Abstract

Armillaria mellea is a major plant pathogen. Yet, no large-scale “-omics” data are available to enable new studies, and limited experimental models are available to investigate basidiomycete pathogenicity. Here we reveal that the A. mellea genome comprises 58.35 Mb, contains 14473 gene models, of average length 1575 bp (4.72 introns/gene). Tandem mass spectrometry identified 921 mycelial (n = 629 unique) and secreted (n = 183 unique) proteins. Almost 100 mycelial proteins were either species-specific or previously unidentified at the protein level. A number of proteins (n = 111) was detected in both mycelia and culture supernatant extracts. Signal sequence occurrence was 4-fold greater for secreted (50.2%) compared to mycelial (12%) proteins. Analyses revealed a rich reservoir of carbohydrate degrading enzymes, laccases, and lignin peroxidases in the A. mellea proteome, reminiscent of both basidiomycete and ascomycete glycodegradative arsenals. We discovered that A. mellea exhibits a specific killing effect against Candida albicans during coculture. Proteomic investigation of this interaction revealed the unique expression of defensive and potentially offensive A. mellea proteins (n = 30). Overall, our data reveal new insights into the origin of basidiomycete virulence and we present a new model system for further studies aimed at deciphering fungal pathogenic mechanisms.

Keywords: Armillaria mellea, basidiomycete proteomics, basidiomycete genomics, Next Generation Sequencing, fungal proteomics, glycosidases, Candida

Introduction

Basidiomycete fungi are attracting increased interest because of their plant pathogenic properties, along with an ability to produce enzymes, in particular glycoside hydrolases, which can degrade recalcitrant carbon sources, thereby increasing the range of substrates available for bioethanol production.1 Although the genomes of a number of basidiomycete species have been sequenced and a number of proteomic studies have been carried out, one genera in particular, Armillaria, has received little attention to date.2−4 Yet, Armillaria spp. are among the most serious plant root pathogens and cause major economic losses following infection of tree species of both agronomic importance and those grown for timber production purposes.5 The genera consists of at least 40 species, including A. mellea, A. gallica, A. tabescens, and A. borealis, with the former species attracting the most attention.

In particular, A. mellea has been studied because of its virulence, bioluminescent properties, ability to produce unusual natural products and from a strain typing perspective, for definitive identification of the Armillaria spp. responsible for timber crop infection.6 Recently, a novel infection model system for A. mellea has been established which deployed confocal microscopy and quantitative PCR for the estimation of fungal biomass produced during grape rootstock infection.7 This approach has facilitated a more quantitative assessment of fungal infection of plant roots, in addition to distinguishing between susceptible and resistant plant varieties. Armillaria spp. also produce uncommon secondary metabolites, such as sesquiterpene aryl esters, diketopiperzines and sphingolipids.8,9 Recent work has begun to explore the biomedical application of such metabolites.9

Next generation sequencing has dramatically accelerated research into basidiomycete genomics, for example the genomes of over 50 basidiomycetes are currently available, including the maize and teosinte pathogen Ustilago maydis,2 the ectomycorrhizal fungus, Laccaria bicolor,3 white rots (Phanerochaete chrysosporium10 and Schizophyllum commune(11)) and the multicellular species Coprinopsis cinerea.12

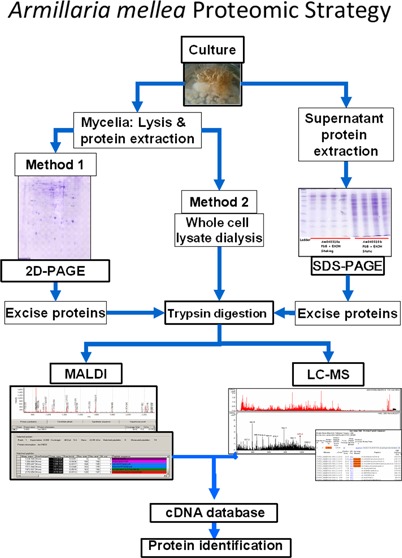

In initial basidiomycete proteomics studies,13 2-D PAGE coupled with MALDI-ToF or LC–MS/MS led to identification of 25 extracellular proteins from P. chrysosporium, mainly those involved in carbohydrate polymer degradation, and noted difficulties with peptide identification caused by protein glycosylation. Soon after, these techniques were used to assess the effects of vanillin, an intermediate in lignin degradation on the same fungus and revealed up- and down-regulation of the citric acid and glyoxylate cycles, respectively.14,15 A proteomic approach was also used to investigate the differential secretome composition of P. chrysosporium grown under ligninolytic conditions, where peroxidases were mainly detected. A greater diversity of fungal glycoside hydrolases was identified during culture in biopulped material including cellulases, hemicellulases, putative glucan 1,3-β-glucosidases and α-glycosidases. This work, which was the first differential secretome characterization of P. chrysosporium, highlighted the power of high-throughput proteomic analysis to reveal culture-dependent proteome remodelling due to substrates used for fungal culture. Although no genome sequences are available,16 proteomic analyses were also carried out on two economically important edible basidiomycetes, Sparassis crispa and Hericium erinaceum, yielding identification of 77 and 121 proteins from both species, respectively, 21 of which were found to be common in both species. L. bicolor is an ectomycorrhizal basidiomycete, which exists in either a saprotrophic phase in soil or an extended mutualistic interaction with tree roots.17 A recent proteomic study of the L. bicolor secretome in liquid culture identified 224 proteins by a combined electrophoretic fractionation and mass spectrometry-based shotgun approach.18 This work significantly extended knowledge of the secretome of this saprophytic organism and identified multiple glycoside hydrolases and proteases, hypothesized to be involved in either plant colonisation or basidiomycete defense. Of interest, among proteins of unknown function, an induced small secreted protein, probably a putative effector, has been detected.18 Functional assignment of unknown proteins produced by basidomycetes is set to become one of the major challenges in fungal biology in the coming years.

However, despite such advances in other basidiomycete species, to date, only 16 distinct A. mellea proteins are curated in GenBank including an ATP synthase subunit 6, GAPDH isoform, putative zinc finger/binuclear cluster transcriptional regulator, RNA polymerase (two subunits), a laccase-like multicopper oxidase Lcc2 and a metalloendopeptidase. This is especially problematic since so little is known at the molecular level about this plant pathogen.19 Here, we reveal the first extensive genome sequence analysis of A. mellea, combined with a detailed proteomic characterization. In addition, we propose a novel infection model system that utilizes Candida albicans as a target to investigate A. mellea virulence.

Experimental Procedures

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. Ltd. (U.K.), unless otherwise stated.

Fungal Culture

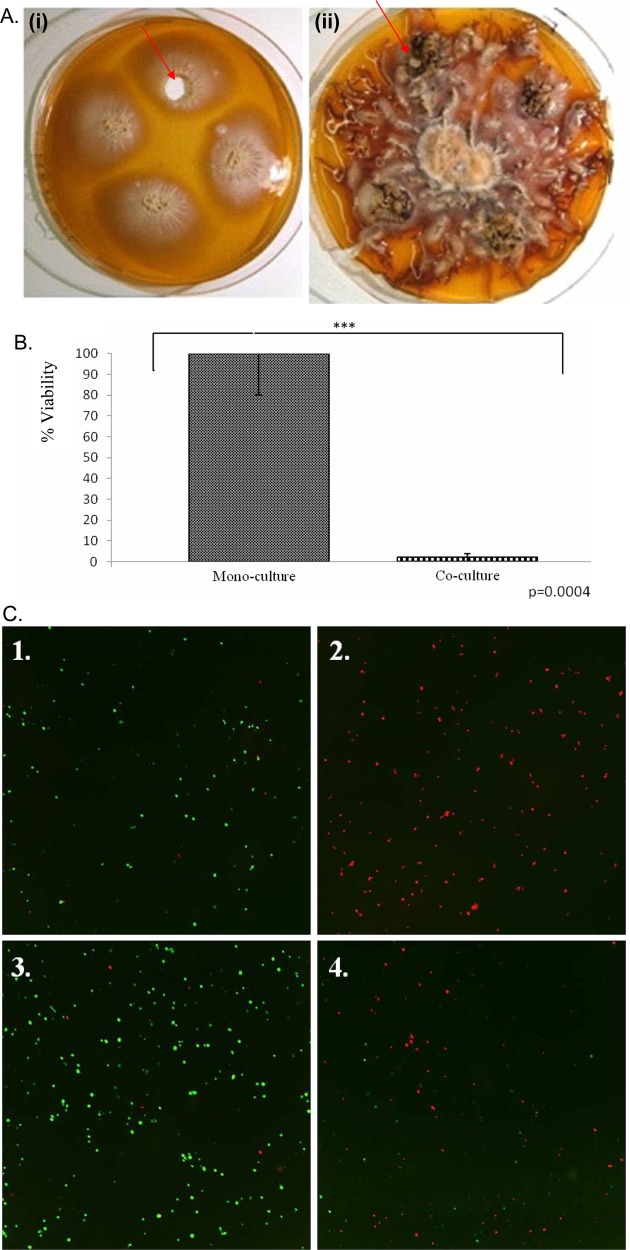

A. mellea (Vahl:Fr) Kummer DSM 3731 was purchased from DSMZ (Braunschweig, Germany) and maintained on malt extract agar (50 g/L) (Oxoid CM0059). Liquid cultures (200 mL) were undertaken in 500 mL Erlenmeyer flasks using potato dextrose broth (PDB) (2.4% (w/v)) or minimal media (5 mM ammonium tartarate as nitrogen-source, trace elements according to Schrettl and colleagues20 and containing 1% (w/v) of one of the following carbon-sources: lignin, xylan, cellulose, rutin, yeast extract). Ethanol (0.15% (v/v)) was added to liquid cultures before inoculation with mycelia and incubation at 25 °C in darkness for 2–6 weeks. Mycelia from liquid cultures were harvested by filtration through miracloth, washed with distilled water, dried thoroughly with absorbent paper, and put immediately into liquid nitrogen and stored at −70 °C. Culture supernatants were stored at −20 °C. Malt extract agar (MEA) plates were inoculated with A. mellea mycelia and incubated at 25 °C in darkness for 2–6 weeks. Plates were wrapped in parafilm and stored at 4 °C. Coculture experiments involving A. mellea and Candida albicans were carried out on PDB agar. C. albicans (5 μL; 108 cells/mL) was applied in quadruplicate around central mycelial cultures of A. mellea. After 52 days coculture, C. albicans plugs were collected for subsequent growth (via reculture on PDB agar) and viability assessment (via fluorescein diacetate (FDA)21), in the absence of A. mellea. Briefly, FDA (2 μg/100 μL) and propidium iodide (PI: 0.6 μg/30 μL) were added to 2 × 108C. albicans cells for 30 min in the dark. After sequential washing with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and 20% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS, fluorescence was determined using an Olympus Fluoview 1000 confocal microscope. Viability was also assessed by replating serial dilutions of monoculture and coculture-derived C. albicans on MEA. Proteins of A. mellea produced during coculture were extracted by gently grinding mycelia and agar (25 mL) to avoid mycelial lysis with 50 mM KH2PO4 pH 7.0. After overnight agitation and filtration, proteins were TCA precipitated, resolubilized in 50 μL of 10 mM ammonium hydrogen carbonate containing 10% (v/v) acetonitrile and trypsin (65 ng/mL) and digested (37 °C) overnight. Resultant peptides were diluted 1/4 in 0.1% (v/v) formic acid (20 μL) and analyzed directly by LC–MS/MS.

DNA Isolation

A. mellea DNA was extracted using a ZR Fungal/Bacterial DNA Kit (Zymo Research Group) using a modified protocol. Mycelia were ground into a fine powder in liquid N2, and 300 mg were added to tubes containing glass beads (200 mg, 0.4 mm). Lysis solution (750 μL) was added, specimens were bead-beaten for 2 min at 20 Hz followed by centrifugation at 10000× g for 1 min. Supernatants (400 μL) were transferred to Zymo-Spin IV Spin Filters and the manufacturer’s instructions were then followed. DNA was precipitated by adding 3 M sodium acetate (1/10 vol.) and 3 vol. ice-cold ethanol (100% (v/v)). Following incubation at −20 °C for 3 h, specimens were centrifuged at 13000× g for 10 min and supernatants removed. Pellets were washed again with ice-cold ethanol (75% (v/v); 180 μL) followed by centrifugation at 13000× g for 10 min. After supernatant removal, pellets were air-dried to remove traces of ethanol before resuspending in Milli-Q H2O (20 μL). PCR to confirm A. mellea DNA presence was carried out using two different primer pairs; RegF1 and RegR1 primers and AMEL3 and ITS4 primers.22,23 PCR products were separated on 1% (w/v) agarose gel.

Genome Sequencing, Assembly and Annotation

A single no-PCR paired-end library was generated from A. mellea genomic DNA according to the method of Kozareva and Turner24 with an estimated fragment size of 168 ± 92 bp (inferred by remapping the reads onto the assembly with Maq software25). The library was sequenced on three lanes of an Illumina GAII at 76 bp read length26 producing a total of 6.72 Gb Q20 bases. The reads were assembled with Velvet v0.7.5327 with a kmer of 53 bp. The raw sequence data have been submitted to the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA: http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/) under accession: ERP000894. Gene models were predicted using the ab initio gene finder Augustus.28 Based on a close phylogenetic relationship, L. bicolor was chosen as an appropriate training sequence (Figure 1). A preliminary annotation of predicted gene models was performed using Blast2GO.29 Blast2GO was also used to assign gene ontology (GO)30 terms to all gene models. Signal secretion peptides were predicted using SignalP ver3.0.31 Proteins that may be secreted via the nonclassical secretion pathway were located using the SecretomeP 2.0 server. A. mellea multigene families were located by performing an “all against all” BlastP database search32 and the resulting hits were clustered into families using the mcl algorithm33 with an inflation value of 2.

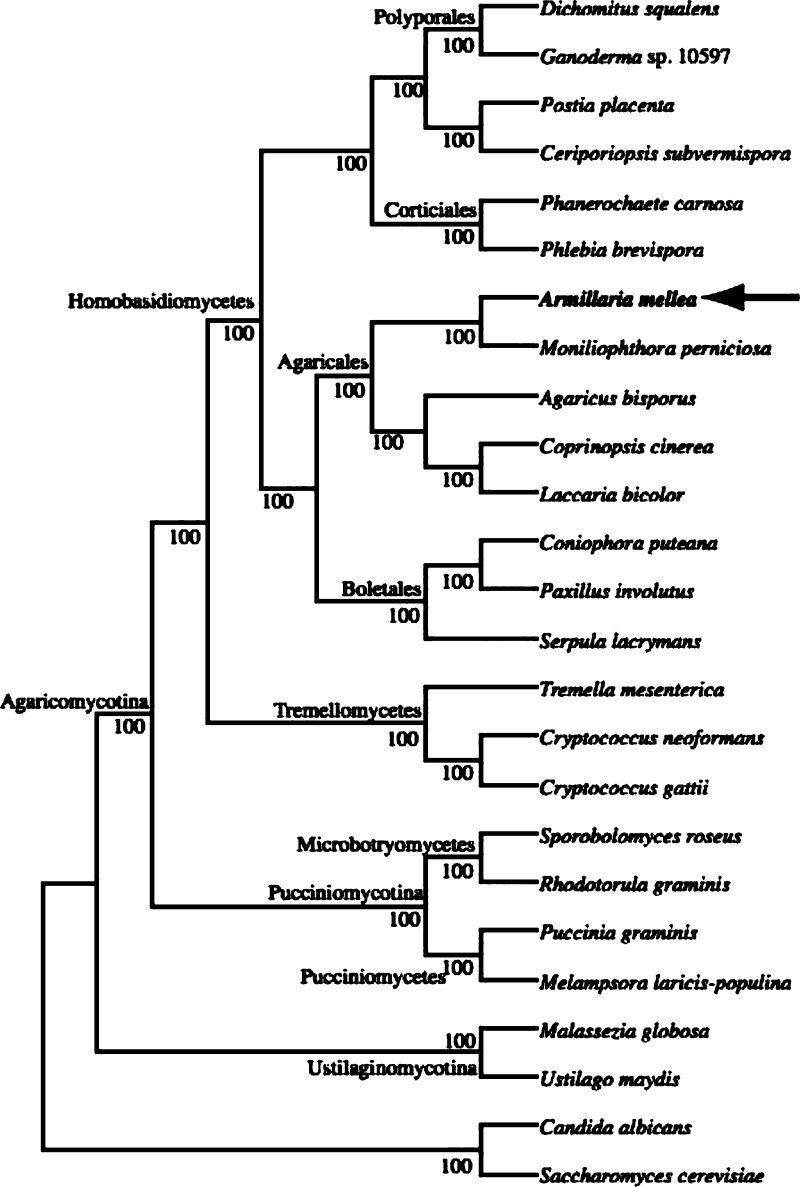

Figure 1.

Basidiomycete phylogenetic supertree: Supertree is derived from 5936 individual gene families. Basidiomycotina subphyla, class and orders are shown where applicable. Numbers along branches represent bootstrap support values. Two ascomycete species (Candida albicans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae) were chosen as outgroups.

The initial genome assembly and predicted protein coding genes are available at http://www.armillariamellea.com.

Phylogenetic Supertree Construction

Our representative genome species tree consisted of 23 Basidiomycete species and 2 Ascomycete outgroups (Supplementary Table 1, Supporting Information). Genome data was obtained from the relevant sequencing centers (Supplementary Table 1, Supporting Information). In total, 8860 homologous gene families (containing 4 or more genes) were identified using a previously described randomized BlastP approach.34,35 Gene families were aligned using the multiple sequence alignment software Muscle v3.736 with the default settings. Misaligned or fast evolving regions of alignments were removed with Gblocks.37 Permutation tail probability (PTP) tests38,39 were performed on each alignment to ensure that the presence of evolutionary signal was better than random (p < 0.05). We found that 2924 gene families failed the PTP test, these were removed, leaving a data set of 5936 gene families. Optimum models of protein evolution were selected using Modelgenerator40 and these were used to reconstruct maximum likelihood phylogenies in Phyml v3.0.41 Bootstrap resampling was performed 100 times on each alignment and majority rule consensus (threshold of 50%) trees were reconstructed. Gene families were used to reconstruct supertrees using gene tree parsimony42,43 implemented in the software DupTree version 1.48.44

Protein Extraction

Mycelial protein extraction was carried out at 4 °C using two different methods. For 2-D PAGE, mycelia were ground in liquid N2 and 1 g resuspended in 6 mL 10% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid (TCA) (4 °C) and sonicated six times (Bandelin Senoplus HD2200 sonicator, Cycle 6, 10 s, Power 10%). Samples were then centrifuged at 20200× g for 10 min (4 °C), followed by washing in ice cold acetone, twice. Pellets were finally resuspended in IEF buffer (10 mM Tris, 8 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 4% (w/v) CHAPS, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 65 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and 0.8% (w/v) IPG buffer), centrifuged at 14000× g for 5 min (4 °C) and supernatants used for further analysis. Proteins were quantified using the Bradford assay and 300 μg were used for IEF using 13 cm strips (pH range 3–10; IPGphorII; GE Healthcare) (Step: 50 V × 12 h; Step: 250 V × 0.25 h; Gradient to 5000 V × 2 h; Step: 5000 V × 5 h; Gradient to 8000 V × 2 h; Step: 8000 V × 1 h) followed by SDS-PAGE separation (60 V, 30 min; 120 V, 1.5 h) on PROTEAN Plus Dodeca Cell (Bio-Rad) and Colloidal Coomassie Blue staining. For shotgun analysis, 1 g of mycelial powder was resuspended in 6 mL of 25 mM Tris-HCl, 6 M Guanidine-HCL, 10 mM DTT, pH 8.6 and sonicated five times to generate whole cell lysates. Samples were centrifuged at 20200× g for 10 min (4 °C). DTT (1 M; 10 μL/mL lysate) was added to supernatants and incubated at 56 °C for 30 min. Samples were cooled to room temperature and 55 μL of 1 M iodoacetamide per milliliter of lysate was added followed by incubation (in the dark) for 20 min. Samples were then dialyzed twice against cold 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate, (2 × 50 vol.), for at least 3 h with stirring. Precipitates of denatured protein were present after dialysis. One-hundred microliters of denatured protein solution was transferred to an Eppendorf tube and 5 μL trypsin (Promega V5111) (0.4 μg/μL in 10% (v/v) acetonitrile in 10 mM ammonium bicarbonate) was added. After overnight incubation at 37 °C, the protein precipitates disappeared and protein digests were spin filtered (Agilent Technologies, 0.22 μm cellulose acetate) prior to LC–MS/MS analysis.

For extracellular protein isolation, a modified version of that described by Fragner et al.45 was used. Culture supernatants (40 mL) were frozen −20 °C, thawed, centrifuged at 48000× g for 40 min, transferred to clean tubes and frozen in liquid N2. Samples were lyophilized to 4 mL, brought to 10% (w/v) TCA and centrifuged 10000× g for 5 min before washing with ice cold acetone (3 times) with centrifugation steps of 10000× g for 5 min. Protein pellets were solubilized with 100 μL of 10% (w/v) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 0.1 M DTT and 5 μL of SDS-PAGE solubilization buffer and boiled for 10 min prior to SDS-PAGE. For protein extraction of fungal cultures grown on solid phase, MEA plates (25 mL) were briefly ground with a pestle, transferred to containers and brought to 50 mL with 50 mM KH2PO4 pH 7.0.46 Samples were agitated overnight at 4 °C, after which liquid was removed by gravity filtration through Miracloth. Polysaccharides were removed by centrifugation at 48000× g for 30 min, and supernatants were precipitated with 10% (w/v) TCA under agitation overnight at 4 °C. Samples were centrifuged at 1700× g for 40 min, pellets were washed (3 times) with 20% (v/v) 50 mM Tris-HCl in ice cold acetone followed by washing in pure ice-cold acetone before air drying and storage −20 °C. Proteins were digested overnight at 37 °C with 50 μL of trypsin (65 ng/μL in 10% (v/v) acetonitrile in 10 mM ammonium bicarbonate). All samples were spin filtered prior to LC–MS/MS analysis.

In-gel digestions (SDS-PAGE bands and 2-D PAGE spots) were carried out according Shevchenko and colleagues with little modification.47 Spots were excised and destained with 10% (v/v) acetonitrile in 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate. Gel pieces were shrunk with 500 μL of acetonitrile and digested with 50 μL of trypsin (13 ng/μL) at 37 °C overnight before filtration and LC–MS/MS analysis.

LC–MS/MS, Spectral Analysis and Database Searching

An Agilent 6340 ion trap mass spectrometer running ChemStation 0.01.03-SR2 (204) and a ProtiID-Chip150 C18 150 mm (G4240–62006) chip was used for peptide separation from in-gel protein digests, while a 160 nL 150 mm C18 chip (G4240–62010) was used for tryptic peptides prepared by total protein digestion. Solvent A: 0.1% (v/v) formic acid in water and Solvent B: 0.1% (v/v) formic acid in 90% (v/v) acetonitrile / 10% (v/v) water. For protein identification following SDS- or 2-D PAGE, a flow rate of 0.6 μL/min with a linear gradient of 5 to 70% Solvent B over 7 min followed by 1 min increase to 100 % Solvent B for 1 min and decrease to 5% Solvent B for 1 min was deployed. For shotgun proteomic studies, a flow rate of 0.4 μL/min with non-linear acetonitrile/water + 0.1% (v/v) formic acid gradients, optimised on a sample-specific basis from initial chromatographic analyses, were used. For shotgun proteomic studies, a flow rate of 0.4 μL/min with a nonlinear acetonitrile/water +0.1% (v/v) formic acid gradient was optimized on a sample-specific basis from initial chromatographic analyses. Gradients ranging from 20 to 180 min were optimized for identification of the maximum number of proteins per sample: peptide identification from protein spots or bands required 20 min gradients, while shotgun (complex mixtures) gradients were generally up to 180 min duration.

All LC–MS spectra were analyzed using Spectrum Mill software (Rev A.03.03.084 SR4; Agilent Technologies) to identify proteins against the translated A. mellea cDNA database. MS/MS searches were carried out with the following settings: enzymatic trypsin digestion, carbamidomethylation as fixed modification and two variable modifications were set: deamination and oxidation of methionine. The minimum scored peak intensity was set to 70, with precursor mass tolerance ±2.5 Da and product mass tolerance ±0.7. The maximum ambiguous charge was set to 3 with a sequence tag length >3 and minimum detected peaks set to 4. Reversed database scores were calculated.

Results and Discussion

Genome Sequencing and Analysis

PCR confirmed the presence of A. mellea DNA (data not shown). The genome of A. mellea (Vahl:Fr) Kummer DSM 3731 was sequenced using an Illumina Genome Analyzer II. A total of 6.72 Gb of sequence data was obtained from 3 single read lanes. On the basis of nuclear DNA measurements by RFLP analysis,47 this represents 57.25-fold coverage of the A. mellea genome. Assembly of the Illumina reads with the Velvet assembler resulted in 58.35 Mb of sequence data in 4377 scaffolds with an N50 size of 36.7 kb (Table 1). The overall GC content of the genome is 49.1%, while in the coding regions it is 53.2%.

Table 1. Genome Assembly Statistics for A. mellea (Vahl:Fr) Kummer DSM 3731.

| scaffolds | contigs | |

|---|---|---|

| N50 | 36679 bp | 5485 bp |

| Largest | 639 705 bp | 154 911 bp |

| Count | 4377 | 15215 |

| Total Length | 58 358 340 bp | 71 738 977 bp |

A total of 14473 putative A. mellea open reading frames (ORFs) were predicted (Table 2) which was subsequently used as the reference database for proteomic analyses. The average gene length was found to be 1575 bp, similar to what is observed in close relatives of A. mellea, such as L. bicolor and Coprinopsis cinerea (Figure 1 and Table 2). The average exon/intron lengths were also comparable among these species, as were the average number of introns per gene (4.72, 4.44 and 4.66, respectively). Blast2GO successfully assigned a GO term to 9514 (65.7%) of the predicted genes (data not shown). The SignalP webserver identified 1903 proteins with secretion signal peptides, while Phobius predicted 4035 proteins (27.8%) with membrane regions, 2746 (19%) with transmembrane regions and 246 with transmembrane regions plus signal peptide regions. Protein GRAVY48 identified 448 proteins with a GRAVY Score >0.5.

Table 2. Gene Statistics for A. mellea (Vahl:Fr) Kummer DSM 3731 in Comparison to Closely-related Basidiomycete Species.

| A. mellea | L. bicolor | Coprinopsis cinerea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Assembly (Mb) | 58.3 | 64.9 | 37.5 |

| Number of protein-coding genes | 14473 | 20614 | 13544 |

| Coding sequence <300 bp | 957 | 2191 | 838 |

| Average gene length (bp) | 1575 | 1533 | 1679 |

| Average coding sequence length (bp) | 1227.75 | 1134 | 1352 |

| Average exon length | 217.52 | 210.1 | 251 |

| Average intron length | 73.62 | 92.7 | 75 |

| Average number of introns per gene | 4.72 | 4.44 | 4.66 |

Homology searches followed by Markovian clustering inferred that 9939 (68.7%) of the A. mellea ORFs belonged to multigene families. Using the same approach we calculated that 68.5% of L. bicolor genes belong to multigene families. Approximately 18.8% (2721) of the predicted A. mellea genes have no significant homologues in the NCBI database, a figure consistent with other newly sequenced basidiomycete genomes. We also successfully located 240 tRNA genes which compares favorably to L. bicolor which has 297 tRNA genes.3

Protein Identification

Given the paucity of A. mellea proteins curated and present in GenBank (n = 16), it was necessary to interrogate the translated version of the A. mellea cDNA database with peptide sequence data for complete and accurate de novo protein identification. As a consequence, a total of 921 proteins were identified in both mycelia and culture supernatants from A. mellea grown under a range of different culture conditions. These identifications were based on the detection of 3641 unique peptides, 2839 of which came from mycelia and 802 from the supernatant, respectively, with 197 common to both (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3, Supporting Information).

Mycelial Proteins

Mycelial proteins (n = 739) were identified by using the A. mellea database obtained from the translation of the protein-coding genes. Six-hundred twenty-nine proteins were uniquely identified in mycelia (Supplementary Table 2, Supporting Information), while others were also identified in the A. mellea secretome (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4, Supporting Information). Of the mycelia-specific proteins, 509 were uniquely identified by a shotgun approach, with 98 and 9 proteins identified following prior 2-D PAGE and SDS-PAGE fractionation, respectively (Supplementary Figure 1, Supporting Information). Supplementary Table 2, Supporting Information, shows the actual peptide sequence with corresponding Spectrum Mill scores where values >11 were deemed significant according to manufacturer’s guidelines. Sequence coverage ranged from 1 to 5%, 1 to 81% and 1 to 72%, respectively, using SDS-PAGE, 2-D PAGE fractionation and shotgun analysis.

Functional analysis undertaken with BLAST2GO and database searches classified proteins according to the biological process (BP) in which they are involved, the molecular function (MF) and the cellular component (CC). GO analysis by BP of mycelial proteins generated 18 categories. The largest categories were catabolic processes (n = 114) followed by translation (n = 88), carbohydrate metabolic processes (n = 81), precursor metabolites and energy (n = 56), response to stress (n = 22) and secondary metabolic processes (n = 19) (Figure 2a). MF of mycelial proteins revealed nucleotide binding (n = 150) and structural molecule activity (n = 70) as the largest categories, accounting for 53% of mycelial proteins identified. GO identified 38 proteins in MF as having peptidase activity (Figure 2b). Mycelial proteins CC mainly comprised ribosomal proteins (n = 78) and protein complexes (n = 77). There were also 23 proteins classified as mitochondrial (Figure 2c) and 14 proteins that have not been previously annotated and appear to be unique to A. mellea. One-hundred two proteins were detected that were previously reported as hypothetical or predicted (Table 3). As expression of these proteins is now demonstrated, they can be reclassified as Unknown Function Proteins. A search of these proteins against the InterPro database49 suggested putative functions. Overall, 114 known domains were assigned to 55 proteins (Table 3). Eight proteins (Am15909, Am6889, Am18190, Am14843, Am14848, Am14568, Am13925 and Am17640) were found to contain a NAD(P)+-binding domain, however no other domain was over-represented in our analysis. Moreover, no GO function was identifiable for 73 proteins, while 26 showed no BLAST description. Among these are proteins with conserved domains which indicate a putative process, function or cellular location such as Am12246 containing a START domain typical of proteins which transport ubiquinone during respiration or Am14390 containing a 60 residue conserved BSD domain of unknown function usually located in BTF2-like transcription factors, Synapse-associated proteins and DOS2-like.50

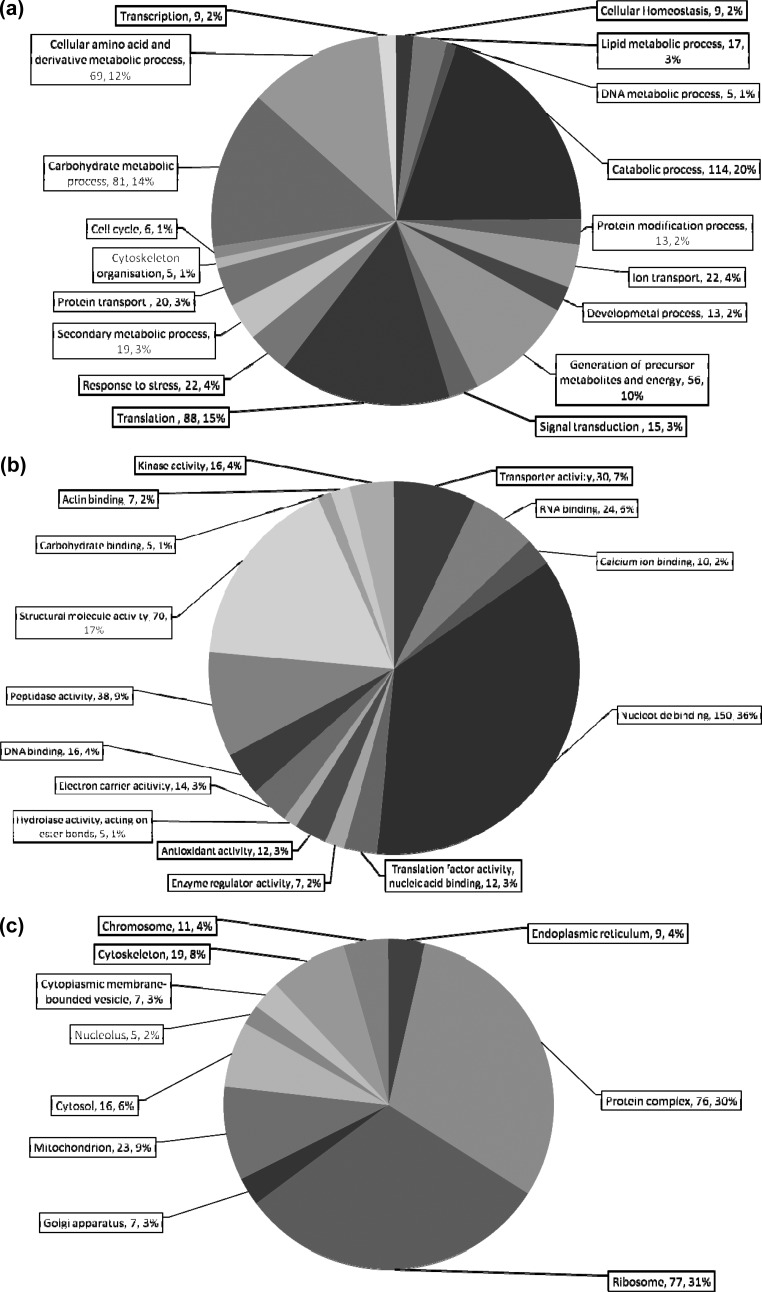

Figure 2.

Blast2Go annotation of mycelial protein classification: (a) biological process; (b) molecular function; (c) cellular component. The total number of proteins in each category, as well as the overall %, are given for each subdivision (No., %).

Table 3. Unique, Previously Hypothetical and Predicted Proteins from A. mellea Mycelia and Secretome.

| accession no.a | InterPro domainsb | tMrc | tpId | coverage (%) | unique peptides | SM scoree | GRAVY scoref | TMg | SigP/SecPh | Methodi | Sourcej |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Am18468 | Six-bladed beta-propeller, TolB-like | 52294.9 | 4.19 | 36 | 10 | 162.51 | –0.272 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am8114 | None detected | 20938.8 | 7.77 | 31 | 4 | 77.92 | –0.278 | SecP | 2D | M, SN | |

| Am8753 | Macrophage migration inhibitory factor; Tautomerase | 20131.3 | 5.1 | 15 | 2 | 32.87 | –0.053 | SecP | S | M | |

| Am14766 | Glucose-methanol-choline oxidoreductase, N-terminal; Protein of unknown function DUF427 | 83438.2 | 6.5 | 1 | 1 | 16.04 | –0.295 | 1D | SN | ||

| Am16713 | Monooxygenase, FAD-binding; Aromatic-ring hydroxylase-like; Thioredoxin-like fold | 60524.2 | 6.17 | 33 | 14 | 247 | –0.184 | SigP | 2D | M | |

| Am11784 | RNA recognition motif domain; Aldo/keto reductase; Nucleotide-binding, alpha-beta plait; RNA-binding motif | 25961.1 | 6.36 | 44 | 9 | 151.55 | –0.458 | 2D | M | ||

| Am14065 | Globin, structural domain | 24081.8 | 5.9 | 17 | 3 | 61.66 | –0.128 | SecP | S | M, SN | |

| Am6826 | None detected | 6811.8 | 9.52 | 24 | 1 | 19.01 | –0.138 | SecP | S | M | |

| Am11329 | None detected | 38549.9 | 5.64 | 23 | 4 | 74.13 | 0.032 | SecP | 1D | M, SN | |

| Am15909 | 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, NADP-binding; 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, C-terminal-like; Dehydrogenase, multihelical; Hydroxy monocarboxylic acid anion dehydrogenase, HIBADH-type; NAD(P)-binding domain | 39265 | 6.83 | 31 | 7 | 138.16 | –0.089 | 1 | SecP | 2D | M |

| Am19857 | PLC-like phosphodiesterase, TIM beta/alpha-barrel domain | 33320.7 | 4.36 | 4 | 1 | 20.33 | 0.081 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am11737 | None detected | 31480.1 | 9.19 | 15 | 4 | 65.72 | –0.316 | S | M | ||

| Am10761 | None detected | 104910 | 5.02 | 4 | 2 | 36.1 | –0.605 | S | M | ||

| Am6759 | None detected | 9075.6 | 10.89 | 19 | 1 | 17.65 | –0.064 | SecP | S | M | |

| Am687 | None detected | 31486.3 | 4.74 | 42 | 8 | 153.64 | –0.773 | SecP | 2D | M | |

| Am12929 | Phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein PEBP | 25186.2 | 6.02 | 13 | 2 | 37.32 | 0.35 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am15856 | Thioredoxin-like fold | 29393.2 | 5.89 | 8 | 1 | 11.6 | –0.132 | SigP | S | M | |

| Am10869 | None detected | 29854.2 | 4.44 | 9 | 1 | 17.66 | 0.217 | 1 | SigP | 1D | SN |

| Am7778 | Lambda repressor-like, DNA-binding domain | 7398.4 | 6.7 | 22 | 1 | 22.18 | –0.027 | SecP | S | M | |

| Am13799 | HAD-superfamily hydrolase, subfamily IA, variant 3; Phosphoglycolate phosphatase, domain 2; HAD-like domain | 36474.5 | 5.58 | 7 | 1 | 14.84 | –0.364 | SecP | S | M | |

| Am18955 | Beta-lactamase-like | 37813.3 | 5.59 | 3 | 1 | 12.65 | –0.164 | SecP | 2D | M | |

| Am11484 | None detected | 13748.5 | 4.85 | 13 | 1 | 16.43 | –0.687 | SecP | 1D | SN | |

| Am19019 | Carboxylesterase, type B; Carboxylesterase type B, conserved site | 61132.2 | 4.65 | 10 | 4 | 63.48 | –0.097 | SigP | 1D | M, SN | |

| Am17323 | None detected | 6874.9 | 6.18 | 19 | 1 | 19.82 | 0.077 | SecP | S | M | |

| Am11327 | None detected | 33136.6 | 4.5 | 11 | 3 | 51.17 | –0.01 | SecP | 1D | SN | |

| Am18523 | Vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 62 | 40908 | 4.45 | 3 | 1 | 17.86 | –0.258 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am16822 | None detected | 310055 | 4.05 | <1 | 1 | 13.54 | –0.318 | SecP | S | M | |

| Am16119 | Crotonase, core; Armadillo-like helical | 105164 | 5.71 | 2 | 1 | 21.12 | –0.037 | 2 | S | M | |

| Am15204 | None detected | 20487.3 | 4.95 | 13 | 1 | 23.43 | –0.319 | SecP | 1D | M, SN | |

| Am9185 | None detected | 61991 | 5.67 | 2 | 1 | 17.45 | –0.08 | SecP | 2D | M | |

| Am10375 | Six-hairpin glycosidase-like; Protein of unknown function DUF1680 | 67815.8 | 5.1 | 2 | 1 | 11.46 | –0.156 | SecP | 1D | SN | |

| Am13156 | None detected | 72243.6 | 4.96 | 25 | 10 | 177.07 | –0.065 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am6889 | Short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase SDR; Glucose/ribitol dehydrogenase; NAD(P)-binding domain; Short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase, conserved site | 26913 | 6.52 | 51 | 9 | 163.3 | 0.145 | SecP | S | M | |

| Am10376 | FAD dependent oxidoreductase; Lanthionine synthetase C-like | 158913 | 5.63 | 2 | 2 | 24.79 | –0.143 | SecP | 1D | SN | |

| Am9103 | None detected | 9374.6 | 9.15 | 43 | 2 | 39.82 | –0.38 | SecP | 2D | M | |

| Am6752 | NADH:flavin oxidoreductase/NADH oxidase, N-terminal; Aldolase-type TIM barrel | 39576 | 6.03 | 4 | 1 | 22.1 | –0.322 | 1D | SN | ||

| Am1857 | PLC-like phosphodiesterase, TIM beta/alpha-barrel domain | 29991.3 | 4.21 | 5 | 1 | 22.58 | –0.069 | 1 | SecP | 1D | SN |

| Am16247 | NADH:flavin oxidoreductase/NADH oxidase, N-terminal; Aldolase-type TIM barrel | 58857 | 5.18 | 2 | 1 | 17.2 | –0.358 | 1D | SN | ||

| Am17436 | Cytochrome cd1-nitrite reductase-like, C-terminal haem d1; WD40/YVTN repeat-like-containing domain; Lactonase, 7-bladed beta propeller | 37242.1 | 5.24 | 6 | 1 | 15.1 | 0.071 | SecP | 1D | SN | |

| Am18980 | Peptidase M35, deuterolysin; Metallopeptidase, catalytic domain | 38034.5 | 4.34 | 3 | 1 | 18.3 | 0.093 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am17081 | Uncharacterised conserved protein UCP014753 | 71468.5 | 5.63 | 2 | 1 | 19.33 | –0.454 | SecP | S | M | |

| Am10194 | None detected | 25455 | 4.68 | 9 | 1 | 13.21 | –0.037 | SecP | 1D | SN | |

| Am19191 | ATPase inhibitor, IATP, mitochondria | 9917.3 | 9.85 | 35 | 2 | 36.86 | –0.816 | SecP | S | M | |

| Am15281 | Glycoside hydrolase, catalytic domain; Glycoside hydrolase, superfamily | 27023.3 | 4.74 | 17 | 2 | 42.8 | –0.072 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am18190 | NmrA-like; NAD(P)-binding domain | 32292.8 | 6.32 | 6 | 1 | 16.86 | –0.067 | SecP | S | M | |

| Am15588 | RNA recognition motif domain; Nucleotide-binding, alpha-beta plait | 35273.8 | 6.42 | 5 | 1 | 12.87 | –0.543 | SecP | S | M | |

| Am14868 | Hyaluronan/mRNA-binding protein | 15038.5 | 5.03 | 9 | 1 | 13.93 | –0.79 | SecP | S | M | |

| Am14843 | Short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase SDR; Glucose/ribitol dehydrogenase; NAD(P)-binding domain | 33921.3 | 8.86 | 3 | 1 | 16.98 | –0.197 | SecP | S | M | |

| Am14849 | Short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase SDR; Glucose/ribitol dehydrogenase; NAD(P)-binding domain | 34440.9 | 8.72 | 10 | 2 | 34.33 | –0.206 | SecP | S | M | |

| Am10047 | None detected | 17599.3 | 4.88 | 7 | 1 | 17.85 | –0.751 | 1 | S | M | |

| Am10878 | Peptidase S28 | 59821 | 5.19 | 2 | 1 | 19.36 | –0.176 | SigP | S | M, SN | |

| Am14568 | Semialdehyde dehydrogenase, NAD-binding; NAD(P)-binding domain | 8595.9 | 8.01 | 21 | 1 | 17.87 | –0.404 | SecP | S | M | |

| Am13925 | Alcohol dehydrogenase superfamily, zinc-type; GroES-like; Alcohol dehydrogenase, C-terminal; NAD(P)-binding domain; Polyketide synthase, enoylreductase | 30108.6 | 8.39 | 5 | 1 | 18.76 | –0.092 | SecP | S | M | |

| Am14730 | Lipase, class 3 | 31696.1 | 4.19 | 3 | 2 | 21.64 | –0.131 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am13263 | PI31 proteasome regulator; Proteasome Inhibitor PI31 | 61669.9 | 4.8 | 3 | 1 | 18.94 | –0.684 | S | M | ||

| Am11030 | None detected | 11862 | 4.78 | 12 | 1 | 16.25 | –1.312 | S | M | ||

| Am11032 | None detected | 14406.4 | 4.46 | 24 | 2 | 34.06 | 0.319 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am11414 | None detected | 43297.2 | 8.52 | 4 | 1 | 14.26 | –0.341 | SecP | 1D | SN | |

| Am13172 | Peptidase S28 | 45328.5 | 5.6 | 24 | 8 | 135.18 | –0.277 | 2 | S | M | |

| Am13545 | Histidine phosphatase superfamily, clade-2 | 17335.5 | 4.84 | 8 | 1 | 16.49 | –0.354 | SecP | 1D | SN | |

| Am13609 | None detected | 11998.7 | 9.16 | 13 | 1 | 19 | –0.617 | SecP | S | M | |

| Am13611 | None detected | 19307.7 | 4.48 | 10 | 2 | 27.62 | –0.273 | SigP | 1D | M, SN | |

| Am14542 | Alpha/beta hydrolase fold-1; Peptidase S33 tripeptidyl aminopeptidase-like, C-terminal | 45979.8 | 5.02 | 4 | 1 | 12.46 | –0.603 | 1 | SigP | S | M |

| Am17640 | NAD(P)-binding domain | 15273.3 | 3.58 | 9 | 1 | 11.87 | –1.65 | SecP | S | M | |

| Am1874 | O-methyltransferase, family 2; Winged helix-turn-helix transcription repressor DNA-binding | 33850.3 | 5.69 | 3 | 1 | 16.3 | –0.102 | SecP | 1D | SN | |

| Am199 | Cell wall beta-glucan synthesis | 91085.6 | 5.66 | 2 | 1 | 13.7 | –0.384 | SecP | S | M | |

| Am20215 | Domain of unknown function DUF221; Protein of unknown function DUF3779, phosphate metabolism | 14158.6 | 9.34 | 10 | 1 | 15.89 | –0.053 | 1 | SecP | S | M |

| Am2320 | Ubiquitin-associated/translation elongation factor EF1B, N-terminal; UV excision repair protein Rad23; Heat shock chaperonin-binding; UBA-like; XPC-binding domain; Ubiquitin-associated/translation elongation factor EF1B, N-terminal, eukaryote; Protein of unknown function DUF3419 | 15229.2 | 4.62 | 56 | 6 | 110.44 | –0.483 | 2D | M, SN | ||

| Am5632 | None detected | 16183.3 | 5.1 | 23 | 3 | 48.67 | –0.519 | 1D | SN | ||

| Am5717 | ATPase, F0 complex, subunit E, mitochondrial | 6084.7 | 4.24 | 49 | 1 | 16.4 | –0.241 | SecP | S | M | |

| Am6758 | None detected | 11553.5 | 5.09 | 11 | 1 | 16.81 | 0.179 | S | M | ||

| Am691 | Alpha/beta hydrolase fold-1 | 14048.5 | 9.86 | 10 | 1 | 17.02 | –1.717 | S | M | ||

| Am9253 | None detected | 60512.9 | 5.18 | 3 | 1 | 13.85 | –0.452 | 1D | SN | ||

| Am15212 | None detected | 10126.8 | 9.03 | 20 | 1 | 23.84 | 0.139 | SecP | 1D, S | M | |

| Am10757 | Dimeric alpha-β barrel | 75431.3 | 6.39 | 2 | 1 | 11.13 | –0.723 | 2D | M | ||

| Am11132 | Glutathione S-transferase, N-terminal; Glutathione S-transferase, C-terminal; Glutathione S-transferase, omega-class; Glutathione S-transferase, C-terminal-like; Thioredoxin-like fold; Glutathione S-transferase/chloride channel, C-terminal | 22177.7 | 10.09 | 10 | 1 | 14.18 | –0.067 | 2 | 2D | M | |

| Am12286 | Ubiquitin; Ubiquitin conserved site; Ubiquitin supergroup; Ubiquitin subgroup | 57329.3 | 4.22 | 2 | 1 | 13.06 | –0.132 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am12502 | None detected | 60386.3 | 6.2 | 26 | 10 | 188.36 | –0.174 | 1 | 2D | M, SN | |

| Am13522 | None detected | 12745.6 | 7.54 | 10 | 1 | 16.59 | –0.495 | S | M | ||

| Am13594 | None detected | 73800.3 | 9.33 | 3 | 1 | 20.46 | –0.658 | S | M | ||

| Am14055 | Alpha/beta hydrolase fold-1; Peptidase S33 tripeptidyl aminopeptidase-like, C-terminal | 55061 | 4.49 | 1 | 1 | 14.07 | –0.051 | SecP | 1D | SN | |

| Am14569 | None detected | 30523.7 | 6.86 | 8 | 2 | 25.97 | –0.218 | 2D | M | ||

| Am14848 | Aldo/keto reductase; NADP-dependent oxidoreductase domain | 49709.4 | 5.72 | 5 | 1 | 20.05 | 0.004 | 1D | M | ||

| Am15133 | None detected | 14436.6 | 4.91 | 31 | 3 | 52.74 | 0.168 | SigP | 1D | M, SN | |

| Am17215 | None detected | 95309.3 | 6.93 | 2 | 1 | 16.14 | 0.153 | 11 | S | M | |

| Am17941 | None detected | 115634 | 6.11 | 1 | 1 | 12.04 | –0.085 | 2 | SecP | 2D | M |

| Am18255 | None detected | 90035.9 | 4.75 | 2 | 1 | 14.5 | –0.599 | S | M | ||

| Am18727 | None detected | 10573 | 8.96 | 18 | 1 | 12.61 | –0.73 | SecP | S | M | |

| Am19502 | None detected | 18009.9 | 4.37 | 34 | 3 | 54.75 | 0.623 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am19696 | Ribonuclease/ribotoxin | 15150 | 4.47 | 13 | 1 | 16.89 | –0.209 | SecP | 1D | SN | |

| Am19883 | None detected | 54306.3 | 5.67 | 5 | 1 | 20.27 | –0.729 | S | M | ||

| Am20219 | None detected | 16248.1 | 9.58 | 7 | 1 | 14.89 | –0.966 | 1 | S | M | |

| Am20301 | Histone chaperone domain CHZ | 49025.6 | 5.85 | 5 | 2 | 22.48 | –0.29 | SecP | S | M, SN | |

| Am4394 | None detected | 26796.8 | 7.7 | 4 | 1 | 18.36 | –0.193 | S | M, SN | ||

| Am5361 | None detected | 8625.1 | 8.09 | 41 | 2 | 36.28 | –0.36 | SecP | 2D | M | |

| Am6074 | None detected | 27554.6 | 7.72 | 6 | 1 | 17.89 | –0.087 | S | M | ||

| Am9062 | None detected | 16419.1 | 6.9 | 6 | 1 | 16.06 | –0.066 | 1D | SN | ||

| Am9780 | None detected | 17457.1 | 4.13 | 22 | 3 | 50.38 | 0.52 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am9972 | None detected | 73660.6 | 4.59 | 2 | 1 | 16.89 | –0.112 | SecP | 1D | SN | |

| Am17500 | None detected | 27349.2 | 9.13 | 8 | 2 | 26.53 | –0.607 | SecP | 1D | SN | |

| Am8226 | High mobility group, HMG-I/HMG-Y; AT hook, DNA-binding motif; AT hook-like | 38794 | 7.62 | 18 | 4 | 62.82 | –0.226 | S | M | ||

| Am1474 | None detected | 5325.2 | 6.28 | 29 | 1 | 12.29 | 0.2 | SecP | S | M |

Accession number from A. mellea cDNA database.

InterPro domains located within protein following Blast2GO analysis.

tMr, theoretical molecular mass.

tpI, theoretical isoelectric point.

SM score, Spectrum Mill protein score.

GRAVY score, grand average of hydropathy (Negative score indicates hydrophilicity while Positive score indcates hydrophobicity).

TM, number of transmembrane regions.

SigP, classical secretion signal peptide; SecP, nonclassical secretion signal.

Method: 1D SDS-PAGE prior to LC–MS/MS analysis, 2-D proteins separated in two dimensions prior to LC–MS/MS analysis.

Source: M, mycelia; SN, culture supernatant/secretome.

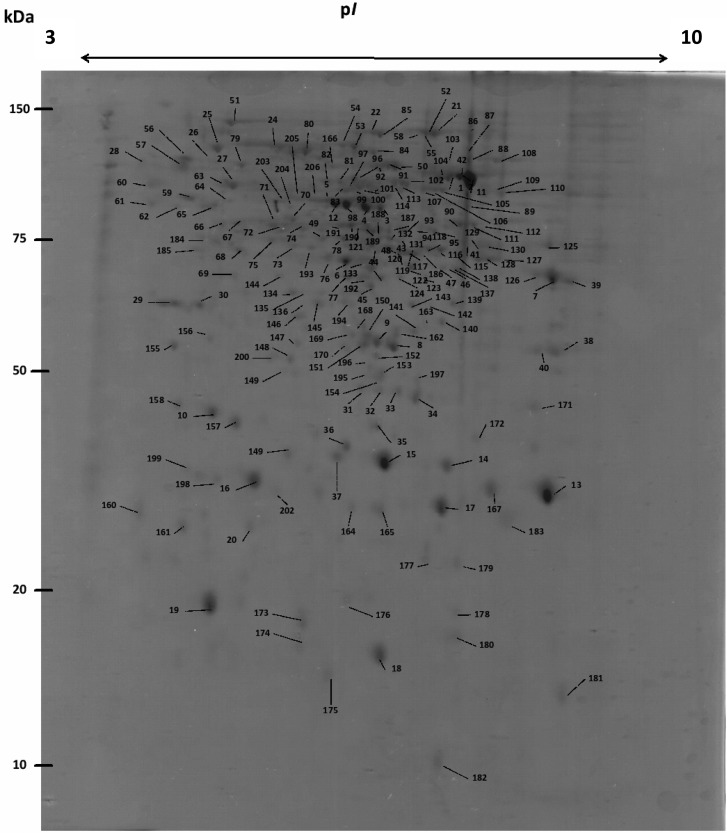

Regarding 2-D PAGE analysis, 206 protein spots were excised, trypsin-digested and subjected to LC–MS/MS. Two hundred twenty five proteins were identified in total. A reference 2-D PAGE map is shown in Figure 3 and information (pI and Mr) on proteins identified can be found in Supplementary Table 2 (as “2D” under column “Method”, Supporting Information). Possible protein isoforms were identified in different spots (e.g., spots 89, 92, 107 (Am10779) and 47, 122, 124, 128, 130 (Am16991). One protein, Am17600, was identified in 17 spots (Nos. 1, 3, 11, 58, 88, 89, 90, 97, 103, 104, 107, 117, 118, 119, 131, 132, 133) probably due to a protease activity or degrading events. BLAST analysis classified this protein as a peroxisomal catalase.

Figure 3.

2-D PAGE reference map of the A. mellea mycelial proteome.

The A. mellea Secretome

A total of 293 proteins were identified in culture supernatants derived from A. mellea, 183 of which were uniquely detected in the secretome, while 111 were also identified in mycelia (Supplementary Table 3, Supporting Information). To overcome the considerable difficulty of precipitating low abundance proteins from liquid culture, A. mellea was grown on agar, which was subsequently gently macerated and the liquid phase subject to TCA precipitation followed by SDS-PAGE fractionation. A nonredundant protein search of the translated A. mellea gene set, identified 226 proteins. Analysis of LC–MS/MS data identified 157 unique proteins, while 37 were uniquely identified by a shotgun strategy without SDS-PAGE fractionation. Sequence coverage ranged from 1 to 55% and 1 to 46% following SDS-PAGE and the shotgun approach, respectively, in the case of supernatant protein analyses (Supplementary Table 3, Supporting Information). Eight proteins were identified in culture supernatants which were A. mellea-specific and included: Am1874, Am2320, Am5632, Am9253, Am11032, Am11414, Am13545 and Am13611. None returned BLAST hits and Am13545 had no InterProScan (IPS) match. IPS revealed low-complexity segments in Am11414, Am2320, Am5632 and Am9253. Analysis revealed two SigP hits (Am11032 and Am13611), three SecP signals (Am11414, Am13545 and Am1874) and a TMHMM search predicted Am11032 to be a hydrophobic membrane protein.

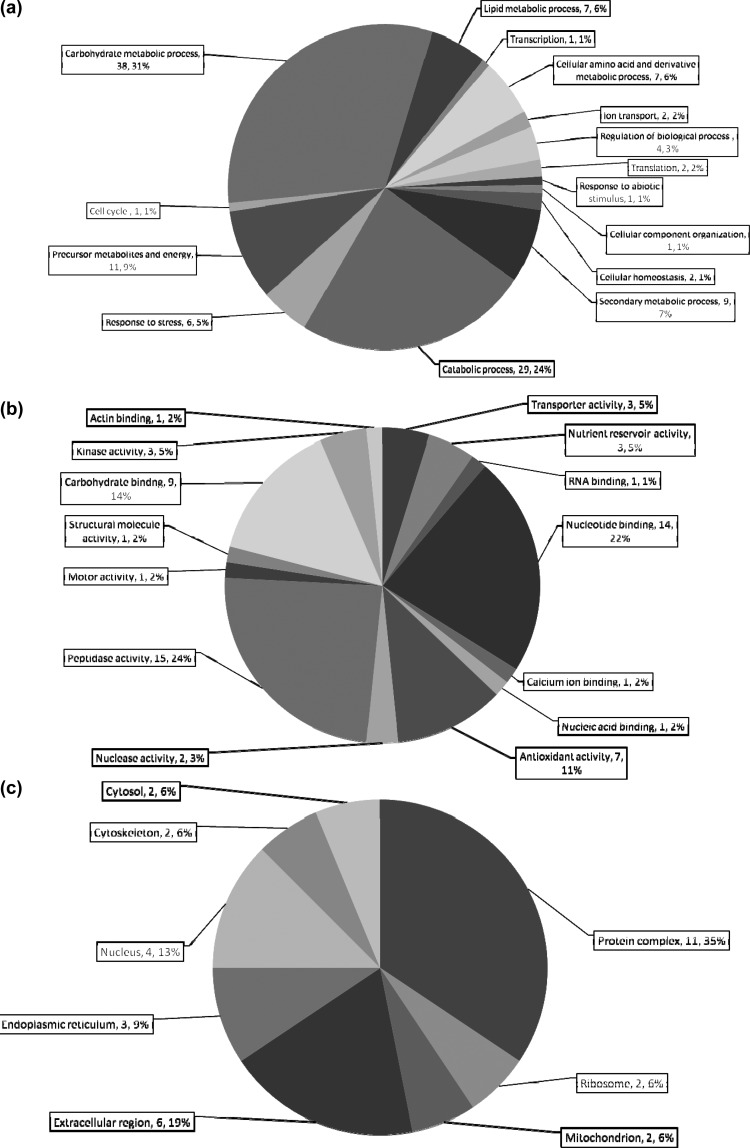

Secretome proteins were classified into 15 distinct biological processes. The proportions of proteins involved in catabolic processes (n = 29) and carbohydrate metabolism (n = 38) was greater (55%) than in mycelia (33%) (Figure 4a). Seven supernatant proteins were GO annotated to be involved in lipid metabolism. This classification was absent for mycelial proteins (Figure 2a). GO analysis related to the molecular function of supernatant proteins showed peptidase activity as the largest functional category (n = 15) followed by nucleotide binding proteins (n = 14). The class including carbohydrate binding proteins represented 14% in the secretome, yet in mycelia it accounted for only 1%. Proteins classified as having antioxidant activity represent 11% of the secretome, while only 3% of mycelial proteins were similarly classified (Figures 2b, 4b). Concerning GO annotation of CC, the largest categories in the secretome comprised protein complexes (n = 11), and extracellular proteins (Figure 4c). Several proteins of intracellular origin were also detected.

Figure 4.

Blast2Go annotation of proteins identified in the secretome. (a) Biological process; (b) molecular function; (c) cellular component. The total number of proteins in each category, as well as the overall %, are given for each subdivision (No., %).

SignalP analysis predicted signal peptide presence for 12% (n = 90) and 50.2% (n = 147) of mycelial and secretome proteins, respectively. Furthermore SecretomeP indicated that 99 secreted proteins (34%) contained a nonclassical secretion signal meaning that less than 20% (55) of those proteins do not contain a secretion signal. GRAVY and Phobius evaluation of hydrophobicity and transmembrane domain presence indicated that 12.7% (n = 93) of mycelial proteins were hydrophobic in nature, 10.5% (n = 77) contained transmembrane regions, and 1.4% (n = 10) contained both a transmembrane region and signal peptide. Six proteins (Am9118, 13744, 6597, 5593, 17215 and 19909) contained greater than 10 transmembrane regions, while 71 proteins contained between 1 and 8 transmembrane domains. With respect to supernatant proteins, 26.3% (n = 77) were hydrophobic in nature, 29 contained predicted transmembrane domains, and 9 of these were also predicted to possess signal sequences.

Glycoside Hydrolases

Although basidiomycetes have been considered as sources of glycoside hydrolases (GH), with potential applications in recalcitrant carbohydrate digestion, no data whatsoever exists on GH complement in A. mellea. Here, we reveal the presence of 226 GH genes in A. mellea (Supplementary Table 5, Supporting Information), and further demonstrate the expression of 52 of these at the protein level, in culture supernatants, under a range of culture conditions (Table 4). Specifically, GH genes belonging to 43 families are present (Supplementary Table 5, Supporting Information). The number of A. mellea GH genes is greater than that identified in either P. chrysosporium (n = 177) or Ceriporiopsis subvermispora (n = 171), both of which are white rot fungi,51 a finding that may be related to the pathogenic nature of A. mellea.

Table 4. Glycoside Hydrolase (GH) Expression Identified from A. mellea Mycelia and Secretome.

| accession no.a | BLAST2GO annotationb | tMrc | tpId | coverage (%) | unique peptides | SM scoree | GRAVY scoref | TMg | SigP/SecPh | methodi | sourcej |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Am13982 | GH | 58105.5 | 5.05 | 6 | 3 | 53.65 | –0.151 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am18619 | GH | 51878.3 | 4.63 | 6 | 1 | 17.68 | –0.039 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am19316 | GH | 49972.4 | 4.76 | 2 | 1 | 16.09 | –0.259 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am9430 | GH Family 1 Protein | 16311.1 | 4.08 | 6 | 1 | 14.64 | –0.401 | SecP | 1D | SN | |

| Am9431 | GH Family 1 Protein | 26301.4 | 5.77 | 7 | 1 | 24.73 | 0.219 | SigP | 1D, S | M, SN | |

| Am9862 | GH Family 1 Protein | 65185 | 5.04 | 1 | 2 | 21.05 | –0.156 | SecP | 1D | SN | |

| Am10289 | GH Family 115 Protein | 114008 | 4.55 | 2 | 2 | 40.53 | –0.094 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am16201 | GH Family 13 Protein | 46456.7 | 4.55 | 9 | 2 | 38.04 | –0.136 | SecP | 1D | SN | |

| Am17847 | GH Family 13 Protein | 56284.6 | 4.94 | 5 | 3 | 58 | –0.24 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am14148 | GH Family 15 Protein | 87387 | 4.97 | 2 | 1 | 17.02 | 0.015 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am14157 | GH Family 15 Protein | 61191.1 | 4.56 | 11 | 4 | 68.88 | 0.016 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am13749 | GH Family 16 Protein | 35677.5 | 4.32 | 4 | 1 | 19.18 | –0.063 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am17932 | GH Family 16 Protein | 48410.8 | 4.69 | 2 | 1 | 17.58 | –0.017 | 1 | SigP | 2D | M |

| Am18038 | GH Family 16 Protein | 39327.9 | 6.39 | 17 | 5 | 80.3 | –0.114 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am19909 | GH Family 16 Protein | 147978 | 9.69 | 1 | 2 | 35.77 | –0.157 | SecP | S | M | |

| Am11859 | GH Family 17 Protein | 39604.6 | 4.44 | 7 | 1 | 22.22 | –0.125 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am18174 | GH Family 18 Protein | 28184 | 4.53 | 15 | 2 | 37.1 | 0.318 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am18992 | GH Family 18 Protein | 54832.1 | 4.96 | 4 | 2 | 28.75 | –0.253 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am6678 | GH Family 2 Protein | 98191.6 | 5.67 | 2 | 1 | 16.69 | –0.455 | S | M | ||

| Am12096 | GH Family 20 Protein | 61819.8 | 4.98 | 3 | 1 | 17.55 | –0.067 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am9564 | GH Family 20 Protein | 59239.4 | 4.75 | 7 | 3 | 42.51 | –0.083 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am14135 | GH Family 27 Protein | 47065 | 4.7 | 18 | 5 | 91.48 | –0.182 | 1D, S | M, SN | ||

| Am17468 | GH Family 28 Protein | 8969.1 | 9.4 | 20 | 1 | 21.85 | 0.087 | SecP | 1D | SN | |

| Am17470 | GH Family 28 Protein | 44505.2 | 4.76 | 7 | 2 | 37.48 | 0.001 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am12215 | GH Family 3 Protein | 148863 | 5.59 | 2 | 2 | 38.48 | –0.211 | SecP | 1D, S | M, SN | |

| Am15538 | GH Family 3 Protein | 81458.6 | 4.62 | 2 | 1 | 23.05 | –0.021 | SigP | 1D, S | M, SN | |

| Am4117 | GH Family 3 Protein | 66127.4 | 4.54 | 6 | 4 | 59.81 | 0.014 | 1 | SecP | 1D | SN |

| Am4142 | GH Family 3 Protein | 110105 | 4.95 | 3 | 3 | 49.7 | –0.151 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am9629 | GH Family 3 Protein | 94245.5 | 5.9 | 2 | 1 | 16.83 | –0.238 | S | M | ||

| Am19156 | GH Family 31 Protein | 105123 | 5.18 | 1 | 1 | 14.1 | –0.137 | 1 | SecP | 1D | SN |

| Am5759 | GH Family 31 Protein | 191108 | 6.39 | 2 | 4 | 60.82 | –0.498 | 1 | 1D, S | SN | |

| Am14693 | GH Family 37 Protein | 71119.8 | 4.35 | 6 | 3 | 44.78 | –0.258 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am14694 | GH Family 37 Protein | 15385 | 4.14 | 7 | 1 | 16.41 | –0.11 | SecP | 1D | SN | |

| Am14901 | GH Family 38 Protein | 116608 | 6.16 | 3 | 1 | 13.06 | –0.311 | S | M | ||

| Am13752 | GH Family 47 Protein | 59389.7 | 4.97 | 32 | 15 | 282.75 | –0.154 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am10113 | GH Family 5 Protein | 88731.2 | 4.81 | 2 | 1 | 19.29 | –0.446 | 1 | SecP | 1D | SN |

| Am12892 | GH Family 5 Protein | 64378.6 | 6.12 | 12 | 4 | 68.82 | –0.515 | 1D, 2D, S | M | ||

| Am14455 | GH Family 5 Protein | 77060.8 | 4.83 | 1 | 1 | 19.42 | –0.032 | 6 | 1D | SN | |

| Am15965 | GH Family 5 Protein | 46113.4 | 4.8 | 25 | 6 | 108.18 | –0.212 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am17147 | GH Family 5 Protein | 57264.9 | 4.97 | 2 | 1 | 13.01 | –0.272 | SecP | 2D | M | |

| Am8313 | GH Family 5 Protein | 75693.8 | 6.8 | 1 | 1 | 19.28 | 0.322 | 9 | SecP | 1D | SN |

| Am19121 | GH Family 55 Protein | 79789 | 6.09 | 2 | 1 | 27.82 | –0.147 | SecP | 1D | SN | |

| Am19122 | GH Family 55 Protein | 62305.6 | 4.43 | 2 | 1 | 22.56 | –0.077 | SecP | 1D | SN | |

| Am15544 | GH Family 61 Protein | 22656.6 | 4.7 | 9 | 1 | 11.98 | 0.212 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am15111 | GH Family 72 Protein | 58531.8 | 4.34 | 11 | 5 | 84.6 | –0.01 | SigP | 1D, S | M, SN | |

| Am13430 | GH Family 74 Protein | 85505.4 | 4.88 | 2 | 1 | 11.49 | –0.154 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am17906 | GH Family 78 Protein | 71627.9 | 4.32 | 1 | 1 | 16.07 | –0.146 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am18634 | GH Family 79 Protein | 38585.2 | 4.86 | 19 | 5 | 84.99 | –0.019 | SecP | 1D | SN | |

| Am9625 | GH Family 79 Protein | 55806 | 4.49 | 5 | 1 | 14.53 | –0.064 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am17712 | GH Family 92 Protein | 87085.9 | 4.84 | 15 | 7 | 112.69 | –0.203 | SigP | 1D | SN | |

| Am9020 | GH Family 92 Protein | 86824.7 | 4.98 | 3 | 1 | 15.69 | –0.425 | SigP | 1D, 2D | M, SN | |

| Am7125 | GH Family 95 Protein | 89157.1 | 4.8 | 13 | 8 | 125.65 | –0.138 | 1D | SN |

Accession number from A. mellea cDNA database.

Blast annotation following Blast2GO analysis of proteins identified from cDNA database.

tMr, theoretical molecular mass.

tpI, theoretical isoelectric point.

SM score, Spectrum Mill protein score.

GRAVY score, grand average of hydropathy (Negative score indicates hydrophilicity while Positive score indcates hydrophobicity).

TM, number of transmembrane regions.

SigP, classical secretion signal peptide; SecP, nonclassical secretion signal.

Method: 1D SDS-PAGE prior to LC–MS/MS analysis, 2-D proteins separated in two dimensions prior to LC–MS/MS analysis.

Source, M: mycelia; SN: culture supernatant/secretome.

The A. mellea genome encodes 16 xyloglucan:xyloglucosyltransferases (GH16 family, Supplementary Table 5, Supporting Information). Xyloglucan, a hemicellulose, is a major component of plant cell walls whereby its cellulose binding capacity provides structural support for the cell wall.52 GH 16 family enzymes cleave the 1–4 glycosidic backbone of xyloglucan and transfer the segment either to another xyloglucan or to a xyloglucan oligosaccharide (XGO), thus restructuring and modifying the primary cell wall.53 XGOs have been shown to activate plant cellulases and promote plant growth, but plant XGOs do not activate fungal cellulase.54 The GH16 family proteins also have amylase and cellulase activity. Two enzymes (Am17743 and Am19909) in this class were also implicated in GTPase activity, which may indicate a signaling role.55 Other GH families with increased or decreased representation in the A. mellea genome compared to lignolytic and cellulolytic fungi are reported in Table 5. Contrary to expectation that lignolytic fungi would have similar frequencies of particular GH family proteins, A. mellea appears to contain more GH28, GH61, and GH76 family members than the other white or brown rot fungi (Table 5). For example, 17 GH28 genes (endo/exo-(rhamno)galacturonases, essential for pectin degradation) are present in the A. mellea genome (Supplementary Table 5, Supporting Information) in comparison to the 6 identified in L. bicolor and the 4 present in P. chrysosporium. Yet, A. mellea possesses similar GH family occurrence to ascomycete species. Moreover, GH109, an α-N-acetylgalactosaminidase present in A. mellea and the mycorrhizial L. bicolor (Supplementary Table 5, Supporting Information), has previously been also identified in prokaryotes and its crystal structure defined.56

Table 5. Comparison of A. mellea with Lignolytic and Cellulolytic Basidiomycetes and Ascomycetes with Respect to Four Glycoside Hydrolase Families Present in the Respective Genomes.

| GH family |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fungus | 28 | 35 | 47 | 76 |

| Armillaria mellea | 20 | 8 | 12 | 8 |

| Ceriporiopsis subvermispora | 6 | 1 | 4 | |

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | 4 | 3 | 6 | |

| Schizophyllum commune H4–8 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 3 |

| Coprinopsis cinerea Okayama 7 (#130) | 3 | 8 | ||

| Postia placenta Mad-698-R | 7 | 1 | 5 | |

| Podospora anserina S mat+ | 1 | 9 | 9 | |

| Aspergillus niger CBS 513.88 | 21 | 5 | 5 | 11 |

| Aspergillus nidulans FGSC A4 | 9 | 4 | 7 | 7 |

Chitinases, GH18 (endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidases) (n = 11), are also encoded within the genome, and the expression of two of these was detectable in A. mellea culture supernatants (Am17468 and Am17470) (Supplementary Table 3, Supporting Information). In addition to glycoside hydrolases, 72 glycosyltransferase and 19 polysaccharide lyases have been identified (Supplementary Table 5, Supporting Information).

Carbohydrate-binding Modules (CBM)

Besides glycoside hydrolases, other CBM enzymes were discovered in the A. mellea genome. CBM proteins exhibit three functions encompassing (i) carbohydrate binding and concentration of enzymes on the substrate, (ii) binding to the polysaccharides that are the substrate targets of the catalytic moiety of the enzyme and (iii) substrate degradation.57 Three CBM proteins were identified (Am18408, AM9123 and Am11736) by LC–MS/MS analysis, belonging to families 1, 12 and 13, respectively (Table 4). CBM1 is a small module (40 aa) that binds cellulose. CBM12 previously only described in bacteria, comprises 40–60 residues, binds chitin, which is unusual among CBM proteins which have broad polysaccharide specificity. The C-terminus of the chitin binding domain (ChBD) binds very specifically to insoluble chitin but not to chitin oligosaccharides or glucose.57 Interestingly, chitinases have been investigated as biotechnological biocontrol for plant pathogenic fungi.58 CBM13 is a 150 residue module that has been identified in galactose-binding plant lectins.57 Predominantly found in bacteria, they have also been identified in eukaryotes, including some fungi; CBM13 modules occur in glycoside hydrolases and glycosyltransferases and also bind xylan.

Carbohydrate Esterases

Compared to some basidiomycete and ascomycete species, A. mellea has increased representation of carbohydrate esterase (CE) families (Supplementary Table 5, Supporting Information), specifically CE4, CE8, CE9 and CE14 comprised 94 genes. CE1 is an acetyl xylan esterase (AXE) which depolymerises xylan microfibrils and solubilizes lignocellulosic material and releases fermentable sugars.59 A CE1 enzyme (Am19807) was identified at the protein level in the growth condition we tested (Supplementary Table 2, Supporting Information). The CE4 family exhibits acetyl xylan, chitin, chitooligosaccharide and peptidoglycan deacetylase activity. Four CE4 enzymes (Am18938, Am3987, Am3988, and Am6064) have been identified in A. mellea culture in both mycelia and secretome (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3, Supporting Information). These enzymes act on N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) which is present in bacterial as well as fungal cell walls; have very broad substrate specificity and catalyze the hydrolysis of acetyl groups from xylan and carbon–nitrogen bonds in linear amides. They act in concert with chitinases to deacetylate both chitin and chitosan.60 Chitin deacetylases (CDA) are secreted during hyphal penetration of plants by Colletotrichum lindemuthianum. Tsigos and Bouriotis hypothesized that chitin of invading pathogens triggers recognition by plant defenses inducing plant chitinase activity which gives rise to formation of lignin and callus.61 Deacetylases modify plant chitinases thereby neutralizing plant defenses, and modify chitin to chitosan which plant deacetylases are unable to modify, thus enabling the fungus to invade the plant. Pectin methylesterase (PME) are members of the CE8 family and catalyze the demethyloxidation of pectin, a major plant cell wall polysaccharide. PME disrupts pectin structure and makes it liable to subsequent enzymatic depolymerisation. PMEs are important in vegetative and reproductive plant development, but pathogenic fungi can also degrade pectin in the cell wall during plant invasion.62 One CE8 (Am12061) was identified in A. mellea culture supernatants. CE9 (N-acetylglucosamine 6-phosphate deacetylase) is another gene family detected in A. mellea which is involved in carbohydrate, specifically N-acetyglucosamine, catabolism.63 Surprisingly, a GlcNAc-6-phosphate deacetylase (DAC1) has been linked to C. albicans virulence.64 The CE14 deacetylase family has a conserved LmbE domain which catalyzes the N-deacetylation of appropriate substrates.65 Tanaka et al. identified a deacetylase from Thermococcus kodakarensis KOD1 which degrades diacetylchitobiose (GlcNAc2) to GlcN–GlcNAc which in a second round of deacetylation is deacetylated to GlcN.66 Another function of these enzymes in eukaryotes is GPI anchor modification.67

Laccases

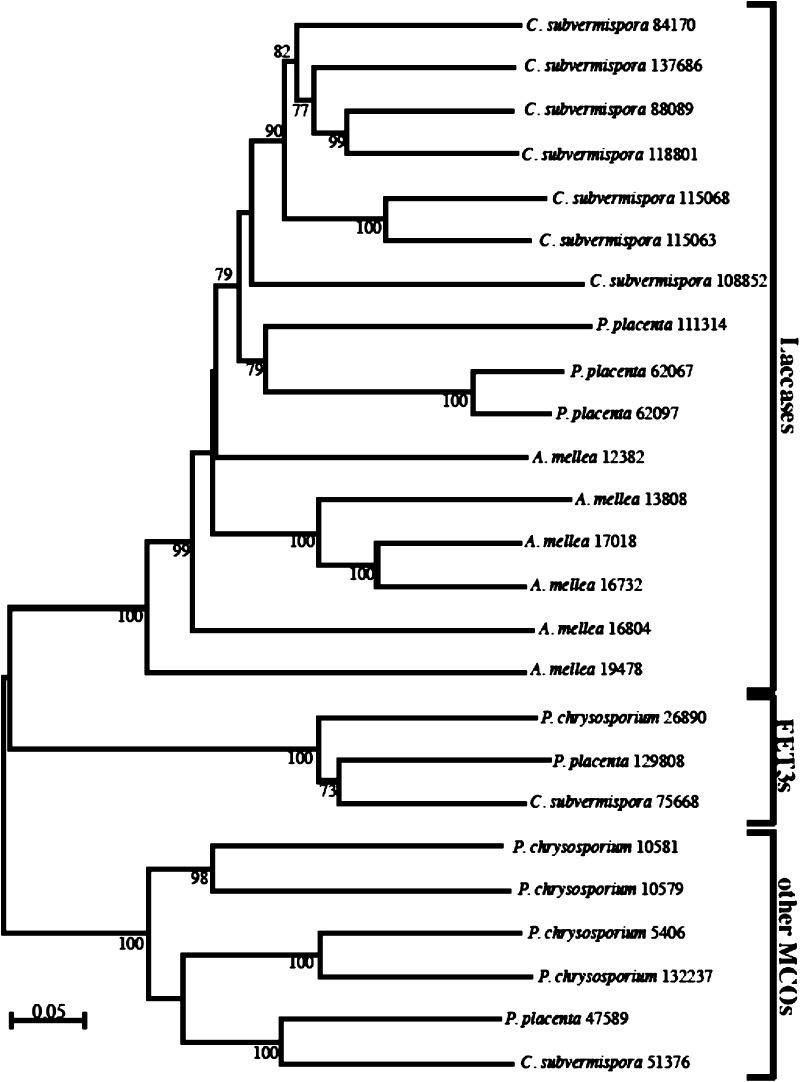

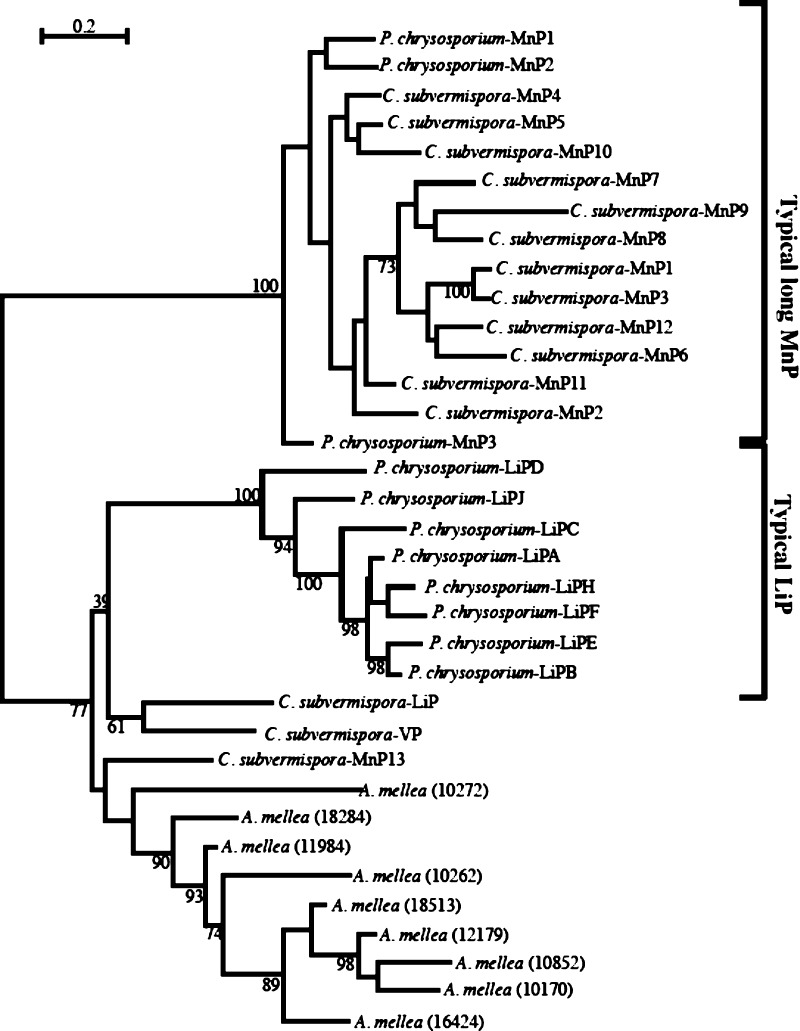

The A. mellea genome encodes 6 laccases (Am380, Am12382, Am16732, Am16804, Am17018 and Am19478) (Figure 5), all of which contain the canonical L1-L4 signature sequences, characteristic of this multicopper oxidase (MCO) family of enzymes.68 Overall, 15 laccase-like enzymes are encoded within the A. mellea genome. Laccase Am380 expression was detected in mycelial and supernatant by LC–MS/MS analysis (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3, Supporting Information), while expression of any other laccase was undetectable under the condition tested. Expression of two laccase-like enzymes (Lcc5: Am2859 and Am4666) was also evident in the A. mellea secretome (Supplementary Table 3, Supporting Information). Notably, the genome of the white rot fungus P. chrysosporium does not encode any laccase,51 while those of C. subvermispora(51) and L. bicolor(69) encode 7 and 9 laccase gene models, respectively.

Figure 5.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of laccase protein sequences of A. mellea. Sequences were aligned using MUSCLE (v3.6),84 with the default settings. Appropriate protein model of substitution was selected using ModelGenerator.40 One-hundred bootstrap replicates were applied with the appropriate protein model using the software program PHYML (v3.0)85 and summarized using the majority-rule consensus method. Monophyletic laccases, canonical ferroxidases (FET3) and other multicopper oxidases (MCO) are highlighted.

Peroxidases

Basidiomycete peroxidases are a class of oxidoreductase involved in lignin biodegradation70,71 In white rot fungi, ligninolytic haem peroxidases have been shown to cleave the main linkage types in lignin due to their high redox-potential and specialized catalytic mechanisms.70 To date, three ligninolytic haem peroxidases have been isolated and characterized in white-rot fungal species. These include lignin peroxidase (LiP), characterized by its ability to oxidize high redox-potential compounds such as alcohol and methoxybenzenes and veratryl,70 manganese peroxidase (MnP) which exhibits an ability to oxidize Mn2+ to Mn3+72 and versatile peroxidase (VP) which can oxidize both LiP and MnP substrates.73 Our genome analysis and subsequent homology modeling74 infers that A. mellea contains nine putative ligninolytic peroxidases. In an attempt to elucidate the function of the A. mellea peroxidases we reconstructed a phylogenetic tree using representative MnP, LiP and VP sequences from C. subvermispora and P. chrysosporium.51 Our phylogeny infers that the A. mellea peroxidases are the result of a species-specific expansion as they are clustered together in a monophyletic clade (Figure 6). Interestingly the A. mellea-specific clade is clustered beside C. subvermispora MnP13, and this gene has previously been described as a short MnP.51 The length of the A. mellea genes is comparable to typical MnPs however (not shown). The phylogeny also infers that the A. mellea genes are more closely related to P. chrysosporium LiP genes than the “typical” C. subvermispora MnP genes (Figure 6). However, close sequence inspection shows that the A. mellea peroxidases do not contain the conserved aromatic substrate oxidation sites required for LiP enzymatic activity.75 Furthermore, five of the nine A. mellea peroxidases contain the three acidic residues (two glutamates and an aspartate) required for the Mn2+ binding site of MnPs. Based on this observation we hypothesize that at least five of the peroxidases found in A. mellea have MnP activity.

Figure 6.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of peroxidase protein sequences of A. mellea. Sequences were aligned using MUSCLE (v3.6),84 with the default settings. Appropriate protein model of substitution was selected using ModelGenerator.40 One hundred bootstrap replicates were used with the appropriate protein model using the software program PHYML (v3.0)85 and summarized using the majority-rule consensus method.

Fungal Coculture

Comparative growth studies of C. albicans recovered from either mono- or coculture conditions demonstrates that significant killing (p = 0.0004) of C. albicans by A. mellea occurs in cocultures (Figure 7). This observation can be associated with the detection of 30 A. mellea proteins, not identified under any other culture condition (Table 6) including redox-active, degradative and attack-type proteins. Interestingly, Cys-2 peroxiredoxin (Am10593) and thioredoxin (Am7929) were both uniquely detected in fungal cocultures. Cys-2 peroxiredoxin converts peroxides to water, with concomitant formation of intramolecular disulfide linkages. These disulfide linkages are in turn reduced by thioredoxin to regenerate the active form of Cys-2 peroxiredoxin.76,77 We speculate that this system may be induced in A. mellea as an antifungal response to C. albicans presence. Alternatively, peroxide dismutation may be required to attenuate products originating from C. albicans cell wall degradation. In this regard, it is notable that a class II chitinase (Am13890) was also uniquely detected in fungal cocultures which may be deployed by A. mellea to degrade Candida cell wall material. Two proteins classified as prohibitins (termed Am14001 and Am20304), which have been proposed to be involved in the negative regulation of cell proliferation,78,79 have also been identified elsewhere.80 Intriguingly, Am3423 is classified by PFAM as a GPI-anchored protein. These serine-threonine-rich membrane proteins are anchored by glycosylphosphatidylinositol ligands. Several GPI-anchored proteins have been characterized in fungi as having multiple functions including cell wall organization in A. fumigatus, fruiting body formation in Lentinus edodes, and interaction with MAPK, where they may have a signaling role.81 Am3423 belongs to the same protein family of DRMIP, Hesp-379, which is a haustorially expressed secreted protein involved in host tissue penetration in L. edodes.82 In addition, a number of oxidoreductases, monooxygenases, reductases and dehydrogenases of basidiomycete origin were detected in the fungal cocultures (Table 6). Similarly, metabolite extracts from A. tabescens have also been observed to exhibit antifungal activity.83 Apart from demonstrating the power of proteomic investigations to dissect fungal–fungal interactions, the coculture system we have developed for A. mellea and C. albicans may represent a model system for the further investigations of A. mellea pathogenicity.

Figure 7.

Fungicidal affect of A. mellea against C. albicans in coculture. (A) Culture plates: (i) C. albicans only; (ii) Coculture of C. albicans and A. mellea for up to 52 days. Reculture of C. albicans was carried out from multiple plugs taken from inoculation points (arrows). (B) Comparative viable cell count of recultured C. albicans from single and coculture plates shows that coculture with A. mellea results in significant (p = 0.0004) killing of C. albicans. (C) Fluorescent determination of C. albicans viability. Simultaneous FDA (live) and PI (dead) cell staining of C. albicans. 1. C. albicans live culture (24 h; positive control); 2. C. albicans killed by autoclaving (negative control); 3. Monoculture of C. albicans and 4. C. albicans following coculture with A. mellea (A.). Magnification: 20×.

Table 6. Proteins Found Uniquely in Coculture of A. mellea and C. albicans.

| accession no.a | BLAST2GO annotationb | tMrc | tpId | coverage (%) | unique peptides | SM scoree | GRAVY scoref | TMg | SigP/SecPh | methodi | sourcej |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Am5344 | 60s ribosomal protein l10a | 12603.7 | 9.6 | 10.7 | 1 | 11.51 | –0.7 | SecP | S | SN | |

| Am12506 | Aryl-alcohol oxidase | 64088.4 | 4.7 | 2.7 | 1 | 16.33 | –0.1 | SigP | S | SN | |

| Am17545 | Coproporphyrinogen iii oxidase | 103512.9 | 9.5 | 15.7 | 4 | 79.77 | –0.1 | 2.0 | S | SN | |

| Am10593 | Cys 2 peroxiredoxin | 22242.4 | 5.2 | 6.5 | 1 | 12.87 | –0.2 | SecP | S | SN | |

| Am9607 | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit v | 24861.9 | 9.7 | 7.5 | 1 | 20.74 | –0.3 | 2.0 | SecP | S | SN |

| Am19980 | F1F0-ATP syn F | 15435.1 | 10.5 | 14.5 | 1 | 19.06 | –0.1 | 1.0 | SecP | S | SN |

| Am16128 | Glycerol-3-phosphate o-acyltransferase | 64013.5 | 9.8 | 3.3 | 1 | 13.13 | 0.0 | 3.0 | S | SN | |

| Am13890 | Glycosyl hydrolase 53 domain-containing protein | 21828.7 | 6.9 | 14.7 | 1 | 18.79 | 0.0 | SigP | S | SN | |

| Am13814 | Hypothetical protein | 8166.3 | 5.8 | 18.7 | 1 | 18.59 | –0.3 | S | SN | ||

| Am13829 | Hypothetical protein | 66976.6 | 6.0 | 7.9 | 2 | 26.2 | –0.3 | SecP | S | SN | |

| Am18856 | Hypothetical protein | 30601.9 | 9.5 | 6.1 | 1 | 13.69 | 0.4 | 4.0 | SigP | S | SN |

| Am12218 | Hypothetical protein | 56022.9 | 4.6 | 4.1 | 1 | 14.46 | –0.2 | SigP | S | SN | |

| Am12353 | Iron–sulfur protein subunit | 30797.5 | 8.7 | 9.7 | 1 | 13.5 | –0.5 | SecP | S | SN | |

| Am19926 | Lipoic acid synthase | 67338.7 | 9.6 | 3.3 | 1 | 16.04 | –0.2 | 1.0 | S | SN | |

| Am16692 | Unknown Function Protein | 25812.9 | 4.6 | 6.5 | 1 | 17.44 | –0.4 | S | SN | ||

| Am13379 | Nadh dehydrogenase | 61958.6 | 9.3 | 3.2 | 1 | 15 | –0.2 | 2.0 | SecP | S | SN |

| Am14001 | Prohibitin Phb1 | 26007.0 | 6.9 | 7.9 | 1 | 20.8 | 0.1 | SigP | S | SN | |

| Am20343 | Unknown Function Protein | 10943.5 | 9.1 | 21.2 | 1 | 13.75 | –0.3 | SecP | S | SN | |

| Am3423 | Unknown Function Protein | 13693.7 | 4.6 | 18.1 | 1 | 20.53 | 0.2 | SigP | S | SN | |

| Am6084 | Unknown Function Protein | 32823.9 | 5.7 | 9.8 | 1 | 13.81 | –0.5 | SecP | S | SN | |

| Am20304 | Proteolysis and peptidolysis-related protein | 22016.4 | 8.7 | 6.6 | 1 | 15.62 | –0.2 | SecP | S | SN | |

| Am17796 | Secreted protein | 46381.6 | 5.9 | 12.1 | 2 | 36.22 | 0.0 | S | SN | ||

| Am18628 | Subunit Vib of cytochrome c oxidase | 10044.2 | 5.3 | 15.1 | 1 | 12.99 | –0.8 | SecP | S | SN | |

| Am15086 | Succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase | 74240.9 | 8.5 | 2.0 | 1 | 15.07 | 0.1 | 4.0 | SecP | S | SN |

| Am16124 | Sulfide-quinone oxidoreductase | 118017.6 | 8.7 | 4.0 | 2 | 33.19 | –0.4 | 2.0 | S | SN | |

| Am7929 | Thioredoxin | 13706.0 | 4.7 | 15.6 | 1 | 15.39 | 0.1 | S | SN | ||

| Am14705 | Twin-arginine translocation pathway signal | 63826.1 | 5.8 | 4.9 | 1 | 16.77 | 0.0 | SecP | S | SN | |

| Am2793 | Ubiquitin domain-containing | 37237.5 | 5.2 | 6.4 | 1 | 16.2 | –0.2 | S | SN | ||

| Am18503 | Uracil phosphoribosyltransferase | 19530.7 | 4.9 | 10.3 | 1 | 15.46 | 0.2 | SecP | S | SN | |

| Am14973 | Urea hydro-lyase cyanamide hydratase | 28060.0 | 5.7 | 8.4 | 1 | 19.82 | –0.2 | SecP | S | SN |

Accession number from A. mellea cDNA database.

Blast annotation following Blast2GO analysis of proteins identified from cDNA database.

tMr, theoretical molecular mass.

tpI, theoretical isoelectric point.

SM score, Spectrum Mill protein score.

GRAVY score, grand average of hydropathy.

TM, number of transmembrane regions.

SigP, classical secretion signal peptide; SecP, nonclassical secretion signal.

Method: 1D SDS-PAGE prior to LC–MS/MS analysis, 2-D proteins separated in two dimensions prior to LC–MS/MS analysis.

Source, M: mycelia; SN: culture supernatant/secretome.

Conclusions

Combined application of Illumina sequencing with LC–MS/MS has, for the first time, revealed new insights into the proteome of the important fungal plant pathogen Armillaria mellea, including the identification of multiple glycodegradative enzyme systems which can be useful for recalcitrant carbon compound degradation in biotechnology applications. Moreover, proteomics tools shed light on potent antifungal properties of A. mellea, which in part may be mediated by basidiomycete enzymes.

Acknowledgments

C.C. was a recipient of an NUI Travelling Fellowship and John & Pat Hume Scholarship from NUI Maynooth. Mass spectrometry facilities and materials were funded by the Higher Education Authority, in part via PRTLI-4. The sequencing and de novo assembly was carried out at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute and funded by the Wellcome Trust. Grainne O’Keeffe was funded by Science Foundation Ireland (PI/11/1188).

Supporting Information Available

Supplemental tables and figure. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

§ D.A.F. and S.D. contributed equally to the work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Erjavec J.; Kos J.; Ravnikar M.; Dreo T.; Sabotic J. Proteins of higher fungi--from forest to application. Trends Biotechnol. 2012, 305259–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kämper J.; Kahmann R.; Bölker M.; Ma L. J.; Brefort T.; Saville B. J.; Banuett F.; Kronstad J. W.; Gold S. E.; M̧ller O. Insights from the genome of the biotrophic fungal plant pathogen Ustilago maydis. Nature 2006, 444711597–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin F.; Aerts A.; Ahren D.; Brun A.; Danchin E. G. J.; Duchaussoy F.; Gibon J.; Kohler A.; Lindquist E.; Pereda V. The genome of Laccaria bicolor provides insights into mycorrhizal symbiosis. Nature 2008, 452718388–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rioux R.; Manmathan H.; Singh P.; de los Reyes B.; Jia Y.; Tavantzis S. Comparative analysis of putative pathogenesis-related gene expression in two Rhizoctonia solani pathosystems. Curr. Genet. 2011, 576391–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner K.; Coetzee M. P.; Hoffmeister D. Secrets of the subterranean pathosystem of Armillaria. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2011, 126515–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desjardin D. E.; Oliveira A. G.; Stevani C. V. Fungi bioluminescence revisited. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2008, 72170–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner K.; Fujiyoshi P.; Foster G. D.; Bailey A. M. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation for investigation of somatic recombination in the fungal pathogen Armillaria mellea. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76247990–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muszynska B.; Sulkowska-Ziaja K.; Wolkowska M.; Ekiert H. Chemical, pharmacological, and biological characterization of the culinary-medicinal honey mushroom, Armillaria mellea (Vahl) P. Kumm. (Agaricomycetideae): a review. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2011, 132167–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly D. M.; Abe F.; Coveney D.; Fukuda N.; O’Reilly J.; Polonsky J.; Prange T. Antibacterial sesquiterpene aryl esters from Armillaria mellea. J. Nat. Prod. 1985, 48110–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez D.; Larrondo L. F.; Putnam N.; Gelpke M. D.; Huang K.; Chapman J.; Helfenbein K. G.; Ramaiya P.; Detter J. C.; Larimer F.; Coutinho P. M.; Henrissat B.; Berka R.; Cullen D.; Rokhsar D. Genome sequence of the lignocellulose degrading fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium strain RP78. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004, 226695–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohm R. A.; de Jong J. F.; Lugones L. G.; Aerts A.; Kothe E.; Stajich J. E.; de Vries R. P.; Record E.; Levasseur A.; Baker S. E.; Bartholomew K. A.; Coutinho P. M.; Erdmann S.; Fowler T. J.; Gathman A. C.; Lombard V.; Henrissat B.; Knabe N.; Kues U.; Lilly W. W.; Lindquist E.; Lucas S.; Magnuson J. K.; Piumi F.; Raudaskoski M.; Salamov A.; Schmutz J.; Schwarze F. W.; vanKuyk P. A.; Horton J. S.; Grigoriev I. V.; Wosten H. A. Genome sequence of the model mushroom Schizophyllum commune. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 289957–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stajich J. E.; Wilke S. K.; Ahren D.; Au C. H.; Birren B. W.; Borodovsky M.; Burns C.; Canback B.; Casselton L. A.; Cheng C. K.; Deng J.; Dietrich F. S.; Fargo D. C.; Farman M. L.; Gathman A. C.; Goldberg J.; Guigo R.; Hoegger P. J.; Hooker J. B.; Huggins A.; James T. Y.; Kamada T.; Kilaru S.; Kodira C.; Kues U.; Kupfer D.; Kwan H. S.; Lomsadze A.; Li W.; Lilly W. W.; Ma L. J.; Mackey A. J.; Manning G.; Martin F.; Muraguchi H.; Natvig D. O.; Palmerini H.; Ramesh M. A.; Rehmeyer C. J.; Roe B. A.; Shenoy N.; Stanke M.; Ter-Hovhannisyan V.; Tunlid A.; Velagapudi R.; Vision T. J.; Zeng Q.; Zolan M. E.; Pukkila P. J. Insights into evolution of multicellular fungi from the assembled chromosomes of the mushroom Coprinopsis cinerea (Coprinus cinereus). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1072611889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbas A.; Koc H.; Liu F.; Tien M. Fungal degradation of wood: initial proteomic analysis of extracellular proteins of Phanerochaete chrysosporium grown on oak substrate. Curr. Genet. 2005, 47149–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu M.; Yuda N.; Nakamura T.; Tanaka H.; Wariishi H. Metabolic regulation at the tricarboxylic acid and glyoxylate cycles of the lignin-degrading basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium against exogenous addition of vanillin. Proteomics 2005, 5153919–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravalason H.; Jan G.; Molle D.; Pasco M.; Coutinho P. M.; Lapierre C.; Pollet B.; Bertaud F.; Petit-Conil M.; Grisel S.; Sigoillot J. C.; Asther M.; Herpoel-Gimbert I. Secretome analysis of Phanerochaete chrysosporium strain CIRM-BRFM41 grown on softwood. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 804719–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horie K.; Rakwal R.; Hirano M.; Shibato J.; Nam H. W.; Kim Y. S.; Kouzuma Y.; Agrawal G. K.; Masuo Y.; Yonekura M. Proteomics of two cultivated mushrooms Sparassis crispa and Hericium erinaceum provides insight into their numerous functional protein components and diversity. J. Proteome Res. 2008, 751819–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plett J. M.; Kemppainen M.; Kale S. D.; Kohler A.; Legue V.; Brun A.; Tyler B. M.; Pardo A. G.; Martin F. A secreted effector protein of Laccaria bicolor is required for symbiosis development. Curr. Biol. 2011, 21141197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent D.; Kohler A.; Claverol S.; Solier E.; Joets J.; Gibon J.; Lebrun M. H.; Plomion C.; Martin F. Secretome of the free-living mycelium from the ectomycorrhizal basidiomycete Laccaria bicolor. J. Proteome Res. 2012, 111157–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox K. D.; Scherm H.; Riley M. B. Characterization of Armillaria spp. from peach orchards in the southeastern United States using fatty acid methyl ester profiling. Mycol. Res. 2006, 110Pt 4414–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrettl M.; Carberry S.; Kavanagh K.; Haas H.; Jones G. W.; O’Brien J.; Nolan A.; Stephens J.; Fenelon O.; Doyle S. Self-protection against gliotoxin--a component of the gliotoxin biosynthetic cluster, GliT, completely protects Aspergillus fumigatus against exogenous gliotoxin. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 66e1000952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H. C.; Mikami Y.; Imai T.; Taguchi H.; Nishimura K.; Miyaji M.; Branchini M. L. Extrusion of fluorescein diacetate by multidrug-resistant Candida albicans. Mycoses 2001, 449–10368–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sicoli G.; Fatehi J. Development of species-specific PCR primers on rDNA for the identification of European Armillaria species. Forest Pathol. 2003, 335287–297. [Google Scholar]

- Misiek M.; Hoffmeister D. Processing sites involved in intron splicing of Armillaria natural product genes. Mycol. Res. 2008, 112Pt 2216–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozarewa I.; Turner D. J. Amplification-free library preparation for paired-end Illumina sequencing. Methods Mol. Biol. 2009, 733, 257–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.; Ruan J.; Durbin R. Mapping short DNA sequencing reads and calling variants using mapping quality scores. Genome Res. 2008, 18111851–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]