Abstract

Tri alkyl phosphate esters are a class of anthropogenic organics commonly found in surface waters of Europe and North America, due to their frequent application as flame retardants, plasticizers, and solvents. Four tri alkyl phosphate esters were evaluated to determine second-order rates of reaction with ultraviolet- and ozone-generated •OH in water. In competition with nitrobenzene in UV irradiated hydrogen peroxide solutions tris(2-butoxyethyl) phosphate (TBEP) was fastest to react with •OH (kOH,TBEP=1.03×1010 M-1s-1), followed sequentially by tributyl phosphate (TBP), tris(2-chloroethyl) phosphate (TCEP), and tris(2-chloroisopropyl) phosphate (TCPP) (kOH,TBEP=6.40×109, kOH,TBEP=5.60×108, & kOH,TBEP=1.98×10 M-1s-1). A two-stage process was used to test the validity of the determined kOH for TBEP and the fastest reacting halogenated alkyl phosphate, TCEP. First, •OH oxidation of TCEP and TBEP, in competition with nitrobenzene, was measured in ozonated hydrogen peroxide solutions. Applying multiple regression analysis, it was determined that the UV-H2O2 and O3-H2O2 data sets were statistically identical for each compound. The subsequent validated kOH were used to predict TCEP and TBEP photodegradation in neutral pH, model surface water after chemical oxidant addition and UV irradiation (up to 1000 mJ/cm2). The insignificant difference, between the predicted TBEP and TCEP photodegradation and a best-fit of the first-order exponential decay function to the observed TBEP and TCEP concentrations with increasing UV fluence, was further evidence of the validity of the determined kOH. TBEP oxidation rates were similar in the surface waters tested. Substantial TCEP oxidation in the model surface water required a significant increase in H2O2.

Keywords: organophosphate esters, ultraviolet, ozone, hydroxyl radical, hydrogen peroxide, free chlorine

Introduction

Recent surveys of synthetic organic compounds in wastewater receiving streams of Arkansas and Kansas found chlorinated and non-chlorinated tri alkyl phosphates (TAPs) at concentrations ranging from 0.03 to 27 μg/L (1, 2). In addition, highway runoff can be a source of TAPs in the environment as seven chlorinated and non-chlorinated alkyl-phosphates were recovered from roadside snowbanks in Sweden (3). While the eco-toxic and human health effects of aqueous TAPs are not clear, California has listed the chlorinated-TAP, tris(2-chloroethyl) phosphate (TCEP, CAS No. 115-96-8), among carcinogens and reproductive toxins since 1992 (4).

Chlorinated-TAPs have been shown to resist biodegradation, chlorination, and ozonation in treated waters (5, 6). With their resistance to conventional water treatments and relative abundance in the hydrosphere, it is apparent that alternative treatments for control of aqueous TAPs require investigation. Sampling before and after granular-activated-carbon filtration of drinking water has shown significant removal of TAPs at full-scale treatment plants (7, 8). However, the application of other advanced water treatments, specifically geared toward the chemical destruction of TAPs in-situ warrants examination.

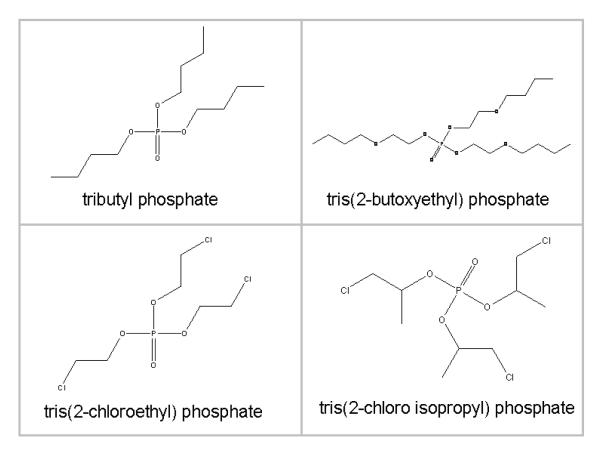

Hydroxyl radical, with its relatively high redox potential (2.8 V), is often the oxidant of choice for engineered remediation of waters contaminated with trace anthropogenic organic compounds. The potential for •OH-formation in UV irradiated waters containing the oxidant H2O2, has led to the design and implementation of UV-H2O2 for oxidation of unwanted organics, at full-scale water treatment plants (9,10). In a previous study of •OH-oxidation of TCEP, the advanced oxidation process (AOP), O3/H2O2, more efficiently degraded the aqueous TAP when compared to O3 alone (11). The reported work assesses the potential of AOPs for remediation of surface waters containing TAPs. The advanced oxidation kinetics of TCEP were compared to a heavier molecular weight, chlorinated TAP, tris(2-chloroisopropyl) phosphate (TCPP, CAS No. 13674-84-5), and two non-halogenated TAPs, tributyl phosphate (TBP, CAS No. 126-73-8) and tris(2-butoxyethyl) phosphate (TBEP, CAS No. 78-51-3). Their second-order rates of reaction with •OH (kOH) were assessed via a UV-H2O2 competition kinetics method (12). These rate constants were compared to assess the impact of alkyl-chain structure on the •OH reaction rates. Figure 1 provides a visual comparison of the structural differences among the studied TAPs.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of TBP, TBEP, TCEP, and TCPP.

A significant application of empirically-determined kOH is for the modeling of contaminant oxidation in natural waters via engineered, •OH-generating processes. Additionally, using previously established UV/H2O2-kinetic models allows for validation of empirically-determined kOH, by comparing the ”goodness-of-fit” for kOH-based predictive models to observed kinetic data. Therefore, for the discussed work, the derived kOH was used to predict TAP oxidation in surface water for given solution conditions. The contaminated surface water was treated via sequential addition of a chemical oxidant, H2O2 or NaOCl, and a measured UV fluence (mJ/cm2). Previous work has highlighted the fast rate of •OH formation in acidic free chlorine (HOCl) solutions irradiated with monochromatic, 254 nm UV (13). TCEP and TBEP serve as model surface-water-TAPs, and to ensure an accurate prediction of their oxidation rates, the derived kOH for these contaminants were validated using an alternative •OH-generating advanced oxidation process, O3-H2O2.

Methods

Chemicals

Nitrobenzene (NB) was supplied by Fluka (Buchs, Switzerland; 97%), while TCEP, TBEP and TBP were acquired from ACROS (Geel, Belgium; 97%, 94%, and 99%, respectively). TCPP was purchased from Wako Chemicals (Osaka, Japan; purity unknown; see discussion in Analysis below). The 30% H2O2 solution was procured from Fisher Chemical (Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Hexachlorobenzene (HCB, >99%) was produced by Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA, USA). Dichloromethane (99.9%), methanol (HPLC-grade) and chloroform (HPLC-grade with 50 ppm pentene-preservative) were supplied by Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ). All chemicals were used as purchased. Dilute solutions were prepared in lab-grade deionized water (HYDRO Ultrapure, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA).

UV-H2O2 competition kinetics

The bench-scale quasi-collimated beam apparatus contained 4 low-pressure (LP) Hg UV lamps (General Electric #G15T8) emitting primarily at a wavelength of 253.7 nm. Calculating the UV fluence (mJ cm-2) applied to an aqueous solution required a measurement of the UV irradiance (mW cm-2) incident to the surface. A radiometer (IL 1700, SED 240/W, International Light, Peabody, MA), with a UV detector calibrated to 254 nm, was used to measure incident irradiance. Measures of incident irradiance varied between exposures due to changes in lamp condition with age and relative placement of the irradiation vessel. Therefore, the radiant exposure, or UV fluence, was averaged over the entire solution volume by multiplying an incident irradiance by factors accounting for the divergence of the collimated beam, reflection at the water surface, variation in the irradiance over the surface of the solution, and photon absorption with depth in the water column (14). In this way, multiple irradiations with variable exposure conditions can be compared.

UV-irradiated, deionized-water solutions were spiked with NB and a TAP to 5 μM (of each), H2O2 up to 50 mg/L, and continuously mixed. Nitrobenzene is an ideal reference compound for UV competition kinetics studies due to the compound’s resistance to direct photolysis and relatively rapid rate of reaction with •OH (12, 15, 16). The total solution volume before exposure was 130 ml, with 30 ml samples taken from the bulk solution (the change in average irradiance caused by the reduction in solution volume and subsequent decrease in time required to reach the desired UV fluence were accounted for by recalculating the required time to reach subsequent UV fluences). Each 30 ml sample was placed into a 40 ml borosilicate vial, containing 1 ml of dichloromethane, with a PTFE-lined cap. The borosilicate vials were mixed for 15 minutes on a rotary, end-over-end vial tumbler. 250 μL of dichloromethane was removed for TAP and NB concentration analysis.

O3-H2O2 competition kinetics

Ozone was supplied by an EFFIZON Ozone Generator (WEDECO) utilizing compressed medical-grade oxygen. Deionized water solutions of H2O2 and TCEP or TBEP were dosed with ozone via addition of a measured volume of an ozone-saturated solution (40 mg/L as O3). The molar ratio of H2O2 to O3 was consistently 1.2; to observe increased TAP and NB oxidation, initial concentrations of H2O2 (0.38 – 6.37 mg/L) were increased with proportional increases in O3 (0.45 – 7.5 mg/L). Ozone concentrations were measured using the Indigo-Colorimetric method as described in Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 19th ed (17). After a controlled period of oxidation, sodium thiosulfate (24.8 mg/mL) was added to quench the residual O3. A liquid-liquid extraction method, as previously described, was used to extract the analytes from the aqueous sample.

Model surface water irradiations

A model surface water was prepared by first adding extracts of Suwanee River Humic Acid (0.0256 g) and Alginic Acid (0.0532 g, International Humic Substances Society, http://www.ihss.gatech.edu) to 100 mL of 2.5 μM NaOH solution. The final “surface water” was prepared by mixing 0.09 g of NaHCO3, 600 μL of 1 g/L NO3-, 2 mL of 1 g/L HPO42-, and 20 mL of the buffered organic acid solution in 2 L of deionized water. Solution pH was adjusted using 0.16 N phosphoric acid (to pH 6.8). Dissolved organic carbon and inorganic anion concentrations are reported in Table 1. Significant •OH-scavengers in this surface water (CO32-, HCO3-, and DOC) have well understood •OH scavenging rates, such that the photooxidation of TAPs in this matrix could be predicted via established equations governing the rate of •OH formation under UV/H2O2-conditions.

Table 1.

Concentrations of DOC and inorganic anions in the model surface water.

| DOC, mg/L | NO3-, mg/L | HCO3-, mg/L | PO43-, mg/L |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.0 | 0.3 | 30 | 1.0 |

UV irradiations were conducted as previously described. TBEP, or TCEP, was added prior to irradiation (TAP0 = 50 μg/L). Analyte extraction involved rapid vortexing of the entire irradiated solution volume (150 mL) with 1 mL of chloroform in a 250 mL centrifuge tube. A 250 μL aliquot of chloroform was taken for TAP concentration analysis.

Analysis

The analytes were separated from the solvent (dichloromethane or chloroform) with gas chromatography followed by quadropole-MS detection (Shimadzu, Japan). After injection of 1-2 μL, the column temperature was held at 50° C for 4.5 minutes; subsequent oven-temperature ramping increased the column temperature from 50 to 300° C over 13 minutes. Single-ion-monitoring was used to assess the detector response to the analytes. With regards to the purity of the TCPP standard, two peaks were detected when TCPP was the lone analyte. However, the second peak was consistently 5 times smaller (and their relative retention times were consistent), therefore only the largest peak was used for response assessment. Andresen et al. also encountered multiple peaks for their technical grade TCPP (different supplier from the TCPP used in this study) and similarly reported the largest peak for quantification (18). The mass spectra for both peaks were similar, and it was assumed that the 2nd-order •OH reaction rates are also similar for these potential isomers.

H2O2 residuals were measured using the “I3” method (19). Free chlorine residuals were analyzed according to the DPD Colorimetric method (17).

Results and Discussion

UV photosynthesized-•OH oxidation in lab-grade water

The molar absorption coefficients, ε (M-1cm-1), were measured for all 4 compounds by diluting the neat standard in MeOH and measuring the solution absorbance (minus the background absorbance of MeOH) over the range of 200 – 400 nm (see Supporting Information for measured molar absorption coefficients) with a Cary UV-Vis Spectrophotometer (Varian, Inc., Palo Alto, CA). Ideally, the absorbance spectra would have been measured in water rather than MeOH, due to potential differences in solute-solvent interactions. However, the poor UV-C absorbance of the studied TAPs required dissolution of solute at concentrations well above reported water solubility. Direct photolysis of TBEP, TBP, TCEP, and TCPP was insignificant at the applied UV fluences due to the almost negligible photon absorption (λ=254nm) by these alkyl-phosphates.

In solutions where NB and the tri alkyl phosphate are the only competitors for photosynthesized •OH, the linear correlation between the observed decay rate of [NB] and [TAP] represents the ratio of kOH-NB to kOH-alkyl-phosphate (12, 15). Figure 2 illustrates the log(ln)-linear decrease in the TAPs relative to NB in UV-H2O2 treated deionized water solutions of TBP & NB, TBEP & NB, TCEP & NB, and TCPP & NB.

Figure 2.

The linear-correlations between the concentrations of tri butyl phosphate (TBP), tri chloroethyl phosphate (TCEP), tri butoxyethyl phosphate (TBEP), tri chloropropyl phosphate (TCPP), and NB. •OH was the product of H2O2 photolysis under LP UV. Corresponding kOH listed in units of M-1s-1.

The addition of a Cl-atom on the alkyl-chain (TCEP) significantly reduces H-atom availability relative to TBP and TBEP. Along with halogenation of the alkyl chain, the number of carbons and additional hetero-atoms (O) on the chain also seems to affect the rate of •OH attack. The chain structure with the most carbons (TBEP) had the fastest rate of reaction. However, TCPP has one more carbon on each chain than TCEP, yet scavenged •OH at a slower rate, most likely due to the influence of an additional function group (-CH3) at the alpha-carbon on TCPP.

Ozone synthesized •OH oxidation in lab grade water

An additional •OH-generating process, O3-H2O2, was used to measure the kOH and validate the values determined using UV-H2O2. TCEP and TBEP were selected for kOH validation as their respective rate constants are subsequently used to predict •OH oxidation in surface water (below). In ozonated aqueous solutions, the presence of H2O2 leads to accelerated decomposition of O3 to •OH. As the rates of O3-reactivity with NB (0.09 M-1s-1; (20)), TCEP (0.3 min-1 in 9 mg/L O3 solution; (11) ), and TBEP (no observed oxidation for the applied ozone Ct) are negligible relative to the reaction rate of H2O2 with O3 (kO3,HO2-=2.8±0.5×106 M-1s-1;(21)), the assumptions underlining UV-H2O2 competition kinetics (no decay from UV — or ozone alone) are also valid for O3-H2O2 competition kinetics. Figure 3 presents the correlations between [NB] and [TCEP] or [TBEP] in ozonated solutions of H2O2.

Figure 3.

The linear-correlations between the concentrations of TCEP/TBEP and NB. •OH was the product of O3-H2O2.

The observed linear correlations between NB and TBEP or TCEP oxidation in ozonated H2O2-solutions were used to calculate kOH,O3 for TBEP and TCEP. Figure 4 presents the experimentally determined kOH,UV and kOH,O3 for both TCEP and TBEP.

Figure 4.

A comparison of kOH,UV and kOH,O3 for TCEP and TBEP. Error bars present the upper and lower limits on the 95% confidence interval for the linear estimation of kOH.

For both compounds, the UV-H2O2 competition kinetics method predicts a slightly higher rate of reaction with •OH, relative to O3-H2O2. To test the homogeneity of the competition-kinetics data from UV-H2O2 and O3-H2O2 a multivariate linear regression model

| (1) |

was applied to the combined UV-H2O2, O3-H2O2 dataset. For this model, z is a dummy variable equal to 1 or 0 depending on whether the data point belongs to the UV-H2O2 or O3-H2O2 data set. A single regression model can be fit to a combined UV-H2O2, O3-H2O2 dataset when β2 = β3 = 0 (hypothesis of coincidence). Table 2 lists the parameter estimates and standard errors from the multivariate regression models for TCEP and TBEP oxidation.

Table 2.

Parameter estimates for multiple regression models (Equation 1) of TCEP and TBEP oxidation, in competition with NB for •OH.

| TCEP | TBEP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | Estimate | Standard Error | Estimate | Standard Error |

| β 1 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 2.61 | 0.14 |

| β 2 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.32 | 0.15 |

| β 3 | 0.04 | 0.03 | -0.17 | 0.38 |

For both TCEP and TBEP, only β1 is significantly non-zero (α=0.05 for TCEP and α=0.01 for TBEP). Therefore a single linear regression model can be used to determine kOH from the combined datasets of each contaminant. Table 3 summarizes the determined second-order •OH rate constants for TBEP and TCEP.

Table 3.

2nd-order reaction rates (kOH) of TBEP and TCEP with •OH, determined using both UV-H2O2 and O3-H2O2 competition kinetics.

| kOH, M-1s-1 | |

|---|---|

| TBEP | 1.03±0.38 × 1010 |

| TCEP | 5.60±0.21 × 108 |

TBEP and TCEP: advanced oxidation in a model surface water

The measured •OH rate constants for TBEP and TECP were utilized to predict the degradation of the contaminants under two distinct UV-based AOPs: UV-H2O2 and UV-HOCl (13). Theoretical first-order rate constants, k1 (s-1), for TCEP and TBEP degradation, in a water matrix treated with an AOP, can be predicted using established equations governing the simultaneous formation and scavenging of photosensitized •OH (22-24). The steady-state concentration of •OH ([OH]SS) is the ratio of the rate of •OH formation, for a given set of UV-irradiation and initial oxidant conditions (H2O2 or HOCl), to the sum of the products of •OH-reactants and their reaction rates in the given water matrix (total •OH scavenging). The predicted k1 for TCEP and TBEP is the product of their derived second-order •OH reaction rates and [OH]SS. However, in UV-irradiated free chlorine solutions, the total •OH-scavenging can be significantly affected by pH; as the ratio of OCl- to HOCl increases with pH so does the fraction of [OH]ss that reacts with unphotolyzed free chlorine hypochlorite ion (25). Modifying the conventional equation for [OH]ss to account for free chlorine speciation yields Equation 2.

| (2) |

In Equation 2, ΦHOCl-->OH is the quantum yield (λ=254nm) of HOCl to •OH (1.4 mol Es-1; (13)), I0 is the incident irradiance (Es L-1 s-1), fHOCl is the fraction of UV light absorbed by HOCl, b is the optical pathlength (cm), εHOCl is the molar absorption coefficient for HOCl (M-1cm-1, λ=254nm; (13)), C1 … Cn are the concentrations of species 1 through n (M), and kOH,HOCl(8.46×c104 M-1s-1; (13)) and kOH,OCl- (8.0×109 M-1s-1; (26)) are the second-order •OH rate constants for HOCl and OCl-. While OCl- photolysis products include •OH (26), consideration of OCl- in the rate of •OH formation term (numerator in Equation 2) would not significantly impact [OH]SS (when pH<7.5 (pKa), and particularly for water treatment applications where HOCl is the desired residual disinfectant) as its ΦOCl->OH (λ=254 nm) is significantly less (0.278 mol Es-1; (27)) than that of its conjugate acid HOCl.

In order to completely characterize the total •OH-scavenging for bench-scale UV-H2O2 or UV-HOCl treatments of surface water contaminated with either TBEP or TCEP, a model surface water with known •OH scavengers. As previously discussed, this surface water was composed of extracts of Suwanee River Humic Acid and Alginic Acid (kOH,DOC = 2.5 × 104 L/mg-C s-1), and salts of nitrate, phosphate, and bicarbonate (kOH,CO3 = 3.9 × 108 M-1 s-1, kOH,HCO3 = 8.5 × 106 M-1 s-1) dissolved in lab-grade water (pH 6.8) (16, 28). The significant competitors for photosynthesized •OH in the prepared surface water were the spiked TAP and unphotolyzed oxidant, bicarbonate and carbonate ions, and the dissolved organic carbon. Figure 5, Figure 6, and Figure 7 provide qualitative comparisons and the degree-of-fit of the predicted to the observed TAP (TAP0 = 50 μg/L) in model surface water treated with either UV-HOCl or UV-H2O2. For all cases, the predicted k1 (s-1) is within the confidence limits (α=0.05) of the estimate for k1 determined by fitting a first order exponential decay function to the observed data.

Figure 5.

Observed TBEP (□) and TBEP predicted using [OH]SS-model (—) in LP UV irradiated model surface water. Error bars present range of TBEP concentrations (2 replicates) for a given fluence. Inset table compares the predicted 1st-order rate constant, k1, to the estimate for k1 determined by fitting a 1st-order exponential decay α = function to the observed data. Upper and lower limits describe confidence interval (α = 0.05) for k1 best-fit.

Figure 6.

Observed TBEP (□) and TBEP predicted using [OH]SS-model (—) in LP UV irradiated model surface water. Inset table compares the predicted 1st-order rate constant, k1, to the estimate for k1 determined by fitting a 1st-order exponential decay function to the observed data. Upper and lower limits describe confidence interval (α = 0.05) for k1 best-fit.

Figure 7.

Observed TCEP (□) and TCEP predicted using [OH]SS-model (—) in LP UV irradiated model surface water. Error bars present range of TCEP concentrations (2 replicates) for a given fluence. Inset table compares the predicted 1st-order rate constant, k1, to the estimate for k1 determined by fitting a 1st-order exponential decay function to the observed data. Upper and lower limits describe confidence interval (α = 0.05) for k1 best-fit.

For the given oxidation conditions, a similar reduction in TBEP (from 50 μg/L to 30, 15-18, 12, and 7 μg/L after 250, 500, 750 and 1000 mJ/cm2, respectively) was observed in the model surface waters treated with UV-HOCl or UV-H2O2. For purposes of comparison, a UV/H2O2-AOP at Andijk Water Treatment Plant (The Netherlands) has been designed to remove 80% of an organic pesticide, atrazine, in lake water with 80% UV254-transmittance (UVT), with a design UV fluence of 1000 mJ/cm2 (10).

Despite yielding higher levels of •OH per mole of photons absorbed (13), the UV-HOCl process required a slightly higher fraction of the applied UV light (fH2O2 < fHOCl, with f determined according to previously published methods (24)) to be absorbed by the oxidant in order to achieve the same rate of TBEP oxidation as seen with UV-H2O2 . As previously discussed, at near-neutral pH the kOH of the target contaminant must be similar or higher to kOH of OCl- (a scavenger) in order for the UV-HOCl process to be an effective contaminant barrier.

When TCEP is the target contaminant, UV-HOCl is not an effective treatment. In surface water spiked with TCEP, little to no TCEP degradation was observed in the range of applied UV fluences (up to 1000 mJ/cm2) regardless of how much NaOCl was added prior to UV irradiation. It has been previously demonstrated that at neutral pH, increasing the initial concentration of free chlorine leads to a decrease in the first-order, fluence-based rate constant for oxidation of an organic with a slower rate of reaction with •OH than OCl- (25), as OCl- accounts for an increasing majority of •OH-scavenging. For UV-H2O2 to be an effective process for oxidation of TCEP, a significant increase in the initial oxidant concentration and subsequent fraction of the applied UV light absorbed by H2O2 is required. As illustrated in Figure 7, a 50 percent reduction in TCEP is possible at a UV fluence of 1000 mJ/cm2 in the presence of ∼50 mg/L H2O2. The disparate rates of reaction with •OH for the TAPs, competitive radical scavenging by natural organic matter, carbonate species, and unphotolyzed oxidant concentrations are all parameters that impact the selection of chemical oxidant to be photolyzed, and subsequently, the TAP-removal-efficiency with UV-AOP.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Duke University Superfund Basic Research Center (NIH/NIEHS P42-ES-010356).

Footnotes

Supplementary Information Figure SI-S1 presents the measured molar absorption coefficients for TBP, TBEP, TCPP, and TCEP.

Brief The efficacy of UV-advanced-oxidation processes for degrading tri-alkyl phosphate esters in treated source waters is described with respect to empirically-determined second-order reaction rates with •OH.

Contributor Information

Michael J. Watts, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32310 USA

Karl G. Linden, Department of Civil, Environmental and Architectural Engineering 428 UCB Boulder, CO 80309 University of Colorado-Boulder, USA Tel.: 303-492-4798 Fax: 303-492-7317

References

- (1).Haggard BE, Galloway JM, Green WR, Meyer MT. Pharmaceuticals and Other Organic Chemicals in Selected North-Central and Northwestern Arkansas Streams. Journal of Environmental Quality. 2006;35:1078–1087. doi: 10.2134/jeq2005.0248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Lee CJ, Rasmussen TJ. Occurence of organic wastewater compounds in effluent-dominated streams in Northeastern Kansas. Science of The Total Environment. 2006;371:258–269. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2006.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Marklund A, Andersson B, Haglund P. Traffic as a source of organophosphorous flame retardants and plasticizers in snow. Environmental Science and Technology. 2005;39:3555–3562. doi: 10.1021/es0482177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).CAEPA . In: Chemicals Known to the State to Cause Cancer or Reproductive Toxicity. CAEPA, editor. Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Westerhoff P, Yoon Y, Snyder S, Wert E. Fate of Endocrine-Disruptor, Pharmaceutical, and Personal Care Product Chemicals during Simulated Drinking Water Treatment Processes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005;39(17):6649–6663. doi: 10.1021/es0484799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Meyer J, Bester K. Organophosphate flame retardants and plasticisers in wastewater treatment plants. Journal of Environmental Monitoring. 2004;6:599–605. doi: 10.1039/b403206c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Stackelberg PE, Gibs J, Furlong ET, Meyer MT, Zaugg SD, Lippincott RL. Efficiency of conventional drinking-water-treatment processes in removal of pharmaceuticals and other organic compounds. Science of The Total Environment. 2007;377:255–272. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2007.01.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Andresen J, Bester K. Elimination of organophosphate ester flame retardants and plasticizers in drinking water purification. Water Research. 2006;40:621–629. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2005.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Cotton CA, Collins JR. Dual purpose UV light: Using UV light for disinfection and for taste and odor oxidation. American Water Works Association WQTC; Denver, CO: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Kruithof JC, Kamp PC, Martijn BJ. UV/H2O2 Treatment: A Practical Solution for Organic Contaminant Control and Primary Disinfection. Ozone: Science and Engineering. 2007;29:273–280. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Echigo S, Yamada H, Matsui S, Kawanishi S, Shishida K. Comparison between O3/VUV, O3/H2O2, VUV and O3 Processes for the Decomposition of Organophosphoric Acid Triesters. Water Science and Technology. 1996;34(9):81–88. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Einschlag F. S. Garcia, Carlos L, Capparelli AL. Competition kinetics using the UV/H2O2 process: a structure reactivity correlation for the rate constants of hydroxyl radicals toward nitroaromatic compounds. Chemosphere. 2003;53(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(03)00388-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Watts MJ, Linden KG. Chlorine Photolysis and Subsequent *OH Radical Production During UV Treatment of Chlorinated Water. Water Research. 2007;41(13):2871–2878. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2007.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Bolton JR, Linden KG. Standardization of Methods for Fluence (UV Dose) Determination in Bench-Scale UV Experiments. Journal of Environmental Engineering. 2003;129(3):209–215. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Shemer H, Sharpless CM, Elovitz MS, Linden KG. Relative Rate Constants of Contaminant Candidate List Pesticides with Hydroxyl Radicals. Environmental Science and Technology. 2006;40(14):4460–4466. doi: 10.1021/es0602602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Buxton GV, Greenstock CL, Helman WP, Ross AB. Critical-Review of Rate Constants for Reactions of Hydrated Electrons, Hydrogen-Atoms and Hydroxyl Radicals (.Oh/.O-) in Aqueous-Solution. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data. 1988;17(2):513–886. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Eaton AD, Clesceri LS, Greenberg AE. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater. 19th ed American Public Health Association; Washington, DC: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Andresen JA, Grundmann A, Bester K. Organophosphorus flame retardants and plasticisers in surface waters. Science of The Total Environment. 2004;332(1-3):155–166. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2004.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Klassen NV, Marchington D, McGowan HCE. H2O2 Determination by the I-3(-) Method and by KMnO4 Titration. Analytical Chemistry. 1994;66(18):2921–2925. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Hoigne J, Bader H. Rate Constants of Reactions of Ozone with Organic and Inorganic-Compounds in Water .1. Non-Dissociating Organic-Compounds. Water Research. 1983;17(2):173–183. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Staehelin J, Hoigne J. Decomposition of Ozone in Water - Rate of Initiation by Hydroxide Ions and Hydrogen-Peroxide. Environmental Science & Technology. 1982;16(10):676–681. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Glaze WH, Lay Y, Kang JW. Advanced Oxidation Processes - a Kinetic-Model for the Oxidation of 1,2-Dibromo-3-Chloropropane in Water by the Combination of Hydrogen-Peroxide and UV-Radiation. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research. 1995;34(7):2314–2323. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Rosenfeldt EJ, Linden KG. Degradation of endocrine disrupting chemicals bisphenol A, ethinyl estradiol, and estradiol during UV photolysis and advanced oxidation processes. Environmental Science & Technology. 2004;38(20):5476–5483. doi: 10.1021/es035413p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Crittenden JC, Hu SM, Hand DW, Green SA. A kinetic model for H2O2/UV process in a completely mixed batch reactor. Water Research. 1999;33(10):2315–2328. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Watts MJ, Rosenfeldt EJ, Linden KG. Comparative OH radical oxidation using UV-Cl2 and UV-H2O2 processes. Journal of Water Supply: Research and Technology-AQUA. 2007;56(8):469–477. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Nowell LH, Hoigne J. Photolysis of Aqueous Chlorine at Sunlight and Ultraviolet Wavelengths-II. Hydroxyl Radical Production. Water Research. 1992;26(5):599–605. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Buxton GV, Subhani MS. Radiation Chemistry and Photochemistry of Oxychlorine ions II; Photodecomposition of Aqueous Solutions of Hypochlorite Ions. Journal of the Chemical Society. Faraday Transactions I. 1972;68:958–969. [Google Scholar]

- (28).Larson RA, Zepp RG. Reactivity of the carbonate radical with aniline derivatives. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 1988;7(4):265–274. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.