Abstract

Alcohol use disorders (AUDs), including alcohol abuse and dependence, and cigarette smoking are widely acknowledged and common risk factors for pneumococcal pneumonia. Reasons for these associations are likely complex but may involve an imbalance in pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines within the lung. Delineating the specific effects of alcohol, smoking, and their combination on pulmonary cytokines may help unravel mechanisms that predispose these individuals to pneumococcal pneumonia. We hypothesized that the combination of AUD and cigarette smoking would be associated with increased bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) proinflammatory cytokines and diminished anti-inflammatory cytokines, compared with either AUDs or cigarette smoking alone. Acellular BAL fluid was obtained from 20 subjects with AUDs, who were identified using a validated questionnaire, and 19 control subjects, matched on the basis of age, sex, and smoking history. Half were current cigarette smokers; baseline pulmonary function tests and chest radiographs were normal. A positive relationship between regulated and normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES) with increasing severity of alcohol dependence was observed, independent of cigarette smoking (P = 0.0001). Cigarette smoking duration was associated with higher IL-1β (P = 0.0009) but lower VEGF (P = 0.0007); cigarette smoking intensity was characterized by higher IL-1β and lower VEGF and diminished IL-12 (P = 0.0004). No synergistic effects of AUDs and cigarette smoking were observed. Collectively, our work suggests that AUDs and cigarette smoking each contribute to a proinflammatory pulmonary milieu in human subjects through independent effects on BAL RANTES and IL-1β. Furthermore, cigarette smoking additionally influences BAL IL-12 and VEGF that may be relevant to the pulmonary immune response.

Keywords: regulated and normal T cell expressed and secreted, interleukins, pneumonia, pneumococcus

severe community-acquired pneumonia is the most common cause of death from infectious diseases in developed countries, with Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae) being the pathogen responsible for most cases of bacterial pneumonia worldwide. S. pneumoniae is found routinely in the human nasopharynx as a commensal bystander; however, compromised host immunity can precipitate invasion of the lower airways with subsequent development of pneumonia and systemic spread of infection (reviewed in Refs. 6 and 64). Two common factors that can compromise host immunity are alcohol misuse and cigarette smoking. Alcohol misuse is considered to be present when an individual consumes quantities of alcohol in excess of recommended limits and occurs in a spectrum of severity (51). Alcohol abuse or alcohol dependence are found at the most severe end of the alcohol misuse spectrum and are associated with medical, legal, or social consequences by criteria established in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) (54). Together, they may be referred to as alcohol use disorders, or AUDs. AUDs may be identified using validated questionnaires in clinical settings (45, 50).

Recent epidemiological studies have specifically reported an association between severe pneumococcal infections associated with bacteremia and septic shock among individuals with AUDs in locations including Spain (22), Canada (43, 55), and Australia (26), illustrating the global health implications of this relationship. Similarly, associations between cigarette smoking and the occurrence of pneumococcal pneumonia with septic shock (22) and pneumococcal bacteremia (55) have also been reported. Notably, the risk for developing pneumococcal pneumonia has been reported to increase as the quantity of alcohol consumption increases (52); similarly, the odds of developing invasive pneumococcal disease increases with increasing pack-per-year cigarette-smoking history (38). The majority of individuals with AUDs smoke cigarettes and in fact would be categorized as having nicotine dependency (49), making this association clinically relevant. However, the effect of combined AUDs and cigarette smoking on the risk for pneumococcal infection has been relatively unexplored. Published data containing information regarding alcohol use and smoking history have been limited by their lack of basis on validated questionnaires to classify the severity of alcohol use and have been limited to patients who likely have good access to health care (38, 55).

Reasons for observed associations between AUDs, cigarette smoking, and the development of pulmonary pneumococcal disease are likely complex, but probably involve direct effects of these substances on the lung. Small clinical studies have explored the influence of these environmental factors on pulmonary cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors that are integral to proper communication between different cell types involved in the immune response. These factors may be elaborated by resident myeloid lineage cells within the lung, such as alveolar macrophages, as well as the alveolar epithelium. In human subjects with AUDs and animal models, proinflammatory cytokine activation in the lung has been reported, including enhanced induction of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1β, and IL-6 (13, 33, 39, 57). Similarly, cigarette smoke exposure has also been reported to alter alveolar macrophage release and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid values for TNF-α (34, 69), IL-1β (9), and IL-6 (34). Delineating the combined effects of alcohol and cigarette smoke exposure on TNF-α and IL-1β may be particularly useful because these cytokines are known to be integral to pneumococcal growth and dissemination (46, 63). Furthermore, a broader knowledge regarding combined alcohol and smoking effects on additional pulmonary mediators could also provide insight to the clinical relevance of more recently proposed pathogenic mechanisms underlying pneumococcal invasion, including the role for adaptive immunity (28, 36).

Our group has previously explored the effects of AUDs, with and without concomitant cigarette smoking, on components of innate immunity that may influence predisposition for pneumococcal infection (7, 10, 12). We have established a cohort of subjects with AUDs with a carefully characterized cigarette-smoking history and lung disease assessment, along with a cohort of control subjects matched on age, smoking, and sex. In these investigations, we sought to characterize the cytokine, chemokine, and growth factor milieu within the lung of those with AUDs who are either current smokers or nonsmokers. Our goals were to determine whether additive or synergistic alterations related to AUDs and cigarette smoking were present that could influence the development of pneumococcal pneumonia. We also sought to establish whether dose-response relationships between the severity of alcohol misuse and cigarette smoke exposure could be detected. We hypothesized that the combination of AUDs and cigarette smoking would be associated with an increased quantity of proinflammatory mediators in BAL, including IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, compared with either factor alone. Conversely, we postulated that the levels of anti-inflammatory mediators, including IL-10 and IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA), would be diminished.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subject screening, recruitment, and enrollment.

Subjects with AUDs were recruited between 2008 and 2010 at the Denver Comprehensive Addictions Rehabilitation and Evaluation Services (Denver CARES) center, an inpatient detoxification facility affiliated with Denver Health and Hospital System in Denver, CO. Control subjects without AUDs were recruited from the Denver VA Medical Center's smoking cessation clinic and via approved flyers posted on the University of Colorado's Anschutz Medical Campus in Aurora, CO. The institutional review boards at all participating sites approved this study, and all subjects provided written informed consent before their participation in this protocol.

Subjects with AUDs were eligible to participate if they met all of the following criteria at study entry: 1) an Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) score of ≥8 for men or ≥5 for women, 2) alcohol use within the 7 days before enrollment, and 3) age of ≥21 yr. The AUDIT questionnaire is a standardized set of 10 questions that detect current and previous alcohol abuse, which has been validated in a variety of clinical settings (45). Furthermore, to meet eligibility as a control, control subjects' AUDIT values were required to be <8 for men or <5 for women. Screening of potential control subjects centered on matching these control subjects to AUD subjects in terms of age, sex, and smoking history. With the use of AUDIT data, both subjects and controls were stratified into zones 1–4, classifying the severity of their alcohol consumption (37, 50). Zone stratification was performed to enable comparisons between AUDs and abstinence, as well as between AUDs and low-risk drinking. AUDIT scoring zones clinically correlated to abstinence (zone 1), low-risk drinking (zone 2), mild to moderate alcohol misuse with a lower risk of alcohol dependence (zone 3), and severe alcohol misuse (zone 4).

Cigarette-smoking history was assessed by self-report. In subjects who were either actively smoking cigarettes, or who had previously smoked, the number of packs per day smoked was collected, as well as total number of years smoking, to calculate the pack-year history. In previous (but not current) smokers, the number of years that had elapsed since stopping smoking was also recorded. Current smokers were also analyzed according to packs per day smoked. Nonsmokers were characterized as subjects who did not smoke at all in the past year, moderate smokers currently consumed <1 pack of cigarettes per day, whereas heavy smokers consumed 1 or more packs per day (31). Analyzing subjects in larger groups according to smoking intensity was performed to optimize the clinical applicability of the results, given the variability of cigarette smoking reported in our cohort.

In an effort to minimize the effects of comorbidities on outcome variables, AUD subjects and controls were ineligible to participate in the study if they met any of the following criteria: 1) prior medical history of liver disease (documented history of cirrhosis, total bilirubin ≥2.0 mg/dl, or serum albumin <3.0), 2) prior medical history of gastrointestinal bleeding (due to the concern for varices), 3) prior medical history of heart disease (documentation of ejection fraction <50%, myocardial infarction, or severe valvular dysfunction), 4) prior medical history of renal disease (end-stage renal disease requiring dialysis, or a serum creatinine ≥2 mg/dl), 5) prior medical history of lung disease defined as an abnormal chest radiograph or spirometry (forced vital capacity or forced expiratory volume in 1 s <75%), 6) concurrent illicit drug use defined as a toxicology screen for cocaine, opiates, or methamphetamines, 7) prior history of diabetes mellitus, 8) prior history of human immunodeficiency virus, 9) failure of the patient to provide informed consent, 10) pregnancy, or 11) abnormal nutritional status. The nutritional status was assessed using the nutritional risk index (NRI) with the subject's albumin, current weight, and usual weight values in the following equation (17): NRI = 1.519 (albumin in g/l) + (current weight/usual weight) * 100 + 0.417. Subjects were considered to have a normal nutritional status if the NRI was ≥90 and an abnormal NRI if it was <90. Potential subjects >55 yr of age were also excluded to minimize the presence of concomitant but asymptomatic comorbidities.

Study protocol.

Eligible subjects with AUDs were admitted to the University of Colorado Hospital Clinical and Translational Research Center (CTRC) for bronchoscopy. All bronchoscopy procedures were performed utilizing telemetry monitoring and standard conscious sedation protocols as previously described (25). The bronchoscope was wedged into a subsegment of either the right middle lobe or the lingula. Three to four 50-ml aliquots of sterile, room temperature 0.9% saline were sequentially instilled and recovered with gentle aspiration. The first aspirated aliquot was not utilized in experiments for this investigation. The second and subsequent aliquots were combined and used in experiments as representative of the distal airspaces. AUD subjects were discharged ∼24 h after completion of bronchoscopy. Control subjects had bronchoscopy performed in a similar fashion but were discharged the same day.

Laboratory processing.

BAL samples were transported to the laboratory in sterile 50-ml conical tubes. BAL fluid was immediately centrifuged (900 g, 5 min) after collection to separate cellular and acellular components. Specimens that were not assayed immediately were aliquoted and stored at −80°C.

Cytokine/growth factor assays.

Acellular BAL fluid was used in assays to assess differences in cytokine/chemokine/growth factors within the alveolar space using a multiplex bead array (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) according to manufacturer instructions and as previously described by our own laboratories (2, 16). Multiplex bead array cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors included: IL-1β, IL-1RA, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-9, IL-10, IL-12, IL-13, IL-15, IL-17, eotaxin, fibroblast growth factor (FGF), granulocyte colony stimulating factor, granulocyte-monocyte colony stimulating factor, interferon (IFN)-γ, IFN-γ-induced protein 10 (IP-10, also known as CXCL10), monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (also known as CCL2), macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α (also known as CCL3), MIP-1β (also known as CCL4), platelet-derived growth factor, regulated and normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES, also known as CCL5), TNF-α, and VEGF. All measurements were performed in duplicate.

Statistical analyses.

Data were classified as parametrically or nonparametrically distributed based on testing of the variances. Parametrically distributed data were analyzed with a paired t-test for continuous outcome variables. Categorical data were compared using the Fisher's exact test. Nonparametrically distributed data involving >2 groups were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test. When significant differences within groups were observed, post hoc comparisons between pairs were subsequently performed using the Wilcoxon method. Univariate correlations between continuous variables were also assessed using the Spearman method to assess correlation (ρ). A version of the false discovery rate procedure that accounts for related comparisons was used to establish which responses remained significantly different, controlling for multiple testing (4, 5). Statistical analyses were performed using JMP 9.2 (Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Baseline demographics of enrolled subjects.

Twenty subjects with AUDs were enrolled in these investigations, along with 19 healthy controls (Table 1). Ages between the two groups were similar as were the percentage of current smokers. There was a nonsignificant difference in the number of men between groups. Racial differences were present between the AUDs and control groups; more Caucasian subjects were enrolled in the control group, whereas more Native Americans were enrolled in the AUD group. Cigarette-smoking habits did not vary significantly by age (P = 0.87), by sex (P = 1.0), or by race (P = 0.08). The AUD group had significantly higher AUDIT scores than did controls, with AUD subjects falling exclusively in consumption zones 3 and 4, whereas control subjects fell in zones 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Demographics of subjects with AUDs and controls

| AUD Subjects, n = 20 | Control Subjects, n = 19 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 42.7 ± 7.0 | 41.4 ± 6.7 | 0.58 |

| Current smokers, % | 50% | 47% | 1.0 |

| Pack-year smoking, mean | 13 ± 12 | 9 ± 14 | 0.41 |

| Pack-year smoking, median | 10 [0-24] | 0 [0-20] | 0.18 |

| Packs per day, mean | 0.5 ± 0.4 | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 0.25 |

| Packs per day, median | 0.5 [0–0.5] | 0 [0–0.6] | 0.27 |

| Sex, % men | 65% | 47% | 0.34 |

| Race, % | 0.05 | ||

| White | 40% (8/20) | 74% (14/19) | |

| African-American | 10% (2/20) | 16% (3/19) | |

| Latino | 30% (6/20) | 11% (2/19) | |

| Native American | 20% (4/20) | 0% (0/19) | |

| AUDIT Score | 25.4 ± 9.1 | 2.3 ± 1.8 | <0.0001 |

| Zone 1 (abstinence) | 0/20 | 5/19 | <0.0001* |

| Zone 2 (low-risk drinking) | 0/20 | 14/19 | |

| Zone 3 (moderate alcohol misuse) | 4/20 | 0/19 | |

| Zone 4 (severe alcohol misuse) | 16/20 | 0/19 | |

| Days per week drinking alcohol | 5.1 ± 1.7 | 0.7 ± 0.9 | <0.0001 |

AUD, alcohol use disorder; AUDIT, alcohol use disorders identification test; WBC, white blood cell.

Comparison of AUDIT zones between alcohol use disorder subjects and control subjects using Pearson's test.

Cell counts and differentials from BAL were similar between the AUD and non-AUD subjects although smokers in each group had higher total cell counts (P = 0.002 for comparison across all AUD and non-AUD subjects, stratified by smoking, Table 2). Similarly, smokers both with and without AUDs had significantly higher total monocyte counts (P = 0.002). The percentage of each cell type did not vary by alcohol or smoking history.

Table 2.

Cell counts and differentials of subjects with alcohol use disorders, stratified by smoking

| (+)AUD/(+)Smoking | (+)AUD/(-)Smoking | (-)AUD/(+)Smoking | (-)AUD/(-)Smoking | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC count in BAL, million cells | 20.1 ± 8.6 | 12.2 ± 6.5 | 29.8 ± 19.8† | 10.3 ± 4.2 | 0.002 |

| %monocytes/macrophages | 92.7 ± 1.8 | 88.9 ± 6.3 | 92.8 ± 1.9 | 90.1 ± 8.6 | 0.36 |

| Total monocyte count, millions | 18.6 ± 8.0 | 10.8 ± 6.2 | 27.7 ± 18.2* | 9.4 ± 4.4 | 0.002 |

| %lymphocytes | 5.1 ± 2.3 | 9.5 ± 6.2 | 5.2 ± 2.9 | 7.0 ± 5.5 | 0.14 |

| lymphocyte count, millions | 1.0 ± 0.6 | 1.1 ± 0.9 | 1.7 ± 1.7 | 0.6 ± 0.4 | 0.17 |

| %neutrophils | 2.2 ± 1.5 | 1.5 ± 1.3 | 1.9 ± 1.2 | 2.9 ± 4.0 | 0.59 |

| neutrophil count, millions | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.09 |

Applicable values are means ± SE. Comparisons assessed via ANOVA, with post hoc comparisons corrected for multiple comparisons.

P < 0.007 compared with (+)AUD/(-)smoke and to (-)AUD/(-)smoke;

P < 0.008 compared with (+)AUD/(-)smoke and to (-)AUD/(-)smoke.

BAL measurements for IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, IL-17, eotaxin, FGF, and MIP-1α were below the detection limit of the assay for the majority of subjects (>50%) assessed; therefore, results for these factors were not analyzed further.

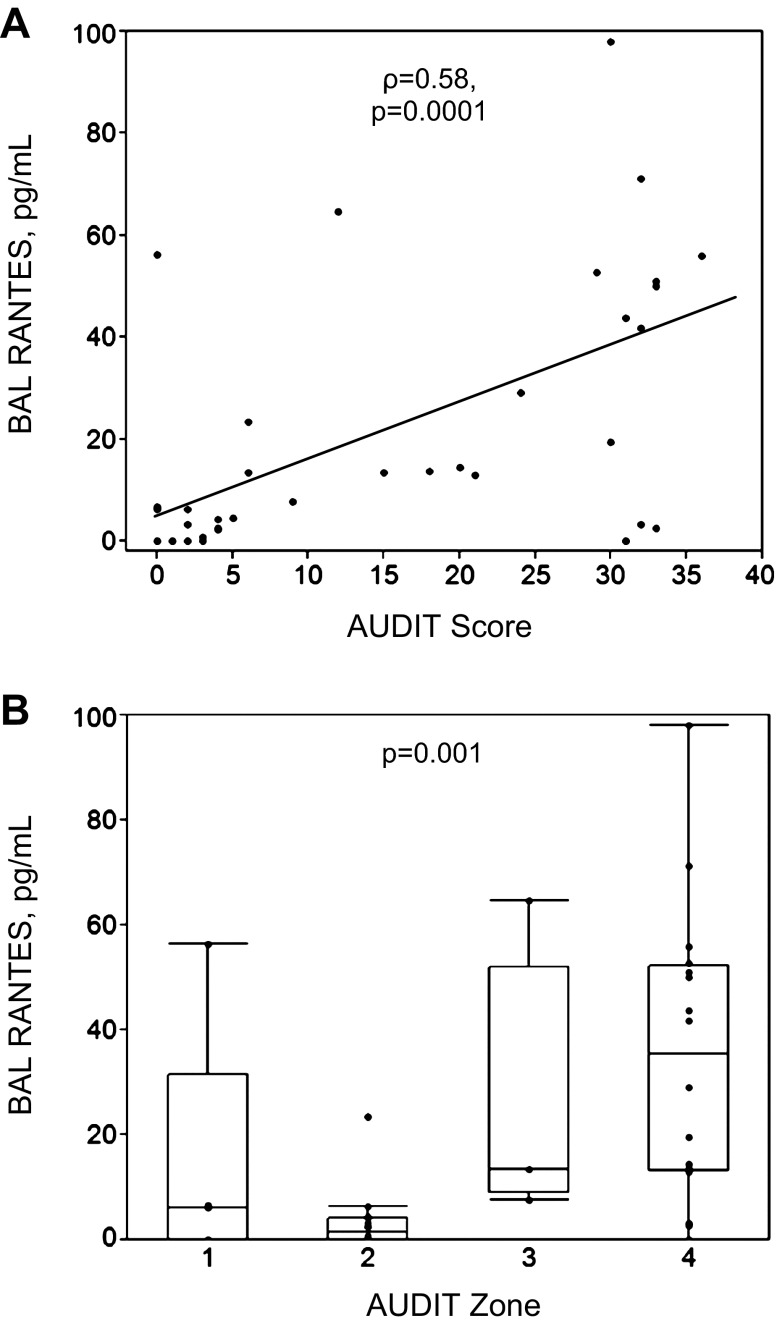

Dose-dependent association between BAL RANTES and alcohol use.

Correlations in BAL cytokines were examined in relation to the AUDIT scores from the 39 total subjects collected at the time of bronchoscopy. A positive correlation was observed between the quantity of BAL RANTES and subjects' AUDIT scores (ρ = 0.58, P = 0.0001, Fig. 1A). Comparing RANTES across AUDIT zones confirmed that, with increasing severity of alcohol dependence, RANTES was increased (P = 0.001, Fig. 1B). Moreover, values for both zone 3 (P = 0.005) and zone 4 (P = 0.0004) were significantly greater than those from subjects in zone 2 (low-risk drinkers), accounting for multiple comparisons. No significant correlations were observed between AUDIT scores and any other cytokine, chemokine, or growth factor in BAL, including IL-1β (P = 0.83), IL-6 (P = 0.94), TNF-α (P = 0.25), IL-15 (P = 0.11), IP-10 (P = 0.31), IL-8 (P = 0.91), or IFN-γ (P = 0.35). Among all subjects with AUDs, BAL RANTES was positively associated with IP-10 (ρ = 0.53, P = 0.02).

Fig. 1.

Regulated and normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES, also known as CCL5) present in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) increased as the severity of alcohol misuse increased in the 39 alcohol use disorder (AUD) subjects and controls. Alcohol misuse was characterized in severity according to the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT). A: AUDIT score vs. BAL RANTES (Spearman's correlation coefficient = ρ). B: subjects and controls were stratified into 4 zones according to AUDIT scores. Controls were contained in zone 1 (abstinence) and zone 2 (low-risk drinking), whereas AUD subjects were contained in zone 3 (moderate alcohol misuse) and zone 4 (severe alcohol misuse). Kruskal-Wallis test used in analyses.

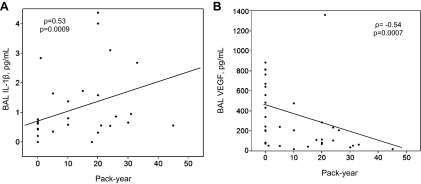

Dose-dependent association of cytokines in BAL and cigarette smoking.

Potential associations between cigarette-smoking history and BAL cytokines were examined. Pack-year data were missing from 4 of the 19 currently smoking AUD and control subjects. Five current nonsmokers had smoked previously but had stopped smoking more than 1 yr before bronchoscopy. In the cohort of 35 AUD subjects and controls (both current smokers and nonsmokers) who had complete smoking pack-year data, significantly positive correlations were observed between pack-years smoked and IL-1β (ρ = 0.53, P = 0.0009) (Fig. 2). Conversely, inverse associations between VEGF and pack-year smoked were observed for (ρ = −0.54, P = 0.0007). The direction and significance of these associations persisted when the five previously smoking, but not currently smoking, individuals were excluded from the analyses. No significant correlations were observed between pack-years and IL-6 (ρ = 0.15), IL-8 (ρ = 0.40), IFN-γ (ρ = −0.31), IL-1RA (ρ = 0.34), IL-12 (ρ = −0.48), or TNF-α (ρ = −0.15).

Fig. 2.

In current smokers (n = 35), significant associations were determined to be present when cigarette-smoking duration, assessed via pack-year history, was assessed in relationship with BAL IL-1β (A), and VEGF (B). Spearman's correlation coefficient = ρ.

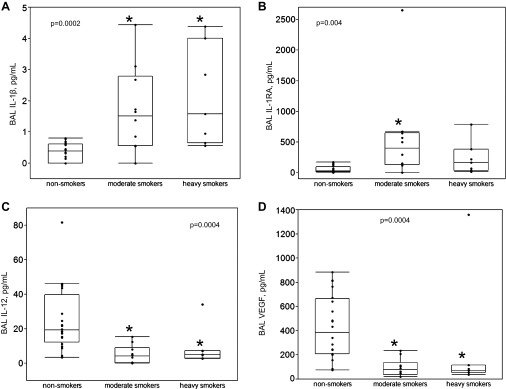

Next, the relationship between packs per day smoking and cytokines was examined in the 37 subjects with complete pack per day smoking data. In univariate analyses, significant positive correlations were observed between packs per day smoking and IL-1β (ρ = 0.66, P < 0.0001) and IL-1RA (ρ = 0.46, P = 0.005), whereas significant inverse correlations were observed between packs per day smoking with IL-12 (ρ = −0.58, P = 0.0002) and VEGF (ρ = −0.58, P = 0.0002), correcting for multiple comparisons. After stratifying subjects with complete pack per day smoking data into noncurrent smokers (n = 20), moderate smokers (n = 10), and heavy smokers (n = 7) (Fig. 3), we noticed that IL-1β values increased with the intensity of cigarette smoking (P = 0.0002); both moderate (P = 0.002) and heavy (P = 0.0008) cigarette smokers had significantly higher IL-1β values than did nonsmokers in post hoc comparisons. Similar results were observed for IL-1RA (P = 0.004) although only the difference in values between moderate smokers and nonsmokers remained in post hoc comparisons (P = 0.002). In contrast, IL-12 (P = 0.0004) and VEGF (P = 0.0004) also differed significantly across the three levels of smoking. For each of these factors, values in the nonsmoking group were significantly higher than either the moderate or heavy smoking groups.

Fig. 3.

Correlations between cigarette-smoking intensity, assessed via packs smoked per day, were observed with BAL IL-1β (A), IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA) (B), IL-12 (C), and VEGF (D). Nonsmokers are not currently smoking (n = 20); moderate smokers currently smoke <1 pack per day (n = 10); heavy smokers currently smoke ≥1 packs per day (n = 7). Boxes indicate intraquartile range of data, with medians (50th percentile); whiskers indicate 10th and 90th percentiles of data. Kruskal-Wallis testing was used to compare medians across all 3 groups (P values provided). Post hoc within-group comparisons were also performed. Both moderate and heavy smokers had significantly different median values than nonsmokers for BAL IL-1β, IL-12, and VEGF; for IL-1RA, only moderate smokers had significantly different median values than did nonsmokers (*P < 0.05 compared with nonsmokers).

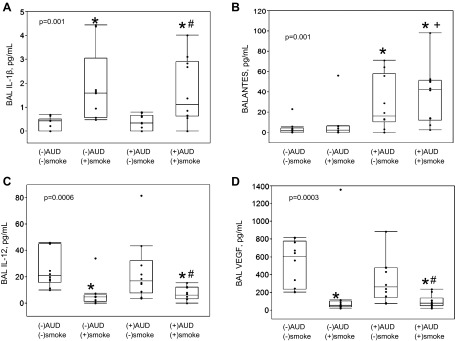

Effect of combined AUDs and cigarette smoking on BAL cytokine, chemokine, and growth factor composition.

The 39 subjects were stratified into four groups based on a history of AUDs and current cigarette smoking. Ten subjects did not have an AUD and did not smoke; nine did not have an AUD but did smoke; ten had an AUD but did not smoke; and ten had an AUD and smoked. Significant differences were noted to be present across the four groups for BAL IL-1β (P = 0.001), RANTES (P = 0.001), IL-12 (P = 0.0006), and VEGF (P = 0.0003) (Fig. 4). After post hoc within-group comparisons were performed, cigarette smoking, but not alcohol, appeared to be driving both the higher values of BAL IL-1β, as well as the lower values of BAL IL-12 and VEGF. Examining the data among AUD subjects only revealed that subjects with AUDs who smoked cigarettes had significantly elevated BAL IL-1β compared with AUD subjects who did not smoke. However, values for the AUD group who smoked were not significantly different from non-AUD smoking controls. Similarly, for BAL IL-12 and VEGF, among AUD subjects only, lower values were observed in AUD subjects who smoked. However, as with IL-1β, values for the AUD group who smoked were not significantly different from non-AUD subjects who smoked. In contrast, BAL RANTES values among subjects with AUDs were significantly higher compared with non-AUD subjects, regardless of cigarette smoking. In the AUD subjects only, RANTES values were not significantly more elevated among cigarette smokers. Therefore, our data suggest that smoking influences BAL IL-1β, IL-12, and VEGF, independent of AUDs, whereas an AUD history influences RANTES, independent of smoking.

Fig. 4.

The 39 subjects were stratified by AUDs and current tobacco use: (-)AUDs and (-)smoking, n = 10; (-)AUDs and (+)smoking, n = 9; (+)AUDs and (-)smoking, n = 10; (+)AUDs and (+)smoking, n = 10. Boxes indicate intraquartile range of data, with medians (50th percentile); whiskers indicate 10th and 90th percentile of data. Significant differences between median values across the 4 groups were observed in BAL IL-1β (A), RANTES (B), IL-12 (C), and VEGF (D), (P values provided, using Kruskal-Wallis testing). Subsequent post hoc comparisons between the 4 subgroups (using the Wilcoxon method) revealed that smokers, either with or without AUDs, had significantly higher IL-1β than did non-AUD, nonsmokers. For RANTES, both AUD smokers and nonsmokers had significantly higher values than did non-AUD, nonsmokers. Conversely, smokers, either with or without AUDs, had significantly lower IL-12 and VEGF compared with non-AUD, nonsmokers. For these comparisons, *P < 0.01. Among AUD subjects only, comparing smokers to nonsmokers revealed significant differences in IL-1β, IL-12, and VEGF (#P < 0.02). Finally, among smoking subjects only, comparing AUD to non-AUD subjects revealed significant differences in RANTES (+P < 0.008).

Correlations between demographic factors and cytokine values.

To determine whether specific, unalterable demographic characteristics might have influenced our BAL data, we examined the relationship of age, race, and sex with different cytokine values. We observed that age was associated with decreased IL-7 (ρ = −0.40, P = 0.01). Although our cohort consisted primarily of white subjects, we did examine a number of African-American, Hispanic, and Native Americans as well. However, of the 19 evaluable cytokines/growth factors within BAL, we did not observe any significant differences referable to race to persist after correcting for multiple comparisons. Similarly, there were no remarkable cytokine differences between women in the cohort compared with men.

Correlations between resident lung cells and cytokine values.

To help establish the potential cells of origin responsible for cytokine production, correlations between the absolute number of different cell types obtained during BAL and cytokine values were examined. The total white blood cell number per milliliter of BAL fluid was positively associated with IL-1β (ρ = 0.61, P < 0.0001) but inversely associated with IL-12 (ρ = −0.49, P = 0.002) and VEGF (ρ = −0.48, P = 0.002). Results were similar for the absolute monocyte count that was positively associated with IL-1β (ρ = 0.58, P = 0.0001) and negatively associated with IL-12 (ρ = −0.52, P = 0.0006) and VEGF (ρ = −0.51, P = 0.0009). Finally, the absolute neutrophil count was most strongly associated with IL-1β (ρ = 0.48, P = 0.002) and IL-1RA (ρ = 0.48, P = 0.002) but inversely associated with IL-12 (ρ = −0.42, P = 0.007). No correlation between IL-10 or RANTES and the total white blood cell count or any specific cell type was observed.

DISCUSSION

In these investigations, AUDs and cigarette smoking were associated with alterations in pulmonary levels of specific cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors. The relationship of these two environmental mediators to measured BAL cytokines appeared related to different inflammatory pathways, and no evidence of synergism between AUDs and smoking was observed. Nevertheless, the elevation of BAL RANTES in association with AUDs, along with elevated IL-1β in association with cigarette smoking, suggests that an independent but potentially additive proinflammatory milieu may be present in individuals who are coexposed to both alcohol and cigarettes. To our knowledge, this is the first report in a sizable cohort of well-characterized human subjects of elevated BAL RANTES in association with AUD severity; alterations in BAL IL-12 and VEGF in the context of cigarette smoking and AUDs are also novel. We confirmed previously reported positive relationships between cigarette smoking with BAL IL-1β expression (31) and decreased VEGF expression (30, 60). Dose-response relationships between cigarette smoking with IL-1β, IL-1RA, IL-12, and VEGF were also observed. Collectively, our work suggests that cigarette smoking contributes to a proinflammatory milieu characterized via increasing IL-1β, whereas increases in RANTES associated with AUDs may further accentuate this proinflammatory environment. Moreover, the association of tobacco with decreased IL-12 and VEGF suggests potential influences on cellular immunity and alveolar epithelial permeability related to these substances, independent of AUDs. Our observations provide new, clinically relevant insight regarding the relationship between AUDs, cigarette smoking, and pneumococcal pulmonary disease. These data may also help explain the severity of pneumococcal illness, as several of these cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors have been reported to have specific roles in colonization, infection, and clearance of pneumococcus.

Alveolar macrophages produce type I interferons in response to recognition of pneumococcal DNA. This recognition stimulates RANTES production in infected cells and neighboring alveolar epithelial cells (28). RANTES is a CC chemokine that serves as a chemoattractant for a variety of immune cell types (53). In our subjects with AUDs, RANTES levels correlated with levels of IP-10, a CXC chemokine secreted by cells in response to IFN-γ. In the setting of experimental pneumococcal pneumonia, pulmonary levels of RANTES and IP-10 may be increased (21, 40) and, along with other proinflammatory cytokines, appear to play a role in the pneumococcal immune response. In animal experiments using an EF3030 pneumococcal strain, RANTES also influenced the production of antibodies that limited the progression of nasopharyngeal pneumococcal carriage to frank pneumonia and influenced survival (40). Our observation that BAL RANTES was increased in a dose-dependent fashion among subjects with AUDs suggests a potential protective role of alcohol in pneumococcal infection. However, published investigations have alluded to a critical effect of alcohol metabolism on RANTES expression (70) and suggest that overexpression of RANTES may be pathological. Moreover, RANTES overproduction has recently been reported to decrease T cell progeny and increase myeloid progenitors in a murine model. This could influence immune responses to pathogens and may be important in aging-associated immunodeficiency (20). As a final consideration, downregulation of RANTES receptor, CCR5, could also have affected our results; AUDs have previously been associated with a decrease in CD4+ T cell CCR5 density (41) that potentially influences the balance between cellular and humoral immunity. Understanding the effect of alcohol use on RANTES expression in the lung and nasopharynx, as well as its effect on CCR5, its receptor, will clarify the importance of this cytokine on pneumococcal susceptibility among those with AUDs.

Although the association of serious pneumococcal infections and cigarette smoking have been reported consistently in the literature, reasons for this association are incompletely understood. A recent series examining BAL from a large cohort of smokers with no pulmonary symptomatology, normal pulmonary function tests, and chest radiographs provides convincing evidence that current smoking in and of itself leads to an increased total number of recovered cells in BAL (27), suggesting that smoking without frank pulmonary disease can contribute to a proinflammatory state within the lung. In our series of smokers, IL-1β values were most strongly associated with the absolute number of monocytes. The IL-1 family of cytokines is important in early innate immune responses (58); notably, a dose-dependent association between cigarette smoking with BAL IL-1β has previously been reported (31). In animal models exposed to cigarette smoke extract, IL-1β production and signaling along with pulmonary neutrophilia are believed to occur through Toll-like receptor (TLR)4 activation (18). TLRs are key initiators in recognizing pathogen-associated molecular peptides, including pneumolysin, produced by the pneumococcus (32). Pneumolysin binds directly to TLR4, where it results in production of proinflammatory mediators and induces epithelial cell apoptosis (56). In a recently published investigation using an experimental model of pneumococcal infection, chronic cigarette smoke exposure followed by challenge with live S. pneumoniae was associated with increased IL-1β in lung homogenates, BAL neutrophilia, increased pulmonary bacterial burden, and worsened clinical signs of pneumococcal pneumonia (42). Our investigations suggest the possibility that cigarette smoke exposure results in a baseline increase in the proinflammatory state of the lung. Upon exposure to products of the pneumococcus (i.e., pneumolysin), additional inflammation may further overwhelm the host response, resulting in an inability to clear the pathogen with subsequent disease progression, perhaps due to slowed resolution of neutrophilia in conjunction with damaged alveolar epithelium.

IL-12 is a regulatory cytokine that contributes to both innate and acquired immunity, with a crucial role in host resistance to pneumococcal infection (59). IL-12 is derived from lymphocytes and has the ability to stimulate the proliferation of T cells, induce NK cell formation, and induce IFN-γ production. Chronic cigarette smoke exposure has been associated with a significant increase in BAL IL-12 in a mouse model (8), but no reports in the literature comment on the effect of either alcohol or smoking on this cytokine in lung. Understanding the role of IL-12 on pneumococcal immunity in humans may be important in improving the efficacy of vaccines to combat this pathogen, particularly in high-risk groups (26). IL-12 has been proposed as an adjuvant with recombinant pneumococcal protein antigens in experimental mucosal vaccines (67). Ex vivo human BAL cells that had been treated using this strategy were determined to have increased TNF-α production (and to a lesser extent, IFN-γ production) compared with exposure of cells with pneumococcal antigen alone (68). Nevertheless, progress in the use of IL-12 as an adjuvant for human pneumococcal vaccines requires further investigation to limit its toxicity and to optimize efficacious delivery to the mucosa (24).

Cigarette smoking has been associated with decreased BAL VEGF and VEGF receptor-2 expression; levels become more decreased as smoking-related lung disease progresses (30, 60). These abnormalities may be related to the direct effect of cigarette smoke on airway epithelial cells (61), where it can induce cellular apoptosis and necrosis (29). In contrast, moderate doses of alcohol experimentally enhance VEGF expression, as well its interaction with the VEGFR-2 receptor (14–15, 23). Abnormal VEGF homeostasis in the lung elicited by cigarette smoking could be a factor in the development of complicated pneumococcal infections, such as empyema (66). Through potential effects on alveolar epithelial permeability, alterations in pulmonary VEGF could also play a role in the development of the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) that may complicate pneumococcal pneumonia. Significantly lower BAL VEGF levels have been reported both in the early and late phases of ARDS, compared with either healthy subjects (1) or patients at risk for ARDS (62). Collectively, these investigations suggest that aberrant pulmonary VEGF homeostasis due to effects of cigarette smoking coupled with effects of AUDs on alveolar epithelial integrity (11) may place individuals who use both substances at risk for increased morbidity in the setting of pneumococcal infection.

We have highlighted potential mechanisms whereby AUDs and cigarette smoking might influence the cytokine milieu in lung to increase the risk for infection with the pneumococcus, given that it is the most common etiological agent for community-acquired pneumonia worldwide. However, it should be noted that AUDs and cigarette smoking also have a significant impact on the predisposition for other common pulmonary infections. A major example would be the relationship between cigarette smoking and the development of influenza (19), where in murine models, cigarette smoke adversely affects the primary immune response to influenza (48). Notably, in the most recent H1N1 epidemic, cigarette smoking increased the risk for hospitalization in the context of this illness (65), further adding to the clinical relevance of this association. Chronic exposure to alcohol in animal models enhances the severity of influenza infection (35) and has also been associated with the development of seasonal influenza, but not specifically H1N1 (47). Improved understanding of the relationship between smoking, AUDs, and influenza could be important given pneumonia that commonly occurs after primary influenza infections. Tuberculosis is another important pulmonary disease frequently linked to AUDs and cigarette smoking. Worldwide, a very strong association between AUDs and tuberculosis has been reported, with ∼10% of cases linked to alcoholism. Several countries have proposed measures to address both the pulmonary disease concomitantly with AUDs to improve the efficacy of directly observed therapies (44). The literature further supports cigarette smoking as a modifiable risk factor for tuberculosis infection as well as the development of symptomatic tuberculosis (3). Our work hopefully provides some insight for investigations related to these and other important alcohol- and smoking-related pulmonary diseases.

Our investigations are not without limitations. First, the total number of subjects enrolled in these investigations was not large, and therefore the power of the associations we observed is limited. Nevertheless, this is the largest cohort of closely matched human subjects with well-characterized alcohol use and cigarette smoking data examined via bronchoscopy that we have encountered in the literature. Given ethical issues with bronchoscopy in asymptomatic human subjects, we believe that our results provide a translational perspective to previously published animal and human work. Secondly, smoking and alcohol history were provided by self-report that might limit the accuracy of these data. Certainly, biological assessment of smoking (e.g., serum cotinine) could better clarify dose-response relationships between cigarette smoking and cytokines, but biological markers for severity of alcohol misuse are lacking. Nevertheless, subjects with AUDs were recruited from a detoxification center that had a long-standing treatment relationship with these individuals, enhancing the validity of their AUD characterization. Potential unmeasured confounders might have influenced our results, such as occult liver disease. However, screening laboratory work and pulmonary examination suggested no occult illness in our subjects or controls. Finally, we acknowledge that these investigations do not prove that alcohol or cigarettes are directly causal to the cytokine differences we observed. Our work does not explain the operative mechanisms underlying the reasons that AUDs, cigarette smoking, or both may contribute to pulmonary infections, including pneumococcal pneumonia. It does, however, provide a framework to understand the potential associations of AUDs and smoking on pulmonary cytokines, thereby directing future investigations to help unravel mechanisms of increased predisposition for pulmonary infections in this population.

In conclusion, we observed an association between the proinflammatory cytokine RANTES and AUDs that was independent of cigarette smoking. We confirmed that cigarette smoking was associated with an increase in the proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β, as well as decreases in IL-12 and VEGF. These abnormalities suggest an excessively proinflammatory state in the lung in the setting of AUDs and cigarette smoking and also potential influences on adaptive immunity (via IL-12) and alterations in epithelial permeability (via VEGF). Collectively, these observations can help delineate the relationship of AUDs and cigarette smoking on the predisposition for pneumococcal pulmonary infection and also provide insight regarding reasons for increased disease severity among these individuals.

GRANTS

This study was supported in part by R24 AA019661 (E. Burnham), NIH/NCATS Colorado CTSI Grant Number UL1 TR000154T32 (E. Burnham), T32 AA13527 (C. Davis), the Ralph and Marian C Falk Medical Research Trust (E. Kovacs), and R01 AA012034 (E. Kovacs). Contents are the authors' sole responsibility and do not necessarily represent official NIH views.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: E.L.B., E.J.K., and C.S.D. conception and design of research; E.L.B. analyzed data; E.L.B., E.J.K., and C.S.D. interpreted results of experiments; E.L.B. prepared figures; E.L.B. drafted manuscript; E.L.B., E.J.K., and C.S.D. edited and revised manuscript; E.L.B., E.J.K., and C.S.D. approved final version of manuscript; C.S.D. performed experiments.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Luis Ramirez for assistance with laboratory assays, Dr. Douglas Curran-Everett for biostatistical assistance, the staff at Denver CARES to facilitate the performance of this research, and the support of Dr. Robert House.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abadie Y, Bregeon F, Papazian L, Lange F, Chailley-Heu B, Thomas P, Duvaldestin P, Adnot S, Maitre B, Delclaux C. Decreased VEGF concentration in lung tissue and vascular injury during ARDS. Eur Respir J 25: 139–146, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albright JM, Davis CS, Bird MD, Ramirez L, Kim H, Burnham EL, Gamelli RL, Kovacs EJ. The acute pulmonary inflammatory response to the graded severity of smoke inhalation injury. Crit Care Med 40: 1113–1121, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bates MN, Khalakdina A, Pai M, Chang L, Lessa F, Smith KR. Risk of tuberculosis from exposure to tobacco smoke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 167: 335–342, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benjamini Y, Yekutieli D. The control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing under dependency. Ann Stat 29: 1165–1188, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benjamini Y, Drai D, Elmer G, Kafkafi N, Golani I. Controlling the false discovery rate in behavior genetics research. Behav Brain Res 125: 279–284, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhatty M, Pruett SB, Swiatlo E, Nanduri B. Alcohol abuse and Streptococcus pneumoniae infections: consideration of virulence factors and impaired immune responses. Alcohol 45: 523–539, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boe DM, Richens TR, Horstmann SA, Burnham EL, Janssen WJ, Henson PM, Moss M, Vandivier RW. Acute and chronic alcohol exposure impair the phagocytosis of apoptotic cells and enhance the pulmonary inflammatory response. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 34: 1723–1732, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braber S, Henricks PA, Nijkamp FP, Kraneveld AD, Folkerts G. Inflammatory changes in the airways of mice caused by cigarette smoke exposure are only partially reversed after smoking cessation. Respir Res 11: 99, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown GP, Iwamoto GK, Monick MM, Hunninghake GW. Cigarette smoking decreases interleukin 1 release by human alveolar macrophages. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 256: C260–C264, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burnham EL, Gaydos J, Hess E, House R, Cooper J. Alcohol use disorders affect antimicrobial proteins and anti-pneumococcal activity in epithelial lining fluid obtained via bronchoalveolar lavage. Alcohol Alcohol 45: 414–421, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burnham EL, Halkar R, Burks M, Moss M. The effects of alcohol abuse on pulmonary alveolar-capillary barrier function in humans. Alcohol Alcohol 44: 8–12, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burnham EL, Phang TL, House R, Vandivier RW, Moss M, Gaydos J. Alveolar macrophage gene expression is altered in the setting of alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 35: 284–294, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crews FT, Bechara R, Brown LA, Guidot DM, Mandrekar P, Oak S, Qin L, Szabo G, Wheeler M, Zou J. Cytokines and alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 30: 720–730, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Das SK, Mukherjee S, Vasudevan DM. Effects of long term ethanol consumption mediated oxidative stress on neovessel generation in liver. Toxicol Mech Methods 22: 375–382, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Das SK, Varadhan S, Gupta G, Mukherjee S, Dhanya L, Rao DN, Vasudevan DM. Time-dependent effects of ethanol on blood oxidative stress parameters and cytokines. Indian J Biochem Biophys 46: 116–121, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis CS, Albright JM, Carter SR, Ramirez L, Kim H, Gamelli RL, Kovacs EJ. Early pulmonary immune hyporesponsiveness is associated with mortality after burn and smoke inhalation injury. J Burn Care Res 33: 26–35, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Detsky AS, Baker JP, Mendelson RA, Wolman SL, Wesson DE, Jeejeebhoy KN. Evaluating the accuracy of nutritional assessment techniques applied to hospitalized patients: methodology and comparisons. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 8: 153–159, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doz E, Noulin N, Boichot E, Guenon I, Fick L, Le BM, Lagente V, Ryffel B, Schnyder B, Quesniaux VF, Couillin I. Cigarette smoke-induced pulmonary inflammation is TLR4/MyD88 and IL-1R1/MyD88 signaling dependent. J Immunol 180: 1169–1178, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Epstein MA, Reynaldo S, El-Amin AN. Is smoking a risk factor for influenza hospitalization and death? J Infect Dis 201: 794–795, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ergen AV, Boles NC, Goodell MA. Rantes/Ccl5 influences hematopoietic stem cell subtypes and causes myeloid skewing. Blood 119: 2500–2509, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fillion I, Ouellet N, Simard M, Bergeron Y, Sato S, Bergeron MG. Role of chemokines and formyl peptides in pneumococcal pneumonia-induced monocyte/macrophage recruitment. J Immunol 166: 7353–7361, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia-Vidal C, Ardanuy C, Tubau F, Viasus D, Dorca J, Linares J, Gudiol F, Carratala J. Pneumococcal pneumonia presenting with septic shock: host- and pathogen-related factors and outcomes. Thorax 65: 77–81, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gu JW, Elam J, Sartin A, Li W, Roach R, Adair TH. Moderate levels of ethanol induce expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and stimulate angiogenesis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 281: R365–R372, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hedlund J, Langer B, Konradsen HB, Ortqvist A. Negligible adjuvant effect for antibody responses and frequent adverse events associated with IL-12 treatment in humans vaccinated with pneumococcal polysaccharide. Vaccine 20: 164–169, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hunninghake GW, Gadek JE, Kawanami O, Ferrans VJ, Crystal RG. Inflammatory and immune processes in the human lung in health and disease: evaluation by bronchoalveolar lavage. Am J Pathol 97: 149–206, 1979 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacups SP, Cheng A. The epidemiology of community acquired bacteremic pneumonia, due to Streptococcus pneumoniae, in the Top End of the Northern Territory, Australia–over 22 years. Vaccine 29: 5386–5392, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karimi R, Tornling G, Grunewald J, Eklund A, Skold CM. Cell recovery in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in smokers is dependent on cumulative smoking history. PLoS One 7: e34232, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koppe U, Suttorp N, Opitz B. Recognition of Streptococcus pneumoniae by the innate immune system. Cell Microbiol 14: 460–466, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kosmider B, Messier EM, Chu HW, Mason RJ. Human alveolar epithelial cell injury induced by cigarette smoke. PLoS One 6: e26059, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koyama S, Sato E, Haniuda M, Numanami H, Nagai S, Izumi T. Decreased level of vascular endothelial growth factor in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of normal smokers and patients with pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 166: 382–385, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuschner WG, D'Alessandro A, Wong H, Blanc PD. Dose-dependent cigarette smoking-related inflammatory responses in healthy adults. Eur Respir J 9: 1989–1994, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malley R, Henneke P, Morse SC, Cieslewicz MJ, Lipsitch M, Thompson CM, Kurt-Jones E, Paton JC, Wessels MR, Golenbock DT. Recognition of pneumolysin by Toll-like receptor 4 confers resistance to pneumococcal infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 1966–1971, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McClain CJ, Cohen DA. Increased tumor necrosis factor production by monocytes in alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology 9: 349–351, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCrea KA, Ensor JE, Nall K, Bleecker ER, Hasday JD. Altered cytokine regulation in the lungs of cigarette smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 150: 696–703, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meyerholz DK, Edsen-Moore M, McGill J, Coleman RA, Cook RT, Legge KL. Chronic alcohol consumption increases the severity of murine influenza virus infections. J Immunol 181: 641–648, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neill DR, Fernandes VE, Wisby L, Haynes AR, Ferreira DM, Laher A, Strickland N, Gordon SB, Denny P, Kadioglu A, Andrew PW. T regulatory cells control susceptibility to invasive pneumococcal pneumonia in mice. PLoS Pathog 8: e1002660, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neumann T, Neuner B, Gentilello LM, Weiss-Gerlach E, Mentz H, Rettig JS, Schroder T, Wauer H, Muller C, Schutz M, Mann K, Siebert G, Dettling M, Muller JM, Kox WJ, Spies CD. Gender differences in the performance of a computerized version of the alcohol use disorders identification test in subcritically injured patients who are admitted to the emergency department. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 28: 1693–1701, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nuorti JP, Butler JC, Farley MM, Harrison LH, McGeer A, Kolczak MS, Breiman RF. Cigarette smoking and invasive pneumococcal disease. Active Bacterial Core Surveillance Team. N Engl J Med 342: 681–689, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Omidvari K, Casey R, Nelson S, Olariu R, Shellito JE. Alveolar macrophage release of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in chronic alcoholics without liver disease. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 22: 567–572, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palaniappan R, Singh S, Singh UP, Singh R, Ades EW, Briles DE, Hollingshead SK, Royal W, 3rd, Sampson JS, Stiles JK, Taub DD, Lillard JW., Jr CCL5 modulates pneumococcal immunity and carriage. J Immunol 176: 2346–2356, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perney P, Portales P, Clot J, Blanc F, Corbeau P. Diminished CD4+ T cell surface CCR5 expression in alcoholic patients. Alcohol Alcohol 39: 484–485, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Phipps JC, Aronoff DM, Curtis JL, Goel D, O'Brien E, Mancuso P. Cigarette smoke exposure impairs pulmonary bacterial clearance and alveolar macrophage complement-mediated phagocytosis of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun 78: 1214–1220, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Plevneshi A, Svoboda T, Armstrong I, Tyrrell GJ, Miranda A, Green K, Low D, McGeer A. Population-based surveillance for invasive pneumococcal disease in homeless adults in Toronto. PLoS One 4: e7255, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rehm J, Samokhvalov AV, Neuman MG, Room R, Parry C, Lonnroth K, Patra J, Poznyak V, Popova S. The association between alcohol use, alcohol use disorders and tuberculosis (TB). A systematic review. BMC Public Health 9: 450, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reinert DF, Allen JP. The alcohol use disorders identification test: an update of research findings. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 31: 185–199, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rijneveld AW, Florquin S, Branger J, Speelman P, Van Deventer SJ, van der Poll T. TNF-alpha compensates for the impaired host defense of IL-1 type I receptor-deficient mice during pneumococcal pneumonia. J Immunol 167: 5240–5246, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Riquelme R, Jimenez P, Videla AJ, Lopez H, Chalmers J, Singanayagam A, Riquelme M, Peyrani P, Wiemken T, Arbo G, Benchetrit G, Rioseco ML, Ayesu K, Klotchko A, Marzoratti L, Raya M, Figueroa S, Saavedra F, Pryluka D, Inzunza C, Torres A, Alvare P, Fernandez P, Barros M, Gomez Y, Contreras C, Rello J, Bordon J, Feldman C, Arnold F, Nakamatsu R, Riquelme J, Blasi F, Aliberti S, Cosentini R, Lopardo G, Gnoni M, Welte T, Saad M, Guardiola J, Ramirez J. Predicting mortality in hospitalized patients with 2009 H1N1 influenza pneumonia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 15: 542–546, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Robbins CS, Bauer CM, Vujicic N, Gaschler GJ, Lichty BD, Brown EG, Stampfli MR. Cigarette smoke impacts immune inflammatory responses to influenza in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 174: 1342–1351, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Room R. Smoking and drinking as complementary behaviours. Biomed Pharmacother 58: 111–115, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rubinsky AD, Kivlahan DR, Volk RJ, Maynard C, Bradley KA. Estimating risk of alcohol dependence using alcohol screening scores. Drug Alcohol Depend 108: 29–36, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saitz R. Clinical practice. Unhealthy alcohol use. N Engl J Med 352: 596–607, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Samokhvalov AV, Irving HM, Rehm J. Alcohol consumption as a risk factor for pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol Infect 138: 1789–1795, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schall TJ, Bacon K, Toy KJ, Goeddel DV. Selective attraction of monocytes and T lymphocytes of the memory phenotype by cytokine RANTES. Nature 347: 669–671, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schuckit MA. Alcohol-use disorders. Lancet 373: 492–501, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shariatzadeh MR, Huang JQ, Tyrrell GJ, Johnson MM, Marrie TJ. Bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia: a prospective study in Edmonton and neighboring municipalities. Medicine (Baltimore) 84: 147–161, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Srivastava A, Henneke P, Visintin A, Morse SC, Martin V, Watkins C, Paton JC, Wessels MR, Golenbock DT, Malley R. The apoptotic response to pneumolysin is Toll-like receptor 4 dependent and protects against pneumococcal disease. Infect Immun 73: 6479–6487, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Standiford TJ, Danforth JM. Ethanol feeding inhibits proinflammatory cytokine expression from murine alveolar macrophages ex vivo. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 21: 1212–1217, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Strieter RM, Belperio JA, Keane MP. Host innate defenses in the lung: the role of cytokines. Curr Opin Infect Dis 16: 193–198, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sun K, Salmon SL, Lotz SA, Metzger DW. Interleukin-12 promotes gamma interferon-dependent neutrophil recruitment in the lung and improves protection against respiratory Streptococcus pneumoniae infection. Infect Immun 75: 1196–1202, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Suzuki M, Betsuyaku T, Nagai K, Fuke S, Nasuhara Y, Kaga K, Kondo S, Hamamura I, Hata J, Takahashi H, Nishimura M. Decreased airway expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in mice and COPD patients. Inhal Toxicol 20: 349–359, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thaikoottathil JV, Martin RJ, Zdunek J, Weinberger A, Rino JG, Chu HW. Cigarette smoke extract reduces VEGF in primary human airway epithelial cells. Eur Respir J 33: 835–843, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thickett DR, Armstrong L, Millar AB. A role for vascular endothelial growth factor in acute and resolving lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 166: 1332–1337, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van der Poll T, Keogh CV, Buurman WA, Lowry SF. Passive immunization against tumor necrosis factor-alpha impairs host defense during pneumococcal pneumonia in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 155: 603–608, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van der Poll T, Opal SM. Pathogenesis, treatment, and prevention of pneumococcal pneumonia. Lancet 374: 1543–1556, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ward KA, Spokes PJ, McAnulty JM. Case-control study of risk factors for hospitalization caused by pandemic (H1N1) 2009. Emerg Infect Dis 17: 1409–1416, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wilkosz S, Edwards LA, Bielsa S, Hyams C, Taylor A, Davies RJ, Laurent GJ, Chambers RC, Brown JS, Lee YC. Characterization of a new mouse model of empyema and the mechanisms of pleural invasion by Streptococcus pneumoniae. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 46: 180–187, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wright AK, Briles DE, Metzger DW, Gordon SB. Prospects for use of interleukin-12 as a mucosal adjuvant for vaccination of humans to protect against respiratory pneumococcal infection. Vaccine 26: 4893–4903, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wright AK, Christopoulou I, El BS, Limer J, Gordon SB. rhIL-12 as adjuvant augments lung cell cytokine responses to pneumococcal whole cell antigen. Immunobiology 216: 1143–1147, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yamaguchi E, Itoh A, Furuya K, Miyamoto H, Abe S, Kawakami Y. Release of tumor necrosis factor-alpha from human alveolar macrophages is decreased in smokers. Chest 103: 479–483, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yeligar SM, Machida K, Tsukamoto H, Kalra VK. Ethanol augments RANTES/CCL5 expression in rat liver sinusoidal endothelial cells and human endothelial cells via activation of NF-kappa B, HIF-1 alpha, and AP-1. J Immunol 183: 5964–5976, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]