Abstract

Introduction

Dose escalation with tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-blockers is poorly characterized in pharmacy benefit management (PBM) settings.

Methods

This retrospective study used integrated pharmacy and medical claims from the PBM Medco to characterize dose escalation among rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients treated with etanercept and adalimumab. Data from adults with RA with pharmacy claims for etanercept or adalimumab between 1/1/2007 and 12/31/2009 and continuous enrollment for ≥6 months before and ≥12 months after first (index) pharmacy claim were analyzed. “New” patients had no claim for TNF-blocker in the 6 months prior to receipt of their index TNF-blocker; otherwise, they were classified as “continuing” patients. Endpoints included 12-month persistence and duration on index medication and dose escalation. Dose escalation (allowed per adalimumab label but not for etanercept) in patients’ persistent ≥12 months was estimated using five methods: (1) average weekly dose ≥110% of recommended label dose; (2) average subsequent dose ≥130% of starting dose; (3) last dose ≥110% of starting dose; (4) ≥2 consecutive instances of dose ≥130% of starting dose; and (5) any instance where dose increase connoted an additional syringe/vial use.

Results

Data from 1,260 patients on etanercept and 852 patients on adalimumab were analyzed; 45.3 and 45.9% of new patients on etanercept and adalimumab, respectively, and 60.5 and 60.8% of continuing patients had ≥12 months persistence on index medication. Across all five methods used to estimate dose escalation, patients receiving etanercept had significantly lower rates of dose escalation (P < 0.001) than patients receiving adalimumab. For new patients, rates of dose escalation were 0.4–1.2% for etanercept and 8.3–14.1% for adalimumab. For continuing patients, rates ranged from 1.1 to 2.9% for etanercept and 7.0–28.3% for adalimumab.

Conclusions

New and continuing patients from this PBM database on etanercept had significantly lower rates of dose escalation than patients on adalimumab.

Keywords: Adalimumab, Dose escalation, Etanercept, Pharmacy benefit management, Rheumatoid arthritis

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, inflammatory, autoimmune disease that manifests primarily in the synovial tissues, with symptoms of pain, stiffness, swelling, and progressive joint destruction. Since 2002, treatment recommendations for RA have suggested an aggressive approach to inhibit the progression of joint damage and other complications that may develop soon after diagnosis [1–3]. This aggressive approach includes initiation of standard disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and biologic agents. Biologic agents target specific mediators of RA, including the inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor (TNF) [4]. Etanercept is a TNF receptor:Fc fusion protein and adalimumab is a recombinant human monoclonal antibody against TNF.

The most commonly prescribed self-injected TNF-blockers currently used in the treatment of moderate to severe RA are etanercept and adalimumab [5]. The United States (US) Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-recommended starting dose of etanercept for the treatment of moderate to severe RA is 50 mg weekly administered as a subcutaneous (SC) injection [6]. The recommended dose of adalimumab is 40 mg every other week (EOW) administered SC, which can be increased to 40 mg weekly for patients not on concomitant methotrexate [7].

Data from observational and clinical studies have shown that some patients require an upward dose adjustment or shortened dose interval to achieve or maintain a clinical response to some TNF-blockers [8–15]. Information on dosing patterns used in the real-world clinical setting would be useful to estimate the cost of treatment for RA with these agents to assist in formulary and reimbursement decision-making [16].

Analyses of dose escalation using data from commercial health plans estimated that rates of TNF-blocker dose escalation range from 1 to 18% for patients on etanercept and 8–33% for patients on adalimumab [10–12, 17–22]. In the US, Pharmacy Benefit Management (PBM) companies act as third-party administrators to manage the cost and utilization of prescription drugs and benefits. The wide variety of utilization management strategies and tools applied by the PBM may impact the utilization and dosing patterns of TNF-blockers. The objective of this study was to estimate persistence, utilization patterns, and dose escalation rates of etanercept and adalimumab among patients with RA in a PBM setting, including patients newly initiating treatment and those continuing on therapy.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting

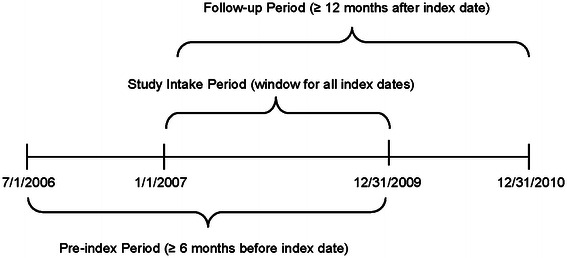

This retrospective analysis utilized administrative claims data from Medco, a large, geographically diverse PBM that covers over 60 million patients in the US, supporting commercial health plans, employers, and federal and state governments. An integrated database of both medical and pharmacy claims was available for 10 million patients, and data from July 1, 2006 to December 31, 2010 were used in the analysis (Fig. 1). (Medco was acquired by Express Scripts, Inc. in 2012, after the study period.) The index date was the date of the first observed prescription for the index medication (etanercept or adalimumab) during the study period. The pre-index period was the 6 months prior to the index date and the follow-up period comprised a minimum of 12 months of continuous enrollment following the index date. The study intake period was from January 1, 2007 through to December 31, 2009.

Fig. 1.

Study schema. Dates for pre-index, study intake, and follow-up periods are shown

Eligibility Criteria

Patients were eligible for inclusion in the study if they were aged 18–64 years; diagnosed with RA (International Classification of Diseases—Clinical Modification Code, 9th Revision [ICD-9] code 714.0x) in the pre-index period; prescribed etanercept or adalimumab during the study intake period; and continuously enrolled to receive pharmacy benefits for at least 6 months prior to and at least 12 months following their index date. Patients were excluded from the analysis if they had a diagnosis of psoriasis (ICD-9 code 696.1), psoriatic arthritis (ICD-9 code 696.0), juvenile idiopathic arthritis (ICD-9 code 714.3), Crohn’s disease (ICD-9 code 555.x), ulcerative colitis (ICD-9 code 556.x), ankylosing spondylitis (ICD-9 code 720.0), multiple sclerosis (ICD-9 code 340.xx), or lupus (ICD-9 code 710.0x) during the pre-index period, or a diagnosis of HIV or cancer during the pre-index period or follow-up period. Patients with in-office injection claims (J-codes) during follow-up were excluded because it was not possible to accurately estimate the quantity of medication administered from the data that were available. Patients were categorized as new to therapy if they did not have any TNF-blocker claims during the pre-index period and as continuing therapy if they had a TNF-blocker claim during the pre-index period.

Outcomes

Duration and persistence on index medication as well as dose escalation rates of etanercept and adalimumab were evaluated. Duration of index therapy was defined as the time from the index dose through the date of fill for the last prescription in the follow-up period regardless of gaps in the index therapy. Persistence was measured as the number of days from the index date to the first occurrence of either a gap in index therapy of at least 60 days or a claim for another biologic. Gaps in therapy were identified as the time between the run-out of a fill until the fill date of the next claim. Patients with no gaps in therapy of at least 60 days and no switches throughout their entire follow-up were considered to have a length of persistence equal to that of their follow-up period.

Dose escalation was evaluated in patients who were persistent on their index TNF-blocker for at least 12 months and who started at or above the labeled dose. Dose escalation was defined using five previously published methods: (1) average weekly dose ≥110% of the minimum FDA-recommended label dose [11, 17]; (2) average subsequent dose ≥130% of the starting dose [11]; (3) last dose ≥110% of the starting dose [20]; (4) two or more consecutive instances of a dose ≥130% of the starting dose [11]; or (5) any instance of a syringe or vial increase (change in dose from 50 to 75 mg per week or from 50 to 100 mg per week for etanercept; change from 40 mg EOW to 40 mg per week for adalimumab) [23].

The average weekly dose during the 12 months after the index date and the total dispensed quantity within those 12 months was calculated for patients who were persistent on index medication for at least 12 months. Costs were calculated using the October 2012 Wholesale Acquisition Costs (WAC) for these drugs [24].

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Statistical Considerations

Descriptive analyses of demographic and clinical characteristics, dose escalation metrics, and persistence patterns were examined separately for patients in the etanercept and adalimumab cohorts and were stratified by new and continuing patients. Chi square tests were used to evaluate the statistical significance of differences for categorical variables; t tests and analysis of variance were used for normally distributed continuous variables. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patients

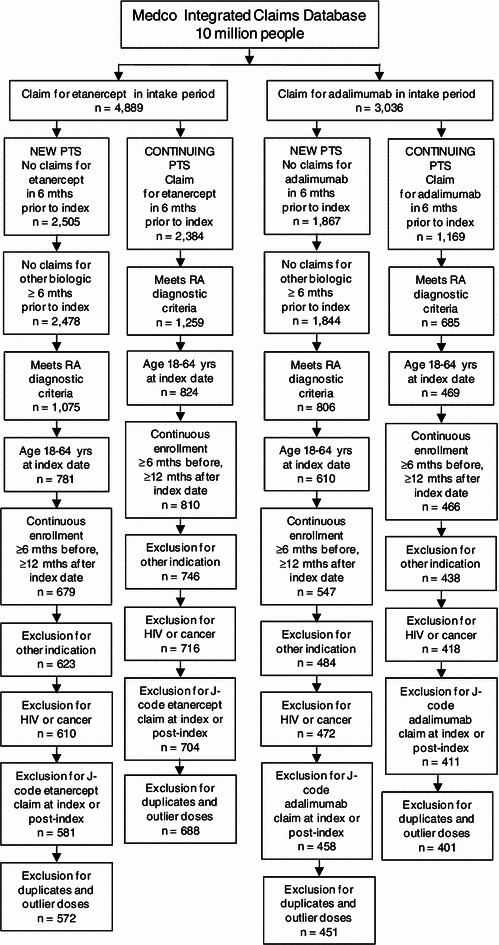

A total of 2,112 RA patients, including 1,023 new patients (572 etanercept; 451 adalimumab) and 1,089 continuing patients (688 etanercept; 401 adalimumab), met the eligibility criteria and were included in the analysis (Fig. 2). Demographic and clinical characteristics were similar between patients receiving etanercept and those receiving adalimumab (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Patient selection. Attrition of patients per eligibility criteria for new and continuing patients on etanercept and adalimumab is shown

Table 1.

Demographics and comorbidity status of patients with rheumatoid arthritis who were new or continuing etanercept or adalimumab therapy

| New patients N = 1,023 | Continuing patients N = 1,089 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETN n = 572 | ADA n = 451 | ETN n = 688 | ADA n = 401 | |

| Age group (years), n (%) | ||||

| 18–25 | 12 (2.1) | 6 (1.3) | 11 (1.6) | 2 (0.5) |

| 26–35 | 44 (7.7) | 28 (6.2) | 25 (3.6) | 16 (4.0) |

| 36–45 | 106 (18.5) | 84 (18.6) | 85 (12.4) | 59 (14.7) |

| 46–55 | 210 (36.7) | 169 (37.5) | 256 (37.2) | 119 (29.7) |

| 56–64 | 200 (35.0) | 164 (36.4) | 311 (45.2) | 205 (51.1) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 461 (80.6) | 366 (81.2) | 546 (79.4) | 310 (77.3) |

| Male | 110 (19.2) | 83 (18.4) | 142 (20.6) | 91 (22.7) |

| Missing | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.4) | 0 | 0 |

| Region, n (%) | ||||

| Northeast | 64 (11.2) | 70 (15.5) | 96 (14.0) | 68 (17.0) |

| Midwest | 144 (25.2) | 116 (25.7) | 154 (22.4) | 106 (26.4) |

| South | 192 (33.6) | 169 (37.5) | 232 (33.7) | 140 (34.9) |

| West | 172 (30.1) | 95 (21.1) | 206 (29.9) | 87 (21.7) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 0 |

| Quan-Charlson index, mean score [SD] | 1.4 [0.7] | 1.5 [0.9] | 1.3 [0.8] | 1.3 [0.7] |

| Received methotrexate in pre-index period, n (%) | 361 (63.1) | 298 (66.1) | 344 (50.0) | 234 (58.4) |

ADA adalimumab, ETN etanercept, SD standard deviation

Duration and Persistence on TNF-Blocker Therapy

Mean [standard deviation, SD] duration of index therapy was longer for continuing patients (31.2 [17.1] months) than for new patients (18.0 [13.7] months) and was similar between treatments for new and continuing patients (Table 2). Similarly, a greater proportion of continuing patients had at least 12 months on index therapy (77.1 vs 58.1% for new patients).

Table 2.

Duration and persistence on index medication among rheumatoid arthritis patients

| New patients N = 1,023 | Continuing patients N = 1,089 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETN n = 572 | ADA n = 451 | ETN n = 688 | ADA n = 401 | |

| Mean duration of therapy, months [SD] | 18.5 [14.0] | 17.3 [13.3] | 31.9 [17.0] | 30.1 [17.2] |

| Patients with ≥12 months duration, n (%) | 337 (58.9) | 257 (57.0) | 539 (78.3) | 301 (75.1) |

| Mean persistence on therapy, months [SD] | 15.0 [12.7] | 15.0 [12.5] | 23.4 [17.7] | 23.0 [17.4] |

| Patients with ≥12 months persistence, n (%) | 259 (45.3) | 207 (45.9) | 416 (60.5) | 244 (60.8) |

ADA adalimumab, ETN etanercept, SD standard deviation

Mean persistence (SD) on index therapy was 15.0 (12.6) months in new patients and 23.3 (17.6) months in continuing patients and was similar between etanercept and adalimumab for new and continuing patients (Table 2). The proportion of patients with persistence of ≥12 months on index therapy was 45.6% in new patients and 60.6% in continuing patients.

Dose Escalation

Patients receiving etanercept had a significantly lower rate of dose escalation (range 0.4–2.9%) than those receiving adalimumab (range 7.0–28.3%) according to all five methods of calculating dose escalation for both new and continuing patients (P < 0.001) (Table 3). Rates of dose escalation were generally similar between new and continuing patients.

Table 3.

Dose escalation in rheumatoid arthritis patients who were persistent on index medication for ≥12 months, starting at or above label dose

| New patients | Continuing patients | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETN | ADA | ETN | ADA | |

| Patients persistent for ≥12 months, starting at or above recommended label dose, n | 253 | 206 | 412 | 244 |

| Dose escalation definition, n (%) | ||||

| 1. Average weekly dose ≥110% of recommended label dosea | 2 (0.8) | 29 (14.1) | 12 (2.9) | 69 (28.3) |

| 2. Average subsequent dose ≥130% of starting dosea | 1 (0.4) | 17 (8.3) | 5 (1.2) | 17 (7.0) |

| 3. Last dose ≥110% of starting dosea | 2 (0.8) | 21 (10.2) | 5 (1.2) | 21 (8.6) |

| 4. Two or more consecutive instances of dose ≥130% of starting dosea | 3 (1.2) | 23 (11.2) | 11 (2.7) | 28 (11.5) |

| 5. Syringe or vial increase or shortened frequency of dosinga | 2 (0.8) | 24 (11.7) | 4 (1.0) | 38 (15.6) |

ADA adalimumab, ETN etanercept

aP < 0.001 for comparison of etanercept versus adalimumab within new and continuing patients

Total Index Drug Utilization and Costs

The average weekly dose (SD) over the study period for new patients was 49.3 (2.8) mg for etanercept and 21.5 (4.9) mg for adalimumab. The average weekly dose (SD) over the study period for continuing patients was 49.6 (6.7) mg for etanercept and 23.9 (7.4) mg for adalimumab. The mean total dispensed quantities (SD) within 12 months for new patients were 2,631 (369) mg for etanercept and 1,111 (269) mg for adalimumab. The mean total dispensed quantities (SD) for continuing patients were 2,539 (509) mg for etanercept and 1,176 (419) mg for adalimumab. The mean costs for new patients were US $27,205 for etanercept and US $28,453 for adalimumab; the mean costs for continuing patients were US $26,253 for etanercept and US $30,117 for adalimumab.

Discussion

This prescription claims study of dose escalation rates among patients with RA in a PBM setting found significantly lower rates of dose escalation for persistent patients receiving etanercept compared with persistent patients receiving adalimumab. For new patients, proportions of patients escalating from the FDA-recommended starting dose or higher ranged from 0.4 to 1.2% for etanercept and 8.3 to 14.1% for adalimumab. For continuing patients, proportions of patients escalating from the FDA-recommended starting dose or higher ranged from 1.1 to 2.9% for etanercept and 7.0 to 28.3% for adalimumab. Age, gender, comorbidity index, and regional distributions were similar between treatments, indicating that these factors did not account for differences in dose escalation. These results suggest that etanercept dosing was stable and predictable in patients receiving etanercept for moderate to severe RA, whereas 8–14% of patients receiving adalimumab experienced dose escalation from their starting dose.

Consistent with the dose escalation results, the average weekly dose over the study period and the total dispensed quantities within 12 months for the patients who were persistent on etanercept were close to the label dose of 50 mg weekly. Higher rates of dose escalation compared with etanercept were observed, and average weekly doses and total dispensed quantities of adalimumab were slightly higher than the label dose. For new patients on adalimumab, both measures were approximately 7% higher than would be expected from the label dose and for continuing patients, the average weekly dose was approximately 20% higher and total dispensed quantity within the first year was about 13% higher than the label dose.

In this study, five different methods of calculating dose escalation were used; most of these methods have been used in previously published studies [11–13, 17, 20, 21]. We used a real-world definition of dose escalation (syringe/vial increase or shortened frequency of dosing) and a method used in other studies [13, 22] (average weekly dose) to compare patterns across etanercept and adalimumab. Results were consistent across five different methods of estimating dose escalation, with etanercept having lower dose escalation rates than adalimumab.

The results presented here are consistent with those reported from studies evaluating dose escalation in commercial health plans. Observational studies from this setting have previously documented dose escalation rates of 0.8–7.9% for patients newly initiating etanercept and 8–17.1% for patients newly receiving adalimumab [10–13, 17, 20–22]. Across all studies, etanercept had the lowest rate of dose escalation in new patients. In a study that examined dose escalation in continuing patients [12], dose escalation rates were 3–4% for etanercept and 9–11% for adalimumab.

A key strength of the study was the use of real-world data from a PBM setting representative of pharmacy benefits utilization across small and large managed care organizations, employer groups, and government entities. Regardless of the method used, results were consistent across all five methods. The reason for dose escalation was not captured in this database. One reason why etanercept patients may have had lower rates of dose escalation is that the US prescribing information for etanercept only recommends the 50 mg per week dose for the treatment of moderate to severe RA. In contrast, the rate of dose escalation with adalimumab was higher and the US prescribing information includes the option to increase the dose from 40 mg EOW to 40 mg weekly in patients not receiving methotrexate. Whatever the reason, this predictability of etanercept dosing may be useful information for payors.

The primary limitation of the study was inherent to the use of an administrative claims database as a data source. Important clinical information such as severity of disease, clinical response to treatment, and the reason for dose escalation is not captured in a claims database. In addition, the accuracy of data in the claims database is dependent on the pharmacist entering the data and the physician writing the prescription. This analysis involved only etanercept and adalimumab utilization and was not comprehensive of all biologics used to treat RA. The study intake period ended in December 2009, and newer TNF-blocker therapies for RA were not included in this analysis because too few patients had received these therapies for 12 months. The amounts paid for prescriptions were not available for this analysis, so an association between dose escalation and payor cost could not be calculated. The study population was limited to patients with a minimum of 18 months of continuous enrollment and therefore, did not include patients who were disenrolled from the PBM during the study. This study may not be generalizable to other RA populations, such as Medicare, Veterans Affairs, underinsured, or uninsured patients or be representative of the total RA population in the US. Though the dataset included patients from all 50 states and was relatively well distributed geographically, it was slightly over-weighted in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and North Carolina and slightly under-weighted in California, Texas, Florida, and Illinois.

Conclusion

In conclusion, several different measures of evaluating dose escalation were applied to data from a PBM setting that represented the real-world use of the TNF-blockers etanercept and adalimumab. Each method consistently showed that RA patients on etanercept had significantly lower rates of dose escalation than patients on adalimumab for both new and continuing patients. These results support stable and predictable dosing with etanercept in patients with moderate to severe RA. Studies of real-world treatment patterns can be useful to payors performing cost analyses or to managers of inventories of TNF-blockers used for the treatment of RA.

Acknowledgments

Sponsorship and article processing charges for this study was funded by Amgen Inc. Editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Julia R. Gage, Ph.D. of Gage Medical Writing, LLC. Support for this assistance was funded by Amgen Inc. Dr. Blume is the guarantor for this article, and takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole.

Conflict of interest

Steven W. Blume is an employee of United BioSource Corp., which received funding from Amgen Inc. for this study. Chien-Chia Chuang is an employee of United BioSource Corp., which received funding from Amgen Inc. for this study. Kathleen M. Fox is a consultant for Amgen Inc. George Joseph is a former employee and shareholder of Amgen Inc. and also holds stock in Pfizer and Express Scripts Holding Company (which owns Medco). Jessy Thomas is an employee and holds stock in Amgen Inc. Shravanthi R. Gandra is an employee and holds stock in Amgen Inc.

Ethical standard

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

References

- 1.Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of non-biologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:762–784. doi: 10.1002/art.23721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rindfleisch JA, Muller D. Diagnosis and management of rheumatoid arthritis. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:1037–1047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh JA, Furst DE, Bharat A, et al. 2012 update of the 2008 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologic agents in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:625–639. doi: 10.1002/acr.21641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agarwal SK. Biologic agents in rheumatoid arthritis: an update for managed care professionals. J Manag Care Pharm. 2011;17:S14–S18. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2011.17.s9-b.S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schabert VF, Watson C, Gandra SR, Goodman S, Fox KM, Harrison DJ. Annual costs of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors using real-world data in a commercially insured population in the United States. J Med Econ. 2012;15:264–275. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2011.644645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Enbrel® (etanercept) prescribing information. Immunex Corporation, Thousand Oaks, CA. 2011.

- 7.Humira® (adalimumab) prescribing information. Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL. 2011.

- 8.Zintzaras E, Dahabreh IJ, Giannouli S, Voulgarelis M, Moutsopoulos HM. Infliximab and methotrexate in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of dosage regimens. Clin Ther. 2008;30:1939–1955. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ollendorf DA, Massarotti E, Birbara C, Burgess SM. Frequency, predictors, and economic impact of upward dose adjustment of infliximab in managed care patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Manag Care Pharm. 2005;11:383–393. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2005.11.5.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ollendorf DA, Klingman D, Hazard E, Ray S. Differences in annual medication costs and rates of dosage increase between tumor necrosis factor-antagonist therapies for rheumatoid arthritis in a managed care population. Clin Ther. 2009;31:825–835. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang X, Gu NY, Fox KM, Harrison DJ, Globe D. Comparison of methods for measuring dose escalation of the subcutaneous TNF antagonists for rheumatoid arthritis patients treated in routine clinical practice. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26:1637–1645. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2010.483127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harrison DJ, Huang X, Globe D. Dosing patterns and costs of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor use for rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2010;67:1281–1287. doi: 10.2146/ajhp090487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moots RJ, Haraoui B, Matucci-Cerinic M, et al. Differences in biologic dose-escalation, non-biologic and steroid intensification among three anti-TNF agents: evidence from clinical practice. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011;29:26–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Punzi L, Matucci Cerinic M, Cantini F, et al. Treatment patterns of anti-TNF agents in Italy: an observational study. Reumatismo. 2011;63:18–28. doi: 10.4081/reumatismo.2011.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolbink GJ, Vis M, Lems W, et al. Development of antiinfliximab antibodies and relationship to clinical response in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:711–715. doi: 10.1002/art.21671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu E, Chen L, Birnbaum H, Yang E, Cifaldi M. Cost of care for patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving TNF-antagonist therapy using claims data. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:1749–1759. doi: 10.1185/030079907X210615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonafede MM, Gandra SR, Fox KM, Wilson KL. Tumor necrosis factor blocker dose escalation among biologic naïve rheumatoid arthritis patients in commercial managed-care plans in the 2 years following therapy initiation. J Med Econ. 2012;15:635–643. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2012.667028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harley CR, Frytak JR, Tandon N. Treatment compliance and dosage administration among rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving infliximab, etanercept, or methotrexate. Am J Manag Care. 2003;9:S136–S143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilbert TD, Jr, Smith D, Ollendorf DA. Patterns of use, dosing, and economic impact of biologic agent use in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2004;5:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-5-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bullano MF, McNeeley BJ, Yu YF, et al. Comparison of costs associated with the use of etanercept, infliximab, and adalimumab for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Manag Care Interface. 2006;19:47–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu E, Chen L, Birnbaum H, Yang E, Cifaldi M. Retrospective claims data analysis of dosage adjustment patterns of TNF antagonists among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:2229–2240. doi: 10.1185/03007990802229548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gu NY, Huang X, Fox KM, Patel VD, Baumgartner SW, Chiou C-F. Claims data analysis of dosing and cost of TNF antagonist. Am J Pharm Benefits. 2010;2:351–359. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khanna D, Cyhaniuk A, Bedenbaugh A. Use of TNF-inhibitors in the US: utilisation patterns and dose escalation from a representative US rheumatoid arthritis (RA) population. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(Supple 3):197. [Google Scholar]

- 24.First DataBank. AnalySource® Online. Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC). [Accessed November 13, 2012.] Available from: http://www.fdbhealth.com/fdb-medknowledge-drug-pricing.