Abstract

In this issue of Immunity, Shi et al. (2008) identify a previously unknown requirement in T helper cell differentiation, showing that Jak3 and STAT5 are needed to generate chromatin that is permissive to the activating effects of T-bet.

A “pregenomic” notion was that some transcription factors were “master” regulators of certain cellular phenotypes, applying (perhaps incorrectly) archaic social structures to the domain of gene regulation. A flood of “postgenomic” data suggests a different view of gene regulatory networks, emphasizing subtlety and cooperation in tipping the balance of complex biological systems. In this issue of Immunity, Shi et al. (2008) provide such an example, in which a “master” is shown to operate within the context of previously unrecognized signals, refining our understanding of T helper cell differentiation.

The talented CD4+ T cell plays many roles in immunity, predominantly helping to organize the activities of other immune players on the stage. In doing so, CD4+ T cells adopt a variety of “personalities” (i.e., effector functions), each adapted to defend against different kinds of pathogens; currently, there are three forms of CD4+ effector subsets, termed T helper (Th) 1, Th2, and Th-17. It is by the production of distinct patterns of cytokines that these subsets exert their important coordinating activities, and for Th1 cells, this means producing interferon-γ (IFN-γ), which acts in mobilizing cellular immunity against intracellular pathogens.

For Th1 cells, the transcription factor T-bet is critical for driving differentiation and Ifng expression (Szabo et al., 2000). However, NK cells (and other T cell subsets such as NKT or γδT cells) also use T-bet for Ifng gene expression (Townsend et al., 2004) but begin their life with this locus already poised for expression. So what is the point of providing CD4+ T cells with multiple personalities requiring additional layers of gene regulation? Presumably, the immune system benefits from the CD4+ T cell’s heightened sensitivity for pathogen detection and capacity for clonal expansion, promoting sterilizing immunity and immunological memory.

Therefore, an essential ability of CD4+ T cells is to turn on, and off, various cytokine genes. For this, key cytokine genes are silenced during thymocyte development; when naive CD4+ T cells emerge, their Ifng shows signs of inactive active chromatin, such as hypermethylation at CpG residues, and lacks signs of active chromatin, such as histone acetylation (Avni et al., 2002; Fields et al., 2002). These features are reversed during Th1 cell differentiation through several steps, involving the cytokines IFN-γ and IL-12, and activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)1 and STAT4 and several other transcription factors, most critically T-bet. The proximal Ifng promoter has several sites that can bind T-bet (Cho et al., 2003), but beyond this, there are several cis-regulatory elements located at much more distant sites that contribute to lineage-specific expression of Ifng. Several of these conserved noncoding sequences (CNSs) act as enhancers for Ifng expression in vitro (Agarwal and Rao, 1998; Lee et al., 2004; Shnyreva et al., 2004) and can exhibit lineage-specific histone-hyperacetylation (Avni et al., 2002; Fields et al., 2002). Among these, CNS1 (aka CNS-5), located 5 kb upstream, and CNS2 (CNS+17) 17 kb downstream of the Ifng gene promoter enhance Ifng expression in a T-bet-dependent manner in Th1 cells (Lee et al., 2004; Shnyreva et al., 2004). Another region, CNS-22, is essential for Ifng expression in Th1 cells, cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) and NK cells, binds T-bet in resting and activated cells, and exhibits histone hyperacetylation in Th1 and Th2 cells (Hatton et al., 2006). CNS-22 also has clustered sites for GATA, STAT, IRF, NF-κB, and Ikaros family transcription factors and is the only control element surrounding Ifng to show substantial histone acetylation in naive CD4+ cells or Th2 cells. Thus, CNS-22 could represent a “pioneering” chromatin entry point for the spread of T-bet binding throughout the Ifng locus during Th1 cell differentiation and may act as an “interaction platform” for T-bet and GATA3 to activate Ifng in Th1 cells but silence it in Th2 cells (Hatton et al., 2006).

It is in this context that the study by Shi et al. (2008) arises. Previous interests of the Berg laboratory in Jak kinases led to an examination of potential roles for Jak3 in Th1 cell differentiation. Quite surprisingly, Jak3−/− T cells (or the pharmacologic inhibition of Jak3) exhibited a dramatic reduction in Ifng gene expression under Th1-skewing conditions. This reduction was not simply due to a defect in TCR signaling, or to a requirement for Jak3 in activating STAT1 or STAT4, or to a requirement for Jak3 in the induction of T-bet. Indeed, T-bet expression was induced normally in Jak3−/− Th1 cells. Instead, using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays, Shi et al. (2008) found a defect in the ability of T-bet to become associated with the proximal Ifng promoter in Jak3−/− Th1 cells. In addition, Jak3−/− T cells revealed a generalized reduction in histone H3 acetylation of the Ifng promoter region. This loss of T-bet association with the proximal Ifng promoter did not seem to be due to an inherent defect in the functional activity of T-bet because transcription of another target of T-bet, the gene encoding IL-12Rβ2 subunit, was maintained.

The requirement for Jak3 in Th1 cell differentiation begged the question of a corresponding cytokine and STAT requirement. Because Jak3 is not used by receptors for IFN-γ or IL-12, Shi et al. (2008) considered other cytokines that used the common receptor subunit γc (which utilizes Jak3) and other STATs that γc may activate, beginning with IL-2 and STAT5. Again, using ChIP assays, they found that STAT5 could be detected to bind to sites in the proximal Ifng promoter and sites in the CNS1 region (at −5 kb) and to bind very weakly to the CNS2 region (+17 kb). Interestingly, the authors did not find any evidence of STAT5 binding to more distant CNS-22 or CNS-34 elements, even though these regions are known to have STAT-binding consensus sequences and to be necessary (in the case of CNS-22) for induction by IL-12 and IL-18 of IFN-γ production (Hatton et al., 2006). Thus, the distribution of STAT5 binding to the Ifng locus appears to be restricted to regions of the genes that would become activated subsequently to the initial interactions of T-bet with the CNS-22 regions. Finally, the authors also showed a reduction in the percentage of IFN-γ production by T cells that were lacking STAT5a and STAT5b expression. This reduction was not as dramatic as that caused by Jak3 deficiency, but experimentally, it relied on double Cre-mediated deletion of two STAT5 alleles, which may be less than 100% efficient, and could conceivably underrepresent the degree of STAT5-dependence of the Ifng locus. Blockade of IL-2 signaling also reduced the amount of IFN-γ production in developing Th1 cells, indicating that IL-2 and STAT5 play functional roles in tuning the amount of IFN-γ produced by developing Th1 cells.

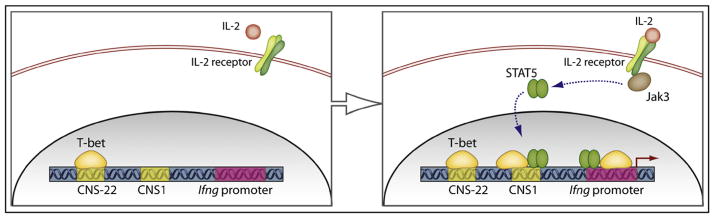

Thus, the authors show a role for Jak3, IL-2 signaling, and STAT5 activation of the Ifng locus during Th1 cell differentiation. Although many details remain to be worked out, the data suggest a sequential (if speculative) model of cooperativity among CNS regions, T-bet, and STAT5 during activation of Ifng in Th1 cell differentiation. In this model (Figure 1), the CNS-22 element, which is constitutively accessible, is the “pioneering” foothold for T-bet binding near the Ifng locus. During Th1 cell development, T-bet expression rises, and GATA3 declines; previously, we would have presumed that this rising tide of T-bet would gain unfettered access to the more proximal CNS1 and then simply wash up onto the Ifng promoter, activating its transcription. But Shi et al.’s findings suggest that this phase of Th1 cell development is more finely regulated, and IL-2, Jak3, and STAT5 act as “guards,” giving permission to T-bet for entry into the Ifng locus. This regulation would be enforced by requiring STAT5 binding at CNS1 (and the Ifng promoter) in order for T-bet to gain access and spread toward the promoter. Mechanistically, perhaps STAT5 binding to the CNS1 region may be necessary for T-bet to interact with specific brachyury-binding sites in this region; similar cooperativity has been suggested for factors interacting at CNS-22, such as direct factor interactions gated by tethering to specific composite DNA-binding sites (Hatton et al., 2006). By whatever mechanism, without this “permission” of entry provided by STAT5 at CNS1, the “master” T-bet would be prevented from gaining a foothold nearer to the Ifng promoter.

Figure 1. Action of Jak3 and STAT5 in Th1 Cell Development.

As shown in the left panel, the conserved noncoding sequence (CNS)-22, located 22 kb upstream of the interferon-γ (Ifng) gene promoter binds T-bet, shows an active chromatin configuration even in naive CD4+ T cells, and may represent the initial platform of activation. Shi et al. (2008) show that in the absence of Jak3, T-bet is unable to gain access to sites more proximal to the Ifng promoter. The right panel shows that upon IL-2 signaling, STAT5 itself binds to CNS1 (at −5 kb) and to sites near the promoter, suggesting a model in which IL-2, Jak3, and STAT5 form a system to permit encroachment of T-bet into the Ifng locus.

Clearly much more work is required to test these notions, and more factors are likely to be involved. But in any case, Shi et al.’s study suggests some intriguing and immediate avenues. It will be interesting to examine whether the ability of STAT5 to bind these sites is somehow dependent on T-bet as well and to find out whether these restrictions in T-bet accessibility in Jak3−/− CD4+ T cells apply to other lineages of cells, such as NK cells or CD8+ T cells. Possibly more compelling is the question of what immunologic benefit is provided by using the IL-2-Jak3-STAT5 axis to guard the Ifng locus against full activation by T-bet. Perhaps this is just one more example of the pervasive regulatory actions of IL-2, which seem ever more impossible to understand in the pregenomic mindset of “on or off.”

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agarwal S, Rao A. Immunity. 1998;9:765–775. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80642-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avni O, Lee D, Macian F, Szabo SJ, Glimcher LH, Rao A. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:643–651. doi: 10.1038/ni808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho JY, Grigura V, Murphy TL, Murphy K. Int Immunol. 2003;15:1149–1160. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxg113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields PE, Kim ST, Flavell RA. J Immunol. 2002;169:647–650. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.2.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton RD, Harrington LE, Luther RJ, Wake-field T, Janowski KM, Oliver JR, Lallone RL, Murphy KM, Weaver CT. Immunity. 2006;25:717–729. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DU, Avni O, Chen L, Rao A. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:4802–4810. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307904200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi M, Lin TH, Appell KC, Berg LJ. Immunity. 2008;28:763–773. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.04.016. this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shnyreva M, Weaver WM, Blanchette M, Taylor SL, Tompa M, Fitzpatrick DR, Wilson CB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12622–12627. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400849101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo SJ, Kim ST, Costa GL, Zhang XK, Fathman CG, Glimcher LH. Cell. 2000;100:655–669. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80702-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend MJ, Weinmann AS, Matsuda JL, Salomon R, Farnham PJ, Biron CA, Gapin L, Glimcher LH. Immunity. 2004;20:477–494. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]