Abstract

Binge eating is prevalent among weight loss treatment-seeking youth. However, there are limited data on the relationship between binge eating and weight in racial or ethnically diverse youth. We therefore examined 409 obese (BMI ≥ 95th percentile for age and sex) treatment-seeking Hispanic (29.1%), Caucasian (31.7%), and African American (39.2%), boys and girls (6-18y). Weight, height, waist circumference, and body fat were measured to assess body composition. Depressive symptoms were measured with the Children’s Depressive Inventory and disordered eating cognitions were measured with the Children’s Eating Attitudes Test. Accounting for age, sex, body fat mass, and height, the odds of parents reporting that their child engaged in binge eating were significantly higher among Caucasian compared to African American youth, with Hispanic youth falling non-significantly between these two groups. Youth with binge eating had greater body adiposity (p = .02), waist circumference (p = .02), depressive symptoms (p = .01), and disordered eating attitudes (p = .04), with no difference between racial or ethnic group. We conclude that, regardless of race or ethnicity, binge eating is prevalent among weight loss treatment-seeking youth and is associated with adiposity and psychological distress. Further research is required to elucidate the extent to which binge eating among racially and ethnically diverse youth differentially impacts weight loss outcome.

Keywords: binge eating, youth, ethnicity, race, obesity

1. Introduction

Pediatric obesity has more than tripled in prevalence over the past several decades,1 with disproportionately higher rates among racial and ethnic minorities across all age strata.2 Binge eating, defined as the consumption of an objectively large amount of food while experiencing a sense of loss of control over eating,3 is the most commonly reported disordered eating behavior among obese children.4 While full-syndrome binge eating disorder (BED), defined as recurrent episodes of binge eating with associated distress, is rare in youth, infrequent binge eating (one episode per month to one in 6 months) is prevalent, ranging from 20-37% among obese weight-loss treatment seeking samples.4

Pediatric binge eating appears to promote excessive weight and fat gain in non-treatment samples5,6 and may complicate weight-loss treatment. Although some data show no impact of binge eating on pediatric weight loss,7,8 others suggest that binge eating may inhibit success in losing weight.9

Binge eating is associated with disordered eating attitudes and general psychopathology, such as symptoms of depression, anxiety, and parent-reported problems across pediatric samples.4 Of great concern are prospective data showing that early binge eating is associated with adverse psychological outcomes and eating disorders.10,11

Preliminary data suggest that the prevalence of pediatric binge eating may differ by racial or ethnic category. More specifically, survey studies indicate that Hispanic youth report the experience of binge eating to at least the same extent as Caucasian youth, with prevalence rates ranging from 19-34% .12-14 Among African American youth, binge eating prevalence ranges from 12-23% . Studies comparing African American to Caucasian youth are mixed, with most,12-14 but not all15 studies evidencing lower binge eating prevalence among African American youth.

However, to date no study has systematically examined binge eating behaviors among a diverse sample of obese weight-loss treatment seeking youth. Further, our understanding of how race/ethnicity plays a role in the relationship between binge eating and weight and psychological variables is limited. We therefore sought to examine the prevalence of parent reported binge eating across a diverse sample of obese treatment-seeking youth and to determine if binge eating was differentially associated with body composition and psychosocial variables based upon race/ethnicity. We hypothesized that, among this treatment-seeking sample of obese youth, binge eating would be equally prevalent and show a similar relationship to body size and psychosocial variables across all racial/ethnic groups.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Participants

Study participants were a convenience sample of obese youth pooled from data collected at the baseline assessment of three weight-loss treatment studies. The first sample included participants from a community-based obesity intervention program at Children’s National Medical Center (CNMC). Participants for this study were recruited through flyers posted at community facilities such as clinics, schools, and churches, advertising a study for weight-loss treatment. CNMC participants were included if they were of Hispanic ethnicity, between 7-15 years of age, and had a BMI ≥ 95th percentile for age and sex. CNMC participants were excluded if they had a medically-related health co-morbidity or clinically significant depression.

The second and third samples included participants from placebo-controlled medication trials conducted at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). Participants for these studies were recruited via sending letters advertising a weight-loss study to appropriate-aged children in local school systems, by advertisements in local newspapers, and by referral from physicians who see obese children. The second sample included obese non-Hispanic African American (58.8%) and non-Hispanic Caucasian (41.2%) adolescents (12-17 years) with at least one weight-related health co-morbidity, such as Type 2 diabetes or systolic or diastolic hypertension. The third sample included obese youth (6-12 years) of any race or ethnicity with insulin resistance, defined as fasting insulin concentration ≥ 15 mIU/mL. Fasting insulin was measured during the baseline assessment at an NICHD laboratory. Youth from this sample were 39.0% African American, 48.8% Caucasian, and 12.2% Hispanic. A detailed description of inclusion and exclusion criteria for the latter two studies has been published previously.16,17 By nature of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, youth from the second and third samples (NICHD) were significantly more obese than youth from the first sample (CNMC).

2.2 Procedure

All three studies were approved by their respective Institutional Review Boards and written consent and assent were obtained from parents and children. For the study at CNMC, data were collected at the clinical research center in Washington, DC. For the NICHD studies, data were collected at the NIH clinical center in Bethesda, MD. Data were collected at a baseline assessment, prior to weight-loss treatment initiation.

2.3 Measures

Binge eating was assessed by parent report on the adolescent version of the Questionnaire on Eating and Weight Patterns (QEWP-P).18 The QEWP-P parent report was adapted from the adult version19 and is designed to diagnose DSM-IV-TR defined eating disorders.3 The QEWP-P parent-report assesses presence and frequency of binge eating during the past six months by assessing the consumption of an objectively large amount of food accompanied by the experience of loss of control over eating. The adolescent version of the measure shows good test-re-test reliability20 and adequate concurrent validity based on disordered eating attitudes and depressive symptoms.18 As the parent version of the QEWP was administered by all three studies, we used parent, rather than child report of binge eating, to keep the assessment of binge eating consistent across all three samples. Assessment of children’s eating behaviors via parent report is widely used and is considered a reliable method.21 While research indicates that parent and child report of eating behaviors differ among non-treatment seeking youth,22 there is evidence to suggest greater concordance between parent and child report of children’s eating behaviors when examining overweight youth seeking weight-loss treatment.23 Parent report of eating behaviors may be particularly advantageous with young children, who may have less insight regarding their eating behaviors.23 Consistent with published studies,5,17 binge eating was categorized as presence (≥1 episodes in the 6 months prior to assessment) or absence (no episodes in the past 6 months).

Youth completed self-assessment questionnaires of disordered eating attitudes and depressive symptoms. The children’s version of the Eating Attitudes Test (ChEAT)24 is a 26-item self-report questionnaire that assesses a variety of disordered eating cognitions and behaviors, such as dieting, purging, and preoccupation over food. The ChEAT has adequate reliability and validity and has been employed with a variety of races and ethnicities, including African American and Hispanic youth.25 Of note, the ChEAT was not administered to youth from the third sample (primarily African American and Caucasian youth ages 6-12y). The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI)26 is a 27-item self-report questionnaire designed to assess depressive symptoms in children and adolescents. The CDI generates a total score comprised of five subscale scores (negative mood, interpersonal problems, ineffectiveness, anhedonia, and negative self-esteem). Only the total score was examined in this study. The CDI has good psychometric properties.26

BMI was calculated based on weight as measured with a digital scale and height by stadiometer. Waist circumference (cm) was also measured. BMI and waist circumference were standardized to z-scores using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 200027 and the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III)28 values, respectively. Body fat mass was measured with air displacement plethysmography (BodPod).

2.4 Data Analysis

Data were examined to determine that all variables were normally distributed.29 Outliers were adjusted to fall 1.5 times the interquartile range below the 25th percentile or above the 75th percentile (i.e., to the whiskers in Tukey’s boxplot30). All scores had acceptable levels of skew and kurtosis. Analyses were conducted with PASW version 18 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Logistic regression was used to examine the odds of binge eating and binge eating disorder (presence vs. absence) across racial/ethnic categories, adjusting for age, sex, body fat mass, and height. Subsequent analyses employed either a Univariate (ANOVA) or Multivariate Analysis of Covariance (MANCOVA) to examine group differences on demographic variables and measures of body composition and psychosocial variables. All analyses of body composition were adjusted for age and sex. The analysis for body fat mass was further adjusted for height. Psychological variables were also adjusted for age, sex, race, and BMI z-score.

3.0 Results

3.1 Sample Characteristics

Data were collected from 409 youth (age M ± SD, 12.9 ± 2.4 y, 60% female). By design, the sample was obese (BMI z-score 2.5 ± .3) and included 29.1% Hispanic, 31.7% Caucasian, and 39.2% African American youth. Demographics are presented in Table 1. On average, the Hispanic sample was younger (all ps < .001) and comprised of fewer females than the African American and Caucasian samples (p = .02). Caucasian youth were also younger than African American youth (p = .02). African American youth had significantly higher BMI z-scores than both Caucasian and Hispanic youth (all ps < .001). Additionally, Caucasian youth had significantly higher BMI z-scores compared to Hispanic youth (p < .001).

Table 1.

Group Demographics, Measures of Body Size, ChEAT, and CDI

| Hispanic (n= 121) | Caucasian (n= 129) | African American (n= 158) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 11.55±2.09 | 13.11±2.44 | 13.71±2.23 | .001 |

| Sex (%F) | 48.78% | 61.94% | 65.66% | .02 |

| BMI z-score1 | 2.24±.03 | 2.47±.03 | 2.67±.03 | <.001 |

| Waist circumference z-score1 | 1.51±.07 | 1.68±.06 | 1.80±.06 | .01 |

| Body Fat Mass2 (kg)2 | 35.76±1.38 | 43.69±1.25 | 51.95±1.20 | <.001 |

| ChEAT* Total Score3 | 11.88±0.90 | 10.31±0.83 | 10.54±0.83 | .47 |

| CDI** Total Score3 | 8.25±.56 | 7.43±.47 | 7.38±.49 | .48 |

| Binge Eating Prevalence (%)4 | 30ab | 40a | 31b | .10 |

| Full Syndrome Binge Eating Disorder %)4 | 10.7a | 7.0ab | 4.4b | .09 |

Adjusted for age and sex,

Adjusted for age, sex, and height,

Adjusted for age, sex, and BMI zscore,

Adjusted for age, sex, body fat, and height,

Children’s Eating Attitudes Test,

Children’s Depression Inventory

3.2 Binge Eating Percentages

In a logistic regression model including age, sex, race, body fat mass, and height as predictor variables, the odds of parent-reported binge eating were lower in African American compared to Caucasian youth (OR = .56, p = .03, 95% CI [.33,.96]). Caucasian and Hispanic youth did not differ significantly (OR = .87, p = .65, 95% CI [.48, 1.57]). In a separate logistic regression model, also including age, sex, race, body fat mass, and height, the odds of parent-reported full-syndrome BED was higher among Hispanic, compared to African American youth (OR = 3.70, p = .03, 95% CI [1.13, 12.17]). Caucasian and Hispanic youth did not differ significantly (OR = 2.12, p = .16, 95% CI [.75, 5.98]. No child met criteria for bulimia or anorexia nervosa.

3.3 Relationship between Binge Eating, Race/Ethnicity, and Physiological Measures

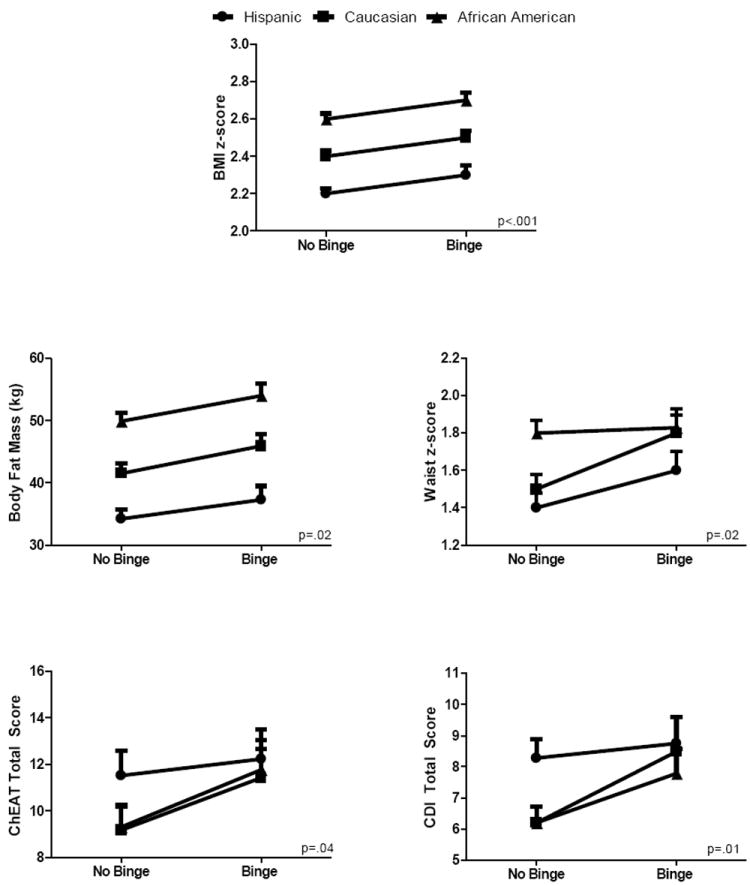

In a MANCOVA model controlling for age, sex, and race, across racial/ethnic categories, binge eating was positively associated with BMI z-score (F(1,389) = 12.47, p < .001) and waist circumference z-score (F(1,389) = 5.85, p = .02). In an ANOVA model adjusting for age, sex, race, and height, binge eating was related to body fat mass (F(1,380) = 5.65, p = .02). Across all measures of body composition, there was no significant interaction between binge eating and race (all ps > .05). Results are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Graphs indicate the main effect of binge eating, across racial/ethnic groups. Binge eating is related to body composition variables (BMI z-score, waist circumference z-score) when accounting for age and sex. Body fat mass related to binge eating when adjusting for age, sex, and height. Psychosocial variables related to binge eating when accounting for age, sex, and BMI z-score, across racial/ethnic group. The interaction of race/ethnicity and binge eating was non-significant across all variables.

3.4 Relationship between Binge Eating, Race/Ethnicity, and Psychological Measures

In individual ANOVA models controlling for age, sex, race, and BMI z-score, across racial/ethnic categories, there was a main effect for binge eating on the total scores of the ChEAT (F(1,306) = 4.14, p = .04) and the CDI (F(1,382) = 6.82, p = .01). In similar ANOVA models controlling for age, sex, race, body fat mass, and height, the main effect remained significant on the CDI (F(1,373 = 6.71, p = .01), but reduced to a trend on the ChEAT (F(1,298 = 3.70, p = .06). Overall, youth with binge eating reported greater disordered eating attitudes and depressive symptoms compared to youth without binge eating (see Figure 1). There was no significant race by binge eating status interaction on the ChEAT or the CDI total scores (all ps > .05).

3.5 Post-hoc Analyses by Sex

Post hoc analyses were conducted to examine physiological and psychological variables among boys and girls separately. When only examining the girls (n = 237), all findings remained the same, except with regard to the CDI, which became trend (F(1, 224) = 3.63, p = .06), and on the ChEAT, which was no longer significant. Although mean values were in the expected direction when examining the boys (n=160), with those with binge eating having greater body composition and psychopathology compared to those without binge eating, these relationships were no longer significant, with exception of the ChEAT (F(1,118) = 5.13, p = .03). Notably, as the sample included fewer boys than girls, the observed power to detect significant differences in these post-hoc analyses was lower for boys than for girls. To further examine potential differences between boys and girls, an interaction term between sex and binge eating was entered into the model for all analyses examining physiological and psychological variables. Across all variables, there was no significant interaction between sex and binge eating.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the relationship between parent report of binge eating, body composition, and psychosocial variables among a large, racially and ethnically diverse sample of obese treatment-seeking youth. We found that, among obese treatment-seeking youth, parent-reported binge eating is related to body composition and psychosocial variables. Specifically examining racial and ethnic differences, parent-reported binge eating was most prevalent among Caucasian youth, followed by Hispanic, then African American youth. Regardless of racial or ethnic background, parents’ report of binge eating was associated with children’s adiposity, disordered eating attitudes, and depressive symptoms.

Parent report of binge eating was prevalent across racial and ethnic categories, with overall rates similar to previous findings among obese treatment-seeking samples comprised primarily of Caucasian youth.31 Similar to results from community-based survey studies,12,14 approximately one-third of parents of Hispanic youth reported that their child experienced binge eating. Of particular note, while parents of Caucasian youth were significantly more likely than parents of African American youth to report that their child experienced binge eating, this difference was not statistically significant between Caucasian and Hispanic youth, supporting community-based and survey studies showing that binge eating is prevalent among the Hispanic population. While reports of full-syndrome BED during adolescence are limited, the prevalence of parent-reported BED found in this study also mirrored prior findings.4 Importantly, full syndrome parent report of BED was most prevalent among Hispanic youth, with Hispanic children and adolescents having significantly greater odds of parent-reported full-syndrome BED compared to African American youth.

Consistent with prior studies linking child4 and parent22 reported binge eating to greater psychological distress, in the present study, parent report of binge eating was related to children’s reports of disordered eating attitudes and symptoms of depression, accounting for the contribution of body weight. Race did not moderate this relationship, indicating that binge eating conferred emotional distress beyond that associated with obesity, independent of racial or ethnic category. When analyzing boys and girls separately, the relationships between binge eating and physiological and psychological variables initially appeared to be stronger among the girls in the sample. However, further analysis did not confirm this finding, suggesting that either our analyses were underpowered to determine a significant interaction between sex and binge eating, or alternatively, that no true sex difference exists. While some data indicate that binge eating may be more common in females,32,33 there is no evidence to suggest that associated psychopathology differs based on sex. Therefore, additional research is needed to examine sex differences with regard to physiological and psychosocial variables associated with binge eating during childhood.

Although our data are limited by parent-report of binge eating, in contrast to most prior studies of weight-loss treatment seeking youth,34 the findings from this study indicate that youth experiencing binge eating had higher measures of body adiposity when compared to youth not experiencing binge eating. Current data investigating the impact of binge eating on weight loss treatment outcome among youth are emergent, with some,9 but not all7 studies showing that binge eating has a negative impact on successful weight loss. There is evidence that psychological treatment of binge eating during adulthood stabilizes weight and leads to modest weight loss, suggesting that binge eating may also be an important factor to consider in obesity prevention and treatment during youth.35 Indeed, preliminary data suggest that targeting binge eating in youth may also reduce excessive weight gain.36,37 Although additional research is required to determine the impact of binge eating on effective weight loss during youth, the results from the present study highlight the importance of considering binge eating in the treatment of obese youth seeking weight-loss treatment.

The primary strengths of this study are the large sample size and the racial and ethnic diversity of our sample, as most studies of treatment-seeking youth to date have exclusively examined Caucasian youth. Furthermore, we used well-validated questionnaires and actual, versus self-reported, measurements of body composition. Limitations include using parent, as opposed to child, report of binge eating. Consequently, findings from this study may reflect how parents report binge eating, rather than true prevalence rates across racial and ethnic groups. Indeed, prior studies have shown low concordance between parent and child report on questionnaire18,22 and interview38 assessment of pediatric binge eating. However, it is noteworthy that parent-child agreement on report of binge and disordered eating is improved among overweight youth relative to non-overweight youth,22,23 suggesting improved accuracy for the findings of this study. However, in light of prior research and lack of a clear gold-standard approach for assessing binge eating in childhood, our findings must be replicated with data based on children’s own reports. An additional limitation of the current investigation is recruitment differences between studies. The recruitment criteria for the two studies conducted at NIH specifically included youth with weight-related health co-morbidities, while the study investigating Hispanic youth at CNMC excluded such youth. Therefore, by default, the NIH studies recruited a more obese subset of the obese child population. It is possible that this difference in inclusion/exclusion criteria yielded a different type of subject population at the two study sites, providing potential confounding within our sample. Nevertheless, relationships were found after accounting for adiposity, lending credence to our results. Finally, this study is limited by its cross-sectional design in that the relationships between obesity, binge eating, and psychosocial difficulties can be observed, but directional causality between these variables cannot be determined.

In conclusion, parent-reported binge eating is prevalent among weight-loss treatment-seeking Hispanic, Caucasian, and African American obese youth. Furthermore, binge eating is associated with adiposity and psychological distress. These data highlight the need for continued research investigating the impact of binge eating on weight in childhood and adolescence and potential differential treatment methods for obese youth seeking weight-loss treatment.

Highlights.

Parent-report of binge eating in a diverse sample of obese treatment-seeking youth

Odds of binge eating were lowest among African American youth

Odds of binge eating did not differ between Caucasian and Hispanic youth

Binge eating was related to body composition and symptoms of psychological distress

Binge eating associations were not moderated by race or ethnicity

Acknowledgments

Research support: CNMC research was supported by NIH Grants K23-RR022227 (to N. Mirza) and MO1-RR-020359 awarded by the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR, Bethesda, MD) to support the General Clinical Research Center (GCRC) at Children’s National Medical Center. NICHD research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, grant 1ZIAHD000641 (to J. Yanovski). J. Yanovski is a commissioned officer in the U.S. Public Health Service, DHHS.

Role of Funding Sources

Section on Growth and Obesity research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, grant 1ZIAHD000641. The Children’s National Medical Center study was supported by NIH Grant K23-RR022227 (to N. Mirza) and MO1-RR-020359 awarded by the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR, Bethesda, MD) to support the General Clinical Research Center (GCRC) at Children’s National Medical Center. No funding agencies had any role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Contributors

Nazrat Mirza and Marian Tanofsky-Kraff contributed to the design and implementation of the studies comprising this research paper. Camden Elliott conducted literature searches, provided summaries of previous research studies, and conducted the statistical analysis. Camden Elliott also wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer: The opinions and assertions expressed herein are those of the authors and are not to be construed as reflecting the views of USUHS or the U.S. Department of Defense.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Lamb MM, Flegal KM. Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007-2008. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;303(3):243–249. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevanlence and treand in obesity among US adults, 1999-2008. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;303(3):235–241. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. 4. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanofsky-Kraff M. Binge Eating Among Children and Adolescents. In: Jelalian E, Steele RG, editors. Handbook of Childhood and Adolescent Obesity. Springer US; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Cohen ML, Yanovski SZ, Cox C, Theim KR, Keil M, et al. A prospective study of psychological predictors of body fat gain among children at high risk for adult obesity Pediatrics. 2006;117(4):1203–1209. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Field AE, Austin SB, Taylor CB, Malspeis S, Rosner B, Rockett HR, et al. Relation between dieting and weight change among preadolescents and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2003;112(4):900–906. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.4.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braet C, Tanghe A, Decaluwé V, Moens E, Rosseel Y. Inpatient treatment for children with obesity: Weight loss, psychological well-being, and eating behavior. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2004;29(7):519–529. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levine MD, Ringham RM, Kalarchian MA, Wisniewski L, Marcus MD. Overeating among seriously overweight children seeking treatment: Results of the children’s eating disorder examination. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2006;39(2):135–140. doi: 10.1002/eat.20218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wildes JE, Marcus MD, Kalarchian MA, Levine MD, Houck PR, Cheng Y. Self-reported binge eating in severe pediatric obesity: Impact on weight change in a randomized controlled trial of family-based treatment. INternational Journal of Obesity. 2010;34(7):1143–1148. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Shomaker LB, Olsen C, et al. A prospective study of pediatric loss of control eating and psychological outcomes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120(1):108–118. doi: 10.1037/a0021406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stice E, Marti CN, Shaw H, Jaconis M. An 8-year longitudinal study of the natural history of threshold, subthreshold, and partial eating disorders from a community sample of adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118(3):587–597. doi: 10.1037/a0016481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Croll J, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Ireland M. Prevalence and risk and protective factors related to disordered eating behaviors among adolescents: Relationship to gender and ethnicity. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31(2):166–175. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00368-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neumark-Sztainer D, Croll J, Story M, Hannan PJ, French SA, Perry C. Ethnic/racial differences in weight-related concerns and behaviors among adolescent girls and boys: Findings from Project EAT. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;53(5):963–974. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00486-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.French SA, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D, Downes B, Resnick M, Blum R. Ethnic differences in psychosocial and health behavior correlates of dieting, purging, and binge eating in a population-based sample of adolescent females. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1997;22(3):315. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199711)22:3<315::aid-eat11>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson WG, Rohan KJ, Kirk AA. Prevalence and correlates of binge eating in white and African American adolescents. Eating Behaviors. 2002;3(2):179–189. doi: 10.1016/s1471-0153(01)00057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDuffie JR, Calis KA, Uwaifo Gl, Sebring NG, Fallon EM, Frazer TE, et al. Efficacy of orlistat as an adjunct to behavioral treatment in overweight African American and Caucasian adolescents with obesity-related co-morbid conditions. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2004;17(3):307–319. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2004.17.3.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mirch MC, McDuffie JR, Yanovski SZ, Schollnberger M, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Theim KR. Effects of binge eating on satiation, satiety, and energy intake of overweight children. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2006;84(4):732–738. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.4.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson WG, Grieve FG, Adams CD, Sandy J. Measuring binge eating in adolescents: Adolescent and parent versions of the Questionnaire on Eating and Weight Patterns. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1999;26(3):301–314. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199911)26:3<301::aid-eat8>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spitzer RL, Yanovski S, Wadden T, Wing R, Marcus MD, Stunkard AJ. Binge eating disorder: its further validation in a multisite study. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1993;13(2):137–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson WG, Kirk AA, Reed AE. Adolescent version of the questionnaire of eating and weight patterns: Reliability and gender differences. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2001;29(1):94–96. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(200101)29:1<94::aid-eat16>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braet C, Van Strien T. Assessment of emotional, externally induced and restrained eating behaviour in nine to twelve-year-old obese and nonobese children. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35(9):863–873. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steinberg E, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Cohen M, Elberg J, Freedman RJ, Semega-Janneh M, et al. Comparison of the child and parent forms of the Questionniare on Eating and Weight Patterns in the assessment of childnre’s eating-disordered behaviors. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2004;36(2):183–194. doi: 10.1002/eat.20022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braet C, Soetens B, Moens E, Mels S, Goossens L, Van Vlierberghe L. Are two informants better than one? Parent shild agreement on the eating styles of children who are overweight. European Eating Disorders Review. 2007;15(6):410–417. doi: 10.1002/erv.798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maloney MJ, McGuire J, Daniels SR, Specker BP. Dieting behavior and eating attitudes in children. Pediatrics. 1989;84(3):482–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vander wal JS, Thomas N. Predictors of body image dissatisfaction and disturbed eating attitudes and behaviors in African American and Hispanic girls. Eating Behaviors. 2004;5(4):291–301. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kovacs M. The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1995;21:995–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, Grummer-Strawn LL, Flegal KM, Mei Z, et al. 2000 CDC growth charts for the United States: Methods and development. Vital Health Statistics. 2002;11(246):1–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fernandez JR, Redden DT, Piertrobelli A, Allison DB. Waist circumference percentiles in a nationally representative samples of African-American, European-American, and Mexican-American children and adolescents. Journal of Pediatrics. 2004;145(4):439–444. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Behrens JT. Principles and procedures of exploratory data analysis. Psychological Methods. 1977;2(2):131–160. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tukey JW. Exploratory Data Analysis. Reading: Addison-Wesley; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Decaluwé V, Braet C, Fairburn CG. Binge eating in obese children and adolescents. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2003;33(1):78–84. doi: 10.1002/eat.10110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Decaluwé V, Braet C. Prevalence of binge-eating disorder in obese children and adolescents seeking weight-loss treatment. International Journal of Obesity. 2003;27:404–409. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goossens L, Soenens B, Braet C. Prevalence and characterisitics of binge eating in an adolescent community sample. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2009;38(3):342–353. doi: 10.1080/15374410902851697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berkowitz R, Stunkard AJ, Stallings VA. Binge-eating disorder in obese adolescent girls. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1993;699(1):200–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb18850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Wilfley DE, Young JF, Mufson L, Yanovski SZ, Glasofer DR, et al. Preventing excessive weight gain in adolescents: Interpersonal psychotherapy for binge eating. Obesity. 2007;15(6):1345–1355. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Wilfley DE, Young JF, Mufson L, Yanovski SZ, Glasofer DR, et al. A pilot study of interpersonal psychotherapy for preventing excess weight gain in adolescent girls at-risk for obesity. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2009 doi: 10.1002/eat.20773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones M, Luce KH, Osborne MI, Taylor K, Cunning D, Doyle AC, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of an internet-facilitated intervention for reducing binge eating and overweight in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2008;121(3):453–462. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA. Comparison of child interview and parent reports of children’s disordered eating behaviors. Eating Behaviors. 2005;6(1):95–99. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]