Abstract

Untreated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) co-existing with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), also known as overlap syndrome, has higher cardiovascular mortality than COPD alone but its underlying mechanism remains unclear. We hypothesize that the presence of overlap syndrome is associated with more extensive right ventricular (RV) remodeling compared to patients with COPD alone. Adult COPD patients (GOLD stage 2 or higher) with at least 10 pack-years of smoking history were included. Overnight laboratory-based polysomnography was performed to test for OSA. Subjects with an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) >10/h were classified as having overlap syndrome (n = 7), else classified as having COPD-only (n = 11). A cardiac MRI was performed to assess right and left cardiac chambers sizes, ventricular masses, and cine function. RV mass index (RVMI) was markedly higher in the overlap group than the COPD-only group (19 ± 6 versus 11 ± 6; p = 0.02). Overlap syndrome subjects had a reduced RV remodeling index (defined as the ratio between RVMI and RV end-diastolic volume index) compared to the COPD-only group (0.27 ± 0.06 versus 0.18 ± 0.08; p = 0.02). In the overlap syndrome subjects, the extent of RV remodeling was associated with severity of oxygen desaturation (R2 = 0.65, p = 0.03). Our pilot results suggest that untreated overlap syndrome may cause more extensive RV remodeling than COPD alone.

Keywords: Sleep disordered breathing, Overlap syndrome, Cardiac MRI, Lung

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) are both common diseases affecting 10–20% and 5% respectively of the adult U.S. population over 40 years of age (1, 2). Their coexistence in the same patient was termed ‘overlap syndrome’ in 1985 by Flenley and may affect 1% of the U.S. population (3).

Untreated overlap syndrome has important clinical consequences. Flenley described that patients with overlap syndrome are more hypoxemic than either condition alone (3). Non-randomized studies have shown that untreated overlap syndrome patients also have higher mortality and more COPD-exacerbation related hospitalizations compared to patients with COPD alone (4, 5). The main reason for higher mortality in untreated overlap syndrome patients is cardiovascular, the exact mechanisms of which are unclear (4, 5). However, some evidence suggests pulmonary hypertension resulting in right heart dysfunction may play a critical role. First, the prevalence of pulmonary hypertension in the overlap syndrome is much higher than OSA alone (6, 7).

Second, overlap patients develop hypercapnia and pulmonary hypertension at less severe levels of pulmonary dysfunction than COPD alone (6). Finally, pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular (RV) dysfunction have been well described in OSA (8, 9). Thus, although RV volumes and function can be abnormal in either disease, it may be worse in overlap syndrome due to increased hypoxemia and/or hypercapnia, particularly during sleep.

Compared to standard, 2–dimensional echocardiography, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the gold standard for assessment of the RV (10). This may be particularly relevant in patients with emphysema, where echocardiography has a low sensitivity (60%), specificity (74%), positive predictive value (68%) and negative predictive value (67%) for estimating PA pressure compared with RV catheterization (11). Obesity can also complicate the acquisition of adequate echocardiography windows, supporting the benefits of cross-sectional imaging in obese people with OSA and/or COPD. Cardiac MRI may even have greater predictive power than cardiac catheterization results to measure changes in RV volumes and function, because cardiac catheterization does not usually assess RV function and volumes (12, 13). To date, most studies have used two-dimensional echocardiography to study pulmonary hypertension and RV function in overlap syndrome patients.

To our knowledge, no study has reported the use of cardiac MRI to assess RV volumes, function and remodeling in overlap syndrome patients. We therefore aimed to assess the usefulness of cardiac MRI in detecting adverse RV remodeling in patients with overlap syndrome, hypothesizing that patients with overlap syndrome would have more extensive adverse RV remodeling compared to subjects with COPD alone.

Methods

Patients

This study was completed over a period of 6 months from January to June, 2011, at Brigham and Women's Hospital. Adult patients (≥18 years of age) with known COPD as diagnosed by a pulmonologist (defined as Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease, GOLD stage 2 or higher and ≥10 pack-years of smoking history) were screened (14). Patients with standard contraindications to cardiac MRI, receiving positive airway pressure therapy, uncontrolled COPD, known cardiovascular disease, or pregnant women were excluded. The study was approved by the Partners Human Research Committee institutional review board (2010P001753), and all participants gave their written informed consent.

Protocol

After a telephone screening, patients presented for a history and physical examination, pulmonary function tests, overnight polysomnography and cardiac MRI the next morning. Pulmonary function tests, including lung volumes and diffusing capacity, were performed according to the guidelines of the American Thoracic Society (15). All subjects underwent attended in-laboratory polysomnography, which were scored by an experienced, blinded sleep technologist according to standard criteria (16).

Patients with an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) ≥10/hour were a priori included in the overlap syndrome group while remaining subjects were included in the COPD-only control group. All study participants completed the Epworth Sleepiness Scale to assess daytime sleepiness (17) and the Modified Medical Research Council (MMRC) score to assess dyspnea before the polysomnography (17).

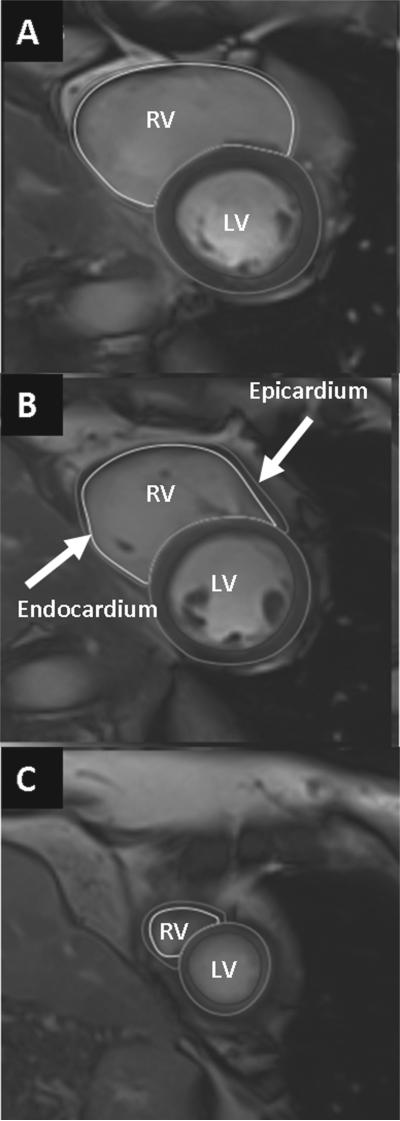

Cardiac MRI

All cardiac MRI images were acquired with ECG gating, breath-holding, and with the patient in a supine position. Subjects were imaged on a 3.0-T cardiac MRI system (Tim Trio, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). The cardiac MRI protocol consisted of cine steady-state free precession (SSFP) imaging for RV size and function. A stack of short axis cine images was obtained from base to apex of the RV and the LV. From these SAX images, the time frames corresponding to end-diastole and end-systole were identified, and thereafter the RV and LV endocardial borders were identified. Full visualization of the correct placement of RV contours relied on evaluation of cine images and the corresponding apical 4-chamber images to determine the demarcation between the right atrium and the RV. For the LV and RV mass calculation, the papillary muscles were excluded (18). An example of RV contouring is shown in Figure 1, which includes basal, mid, and apical RV images in systole and diastole. RV and LV end-diastolic volume (EDV) and myocardial volume were calculated using the summation of disks method (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cardiac MRI images showing manually traced right and left ventricular endocardial (inner) and epicardial (outer) borders at end systole and end diastole. LV: left ventricular; RV: right ventricular.

RV and LV mass were calculated by multiplying myocardial density (1.05 g/cm3) by the calculated volume of myocardium. Atrial systolic and diastolic volumes were measured using the biplane method with 2-chamber and 4-chamber cine images. Flow imaging was performed perpendicular to the main pulmonary artery with a velocity-encoded gradient echo sequence, from the pulmonary artery flow profile, the peak and mean pulmonary artery velocity were calculated. Cardiac MRI data were analyzed with specialized software (Medis®, Leiden, The Netherlands) by researchers blinded to non-cardiac MRI clinical data.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics are presented as mean ± standard deviations for continuous variables and as numbers and percentages for categorical variables. Data were assessed for normality of distribution and homogeneity of variance. Continuous variables were analyzed using Student's t-tests or Mann–Whitney tests, and categorical variables were analyzed using Fisher's exact test. The relationships between two different parameters were evaluated by simple correlation analysis. Two sided p-values of ≤0.05 were considered significant. All analyses were performed using Sigmaplot software, version 11.0 (Systat Software, Inc.; Chicago, IL).

Results

Study population

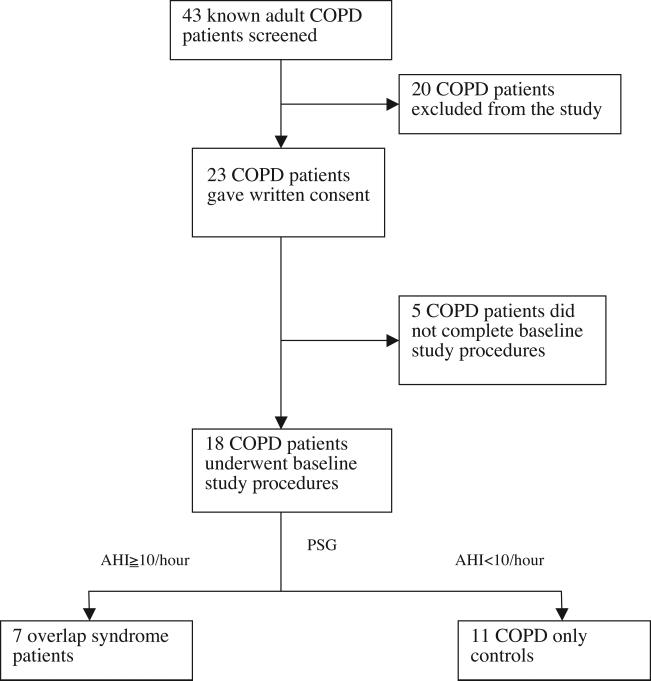

A diagram describing patient inclusion is shown in Figure 2. Forty-three subjects with known COPD were screened; 20 subjects did not meet inclusion criteria (4 subjects had known OSA and were already using continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) treatment, 5 subjects had clinically unstable COPD, 5 subjects were excluded by spirometry, and six subjects had contraindications to MRI). A further 5 subjects voluntarily withdrew before completion of the protocol. Of the final sample of 18 subjects, 7 were found to have OSA and were therefore considered the overlap group, and the remaining 11 subjects who had normal polysomnography evaluations were included as COPD controls.

Figure 2.

Patient inclusion diagram. AHI: apnea-hypopnea index; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PSG: polysomnography.

Study subject characteristics

The characteristics of study subjects are shown in Table 1. Patients with overlap syndrome had a higher resting heart rate and similar systolic and diastolic blood pressures. All COPD patients had daytime normoxemia. No COPD subject had hypercapnia (defined as end-tidal PCO2 ≥45 mmHg) suggestive of hypoventilation during polysomnography. The total apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) (p < 0.001) and oxygen desaturation index (ODI) (p = 0.02) were higher in the overlap group compared to the COPD-only group. The 6-minute walk distance was lower in the overlap group compared to the COPD group (p = 0.02). There was no significant difference in age, body mass index (BMI), duration of COPD, smoking history, degree of airway obstruction (as measured by FEV%) or degree of hyperinflation (as measured between RV/TLC%) between overlap syndrome and COPD-only subjects.

Table 1.

Study subject characteristics.

| Variable | Overlap syndrome (n = 7) | COPD-only (n = 11) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 60 ± 9 | 62 ± 9 | 0.7 |

| Female gender, n (%) | 3 (43%) | 6 (55%) | 0.4 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30 ± 9 | 26 ± 4 | 0.2 |

| Heart rate (beats/minute) | 76 ± 10 | 64 ± 9 | 0.02 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 128 ± 13 | 126 ± 8 | 0.71 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 77 ± 8 | 73 ± 7 | 0.21 |

| Duration of COPD, years | 8 ± 2 | 10 ± 3 | 0.8 |

| Duration of smoking, pack-years | 27 ± 15 | 52 ± 24 | 0.1 |

| MMRC Score | 2.1 ± 1.1 | 1.4 ± 0.9 | 0.2 |

| Six-Minute walk distance, m | 285 ± 29 | 324 ± 35 | 0.02 |

| FEV1, % | 61 ± 10 | 67 ± 19 | 0.4 |

| RV/TLC, % | 125 ± 33 | 118 ± 32 | 0.6 |

| Total AHI (events/h) | 27.5 ± 14.8 | 4.3 ± 2.9 | <0.001 |

| ODI (events/h) | 35.3 ± 19.2 | 10.4 ± 4.4 | 0.02 |

Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, unless otherwise specified.

AHI: apnea-hypopnea index; BMI: body mass index; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 second; MMRC: modified medical research council; ODI = oxygen desaturation index; RV: residual volume; TLC: total lung capacity.

Cardiac MRI results

Right atrium and ventricular results

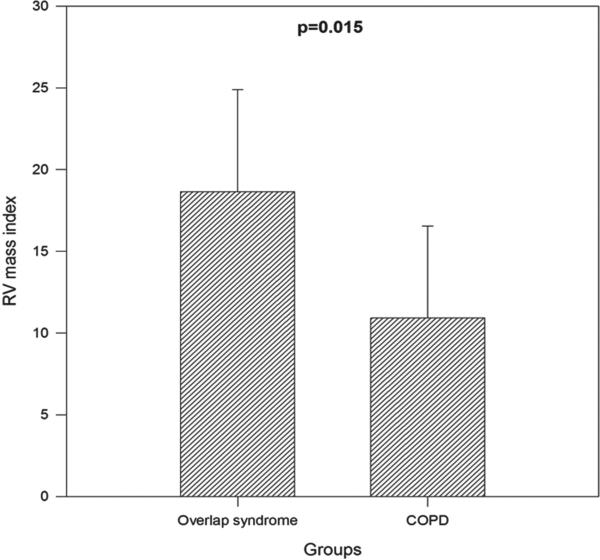

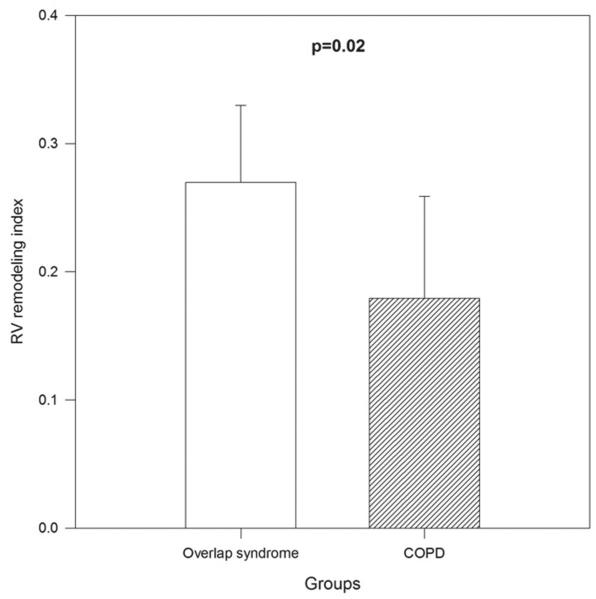

RV mass index (RVMI) was higher in the overlap group than the COPD-only group (19 ± 6 g/m2 vs. 11 ± 6 g/m2, p = 0.02, Figure 3). The RV remodeling index (RVRI), defined as the ratio between RVMI and RV end-diastolic volume index (RVEDVI), was higher in the overlap syndrome group than the COPD-only group (0.27 ± 0.06 vs. 0.18 ± 0.08, p = 0.02, Figure 4). There was no significant difference in the RA area index, RVEDVI, RV end-systolic volume index or RVEF between the overlap syndrome and COPD-only groups. All indices were calculated by dividing the value by body surface area.

Figure 3.

Comparison of right ventricular mass index between untreated overlap syndrome and COPD-only subjects (p = 0.02).

Figure 4.

Comparison of right ventricular (RV) remodeling index (ratio of RV mass index to RV end-diastolic volume index) between untreated overlap syndrome and COPD-only subjects (p = 0.02).

Left atrium and ventricular results

There were no significant differences in the left atrial or left ventricular parameters (LA volume index, LVEDV, LVESV, LVMI, LV remodeling index, LVEF) between the overlap and COPD-only groups.

PA and aortic root size results

PA and aortic size indices were defined as the diameter of the vessel divided by body surface area. There was no significant difference in the main PA size index and the peak and mean PA velocity. There was a trend toward and an increase in the RV stroke volume and cardiac output in patients with overlap syndrome as compared to patients with COPD-only (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of cardiac MRI results between overlap syndrome and COPD groups.

| Variable | Overlap syndrome (n = 7) | COPD-only (n = 11) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| RA atrial area index, cm2/m2 | 8.5 ± 2.1 | 7.9 ± 1.8 | 0.5 |

| RV end-diastolic volume index, ml/m2 | 68 ± 10 | 65 ± 13 | 0.7 |

| RV end-systolic volume index, ml/m2 | 28 ± 4 | 31 ± 9 | 0.4 |

| RV ejection fraction, percent | 51 ± 4 | 51 ± 7 | 0.5 |

| RV mass index, g/m2 | 19 ± 6 | 11 ± 6 | 0.02 |

| RV remodeling index | 0.27 ± 0.06 | 0.18 ± 0.08 | 0.02 |

| LA volume index, ml/m2 | 33 ± 12 | 30 ± 7 | 0.4 |

| LV end-diastolic volume index, ml/m2 | 65 ± 10 | 58 ± 14 | 0.3 |

| LV end-systolic volume index, ml/m2 | 26 ± 5 | 24 ± 7 | 0.6 |

| LV ejection fraction, percent | 60 ± 5 | 62 ± 13 | 0.8 |

| LV mass index, g/m2 | 43 ± 9 | 37 ± 11 | 0.2 |

| LV remodeling index | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.7 |

| Aortic root size index, cm/m2 | 15 ± 2 | 15 ± 3 | 0.9 |

| Main PA size index, mm2/m2 | 15 ± 2 | 14 ± 2 | 0.1 |

| PA peak velocity, cm/sec | 83 ± 17 | 93 ± 18 | 0.4 |

| PA mean velocity, cm/sec | 11 ± 5 | 13 ± 3 | 0.2 |

| RV stroke volume, (L/min) | 82 ± 18 | 63 ± 21 | 0.06 |

| RV cardiac output (mls) | 6.3 ± 1.7 | 4.0 ± 1.5 | 0.007 |

| LV stroke volume (mls) | 82 ± 20 | 74 ± 13 | 0.28 |

| LV cardiac output (L/min) | 6.3 ± 1.7 | 4.9 ± 1.1 | 0.05 |

Results are expressed as mean + standard deviations.

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, LV: left ventricular, PA: pulmonary artery, RV: right ventricular.

Clinical parameters associated with increased RV mass in overlap syndrome

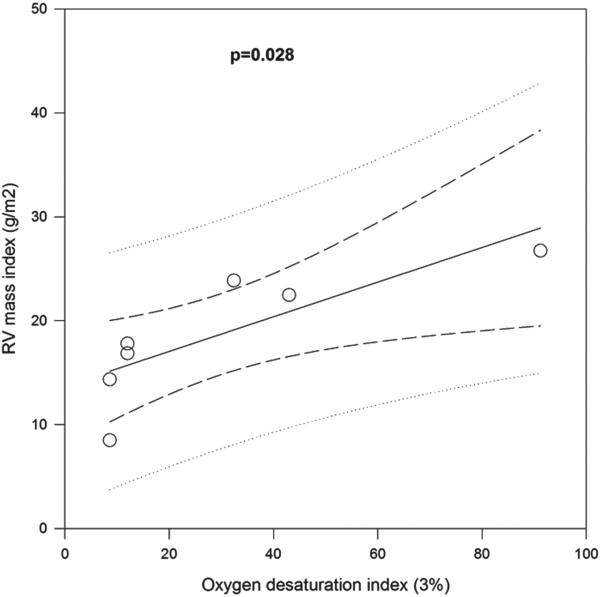

There was a significant correlation between the ODI and RV mass index in the overlap syndrome group (R2 = 0.65, p = 0.03; Figure 5). However, there was no significant correlation of RV mass index with total AHI, duration of OSA, lowest O2 saturation during polysomnography, duration of COPD, smoking history, or FEV1%. Similar results were also seen for RV remodeling index; there was no correlation of ODI with RVMI or RV remodeling index when COPD-only controls were also included.

Figure 5.

Correlation between right ventricular mass index and oxygen desaturation index during sleep in untreated overlap syndrome subjects (p = 0.03).

Discussion

This pilot study of a cohort of patients with COPD alone and patients with COPD and OSA (overlap syndrome) using cardiac MRI to evaluate heart size and function had two novel findings. First, the overlap syndrome is associated with increased RV mass and RV remodeling compared to COPD alone. Second, the extent of the adverse RV remodeling correlated with nocturnal oxygen desaturation.

The finding of an increase in RV mass and remodeling in the patients with overlap syndrome compared to those with COPD alone has not been demonstrated previously. The values for the RV mass index in the overlap syndrome patients are within the normal range (19); however, we believe this is likely a reflection of relatively preserved pulmonary function in these subjects.

The etiology of the increased RV mass is not entirely clear, however we suspect that the increase in RV mass is likely related to the greater degree of nocturnal desaturation in the overlap group as compared to the COPD-only group. We do not believe that the RV mass is related to the degree of obstructive lung disease given that the FEV1% was not statistically different between the two groups, but instead is likely due to the presence of ongoing obstructive events.

We did not directly measure right-sided pressures in the patients in this study; however we did use cardiac MRI to assess the right ventricle as an estimate of pulmonary pressures. MRI, with its high spatial and temporal resolution, is considered the ‘gold standard’ in functional assessment of the right ventricle (20, 21), and RV size and mass have been shown to provide a better estimate of outcomes that PA pressures (22).

Good inter-study reproducibility for RV function parameters has been demonstrated in healthy subjects, patients with heart failure, and patients with hypertrophy (23). At present, PA pressure cannot be measured directly by cardiac MRI, however, RVMI has been shown to correlate well with RV catheterization-derived mean PA pressure (23). One possible and likely reason for the increased RV mass in the patients with overlap syndrome compared with those with COPD alone is the fact that during sleep, higher PA pressure due to OSA may result in pressure overload and RV hypertrophy. Supporting this hypothesis, we found that RV hypertrophy and remodeling in the overlap syndrome group correlated with nocturnal oxygen desaturation, which is a potent stimulus for pulmonary artery vasoconstriction.

Interestingly, the total AHI did not correlate with RV changes, whereas there was a significant correlation between RV changes and nocturnal desaturation, leading us to suspect that the contribution of oxygenation may be more important than the presence of airway obstruction per se. RV remodeling in the overlap group in this study is also not likely explained by age, obesity, differences in degree of airway obstruction, hyperinflation, duration of COPD, and smoking history since the two groups were similar in these variables.

Pulmonary hypertension is seen in OSA in the absence of lung disease and is associated with nocturnal desaturation (6), small airway closure during tidal breathing, and increased PA response to nocturnal hypoxemia (8). A recent study showed that subclinical RV dysfunction may exist in OSA, even in the absence of PH (24). Increased PA size (25), reduced peak, and average PA velocity and reduced PA blood flow (26) have also been shown in PAH patients, and correlate with mean pulmonary artery pressure. Our data also show trends towards increased PA size, reduced PA peak and mean PA velocity, and reduced PA blood flow in overlap syndrome compared to COPD alone; however, the limited number of patients in this study may have limited the statistical power of these observations.

Seven overlap syndrome patients in this study were referred to our sleep clinic for further management. The mean duration of the OSA symptoms before the diagnosis in these patients was made at 20 months. We have previously shown that OSA is an under-diagnosed co-morbidity in COPD patients (27). This is important, because CPAP treatment has been shown to reverse pulmonary hypertension in OSA (8), and even reduce COPD-exacerbation related hospitalizations and mortality in patients with the overlap syndrome (4). Thus, it is important for pulmonologists to maintain a high suspicion for OSA in COPD patients.

Our study has some limitations. It included selected patients from a single medical center, which could affect the generalizability of our results. Our conclusions are therefore limited to the sample studied; however, we believe that our results are probably applicable to most urban medical centers. The pilot nature of the study resulted in a small sample size, although the marked differences in RV mass and RV remodeling index between overlap syndrome and COPD-only controls reached statistical significance. It is possible that our sample size was inadequate to detect statistically significant differences between other exploratory variables such as RA area, RV volumes, RVEF, PA size, PA blood flow and left sided indices like LA volume, LV volumes, mass and EF. We also did not directly measure pulmonary pressures, either invasively or with echocardiography. Despite these limitations, we believe that our findings are robust and may help to guide clinical practice and subsequent research studies.

In conclusion, untreated overlap syndrome may cause more extensive RV remodeling than COPD alone. Further data through mechanistic research and clinical trials are required to determine if this preliminary finding has an association with adverse clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Erik Smales for performing the polysomnography, Pamela DeYoung for scoring the polysomnography, and Alison Foster for assistance in study recruitment. We also thank staff at the Clinical Center for Investigation at Brigham and Women's Hospital for assistance in the study procedures.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grants R01 HL085188, R01 HL090897, K24 HL 093218, P01 HL 095491, R01- AG035117), American Heart Association 0840159N (PI Malhotra) and NIH Institutional T-32 grant (PI Charles Czeisler).

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

All authors have declared that they have no conflicts of interest regarding this work. The authors are responsible for the writing and the content of this paper.

References

- 1.Sanders MH, Newman AB, Haggerty CL, Redline S, Lebowitz M, Samet J, O'Connor GT, Punjabi NM, Shahar E. Sleep and sleep-disordered breathing in adults with predominantly mild obstructive airway disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003 Jan 1;167(1):7–14. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2203046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lopez AD, Shibuya K, Rao C, Mathers CD, Hansell AL, Held LS, Schmid V, Buist S. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: current burden and future projections. Eur Respir J. 2006 Feb;27(2):397–412. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00025805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flenley DC. Sleep in chronic obstructive lung disease. Clin Chest Med. 1985 Dec;6(4):651–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Machado MC, Vollmer WM, Togeiro SM, Bilderback AL, Oliveira MV, Leitao FS, Queiroga F, Jr., Lorenzi-Filho G, Krishnan JA. CPAP and survival in moderate-to-severe obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome and hypoxaemic COPD. Eur Respir J. 2010 Jan;35(1):132–137. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00192008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marin JM, Soriano JB, Carrizo SJ, Boldova A, Celli BR. Outcomes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and obstructive sleep apnea: the overlap syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010 Aug 1;182(3):325–331. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200912-1869OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaouat A, Weitzenblum E, Krieger J, Ifoundza T, Oswald M, Kessler R. Association of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and sleep apnea syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995 Jan;151(1):82–86. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.1.7812577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fletcher EC, Schaaf JW, Miller J, Fletcher JG. Long-term cardiopulmonary sequelae in patients with sleep apnea and chronic lung disease. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987 Mar;135(3):525–533. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1987.135.3.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arias MA, Garcia-Rio F, Alonso-Fernandez A, Martinez I, Villamor J. Pulmonary hypertension in obstructive sleep apnoea: effects of continuous positive airway pressure: a randomized, controlled cross-over study. Eur Heart J. 2006 May;27(9):1106–1113. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sajkov D, Wang T, Saunders NA, Bune AJ, Neill AM, Douglas Mcevoy R. Daytime pulmonary hemodynamics in patients with obstructive sleep apnea without lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999 May;159(5 Pt 1):1518–1526. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.5.9805086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sallach SM, Peshock RM, Reimold S. Noninvasive cardiac imaging in pulmonary hypertension. Cardiol Rev. 2007 Mar-Apr;15(2):97–101. doi: 10.1097/01.crd.0000253644.43837.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher MR, Criner GJ, Fishman AP, Hassoun PM, Minai OA, Scharf SM, Fessler HE. Estimating pulmonary artery pressures by echocardiography in patients with emphysema. Eur Respir J. 2007 Nov;30(5):914–921. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00033007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roeleveld RJ, Vonk-Noordegraaf A, Marcus JT, Bronzwaer JG, Marques KM, Postmus PE, Boonstra A. Effects of epoprostenol on right ventricular hypertrophy and dilatation in pulmonary hypertension. Chest. 2004 Feb;125(2):572–579. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.2.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Wolferen SA, Marcus JT, Boonstra A, Marques KM, Bronzwaer JG, Spreeuwenberg MD, Postmus PE, Vonk-Noordegraaf A. Prognostic value of right ventricular mass, volume, and function in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2007 May;28(10):1250–1257. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Buist SA, Calverley P, Fukuchi Y, Jenkins C, Rodriguez-Roisin R, van Weel C, Zielinski J. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007 Sep 15;176(6):532–555. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-456SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller A, Enright PL. PFT interpretive strategies: American Th oracic Society/European Respiratory Society 2005 guideline gaps. Respir Care. 2012 Jan;57(1):127–133. doi: 10.4187/respcare.01503. discussion 33–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruehland WR, Rochford PD, O'Donoghue FJ, Pierce RJ, Singh P, Th ornton AT. The new AASM criteria for scoring hypopneas: impact on the apnea hypopnea index. Sleep. 2009 Feb;32(2):150–157. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.2.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: The Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991 Dec;14(6):540–545. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawut SM, Lima JA, Barr RG, Chahal H, Jain A, Tandri H, Praestgaard A, Bagiella E, Kizer JR, Johnson WC, Kronmal RA, Bluemke DA. Sex and race differences in right ventricular structure and function: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis-right ventricle study. Circulation. 2011 Jun 7;123(22):2542–2551. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.985515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hudsmith LE, Petersen SE, Francis JM, Robson MD, Neubauer S. Normal human left and right ventricular and left atrial dimensions using steady state free precession magnetic resonance imaging. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2005;7(5):775–772. doi: 10.1080/10976640500295516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mogelvang J, Stubgaard M, Th omsen C, Henriksen O. Evaluation of right ventricular volumes measured by magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Heart J. 1988 May;9(5):529–533. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a062539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tandri H, Daya SK, Nasir K, Bomma C, Lima JA, Calkins H, Bluemke DA. Normal reference values for the adult right ventricle by magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Cardiol. 2006 Dec 15;98(12):1660–1664. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Champion HC, Michelakis ED, Hassoun PM. Comprehensive invasive and noninvasive approach to the right ventricle-pulmonary circulation unit: state of the art and clinical and research implications. Circulation. 2009 Sep 15;120(11):992–1007. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.674028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grothues F, Moon JC, Bellenger NG, Smith GS, Klein HU, Pennell DJ. Interstudy reproducibility of right ventricular volumes, function, and mass with cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Am Heart J. 2004 Feb;147(2):218–223. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minai OA, Ricaurte B, Kaw R, Hammel J, Mansour M, McCarthy K, Golish JA, Stoller JK. Frequency and impact of pulmonary hypertension in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2009 Nov 1;104(9):1300–1306. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fletcher CM. The clinical diagnosis of pulmonary emphysema; an experimental study. Proc R Soc Med. 1952 Sep;45(9):577–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanz J, Kuschnir P, Rius T, Salguero R, Sulica R, Einstein AJ, Dellegrottaglie S, Fuster V, Rajagopalan S, Poon M. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: noninvasive detection with phase-contrast MR imaging. Radiology. 2007 Apr;243(1):70–79. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2431060477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharma B, Feinsilver S, Owens RL, Malhotra A, McSharry D, Karbowitz S. Obstructive airway disease and obstructive sleep apnea: effect of pulmonary function. Lung. 2011 Feb;189(1):37–41. doi: 10.1007/s00408-010-9270-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]