Abstract

The present article summarizes the results from the Active Healthy Kids Canada 2012 Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth. The Report Card assessed the physical activity levels of Canadian children and youth nationally, and the initiatives of public and nongovernment sectors to promote and facilitate physical activity opportunities for children and youth in Canada. Based on a comprehensive collection of data that were analyzed and/or published in 2011, 24 indicators relating to physical activity were graded. The Physical Activity Levels indicator, the core indicator of the Report Card, was graded an ‘F’ for the sixth consecutive year. Although the majority of grades remained unchanged from the previous year, four grades improved and two worsened. These results suggest that few Canadian children and youth have sufficient physical activity levels, and that greater efforts are required across sectors to promote and facilitate physical activity opportunities for children and youth in Canada.

Keywords: Child advocacy, Child welfare, Health communication, Motor activity, Policy

Abstract

Le présent article résume les résultats du bulletin de l’activité physique 2012 des enfants et des jeunes de Jeunes en forme Canada. Le bulletin évaluait le taux d’activité physique des enfants et des adolescents canadiens sur la scène nationale, de même que les initiatives des secteurs publics et non gouvernementaux pour promouvoir et favoriser les occasions d’activité physique chez les enfants et les adolescents du Canada. D’après une collecte complète des données analysées ou publiées en 2011, on a classé 24 indicateurs liés à l’activité physique. L’indicateur lié au niveau d’activité physique, le principal indicateur du bulletin, a obtenu une note de « F » pour la sixième année consécutive. Même si la majorité des notes n’a pas changé par rapport à l’année précédente, quatre se sont améliorées et deux ont empiré. Selon ces résultats, peu d’enfants et d’adolescents canadiens ont un niveau d’activité physique suffisant, et il faudra consentir plus d’efforts entre les secteurs pour promouvoir et favoriser les occasions d’activité physique pour les enfants et les adolescents du Canada.

Despite growing evidence of the health benefits of physical activity in the pediatric population (1), the proportion of Canadian children and youth who meet the Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines for Children and Youth remains alarmingly low (2), while the average time spent watching television, playing video games and/or playing on the computer appears to be on the rise (3). The inadequate levels of physical activity among Canadian children and youth may signal the need for more knowledge exchange between physical activity researchers and decision makers to develop effective physical activity promotion strategies for children and youth.

The Active Healthy Kids Canada 2012 Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth (2012 Report Card) was developed and released by Active Healthy Kids Canada, a national not-for-profit organization, and seeks to facilitate the knowledge-to-action process by providing an annual assessment of the physical activity levels of Canadian children and youth, and the initiatives of public and nongovernment sectors to promote and facilitate physical activity opportunities for children and youth in Canada (4). The Report Card and the annual communication strategy that highlight the findings of the Report Card are used as a key advocacy tool to inform both the public and decision makers about the physical inactivity crisis, thus creating an agenda for action.

The purpose of the present article is to summarize the results of the 2012 Report Card, which represents a comprehensive review of the academic and nonacademic literature analyzed and/or published in 2011 that relates to the physical activity levels and opportunities of Canadian children and youth.

METHODS

The development of the 2012 Report Card relied on strategic partnerships from four key partners with varying roles and skill sets: Active Healthy Kids Canada (www.activehealthykids.ca) funded, oversaw and managed the project and orchestrated the dissemination of the Report Card; the Healthy Active Living and Obesity Research Group at the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute (www.haloresearch.ca) conducted the comprehensive review of academic and nonacademic literature, led the content development and review process, and was responsible for writing the long-form version of the 2012 Report Card; the Research Work Group consisted of 11 content experts from across Canada (invited by the Chief Executive Officer of Active Healthy Kids Canada on the recommendation of the Chief Scientific Officer and Scientific Officer; the criteria for recommendation were expertise in one or more knowledge areas of the Report Card, and geographical and sector representation) and was responsible for contributing data, reviewing content and informing the grade assignment process; and ParticipACTION (www.participaction.com) contributed expertise relating to the development of a cover story, cover image and an effective media and public relations strategy.

Twenty-four indicators relating to physical activity in Canadian children and youth were organized into six indicator categories (Physical Activity; Sedentary Behaviour; School & Childcare Settings; Family & Peers; Community & the Built Environment; and Policy) for the 2012 Report Card, which relied on several sources of data including the 2007–2009 Canadian Health Measures Survey (CHMS) from Statistics Canada (5), the 2009–2010 Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children survey (HBSC) from the Public Health Agency of Canada and the World Health Organization (6), the 2009–2011 Canadian Physical Activity Levels Among Youth survey (CANPLAY) from the Canadian Fitness and Lifestyle Research Institute (CFLRI) (7), the 2010 Physical Activity Monitor from CFLRI (8) and the 2011 Opportunities for Physical Activity at School Survey (OPASS) from CFLRI. The majority of these data sources were analyzed and/or published in 2011.

Following the data gathering and synthesis process, the Research Work Group convened to evaluate the aggregated evidence and assign grades for each indicator. Key considerations included the quality of the compiled evidence, trends over time, international comparisons and the presence of disparities (eg, sex differences, children with disabilities, geographical differences, socioeconomic differences). Each indicator was discussed until consensus was reached using a letter-based grading scheme based on the proportion of children and youth meeting a defined benchmark or optimal scenario: A, 80% to 100%; B, 60% to 79%; C, 40% to 59%; D, 20% to 39%; F, 0% to 19%; and INC, incomplete data. The grading scheme also incorporated a plus-minus system depending on whether the proportion of children and youth meeting the defined benchmark or optimal scenario was at the upper (+) or lower (–) limit of the letter grade. A more comprehensive description of the methodology is available elsewhere (9).

RESULTS

The 2012 Report Card is the eighth consecutive annual assessment of physical activity in Canadian children and youth nationally, and the initiatives of public and nongovernment sectors to promote and facilitate physical activity opportunities for children and youth in Canada.

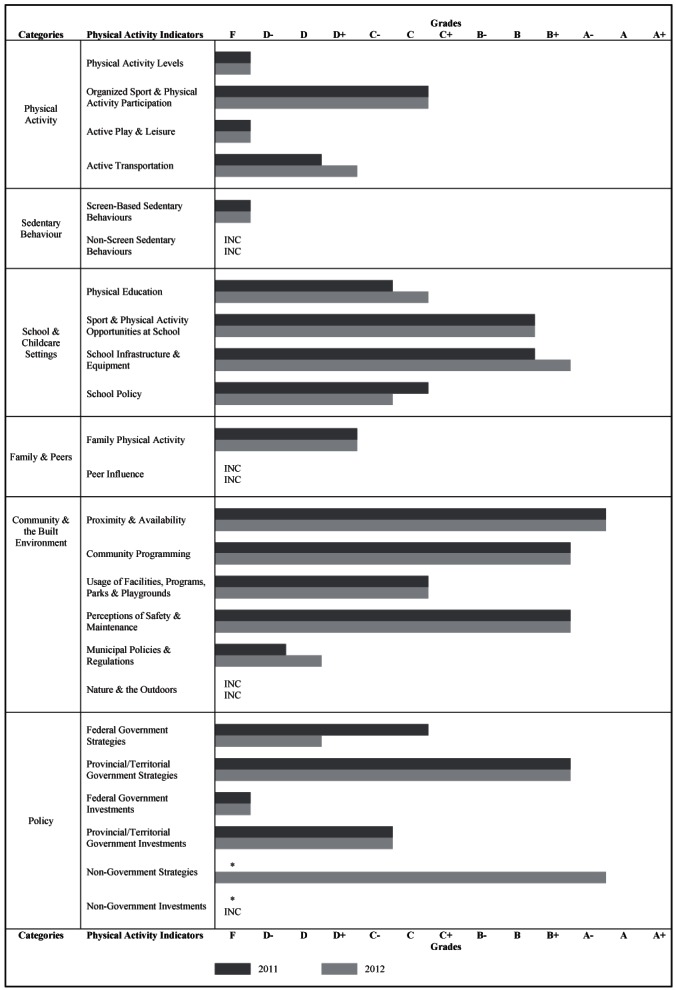

Figure 1 summarizes the grades given to each indicator in the 2012 Report Card and compares the grades to those given in the 2011 Report Card. Although the majority of grades remain unchanged since the 2011 Report Card (10,11), grades improved on four indicators and worsened on two indicators, and one indicator was split into two more focused indicators.

Figure 1).

Grades according to physical activity indicator in the Active Healthy Kids Canada Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth, 2011–2012. The grade for each indicator is based on the proportion of children and youth meeting a defined benchmark or optimal scenario: A, 80% to 100%; B, 60% to 79%; C, 40% to 59%; D, 20% to 39%; F, 0% to 19%. *These indicators comprised the Non-Government Strategies & Investments indicator in the 2011 Report Card, which was graded a ‘C’. INC Incomplete data

The Physical Activity Levels indicator was graded an ‘F’. This is the core grade of the Report Card because it assesses the overall physical activity of Canadian children and youth. The grade was informed by the most currently available, nationally representative, accelerometer-sampled data (2007–2009 CHMS), which reveal that only a small proportion of children and youth (7%) engaged in at least 60 min of moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity (MVPA) on a daily basis (2) as recommended by the Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines for Children and Youth (12,13). More recent pedometer-sampled data from the 2009–2011 CANPLAY survey, an annual national survey of approximately 10,000 children and youth, reveal similar findings: only 15% of Canadian children and youth took 12,000 steps or more on at least six of the seven days the pedometer was worn (14), which is currently the most accurate target for assessing adherence to the Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines for Children and Youth (15).

DISCUSSION

Physical Activity

The Physical Activity Levels indicator was graded an ‘F’ for the sixth consecutive year and has not undergone a grade change since 2006. The sole grade change in the Physical Activity category of indicators occurred within Active Transportation, which improved from a ‘D’ in the 2011 Report Card to a ‘D+’ in the 2012 Report Card. This grade was informed by new data from the 2009–2010 HBSC, which found that 35% of Canadian youth reported the use of active modes of transportation (eg, walking, cycling) on the main part of their trip to school. This proportion was higher than had been reported in previous data sets used to inform this grade.

Sedentary Behaviour

Although there were no grade changes in the Sedentary Behaviour category of indicators, new data continue to highlight the alarmingly high levels of screen-based sedentary behaviours in Canadian youth. In a nationally representative sample of students in grades six through 12, the average daily time spent watching television, playing video games and/or playing on the computer was 7.8 h (3). In addition, only 19% of children and youth in the 2009–2010 HBSC reported meeting the Canadian Sedentary Behavior Guidelines, which recommend no more than 2 h of recreational screen time per day (16).

School & Childcare Settings

Of the four indicators in the School & Childcare Settings category, all but one (Sport & Physical Activity Opportunities at School) underwent grade changes between 2011 and 2012.

The Physical Education grade improved slightly from a ‘C−’ (2011) to a ‘C’ (2012) based on new data from the 2011 OPASS in which a majority of schools from across Canada (67%) reported offering students physical education (PE) classes that were led by PE specialists. The proportion of students who received the recommended quantity of PE per week (150 min) reportedly ranged from 15% to 65%, varying according to school grade. Compared with the 2006 OPASS, there were statistically significant increases across select grades (≤ grade 6) in the proportion of schools reporting the achievement of 150 min of PE per week in 2011.

The School Infrastructure & Equipment indicator improved slightly from a ‘B’ (2011) to a ‘B+’ (2012). The grade was informed by new data from the 2009–2010 HBSC survey in which a high proportion of schools (>80%) reported their students having regular access to gymnasiums and outdoor facilities both in and outside of school hours.

The grade for the School Policy fell from a ‘B’ (2011) to a ‘C−’ (2012) due to new data from the 2009–2010 HBSC, which revealed that only one-half of schools in Canada reported the presence of committee-led physical activity policies and improvement plans related to physical activity for the current school year.

Community & the Built Environment

Municipal Policies & Regulations was the sole indicator in the Community & Built Environment category to undergo a slight grade change from a ‘D−’ (2011) to a ‘D’ (2012) due to data from the 2009 Survey of Physical Activity in Canadian Communities in which slightly less than one-half of Canadian municipalities rated opportunities for physical activity and sport as high priorities for promotion. However, data from the same survey revealed an encouraging proportion of Canadian municipalities having prioritized various forms of infrastructure and services that support physical activity participation. Between 2000 and 2009, for example, there have been substantial percentage increases in the proportion of municipalities reporting the presence of multi-use trails (36%), designated bicycle lanes on roads (36%), and/or bicycle carriers and ski racks on public transport (172%) (17).

Policy

The grade for Federal Government Strategies fell from a ‘C’ (2011) to a ‘D’ due to persistent indications that Canada is falling behind peer nations in the promotion of physical activity at the population level (eg, continued absence of a national physical activity strategy).

In the 2012 Report Card, the Non-Government Strategies & Investment indicator was split into two more focused indicators: Non-Government Strategies and Non-Government Investments. Non-Government Strategies was graded an ‘A−’ due to the physical activity promotion initiatives of the nongovernment sector with its unilateral development of a national physical activity strategy, Active Canada 20/20, and the development and publication of the Canadian Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines for the Early Years (0–4 Years) (18,19). Non-Government Investments was graded as ‘INC’ (incomplete) due to a lack of data.

Report Card cover story: Active play

In the 2012 Report Card, active play and the question of whether it is in decline was the focus of the cover story. Active play, which is generally understood as freely chosen, spontaneous and self-directed physical activity involving an element of fun (20,21), may be an important contributor to the overall physical activity of children and youth. However, several recent data sources suggest that active play may be in decline. According to the 2010 Physical Activity Monitor, the proportion of Canadian children and youth who play outside after school (approximately 15:00 to 18:00) dropped 14% in the past decade (22). According to the 2007–2009 CHMS, approximately half (46%) of children and youth achieved ≥3 h of active play per week, including weekends (23). The same survey also revealed that children and youth spent only 10% (24 min) of their discretionary time at lunch and after school in MVPA.

Limitations

Although the 2012 Report Card represents a comprehensive review of the academic and nonacademic literature analyzed and/or published in 2011, the data may not provide a complete assessment of the physical activity indicator(s) being informed by the data. For example, data regarding the existence of physical activity policies do not necessarily reveal the implementation status or effectiveness of the policies. Therefore, it is important to note that while the Report Card grades are based on the best available data, more data may be needed. Indeed, the long-form version of the Report Card draws attention to research gaps for each physical activity indicator.

There is also a need to leverage resources to evaluate the report card process and communication strategy. Preliminary media coverage data provide evidence of significant impact and reach by the communication strategy (cover story around active play). Media attention can be measured by tallying media hits and impressions. As explained elsewhere (9), “[t]he number of media impressions involved for each media hit considers the media outlet, coverage time and placement, region, the reporter, and the key message reported. Media impressions are calculated by multiplying circulation and readers per copy or straight broadcast reach by program.” Overall, media attention associated with the 2012 Report Card was high, with a large number of total media hits (>500) and impressions (>142 million), which suggests the Report Card may be a viable and promising tool for affecting change in policy and program development related to physical activity; however, more evaluation is needed.

CONCLUSION

Despite low levels of physical activity among Canadian children and youth and high levels of screen time, little improvement has been observed in physical activity promotion in the past year. Greater investment and priority are required from public and non-government sectors to promote and facilitate physical activity opportunities for children and youth in Canada.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following members of the Research Work Group for their contributions to the 2012 Report Card: Mike Arthur, Christine Cameron, Jean-Philippe Chaput, Jennifer Cowie Bonne, Guy Faulkner, Ian Janssen, Stephen Manske, Jonathan McGavock, John Spence, Angela Thompson and Brian Timmons. The authors also thank the following researchers from the Healthy Active Living and Obesity Research Group at the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute for their contributions to the 2012 Report Card: Charles Boyer, Zach Ferraro, Kimberly Grattan, Anne Marie Hospod and Richard Larouche. The production of the 2012 Report Card was made possible by The Lawson Foundation, Provincial/Territorial Governments through the Interprovincial Sport and Recreation Council, The Heart & Stroke Foundation, George Weston Ltd and Kellogg’s.

Footnotes

INSTITUTION WHERE WORK ORIGINATED: Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute, Ottawa, Ontario.

REFERENCES

- 1.Janssen I, Leblanc AG. Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:40. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-7-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colley RC, Garriguet G, Janssen I, Craig CL, Clarke J, Tremblay MS. Physical activity of Canadian children and youth: Accelerometer results from the 2007 to 2009 Canadian Health Measures Survey. Health Rep. 2011;22:15–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leatherdale ST, Ahmed R. Screen-based sedentary behaviours among a nationally representative sample of youth: Are Canadian kids couch potatoes? Chronic Dis Inj Can. 2011;31:141–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Active Healthy Kids Canada. Is active play extinct? The Active Healthy Kids Canada 2012 Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth. 2012. < dvqdas9jty7g6.cloudfront.net/reportcards2012/AHKC%202012%20-%20Report%20Card%20Long%20Form%20-%20FINAL.pdf> (Accessed March 25, 2013)

- 5.Statistics Canada. Canadian Health Measures Survey. 2012. < www.statcan.gc.ca/survey-enquete/household-menages/5071-eng.htm> (Accessed March 25, 2013) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Public Health Agency of Canada. Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children. 2012. < www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/hp-ps/dca-dea/prog-ini/school-scolaire/behaviour-comportements/index-eng.php> (Accessed March 25, 2013)

- 7.Canadian Fitness and Lifestyle Research Institute. CANPLAY. 2012 < www.cflri.ca/node/57> (Accessed March 25, 2013) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Canadian Fitness and Lifestyle Research Institute. Physical Activity Monitor, 2012. 2010. < www.cflri.ca/pub_page/105> Accessed March 25, 2013)

- 9.Colley RC, Brownrigg M, Tremblay MS. A model of knowledge translation in health: The Active Healthy Kids Canada Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth. Health Promot Pract. 2012;13:320–30. doi: 10.1177/1524839911432929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Active Healthy Kids Canada. Don’t Let This Be the Most Physical Activity Our Kids Get After School. The Active Healthy Kids Canada 2011 Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth. 2011. < dvqdas9jty7g6.cloudfront.net/reportcard2011/ahkcreportcard20110429final.pdf> (Accessed March 25, 2013)

- 11.Barnes JD, Colley RC, Tremblay MS. Results from the Active Healthy Kids Canada Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2012;37:793–7. doi: 10.1139/h2012-033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines for Children 5–11 Years, 2011. < www.csep.ca/CMFiles/Guidelines/CSEP-InfoSheets-child-ENG.pdf> (Accessed March 25, 2013)

- 13.The Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines for Youth 12–17 Years. 2011. < www.csep.ca/CMFiles/Guidelines/CSEP-InfoSheets-youth-ENG.pdf> (Accessed March 25, 2013)

- 14.Canadian Fitness and Lifestyle Research Institute. Bulletin 02: Physical activity levels of Canadian children and youth including provincial bulletins. 2012. < www.cflri.ca/node/972> (Accessed March 25, 2013)

- 15.Colley RC, Janssen I, Tremblay MS. Daily step target to measure adherence to physical activity guidelines in children. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44:977–82. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31823f23b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tremblay MS, Leblanc AG, Janssen I, et al. Canadian sedentary behaviour guidelines for school-aged children and youth. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2011;36:59–64. doi: 10.1139/H11-012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Canadian Fitness and Lifestyle Research Institute. 2009 Capacity Study. 2010. < 72.10.49.94/pub_page/129> (Accessed March 25, 2013)

- 18.Tremblay MS, Leblanc AG, Carson V, et al. Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines for the Early Years (aged 0–4 years) Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2012;37:345–56. doi: 10.1139/h2012-018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tremblay MS, Leblanc AG, Carson V, et al. Canadian Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines for the Early Years (aged 0–4 years) Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2012;37:370–80. doi: 10.1139/h2012-019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bergen D. Play as the learning medium for future scientists, mathematicians, and engineers. Amer J Play. 2009;1:413–28. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brockman R, Fox KR, Jago R. What is the meaning and nature of active play for today’s children in the UK? Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:15. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Canadian Fitness and Lifestyle Research Institute. Bulletin 04: Children’s active pursuits during the after school period. 2011. < www.cflri.ca/node/922> (Accessed March 25, 2013)

- 23.Garriguet D, Colley RC. Daily patterns of physical activity participation in Canadians. Health Rep. 2012;23:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]