Abstract

Objective

Although an extensive number of studies have attempted to identify predictors of new-onset atrial fibrillation (AFIB) after coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), a strong predictive model does not exist. Prior studies have included patients recruited from multiple centers with variant AFIB prevalence rates and those who underwent CABG in combination with other surgical procedures. Also, most studies have focused on pre- and perioperative characteristics, with less attention given to the initial postoperative period. The purpose of this study was to comprehensively examine pre-, peri-, and postoperative characteristics that might predict new-onset AFIB in a large sample of patients undergoing isolated CABG in a single medical center, utilizing data readily available to clinicians in electronic data repositories. In addition, length of stay and selected postoperative complications and disposition were compared in patients with AFIB and no AFIB.

Design

Retrospective, comparative survey.

Setting

University-affiliated tertiary care hospital.

Patients

Patients with new-onset AFIB who underwent isolated standard CABG or minimally invasive direct vision coronary artery bypass were identified from an electronic clinical data repository.

Interventions

None.

Measurements and Main Results

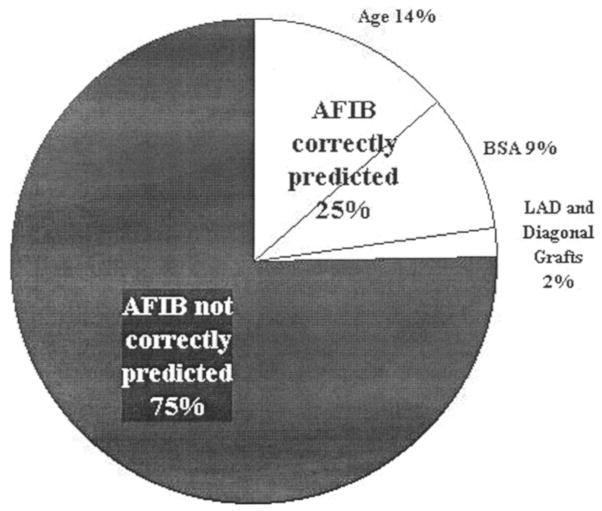

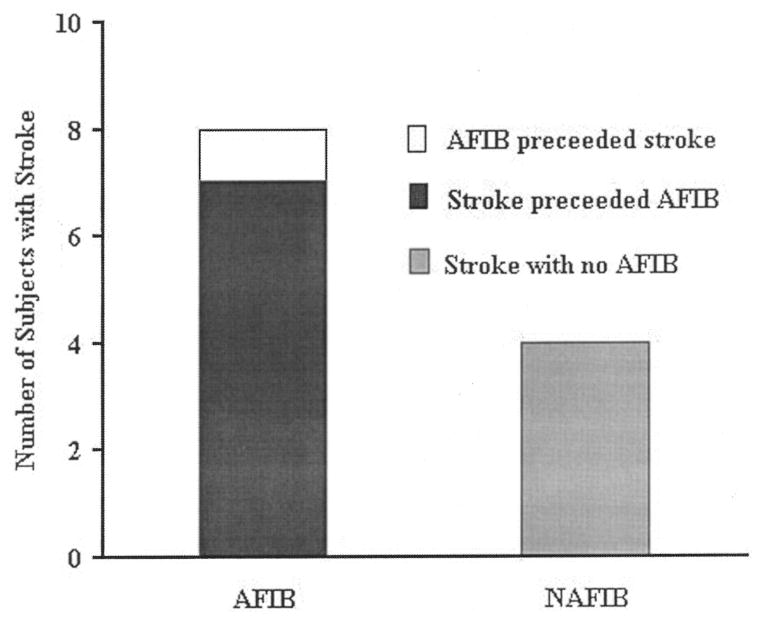

The prevalence of AFIB in the total sample (n = 814) was 31.9%. Predictors of AFIB included age (p = .0004), number of vessels bypassed (p = .013), vessel location (diagonal [p < .003] or posterior descending artery [p < .001]), and net fluid balance on the operative day (p = .015). Forward stepwise regression analysis produced a model that correctly predicted AFIB in only 24% of cases, with age (14%) and body surface area (9%) providing the most prediction. The incidence of embolic stroke was higher in AFIB (n = 8) vs. no AFIB (n = 4) patients, but stroke preceded AFIB onset in seven of eight cases. Subjects with AFIB had a longer stay (p = .0004), more intensive care unit readmissions (p = .0004), and required more assistance at hospital discharge (p = .017).

Conclusions

Despite attempts to examine comprehensively predictors of new-onset AFIB, we were unable to identify a robust predictive model. Our findings, in combination with prior work, imply that it may not be feasible to predict the development of new-onset AFIB after CABG using data readily available to the bedside clinician. In this sample, stroke was uncommon and, when it occurred, preceded AFIB in all but one case. As anticipated, AFIB increased length of stay, and patients with this complication required more assistance at discharge.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, resource utilization, coronary artery bypass grafting, minimally invasive direct vision coronary artery bypass grafting

Atrial fibrillation (AFIB) is the most common complication after coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), with an incidence ranging from 5% to 40% (1–5). Although post-CABG AFIB is not associated with a significant increase in mortality (6), it has been noted to result in increased morbidity related to postoperative stroke (7, 8), hemodynamic compromise (9), ventricular dysrhythmias (10), and iatrogenic complications associated with treatment (11). Most commonly, post-CABG AFIB lengthens hospitalization (10, 12, 13). As the search for successful prophylactic strategies continues, the development of a strong prediction model that would permit targeted prophylaxis remains elusive. Increased age is the only characteristic consistently identified as a risk factor for post-CABG AFIB (1, 4, 9, 14–20).

Potentially, the heterogeneous nature of prior samples contributed to inability to identify subjects at highest risk for post-CABG AFIB. In prior reports, samples from multiple centers with variant AFIB prevalence rates were combined to achieve a large sample size. Further, some studies included subjects who underwent prosthetic valve replacement or concomitant surgery at the time of CABG or had a prior history of AFIB, potentially confounding results and obscuring the predictive relationships. Additionally, it has been suggested that cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) may contribute to the incidence of postoperative AFIB (4). However, few studies have compared AFIB prevalence in patients undergoing standard CABG (SCABG) with CPB and minimally invasive direct vision coronary artery bypass (MIDCAB) without CPB (21). Finally, most studies have examined patient characteristics in the pre- and perioperative phase of care, but not in the immediate postoperative phase before AFIB onset.

The purpose of this study was to comprehensively identify pre-, peri-, and initial postoperative characteristics that predict new-onset AFIB in a large sample of patients undergoing isolated CABG in a single medical center. In addition, the impact of selected postoperative complications (stroke, pulmonary complications), length of stay (LOS), and disposition were compared in subjects with AFIB and no AFIB (NAFIB).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample Identification

After Institutional Review Board approval (March 13, 1998), data were retrospectively obtained for a 25-month interval (May 1, 1996, to May 5, 1998) from the Medical ARchival System ([MARS], Medical ARchival System, Pittsburgh, PA) or the bedside critical care information system ([CCIS], Eclypsis, Delray Beach, FL) at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center-Health System. The data elements examined were limited to those available for the majority of subjects within these two electronic data repository systems. MARS is a repository for information forwarded from the health system’s electronic clinical, administrative, and financial databases. MARS is indexed on every word and will recover all encounters for a given patient between specific dates (22). All subjects were >18 yrs of age and underwent isolated SCABG or MIDCAB (International Classification of Diseases [ICD]-9 CM procedure codes 36.10–36.16 from the medical record discharge abstracts). Exclusion criteria were prior history of AFIB (both active and inactive); prior or current heart, lung, or heart-lung transplant; prior or current ventricular assist device; prior or current heart valve replacement or repair; any other surgical procedure during current admission; perioperative or postoperative myocardial infarction; and death in the operating room (OR) or within 12 hrs after surgery. Prior CABG was not an exclusion criterion. All subjects participated in the routine AFIB prophylaxis strategy in effect during the study period that included magnesium supplementation in the OR, upon intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and the first postoperative day, and beta-blocker administration beginning the first postoperative day, if permitted by heart rate, blood pressure, and cardiac index evaluation.

Subjects were initially identified via procedure codes, then review of operative reports to identify SCABG vs. MIDCAB and number and location of vessels bypassed. To identify new-onset AFIB, we first identified patients who had an ICD-9-CM code for AFIB (427.31) from the medical records discharge abstract in MARS. Because ICD-9 code assignment does not differentiate between new-onset and pre-existing AFIB, discharge summaries for all patients with code 427.31 were reviewed to verify that AFIB had occurred and determine whether AFIB was a new or prior problem (full chart review if necessary). Second, the electronic clinical record repository for all remaining patients (no ICD-9 CM code 427.31) who underwent SCABG or MIDCAB was subjected to a MARS word search (“AFIB,” “atrial fib,” “atrial dysrhythmia,” or word variations) and a determination made for new-onset or prior AFIB as described for positive searches. Third, the MARS pharmacy records were queried for procainamide administration for all patients not identified as having new-onset AFIB in the previous two steps, and a positive search evaluated as previously described. Subjects with a questionable AFIB status were eliminated from the study. A total of 997 patients were identified as having SCABG or MIDCAB surgery within the 25-month time frame. Of these, 63 were excluded because of preexisting AFIB (active or inactive) and 120 due to either more than one surgical procedure during the admission, or death during or within 12 hrs of operation. The triangulated method identified new-onset AFIB in a total of 260 subjects identified by ICD-9-CM code (56.9%), word search (37.7%), and procainamide query (5.4%). The final sample included 814 subjects (NAFIB = 554, AFIB = 260).

Preoperative predictors were age, gender, height, weight, body surface area (BSA), and past medical problems. To identify past medical problems, ICD-9-CM codes within similar disease categories were clustered. Disease clusters with cumulative subject frequencies >75 (more than 75 subjects were coded for health problems within that disease cluster) were selected for analysis. Diseases with cumulative subject frequencies >75 were old myocardial infarction, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and heart failure. The disease cluster hypertension was excluded from the analysis, as it was coded for in almost the entire sample (n = 739).

Perioperative predictors were type of surgery (SCABG vs. MIDCAB), number and location of vessels bypassed, and time in the OR. Postoperative predictors were the first postoperative central venous pressure, net fluid balance in the OR and on first postoperative day, and first postoperative surface electrocardiogram (ECG) report.

Postoperative Complications, LOS, and Disposition

Comparisons were made for two postoperative complications: embolic stroke prevalence and postoperative pulmonary complications. Stroke prevalence was determined by identifying all AFIB and NAFIB patients with a computed tomography (CT) report for a head CT scan, reviewing these medical records to determine whether embolic stroke was confirmed; and identifying time of onset. ICD-9 codes were used to identify other postoperative complications. LOS and discharge disposition data were evaluated for SCABG subjects alone because differences inherent to the two procedures (SCABG vs. MIDCAB) could impact hospital stay for reasons not related to AFIB, thereby confounding results. The discharge disposition codes were obtained via MARS from the hospital medical records abstract data. These codes were then collapsed into four discharge categories: discharged to home without assistance, home with health agency assistance, posthospital care facility, or mortality.

Statistical Analysis

All data were transferred from the MARS and CCIS into the Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Office 97, Microsoft, Redmond, WA) utilizing unique subject identifiers later stripped to preserve confidentiality. Differences in AFIB prevalence were examined using the chi-square test for proportions. Between-group comparisons were made using Student’s t-tests for continuous and chi-square for categorical variables. A value of p < .05 was considered significant. When several variables in a category were analyzed, a Bonferroni correction was made and the alpha divided evenly across multiple variables. Logistic regression was applied to examine the pre-, peri-, and postoperative variables’ likelihood of predicting AFIB.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

Subjects were 65.5 ± 10.2 yrs of age, predominately male (66.9%), and Caucasian (92.3%). Most (88.5%) underwent SCABG. The mean number of vessels bypassed for the total sample was 3.3 ± 1.2 (mean ± SD). A minority (n = 2) died during hospitalization. There were no differences between SCABG and MIDCAB subjects on any demographic variable other than number of vessels bypassed (p = .000).

Predictors

Preoperative Characteristics

AFIB occurred in approximately one-third of subjects (31.9%) (Table 1). AFIB subjects were older than NAFIB subjects (69.6 ± 7.9 vs. 63.6 ± 10.6 yrs, p = .0004). AFIB subjects also differed in regard to height (p = .013), but this finding bears little clinical usefulness. There were no significant between group differences in gender, weight, BSA, or past medical problems.

Table 1.

Preoperative characteristics of subjects with no atrial fibrillation (NAFIB) and atrial fibrillation (AFIB)

| Characteristica | NAFIB (n = 554) Mean ± SD n (%) |

AFIB (n = 260) Mean ± SD n (%) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yrs | 63.6 ± 10.6 | 69.6 ± 7.9 | 0.0004 |

| Male (%) | 363 (65.5%) | 183 (70.4%) | 0.169 |

| Height, cm | 170.4 ± 10.3 | 171.0 ± 10.8 | 0.013 |

| Weight, kg | 83.7 ± 17.4 | 85.0 ± 16.5 | 0.569 |

| Body surface area, m2 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 1.97 ± 0.2 | 0.099 |

| Past medical problems Defined by ICD-9 codeb | |||

| Diabetes | 149 (26.9%) | 81 (31.2%) | 0.208 |

| Old MI | 162 (29.2%) | 74 (28.5%) | 0.819 |

| Heart failure | 54 (9.7%) | 25 (9.6%) | 0.953 |

| COPD | 59 (10.6%) | 32 (12.3%) | 0.484 |

ICD, International Classification of Diseases; MI, myocardial infarction; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Complete data available for all NAFIB subjects (n = 554) except height (n = 550), weight (n = 553), and body surface area (BSA) (n = 548) and all AFIB subjects (n = 260) except height (n = 258) and BSA (n = 258);

subjects may have more than one medical problem.

Perioperative Characteristics

There was a trend (p = .059) toward a higher AFIB prevalence rate for SCABG subjects (33.1%) compared with MIDCAB subjects (23.4%) (Table 2). AFIB and NAFIB subjects differed in the number of vessels bypassed (p = .013). More NAFIB subjects had one vessel (15.7% NAFIB vs. 8.1% AFIB) or two vessels bypassed (10.7% NAFIB vs. 9.6% AFIB), almost identical proportions of subjects had three vessels bypassed, but more AFIB subjects had four (36.5% AFIB vs. 33.5% NAFIB) or five or more vessels bypassed (16.9% AFIB vs. 11.4% NAFIB). A greater proportion of subjects who developed AFIB received saphenous vein grafts to unspecified diagonal arteries (43.1% AFIB vs. 32.5% NAFIB, p = .003) and the posterior descending artery (59.6% AFIB vs. 47.5% NAFIB, p = .001). There were no significant between-group differences for any other vessel location. Although the actual length of surgery was not obtained, AFIB and NAFIB patients had a similar number of OR charge hours (3.7 ± 0.9 vs. 3.8 ± 0.8 respectively, p = .538).

Table 2.

Perioperative characteristics of subjects with no atrial fibrillation (NAFIB) and atrial fibrillation (AFIB)

| Characteristica | NAFIB

|

AFIB

|

p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Surgical procedure | .059 | ||||

| Standard CABG | 482 | 66.9 | 238 | 33.1 | |

| MIDCAB | 72 | 76.6 | 22 | 23.4 | |

| No. of vessels bypassed | .013 | ||||

| One | 87 | 15.7 | 21 | 8.1 | |

| Two | 59 | 10.7 | 25 | 9.6 | |

| Three | 159 | 28.8 | 75 | 28.8 | |

| Four | 185 | 33.5 | 95 | 36.5 | |

| Five or more | 63 | 11.4 | 44 | 16.9 | |

| Name of vessels bypassed (each subject may have >1) | |||||

| LIMA to LAD | 463 | 83.5 | 228 | 87.5 | .108 |

| SVG to LAD | 68 | 10.8 | 22 | 8.5 | .106 |

| Radial to LAD | 0 | 1 | 0.4 | .144 | |

| RIMA to RCA | 11 | 1.9 | 1 | 0.4 | .078 |

| SVG to RCA | 108 | 19.5 | 46 | 17.7 | .549 |

| Diagonal unspecified | 180 | 32.5 | 112 | 43.1 | .003 |

| Diagonal 1 | 44 | 7.9 | 18 | 3.8 | .615 |

| Diagonal 2 | 22 | 3.9 | 6 | 2.3 | .226 |

| Marginal unspecified | 223 | 40.3 | 117 | 45.0 | .468 |

| Obtuse marginal 1 | 108 | 19.5 | 61 | 23.5 | .188 |

| Obtuse marginal 2 | 78 | 14.1 | 44 | 16.9 | .284 |

| Posterior descending | 263 | 47.5 | 155 | 59.6 | .001 |

| Circumflex | 74 | 13.4 | 42 | 16.1 | .282 |

| Acute marginal | 30 | 5.4 | 20 | 7.7 | .204 |

| Ramus intermedius | 46 | 8.3 | 30 | 3.8 | .137 |

CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; MIDCAB, minimally invasive direct vision coronary artery bypass; LIMA, left internal mammary artery; LAD, left anterior descending artery; SVG, saphenous vein graft; RIMA, right internal mammary artery; RCA, right coronary artery.

Complete data available for all AFIB subjects (n = 260) and all NAFIB subjects (n = 554) except number of vessels bypassed (n = 553).

Postoperative Characteristics

Net fluid balance on the operative day differed, with AFIB subjects having a greater positive net fluid balance (2110 ± 1699 mL) compared with NAFIB subjects (1796 ± 1725 mL, p = .015) (Table 3). The net fluid balance on the first postoperative day was similar between the two groups, as was the initial central venous pressure reading in the ICU. Initial postoperative ECG reports were available in 553 (68%) of the samples (Table 4). There were no significant between-group differences for cardiac rhythm, although there was a trend toward more subjects in the NAFIB group having normal sinus rhythm (74.1%) compared with the AFIB group (64.6%), and more subjects with AFIB exhibiting normal sinus rhythm with a first-degree atrioventricular block (13.7%) compared with NAFIB (5.9%) subjects. The occurrence of other types of dysrhythmias on the initial postoperative ECG was similar in both groups. There were also no significant between-group differences in rate/duration variables, or notations in the dictated summary regarding left bundle branch block, ischemia, or infarct. More subjects with AFIB had right bundle branch block (26.1% vs. 18.7%, p = .047), but this difference was not significant after application of the Bonferroni correction (α = 0.0125).

Table 3.

Postoperative fluid status of subjects with no atrial fibrillation (NAFIB) and atrial fibrillation (AFIB)

| Characteristic | NAFIB

|

AFIB

|

p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Data Available | Mean ± SD | No. of Data Available | Mean ± SD | ||

| First central venous pressure reading, mm Hg | 547 | 10.5 ± 4.3 | 257 | 10.4 ± 4.3 | .890 |

| Net fluid balance operative day, mL | 553 | 1796 ± 1725 | 260 | 2110 ± 1699 | .015 |

| Net fluid balance first postoperative day, mL | 552 | −397 ± 1157 | 259 | −358 ± 1255 | .674 |

Table 4.

Initial postoperative surface electrocardiogram of subjects with no atrial fibrillation (NAFIB) and atrial fibrillation (AFIB)

| Characteristica | NAFIB | AFIB | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rhythm, n (%) | 0.121 | ||

| Normal sinus (NSR) | 275 (74.1) | 113 (64.6) | |

| NSR with 1° block | 22 (5.9) | 24 (13.7) | |

| Sinus bradycardia (SB) | 20 (5.4) | 5 (2.9) | |

| SB with 1° block | 4 (1.1) | 4 (2.3) | |

| Sinus tachycardia (ST) | 42 (11.5) | 22 (12.5) | |

| ST with 1° block | 2 (0.5) | 0 | |

| AV dissociation | 1 (0.3) | 0.1 (0.6) | |

| Paced | 0 | 0.1 (0.6) | |

| Junctional | 0 | 0 | |

| Other | 4 (1.1) | 4 (2.2) | |

| Rate/duration | |||

| Ventricular rate, bpm | 80.7 ± 15.7 | 82.7 ± 16.3 | .186 |

| Atrial rate, bpm | 80.7 ± 15.6 | 82.4 ± 15.9 | .250 |

| PR, ms | 171.6 ± 82.6 | 175.7 ± 37.9 | .542 |

| QRS, ms | 100.2 ± 20.7 | 102.1 ± 22.2 | .341 |

| QT, ms | 405.4 ± 53.3 | 403.0 ± 53.7 | .620 |

| QTc, ms | 474.4 ± 11.7 | 466.1 ± 45.8 | .605 |

| P axis, degrees | 48.9 ± 21.1 | 45.2 ± 26.6 | .077 |

| R axis, degrees | 14.5 ± 44.4 | 14.0 ± 47.3 | .917 |

| T axis, degrees | 35.7 ± 61.6 | 41.1 ± 64.6 | .340 |

| Other, n (%)b | |||

| Left bundle branch block | 38 (10.2) | 21 (11.9) | .531 |

| Right bundle branch block | 70 (18.7) | 46 (26.1) | .047 |

| Ischemia | 70 (19.8) | 30 (24.5) | .223 |

| Infarct | 112 (32.0) | 45 (27.3) | .330 |

ECG reports were available for 553/720 subjects;

Bonferroni correction for four variables significant p = .0125.

Regression Analysis for Prediction

When a forward step-wise regression analysis for the potential predictors was performed (Fig. 1), only age, BSA, and two types of vessel bypasses—saphenous vein grafts to both the diagonal artery (unspecified) and the left anterior descending artery— entered into the model. Age correctly predicted AFIB in 14% of subjects, and BSA contributed an additional 9%. The addition of the two types of vessel bypasses added a modest 2% to the predictive model, with a final cumulative predictive percentage of 25% for the four variables. We repeated this analysis with SCABG subjects alone (MIDCAB cases removed), and only age, BSA, saphenous vein graft to the left anterior descending artery, and number of vessels bypassed entered into the model in a step-wise fashion. Again, age provided the greatest percentage of prediction (15.3%), with BSA adding an additional 8.1%. Entry of the left anterior descending artery and the number of vessels bypassed to the model added only 1.2%, for a cumulative total of 24.6%. Thus, the models permitted AFIB to be correctly predicted in only 24% of AFIB cases for both SCABG and MIDCAB or SCABG subjects alone. As a final step, postoperative variables were entered into regression analysis for the total sample of 814 subjects. None of these variables came forward in a stepwise fashion. The ECG variables of infarct, ischemia, and right and left bundle branch block entered the model equally, and correctly predicted AFIB in only 6.8% of cases.

Figure 1.

Ability of selected pre- and perioperative characteristics to predict atrial fibrillation (AFIB) in 230 AFIB cases after standard coronary artery bypass grafting and minimally invasive direct vision coronary artery bypass grafting by forward stepwise regression analysis. BSA, body surface area; LAD, left anterior descending artery.

Complications and LOS

An intra- or postoperative cerebral infarct occurred in only 12 (1.6%) subjects (Fig. 2): 4 (0.8%) NAFIB and 8 (3.4%) AFIB. The cerebral infarct preceded the onset of AFIB in seven of eight cases. Pulmonary complications were coded in 25.4% of SCABG subjects (25.2% AFIB vs. 25.5% NAFIB, p = .929). No other postoperative complication occurred in >50 subjects, so no further analyses were conducted.

Figure 2.

Comparison of embolic stroke prevalence for subjects with atrial fibrillation (AFIB) and no atrial fibrillation (NAFIB) after standard coronary artery bypass grafting (n = 720).

Total postoperative LOS was longer for subjects with AFIB (p = .0004) (Table 5). Subjects with AFIB also had a longer postoperative LOS in the ICU (p = .001), and were more likely to require ICU readmission (p = .0004). In addition, AFIB subjects had a longer LOS on the hospital ward (p = .0004). The overall difference between AFIB and NAFIB groups for the four disposition categories was statistically significant (p = .017), with a higher percentage of subjects with NAFIB discharged to home without assistance (34.6%) compared with AFIB subjects (29.5%) and a higher percentage of subjects with AFIB discharged to a posthospital care facility (19.7%) compared with those with NAFIB (13.1%). Both of the subjects who died in the hospital were in the AFIB group.

Table 5.

Length of stay and disposition after standard coronary artery bypass graft for no atrial fibrillation (NAFIB) and atrial fibrillation (AFIB) subjects

| Resourcea | NAFIB Mean ± SD n (%) |

AFIB Mean ± SD n (%) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| LOS | |||

| Total postoperative LOS | 4.4 ± 1.2 | 5.8 ± 2.4 | .0004 |

| Postoperative ICU LOS, days | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 1.5 ± 1.5 | .0010 |

| Readmission to ICU (%) | 1 (0.2) | 11 (4.6) | .0004 |

| Postoperative ward LOS | 3.3 ± 1.1 | 4.3 ± 1.7 | .0004 |

| Disposition | .017 | ||

| Home | 167 (34.6%) | 70 (29.5%) | |

| Home health agency | 252 (52.3%) | 119 (50%) | |

| Posthospital care facility | 63 (13.1%) | 47 (19.7%) | |

| Mortality | 0 | 2 (0.8%) | |

LOS, length of stay; ICU, intensive care unit.

Complete data available for 477/482 NAFIB subjects and all 238 AFIB subjects.

DISCUSSION

Preoperative Predictive Characteristics

Age is the variable most consistently associated with post-CABG AFIB (1, 4, 9, 11, 13, 16, 23–27). In this study, age provided the greatest contribution to the correct prediction of AFIB in the logistic regression model (14% of a total of 25% cumulative percent correct prediction). However, the difference in age between the groups was not large (6 yrs), and it therefore was not possible to identify an AFIB target age.

In this study, consistent with most studies, gender was not associated with higher AFIB prevalence rates (1, 15–16, 27–29). Also consistent with our findings, most investigators have not identified a relationship between preexisting medical conditions and AFIB (1, 13, 14, 18, 24, 25, 27, 28, 30–32). Two prior studies (4, 18) reported a relationship between AFIB and preexisting medical conditions. Leitch et al. (18) noted a relationship with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic renal insufficiency and old myocardial infarction, and Mathew et al. (4) with heart failure. In both studies, hard-copy medical records were reviewed to identify these conditions. In our study, preexisting medical conditions were identified from ICD-9 CM codes, which likely underestimated their true prevalence.

Perioperative Predictive Characteristics

It has been proposed that CPB might impact AFIB prevalence. Consequently, we anticipated finding a significant difference between AFIB prevalence in SCABG and MIDCAB subjects. However, the difference in AFIB prevalence in SCABG (33.1%) and MIDCAB (23.4%) subjects approached but did not achieve accepted levels for statistical significance (p = .059). The prevalence of AFIB in MIDCAB subjects was higher than that reported by Subramanian et al. (33) of 7% or Zenati et al. (21) of 6%, but compared closely with that reported by Tamis et al. (34) and Cohn et al. (35) from their separate series of MIDCAB patients (26% both studies).

Several studies have reported a relationship between the number of vessels bypassed and AFIB prevalence (12, 14, 15, 18, 27, 28), with most reporting that AFIB prevalence increases with the number of vessels bypassed. Few studies have examined the relationship between the location of vessel bypassed and AFIB prevalence and findings are conflicting. Mendes et al. (25) noted a relationship between post-CABG AFIB and right coronary artery stenosis, with 43% of those patients with severe right coronary artery stenosis (>70% stenosis) developing AFIB, compared with 19% without this problem. In stepwise regression analysis, age was the most powerful predictor for AFIB, followed by right coronary artery stenosis. Conversely, Zaman et al. (29) did not find a significant relationship between AFIB and right coronary artery stenosis. In our study, we also noted that AFIB prevalence significantly increased as the number of bypasses increased. AFIB prevalence was associated with saphenous vein grafts to the diagonal artery (branch not specified) (p = .003) and the posterior descending artery (p = .001). Although we did not find a relationship between AFIB prevalence and grafts to the right coronary artery, there was a significant relationship when the posterior descending branch was involved (p = .001).

Postoperative Predictive Characteristics

Our attempt to increase predictive ability by examining initial postoperative characteristics did not yield helpful findings. AFIB subjects exhibited a more positive net fluid balance for the operative day (p = .015), but the mean difference was only 314 mL. Prior studies examining postoperative predictors are limited and varied in focus. Frost et al. (16) noted a significant difference in central venous pressure at the time of weaning from CPB in AFIB vs. NAFIB (p = .02) and upon admission to the ICU (p = .02), but the difference was only 2 mm Hg and thus of little clinical significance. Ott et al. (26) tested early diuresis as a means to reduce AFIB prevalence, but diuresis was applied in addition to digoxin, thyroid supplementation, and low-dose steroid administration, confounding the interpretation. Braithwaite and Weissman (36) discovered that subjects undergoing noncardiothoracic surgery who had new-onset postoperative atrial arrhythmias received more intravenous fluid in the days before achieving a negative fluid balance (16 L vs. 10.8 L, p = .01), and achieved a negative fluid balance later than the group who did not experience atrial dysrhythmias (3.2 days vs. 2.5 days, respectively, p < .05). Our findings support the supposition that a more positive fluid balance may facilitate AFIB, perhaps because of atrial distention. However, the between-group difference was small, and there was substantial within-group variability.

No other studies have examined the relationship between variables associated with the first postoperative surface ECG and AFIB prevalence. However, other researchers have examined preoperative ECG data. Dimmer et al. (23) noted that a longer P-wave duration on the surface ECG was associated with a higher incidence of AFIB, although only age and the signal-averaged ECG P-wave entered their regression model. Other teams (32, 37, 38) noted trends toward longer P-wave durations on surface ECG and AFIB, but no statistical significance. In each study, signal-averaged ECG data were significantly better at predicting AFIB than surface ECG data. In this study, data from the first postoperative surface ECG did not reveal a significantly different PR interval for AFIB subjects (AFIB 175.7 ± 37.9 vs. 171.6 ± 82.6 msec, p = .542). Likewise, the remainder of the rate and duration ECG data did not reveal differences between the groups. Although a greater percentage of subjects with AFIB displayed a right bundle branch block (p = .047), the difference was not statistically significant when a Bonferroni correction was applied.

We likewise did not identify statistical significance between the initial postoperative cardiac rhythm and AFIB prevalence, although some trends were noted. The AFIB group tended to be less likely to be in normal sinus rhythm on the first ECG (AFIB 64.6% vs. 74.1%), but more likely to display sinus rhythm with a first degree AV block (AFIB 13.7% vs. 5.9%). In our study, we utilized data from the first postoperative ECG whereas other teams have used preoperative evaluation of baseline conduction or rhythm abnormalities. In spite of our evaluation of surface ECG at a more vulnerable period and a robust sample size, between-group differences were not significant, although trends were noted that indicated that delayed conduction might predispose to AFIB.

Regression Analysis

When the pre- and perioperative predictive variables for this study were entered into a logistic regression analysis, four variables entered in a stepwise fashion: age contributed to correct prediction of AFIB in 14% of cases; BSA added an additional 9%; and two types of vessel bypasses, vein grafts to the diagonal (unspecified branch) and left anterior descending arteries contributed very modestly, for a cumulative prediction of 25%. When the sample was limited to SCABG subjects only, the model did not change or improve appreciably. When the regression analysis was repeated using postoperative characteristics for the entire sample, no variables came forward for stepwise entry, and a combination of ECG data— evidence of infarct, ischemia, and right and left bundle branch block— only predicted AFIB correctly in 6.8% of cases.

The results of our regression analysis are similar to the results of others with respect to age (4, 18, 24, 39). Almassi et al. (1) reported a model that found age to be the strongest predictor for AFIB, followed by vein venting, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, use of digoxin, and heart rate <80 beats per minute. Aranki et al. (13) also reported a model with age the strongest predictor, followed by male gender, hypertension, intra-aortic balloon pump, postoperative pneumonia, prolonged mechanical ventilation, and ICU readmission. Neither study related a cumulative percentage of prediction for the model. Age was also found to be the best predictor of AFIB in studies where signal-averaged ECG data were utilized in the model (16, 23). When Frost et al. (16) performed regression analysis on a variety of variables in a study utilizing P-wave duration and morphology on signal-averaged ECG, they noted that only increased age (>60 yrs) and increased body weight (> 80 kg) were independent predictors of AFIB, for a cumulative positive prediction of 37%. Fuller et al. (7) reported a model based on age, gender, and beta-blockade that had a median predictive probability of 34% for subjects who had postoperative AFIB, and 28% for those who did not. DeJong and Morton (40) identified age and right coronary artery stenosis as correctly predicting AFIB in 26.9% of AFIB cases, although the sample size was small (only 52 subjects with AFIB). Our study is unique in that we enrolled a large sample of patients undergoing isolated CABG in a single medical center and comprehensively examined predictors of new-onset AFIB, utilizing practically accessible data elements. Nevertheless, we were unable to identify a robust predictive model. Our findings, in combination with prior work, strongly imply that it may not be feasible to predict development of new-onset AFIB after CABG using data readily available to the bedside clinician. A more appropriate goal may be to identify more cost-effective approaches to manage AFIB if it occurs or to identify drug therapy that is less toxic and could therefore be used as prophylaxis for the entire population of CABG patients.

Complications

We found an overall prevalence rate for stroke of 1.4% (0.8% of NAFIB and 3.4% of AFIB subjects). Other investigators have reported rates ranging from 2% (NAFIB) to 7% (AFIB) (4). Our lower stoke prevalence may in part be because of our exclusion of subjects undergoing valve replacement and preexisting AFIB. Our most striking finding is the discovery that, although we noted a three-fold increase in stroke for our AFIB subjects, the stroke event preceded AFIB onset in seven of eight cases. It would therefore appear that, in this sample, AFIB is a morbidity of stroke, rather than the inverse, as widely accepted (7– 8). It is possible that when patients develop stroke, strong sympathetic stimulation coupled with older age and (perhaps) some mild degree of cardiac conduction delay facilitates AFIB genesis. An important incidental finding is that no stroke developed in any MIDCAB subject.

LOS

Subjects with new-onset AFIB had a longer postoperative LOS, with the majority of their lengthened stay on the ward. The usual onset of AFIB is 2– 4 days after surgery (5, 11, 28, 29, 32, 38, 41), thus it would be expected that AFIB onset occurred on the ward. Eleven subjects (4.6% of AFIB group) were readmitted to the ICU, compared with only 1 NAFIB subject (0.2% of NAFIB). Mathew et al. (4) noted that subjects with AFIB remained an average of 0.5 days in the ICU and 2.0 days on the ward. Aranki et al. (13) noted an overall increase in length of stay of 4.9 days for subjects with AFIB, and an ICU readmission rate of 9% for AFIB vs. 2%. Almassi et al. (1) reported a longer stay in the hospital, longer time in the ICU, and more frequent ICU readmission in AFIB subjects. Using multivariate analysis with adjustment for age, gender, and race, Borzak et al. (42) found that, although AFIB subjects were older, the increased LOS was attributable to the AFIB and not age itself. There is wide variation in the reported LOS between centers. However, all reports agree that patients with AFIB are in the ICU and on the ward longer, and our results concur with others.

In this study, we noted an overall mortality rate of 0.25%, although both patients who died had AFIB (0.8% within AFIB subjects). This mortality rate is low compared with the range of 1.7% (18) to 3.5% (30) reported by others. We did, however, eliminate subjects who died within 12 hrs of surgery because their early death would have confounded the interpretations for AFIB prevalence and LOS. No other study has commented upon disposition at discharge beyond mortality. We see our findings related to disposition as important. More subjects with NAFIB were discharged to home without any type of care assistance (AFIB 29.5% vs. 34.6%), and more subjects with AFIB required admission to posthospital care facilities (AFIB 19.7% vs. 13.1%). Thus, subjects who develop AFIB are more likely to require continuing care following discharge, and consume more resources and healthcare dollars even after discharge from the acute care facility than those with NAFIB.

Limitations

Because the sample included subjects with SCABG and MIDCAB, time on CPB, time on mechanical ventilation, and inotropic support were not examined for predictive capability, as their incidence and duration could have been associated with the operative procedure as well as AFIB prevalence, making interpretation of a predictive result difficult. Several additional variables were not available in the electronic medical record in the majority of cases and therefore were not included in the analysis, e.g., preoperative cardiac catheterization reports and echocardiograms were electronically retrievable in a minority (<10%) of cases and aortic cross-clamp and CPB times (for SCABG subjects) were not available in the electronic record. It is possible that inclusion of these variables may have altered the model. However, prior studies have not shown these variables to be consistently predictive of new-onset AFIB after CABG.

CONCLUSION

The major findings in this study are 1) a trend toward lower AFIB prevalence in MIDCAB subjects; 2) a significant difference between AFIB and NAFIB subjects with respect to age, number of vessels bypassed, location of vessel (diagonal and posterior descending arteries), and net fluid balance on the day of operation; 3) the lack of a strong prediction model; and 4) stroke preceded AFIB in most cases, although the overall incidence was low.

Despite the utilization of a homogeneous and robust data set from a single center comprised of subjects without prior AFIB or valve surgery who underwent isolated CABG, we were not able to develop a strong model that would enable clinicians to target AFIB prophylaxis to a specific subset of patients. It is likely that it is not possible to develop a sensitive and specific model utilizing data elements that are readily available to bedside clinicians using current resources. It is therefore wise to maintain efforts to develop prophylactic strategies that could be applied to all bypass patients and provide an adequate AFIB inhibitory benefit at low toxicity and cost. Two further areas for study include evaluating the impact of consistent AFIB management strategies (e.g., protocols, care pathways) and comparing the efficacy and cost effectiveness of our treatments of AFIB once it has concurred. It is possible that, even if prevalence cannot be diminished, implementing lower-cost drugs (if acceptably efficacious) or protocolizing post-CABG AFIB care and developing care pathways might decrease the LOS and resource utilization.

Acknowledgments

We thank Julie F. Cuneo, RN, MSN, CRNP, and Stacey DaPos, MS, RHIA, for assistance with data collection and screening, and John M. Clochesy, RN, PhD, for input regarding study design.

References

- 1.Almassi GH, Schowalter T, Nicolasi AC, et al. Atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: A major morbid event? Ann Surg. 1997;226:501–513. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199710000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bietz DS. Rapid recovery in the elderly. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;64:1222. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)00642-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kowey PR, Dallessandro DA, Herbertson R, et al. Effectiveness of digitalis with or without acebutolol in preventing atrial arrhythmias after coronary artery surgery. Am J Cardiol. 1997;79:1114–1117. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathew JP, Parks R, Savino JS, et al. Atrial fibrillation following coronary artery bypass graft surgery: Predictors, outcomes and resource utilization. JAMA. 1996;276:300–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalman JM, Munawar M, Howes LG, et al. Atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting is associated with sympathetic activation. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60:1709–1715. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00718-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rady MY, Ryan T, Starr N. Perioperative determinants of morbidity and mortality in elderly patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:225–235. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199802000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuller JA, Adams G, Buxton B. Atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting: Is it a disorder of the elderly? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1989;97:821– 825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor GJ, Malik SA, Colliver JA, et al. Usefulness of atrial fibrillation as a predictor of stroke after isolated coronary artery bypass grafting. Am J Cardiol. 1987;60:905–907. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(87)91045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lauer MS, Eagle KA, Buckley MJ, et al. Atrial fibrillation following coronary artery bypass surgery. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1989;31:367–378. doi: 10.1016/0033-0620(89)90031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Creswell LL, Schuessler RB, Rosenbloom M, et al. Hazards of postoperative atrial arrhythmias. Ann Thorac Surg. 1993;56:539–549. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(93)90894-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olshansky B. Management of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass graft. Am J Cardiol. 1996;78:27–34. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00563-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kolkevar S, D’Souza AD, Akhatar P, et al. Role of atrial ischaemia in development of atrial fibrillation following coronary artery bypass surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1997;11:70–75. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(96)01095-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aranki SF, Shaw DP, Adams DH, et al. Predictors of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery surgery: Current trends and impact on hospital resources. Circulation. 1996;94:390–397. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asimakopoulos G, Santa RD, Taggart DP. Effects of posterior pericardiotomy on the incidence of atrial fibrillation and chest drainage after coronary revascularization: A prospective randomized trail. J Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;113:797–799. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(97)70242-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crosby LH, Pifalo B, Woll KR, et al. Risk factors for atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting. Am J Cardiol. 1990;66:1520–1522. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)90550-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frost L, Lund B, Pilegaard H, et al. Reevaluation of the role of P-wave duration and morphology as predictors of atrial fibrillation and flutter after coronary artery bypass surgery. Eur Heart J. 1996;1:1065–1071. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frost L, Jacobsen CJ, Christiansen EH, et al. Hemodynamic predictors of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter after coronary artery bypass grafting. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1995;39:690– 697. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1995.tb04149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leitch JW, Thomson D, Baird DK, et al. The importance of age as a predictor of atrial fibrillation and flutter after coronary artery bypass grafting. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1990;3:338–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paone G, Higgins RSD, Havstad SL, et al. Does age limit the effectiveness of clinical pathways after coronary artery bypass graft surgery? Circulation. 1998;98:41II–45II. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Willems S, Weiss C, Meinertz T. Tachyarrhythmias following coronary artery bypass surgery: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and current therapeutic strategies. Thorac Cardiovasc Surgeon. 1997;45:232–237. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1013733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zenati M, Domit TM, Saul M, et al. Resource utilization for minimally invasive direct and standard coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63S:84– 87. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)00324-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yount RJ, Vries JK, Councill CD. The Medical Archival Retrieval system: An information retrieval system based on distributed parallel processing. Inform Process Manag. 1991;27:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dimmer C, Jordaens L, Gorgov N, et al. Analysis of the P wave with signal averaging to assess the risk of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass surgery. Cardiology. 1998;89:19–24. doi: 10.1159/000006738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grandjean JG, Voors AA, Boonstra PW, et al. Exclusive use of arterial grafts in coronary artery bypass operations for three-vessel disease: Use of both thoracic arteries and gastroepiploic artery in 256 consecutive patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;112:935–994. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(96)70093-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mendes LA, Connelly GP, McKenney PA, et al. Right coronary artery stenosis: An independent predictor of atrial fibrillation after CABG. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25:198–202. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00329-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ott RA, Gutfinger DE, Miller MP, et al. Rapid recovery after coronary artery bypass grafting: Is the elderly patient eligible? Ann Thor Surg. 1997;63:634– 639. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(96)01098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parikka H, Toivonen L, Heikkila K, et al. Comparison of sotolol and metoprolol in the prevention of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass surgery. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1998;31:67–73. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199801000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pehkonen EJ, Makynen PJ, Kataja MJ, et al. Atrial fibrillation after blood and crystalloid cardioplegia in CABG patients. Thorac Cardiovasc Surgeon. 1995;43:200–203. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1013209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zaman AG, Alamgir F, Richens T, et al. The role of signal averaged P-wave and serum magnesium as a combined predictor of atrial fibrillation after elective coronary artery bypass surgery. Heart. 1997;77:527–531. doi: 10.1136/hrt.77.6.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arom KV, Emery RW, Petersen RJ, et al. Evaluation of 7,000 patients with two different routes of cardioplegia. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63:1619–1624. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)00359-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gill IS, FitzGibbon G, Higginson LA, et al. Minimally invasive coronary artery bypass: A series with early qualitative angiographic follow-up. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;64:710–714. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)00756-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steinberg JS, Zelenkofske S, Wong SC, et al. Value of the P-wave signal averaged ECG for predicting atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. Circulation. 1993;88:2618–2622. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.6.2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Subramanian VA, McCabe J, Geller C. Minimally invasive direct coronary artery bypass grafting: Two-year clinical experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;64:1648–1655. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)01099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tamis JE, Vloka ME, Mahotra S, et al. Atrial fibrillation is common after minimally invasive direct coronary artery bypass surgery. Abstr J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31(Suppl):118A. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cohn WE, Sirois CA, Johnson RG. Atrial fibrillation after minimally invasive coronary artery bypass grafting: A retrospective matched study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;117:298–301. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(99)70426-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Braithwaite D, Weissman C. The new onset of atrial arrhythmias following major noncardiothoracic surgery is associated with increased mortality. Chest. 1998;114:462– 468. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.2.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klein M, Evans SJ, Blumberg S, et al. Use of P-wave signal-averaged electrocardiogram to predict atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass surgery. Am Heart J. 1995;129:895–901. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(95)90109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stafford PJ, Kolkevar S, Cooper J, et al. Signal averaged P wave compared with standard electrocardiography or echocardiography for prediction of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting. Heart. 1997;77:417– 422. doi: 10.1136/hrt.77.5.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vaziri SM, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, et al. Imaging: Echocardiographic predictors of nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation: The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1994;89:724–730. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.2.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DeJong MJ, Gonce Morton P. Predictors of atrial dysrhythmias for patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. Am J Crit Care. 2000;9:388–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klemperer JD, Klein IL, Ojamaa K, et al. Triiodothyronine therapy lowers the incidence of atrial fibrillation after cardiac operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;61:1323–1329. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(96)00102-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Borzak S, Tisdale JE, Amin NB, et al. Atrial fibrillation after bypass surgery: Does the arrhythmia or the characteristics of the patient prolong hospital stay? Chest. 1998;113:1489–1491. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.6.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]