Summary

We evaluated the clinical and angiographic results of endosaccular treatment with Guglielmi detachable coils (GDCs) in 19 cases of cavernous internal carotid artery (ICA) aneurysms. The size of the aneurysms ranged from 10 to 30 mm (mean 18.4 mm) and neck size ranged from 2 to 15 mm (mean 6.7mm). Intraluminal thrombosis was found in ten cases. Main presenting symptoms were related to mass effect in 17 cases including cranial nerve palsy, headache and vomiting.

On initial GDC embolisation, total occlusion was obtained in two cases, subtotal in eight, and incomplete in nine. In two cases with incomplete occlusion, parent arteries were occluded with balloons or GDCs during or just after the procedure because of underlying diseases. A higher rate of initial occlusion was obtained in smaller and non-thrombosed aneurysms. Symptoms resolved or improved in all cases except one after initial treatment. No complication occurred related to the procedure. Follow-up angiography was obtained in 15 cases among which ten cases (66.7%) showed luminal recanalisation. Symptoms recurred in one case with luminal recanalisation. Incidence of recanalisation was similar in both large and giant aneurysms but higher in the thrombosed than non-thrombosed group. Retreatment was done in five cases with success.

In conclusion, although embolisation of cavernous ICA aneurysms with GDCs was safe and effective in relieving symptoms, the incidences of initial incomplete occlusion and follow-up recanalisation were high. Therefore, we think judicious selection of the cases is necessary for endosaccular GDC embolisation in cavernous ICA aneurysms.

Key words: aneurysm, cavernous sinus, aneurysm, embolisation, GDC

Introduction

Treatment of cavernous internal carotid artery (ICA) aneurysms by direct surgical approach is difficult because of potential risk of profuse bleeding and cranial neuropathy 1; For these difficult aneurysms, surgical ligation or endovascular occlusion of the parent artery has long been performed as an effective and safe alternative2-6. But even with meticulous pre-occlusion evaluation for possible ischemic complications, small group of patients suffered from neurologic complications after permanent occlusion of the parent artery4,8. Selective occlusion of the aneurysm sacs with detachable balloons was tried, but it revealed higher complication rate compared with occlusion of the parent artery3-5,8.

Since the advent of detachable platinum coils, many surgically difficult or inoperable aneurysms can be treated safely and effectively by endovascular route 9,10. Treatment with detachable coils can allow surgically difficult cavernous ICA aneurysms to be eliminated without sacrificing the parent artery. However, this technique still represents a challenge to interventionists because those aneurysms are usually large in size and have a high incidence of luminal thrombosis1,11. Another concern regarding selective occlusion of the aneurysms with platinum coils is that mass-related symptoms may not improve or even be aggravated because aneurysms treated with coils may not regress in size and coils in the aneurysm may exacerbate the pressure effect.

We attempted to occlude cavernous ICA aneurysms with Guglielmi detachable coils (GDCs) without sacrificing the parent artery and evaluated on angiography the results of GDC treatment according to the size of aneurysms and the presence of intrasaccular thrombosis.

Patients and Methods

Nineteen cases of cavernous ICA aneurysms treated with GDCs were selected for analysis. Medical records and angiograms were analysed retrospectively. The aneurysms with broad necks that did not seem to hold the coil mass were considered not suitable for selective coil occlusion and were excluded.

Among 19 cavernous ICA aneurysms in which endosaccular aneurysm occlusion with detachable coils was attempted, 17 aneurysms were treated preserving the parent artery. In the remaining two cases the parent arteries were occluded during or just after the procedure because the aneurysms were occluded incompletely and the underlying vascular pathologies were not corrected. One case was an aneurysm with a carotid cavernous fistula and the other was with an ICA dissection. They were excluded from the evaluation of symptom change after treatment and from the follow-up evaluation.

The aneurysm size ranged from 10 to 30 mm (mean 18.4 mm) and neck size ranged from 2 to 15 mm (mean 6.7 mm) on angiogram. Fourteen aneurysms were large in size (10 to 25 mm), five were giant (25 mm and over), and none were small (less than 10 mm). Sixteen cases had large necks (over 4 mm) and three cases had small necks. Intraluminal thrombus was found in ten cases.

The main presenting symptoms were diplopia or other cranial nerve symptoms in 14 cases, headache in two, nausea and vomiting in one. In one case the aneurysm was found incidentally and in another case, the aneurysm developed as a complication of a transsphenoidal hypophysectomy. Subarachnoid haemorrhage accompanied in one case with diplopia.

Percentage occlusion of the aneurysm lumen was analysed on initial angiograms. Results of initial GDC treatment were divided into three groups based on the occlusion rate of the lumen: total, 100%; subtotal, 95-99%; and incomplete, under 95%. We compared the occlusion rate between large and giant aneurysms and between thrombosed and non-thrombosed aneurysms. Statistical analysis was not performed because the number of the patients was not large enough.

Follow-up angiograms were taken in 15 patients with a period extending from four months to five years (mean: 11.9, median: 7 months). We routinely perform the first scheduled follow-up angiography six months after the procedure. Aneurysmal lumen recanalisation was evaluated on follow-up angiograms. We compared the incidence of recanalisation between large and giant aneurysms and between thrombosed and non-thrombosed aneurysms. Patterns of coil mass changes were categorised into two: coil compaction and coil migration. Migration was defined as the entire coil mass moving inside the aneurysm, whereas compaction as a shrinkage of the coil mass. Symptom changes were evaluated after initial occlusion and during follow-up period.

Results

Anatomical and clinical results of our treatment were summarised in table. Among 17 cases in which parent arteries were preserved successfully, we achieved total to subtotal occlusion (95% plus) in ten cases (52.6%) (figure 1). Seven cases were occluded incompletely (less than 95%). Among 14 large aneurysms, nine (64.3%) were occluded more than 95% whereas only 1 aneurysm was among five giant aneurysms (20%). For thrombosed aneurysmsfour out of ten (40%) were occluded more than 95%, whereas six out of nine (66.7%) were in non-thrombosed aneurysms.

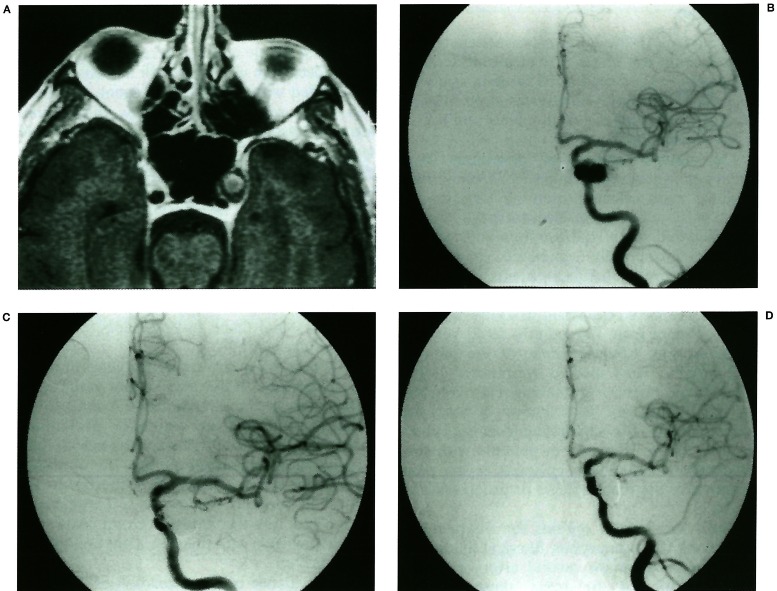

Figure 1.

Non-recanalisation. A gadolinium enhanced MR image (A) shows an aneurysm with peripheral thrombosis in the left cavernous sinus. Left carotid angiogram (B) reveals an aneurysm in the cavernous portion. Small area of the neck is filling after initial coil embolisation (C). Six months follow-up angiogram (D) shows no change.

Symptoms of cranial nerve compression resolved or improved in 11 cases out of 12 after initial treatment (no change in one, slightly improved in two, improved in seven and resolved in two). Other symptoms such as headache, nausea and vomiting, or neck stiffness also resolved after initial treatment. No immediate or delayed complication occurred related to the procedure.

Among 15 cases in which follow-up angiograms were available, ten cases (66.7%) showed luminal recanalisation. The extent of luminal recanalisation ranged from 10% to 30% of the initial aneurysm size. The incidence of recanalisation was 75% (3/4) in giant aneurysms and 63.6% (7/11) in large aneurysms. Five out of six (83.3%) thrombosed aneurysms recanalised on follow-up angiogram, whereas five out of nine (55.6%) non-thrombosed aneurysms did. Predominant migration occurred in three cases (figure 2) and compaction in the remaining seven cases (figure 3).

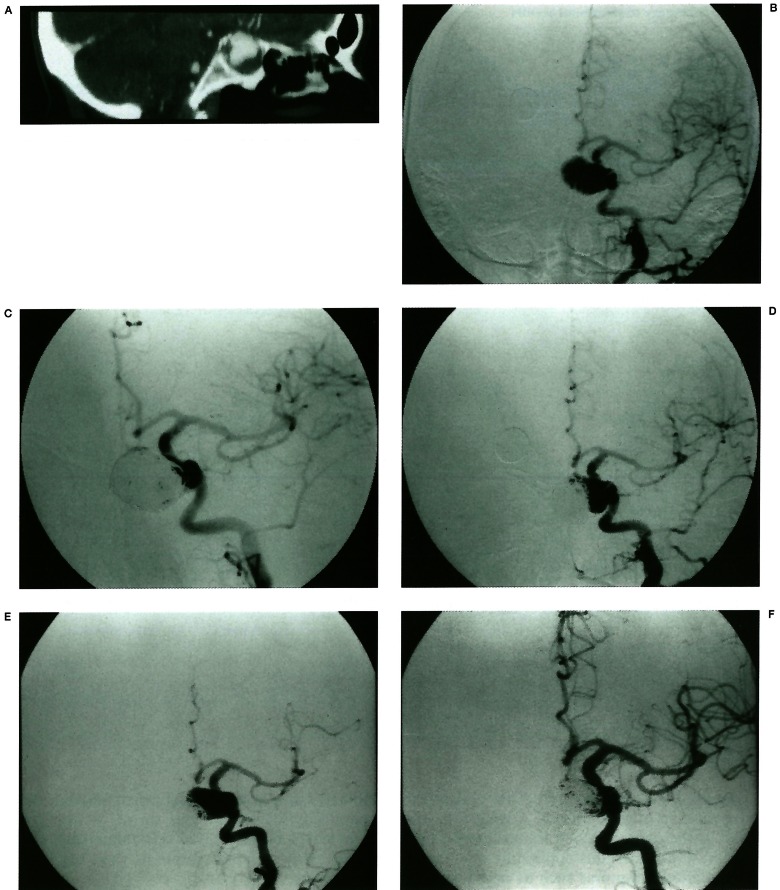

Figure 2.

Migration of coil mass with luminal recanalisation. A reformatted CT image (A) shows an aneurysm occupying the sphenoid sinus with peripheral thrombus. An angiogram (B) reveals a cavernous ICA aneurysm with medial direction. On initial post-embolisation, a small neck portion remains (C). The remaining neck portion enlarged on 6 months follow-up angiogram (D). No treatment was done at this time. Two years later, coil mass shows total migration with reopening of the whole lumen (E). After treatment with coils, angiogram (F) shows 95% luminal occlusion.

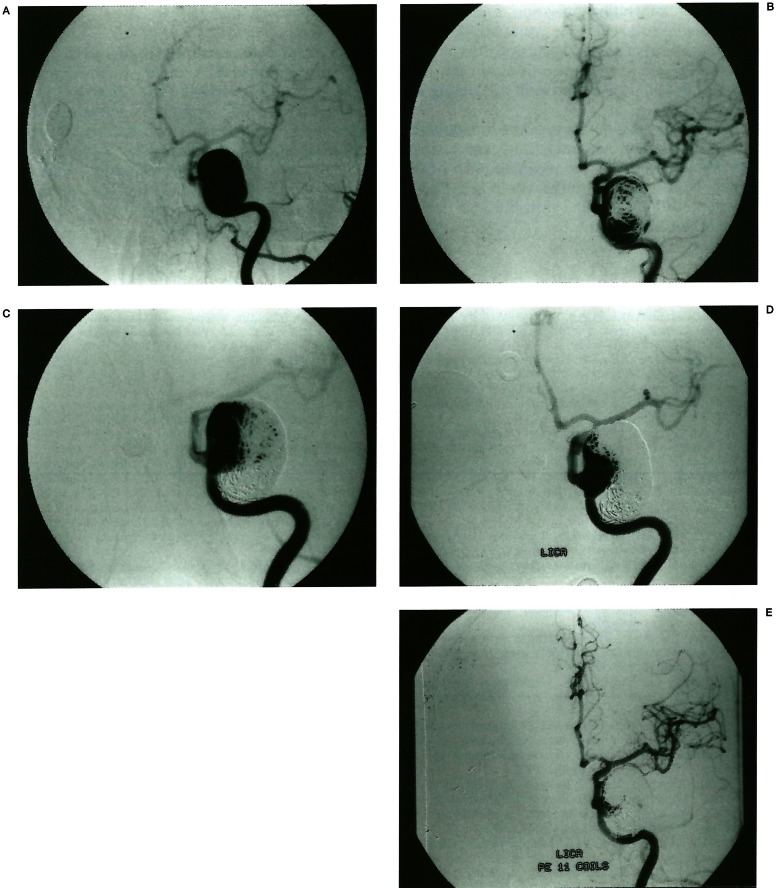

Figure 3.

Compaction of coil mass with luminal recanalisation. A giant aneurysm arising from C4-5 junction of ICA (A). There was no intraluminal thrombus. On initial embolisation, 70% of the lumen is occluded and her symptoms improved (B). Fifteen months follow-up angiogram (C) reveals coil mass compaction and luminal enlargement. Symptoms also recurred and retreatment was performed with success. Two and a half years later, angiogram (D) shows recurrent coil compaction. After retreatment with coils, 95% of the lumen is occluded (E).

All cases with coil migration occurred in the thrombosed group. Symptoms recurred in only one case with luminal recanalisation. In this patient the aneurysm was initially occluded by 70% and showed further coil compaction on follow-up. Retreatment was done three times with final achievement of 95% of occlusion and symptoms resolved (figure 3). In another four cases retreatment was performed successfully with more than 95% of luminal occlusion.

Discussion

Aneurysms of the intracavernous segment of ICA account for 3% to 5% of all intracranial aneurysms12. They tend to be large in size with 60% of all cavernous aneurysms large to giant in size1,11,13. Thrombosis of the aneurysm lumen is not uncommon.

The natural course of cavernous ICA aneurysm is generally benign2,12,14. Usually they produce mass effect, presenting with cranial nerve palsy or headache. Haemorrhage into the subarachnoid space is uncommon and may occur in intradurally extended aneurysms. Carotid cavernous fistula, epistaxis, or cerebral embolism rarely occurs 5,12. Linskey and colleagues 12 reported the result of follow-up without treatment from five months to 13 years in 20 aneurysms. Clinical course of the patients was variable. They showed symptom stabilisation, improvement or worsening. They concluded that therapeutic intervention is necessary only in large aneurysms arising from the anterior loop of the ICA and in patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage, epistaxis, severe pain, progressive ophthalmoplegia or progressive visual loss.

There are several options for treatment of cavernous ICA aneurysms. Surgical ligation of the ICA or common carotid artery has long been performed to treat these difficult aneurysms. Currently, endovascular occlusion of the parent artery with detachable balloons has replaced surgical ligation3,15. Occlusion of the parent artery resulted in complete obliteration of the aneurysm and subsequent thrombosis with symptomatic improvement and protection from bleeding3-6,8,15.

Although occlusion of the parent artery is considered an effective and safe procedure for unclippable aneurysms, it carries the risk of ischemic complications. Even though the patients tolerated balloon test occlusion prior to permanent arterial occlusion, neurological complications such as stroke or transient ischemic attack developed in about 10% of cases after arterial occlusion4-8.

Direct surgical approaches for clipping, aneurysmorrhaphy, or cavernous sinus trapping with saphenous vein graft have been described with favorable results 13,16. However, opening the cavernous sinus carries a higher rate of morbidity or mortality than balloon occlusion technique1.

Recently endovascular embolisation of the aneurysm with parent artery preservation has become available in selected cases. Aneurysmal lumen occlusion was tried with detachable balloons filled with solidification agent, but there was a high rate of complications. In addition, intraaneurysmal balloon occlusion is feasible only in a minority of large cavernous aneurysms, specifically those with narrow necks. After the detachable platinum coils became available, coils could be used instead of balloons for aneurysmal sac occlusion8. The coils have many advantages over detachable balloons in the endosaccular treatment of aneurysms. They include easy applicability, maneuverability, and retrievability. Additionally, the coils conform to the aneurysmal shape and exert less trauma on the vascular wall8,17,18.

However, there are some problems in treating cavernous ICA aneurysms with coils. Aneurysms in the cavernous ICA tend to be large in size and the incidence of luminal thrombosis is high1,11,13. This interferes with tight packing of the aneurysm lumen. The occlusion rate in our series is lower than the results reported in saccular aneurysms 19. Large aneurysms and non-thrombosed group showed a higher occlusion rate than the giant and thrombosed group.

The incidence of recanalization of the aneurysmal lumen on follow-up angiography was high (66.7%) in our series. This is significantly higher than the results of balloon occlusion procedure of the parent artery, in which almost all cases showed complete occlusion of the aneurysm. The recanalization rate was higher in giant aneurysm group and thrombosed group suggesting that the large size of the aneurysms and the high incidence of luminal thrombosis may have caused this result10,20.

Although the number of cases in our series is not sufficient to reach a conclusion, we consider that small or large aneurysms with small necks and without thrombus may be good candidates for endosaccular GDC embolisation. Aneurysms with giant size, luminal thrombi, or broad necks did not seem to be suitable for this technique.

For these aneurysms, parent artery occlusion may provide better results if the patients can tolerate the test occlusion. Recently new techniques have been developed such as a balloon-assisted remodeling technique or stenting. Anincreasing number of authors report effective treatment of broad neck aneurysms with GDC by using these techniques 21-23.

We believe these techniques would be useful in the treatment of cavernous carotid aneurysms because these aneurysms tend to be larger in size, have broad necks, are located proximally, and have large parent vessels, which allow easier manipulation of the equipment. These techniques may facilitate GDC embolisation of cavernous carotid aneurysms with parent artery preservation.

Table 1.

Summary of treatment results

| Case | Age/ Sex |

Presenting Symptoms |

Aneurysm size (mm) |

Thrombus | Initial occlusion (%) |

Follow-up reopening % |

Re-Tx / % occlusion |

Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F/55 | CN III, V palsy | 20 | - | 90 | 20 | +/91 | Improved |

| 2 | F/58 | Diplopia | 30 | - | 70 | 10 | +/97 | Improved |

| 3 | M/64 | CN III palsy | 23 | - | 95 | No change | - | Improved |

| 4 | M/27 | CN III palsy | 10 | - | 98 | 10 | - | Recovered |

| 5 | F/65 | Incidental | 27 | + | 90 | 30 | +/95 | No symptom |

| 6 | M/79 | Headache | 11 | + | 95 | No change | - | Improved |

| 7 | M/37 | Diplopia | 18 | + | 90 | NA | - | Improved |

| 8 | F/80 | CN III,V,VI palsy | 18 | + | 90 | 20 | - | SI improved |

| 9 | F/68 | CN VI palsy | 25 | + | 70/ICA occl. | NA | - | Excluded |

| 10 | F/82 | Diplopia | 14 | + | 70/ICA occl | NA | - | Excluded |

| 11 | F/69 | Diplopia | 14 | - | 95 | 10 | - | Recovered |

| 12 | F/73 | CN VI palsy | 12 | + | 95 | 30 | +/95 | Improved |

| 13 | F/57 | Nause & vomiting | 20 | - | 95 | No change | - | Recovered |

| 14 | F/85 | Diplopia | 10 | + | 100 | NA | - | Improved |

| 15 | F/38 | Headache | 25 | - | 90 | No change | - | Improved |

| 16 | F/63 | Visual field deficit | 35 | - | 95 | 30 | - | SL improved |

| 17 | F/72 | CN VI palsy | 15 | + | 90 | 20 | - | No change |

| 18 | F/52 | Diplopia | 10 | - | 95 | No change | - | Improved |

| 19 | F/47 | Iatrogenic | 11 | + | 100 | 15 | +/98 | No symptom |

|

Note: CN = cranial nerve; ICA = internal carotid artery; NA = not available; occl = occluded; Re-Tx = retreatment; sl. = slightly; ‘+’ = yes; ‘-’ = no | ||||||||

Another problem regarding the endosaccular treatment of cavernous ICA aneurysm with GDC is the mass effect of the aneurysm. Cavernous ICA aneurysms commonly manifest as mass-related symptoms such as ophthalmoplegia, retroorbital pain or trigeminal area pain and these account for nearly 80% of presenting symptoms5. Occlusion of the parent artery has been shown to be effective in alleviating the mass effect4,5. The aneurysm size usually decreased on follow-up imaging24,25.

With endosaccular occlusion, aneurysm size reduction was also reported in some cases26.However, it is not well established whether the aneurysms filled with coils shrink or not in a large series. Regardless of this aneurysmal size change, mass-related symptoms were reported to improve.

Halbach and colleagues 25 reported that mass-related symptoms were alleviated in 24 cases out of 26 intracranial aneurysms including 13 cavernous ICA aneurysms by endosaccular aneurysm occlusion using detachable balloons (23 cases) or coils (3 cases).

In our series, mass-related symptoms resolved or improved in most of the cases eventhough the aneurysms were occluded incompletely in some cases.

The mechanism for improvement of the mass effect is not well understood yet. Halbach and colleagues suggested the reduction of aneurysm size after endosaccular occlusion, resolving of edema around thrombus-containing aneurysms, or growth arrest of the aneurysms after treatment as the possible mechanisms. Another possible explanation for the improvement is by alleviating pulsation, a mass effect may also be relieved. Our result supports the idea that aneurysmal sac occlusion does not aggravate the associated mass effect in the long run and in fact, it is effective in alleviating the mass effect.

In addition, despite the residual lumen in the aneurysms, symptoms improved and usually did not recur even after recanalisation of the lumen. However, our study lacks long term follow-up and there is still a possibility of further luminal recanalization.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrated that GDC treatment of cavernous ICA aneurysm with parent artery preservation is safe and effective in relieving mass-related symptoms. However, the follow-up recanalisation rate was significantly high and judicious selection of the candidate is necessary. We consider new techniques such as remodeling or stenting may be useful in treatment of large or giant cavernous carotid aneurysms with broad necks.

References

- 1.Linskey M, Shekar L, et al. Aneurysms of the intracavernous caroid artery: a multidisciplinary approach. J Neurosurg. 1991;75:525–534. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.75.4.0525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barr JD, Holmes BP, et al. Extradural aneurysms. Neuroimaging Clin North Am. 1997;7:783–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Debrun G, Fox A, et al. Giant unclippable aneurysms: treatment with detachable balloons. Am J Neuroradiol. 1981;2:167–173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fox AJ, Viñuela F, et al. Use of detachable balloons for proximal artery occlusion in the treatment of unclippable cerebral aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 1987;66:40–46. doi: 10.3171/jns.1987.66.1.0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Higashida RT, Halbach VA, et al. Endovascular detachable balloon embolization therapy of cavernous carotid artery aneurysms: results in 87 cases. J Neurosurg. 1990;72:857–863. doi: 10.3171/jns.1990.72.6.0857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kupersmith MJ, Berenstein A, et al. Percutaneous transvascular treatment of giant carotid aneurysms: neuro-ophthalmologic findings. Neurology. 1984;34:328–335. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.3.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Little JR, Rosenfeld JV, et al. Internal carotid artery occlusion for cavernous segment aneurysm. Neurosurgery. 1989;25:398–404. doi: 10.1097/00006123-198909000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bavinzski G, Killer M, et al. Endovascular therapy of idiopathic cavernous aneurysms over 11 years. Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19:559–565. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guglielmi G, Viñuela F. Intracranial aneurysms: Guglielmi electrothrombotic coils. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 1994;5:427–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Viñuela F, Duckwiler G, et al. Guglielmi detachable coil embolization of acute intracranial aneurysm: perioperative anatomical and clinical outcome in 403 patients. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:475–482. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.86.3.0475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anon V, Aymard A, et al. Balloon occlusion of the internal carotid artery in 40 cases of giant intracavernous aneurysm: technical aspects, cerebral monitoring, and results. Neuroradiology. 1992;34:245–251. doi: 10.1007/BF00596347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linskey ME, Sekhar LN, et al. Aneurysms of the intracavernous carotid artery: natural history and indications for treatment. Neurosurgery. 1990;26:933–938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diaz F, Ohaegbulam S, et al. Surgical management of aneurysms in the cavernous sinus. Acta Neurochir. 1988;91:25–28. doi: 10.1007/BF01400523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kupersmith MJ, Hurst R, et al. The benign course of cavernous carotid artery aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 1992;77:690–693. doi: 10.3171/jns.1992.77.5.0690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnett DW, Barrow DL, et al. Combined extracranialintracranial bypass and intraoperative balloon occlusion for the treatment of intracavernous and proximal carotid artery aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 1994;35:92–98. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199407000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumon Y, Sakaki S, et al. Asymptomatic, unruptured carotid ophthalmic artery aneurysms: angiographical differentiation of each type, operative results, and indications. Surg Neurol. 1997;48:465–472. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(97)00175-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richling B, Gruber A, et al. GDC-system embolization for brain aneurysms: location and follow up. Acta Neurochir. 1995;134:177–183. doi: 10.1007/BF01417686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zubillaga AF, Guglielmi G, et al. Endovascular occlusion of intracranial aneurysms with electrically detachable coils: correlation of aneurysm neck size and treatment results. Am J Neuroradiol. 1994;15:815–820. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cognard C, Weill A, et al. Intracranial berry aneurysms: angiographic and clinical results after endovascular treatment. Radiology. 1998;206:499–510. doi: 10.1148/radiology.206.2.9457205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin D, Rodesch G, et al. Preliminary results of embolisation of nonsurgical intracranial aneurysms with GD coils: the 1st year of their use. Neuroradiology. 1996;38:S 142–150. doi: 10.1007/BF02278143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moret J, Cognard C, et al. The “remodelling technique” in the treatment of wide neck intracranial aneuryms: angiographic results and clinical follow-up in 56 cases. Interventional Neuroradiology. 1997;3:21–35. doi: 10.1177/159101999700300103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aletich VA, Debrun GM, et al. The remodeling technique of balloon-assisted Guglielmi detachable coil placement in wide-necked aneurysms: experience at the University of Illinois at Chicago. J Neurosurg. 2000;93:388–396. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.93.3.0388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilms G, van Calenbergh F, et al. Endovascular treatment of a ruptured paraclinoid aneurysm of the carotid siphon achieved using endovascular stent and endovascular coil placement. Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21:753–756. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strother CM, Eldevik P, et al. Thrombus formation and structure and the evolution of mass effect in intracranial aneurysms treated by balloon embolization: emphasis on MR findings. Am J Neuroradiol. 1989;10:787–796. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halbach VV, Higashida RT, et al. The efficacy of endosaccular aneurysm occlusion in alleviating neurological deficits produced by mass effect. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:659–666. doi: 10.3171/jns.1994.80.4.0659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsuura M, Terada T, et al. Magnetic resonance signal intensity and volume changes after endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms causing mass effect. Neuroradiology. 1998;40:184–188. doi: 10.1007/s002340050565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]