolution ultrasound or plethysmography was used to assess peripheral vasoreactivity as a primary outcome following a period of weekly exercise and; (3) use of a prospective single-group experimental design, nonrandomised or randomised study design. Eligible studies used a weekly exercise intervention incorporating aerobic (endurance) and/or resistance (strength) training. The exercise training could be supervised or unsupervised and performed in an inpatient, outpatient, home-based, or combined setting. The study searching and selection process is summarised in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

The summary of the literature search and selection process.

Data Extraction and Assessment of Methodological Quality

Data extraction was conducted independently by one reviewer (KV) and checked by a second author (SP). Any disagreements were settled by discussion or third author (MP). Relevant data related to the inclusion criteria (study design, sample characteristics, the frequency, duration, intensity and modality of exercise, outcomes), risk of bias (randomisation, blinding, selective outcome reporting) and results were extracted.

We did not rate the studies using a numerical quality score. Rather, we used a component approach and assessed key dimensions for each study. The quality of the studies were reviewed for clear definition of control and HF sample, baseline comparisons for parallel groups, risk of bias (e.g., group assignment, blinding of outcome assessment), control of confounding factors and statistical reporting. Given the nature of the studies, we did not expect subjects or study personnel who supervised the exercise sessions to be blinded to group assignment.

Results

Cohort Characteristics

Details of the 11 selected studies (N = 318 total HF subjects) are summarised in Table 1. Most studies recruited convenience samples. Sixty-seven percent (n = 7) exclusively enrolled men, while no study indicated race and ethnicity. The sample size across studies varied from 7 to 59 [13,17]. The majority of patients were New York Heart Association (NYHA) classes II–III patients with ischaemic heart disease; however, Miche et al. [20] recruited patients with NYHA class I–III HF, and Erbs et al. [22] specifically recruited subjects with ischaemic heart disease and advanced chronic HF (NYHA IIIb; n = 37). Most investigators required subjects to be “clinically stable,” i.e., no hospitalisations and optimised on medications for two [19,22] or three months [15–17,21,23] prior to enrollment. Among studies, the range of the mean age was 44–75 years. One study [21] included patients with a mean age of 70 years and recruited patients >80 years of age (n = 12).

Table 1.

Summary of Study Characteristics.

| Study | Study Design and Participants | HF Aetiology | Outcomes, Limitations Confounders | FMD Method | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bank et al. [13] |

|

Idiopathic and ischaemic CM |

MAP, HR, forearm volume, forearm blood flow measured at baseline and post-exercise in response to 5 min of ischaemia, ACH and SNP in trained and untrained arm Limitation: significant differences between intervention group (older, all male) and control group (younger, male and female); small sample size |

Plethysmography: Forearm |

MAP, HR or forearm blood volume did not significantly change after handgrip exercises for either group In the healthy control group, endothelium-dependent vasodilation in response to ACH increased following exercise Flow-mediated dilation increased only during peak blood flow post-exercise in the healthy control group Endothelium-dependent and flow-mediated vasodilation did not significantly change post-exercise compared with baseline in the HF group Endothelium-independent vasodilation diameters did not change post-exercise from baseline in either group |

| Maiorana et al. [14] |

|

Coronary heart disease; idiopathic CM |

MAP, HR, HDL, LDL Forearm blood flow response at baseline and post-exercise in response to 10 min of ischaemia, ACH and SNP Limitations: all male, small sample size; data analysed by change ratio; longer period ischaemia |

Plethysmography: Radial artery |

MAP, resting HR, HDL, and LDL were not significantly different between the trained (cycling and resistance) and untrained periods Endothelium-dependent vasodilation in response to ACH showed a significant increase post exercise training (p < 0.05, 2-way ANOVA) Endothelium-independent vasodilation assessed by forearm blood flow increased post-exercise training but did not reach significance (p = 0.06) Within-group comparisons for endothelium-dependent vasodilation and endothelium-independent vasodilation reached significance when analysed by ratio (percent change from preceding baseline values) between the trained and untrained periods (p < 0.05, ANOVA) |

| Linke et al. [15] |

|

Ischaemic heart disease; dilated CM |

Vessel diameter at baseline and post exercise in response to 5 min of ischaemia, ACH and NTG Limitations: baseline vessel diameter (3.42±0.12 mm) in the intervention group was significantly larger (p < 0.05) compared with control group (2.99 ± 0.13 mm); unclear if investigators were blinded |

Ultrasound: Radial artery |

Endothelium-dependent vasodilation in response to ACH significantly increased after 4 weeks of cycling (p < 0.001) compared with baseline in the exercise group; response to ACH was unchanged in control group Endothelium-independent vasodilation was unchanged from baseline in either group Flow-mediated dilation diameter significantly increased from baseline in the treatment group (374±57 μm to 570±76 μm; p < 0.01); vessel diameter did not change from baseline in the control group |

| Kobayashi et al. [16] |

|

Ischaemic heart disease; dilated CM |

NE, ET-1, IL-6, BNP, baseline diameter and blood flow in brachial and tibial artery post exercise in response to 5 min of ischaemia in trained and untrained limbs Limitations: mean age and peak VO2 differed between control and exercise groups (p < 0.05); smoking status of subjects unclear; medications changed during protocol; vessel diameter measurement inconsistent |

Ultrasound: Brachial artery (non-exercised) tibial artery (exercised) |

NE, ET-1, IL-6, and BNP levels did not significantly change from baseline parameters in either group Flow-mediated vasodilation did not change from baseline in the brachial or tibial artery of the control group Flow-mediated vasodilation in the brachial artery did not change from baseline in the HF exercise group (4.34±0.45% vs. 4.34±0.43%) Flow-mediated vasodilation in the tibial artery significantly increased from baseline in the HF exercise group (3.64 ± 0.26% vs. 6.44 ± 0.56%; p < 0.01) Reactive hyperaemia (percent increase in mean blood flow after cuff deflation) did not significantly change from baseline in either group for the upper or lower limb |

| Belardinelli et al. [17] |

|

Ischaemic heart disease; idiopathic CM |

CPET, QoL scores, sexual activity profile, coronary risk factors, vessel diameter in response to 4.5 min of ischaemia, ACH, and NTG Limitations: all male; cardiac risk factors not measured; smokers and non-smokers included |

Ultrasound: Brachial artery |

CPET parameters, QoL and sexual activity prolife scores significantly improved in the exercise group; no changes in control group Coronary risk factors improved in the exercise group compared with the control group after training Flow-mediated dilation diameter improved only in the exercise group (2.29±1.13% to 5.04±1.7%; p = 0.0001) Endothelium-independent vasodilation vessel diameter was unchanged in either group |

| Parnell et al. [18] |

|

Ischaemic heart disease; other |

6 MW distance, forearm blood flow in response to ACH, SNP, L-arginine transport (based on plasma levels) Limitations: all male; differences at baseline in triacylglycerol levels between groups; smoking status of subjects unknown; unclear if different aspects of data analysis were blinded |

Plethysmography: Forearm |

6 MW distance increased from baseline (496±21 m to 561±17 m; p = 0.005) in the exercise group post aerobic and light resistance training Forearm blood flow response to ACH and SNP significantly increased from baseline (p = 0.01 and p = 0.006, respectively) in the exercise group post exercise L-Arginine transport increased significantly in the exercise group (p = 0.04) and positively correlated with exercise training (n = 10; r = 0.69, p = 0.02) No significant differences were found for 6 MW distance, forearm blood flow, and L-arginine transport from baseline in the control group |

| Belardinelli et al. [19] |

|

All ischaemic heart disease |

CPET and echocardiographic parameters, QoL scores, vessel diameter in response to 4.5 min of ischaemia, NTG Limitations: all male sample; smoking status unclear |

Ultrasound: Brachial artery |

CPET parameters significantly improved in the exercise group post exercise; no significant changes in the control groups QoL scores significantly improved in the ICD/CRT exercise group (p < 0.001) Echocardiographic parameters showed the greatest improvement in the ICD/CRT exercise group compared with CRT device group or both control groups No significant differences in the endothelium-independent vasodilation vessel diameter from baseline in any group Flow-mediated dilation vessel diameter significantly improved in the exercise group regardless of the type of device therapy |

| Miche et al. [20] |

|

Ischaemic heart disease; other |

CPET and echocardiographic parameters, QoL scores, vessel diameter in response to 4.5 min of ischaemia, NTG Limitations: smoking status unknown; unclear if different aspects of data analysis were blinded; medications were changed during the study |

Ultrasound: Brachial artery |

LVEF and VO2 max significantly increased post exercise for both groups (df 1, F = 0.001; p ≤ 0.05) Endothelium-independent vasodilation did not significantly improve post exercise in the diabetic (10.5 ± 5.6.6% vs. 8.7 ± 4.1%) or non-diabetic (13.2 ± 5.8% vs. 12.3 ± 6.3%) group Flow-mediated dilation vessel diameter did not significantly change from baseline post exercise in the diabetic (5.1±3.6% vs. 4.9±2.5%) or non-diabetic (6.8±4.5% vs. 7.6±4.0%) group No significant correlation between the change in flow-mediated dilation and VO2 max |

| Wisløff et al. [21] |

|

Ischaemic aetiology post infarct on beta blockers | CPET and echocardiographic parameters, QoL scores, skeletal muscle metabolism, Ca++ reuptake assay, vessel diameter in response to 5 min of ischaemia, NTG Limitation: small predominantly male sample; control group received more than usual care-met every 3 weeks for 47 min of exercise; smoking status unknown; generalisability limited |

Ultrasound: Brachial artery |

Peak VO2 increased post exercise in the AIT and MCT group (46% and 14%, respectively; p = 0.21) QoL scores improved post exercise in the AIT (p < 0.001) and MCT (p < 0.01) groups; no change in the control group Echocardiographic parameters improved and skeletal muscle Ca++ reuptake increased post exercise in the AIT group Flow-mediated dilation improved after training for the intervention groups but was greater for AIT group than MCT group (p < 0.05) Endothelium-independent vasodilation diameter did not change for any group |

| Erbs et al. [22] |

|

Ischaemic heart disease |

CPET and echocardiographic parameters, measures of oxidative stress and neorevascularisation of skeletal muscle, vessel diameter in response to 5 min of ischaemia Limitations: HF exercise group had a higher incidence of atrial fibrillation; 5 subjects had cardiac cachexia; unclear if medications changed; radial artery diameter was blunted at baseline; flow velocity was at rest and at peak hyperaemia were not determined; endothelium-independent vasodilation not studied |

Ultrasound: Radial artery |

VO2 max, ventilatory threshold, LV performance measures improved from baseline in the exercise group; no significant changes in the CPET of echocardiographic parameters for the control group Flow-mediated dilation significantly improved from baseline in the exercise group (absolute change in vessel diameter: 415±86 μm; percent change 6.1±2.5% to 13.6±2.2%; p < 0.01) Increased number of progenitor cells, capillary density, and neorevascularisation growth factors with a reduction in markers of oxidative stress within the treatment group; no changes for these factors in the control group |

| Dean et al., 2011 [23] |

|

Idiopathic, ischaemic, congenital, valvular, primary pulmonary HTN, postpartum CM |

Forearm maximal voluntary contraction, vessel diameter, blood flow measured at baseline and post-exercise in response to 2 min of ischaemia Limitations: all male, no control group, subjects had advanced HF of various aetiologies; shorter occlusion time to induce ischaemia; smoking status unknown; unclear if different aspects of data analysis were blinded |

Ultrasound: Brachial artery |

Muscle strength and endothelium-dependent vasodilation at baseline did not significantly change post exercise Pre exercise baseline hyperaemic responses increased at 10 s and then decreased; overall decrease in diameter of 0.13 ± 0.04 mm at 1 min after cuff release. Post-exercise flow-mediated vasodilation diameter increased (1.01% ± 0.99%) at 1 min after cuff release |

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; AIT, aerobic interval training; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ASA, aspirin; CRT, cardiac resynchronisation therapy; ICD, internal cardiodefibrillator; CM, cardiomyopathy; IHD, ischaemic heart diseases; EF, ejection fraction; ET-1, endothelin-1; NS, non-significant; NO, nitric oxide; ACH, acetylcholine; NTG, nitroglycerine; HF, heart failure; HR, heart rate; HTN, hypertension; IL-6, interleukin-6; CAD, coronary artery disease; MAP, mean arterial pressure; MCT, moderate continuous training; NE, norepinephrine; SNP, sodium nitroprusside; y, year.

NYHA IIIb recent history of dyspnoea.

Reported as SEM.

Types of Study Design

Among the selected studies, there were seven randomised control trials, 2- two-group experimental studies, one single-group experimental study, and one crossover study. In addition to FMD, the majority of investigators (n = 8) also examined multiple outcomes (e.g., quality of life, maximal oxygen consumption), however only findings related to the effects of exercise on FMD are reported herein.

Quality of Studies

The assessment of the methodological quality of the study is dependent upon the extent that the authors provide information about the design and analysis of the study. None of the randomised studies reported using intention to treat analysis; often missing data and attrition were not addressed. All investigators reported the standard deviation or standard error of the point estimates for various outcome variables related to vasoreactivity but statistical values (e.g., F score) and confidence intervals were not always included. Therefore considering the heterogeneity of the data, we did not perform a meta-analysis. The assessment of study quality is summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of Individual Components Related to the Quality of the Studies.

| Study | Eligibility Criteria Specified |

Random Allocation | Concealed Allocation |

Baseline Comparability |

Blinded Assessors |

Missing Data | Between-Group Comparisons |

Point Estimates and Variability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomised controlled trials | ||||||||

| Maiorana et al. [14] | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | +SE |

| Linke et al. [15] | − | + | − | + | − | − | + | +SEM |

| Kobayashiet al. [16] | − | + | − | + | + | − | + | +SE |

| Belardinelli et al. [17] | − | + | − | + | − | − | + | +SD |

| Parnell et al. [18] | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | +SEM |

| Belardinelli et al. [19] | − | + | − | + | + | − | + | +SD |

| Wisløff et al. [21] | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | +SD |

| Erbs et al. [22] | − | + | − | + | + | − | + | +SD |

| One and two group experimental design | ||||||||

| Bank et al. [13] | − | N/A | N/A | + | + | − | + | +SE |

| Miche et al. [20] | − | N/A | N/A | + | − | − | + | +SD |

| Dean et al. [23] a | − | N/A | N/A | N/A | − | − | N/A | +SEM |

SD, standard deviation; SE, standard error; SEM, standard error of mean.

One group experimental design.

Controlling Confounding Variables

There are several confounding variables, such as medication and smoking, as well as co-morbid conditions that may influence vasoreactivity. Study protocols differed with respect to administering/withholding medications and including/excluding active smokers. Medications were continued but withheld for 24 h prior to the vascular measures [13,15,22]; continued at the same dose throughout the duration of the study (not withheld) [14,17–19,21,23]; or allowed to change as needed during the study period [16,20]. The majority of studies excluded active smokers [13–16,22], whereas other studies did not address smoking status [18–21,23]. Belardinelli [17] enrolled smokers in both the control (n = 9) and the exercise (n = 10) groups. In addition, most of the investigators included subjects with co-morbidities; however investigators controlled for confounding co-morbidities in a number of ways. Some investigators excluded potential subjects with hypertension [17,18,22], valvular disease [17,22] or unstable angina [17,21,22]. Others [14,15] set specific parameters such as blood pressure readings >160/90 mmHg or total cholesterol level >6 mmol L as exclusion criteria. Belardinelli [17] compared the incidence of several co-morbidities between the exercise and control groups at baseline while Kobayashi [16] only reported the between group incidence of atrial fibrillation. Two studies did not address co-morbidities [19,23]. It should be noted that changes in endothelial function were found in these studies in spite of any possible effects of exercise on any individual comorbidities associated with HF.

Exercise Training Protocols

Exercise protocols varied across the studies, with cycle ergometry as the most common form of aerobic exercise (Table 3). Exercise intensity (determined by baseline stress testing) ranged from 50% to 95% of peak heart rate [18,21]. Two studies used a four-week handgrip resistance training program at varying intensities [13,23]. Others used combined training modes, such as Maiorana et al., who used resistance training (circuit) with aerobic training (cycling and treadmill walking) for eight weeks at an intensity of 70–85% of peak HR [14]. Dean et al. combined free-weights with handgrip training [23]. The frequency of exercise training varied from short intervals such as cycling for 10 min six times per day [15] to hour long sessions five to seven times/week [18]. The most common frequency of exercise was three times/week. Duration of training ranged from four weeks [13,15,20,23] to 12 weeks [16,21,22]. Across all studies, the initial exercise sessions were supervised.

Table 3.

Summary of Exercise Protocols.

| Study | Type of Exercise | Duration of Training |

Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bank et al. [13] | Resistance (handgrip) Non-dominant forearm 4 times/wk |

4 wks | 30% of maximal hand grip strength at 30 grips per min |

| Maiorana et al. [14] | Combination training (resistance circuits, cycling) 7 resistance circuits (upper and lower limbs) alternating with 8 aerobic (cycling) stations each performed for 45 s, then 5 min of treadmill walking; 8 wks of three 1-h training sessions |

8 wks | Aerobic: 70–85% of peak HR; resistance: maintained at 55–65% of pre-training MVC |

| Linke et al. [15] | Aerobic (cycling) 6 times per day for 10 min |

4 wks | 70% peak oxygen consumption at ventilatory threshold |

| Kobayashi et al. [16] | Aerobic (computerised cycling) 2–3 days/wk in two 15-min sessions per day for 3 months |

12 wks | Maintain HR to the ventilatory threshold for 15 min each session; if HR irregular exercise speed at 13 on Borg scale |

| Belardinelli et al. [17] | Aerobic (cycling) 3 times/wk for 1 h (15 min stretching, 40 min of cycling) |

8 wks | 60% of peak VO2 |

| Parnell et al. [18] | Combination training (walking, weights, cycling) Walking, light hand weights, cycling 3 times/wk supplemented with home-based exercises to increase duration from three 30-min/wk to 60-min per day for 5–7 days/wk |

8 wks | 50–60% pre-determined maximal HR |

| Belardinelli et al. [19] | Aerobic (cycling) 3 times/wk for 1 h (15 min stretching, 40 min of cycling) |

8 wks | 60% of peak VO2 |

| Miche et al. [20] | Combination (cycling and weights) Aerobic (cycling) 3 times/wk and muscle strength training 2 times/wk |

4 wks | 60–80% peak VO2 |

| Wisløff et al. [21] | Aerobic (uphill walking) 2 times a week and 1 weekly session at home AIT: 10-min warm-up at 50–60% peak HR; walked at 4 min intervals at 90–95% of peak HR; each interval separated by 3 min of walking at 50–70% of peak HR MCT: walked continuously at 70–75% of peak HR for 47 min; incline adjusted to maintain target HR |

12 wks | Aerobic interval: 90–95% of peak HR Moderate continuous: 70–75% of peak HR Serum lactate levels ensured different intensities of exercise were achieved |

| Erbs et al. [22] | Aerobic (cycling) 3 wks: 3–6 times per day for 5–20 min 12 wks: 20–30 min per day |

12 wks | HR reached at 50% of VO2 max for 3 wks Then HR reached at 60% of VO2 max at home |

| Dean et al. [23] | Resistance (handgrip, free weights) 1 set of 6–10 repetitions at 60% for 2 days progressing to 6 sets of 6–10 repetitions at 70% to 80% of MVC |

4 wks | 60% of MVC set using hand grip dynamometer Weight determined by whatever the patient could lift comfortably |

wks, weeks; min, minute; h, hour; HR, heart rate; s, seconds; AIT, aerobic interval training; MCT, moderate continuous training; MVC, maximal voluntary contraction; VO2, peak oxygen consumption.

Notably, one randomised study was designed to determine if aerobic interval training was more effective than moderate continuous training to reverse peripheral vessel remodelling [21]. Wisløff et al. [21] randomised subjects with a reduced EF (<40%) who were prescribed beta blockers following a myocardial infarction into aerobic interval or moderate continuous training groups. Both groups showed improved FMD diameters; however, the improvement in the aerobic group was significantly greater (Table 1).

In addition to supervising subjects at the onset of training, several investigators monitored subject performance using self-report, serum lactate levels, or computers connected to the cycle ergometer to determine continued adherence to the exercise protocols. Investigators commonly reported that the exercise groups received education/instruction about exercise training, but the instructor (physical therapist, nurse, exercise physiologist), format and length of instruction, and delivery method (individual vs. group setting) pertaining to the education/instruction were not discussed. These are important factors that may potentially influence the subjects’ ability to follow and comprehend the protocol. In general, follow-up did not extend beyond completion of the exercise training period. An exception was the study by Belardinelli [19], in which follow-up continued after completion of exercise training for an additional 24 ± 6 months or until a cardiac event occurred.

Vasoreactivity Methods

Imaging with high-resolution ultrasound and plethysmography (Table 1) were used to directly assess vasoreactivity (i.e., endothelium-dependent and endothelium-independent vasodilation in the peripheral circulation). All studies measured vasoreactivity at two time points: baseline (pre-exercise) and upon completion of the training period (post-exercise). The most common method to measure vasoreactivity was ultrasound using the brachial or radial artery [15–17,19–23]. Three studies measured vasoreactivity using plethysmography in the forearm [13,18] or radial artery [14]. The exercise study protocols with regards to exercise frequency and type, duration, and intensity are summarised in Table 3.

Vascular Effects of Exercise Training

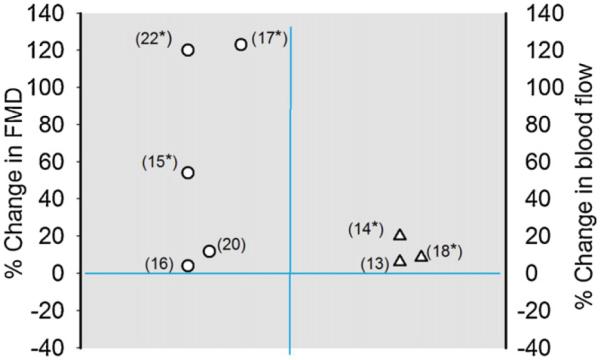

Collectively, results from the studies indicate significant improvement in endothelium-dependent vasodilation after aerobic, resistance, or combination exercise training [14–19,21–23], with the exception of two studies [13,20] (Table 1 and Fig. 2). Miche et al. [20] examined the effect of a four week combined exercise training program (i.e., ergometric strength and walking exercises) in HF subjects with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) and found no statistically significant training effect on endothelial function in either DM HFrEF group (Table 1). Likewise, Bank et al. [13] found non-significant improvement in endothelial function following four weeks of handgrip exercises in subjects with HF, although the healthy control subjects in this study showed significant improvement in endothelium-dependent function [13].

Figure 2.

Graphical plot of representation of Table 1 study data. Values (symbols) are percent change (pre-exercise values – post exercise values/baseline values) and were calculated using data values reported for each of the studies summarised in Table 1, with the exception of Belardinelli et al. [19], Wisløff et al. [21] and Dean et al. [23] studies. The results from the former studies were not included since data was reported in figures. Also the percent change value for the Kobayashi et al. study reflects those found using the tibial artery. Numbers in parentheses designate study reference number and *changes were significant.

Endothelium-independent vasodilation, as determined by the response of the vascular smooth muscle to a direct vasodilator stimulus (nitroglycerine or nitroprusside), was measured in nine of the studies (Table 1). Of these, the findings from seven studies did not show a significant change in endothelium-independent vasodilation. However, two studies [17,18] which used plethysmography to measure the response to nitroprusside (SNP) after eight weeks of training demonstrated improved endothelium-independent vasodilation after exercise. Maiorana et al. [14] showed statistically significant within-group differences analysing data using absolute blood flows and change ratio of blood flow (expressed as percent change in blood flow of the arm infused with medication compared with the control arm), while Parnell [18] reported a significant within-group difference in forearm blood flow with escalating doses of SNP (AUC, p = 0.006) following exercise training.

Discussion

Taken together, the findings of this review indicate that several types of exercise training (aerobic, resistance, and combined) of variable duration (4–16 weeks) improved endothelium-dependent vasodilation. Furthermore, this finding was not age-dependent, NYHA class or HF aetiology dependent (Table 1). Our findings are consistent with other studies and reviews, which reported that exercise training improved endothelium-dependent function in patients with HFrEF [5–9].

Most studies reported herein did not find exercise training effects on endothelium-independent vasodilation except for two reports that utilised combined aerobic with resistance training for eight weeks [14,18]. It is possible that the duration of training and combination of strength and aerobic exercise may have altered endothelium-independent vasodilation. For example, there were three other studies that employed 12 weeks of aerobic training with no changes in endothelium-independent dilation [15,21,22]. In another study that combined aerobic (cycling) and strength training for four weeks there was no change in endothelium-independent vasodilation. Therefore, the mechanisms of the effects of exercise training on endothelium-independent function will require further exploration. Studies designed to assess FMD on a weekly basis during the exercise training period or hourly following acute exercise may help to understand these mechanisms. Additional reasons for the lack of improvement in endothelium-independent vasodilation may be inadequate delivery of blood to exercising skeletal muscle and reduced muscle sensitivity to nitric oxide [26]. The first point has been widely addressed in the literature [4,25]. Regarding the latter, investigators have suggested that the response of vascular smooth muscle in individuals who regularly take nitrate-based medications may attenuate to NO-mediated and cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) stimuli [27]. Five of the studies reviewed included HF patients receiving nitrates [14,17,20,21,23]. And one of the latter studies as noted above found significant improvements in endothelium-independent vasodilation [14]. Based on the results from this review, it is not clear that the response of vascular smooth muscle is affected by nitrate medications or that exercise training can improve this response. Nitrate use may need to be a consideration when using endothelium-independent vasodilation as an outcome variable. Finally, it is thought that the loss of endothelium-dependent vasodilation occurs early in the development of cardiovascular disease, but it is not clear if and when endothelium-independent vasodilation is reduced [24,25].

Overall, the common limitations of the studies included in this review were small sample sizes that limit the ability to control for all the co-morbidities that might confound the results. Other limitations included: (1) a small number of women and lack of ethnic minorities in the population of study, (2) short duration of exercise programs, (3) inability to extrapolate supervised training at a rehabilitation facility to activity at home, (4) lack of a quantification of exercise intensity in the home-based interventions. However, given the complexity of exercise studies, longitudinal follow-up and patient population, HFrEF, it is not unexpected that sample sizes were small. In this review, most studies [16,17,19,22,23] were published after 2002 and utilised ultrasound imaging guidelines/techniques published by Corretti and colleagues [28]. Use of FMD measurement guidelines [28] reduces the likelihood of variability and inconsistencies in the technical aspects of FMD measurement. Corretti et al. [11,28–30] recommend standardised schema for collecting and reporting FMD data, which allows for aggregating and comparing different published data, determining effect size and performing meta-analysis.

Although our review was focused on evaluating the influence of exercise on endothelial function, many of the studies reviewed herein also considered the effects of exercise training on patient safety, as well as potential issues related to exercise adherence. Ventricular arrhythmias, common in this patient population, were reported in one study [19], and the arrhythmias occurred only in the untrained control group (53%; n = 15) during the follow-up period. Among the studies, one death from cardiovascular causes occurred in a control group [22] and one in an exercise group [21]. These findings support those from HF-ACTION [31], which found that aerobic exercise was safe and improved exercise capacity even in patients with NYHA IV disease or following device implantation. However, findings from HF-ACTION also indicated that adherence to exercise over the three-year study period decreased over time. In this review, in studies that reported attrition, there were no differences in between control and exercise groups during the training period (4–12 weeks). Monitoring adherence to exercise programs/interventions is a critical aspect to both short- and long-term exercise studies, but clearly more challenging in long-term and unsupervised exercise trials. Future studies may need to test the added benefit of different types of motivational (group vs. individual exercise sessions) and lifestyle adherence strategies [32–34].

As noted above, different types of exercise training (aerobic, resistance, and combined) had a positive effect on endothelial function. However, different types of exercise and protocols were used making it difficult to recommend the optimal exercise protocol for patients with HFrEF (NYHA I-III). Also, these results need to be interpreted in view of the limitations (small, predominantly male samples) and study characteristics (designed to examine special populations such as erectile dysfunction, advanced disease, and device therapy), which restrict generalisability. Therefore, it remains unclear as to which type of aerobic training (cycling vs. walking) is associated with the best effects on endothelial function. It is also remains unknown if combinations of programs involving walking or cycling plus resistance exercise are more effective than aerobic exercise alone on endothelial function because many of the studies included in this review did not compare exercise modes (Tables 1 and 3).

Recently, Anagnostakou et al. [35] examined the effects of combined interval and strength training (54 ± 10 years; n = 14) compared with interval training alone (52 ± 11 years; n = 14) on FMD in a predominantly male sample (82%; n = 23) with HF (EF < 45%) in a 12-week protocol. The investigators found significant increases in brachial artery diameter analysed as absolute change (difference in artery diameter before and after occlusion) and relative change (percentage of relative change in artery diameter before and after occlusion) between groups (p = 0.02; p = 0.03 respectively) and concluded that combined training had a greater effect on vasoreactivity than interval training alone. The authors acknowledge several limitations to the study, including that the EF was >50% in four subjects. Thus, this study did not meet the inclusion criteria for this review but is important because it compares the effectiveness of two types of exercise.

Conclusion

The findings of this review indicate that different types of exercise training (aerobic, resistance, and combined) of variable duration (4–16 weeks) in HFrEF improved endothelium-dependent vasodilation. However, few studies reported positive exercise effects on endothelium-independent vasodilation. The latter is difficult to explain. The optimal training intensity and duration, and the added value of resistance exercise along with aerobic training, remain to be determined in patients with HFrEF. Optimizing exercise training is a complex issue since HF is a heterogeneous syndrome. Patients often have co-morbidities which may affect the peripheral vasculature and in turn, exercise capacity. Also findings from studies with HFrEF patients cannot be extrapolated to all patients with HF such as those with preserved ejection fraction HF. The contribution of endothelial dysfunction to the abnormalities in the peripheral circulation of HF is well established. In this context, measurement of endothelial function remains important and should be used as an endpoint or variable in clinical trials and investigations.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Midwest Roybal Center which is supported by a center grant from the National Institute on Aging/NIH (PI: Susan L. Hughes, DSW; Grant 5P30AG022849-07; UIC PAF # 2009-02182; Parent Protocol for the center grant – UIC Protocol #2009-0668). The authors thank Kevin Grandfield, Publication Manager for the UIC Department of Biobehavioral Health Science, for editing assistance.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest None.

Support: Dr. Phillips is supported by National Institutes of Health (Grant # HL85614).

References

- [1].Katz SD, Hryniewicz K, Hriljac I, Balidemaj K, Dimayuga C, Hudaihed A, et al. Vascular endothelial dysfunction and mortality risk of patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2005;111(3):310–4. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000153349.77489.CF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Fisher D, Rossa S, Landmesser U, Spiekermann S, Engberding N, Honig B, et al. Endothelial dysfunction in patients with chronic heart failure is independently associated with increased incidence of hospitalization, cardiac transplantation or death. Eur Heart J. 2005;26(1):65–9. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].de Berrazueta JR, Guerra-Ruiz A, Garcia-Unzueta MT, Toca GM, Laso SL, de Adana MS, et al. Endothelial dysfunction measured by reactive hyperaemia using strain-gauge plethysmography, is an independent predictor of adverse outcome in heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2010;12(5):477–83. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Downing J, Balady GJ. The role of exercise training in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(6):561–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Keteyian SJ. Exercise training in congestive heart failure: risks and benefits. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2011;53(6):419–28. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Piepoli MF, Davos C, Francis DP, Coats AJ. [accessed 30.09.08];Exercise training meta-analysis of trials in patients with chronic heart failure (ExTraMATCH) BMJ. 2004 328(7433) doi: 10.1136/bmj.37938.645220.EE. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.37938.645220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Rees K, Taylor RS, Singh S, Coats AJ, Ebrahim S. [accessed 30.09.08];Exercise based rehabilitation for heart failure. Cochrane Database of Sys Rev. 2004 (3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003331.pub2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003331.pub2. Art. No.: CD00331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [8].McKelvie RS, Teo KK, McCartney N, Humen D, Montague T, Yusuf S. Effects of exercise training in patients with congestive heart failure: a critical review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25(3):789–96. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00428-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Haykowski MJ, Liang Y, Pechter D, Jones LW, McAlister FS, Clark AM. A meta-analysis of the effect of exercise training on heart failure: the benefit depends on the type of training performed. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(24):2329–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Tai MK, Meiniger JC, Frazier LQ. A systematic review of exercise Interventions in Patients with Heart Failure. Biol Res Nurs. 2008;10(2):156–82. doi: 10.1177/1099800408323217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Thijssen DHJ, Black MA, Pyke KA, Padilla J, Atkinson G, Harris RA, et al. Assessment of flow-mediated dilation in humans: a methodological and physiological guideline. Am J Physiol Heart Circ. 2011;300(1):H2–12. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00471.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gielen S, Schuler G, Adams V. Cardiovascular effects of exercise training. Circulation. 2010;122(12):1221–38. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.939959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bank AJ, Shammus RA, Mullen K, Chuang PP. Effects of short-term forearm exercise training on resistance vessel endothelial function in normal subjects and patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 1998;4(3):193–201. doi: 10.1016/s1071-9164(98)80006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Maiorana A, O’Driscoll G, Dembo L, Cheetham C, Good-man C, Taylor R, et al. Effect of aerobic and resistance training on vascular function in heart failure. Am J Physiol. 2000;279(4):1999–2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.4.H1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Linke A, Schoene N, Gielen S, Hofer J, Erbs S, Schuler G, et al. Endothelial dysfunction in patients with chronic heart failure: systemic effects of lower-limb exercise training. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;379(2):392–7. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)01108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kobayashi N, Tsuruya Y, Iwasawa T, Ikeda N, Hasimoto S, Yasu T, et al. Exercise training in patients with chronic heart failure improves endothelial function predominantly in the trained extremities. Circulation J. 2003;67(6):505–10. doi: 10.1253/circj.67.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Belardinelli R, Lacalaprice F, Faccenda E, Purcaro A, Perna G. Effects of short-term moderate exercise training on sexual function in male patients with chronic stable heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2005;101(1):83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Parnell MM, Holst DP, Kaye DM. Augmentation of endothelial function following training is associated with increased L-arginine transport in human heart failure. Clin Sci. 2005;109(6):523–30. doi: 10.1042/CS20050171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Belardinelli R, Capestro F, Misiani A, Scipione P, Georgiou D. Moderate exercise training improves functional capacity, quality of life, and endothelium-dependent vasodilation in chronic heart failure patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators and cardiac resynchronization therapy. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev and Rehabil. 2006;13(5):818–25. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000230104.93771.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Miche E, Hermann G, Norwak M, Witrz U, Tietz M, Hurst M, et al. Effect of exercise training program on endothelial dysfunction in diabetic and non-diabetic patients with severe chronic heart failure. Clin Res Cardiol. 2006;95(Suppl. 1):l117–24. doi: 10.1007/s00392-006-1106-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wisløff U, Støylen A, Loennechen JP, Bruvold M, Rogmo O, Haram PM, et al. Superior cardiovascular effect of aerobic interval training versus ultrasound moderate continuous ultrasound training in heart failure patients: a randomized study. Circulation. 2007;115(24):3086–94. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.675041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Erbs S, Hollriegel R, Linke A, Beck EB, Adams V, Gielen S, et al. Exercise training in patients with advanced chronic heart failure (NYHA IIIb) promotes restoration of peripheral vasomotor function, induction of endogenous regeneration, and improvement of left ventricular function. Cir Heart Fail. 2010;3(4):486–94. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.868992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Dean AS, Libonati JR, Madonna D, Ratcliffe SJ, Marguiles KB. Resistance training improves in end-stage heart failure patients on inotropic support. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2011;26(3):218–23. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e3181f29a46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Gori T, Dragoni S, Di Stolfo G, Sicuro S, Liuni A, Luca MC, et al. Tolerance to nitroglycerin-induced preconditioning of the endothelium: a human in vivo study. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298(2):340–5. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01324.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Keteyian SJ, Fleg JL, Brawnwe CA, Pina IL. Role and benefit of exercise in the management of patients with heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s10741-009-9157-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10741-009-9157-7. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Middlekauf HR. Making the case for skeletal myopathy as the major limitation of exercise capacity in heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2010;3:537–46. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.903773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Parker JD. Nitrate tolerance, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial function: another worrisome chapter on the effects of organic nitrates. J Clin Invest. 2004;11(3):352–4. doi: 10.1172/JCI21003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Corretti M, Anderson T, Benjamin E, Celermajer D, Charbonneau F, Creager MA. Guidelines for the ultrasound assessment of endothelial-dependent flow-mediated vasodilation of the brachial artery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39(6):257–65. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01746-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Perez A, Leotta DF, Sullivan JH, Trenga CA, Sands FN, Aulet MR, et al. Flow mediated dilation of the brachial artery: an investigation of methods requiring standardization. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2007;7(11):1–8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-7-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Harris RA, Nishiyama SK, Wray DW, Richardson RS. Ultrasound assessment of flow-mediated dilation. Hypertension. 2010;55(4):1075–85. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.150821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].O’Connor CM, Whellan DJ, Lee KL, Keteyian SJ, Cooper LS, Ellis SJ. Efficacy and safety of exercise training in patients with chronic heart failure: HF-ACTION randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301(14):1439–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Nilsson BB, Hellesnes B, Westheim A, Risberg MA. Group-based aerobic interval training in patients with chronic heart failure: Norwegian Ullevaal Model. Phys Ther. 2008;88(4):523–35. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20060374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Prescott E, Haardem-Hansen R, Delad F, Ørkilda B, Teisnera AS, Nielsena H. Effects of a 14-month low-cost maintenance training program in patients with chronic systolic heart failure: a randomized study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2009;16(4):430–7. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e32831e94f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Pina IL, Oghlakian G, Boxer R. Behavorial intervention, nutrition, and exercise trials in heart failure. Heart Fail Clin. 2011;7(4):467–79. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Anagnostakou V, Chatzimichail K, Dimopoulos S, Karatzanos E, Papazachou O, Tasoulis A. Effects of interval cycle training with or without strength training on vascular reactivity in heart failure patients. J Card Fail. 2001;17(7):585–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]