Abstract

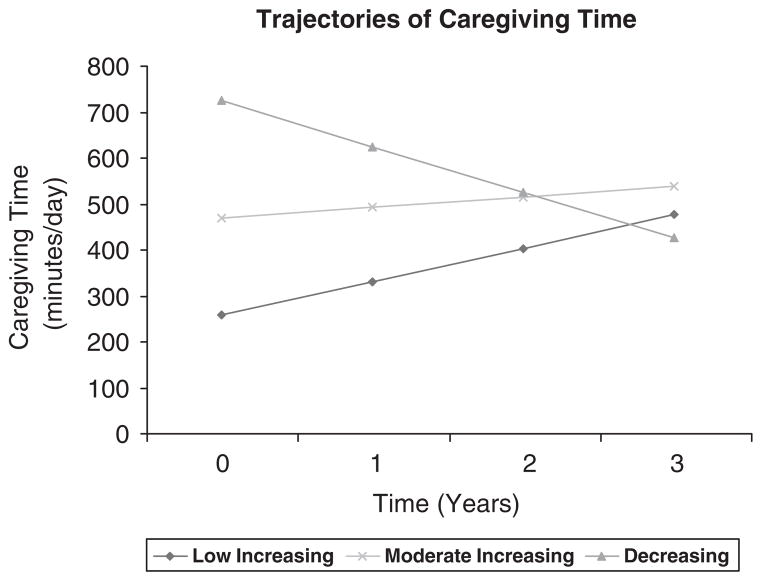

Spouses are often the first providers of informal care when their partners develop dementia. We used The National Longitudinal Caregiver Study (NLCS, 4 annual surveys, 1999 to 2002) and identified 3 distinct longitudinal patterns (trajectory classes) of total daily caregiving time provided by the wife to her husband using Generalized growth mixture models (GGMM). About 56.4% of the sample (N=828) was found to have an increase in the trajectory of total daily caregiving time (mean 252 min/d at baseline, rising to 471 min/d at time 4). Four hundred forty-four (30.3%) caregivers had a trajectory described by a moderate increase in caregiving time (an increase from a mean of 464 min/d at baseline to 533 at wave 4), whereas 195 (13.3%) had a sharply declining trajectory (a decline from a mean of 719 min/d at baseline to 421 at wave 4). There was no significant difference in the duration (time since onset) of caregiving at baseline for these 3 trajectories. GGMM are well suited for the identification of distinct trajectory classes. Here they show that there are large differences in caregiving time provided to persons with dementia, who seem to be quite similar.

Keywords: informal caregiving, longitudinal methods, burden of Alzheimer disease/dementia

Alzheimer disease (AD) and other dementias are progressive neurologic diseases which cause deficits in cognitive function that lead to inability to complete both basic and instrumental activities of daily living (B/IADL), gradually resulting in total dependence in these activities.1 Most of the 5 million persons2 suffering from AD live in community settings and receive most of their help and support to complete B/IADL (caregiving) from family members.3,4 Currently there are 7 million caregivers in the United States4 and a recent report suggests that by 2050, there will be 40 million caregivers, providing care for 28 million elderly disabled persons, a large number of these having AD or other dementias.5

The spouse is typically the first provider of care when an elderly person is married, though the estimates of the number of elderly persons receiving such care and the proportion provided by spouses differs across studies.6 Although it is clear that providing care for a person with AD or another dementia is time consuming and often burdensome, the amount of care provided by spouses would not be expected to be uniform across couples. The amount of time provided by a spouse could be expected to vary on the basis of the needs of the individual with dementia, the stage of the disease, and the circumstances of the caregiver, especially linkages with other potential caregivers. Describing distinct temporal patterns of caregiving time provided by wives for their husbands with dementia could help identify important patterns that may have practical, clinical, and broader policy implications in the manner that persons with dementia are treated. The goal of this study is to determine the number of distinct patterns or trajectory classes (hereafter called simply trajectories) in the amount of care (measured by minutes of care provided per day) provided by wives for their husbands with dementia. We then compare the trajectories identified using variables describing both the caregiver and the care recipient to determine whether specific trajectories differ in quantifiable ways as measured by important observed variables.

METHODS

Study Design and Sample

The National Longitudinal Caregiver Survey (NLCS)7 is a national survey of informal caregivers of elderly veterans living in the 48 contiguous states and Puerto Rico who were clinically diagnosed with AD or vascular dementia. The purpose of the NLCS was to document the amount and type of informal care provided to persons with dementia, and the consequences of providing such care on the caregiver. The same caregiver respondents were surveyed annually (1999 to 2002), up to 4 times. If the care recipient moved to a nursing home facility, this transition was tracked. Similarly, if the care recipient died, date and cause of death was also recorded.

Participants became eligible for study inclusion if they had an outpatient visit to a Veterans Administration Hospital or clinic in 1997 and who were age 60 or older, lived in a community setting, had a next of kin contact, and had a diagnosis of ICD-9-CM code 331.0 (AD) or 290.4 (vascular dementia) recorded in their medical chart.8 Households (N=9124) were invited to participate in the study, 5773 (63%) responded to the invitation, and 3665 met all the inclusion criteria and were sent an initial survey. Of these, 2279 surveys were returned, 11 of whom were found to be ineligible, yielding a full baseline sample of 2268.

Approximately 93% of the useable sample (N=2268) consisted of a wife caring for her husband, and we limit our analyses to this group because the remaining groups of respondents (mostly adult children caring for their father) were too small to yield reliable estimates. We sequentially excluded 54 male caregivers, 282 nonspousal caregivers, and 64 caregivers with missing data on all waves of caregiver time and 401 participants with missing covariates. Deleting participants with missing covariates was necessary because the growth models employed (see below) require subjects to have complete data for all covariates. The total number of caregiver-care recipient (wife-husband) dyads with complete information was 1467.

Outcome Measure

The NLCS gathered a great deal of information regarding the provision of care. A series of 22 questions determined if care was provided for ADL such as eating, dressing, and bathing, as well as for IADL such as helping with taking medication, driving to medical appointments, and shopping. For each item, the wife was asked if she provided help, and if she answered “yes, I regularly do this” she was asked how long this typically took. From these values, the amount of time spent providing care for that item per day was estimated. These item-specific time estimates were summed to create the outcome measure used in our study, total minutes of caregiving time per day. This measure has been used in past work to estimate the cost of informal care provided by caregivers.7

Analytic Approach

The goal of the analysis is to identify whether there are distinct trajectories or underlying patterns of development of total time of care provided by a wife to care for her husband with dementia. We take this approach because a population-averaging method that fits a single linear representation of the change in caregiving time provided over time may obscure different patterns that better describe distinct subgroups of caregivers. To determine whether such trajectories were present in the data, we used general growth mixture modeling (GGMM)9–12 which analyzed both the level and change in care giving time provided per day over 4 surveys spanning a 3-year period. Traditional growth modeling techniques assume a single growth model to describe the change. GGMM, on the other hand, tests if more than one distinct class can be used to describe the data, that is, whether there are underlying meaningful groups in the dataset. Such groups may be etiologically distinct or present practical categories useful for differentiating what might be optimal treatments for the different groups. Such variation may also be important for policy reasons.

Unlike random coefficient growth modeling, GGMM provides latent trajectory classes that allow for heterogeneity, growth shapes, and concurrent outcomes. In addition, GGMM enables each class of subjects to transition at different time points and provides flexible piecewise growth modeling.12,13 Finally, GGMM provides an estimate of an individual’s posterior probability of class membership. This method has been applied to address trajectories of alcohol use,14 typology of night-time bladder control,15 homelessness,16 and longitudinal math achievement scores12 in the past. We used M-plus version 4.2 statistical software17 to identify and describe distinct patterns of trajectories in caregiving time.

We first estimated a model with an intercept only, and then added a linear growth factor to determine the form of the caregiving time growth model. We then proceeded to identify the number of trajectory classes. The number of trajectory classes is determined by sequentially increasing the number of classes, examining the results and fit statistics (Akaike information criteria, Bayesian information criteria, and sample size adjusted Bayesian information criteria).18 For any of these fit-indices lower scores imply better fit. We also conducted sequential testing to determine if the decrease in likelihood ratio with increase in classes was statistically significant by using the Lo-Mendell-Rubin test.19 We examined the stability of the classes after including the following covariates, namely duration of care provided at baseline by the wife to the husband with dementia, patient characteristics of physical functioning, 20–22 and the following caregiver characteristics: age, income, race (white vs. others), education in years, sum of items on which help was received by caregiver and, whether or not the caregiver was employed.

After determining the number of trajectory classes, we examined the bivariate associations between the classes and the following variables: number of potential alternative caregivers and support persons living within 1 hour of the caregiver, including brothers or sisters, children, or other person that the caregiver could depend on who is not a family member. Related measures that were designed to provide a context of the support available to the caregiving wife were the caregiver network size, and the caregiver social interaction score.23 Other measures compared across trajectories include caregiver comorbid health conditions, overall caregiver life satisfaction,24 caregiver depressive symptoms,25 caregiver health service use, household income, race (white vs. other), and marital status. We examined the associations between categorical variables by using χ2 tests and, by using nonparametric tests26 for differences between the trajectory classes on the continuous variables.

RESULTS

All analysis sample members were wives caring for their husband who was diagnosed in a Veterans Administration clinic with dementia (either AD or vascular dementia). About 1162 (79.2%) of the wife caregivers were age 65 or older, and 82.1% (n=1204) lived alone with their husband. Virtually all of the couples had been together for 10 years or more (n=39, 2.7% had been married for less than 10 y) and 84.3% (n=1240) had been married for more than 25 years. The racial composition of the sample couples was similar to that of elderly Americans in general, with 83% being white, and 10% African American.

We identified 3 trajectories of total caregiving time provided by wives to their husband (Fig. 1). The most common trajectory represented just over 56.4% of all wife caregivers (n=828) and was characterized by a (relatively) low number of minutes of care provided per day at baseline (252 min/d) increasing to 471 min/d by wave 4 (hereafter called low increasing trajectory). The remainder of the sample was split between 2 sharply divergent trajectories, 1 (n=195, 13.3%) in which minutes of caregiving time fell from 719 min/d at baseline to 421 min/d at wave 4 (hereafter called decreasing trajectory), and the other (n=444, 30.3%) in which caregiving increased from 464 min/d at wave 1 to over 533 min/d at wave 4 (hereafter called moderate increasing trajectory). Standard fit statistics were assessed, indicating that the 3 trajectory classes model best described the data (Table 1). The Lo-Mendell-Rubin test was significantly different when moving from 1 to 2 and then from 2 to 3 trajectory classes, but was not significantly different and thus did not improve model fit when allowing for a fourth class.

FIGURE 1.

Trajectories of caregiving time.

TABLE 1.

Model Fit for Latent Class Analyses of Total Caregiving Time

| No. Classes | AIC | BIC | SSABIC | Lo-Mendell-Rubin | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 42138 | 42276 | 42193 | — | — |

| 2 | 42000 | 42153 | 42061 | 138 (P<0.001) | 0.74 |

| 3 | 41970 | 42139 | 42038 | 34 (P = 0.005) | 0.69 |

| 4 | 41962 | 42147 | 42036 | 20 (P = 0.30 | 0.67 |

| 5 | 41951 | 42153 | 42032 | 16.00 (P = 0.13) | 0.66 |

AIC indicates Akaike Information Criteria; BIC, Bayesian Information Criteria; SSABIC, sample size adjusted Bayesian Information Criteria.

The bold characters indicate the best fit.

The trajectories did not differ in terms of the type of dementia (AD vs. vascular dementia by the 3 classes) that care recipient husbands were suffering from [χ2, 0.17 (2 df), P=0.92]. We also tested for whether type of dementia (Alzheimer’s vs. vascular) experienced by the care recipient might influence hours of caregiving received within trajectories, and found that there was no difference in the mean caregiving time at baseline within the decreasing trajectory and the low increasing trajectory. Within the moderate increasing trajectory we found that those with vascular dementia received 491 min/d as compared with 473 min/d (P=0.05).

We compared the 3 trajectory classes using characteristics of the caregiver wife, the caregiving context, and the level of disability or need for care of the husband (Table 2). The wives represented in the 3 trajectories did not differ in terms of age, with wives in all 3 trajectories having mean age of near 70 years, and mean years of completed education were very near 12. Nor did the wives differ significantly in terms of how long they had been providing care for their husband across trajectories (P=0.11). Depressive symptoms of the caregiver wives also did not differ at baseline, nor did they differ across trajectories at later surveys (not shown in Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of Trajectory Classes of Total Caregiving Time

| Variables are for Wife Unless Noted | n | Low Increasing Total CG Time N = 828 |

n | Moderate Increasing Total CG Time N = 444 |

n | Decreasing Total CG Time N = 195 |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver characteristics | |||||||

| Age | 828 | 69.6 (7.4) | 444 | 70.2 (7.0) | 195 | 70.0 (7.00) | 0.51 |

| Race (% white) | 828 | 84.5 | 444 | 82.2 | 195 | 78.0 | 0.08 |

| Marital status (% 25 y and longer) | 828 | 84.2 | 444 | 83.8 | 195 | 85.6 | 0.84 |

| Education (average years of education completed) | 828 | 12.1 (2.7) | 444 | 12.0 (2.6) | 195 | 12.0 (2.7) | 0.78 |

| Ordered annual income groups (%) | 828 | 444 | 195 | 0.03 | |||

| $0–$4000 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| $4001–$9000 | 4.8 | 4.1 | 9.7 | ||||

| $9001–$18,000 | 33.9 | 35.1 | 36.9 | ||||

| $18,001–$30,000 | 34.3 | 35.4 | 36.4 | ||||

| $30,001–$40,000 | 12.8 | 14.4 | 7.7 | ||||

| $40,001–$50,000 | 6.4 | 5.6 | 2.1 | ||||

| $50,001–$60,000 | 5.6 | 2.9 | 5.6 | ||||

| >$60,000 | 0.36 | 0.45 | 0.51 | ||||

| Duration of care (y) | 828 | 4.2 (4.2) | 444 | 4.8 (5.5) | 195 | 5.2(6.4) | 0.11 |

| Caregiver Instrumental Support Scale (range: 0–42) | |||||||

| Wave 1 | 826 | 30.8 (7.6) | 442 | 29.2 (7.8) | 194 | 29.3 (7.9) | <0.001 |

| Wave 4 | 218 | 30.6 (7.7) | 127 | 29.9 (7.8) | 52 | 30.8 (9.2) | 0.56 |

| No. brothers or sisters within 1 h | |||||||

| Wave 1 | 825 | 1.0 (1.6) | 443 | 1.0 (1.5) | 191 | 1.1 (2.0) | 0.86 |

| Wave 4 | 218 | 1.1 (1.5) | 127 | 1.0 (1.5) | 51 | 1.4 (1.6) | 0.09 |

| No. children within 1 h | |||||||

| Wave 1 | 825 | 1.6 (1.6) | 442 | 1.6 (1.6) | 191 | 1.4 (1.6) | 0.09 |

| Wave 4 | 218 | 1.6 (1.5) | 127 | 1.8 (1.6) | 52 | 1.3 (1.3) | 0.12 |

| Person that you can depend on (not family) within 1 h | |||||||

| Wave 1 | 818 | 3.1 (9.3) | 439 | 3.4 (5.9) | 190 | 3.3 (8.2) | 0.08 |

| Wave 4 | 217 | 3.2 (7.1) | 127 | 2.6 (2.5) | 52 | 3.7 (5.2) | 0.64 |

| Caregiver social network size* | |||||||

| Wave 1 | 809 | 5.3 (3.6) | 433 | 5.5 (3.8) | 186 | 5.2 (4.1) | 0.22 |

| Wave 4 | 217 | 5.4 (3.5) | 126 | 5.4 (3.8) | 51 | 5.7 (4.0) | 0.98 |

| Caregiver social interaction score† | |||||||

| Wave 1 | 807 | 7.3 (3.4) | 433 | 7.6 (3.2) | 189 | 7.8 (3.6) | 0.24 |

| Wave 4 | 216 | 7.6 (3.6) | 123 | 7.7 (3.4) | 51 | 7.3 (4.0) | 0.82 |

| Caregiver CESD baseline‡ (range: 0–20) | 819 | 6.3 (4.7) | 438 | 6.7 (4.2) | 190 | 6.9 (5.2) | 0.30 |

| Caregiver service use (% yes)§ | 807 | 50.7 | 433 | 52.9 | 193 | 58.6 | 0.14 |

| Life satisfaction|| | 824 | 2.0 (0.6) | 441 | 2.0 (0.6) | 194 | 1.9 (0.6) | 0.48 |

| Caregiver comorbidities (range: 0–100) | 822 | 6.6 (4.4) | 442 | 29.2 (7.8) | 195 | 7.2 (4.7) | 0.26 |

| Husband ADL count (range: 0–7) | |||||||

| Wave 1 | 828 | 2.6 (2.3) | 444 | 2.8 (2.6) | 195 | 3.8 (3.0) | <0.001 |

| Wave 4 | 217 | 3.1 (2.7) | 126 | 3.8 (2.7) | 52 | 3.9 (2.7) | 0.04 |

| Husband IADL count (range: 0–7) | |||||||

| Wave 1 | 828 | 6.5 (1.2) | 444 | 6.6 (1.0) | 195 | 6.7 (1.1) | 0.01 |

| Wave 4 | 217 | 6.4 (1.3) | 126 | 6.7 (0.8) | 52 | 6.7 (0.9) | 0.29 |

| Follow-up status at the end of the study | 828 | 444 | 195 | ||||

| Continuing caregiver | 44.7 | 49.6 | 45.1 | 0.46 | |||

| Care recipient died | 21.4 | 21.9 | 25.1 | ||||

| Nursing home | 29.4 | 25.2 | 26.2 | ||||

| Other | 4.6 | 3.4 | 3.6 | ||||

Sum of the number of children, parents, grandparents, siblings, and others that can be depended on who live within 1 h of the home.

Higher score is indicative of more interaction. Range: 0–16.

Higher score is indicative of more depressive symptoms. Range: 0–20.

Do you hire people to do things your loved one used to, but is no longer able to do?

1—not satisfying; 2—fairly satisfying; and 3—very satisfying.

There were significant differences across the trajectories in the level of disability of the care recipient husband at baseline, measured by limitations in basic and instrumental ADL. The mean number of ADL limitations (out of 7) at the baseline was 2.6 for the low increasing trajectory, 2.8 for the moderately increasing trajectory and 3.8 for high decreasing trajectories (P<0.001). The mean level of ADL limitations experienced by surviving husbands rose as would be expected over time for all trajectories, but the pattern observed at baseline with the low increasing trajectory having the lowest level of disability remained. Similarly, care recipients in the decreasing trajectory had the highest mean level of impaired IADL at baseline (6.7 vs. 6.6 and 6.5, P=0.01) compared with the other 2 trajectories. However, the practical importance of the difference is small given that the maximum possible number of limitations in IADL is 7. The number of IADL limitations at wave 4 did not differ across trajectories (P=0.29). Another variable that differed significantly across trajectories was the amount of instrumental support that wife caregivers had available from others. Those in the low increasing trajectory had an instrumental support score of 30.8 (out of 42), as compared with 29.3 for the decreasing trajectory and 29.2 for the moderately increasing trajectory (P<0.001). Other variables that relate to help and support that wife caregivers could have in caring for their husband did not differ across caregiving time trajectories. Examples include number of brothers or sisters living within 1 hour, number of children within 1 hour, having a person who is not a family member who you can depend upon, and social network size. Finally, the follow-up status (continuing caregiving, death, nursing home admission) of the couples was not significantly related to membership in a given trajectory of caregiving time per day (P=0.46).

DISCUSSION

We identified 3 trajectories of caregiving time provided per day by wives to their husband with dementia. At baseline, there was nearly a 3-fold variation in mean minutes per day provided across the trajectories (ranging from 252 to 719 min/d). These differences were present despite the fact that caregiving had been ongoing for around 4.5–5.0 years in all trajectories, so stage of disease does not seem to explain the baseline differences in care. The amount of caregiving time provided per day did not remain constant across the studied period but instead converged, and at survey 4, the mean time/day ranged from 421 to 533 min/d, a much smaller variation. The slope of the trajectories differed, with 2 trajectories showing an upward sloping trend (increasing caregiving time/day) whereas 1 showed a substantial decrease (dropped by nearly half).

The reason for using a GGMM is the belief that there are underlying processes that make certain sample members more similar to one another than to others, and that this would be missed by the population-averaging methods that are typically used.14–16 Key evidence that the trajectories of caregiving time differed in a fundamental manner that is not explained by other factors includes the fact that several key variables did not differ at baseline, notably duration of care at baseline and the size of the network of alternative caregivers available to a wife caregiver. Further, the results are not explained by differences in follow-up due to death, institutionalization, and loss to follow-up. There were some differences at baseline across trajectories in variables clearly related to caregiving time/day, notably the amount of disability observed as measured by I/ADL limitations of husbands.

The strengths of this paper include a relatively large sample of caregiver dyads, with caregivers followed through up to 4 survey points collected over 3 years. The survey also contains some detailed measures of caregiving and support persons that are related to caregiving. Caregiving dyads in this paper are all wives caring for their husband with dementia. This is one of the most common reasons for needing caregiving, but dementia caregiving may differ from caregiving for other medical/health reasons, so we cannot generalize the findings beyond caregiving for dementia. We could only study wives caring for their husbands, and so were unable to identify sex differences in caregiving time, and/or interaction of the broader family or social network and how care is provided for elderly persons with dementia. Furthermore, detailed measures of the symptoms of the husband with dementia are not available, so it is possible that there were differences in stage of dementia across patients that were not fully controlled for by adjusting for duration of caregiving at baseline. Finally, our measures of I/ADL disability of the care recipient were recalled by the caregiver so could be subject to recall bias. To the extent that this exists it is a limitation, but it should be constant within the subject, and the disability of a caregiver’s husband is a salient concept for someone providing dementia care. We did not have a measure of caregiver cognition; it is possible that the couple dyads who were excluded from the study are more likely to have an impaired caregiving wife, but we cannot test for this.

This paper provides evidence that there is substantial variation in the amount of time spent providing care to husbands with dementia, even though the duration of caregiving in similar. This is possibly explained by stage of illness, but the similar duration of caregiving at baseline makes this explanation less plausible. The fact that the composition of dementia type was virtually identical in each trajectory (around 60% Alzheimer disease) also lessens worries that illness severity or type of dementia is a key driver of our findings. The levels of disability as measured by limitations in ADL and IADL differ significantly across trajectories, but the practical meaning of these differences (all trajectories have near complete IADL dependence, and the high decreasing trajectory had a little over 1 more ADL limitation, on average) do not easily correspond to the greater than 3-fold difference in minutes of care/day at baseline (250 min/d vs. 725 min/d). This supports the notion that there is an underlying process that makes some couple dyads systematically different from others with respect to amount of caregiving time provided/day.

The trajectory with the smallest number of couples (13.2% of the sample) in particular stands out because the amount of caregiver time/day declines from around 719 min/d to around 421 min/d, a decrease of nearly half. Is this decline evidence of an inappropriate (too little) time being provided to an individual with dementia? Is it simply a case of a trajectory in which too much, or at least an unneeded amount of care was provided earlier in the disease course, and that levels decline later on? Or are these persons who have progressed more rapidly into a stage of disease in which mobility declines are so great that less care is needed? Caregiver wife depressive symptoms did not differ across trajectories at baseline or at follow-up surveys, so it does not seem to be a case of declining caregiving time due to changes in the mental health of the caregiver wife. The answers to these questions cannot be easily answered by our analysis, but the method we used can identify trajectories that are substantially different from the “average” experience. These trajectories may be worth closer inspection and may be masked by more traditional methods. Application of these methods to other samples with recorded caregiver time may be useful in determining whether there are similar trajectories in those samples or if the trajectories we identified are idiosyncratic to the National Longitudinal Caregiver Survey. The GGMM method should also be applicable to other phenomena related to AD and dementia and the care of persons suffering from these diseases.

Acknowledgments

Supported by a grant from the National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institutes of Health, 1RO1 NR008763-01A1.

References

- 1.Schulz R. Handbook on Dementia Caregiving: Evidence-based Interventions for Family Caregivers. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alzheimer’s Association. [Accessed on July 12, 2007];Alzheimer’s Facts and Figures. 2007 Available at: http://www.alz.org/alzheimers_disease_alzheimer_statistics.asp.

- 3.Cummings JL, Cole G. Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 2002;287:2335–2338. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.18.2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schulz R, Martire M. Family caregiving of persons with dementia: prevalence, health effects, and support strategies. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;12:240–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Department of Health and Human Services. The Future Supply of Long-term Care Workers in Relation to the Aging Baby-boom Generation. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burton LC, Zdaniuk B, Schulz R, et al. Transitions in spousal caregiving. Gerontologist. 2003;43:230–241. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.2.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore MJ, Zhu CW, Clipp EC. Informal costs of dementia care: estimates from the National Longitudinal Caregiver Study. J Gerontol B-Psychol. 2001;56:S219–S228. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.4.s219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buhr GT, Kuchibhatla M, Clipp EC. Caregivers’ reasons for nursing home placement: clues for improving discussions with families prior to the transition. Gerontologist. 2006;48:52–61. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muthén B, Shedden K. Finite mixture modeling with mixture outcomes using the EM algorithm. Biometrics. 1999;55:463–469. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muthén B, Brown CH, Masyn K, et al. General growth mixture modeling for randomized preventative interventions. Biostatistics. 2002;3:459–475. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/3.4.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muthén B. Latent variable analysis: growth mixture modeling and related techniques for longitudinal data. In: Kaplan D, editor. Handbook of Quantitative Methodology for the Social Sciences. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muthén B. Latent variable mixture modeling. In: Marcoulides GA, Schumacker RE, editors. New Developments and Techniques in Structural Equation Modeling. Newark, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2001. pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muthen B, Brown CH, Khoo S, et al. General growth mixture modeling of latent trajectory classes: Perspectives and prospects. June 1998; Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Prevention Science and Methodology Group; Tempe, AZ. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harford TC, Muthen BO. Adolescent and young adult antisocial behavior and adult alcohol use disorders: a fourteen-year prospective follow-up in a national survey. J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61:524–528. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Croudace TJ, Jarvelin MR, Wadsworth ME, et al. Developmental typology of trajectories to nighttime bladder control: epidemiologic application of longitudinal latent class analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:834–842. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lennon MC, McAllister W, Kuang L, et al. Capturing intervention effects over time: reanalysis of a critical time intervention for homeless mentally ill men. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1760–1766. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muthen LK, Muthen BO. M-plus Statistical Analysis With Latent Variables—User’s Guide, 2004. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sclove SL. Applications of model-selection information criteria to some problems in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika. 1987;52:333–343. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lo Y, Mendell NR, Rubin DB. Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika. 2001;88:767–778. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Older Americans Resources and Services, Duke University. The OARS Multidimensional Functional Assessment Questionnaire. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 1975. revised 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fillenbaum G. Multidimensional Functional Assessment of Older Adults. Hilldale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosow I, Breslau N. A Guttman health scale for the aged. J Gerontol. 1966;21:556–559. doi: 10.1093/geronj/21.4.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.George LK, Gwyther LP. Caregiver well-being: a multidimensional examination of family caregivers of demented adults. Gerontology. 1986;26:253–259. doi: 10.1093/geront/26.3.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfeiffer E. Proceedings of the Bayer Symposium, VII, Brain Function in Old Age. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1979. A Short Psychiatric Evaluation Schedule: A New 15-item Monotonic Scale Indicative of Functional Psychiatric Disorder. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kohout F, Berkman L, Evans D, et al. Two shorter forms of the CES-D depression systems index. J Aging Health. 1993;5:179–193. doi: 10.1177/089826439300500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kruskal WH, Wallis WA. Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis. J Am Statist Assoc. 1952;47:583–621. [Google Scholar]