Abstract

The PDC-HS implicated a lack of proper training on participant duties and a lack of performance feedback as contributors to the performance problems. As a result, an intervention targeting training on participant duties and performance feedback was implemented across eight treatment rooms; the intervention increased performance in all rooms. This preliminary validation study suggests the PDC-HS may prove useful in solving performance problems in human-service settings.

PRACTICE POINTS.

The Performance Diagnostic Checklist (PDC) has been used in a number of investigations to assess the environmental determinants of poor employee performance.

The PDC was revised to explicitly assess the performance of employees in human-service settings who are responsible for providing care to others: the Performance Diagnostic Checklist – Human Services (PDC-HS).

The PDC-HS was implemented at a center-based autism treatment facility to identify the variables contributing to employees' poor cleaning of treatment rooms.

Functional assessment has become the standard of care for identifying the function of problem behavior in clinical and educational environments (Hanley, Iwata, & McCord, 2003). An approach akin to functional assessment has existed in organizational settings for years. Often termed performance analysis or performance diagnostics (Austin, 2000), this approach is used to identify the variables that influence an employee's substandard job performance. These influences can include insufficient task training, insufficient consequences for task performance, and competing contingencies, among others. As with functional assessment, performance analysis is conducted in order to develop a more precise intervention that is conceptually linked to the variables responsible for the performance problem. For example, retraining would not be the optimal solution for an employee's poor performance if said performance was largely a function of poorly designed work materials, as opposed to a skill deficit (for which retraining would be functionally matched).

Operant models for conducting performance analysis have been proposed since the 1970s (e.g., Daniels, 1989; Gilbert, 1978; Mager & Pipe, 1970) and they all share the behavior-analytic characteristics of operationalizing skill deficits or excesses, considering environmental antecedents and consequences, and, ostensibly, linking treatment to assessment results. However, these models have resulted in very little research in the organizational behavior management (OBM) literature (Austin, Carr, & Agnew, 1999). By contrast, a more recent performance analysis tool has influenced a number of empirical investigations. The Performance Diagnostic Checklist (PDC; Austin, 2000) is an informant assessment that is used to identify variables that may impact poor performance. The PDC is comprised of 20 items and is typically conducted by interviewing managers and supervisors about factors in four domains: antecedents and information, equipment and processes, knowledge and skills, and consequences. Multiple deficits in a specific area generally lead to subsequent prescribed intervention.

A number of recent empirical investigations have employed the PDC to help solve employee performance problems. For example, Rodriguez et al. (2005) studied restaurant workers who did not offer promotional stamps to customers on a frequent basis. The PDC identified insufficient consequences for the task and a subsequent treatment package that included feedback produced large improvements in the target behavior. Austin, Weatherly, and Gravina (2005) studied restaurant workers who did not sufficiently perform closing tasks. The PDC identified a “knowledge” deficit and a subsequent treatment package that included task clarification and feedback produced reliable performance increases across two employee classes. Eikenhout and Austin (2005) used the PDC to develop an intervention to improve customer service by department store workers. The PDC identified insufficient consequences for the task and a subsequent treatment package that included feedback and praise produced reliable performance improvements. In a final example, Pampino, Heering, Wilder, Barton, and Burson (2003) used the PDC to develop an intervention to increase maintenance tasks performed by workers in a coffee shop. The PDC identified insufficient prompts and consequences for the tasks and a treatment package containing task clarification and a staff lottery produced large performance improvements.

Although the PDC has been helpful in the development of performance interventions for workers in private industry, it has not yet been applied to the performance of workers in human-service settings. Organizational behavior management has long been demonstrated as a successful approach to training and maintaining the repertoires of staff who deliver educational and therapeutic services (Reid & Parsons, 2000). However, maintenance of performance in such settings has been problematic, perhaps as a result of task difficulty and low educational requirements for many of these jobs. Poor performance in a human-service agency can negatively impact the health and rate of improvement of those who are served, in addition to the agency's financial health. To the extent that the PDC has been causally related to the improvements reported in the recent performance analysis literature, its contribution to human-service performance problems warrants investigation.

We developed a version of the PDC to explicitly assess the performance of employees in human-service settings who are responsible for providing care to others: the Performance Diagnostic Checklist – Human Services (PDC-HS).

The PDC was designed primarily for business and industry; thus, there are a number of items that are not directly relevant to human-service environments. For example, the PDC's section on “Equipment and Processes” includes the following questions: “If equipment is required, is it reliable?”; “Is it in good working order?”; and “Is it ergonomically correct?” Although equipment is sometimes used in human-service settings, the presence of irrelevant items or items that need to be translated into more contextually relevant terms might diminish the instrument's utility. Thus, we developed a version of the PDC to explicitly assess the performance of employees in human-service settings who are responsible for providing care to others: the Performance Diagnostic Checklist – Human Services (PDC-HS). The development process is described later.

The PDC-HS, like the PDC, was designed to be used by practitioners to help identify environmental determinants that might contribute to employee performance problems. The daily activities of many practicing behavior analysts frequently involve the oversight of staff responsible for behavior plan implementation. Although the behavioral literature contains successful demonstrations of staff management procedures (e.g., Burgio et al., 1990), many of these involve default procedures such as feedback that are not necessarily matched to the determinants of the performance problem. The PDC-HS may be useful to practicing behavior analysts by (a) helping them understand performance problems that do not respond to simple and quick solutions, and (b) by helping them develop a more sensitive, targeted intervention for those performance problems.

The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the utility of the PDC-HS in the selection of treatments for human-service performance problems. The context for the evaluation was an early and intensive behavioral intervention (EIBI) center serving children with autism. The present study also extended the existing PDC literature by evaluating the instrument's predictive validity. Although the PDC has influenced a number of recent studies, none of them included a nonfunction-based treatment comparison. That is, all of the studies evaluated a treatment (or treatment package) that was influenced by PDC results, but none evaluated a treatment that was not suggested by the PDC. Such an approach has been used to assess the predictive validity of functional analysis procedures in the treatment of problem behavior in clinical environments (e.g., Iwata, Pace, Cowdery, & Miltenberger, 1994). An assessment of predictive validity is particularly relevant to the PDC because the majority of intervention components (e.g., task clarification, feedback) evaluated in this line of research have often been demonstrated as effective in the absence of performance analysis (e.g., Nolan, Jarema, & Austin, 1999). Thus, the ultimate contribution of the information obtained from the PDC to the reported treatment outcomes is largely unknown. The present study included a nonfunction-based treatment comparison to assess the predictive validity of the PDC-HS.

Method

Setting, Participants, and Materials

The present study was conducted at a university-based autism treatment center in the southeastern United States. The center provided EIBI services to children between 3 and 7 years of age. Eight treatment rooms were used for the evaluation, each of which was approximately 3 m by 3 m in size. Therapists assigned to work with children were responsible for cleaning and arranging their treatment rooms at the end of each 1.5 hr treatment session. We selected specific rooms that were not kept clean as targets during the study.

Participants included 15 staff members who were graduate-student employees at the treatment center. All participants were female, between the ages of 23 and 27, and enrolled in a master's degree program in applied behavior analysis. More than one participant worked in some rooms, but no participant worked in more than one room. Participants worked as one-on-one therapists providing EIBI services to young children with autism. Upon hire, approximately 1 month before the current study began, all participants were trained to perform all of the therapy room-cleaning duties listed in Appendix A. This training included taking them into the room, describing all of the tasks, and showing them where the necessary materials were located.

Materials included a checklist (Appendix A) describing items that the participants were responsible for cleaning (tailored to each room), a graph that was posted on the wall in each target room for delivery of daily feedback during the intervention phase, the PDC-HS (see Appendix B), and a video camera. Additional materials included items that were specified on the checklist: disinfectant wipes, gloves, tissues, and a fully stocked first aid kit.

The PDC-HS

Development. The PDC-HS was developed to assess the environmental determinants of human-service staff performance problems. The development process began with questions from the original PDC (Austin, 2000) being applied to the following common human-service performance problems: poor treatment implementation, inaccurate data collection, inadequate development of program materials, poor attendance/tardiness, failure to report problems to supervisors, and poor graph construction. This process identified numerous areas for revision. The PDC's section titles, section order, question wording, and question order were then revised to better match human-service contexts and problems. Besides the authors of this article, 11 behavior analysts then provided input into the wording of the questions after being asked to review and pilot test the assessment. These professionals had an average of 12 years (range, 4 to 35) working in human-service settings. Nine of them held doctoral degrees and 10 of them were Board Certified Behavior Analysts® (BCBAs®). After the final revisions were made, the PDC-HS was evaluated in the present study.

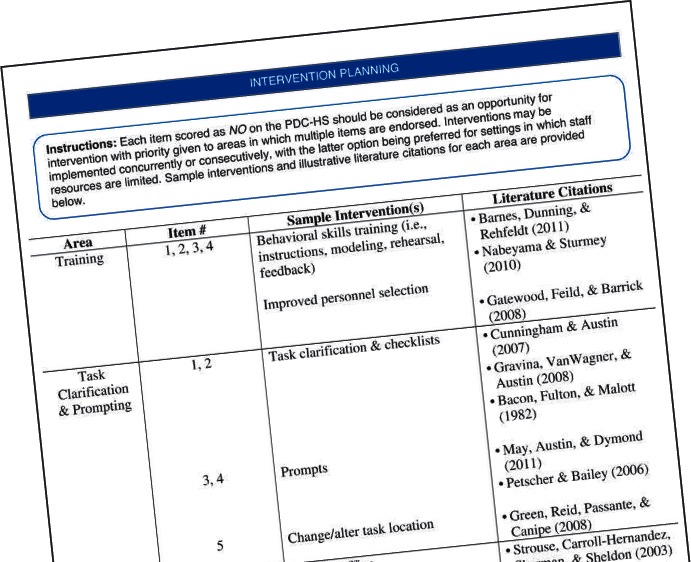

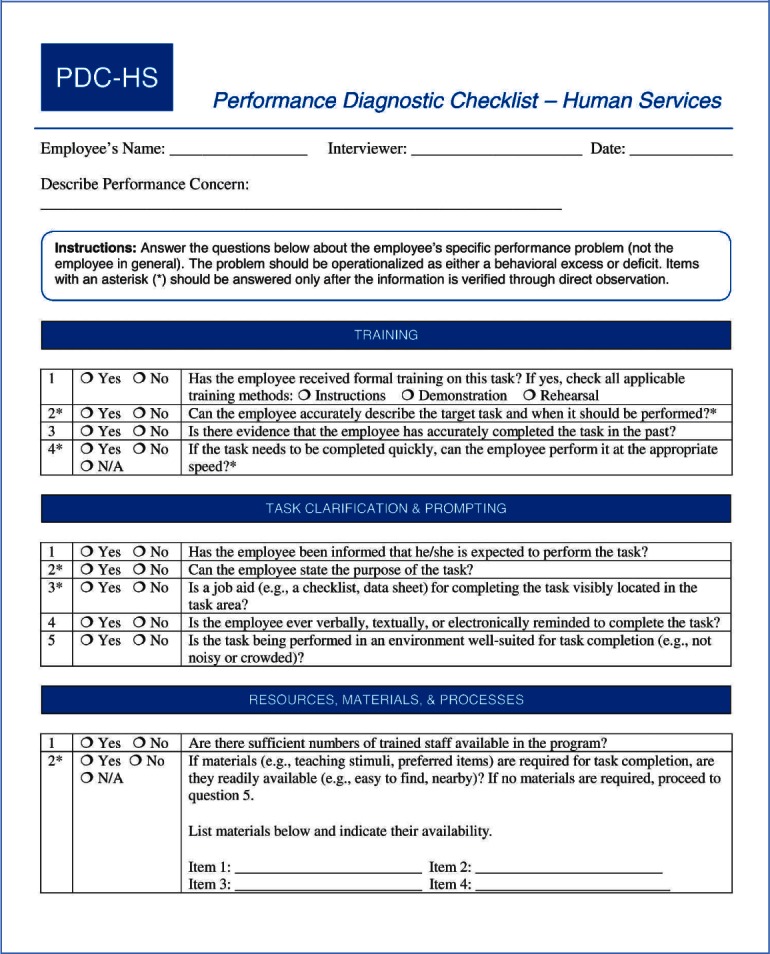

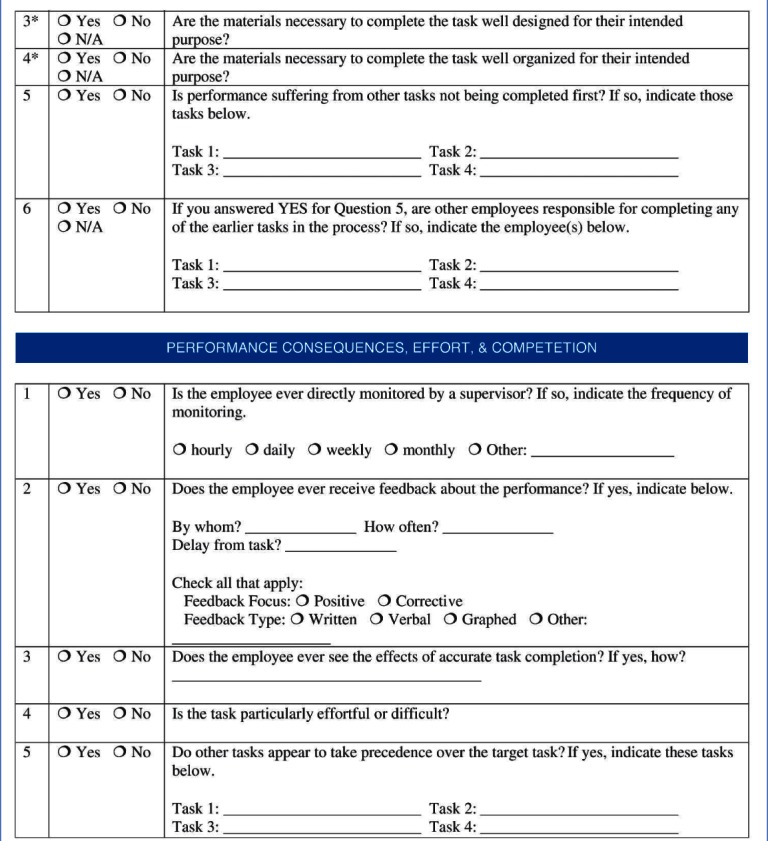

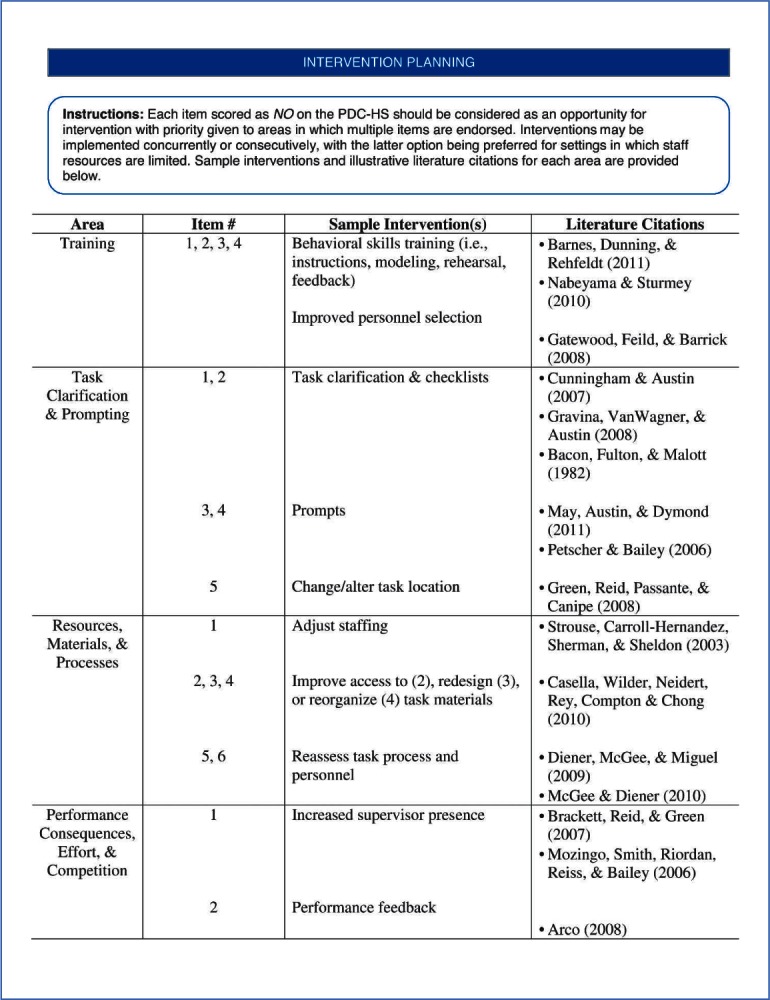

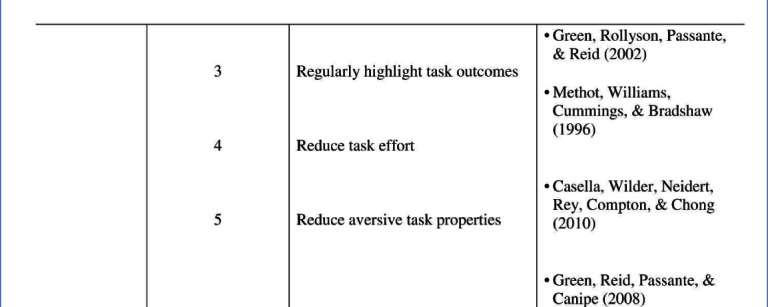

Administration. The PDC-HS consists of 20 questions organized into the following four sections: (a) Training; (b) Task Clarification & Prompting; (c) Resources, Materials, & Processes; and (d) Performance Consequences, Effort, and Competition. Each of the four sections includes 4 to 6 questions about task performance. The assessment is designed to be used by a behavior analyst during an interview with the employee's direct supervisor or manager. Thirteen of the questions may be answered based on informant report and 7 should be answered via direct observation. Each item scored as No on the PDC-HS should be considered as an opportunity for intervention, with priority given to areas in which multiple items are endorsed. Interventions may be implemented concurrently or consecutively, with the latter option being preferred for settings in which staff resources are limited. Sample interventions and illustrative literature citations for each area are provided at the end of the assessment.

Data Collection and Interobserver Agreement

The dependent measure was the percentage of tasks correctly completed on the treatment room cleanliness checklist (Appendix A). Checklists differed slightly depending on the arrangement of the room. Observers indicated that items were completed correctly by writing a plus sign next to the item; incorrect or lack of completion of the item was indicated by a negative sign. Correct completion of an item was defined as fully completing the item as listed on the checklist. For example, one checklist item was to have a box of gloves present and at least half full. In order to count as correctly completed, the box must have been at least half full; the mere presence of the box was insufficient. Observers collected data 10–15 min after each session ended. Participants were out of the room at this time and did not see the observers collecting data.

Common human-service performance problems include: poor treatment implementation, inaccurate data collection, inadequate development of program materials, poor attendance/tardiness, failure to report problems to supervisors, and poor graph construction.

A second independent observer collected data along with, but independent of, the primary data collector. Interobserver agreement (IOA) data were obtained by comparing observers' data for each item on the checklist on an item-by-item basis. Point-by-point agreement was calculated by dividing the number of agreements by the total number of checklist items, and converting the ratio to a percentage. Agreement was assessed for at least 40% of sessions (range, 40% to 71%) in eight treatment rooms. Means and ranges for IOA data were as follows: Room A, 96% (range, 78% to 100%); Room B, 97% (range, 82% to 100%); Room C, 96% (range, 81% to 100%); Room D, 96% (range, 81% to 100%); Room E, 95% (range, 75% to 100%); Room F, 93% (range, 78% to 100%); Room G, 93% (range, 80% to 100%); and Room H, 91% (range, 78% to 100%).

Procedure

We first began collecting baseline data on task completion of cleaning duties using the room cleanliness checklist. After baseline data were collected, the third author (a master's-level BCBA) used the PDC-HS to individually interview three supervisors (the respondents) who oversaw all center operations about the problems they were having with treatment room cleanliness. The interviewer also conducted all direct observation components of the PDC-HS. All supervisors were masters-and doctoral-level BCBAs with 3 to 10 years of experience in the field. After we completed the interviews, we reviewed the results, identified two interventions based on the results, and began implementing the interventions. We used a (concurrent) multiple-baseline design across treatment rooms to evaluate intervention effects.

The first intervention consisted of training and posted, graphed feedback. These interventions were based on the results of the PDC-HS, especially the Training and Performance Consequences sections. A second intervention was introduced for two of the rooms (G, H). The second intervention consisted of task clarification and more convenient placement of the materials necessary for task completion. These two intervention components were based on the Task Clarification and Prompting and Resources, Materials, and Processes sections, which were not identified as being problematic based on the results of the PDC-HS. The purpose of the second intervention was to examine the effects of a nonindicated intervention on task completion.

Baseline. During baseline, we evaluated each room using the cleanliness checklist after the participants had completed their treatment session and left. Observers made no contact with participants and no feedback was provided on room cleanliness.

Training and graphed feedback. Based on the results of the PDC-HS, training and graphed feedback were introduced. The experimenter entered before the session and described each item on the checklist to the participant to ensure she understood the tasks she was to complete at the end of the session. The checklist was posted to a wall of the room and available for participants to review during this phase, but participants were not given a copy of the checklist to take with them. In addition, the experimenter informed the participants that graphed data would be posted regularly, and where to find the materials needed to complete the tasks, but the materials were not placed in one salient location in the room. After the training was complete, the experimenter asked the participant not to mention the checklist to anyone else to help preserve the integrity of the multiple-baseline design. After this training, the experimenter had no additional contact with the participants, except when a participant asked a question, to which the experiment replied, “I can't answer that.” Within 5 minutes after each session, the experimenter graphed the data for the room and posted it on a wall next to the checklist. The participants were not in the room when the data were posted. The updated data were available for the participants to view when they entered the room again, which was typically immediately before their next session.

Task clarification and increased availability of materials. Task clarification and increased availability of materials were introduced for rooms G and H. Task clarification consisted of posting the checklist in a salient location in the room (directly in front of them upon entry); however, the experimenter did not speak about the checklist with the participants working in the rooms. In addition, all the materials necessary to complete the tasks on the checklist were placed in a salient location in the room (near the checklist), but no information on what to do with these materials was provided and no feedback on performance was delivered. After the training was complete, the experimenter asked the participant not to mention the checklist to anyone else to ensure independence between rooms. After this training, the experimenter had no additional contact with the participants.

Results

PDC-HS

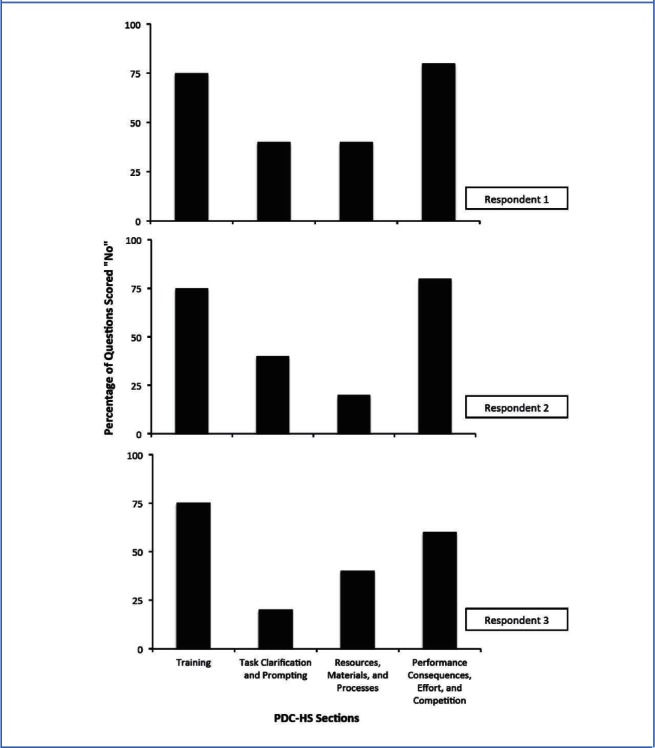

Figure 1 depicts the results of the PDC-HS. The PDC-HS identified a lack of proper training on participant duties and a lack of feedback on performance as potentially being responsible for participant performance problems for all 3 of the BCBA respondents interviewed. For respondents 1 and 2, 75% and 80% of the questions on the Training section and the Consequences, Effort, and Competition section, respectively, suggested a problem. For respondent 3, 75% of the questions on the Training section and 60% of the questions on the Consequences, Effort, and Competition section suggested a problem. For all respondents, the Task Clarification and Prompting and the Resources, Materials, and Processes sections included fewer questions indicating a problem.

Figure 1.

Results from the PDC-HS across BCBA respondents.

Intervention Evaluation

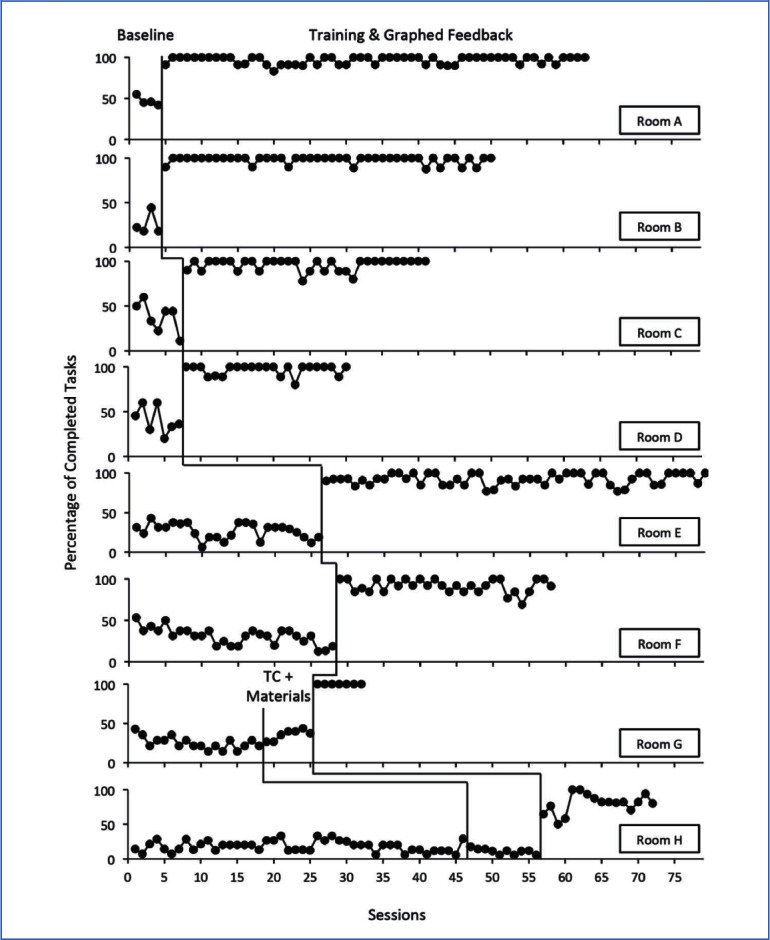

Figure 2 depicts the results of the intervention evaluation. The intervention was first implemented in rooms A and B. The baseline mean for Room A was 47% complete; training and feedback increased performance to a mean of 97% complete. For Room B, the baseline mean was 26% complete. The mean during training and feedback was 98% complete. Next, the intervention was implemented for rooms C and D. For Room C, the baseline mean was 38% complete; training and feedback increased the mean to 96% complete. For Room D, the baseline mean was 41% complete; training and feedback increased the mean to 97% complete. For Room E, the baseline mean was 27% complete. The mean during the training and feedback phase was 92% complete. For Room F, the baseline mean was 31% complete; training and feedback increased the mean to 92% complete. For Room G, the baseline mean was 25% complete. The mean during the task clarification and increased material availability phase was 36% complete. The mean during the training and feedback phase was 100% complete. For Room H, the baseline mean was 18% complete. The mean during task clarification and increased availability of materials was 12% complete. The mean during the training and feedback phase was 80% complete.

Figure 2.

Percentage of completed tasks in each treatment room during the following conditions: baseline, training + graphed feedback, and task clarification + increased availability of materials (TC + Materials).

Discussion

Three BCBAs at a center-based autism treatment facility were interviewed using the PDC-HS to identify the variables contributing to poor cleaning of treatment rooms by therapist employees. The PDC-HS implicated a lack of proper training on participant duties and a lack of performance feedback as contributors to the performance problems. An intervention (training and graphed feedback) targeting these variables was implemented across eight treatment rooms; the intervention increased participant performance in all rooms. In addition, an alternative intervention that included components not identified as being problematic by the PDC-HS (task clarification and increased availability of materials) was also implemented across two of the same rooms. Both implementations of the alterative intervention were ineffective. These data suggest that the PDC-HS streamlined the treatment process by helping to identify relevant factors and disregard irrelevant factors in treatment selection. This strategy of assessing predictive validity—comparing indicated and non-indicated interventions—had not yet been employed in the PDC or OBM literatures, but it is consistent with behavior-analytic research in other areas (e.g., Iwata et al., 1994).

Although social validity was not formally assessed in the current investigation, anecdotal reports from the staff members who participated in both the PDC-HS interviews and the intervention evaluation suggest that they found the PDC-HS and the resulting intervention to be useful. For example, one staff member reported that the PDC-HS would enable her to “quickly and easily assess what needs to be done to help employees to do their job.” Further, the center-based program has continued to use the intervention long after the conclusion of the study.

The results of the present validation study should be evaluated in the context of several considerations. First, we assessed only a limited range of the content of the PDC-HS. Specifically, we assessed interventions designed to address problems with training and feedback. Interventions designed to address identified problems with prompting and the availability of materials were not examined. Systematic replications exploring these other areas would be useful in future research.

Second, it is possible that other nonindicated interventions may have been equally effective to increase performance. We only assessed the efficacy of training, feedback, task clarification, and increased availability of materials. Intervention components unrelated to PDC-HS results, such as goal setting or the presence of a manager, may have been equally effective to increase participant performance. That said, it would have been impractical to assess all nonindicated interventions. Furthermore, the interventions that were evaluated were logically related to the problem (increased availability of materials) or commonly studied in the empirical literature (e.g., task clarification; Austin et al., 2005). Thus, we contend that, although not exhaustive, the present treatment comparison was a fair one.

Third, because the intervention that proved successful was a package of two components (training and feedback), it is impossible to identify their individual contributions to performance improvement. Future studies of interventions indicated by the PDC-HS would be better served by single-intervention components so that the assessment's prediction can be better evaluated.

Fourth, unlike some prior training applications, participants were not given a written description of the tasks in the training and graphed feedback condition (although a checklist was posted in the room). It is possible that this treatment package would have been even more effective if participants had physical possession of the checklist. However, in an effort to maintain the functional independence of our multiple baselines, the decision was made to omit this step during training.

Fifth, IOA on the administration of the PDC-HS was not assessed. It is possible that the involvement of other interviewers or informants would have yielded different results. Future research on the reliability of the administration of the PDC-HS would be an important contribution to this line of research.

Finally, the indirect nature of the PDC-HS is an inherent limitation. As mentioned previously, many performance problems are behavioral deficits, not behavioral excesses. Behavioral deficits are not particularly well suited for direct-observation assessment such as descriptive assessment or functional analysis. Thus, until this barrier is eliminated, indirect assessment such as the PDC-HS may prove useful.

As with the development of any new assessment tool, there are a number of opportunities for additional research. Among the most pressing research needs are systematic replications of the PDC-HS with different classes of human-service staff members from different care settings. In the present study, all of the staff members were young, college educated, and committed to careers in behavior analysis. This sample is, admittedly, not representative of many human-service staff populations for whom the PDC-HS may be differentially useful. Systematic replications with other performance problems would also be valuable. Common problems such as tardiness and absenteeism, procedural integrity failures, and unsafe behavior might be impacted by different environmental factors. Thus, studies of different performance problems might also be opportunities to evaluate a fuller range of variables on the PDC-HS. An analysis of PDC-HS outcomes for a large staff sample in a proscribed area (e.g., 50 direct-care staff members serving adult consumers) would also be important. Such an “epidemiological” analysis would enable one to identify common performance problems and the proportion of different environmental determinants that might lead to the development of improved default training and management procedures. This approach has been successful with client problem behavior (e.g., Iwata et al., 1994) and might be similarly useful in organizational settings. In addition, as we modified the PDC for human-service settings, the instrument could be further modified for other purposes (e.g., skill deficits in aging populations). Finally, as a further test of the utility of the PDC-HS, researchers could compare the effects of staff-management interventions between behavior analysts who do or do not use the assessment. It is possible that practicing behavior analysts already ask the appropriate questions when diagnosing staff performance problems and intervene accordingly. Although this has not been our observation, the premise is certainly testable.

In conclusion, the present article contributes to the performance management literature by introducing the PDC-HS, an assessment that can be used to examine the variables that contribute to staff performance problems in human-service settings. Given the proliferation of human-service environments and the ongoing staff management challenges in those environments, the PDC-HS should be useful, if not in always identifying effective interventions, then by getting practicing behavior analysts to attend to a wider array of factors that can affect supervisee performance and rely less on common default interventions such as retraining. The present study also extends the literature on the PDC by demonstrating a method for assessing predictive validity, a strategy that should be employed to assess newly developed functional assessment procedures.

Appendix A

Treatment room cleanliness checklist.

Safety and Sanitation

- Counter/Cabinet

- ○Is at least one hand sanitizer pump, one box of gloves in each size (S,M,L), and one opened container of Clorox Wipes present, and on the counter?

- ○Is at least one full backup pump of hand sanitizer present, and in the cabinet above the sink?

- ○Is at least one full backup box of each glove size (S,M,L) present, and in the cabinet above the sink?

- ○Is at least one unopened backup container of Clorox Wipes present, and in the cabinet above the sink?

- ○Is a fully stocked first aid kit in the cabinet? (includes Band-Aids, alcohol wipes, and gauze)

- Panic Button

- ○Is the panic button present, and does it match the room number written on the back of it?

- ○Are the alarms working?

Room Organization

Are only essential materials on the counter tops (i.e., hand sanitizer, gloves, tissues, Clorox Wipes), otherwise countertops are clear?

Is the CD player present and on top of the shelf below the whiteboard that holds Legos?

Are the tables in the correct place? (1 U-shaped table in front of sink, straight edge parallel to counter)

Are all chairs tucked under the tables?

Are the easels (2) set up between the early learner classrooms, with drawing surfaces facing each classroom?

Are art supplies cleaned up? (i.e., easels cleaned off, paintbrushes washed, containers closed, and supplies put away in the cabinet above the sink)

Are toys in appropriately labeled bin, or in appropriate place if there is no labeled bin? (e.g., a ball is not found in the tub labeled cars, puzzles are neatly stacked on the shelf or placed in stacker)

Are bins and large toys neatly along the wall or on a shelf?

Are books placed upright on bookshelf in an organized manner?

Are cabinet doors and drawers closed?

Floors and Tables

Is trash thrown away? (i.e., not on floor or table tops)

Appendix B

Footnotes

We thank Ivy Chong and Alison Betz for their assistance in arranging data collection. The content of this article does not reflect an official position of the Behavior Analyst Certification Board.

References

- Austin J. Performance analysis and performance diagnostics. In: Austin J., Carr J. E., editors. Handbook of applied behavior analysis. Reno, NV: Context Press; 2000. pp. 321–349. (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Austin J., Carr J. E., Agnew J. L. The need for assessment of maintaining variables in OBM. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 1999;19(2):59–87. [Google Scholar]

- Austin J., Weatherly N. L., Gravina N. E. Using task clarification, graphic feedback, and verbal feedback to increase closing-task completion in a privately owned restaurant. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2005;38:117–120. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.159-03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgio L. D., Engel B. T., Hawkins A., McCormick K., Scheve A., Jones L. T. A staff management system for maintaining improvements in continence with elderly nursing home residents. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1990;23:111–118. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1990.23-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels A. C. Performance management. Tucker, GA: Performance Management Publications; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Eikenhout N., Austin J. Using goals, feedback, reinforcement, and a performance matrix to improve customer service in a large department store. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 2005;24(3):27–64. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert T. F. Human competence. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hanley G. P., Iwata B. A., McCord B. E. Functional analysis of problem behavior: A review. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2003;36:147–185. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata B. A., Pace G. M., Cowdery G. E., Miltenberger R. G. What makes extinction work: An analysis of procedural form and function. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:131–144. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mager R. F., Pipe P. Analyzing performance problems. Belmont, CA: Fearon Publishers; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan T., Jarema K., Austin J. An objective review of Journal of Organizational Behavior Management: 1986–1997. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 1999;19(3):83–115. [Google Scholar]

- Pampino R. N., Heering P. W., Wilder D. A., Barton C. G., Burson L. M. The use of the Performance Diagnostic Checklist to guide intervention selection in an independently owned coffee shop. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 2003;23(2–3):5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Reid D. H., Parsons M. B. Organizational behavior management in human service settings. In: Austin J., Carr J. E., editors. Handbook of applied behavior analysis. Reno, NV: Context Press; 2000. pp. 274–294. (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez M., Wilder D. A., Therrien K., Wine B., Miranti R., Daratany K., Salume G., Baranovsky G., Rodriguez M. Use of the Performance Diagnostic Checklist to select an intervention designed to increase the offering of promotional stamps at two sites of a restaurant franchise. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 2005;25(3):17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Arco L. Feedback for improving staff training and performance in behavioral treatment programs. Behavioral Interventions. 2008;23:39–64. [Google Scholar]

- Bacon D. L., Fulton B. J., Malott R. W. Improving staff performance through the use of task checklists. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 1982;4(3/4):17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes C. S., Dunning J. L., Rehfeldt R. A. An evaluation of strategies for training staff to implement the picture exchange communication system. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2011;5:1574–1583. [Google Scholar]

- Brackett L., Reid D. H., Green C. W. Effects of reactivity to observations on staff performance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2007;40:191–195. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.112-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casella S. E., Wilder D. A., Neidert P., Rey C., Compton ML., Chong I. The effects of response effort on safe performance by therapists at an autism treatment facility. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2010;43:729–734. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2010.43-729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham T. R., Austin J. Goal setting, task clarification, and feedback to increase the use of the hands-free technique by hospital operating room staff. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2007;40:673–677. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.673-677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener L. H., McGee H. M., Miguel C. F. An integrated approach for conducting a behavioral systems analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 2009;29:108–135. [Google Scholar]

- Gatewood R. D., Feild H. S., Barrick M. Human resource selection. 6th ed. Independence, KY: Cengage Learning; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gravina N., VanWagner M., Austin J. Increasing physical therapy equipment preparation behaviors using task clarification, graphic feedback and modification of work environment. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 2008;28:110–122. [Google Scholar]

- Green C. W., Rollyson J. H., Passante S. C., Reid D, H. Maintaining proficient supervisor performance with direct support personnel: An analysis of two management approaches. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2002;35:205–208. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2002.35-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green C., Reid D., Passante S., Canipe V. Changing less-preferred duties to more-preferred: A potential strategy for improving supervisor work enjoyment. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 2008;28:90–109. [Google Scholar]

- May R. J., Austin J. L., Dymond S. Effects of a stimulus prompt display on therapists' accuracy, rate, and variation of trial type delivery during discrete trial teaching. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2011;5:305–316. [Google Scholar]

- McGee H. M., Diener L. H. Behavioral systems analysis in health and human services. Behavior Modification. 2010;34:415–442. doi: 10.1177/0145445510383527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Methot L., Williams L., Cummings A., Bradshaw B. Effects of a supervisory performance feedback meeting format on subsequent supervisor-staff and staff-client interactions in a sheltered workshop and a residential group home. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 1996;16(2):3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Mozingo D. B., Smith T., Riordan M. R., Reiss M. L., Bailey J. S. Enhancing frequency recording by developmental disabilities treatment staff. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2006;39:253–256. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2006.55-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabeyama R., Sturmey P. Using self-recording, feedback, modeling, and behavioral rehearsal for safe and correct staff guarding and ambulation distance of students with multiple physical disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2010;43:341–345. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2010.43-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petscher E. S., Bailey J. S. Effects of training, prompting, and self-monitoring on staff behavior in a classroom for students with disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2006;39:215–226. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2006.02-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strouse M. C., Carroll-Hernandez T. A., Sherman J. A., Sheldon J. B. Turning over turnover: The evaluation of a staff scheduling system in a community-based program for adults with developmental disabilities. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 2003;23:45–63. [Google Scholar]