Abstract

Microdamage has been cited as an important element of trabecular bone quality and fracture risk, as materials with flaws have lower modulus and strength than equivalent undamaged materials. However, the magnitude of the effect of damage on failure properties depends on its tendency to propagate. Human femoral trabecular bone from the neck and greater trochanter was subjected to one of compressive, torsional, or combined compression and torsion. The in vivo, new, and propagating damage were then quantified in thick sections under epifluorescent microscopy. Multiaxial loading, which was intended to represent an off-axis load such as a fall or accident, caused much more damage than either simple compression or shear, and similarly caused the greatest stiffness loss. In all cases, initiation of new damage far exceeded the propagation of existing damage. This may reflect stress redistribution away from damaged trabeculae, resulting in new damage sites. However, the accumulation of new damage was positively correlated with the quantity of pre-existing damage in all loading modes, indicating that damaged bone is inherently more prone to further damage formation. Moreover, about 50% of in vivo microcracks propagated under each type of loading. Finally, damage formation was positively correlated to decreased compressive stiffness following both axial and shear loading. Taken together, these results demonstrate that damage in trabecular bone adversely affects its mechanical properties, and is indicative of bone that is more susceptible to further damage.

Keywords: Bone quality, microdamage, damage propagation, aging, trabecular bone

1. Introduction

Microdamage, such as microcracks and diffuse damage, occurs in trabecular bone in vivo and is considered an important aspect of bone quality [1, 2]. The microdamage burden in humans increases with age and impaired trabecular architecture [3], and antiresorptive treatments for osteoporosis result in increased microdamage burden in animal models [4–7]. Microdamage in a material reduces the stiffness, and can provide local stress concentrations that initiate failure. If microdamage in bone were to propagate or coalesce during loading, it would similarly hasten failure of the bone. Induction of fatigue damage in canine femora does indeed decrease stiffness and strength [8, 9], and damaged regions in human femoral bone expand during fatigue loading [10]. However, damaging bovine trabecular bone had only a small effect on the energy to failure in comparison to decreased bone mineral density (BMD) and increased trabecular slenderness [11, 12]. Similarly, the compressive strength of human vertebral trabecular bone is primarily determined by the amount of trabecular bone, and relatively unaffected by normal variations in microdamage [13]. As such, the role of microdamage in bone strength and fracture in relation to other factors such as BMD and architecture is not clear.

Microstructural features in bone may make it tolerant to damage. In cortical bone, damage propagates during fatigue loading, but is deflected or arrested by osteons [14]. Because of this, microcracking may provide a means to dissipate energy and slow the formation and growth of a macroscopic crack [15]. In trabecular bone, damage depends on the architecture. Microdamage is more common in more rod-like bone, [16] and in bone where rod-like trabeculae are subjected to high strains [17, 18]. For example, in the human distal femur, rod-like trabeculae oriented along the loading axis are more susceptible to severe microdamage formation [10].

Similar to cortical bone, microcrack length is thought to be self-limiting in trabecular bone [16, 19], which may allow it to be repaired by remodeling rather than progressing to fracture [20, 21]. However, when samples of trabecular bone with pre-existing microdamage due to an axial overload were subsequently loaded in torsion, both initiation and propagation of microcracks were higher than expected in regions of bone strained below the yield point [16, 22]. Similarly, damage induced by off-axis loads propagated during subsequent on-axis compressive loading [16].

The goal of this study was to determine whether in vivo damage was an indicator of damage susceptibility in trabecular bone, and, if so, whether it is a result of propagation of the existing microcracks. To address this goal, we (1) quantified the in vivo microdamage in human femoral trabecular bone samples, (2) overloaded the samples in three different loading modes to induce additional damage, (3) determined if the formation and propagation of damage was dependent on loading mode, architecture, and in vivo damage, and (4) determined if the resulting stiffness loss was correlated to formation of microdamage during overloading.

2. Materials and methods

Human femoral trabecular bone from older men and women was studied. Twenty-four fresh-frozen proximal femora from 12 male and 12 female donors were obtained from a national tissue bank (NDRI) with informed consent. Donors were screened for metastatic bone disease, Cushing’s disease, Paget’s disease, osteomalacia, osteogenesis imperfecta, liver or kidney disease, hypo- or hyper-parathyroidism, syphilis, alcoholism, chemotherapy or radiation in the past 3 years, bed rest over 6 weeks, or evidence of previous hip fracture. Donor records indicated no use of bisphosphonates or steroids for any donor, but one donor had a history of tobacco use. The bone was not screened for osteoarthritis, which can affect damage morphology [23], nor for osteoporosis. The tissue was frozen within 24 hours post-mortem, and stored at −20°C until testing. The mean age was 71.4 ± 12.1 y, and did not differ between sexes. In previous studies, donors in this age range had in vivo microcrack densities (Cr.Dn. = # of cracks per unit area of bone) in the range of 1 – 2 mm−2 [24], similar to these samples (Table 1).

Table 1.

Microarchitecture parameters and in vivo microdamage (mean ± S.D.). * Bold entries indicate significant differences between the neck and greater trochanter (p < 0.05, paired T-Test).

| Neck | Trochanter | |

|---|---|---|

| BV/TV | 0.25±0.11 | 0.16 ± 0.07 |

| Tb.Th (mm) | 0.21 ± 0.06 | 0.16 ±0.03 |

| Tb.Sp (mm) | 0.70 ± 0.15 | 0.82 ± 0.23 |

| SMI | 0.87 ± 0.82 | 1.49 ± 0.56 |

| DA | 1.77 ± 0.28 | 1.73 ± 0.26 |

| Cr.Dn in vivo (mm−2) | 0.82 ± 0.48 | 0.97 ± 0.53 |

| Cr.S.Dn in vivo (mm−1) | 0.055 ± 0.037 | 0.045 ± 0.025 |

| Cr.Ln in vivo (μm) | 63 ± 20 | 47 ± 5 |

BV/TV = volume fraction, Tb.Th = trabecular thickness, Tb.Sp = trabecular separation, SMI = structure model index, DA = degree of anisotropy, Cr.Dn = crack density, Cr.S.Dn = crack surface density and Cr.Ln = mean crack length

2.1 Specimen preparation

One specimen was obtained from the neck and one from the greater trochanter of each femur (Fig. 1). These sites are commonly involved in osteoporotic fractures during falls, and provided a contrast in density and architecture to better identify the effects of these parameters on microdamage formation. Cylindrical specimens were prepared with the principal material axis aligned with the cylinder axis, as detailed in [25]. Briefly, 4 to 5 cm parallelepipeds of trabecular bone were scanned at 80 μm resolution (Scanco μ-CT 80, Brüttisellen, Switzerland) in a fixture that maintained alignment between the bone and scanner coordinate systems. A finite element model of a 5×5×5 mm central region was subjected to six independent uniaxial strain conditions in order to find the principal material coordinate system [26]. An 8 mm diameter cylindrical sample was prepared along the calculated orientation through the modeled region using a custom orientation jig and a diamond coring drill (Starlite Industries, Bryn Mawr, PA) [25]. This precise alignment of the material coordinate system ensured that the stress could be accurately determined from mechanical tests [27–29].

Figure 1.

a) Samples were taken from the femoral neck and greater trochanter of the human proximal femur in locations that allowed highly aligned specimens to be obtained. b) Samples were subjected to one of axial compression, torsion, or combined compression and torsion, and microcrack formation and propagation were quantified.

A 6 mm long region of each sample was scanned at 20 μm resolution (70 kVp, 114 μA, 500 projections/180°, 210 μs/projection), and the architecture was quantified using model free methods (IPL, Scanco Medical, Bassersdorf, Switzerland). These scans were also used to construct finite element models with 20 μm voxel elements to validate the alignment of the sample with the principal material axis, which was within 6.9 ± 3.3° (mean ± SD). The specimens were wrapped in gauze saturated with buffered saline, and stored at −20°C in airtight containers except during scanning, staining, and mechanical testing.

2.2 Mechanical testing

The 24 samples from each site were divided into three groups balanced by sex, bone mineral density (BMD), and BV/TV. The groups were subsequently subjected to one of three overloads to induce microdamage. Samples in Group I were subjected to 2% axial compressive strain, (2% compressive and 0% tensile principal strains aligned with the principal trabecular orientation). Samples in Group II were subjected to torsion to 4% shear strain (2% principal compressive and tensile strains oriented at 45° to the principal trabecular orientation). Group III was subjected to combined compression and torsion to 1.24% compressive and 2.47% shear strain (2% compressive and 0.76% tensile principal strains oriented 31.7° from the principal orientations). The shear and multiaxial cases were used to represent uncommon loading modes for trabecular bone. For example, shear and multiaxial stress with respect to the principal trabecular orientation occurs during falls [30]. Group II was, on average, younger than group III (p < 0.05, ANOVA), while group I was similar to the other two.

The initial Young’s and shear moduli were measured using two compressive loads to 0.4% strain in compression followed by three torsional loads to 0.8% shear strain. These strains were below the threshold required to induce measurable microdamage in either monotonic or fatigue loading [31–33], although it could result in modulus degradation [34]. The stress-strain data were fit to second order polynomials, and the moduli were found from the slope of the curve at zero stress [35].

Yield properties were determined by the 0.2% offset strain. For Group III, a composite stress-strain curve was formed by summing the compressive and shear stress and strain at each time-point. The shear and multiaxial curves were further corrected by Nadai’s equation [36] before determining the yield properties.

Tests were conducted in strain control on an Instron 8821s biaxial load frame (Instron, Canton, MA) at room temperature with the exposed portion of the specimen wrapped in gauze saturated with buffered saline. Specimens were gripped in the load frame via brass endcaps to reduce testing artifacts [37]. Strains were measured by a biaxial extensometer (model 3550, Epsilon Technology Corp., Jackson, WY) attached to the endcaps. The effective gage length was taken as the exposed plus half the embedded length of the specimen for axial loading, and the exposed length for torsional loading [38].

2.3 Microdamage quantification

Prior to mechanical testing, the specimens were stained in a solution of 0.5 mM alizarin complexone (ICN Biomedicals Inc., Aurora, OH) to label microdamage incurred in vivo or during specimen preparation. In previous studies using this protocol, the specimen preparation process produced minimal damage, except near the cut surfaces [16, 19, 33]. Following the overload, new and propagated damage were labeled by a solution of 0.5 mM calcein (ICN Biomedicals Inc., Aurora, OH). Specimens were stained for 2 h in vacuum, then rinsed in deionized water.

Following testing, the specimens were dehydrated in a sequence of ethanol solutions ending with 100% ethanol for 12 h, and embedded in transparent methyl methacrylate (MMA, Aldrich Chemical Company, Inc., Milwaukee, WI) under vacuum. Two, 200 μm thick sections were cut along the axis of each core using a diamond saw (ISOMET, Buehler Ltd., Lake Bluff, IL). The sections were polished beginning with 600 grit paper and ending with 1/4 μm diamond paste (Phoenix Beta, Buehler, Lake Bluff, IL) to a final thickness of approximately 150 μm, and mounted on glass slides using Eukitt’s mounting medium (American Histology Reagent Company, Inc., Hawthorne, NY).

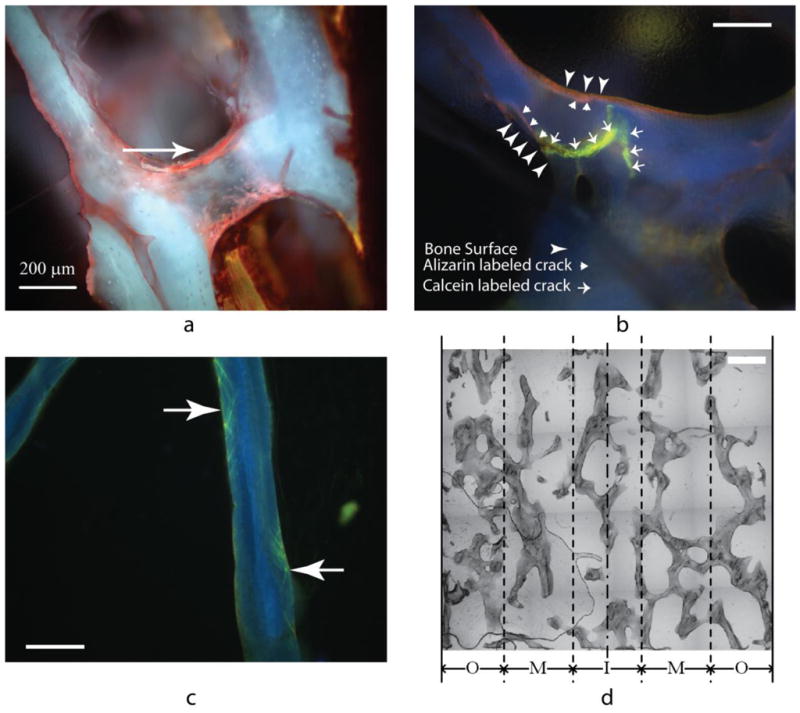

Microdamage was imaged under epifluorescence microscopy (Eclipse ME 600, Nikon Inc., Melville, NY) with an excitation wavelength of 365 nm (UV-1A filter, Nikon Inc., Melville, NY). Images of each section were captured at 100 X magnification using a CCD camera, and composited to form a single image for the slice (Photoshop, Adobe Systems, San Jose). Each composite image was divided into longitudinal regions according to the distance from the specimen axis with the distance corrected for slice location [16] (Fig. 2). The area of the bone within 0.4 mm of the perimeter was excluded to avoid the cut surfaces and minimize counting of machining damage [3]. A pilot study showed that damage labeled sequentially by alizarin complexone, xylenol orange, and calcein could be differentiated, as previously shown in cortical bone [39] (see supplemental data).

Figure 2.

a) Alizarin stained linear microcracks; b) a propagated crack with both alizarin and calcein staining; c) calcein stained microcracks in a cross-hatched pattern. d) Cracks were categorized into three radial regions to compensate for differences in applied shear strain during torsional and multiaxial loading. Only about 5 to 10% of cracks passed through the center of trabeculae, while most were found near the bone surface. Approximately 10% of cracks appeared as cross-hatching.

Microcracks were quantified using ImageJ (Ver. 1.44, National Institutes of Health). Bone area (B.Ar) was measured by thresholding the images. Individual microcracks were identified by the presence of distinct edges that showed permeation of stain into the bone (Fig. 2) and counted to determine the crack number (Cr.N). Single cracks, whether central or near the edge of the bone, arrays of parallel cracks, and cross-hatched cracks were detected and quantified as in previous studies [16, 19, 40]. When it was unclear if a stained region was a crack, its presence over multiple focal planes and that the staining was not directly on the surface was verified by viewing the crack on the original slide under 200 X microscopy. Each crack, including the individual cracks in cross-hatched damage regions (Fig. 2c), was counted and traced to measure the length. For cracks labeled by both alizarin and calcein, each label was measured separately. The mean length (Cr.Ln) was calculated as the total length divided by the number of microcracks. Microcrack density (Cr.Dn.) and surface density (Cr.S.Dn) were calculated as Cr.N./B.Ar. and Cr.Dn × Cr.Ln, respectively. Diffuse damage was present but was not quantified, as the focus was crack propagation. While the protocol was to identify cracks emanating from diffuse damage regions as new, rather than propagating, no such cracks were noted. Although diffuse damage could affect further damage development, previous studies suggest that linear microcracks and diffuse damage are due to different mechanisms and are not related [1, 3].

One sample from the femoral neck and one from the greater trochanter in the compressive overloading group were too short for accurate testing. One sample from the greater trochanter in the multiaxial group was broken during testing, leaving 45 total samples.

Statistical tests were performed to identify the dependence of new and propagating damage on any architectural parameters, or pre-existing damage. The tests also included age, tissue mineral density (TMD), and anatomic site as covariates in order to account for dependence on these parameters. Both BV/TV and SMI were included in the model simultaneously, but in most cases only one was statistically significant because these two parameters are strongly inversely correlated. Additional analyses were run using each of these parameters separately, but still including the other architectural parameters to determine if these were truly independent predictors of the behavior. Generalized Linear Models (GLM; JMP and SAS, SAS Institute, Cary, NC), were used because the independent variables depended on categorical variables. A logarithmic link function was applied to the damage parameters (Cr.Dn, Cr.Ln, Cr.S.Dn) in the GLM, as they exhibited a log-normal distribution. Mixed models were used to include the effects of donor with respect to anatomic site.

3. Results

The architecture differed between anatomic sites (Table 1). The initial elastic and shear moduli were independent of group within each anatomic site (p > 0.4, Table 2). The Young’s and shear moduli increased with BV/TV and were higher in the femoral neck than in the trochanter with donor treated as a random effect (p < 0.01). In contrast, neither the compressive (p > 0.82), shear (p > 0.40), nor multiaxial (p > 0.11) yield strains depended on BV/TV, architecture, or anatomic site (p > 0.5, paired T-test). The overload strain was about 2.4 times the yield strain in compression, and 2.6 times the yield strain in shear. In multiaxial loading, the applied overload strains were approximately 2.5 times higher than the compressive and shear yield strains.

Table 2.

Mean (± S.D.) of the mechanical properties of the samples.* Bold entries are significantly different between, the neck and trochanter (p < 0.05, mixed model ANOVA). Note that yield and ultimate properties were only measured during the associated loading mode.

| Group I (compression) | Group II (shear) | Group III (multiaxial) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neck | Trochanter | Neck | Trochanter | Neck | Trochanter | |

| Ei (MPa) | 551±227 | 343 ± 74 | 515 ± 192 | 312 ± 94 | 452 ± 154 | 345 ± 102 |

| Ed (MPa) | 496 ± 218 | 292 ± 83 | 463 ± 160 | 282 ± 80 | 378±144 | 279±69 |

| εyield (%) | 0.85 ± 0.15 | 0.84 ± 0.09 | - | - | 0.43 ± 0.13 | 0.57 ± 0.22 |

| σyield (MPa) | 2.04 ± 0.82 | 1.16 ± 0.28 | - | - | 0.99 ± 0.58 | 1.16 ± 0.50 |

| σult (MPa) | 3.96 ± 1.92 | 2.49 ± 0.78 | - | - | 196 ±1.13 | 1.99±1.18 |

| Gi (MPa) | 114 ± 49 | 60 ± 25 | 94±48 | 62 ± 17 | 109 ± 57 | 58 ± 32 |

| Gd (MPa) | 92 ± 36 | 57 ± 24 | 81 ± 45 | 47 ± 18 | 83 ± 47 | 49 ± 34 |

| γyield (%) | - | - | 1.48 ± 0.31 | 1.59 ± 0.27 | 0.86 ± 0.25 | 1.15 ± 0.45 |

| τyield (MPa) | - | - | 1.17 ± 0.54 | 0.86 ± 0.28 | 0.66 ± 0.39 | 0.47 ± 0.21 |

| τult (MPa) | - | - | 2.36 ± 0.78 | 2.04±0.48 | 1.35 ± 0.68 | 1.00 ± 0.30 |

Compressive properties: initial (Ei) and damaged (Ed) elastic moduli, yield strain (εyield), yield stress (σyield), and ultimate strength (σult). Shear properties: initial (Gi) and damaged (Gd) moduli, yield strain (γyield), yield stress (τyield), and ultimate strength (τult).

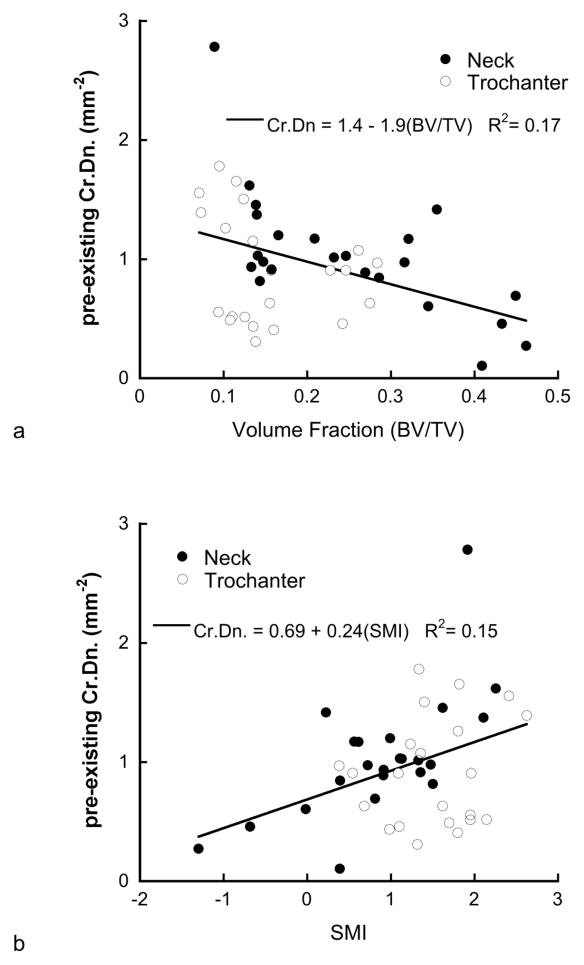

Pre-existing microcrack density did not depend on site (Table 1), but depended on trabecular architecture (Table 3). Crack density was negatively correlated with BV/TV (p < 0.001; Fig. 3), increasing with degree of anisotropy (p < 0.03) independent of site (p > 0.33), gender (p > 0.5), age (p > 0.25), and TMD (p > 0.8). Alternately, if BV/TV was excluded from the model, the regression was positively correlated with SMI. Pre-existing Cr.Ln decreased with increasing SMI (p < 0.001) and increasing BV/TV (p = 0.05) simultaneously. However, if SMI was excluded from the model, there was no dependence on BV/TV (p>0.6). Cr.Ln was lower in the trochanter than in the femoral neck (p < 0.001; Table 1), and was independent of gender, age, TMD, or other architectural parameters (p > 0.1).

Table 3.

Pearson correlation coefficients for architectural and damage measures

| BV/TV | Tb.Th | Slenderness | SMI | Conn.D | Tb.N | DA | Cr.Dn pre-existing | Cr.Dn new | Cr.Dn propagating | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BV/TV | 1.0 | 0.84* | −0.84* | −0.84* | 0.71* | 0.83* | 0.14 | −0.52* | −0.39* | −0.36† |

| Tb.Th | 1.0 | −0.79* | −0.68* | 0.36† | 0.53* | 0.28 | −0.51* | −0.38† | −0.40* | |

| Slenderness | 1.0 | 0.63* | −0.66* | −0.81* | −0.02 | 0.56* | 0.40† | 0.30† | ||

| SMI | 1.0 | −0.46* | −0.59* | −0.35† | 0.38* | 0.35† | 0.36† | |||

| Conn.D | 1.0 | 0.95* | −0.31* | −0.34† | −0.20 | −0.09 | ||||

| Tb.N | 1.0 | −0.19 | −0.41* | −0.26 | −0.15 | |||||

| DA | 1.0 | 0.05 | −0.13 | −0.27 | ||||||

| Cr.Dn pre-existing | 1.0 | 0.58* | 0.55* | |||||||

| Cr.Dn new | 1.0 | 0.42* | ||||||||

| Cr.Dn propagating | 1.0 |

p < 0.01;

p < 0.05

Figure 3.

Pre-existing Cr.Dn decreased with volume fraction (p = 0.0026) or separately increased with increasing SMI (p = 0.002), but the regression did not depend on anatomic site (p > 0.4, mixed GLM).

Under torsional and multiaxial loading, the initiation and propagation of cracks increased with distance from the specimen axis, consistent with increasing applied strain (p < 0.0001, ANOVA, Fig. 4). In contrast, damage due to compressive overloading did not depend on radius(p > 0.2, ANOVA; Fig. 4) consistent with the uniform strain state. In order to compare regions with similar levels of principal compressive strain, only microdamage in the outer 1/3 of the radius was included in inter-group comparisons for groups II and III.

Figure 4.

Microdamage distribution across the specimen radius (I=inner 1/3, M=mid 1/3, and O=outer 1/3 of radius). Both initiating and propagating Cr.Dn were uniform across the radius after compressive overloading (p > 0.2, ANOVA), while both were higher at the periphery of the sample following torsional or multiaxial overloading (p < 0.0001, ANOVA). * p < 0.0001 for initiated crack density, + p < 0.0001 for propagated crack density. Data are mean values from N=14, 16, and 15 samples in compression, shear, and multiaxial loading, respectively.

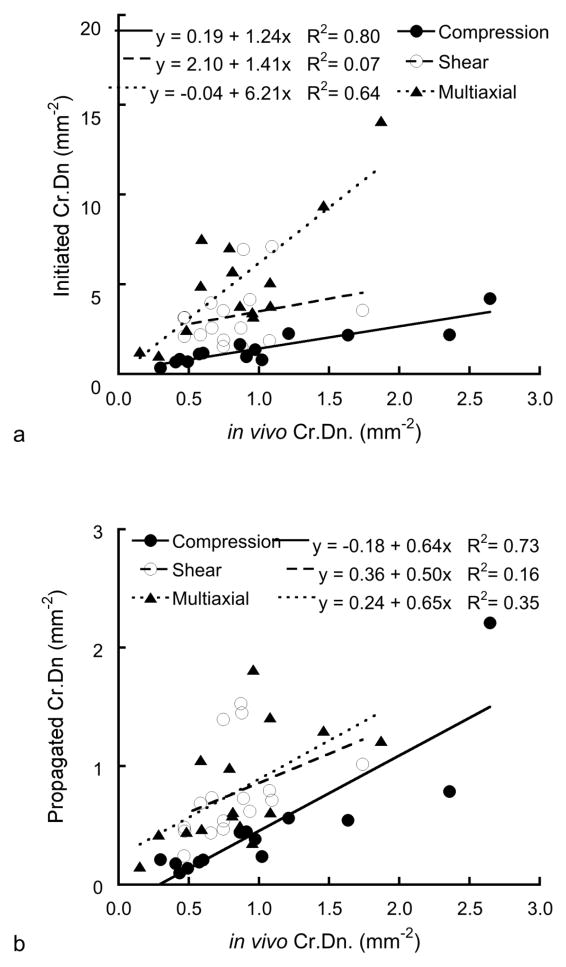

The initiating Cr.Dn increased with increasing pre-existing Cr.Dn (p < 0.01, Fig. 5a) and SMI or decreasing BV/TV when SMI was excluded from the analysis (p < 0.0002). The initiating Cr.Dn did not depend on age, gender, (p > 0.15) or anatomic site (p > 0.4). Initiating Cr.S.Dn similarly increased with pre-existing Cr.S.Dn following compressive and multiaxial overloading (p < 0.02) independent of architecture or BV/TV (p > 0.2), but not for shear loading (p > 0.5).

Figure 5.

The initiating (a) Cr.Dn and propagating (b) Cr.Dn during ex vivo overloading increased with increasing pre-existing Cr.Dn for all three overloading modes (p b 0.001, GLM). The model included dependence on SMI. Both initiating and propagating Cr.Dn were lower in the compressive overloading group than in the other groups, and the slopes were lower in the trochanter than in the femoral neck

The propagated Cr.Dn increased with increasing pre-existing Cr.Dn (p < 0.0002) and SMI (p < 0.002, Fig. 5b), but did not correlate with BV/TV even when SMI was excluded from the model. There were no differences in the dependence of propagating Cr.Dn on SMI or pre-existing Cr.Dn between groups (p > 0.3), but the slope was higher in the neck than in the trochanter (p < 0.05). On average, the propagating Cr.Dn was lower for compressive loading than for shear or multiaxial loading, after compensating for SMI and pre-existing Cr.Dn (p < 0.001). The propagating Cr.S.Dn. also increased with increasing pre-existing Cr.S.Dn (p < 0.0001), independent of SMI, BV/TV or other architectural parameters (p > 0.3). The slope of this regression was higher in the neck than in the trochanter (p < 0.0001).

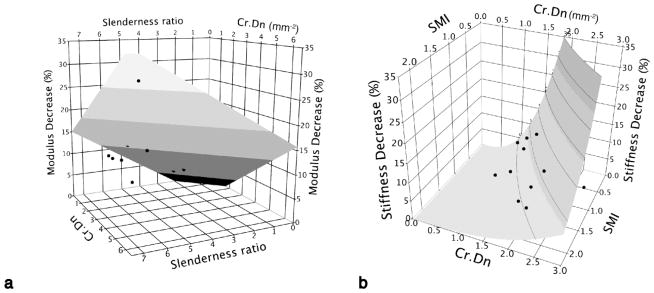

All three overloading modes caused a decrease in both axial and torsional stiffness. The relative stiffness loss in the multiaxial group was greater than the shear group (mixed model ANOVA, p < 0.03, Fig. 6). The degradation in the axial stiffness exhibited a power law relationship with induced (initiating + propagating) Cr.Dn, with a dependence on group, but independent of BV/TV, SMI, or other architecture parameters (R2=0.34, p < 0.001, ANCOVA). As theoretical models suggest that the loading orientation with respect to the architecture affects damage formation [41], each group was further analyzed separately. Moreover, previous studies have indicated that SMI and slenderness are strong predictors of modulus degradation due to overloading [12]. There was a power law relationship between microcrack formation and stiffness loss in the shear group, decreasing with SMI (R2=0.45, p < 0.05), and a linear relationship in axial loading, decreasing with SMI and increasing with trabecular slenderness (R2=0.81, p < 0.02; Fig. 7). Neither yield stress nor strain depended on microcracking (p > 0.2).

Figure 6.

The relative decreases in the axial and torsional stiffness following multiaxial overloading were greater than that following compression or shear (p < 0.03, ANOVA). Data are mean ± one S.D.

Figure 7.

a) The relative decrease in the compressive stiffness increased with the density of new + propagating cracks and trabecular slenderness (Tb.Sp/Tb.Th), and decreased with SMI: ΔE = 3.25Cr.Dn + 2.72(Slenderness ratio) − 5.12SMI (R2=0.81). b) Following torsional loading, the loss of compressive stiffness increased approximately cubically with new + propagating Cr.Dn, and decreased with SMI: log(ΔE) = 2.93log(Cr.Dn) − 1.28SMI +1.80(R2=0.42).

4. Discussion

Microdamage formation and propagation in trabecular bone may play a role in increasing bone fragility by reducing bone mechanical properties, or it may be a hallmark of bone with compromised architecture or tissue properties making it susceptible to further damage. In this study, in vivo damage density was positively correlated with lower BV/TV or with higher SMI, indicating that architectural deterioration increases the susceptibility to damage in human trabecular bone in situ. When subjected to further overloading, approximately half of the existing in vivo damage propagated, while substantial new damage was also formed in proportion to the pre-existing damage. Cracks were more likely to propagate when shear strains were applied vs. compressive loads, and depended on SMI but not volume fraction. Hence, both existing microdamage, which can propagate under additional loading, and deficient trabecular architecture are hallmarks of further damage risk that will lead to degradation of modulus and strength.

The results of this study provide new insight into microdamage initiation and propagation in human femoral trabecular bone. Because the methods differentiated the in vivo, propagating, and newly initiated microcracks in each specimen, it was possible to examine how microdamage accumulates and evolves during loading. The application of multiple loading modes provides insight into both normal loading, represented by compression along the principal axis, and uncommon loading represented by shear and multiaxial loading.

Several limitations to this study must also be considered. First, only microcracks were quantified. The interest in this study was the propagation of microdamage from pre-existing damage. While no new cracks were found emanating from diffuse damage regions, torsional loading of damaged bone as been shown to result in greater diffuse damage and microcracking than in undamaged bone [16]. However, in vivo diffuse damage is not directly related to microcracking [1, 3], so that while both increase in damaged bone, they are considered independent processes. The dependence of microcrack propagation and formation on diffuse damage could be an important aspect of bone health, but it was not addressed in this work. Second, the donors in the study were all over 50 yrs. of age. In studies over a broader age range, Cr.Dn increases nonlinearly with age [23], and trabeculae from younger individuals can sustain higher stresses prior to microdamage initiation [10]. In the present study, no relationship between microdamage and age was noted, suggesting that the results hold only for older individuals. However, this is reasonable, because older individuals are at highest risk for osteoporotic fractures. Another limitation is that the subjects were not screened for osteoarthritis, which affects the mean crack length [23, 24], but not the crack density. While they were not screened for osteoporosis, (BV/TV) correlates to BMD measured by dual energy x-ray aborptiometry [42], and the effects of decreased bone density would have been compensated for in the analysis. Finally, only femoral trabecular bone was studied. While some results are in concordance with studies of vertebral trabecular bone [3], the results cannot be immediately extended to other sites.

The correlation of microdamage with deteriorated architectural parameters is consistent with previous studies. In vivo microdamage accumulation in human vertebral trabecular bone [3] and overloading induced damage in bovine tibial trabecular bone [43] are both positively correlated with SMI, negatively correlated with BV/TV, and positively with high strains in rod-like trabeculae [18]. Previous studies have similarly implicated bending and buckling of rod-like trabeculae with the failure process [44]. As such, deteriorated architecture and microdamage formation are co-contributors to degradation in mechanical properties. Overall, higher SMI was the best predictor of increased damage risk – in agreement with results for the tibia [43]. Indeed, only SMI was correlated to damage propagation, although either higher SMI or lower BV/TV were predictors of the risk of new damage formation. However, at present, volume fraction may be the best outcome variable from a diagnostic standpoint, due to limitations in measuring detailed architecture in a clinical setting.

In addition to deteriorated architecture and decreased volume fraction, microdamage is associated with resorption cavities in trabecular bone [45]. Together, these indicators of damage risk suggest that treatments that decrease the formation of resorption cavities, and simultaneously slow the degradation of architecture and volume fraction, could also slow microdamage accumulation [46]. However, the increased mineralization and suppressed remodeling associated with some of these agents have been postulated to decrease the fracture toughness.

The loading mode had a substantial effect on formation of microdamage. On average, the multiaxial overload led to 60% higher Cr.Dn than shear overloading and nearly three times greater than compressive overloading. This difference was primarily due to the initiation of new cracks, as about ½ of existing cracks propagating during the overload when the principal strain exceeded 2% for all overloading modes. Computational models have demonstrated that changes in the macroscopic loading mode alter the trabeculae that bear the majority of the load or alter the stress states in those trabeculae [17, 47–49]. In these samples, shear and multiaxial loading resulted in greater crack propagation, which may be due to the change in stress state allowing arrested cracks to deflect around microstructural elements.

Pre-existing damage differed between the trochanter and in the femoral neck, as has been reported previously [23]. Differences in the pre-existing damage may reflect that the trochanteric region is subjected to tension in vivo, compared to compression in the neck. Crack formation and propagation also depended on site for the controlled ex vivo loads applied here, with propagation of cracks more common in the neck than in the trochanter. This may reflect that the loading in the neck is more uniform and aligned in vivo [50, 51], and altered loading thereby propagates cracks more easily. Differences in the tissue level properties, such as the hardness, modulus, or viscoelastic properties [52] might also explain these differences, but were not measured in the present samples.

The correlation between microcrack formation during loading and stiffness loss confirms the expected relationship between damage and mechanical properties, and previous results for cortical bone [9]. The relationship depended on the applied loading, consistent with a theoretical model of damage [41]. The relationship was also sensitive to SMI, consistent with computational models indicating that rod-like trabeculae are associated with microdamage [18, 47], and to slenderness ratio, as was demonstrated as a factor in stiffness loss during damage of bovine trabecular bone [11].

Taken together, the results reinforce the concept that microdamage burden is detrimental to bone health, because it increases the risk of further damage formation and decreases both modulus and strength in a potentially in-virtuous cycle. In vivo damage was an indicator of increased susceptibility to both new damage initiation and crack propagation, resulting in mechanical property degradation. Hence, microdamage and microarchitectural deterioration are both important measures of bone quality.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Human femoral trabecular bone was overloaded in one of compression, torsion, or multiaxial loading.

Pre-existing and loading induced microdamage formation were differentially quantified.

Pre-existing microdamage was higher in the trochanter and was positively correlated to induced microdamage.

Stiffness decreased with microdamage initiation and propagation during overloading.

Pre-existing microdamage is indicative of susceptibility to further damage, and microdamage negatively impacts mechanical behavior.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health: AR052008. Tissue was procured through the National Disease Research Interchange.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Vashishth D, Koontz J, Qiu SJ, Lundin-Cannon D, Yeni YN, Schaffler MB, Fyhrie DP. In vivo diffuse damage in human vertebral trabecular bone. Bone. 2000;26:147–152. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(99)00253-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yeni YN, Hou FJ, Ciarelli T, Vashishth D, Fyhrie DP. Trabecular shear stresses predict in vivo linear microcrack density but not diffuse damage in human vertebral cancellous bone. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2003;31:726–732. doi: 10.1114/1.1569264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arlot ME, Burt-Pichat B, Roux JP, Vashishth D, Bouxsein ML, Delmas PD. Microarchitecture influences microdamage accumulation in human vertebral trabecular bone. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2008;23:1613–8. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mashiba T, Turner CH, Hirano T, Forwood MR, Johnston CC, Burr DB. Effects of suppressed bone turnover by bisphosphonates on microdamage accumulation and biomechanical properties in clinically relevant skeletal sites in beagles. Bone. 2001;28:524–31. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00414-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mashiba T, Hirano T, Turner CH, Forwood MR, Johnston CC, Burr DB. Suppressed bone turnover by bisphosphonates increases microdamage accumulation and reduces some biomechanical properties in dog rib. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2000;15:613–620. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.4.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Komatsubara S, Mori S, Mashiba T, Li J, Nonaka K, Kaji Y, Akiyama T, Miyamoto K, Cao Y, Kawanishi J, Norimatsu H. Suppressed bone turnover by long-term bisphosphonate treatment accumulates microdamage but maintains intrinsic material properties in cortical bone of dog rib. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2004;19:999–1005. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brennan O, Kennedy OD, Lee TC, Rackard SM, O’Brien FJ. Effects of estrogen deficiency and bisphosphonate therapy on osteocyte viability and microdamage accumulation in an ovine model of osteoporosis. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2011;29:419–24. doi: 10.1002/jor.21229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoshaw SJ, Cody DD, Saad AM, Fyhrie DP. Decrease in canine proximal femoral ultimate strength and stiffness due to fatigue damage. Journal of Biomechanics. 1997;30:323–329. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(96)00159-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burr DB, Turner CH, Naick P, Forwood MR, Ambrosius W, Hasan MS, Pidaparti R. Does microdamage accumulation affect the mechanical properties of bone? Journal of Biomechanics. 1998;31:337–45. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(98)00016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green JO, Nagaraja S, Diab T, Vidakovic B, Guldberg RE. Age-related changes in human trabecular bone: Relationship between microstructural stress and strain and damage morphology. Journal of Biomechanics. 2011;44:2279–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garrison JG, Gargac JA, Niebur GL. Shear strength and toughness of trabecular bone are more sensitive to density than damage. J Biomech. 2011;44:2747–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garrison JG, Slaboch CL, Niebur GL. Density and architecture have greater effects on the toughness of trabecular bone than damage. Bone. 2009;44:924–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Follet H, Viguet-Carrin S, Burt-Pichat B, Depalle B, Bala Y, Gineyts E, Munoz F, Arlot M, Boivin G, Chapurlat RD, Delmas PD, Bouxsein ML. Effects of preexisting microdamage, collagen cross-links, degree of mineralization, age, and architecture on compressive mechanical properties of elderly human vertebral trabecular bone. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2011;29:481–8. doi: 10.1002/jor.21275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Brien FJ, Taylor D, Lee TC. Microcrack accumulation at different intervals during fatigue testing of compact bone. Journal of Biomechanics. 2003;36:973–80. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(03)00066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nalla RK, Stolken JS, Kinney JH, Ritchie RO. Fracture in human cortical bone: local fracture criteria and toughening mechanisms. Journal of Biomechanics. 2005;38:1517–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang X, Niebur GL. Microdamage propagation in trabecular bone due to changes in loading mode. Journal of Biomechanics. 2006;39:781–790. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi X, Wang X, Niebur GL. Effects of loading orientation on the morphology of the predicted yielded regions in trabecular bone. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2009;37:354–62. doi: 10.1007/s10439-008-9619-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi X, Liu X, Wang X, Guo XE, Niebur GL. Effects of trabecular type and orientation on microdamage susceptibility in trabecular bone. Bone. 2010;46:1260–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arthur Moore TL, Gibson LJ. Microdamage accumulation in bovine trabecular bone in uniaxial compression. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 2002;124:63–71. doi: 10.1115/1.1428745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burr DB. Remodeling and the repair of fatigue damage. Calcified Tissue International. 1993;53:S75–80. doi: 10.1007/BF01673407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaffler MB. Role of bone turnover in microdamage. Osteoporosis International. 2003;14 (Suppl 5):73–80. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1477-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang XS, Guyette J, Liu X, Roeder RK, Niebur GL. Axial-shear interaction effects on microdamage in bovine tibial trabecular bone. European Journal of Morphology. 2005;42:61–70. doi: 10.1080/09243860500095570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fazzalari NL, Kuliwaba JS, Forwood MR. Cancellous bone microdamage in the proximal femur: influence of age and osteoarthritis on damage morphology and regional distribution. Bone. 2002;31:697–702. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(02)00906-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fazzalari NL, Forwood MR, Smith K, Manthey BA, Herreen P. Assessment of Cancellous Bone Quality in Severe Osteoarthrosis: Bone Mineral Density, Mechanics, and Microdamage. Bone. 1998;22:381–388. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(97)00298-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang X, Liu X, Niebur GL. Preparation of on-axis cylindrical trabecular bone specimens using micro-CT imaging. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 2004;126:122–125. doi: 10.1115/1.1645866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Rietbergen B, Odgaard A, Kabel J, Huiskes R. Direct mechanics assessment of elastic symmetries and properties of trabecular bone architecture. Journal of Biomechanics. 1996;29:1653–1657. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(96)00093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Turner CH, Cowin SC. Dependence of elastic constants of an anisotropic porous material upon porosity and fabric. Journal of Material Science. 1987;22:3178–84. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turner CH, Cowin SC. Errors Introduced by Off-Axis Measurements of the Elastic Properties of Bone. Journal of Biomechanics. 1988;110:213–214. doi: 10.1115/1.3108433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zysset PK, Curnier A. An Alternative Model For Anisotropic Elasticity Based On Fabric Tensors. Mechanics of Materials. 1995;21:243–250. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lotz JC, Cheal EJ, Hayes WC. Stress distributions within the proximal femur during gait and falls: implications for osteoporotic fracture. Osteoporos Int. 1995;5:252–61. doi: 10.1007/BF01774015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wachtel E, Keaveny TM. Dependence of trabecular damage on mechanical strain. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 1997;15:781–7. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100150522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arthur Moore TL, Gibson LJ. Fatigue of bovine trabecular bone. J Biomech Eng. 2003;125:761–8. doi: 10.1115/1.1631583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arthur Moore TL, Gibson LJ. Fatigue microdamage in bovine trabecular bone. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 2003;125:769–76. doi: 10.1115/1.1631584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morgan, Yeh, Keaveny Damage in trabecular bone at small strains. European journal of morphology. 2005;42:13–21. doi: 10.1080/09243860500095273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morgan EF, Yeh OC, Chang WC, Keaveny TM. Nonlinear behavior of trabecular bone at small strains. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 2001;123:1–9. doi: 10.1115/1.1338122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nadai A. Torsion of a round bar. The stress-strain curve in shear. In: Nadai A, editor. Theory of Flow and Fracture of Solids. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1950. pp. 347–352. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keaveny TM, Pinilla TP, Crawford RP, Kopperdahl DL, Lou A. Systematic and random errors in compression testing of trabecular bone. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 1997;15:101–110. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100150115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ford CM, Keaveny TM. The dependence of shear failure properties of bovine tibial trabecular bone on apparent density and trabecular orientation. Journal of Biomechanics. 1996;29:1309–1317. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(96)00062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Brien FJ, Taylor D, Lee TC. An improved labelling technique for monitoring microcrack growth in compact bone. Journal of Biomechanics. 2002;35:523–526. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00200-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Green JO, Wang J, Diab T, Vidakovic B, Guldberg RE. Age-related differences in the morphology of microdamage propagation in trabecular bone. Journal of Biomechanics. 2011;44:2659–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zysset PK, Curnier A. A 3D damage model for trabecular bone based on fabric tensors. Journal of Biomechanics. 1996;29:1549–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perilli E, Briggs AM, Kantor S, Codrington J, Wark JD, Parkinson IH, Fazzalari NL. Failure strength of human vertebrae: prediction using bone mineral density measured by DXA and bone volume by micro-CT. Bone. 2012;50:1416–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karim L, Vashishth D. Role of trabecular microarchitecture in the formation, accumulation, and morphology of microdamage in human cancellous bone. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2011;29:1739–44. doi: 10.1002/jor.21448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bevill G, Eswaran SK, Gupta A, Papadopoulos P, Keaveny TM. Influence of bone volume fraction and architecture on computed large-deformation failure mechanisms in human trabecular bone. Bone. 2006;39:1218–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Slyfield CR, Tkachenko EV, Fischer SE, Ehlert KM, Yi IH, Jekir MG, O’Brien RG, Keaveny TM, Hernandez CJ. Mechanical failure begins preferentially near resorption cavities in human vertebral cancellous bone under compression. Bone. 2012;50:1281–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.02.636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Allen MR, Burr DB. Bisphosphonate effects on bone turnover, microdamage, and mechanical properties: What we think we know and what we know that we don’t know. Bone. 2011;49:56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.10.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shi X, Liu XS, Wang X, Guo XE, Niebur GL. Type and orientation of yielded trabeculae during overloading of trabecular bone along orthogonal directions. Journal of Biomechanics. 2010;43:2460–2466. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Niebur GL, Feldstein MJ, Yuen JC, Chen TJ, Keaveny TM. High resolution finite element models with tissue strength asymmetry accurately predict failure of trabecular bone. Journal of Biomechanics. 2000;33:1575–1583. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(00)00149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu X, Wang X, Niebur GL. Effects of damage on the orthotropic material symmetry of bovine tibial trabecular bone. Journal of Biomechanics. 2003;36:1753–1759. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(03)00217-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bergmann G, Deuretzbacher G, Heller M, Graichen F, Rohlmann A, Strauss J, Duda GN. Hip contact forces and gait patterns from routine activities. Journal of Biomechanics. 2001;34:859–71. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bergmann G, Graichen F, Rohlmann A. Load Direction at Hip Prosthesis Measured in vivo. Journal of Biomechanics. 1989;22:986. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu Z, Ovaert TC, Niebur GL. Viscoelastic properties of human cortical bone tissue depend on gender and elastic modulus. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2012;30:693–9. doi: 10.1002/jor.22001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.