Abstract

The contribution of transient outward current (Ito) to changes in ventricular action potential (AP) repolarization induced by acidosis is unresolved, as is the indirect effect of these changes on calcium handling. To address this issue we measured intracellular pH (pHi), Ito, L-type calcium current (ICa,L), and calcium transients (CaTs) in rabbit ventricular myocytes. Intracellular acidosis [pHi 6.75 with extracellular pH (pHo) 7.4] reduced Ito by ∼50% in myocytes with both high (epicardial) and low (papillary muscle) Ito densities, with little effect on steady-state inactivation and activation. Of the two candidate α-subunits underlying Ito, human (h)Kv4.3 and hKv1.4, only hKv4.3 current was reduced by intracellular acidosis. Extracellular acidosis (pHo 6.5) shifted Ito inactivation toward less negative potentials but had negligible effect on peak current at +60 mV when initiated from −80 mV. The effects of low pHi-induced inhibition of Ito on AP repolarization were much greater in epicardial than papillary muscle myocytes and included slowing of phase 1, attenuation of the notch, and elevation of the plateau. Low pHi increased AP duration in both cell types, with the greatest lengthening occurring in epicardial myocytes. The changes in epicardial AP repolarization induced by intracellular acidosis reduced peak ICa,L, increased net calcium influx via ICa,L, and increased CaT amplitude. In summary, in contrast to low pHo, intracellular acidosis has a marked inhibitory effect on ventricular Ito, perhaps mediated by Kv4.3. By altering the trajectory of the AP repolarization, low pHi has a significant indirect effect on calcium handling, especially evident in epicardial cells.

Keywords: transient outward current, acidosis, excitation-contraction coupling, rabbit ventricular myocytes

transient outward k+ current (Ito) is the major repolarizing current flowing during the early repolarization phase of the cardiac action potential (AP) in a variety of cell types including human and rabbit ventricular myocytes and is largely responsible for phase 1 and the “spike-and-dome” configuration (4, 12, 17, 20, 22, 31, 48). By modulating the initial voltage trajectory of the AP, Ito importantly influences the overall AP waveform through voltage-dependent effects on other ionic currents such as L-type calcium current (ICa,L), Na+/Ca2+ exchange (NCX) current, and delayed rectifier currents (34). In this regard, several studies have shown that inhibition of Ito markedly affects excitation-contraction (E-C) coupling by altering transsarcolemmal Ca2+ flux via ICa,L and NCX, with secondary effects on calcium loading of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) (5, 6, 11, 13, 27, 42, 43, 53).

The expression and magnitude of cardiac Ito are regulated by a variety of factors and conditions including hormones, metabolic inhibition, and hypertrophy/failure with consequent effects on AP configuration (32, 36). In addition, previous work has shown that Ito in rat ventricular myocytes, measured at room temperature, is altered by extracellular acidosis [low extracellular pH (pHo)] (50), intracellular acidosis [low intracellular pH (pHi)] (58, 59), and simultaneous reductions in pHo and pHi (combined acidosis) (24). Low pHo elicits right shifts in inactivation (toward less negative potentials) causing increased Ito at voltages of approximately +50 mV to +60 mV when initiated from depolarized potentials but has little or no effect when initiated from voltages near the normal resting potential (50). In contrast, intracellular acidosis (pHo 7.4), induced by pipette acid loading, is reported to decrease Ito over the voltage range of −30 mV to +60 mV (58, 59). However, pHi was not measured in these reports, and subsequent work has demonstrated that accurate pHi dialysis via a suction pipette is very difficult to achieve, given the high intracellular H+ buffering and low H+ mobility (52, 61). Thus the quantitative relationship between ventricular pHi and Ito remains unresolved. To address this issue, in the present study we measured pHi and Ito at 37°C in rabbit ventricular myocytes, a preparation with a more humanlike AP than rat ventricle, using a more reliable technique for selectively reducing pHi.

Also unresolved is the role of Ito in mediating pH-induced changes in AP repolarization and calcium handling. Using a mixture of rabbit myocytes from the entire left ventricle, we recently reported that a selective reduction in pHi (pHo 7.4) slowed the rate of phase 1 repolarization, reduced the notch, elevated the AP plateau, and prolonged AP duration (APD). These AP changes are consistent with Ito inhibition and may indirectly contribute to the effects of low pHi on ventricular E-C coupling. However, because Ito exhibits a large transmural density gradient (epicardial > endocardial) (4, 9, 17, 18, 31), our use of a mixture of cells from the entire left ventricle meant that phase 1 and the notch varied considerably from one cell to another. Thus it remains unclear how pHi-induced changes in Ito modulate the AP, ICa,L, and the calcium transient (CaT). Here we address this question in rabbit ventricular myocytes displaying both high [epicardial (Epi)] and low [papillary muscle (PM)] Ito densities, using AP voltage clamps and fluo-4 fluorescence.

Collectively the results demonstrate that intracellular acidosis markedly reduces ventricular Ito, which significantly contributes to the accompanying changes in early AP repolarization, resulting in indirect modulation of E-C coupling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Myocyte Isolation

The experiments were performed on left ventricular myocytes isolated from adult rabbits of both sexes by enzymatic digestion. To minimize transmural differences in ICa,L density (37), only male rabbits were used for the measurements of ICa,L and CaTs. All procedures involving animals were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Utah and complied with the American Physiological Society's “Guiding Principles for the Care and Use of Vertebrate Animals in Research and Training.” Rabbits were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg iv), and the excised heart was attached to an aortic cannula and perfused with solutions gassed with 100% O2 and held at 37°C, pH 7.3. The heart was first perfused for 5 min with a Ca2+-free solution at 37°C containing (in mM) 92.0 NaCl, 4.4 KCl, 11.0 dextrose, 5.0 MgCl2, 20.0 taurine, 5.0 creatine, 5.0 sodium pyruvate, 1.0 NaH2PO4, 24.0 HEPES, and 12.5 NaOH (pH 7.3). This was followed by 15 min of recirculation with the same solution containing 0.15 mg/ml collagenase P (Roche Diagnostic, Mannheim, Germany), 0.05 mg/ml protease (type XIV, Sigma Chemical), and 0.05 mM CaCl2. The heart was then perfused for 5 min with the same solution containing no enzymes. The ventricle was isolated and minced, shaken for 10 min, and then filtered through a nylon mesh. Cells were stored at room temperature in the normal control bathing solution. To obtain cells with both low and high Ito densities, myocytes were isolated from both PMs and the epicardial layers (Epi) of the left ventricle, respectively (17). All cells used in this study were rectangular, had well-defined striations, and did not spontaneously contract. All experiments were conducted within 10 h of isolation.

Cell Culture

Human embryonic kidney cells (HEK 293T) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, l-glutamine (2 mM), penicillin (100 IU/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). HEK 293T cells were plated onto 35-mm culture dishes and transfected with human (h)Kv1.4 (pcDNA3) along with green fluorescent protein (pEGFP) or hKv4.3 (pIRES-GFP) with Lipofectamine (Invitrogen). Experiments were conducted 1–2 days after transfection.

Cell Superfusion Chamber

Isolated ventricular cells were superfused at 4 ml/min (37 ± 0.3°C), solution exchange within the experimental chamber occurring in ∼5 s. The glass bottom of the chamber was coated with laminin (Collaborative Research, Bedford, MA) to improve cell adhesion. HEK 293T cells were bathed in solution at 23 ± 1.0°C without laminin coating the bottom of the bath.

Bathing Solutions and Drugs

Two types of acidosis were applied to myocytes: extracellular acidosis (pHo 6.5, pHi ∼7.1) and intracellular acidosis (pHo 7.4, pHi ∼6.7) as previously described (41). The normal control solution for extracellular acidosis (low pHo) and intracellular acidosis (low pHi) contained (mM) 126.0 NaCl, 11.0 dextrose, 4.4 KCl, 1.0 MgCl2, 1.08 CaCl2, and 24.0 HEPES titrated to pH 7.4 with 1 M NaOH. During acidosis experiments all bathing solutions contained 30 μM cariporide (Sanofi-Aventis, Frankfurt, Germany) to selectively block sodium/hydrogen exchange (NHE) and no added CO2 or HCO3− to block transsarcolemmal transport of acid equivalents via Na+-HCO3− cotransport (NBC) (60) and Cl−/HCO3− exchange (57). The solution used to create extracellular acidosis had the same composition as the control solution except that its pH was titrated to 6.5 with NaOH. In separate experiments we found that 30 μM cariporide had no effect on Ito (n = 5, data not shown) or ICa,L (41).

The solution used to induce intracellular acidosis with pHo held at 7.4 was prepared by equimolar replacement of 80.0 mM sodium acetate (NaAc) in the control solution for NaCl, as recently described (41). Decreasing pHi by application of extracellular acetate is a widely used technique and results from rapid influx of uncharged protonated acetate, which then releases protons intracellularly. To compensate for the decrease in Ca2+ activity in the bathing solution due to acetate binding, CaCl2 was increased in the 80 mM acetate solution from 1.08 mM to 1.37 mM (41). The bathing solutions for HEK cells had the same composition as those for myocytes except that 40 mM NaAc was used to induce intracellular acidosis.

During several voltage-clamp protocols, ICa,L and the inward-rectifying potassium current (IK1) were blocked by CdCl2 (200 μM; Sigma-Aldrich) and BaCl2 (200 μM; Sigma-Aldrich), respectively. Sodium current (INa) was inhibited in some experiments by equimolar replacement of NaCl with N-methyl-d-glucamine, and pHo was adjusted to 7.4 with HCl. In this case CaCl2 was reduced to 0.1 mM to retard calcium overload upon exposure to sodium-free solution. Ito and the rapid delayed-rectifier potassium current (IKr) were inhibited in some experiments by including 3 mM 4-aminopyridine (Sigma-Aldrich) and 2 μM E-4031 (Sigma-Aldrich), respectively. In contrast to a previous report (47), BaCl2 (200 μM) had no effect on Ito (n = 4, data not shown). To measure ICa,L, potassium chloride was replaced with 4.4 mM CsCl in the control solutions. A mixture of 10 μM nifedipine (Sigma-Aldrich) and 200 μM CdCl2 was used to block ICa,L for ICa,L voltage-clamp experiments.

Pipette Filling Solutions

The normal filling solution used for recording APs in myocytes contained (in mM) 110.0 K-gluconate, 10.0 KCl, 5.0 Na-glucuronate, 5.0 MgATP, 5.0 phosphocreatine, 1.0 NaGTP, and 10.0 HEPES titrated to pH 7.2 with 1 M KOH. This solution was also used when recording CaTs that were initiated with AP voltage clamps (AP clamp), without simultaneous measurement of ICa,L. The filling solution used to measure Ito in myocytes and HEK 293T cells expressing Kv4.3 and Kv1.4 had the same composition as the normal filling solution except that it also contained 5.0 mM BAPTA. Corrections were made for liquid junction potentials. Buffering intracellular calcium with BAPTA eliminates Ca2+-activated Cl− current, also known as Ito2, which is present in rabbit ventricular myocytes (22) and activated by extracellular acidosis (23). Intracellular BAPTA also blocks the CaT and thus minimizes the complicating effects of Ca2+-activated NCX (7). BAPTA is preferable to EGTA because of its faster Ca2+ binding kinetics and lower pH sensitivity (51).

The pipette filling solution used for ICa,L voltage-clamp experiments (rectangular voltage steps and AP clamps) contained (in mM) 120.0 CsCl, 5.0 NaCl, 10.0 tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA-Cl), 5.0 MgATP, 5.0 phosphocreatine, 1.0 NaGTP, 5.0 BAPTA, and 10.0 HEPES titrated to pH 7.2 with 1 M CsOH. Corrections were made for liquid junction potentials. BAPTA was not present in experiments in which ICa,L and CaTs were simultaneously recorded (see Table 2) and when only CaTs were recorded during AP clamps (see Fig. 12).

Table 2.

Effect of AP repolarization on simultaneously measured ICa,L and CaTs

| Epi Template (n = 5) |

PM Template (n = 5) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Intracellular acidosis | Control | Intracellular acidosis | |

| Initial peak ICa,L, pA/pF | −7.64 ± 0.59 | −5.35 ± 0.70** | −4.24 ± 0.14## | −3.91 ± 0.14* |

| Net Ca2+ influx via ICa,L, pC/pF | 0.31 ± 0.03 | 0.40 ± 0.05* | 0.23 ± 0.02 | 0.27 ± 0.03* |

| CaT amplitude (F/F0) | 1.95 ± 0.23 | 2.09 ± 0.23** | 1.53 ± 0.07 | 1.55 ± 0.06 |

| Rate of rise, F/F0/s | 51.8 ± 16.4 | 65.2 ± 14.4* | 32.4 ± 6.55 | 33.3 ± 2.49 |

| E-C coupling gain, (F/F0/s)/(pA/pF) | 7.36 ± 2.66 | 13.8 ± 4.22* | 7.69 ± 1.60 | 8.58 ± 0.79 |

All values are means ± SE. All experiments were performed in the absence of acidosis with appropriate action potential (AP) templates for control and intracellular acidosis. ICa,L, L-type calcium current; CaT, calcium transient; Epi, epicardial; PM, papillary muscle; F/F0, ratio of fluorescence during CaT divided by diastolic fluorescence; E-C, excitation-contraction.

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01 vs. control, paired; ##P < 0.01 vs. control with Epi template, unpaired.

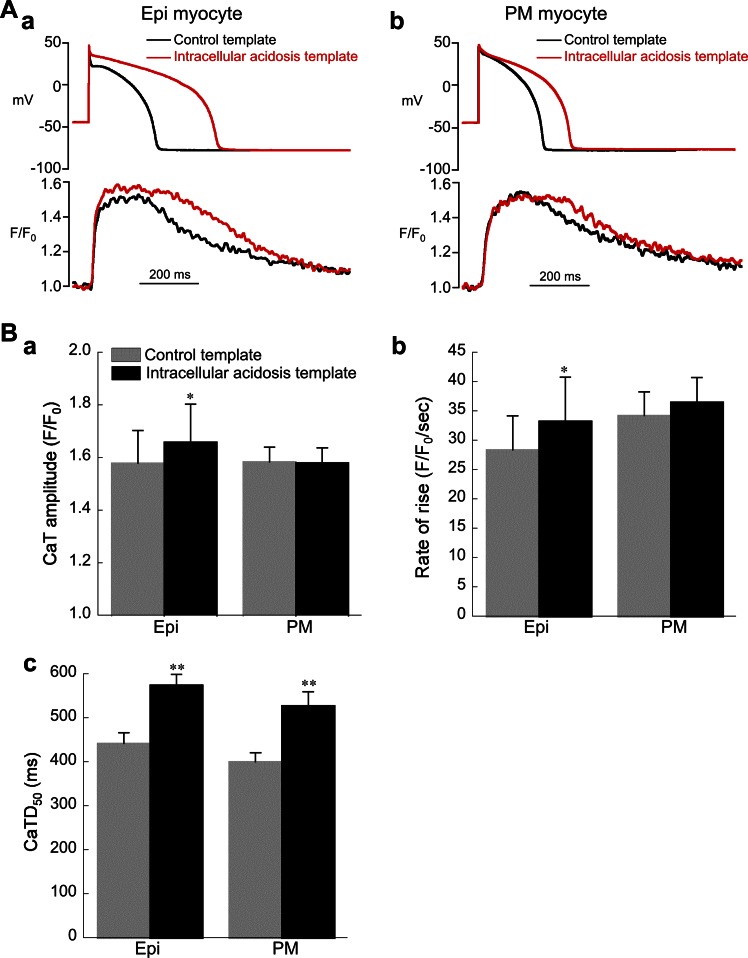

Fig. 12.

Response of calcium transients (CaTs) in Epi and PM myocytes to changes in AP repolarization induced by intracellular acidosis (80.0 mM acetate). Control bathing solution was used for all experiments shown in this figure. A: examples of CaTs elicited by AP clamps using control and acidosis templates in Epi (a) and PM (b) myocytes. B: summary of results for amplitude (a), maximum rate of rise (b), and duration (c) of CaTs (Epi, n = 8; PM, n = 10). The acidosis template increased amplitude and maximum rate of rise of the CaT in Epi but not PM cells. The acidosis template increased CaT duration [measured as time from upstroke to 50% recovery (CaTD50)] in both cell types. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, paired, control vs. acidosis template. CL = 2 s was used for all experiments shown in this figure.

Intracellular acidosis (pHo 7.4) was induced in some experiments with pipette acid loading. The filling solution contained (mM) 110.0 KCl, 5.0 NaCl, 5.0 MgATP, 5.0 phosphocreatine, 1.0 NaGTP, and 10.0 HEPES titrated to pH 6.6 with 1 M KOH.

Electrophysiological Techniques

All electrophysiological measurements in both myocytes and HEK 293T cells were made with whole cell ruptured patch pipettes. Pipettes (Corning 8250 glass) for myocytes and HEK 293T cells had resistances of 1–2 MΩ and 2.5–4.0 MΩ, respectively, when filled. Myocyte APs were recorded with an Axoclamp-2A amplifier system (Axon Instruments) in bridge mode, and voltage clamping (step clamps and AP clamps) was achieved with an Axopatch 200B clamp system using a CV203BU headstage. APs were triggered with brief (2–3 ms) square pulses of depolarizing intracellular current (∼2 nA), and APD was measured at 90% repolarization (APD90). Membrane potential (Vm) and membrane current (Ito and ICa,L) were filtered at 5 kHz, digitized at 50 kHz with a 16-bit A/D converter (Digidata 1322A), and analyzed with pCLAMP 8 software (Molecular Devices). The reference electrode was a flowing 3 M KCl bridge. Compensation for series resistance (75–80%) and capacitance were performed electronically. Membrane currents were normalized for cell capacitance (pA/pF).

Current-voltage (I-V) relationships for Ito were determined by applying test pulses from −40 mV to +60 mV (400-ms duration) at a cycle length (CL) of 5 s. Typically, each test pulse was preceded by a prestep from a holding potential of −80 mV to −40 mV (duration 40 ms) to inactivate sodium current. Zero-sodium bathing solution was used in some experiments to block sodium current. For each test pulse the amplitude of Ito was measured as the difference between peak outward current and the current level at the end of the depolarizing clamp pulse. This clamp protocol was applied first in the control solution and then after 2 min in the acidic test solution. Each cell was exposed only once to an acidic test solution.

I-V relationships for ICa,L in myocytes were determined with the same protocol (CL = 5 s). At the end of the experiment the protocol was repeated in the presence of 200 μM CdCl2 and 10 μM nifedipine to correct for background current.

I-V relationships for hKv4.3 and hKv1.4 expressed in HEK 293T cells were determined by holding the cell at a potential of −80 mV and applying test pulses from −40 mV to +60 mV (500-ms duration) at CL of 5 s and 30 s, respectively, and the clamp protocol was applied first in the control solution and then after 1 min in the acidic test solution.

The steady-state voltage dependence of Ito activation in myocytes was determined with results obtained from the I-V curve clamp protocol. Relative conductance (G/Gmax) was calculated as G = Ito/(Vm − Vrev), where Vm is the clamp potential and Vrev is the estimated reversal potential (−76 mV was used as the estimated reversal potential, Vrev was calculated by Nernst equation and liquid junction potential). The relationship was fit to a Boltzmann function, and Gmax was estimated by extrapolation of the curve to more positive potential. The resulting normalized G-V relationships were again fit with a Boltzmann function: G/Gmax = 1/{1 + exp[(Vm − V1/2)/k]}, where V1/2 and k are the half-maximal activation potential and the slope (mV) of the curve, respectively.

The steady-state voltage dependence of Ito inactivation in myocytes was determined with a double-pulse protocol. Conditioning clamp pulses ranging from −80 mV to 0 mV (500-ms duration) were initiated from a holding potential of −80 mV at a CL of 5 s. At the end of each conditioning pulse Vm was stepped to −40 mV for 10 ms before application of the test pulse to +60 mV. ICa,L is negligible at +60 mV and thus is unlikely to contaminate measurements of Ito (41). Peak currents elicited by the test pulses were normalized as Ito/Ito,max and plotted as a function of conditioning Vm. The curves were fit with a Boltzmann function: Ito/Ito,max = 1/{1 + exp[(Vm − V1/2)/k]}, where Vm is the conditioning voltage, and V1/2 and k are the half-maximal inactivation potential and the slope (mV) of the curve, respectively.

The clamp protocol for quantifying the time course of Ito inactivation was the same as that used to generate I-V curves. With Clampfit software, the time course of inactivation of Ito was fit with a double-exponential function as previously described (22, 45) according to

| (1) |

where I is the current (pA/pF) at time t (ms), Af (pA/pF) and As (pA/pF), respectively, are the amplitudes of fast and slow components, τf and τs, respectively, are the fast and slow inactivation time constants (ms), and C is the current remaining at the end of the clamp step (pA/pF).

The time course of recovery from Ito inactivation was determined with a double-pulse protocol at a CL of 10 s. A conditioning clamp pulse (P1) to +60 mV (400-ms duration) was applied from a holding potential of −80 mV, followed at a variable interval ranging from 100 ms to 5 s by the test pulse (P2) of 400-ms duration to +60 mV. All experiments were performed without Cd2+. Sodium-free bathing solution was used to block INa in the extracellular acidosis experiments. For the intracellular acidosis experiments, INa was inactivated by application of a prepulse from −80 mV to −40 mV (duration 40 ms) before clamping to +60 mV. The recovery from inactivation of Ito was fit with a single exponential as previously described (45) according to

| (2) |

where I is the current (pA/pF) at time t (ms), A (pA/pF) is the amplitude, and C is the current remaining at the end of the clamp step (pA/pF).

Action Potential Voltage Clamps

AP voltage-clamp experiments (AP clamp) were performed to assess the effects of intracellular acidosis on Ito under more physiological conditions than with rectangular clamp pulses. The bathing and pipette solutions used for these experiments were the same as those used to generate the I-V curve, except that all of the bathing solutions also contained 2 μM E-4031 to block IKr. AP templates (control and intracellular acidosis) were made from representative records obtained during current-clamp experiments. Each AP clamp was preceded by a prestep from −80 mV to −40 mV (40-ms duration) at a CL of 5 or 2 s. A train of 10 conditioning clamps was first applied in the control solution with the control AP template. They were then repeated after 2 min in the test solution with the intracellular acidosis AP template. The entire protocol was then repeated in the presence of 3 mM 4-aminopyridine to block Ito. The difference current was used to determine Ito flowing during the AP.

A very similar protocol was used to measure ICa,L in Epi and PM myocytes during AP clamps. AP templates (control and intracellular acidosis) were made from representative records obtained during current-clamp experiments. All measurements were performed in the control bathing solution. Ten conditioning AP clamp pulses were applied to the cells prior to the test clamp to ensure steady-state loading of SR Ca2+ when ICa,L and CaTs were recorded simultaneously (see Table 2) and when only CaTs were recorded (see Fig. 12). The control AP template served as the conditioning pulse for the control test clamp, and the intracellular acidosis AP template served as the conditioning pulse for the acidosis test clamp. The entire protocol was then repeated in the presence of 200 μM CdCl2 and 10 μM nifedipine to correct for background current.

Measurement of Intracellular pH

pHi was measured in single resting myocytes and HEK 293T cells with carboxy-seminaphthorhodafluor-1 (carboxy-SNARF-1), as previously described (2).

Measurement of Intracellular Calcium

CaTs were detected in single myocytes with a similar epifluorescence system using the fluorescent indicator fluo-4. Cells were incubated in the normal control solution containing 10 μM fluo-4 AM (Molecular Probes) and 0.3 mM probenicid at 25°C for 15 min. They were then continuously bathed in the same solution containing no indicator. Probenicid (0.3 mM) was included in the bathing solutions to help retard fluo-4 loss from the cells. Fluorescence emission (535 ± 11 nm, band-pass filter) was collected with a photomultiplier tube via the ×40 oil objective (numerical aperture 1.3) during continuous excitation at 485 nm with a 150-W xenon lamp. Fluorescence signals were background corrected and expressed as F/F0 (the ratio of fluorescence during the CaT divided by diastolic fluorescence). CaT duration was measured as the time from the upstroke to 50% recovery (CaTD50). CaTs were elicited with AP clamps (CL = 2 s) during superfusion with the normal bathing solution, using the appropriate AP templates for control and intracellular acidosis. A train of at least 10 conditioning clamps was applied to the cells to achieve steady-state Ca2+ loading of the SR. The normal pipette filling solution was used (no Cs+, no BAPTA) when only CaTs were measured. For experiments in which CaTs and ICa,L were simultaneously recorded, K+ in the bathing solution was replaced with Cs+ and the pipette filling solution was the normal solution used for ICa,L measurements except that it did not contain BAPTA. The gain of E-C coupling was calculated as the maximum rate of rise of the CaT divided by the simultaneously recorded peak ICa,L, as previously described (16).

Statistics

Summarized results are expressed as means ± SE. A paired Student's t-test was used to test significance between results obtained with each cell serving as its own control. An unpaired t-test was used to test significance between two different groups of cells. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

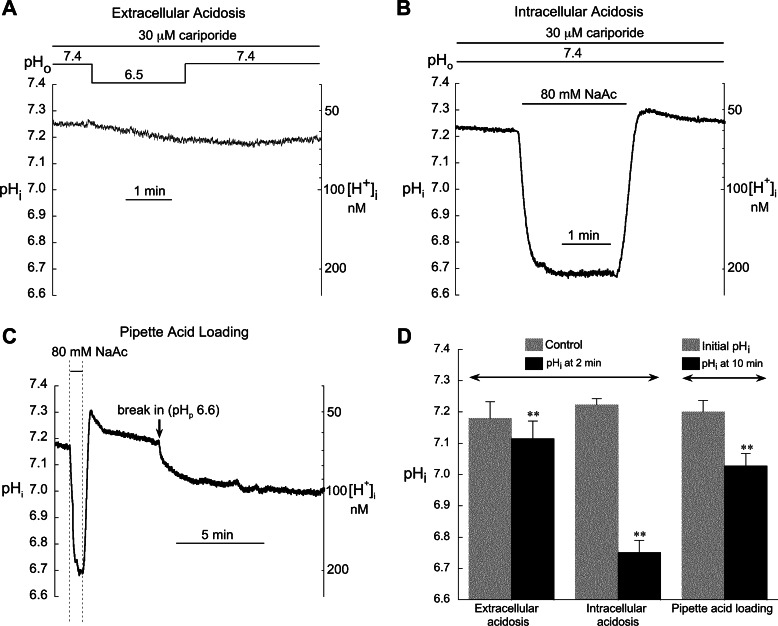

Changes in pHi During Extra- and Intracellular Acidosis

Figure 1, A and B, illustrate the changes in pHi in rabbit ventricular myocytes resulting from 2 min of extracellular and intracellular acidosis, respectively. HCO3−-dependent transporter activity was minimized by superfusing with CO2/HCO3−-free solution, while NHE activity was blocked with 30 μM cariporide. As we have previously shown in rabbit ventricular myocytes (41), 2 min of low pHo caused negligible changes in pHi, reducing it by only ∼0.05 units (Fig. 1, A and D). In contrast, intracellular acidosis induced by superfusion with 80.0 mM acetate (pHo 7.4) for 2 min markedly reduced pHi by 0.47 units from a mean value of 7.22 ± 0.02 to 6.75 ± 0.04 (n = 17; Ref. 41). We have also found that pHi is unaffected by attachment with a suction pipette filled with the normal solution (pHpipette = 7.2; Ref. 41). The 2-min acidosis protocol was used for both types of acidosis in all subsequent myocyte experiments.

Fig. 1.

Changes in intracellular pH (pHi) and intracellular H+ concentration ([H+]i) induced by extra- and intracellular acidosis and by pipette acid loading. A: a reduction in extracellular pH (pHo) from 7.4 to 6.5 for 2 min elicited only a small drop in pHi. B: in contrast, exposure to 80.0 mM acetate (pHo 7.4) induced a rapid sustained fall in pHi. C: example record showing the marked difference between intracellular acidosis (pHo 7.4) induced with 80 mM acetate and with pipette dialysis [pipette pH (pHp) = 6.6]. D: summarized results for extracellular acidosis (n = 7), intracellular acidosis (n = 17), and pipette acid loading (n = 4). We previously reported the summarized results shown in D for extra- and intracellular acidosis (41). The example records in A and B have not been previously published. All results shown here were obtained from a mixture of cells from all regions of the left ventricle. **P < 0.01 paired, control vs. acidosis. In separate experiments, we found no significant difference between the drop in pHi induced by 80.0 mM acetate (pHo 7.4) in epicardial (Epi, n = 4) and papillary muscle (PM, n = 7) myocytes (data not shown).

Several earlier studies used pipette acid loading to induce intracellular acidosis in cardiac myocytes, on the assumption that pHi equilibrates with the pH of the pipette filling solution (25, 29, 58, 59). However, these studies did not include measurements of pHi. Figure 1C shows that 10 min of intracellular dialysis with a pipette pH of 6.6 induced a fall in the measured pHi of only 0.17 units, from 7.20 ± 0.04 to 7.03 ± 0.04 (n = 4). When expressed as change in intracellular H+ concentration ([H+]i), this represents an ∼1.5× increase compared with 3.1× increase induced by the 80.0 mM acetate pulse. Thus, assuming that pHi = pHpipette will seriously overestimate the degree of intracellular acidosis and emphasizes the importance of measuring pHi as we have done in the present study.

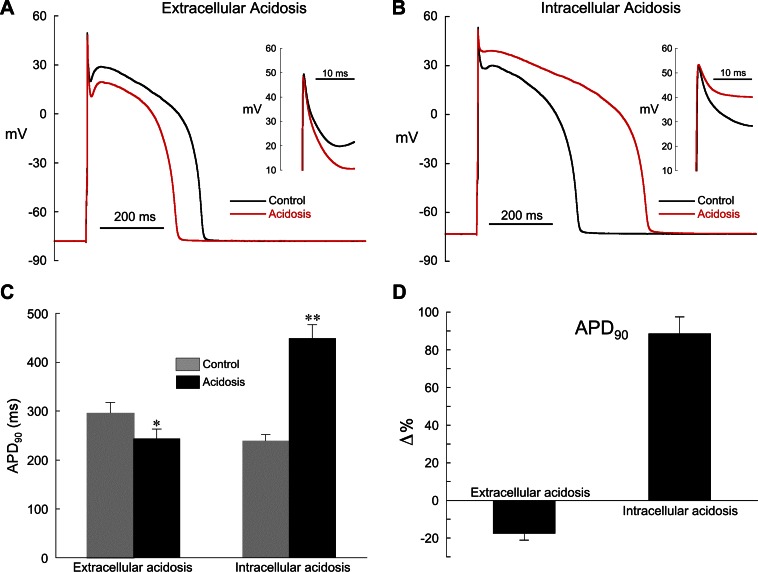

Effect of Acidosis on Action Potential Repolarization in Epicardial Myocytes

Because we used myocytes from all regions of the left ventricle in our previous study of pH effects on AP repolarization, there were large cell-to-cell differences in phase 1 and the notch (41). In this series of experiments we focused on the AP response of Epi myocytes to extracellular and intracellular acidosis. As shown in Fig. 2, epicardial APs display a prominent phase 1 repolarization and notch, mediated primarily by the high density of Ito displayed in this cell type (17).

Fig. 2.

Effect of extra- and intracellular acidosis on epicardial action potentials (APs). A: extracellular acidosis (pHo 6.5) shortened AP duration (APD). Inset: expanded view of phase 1 repolarization. B: intracellular acidosis (80.0 mM acetate) prolonged APD, markedly slowed phase 1 repolarization, and nearly eliminated the notch. Inset: expanded view of phase 1 repolarization. C: summarized changes in APD at 90% repolarization (APD90) in low pHo (n = 5) and low pHi (n = 11). D: changes (Δ) in APD90 shown in C expressed as % relative to control. The normal pipette filling solution was used in these experiments (no BAPTA). Pacing cycle length (CL) for all experiments was 2 s. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, paired, control vs. acidosis.

In response to 2 min of extracellular acidosis, the plateau was depressed and APD was shortened but the notch was largely unaffected (Fig. 2, A, C, and D). The resting membrane potential (CL = 2 s) was slightly depolarized by extracellular acidosis (control = −87.1 ± 2.5 mV, acidosis = −83.8 ± 2.7 mV; n = 5, P < 0.05, paired). The effects of extracellular acidosis on cardiac AP configuration are complex, with reports of inhibition of the rapid delayed-rectifier current IKr (8), ICa,L (8, 41), and both peak and persistent sodium current (30). In addition, we have recently shown that the changes in rabbit ventricular repolarization induced by low pHo are largely mediated by a reduction in ICa,L and are unlikely to involve Ito (41).

In contrast, intracellular acidosis markedly slowed phase 1 repolarization, reduced the notch, elevated the plateau, and prolonged APD (Fig. 2, B–D; pacing CL = 2 s). The percent change in APD90 induced by low pHi at CL = 2 s (+88.5 ± 9.0%, n = 11) was not significantly different from that at CL = 5 s (+86.2 ± 21.0%, n = 4). The resting membrane potential (CL = 2 s) was slightly depolarized by low pHi (control = −81.0 ± 1.0 mV, acidosis = −79.0 ± 1.5 mV; n = 11 P < 0.05, paired), but the overshoot did not change (control = 45.7 ± 1.2 mV, acidosis 45.3 ± 1.3 mV; n = 11).

We also preformed AP measurements (CL = 2s) with 10 mM BAPTA in the suction pipette to minimize Ca2+-activated Cl− current (ICl,Ca). This concentration of BAPTA blocks CaTs and the rise in diastolic calcium induced by lowering pHi (41). With BAPTA dialysis the changes in AP repolarization during both types of acidosis were qualitatively the same as those without BAPTA and included AP shortening in low pHo and AP lengthening in low pHi, suggesting that changes in ICl,Ca did not play a major role [intracellular acidosis: control APD90 = 414 ± 25 ms, acidosis APD90 = 922 ± 36 ms (n = 2, P < 0.02, paired); extracellular acidosis: control APD90 = 585 ± 50 ms, acidosis APD90 = 519 ± 53 ms (n = 3, P < 0.05, paired)].

Numerous studies have demonstrated that Ito inhibition slows phase 1 repolarization, elevates the plateau, and reduces the notch (4, 17, 18, 39). Thus the results in Fig. 2 strongly suggest that the Ito activated during APs is inhibited by intracellular acidosis but largely unaffected by extracellular acidosis.

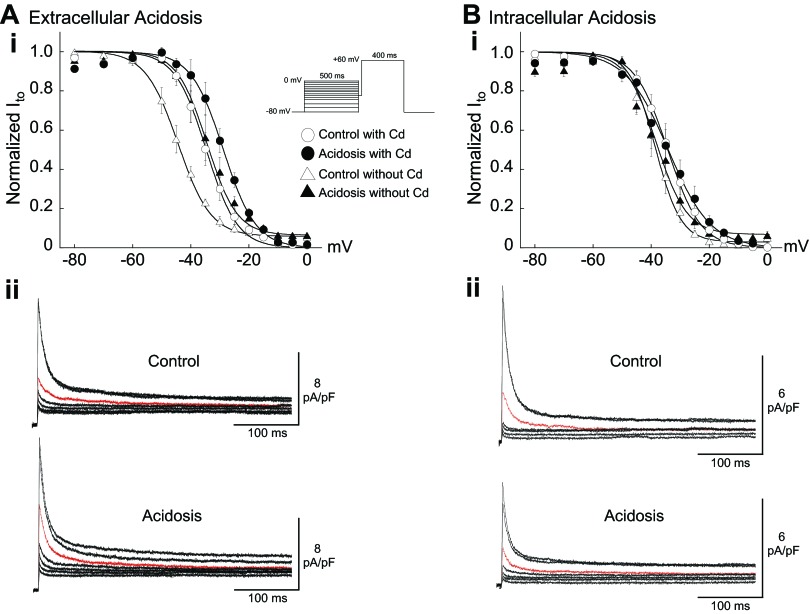

Effect of Acidosis and Cadmium on Steady-State Voltage Dependence of Ito Inactivation

In this series of experiments we examined the separate actions of extra- and intracellular acidosis on the voltage dependence of Ito inactivation in Epi myocytes (Fig. 3). We also assessed the effect of Cd2+ on inactivation since it was used in other protocols to block ICa,L. After each 500-ms-duration conditioning step, Vm was clamped to +60 mV, which is near the peak of the typical rabbit ventricular AP (Fig. 1) and activates a large Ito with minimal contamination by ICa,L.

Fig. 3.

Effect of acidosis and Cd2+ (200 μM) on the steady-state voltage dependence of transient outward current (Ito) inactivation in Epi myocytes. Ai: extracellular acidosis (pHo 6.5) without Cd2+ induced a right shift in inactivation (n = 4). Cd2+ right-shifted inactivation and reduced the shift induced by extracellular acidosis (n = 4). Aii: control and acidosis signals from the same cell (no Cd2+). Red signals clamped from −40 mV. Bi: intracellular acidosis (80.0 mM acetate) with (n = 5) or without (n = 4) Cd2+ had no significant effect on the voltage dependence of inactivation. Bii: control and acidosis signals from the same cell (no Cd2+). Red signals clamped from −40 mV. Smooth lines are best fits with Boltzmann functions (materials and methods). Inset: clamp protocol. The results in this figure are summarized in Table 1. Pacing CL = 5 s.

Previous work with rat ventricular myocytes, measured at room temperature, reported that both extracellular acidosis (50) and simultaneous reductions in pHo and pHi (24) induced right shifts in the voltage dependence of Ito inactivation. Our results, measured at 37°C without Cd2+ or dihydropyridine Ca2+ channel blockers, confirm that extracellular acidosis (pHo 6.5) has the same effect in rabbit epicardial ventricular myocytes, shifting the inactivation V1/2 by ∼10 mV (Fig. 3A; Table 1, no Cd2+). The same result was also obtained in rabbit cells bathed in sodium-free solution containing no Cd2+ (Table 1). In accord with earlier work in rat and rabbit myocytes (1, 50, 55), we also found that Cd2+ (200 μM) right-shifted the voltage dependence of Ito inactivation (Fig. 3A; Table 1, compare control no Cd2+ with control 200 μM Cd2+). In addition, the H+-induced right shift was less in the presence of Cd2+ (Fig. 3A), as also observed in rat ventricular myocytes (50).

Table 1.

Effect of acidosis and Cd2+ on Ito steady-state inactivation parameters

| 200 mM Cd2+ |

No Cd2+ |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extracellular acidosis (n = 4) | Intracellular acidosis (n = 5) | Extracellular acidosis (n = 4) | Intracellular acidosis (n = 4) | No Na+, No Cd2+ Extracellular Acidosis (n = 5) | |

| Control V1/2, mV | −34.6 ± 1.8 | −34.3 ± 1.8 | −44.4 ± 1.6 | −38.6 ± 2.1 | −43.5 ± 0.4 |

| Acidosis V1/2, mV | −28.7 ± 1.6** | −34.4 ± 2.4 | −34.5 ± 2.5** | −38.2 ± 1.6 | −29.2 ± 1.4** |

| Control slope k | 5.4 ± 0.3 | 5.7 ± 0.3 | 5.6 ± 0.7 | 4.4 ± 0.2 | 10.3 ± 0.5 |

| Acidosis slope k | 5.6 ± 0.2 | 7.1 ± 0.4 | 5.1 ± 0.4 | 5.3 ± 0.5 | 8.8 ± 0.4* |

Values are mean ± SE half-maximal inactivation potential (V1/2) and k determined from best fits of Boltzmann functions. Ito, transient outward current.

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01 vs. control, paired.

In striking contrast to low pHo, intracellular acidosis had no significant effect on the voltage dependence of Ito inactivation with or without Cd2+ in the bathing solution (Fig. 3B; Table 1). This indicates that Cd2+ can be used to block ICa,L in order to study the effects of changes in pHi on the steady-state gating properties of Ito. Importantly, it also suggests that low pHi does not affect steady-state inactivation of Ito. This lack of effect has been reported for rat ventricular myocytes measured at room temperature (58, 59). However, pipette acid loading was used in that study to induce intracellular acidosis without measuring pHi, which our results demonstrate (Fig. 1, C and D) is not a reliable method for inducing quantitative changes in pHi.

Influence of Voltage Clamp Prestep and Cd2+ on Response of Ito Activation to Acidosis

It is necessary to block the contaminating effects of ICa,L and INa when assessing the response of Ito activation to acidosis. ICa,L can be blocked with Cd2+, and INa is readily inactivated by applying a 40-ms prestep from −80 mV to −40 mV. Here we assess the use of these two approaches for studying the effects of acidosis on Ito activation.

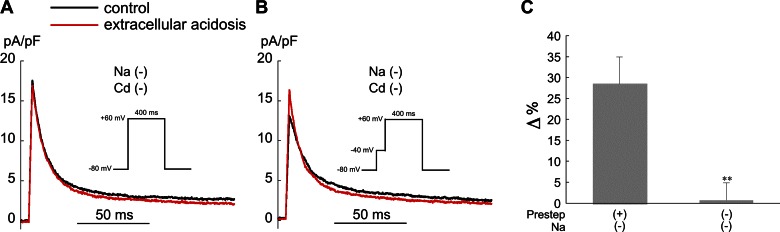

Low pHo.

The action of both low pHo and external Cd2+ to right-shift Ito inactivation makes it difficult to accurately assess the voltage dependence of Ito activation during extracellular acidosis with Cd2+ present. To avoid using Cd2+, we examined the effect of low pHo on Ito activation in Epi myocytes clamped to +60 mV, which, as noted above, is near the peak of the AP and is a voltage at which ICa,L is negligible (41). To assess the effects of a prestep on Ito activation, we used sodium-free solutions to block INa. Figure 4A shows that extracellular acidosis had no effect on Ito in the absence of external sodium, external Cd2+, and a prestep. In contrast, when the prestep was included Ito increased during low pHo (Fig. 4B), presumably because of increased channel availability at −40 mV (Fig. 3A). The results are summarized in Fig. 4C. Thus inclusion of even a brief prestep will introduce errors in the measurement of Ito activation during extracellular acidosis.

Fig. 4.

Effect of a voltage clamp prestep on the response of Ito activation to extracellular acidosis (pHo 6.5) in Epi myocytes. A: example experiment showing that, without a prestep to −40 mV, low pHo has no effect on Ito activated by a voltage clamp step from −80 mV to +60 mV. B: example experiment (same cell as A) showing that low pHo increased Ito when a 40-ms-duration prestep from −80 mV to −40 mV was included. C: summary of the results, expressed as % change in Ito relative to control with and without the prestep (n = 4). All experiments in this figure were performed in sodium- and Cd2+-free solution. Pacing CL = 5 s. **P < 0.01 paired, with vs. without prestep.

Most importantly, these results suggest that extracellular acidosis does not significantly affect Ito in rabbit epicardial ventricular APs when they are initiated from normal resting potentials and have normal overshoots. In most subsequent experiments we focused on intracellular acidosis.

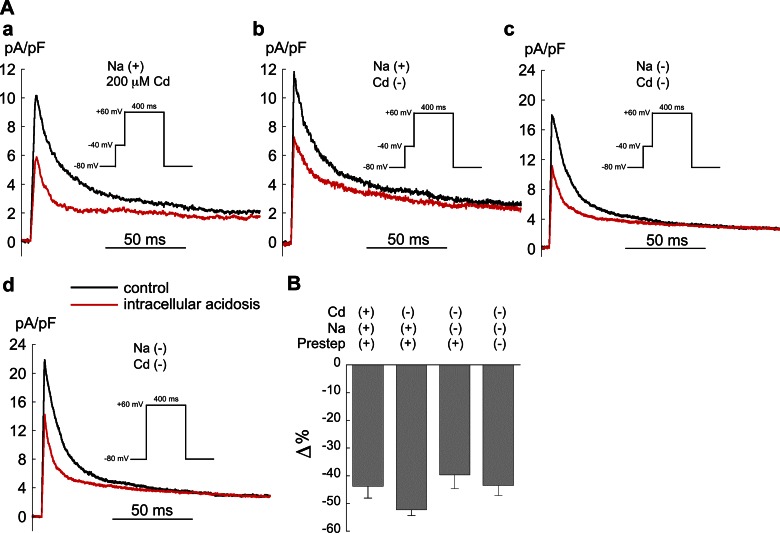

Low pHi.

In the next series of experiments we examined the effect of Cd2+ (200 μM) and the 40-ms prestep to −40 mV on Ito activation in Epi myocytes during intracellular acidosis (Fig. 5). As in Fig. 4, the cells were clamped from a holding potential of −80 mV to +60 mV to minimize ICa,L. Intracellular acidosis markedly reduced Ito in each of the four conditions: Na+ plus Cd2+ (Fig. 5Aa); Na+, no Cd2+ (Fig. 5Ab); no Na+, no Cd2+ (Fig. 5Ac); and no Na+, no Cd2+, and no prestep (Fig. 5Ad). The results are summarized in Fig. 5B and show that neither the presence of Cd2+ nor the prestep significantly affected the action of low pHi to reduce Ito.

Fig. 5.

Effect of a voltage clamp prestep and Cd2+ (200 μM) on the response of Ito activation to intracellular acidosis (80.0 mM acetate) in Epi myocytes. A: example experiment showing that, in the presence of the 40-ms prestep and normal external sodium, low pHi reduced Ito both with (a) and without (b) the presence of Cd2+ and example signals from a cell showing that, in sodium- and Cd2+-free solution, low pHi reduced Ito both with (c) and without (d) the 40-ms prestep. B: summary of results, expressed as % change in Ito relative to control. There were no significant differences among these groups (ANOVA); n = 9 with prestep, normal sodium, and Cd2+; n = 4 with prestep, normal sodium, no Cd2+; n = 4 with prestep, no sodium, no Cd2+; n = 4 with no prestep, no sodium, no Cd2+. Pacing CL = 5 s.

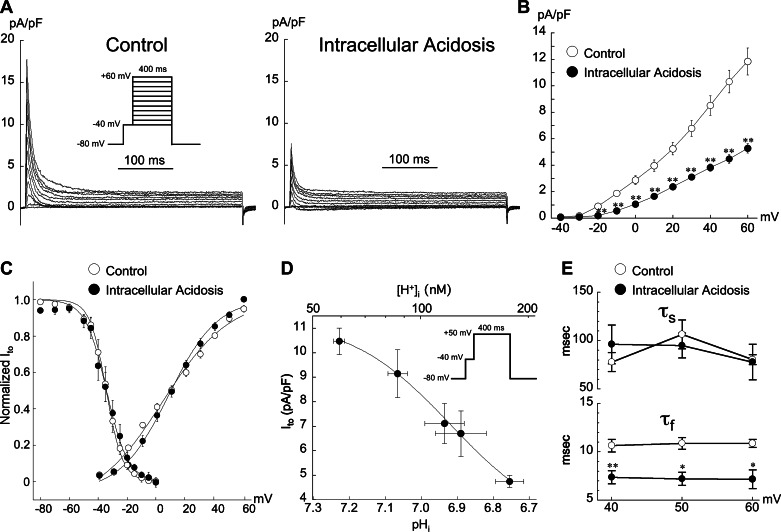

Effect of Intracellular Acidosis on Ito Activation and Kinetics of Inactivation

On the basis of the results in Fig. 5, we further examined the voltage dependence of Ito activation in Epi myocytes during intracellular acidosis, using a prestep with both Cd2+ (200 μM) and normal sodium in the bathing solutions (Fig. 6). As shown in the example signals in Fig. 6A and summarized in Fig. 6B, intracellular acidosis (pHo 7.4, pHi 6.75) reduced Ito by ∼50% at nearly all voltages between −40 mV and +60 mV. The percent reduction in Ito at +40 mV with CL = 5 s (−56.2 ± 3.1%) was not significantly different from that at CL = 1 s (−61.1 ± 3.8%; n = 5, paired).

Fig. 6.

Effect of intracellular acidosis on Ito activation in Epi myocytes. A: example records from same cell showing the inhibitory action of intracellular acidosis (80.0 mM acetate) on Ito. Inset: voltage-clamp protocol. B: summary of results illustrating depressed current-voltage (I-V) curve at nearly all voltages (n = 9; **P < 0.01 paired, control vs. acidosis). C: intracellular acidosis (80.0 mM acetate) had negligible effects on steady-state activation and inactivation of Ito. Inactivation results same as shown in Fig. 3B (with Cd2+). Smooth lines are best fits with Boltzmann functions (see materials and methods). D: quantitative relationship between Ito and pHi in Epi myocytes. Data fit with the equation Ito = a + b/{1+[10(pK−pH)]n} (40). The respective values for a, b, pK, and n were 2.81, 8.523, 6.92, and 3.12. Inset: clamp protocol. pHi measurements were done in separate cells, with N values ranging from 5 to 13 and are from Saegusa et al. (41). The magnitude of intracellular acidosis (pHo 7.4) was varied by applying different concentrations of sodium acetate for 2 min while keeping extracellular Ca2+ activity constant. The lowest value of pHi was induced with 80.0 mM acetate. E: effect of low pHi (80.0 mM acetate) on the voltage dependence of Ito inactivation kinetics. Cells were voltage clamped according to the protocol shown in A. Low pHi decreased fast time constant of Ito inactivation (τf) at all voltages (n = 5; **P < 0.01 paired, *P < 0.05, paired, control vs. acidosis). τs, slow time constant of Ito inactivation. For all results shown in this figure pacing CL = 5 s; Cd2+ (200 μM) and normal sodium were present in all bathing solutions.

Figure 6C summarizes the effects of intracellular acidosis on both steady-state activation and inactivation. Low pHi did not significantly change the V1/2 of activation (11.3 ± 1.5 mV for control vs. 11.4 ± 1.9 mV for acidosis), while the slope was significantly decreased from −19.7 ± 0.8 mV in control to −15.3 ± 0.8 mV (n = 9, P < 0.01 paired). Steady-state inactivation was also unaffected by intracellular acidosis (with Cd2+, same results shown Fig. 3B).

The quantitative relationship between pHi (pHo 7.4) and epicardial Ito at +50 mV is summarized in Fig. 6D and shows that Ito was inhibited by low pHi with an apparent pK of 6.92.

Figure 6E summarizes the voltage dependence of the fast (τf) and slow (τs) time constants of Ito inactivation from +40 mV to +60 mV (CL = 5 s). Low pHi had no significant effect on τs but speeded τf at all voltages. Similarly, when the CL was maintained at 2 s, low pHi had no significant effect on τs but reduced τf from 10.4 ± 0.5 ms to 6.3 ± 0.6 ms at +50 mV (n = 4, P < 0.01, paired).

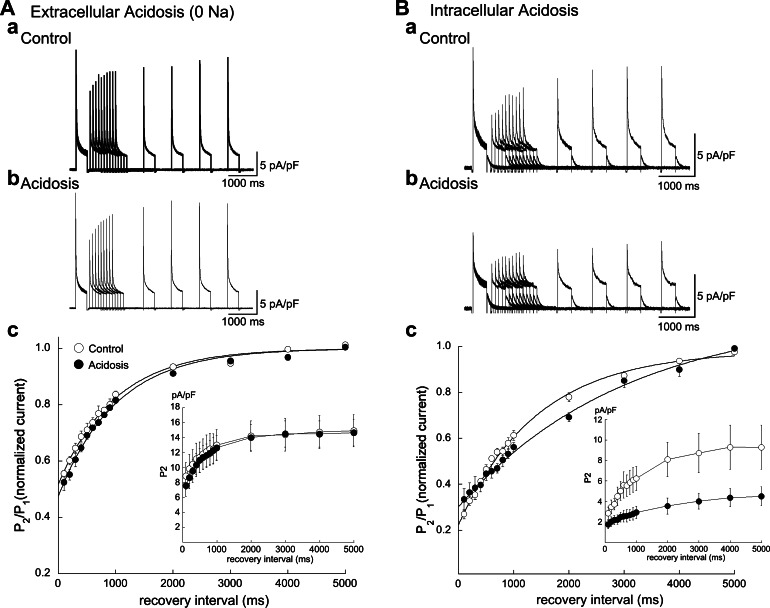

Effect of Acidosis on Recovery from Inactivation

The time course of recovery from inactivation in Epi myocytes was studied with a standard two-pulse protocol (Fig. 7). The low-pHo experiments were performed in sodium-free solution without a prestep. The recovery from inactivation of Ito in myocytes from control and both two types of acidosis was best fit by a single-exponential function. The recovery time constant was unaffected by low pHo but slowed by low pHi.

Fig. 7.

Effect of acidosis on the time course of Ito recovery from inactivation. A: extracellular acidosis (pHo 6.5) had no significant effect on the time constant of recovery from inactivation (τcont = 986 ms, τacid = 1,009 ms; n = 4). a and b: Example signals from the same cell. c: Summarized results. B: in contrast, low pHi (80.0 mM acetate) slowed recovery from inactivation (τcont = 1,421 ms, τacid = 2,997 ms; n = 4). a and b: Example signals from the same cell. c: Summarized results. Clamp CL = 10 s. Insets: averaged actual values of Ito (pA/pF) in cells clamped with test pulses (P2) to +60 mV after conditioning clamp pulse (P1) to +60 mV.

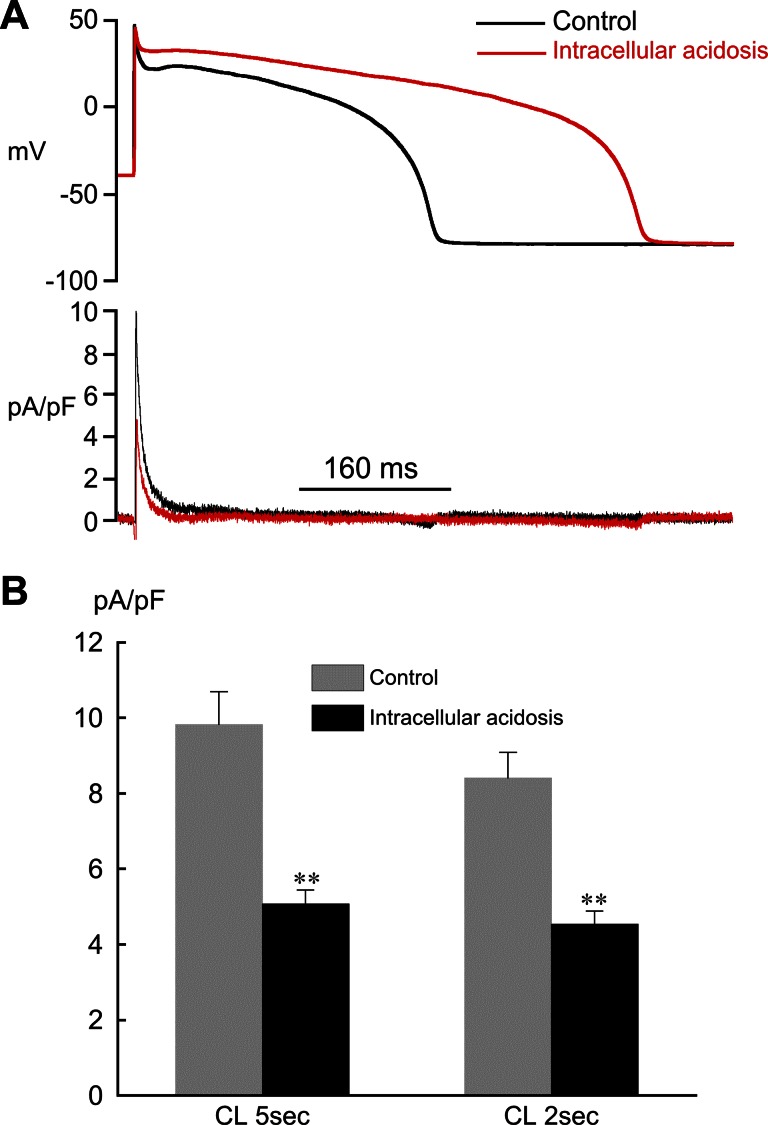

Effect of Intracellular Acidosis on Ito During AP Clamps

To determine the effects of low pHi on Epi Ito under more physiological conditions than with rectangular clamp steps, we also conducted AP clamp experiments (Fig. 8). Clamps were applied to Epi myocytes at CLs of 2 and 5 s since Ito and phase 1 repolarization in rabbit ventricular myocytes are affected by pacing rate (17, 20). The templates used for the control and acidosis AP clamps were representative of epicardial APs recorded at both rates. Figure 8A illustrates the inhibitory effect of low pHi on Ito elicited by AP clamps (CL = 5 s). The peak amplitude of Ito was significantly reduced at both pacing rates (Fig. 8B), and there was no significant difference in the percent change relative to control between the two rates (unpaired). These results demonstrate the striking action of internal protons to inhibit Ito during APs.

Fig. 8.

Effect of intracellular acidosis on Epi Ito during AP clamps. A: example AP clamp experiment showing the action of intracellular acidosis (80.0 mM acetate) to reduce Ito. CL = 5 s. B: summary of results for peak Ito during AP clamps (CL = 5 s, n = 8; CL = 2 s, n = 7). **P < 0.01, paired, compared with control.

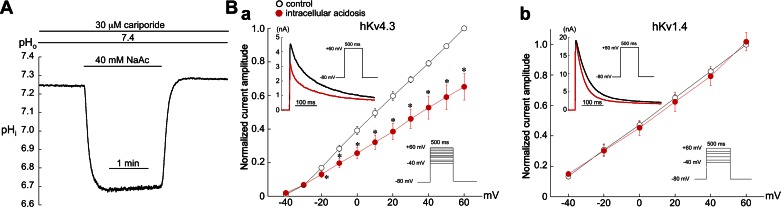

Effect of Acidosis on Human Kv4.3 and Kv1.4 Expressed in HEK 293T Cells

On the basis of the voltage-dependent kinetics of recovery from inactivation and the time course of inactivation, transient outward current can be classified as fast (Itof) and slow (Itos). Itof shows rapid recovery (i.e., recovery time constants on the order of 10 to hundreds of milliseconds), and Itos shows slow recovery (i.e., on a timescale of seconds) (36). Evidence indicates that the pore-forming domain of the channel underlying Itof is formed by a combination of Kv4.2 and/or Kv4.3 subunits, while Kv1.4 is the molecular component underlying Itos (32, 34, 36). In addition, a variety of regulatory subunits have major effects on the properties of Kv1.4, Kv4.2, and Kv4.3, including channel kinetics and expression (32, 36). Although the exact molecular basis of Ito in rabbit ventricle is unresolved, expression of mRNA and/or protein of Kv4.2, Kv4.3, and Kv1.4 has been reported (34, 39, 54).

To help identify which channel mediates the response of rabbit Ito to low pHi, we examined the effects of intracellular acidosis on hKv4.3 and hKv1.4 channels expressed in HEK 293T cells (Fig. 9). The bathing solutions contained normal sodium and no Cd2+, and no prestep was required to block sodium current. As shown in Fig. 9A, exposure to 40 mM acetate for 1 min (pHo 7.4, 30 μM cariporide) rapidly reduced pHi from a control value of 7.26 ± 0.01 to 6.70 ± 0.04 (n = 4), which is comparable to that in ventricular myocytes bathed in 80 mM acetate (Fig. 1D). This difference in response to acetate (40 mM vs. 80 mM) most likely reflects a lower intrinsic buffering power in HEK cells. Low pHi decreased hKv4.3 current at nearly all voltages but had no significant effect on the I-V relationship of hKv1.4 (Fig. 9B). In contrast to the effects of low pHi, extracellular acidosis had no significant effect on the I-V curve of hKv4.3 over the voltage range of −40 mV to +60 mV (n = 3, data not shown).

Fig. 9.

Effects of intracellular acidosis on human (h)Kv4.3 and hKv1.4 channels expressed in HEK 293T cells. A: example of pHi measurement in a nontransfected HEK 293T cell showing the effects of a 1-min exposure to 40.0 mM acetate (pHo 7.4). B, a: low pHi depressed the I-V curve for hKv4.3 at nearly all voltages (n = 4). Inset: example experiment showing the inhibitory effect of low pHi on hKv4.3 current elicited at +60 mV. b: In contrast, the I-V curve for hKv1.4 current was unaffected by low pHi (n = 4). Inset: example experiment showing the lack of effect of low pHi on peak hKv1.4 current elicited at +60 mV. *P < 0.05, paired, control vs. acidosis.

The kinetics of inactivation of both hKv4.3 and hKv1.4 were accelerated by intracellular acidosis. Thus for Kv4.3 inactivation, two of the four cells were best fit by a single exponential and yielded time constants of inactivation at +60 mV of τcontrol = 163 ± 3 ms and τacidosis = 110 ± 10 ms. The same effect also occurred in the two cells best fit by a double exponential (τfast,control = 18 ± 4 ms, τfast,acidosis = 11 ± 3 ms; τslow,control = 134 ± 12 ms, τslow,acidosis = 124 ± 10 ms; +60 mV). The time course of hKv1.4 inactivation at +60 mV was best fit by a single exponential and yielded a τcontrol = 108 ± 25 ms and τacidosis = 76 ± 17 ms (n = 4, P < 0.05, paired).

Taken together, the results in Fig. 9 suggest that the inhibition of Ito by intracellular acidosis in rabbit ventricular myocytes is mediated, in part, by blockade of Kv4.3 current.

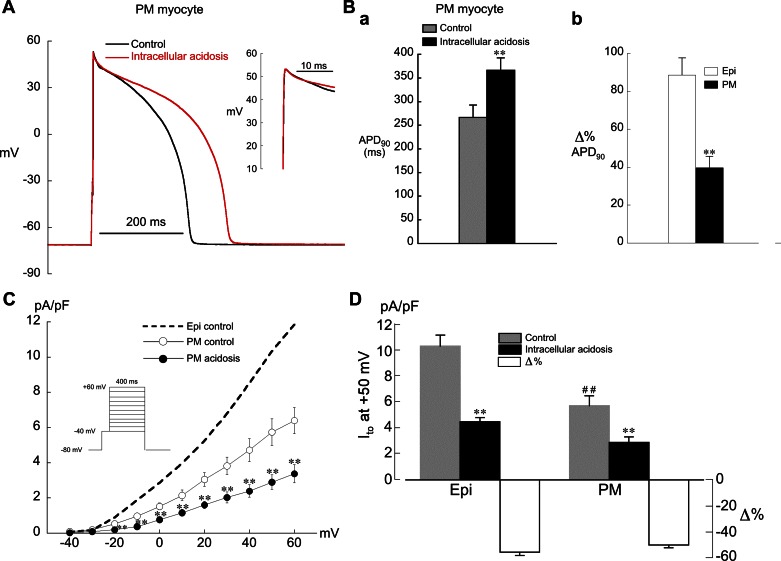

Effect of Intracellular Acidosis on AP and Ito in Papillary Muscle Myocytes

Rabbit ventricular myocytes display marked regional differences in Ito density, with Epi cells having the highest and PM cells the lowest (17). This current gradient has large effects on AP repolarization in the intact heart. Given this spatial heterogeneity, it was of interest to also study the response of PM myocytes to intracellular acidosis.

Intracellular acidosis had little effect on phase 1 repolarization in PM cells, and the prolongation of APD was much less than in Epi myocytes (Fig. 10, A and B). Figure 10C demonstrates that under control conditions Ito current density in PM myocytes was approximately half that of Epi cells, in accord with previous work (17). During intracellular acidosis Ito was reduced by ∼50% at all voltages in PM cells (Fig. 10, C and D). These results suggest that regional differences in Ito current density make a significant contribution to the differential response of AP repolarization to low pHi in Epi and PM myocytes.

Fig. 10.

Effects of intracellular acidosis on AP and Ito in PM myocytes. A: example experiment showing the effect of intracellular acidosis (80.0 mM acetate) to prolong APD with little effect on phase 1 repolarization. CL = 2 s. Inset: expanded view of phase 1 repolarization. B, a: summarized APD90 results for low pHi in PM myocytes at CL = 2 s (n = 8; **P < 0.01, paired). b: % change in APD90 relative to control after 2 min of low pHi in Epi (n = 11; same results as Fig. 2D) and PM (n = 8; **P < 0.01, unpaired) myocytes. C: low pHi in PM myocytes (n = 8) depressed Ito at nearly all voltages. CL = 5 s. **P < 0.01, paired. Control I-V curve from Epi myocytes shows same data as Fig. 6B. D: summary of results for Ito in Epi (n = 9) and PM (n = 8) myocytes at +50 mV and % change relative to control. CL = 5 s. ##P < 0.01, unpaired, comparison of control Ito amplitude in Epi and PM myocytes; **P < 0.01, paired, control vs. acidosis.

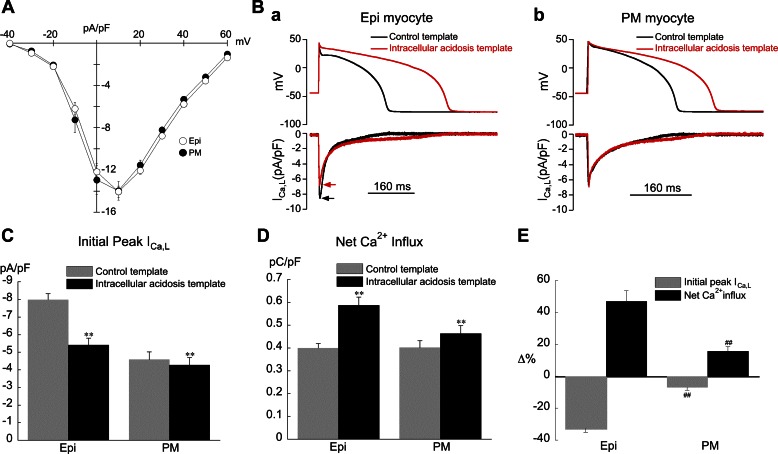

Modulation of ICa,L by pHi-Induced Changes in AP Waveform

The effects of intracellular acidosis on AP repolarization in Epi myocytes are much more prominent than those in PM cells (compare Fig. 2B to Fig. 10A). Epi cells show a marked slowing of phase 1, loss of the notch, and much greater AP prolongation (Fig. 10Bb). Since phase 1, the notch, and APD have been shown to modulate ICa,L, this could have significant effects on calcium handling (42, 43). In this series of experiments we sought to determine how ICa,L is affected by pHi-induced changes in AP repolarization in Epi and PM myocytes, using AP voltage clamps. Only male rabbits were used for these experiments since transmural differences in peak ICa,L density have been reported for female rabbits (37). To confirm the absence of a transmural gradient we measured ICa,L density in both cell types under control conditions (no acidosis) with a conventional rectangular voltage-clamp protocol. As shown in Fig. 11A, the I-V curves for ICa,L were virtually identical in the two cell types.

Fig. 11.

Response of L-type calcium current (ICa,L) in Epi and PM myocytes to changes in AP repolarization induced by intracellular acidosis (80.0 mM acetate). Control bathing solution was used for all experiments shown in this figure. A: ICa,L in control bathing solution was virtually the same in Epi (n = 11) and PM (n = 9) cells. B, a: example of an AP clamp experiment (Epi myocyte) showing the action of the intracellular acidosis template to decrease peak ICa,L and prolong its duration. b: Example of an AP clamp experiment (PM myocyte) showing the action of the intracellular acidosis template to prolong ICa,L duration with little effect on peak current. C: summary of results for peak ICa,L during AP clamps (Epi n = 11, PM n = 9; **P < 0.01, paired, control vs. acidosis template). D: summary of results for net Ca2+ influx via ICa,L during AP clamps. Same cells as in C. E: results in C and D expressed as % change. ##P < 0.01, unpaired, Epi vs. PM. CL = 2 s was used for all experiments shown in this figure.

For AP voltage-clamp experiments both the control and acidosis templates were applied in the control bathing solution (K+ replaced with Cs+) with the normal pipette filling solution for ICa,L measurements (Cs+, BAPTA). This approach allowed us to determine how pHi-induced changes in AP repolarization per se affect ICa,L without the complicating effects of intracellular acidosis.

As illustrated in Fig. 11, B–E, application of the acidosis template decreased the initial peak value of ICa,L and prolonged its duration, with the greatest changes occurring in Epi cells. Despite the fall in peak ICa,L (Fig. 11C), net Ca2+ influx via ICa,L increased in both cell types, with the greatest increase occurring in Epi cells (Fig. 11D). The changes in peak ICa,L and net Ca2+ influx, expressed as percentage, are summarized in Fig. 11E.

These results demonstrate that the action of low pHi to slow phase 1 repolarization and prolong APD significantly alters ICa,L and net Ca2+ influx via ICa,L, with the greatest changes occurring in Epi myocytes. Thus internal H+ ions can have significant indirect effects on voltage-dependent ICa,L mediated, in part, by pHi-induced changes in Ito that alter the time course of repolarization.

Modulation of CaTs by pHi-Induced Changes in AP Waveform

To determine whether CaTs elicited by APs are affected by pHi-induced slowing of phase 1 repolarization and APD prolongation, we performed the AP clamp experiments shown in Fig. 12. All studies were performed in control bathing solution with the same AP templates as those shown in Fig. 11 and the normal pipette filling solution (no Cs+, no BAPTA). The Epi templates were applied to Epi myocytes, and the PM templates were applied to PM myocytes. Small but significant increases in the amplitude and rate of rise of the CaT occurred in Epi but not PM myocytes (Fig. 12, Ba and Bb). The duration of the CaT (CaTD50) was increased by the intracellular acidosis template in both cell types (Fig. 12, A and Bc).

We also performed separate AP clamp experiments in which ICa,L and CaT were simultaneously recorded in Epi and PM myocytes. The AP templates were the same as those shown in Fig. 12A and were applied to their respective cell types. Potassium in the bathing solution was replaced with Cs+, and the pipette filling solution was the normal solution used for ICa,L measurements, except that it contained no BAPTA. The results are summarized in Table 2 and show that the intracellular acidosis template decreased peak ICa,L by −31.0 ± 3.9% and −7.8 ± 1.7% in Epi (n = 5) and PM (n = 5) myocytes, respectively. These results are very similar to those obtained with AP clamps during BAPTA dialysis (Fig. 11C). In addition, the acidosis template in Epi but not PM cells increased both the amplitude and rate of rise of the CaT. This resulted in a significant increase in E-C coupling gain in Epi but not PM myocytes, calculated as maximum rate of rise of the CaT divided by peak ICa,L.

Collectively, these results demonstrate that the striking changes in AP repolarization induced by intracellular acidosis have a significant modulating influence on ventricular calcium handling that is especially evident in cells with a prominent Ito.

DISCUSSION

Changes in myocardial pH have multiple effects on electrical activity and Ca2+ signaling (14, 33). This sensitivity accounts in part for the arrhythmias and depression of ventricular function that occur during myocardial ischemia, a condition associated with a fall in both pHi and pHo (3, 19). Here we examined the response of rabbit ventricular Ito to acute extra- and intracellular acidosis, especially intracellular, and determined the resulting effects on AP repolarization. We also studied the indirect action of these repolarization changes on ICa,L and CaTs. In contrast to previous reports of pH effects on ventricular Ito (24, 50, 58, 59), our experiments were performed at physiological temperature with a myocyte preparation with a more humanlike AP than that of rat.

We demonstrate that Ito is rapidly and markedly reduced by intracellular acidosis (Figs. 6, 8, and 10). This occurred in cells with both high (Epi) and low (PM) Ito densities. In both cell types low pHi reduced peak Ito over a large voltage range (−20 mV to +60 mV), resulting in an ∼50% fall in current density when pHi is reduced from 7.22 and 6.75. The apparent pK of this relationship in Epi cells was 6.92, demonstrating the high H+ sensitivity of Ito over the physiological range of pHi values.

Interestingly, this reduction in peak current was not accompanied by shifts in either steady-state inactivation or activation curves. This contrasts with the action of external H+ to induce right shifts (toward less negative potentials) in these parameters as reported here for rabbit ventricular myocytes (Fig. 3A) and previously for rat and human ventricular myocytes (50). These shifts presumably result from H+ screening of and/or binding to anionic sites such as carboxylic or amine/imidazole residues on the external sarcolemma and/or the channel itself. We have recently shown that both extra- and intracellular acidosis elicit large right and left shifts, respectively, in steady-state activation and inactivation of ICa,L in rabbit ventricular myocytes (41). The absence of shifts in Ito gating parameters during intracellular acidosis cannot be explained by the present study, but perhaps it reflects a low density of intracellular anionic sites on the channel itself.

Previous studies of rat ventricular myocytes also reported that intracellular acidosis reduced peak Ito without altering steady-state activation and inactivation (58, 59). However, those experiments were performed with pipette acid loading, without measuring pHi, and in some experiments without the same cell serving as its own control. In addition, the origin of the cells was not specified, e.g., epicardial or endocardial. All of these issues were avoided in the present work.

The absence of voltage shifts in Ito gating, accompanied by a large reduction in peak current during low pHi, strongly suggests a direct action of internal protons to reduce channel permeability, perhaps by titrating binding sites within the channel pore. This effect has a rapid onset and thus is unlikely to reflect a decrease in channel density.

We found no significant effect of extracellular acidosis on recovery from inactivation (Fig. 7A). In contrast, we did observe a small slowing of Ito recovery from inactivation during intracellular acidosis (Fig. 7B). However, this did not significantly affect the action of intracellular acidosis to reduce peak Ito during AP or rectangular voltage clamps elicited at CLs of 5, 2, or 1 s. Thus acidosis-induced slowing of recovery from inactivation does not appear to contribute significantly to the inhibitory effects of low pHi on Ito.

Response of Kv4.3 and 4.1 Currents to Intracellular Acidosis

Previous studies using heterologous expression systems reported that extracellular acidosis inhibited both human Kv4.3 current (49) and Kv1.4 from rat and ferret (10). In contrast, human Kv1.4 current is reported to be unaffected by extracellular acidosis but inhibited by intracellular acidosis (35). Kv1.4 and Kv4.3 are both expressed in rabbit ventricle (34, 39, 54). To help identify the molecular basis for the inhibitory action of intracellular acidosis on rabbit Ito, we examined the effects of low pHi on human Kv4.3 and Kv1.4 channels expressed in HEK 293T cells (Fig. 9). Kv1.4 current was unresponsive to a fall in pHi from 7.3 to 6.7 (pHo 7.4), while Kv4.3 current magnitude was significantly reduced over the voltage range of −20 to +60 mV (Fig. 9), suggesting that Kv4.3 mediates, in part, the sensitivity of rabbit ventricular Ito to pHi. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that differences in regulatory subunits and temperature (37°C vs. 23°C) between the native channels and those expressed in HEK cells may also affect the pHi sensitivity of these currents.

Relationship Between Action Potential Repolarization and Ito Inhibition by low pH

Consistent with the higher Ito density in Epi myocytes, the repolarization effects of intracellular acidosis to reduce Ito were most evident in this cell type, with marked slowing of phase 1, attenuation of the notch, and elevation of the plateau (compare Fig. 2B and Fig. 10B). The role of Ito inhibition in overall prolongation of APD in both cell types is less clear, but it seems likely that it contributed in part. Regardless of the detailed mechanism for the increased APD during low pHi, the magnitude of AP prolongation in Epi cells was approximately twice that in PM cells.

Although extracellular acidosis induced a right shift in steady-state inactivation (Fig. 3A), it did not affect the magnitude of Ito at +60 mV, a voltage near the peak of the AP, when activated from Vm near the normal diastolic value (Fig. 4A). In addition, both extra- and intracellular acidosis had only small effects on diastolic Vm (Fig. 2). Thus it seems unlikely that Ito is involved in the pHo-induced shortening of APD we observed in this preparation, a conclusion supported by our previous computer simulations (41).

Modulation of Calcium Handling by Intracellular Acidosis During Action Potentials

Our AP clamp experiments, performed with normal pHo and pHi, revealed that the changes in AP configuration induced by intracellular acidosis have significant effects on peak ICa,L, net Ca2+ influx via ICa,L, and the CaT (Fig. 11, Fig. 12, Table 2). These effects appear to be mediated, in part, by pHi-induced changes in Ito and are more prominent in Epi than PM myocytes. Several earlier studies reported that changes in phase 1 repolarization significantly affect ICa,L and CaTs during APs (6, 11, 43, 44). However, to our knowledge, this is the first demonstration that changes in ventricular repolarization induced by low pHi have significant indirect effects on calcium handling.

Our finding of a reduction in peak ICa,L, resulting from Ito inhibition (Fig. 11), is consistent with canine myocyte simulations (21) and rat myocyte experiments (11, 43, 44) and is likely mediated by the reduced voltage driving force acting on Ca2+ current. Epi myocytes displayed the greatest change in peak ICa,L, reflecting their higher Ito density and thus more pronounced slowing of phase 1. Despite the drop in peak ICa,L, net Ca2+ influx via ICa,L increased in both Epi and PM cells, presumably because of the prolonged APs. The largest increase in Ca2+ influx occurred in Epi cells, reflecting the greater AP lengthening (Fig. 11D).

The prolongation of the AP also caused CaT duration to increase in both cell types (Fig. 12Bc). However, the amplitude and rate of rise of the CaT as well as E-C coupling gain increased significantly only in Epi myocytes (Fig. 12, Ba and Bb, Table 2). These increases occurred despite a drop in the peak amplitude of Epi ICa,L. Under normal conditions, for a given magnitude of ICa,L, the amplitude of the CaT is steeply dependent on SR calcium load (46). It seems likely that the much larger increase in net Ca2+ influx in Epi myocytes promoted increased SR Ca2+ loading, leading to increased gain and CaT amplitude. Supporting this hypothesis is the finding in rat ventricular myocytes of increased SR Ca2+ load and CaT amplitude when APD is increased (42). Similarly, AP prolongation increases CaT amplitude in rabbit ventricular myocytes (38).

In contrast to our results, both rabbit and rat ventricular myocytes displayed reduced CaT amplitude when subjected to AP clamps using human AP templates of heart failure in which the notch was reduced and APD increased (11). The authors proposed that the smaller CaT amplitude resulted from a reduction in peak ICa,L that decreased synchrony of SR Ca2+ release. We cannot rule out dyssynchronous Ca2+ release in our experiments. However, it seems possible that its effect on CaT amplitude was mitigated by enhanced SR Ca2+ content mediated by the much greater AP prolongation during low pHi (∼88%; Fig. 2D) compared with that of the heart failure AP templates (∼25%) used in the Cooper et al. study (11).

In summary, we have shown that, in contrast to low pHo, intracellular acidosis has a marked inhibitory effect on rabbit ventricular Ito, perhaps mediated by Kv4.3. The repolarization effects of this inhibition were much greater in Epi than PM myocytes and included slowing of phase 1, attenuation of the notch, and elevation of the plateau. In addition, the low pHi-induced prolongation of APD was greatest in Epi myocytes. In the intact heart this may have the undesirable effect of promoting transmural heterogeneity of repolarization under pathological conditions in which pHi falls. Increased dispersion of repolarization has been shown to facilitate the occurrence of reentrant arrhythmias (26). By altering the trajectory of the AP waveform, low pHi modulates calcium handling as reflected in a reduction in initial peak ICa,L, increased net Ca2+ influx via ICa,L, and increased CaT amplitude and duration. Thus, in addition to the direct action of [H+]i on ICa,L (41), SR Ca2+ release and uptake (28), NCX (15), and diastolic Ca2+ (41), low pHi also exerts a significant indirect effect on E-C coupling. This illustrates the striking diversity of mechanisms that contribute to the overall response of ventricular myocytes to acute increases in [H+]i.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant R37 HL-042873 and the Nora Eccles Treadwell Foundation (to K. W. Spitzer) and an American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship (to V. Garg).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: N.S., V.G., and K.W.S. conception and design of research; N.S., V.G., and K.W.S. performed experiments; N.S., V.G., and K.W.S. analyzed data; N.S., V.G., and K.W.S. interpreted results of experiments; N.S. and K.W.S. prepared figures; N.S. and K.W.S. drafted manuscript; N.S., V.G., and K.W.S. edited and revised manuscript; N.S., V.G., and K.W.S. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Juergen Puenter of Sanofi-Aventis, Frankfurt, Germany for generously providing cariporide for these experiments. We gratefully acknowledge the useful advice of Dr. Michael Sanguinetti.

REFERENCES

- 1. Agus ZS, Dukes ID, Morad M. Divalent cations modulate the transient outward current in rat ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 261: C310–C318, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ajiro Y, Saegusa N, Giles WR, Stafforini DM, Spitzer KW. Platelet-activating factor stimulates sodium-hydrogen exchange in ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 301: H2395–H2401, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Allen DG, Orchard CH. Myocardial contractile function during ischemia and hypoxia. Circ Res 60: 153–168, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Antzelevitch C, Sicouri S, Litovsky SH, Lukas A, Krishnan SC, Di Diego JM, Gintant GA, Liu DW. Heterogeneity within the ventricular wall: electrophysiology and pharmacology of epicardial, endocardial, and M cells. Circ Res 69: 1427–1449, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bassani RA, Altamirano J, Puglisi JL, Bers DM. Action potential duration determines sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ reloading in mammalian ventricular myocytes. J Physiol 559: 593–609, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bouchard RA, Clark RB, Giles WR. Effects of action potential duration on excitation-contraction coupling in rat ventricular myocytes. Action potential voltage-clamp measurements. Circ Res 76: 790–801, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bridge JH, Smolley JR, Spitzer KW. The relationship between charge movements associated with ICa and INa-Ca in cardiac myocytes. Science 248: 376–378, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cheng H, Smith GL, Orchard CH, Hancox JC. Acidosis inhibits spontaneous activity and membrane currents in myocytes isolated from the rabbit atrioventricular node. J Mol Cell Cardiol 46: 75–85, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Clark RB, Bouchard RA, Salinas-Stefanon E, Sanchez-Chapula J, Giles WR. Heterogeneity of action potential waveforms and potassium currents in rat ventricle. Cardiovasc Res 27: 1795–1799, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Claydon TW, Boyett MR, Sivaprasadarao A, Ishii K, Owen JM, O'Beirne HA, Leach R, Komukai K, Orchard CH. Inhibition of the K+ channel Kv1.4 by acidosis: protonation of an extracellular histidine slows the recovery from N-type inactivation. J Physiol 526.2: 253–264, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cooper PJ, Soeller C, Cannell MB. Excitation-contraction coupling in human heart failure examined by action potential clamp in rat cardiac myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 49: 911–917, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Coraboeuf E, Carmeliet E. Existence of two transient outward currents in sheep cardiac Purkinje fibers. Pflügers Arch 392: 352–359, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cordeiro JM, Greene L, Heilmann C, Antzelevitch D, Antzelevitch C. Transmural heterogeneity of calcium activity and mechanical function in the canine left ventricle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 286: H1471–H1479, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Crampin EJ, Smith NP. A dynamic model of excitation-contraction coupling during acidosis in cardiac ventricular myocytes. Biophys J 90: 3074–3090, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Doering AE, Eisner DA, Lederer WJ. Cardiac Na-Ca exchange and pH. Ann NY Acad Sci 779: 182–198, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Farrell SR, Ross JL, Howlett SE. Sex differences in mechanisms of cardiac excitation-contraction coupling in rat ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 299: H36–H45, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fedida D, Giles WR. Regional variations in action potentials and transient outward current in myocytes isolated from rabbit left ventricle. J Physiol 442: 191–209, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Furukawa T, Myerburg RJ, Furukawa N, Bassett AL, Kimura S. Differences in transient outward currents of feline endocardial and epicardial myocytes. Circ Res 67: 1287–1291, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gettes LS, Casio WE. Effect of acute ischemia on cardiac electrophysiology. In: The Heart and Cardiovascular System, edited by Fozzard HA, Jennings RB, Haber E, Katz AM, Morgan HE. New York: Raven, 1992, p. 2021–2054 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Giles WR, Imaizumi Y. Comparison of potassium currents in rabbit atrial and ventricular cells. J Physiol 405: 123–145, 1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Greenstein JL, Wu R, Po S, Tomaselli GF, Winslow RL. Role of the calcium-independent transient outward current Ito1 in shaping action potential morphology and duration. Circ Res 87: 1026–1033, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hiraoka M, Kawano S. Calcium-sensitive and insensitive transient outward current in rabbit ventricular myocytes. J Physiol 410: 187–212, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hirayama Y, Kuruma A, Hiraoka M, Kawano S. Calcium-activated Cl− current is enhanced by acidosis and contributes to the shortening of action potential duration in rabbit ventricular myocytes. Jpn J Physiol 52: 293–300, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hulme JT, Orchard CH. Effect of acidosis on transient outward potassium current in isolated rat ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 278: H50–H90, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Irisawa H, Sato R. Intra- and extracellular actions of proton on the calcium current of isolated guinea pig ventricular cells. Circ Res 59: 348–355, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Janse MJ. Reentrant arrhythmias. In: The Heart and Cardiovascular System: Scientific Foundations (2nd ed.), edited by Fozzard HA, Haber E, Jennings RB, Katz AM, Morgan HE. New York: Raven, 1991, p. 2055–2094 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kaprielian R, Wickenden AD, Kassiri Z, Parker TG, Liu PP, Backx PH. Relationship between K+ channel down-regulation and [Ca2+]i in rat ventricular myocytes following myocardial infarction. J Physiol 517: 229–245, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kentish JC, Xiang JZ. Ca2+- and caffeine-induced Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum in skinned trabeculae: effects of pH and Pi. Cardiovasc Res 33: 314–323, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kurachi Y. The effects of intracellular protons on the electrical activity of single ventricular cells. Pflügers Arch 394: 264–270, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Murphy L, Renodin D, Antzelevitch C, Di Diego JM, Cordeiro JM. Extracellular proton depression of peak and late Na+ current in the canine left ventricle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 301: H936–H944, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nabauer M, Beuckelmann DJ, Uberfuhr P, Steinbeck G. Regional differences in current density and rate-dependent properties of the transient outward current in subepicardial and subendocardial myocytes of human left ventricle. Circulation 93: 168–177, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Niwa N, Nerbonne JM. Molecular determinants of cardiac transient outward potassium current (Ito) expression and regulation. J Mol Cell Cardiol 48: 12–25, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Orchard CH, Kentish JC. Effects of changes of pH on the contractile function of cardiac muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 258: C967–C981, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Oudit GY, Kassiri Z, Sah R, Ramirez RJ, Zobel C, Backx PH. The molecular physiology of the cardiac transient outward potassium current (Ito) in normal and diseased myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol 33: 851–872, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Padanilam BJ, Lu T, Hoshi T, Padanilam BA, Shibata EF, Lee HC. Molecular determinants of intracellular pH modulation of human Kv1.4 N-type inactivation. Mol Pharmacol 62: 127–134, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Patel SP, Campbell DL. Transient outward potassium current, “Ito,” phenotypes in the mammalian left ventricle: underlying molecular, cellular and biophysical mechanisms. J Physiol 569: 7–39, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pham TV, Robinson RB, Danilo P, Jr, Rosen MR. Effects of gonadal steroids on gender-related differences in transmural dispersion of L-type calcium current. Cardiovasc Res 53: 752–762, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Qi XY, Yeh YH, Chartier D, Xiao L, Tsuji Y, Brundel BJ, Kodama I, Nattel S. The calcium/calmodulin/kinase system and arrhythmogenic afterdepolarizations in bradycardia-related acquired long-QT syndrome. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2: 295–304, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rose J, Armoundas AA, Tian Y, DiSilvestre D, Burysek M, Halperin V, O'Rourke B, Kass DA, Marbán E, Tomaselli GF. Molecular correlates of altered expression of potassium currents in failing rabbit myocardium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H2077–H2087, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sabirov RZ, Okada Y, Oiki S. Two-sided action of protons on an inward rectifier K+ channel (IRK1). Pflügers Arch 433: 428–434, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Saegusa N, Moorhouse E, Vaughan-Jones RD, Spitzer KW. Influence of pH on Ca2+ current and its control of electrical and Ca2+ signaling in ventricular myocytes. J Gen Physiol 138: 537–559, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sah R, Ramirez RJ, Kaprielian R, Backx PH. Alterations in action potential profile enhance excitation-contraction coupling in rat cardiac myocytes. J Physiol 533: 201–214, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sah R, Ramirez RJ, Backx PH. Modulation of Ca2+ release in cardiac myocytes by changes in repolarization rate: role of phase-1 action potential repolarization in excitation-contraction coupling. Circ Res 90: 165–173, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sah R, Ramirez RJ, Oudit GY, Gidrewicz D, Trivieri MG, Zobel C, Backx PH. Regulation of cardiac excitation-contraction coupling by action potential repolarization: role of the transient outward potassium current (Ito). J Physiol 546: 5–18, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sánchez-Chapula J, Elizalde A, Navarro-Polanco R, Barajas H. Differences in outward currents between neonatal and adult rabbit ventricular cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 266: H1184–H1194, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shannon TR, Ginsburg KS, Bers DM. Potentiation of fractional sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release by total and free intra-sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium concentration. Biophys J 78: 334–343, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Shi H, Wang HZ, Wang Z. Extracellular Ba2+ blocks the cardiac transient outward K+ current. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 278: H295–H299, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shibata EF, Drury T, Refsum H, Aldrete V, Giles W. Contributions of a transient outward current to repolarization in human atrium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 257: H1773–H1781, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Singarayar S, Bursill J, Wyse K, Bauskin A, Wu W, Vanderberg J, Breit S, Campell TC. Extracellular acidosis modulates drug block of Kv4.3 currents by flecainide and quinidine. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 14: 641–650, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Stengl M, Carmeliet E, Mubagwa K, Flameng W. Modulation of transient outward current by extracellular protons and Cd2+ in rat and human ventricular myocytes. J Physiol 511: 827–836, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tsien RY. New calcium indicators and buffers with high selectivity against magnesium and protons: design, synthesis, and properties of prototype structures. Biochemistry 19: 2396–2404, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Vaughan-Jones RD, Peercy BE, Keener JP, Spitzer KW. Intrinsic H+ ion mobility in the rabbit ventricular myocyte. J Physiol 541: 139–158, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Volk T, Nguyen TH, Schultz JH, Ehmke H. Relationship between transient outward K+ current and Ca2+ influx in rat cardiac myocytes of endo- and epicardial origin. J Physiol 519: 841–850, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wagner S, Hacker E, Grandi E, Weber SL, Dybkova N, Sossalla S, Sowa T, Fabritz L, Kirchhof P, Bers DM, Maier LS. Ca/calmodulin kinase II differentially modulates potassium currents. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2: 285–294, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]