Abstract

Background:

Connecting peptide (C-peptide) plays a role in early atherogenesis in patients with diabetes mellitus and may be a marker for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in patients without diabetes. We investigated whether serum C-peptide levels are associated with all-cause, cardiovascular-related and coronary artery disease–related mortality in adults without diabetes.

Methods:

We used data from the Third Nutrition and Health Examination Survey (NHANES III) and the NHANES III Linked Mortality File in the United States. We analyzed mortality data for 5902 participants aged 40 years and older with no history of diabetes and who had available serum C-peptide levels from the baseline examination. We grouped the participants by C-peptide quartile, and we performed Cox proportional hazards regression analysis. The primary outcome was all-cause, cardiovascular-related and coronary artery disease–related mortality.

Results:

The mean serum C-peptide level in the study sample was 0.78 (± standard deviation 0.47) nmol/L. The adjusted hazards ratio comparing the highest quartile with the lowest quartile was 1.80 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.33–2.43) for all-cause mortality, 3.20 (95% CI 2.07–4.93) for cardiovascular-related mortality, and 2.73 (95% CI 1.55–4.82) for coronary artery disease–related mortality. Higher C-peptide levels were associated with increased mortality among strata of glycated hemoglobin and fasting serum glucose.

Interpretation:

We found an association between serum C-peptide levels and all-cause and cause-specific mortality among adults without diabetes at baseline. Our finding suggests that elevated C-peptide levels may be a predictor of death.

Connecting peptide (C-peptide), a cleavage product of proinsulin, is secreted by pancreatic β cells in equimolar amounts along with insulin.1 Although a considerable amount of insulin is extracted by the liver, C-peptide is subjected to negligible first-pass metabolism by the liver, thereby serving as a surrogate marker for endogenous insulin secretion.2 C-peptide has been considered an inert by-product of insulin synthesis and has also been of great value in the understanding of the pathophysiology of type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus.2,3 However, C-peptide has recently been re-evaluated as a bioactive peptide in its own right. The administration of C-peptide to patients and animals with type 1 diabetes has been reported to have a beneficial effect on diabetes-induced abnormalities of the peripheral nerves and renal and microvascular function.4,5 C-peptide deposition occurs in the atherosclerotic lesions of patients with diabetes.6 Recent studies have suggested that C-peptide may be a valuable predictor of cardiovascular events and mortality (all-cause and cardiovascular-related mortality).6–12

In this study, we investigated the association between serum C-peptide level and all-cause, cardiovascular-related and coronary artery disease–related mortality among patients without diabetes. We also estimated mortality as C-peptide increased across glycated hemoglobin and fasting blood glucose quartiles.

Methods

Study population

We used data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III, 1988–94) database13 and the NHANES III Linked Mortality Public-use File from the United States. The latter was a follow-up study of mortality that matched records from NHANES III with data in the National Death Index as of Dec. 31, 2006. NHANES III included 39 695 participants aged 2 months and older, with a weighted response rate of 82% for household interviews and 73% for examinations.14 The date and cause of death in the National Death Index were derived from death certificates.15

From NHANES III, we included 9314 participants aged 40 years or more who had serum C-peptide levels available at the time of the initial survey. We excluded 1543 patients with diabetes, defined as having a fasting plasma glucose level of at least 6.99 mmol/L, a nonfasting plasma glucose level of at least 11.1 mmol/L, current insulin use or a prior physician diagnosis of diabetes; we also excluded 1869 participants who had missing data for other variables. The cohort analysis presented in this study was based on 5902 participants in NHANES III. The NHANES is a publicly released data set; thus, we did not require informed consent to use these data. This study was exempt from the institutional review board approval of Ajou University Hospital.

Baseline data collection

Participants were interviewed as part of NHANES III to obtain information about age (40–49, 50–59, 60–69, ≥ 70 yr), sex, ethnic background (white, black, Hispanic or other), education (less than high school, high school graduate, college or more), smoking status (current, former, never) and alcohol consumption (drinker, nondrinker). Data about disease history were also collected. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure of 140 mm Hg or higher and diastolic blood pressure of 90 mm Hg or higher, the use of antihypertensive drugs or previous physician-diagnosed hypertension. Hypercholesterolemia was defined as a serum total cholesterol level of 6.19 mmol/L or higher, current medication use or physician-diagnosed hypercholesterolemia. The day on which each participant’s last meal or snack was consumed was grouped as “yesterday” or “today.” C-reactive protein (< 1, ≥ 1 mg/dL), total cholesterol (< 5.15, 5.15–6.18, ≥ 6.19 mmol/L), triglycerides (< 2.26, 2.26–5.65, > 5.65 mmol/L), serum insulin (< 6.38, 6.38–8.92, 8.93–12.80, > 12.80 μU/mL, glycated hemoglobin (< 5.2%, 5.2%–5.4%, 5.5%–5.8%, > 5.8%), and fasting serum glucose (< 4.98, 4.98–5.30, 5.31–5.68, > 5.68 mmol/L) were included as biomarkers of risk of death.

C-peptide measurement

The methods used for C-peptide measurement and quality control during the baseline examination have been previously described in detail.16 The C-peptide radioimmunoassay is a 3-day batch, sequential-saturation method.17 Briefly, antibody-bound proinsulin is removed by polyethylene glycol (PEG) precipitation. The supernatants from the PEG-precipitated samples, controls and standards are incubated with a fixed amount of C-peptide antiserum. During this incubation, unlabelled C-peptide binds to the antibody. A fixed amount of iodine 125-labelled C-peptide is then added and incubated again; during this incubation period, the radiolabelled C-peptide binds to available antibody sites to which unlabelled C-peptide is not bound. The bound and unbound antibody fractions are separated by precipitating the antibody. The radioactivity of the bound portion is then quantified using a gamma counter. The C-peptide concentrations are interpolated from a calibration curve constructed by plotting the percentage bound to each standard versus its concentration.

Mortality follow-up

International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision (ICD-9) codes were used for deaths that occurred from 1988 through 1998, and ICD-10 codes were used for deaths that occurred from 1999 through 2000. The underlying causes of death were grouped according to the National Center for Health Statistics for each coding system. All deaths that occurred from 1988 to 1998 that were coded using ICD-9 clinical modification guidelines were classified into comparable groups based on the ICD-10 underlying causes of death.18 In addition to all-cause mortality, we also included cardiovascular disease–related mortality (ICD-10 codes I00–I99) and coronary artery disease–related mortality (ICD-10 codes I20–I25).

Statistical analysis

We divided the study population by serum C-peptide quartile (< 0.440, 0.440–0.692, 0.693–1.018, > 1.018 nmol/L). We used linear regression, χ2 tests and tests for trend to compare variables across ordered categories of serum C-peptide levels. Cox proportional hazards regression was used in the multivariable analyses of all-cause, cardiovascular-related and coronary artery disease–related mortality. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) associated with each C-peptide quartile were compared with the first quartile. The proportional hazards assumption for the model was confirmed. We determined Kaplan–Meier estimates, stratified by C-peptide quartile, for all-cause and cause-specific mortality.

To further assess whether serum C-peptide level predicts death, we compared estimates of all-case, cardiovascular-related and coronary artery disease–related mortality according to C-peptide level and either glycated hemoglobin or fasting serum glucose by stratifying each variable into quartiles.

Results

The mean serum C-peptide level among participants was 0.78 (± standard deviation [SD] 0.47) nmol/L. Participants with higher C-peptide levels were more likely to be older, male, Hispanic, have less than a high school education, be a former smoker or a nondrinker, as well as to have had their last meal or snack on the day the sample was collected. Higher levels were also found among those with a history of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia or heart attack, and among those with a higher BMI and with higher levels of C-reactive protein, total cholesterol, triglycerides, serum insulin, glycated hemoglobin and fasting serum glucose (Table 1).

Table 1:

Mean serum connecting peptide (C-peptide) levels of participants (n = 5902) at baseline, by characteristic

| Characteristic | No. | Mean serum C-peptide level ± SD, nmol/L | p value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | |||

| 40–49 | 1817 | 0.73 ± 0.48 | < 0.001 |

| 50–59 | 1185 | 0.73 ± 0.43 | |

| 60–69 | 1370 | 0.80 ± 0.46 | |

| ≥ 70 | 1530 | 0.85 ± 0.49 | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 3211 | 0.81 ± 0.48 | < 0.001 |

| Female | 2691 | 0.74 ± 0.46 | |

| Ethnic background | |||

| White | 3192 | 0.77 ± 0.45 | < 0.001 |

| Black | 1335 | 0.74 ± 0.49 | |

| Hispanic | 1185 | 0.85 ± 0.48 | |

| Other | 190 | 0.74 ± 0.45 | |

| Education | |||

| Less than high school | 1472 | 0.84 ± 0.49 | < 0.001 |

| High school | 2677 | 0.78 ± 0.46 | |

| College or more | 1753 | 0.72 ± 0.45 | |

| Cigarette smoking | |||

| Current smoker | 1520 | 0.74 ± 0.48 | <0.001 |

| Former smoker | 2190 | 0.83 ± 0.47 | |

| Never smoked | 2192 | 0.75 ± 0.45 | |

| Alcohol use | |||

| Drinker | 2985 | 0.73 ± 0.45 | < 0.001 |

| Nondrinker | 2917 | 0.82 ± 0.48 | |

| Day of last meal or snack | |||

| Yesterday | 3353 | 0.76 ± 0.43 | 0.02 |

| Today | 2547 | 0.79 ± 0.52 | |

| Hypertension | |||

| Yes | 2511 | 0.88 ± 0.49 | < 0.001 |

| No | 3391 | 0.70 ± 0.44 | |

| Hypercholesterolemia | |||

| Yes | 2360 | 0.81 ± 0.46 | < 0.001 |

| No | 3542 | 0.76 ± 0.47 | |

| Heart attack | |||

| Yes | 397 | 0.97 ± 0.53 | < 0.001 |

| No | 5505 | 0.76 ± 0.46 | |

| Body mass index | |||

| < 18.5 | 97 | 0.43 ± 0.34 | < 0.001 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 2028 | 0.55 ± 0.36 | |

| 25–29.9 | 2311 | 0.81 ± 0.42 | |

| ≥ 30 | 1466 | 1.07 ± 0.50 | |

| C-reactive protein, mg/dL | |||

| < 1 | 5332 | 0.76 ± 0.45 | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 1 | 570 | 0.95 ± 0.56 | |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | |||

| < 5.15 | 2093 | 0.75 ± 0.49 | < 0.001 |

| 5.15–6.18 | 2206 | 0.77 ± 0.45 | |

| ≥ 6.19 | 1603 | 0.82 ± 0.46 | |

| Triglyceride, mmol/L | |||

| < 2.26 | 4733 | 0.71 ± 0.43 | < 0.001 |

| 2.26–5.65 | 1072 | 1.06 ± 0.53 | |

| > 5.65 | 97 | 1.10 ± 0.49 | |

| Serum insulin, μU/mL | |||

| < 6.38 | 1477 | 0.36 ± 0.20 | < 0.001 |

| 6.38–8.92 | 1475 | 0.60 ± 0.23 | |

| 8.93–12.80 | 1475 | 0.84 ± 0.28 | |

| > 12.80 | 1475 | 1.31 ± 0.47 | |

| Glycated hemoglobin, % | |||

| < 5.2 | 1628 | 0.69 ± 0.44 | < 0.001 |

| 5.2–5.4 | 1399 | 0.74 ± 0.45 | |

| 5.5–5.8 | 1418 | 0.77 ± 0.44 | |

| > 5.8 | 1457 | 0.93 ± 0.51 | |

| Plasma glucose, mmol/L | |||

| < 4.98 | 1465 | 0.60 ± 0.42 | < 0.001 |

| 4.98–5.30 | 1482 | 0.70 ± 0.42 | |

| 5.31–5.68 | 1482 | 0.80 ± 0.42 | |

| > 5.68 | 1473 | 1.00 ± 0.51 | |

Note: SD = standard deviation.

p values were calculated using t test for binomial groups and Wald F-test for categorical groups.

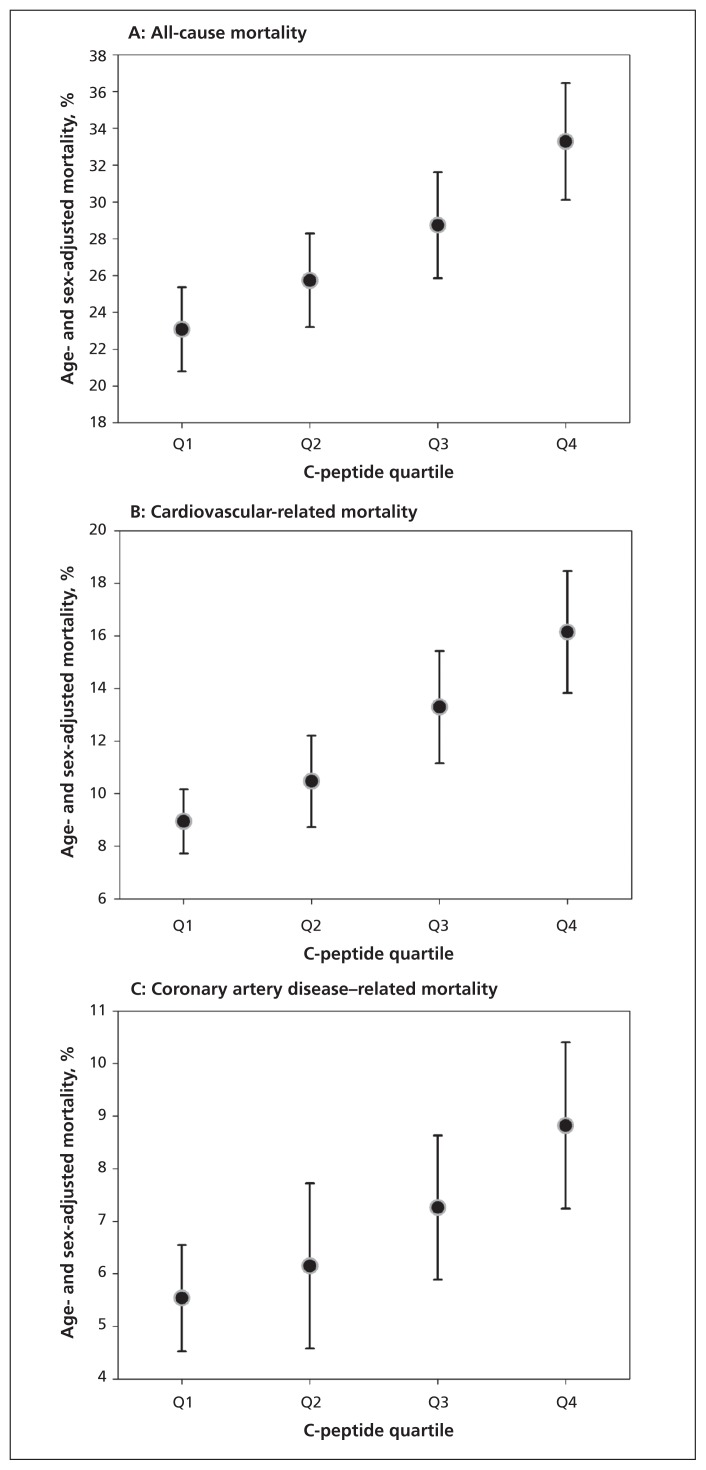

The age- and sex-adjusted standardized all-cause, cardiovascular-related and coronary artery disease–related mortality are presented in Figure 1. The mortality rate increased over the quartiles of C-peptide.

Figure 1:

Age- and sex-standardized all-cause, cardiovascular-related and coronary artery disease–related mortality by connecting peptide (C-peptide) quartile at baseline. C-peptide quartiles: quartile 1: < 0.440 nmol/L; quartile 2: 0.440–0.692 nmol/L; quartile 3: 0.693–1.018 nmol/L; quartile 4: > 1.018 nmol/L.

Table 2 shows the HRs for all-cause, cardiovascular-related and coronary artery disease–related mortality by C-peptide quartile at baseline. After multivariable adjustment, a 1 ng/mL increase in C-peptide level was associated with a 1.41-fold (95% CI 1.27–1.57) increased risk of all-cause mortality, a 1.70-fold (95% CI 1.41–2.06) increased risk of cardiovascular-related mortality, and a 1.67-fold (95% CI 1.27–2.19) increase risk of coronary artery disease–related mortality. Compared to participants in the lowest C-peptide quartile, those in the highest quartile had an adjusted HR of 1.80 (95% CI 1.33–2.43) for all-cause mortality, 3.20 (95% CI 2.07–4.93) for cardiovascular-related mortality and 2.73 (95% CI 1.55–4.82) for coronary artery disease–related mortality. Significant dose–response relations were observed for the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular-related mortality. The effect on coronary artery disease–related mortality was borderline significant.

Table 2:

Adjusted hazard ratios for all-cause, cardiovascular-related and coronary artery disease–related mortality, by serum connecting peptide (C-peptide) level at baseline

| C-peptide level | All-cause mortality | Cardiovascular-related mortality | Coronary artery disease–related mortality | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Events, no. (%) | Adjusted HR* (95% CI) | Events, no. (%) | Adjusted HR* (95% CI) | Events, no. (%) | Adjusted HR* (95% CI) | |

| Increase per unit of C-peptide | 1.41 (1.27–1.57) | 1.70 (1.41–2.06) | 1.67 (1.27–2.19) | |||

|

| ||||||

| C-peptide quartile, nmol/L | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Quartile 1 (< 0.440) | 389 (26.4) | 1.00 (ref) | 146 (9.9) | 1.00 (ref) | 88 (6.0) | 1.00 (ref) |

|

| ||||||

| Quartile 2 (0.440–0.692) | 484 (32.7) | 1.33 (1.08–1.63) | 210 (14.2) | 1.62 (1.13–2.33) | 114 (7.7) | 1.52 (0.98–2.36) |

|

| ||||||

| Quartile 3 (0.693–1.018) | 533 (36.1) | 1.56 (1.23–1.98) | 244 (16.5) | 2.45 (1.71–3.51) | 142 (9.6) | 2.11 (1.27–3.50) |

|

| ||||||

| Quartile 4 (> 1.018) | 614 (41.6) | 1.80 (1.33–2.43) | 295 (20.0) | 3.20 (2.07–4.93) | 171 (11.6) | 2.73 (1.55–4.82) |

|

| ||||||

| p value for trend | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.07 | |||

Note: CI = confidence interval, HR = hazard ratio, ref = reference.

Adjusted for age, sex, ethnic background, education, smoking status, alcohol consumption status, day on which the last meal or snack was consumed, history of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, heart attack and body mass index, as well as C-reactive protein, total cholesterol, triglyceride, serum insulin, glycated hemoglobin and fasting serum glucose levels.

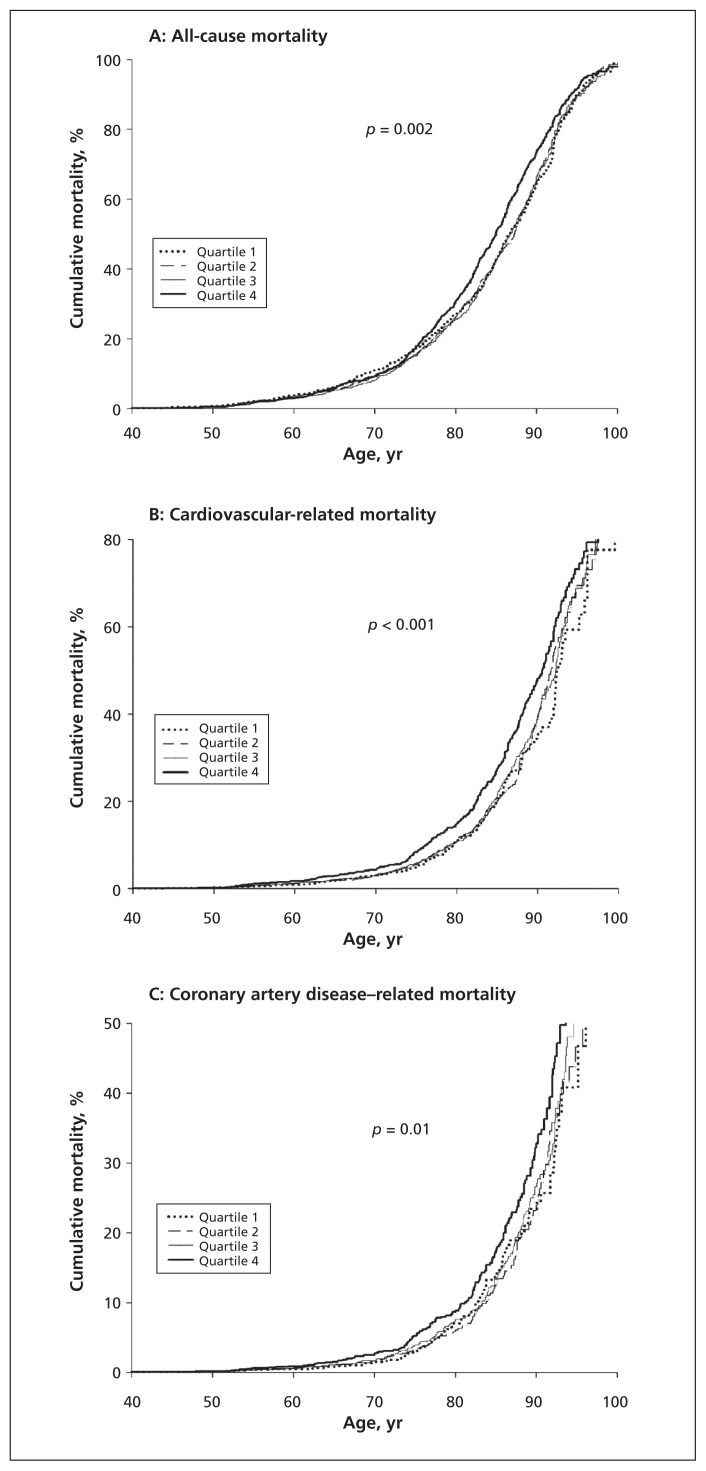

In the Kaplan–Meier survival curves for cumulative all-cause, cardiovascular-related and coronary artery disease–related mortality (Figure 2), higher levels of C-peptide were significantly associated with increases in mortality at baseline and over 40 years of age (all-cause mortality p = 0.002; cardiovascular-related mortality p < 0.001; coronary artery disease–related mortality p = 0.01).

Figure 2:

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for cumulative all-cause, cardiovascular-related and coronary artery disease–related mortality by connecting peptide (C-peptide) quartile at baseline. C-peptide quartiles: quartile 1: < 0.440 nmol/L; quartile 2: 0.440–0.692 nmol/L; quartile 3: 0.693–1.018 nmol/L; quartile 4: > 1.018 nmol/L.

We compared the mortality estimates for all-cause, cardiovascular-related and coronary artery disease–related mortality across serum C-peptide quartiles for glycated hemoglobin and fasting serum glucose (Appendix 1, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.121950/-/DC1). There was no interaction between C-peptide and glycated hemoglobin or fasting serum glucose. As the C-peptide quartile increased, mortality showed graded and significant increases regardless of increases in the levels of glycated hemoglobin and fasting serum glucose.

Interpretation

In this prospective cohort study of a representative sample of the US population, we found that serum C-peptide level was significantly associated with all-cause mortality, as well as with cardiovascular-related and coronary artery disease–related mortality, among participants without diabetes at baseline. Participants who had high serum C-peptide levels (> 1.018 nmol/L) had a 1.8- to 3.2-fold increased risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality compared with those who had low C-peptide levels (< 0.440 nmol/L). This risk was progressive: after adjustment, each 1-unit increase in baseline C-peptide level was associated with 41%–70% increases in the relative risk of death. We found that C-peptide level better predicted all-cause, cardiovascular-related and coronary artery disease–related mortality than did glycated hemoglobin or fasting blood glucose level.

Our findings are consistent with the results of previous studies and suggest a role for C-peptide in predicting increased risk of cardiovascular events and death regardless of the presence of diabetes.6–12 Among patients with type 2 diabetes, C-peptide level has been reported to be significantly correlated with intima-media thickness,10 triglyceride level, high-density lipoproten cholesterol levels, leptin levels and BMI.8 The Wisconsin Epidemiologic Study of Diabetic Retinopathy followed 1007 individuals with older-onset diabetes over 16 years.19 In their study, higher levels of plasma C-peptide (per 1 nmol/L) were associated with increased all-cause mortality among women and with ischemic heart disease mortality and stroke mortality among men.19 Furthermore, the C-peptide levels of patients who underwent coronary angiography were associated with all-cause and cardiovascular-related mortality, independent of markers of glucose metabolism.12 Those in the higher tertiles of C-peptide had higher levels of markers of endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis, as well as more severe coronary lesions.12 A community-based survey of adults aged 30 years and older with normal glucose tolerance found that serum C-peptide levels were quantitatively associated with the signs and symptoms of metabolic syndrome X, including BMI, triglyceride level, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level and blood pressure.7,9 The recent study by Patel and colleagues11 found that C-peptide levels were superior to other known indices (e.g., serum insulin, the homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance, and the quantitative insulin sensitivity check index) in predicting all-cause and cardiovascular-related mortality among adults without diabetes.

We found that serum C-peptide level was more predictive of all-cause, cardiovascular-related and coronary artery disease–related mortality compared with glycated hemoglobin and fasting blood glucose levels. Glycated hemoglobin is an indicator of average blood glucose concentrations over the past 3 months and has been suggested as a diagnostic or screening tool for diabetes. Among adults without diabetes, elevated glycated hemoglobin levels have been shown to be associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events and death.20,21 Fasting blood glucose level is the most commonly used indicator of overall glucose homeostasis and is predictive of the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular-related mortality below the diabetic threshold.22,23 Although glycated hemoglobin and fasting blood glucose levels are known risk factors for death, we found that serum C-peptide level was a stronger predictor of the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular-related death than the former 2 parameters among people without diabetes, and we found that mortality risk increased with increasing serum C-peptide levels. More importantly, even among participants in the lowest quartiles of glycated hemoglobin and fasting blood glucose, the estimates of mortality gradually increased with increasing C-peptide levels. Thus, our finding may add to the evidence that elevated C-peptide levels are a predictor of adverse outcomes.

The reason for the increased risk of death among people with high C-peptide levels is uncertain, but the potential involvement of C-peptide in atherogenesis may help explain the observed association. Experimental studies have shown that C-peptide colocalizes with intimal monocytes, macrophages and CD4-positive lymphocytes and that, in vitro, C-peptide induces monocyte and T-cell chemotaxis.6,24 Furthermore, C-peptide activated the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells through the activation of Src kinase, phosphoinositide 3-kinase, and extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases 1 and 2.25 In epidemiologic studies, elevated C-peptide levels have been associated with atherogenic risk factors, including increased levels of triglycerides and high-density lipoprotein and high blood pressure.7–9 Although we included participants without diabetes at baseline, some of these individuals may have prediabetes and atherogenic risk factors (possibly caused by obesity, hyperglycemia and, especially, hyperinsulinemia) before the onset of clinical diabetes.26 The existing evidence strongly supports the proatherogenic action of C-peptide, which, by extension, enables C-peptide to be an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease and subsequent death.

Limitations

The limitations of this study include a single measurement of serum C-peptide level at baseline and a long interval between measurement and follow-up. In addition, serum C-peptide levels can differ depending on the time of measurement; namely, C-peptide levels have been reported to be higher in people examined in the morning compared with those examined in the afternoon.27 We did not address the influence of changes in C-peptide levels on the risk of death, such as through the use of medications that alter C-peptide levels or insulin resistance.

Misclassification bias is possible. Although we excluded participants with diabetes (defined as elevated plasma glucose or nonfasting plasma glucose levels, insulin use or a previous diagnosis of diabetes), some individuals may have had undetected diabetes, leading to the overestimation of the HRs. However, we could not adjust for this limitation with respect to the linear trend between serum C-peptide levels and mortality.

Because of the observational nature of this study, we cannot rule out the possibility of residual confounding effects caused by unmeasured confounding variables.

Conclusion

We found a significant association between serum C-peptide levels and risk of all-cause, cardiovascular-related and coronary artery disease–related mortality among adults without diabetes. We also observed a stepwise increase in the risk of death with increasing levels of C-peptide across the quartiles of glycated hemoglobin and fasting blood glucose levels. Our findings support the potential relevance of serum C-peptide as a predictor of adverse health outcomes and indicate that elevated C-peptide levels may be an important predictive marker of an increased risk of death.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

The authors thank members of the National Center for Health Statistics of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Jin-young Min analyzed the data and wrote the initial manuscript. Kyoung-bok Min analyzed the data, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. Both authors approved the final version submitted for publication,

Funding: This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (grant no. NRF-2012R1A1A1041318).

References

- 1.Horwitz DL, Kuzuya H, Rubenstein AH. Circulating serum C-peptide: a brief review of diagnostic implications. N Engl J Med 1976;295:207–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark PM, Hales CN. How to measure plasma insulin. Diabetes Metab Rev 1994;10:79–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Webb PG, Bonser AM. Basal C-peptide in the discrimination of type I from type II diabetes. Diabetes Care 1981;4:616–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ido Y, Vindigni A, Chang K, et al. Prevention of vascular and neural dysfunction in diabetic rats by C-peptide. Science 1997; 277:563–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johansson BL, Sjöberg S, Wahren J. The influence of human C-peptide on renal function and glucose utilization in type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetic patients. Diabetologia 1992;35:121–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marx N, Walcher D, Raichle C, et al. C-peptide colocalizes with macrophages in early arteriosclerotic lesions of diabetic subjects and induces monocyte chemotaxis in vitro. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2004;24:540–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen CH, Tsai ST, Chou P. Correlation of fasting serum C-peptide and insulin with markers of metabolic syndrome-X in a homogeneous Chinese population with normal glucose tolerance. Int J Cardiol 1999;68:179–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haban P, Simoncic R, Zidekova E, et al. Role of fasting serum C-peptide as a predictor of cardiovascular risk associated with the metabolic X-syndrome. Med Sci Monit 2002;8:CR175–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen CH, Tsai ST, Chuang JH, et al. Population-based study of insulin, C-peptide, and blood pressure in Chinese with normal glucose tolerance. Am J Cardiol 1995;76:585–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim ST, Kim BJ, Lim DM, et al. Basal C-peptide level as a surrogate marker of subclinical atherosclerosis in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Metab J 2011;35:41–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel N, Taveira TH, Choudhary G, et al. Fasting serum C-peptide levels predict cardiovascular and overall death in nondiabetic adults. J Am Heart Assoc 2012;1:e003152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marx N, Silbernagel G, Brandenburg V, et al. C-peptide levels are associated with mortality and cardiovascular mortality in patients undergoing angiography: the LURIC Study. Diabetes Care 2013;36:708–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plan and operation of the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–94. Series 1: programs and collection procedures Vital Health Stat 1 1994;July:1–407 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Analytic and reporting guidelines: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, NHANES III (1988–1994). Hyattsville (MD): National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1996. Available: www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes3/nh3gui.pdf (accessed 2013 Apr. 9). [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Center for Health Statistics NHANES III Linked Mortality File. Hyattsville (MD): The Center; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gunther EW, Lewis BL, Koncikowski SM. Laboratory procedures used for the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) 1988–1994. Atlanta (GA): US Department of Health and Human Services; 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heding LG. Radioimmunological determination of human C-peptide in serum. Diabetologia 1975;11:541–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson RN, Miniño AM, Hoyert DL, et al. Comparability of cause of death between ICD-9 and ICD-10: preliminary estimates. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2001;49:1–32 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirai FE, Moss SE, Klein BE, et al. Relationship of glycemic control, exogenous insulin, and C-peptide levels to ischemic heart disease mortality over a 16-year period in people with older-onset diabetes: the Wisconsin Epidemiologic Study of Diabetic Retinopathy (WESDR). Diabetes Care 2008;31:493–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Selvin E, Steffes MW, Zhu H, et al. Glycated hemoglobin, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk in nondiabetic adults. N Engl J Med 2010;362:800–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silbernagel G, Grammer TB, Winkelmann BR, et al. Glycated hemoglobin predicts all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality in people without a history of diabetes undergoing coronary angiography. Diabetes Care 2011;34:1355–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balkau B, Shipley M, Jarrett RJ, et al. High blood glucose concentration is a risk factor for mortality in middle-aged nondiabetic men. 20-year follow-up in the Whitehall Study, the Paris Prospective Study, and the Helsinki Policemen Study. Diabetes Care 1998;21:360–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coutinho M, Gerstein HC, Wang Y, et al. The relationship between glucose and incident cardiovascular events. A metaregression analysis of published data from 20 studies of 95,783 individuals followed for 12.4 years. Diabetes Care 1999;22:233–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walcher D, Aleksic M, Jerg V, et al. C-peptide induces chemotaxis of human CD4-positive cells: involvement of pertussis toxin-sensitive G-proteins and phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Diabetes 2004;53:1664–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walcher D, Babiak C, Poletek P, et al. C-Peptide induces vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation: involvement of SRC-kinase, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2. Circ Res 2006;99:1181–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haffner SM, Stern MP, Hazuda HP, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors in confirmed prediabetic individuals. JAMA 1990; 263:2893–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Troisi RJ, Cowie CC, Harris MI. Diurnal variation in fasting plasma glucose: implications for diagnosis of diabetes in patients examined in the afternoon. JAMA 2000;284:3157–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.