Abstract

Introduction

Immediate-release memantine (10 mg, twice daily) is approved in the USA for moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s disease (AD). This study evaluated the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of a higher-dose, once-daily, extended-release formulation in patients with moderate-to-severe AD concurrently taking cholinesterase inhibitors.

Methods

In this 24-week, double-blind, multinational study (NCT00322153), outpatients with AD (Mini-Mental State Examination scores of 3–14) were randomized to receive once-daily, 28-mg, extended-release memantine or placebo. Co-primary efficacy parameters were the baseline-to-endpoint score change on the Severe Impairment Battery (SIB) and the endpoint score on the Clinician’s Interview-Based Impression of Change Plus Caregiver Input (CIBIC-Plus). The secondary efficacy parameter was the baseline-to-endpoint score change on the 19-item Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study–Activities of Daily Living (ADCS–ADL19); additional parameters included the baseline-to-endpoint score changes on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) and verbal fluency test. Data were analyzed using a two-way analysis of covariance model, except for CIBIC-Plus (Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test). Safety and tolerability were assessed through adverse events and physical and laboratory examinations.

Results

A total of 677 patients were randomized to receive extended-release memantine (n = 342) or placebo (n = 335); completion rates were 79.8 and 81.2 %, respectively. At endpoint (week 24, last observation carried forward), memantine-treated patients significantly outperformed placebo-treated patients on the SIB (least squares mean difference [95 % CI] 2.6 [1.0, 4.2]; p = 0.001), CIBIC-Plus (p = 0.008), NPI (p = 0.005), and verbal fluency test (p = 0.004); the effect did not achieve significance on ADCS–ADL19 (p = 0.177). Adverse events with a frequency of ≥5.0 % that were more prevalent in the memantine group were headache (5.6 vs. 5.1 %) and diarrhea (5.0 vs. 3.9 %).

Conclusion

Extended-release memantine was efficacious, safe, and well tolerated in this population.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s40263-013-0077-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Introduction

The progression of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) to moderate and severe stages is associated with increasing cognitive and functional decline, greater dependence and burden on caregivers, and higher direct and indirect costs, even in non-institutionalized patients [1–4]. In addition, the challenges faced by community-dwelling patients with AD and their caregivers are often aggravated by poor medication adherence [5–7].

Memantine is an uncompetitive antagonist of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, approved in the USA and many countries worldwide for the treatment of moderate to severe AD [8–10]. In the USA, it is currently administered twice daily as an immediate-release formulation, with a maximum recommended dosage of 20 mg/day. Considering the problems associated with poor medication adherence in AD, the availability of an extended-release, once-daily memantine formulation would be expected to provide improved convenience, and may potentially enable an increased daily dosage without affecting the drug’s favorable safety and tolerability profile [11, 12].

The objective of this study was to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of a novel, higher-dose (28-mg), once-daily, extended-release memantine formulation in outpatients with moderate-to-severe AD. Stable use of any cholinesterase inhibitor was required in this study, similar to a previous trial of immediate-release memantine (10 mg, twice daily) in patients with moderate-to-severe AD who were taking the cholinesterase inhibitor donepezil [9]. In addition, the majority of participants in this study were primarily of Hispanic origin (68.9 %), including participants from Argentina, Mexico, and Chile, a patient population that has traditionally been under-represented in trials of memantine and other AD drugs [13].

Methods

Participants

Study participants were community-dwelling men and women of at least 50 years of age, with a clinical diagnosis of probable AD using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) [14] and National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke–Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS–ADRDA) [15] criteria, a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score [16] in the 3–14 range at screening and baseline, and results of a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) scan (within the past 12 months) consistent with this diagnosis. At screening, all participants were required to be receiving ongoing cholinesterase inhibitor therapy (stable dosage for at least 3 months) and to have normal (or clinically non-significant) results on physical examination, laboratory evaluations, and electrocardiogram (ECG).

Individuals were excluded from the study if, by the judgment of the investigator, they had any of the following (see Electronic Supplementary Material for a full list of inclusion and exclusion criteria): clinically significant and active pulmonary, gastrointestinal, renal, hepatic, endocrine, or cardiovascular system disease or cancer; a neurologic disorder or dementia complicated by other organic disease or predominant delusions; any DSM-IV Axis I disorder other than AD; evidence of clinically significant disease involving the central nervous system; systolic hypertension or hypotension; a modified Hachinski Ischemia Score of >4 at screening; and current or prior exposure to any unapproved concomitant medication that could not be discontinued or switched to an allowable alternative medication before baseline.

Written informed consent was provided by the patient’s caregiver and either the patient (if possible) or a legally acceptable representative. The study was designed to comply with the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) guidance on General Considerations for Clinical Trials (62 FR 6611, December 17, 1997), Nonclinical Safety Studies for the Conduct of Human Clinical Trials for Pharmaceuticals (62 FR 62922, November 25, 1997), and Good Clinical Practice: Consolidated Guidance (62 FR 25692, May 9, 1997). The protocol was reviewed and approved in the USA by an institutional review board for each site, and by both an ethics committee and a Ministry of Health agency within each of the other countries.

Trial Design

This study (MEM-MD-50; NCT00322153; http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00322153) was a multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group clinical trial in which participants were required to complete between 4 and 14 days of single-blind placebo treatment prior to baseline. At baseline, each patient was randomized (1:1) to receive placebo or extended-release memantine. The Statistical Programming department at Forest Research Institute generated (using SAS, v. 9.1.3; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and maintained a list of randomization codes in a secure area. At baseline, each patient was sequentially assigned a randomization number corresponding to treatment assignment. Medication corresponding to the randomization numbers was provided to each study site by Forest Laboratories. Patients assigned to memantine initially received 7 mg/day (once daily), and were up-titrated weekly in 7 mg/day increments, reaching the target dose of 28 mg at the beginning of week 4. By week 8, patients were required to tolerate a minimum of 21 mg/day, or they were to be discontinued from the trial. Study drug and placebo were administered in identically appearing blister packs, either in the morning or evening, and the dosing time remained consistent throughout the study. Each blister pack contained a two-part, three-panel label; the first remained on the pack, and the second and third were placed in the case report form. The third panel was sealed and contained the identity of the treatment in the event of an emergency; no treatment assignment was unblinded by this procedure or by any other procedure prior to database lock. All study sites underwent pre-study site feasibility and had to provide information to ensure that the overall education, experience, and training of study personnel were adequate to conduct clinical trials according to good clinical practice, and that the investigators were qualified and trained in both the treatment of AD and clinical research. Investigators and relevant site personnel were trained at an investigator meeting prior to the initiation of the study, which included a protocol overview and a review of study procedures, outcome measures, investigator responsibility, and recruitment. Outcome measures were administered by trained and skilled individuals during the trial.

Efficacy Parameters

The two co-primary efficacy parameters were baseline-to-endpoint change on the Severe Impairment Battery (SIB) total score [week 24, last-observation-carried-forward (LOCF) approach] and the endpoint rating on the Clinician’s Interview-Based Impression of Change Plus Caregiver Input (CIBIC-Plus) scale (week 24, LOCF). The SIB is a 40-item, 100-point scale, used to evaluate cognition in patients with advanced dementia; lower scores indicate greater impairment [17]. The CIBIC-Plus is a 7-point scale used to assess the global clinical status of a patient, with scores ranging from 1 (marked improvement) to 7 (marked worsening); raters are blinded to data from other post-baseline rating instruments and safety measures and do not have access to prior post-baseline CIBIC-Plus ratings [18]. The secondary efficacy parameter was the change on the 19-item Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study–Activities of Daily Living (ADCS–ADL19) scale, a 54-point instrument used to evaluate functional abilities in patients with moderate to severe AD; lower scores indicate greater impairment [19, 20]. Additional parameters included changes on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI), a 12-item, 144-point scale used to measure the frequency and severity of behavioral disturbances in patients with dementia (higher scores indicate greater impairment), [21] and the semantic verbal fluency test (VFT), in which patients were assessed on the basis of the number of animals they could name in 60 s [22]. All assessment scales were administered at baseline and at the end of weeks 4, 8, 12, 18, and 24, except the NPI, which was administered at weeks 8, 12, 18, and 24. The NPI caregiver distress rating, as well as two exploratory health outcomes measures (the Modified Resource Utilization in Dementia-Lite and the Caregiver Perceived Burden Questionnaire) were also administered in this study but were not analyzed for this report.

Measures of safety and tolerability included physical examinations, measurements of vital signs, laboratory tests (hematology, blood chemistry, and urinalysis), ECGs, and recordings of adverse events. Blood and urine samples were collected and ECGs were taken at screening and week 24; adverse events and vital signs were recorded at baseline and at each post-baseline visit. Any clinical findings discovered during the final examination, or at premature discontinuation, were followed until the condition returned to pre-study status or could be explained as being unrelated to the study drug. A follow-up visit could be scheduled within 30 days of termination, as needed.

Adverse events were solicited from patients and caregivers at all study visits (and during any contact with a patient or patient representative occurring outside of a defined study visit, including any contact up to 30 days after study completion), using non-leading questions such as “How do you feel?” Adverse events were coded according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (version 7.0 or newer), and an assessment of the severity, chronicity, causal relationship to study medication, and seriousness of the event was provided by an investigator. An adverse event was considered to be treatment emergent if it was not present prior to the first dose of double-blind study medication, or if it increased in severity following the dosing. Patients who experienced more than one adverse event within a specific category were counted only once.

Statistical Analysis

The study sample size was calculated on the basis of week 24 (LOCF) effect sizes (0.40 for SIB; 0.24 for CIBIC-Plus) established in a previous study of memantine (10 mg/day, twice daily) in patients with moderate to severe AD who were receiving stable, concomitant donepezil treatment [9]. Assuming that these effect sizes are the true treatment effects for extended-release memantine, a sample size of 300 patients per group was needed to provide a power of at least 83 % to detect these effect sizes (or greater) simultaneously at a significance level of 0.05 (two-sided).

The safety population consisted of all randomized patients who received at least one dose of double-blind study medication. The intent-to-treat (ITT) population consisted of all patients from the safety population who completed at least one post-baseline primary efficacy assessment (SIB or CIBIC-Plus). Primary efficacy analyses were based on the ITT population and the LOCF approach for imputation of missing values. The changes from baseline to week 24 (LOCF) in SIB scores were analyzed (by Forest Research Institute) by means of a two-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model, with treatment group and study center as factors and baseline as a covariate; the week 24 (LOCF) CIBIC-Plus scores were analyzed using a Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test with modified ridit scores, controlling for study center. Secondary (ADCS–ADL19) and additional efficacy parameters (NPI, VFT) were analyzed using the ANCOVA model. Additional analyses for all outcomes included the use of observed cases (OC) in the same models. For the two co-primary parameters, a sensitivity analysis using a mixed-effects model for repeated measures (MMRM) based on OC data was also performed, using treatment, visit, and treatment-by-visit interaction as factors and baseline score (SIB or Clinician’s Interview-Based Impression of Severity) as a covariate. For all statistical analyses, the significance level was 0.05 (two-sided). No interim analyses were planned or performed.

The number and percentage of patients with treatment-emergent adverse events in each treatment group were tabulated by system organ class, preferred term, severity, and relationship to the study drug. The number and percentage of patients with any treatment-emergent adverse events, serious adverse events, and adverse events leading to premature discontinuations were presented by treatment group, system organ class, and preferred term.

Results

The study was conducted at 83 medical research centers in four countries (Argentina: 23 centers, 311 patients; USA: 38 centers, 179 patients; Mexico: 11 centers, 97 patients; Chile: 11 centers, 90 patients), between June 2005 and October 2007.

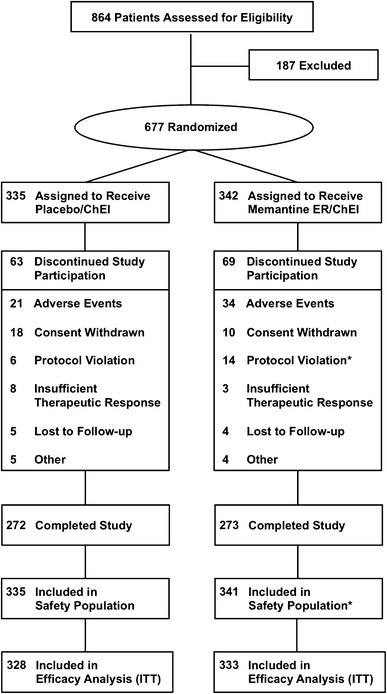

A total of 677 participants were randomized (1:1) to receive either placebo (n = 335) or extended-release memantine (n = 342), with 272 (81.2 %) and 273 (79.8 %) participants completing the trial, respectively (Fig. 1). By the end of the study, the mean daily dose of extended-release memantine was 27.0 mg, with a total of 314 patients (92.1 %) receiving the maximum daily dose of 28 mg. The treatment groups were well matched for demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline (Table 1). All participants were in the range of moderate-to-severe AD (MMSE range of 3–14 at screening and 3–17 at baseline; mean Functional Assessment Staging [23] between 6a and 6b at screening). The majority of participants were of Hispanic origin (placebo 69.6 %, memantine 68.3 %).

Fig. 1.

Study flow. *One patient with a protocol violation was excluded prior to receiving study medication and was not included in the safety population. ChEI cholinesterase inhibitor, ER extended-release formulation (28 mg), ITT intent-to-treat population

Table 1.

Summary of baseline patient characteristics (safety population)

| Parameter | Placebo (n = 335) | Memantine ER (n = 341) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yearsa | 76.8 ± 7.8 | 76.2 ± 8.4 |

| Women, n (%) | 243 (72.5) | 244 (71.6) |

| White, n (%) | 312 (93.1) | 324 (95.0) |

| Hispanic, n (%) | 233 (69.6) | 233 (68.3) |

| Weight, kga | 64.7 ± 13.3 | 65.1 ± 12.8 |

| Education, yearsa | 8.9 ± 4.5 | 8.8 ± 4.5 |

| MMSE scorea | 10.6 ± 2.9 | 10.9 ± 2.9 |

| MMSE range | 3–15 | 3–17 |

| mHIS (at screening)a | 1.1 ± 0.98 | 1.1 ± 0.92 |

| FAST score (at screening)a,b | 1.3 ± 2.2 | 1.2 ± 2.1 |

| Concomitant ChEI treatment at baseline | ||

| Donepezil | ||

| Patients, n (%) | 228 (68.1) | 236 (69.2) |

| Treatment duration, monthsa | 17.5 ± 18.4 | 16.9 ± 18.3 |

| Mean dose, mg/daya | 7.8 ± 2.6 | 8.0 ± 2.8 |

| Galantamine | ||

| Patients, n (%) | 68 (20.3) | 72 (21.1) |

| Treatment duration, monthsa | 14.2 ± 12.2 | 16.1 ± 18.2 |

| Mean dose, mg/daya | 13.5 ± 5.4 | 13.5 ± 5.7 |

| Rivastigmine | ||

| Patients, n (%) | 41 (12.2) | 32 (9.4) |

| Treatment duration, monthsa | 16.8 ± 18.8 | 17.4 ± 16.9 |

| Mean dose, mg/daya | 6.8 ± 2.9 | 6.8 ± 2.6 |

aMean ± standard deviation

bFAST was administered at screening only; stages 1, 2, 3, … 7f were assigned numerical values of −4, −3, −2, … 11

ChEI cholinesterase inhibitor, ER extended-release formulation (28 mg), FAST Functional Assessment Staging, MMSE Mini-Mental State Examination, mHIS modified Hachinski Ischemia Score

Co-primary Efficacy Parameters

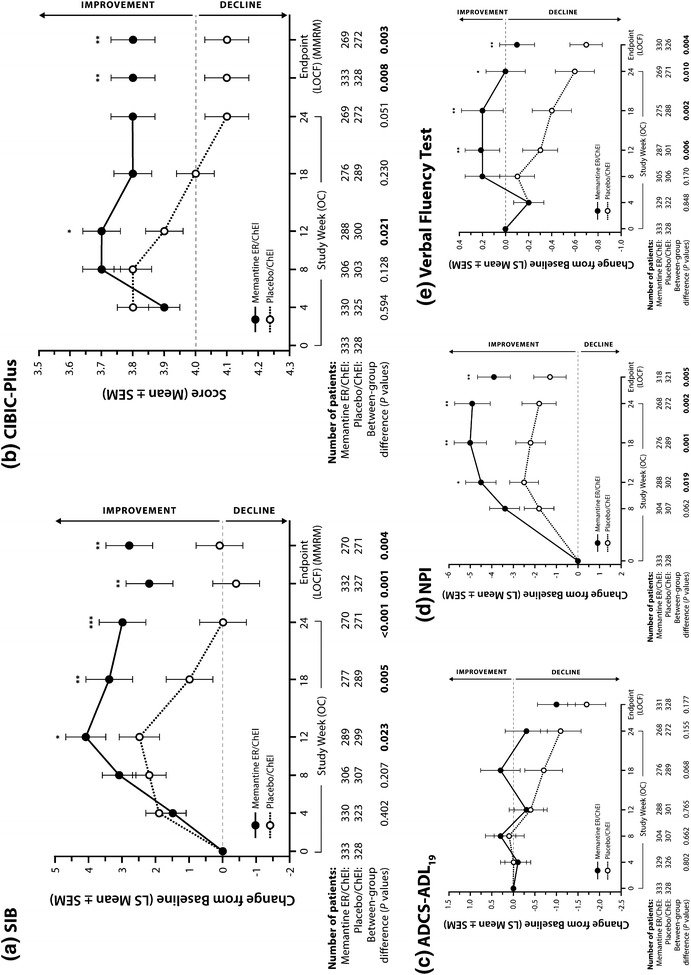

At week 24, the extended-release memantine group significantly outperformed the placebo group on both the SIB (Fig. 2a; Table 2) and the CIBIC-Plus (Fig. 2b; Table 2). In addition, the memantine group significantly outperformed the placebo group at week 12 on the SIB (OC) and CIBIC-Plus (OC, LOCF) and at week 18 on the SIB (OC, LOCF) (OC data presented in Fig. 2a, b).

Fig. 2.

Efficacy outcomes. In ChEI-treated patients with moderate to severe AD, treatment with memantine ER provided significant benefits on primary measures of cognition [(a) SIB] and global status [(b) CIBIC-Plus], as well as secondary measures of behavior [(d) NPI] and verbal fluency (e). No statistically significant differences were observed on the measure of function [(c) ADCS–ADL19]. AD Alzheimer’s disease, ADCS–ADL 19 19-item Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study–Activities of Daily Living, ChEI cholinesterase inhibitor, CIBIC-Plus Clinician’s Interview-Based Impression of Change Plus Caregiver Input, ER extended-release formulation (28 mg), LOCF last observation carried forward, LS least squares, MMRM mixed-effects model for repeated measures, NPI Neuropsychiatric Inventory, OC observed cases, SEM standard error of the mean, SIB Severe Impairment Battery. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; p-values indicating statistically significant differences between groups are shown in bold type

Table 2.

Mean efficacy assessments at baseline and endpoint (week 24, LOCF; ITT population)

| Outcome measure | N | Baselinea | Endpoint change from baselinea | LSMD [95 % CI] | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIB | |||||

| Memantine ER | 332 | 76.8 ± 17.5 | 2.7 ± 11.2 | 2.6 [1.0, 4.2] | 0.001 |

| Placebo | 327 | 75.2 ± 19.3 | 0.3 ± 11.5 | ||

| CIBIC-Plusb | |||||

| Memantine ER | 333 | 4.5 ± 0.87 | 3.8 ± 1.2b | N/A | 0.008 |

| Placebo | 328 | 4.5 ± 0.82 | 4.1 ± 1.2b | ||

| ADCS–ADL19 | |||||

| Memantine ER | 331 | 33.1 ± 11.1 | −0.7 ± 6.9 | 0.7 [−0.3, 1.8] | 0.177 |

| Placebo | 328 | 32.8 ± 11.0 | −1.3 ± 7.7 | ||

| NPI | |||||

| Memantine ER | 318 | 17.2 ± 15.6 | −4.3 ± 14.6 | −2.7 [−4.5, −0.8] | 0.005 |

| Placebo | 321 | 16.5 ± 15.4 | −1.6 ± 12.7 | ||

| VFT | |||||

| Memantine ER | 330 | 5.8 ± 3.8 | 0.3 ± 2.8 | 0.5 [0.2, 0.9] | 0.004 |

| Placebo | 326 | 5.7 ± 3.7 | −0.3 ± 2.5 | ||

aMean ± standard deviation

bCIBIC-Plus is a categorical measure of change. Values shown for baseline are the Clinician’s Interview-Based Impression of Severity; endpoint values are final CIBIC-Plus scores. p-Value is from a Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test

ADCS–ADL 19 19-item Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study–Activities of Daily Living, CI confidence interval, CIBIC-Plus Clinician’s Interview-Based Impression of Change Plus Caregiver Input, ER extended-release formulation (28 mg), ITT intent-to-treat, LOCF last observation carried forward, LSMD least squares mean difference, N/A not applicable, NPI Neuropsychiatric Inventory, SIB Severe Impairment Battery, VFT verbal fluency test

Secondary and Additional Efficacy Assessments

At week 24, there were no significant differences between the treatment groups on the ADCS–ADL19 (Fig. 2c; Table 2), but the extended-release memantine group significantly outperformed the placebo group on the NPI (Fig. 2d; Table 2) and on the VFT (Fig. 2e; Table 2). In addition, for both the NPI and the VFT, memantine was associated with significant benefits over placebo at weeks 12 and 18 (OC data presented in Fig. 2d, e).

Safety and Tolerability

A total of 21/335 patients (6.3 %) in the placebo group and 34/341 patients (9.9 %) in the extended-release memantine group discontinued the trial because of an adverse event (Fig. 1). The most frequent reasons for discontinuation due to an adverse event were dizziness [placebo 0 (0 %), memantine 5 (1.5 %)] and agitation [placebo 1 (0.3 %), memantine 3 (0.9 %)]. A total of 214 placebo-treated (63.9 %) and 214 memantine-treated patients (62.8 %) reported treatment-emergent adverse events, with both groups reporting, in general, a similar adverse-event profile (Table 3).

Table 3.

Treatment-emergent adverse events (safety population)

| Adverse event | Placebo (n = 335) | Memantine ER (n = 341) |

|---|---|---|

| Any TEAE | 214 (63.9) | 214 (62.8) |

| Fall | 26 (7.8) | 19 (5.6) |

| Urinary tract infection | 24 (7.2) | 19 (5.6) |

| Headache | 17 (5.1) | 19 (5.6) |

| Diarrhea | 13 (3.9) | 17 (5.0) |

| Dizziness | 5 (1.5) | 16 (4.7) |

| Influenza | 9 (2.7) | 15 (4.4) |

| Insomnia | 16 (4.8) | 14 (4.1) |

| Agitation | 15 (4.5) | 14 (4.1) |

| Hypertension | 8 (2.4) | 13 (3.8) |

| Anxiety | 9 (2.7) | 12 (3.5) |

| Depression | 5 (1.5) | 11 (3.2) |

| Weight increased | 3 (0.9) | 11 (3.2) |

| Constipation | 4 (1.2) | 10 (2.9) |

| Somnolence | 4 (1.2) | 10 (2.9) |

| Back pain | 2 (0.6) | 9 (2.6) |

| Aggression | 5 (1.5) | 8 (2.3) |

| Hypotension | 5 (1.5) | 7 (2.1) |

| Vomiting | 4 (1.2) | 7 (2.1) |

| Abdominal pain | 2 (0.6) | 7 (2.1) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 10 (3.0) | 6 (1.8) |

| Confusional state | 7 (2.1) | 6 (1.8) |

| Weight decreased | 11 (3.3) | 5 (1.5) |

| Nausea | 7 (2.1) | 5 (1.5) |

| Irritability | 8 (2.4) | 4 (1.2) |

| Cough | 8 (2.4) | 3 (0.9) |

Data [n (%)] include all adverse events experienced by at least 2.0 % of patients in either group (safety population). Adverse events that were experienced at twice or more the rate in one group compared with the other are indicated by bold type

ER extended-release formulation (28 mg), TEAE treatment-emergent adverse event

Serious adverse events were experienced by 21 placebo-treated (6.3 %) and 28 memantine-treated patients (8.2 %), with fall [placebo 5 (1.5 %), memantine 2 (0.6 %)] and urinary tract infection [placebo 3 (0.9 %), memantine 2 (0.6 %)] being the most frequent. Pneumonia, cerebrovascular accident, and syncope were the only other serious adverse events experienced by more than one patient in the memantine-treated group [placebo 0, memantine 2 (0.6 %), for each]. Nine patients out of 676 died during the trial: 5 (1.5 %) in the placebo group and 4 (1.2 %) in the memantine group. No death was judged to be related or possibly related to treatment in the memantine-treated group.

A greater than twofold difference in the rate of potentially clinically significant (PCS) laboratory values was observed for low hemoglobin [placebo 3 (1.1 %), memantine 7 (2.4 %)] and high eosinophil levels [placebo 4 (1.4 %), memantine 1 (0.3 %)]; the rates of other PCS laboratory values were similar between the treatment groups.

Discussion

This study, similar in design to three previous memantine trials in moderate to severe AD [8, 9, 24], including a trial in patients on stable cholinesterase inhibitor therapy (donepezil) [9], demonstrated a significant advantage of extended-release memantine (28 mg) over placebo on multiple outcome measures. Patients treated with extended-release memantine performed significantly better than placebo-treated patients on the co-primary outcome measures of cognition and global clinical status, as well as on the measures of behavior and verbal fluency. In contrast to two of the previous studies in patients with moderate to severe AD [8, 9], no significant difference between treatment groups was observed on the ADCS–ADL19. In the current study, patients in both groups remained stable or demonstrated a slight decline after 24 weeks, whereas in the other two studies, placebo-treated patients declined by an average of 5.9 points [8] and 3.3 points [9], respectively (OC analyses). In the other previous trial, which investigated memantine monotherapy, placebo-treated patients declined by an average of 2.3 points, and no differences between groups were observed [24].

It should be noted that our study consisted of a large, mostly non-US Hispanic population (69 %), which has not been extensively represented in clinical trials in AD [13]. Although other ADL measures have been successfully validated in Hispanic patients [25–27], to our knowledge the only Spanish validation of the ADCS–ADL scale involves the 23-item instrument in Spanish-speaking Americans [28], and the possibility exists that some items from the 19-item scale may be less applicable to patients with moderate to severe AD from Central or South America.

Also, we find it noteworthy that extended-release memantine treatment demonstrated significant benefits on behavioral symptoms (NPI), in spite of a robust placebo response (Fig. 2d). A protocol-specified analysis of individual NPI items (not reported here) showed a significant advantage for memantine over placebo on agitation/aggression, irritability/lability, nighttime behavior, and delusions, which is consistent with previous studies [10, 29–31]. Since behavioral symptoms are associated with increased severity of dementia, functional decline, probability of institutionalization, patient care costs, and caregiver burden [32–34], an improvement in their management should translate into a tangible, clinically important benefit.

Memantine treatment in this trial was also associated with significant improvements in semantic fluency [22]. The semantic fluency task requires attention, information retrieval, and intact semantic associations [35–37], and is strongly dependent upon the hippocampus and related structures in the left mediotemporal lobe [38, 39]. In patients with AD, semantic fluency positively correlates with measures of memory [40] and the ability to perform everyday activities [35].

This study was unique for a number of reasons. First, we examined the efficacy of a higher-dose, extended-release formulation of memantine. Although the currently approved immediate-release formulation in principle has a sufficient half-life to enable once-daily dosing (60–80 h) [12, 41], the extended-release formulation allows for a higher target dose [48 % higher steady-state maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) and 33 % higher area under the plasma concentration–time curve from time 0 to 24 h (AUC0–24), compared with twice-daily 10-mg dosing of immediate-release memantine; data on file, Forest Research Institute] and provides a slow release, which could contribute to reducing the rate and severity of adverse reactions resulting from rapid drug absorption. Patients in the extended-release memantine group experienced very few adverse events (Table 3), which were consistent but generally lower in frequency compared with those seen in similar, previous studies of immediate-release memantine in patients with moderate to severe AD [8, 9, 11, 12, 24]; however, a different study design would be required to properly assess differences between the two formulations. Secondly, this trial allowed concomitant treatment with any of the three currently approved cholinesterase inhibitors; in the only other randomized trial of memantine in patients with moderate to severe AD taking cholinesterase inhibitors, all patients were taking donepezil [9]. The inclusion of a measure of verbal fluency is also unique; to our knowledge, only one other placebo-controlled trial of an approved anti-dementia drug has used verbal fluency as an outcome measure in patients with AD. In that study, donepezil did not improve phonemic fluency in patients with mild-to-moderate dementia [42]. Finally, this study was performed in a population that was predominantly Hispanic, a population that has traditionally been under-represented in trials of anti-dementia drugs [13].

A notable limitation of this study was the absence of an active control arm containing patients treated with standard, immediate-release memantine. Consequently, the new 28-mg extended-release formulation cannot be directly compared with standard dosing in terms of efficacy, adverse events, or adherence to drug. In addition, in order to limit the confounding effects of multiple comorbidities and the exposure of frail individuals to an inactive placebo treatment, this study recruited outpatients who met a set of entry criteria comparable to those typically found in clinical trials of anti-dementia therapies, but which may not be fully representative of an actual out-of-trial population. We recommend that each of these parameters be addressed in future trials. Furthermore, a number of post hoc analyses could provide interesting and useful information, including comparisons between Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients and analyses by the type of cholinesterase inhibitor used. The primary statistical analysis in this study utilized the LOCF approach (an FDA standard at the time of the trial), in which imputation of missing scores is performed using the most recent available values. Since this approach has the potential to create a bias when used in trials of conditions associated with steady clinical decline, such as AD [43], supportive analyses using OC and MMRM were also performed, and showed nearly identical results (Fig. 2).

Conclusion

This trial of a novel, 28-mg, extended-release memantine formulation supports the existing body of evidence that indicates memantine provides cognitive, global, and behavioral benefits in patients with moderate to severe AD treated with a cholinesterase inhibitor, while the new formulation allows for an increased daily dose and simplified delivery regimen. Studies that directly compare the new extended-release formulation with standard dosing should be conducted to further assess efficacy, drug adherence, and caregiver burden.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Forest Laboratories, Inc. sponsored this trial and provided financial, material, and statistical support. The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Michael Tocco from Forest Research Institute for manuscript coordination and editorial assistance, and TorreyBeth Volkman from Prescott Medical Communications Group for assistance in preparation of the Methods section, editorial assistance, and formatting. (For a full list of co-investigators and their affiliations, see the Electronic Supplementary Material.)

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Grossberg has received consulting fees from Avanir Pharmaceuticals, Baxter Bioscience, Forest Laboratories, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, and Otsuka Pharmaceutical; his department also receives research funds from Abbott Laboratories, Baxter, Forest, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, and Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, as well as data safety monitoring committee fees from Abbott, Merck, and Schering-Plough. His laboratory receives NIH funding for a study unrelated to the current study.

Dr. Manes works for an institution that received consulting compensation from Forest Laboratories for its participation in this study.

Dr. Allegri works for an institution that received consulting compensation from Forest Laboratories for its participation in this study, and that also receives research funds from Roche, Forest, and Ebewe Pharmaceuticals.

Dr. Gutiérrez-Robledo previously worked for an institution that received consulting compensation from Forest Laboratories for its participation in this study, has served on the scientific advisory board for Pfizer, is funded by a CONACYT grant, and receives institutional support from the Instituto Nacional de Geriatría.

Dr. Gloger works for an institution that received consulting compensation from Forest Laboratories for its participation in this study, and he and/or his institution have received research funds from Wyeth Laboratories, Pfizer, Schering-Plough, Otsuka, Sanofi, BIAL Group, Eli Lilly, and Roche.

Drs. Graham, Perhach, Xie, and Jia are employed by Forest Research Institute.

Drs. Miller and Pejović are employed by Prescott Medical Communications Group, a paid consultant to Forest Laboratories, Inc.

References

- 1.Langa KM, Chernew ME, Kabeto MU, Herzog AR, Ofstedal MB, Willis RJ, et al. National estimates of the quantity and cost of informal caregiving for the elderly with dementia. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(11):770–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.10123.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mohamed S, Rosenheck R, Lyketsos CG, Schneider LS. Caregiver burden in Alzheimer disease: cross-sectional and longitudinal patient correlates. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(10):917–927. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181d5745d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herrmann N, Tam DY, Balshaw R, Sambrook R, Lesnikova N, Lanctot KL. The relation between disease severity and cost of caring for patients with Alzheimer disease in Canada. Can J Psychiatry. 2010;55(12):768–775. doi: 10.1177/070674371005501204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Small GW, McDonnell DD, Brooks RL, Papadopoulos G. The impact of symptom severity on the cost of Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(2):321–327. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hughes CM. Medication non-adherence in the elderly: how big is the problem? Drugs Aging. 2004;21(12):793–811. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200421120-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(5):487–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Small G, Dubois B. A review of compliance to treatment in Alzheimer’s disease: potential benefits of a transdermal patch. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23(11):2705–2713. doi: 10.1185/030079907X233403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reisberg B, Doody R, Stöffler A, Schmitt F, Ferris S, Möbius HJ. Memantine in moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(14):1333–1341. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tariot PN, Farlow MR, Grossberg GT, Graham SM, McDonald S, Gergel I. Memantine treatment in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer disease already receiving donepezil: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291(3):317–324. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.3.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McShane R, Areosa Sastre A, Minakaran N. Memantine for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006(2):CD003154. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Farlow MR, Graham SM, Alva G. Memantine for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: tolerability and safety data from clinical trials. Drug Saf. 2008;31(7):577–585. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200831070-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Namenda® U.S. Prescribing Information. St. Louis: Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2007.

- 13.Lopez OL, Mackell JA, Sun Y, Kassalow LM, Xu Y, McRae T, et al. Effectiveness and safety of donepezil in Hispanic patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a 12-week open-label study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(11):1350–1358. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31515-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Psychiatric Association Task Force on DSM-IV . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS–ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/WNL.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Panisset M, Roudier M, Saxton J, Boller F. Severe impairment battery. A neuropsychological test for severely demented patients. Arch Neurol. 1994;51(1):41–45. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1994.00540130067012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schneider LS, Olin JT, Doody RS, Clark CM, Morris JC, Reisberg B, et al. Validity and reliability of the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-Clinical Global Impression of Change. The Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1997;11(Suppl 2):S22–S32. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199700112-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galasko D, Bennett D, Sano M, Ernesto C, Thomas R, Grundman M, et al. An inventory to assess activities of daily living for clinical trials in Alzheimer’s disease. The Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1997;11(Suppl 2):S33–S39. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199700112-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galasko D, Schmitt F, Thomas R, Jin S, Bennett D. Detailed assessment of activities of daily living in moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2005;11(4):446–453. doi: 10.1017/s1355617705050502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44(12):2308–2314. doi: 10.1212/WNL.44.12.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strauss E, Sherman EMS, Spreen O. A compendium of neuropsychological tests: administration, norms, and commentary. 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reisberg B. Functional assessment staging (FAST) Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24(4):653–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Dyck CH, Tariot PN, Meyers B, Malca Resnick E. A 24-week randomized, controlled trial of memantine in patients with moderate-to-severe Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2007;21(2):136–143. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318065c495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gleichgerrcht E, Camino J, Roca M, Torralva T, Manes F. Assessment of functional impairment in dementia with the Spanish version of the Activities of Daily Living Questionnaire. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2009;28(4):380–388. doi: 10.1159/000254495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olazaran J, Mouronte P, Bermejo F. Clinical validity of two scales of instrumental activities in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurologia. 2005;20(8):395–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanchez-Benavides G, Manero RM, Quinones-Ubeda S, de Sola S, Quintana M, Pena-Casanova J. Spanish version of the Bayer Activities of Daily Living scale in mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer disease: discriminant and concurrent validity. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2009;27(6):572–578. doi: 10.1159/000228259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sano M, Egelko S, Jin S, Cummings J, Clark CM, Pawluczyk S, et al. Spanish instrument protocol: new treatment efficacy instruments for Spanish-speaking patients in Alzheimer disease clinical trials. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20(4):232–241. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000213862.20108.f5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gauthier S, Wirth Y, Mobius HJ. Effects of memantine on behavioural symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease patients: an analysis of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) data of two randomised, controlled studies. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(5):459–464. doi: 10.1002/gps.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gauthier S, Loft H, Cummings J. Improvement in behavioural symptoms in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease by memantine: a pooled data analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(5):537–545. doi: 10.1002/gps.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilcock GK, Ballard CG, Cooper JA, Loft H. Memantine for agitation/aggression and psychosis in moderately severe to severe Alzheimer’s disease: a pooled analysis of 3 studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(3):341–348. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v69n0302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harwood DG, Barker WW, Ownby RL, Duara R. Relationship of behavioral and psychological symptoms to cognitive impairment and functional status in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15(5):393–400. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(200005)15:5<393::AID-GPS120>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beeri MS, Werner P, Davidson M, Noy S. The cost of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) in community dwelling Alzheimer’s disease patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17(5):403–408. doi: 10.1002/gps.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Finkel SI. Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: a current focus for clinicians, researchers, and caregivers. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(Suppl 21):3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramsden CM, Kinsella GJ, Ong B, Storey E. Performance of everyday actions in mild Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychology. 2008;22(1):17–26. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.22.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rohrer D, Salmon DP, Wixted JT, Paulsen JS. The disparate effects of Alzheimer’s disease and Huntington’s disease on semantic memory. Neuropsychology. 1999;13(3):381–388. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.13.3.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Henry JD, Crawford JR, Phillips LH. Verbal fluency performance in dementia of the Alzheimer’s type: a meta-analysis. Neuropsychologia. 2004;42(9):1212–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pihlajamaki M, Tanila H, Hanninen T, Kononen M, Laakso M, Partanen K, et al. Verbal fluency activates the left medial temporal lobe: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Ann Neurol. 2000;47(4):470–476. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(200004)47:4<470::AID-ANA10>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gourovitch ML, Kirkby BS, Goldberg TE, Weinberger DR, Gold JM, Esposito G, et al. A comparison of rCBF patterns during letter and semantic fluency. Neuropsychology. 2000;14(3):353–360. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.14.3.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cottingham ME, Hawkins KA. Verbal fluency deficits co-occur with memory deficits in geriatric patients at risk for dementia: Implications for the concept of mild cognitive impairment. Behav Neurol. 2010;22(3–4):73–79. doi: 10.1155/2010/319128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jones RW, Bayer A, Inglis F, Barker A, Phul R. Safety and tolerability of once-daily versus twice-daily memantine: a randomised, double-blind study in moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(3):258–262. doi: 10.1002/gps.1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Greenberg SM, Tennis MK, Brown LB, Gomez-Isla T, Hayden DL, Schoenfeld DA, et al. Donepezil therapy in clinical practice: a randomized crossover study. Arch Neurol. 2000;57(1):94–99. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mallinckrodt CH, Sanger TM, Dube S, DeBrota DJ, Molenberghs G, Carroll RJ, et al. Assessing and interpreting treatment effects in longitudinal clinical trials with missing data. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(8):754–760. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01867-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.